Abstract

Human infection with antimicrobial-resistant Campylobacter species is an important public health concern due to the potentially increased severity of illness and risk of death. Our objective was to synthesise the knowledge of factors associated with human infections with antimicrobial-resistant strains of Campylobacter. This scoping review followed systematic methods, including a protocol developed a priori. Comprehensive literature searches were developed in consultation with a research librarian and performed in five primary and three grey literature databases. Criteria for inclusion were analytical and English-language publications investigating human infections with an antimicrobial-resistant (macrolides, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, and/or quinolones) Campylobacter that reported factors potentially linked with the infection. The primary and secondary screening were completed by two independent reviewers using Distiller SR®. The search identified 8,527 unique articles and included 27 articles in the review. Factors were broadly categorised into animal contact, prior antimicrobial use, participant characteristics, food consumption and handling, travel, underlying health conditions, and water consumption/exposure. Important factors linked to an increased risk of infection with a fluoroquinolone-resistant strain included foreign travel and prior antimicrobial use. Identifying consistent risk factors was challenging due to the heterogeneity of results, inconsistent analysis, and the lack of data in low- and middle-income countries, highlighting the need for future research.

Keywords: Antimicrobial resistance, antimicrobial drugs, Campylobacter, food-borne infections, risk factor

Introduction

Campylobacter species is one of the leading causes of acute diarrheic illness, accounting for 16% of foodborne illnesses globally [1] and 8.42% of foodborne illnesses in Canada [2]. Infections are characterised by acute, watery diarrhoea progressing to bloody diarrhoea and often accompanied by abdominal pain, but vomiting is uncommon [3]. Campylobacter infection has an incubation period of 2–4 days and most people recover within 2–5 days [4]. An uncomplicated infection typically only requires supportive care to avoid dehydration [4]; however, some cases develop bacteraemia [5]. Although uncommon, complications related to Campylobacter infections include but are not limited to reactive arthritis, irritable bowel syndrome, Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS), and Miller Fisher Syndrome, a variant of GBS, which are autoimmune disorders characterised by nerve damage, muscle weakness, and sometimes paralysis [5, 6].

Fluoroquinolone and macrolide antimicrobials can be used in the treatment of complicated Campylobacter infections to reduce the duration of illness [7]. There is evidence that inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing practices occur in Canada for Campylobacter infections, such as prescribing antimicrobials after symptoms have resolved, before the culture results have confirmed the diagnosis of Campylobacter, or treatment before the collection of a sample [8]. Furthermore, antimicrobials not suggested by clinical antimicrobial stewardship guidelines have also been prescribed [9]. Human infections with strains resistant to macrolides, fluoroquinolones/quinolones, and other antimicrobial classes including tetracyclines occur [10], and these infections may have an increased risk of an adverse health event such as a longer duration of illness, hospitalisation, invasive illness, or death, than patients with a susceptible infection [11–13].

There is a large amount of research on factors associated with human Campylobacter infections, including undercooked meat, especially chicken, contaminated unpasteurised milk, animal contact, and contaminated water [4]. However, despite this wealth of research, searches on 21 January 2020, in Ovid Medline®, Cochrane Library, Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Systematic Review Registry, and Google Scholar did not identify any scoping or systematic reviews on factors associated with infections with antimicrobial-resistant Campylobacter. The objective of this scoping review was to synthesise the published literature on factors associated with human infections with antimicrobial-resistant strains of Campylobacter species, with a focus on resistance to macrolides, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, and/or quinolones.

Methods

Protocol, search, and information sources

The review followed the systematic search methods outlined in the JBI Reviewer’s Manual [14] and is reported according to the PRISMA Scoping Review reporting guidelines [15]. The protocol was registered with the JBI Systematic Review Register on 5 February 2020, and is available in the Supplementary Material (S1). The PRISMA-Scoping Review checklist is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

A comprehensive search strategy was developed in consultation with a librarian to identify articles that studied human infections with antimicrobial-resistant Campylobacter. An example search string for MEDLINE® in Ovid® is shown in Supplementary Table S2. The complete search strings (S1) were used to search MEDLINE®, AGRICOLA™ in ProQuest®, Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience abstracts in Web of Science, EMBASE® in Ovid, and Scopus®. Grey literature sources included the World Health Organization’s Global Index Medicus, the Bielefield Academic Search Engine, and the first 250 results from Google Scholar when sorted by relevance. The search was completed on 5 February 2020, and was updated on 7 May 2021. Articles were de-duplicated in three stages in Mendeley (Version 1.19.8, Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands), EndNote (Version X9.2, Clarivate Analytics, London, United Kingdom), and DistillerSR (Version 2.35, Evidence Partners, Ottawa, ON, Canada).

Eligibility criteria

To be included, articles, theses, and dissertations had to be an analytic study that used a comparison group and reported on factors potentially associated with human infections with a strain of Campylobacter resistant to an antimicrobial of interest: macrolides, tetracyclines, and/or fluoroquinolones/quinolones (collectively referred to as fluoroquinolones hereafter). Resistance had to be determined by recognised laboratory antimicrobial susceptibility testing methods such as disc diffusion or broth micro-dilution. Review articles, commentaries, opinion pieces, editorials, newspaper articles, books, book chapters, and conference proceedings were excluded. No limits were applied to language, geographical location, Campylobacter species, or the date of publication. Non-English articles identified during screening were excluded. Included studies had to report human Campylobacter infections confirmed by recognised laboratory methods. Studies on nonhuman research, infections other than Campylobacter, colonisation instead of infection, or that failed to confirm a Campylobacter infection by recognised laboratory methods were excluded.

Factors associated with human infections with a resistant strain of Campylobacter were defined as observations that were measured and quantified, with the potential for identifying a reported statistical relationship to antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [16], which included but were not limited to age, recent travel, or pre-existing medical conditions. The comparator group had to be appropriate for the study design. For example, the comparator group for case–control studies were infections with strains of Campylobacter that were susceptible to the antimicrobials of interest. Inherently, the comparator group had to be Campylobacter isolates from human infections that were susceptible to the antimicrobials of interest, to compare to the resistant isolates from human infections.

Articles were screened for eligibility via a two-stage screening process by two independent reviewers. Article titles, abstracts, and keywords were screened in the first stage, and articles proceeded to secondary screening if both reviewers determined all eligibility criteria were met or unclear (S1). Secondary full-text screening by both reviewers included articles that answered yes to all eligibility criteria. The reasons for exclusion were documented. Reviewers resolved conflicts through discussion.

Data collection and synthesis

Data regarding authorship, publication date, the location of study, study type (defined by the authors or assigned by the reviewers), AMR outcome(s), Campylobacter species, the site of infection, factor description and descriptive data, results of measures of association (if considered), and the type of analysis (univariable vs. multivariable where reported) were extracted by one reviewer in Distiller SR® and analysed in Excel® (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and using the R Metaphor package (v4.1.1, R Core Team, 2021). Tables and figures present key findings in the results, whereas the Supplementary Material provides comprehensive results from the study. Factors were combined into themed categories for comparison. For relative associations, an odds ratio (OR) with a value of less than 1 is generally interpreted as a protective factor, whereas a value of greater than 1 was interpreted as a risk factor, meaning that either was associated with a decreased or increased risk of infection with a resistant strain of Campylobacter, respectively.

Results

Selection of information sources

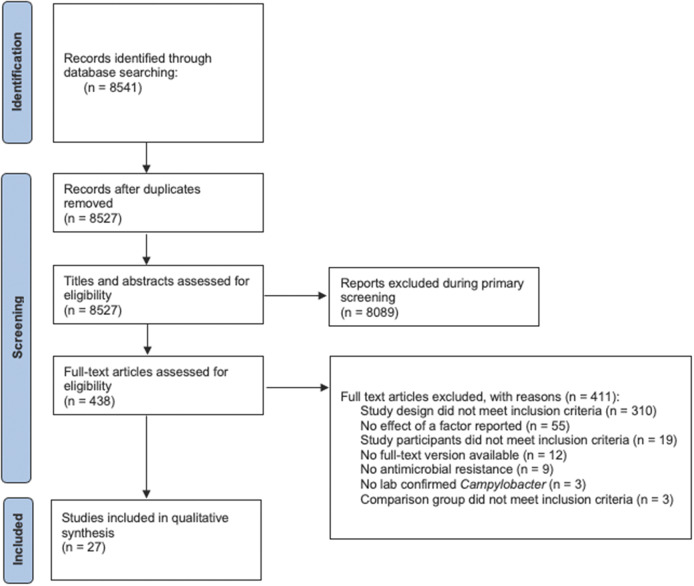

Our search identified 8,527 unique articles. Primary and secondary screening excluded 8,089 and 411 articles, respectively, including 12 where we could not locate a full-text document after additional inquiry through library requests (Figure 1). The review included 27 articles that met all inclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

PRISMA scoping review flow diagram of the study selection process for the scoping review of human infections with an antimicrobial-resistant strain of Campylobacter species.

Characteristics of information sources

The characteristics of included articles (n = 27) are included in Table 1. Complete extracted data for all studies are included in Supplementary Table S3. All articles were published between 1998 and 2018 except for one in 1988. The most common countries included the United States (n = 6), Denmark (n = 4), Canada (n = 3), and the United Kingdom (n = 3). Study designs included cross-sectional (n = 16), case–control (n = 4), case–case–control (n = 1), and various cohort designs (n = 6). The most commonly reported age range of participants was 20–50 years, but variations in reporting details made summarising age characteristics difficult. Fourteen studies reported the gender or sex of participants, but rarely included it in the analysis, whereas the rest did not report (n = 9) or did not include females in their study (n = 4). Most articles studied gastrointestinal infections (n = 19), and the most common species included was Campylobacter jejuni (n = 22). Six studies reported results for multivariable analyses, whereas the remaining 21 only reported results from univariable analyses if at all. Often, studies reported resistance to different antimicrobials. The most reported factor results were for resistance to fluoroquinolones (n = 20) and quinolones (n = 9), while resistance to macrolides (n = 13) and tetracyclines (n = 7) were also considered.

Table 1.

Key characteristics of peer-reviewed references included in the scoping review of factors related to human infections with an antimicrobial-resistant strain of Campylobacter species

| Study designa | Location | AMR | Species | Infection siteb | Total sample size | Age details (years)c | Percentage of femaled | Author and year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case–control (n = 4) | ||||||||

| Denmark | Quinolones Fluoroquinolones |

jejuni | NS | 126 | Mean = 33 IQR = 20–45 |

83.3% | Engberg et al. (2004) [12] | |

| India | Macrolides Quinolones Fluoroquinolones Tetracyclines |

jejuni | GI | 400 | Mean (cases) = 37 Mean (cont.) = 39.3 |

41.8% | Kownhar et al. (2007) [36] | |

| United Kingdom | Fluoroquinolones | NS | NS | 556 | Med (cases) = 53 Med (comp.) = 49 |

50.7% | Evans et al. (2009) [17] | |

| United States | Quinolone | jejuni | GI | 390 | NS | NS | Smith et al. (1999) [24] | |

| Case–case–control (n = 1) | ||||||||

| France | Fluoroquinolones | jejuni, coli, fetus, lari | GI | 570 | Mean (cases) = 19.5 Mean (cont.) = 20 |

0% | Gallay et al. (2007) [20] | |

| Cross-sectional (n = 16) | ||||||||

| Australia | Macrolides Quinolones Fluoroquinolones Tetracyclines |

jejuni | GI | 155 | NS | NS | Sharma et al. (2003) [25] | |

| Australia | Fluoroquinolones | upsaliensis | GI | 20 | Mean = 40 Range = 27–53 |

10% | Jenkin et al. (1998) [35] | |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | Macrolides Fluoroquinolones |

jejuni, coli | GI | 2,491 | Med. range = 0–6 Range = 0–64+ |

NS | Uzunovic-Kamberovic et al. (2009) [41] | |

| Canada | Fluoroquinolones | jejuni, coli, NS | NS | 210 | 16+ | 45.2% | Johnson et al. (2008) [21] | |

| Denmark | Macrolides Fluoroquinolones |

NS | GI | 10,475 | Range = 0–80+ | NS | Koningstein et al. (2011) [39] |

|

| Denmark | Macrolides Quinolones Tetracyclines |

jejuni | NS | 1,023 | NS | NS | Skjot-Rasmussen et al. (2009) [32] | |

| Finland | Fluoroquinolones | jejuni | GI | 166 | NS | 59.6% | Feodoroff et al. (2010) [27] | |

| Finland | Fluoroquinolones | Jejuni | GI | 354 | NS | NS | Hakanen et al. (2003) [29] | |

| Ireland | Fluoroquinolones Tetracycline |

15 jejuni, 2 coli | GI | 15 | Mean = 29.4 Range = 1–67 |

26.7% | Moore et al. (2002) [40] | |

| Netherlands | Macrolides Fluoroquinolones Tetracyclines |

94% jejuni | NS | 18,856 | NS | NS | van Hees et al. (2007) [33] | |

| United Kingdom | Macrolides Fluoroquinolones |

jejuni | GI | 174 | Med. = 2 Range = <1–75 |

40.2% | Ghunaim et al. (2015) [28] | |

| United Kingdom | Fluoroquinolones | jejuni | GI | 495 | Mean (cases) = 39 Mean (cont.) = 38 |

52.3% | CSSSCe et al. (2002) [18] | |

| United States | Macrolides Quinolones |

jejuni | GI/BS | 16,549 | Med. = 38 | 45.0% | Patrick et al. (2018) [31] | |

| United States | Fluoroquinolones |

jejuni | NS | 94 | Med. = 23.5 Range = <2–50+ |

42.9% | Cha et al. (2016) [19] | |

| United States | Macrolides Quinolones |

Mostly jejuni | GI | 24,433 | Mean (cases) = 37.1 Mean (comp.) = 36.2 |

45.5% | Ricotta et al. (2014) [34] | |

| United States | Fluoroquinolones | NS | GI | 740 | Med. = 34 Range = <1–96 |

46.0% | Nelson et al. (2004) [30] | |

| Cohort (n = 2) | ||||||||

| Denmark | Macrolides Quinolones |

NS | GI | 3,541 | Mean = 27.4 Range = 0.2–92.3 |

NS | Helms et al. (2005) [11] | |

| United States | Macrolides | jejuni, coli | GI | 4 | Mean = 47 Range = 39–67 |

0% | Perlman et al. (1988) [23] | |

| Prospective cohort (n = 1) | ||||||||

| Belgium | Fluoroquinolones | jejuni | GI | 1,730 | Mean = 33 Range = <1–73 |

NS | Bottieau et al. (2011) [26] | |

| Retrospective cohort (n = 3) | ||||||||

| Canada | Quinolones Fluoroquinolones Tetracyclines |

jejuni | GI | 31 | Range = 21–64 | 0% | Gaudreau et al. (2015) [38] | |

| Canada | Macrolides Fluoroquinolones Tetracyclines |

jejuni | GI | 14 | Range = 26–40 | 0% | Gaudreau et al. (2003) [37] | |

| Taiwan | Macrolides | jejuni, coli | BS | 21 | Med. = 45 Range = 4–81 |

42.9% | Lu et al. (2000) [22] | |

When a study design was not specified by the authors, the study design was determined by the first author during data extraction based on the reported methods.

Infection type specified or determined during data extraction where possible; BS, blood-stream infection; GI, gastrointestinal infection; NS, not specified/could not be determined.

Specified or calculated during data extraction where possible; comp., comparisons; cont., controls; IQR, interquartile range; Med., median; NS, not specified.

Percentage of female versus other, specified in the article or calculated during the data extraction where possible; NS, not specified.

CSSSC, Campylobacter Sentinel Surveillance Scheme Collaborators.

Information about factors

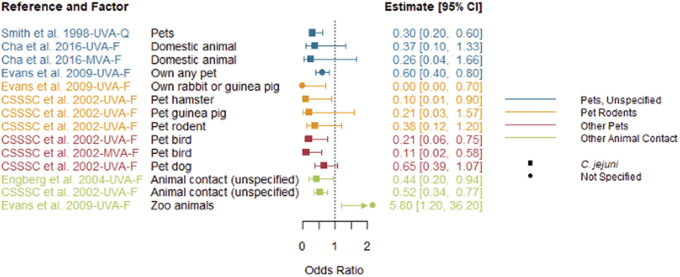

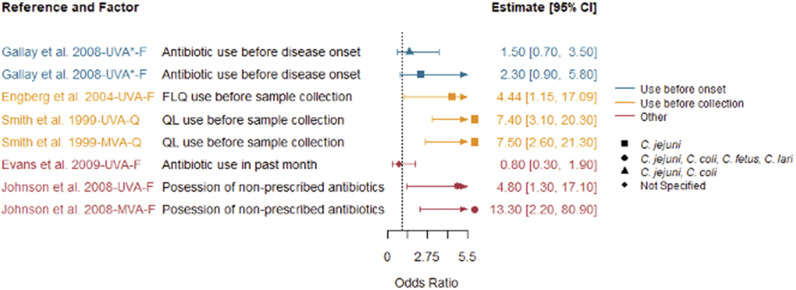

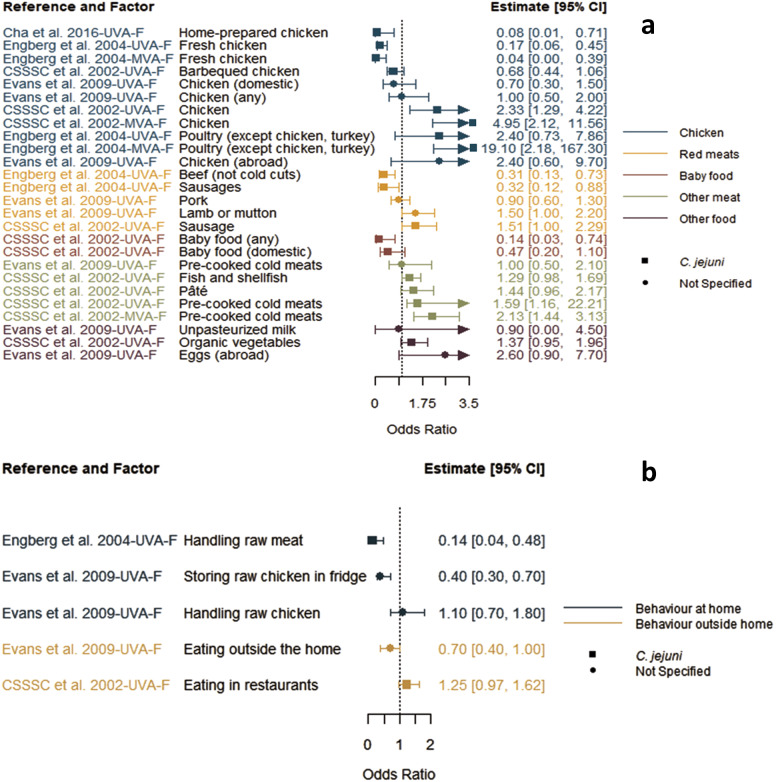

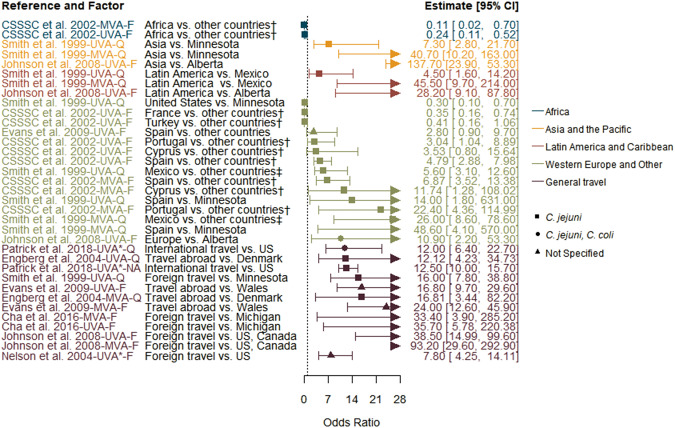

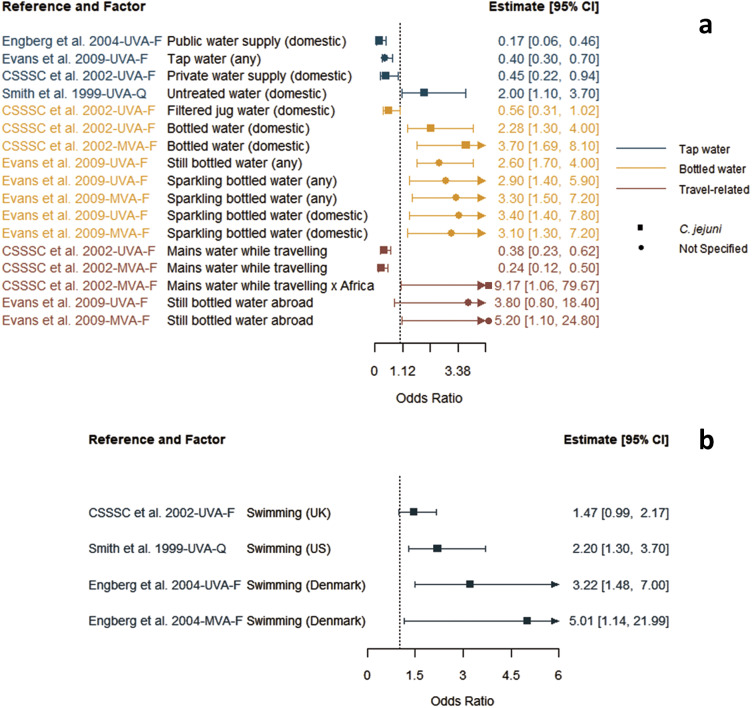

Reported factors related to resistant Campylobacter infections are summarised in Supplementary Table S4 and were combined into seven themes: animal contact (Figure 2), prior antimicrobial use (Figure 3), food and food preparation (Figure 4a,b), travel (Figure 5), underlying health conditions (Supplementary Table S5), water exposure (Figure 6a,b), and participant characteristics (Supplementary Table S5). Articles reporting factors regarding travel (n = 17) and participant characteristics (n = 14) were the most common. Most of the studies were conducted in a small number of high-income, westernised countries. Studies reported data for unspecified Campylobacter species as well as C. jejuni, Campylobacter coli, Campylobacter fetus, and Campylobacter lari.

Figure 2.

Animal contact factors identified in studies included in the scoping review for human infections with antimicrobial-resistant Campylobacter strains compared to infection with susceptible strains, limited to studies reporting odds ratios.

Note: CSSSC, Campylobacter Sentinel Surveillance Scheme Collaborators; F, fluoroquinolone-resistant outcome; MVA, multivariable analysis result; Q, quinolone-resistant outcome; UVA, univariable analysis result

Figure 3.

Prior antimicrobial use as factors identified in studies included in the scoping review for human infections with antimicrobial-resistant Campylobacter strains compared to infection with susceptible strains, limited to studies reporting odds ratios.

Note: F, fluoroquinolone-resistant outcome; MVA, multivariable analysis result; Q, quinolone-resistant outcome; UVA, univariable analysis result; UVA*, results from a study that only conducted univariable analysis.

Figure 4.

Food consumption (a) and preparation (b) factors identified in studies included in the scoping review for human infections with antimicrobial-resistant Campylobacter strains compared to infection with susceptible strains, limited to studies reporting odds ratios.

Note: CSSSC, Campylobacter Sentinel Surveillance Scheme Collaborators; F, fluoroquinolone-resistant outcome; MVA, multivariable analysis result; UVA, univariable analysis result.

Figure 5.

Travel factors identified in studies included in the scoping review for human infections with antimicrobial-resistant Campylobacter strains compared to infection with susceptible strains, limited to studies reporting odds ratios.

Note: CSSSC, Campylobacter Sentinel Surveillance Scheme Collaborators; F, fluoroquinolone-resistant outcome; MVA, multivariable analysis result; Q, quinolone-resistant outcome; UVA, univariable analysis result; UVA*, results from a study that only conducted a univariable analysis.

Figure 6.

Key data extracted for drinking water-related (a) and swimming (b) factors identified in studies included in the scoping review for human infections with an antimicrobial-resistant Campylobacter strains compared to infection with susceptible strains, limited to studies reporting odds ratios.

Note: CSSSC, Campylobacter Sentinel Surveillance Scheme Collaborators; F, fluoroquinolone-resistant outcome; MVA, multivariable analysis result; Q, quinolone-resistant outcome; UVA, univariable analysis result; UVA*, results from a study that only conducted a univariable analysis.

Synthesis of results

Animal contact

Five articles reported animal contact as a factor for infection with fluoroquinolone-resistant strains of Campylobacter (Figure 2). Most factors, including unspecified pets, pet rodents, dogs, birds, and other domestic or animal contact, were associated with a decreased risk of infection with resistant Campylobacter [12, 17–19]. Zoo-animal contact was the only animal factor that was significantly associated with an increased risk [17].

Prior antimicrobial use

Seven articles reported prior antimicrobial use as a factor [12, 17, 20–24], but only five reported the results of the analysis. All studies with speciated isolates found that prior antimicrobial use was associated with an increased risk of infection with fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter, but not all were statistically significant (Figure 3). The study with non-speciated isolates found prior antimicrobial use was associated with a lower risk, but it was not significant. The definition of prior antimicrobial use varied between studies, ranging from possession of non-prescribed antibiotics [21] to the use of an antibiotic before specimen collection [12, 24]. In addition, the definition of the interval for prior antimicrobial use was a month (4 weeks) [12, 17, 20, 24, 25], but when specified, the starting point of this interval also varied from a month prior to the onset of illness [20, 24], the onset of symptoms [12], infection [25], or stool sample collection [21].

Food and food preparation

Four articles reported many different factors related to food consumption and food handling or associated behaviours, all with fluoroquinolone resistance outcomes (Figure 4a,b) [12, 17–19]. There were opposing results of varying statistical significance for factors such as consumption of chicken, red meat, and other miscellaneous meats, as well as for handling of raw meat and raw chicken at home [12, 17–19] without any discernible patterns. When considering multivariable results, one study reported that those eating chicken had decreased risk, but increased risk when eating poultry other than chicken or turkey [12]. Another reported increased risk when eating chicken or pre-cooked cold meats [18]. Interestingly, two studies found that factors linked to handling [12] or storing of raw chicken [17] were significantly associated with a reduced risk for infection with a fluoroquinolone-resistant strain, whereas the latter paper found no association with handling raw chicken, all from univariable analyses.

Travel

Seventeen studies reported travel-related factors related to an infection with resistant Campylobacter (Figure 5) [11, 12, 17–19, 21, 24–34], and all found foreign travel, regardless of definition and destination country, to be significantly associated with an increased risk of infection with a fluoroquinolone-resistant strain. Of the articles that reported analysis, domestic study populations were limited to the United Kingdom [18], Wales [17], Denmark [12], Canada [21], and the United States [19, 21, 24, 30, 31]. Travel destinations included Africa, Asia, Central and South America, and Europe, but some articles conducted subanalyses on destinations within travel-only cases, which made interpretation challenging [18, 24, 29]. One study considered food and water exposure during travel but did not evaluate travel as a possible interaction [17]. Another study compared the rate of fluoroquinolone-resistant C. jejuni infections in Finnish patients that travelled abroad; specifically comparing rates of cases from various travel destinations to those travelling to Thailand [29]. They found that cases in Finnish residents travelling to Spain (including the Canary Islands) and Portugal had lower case rates of fluoroquinolone-resistant infections (rate ratios of 0.11 (95% CI 0.05–0.24) and 0.11 (0.07–0.16), respectively), whereas those travelling to China and India did not differ significantly from Thailand.

Water

Four articles explored factors related to water exposure, with a focus on water consumption and swimming [12, 17, 18, 24]. There was a large variety in the definition of water consumption-related factors and their association with increased or decreased risk of infection with fluoroquinolone-resistant strains (Figure 6a). Untreated water was associated with increased risk [24], whereas public, tap, or private domestic water was associated with decreased risk [12, 17, 18]. Several bottled water (domestic- or travel-sourced) factors were associated with increased risk [17, 18]. Generally, swimming was reported to increase the risk of infection with a resistant strain (Figure 6b).

Underlying conditions

Five studies explored factors related to underlying health conditions (Supplementary Table S5), but three did not analyse the data for association [17, 23, 30, 35, 36]. Of the two that did [17, 30], the only statistically significant factor was patients with diabetes (OR 0.30, 95% CI 0.10–1.00) [17]. Antacid use within the past month, indicating other potential conditions, was not significant (OR 1.50, 95% CI 0.90–2.40) [30]. Three studies investigated the risk associated with HIV infection but did not complete the analysis of their data [23, 35, 36].

Patient characteristics

Thirteen articles explored multiple factors related to participant characteristics such as season of infection, level of education, household income, gender, sex, and age (see Supplementary Table S5) [17–19, 21, 28–31, 37–41]. Factor definitions and results were highly variable, and only four articles conducted multivariable analyses of their data [17–19, 21].

Discussion

Summary of evidence

This scoping review identified 27 studies with factors related to human infections with an antimicrobial-resistant strain of Campylobacter and provides insight into the available literature and risks associated with these infections. Many reported specific gastrointestinal infections with C. jejuni, but there was variability in the site of infection (sample source and Campylobacter species), the AMR outcome, and subsequent factor analyses. This review identified key factors associated with infection with resistant strains, such as travel, prior antimicrobial use, animal exposure, and food- and water-related factors, but highlighted the vast heterogeneity of available data and associations with increased or decreased risk of infection with a resistant strain, as well as the gaps that could benefit from further research. Only a small number of studies reported multivariable analysis, and those that did were almost exclusively for fluoroquinolone resistance outcomes. All studies were conducted on cases from a small number of wealthy, westernised countries.

Risk factors

This review identified several important risk factors associated with human infections with resistant Campylobacter. The most consistent was foreign travel, with departure from home countries always being significantly associated with infection with a fluoroquinolone-resistant strain [12, 17, 19, 24, 25, 30, 31, 33, 34]. Care needs to be taken when interpreting these results as only departures from a few wealthy, westernised countries were studied, with highly variable definitions of destinations. Travel is a complex variable that, in this context, is largely a proxy for several different, often unmeasured, factors in the destination country, such as water quality, food/food handling practices and microbial contamination, and potential exposure to different strains of pathogens [42]. Genomics and molecular epidemiology should be employed to better understand the epidemiology of antimicrobial-resistant Campylobacter infections in future observational risk-factor studies.

Antimicrobial use prior to infection was another important reported factor for infection with resistant Campylobacter. While prior antimicrobial use is recognised to select for AMR, especially in Campylobacter [43, 44], only seven of the included studies reported this factor [12, 17, 20–24]. It is possible that many studies did not have access to these data linked to the human cases, which can be difficult to collect/obtain. It is important to note that in these studies, it represents a risk factor for infection with resistant Campylobacter compared to susceptible infection, but these observational studies cannot determine whether prior antimicrobial use is specifically selecting for development of a resistant strain in the human host as opposed to selecting for infection with a resistant over a susceptible strain. In addition to the inconsistent definitions of prior antimicrobial use, no studies reported drug dosing or duration, which would be important for future quantitative dose–response modelling. Prior antimicrobial use has been identified as a risk factor for other antimicrobial-resistant, foodborne bacterial infections, such as Salmonella Heidelberg [45]. Prior antimicrobial use may be due to inappropriate prescribing or over-the-counter drug access, which may represent less than optimal antimicrobial stewardship [44]. Only one included study reported a factor in this realm, possession of non-prescribed antibiotics [21]. It is also surprising that very few medical conditions requiring antimicrobial use were explored as comorbidities in the included studies. Only three articles looked at HIV and Campylobacter and did not analyse their data beyond providing counts [23, 35, 39].

Animal contact, including contact with seemingly healthy pets, has been implicated as a risk factor for AMR in humans [46–48], as well as general human infections with Campylobacter. Resistant Campylobacter has been isolated from cats and dogs, and pet store puppies have been implicated in a large extensively drug-resistant human outbreak of C. jejuni [49, 50]. Conversely, the included studies found that in most cases, animal contact was associated with a reduced risk of infection with a resistant strain compared to susceptible Campylobacter [12, 17–19, 24], with the one exception being zoo animal contact [17]. It may be that in these studies, the infecting strains from different animal sources have varying antimicrobial susceptibilities, but these observational study designs were not able to distinguish this, pointing to the need for genomics and molecular epidemiology to better understand these identified associations.

Contaminated foods, especially chicken meat, are known risk factors for infection with Campylobacter [4, 51], but only four studies included food-related factors in their analysis [12, 17–19]. There is evidence of AMR spreading to humans through the food chain, specifically broiler chickens in the case of Campylobacter, where antimicrobial use on farms may initially select for AMR [16, 52]. However, the results of food-related factors, including chicken, from included studies are mixed and variable. There are several potential reasons for this, including different study populations and potential confounding, intervening, or unmeasured factors, many of which were not considered in studies that did not conduct multivariable analyses. Many studies were cross-sectional, making causal inferences for these relationships challenging. Statistically significant multivariable results for food from two studies were discordant in that one found eating chicken protective while eating other poultry was a risk factor [12]. The other found eating chicken or pre-cooked cold meats to be a risk factor [18]. The food handling results were largely protective, but only from univariable analyses [12, 17]. Some risk factors for infection with Campylobacter may be independent of the susceptibility of the strain, and interventions that reduce the overall prevalence or concentration of Campylobacter in food or water could also reduce the risk of infection with a resistant strain, yet these types of factors were not studied [53–56]. It is also possible that risk factors for infection with a resistant strain would differ if there was more global representation among the studies included in the review, as different antimicrobials may be used and in some areas, access to these drugs can be over-the-counter for humans and animals [57, 58]. Lastly, while only one study included a factor related to vegetables [18], antimicrobial use in plant agriculture and the use of manure from animals as a fertiliser for crops may increase the risk of resistant organisms on produce [44, 59, 60].

Water consumption and contact are also recognised as potential risk factors for Campylobacter infection [51]; however, only four studies reported water-related factors with marked variability in the definition and results [12, 17, 18, 24]. Water contamination with Campylobacter varies regionally; however, little is known about contamination with fluoroquinolone-resistant versus susceptible Campylobacter. Fluoroquinolone resistance is largely mutational in Campylobacter, rather than by acquisition through mobile genetic elements [10], meaning that antimicrobial use in humans or animals and selection for resistant strains that contaminate water is the more likely source compared to acquisition in the environment. None of these studies evaluated this potential linkage, which would require more data about antimicrobial use and genomics.

Overall considerations

Antimicrobial resistance is a complex, population-level issue across One Health sectors that is driven by individual, regional, and global activities [60]. These studies reported factors at the individual level; however, population-level influences such as environmental sources, cleanliness of water, crop and animal agriculture, the spread of resistant organisms, the overall availability of antimicrobials, and the prescribing nature of the physicians and veterinarians are important to consider [44, 52, 60]. Identified factors and associations with risk of infection with resistant Campylobacter were variable, and generalisability was largely limited to wealthy, western countries. Resistance does not recognise borders and AMR surveillance in all countries linked to better patient metadata and genomics are needed to better understand these factors such as travel, prior antimicrobial use, food, and water [42]. In addition to individual patient-level factors, population-level research using a One Health approach that includes water quality, food safety and preparation, and antimicrobial use would expand our knowledge of risk-prevention strategies for infection with resistant Campylobacter [60, 61].

Care was taken to state these factors as associations with increased or decreased risk of infection with a resistant strain. The most common study design (cross-sectional) may suffer from reverse causation [62]. Additionally, when evaluating case–control studies, care must be taken when selecting controls to link the factor for AMR and to control for bias [54–56, 61]. The cohort study design controls for the temporality of events and provides the opportunity to measure multiple outcomes, but it is not well suited for the relatively rare incidence of infection with a resistant strain of Campylobacter [61].

We chose patients infected with antimicrobial-susceptible strains as our comparison group, which was appropriate for our research question to identify risk factors for infection with a resistant strain among all infections, but may have different results and interpretations than in comparison to healthy patients [61]. This comparison group may not be advantageous for identifying the strength of association for all risk factors of resistant Campylobacter infections, especially prior antimicrobial use [56]. Case–case–control studies for infection with resistant organisms compare those infected with a resistant strain to those with a susceptible strain and those who are healthy with a negative test, which allows researchers to better control for bias [54].

Our work yielded less insight into the global understanding of factors associated with human infections with antimicrobial-resistant Campylobacter than expected. The dearth of published studies included in our review in any low- and middle-income countries should be a call to action for research funders and government surveillance programmes alike [63]. Tackling AMR requires a One Health approach at the global level [60], and the lack of investment, for example, in AMR surveillance in all but developed countries speaks to the stark gaps present in global AMR research, surveillance, and understanding with a need for an equity lens to be applied to future surveillance and policy. Future use of case–case–control or case–control–control study designs is preferred to examine factors related to infection with resistant strains [54]. Conducting and reporting multivariable analyses is very important as simple univariable associations fail to account for confounding or identify interactions between related factors. In addition, reporting all factors assessed for association, not just those found to be statistically significant in uni- and multivariable models, would provide the complete picture.

Limitations

We aimed to minimise the possibility of not capturing all eligible articles for our review, a risk inherent in any literature review, by following a rigorous, systematic approach [64]. The factor list identified in this review is by no means exhaustive; it is likely there are factors that were outside the scope of our search or for which research is likely lacking. Our protocol also excluded articles primarily focused on identifying molecular and genetic similarities between human Campylobacter isolates with AMR with those from other sources such as animals and water. The synthesis of such literature was beyond the scope of this study but would be an important future contribution to the understanding of human infections with resistant Campylobacter. Additionally, excluding non-English articles and publishing bias against null findings has the potential to influence the factors included in our review [14]. There is limited global generalisability because there were no studies from Africa and South America and 24 out of 27 studies were in westernised, high-income countries. The lack of multivariable results for most studies, and, in particular, a seeming lack of identified or assessed interactions between factors, may fail to capture the complicated, interconnected nature of the impact of multiple factors on the risk of infection with resistant strains.

Conclusions

This scoping review mapped the current literature that investigated and quantified risk or protective factors related to a human infection with antimicrobial-resistant Campylobacter compared to susceptible infections. Travel, prior antimicrobial use, food consumption and handling, water consumption and exposure, and animal contact were important factors associated with the risk of infection with a resistant strain. The heterogeneity of the results, focus on fluoroquinolone-resistant outcomes, and lack of multivariable analyses made identifying concrete associations with risk factors challenging but highlighted areas for potential future research. The study of AMR in Campylobacter would benefit from an interdisciplinary, One Health research approach that expands to include research in low- and middle-income countries.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sandra Campbell, a research librarian from the University of Alberta, for her assistance in developing the search strings and protocol. We also thank the second reviewers Amreen Babujee, Soumayadita Ghosh, and Julia Grochowski.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268823000742.

click here to view supplementary material

Data availability statement

The search protocol and all extracted data are provided in the Supplementary Material. All the Supplementary Material is available on the Cambridge Core website.

Author contribution

See the summary included with co-authors in the submission portal.

Financial support

This study was funded through a grant from the Alberta Ministry of Technology and Innovation, by the Major Innovation Fund Program for the AMR – One Health Consortium, and the Genomics Research and Development Initiative Project on Antimicrobial Resistance.

Competing interest

The authors have no competing interest.

References

- [1].World Health Organization (2015) WHO Estimates of the Global Burden of Foodborne Diseases 2007–2015 [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/199350/?sequence=1 (accessed 28 June 2022). [Google Scholar]

- [2].Thomas MK, Murray R, Flockhart L, Pintar K, Pollari F, Fazil A, Nesbitt A and Marshall B (2013) Estimates of the burden of foodborne illness in Canada for 30 specified pathogens and unspecified agents, circa 2006. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease 10, 639–648. 10.1089/fpd.2012.1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Moore JE, Corcoran D, Dooley JSG, Fanning S, Lucey B, Matsuda M, McDowell DA, Mégraud F, Millar BC, O’Mahony R, O’Riordan L, O’Rourke M, Rao JR, Rooney PJ, Sails A and Whyte P (2005) Campylobacter. Veterinary Research 36, 351–382. 10.1051/vetres:2005012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017) Campylobacter (Campylobacteriosis) [Internet]. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/campylobacter/technical.html (accessed 28 June 2022).

- [5].Nachamkin I, Allos BM and Ho T (1998) Campylobacter species and Guillain–Barré syndrome. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 11, 555–567. 10.1128/cmr.11.3.555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Facciolà A, Riso R., Avventuroso E., Visalli G., Delia S.A. and Laganà P. (2017) Campylobacter: From microbiology to prevention. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene 58, E79–E92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ternhag A, Asikainen T, Giesecke J and Ekdahl K (2007) A meta-analysis on the effects of antibiotic treatment on duration of symptoms caused by infection with Campylobacter species. Clinical Infectious Diseases 44, 696–700. 10.1086/509924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Deckert AE, Reid-Smith RJ, Tamblyn SE, Morrell L, Seliske P, Jamieson FB, Irwin R, Dewey CE, Boerlin P and McEwen SA (2013) Antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial use associated with laboratory-confirmed cases of Campylobacter infection in two health units in Ontario. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology 24, e16–e21. 10.1155/2013/176494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dougherty B, Finley R, Marshall B, Dumoulin D, Pavletic A, Dow J, Hluchy T, Asplin R and Stone J (2020) An analysis of antibiotic prescribing practices for enteric bacterial infections within FoodNet Canada sentinel sites. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 75, 1061–1067. 10.1093/jac/dkz525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Luangtongkum T, Jeon B, Han J, Plummer P, Logue CM and Zhang Q (2009) Antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter: Emergence, transmission and persistence. Future Microbiology 4, 189–200. 10.2217/17460913.4.2.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Helms M, Simonsen J, Olsen KEP and Mølbak K (2005) Adverse health events associated with antimicrobial drug resistance in Campylobacter species: A registry-based cohort study. Journal of Infectious Diseases 191, 1050–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Engberg J, Neimann J, Nielsen EM, Aarestrup FM and Fussing V (2004) Quinolone-resistant Campylobacter infections: Risk factors and clinical consequences. Emerging Infectious Diseases 10, 1056–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wassenaar TM, Kist M and de Jong A (2007) Re-analysis of the risks attributed to ciprofloxacin-resistant Campylobacter jejuni infections. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 30, 195–201. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Aromataris E and Munn Z (2020) Chapter 11: Scoping reviews [Internet]. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Adelaide, SA: Joanna Briggs Institute. Available at https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/4687342/Chapter+11%3A+Scoping+reviews (accessed 28 June 2022). [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, MDJ Peters, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tunçalp Ö and Straus SE (2018) PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine 169, 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Murphy CP, Carson C, Smith BA, Chapman B, Marrotte J, McCann M, Primeau C, Sharma P and Parmley EJ (2018) Factors potentially linked with the occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in selected bacteria from cattle, chickens and pigs: A scoping review of publications for use in modelling of antimicrobial resistance (IAM.AMR Project). Zoonoses and Public Health 65, 957–971. 10.1111/zph.12515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Evans MR, Northey G, Sarvotham TS, Hopkins AL, Rigby CJ and Thomas DR (2009) Risk factors for ciprofloxacin-resistant Campylobacter infection in Wales. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 64, 424–427. 10.1093/jac/dkp179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Campylobacter Sentinel Surveillance Scheme Collaborators (2002) Ciprofloxacin resistance in Campylobacter jejuni: Case–case analysis as a tool for elucidating risks at home and abroad. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 50, 561–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cha W, Mosci R, Wengert SL, Singh P, Newton DW, Salimnia H, Lephart P, Khalife W, Mansfield LS, Rudrik JT and Manning SD (2016) Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of human Campylobacter jejuni isolates and association with phylogenetic lineages. Frontiers in Microbiology 7, 589. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gallay A, Bousquet V, Siret V, Prouzet-Mauléon V, Valk H, Vaillant V, Simon F, Strat YL, Mégraud F and Desenclos JC (2008) Risk factors for acquiring sporadic Campylobacter infection in France: Results from a national case–control study. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 197, 1477–1484. 10.1086/587644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Johnson JYM, McMullen LM, Hasselback P, Louie M, Jhangri G and Saunders LD (2008) Risk factors for ciprofloxacin resistance in reported Campylobacter infections in southern Alberta. Epidemiology and Infection 136, 903–912. 10.1017/S0950268807009296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lu PL, Hsueh PR, Hung CC, Chang SC, Luh KT and Lee CY (2000) Bacteremia due to Campylobacter species: High rate of resistance to macrolide and quinolone antibiotics. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association 99, 612–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Perlman DM, Ampel NM, Schifman RB, Cohn DL, Patton CM, Aguirre ML, Wang WL and Blaser MJ (1988) Persistent Campylobacter jejuni infections in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Annals of Internal Medicine 108, 540–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Smith KE, Besser JM, Hedberg CW, Leano FT, Bender JB, Wicklund JH, Johnson BP, Moore KA and Osterholm MT (1999) Quinolone-resistant Campylobacter jejuni infections in Minnesota, 1992–1998. New England Journal of Medicine 340, 1525–1532. 10.1056/NEJM199905203402001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sharma H, Unicomb L, Forbes W, Djordjevic S, Valcanis M, Dalton C and Ferguson J (2003) Antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter jejuni isolated from humans in the Hunter Region, New South Wales. Communicable Diseases Intelligence 27 Suppl, S80–S88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bottieau E, Clerinx J., Vlieghe E., van Esbroeck M., Jacobs J., van Gompel A. and van den Ende J. (2011) Epidemiology and outcome of Shigella, Salmonella and Campylobacter infections in travellers returning from the tropics with fever and diarrhoea. Acta Clinica Belgica 66, 191–195. 10.2143/ACB.66.3.2062545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Feodoroff B, Ellström P, Hyytiäinen H, Sarna S, Hänninen M-L and Rautelin H (2010) Campylobacter jejuni isolates in Finnish patients differ according to the origin of infection. Gut Pathogens 2, 22. 10.1186/1757-4749-2-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ghunaim H, Behnke JM, Aigha I, Sharma A, Doiphode SH, Deshmukh A and Abu-Madi MM (2015) Analysis of resistance to antimicrobials and presence of virulence/stress response genes in Campylobacter isolates from patients with severe diarrhoea. PLoS One 10, e0119268. 10.1371/journal.pone.0119268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hakanen A, Jousimies-Somer H, Siitonen A, Huovinen P and Kotilainen P (2003) Fluoroquinolone resistance in Campylobacter jejuni isolates in travelers returning to Finland: Association of ciprofloxacin resistance to travel destination. Emerging Infectious Diseases 9, 267–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nelson JM, Smith KE, Vugia DJ, Rabatsky-Ehr T, Segler SD, Kassenborg HD, Zansky SM, Joyce K, Marano N, Hoekstra RM and Angulo FJ (2004) Prolonged diarrhea due to ciprofloxacin-resistant Campylobacter infection. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 190, 1150–1157. 10.1086/423282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Patrick ME, Henao OL, Robinson T, Geissler AL, Cronquist A, Hanna S, Hurd S, Medalla F, Pruckler J and Mahon BE (2018) Features of illnesses caused by five species of Campylobacter: Foodborne diseases active surveillance network (FoodNet) – 2010–2015. Epidemiology and Infection 146, 1–10. 10.1017/S0950268817002370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Skjot-Rasmussen L, Ethelberg S, Emborg H-D, Agersø Y, Larsen LS, Nordentoft S, Olsen SS, Ejlertsen T, Holt H, Nielsen EM and Hammerum AM (2009) Trends in occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in Campylobacter jejuni isolates from broiler chickens, broiler chicken meat, and human domestically acquired cases and travel associated cases in Denmark. International Journal of Food Microbiology 131, 277–279. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].van Hees BC, Veldman-Ariesen MJ, de Jongh BM, Tersmette M and van Pelt W (2007) Regional and seasonal differences in incidence and antibiotic resistance of Campylobacter from a nationwide surveillance study in the Netherlands: An overview of 2000–2004. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 13, 305–310. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01643.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ricotta EE, Palmer A, Wymore K, Clogher P, Oosmanally N, Robinson T, Lathrop S, Karr J, Hatch J, Dunn J, Ryan P and Blythe D (2014) Epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance of international travel-associated Campylobacter infections in the United States, 2005–2011. American Journal of Public Health 104, e108–e114. 10.2105/ajph.2013.301867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Jenkin GA and Tee W (1998) Campylobacter upsaliensis-associated diarrhea in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Clinical Infectious Diseases 27, 816–821. 10.1086/514957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kownhar H, Shankar EM, Rajan R, Vengatesan A and Rao UA (2007) Prevalence of Campylobacter jejuni and enteric bacterial pathogens among hospitalized HIV infected versus non-HIV infected patients with diarrhoea in southern India. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases 39, 862–866. 10.1080/00365540701393096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gaudreau C and Michaud S (2003) Cluster of erythromycin- and ciprofloxacin-resistant Campylobacter jejuni subsp. jejuni from 1999 to 2001 in men who have sex with men, Quebec, Canada. Clinical Infectious Diseases 37, 131–136. 10.1086/375221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Gaudreau C, Rodrigues-Coutlée S, Pilon PA, Coutlée F and Bekal S (2015) Long-lasting outbreak of erythromycin- and ciprofloxacin-resistant Campylobacter jejuni subspecies jejuni from 2003 to 2013 in men who have sex with men, Quebec, Canada. Clinical Infectious Diseases 61, 1549–1552. 10.1093/cid/civ570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Koningstein M, Simonsen J, Helms M, Hald T and Mølbak K (2011) Antimicrobial use: A risk factor or a protective factor for acquiring campylobacteriosis? Clinical Infectious Diseases 53, 644–650. 10.1093/cid/cir504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Moore JE, McLernon P, Xu J, Murphy PG and Wareing D (2002) Characterisation of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter species isolated from human beings and chickens. The Veterinary Record 150, 518–520. 10.1136/vr.150.16.518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Uzunovic-Kamberovic S, Zorman T, Berce I, Herman L and Možina SS (2009) Comparison of the frequency and the occurrence of antimicrobial resistance among C. jejuni and C. coli isolated from human infections, retail poultry meat and poultry in Zenica-Doboj Canton, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Medicinski Glasnik 6, 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Frost I, Van Boeckel TP, Pires J, Craig J and Laxminarayan R (2019) Global geographic trends in antimicrobial resistance: The role of international travel. Journal of Travel Medicine 26, taz036. 10.1093/jtm/taz036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].World Health Organization (2019) Antimicrobial Resistance [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available at https://www.who.int/health-topics/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed 28 June 2022). [Google Scholar]

- [44].Council of Canadian Academies (2019) When Antibiotics Fail: The Expert Panel on the Potential Social-Economic Impacts of Antimicrobial Resistance in Canada [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Council of Canadian Academies. Available at https://cca-reports.ca/reports/the-potential-socio-economic-impacts-of-antimicrobial-resistance-in-canada/ (accessed 28 June 2022). [Google Scholar]

- [45].Otto SJG, Carson CA, Finley RL, Thomas MK, Reid-Smith RJ and SA McEwen (2014) Estimating the number of human cases of ceftiofur-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg in Quebec and Ontario, Canada. Clinical Infectious Diseases 59, 1281–1290. 10.1093/cid/ciu496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lloyd DH (2007) Reservoirs of antimicrobial resistance in pet animals. Clinical Infectious Diseases 45, S148–S152. 10.1086/519254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Pomba C, Rantala M, Greko C, Baptiste KE, Catry B, van Duijkeren E, Mateus A, Moreno MA, Pyörälä S, Ružauskas M, Sanders P, Teale C, Threlfall EJ, Kunsagi Z, Torren-Edo J, Jukes H and Törneke K (2016) Public health risk of antimicrobial resistance transfer from companion animals. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 72, 957––968. 10.1093/jac/dkw481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Seepersadsingh N andAdesiyun AA (2003) Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella spp. in pet mammals, reptiles, fish aquarium water, and birds in Trinidad. Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series B 50, 488–493. 10.1046/j.0931-1793.2003.00710.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Joseph LA, Watkins LKF, Chen J, Tagg KA, Bennett C, Caidi H, Folster JP, Laughlin ME, Koski L, Silver R, Stevenson L, Robertson S, Pruckler J, Nichols M, Pouseele H, Carleton HA, Basler C, Friedman CR, Geissler A, Hise KB and Aubert RD (2020) Comparison of molecular subtyping and antimicrobial resistance detection methods used in a large multistate outbreak of extensively drug-resistant Campylobacter jejuni infections linked to pet store puppies. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 58, e00771-20. 10.1128/jcm.00771-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Acke E, McGill K, Quinn T, Jones BR, Fanning S and Whyte P (2009) Antimicrobial resistance profiles and mechanisms of resistance in Campylobacter jejuni isolates from pets. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease 6, 705–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Olson CK, Ethelberg S, van Pelt W and Tauxe RV (2008) Epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni infections in industrialized nations. In Nachamkin I, Szymanski CM and Blaser MJ (eds), Campylobacter, 3rd edn. Washington, DC: ASM Press, pp. 163–189. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Founou LL, Founou RC and Essack SY (2016) Antibiotic resistance in the food chain: A developing country-perspective. Frontiers in Microbiology 7, 1881. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Maillard J-Y, Bloomfield SF, Courvalin P, Essack SY, Gandra S, Gerba CP, Rubino JR and Scott EA (2020) Reducing antibiotic prescribing and addressing the global problem of antibiotic resistance by targeted hygiene in the home and everyday life settings: A position paper. American Journal of Infection Control 48, 1090–1099. 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kaye KS, Harris AD, Samore M and Carmeli Y (2005) The case–case–control study design: Addressing the limitations of risk factor studies for antimicrobial resistance. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology 26, 346–351. 10.1086/502550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Harris AD, Carmeli Y, Samore MH, Kaye KS and Perencevich E (2005) Impact of severity of illness bias and control group misclassification bias in case–control studies of antimicrobial-resistant organisms. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology 26, 342–345. 10.1086/502549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Harris AD, Karchmer TB, Carmeli Y and Samore MH (2001) Methodological principles of case–control studies that analyzed risk factors for antibiotic resistance: A systematic review. Clinical Infectious Diseases 32, 1055–1061. 10.1086/319600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Torres NF, Chibi B, Kuupiel D, Solomon VP, Mashamba-Thompson TP and Middleton LE (2021) The use of non-prescribed antibiotics; prevalence estimates in low-and-middle-income countries. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Public Health 79, 2. 10.1186/s13690-020-00517-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Nadimpalli M, Delarocque-Astagneau E, Love DC, Price LB, Huynh B-T, Collard J-M, Lay KS, Borand L, Ndir A, Walsh TR, Guillemot D and Bacterial Infections and Antibiotic-Resistant Diseases among Young Children in Low-Income Countries (BIRDY) Study Group (2018) Combating global antibiotic resistance: Emerging one health concerns in lower- and middle-income countries. Clinical Infectious Diseases 66, 963–969. 10.1093/cid/cix879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Haynes E, Ramwell C, Griffiths T, Walker D and Smith J (2020) Review of antibiotic use in crops, associated risk of antimicrobial resistance and research gaps [Internet]. Report to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and the Food Standards Agency (FSA), FS301082. Available at https://www.food.gov.uk/research/antimicrobial-resistance/review-of-antibiotic-use-in-crops-associated-risk-of-antimicrobial-resistance-and-research-gaps.

- [60].McCubbin KD, Anholt RM, de Jong E, Ida JA, Nóbrega DB, Kastelic JP, Conly JM, Götte M, McAllister TA, Orsel K, Lewis I, Jackson L, Plastow G, Wieden HJ, McCoy K, Leslie M, Robinson JL, Hardcastle L, Hollis A, Ashbolt NJ, Checkley S, Tyrrell GJ, Buret AG, Rennert-May E, Goddard E, Otto SJG, Barkema HW (2021) Knowledge gaps in the understanding of antimicrobial resistance in Canada. Frontiers in Public Health 9, 726484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Schechner V, Temkin E, Harbarth S, Carmeli Y and Schwaber MJ (2013) Epidemiological interpretation of studies examining the effect of antibiotic usage on resistance. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 26, 289–307. 10.1128/cmr.00001-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Levin KA (2006) Study design III: Cross-sectional studies. Evidence-Based Dentistry 7, 24–25. 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Iskandar K, Molinier L, Hallit S, Sartelli M, Hardcastle TC, Haque M, Lugova H, Dhingra S, Sharma P, Islam S, Mohammed I, Mohamed IN, Hanna PA, Hajj SE, NAH Jamaluddin, Salameh P and Roques C (2021) Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in low- and middle-income countries: A scattered picture. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control 10, 63. 10.1186/s13756-021-00931-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A and McEwen SA (2014) A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods 5, 371–385. 10.1002/jrsm.1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268823000742.

click here to view supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

The search protocol and all extracted data are provided in the Supplementary Material. All the Supplementary Material is available on the Cambridge Core website.