Abstract

Background:

Chronic idiopathic patellofemoral pain is associated with patellar maltracking in both adolescents and adults. To accurately target the underlying, patient-specific etiology, it is crucial we understand if age-of-pain-onset influences maltracking.

Methods:

Twenty adolescents (13.9±1.4years) and 20 adults (28.1±4.9years) female patients with idiopathic patellofemoral pain (age-of-pain-onset: <14 and >18 years of age, respectively) formed the patient cohort. Twenty adolescents and 20 adults (matched for gender, age, and body mass index) formed the control cohort. We captured three-dimensional patellofemoral kinematics during knee flexion-extension using dynamic MRI. Patellar maltracking (deviation in patient-specific patellofemoral kinematics, relative to their respective age-controlled mean values) was the primary outcome measure, which was compared between individuals with adolescent-onset and adult-onset patellofemoral pain using ANOVA and discriminant analysis.

Findings:

The female adolescent-onset patellofemoral pain cohort demonstrated increased lateral (P=0.032), superior (P=0.007), and posterior (P<0.001) maltracking, with increased patellar flexion (P<0.001) and medial spin (P=0.002), relative to the adult-onset patellofemoral pain cohort. Post-hoc analyses revealed increased lateral shift [mean difference ± 95% confidence interval = −2.9± 2.1mm at 10° knee angle], posterior shift [−2.8±2.1mm, −3.3±2.3mm & −3.1±2.4mm at 10°, 20°& 30°], with greater patellar flexion [3.8±2.6mm & 5.0±2.8mm, at 20°& 30°] and medial spin [−2.2±1.7mm & −3.4±2.3mm at 20°& 30°]. Axial-plane maltracking accurately differentiated the patient age-of-pain-onset (60-75%, P<0.001).

Interpretation:

Age-of-pain-onset influences the maltracking patterns seen in patients with patellofemoral pain; with all, but 1, degree of freedom being unique in the adolescent-onset-patellofemoral pain cohort. Clinical awareness of this distinction is crucial for correctly diagnosing a patient’s pain etiology and optimizing interventional strategies.

Keywords: patellofemoral pain syndrome, knee, patella, magnetic resonance imaging, pediatric, kinematics, patellar maltracking, child

1. Introduction

Chronic patellofemoral (PF) pain is one of the most prevalent clinical diagnoses in orthopedic clinics, reported to affect 15%-33% of active adults and 21%-45% of adolescents (Boling et al., 2010; Callaghan and Selfe, 2007; DeHaven and Lintner, 1986; Rathleff et al., 2013). In general, physically active females experience a higher incidence of PF pain than males of the same age range and activity levels (Boling et al., 2010; DeHaven and Lintner, 1986; Wood et al., 2011). This pain can be debilitating for both athletes and the general populace, often leading to declines in physical health and higher levels of mental distress (Jensen et al., 2005; Naslund et al., 2006). Thus, designing appropriate patient-specific intervention plans for individuals with PF pain, through accurately diagnosing the underlying etiology, is crucial for maintaining the benefits of an active lifestyle and preventing future joint degeneration (Hunter et al., 2007; Moretz et al., 1984).

Patellar maltracking (pathological patellofemoral kinematics) is widely believed to play a role in the development and progression of PF pain in adults (Dupuy et al., 1997; MacIntyre et al., 2006; Taskiran et al., 1998; Wilson, 2009). In contrast, PF pain in adolescents is most often defined as a condition caused by overuse, and as such, it is viewed as a self-limiting condition (Fairbank et al., 1984; Goodfellow et al., 1976; Suzue et al., 2014). Recent work has called this into question (Rathleff et al., 2016). We now know that altered patellofemoral kinematics are associated with PF pain in adolescents (Carlson et al., 2017a) and that these altered tracking patterns persist unabated into adulthood (Carlson et al., 2017b). For adolescents, a rapidly developing musculoskeletal system combined with specialization in high intensity sports may expose them to various pathologies and injuries not typically seen in adults (Maffulli et al., 2011). Specifically, the open physes, rapidly changing mass distributions, fluctuating hormones, and underdeveloped neuromuscular control patterns in adolescents may lead to a patellar maltracking profile that is distinct from that seen in adult-onset PF pain. Thus, it is clinically important to understand if the underlying etiology or presentation of adolescent-onset PF pain is distinctive from adult-onset PF pain. A unique etiology would indicate that interventions designed for patients who develop PF pain as an adult may not be appropriate for those who develop PF pain in adolescence (O’Neill et al., 1992).

Despite the stark physical differences before and after pubescence, studies directly comparing patellar maltracking profiles between adolescents and adults with PF pain are lacking. Our recent review was unable to discern if the maltracking profile was unique in adolescents due to a limited focus on adolescents in past literature and the large methodological variability across studies (Grant et al., 2020). This review noted that even for the adult population, where a plethora of studies focused on patellar maltracking/malalignment, developing a unifying patellar maltracking profile remains difficult due to the methodological variability across studies. For example, numerous studies enroll only adults (Erkocak et al., 2015; MacIntyre et al., 2006; Pal et al., 2012; Souza et al., 2010; Taskiran et al., 1998), but some use a mixed population of adults and adolescents (Becher et al., 2017; Brossmann et al., 1993; Powers, 2000; Sasaki and Yagi, 1986; Witonski and Goraj, 1999). The latter studies rest on the untested assumption that patellar maltracking is no different between adolescents and adults. Thus, to provide greater clarity in research and improve the short- and long-term treatment outcomes for patients with adolescent-onset PF pain, studies exploring the potential etiological differences between patients who develop isolated PF pain in adolescence versus those that develop it in adulthood are needed.

The purpose of this study is to compare patellofemoral tracking patterns in all six degrees of freedom between a cohort of adolescent females with PF pain (pain-onset prior to 14th birthday) and a cohort of adult females who developed isolated PF pain (pain-onset after 18th birthday). The primary measure of interest is patellar maltracking (the deviation in the patellofemoral kinematic profiles of patients with PF pain from their respective age-matched control cohort mean values). Using this measure we tested the null hypothesis that the maltracking patterns in adolescent-onset PF pain are no different than those observed in adult-onset PF pain.

2. Methods

2.1. Participant Recruitment

Data for this study was collected from May 2008 - January 2018 (convenience sampling) as part of an IRB-approved protocol. This single-center case-control study was conducted at the Clinical Center of the National Institutes of Health. All participants entered the study through self-referral. Clinicaltrials.gov, flyers, and word-of-mouth were used to advertise the study. Orthopaedic sports medicine practices, physical therapy clinics, and primary care offices in the greater Washington, DC region were provided the flyers. In total, the kinematic data for 10 adolescents with PF pain, 11 adolescent controls, 5 adults with PF pain and 3 adult controls have been included in previous studies that reported the PF kinematics in adolescent [8] and adult [45, 46] patients with PF pain. As, the aim of the current study is to compare the adolescent- and adult-onset maltracking patterns, these inclusions do not constitute a republishing of data.

2.2. Participant Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Data for 20 female adolescents (age=13.9 ± 1.4 years) who developed clinically diagnosed PF pain prior to their 14th birthday and 20 knees from asymptomatic adolescent females (adolescent controls) formed the adolescent arm of the current study (Table 1). Twenty adult females (age=28.1±4.9 years) who developed clinically diagnosed PF pain after their 18th birthday; and 20 asymptomatic female adults (adult controls) formed the adult arm of the study (Table 1). We matched controls to patients with PF pain for age (within 6 and 12 months for adolescents and adults, respectively) and body mass index (BMI, within 5 kg/m2). Data for patients with PF pain were entered into the study chronologically. When multiple control participants were available as an age match to a single individual with PF pain, the control that was within the appropriate age range and had the closet BMI match was selected (Table 2).

Table 1. Mean (standard deviation) participant demographics and clinical intake parameters.

P-values are listed in the final column. In the top portion of the graph the P-values represent the comparison between the cohort with patellofemoral pain and the control cohort. The comparison was done for each age bracket independently. Thus, the P-value for the adult bracket is given first, then the P-value for the adolescent bracket is provided after the backslash. For the bottom portion of the graph, the P-value represents the comparison across age brackets for the cohort with patellofemoral pain.

| Adult | Adolescent | P-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| PFP | Control | PFP | Control | |||

|

|

|

|||||

| Knees (N) | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | NA | |

| Participants (n) | 20 | 20 | 20 | 16 | NA | |

| Age (years) | 28.1 (4.9) | 28.0 (4.8) | 13.9 (1.4) | 13.8 (1.3) | 0.95/0.67 | |

| (range) | 21.8-37.6 | 22.4-37.2 | 10.3-16.3 | 10.3- 16.0 | ||

| Weight (kg) | 61.4 (8.9) | 60.3 (8.2) | 50.1 (7.3) | 50.6 (8.6) | 0.71/0.84 | |

| Height (cm) | 164.4 (5.8) | 166.3 (7.8) | 161.0 (8.0) | 159.1 (10.0) | 0.38/0.52 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.7 (2.7) | 21.8 (2.8) | 19.3 (2.3) | 19.9 (2.4) | 0.33/0.43 | |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|||||

| J-sign (n)* | 8Y/11N | NA | 15Y/4N | NA | 0.04 | |

| Q-angle (°) | 16.7 (4.5) | NA | 13.4 (3.6) | NA | 0.01 | |

| Lat. Hypermobility (mm)* | 6.8 (3.6) | NA | 7.2 (3.8) | NA | 0.92 | |

| Kujala Score | 73.8 (14.3) | NA | 64.5 (12.5) | NA | 0.15 | |

| VAS (typical day) | 37.4 (18.6) | NA | 43.3 (24.2) | NA | 0.41 | |

| VAS (during activities that invoke pain) | 67.4 (22.2) | NA | 73.9 (18.0) | NA | 0.37 | |

| Length of Pain (years) | 3.9 (3.0) | NA | 2.4 (1.9) | NA | 0.09 | |

Unable to measure certain subject in each cohort due to positive apprehension test.

Table 2: Exclusion criteria leading to excluded data.

This table lists the subject counts for subjects that were enrolled into the study, but excluded from final data analysis. Potential participants were provided with the study inclusion/exclusion criteria prior to enrollment. No data were collected on individuals who opted not to participate and as such are not represented in the numbers below. Numerous young adolescents found the repeated extension-flexion motion too difficult and opted to only participate in the static portion of the study.

| Patients with adolescent-onset patellofemoral pain | |

| 2 | No matching control data |

| 3 | Other pathologies: history of dislocation |

| 1 | Other pathologies: frozen knee |

| 2 | Poor movement - data not analyzable |

| 1 | Only static images acquired |

| Adolescent Controls | |

| 2 | Kinematics were > 3 SD from control Average |

| 1 | complained of recent knee pain |

| 3 | Poor movement - data not analyzable |

| 11 | Static Data Collection Only |

| Patients with adult-onset patellofemoral pain | |

| Adult PFP | |

| 3 | No matching control data |

| 4 | Other pathologies: history of dislocation |

| 1 | Other pathologies: swollen knee |

| 2 | Other pathologies: meniscal tear found |

| 3 | Other pathologies: OA found |

| 3 | Pain prior to 18 years of age |

| 1 | Only static images acquired |

| 1 | Lack of clinical diagnosis of PF pain |

| 1 | Poor movement - data not analyzable |

| Adult Control | |

| 30 | Better Match used |

| 2 | Poor Movement - not analyzable |

All participants with clinically diagnosed PF pain had symptoms for a minimum of 6 months with a current pain level during activities that evoke PF pain greater than 30/100 on a visual analog scale (VAS) (Price et al., 1983). If bilateral pain existed, the knee with the highest numeric VAS score was selected for inclusion. If a participant had equal pain bilaterally, then the knee with (in descending order) the largest lateral hypermobility, the presence of a J-sign, or the largest Q-angle was selected. As fusion of the femoral epiphyseal plate typically occurs between 14-17 years in adolescent females (Neuhauser, 1957; O’Connor et al., 2008), we assigned patients to the adult cohort with PF pain only if they reported pain-onset after their 18th birthday. Further, due to the greater potential for osteoarthritis (OA) in later adulthood, adults over 40 were excluded from the study.

The current study focused exclusively on PF pain using the strict definition of peripatellar pain in the absence of clear structural pathologies, prior dislocations, or trauma. Thus, we excluded knees from all cohorts that had previous major lower limb injury, pathology, arthritis, surgery; traumatic onset of PF pain; prior patellar dislocations (either self-reported or clinically documented); and hypermobility (defined as a Beighton score (Smits-Engelsman et al., 2011) of >5 or genetically/ clinically diagnosed generalized joint laxity, such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome). These exclusion criteria extended to both legs, with the exception that patients with patellofemoral pain who had previous dislocation or arthroscopy on the non-study leg were not excluded. We excluded any potential participant demonstrating contraindications to MR imaging. We excluded any control reporting current knee pain or a previous diagnosis of PF pain. The control knee studied was selected randomly.

2.3. Consent & Physical Exam

All participants provided informed consent or, if they were under 18 years of age, assent, with a parent or guardian providing written consent prior to enrollment. Next, an in-house physiatrist or nurse practitioner took a medical history and performed a physical exam. This was followed by a targeted knee evaluation, inclusive of Q-angle, lateral hypermobility score, and J-sign; conducted by either an in-house physical therapist of physiatrist. We used the Kujala score (Kujala et al., 1993) and a VAS to assess subjective pain levels.

2.4. Dynamic MR Imaging

As previously described (Seisler and Sheehan, 2007), we quantified 3D patellofemoral kinematics from data acquired noninvasively using dynamic cine phase contrast (CPC) MR imaging during volitional knee flexion-extension. This technique captures 3D joint kinematics to an accuracy of 0.3 mm (Behnam et al., 2011). Participants laid supine in a 3-Tesla MR scanner (Philips Electronics, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) with the knee stabilized by a custom rig. We positioned two pairs of flex-coils medial-laterally and anteriorly to the knee to enhance image quality. A cushioned block placed under the distal thigh provided support while participants extended their knee, against gravity, from approximately 40 degrees flexion to full extension and back (30 cycles/min). Using CPC MR imaging, dynamic anatomic images along with x, y, z velocity data were captured at even temporal increments during the movement. Each CPC acquisition required the participant to sustain this exercise for approximately 1.5 minutes. The captured temporal resolution was 80.4msec (24.8 true frames of data). The data were interpolated to 32 time frames using the raw Fourier data. An optical trigger synchronized the data collection to the motion cycle. We quantified 3D rigid body rotations and translations of the femur, tibia, and patella during knee extension by integrating the CPC velocity data. We then scaled all translational measurements using individual epicondylar width to account for size variations (Seisler and Sheehan, 2007) and interpolated data to single knee angle increments for statistical analysis.

2.5. Anatomic Measurements

We measured patellar and tibial tracking relative to the femur using an anatomic coordinate system (Figure 1) constructed for each bone (Seisler and Sheehan, 2007). For the current study a knee angle of 10° is equivalent to full knee extension measured clinically using the hip, knee, and ankle centers of rotation (Freedman et al., 2014). Medial, superior, and anterior shift defined positive displacements. Three-dimensional mechanics convention (Mitiguy, 2011) established the rotation angles, with the order of positive rotation being flexion, medial tilt, and lateral spin (i.e., lateral spin is a varus rotation, which causes the superior pole of the patella to move laterally). We quantified the maltracking parameters for each participant in a PF pain cohort as the difference in each displacement and rotation variable relative to the mean from the age-matched control cohort. Thus, when visualizing maltracking graphically, the control mean is always zero. Axial plane tracking (Figure 1) consisted of medial-lateral shift and tilt of the patella relative to the femur.

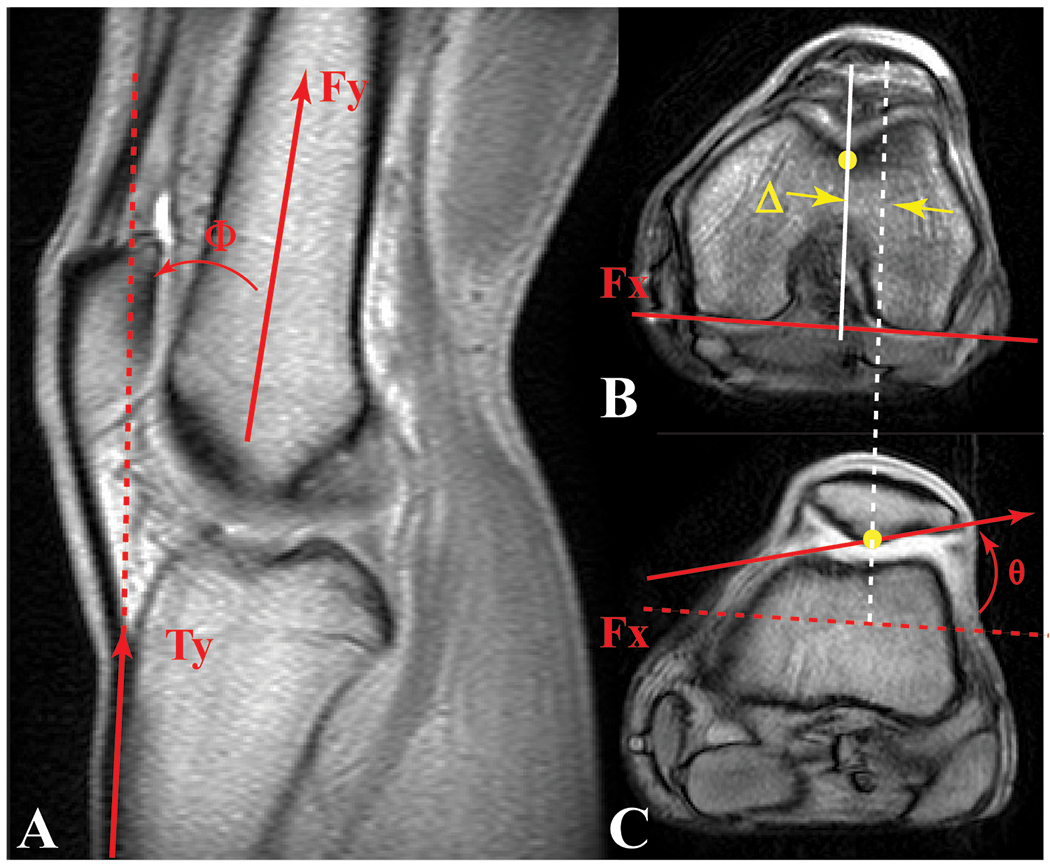

Figure 1. Knee Angle, Lateral Patellar Shift, and Lateral Patellar Tilt.

A) Knee angle (Φ: the angle between a vector bisecting the distal femoral shaft and a vector parallel to the proximal anterior edge of the tibia) was measured in the full extension anatomical, sagittal, cine phase contrast image. A 10° knee angle measured on an MR image corresponded to a 0° clinical knee angle, measured using the hip, knee, and ankle (Freedman and Sheehan, 2013). Axial cine images for full extension at the B) level of the femoral epicondyle and C) mid-patellar level. Medial-lateral patellar shift (Δ) was defined as the distance from the patellar origin (most posterior patellar point on this image) to the femoral origin (deepest point in the sulcus at the level of the femoral epicondyle [B]), in the direction parallel to the posterior edge of the femur (Fx at the level of the femoral epicondyle [B]). Patellar tilt (θ) was defined as the angle between Fx and the lateral-posterior patellar edge. These three parameters (along with all patellofemoral superior, posterior displacement, flexion, and lateral spin) were then tracked throughout the motion cycle using the kinematic data derived from cine phase contrast MR imaging.

2.6. Static MR Imaging

We acquired static gradient recalled echo (GRE), fat-saturated GRE, and proton density weighted images of the knee using an 8-channel knee coil with lower limb in the anatomically neutral position. An in-house radiologist reviewed all images to rule out any potential undiagnosed knee pathology in both the PF pain and control cohorts. If the radiologist documented any potential patellar, femoral, or tibial cartilage defects, the case was referred to the senior musculoskeletal radiologist for grading according to the International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) criteria (Brittberg and Winalski, 2003). We excluded knees with a grade larger than zero from the study (Table 2).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

An a priori power test revealed that 19 participants were needed for each cohort. This was based on the previously reported adolescent lateral shift maltracking value of 3.4±3.0 mm, and assumed difference of 2.5 mm between the current adolescent and adult cohorts, an alpha of 0.05, and a beta of 0.8. Prior to any statistical tests, we assessed normality of the data through a Shapiro-Wilk Test. We compared age, height, weight, and BMI between the cohort with pain and the control cohort for each age subgroup using an independent two-tailed Student’s t-test, assuming equal variances. Similarly, we compared the Q-angle, patellar lateral hypermobility, and VAS score across both cohorts diagnosed with PF pain using an independent two-tailed Student’s t-test. The Kujala score was not normally distributed, thus a Mann-Whitney U test was used. We determined if a greater number of J-signs were present in one cohort with PF pain, relative to the other, using a Fisher’s test. To provide context for the primary study question (difference in maltracking based on age-of-pain onset), the kinematics in the adolescent-onset and adult-onset PF pain cohort were compared to their respective control cohorts using a Student’s t-test. A P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. Effect size was measured using Hedges’ g-statistic with bias correction. Small, medium, and large effect are defined as g=0.00-0.32, g=0.33-0.55, and g=0.56-1.20 (Lipsey, 1990).

We evaluated maltracking parameters using a two-way ANOVA with cohort (adolescent-onset and adult-onset PF pain) and knee angle (10°, 20°, 30°) as main effects, after ensuring data normality and homogeneity. If there were main effects or significant interaction effects, we used a Student’s t-test for the post-hoc analysis. We performed a discriminant analysis (stepwise Wilks’ lambda), to quantify the degree of cohort separation based on age-of-pain-onset (adolescent or adult).

3. Results

Age, height, weight, and BMI were no different between the control cohort and the cohort diagnosed with PF pain in both adolescents and adults (Table 1). All adolescent participants, except one patient, had open femoral physes. The adolescent-onset PF pain cohort demonstrated significant lateral shift (10°, 20° & 30° knee flexion) and patellar flexion maltracking (30° knee flexion); whereas the adult-onset PF pain cohort demonstrated significant lateral tilt (10° & 20° knee flexion), medial spin (10° knee flexion) and anterior displacement (10° & 20° knee flexion), relative to their respective age-matched control cohorts (Appendix). Among PF pain cohorts, there were no differences in patellar lateral hypermobility. The Q-angle was lower (Δ = −3.3°, P =0.01, d=0.709) and there was an increase in the number of J-signs in the adolescent population (+7, P=0.04) in the adolescent-onset PF pain cohort, relative to the adult-onset PF pain cohort. The length of pain, Kujala, and VAS scores were not different between the two cohorts with PF pain.

Cohort was a main effect; patients with adolescent-onset PF pain demonstrated a maltracking profile that was unique from those with adult-onset PF pain in all degrees of freedom, but one. Thus, the null hypothesis was rejected. Adolescents with PF pain had more lateral (P =0.032), superior (P =0.007) and posterior (P <0.001) patellar maltracking with greater flexion (P < 0.001) and medial spin (P = 0.002) relative to the patients with adult-onset PF pain, across the three knee angles tested (Figure 2). A post-hoc analysis revealed that the adolescent cohort with patellofemoral pain demonstrated increased lateral shift at a knee angle of 10° [mean difference ± 95% confidence interval = −2.8± 2.1mm, P=0.014, g= −0.81] and posterior shift [mean difference = −2.6±2.1mm, −3.3±2.3mm & −3.1±2.4mm; P =0.019, 0.009 & 0.014; g= −0. 77, −0.87 & −0.81; for knee angles of 10°, 20 °& 30°], with greater patellar flexion [mean difference = 3.8±2.6mm & 5.0±2.8mm; P =0.008 & 0.001; g= 0.89 & 1.01; for knee angles of 20°& 30°] and medial spin [mean difference = −2.2 ±1.7 mm & −3.4±2.3mm; P =0.013 & 0.006; g= −0.82 & −0.93; for knee angles of 20°& 30°]. There were no difference in lateral tilt maltracking between cohorts. No differences in alta at individual knee angles was found. No interaction effects were found between age-of-pain-onset and knee angle.

Figure 2. Comparing Maltracking Patterns between Adolescents and Adults with PFP:

Red solid line: The average difference in tracking between the adolescent cohort with PF pain and the adolescent control cohort (maltracking). Blue dashed line: The average difference in tracking between the adult cohort with PF pain and the adult control cohort (adult-onset maltracking). Red solid line: The average difference in tracking between the adolescent cohort with PF pain and the adolescent control cohort (adolescent-onset maltracking). Bars representing one standard deviation (SD) from the average are provided at each knee angle analyzed in the ANOVA. Stars (*) indicate significant differences in a maltracking variable across age brackets. The “at” symbol (@) indicates a significant ANOVA results without significant differences at individual knee angles. As maltracking is the differential tracking from the control average, the control average for each cohort is represented by a horizontal line at zero.

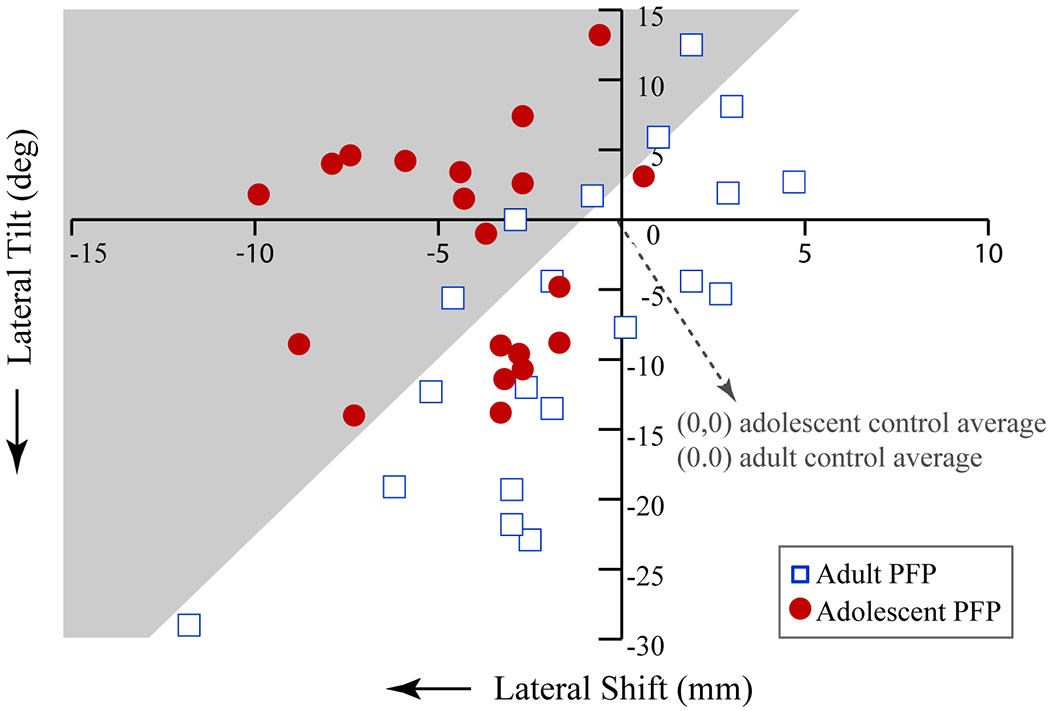

Discriminant analysis kept only axial-plane maltracking (shift and tilt) to differentiate the age-of-onset of patients with PF pain, with an accuracy of 75% and 60% for the adult and adolescent cohorts, respectively (Figure 3). Lateral shift was entered in the first step (P=0.008) and tilt was entered at the second step (P<0.001). This discrimination was based on the patellae in the adolescent-onset PF pain cohort displaying significant lateral shift with minimal lateral tilt, relative to their control cohort, whereas patellae in the adult-onset PF pain cohort tracked with a significant lateral tilt without large lateral shift, relative to their control cohort (Appendix). The pattern of medial shift with medial tilt was typically only seen in the adult population with PF pain; twenty-five percent of patients with adult-onset PF pain demonstrated this pattern. Whereas, lateral shift with medial tilt was typically only seen in patients with adolescent-onset PF pain; forty-five percent of patients with adolescent-onset PF pain demonstrated this pattern. Six patients with adolescent-onset PF pain demonstrated “extreme” lateral maltracking (> 2 SD from the control mean) (Carlson et al., 2017a).

Figure 3. Axial Maltracking Discriminant Analysis.

The discriminant analysis predicted cohort affiliation with a 60% and 75% accuracy (P < 0.001), based on the kinematic profile terminal knee extension (10° knee angle) of participants with patellofemoral pain, relative to their respective age-matched control cohorts. The analysis kept medial-lateral shift (x-axis) and tilt (y-axis), while removing superior displacement, anterior displacement, flexion, and lateral spin. The coordinates (0, 0) reflect the average medial-lateral shift and tilt for the age-, sex-, and BMI-matched control cohort for each age-bracket. Each red circle represents the deviation in tracking from the adolescent control average for each adolescent subject with patellofemoral pain, whilst the open blue squares represents the deviation in tracking from the adult control average for each adult subject with patellofemoral pain. The grey area represents the region of adolescent maltracking, based on the discriminant analysis.

4. Discussion

This study expands our knowledge of PF pain, demonstrating that the maltracking in adolescents with PF pain (Carlson et al., 2017a) not only persists into adulthood (Carlson et al., 2017b), but is statistically unique from the maltracking pattern seen in individuals who develop PF pain as adults. Thus, age-of-pain-onset is a key factor in the etiology of PF pain, which must be considered in clinical patient evaluation and when designing future research. Current clinical interventions for PF pain, typically developed for adult-onset PF pain, may not be applicable for patients with adolescent-onset PF pain. For example, most adolescents with persistent PF pain will be better served with treatments that focus on minimizing lateral shift (Diks et al., 2003; Koeter et al., 2007; Rillmann et al., 2000). In contrast, interventions focused on correcting excessive lateral tilt (Fulkerson, 2002) may be better suited for patients with adult onset PF pain.

One of the strongest supports for adolescent-onset PF pain being unique from adult-onset PF pain is the work of O’Neill and colleagues (O’Neill et al., 1992). This group evaluated the effectiveness of quadriceps strengthening in skeletally immature (age 10-17 years, males & females) and skeletally mature (age 17-43 years, males & females) patients with PF pain. The congruence angle was more lateral in the skeletally immature, relative to the skeletally mature cohort (~6° and ~2.5°, respectively) before exercise therapy. This agrees with the current conclusions that female adolescents with PF pain tend to have more laterally shifted maltracking pattern than those with adult-onset PF pain. O’Neill and colleagues reported that the quadriceps exercise protocol resulted in patellar medialization in skeletally immature patients with PF pain, but lateralization in adults with PF pain, highlighting the fact that the same treatment had distinct kinematic effects on adolescents and adults.

Comparison to relevant literature, based on the standard mean difference (SMD or effect size), provides external validation for our accuracy in being able to discriminate age-of-pain-onset from axial plane maltracking (Figure 4). Differences in kinematic metrics for measuring maltracking makes direct comparison of results with past studies impossible (Grant et al., 2020). On average, the lateral shift maltracking SMD is smaller and lateral tilt maltracking SMD is slightly larger in adults with isolated PF pain (Erkocak et al., 2015; MacIntyre et al., 2006; Pal et al., 2012; Taskiran et al., 1998), relative to the current cohort with adolescent-onset PF pain (Figure 4). The study by MacIntyre et al. is the only study where the lateral tilt maltracking SMD is smaller in an adult-onset PF pain cohort, compared to our current adolescent-onset PF pain cohort. All participants in this previous cohort were males in the military, which may have influenced their results. Ultimately, future studies expanding our knowledge of maltracking and its etiology in patients with adolescent-onset PF pain are needed to confirm the present results and to provide a fuller understanding of its etiology.

Figure 4. Inter-study comparison for axial plane patellar maltracking in terminal extension.

The standard mean difference (SMD, based on the Hedge’s g) for all studies, excluding the present, were acquired from our previous review (Grant et al., 2020). The SMD was calculated at a knee angle of 10° in the current study and in terminal extension (knee angle≤10°) for previous studies. The x-axis/y-axis is the SMD for PF shift/tilt maltracking (difference between shift/tilt in PF pain cohort and control cohort. The 95% confidence interval is represented by horizontal (shift) and vertical (tilt) error bars. Studies without clear reporting of cohort age were excluded from this graph. Two other studies (Carlson et al., 2017a; Carlson et al., 2017c) were excluded, as some data were shared between these previous studies and the current study. Red filled diamond: SMD for the comparison of current adolescent-onset PF pain participants to adolescent control average. Green filled triangle: SMD for the comparison of current adult-onset PF pain participants to control average. Green open symbols: Studies comparing a control cohort to a cohort with isolated PF pain (Erkocak et al., 2015; MacIntyre et al., 2006; Pal et al., 2012; Taskiran et al., 1998). Studies not focused on adults in isolation were excluded. Blue filled symbols: Studies comparing a control cohort to a cohort with PF pain secondary to a history of patellar dislocation (Becher et al., 2017; Brossmann et al., 1993; Regalado et al., 2013; Taskiran et al., 1998). Regaldo and colleagues (2013) focused solely on adolescents with a history of dislocation, while the others limited their cohorts to participants aged 16 or older.

As five of the six degrees of freedom demonstrated differences (with large effect sizes) between the patient groups, future research and clinical work is needed to identify the relationships between PF pain and maltracking outside of the axial plane. The tendency towards patellar flexion with alta in adolescent-onset and extension with baja in adult-onset PF pain, led to the significant maltracking differences between patient cohorts for these variables. This may indicate a tendency toward hyper-mobility in adolescent-onset PF pain, and hypo-mobility in adult onset PF pain (Sheehan et al., 2012a). In addition, the difference in the spin maltracking and differences in the change in spin relative to the knee angle between the adolescent-onset and adult-onset PF pain would clearly foster unique sheer force patterns on the cartilage. Further research is needed to determine the extent of the variation in sheer and if such sheer forces may establish a pathway from PF pain to osteoarthritis (Hunter et al., 2007; Moretz et al., 1984).

Interestingly, the standard mean difference (SMD, effect size) for lateral shift in the current adolescent population (Figure 4) was on par with the average effect size for previous measures in patients with PF pain secondary to a history of patellar dislocation (Becher et al., 2017; Brossmann et al., 1993; Regalado et al., 2013; Taskiran et al., 1998). However, the effect size for tilt was much lower than that observed in individuals with PF pain secondary to dislocation. This ability for our adolescents to have an “extreme lateral shift” pattern (Carlson et al., 2017a) that does not promote dislocation or lead to future dislocation (Carlson et al., 2017b) is potentially due to patellofemoral shape. Maltracking in adolescents with isolated PF pain is correlated with both patellar and femoral shape parameters (Fick et al., 2020). Lateral shift correlates with lateral shaft length, patella-height ratio, and Wiberg index, while lateral tilt correlates with patellar-height ratio in adolescents with isolated PF pain. A higher sitting patella with a shorter lateral shaft length and elongated lateral patellar edge is able to shift more laterally, while remaining stabilized within the groove. The lateral femoral trochlea was not diminished in our adolescents with isolated PF pain, which likely inhibited excessive lateral tilt. Potential alterations in soft-tissue forces (Sheehan et al., 2012b) would contribute to lateral shift and spin moments while fostering a stress concentration on the longer lateral patellar facet. This is a likely genesis for PF pain experienced by our adolescents. Further investigation into the typical development of neuromuscular control and patellofemoral shape during childhood is needed to better understand the etiology of isolated PF pain and maltracking in adolescents.

The primary limitation of this study, despite being adequately powered and having a sample size greater than 64% of past studies of maltracking (Grant et al., 2020), is that the data likely do not represent the entire population of individuals with PF pain. Further, data from both knees of 4 adolescent controls were included within the study, due to the tight matching criteria imposed on the adolescent cohort. All other cohorts used a single knee from each participant. Since there is little correlation in tracking parameters across paired knees in controls (unpublished data), this should not affect the statistical analysis or study conclusions. When these 4 control knees were removed, the results did not change. We intentionally focused the study on females (Boling et al., 2010). As such, we could not explore the confounding effects of sex on maltracking. Further, the study used a strict definition of PF pain, limiting our ability to apply our conclusion to PF pain from known causes (e.g., dislocation, OA, etc.)

5. Conclusion

As the age-of-pain-onset influences the maltracking patterns seen in patients with PF pain, clinical awareness of this distinction is crucial for correctly diagnosing the etiology of a patient’s pain and for developing appropriate interventional plans. As evidence by earlier work (O’Neill et al., 1992), patients with adolescent with PF pain have distinct responses, relative to adults with PF pain, when treated using interventions developed primarily for adult-onset PF pain. Thus, the interventional approach to adolescent-onset PF pain must be re-evaluated and tailored to this unique group of patients. In terms of research, age-of-pain-onset is clearly a key demographic characteristic that must be controlled for when designing and executing studies evaluating patients with isolated PF pain.

Highlights.

This study demonstrates that the maltracking pattern identified in females with adolescent-onset PFP is unique from the maltracking pattern seen in individuals who develop PFP as adults. Adolescents with PF pain had more lateral, superior and posterior patellar maltracking with greater flexion, relative to the patients with adult-onset PF pain.

The results suggest interventions for PFP based on the age-of-pain-onset are likely more effective than a generalized approach.

As age-of-pain-onset influences the observed maltracking pattern, age-of-pain-onset should be controlled for in future research.

6. Acknowledgements:

We thank Diane Damiano, PhD, Judith Welsh, and Cindy Clark for their help and support in the work. In addition, we would like to thank the Radiology Department at the Clinical Center of the National Institutes of Health for their support of this work. This work was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, Bethesda, MD, USA and the Medical Research Scholars Program (https://fnih.org/what-we-do/current-education-and-training-programs/mrsp).

Appendix

Table A1:

Patellofemoral kinematics for the adult-onset and adolescent-onset cohort

|

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADULT | ADOLESCENT | |||||

|

|

||||||

| MEDIAL-LATERAL SHIFT (medial = +) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Knee angle | Pain | Control | ΔX |

Pain | Control | ΔX |

| 10 | −1.6 (3.9) | −0.2 (2.5) | −1.4 | −3.7 (2.8) | 0.4 (2.6) | −4.2** |

| 20 | 0.1 (3.8) | 1.9 (1.9) | −1.8 | −0.7 (1.9) | 1.9 (2.2) | −2.6** |

| 30 | 0.9 (3.7) | 2.4 (2.1) | −1.5 | 0.4 (2.3) | 2.1 (2.2) | −1.6* |

|

| ||||||

| INFERIOR-SUPERIOR DISPLACEMENT (superior = +) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Knee angle | Pain | Control | ΔY |

Pain | Control | ΔY |

| 10 | 22.4 (5.5) | 23.1 (5.2) | −0.7 | 25.6 (7.4) | 23.4 (4.9) | 2.2 |

| 20 | 12.5 (6.5) | 15.2 (5.2) | −1.3 | 17.6 (7.3) | 15.5 (5.2) | 2.1 |

| 30 | 7.5 (6.5) | 8.9 (5.5) | −1.6 | 9.0 (6.8) | 7.0 (5.0) | 2.0 |

|

| ||||||

| ANTERIOR-POSTERIOR SHIFT (anterior = +) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Knee angle | Pain | Control | ΔZ |

Pain | Control | ΔZ |

| 10 | 9.6 (3.7) | 7.5 (2.2) | 2.2* | 7.8 (3.1) | 8.3 (2.2) | −0.5 |

| 20 | 11.4 (3.9) | 9.3 (2.3) | 2.1* | 9.6 (3.7) | 10.8 (2.6) | −1.2 |

| 30 | 11.0 (3.5) | 9.3 (1.7) | 1.6 | 9.7 (4.1) | 11.2 (3.0) | −1.5 |

|

| ||||||

| FLEXION | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Knee angle | Pain | Control | Δ theta1 |

Pain | Control | Δ theta1 |

| 10 | 7.5 (3.5) | 7.4 (4.2) | 0.1 | 6.8 (2.9) | 6.3 (3.2) | 0..5 |

| 20 | 11.0 (4.6) | 12.4 (5.1) | −1.3 | 11.3 (3.8) | 8.9 (4.7) | 2.4 |

| 30 | 16.7 (5.0) | 18.8 (6.5) | −2.1 | 17.8 (4.1) | 15.0 (6.1) | 2.8* |

|

| ||||||

| TILT (medial = +) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Knee angle | Pain | control | Δ theta2 |

Pain | Control | Δ theta2 |

| 10 | 5.6 (11.3) | 12.9 (7.7) | −7.2* | 12.4 (7.9) | 14.7 (6.5) | −2.3 |

| 20 | 8.8 (13.5) | 16.2 (8.7) | −7.1* | 15.1 (5.4) | 18.9 (8.7) | −3.8 |

| 30 | 9.4 (12.1) | 14.3 (7.0) | −4.3 | 15.7 (5.5) | 20.6 (10.6) | −4.8 |

|

| ||||||

| VARUS | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Knee angle | Pain | Control | Δtheta3 | Pain | Control | Δtheta3 |

| 10 | −0.7 (2.3) | 0.7 (1.4) | −1.4* | −0.3 (1.9) | 0.0 (1.6) | −0.3 |

| 20 | −0.4 (2.8) | −0.3 (2.8) | −0.1 | −0.9 (2.5) | 0.4 (2.7) | −1.3 |

| 30 | 0.6 (4.3) | 0.4 (3.8) | 0.2 | −0.9 (3.0) | 0.8 (2.9) | −1.7 |

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None to report for any author.

Ethical Review: This study was approved by the IRB office of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Work Performed: All experimental data collection and analysis was done at the Functional and Applied Biomechanics section, Rehabilitation Medicine Department of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Study Design: Level III Cohort study

Contributor Information

Aricia Shen, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA

Barry P. Boden, The Orthopaedic Center, Rockville, MD, USA

Camila Grant, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA

Victor R. Carlson, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA

Jennifer N. Jackson, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA

Katharine E. Alter, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA

Frances T. Sheehan, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA

7. References

- Becher C, Fleischer B, Rase M, Schumacher T, Ettinger M, Ostermeier S, Smith T, 2017. Effects of upright weight bearing and the knee flexion angle on patellofemoral indices using magnetic resonance imaging in patients with patellofemoral instability. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 25, 2405–2413. 10.1007/s00167-015-3829-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnam AJ, Herzka DA, Sheehan FT, 2011. Assessing the accuracy and precision of musculoskeletal motion tracking using cine-PC MRI on a 3.0T platform. J Biomech 44, 193–197. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.08.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boling M, Padua D, Marshall S, Guskiewicz K, Pyne S, Beutler A, 2010. Gender differences in the incidence and prevalence of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Scand J Med Sci Sports 20, 725–730. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00996.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittberg M, Winalski CS, 2003. Evaluation of cartilage injuries and repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am 85-A Suppl 2, 58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brossmann J, Muhle C, Schroder C, Melchert UH, Bull CC, Spielmann RP, Heller M, 1993. Patellar tracking patterns during active and passive knee extension: evaluation with motion-triggered cine MR imaging. Radiology 187, 205–212. 10.1148/radiology.187.1.8451415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan MJ, Selfe J, 2007. Has the incidence or prevalence of patellofemoral pain in the general population in the United Kingdom been properly evaluated? Phys Ther Sport 8, 37–43. 10.1016/j.ptsp.2006.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson VR, Boden BP, Sheehan FT, 2017a. Patellofemoral Kinematics and Tibial Tuberosity-Trochlear Groove Distances in Female Adolescents With Patellofemoral Pain. Am J Sports Med 45, 1102–1109. 10.1177/0363546516679139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson VR, Boden BP, Shen A, Jackson JN, Alter KE, Sheehan FT, 2017b. Patellar Maltracking Persists in Adolescent Females With Patellofemoral Pain: A Longitudinal Study. Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine 5, 2325967116686774. 10.1177/2325967116686774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson VR, Sheehan FT, Shen A, Yao L, Jackson JN, Boden BP, 2017c. The Relationship of Static Tibial Tubercle-Trochlear Groove Measurement and Dynamic Patellar Tracking. Am J Sports Med 45, 1856–1863. 10.1177/0363546517700119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeHaven KE, Lintner DM, 1986. Athletic injuries: comparison by age, sport, and gender. Am J Sports Med 14, 218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diks MJF, Wymenga AB, Anderson PG, 2003. Patients with lateral tracking patella have better pain relief following CT-guided tuberosity transfer than patients with unstable patella. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 11, 384–388. 10.1007/s00167-003-0415-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy DE, Hangen DH, Zachazewski JE, Boland AL, Palmer W, 1997. Kinematic CT of the patellofemoral joint. AJR Am J Roentgenol 169, 211–215. 10.2214/ajr.169.1.9207527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkocak OF, Altan E, Altintas M, Turkmen F, Aydin BK, Bayar A, 2015. Lower extremity rotational deformities and patellofemoral alignment parameters in patients with anterior knee pain. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 10.1007/s00167-015-3611-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB, van Poortvliet JA, Phillips H, 1984. Mechanical factors in the incidence of knee pain in adolescents and young adults. J Bone Joint Surg Br 66, 685–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick CN, Grant C, Sheehan FT, 2020. Patellofemoral Pain in Adolescents: Understanding Patellofemoral Morphology and Its Relationship to Maltracking. Am J Sports Med 48, 341–350. 10.1177/0363546519889347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman BR, Brindle TJ, Sheehan FT, 2014. Re-evaluating the functional implications of the Q-angle and its relationship to in-vivo patellofemoral kinematics. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 29, 1139–1145. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2014.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman BR, Sheehan FT, 2013. Predicting three-dimensional patellofemoral kinematics from static imaging-based alignment measures. J Orthop Res 31, 441–447. 10.1002/jor.22246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson JP, 2002. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with patellofemoral pain. Am J Sports Med 30, 447–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow J, Hungerford DS, Woods C, 1976. Patello-femoral joint mechanics and pathology. 2. Chondromalacia patellae. J Bone Joint Surg Br 58, 291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant C, Fick CN, Welsh J, McConnell J, Sheehan FT, 2020. A Word of Caution for Future Studies in Patellofemoral Pain: A Systematic Review With Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med, 363546520926448. 10.1177/0363546520926448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter DJ, Zhang YQ, Niu JB, Felson DT, Kwoh K, Newman A, Kritchevsky S, Harris T, Carbone L, Nevitt M, 2007. Patella malalignment, pain and patellofemoral progression: the Health ABC Study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 15, 1120–1127. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen R, Hystad T, Baerheim A, 2005. Knee function and pain related to psychological variables in patients with long-term patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 35, 594–600. 10.2519/jospt.2005.35.9.594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeter S, Diks MJ, Anderson PG, Wymenga AB, 2007. A modified tibial tubercle osteotomy for patellar maltracking: results at two years. J Bone Joint Surg Br 89, 180–185. 10.1302/0301-620x.89b2.18358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujala UM, Jaakkola LH, Koskinen SK, Taimela S, Hurme M, Nelimarkka O, 1993. Scoring of patellofemoral disorders. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery 9, 159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey M, 1990. Design Sensitivity. SAGE Publications, Inc, California, USA. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre NJ, Hill NA, Fellows RA, Ellis RE, Wilson DR, 2006. Patellofemoral joint kinematics in individuals with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88, 2596–2605. 10.2106/jbjs.e.00674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffulli N, Longo UG, Spiezia F, Denaro V, 2011. Aetiology and prevention of injuries in elite young athletes. Medicine and sport science 56, 187–200. 10.1159/000321078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitiguy P, 2011. Dynamics of mechanical, aerospace, and biomechanical systems. Prodigy Press, Palo Alto, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Moretz JA 3rd, Harlan SD, Goodrich J, Walters R, 1984. Long-term followup of knee injuries in high school football players. Am J Sports Med 12, 298–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslund J, Naslund UB, Odenbring S, Lundeberg T, 2006. Comparison of symptoms and clinical findings in subgroups of individuals with patellofemoral pain. Physiother Theory Pract 22, 105–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhauser EBD, 1957. Radiographic Atlas of Skeletal Development of The Knee. A Standard of Reference. J Bone Joint Surg Am 39, 234–234. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor JE, Bogue C, Spence LD, Last J, 2008. A method to establish the relationship between chronological age and stage of union from radiographic assessment of epiphyseal fusion at the knee: an Irish population study. J Anat 212, 198–209. 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00847.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill DB, Micheli LJ, Warner JP, 1992. Patellofemoral stress. A prospective analysis of exercise treatment in adolescents and adults. Am J Sports Med 20, 151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal S, Besier TF, Draper CE, Fredericson M, Gold GE, Beaupre GS, Delp SL, 2012. Patellar tilt correlates with vastus lateralis: vastus medialis activation ratio in maltracking patellofemoral pain patients. J Orthop Res 30, 927–933. 10.1002/jor.22008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers CM, 2000. Patellar kinematics, part II: the influence of the depth of the trochlear groove in subjects with and without patellofemoral pain. Phys Ther 80, 965–978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DD, McGrath PA, Rafii A, Buckingham B, 1983. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain 17, 45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathleff MS, Rathleff CR, Olesen JL, Rasmussen S, Roos EM, 2016. Is Knee Pain During Adolescence a Self-limiting Condition? Prognosis of Patellofemoral Pain and Other Types of Knee Pain. Am J Sports Med 44, 1165–1171. 10.1177/0363546515622456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathleff MS, Roos EM, Olesen JL, Rasmussen S, 2013. High prevalence of daily and multi-site pain--a cross-sectional population-based study among 3000 Danish adolescents. BMC pediatrics 13, 191. 10.1186/1471-2431-13-191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regalado G, Lintula H, Eskelinen M, Kokki H, Kröger H, Svedström E, Vahlberg T, Väätäinen U, 2013. Dynamic KINE-MRI in patellofemoral instability in adolescents. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 22, 2795–2802. 10.1007/s00167-013-2679-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rillmann P, Oswald A, Holzach P, Ryf C, 2000. Fulkerson’s modified Elmslie-Trillat procedure for objective patellar instability and patellofemoral pain syndrome. Swiss Surg 6, 328–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Yagi T, 1986. Subluxation of the patella: Investigation by computerized tomography. Int Orthop 10, 115–120. 10.1007/bf00267752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seisler AR, Sheehan FT, 2007. Normative Three-Dimensional Patellofemoral and Tibiofemoral Kinematics: A Dynamic, in Vivo Study. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 54, 1333–1341. 10.1109/tbme.2007.890735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan FT, Babushkina A, Alter KE, 2012a. Kinematic determinants of anterior knee pain in cerebral palsy: a case-control study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 93, 1431–1440. 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan FT, Borotikar BS, Behnam AJ, Alter KE, 2012b. Alterations in in vivo knee joint kinematics following a femoral nerve branch block of the vastus medialis: Implications for patellofemoral pain syndrome. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 27, 525–531. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2011.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits-Engelsman B, Klerks M, Kirby A, 2011. Beighton Score: A Valid Measure for Generalized Hypermobility in Children. J Pediatr 158, 119–123.e114. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza RB, Draper CE, Fredericson M, Powers CM, 2010. Femur rotation and patellofemoral joint kinematics: a weight-bearing magnetic resonance imaging analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 40, 277–285. 10.2519/jospt.2010.3215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzue N, Matsuura T, Iwame T, Hamada D, Goto T, Takata Y, Iwase T, Sairyo K, 2014. Prevalence of childhood and adolescent soccer-related overuse injuries. J Med Invest 61, 369–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taskiran E, Dinedurga Z, Yagiz A, Uludag B, Ertekin C, Lok V, 1998. Effect of the vastus medialis obliquus on the patellofemoral joint. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 6, 173–180. 10.1007/s001670050095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson NA, 2009. In Vivo Noninvasive Evaluation of Abnormal Patellar Tracking During Squatting in Patients with Patellofemoral Pain. J Bone Joint Surg Am 91, 558. 10.2106/jbjs.g.00572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witonski D, Goraj B, 1999. Patellar motion analyzed by kinematic and dynamic axial magnetic resonance imaging in patients with anterior knee pain syndrome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 119, 46–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood L, Muller S, Peat G, 2011. The epidemiology of patellofemoral disorders in adulthood: a review of routine general practice morbidity recording. Prim Health Care Res Dev 12, 157–164. 10.1017/s1463423610000460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]