Keywords: cortex, development, Human Connectome Project-Development, sex

Abstract

We assessed changes in gray matter volume of 35 cerebrocortical regions in a large sample of participants in the Human Connectome Project-Development (n = 649, 6–21 yr old, 299 males and 350 females). The same protocol for MRI data acquisition and processing was used for all brains. Volumes of individual areas were adjusted for estimated total intracranial volume and linearly regressed against age. We found changes of volume with age that were distinct among areas and consistent between sexes, as follows: 1) the overall cortical volume decreased significantly with age; 2) the volumes of 30/35 areas also decreased significantly with age; 3) the volumes of the hippocampal cortex (hippocampus, parahippocampal, and entorhinal) and that of pericalcarine cortex did not show significant age-related changes; and 4) the volume of the temporal pole increased significantly with age. The rates of volume reduction with age did not differ significantly between the two sexes, except for areas of the parietal lobe where males showed statistically significantly higher volume reduction with age than females. These results, obtained from a large sample of male and female participants, and acquired and processed in the same way, confirm previous findings, offer new insights into region-specific age-related changes in cortical brain volume, and are discussed in the context of the hypothesis that reduction in cortical volume may be partly due to a background, low-grade chronic neuroinflammation inflicted by common viruses residing latently in the brain, notably viruses of the human herpes family.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY We report mixed effects of age on cortical gray matter volume during development in a large sample of 649 participants studied in an identical manner (6–21 yr old, 299 males, 350 females). Volumes of 30/35 cortical areas decreased with age, temporal pole increased, and pericalcarine and hippocampal cortex (hippocampus, parahippocampal, and entorhinal) did not change. These findings were very similar in both sexes and provide a solid base for assessing region-specific cortical changes during development.

INTRODUCTION

Changes of cortical volume during development have been extensively studied, as discussed in detail in two recent reviews (1, 2). Sample sizes in various studies are moderate; and hardware (MRI system), data acquisition protocols, and data processing pipelines typically differ across studies. Although some basic findings have been consistent (e.g., that cortical volume decreases after the age of 5 yr), comprehensive data from methodologically homogeneous (hardware and software) studies with large sample sizes are lacking. Similarly lacking are data from large samples of male and female brains. Such data have been recently provided by the Human Connectome Project-Development (HCP-D) (3). These data were acquired by the same MRI hardware and the same data acquisition and processing protocol from a large number of participants (n = 652) of ages 5–21 yr, comprising similarly large numbers of male (n = 301) and female (n = 351) participants. To our knowledge, this is the first data set of this magnitude, homogeneity, and sex representation to date. Here, we report on the results of analysis of changes with age in gray matter volumes of 35 cortical areas, and their comparison between males and females.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

We analyzed data from 652 healthy participants (301 males and 351 females, age range 6–21 yr) of the HCP-D (3) publicly available from www.humanconnectome.org. Specifically, healthy participants were selected to represent “typical development” with diversity across ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic status. Exclusion criteria included premature birth, and lifetime history of serious medical or endocrine conditions, or their treatment. All participants aged 18 and above provided written informed consent. For children under age 18, a parent or a legal guardian provided informed, written permission for their child to participate in the study. The Research and Development Committee of the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center approved the analysis of these data.

MRI Data Acquisition

MRI data were acquired using a Siemens (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) 3 T Prisma whole body scanner with 80 mT/m gradient coil (4). The 32-channel head coil of this scanner enables high acceleration factors via multi-slice acquisitions of MR images (MRI) (4). Structural images were T1-weighted (T1w) multi-echo MPRAGE with a duration of 502 s and T2-weighted (T2w) SPACE with a duration of 395 s. Both structural scans used a sagittal field of view of 256 × 240 × 166 mm and 0.8 mm isotropic voxels. T1w-scan: TE = 1.8/3.6/5.4/7.2 ms multi-echo, TR/TI = 2,500/1,000, flip angle = 8°; T2w-scan: TR/TE = 3,200/564 ms. The T1w and T2w images were processed using three HCP structural pipelines using FreeSurfer (v.6.0) to yield high-quality volume data (5). We extracted the volumes of 35 cortical areas (6; Table 1) from two hemispheres and averaged them for analysis.

Table 1.

Ranked changes of qyr for the 35 cortical areas studied and the whole cortical gray matter

| Rank | Area | Lobe | qyr (%) Linear | P Value Linear | r2(q) Linear Fit | r2(q′) Log Fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Superior parietal | Parietal | −1.706 | <0.001 | 0.446 | 0.461 |

| 2 | Precuneus | Parietal | −1.532 | <0.001 | 0.458 | 0.474 |

| 3 | Inferior parietal | Parietal | −1.485 | <0.001 | 0.337 | 0.336 |

| 4 | Supramarginal | Parietal | −1.474 | <0.001 | 0.306 | 0.309 |

| 5 | Frontal pole | Frontal | −1.412 | <0.001 | 0.225 | 0.231 |

| 6 | Rostral middle frontal | Frontal | −1.389 | <0.001 | 0.334 | 0.332 |

| 7 | Postcentral | Parietal | −1.376 | <0.001 | 0.324 | 0.340 |

| 8 | Banks of superior temporal sulcus | Temporal | −1.297 | <0.001 | 0.206 | 0.211 |

| 9 | Caudal middle frontal | Frontal | −1.269 | <0.001 | 0.189 | 0.187 |

| 10 | Inferior frontal pars orbitalis | Frontal | −1.238 | <0.001 | 0.266 | 0.266 |

| 11 | Paracentral | Frontal | −1.230 | <0.001 | 0.277 | 0.289 |

| 12 | Superior frontal | Frontal | −1.196 | <0.001 | 0.344 | 0.337 |

| 13 | Inferior frontal pars triangularis | Frontal | −1.184 | <0.001 | 0.180 | 0.185 |

| 14 | Middle temporal | Temporal | −1.155 | <0.001 | 0.281 | 0.274 |

| 15 | Isthmus cingulate | Cingulate | −1.154 | <0.001 | 0.188 | 0.197 |

| 16 | Posterior cingulate | Cingulate | −1.115 | <0.001 | 0.188 | 0.193 |

| 17 | Lateral orbitofrontal | Frontal | −1.109 | <0.001 | 0.316 | 0.323 |

| 18 | Medial orbitofrontal | Frontal | −1.088 | <0.001 | 0.174 | 0.182 |

| 19 | Inferior frontal pars opercularis | Frontal | −1.057 | <0.001 | 0.127 | 0.130 |

| 20 | Transverse temporal | Temporal | −1.043 | <0.001 | 0.114 | 0.123 |

| 21 | Superior temporal | Temporal | −1.019 | <0.001 | 0.250 | 0.254 |

| 22 | Lateral occipital | Occipital | −0.974 | <0.001 | 0.160 | 0.172 |

| 23 | Inferior temporal | Temporal | −0.870 | <0.001 | 0.146 | 0.134 |

| 24 | Cuneus | Occipital | −0.826 | <0.001 | 0.068 | 0.078 |

| 25 | Precentral | Frontal | −0.794 | <0.001 | 0.177 | 0.181 |

| 26 | Caudal anterior cingulate | Cingulate | −0.781 | <0.001 | 0.038 | 0.036 |

| 27 | Fusiform | Temporal | −0.644 | <0.001 | 0.103 | 0.109 |

| 28 | Lingual | Occipital | −0.641 | <0.001 | 0.047 | 0.052 |

| 29 | Rostral anterior cingulate | Cingulate | −0.607 | <0.001 | 0.032 | 0.033 |

| 30 | Insula | Parietal | −0.257 | <0.001 | 0.021 | 0.022 |

| 31 | Parahippocampal | Temporal | −0.128 | NS | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| 32 | Hippocampus | Temporal | −0.017 | NS | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 33 | Pericalcarine | Occipital | 0.164 | NS | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| 34 | Entorhinal | Temporal | 0.254 | NS | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| 35 | Temporal pole | Temporal | 0.324 | 0.005 | 0.012 | 0.010 |

| All cortical gray matter | −1.129 | <0.001 | 0.562 | 0.571 |

Statistical Analyses

Standard statistical methods were used to analyze the data, including linear regression, t test, testing of proportions, etc.

Volumes

To correct for variation in estimated total intracranial volume (eTIV), we computed the fraction of the volume of individual regions over eTIV and expressed it as a percentage:

| (1) |

The dependence of q on age was determined using a linear regression where q was the dependent variable and age in years (yr) was the independent variable:

| (2) |

and

| (3) |

The correlation coefficient r of the regression aforementioned (Eq. 2) was Fisher z-transformed to normalize its distribution:

| (4) |

Regression slopes were compared using Paternoster’s test (7):

| (5) |

where z is the normal deviate, b1 and b2 are the two regression slopes to be compared, and SEb1 and SEb2 are the standard errors of b1 and b2, respectively.

Logarithmic Regression

In preliminary analyses, we observed that for some areas a logarithmic fit was better than a linear fit. Therefore, we also carried out a logarithmic regression of the following form and retained its coefficient of determination (r2):

| (6) |

MRI data processing was performed using MATLAB (v.R2016) and statistical analyses using the IBM-SPSS statistical package (v.27). All P values reported are two-sided.

RESULTS

Of the total of 652 participants in the HCP-D data set, there were only two participants younger than 6 yr old, both males, and were excluded from further analyses given the small sample size for this age group and since a primary goal of this study was to compare data between sexes. In addition, there was an extreme positive q outlier value in the female group, which was excluded. Therefore, analyses were conducted on data from 299 male and 350 female participants for a total of n = 649 participants. The means (±SE) age for males was 14.69 ± 0.224 yr (range: 6.42–21.92 yr), and for females 14.26 ± 0.222 yr (range: 6.08–21.92 yr). These means did not differ significantly (t[648] = 1.31, P = 0.190, independent-samples t test).

Analysis of q

Figure 1A plots q against age for the cortical gray matter for the whole group, and Fig. 1, B and C plot the same data for males and females, respectively. It can be seen in these three plots that q decreased with age in a linear fashion. Regression slopes were very similar for the three groups, were highly statistically significant, and did not differ significantly between groups (P > 0.2 for all three comparisons, Paternoster’s test). The regression equations were:

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

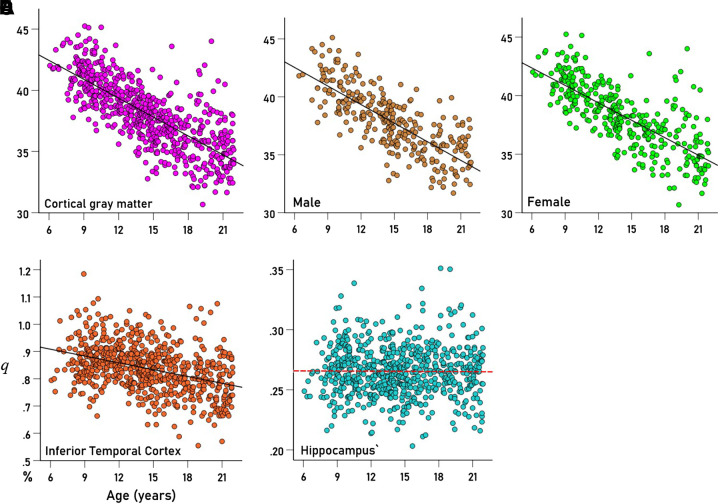

Figure 1.

Values of q (Eq. 2) of brain regions from individual participants are plotted against the age of the participant. Lines are fitted linear regression fits. A: cerebrocortical gray matter (all brains, n = 649). B: same region for males (n = 299). C: same region for females (n = 350). D: inferior temporal cortex, all brains (n = 649). E: hippocampus, all brains (n = 649). Relevant statistics for the plots are given in Table 1.

Figure 1, D and E illustrate results from two areas: inferior temporal cortex (Fig. 1D) and hippocampus (Fig. 1E). There was a significant decrease of q with age for inferior temporal cortex (r = −0.382, P < 0.001, n = 649) but not for the hippocampus (r = −0.009, P = 0.825, n = 649).

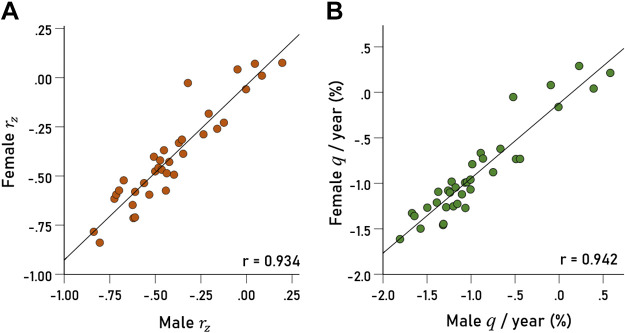

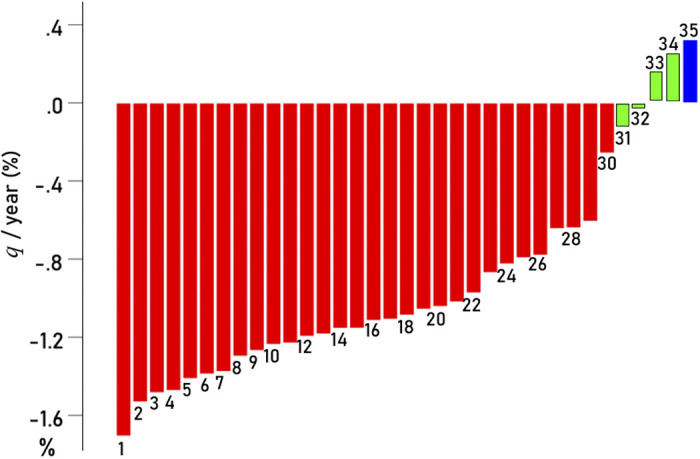

The percent changes of q per year are given in Table 1 and are plotted ranked in Fig. 2: 1) 30/35 areas (85.7%) showed a statistically significant decrease of qyr with age (red in Fig. 2; P < 0.001 for all areas, linear regression), a highly statistically significant proportion (Z = 4.22, P < 0.001, Wilson score for one-sample proportion); 2) one area (2.9%, blue: temporal pole) showed a statistically significant increase of qyr (P = 0.005); and 3) four areas (11.4%, green: hippocampus, parahippocampal, entorhinal, and pericalcarine) did not show a statistically significant change with age (P > 0.1; Table 1). The highest percent decrease of qyr was observed in the superior parietal cortex (−1.706%), and the lowest in insula (−0.257%), a 6.6× differential.

Figure 2.

Change of q (Eq. 2) per year for the 35 areas studied is plotted ranked. Red, statistically significant decreases; green, changes not statistically significant; blue, statistically significant increase. The numbers correspond to the ranks in Table 1 (first column).

Finally, Table 1 also shows the goodness of fit (coefficient of determination, r2) for the linear (q) and logarithmic (q′) regressions (Eqs. 2 and 6, respectively). It can be seen that the two fits are very close, although, more frequently better for the logarithmic than the linear fit. Given the very highly significant linear fits, we used those for detailed analyses, since they are easier to interpret. More specifically, the slope in the linear regression denotes a rate of change in q per year, whereas the slope in the logarithmic regression denotes a rate of change in q per the logarithm of the year, ln(yr), which means that the actual change of q per year will be progressively less at older ages.

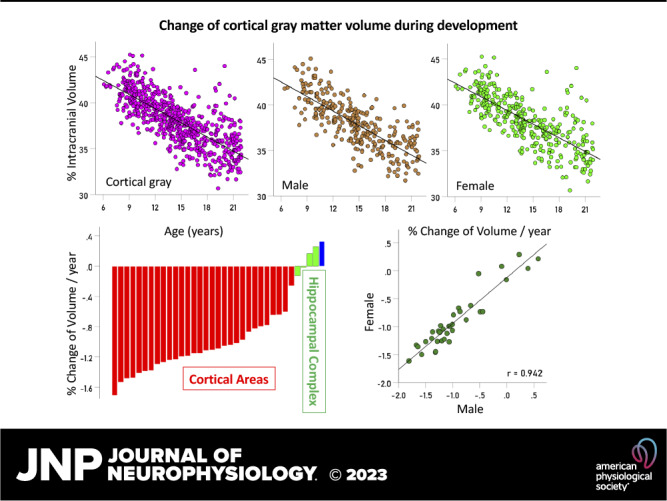

Effect of Sex

The results for males and females were highly and positively correlated. Specifically, the correlation between rz of males and females was 0.934 (Fig. 3A; P < 0.001, n = 35 areas), and the correlation between qyr was 0.942 (Fig. 3B; P < 0.001, n = 35 areas). There was no significant male-female difference (paired samples t test) with respect to 1) the regression fit differences:

| (10) |

and 2) similarly for the percent change of q per year:

| (11) |

Figure 3.

A: Fisher z-transformed correlations rz of 35 q vs. years linear regression fits (one for each area) in females are plotted against the corresponding rz values of males. For each regression analysis, n = 350 and 299 for females and males, respectively. B: changes of q/yr (%) in 35 areas in females are plotted against the corresponding changes in males. See text for details.

Cortical Lobes

With respect to lobes, the proportions of statistically significant decreases with age in the five lobes were 11/11 (100%) in the frontal lobe (Z = 3.32, P < 0.001, Wilson score test), 6/6 (100%) in the parietal lobe (Z = 2.45, P = 0.014), 6/10 (60%) in the temporal lobe (Z = 0.632, P = 0.527), 3/4 (75%) in the occipital lobe (Z = 1.00, P = 0.317), and 4/4 (100%) in the cingulate lobe (Z = 2.00, P = 0.046). More specifically, of four areas without significant changes, three were located in the temporal lobe (hippocampus, parahippocampal, entorhinal cortex) and 1 in the occipital lobe (pericalcarine cortex); the only area with a significant volume increase (temporal pole) was located in the temporal cortex. Overall, the highest rate of qyr was observed in the parietal cortex (−1.305 ± 0.214%, means ± SE, t[5] = 6.09, P = 0.00017, one-sample t test against the null hypothesis that mean = 0), followed by the frontal cortex (−1.179 ± 0.051%, t[10] = 22.97, P = 6.51 × 10−10), the cingulate cortex (−0.914 ± 0.132%, t[3] = 6.91, P = 0.0062), the occipital cortex (−0.569 ± 0.254%, t[3] = 2.24, P = 0.110), and the temporal cortex (−0.559 ± 0.193%, t[9] = 2.89, P = 0.018). The coefficient of variation (CV = standard deviation/mean) was smallest in the frontal lobe (CV = 0.14), highest in the temporal lobe (CV = 1.09), and the remaining lobes were occipital CV = 0.89, parietal CV = 0.40, and cingulate CV = 0.29.

Finally, with respect to sex groups, a statistically significant higher rate of decrease in volume in males (as compared to females) was found for the parietal lobe only (paired-samples t test, t[5] = 4.846, P = 0.005):

| (12) |

DISCUSSION

The decrease we found in the overall cortical gray volume is in accord with previous findings (1, 2, 8) and has been attributed to cortical thinning (2). Interestingly, the rate of volume decrease was practically the same across sexes, in contrast to older ages, where the rate of volume decrease was found to be greater in men in a similarly large sample from the HCP-Aging (9). A significant volume decrease was found in 30/35 areas, with rates varying by a 6.6-fold range (Table 1). In accordance with previous findings (2), parietal and frontal cortices showed the highest volume reduction rates, with males having a higher reduction rate in the parietal cortex. Interestingly, areas in the frontal cortex showed the most similar and consistent reduction rates, with the smallest coefficient of variation (CV = 0.14), in contrast to the highest CV = 1.09 observed in the temporal cortex, a 7.7× differential. The high temporal lobe CV seems to be due to the fact that the three hippocampal areas (hippocampus, parahippocampal, and entorhinal) did not show a significant volume decrease, whereas the temporal pole showed a volume increase. A plausible explanation for the hippocampal lack of volume decrease would be that it is due to ongoing neurogenesis (10, 11). Finally, it is not clear what might underlie the increase in temporal pole volume.

What Causes Cortical Volume Reduction?

The underlying causes of age-related decreases in cortical volumes are unclear. Synaptic pruning during early development (12) has been implicated but key questions remain unanswered. For example, why does cortical volume increase after birth, reaching a peak at 2 yr? One would expect a decrease, especially early postnatally. Then, why some areas do not show a volume decrease and some show an increase? Is activity-dependent synaptic pruning inoperative in the temporal pole, where a clear increase in volume is observed? It seems that several factors are involved, including activity-dependent changes, postnatal neurogenesis, and adverse neuroinflammatory processes, as proposed here. In older age, low-grade, chronic neuroinflammatory processes have been postulated as partly responsible for aging-associated changes in the brain (13–15), with a variation in the susceptibility/vulnerability of different areas to possibly account for the variable reduction rates among areas. Support for this hypothesis has been provided by the finding that brains of people carrying the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) allele DRB1*13:02 do not show age-related atrophy (16). Given that HLA alleles are instrumental in eliminating viruses, it was hypothesized that this protective effect could be due to the elimination of harmful viruses [e.g., human herpes virus (HHV) strains], thus reducing neuroinflammation. This hypothesis, if extended to the present case of development, would suggest that, among other factors, latent neuroinflammation would contribute to the observed cortical volume reduction. For example, it is well known that infection with the highly neurotropic HHV-6A and 6B is very common in early childhood (17), with more than 95% of children over 2 yr being seropositive for either HHV-6A or HHV-6B or both (18). HHV-6A and 6B, among other HHV strains, are highly neurotropic and have been detected in the brains of healthy, immunocompetent individuals as well as in the brains of patients with various neurological diseases (19). Interestingly, the integration of HHV-6 into germline cells allows the viral genome to be passed down from one generation to the next [“inherited chromosomally integrated HHV-6 (iciHHV-6)] (20). Chromosomally integrated HHV-6 (iciHHV-6) has been reported both in vivo and in vitro, and integration into gametes can result in the inheritance of HHV-6 (21). This condition occurs in ∼1% of the human population worldwide and is considered the major mode of congenital HHV-6 transmission (22). The inherited viral genome is passed on to subsequent generations in a Mendelian manner, and all iciHHV-6-positive individuals harbor one copy of the viral genome in every nucleated cell. As a result, these individuals exhibit a persistent high viral load in whole blood; and hair follicles, leukocytes, and other clinical samples are also positive (22). Although the long-term clinical implications of this condition are unclear, it is of concern that HHV6 can be inherited. Following primary infection, herpesviruses persist for life in their hosts in a latent stage (23) and, depending on the HHV strain, they can be reactivated by various triggers, including local injury to tissues innervated by latently infected neurons, systemic physical or emotional stress, fever, infection by a different or the same HHV strain, immunosuppression, etc. (24, 25). We speculate that, conceivably, HHVs could partly underlie pathological processes contributing to cortical volume reduction by promoting low-grade, chronic neuroinflammation under the aforementioned conditions.

Limitations

This study used a cross-sectional sample, whereas a longitudinal sample would have been the better choice.

GRANTS

Funding was provided by the University of Minnesota (Kunin Chair in Women’s Healthy Brain Aging and McKnight Presidential Chair in Cognitive Neuroscience), and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Research reported here was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health Award U01MH109589 and by the McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience (Washington University, St. Louis).

DISCLAIMERS

The sponsors had no role in the study design, analysis, interpretation, or writing this paper. The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. The HCP-Development 2.0 Release data used came from DOI: 10.15154/1520708. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P.C. and A.P.G. conceived and designed research; P.C. and A.P.G. analyzed data; P.C. and A.P.G. interpreted results of experiments; A.P.G. prepared figures; P.C. and A.P.G. drafted manuscript; P.C. and A.P.G. edited and revised manuscript; P.C. and A.P.G. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bethlehem RAI, Seidlitz J, White SR, Vogel JW, Anderson KM, Adamson C , et al. Brain charts for the human lifespan. Nature 604: 525–533, 2022. [Erratum in Nature 610: E6, 2022]. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04554-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tamnes CK, Herting MM, Goddings A-L, Meuwese R, Blakemore S-J, Dahl RE, Güroğlu B, Raznahan A, Sowell ER, Crone EA, Mills KL. Development of the cerebral cortex across adolescence: a multisample study of inter-related longitudinal changes in cortical volume, surface area, and thickness. J Neurosci 37: 3402–3412, 2017. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3302-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Somerville LH, Bookheimer SY, Buckner RL, Burgess GC, Curtiss SW, Dapretto M, Elam JS, Gaffrey MS, Harms MP, Hodge C, Kandala S, Kastman EK, Nichols TE, Schlaggar BL, Smith SM, Thomas KM, Yacoub E, Van Essen DC, Barch DM. The Lifespan Human Connectome Project in Development: a large-scale study of brain connectivity development in 5–21 year olds. NeuroImage 183: 456–468, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.08.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harms MP, Somerville LH, Ances BM, Andersson J, Barch DM , et al. Extending the Human Connectome Project across ages: imaging protocols for the Lifespan Development and Aging projects. NeuroImage 183: 972–984, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.09.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Glasser MF, Sotiropoulos SN, Wilson JA, Coalson TS, Fischl B, Andersson JL, Xu J, Jbabdi S, Webster M, Polimeni JR, Van Essen DC, Jenkinson M; WU-Minn HCP Consortium. The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the Human Connectome Project. NeuroImage 80: 105–124, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, Buckner RL, Dale AM, Maguire RP, Hyman BT, Albert MS, Killiany RJ. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyal based regions of interest. NeuroImage 31: 968–980, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Paternoster R, Brame R, Mazerolle P, Piquero A. Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology 36: 859–866, 1998. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1998.tb01268.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lenroot RK, Gogtay N, Greenstein DK, Wells EM, Wallace GL, Clasen LS, Blumenthal JD, Lerch J, Zijdenbos AP, Evans AC, Thompson PM, Giedd JN. Sexual dimorphism of brain developmental trajectories during childhood and adolescence. NeuroImage 36: 1065–1073, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Christova P, Georgopoulos AP. Differential reduction of gray matter volume with age in 35 cortical areas in men (more) and women (less). J Neurophysiol 129: 894–899, 2023. doi: 10.1152/jn.00066.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Toda T, Parylak SL, Linker SB, Gage FH. The role of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in brain health and disease. Mol Psychiatry 24: 67–87, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0036-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ohira K. Regulation of adult neurogenesis in the cerebral cortex. J Neurol Neuromed 3: 59–64, 2018. doi: 10.29245/2572.942X/2018/4.1192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sakai J. Core Concept: how synaptic pruning shapes neural wiring during development and, possibly, in disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117: 16096–16099, 2020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010281117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DiSabato DJ, Quan N, Godbout JP. Neuroinflammation: the devil is in the details. J Neurochem 139, Suppl 2: 136–153, 2016. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Perkins AE, Varlinskaya EI, Deak T. From adolescence to late aging: A comprehensive review of social behavior, alcohol, and neuroinflammation across the lifespan. Int Rev Neurobiol 148: 231–303, 2019. doi: 10.1016/bs.irn.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ownby RL. Neuroinflammation and cognitive aging. Curr Psychiatry Rep 12: 39–45, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. James LM, Christova P, Lewis SM, Engdahl BE, Georgopoulos A, Georgopoulos AP. Protective effect of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) allele DRB1*13:02 on age-related brain gray matter volume reduction in healthy women. EBioMedicine 29: 31–37, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Campadelli-Fiume G, Mirandola P, Menotti L. Human herpesvirus 6: an emerging pathogen. Emerg Infect Dis 5: 353–366, 1999. doi: 10.3201/eid0503.990306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Braun DK, Dominguez G, Pellett PE. Human herpesvirus 6. Clin Microbiol Rev 10: 521–567, 1997. doi: 10.1128/CMR.10.3.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Santpere G, Telford M, Andrés-Benito P, Navarro A, Ferrer I. The presence of human herpesvirus 6 in the brain in health and disease. Biomolecules 10: 1520, 2020. doi: 10.3390/biom10111520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pantry SN, Medveczky PG. Latency, integration, and reactivation of human herpesvirus-6. Viruses 9: 194, 2017. doi: 10.3390/v9070194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tanaka-Taya K, Sashihara J, Kurahashi H, Amo K, Miyagawa H, Kondo K, Okada S, Yamanishi K. Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) is transmitted from parent to child in an integrated form and characterization of cases with chromosomally integrated HHV-6 DNA. J Med Virol 73: 465–473, 2004. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hall CB, Caserta MT, Schnabel K, Shelley LM, Marino AS, Carnahan JA, Yoo C, Lofthus GK, McDermott MP. Chromosomal integration of human herpesvirus 6 is the major mode of congenital human herpesvirus 6 infection. Pediatrics 122: 513–520, 2008. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Adler B, Sattler C, Adler H. Herpesviruses and their host cells: a successful liaison. Trends Microbiol 25: 229–241, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stoeger T, Adler H. “Novel” triggers of herpesvirus reactivation and their potential health relevance. Front Microbiol 9: 3207, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roizman B, Whitley RJ. An inquiry into the molecular basis of HSV latency and reactivation. Annu Rev Microbiol 67: 355–374, 2013. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]