Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Abortion is can led to certain psychological problems that may decreased self-esteem, and concerns about future fertility. Abortions have multiple psychological consequences such as grief, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress. The purpose of this study is to examine the effect of cognitive behavioral counseling intervention on women in post-abortion period.

MATERIAL AND METHODS:

This research was a randomized, controlled trial study that was conducted on 168 women during the post-abortion period at the Khalill Azad Center of Larestan (Iran), where the women were selected randomly from February 2019 to January 2020. Data were collected using post-abortion grief questionnaire. All women in the post-abortion period answered the perinatal grief scale questions at the beginning of the intervention, immediately after the intervention and three months after the end of the intervention. Data were analyzed through descriptive statistics and repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with time and group were used to evaluate the effect of intervention.

RESULTS:

By using repeated measures ANOVA, the comparison of the mean score of grief in the two groups indicated that the scores decreased over time and it was lower in the intervention group. The mean score of grief between the intervention and control groups at the end of the intervention was 67.59 ± 13.21 and 75.42 ± 12.7, respectively (P < 0.001). Mean post-abortion grief score in the intervention and control groups three months after the intervention were 59.41 ± 13.71 and 69.32 ± 12.45, respectively (P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION:

According to results of this study, it can be concluded that the use of cognitive behavioral counselling can reduce post-abortion grief intensity or prevent the occurrence of complicated grief. Therefore, this method can be used as a preventive or therapeutic approach to control post-abortion grief and other psychological disorders.

Keywords: Cognitive behavioral therapy, grief, randomized controlled trials

Introduction

Abortion is one of the most common health concerns that can lead to certain psychological problems such as smoking, drug abuse, eating disorders, depression, attempted suicide, guilt, regret, nightmares, decreased self-esteem, and concerns about future fertility.[1] Abortion has multiple psychological consequences such as grief, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress. The prevalence of post-abortion grief, depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress are 31%, 6.7%, 3.4% and 23.5%, respectively.[2]

Grief is one of the psychological responses which occurs in approximately 31% of pregnancies that lead to a miscarriage.[3] Although women have not developed a relationship with their baby, the grief after pregnancy loss does not differ significantly in intensity from loss of other first-degree relatives, and grief symptoms usually decrease over the first 12 months.[4] Grief is unique compared to other losses, and sudden and unexpected death or lack of memories may lead to this situation.[5]

Post-abortion grief is unique compared to other losses, and sudden and unexpected death or lack of memories may lead to this situation.[4] Grief is a normal response to miscarriage that could progress to complicated grief.[6] Complicated grief is a syndrome that occurs in about 10% of people, and it is caused by a failure of transition from acute to adaptive grief.[5] On the other hand, women with positive history of miscarriage may be concerned about their next pregnancy.[7]

Psychological counselling can increase coping with adversity and could decrease feelings of guilt, shame, or self-blame.[8] Review of articles showed that psychotherapy-based interventions are effective in post-abortion grief treatments.[9] Various psychological interventions have been used in post-abortion grief. In one of these interventions, the treatment group received a 1-hour bereavement intervention based on Guidelines for Medical Professionals Providing Care to the Family Experiencing Perinatal Loss two weeks of the loss of the pregnancy, and a 15-minute telephone call one week later was used to reinforce the information from the bereavement intervention. The effect of the intervention was to lessen the despair of the women in the intervention group.[10] A structured conversation with a midwife for 60 minutes focusing on the woman's experience of miscarriage was held and reduction of women's grief at one and four months post miscarriage were reported, but it wasn’t statistically significant.[11] One session of psychological counselling with a psychologist for 50 minutes, five weeks after the miscarriage was another intervention and post-miscarriage grief measured at 4-, 7- and 16-weeks after miscarriage. The grief score at four and seven weeks after the intervention did not show a statistically significant difference.[12] Swanson evaluated the effect of three intervention methods on grief and depression in men and women after abortion. Results showed that nursing counselling three months after abortion had a better effect on grief and depression.[13] To summarize, all the interventions reported took place from 1 to 18 weeks after miscarriage and outcomes were different.

Several studies have demonstrated cognitive behavioral counseling as the best method of treatment of some problems such as anger control, anxiety and depression.[14–16] Although the advantage of this method over other methods has not yet been proven, many researchers believe that this method can be used as the first method of treatment.[17]

Despite a high prevalence of post-abortion grief and its complications among women, the researchers did not find any studies that evaluated cognitive behavioral counseling on post-abortion grief prevention. This paper addresses gaps identified in the literature; therefore the primary research question driving this study was, “What is the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral counselling on post abortion grief?” The secondary research question asked was, “Do the cognitive behavioral counselling have a positive impact on women in the long time?”

Material and Methods

Study design and setting

This two-group, parallel, non-blinded, randomized, controlled trial was performed on 168 women in the post-abortion period at the Khalill Azad Center of Larestan in Fars province, Iran, where the women were selected randomly from February 2019 to January 2020.

Study participants and sampling

A minimum of 168 women were randomly allocated to one of the two experimental or control groups (no intervention), in a 1:1 ratio. Inclusion criteria were women with positive history of spontaneous abortion or any other abortion, 2–12 months after miscarriage, aged over 18 years and the ability to speak and understand Persian language. Negative history of present pregnancy, negative history of psychotherapy at the time of treatment (duration of counselling), history of depression, substance abuse, mental disorders, taking psychotropic medications, suicidal tendencies, complicated grief or chronic physical illness. Exclusion criteria was declined participation or reluctance to continue research.

According to mean comparison in two communities in similar studies[18,19] and standard deviation, with 80% power and the type I error of 0.05, the sample size in each group was considered 84. Current research had two control and counselling groups and four block sampling. In this method, six possible situations 1 AABB, 2 ABBA, 3 ABAB, 4 BBAA, 5 BAAB, 6 BABA existed. By a table of random numbers and four block sampling, 168 concealed envelopes were prepared by a methodologist and numbered from 1 to 168 and each (A or B) were written inside these envelopes. Participants received one of these envelopes according to their enrollment.

Data collection tool and technique

The study measures include a sociodemographic questionnaire including questions about age, marital status, job, level of education, history of other disease, place, age husband's age, his job, his medical disease, time of abortion, method and place of abortion (home or hospital) and standardized Persian version of post-abortion grief scale which was validated by Mirzabigi.[20] The post-abortion grief questionnaire included 33 questions used for measuring the seriousness of symptoms of an individual aged 18 years and over. It consisted of three subscales: active grief, difficulty in coping, and despair.[21] The internal reliability coefficient, tested using Cornbrash's α, and external validity, tested by test-retest, and with a correlation of <0.9, its validity and reliability were confirmed.

In order to collect data, Imam Reza, Amir Al-Momenin and Omidvar hospitals were used and consultative intervention was performed in Khalil Azad Clinic (lar, Fars's province, Iran). After obtaining permission from the ethics and registration committee in the clinical trial intervention system, the research assistant referred the mentioned hospitals and talked to the women who were eligible to participate in the study.

At first, participants completed the post-abortion grief questionnaire, after which they received one of the prepared, concealed envelopes according to their enrollment; this determined which group they belonged to. The intervention was performed by a PhD student in reproductive health (researcher) under a psychologist's supervision. Twenty-four hours before counselling, the researcher called the participants and the next day's meeting was reminded.

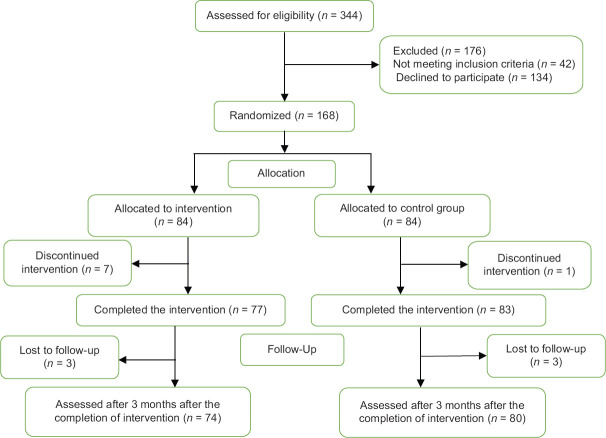

The cognitive-behavioral counselling group (group A) received six (30–40 minutes) counselling sessions which were held weekly. The sessions were conducted as group discussion and were including of the cognitive assessment, and agreement on the aim of therapy, providing information about grief, its process and components, normalizing its emotional and behavioral consequences of grief process (”its normal to cry when one experiences such a loss”), identifying dysfunctional irrational beliefs and their emotional behavioral and physical consequences, helping the bereaved find a way to organize their life without the deceased; on the other hand, the control group (group B) received routine care such as checking of vital signs and bleeding. After six counseling sessions, the participants completed the post-abortion questionnaire immediately and once more three months after the intervention. Some women were excluded due to travel or unwillingness to cooperate [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Consort CONSORT flowchart

Statistical methods

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 18. Descriptive statistics including central indicators, and frequency distribution were used to describe the data. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to determine if the data had normal distribution. The between-group similarity of data was evaluated using t-test and Chi-squared or Fisher's exact test (P > 0.05).

Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with time (before intervention, immediately after intervention, 3 months after intervention) and group (control and intervention) were used to evaluate the effect of intervention. To determine repeated measures ANOVA, Mauchly's sphericity test was used.

Ethical consideration

The protocol of this study was approved by the ethics and research committee of Shahroud University of Medical Sciences (N0.IR.SHMU.REC.1396.43 Date 24/5/2017). The trial is registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials, number IRCT20180407039223N1.

Participants were informed of the purpose of the study before entering the study. Participants were assured that their information was completely confidential and that they could discontinue their participation in the study whenever they wished, if they were unwilling to cooperate.

Results

One hundred sixty-eight women, who were randomly assigned to the intervention and control groups, participated in the study. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of age, marital age, education status, spouse age, place, gestational age at abortion time and time after abortion [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic and obstetrical characteristics of the groups

| Variable | Group | Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Intervention | Control | ||

| Age* | 28.75±4.76 | 28.53±5.5 | P=0.778 |

| Years of formal education* | |||

| 7-12 years | 44 (52.4) | 45 (53.6) | P=0.115 |

| 13-16 years | 40 (47.6) | 39 (46.4) | |

| Place** | |||

| Urban area | 82 (97.6) | 83 (98.8) | P=0.56 |

| Rural area | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Occupational status* | |||

| Employed | 18 (21.4) | 15 (17.9) | P=0.56 |

| House wife | 66 (78.6) | 69 (82.1) | |

| Abortion* | |||

| 1 | 68 (81) | 67 (79.1) | P=0.673 |

| 2 | 12 (14.2) | 15 (17.8) | |

| >2 | 4 (4.8) | 2 (2.4) | |

| Living children* | |||

| 0 | 35 (41.7) | 26 (31) | P=0.472 |

| 1 | 30 (35.7) | 36 (42.8) | |

| 2 | 17 (20.2) | 17 (20.2) | |

| >2 | 2 (2.4) | 5 (6) | |

| Place of abortion* | |||

| Home | 49 (58.3) | 46 (54.8) | P=0.378 |

| Hospital | 35 (41.7) | 38 (45.2) | |

| Type of abortion* | |||

| Spontaneous | 63 (75) | 61 (72.6) | P=0.43 |

| Induced | 21 (25) | 23 (27.4) | |

| History of disease* | |||

| Yes | 5 (6) | 4 (4.8) | P=0.52 |

| No | 79 (94) | 80 (95.2) | |

| Gestational age* | |||

| >12 weeks | 60 (71.4) | 55 (65.5) | P=0.356 |

| 12-20 weeks | 24 (21.6) | 29 (34.5) | |

Chi-squared test*, Fisher’s exact test**

In the current study, the post-abortion grief score in the two groups was evaluated in the pre-intervention, immediately after the intervention, and three months after the end of the intervention. Mauchly's sphericity test was statically significant (P < 0.001). Therefore, Greenhouse–Geiser was used for interpretation of data. By using repeated measures ANOVA, the comparison of the mean score of grief in the two groups indicated that the scores decrease over time. Result of the t-test showed that there was a significant difference between the two groups at the end of intervention (P < 0.001). The result of the t-test showed that at three months after intervention, there was a significant difference between the two groups (P < 0.001) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of the mean post-abortion grief score before, immediately after the last session, and three months after the study in the two groups

| Variable | Before intervention (Mean±SD) | At the end of intervention (Mean±SD) | 3 months after intervention (Mean±SD) | Time effect | Group effect | Time × group effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group | 76.79±13.05 | 67.59±13.21 | 59.41±13.71 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 |

| Control group | 78.41±13.68 | 75.42±12.7 | 69.32±12.45 |

Discussion

Our finding is in line with the results of studies that reported the positive effect of cognitive behavior therapy on postnatal grief scores. The intervention group's grief score significantly decreased after six sessions of the cognitive behavioral counselling. Similarly, Navidian indicated that four sessions of CBT in over two weeks had a positive effect on postnatal grief. They evaluated couples one month after the intervention. In his study, spousal support was evaluated, which was one of the important factors in decreasing postnatal grief.[22] Another clinical trial showed that cognitive-behavioral therapy reduced psychological distress (depression and anxiety) in women with recurrent miscarriages.[23]

Kersting et al.[18,19] showed that three sessions of CBT over three weeks was effective in reducing post-abortion grief problems and increasing the quality of life among women. Almost all of the women were over 12 weeks. Women expressed their feelings and emotions in three sessions via email. Using this method is suitable for people who are afraid to face the therapist due to fear of stigma, or due to distance and time constraints are not able to be present at the designated place. Swanson et al.[13] showed that three counselling sessions had the broadest positive impact on couple resolution of grief and depression. In their study, individuals were admitted to the study three months after the abortion. Intervention was based on Swanson caring theory, and meaning of miscarriage model was offered 1, 5 and 11 weeks after enrollment. Also, Golmakani et al.[24] indicated that post-abortion counselling was effective in reducing grief symptoms. They had three counselling sessions based on Swanson theory: in the beginning, 90 minutes promptly after the abortion, the secondary was 90 minutes a week later, and the third session included direct counseling.

However, in contrast to their studies that show the positive effects of the counselling intervention, there are studies reporting that this intervention had no significant effect on patients. Adolfsson et al. reported one session counselling according to Swanson approach 21–28 days after abortion had no significant effect on grief level.[11] Perhaps the reason for the heterogeneity of two studies is the onset of the consultation or sessions of counselling (one session vs six sessions). In another randomized, controlled trial, it was shown that one session of Swanston approach counselling was not significant for reducing grief score.[25] In another randomized controlled trial, it was shown that two sessions of counselling were not significant for reducing post-abortion depression and tension.[26] Perhaps counseling immediately after abortion is not the right time because some people are tired and impatient to listen. One session counselling over five weeks during post-abortion period had no significant effect on their grief and depression level.[12] Perhaps the reason for the heterogeneity of two studies is the onset of the consultation or sessions of counselling (one session vs six sessions); in their study, post-abortion grief four months after the intervention and in the follow-up, period was consistent with the current study, which shows that the mourning is affected by time, and that over time, the effect of counseling becomes more evident.

Repeated measures ANOVA showed that time is a factor which plays an important role in reducing the rate of mourning in both groups. The passage of time makes people happy with various events, pleasant or unpleasant. Women may cope with abortion phenomenon or pleasant events such as re-pregnancy may occur, or living conditions may change.

In the current study, psychological counselling with cognitive behavioral approach was used in which women first expressed their feelings, and then people learned the concept and symptoms of mourning in a simple way, and finally, they learned how to avoid disturbing memories and return to daily life. In fact, in this approach, people are encouraged to experience better emotions and more appropriate behaviors by considering negative spontaneous thoughts and identifying and challenging cognitive distortions, and then by reconstructing those thoughts.

The presence of women together and hearing their stories and experiences was effective in making the participants more comfortable with the phenomenon of mourning. They considered abortion a divine test and believed that one should rely on God and accept God's will. They considered performing religious duties and attending religious ceremonies as one of the methods of adaptation. Perhaps one of the reasons for the success of this counseling method was the participants’ belief in God.

How women grieve depends on the personality of the grieving individual.[27] Bereavement and mourning vary in different cultures,[28] and cultural and social expectations affect how we deal with the phenomenon of grief. Religious beliefs have a positive effect on grief after fetal death and reduce its acceptance and psychological grief.[29]

The difference in sample size, duration of intervention or onset of counselling may explain the discrepancy of the result of different clinical trials.

Limitations and recommendations

Strengths of this study included counseling by a PhD student in reproductive health under the supervision of a psychologist, using counseling method with group cognitive behavioral approach, random sampling, measurement of grief score immediately after intervention and three months after the intervention. Limitations included the participants in the control group received no intervention. Therefore, we can distinguish that the positive effects of the intervention were associated with the cognitive behavioral counselling or contact between the participants and the investigator. On the other hand, intention-to-treat analyses were not performed. However, due to leak of blinding and a small sample size were other limitations. Obstetrical and personal information, and post-abortion grief questionnaire were completed based on the patient's self- expression.

It is recommended that in future trials, participants receive intervention immediately after abortion as soon as possible, participants in the control group receive an intervention in order to reduce the confounding variable and bias regarding the interpretations of the result. We also recommend that post-abortion counselling via group cognitive behavioral approach be compared with other methods.

Conclusion

According to the results of this study, it can be concluded that cognitive behavioral counselling can reduce the intensity of post-abortion grief or prevent the occurrence of complicated grief. Therefore, this method can be used as a preventive or therapeutic approach to control post-abortion grief and other psychological disorders.

A counseling program, depending on the patient's condition, can have positive effects on their future fertility outcomes. These programs are in line with the goals of reproductive health that can be used in health centers. However, it should be noted that if the counseling is done with the husband or parents as the most important supporters of women, and also if women receive social support, they will receive better results.

Financial support and sponsorship

This paper was a part of a Ph.D. thesis approved by Shahroud University of Medical Sciences with grant number (No. 97118). The authors wish to thank the Research Deputy for their financial support.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mr. Mohammad Reza Erfani, the director of Khalil Azad Clinic and all of the women who agreed to participate in this study.

References

- 1.Raphi F, Bani S, Farvareshi M, Hasanpour S, Mirghafourvand M. Effect of hope therapy on psychological well-being of women after abortion: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:598. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03600-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zareba K, La Rosa VL, Ciebiera M, Makara-studzi M, Commodari E, Gierus J. Psychological effects of abortion. An updated narrative review. Eastern J Med. 2020;25:477–83. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volgsten H, Jansson C, Svanberg AS, Darj E, Stavreus-Evers A. Longitudinal study of emotional experiences, grief and depressive symptoms in women and men after miscarriage. Midwifery. 2018;64:23–8. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Montigny F, Verdon C, Meunier S, Dubeau D. Women's persistent depressive and perinatal grief symptoms following a miscarriage: The role of childlessness and satisfaction with healthcare services. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20:655–62. doi: 10.1007/s00737-017-0742-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maccallum F, Bryant RA. Prolonged grief and attachment security: A latent class analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2018;268:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tseng YF, Cheng HR, Chen YP, Yang SF, Cheng PT. Grief reactions of couples to perinatal loss: A one-year prospective follow-up. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26:5133–42. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adib-Rad H, Basirat Z, Faramarzi M, Mostafazadeh A, Bijani A, Bandpy M. Comparison of women's stress in unexplained early pregnancy loss and normal vaginal delivery. J Edu Health Promot. 2020;9:14. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_381_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanschmidt F, Treml J, Klingner J, Stepan H, Kersting A. Stigma in the context of pregnancy termination after diagnosis of fetal anomaly: Associations with grief, trauma, and depression. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2018;21:391–9. doi: 10.1007/s00737-017-0807-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagheri L, Nazari AM, Chaman R, Ghiasi A, Motaghi Z. The effectiveness of healing interventions for post-abortion grief: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran J Public Health. 2020;49:426–36. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson OP, Langford RW. A randomized trial of a bereavement intervention for pregnancy loss. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2015;44:492–9. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adolfson A, Larrson PG, Bertero C. Effect of a structured follow-up visit to a midwife on women with early miscarriage: A randomized study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:335–30. doi: 10.1080/00016340500539376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nikcevic AV, Kuczmierczyk AR, Nicolaides KH. The influence of medical and psychological interventions on women's distress after miscarriage. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:283–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swanson KM, Chen HT, Graham JC, Wojnar DM, Petras A. Resolution of depression and grief during the first year after miscarriage: A randomized controlled clinical trial of couples-focused interventions. J Women's Health. 2009;18:1245–57. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tolin DF. Is cognitive-behavioral therapy more effective than other therapies? A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:710–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez MA, Basco MA. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy in public mental health: Comparison to treatment as usual for treatment-resistant depression. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42:87–98. doi: 10.1007/s10488-014-0546-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuijpers P, Cristea IA, Karyotaki E, Reijnders M, Huibers MJH. How effective are cognitive behavior therapies for major depression and anxiety disorders. A meta-analytic update of the evidence. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:245–58. doi: 10.1002/wps.20346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.David D, Cristea I, Hofmann SG. Why cognitive behavioral therapy is the current gold standard of psychotherapy. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:4. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kersting A, Dölemeyer R, Steinig J, Walter F, Kroker K, Baust K, et al. Brief internet-based intervention reduces posttraumatic stress and prolonged grief in parents after the loss of a child during pregnancy: A randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2013;82:372–81. doi: 10.1159/000348713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kersting A, Kroker K, Schlicht S, Wagner B. Internet-based treatment after pregnancy loss: Concept and case study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;32:72–8. doi: 10.3109/0167482X.2011.553974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mirzabigi S. 2017. Evaluation of the effectiveness of midwifery counseling with an existential approach on prenatal mourning. In: Reproductive health Department Shahroud University of Medical shahroud. Iran. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerns J, Cheeks M, Cassidy A, Pearlson G, Mengesha B. Abortion stigma and its relationship with grief, post-traumatic stress, and mental health-related quality of life after abortion for fetal anomalies. Womens Health Rep (New Rochelle) 2022;3:385–94. doi: 10.1089/whr.2021.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navidian A, Saravani Z. Impact of cognitive behavioral-based counseling on grief symptoms severity in mothers after stillbirth. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2018;12:e9275. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakano Y, Akechi T, Furukawa TA, Sugiura-Ogasawara M. Cognitive behavior therapy for psychological distress in patients with recurrent miscarriage. Psychol Res Behav. 2013;6:37–43. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S44327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Golmakani N, Ahmadi M, Asgharipour N, Esmaeli H. The relationship of emotional intelligence with women's post-abortion grief and bereavement. JMRH. 2018;6:1163–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adolfsson A. Women's well-being improves after missed miscarriage with more active support and application of Swanson's caring theory. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2011;4:1–9. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S15431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kong GW, Chung TK, Lok IH. The impact of supportive counselling on women's psychological wellbeing after miscarriage--A randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2014;121:1253–62. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodwin-Hawkins B, Dawson A. Life's end: Ethnographic perspectives. Death Stud. 2018;42:269–74. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2017.1396394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silverman GS, Baroiller A, Hemer SR. Culture and grief: Ethnographic perspectives on ritual, relationships and remembering. Death Stud. 2021;45:1–8. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1851885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allahdadian M, Irajpour A. The role of religious beliefs in pregnancy loss. J Edu Health Promot. 2015;4:99. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.171813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]