Abstract

The causes for variability of pro-inflammatory surface antigens that affect gut commensal/opportunistic dualism within the phylum Bacteroidota remain unclear (1, 2). Using the classical lipopolysaccharide/O-antigen ‘rfb operon’ in Enterobacteriaceae as a surface antigen model (5-gene-cluster rfbABCDX), and a recent rfbA-typing strategy for strain classification (3), we characterized the architecture/conservancy of the entire rfb operon in Bacteroidota. Analyzing complete genomes, we discovered that most Bacteroidota have the rfb operon fragmented into non-random gene-singlets and/or doublets/triplets, termed ‘minioperons’. To reflect global operon integrity, duplication, and fragmentation principles, we propose a five-category (infra/supernumerary) cataloguing system and a Global Operon Profiling System for bacteria. Mechanistically, genomic sequence analyses revealed that operon fragmentation is driven by intra-operon insertions of predominantly Bacteroides-DNA (thetaiotaomicron/fragilis) and likely natural selection in specific micro-niches. Bacteroides-insertions, also detected in other antigenic operons (fimbriae), but not in operons deemed essential (ribosomal), could explain why Bacteroidota have fewer KEGG-pathways despite large genomes (4). DNA insertions overrepresenting DNA-exchange-avid species, impact functional metagenomics by inflating gene-based pathway inference and overestimating ‘extra-species’ abundance. Using bacteria from inflammatory gut-wall cavernous micro-tracts (CavFT) in Crohn’s Disease (5), we illustrate that bacteria with supernumerary-fragmented operons cannot produce O-antigen, and that commensal/CavFT Bacteroidota stimulate macrophages with lower potency than Enterobacteriaceae, and do not induce peritonitis in mice. The impact of ‘foreign-DNA’ insertions on pro-inflammatory operons, metagenomics, and commensalism offers potential for novel diagnostics and therapeutics.

Keywords: Escherichia coli, Salmonella, O-antigen, Alistipes, Prevotella, Bacteroides, Parabacteroides

Introduction

An operon is a functional unit of DNA that consists of a cluster of contiguous genes, transcribed together to control cell functions, including the production of the O-antigen component of lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which is widely present and variable in gram-negative bacteria. The phylum Bacteroidota (Bacteroidetes), composed primarily of gram-negative gut commensals (6–10), is also known to have several opportunistic pathogenic species (‘pathobionts’) (11–19), which for unclear reasons have commensal/pathogenic dualism. Concerningly, species from the phylum have been proposed as future probiotics because some strains modulate gut immunity locally (6, 20, 21) or influence the susceptibility to chronic extra-intestinal diseases (e.g., Parabacteroides goldsteinii attenuates obstructive pulmonary disease (15).

The precise role of Bacteroidota in chronic inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), namely Crohn’s disease (CD), remains undefined (22). Supporting a pathogenic role in IBD complications, we recently discovered that the inflamed bowel of patients with surgical/severe CD have cavitating ‘cavernous fistulous tract’ micropathologies (CavFT) resembling cavern formations, harboring cultivable bacteria, including Escherichia coli and Bacteroidota (5, 23). Focused on a few CavFT species, genomic analyses of consecutive Bacteroidota isolates (Parabacteroides distasonis) from unrelated patients that underwent surgery for CD suggested, for the first time, that certain bacteria (from a novel lineage in NCBI databases) are adapting to CavFTs, swapping large fragments of DNA with Bacteroides, and are likely transmissible in the community (23). To classify P. distasonis and other cultivable Bacteroidota, and to facilitate the orderly study of such commensal/pathogenic dualism in the phylum, we recently proposed the use of the rfbA gene for genotyping Bacteroidota. Of interest, rfbA-typing suggested that historical P. distasonis strains isolated from pathological sources belonged to one of four rfbA types (3).

Compared to the lipid A gene lpxK (which was highly conserved), rfbA-typing studies demonstrated that the O-antigen (rfb) genes are sufficiently variable to be better associated with the variable pathogenic potential of Bacteroidota for bacterial genotypic classification. Since lipid A in Bacteroidota induces lower TLR4 inflammatory activation (6, 15, 21, 24) compared to E. coli, and since the role of O-antigen/LPS in Bacteroidota is poorly understood (20), herein, we conducted an expanded typing analysis across all genes of the rfb operon in Bacteroidota using i) existing complete genomes and NCBI genome databases, ii) new genomes sequenced from CavFT, iii) the classical Enterobacteriaceae rfb operon contiguity as referent, and vi) using Parabacteroides and Alistipes as emerging pathogenic/probiotic models (1, 2) to identify potential genomic features impacting surface antigens favoring Bacteroidota commensal/pathobiont dualism.

Results

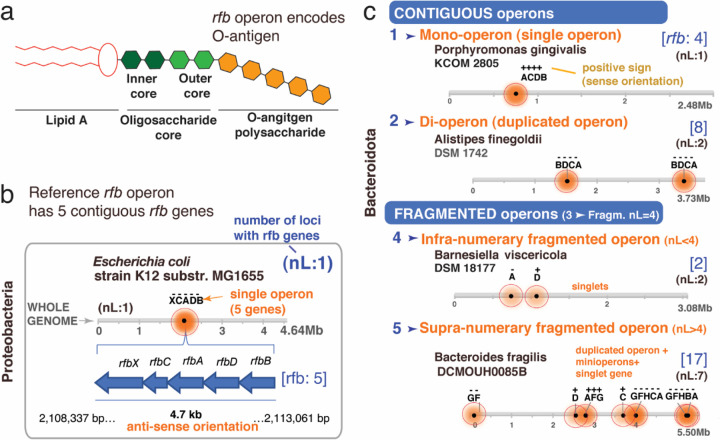

The classic rfb operon is contiguous in Enterobacteriaceae.

As a referent to illustrate the arrangement of rfb genes involved in the O-antigen synthesis operon in Enterobacteriaceae, we analyzed reference genomes from E. coli, Klebsiella variicola, and Salmonella enterica. A schematic of the LPS/O-antigen molecule is shown in Figure 1A. In E. coli K12, Figure 1B illustrates the contiguous arrangement of five genes which functionally enable the en bloc transcription of the rfb operon (rfbABCDX). Regardless of transcriptional orientation (positive/negative sense), other Enterobacteriaceae have the same contiguous arrangement of the rfb genes. Notably, while the length of rfb operons vary across this family, bacteria predominantly have at least four genes (rfbABCD), organized contiguously, with sporadic singly duplicated genes. Contiguity is so conserved within the family that Salmonella spp. have operons with up to 15 consecutive rfb genes (Supplementary Figure 1A-B).

Figure 1. The rfb operon in Enterobacteriaceae is contiguous, but in Bacteroidota it is often fragmented into ‘minioperon’.

A) Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and O-antigen schematics. B) Classical rfb operon with 5 contiguous genes in E. coli K12 (rfbXABCD; XCADB; [rfb:5]). Horizontal lines represent the bacterial genome length, distribution of rfb genes/operons (shaded circles; darker = more genes) and rfb gene orientation (+, sense; -, antisense). nL: n of rfb clusters or gene singlet loci. Note orientations/duplications. C) Five categories of operon arrangement & ‘minioperon’ fragmentation in Bacteroidota. Supplementary Figure 1C illustrates in context rfb operons/fragmentation for Alistipes, Bacteroides, Parabacteroides, Prevotella, Paraprevotella, Barnesiella, Tannerella, Odoribacter and Porphyromonas.

The rfb operon in Bacteroidota is often fragmented into ‘minioperons’.

To assess the spatial integrity of the rfb operon in Bacteroidota, we next examined the rfb gene profile (presence/absence) in available complete genomes. Analysis revealed that the rfb genes in Parabacteroides, Bacteroides, and Prevotella were not contiguous but fragmented and dispersed throughout the genome. In contrast, Alistipes, Porphyromonas and Odoribacter have rfb operons composed of the same primordial genes as Enterobacteriaceae (rfbACDB), being intact and/or duplicated, supporting their genomic potential to be functionally capable of LPS-proinflammatory induction. Within the phylum, operon fragmentation products, herein referred to as rfb “minioperons”, result in various combinations of rfb singlet genes and doublets/triplets with variable orientations (sense: +; antisense: -, Supplementary Figure 1C). With E. coli as referent, using four rfb genes (n=4) as the median maximum number of contiguous genes observed among Bacteroidota in this study, herein we propose that rfb operons in Bacteroidota can be classified into at least five categories: i) Mono-operon (single contiguous operon, regardless of numbers of genes in cluster/locus), ii) Di-operon (duplicated operon), iii) fragmented normo-numerary operon (operon fragmented with 4 rfb clusters/loci, nL=4), iv) fragmented infra-numerary operon (nL<4 clusters/loci), and v) fragmented supernumerary operon (nL>4 clusters/loci; Figure 1C). Used alongside a baseline referent, this system of categorization and cataloguing may be applied to any operon system.

Envisioning the potential combinatorial variability for the O-antigen via the theoretical pairwise combination of rfb genes in Bacteroidota, we next determined that mathematical permutations of minioperons could yield thousands of possible combinations unlikely to yield functional O-antigen polysaccharides (Supplemental Figure 2A), which proves technically challenging to verify experimentally for all bacteria by requiring innumerable grow conditions.

Minioperon patterns in Parabacteroides suggests rfb gene distancing mechanism.

Since the study of potential operon fragmentation mechanisms could be better achieved using strains with fully sequenced genomes, we next conducted an arrangement analysis to determine if rfb operon fragmentation was common within any given species and if they followed statistically significant patterns among unrelated strains of the same species. Using P. distasonis as a model Bacteroidota species and strain ATCC8503 (peritonitis, USA/1935) as the referent species for the genus Parabacteroides, analyses revealed that P. distasonis have their rfb operons invariably fragmented (12/12, Fisher’s exact P<0.00001), following unique patterns of gene combinations, duplications, or orientations that are significantly more likely to be supernumerary than infra-numerary (Fisher’s exact P=0.0001, Figures 2A and 1C). These findings suggest that some species are more likely to gain rfb loci (P. distasonis), compared to others which could be more likely to lose rfb loci (Barnesiella viscericola).

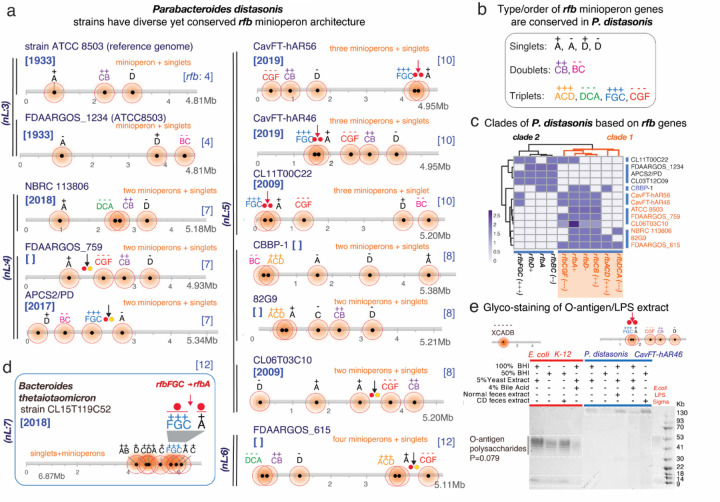

Figure 2. The occurrence, patterns and inversions of rfb minioperons in P. distasonis and B. thetaiotaomicron suggests mechanism of operon fragmentation in Bacteroidota.

A) Fragmentation of rfb operon in P. distasonis is in modern times supernumerary compared to ATCC8503 strain from USA/1933. B) Fragmentation has resulted in conserved singlet, doublet/triplet patterns in P. distasonis. C) Heatmap clustering of P. distasonis strains based on rfb minioperon shows distinct clades. Additional information is available in Supplementary Figure 2B. D) Unique rfbFGC->rfbA minioperon distancing pattern (downward red/black arrows and solid circles) in B. thetaiotaomicron is also present in novel CavFT strains of P. distasonis from gut wall lesions in Crohn’s disease. Notice the orientation sense and patterns. E) SDS-PAGE of LPS extract analysis of E. coli and P. distasonis CavFT-46 shows that P. distasonis is unable to produce O-antigen polysaccharides in diverse growth conditions (Fisher’s exact P=0.079).

Fragmentation patterns were also highly conserved among P. distasonis. Specifically, rfbA and rfbD genes were present in minioperons or as singlets, whereas the genes rfbB, rfbC, rfbG and rfbF were exclusively present only as doublet- or triplet-minioperon arrangements (Figure 2B). Based on such conservancy, P. distasonis strains belong to at least two distinctive phylogenetic clades (Figure 2C, Supplementary Figure 2B), suggesting that not all P. distasonis would be the same, and emphasizing the need to better classify Bacteroidota isolates for functional studies.

Mechanistically insightful, outside of this species we found that a unique combination and distancing of two rfb minioperons (rfbFGC->rfbA; abbreviation for rfbFGC(+++) positive-sense triplet followed by a rfbA(+) positive-sense singlet), overrepresented in some P. distasonis strains (n=6/12, Fisher’s exact P<0.001, vs. numerous other possibilities), was also present in a B. thetaiotaomicron strain CL15T119C52 (Figure 2D), a phenomenon not previously reported in the literature.

Considering that B. thetaiotaomicron lacks LPS-polysaccharide formation (25) and has anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties (18, 19), the presence of such rfbFGC->rfbA fragmentation pattern in both P. distasonis/B thetaiotaomicron suggests a mechanism for operon fragmentation that could explain beneficial effects for both species/strains (2). Remarkably, an inter-genus rfbFGC->rfbA pattern, exclusively present in P. distasonis strains of CavFT origin and CL11T00C22 (5), have conserved minioperon sequences but variable inter-minioperon rfbFGC->rfbA distances, suggesting that DNA insertion within the flanking rfb genes could be the reason for gene-gene separation in an ongoing permissible process of gene exchange between P. distasonis and B thetaiotaomicron.

Of novelty, variable inter-minioperon orientations for the same rfbFGC->rfbA pattern in other P. distasonis genomes (APCS2/PD, FDAARGOS_615, and CL06T03C10) suggest the existence of conserved rfbFGC->rfbA inversions with a pivot point in the inter-minioperon rfbFGC->rfbA region. This observation indicates that such a potential gene-gene separation mechanism is highly conserved, yet variable. Furthermore, it offers an evolutionary explanation to the presence of unique arrangements across certain strains, lineages, or possible niches that could reflect favored co-habitation of both genera, genetic exchange, selection, and niche adaptation (notice the red vs. black arrows for rfbFGC->rfbA in Figures 2A & 2D).

To elucidate the effect of minioperons on LPS/O-antigen production and structure, we opted to verify the presence/absence of the O-antigen polysaccharide in P. distasonis CavfT-hAR46, under five unique growth conditions, as a cultivable Bacteroidota model with 5 rfb minioperon fragments (vs. E. coli with one rfb operon). Of functional importance, the classical rfb operon in E. coli effectively produced a typical O-antigen/polysaccharide as expected in all conditions, with repeated bands between 41 and 53 kb in SDS-PAGE (Figure 2E) (26, 27). However, as expected for a P. distasonis strain with supernumerary rfb fragmentation, P. distasonis did not yield O-antigen polysaccharides in any of the conditions, suggesting that supernumerary rfb fragmentations are likely to be non-functional (5/5 vs. 0/5, Fisher’s exact P=0.0079). As a result, lipooligosaccharide products (LOS) were produced instead of LPS, similar to what has recently been described for B. thetaiotaomicron (25).

The rfb operon in Alistipes is intact or duplicated suggesting benefit for survival.

Contrasting Parabacteroides, the Alistipes genus primarily exhibits no operon fragmentation. Unique conserved organization and orientation was observed in all examined Alistipes species which have 4-gene contiguous rfb operons (BDCA or CADB; Figure 3A). When fragmentation was present (A. shahii, A. dispar), Alistipes have minioperon doublets (rfbCA, DB, AC, GF) not seen in Parabacteroides, furthers supporting that genus-specific mechanisms of operon fragmentation or conservation vary across Bacteroidota.

Figure 3. The rfb operon in Alistipes is contiguous and duplicated suggesting evolutionary benefit.

A) Alistipes has contiguous rfb operons with frequent duplication and less common incorporation of rfb minioperon duplets. B) Patterns of conserved minioperons in Alistipes differ from Parabacteroides. C) Schematics of gene-gene rfb distances measured within and between minioperons. D) Parabacteroides and Bacteroides demonstrate the greatest variance in number of rfb operon fragments and gene-gene distances. Alistipes and Enterobacteriaceae are similarly contiguous. Intergene distances for Parabacteroides, Bacteroides and Prevotella were greater than Enterobacteriaceae (0.54±0.84Mb, 0.49±0.86Mb, 0.34±0.32Mb, respectively, vs. 0.13±0.46Mb, P<0.001). Alistipes gene distribution is similar to Enterobacteriaceae (0.17±0.49Mb, P=0.79). E) Minioperon sequence homologies for Alistipes vs. Parabacteroides based on minioperon orientation between and within genera/species. Two tailed-T tests P<0.01 **, P<0.001 ***. F) Alignment and G) phylogeny based on rfb operon sequences. Note that Alistipes clusters are driven by the sense/antisense orientation of the operons.

Intriguingly, as a major difference within other Bacteroidota, most Alistipes species have duplicated operons (5/8 vs. 1/22, B. fragilis, Fisher’s exact P=0.0018), indicating that the genus has genomic potential for enhanced O-antigen production and possibly pro-inflammatory LPS effects that could be necessary or beneficial for Alistipes adaptation/survival. Alternatively, operon duplication with minimal fragmentation suggests that i) fragmentation is non-sustainable or rather deleterious for Alistipes, and/or ii) its genetic mechanisms of operon maintenance allow for operon variability (duplication, inversions, sequence), but not for gene-operon separation, unlike Parabacteroides in which fragmentation predominates (12/12 vs. 2/8, A. shahii & A. dispar, Fisher’s exact P=0.0049). No rfb singlets were observed in Alistipes.

The rfb minioperon types in Alistipes and Parabacteroides indicate that gene patterns and orientations are unique and vary, being potentially useful as signatures for lineage identification and classification (Figure 3B). When we quantified the magnitude of fragmentation (gene-gene distances in number of nucleotides) across genera, we found that Parabacteroides, Bacteroides and Prevotella had similarly more fragmentation on average than Enterobacteriaceae (P <0.001, P=0.0151, P=0.010, respectively), but not Alistipes compared to Enterobacteriaceae (2.1 vs. 1.6, P=0.89, Figure 3C-D).

Minioperon conservation in P. distasonis encompasses 85 years of history.

Using Parabacteroides and Alistipes as genus models for Bacteroidota (1, 2), we then quantified the rfb sequence conservation (% similarity among strains)(3), since conservation indicates functional/evolutionary advantages (28). Analysis showed that, irrespective of orientation, the doublet rfbCB sequences, present in 80% of P. distasonis, and the rfbACD triplets have homologies ranging from 72 to 99.8% (77.5±5.15%), contrasting the much lower operon similarities across Alistipes (range 27.5 to 83.7%; 50±16.4%, P<0.001; Supplementary Figure 3).

Considering that the P. distasonis strains examined in this study span 85 years and various geographic locations, from ATCC8503 (USA, c.1933) to 82G9 (South Korea, c.2018), the high minioperon sequence similarity (P<0.001 Figure 3E) indicates well-conserved genomic features across time and space. However, this conservation cannot explain the observed rfbFGC->rfbA variability. Instead, it implies that an independent genomic mechanism might be responsible for generating modern rfbFGC->rfbA variants over time, which were not present in the founding strain ATCC8503, 85 years ago.

Although the operons in Alistipes are more similarly organized (BDCA) than Parabacteroides, the sequences are more variable, depending on operon orientation (Figure 3F-G). Of interest, duplicated minioperons in Parabacteroides are virtually identical, which contrasts the sequence dissimilarity seen among duplicated rfb operons in Alistipes (T-Test P=0.039, Figure 3E). The variable homologies across Alistipes indicate that they may i) produce a more variable array of LPS/O-antigens, with at least two different types of O-antigens if operons are duplicated, and/or ii) have higher virulence in vivo. Given the emergence of Alistipes as an emerging genus in human diseases (1), we developed PCR primers for rfbBDCA/ACDB operons to facilitate their future study in Alistipes (Supplementary Table 1).

Genome ‘rfb operon profiling’ shows minioperon occurrence is not random.

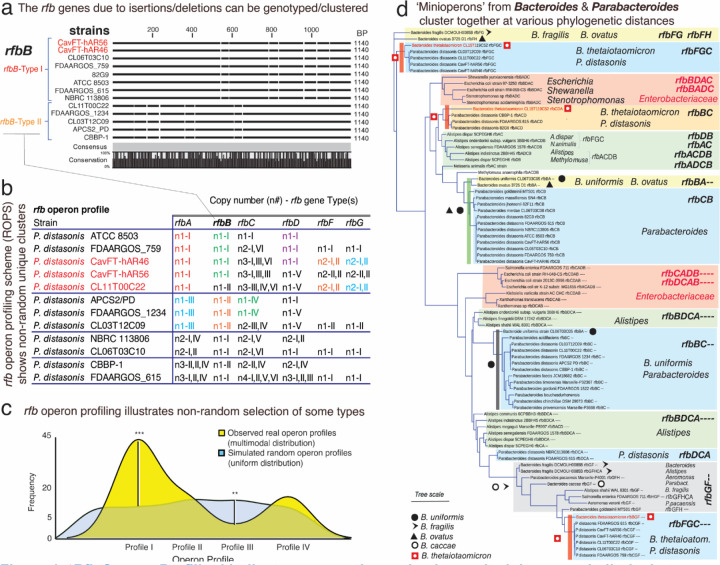

To further characterize the rfb genes and the genome-wide operon patterns in Bacteroidota, we propose a global ‘rfb operon profiling’ system (GOPS). Using our rfbA-typing methodology (3) and P. distasonis strains as a model, we showed that it is possible to discern the strains examined based on distinct genotypes for each rfb gene (rfbB-types n=2, rfbC-types n=6, rfbD-types n=4, rfbF-types n=2, rfbG-types n=2, Figure 4A & Supplementary Figure 4). By applying the previous scheme to generate a combined alphabetic-numeric profile of the entire rfb operon, accounting for both copy number and rfb genotype, we generated summary profiles for testing (Figure 4B). Of note, this system may be broadly applied to type other operon genes. Remarkably, the GOPS profiles identified were determined to be reproducible, favoring profiles that are statistically different from random profiles, supporting the assumption that minioperon arrangements have been selected over time (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. ‘Rfb-Operon Profiling’ indicates non-random selection and minioperon similarity between Parabacteroides and Bacteroides, namely B. thetaiotaomicron.

A) Gaps and insertions in rfb gene sequences designate different rfb-types using protocols described for rfbA-typing (3). Supplementary Figure 4 illustrates the rfb-typing of rfbC/D/F/G. B) Example of global rfb operon profiling system (GOPS) for P. distasonis. C) Density plots between random and real rfb operon profiles in P. distasonis. Observed types are statistically different from a random (uniform) distribution (**, *** for P<0.05 and P<0.01, respectively). D) Phylogenetics across Bacteroidota and Enterobacteriaceae based on rfb mini/operon sequences. Remarkably, several Bacteroides species, but namely B. thetaiotaomicron CLT5T119C52, cluster together with several Parabacteroides, especially P. distasonis, irrespective of minioperon considered (red squares; further details in Supplementary Figures 5).

Minioperons from Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron and Parabacteroides cluster together.

Considering the challenges of examining all Bacteroidota minioperons with current operon mapping tools (29–32) and the high prevalence of incomplete draft genomes, we next used the NCBI-BLAST database to further investigate if the observed minioperon patterns were i) non-random, and ii) either widespread across various phyla in the NCBI database or exclusive to particular genera or species. Using P. distasonis minioperon sequences, we found that the rfb doublets and triplets are limited to P. distasonis strains exhibiting ≥99% coverage. Low-matching hits for rfb operons/minioperons present with lower (≤24%) sequence coverage were more similar to Bacteroides species (B. thetaiotaomicron, B. caccae, B. cellulosilyticus) and more distant (≤3% coverage) from Proteobacteria, suggesting that the evolution of O-antigen in Parabacteroides has been closer to Bacteroides than to Proteobacteria (Supplementary Table 2). Phylogenetic analysis of mini/operons from Enterobacteriaceae and Bacteroidota with the best BLAST/NCBI sequences (lowest E-scores) further illustrates the well-conserved nature of Bacteroides spp. minioperons across genera, and the little similarity to Proteobacteria (Figure 4D).

Of utmost evolutionary interest, a specific strain of B. thetaiotaomicron (CLT5T119C52/USA/c.2018) clustered in three distinct clades (rfbFGC, BC, and FGD---) with P. distasonis, including CavFT strains. This finding indicates that Parabacteroides/Bacteroides clusters are likely to have a common ancestor or high affinity for DNA exchange and horizontal ‘operon’ transfer (Figure 4D). These Parabacteroides/Bacteroides minioperon clades also harbored B. uniformis or B. ovatus, but not Alistipes or Enterobacteriaceae.

Operon fragmentation through ‘foreign DNA’ insertions from Bacteroides.

Given the known high-frequency of horizontal gene transfer (HGT) between Bacteroides and gram-negative microbes in the gut (33), the presence of rfb minioperons in Bacteroidota could indicate that sharing certain rfb patterns could reflect adaptation/selection benefits. However, such HGT exchange theory could not explain the observed genus-specificity and low frequency of minioperons in other taxa. Therefore, we hypothesized that the cumulative insertion of ‘foreign DNA’ between rfb genes could account for the fragmentation of operons and the variable rfbFGC->rfbA separation distances observed in Figure 2A-D. We further hypothesized that the genetic exchange in Bacteroidota could be a specialized event, confined to niches with compatible species, rather than occurring randomly in the gut. Supported by clades in Figure 4D (containing Bacteroides matching Parabacteroides of CavFT origin), this exchange could explain the low representation of rfb minioperons in NCBI. Testing these hypotheses, we first performed whole genome rearrangement analysis to quantify the percentage of genome matching sequences and their fragment sizes. We then examined the sequences located within fragmented rfbFGC->rfbA minioperons and select surface antigenic fimbriae inter-minioperon regions as depicted in Figure 5A.

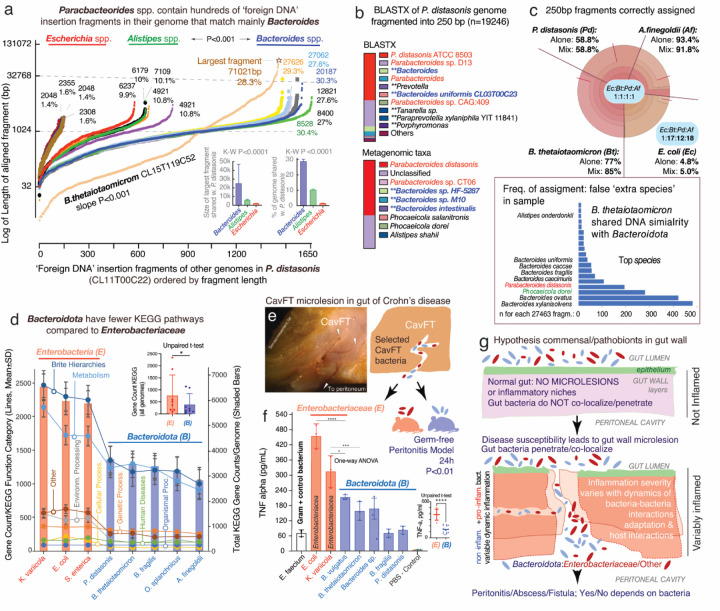

Figure 5. Fragmentation of nonessential operons is driven by insertions of ‘foreign DNA’, mainly Bacteroides.

A) Schematics of O-antigen (rfb), fimbriae (fim) and ribosomal (rrn) gene operons tested for DNA insertions. B) Example of P. distasonis inter-minioperon DNA fragment found in other genomes. C) % of DNA from one species common to the genome of 4–5 other species within the genus. D) Schematics showing source of ‘foreign DNA’ insertions into the rfbFGC->rfbA space separating the rfb genes in P. distasonis. E) ‘Pure’ P. distasonis DNA fragments intermixed within inter-minioperon ‘foreign DNA’ insertions. F) Genus sources and % of ‘foreign DNA’ fragmenting the rfb and fim minioperons in P. distasonis, as in Figure 5A. Bacteroides (B. thetaiotaomicron, B. fragilis, B. ovatus, B. vulgatus) are the main source of ‘foreign DNA bombardment’ (P<0.0001 vs. Alistipes and Escherichia). Additional information is available in Supplementary Table 3. G) Ribosomal operons (rrn, deemed essential) are not fragmented in P. distasonis, despite presence of ‘foreign DNA’ in vicinity. *, **, ***, for P<0.01, P<0.001, P<0.0001, respectively. Supplementary Table 4 shows rrn operons are not fragmented in other genera, i.e., Prevotella, Bacteroides, Alistipes, and Porphyromonas.

Genome rearrangement analyses showed that 30–45% of the P. distasonis genome sequence, in various fragment sizes, match that of B. thetaiotaomicron, confirming the two strains belong to different clades at genome scales. However, such finding also emphasizes the potential for disruptive random ‘foreign DNA’ insertions into operons, since genome alignment showed that the largest shared DNA fragment was also present in other Bacteroides (Figure 5B-C). Of mechanistic interest, we found that the DNA present in the inter-minioperon rfbFGC->rfbA sequences represent an overlapping mixture of DNA that matched primarily Bacteroides (27–45%; B. thetaiotaomicron, B. fragilis, P. ovatus), with limited similarity to Alistipes or E. coli, and no evidence of similarity to random sequences (shuffled genomes; Figure 5C-D). Notably for P. distasonis, the entire inter-minioperon sequence represents the combination of ‘foreign’ Bacteroides DNA intermixed with DNA sequences verified by BLAST as pure P. distasonis (Figure 5D-E). This suggests that, over time, such inter-minioperon sequences have either become specific for P. distasonis, or they represent insertions of ‘foreign DNA’ from other P. distasonis. Examination of rfb inter-minioperon regions in other strains and in the antigenic fimbriae (fim) minioperons in P. distasonis strain CL11T00C22 (strain with most complete set of fim genes (34), Figure 5F) confirmed the same pattern of Bacteroides predominance.

No fragmentation in ribosomal operons.

Lastly, to determine if operon fragmentation also affected essential genes, we examined ribosomal rrn operons (~5000bp containing highly conserved 16S, 23S and 5S rRNA/tRNA genes). We i) assessed rrn operon integrity, and ii) quantified the amount of B. thetaiotaomicron DNA found in or near the rrn operons of diverse genomes; as an analytical control, we also quantified the amount of B. thetaiotaomicron DNA found in randomly generated 5000bp-loci. Analysis revealed that none of the P. distasonis rrn operons studied (encompassing 21 rRNAs and interspersed tRNA genes) were fragmented or contained B. thetaiotaomicron (Fisher’s exact P=0.0081, vs. randomly selected loci; 0/7 vs. 12/20; Figure 5G), despite being exposed to the same ‘foreign DNA insertion pressure’, which was inferred by comparing the average distance of the nearest B. thetaiotaomicron DNA insertion to the rrn operon (vs. distances to randomly generated locus coordinates; T-test P=0.79). Interestingly, multiple large spans (50,000+bp) of bacterial genome were found to be free of B. thetaiotaomicron DNA which could be considered as a future strategy to identify essential operons.

‘Foreign DNA’ insertions in Bacteroidota on metagenomic statistics.

Ranking analysis of all DNA fragments from 15 genomes that aligned to P. distasonis CL11T00C22, shown as dot plots in Figure 6A, illustrates that Bacteroides are the most likely sources of recent genomic exchange with Parabacteroides based on the number and size of homologous DNA fragments. Especially intriguing is that B. thetaiotaomicron strain CLT5T119C52, again, has the most distinctive sharing pattern (largest number/longest fragments) with Parabacteroides, suggesting that DNA exchange is an active, still ongoing interspecies process. Similar insertions of B. thetaiotaomicron DNA were also observed in other inter-minioperon regions in other genera (B. fragilis, Barnesiella viscericola, P. intermedia, and A. shahii). Analysis indicates that not all species are equally likely to receive B. thetaiotaomicron, further supporting that inter-species exchange is not random across the phylum, but rather, driven by yet unknown pairing factors among species that share environments where other Bacteroides may be DNA donors (B. fragilis, B. ovatus; Supplementary Figure 6 & Supplementary Table 5).

Figure 6. Impact of ‘Foreign DNA’ insertions in Bacteroidota on metagenomics, antigenic operons and bacteria-bacteria inflammatory interactions in a model of gut microlesions.

A) Plot of DNA fragments that align between Parabacteroides CL11T00C22 and Bacteroides, Alistipes, Escherichia genomes (n=16) ordered by length of each aligning fragment. Notice genus-genus differences. B. thetaiotaomicron CL15T119C52 has unique pattern of abundant fragments (maximum fragment sizes and average % of genome shared, inset bar plots). B) BlastX (protein) and metagenomic (nucleotide) taxonomic analyses of 250bp-fragmented P. distasonis genome. Notice ‘extra species’ assigned by metagenomics (inflation), reflecting ‘foreign DNA’ insertions/exchange across Bacteroidota, and not real presence of species (inset bar plot). The n of ‘extra species’ varied with fragment length (Pearson corr. 0.84, P<0.05). The performance of BLAST and BLASTX depends on bacterial genome (Supplementary Figure 8). C) Metagenomic community simulation with Bacteroides, Parabacteroides, Alistipes, and Escherichia (1:1:1:1 genomes). Krona plot (relative abundances within hierarchies of metagenomic classifications (35)) illustrates E. coli sequences are poorly assigned to E. coli leading to relative ratio overestimation of Bacteroidota abundance (1:17:12:18; see Krona plots for individual genomes (‘Alone’) in Supplementary Figure 9). Bacteroides is commonly listed as ‘extra species’ (bar plot; complete list in Supplementary Figure 7) D) KEGG pathway and total gene counts in Enterobacteriaceae and Bacteroidota, highlighting the significant differences for Bacteroidota (details in Supplementary Table 7). E) Glycostaining of LPS extracted from E. coli and P. distasonis cultured in different media. F) Average pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion by bacteria in the stimulation, indicating that Bacteroidota release less pro-inflammatory cytokines compared to Enterobacteriaceae. G) Hypothetical model of gut microlesions with colonization of commensal/pathobionts modulating inflammation. Peritonitis model showed mice with Enterobacteriaceae had fatal peritonitis, but not if receiving Bacteroidota B. thetaiotaomicron, B. fragilis, or P. distasonis. *P<0.01; ****P<0.00001.

With a large number of ‘foreign DNA’ insertions in the genome that could disrupt operons (n=1450–1650, x-axis Figure 6A), there is also potential for impacting metagenomic results. In examining the taxonomic assignment of inter-minioperon sequences using BLAST, we first illustrated the potential for metagenomic overestimation (‘inflation’: calling of ‘extra species’ in a sample when they are not there). BLAST suggests this could be important for strains avid to share DNA, but not for non-avid strains. While numerous inter-minioperon sequences matched to several B. thetaiotaomicron strains in NCBI with 100% coverage and >99% identity (81% of top hits), in a few cases (<4%) DNA matched other Bacteroides with lower similarity (<85%), such as B. longzhouii or B. faecis, and B. fragilis (21.4% top hits, Supplementary Table 6). Together, as illustrated in Figure 5D-E, analyses indicate DNA insertion similarity is more likely with Bacteroides, being restricted to Bacteroidota. To expand these BLAST-derived inferences, we used the BV-BRC metagenomics workflow for taxonomic classification of DNA sequences ‘in bulk’ to inspect entire genomes. By fragmenting the genome of selected strains into equal nonoverlapping 250bp simulated ‘reads’, we determined, in-silico, that the species inferred from inter-minioperon sequence queries in NCBI were also reproducible by metagenomics.

Since metagenomics uses sequences to deduce i) taxonomic composition using BLAST (nucleotide database), or ii) taxonomic composition and pathways/functions using BLASTX (protein database), ‘foreign DNA’ insertions in Bacteroidota affect the accuracy of these tools. The impact of ‘foreign DNA’ insertions can be visualized for both ‘individual absolute metagenomic’ analyses (fragmented genomes analyzed individually, Figure 6B), and on ‘relative metagenomic analyses’ for a simulated community with four genomes (A. finegoldii, B. thetaiotaomicron, P. distasonis, and E. coli, 1:1:1:1, 1X and 20X, Figure 6C). Although metagenomics aligns fragments/reads into contigs (algorithm assumption) and then finds their best match in a database with genes representing selected reference strains (BV-BRC n=24868; 16840 species; 30573 taxon units), analysis shows the presence of DNA from numerous Bacteroidota, especially the species shown by NCBI-BLAST in inter-minioperon regions. Top species for B. thetaiotaomicron included B. xylannisolvens, B. ovatus, P. dorei and P. distasonis, further confirming inter-species affinity for selective genetic sharing. Diagnostically relevant, and as anticipated, results also illustrate that metagenomic workflows could overestimate diversity by suggesting the presence of ‘extra species’ not actually present in a sample. Of note, the calling of ‘extra species’ by metagenomics depends largely on the fragment length used; however, while the number of fragments called ‘extra species’ is reduced as fragments get longer (from 100bp to 16000bp), the relative presence of ‘extra species’ increases with fragment length (Pearson’s P<0.05), confirming overestimation and suggesting the need of algorithm revision in current workflows.

Assessing communities in confined micro-niches will remain challenging using current metagenomics, since underestimation of present species (‘deflation’: species underestimated in abundance or deemed absent from sample) could also occur in cases where pathobionts/commensals coexist. For example, our relative community analysis showed that if a species is largely under-assigned by metagenomics (E. coli, ~4%, Figure 6C), there will be further overestimation of Bacteroidota ratios (12-to-18-fold magnification vs. E. coli, Figure 6C and Supplementary Figure 7).

Reduced KEGG pathways, TNF-alpha induction, and peritonitis by (CavFT) Bacteroidota.

Since a widespread process of DNA insertions throughout the genome could affect the functionality of various operons and genetic pathways, we next tested if such a phenomenon of operon disruption could be visualized by observing a lower number of functional pathways using a pathways database. By using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), a large-scale molecular dataset generated by genome sequencing, high-throughput experiments, and manual curation to infer enzymatic pathways across bacterial genomes (36), we confirmed that Bacteroidota have significantly less pathways than Enterobacteriaceae (T-test, P<0.05). Although the database may be biased towards Enterobacteriaceae due to more published evidence, Figure 6D demonstrates that selected Bacteroidota have significantly fewer functional pathways responsible for ‘metabolism’ and ‘environmental information processing’, while there was no difference for pathways responsible for ‘organismal systems,’ ‘human diseases,’ ‘genetic information processing,’ and ‘cellular processes’, supporting that the findings are well-controlled for basic pathways functions.

Of interest, when testing representative CavFT bacterial isolates derived from the gut wall of patients with CD in our laboratory (Figure 6E), we determined that the overall inflammatory potential of bacteria on murine macrophages was significantly reduced compared to Enterobacteriaceae. Figure 6F shows that TNF-alpha production by macrophages cultured in vitro (RAW264.7 cells) exposed to heat-treated bacterial extracts was about half the immune-proinflammatory potential observed for E. coli and Klebsiella variicola. Controlling for the apoptotic effect that bacterial extracts could have on macrophages at different extract dilutions, (measured using cell viability MTT assay), TNF-alpha data shows that Bacteroidota isolates from CavFT have non-inflammatory antigenic phenotypes compared to Enterobacteriaceae (e.g., O-antigen rfb operons) or Enterococcus faecium (gram-positive control). To further validate in vivo the sub-inflammatory potential of CavFT Bacteroidota, we injected suspensions of live bacteria into the peritoneal cavity of germ-free Swiss Webster mice to quantify their inflammatory potential. Our peritonitis model, based on 270,000 real-time telemetry data points, revealed that the mice receiving E. coli or K. variicola became febrile, then hypothermic, lethargic, and moribund within 24h post injection, while mice receiving CavFT Bacteroidota only became transiently hypothermic following the injection, overall being clinically normal or telemetrically less active until the end of study 24h post injection.

Based on evidence of antigenic operon fragmentation by Bacteroides and the reduced proinflammatory potential of Bacteroidota in vitro and in vivo, Figure 6G depicts a hypothesis where Bacteroidota invade, interact, and adapt to gut wall micro-niches where other enteric bacteria (e.g., Enterobacteriaceae and Bacteroidota) may be present and dynamically fluctuate to explain the cyclical remission-flare dynamics of gut wall inflammation and complications in chronic bowel diseases like CD.

Discussion

To explore the causes of pro-inflammatory surface antigen variability affecting gut pathobiont dualism within Bacteroidota, this study initially assessed the integrity of the rfb operon utilizing a selected set of complete genomes. Validation of findings was achieved by extending the analysis to other genomes and annotated sequence repositories, mainly using NCBI/BLAST. Of note, Bacteroidota have their rfb operons either intact (Odoribacter, Porphyromonas gingivalis), duplicated (Alistipes) or, mainly, completely or partially fragmented into ‘minioperons’, which can be classified into at least 5 categories using a broadly-applicable operon cataloguing system (Figure 1C). Overall, minioperons are highly-conserved features within genera, non-random, rare across NCBI databases, and form distinctive patterns sporadically shared among distant species, indicating a common mechanism for operon fragmentation within the phylum. By characterizing and cataloging rfb operon fragmentation patterns, we determined that the insertion of ‘foreign DNA’ from other bacteria, mainly Bacteroides, could explain operon fragmentation as observed in P. distasonis (supernumerary minioperon fragmentation), which was used together with Alistipes spp. as model bacteria for hypothesis testing.

Intriguingly, the presence of Bacteroides ‘foreign DNA’ insertions between antigenic operon genes (rfb, fim), but not essential ribosomal operons (rrn), implies that DNA insertions/operon damage favors selection if effects allow bacterial survival. Indeed, previously observed patterns of operon disruption in Bacteroides spp. have been linked to functional themes related to niche-habitat survival (37, 38), suggesting a similar phenomenon may occur across rfb operons in Bacteroidota. Furthermore, prior literature supports that, in addition to reductions/loss of the O-antigen (39, 40), rfb gene mutations influence bacterial survival (41) and bacteriophage infection (42). While more research is needed to elucidate how rfb gene dosage and structure influence LPS and/or other cellular KEGG ontology maps and functions in Bacteroidota, our analyses demonstrated the lack of O-antigen production by P. distasonis under different growth conditions and the lower TNF-alpha production induced by CavFT Bacteroidota isolated from CD patients in our laboratory (14, 15), or the lack of induction of peritonitis, which contrast reports of severe peritonitis due to B. thetaiotaomicron or B. fragilis, which are commonly seen in immunocompromised individuals (43–46).

Of evolutionary interest, several Bacteroides, including the bacterium B. thetaiotaomicron CL15T119C52 (human/feces/2018) were remarkably noted to cluster with P. distasonis CavFT strains (CD patients/2019) based on conserved minioperons (Figure 4). This suggests there is preferential DNA exchange among certain strains (namely Bacteroides as shown throughout the study, Figures 5 and 6A). Our in-silico analyses, manual annotation, and experimental observations serve as a proof-of-principle for the (primarily) Bacteroides DNA insertion mechanism of operon fragmentation and its potential impact on metagenomics. Findings provide novel insights and opportunities for diagnostics and therapeutic developments, especially considering that the most remarkable findings, such as the distancing of the rfbFGC->rfbA minioperons, involve bacteria isolated from chronic inflammatory microenvironments in CD patients. Our study for the first time examines and reports the genomic features of CavFTs in context with other members of the phylum, also isolated from CavFTs, which could evolve and adapt into lineages that may survive on/inside micro-niches in the inflamed gut wall (23).

In conclusion, our findings highlight that operon fragmentation provides novel mechanistic insights for commensal adaptation and metagenomic applications. An improved understanding of Bacteroidota rfb operons can provide valuable insights into bacterial genetics and their role in human health, as well as help refine experimental strategies for studying host-pathogen interactions. Future studies on these interactions or disease causality and operon integrity would benefit from combining bacterial isolation with genomic and transcriptomic sequencing to assess KEGG-pathways functionality.

Materials and methods

Genome Databases and Data Collection:

Genome wide genetic analyses for the rfb operon were conducted on publicly available datasets and on reference strains sequenced in our laboratory that we isolated from intramural cavernous lesions in the damaged bowel of Crohn’s disease patients as previously reported (5, 23). Only complete reference genomes of selected strains of human derived Enterobacteriaceae (e.g., E. coli K12, as reference for the rfb operon), selected strains for representative genera of the Bacteroidota phylum, all available reference strains for all species within the Alistipes and Parabacteroides, and all available strains for the Parabacteroides distasonis species were used in this study. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank and the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC) were accessed for bacterial genomic data. Data collected from each genome includes accession number, genome length, rfb gene copy number, nucleotide sequence, location, and direction within the genome. All results of the rfb gene query were manually verified using NCBI annotated graphical portals. Additional data was collected to find the closest homolog of conserved minioperons in P. distasonis; We used the previously obtained FASTA sequences of P. distasonis rfb minioperons as input queries in the nucleotide Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) using default settings under the nr/nt database, and BLAST hit result data and rfb gene sequence data for matching organisms from homologue queries were subsequently collected.

Visualization of rfb gene dosage and location:

The rfb genes for each genome were graphed (using gene coordinates) along a linear axis representing each bacterial genome to visualize the respective rfb operon distribution pattern in each bacterium. Rfb gene and minioperon/operon copy numbers for each genome were used to generate heatmaps demonstrating relative rfb gene dosages. Heatmaps for rfb gene dosages in P. distasonis strains were created using ClustVis (47) and a summary heatmap of rfb gene dosages for all genomes was generated with the web tool Morpheus (https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus).

Homology Analyses:

Sequences of recurring doublets; rfbCB(++) and rfbBC(−−), and of recurring triplets; rfbACD(+++), rfbDCA(−−−), rfbFGC(+++), and rfbCGF(−−−), were collected and aligned with both their respective doublets/triplets in Parabacteroides genomes as well as their respective reverse complements. In Alistipes spp., sequences of its rfbACDB(++++)/BDCA(−−−−) operons were aligned to determine homologies at the species level. Of note, no consistent patterns of minioperons were observed in the selected Bacteroides or Prevotella spp., thus no analyses could be performed to determine their respective homologies. Sequence homology was performed using the Sequence Identity and Similarity (SIAS) tool (http://imed.med.ucm.es/Tools/sias.html).

Global rfb operon profiling system (GOPS) design:

DNA sequences for each rfb gene in complete P. distasonis strain genomes were collected and aligned respectively (e.g., rfbB gene alignment, rfbC gene alignment, etc.) in CLC Genomic Workbench (commercially available). Following our previously developed rfbA-typing protocol (3), rfb-gene-types were designated for each rfb gene alignment. The aggregate results of the copy number(s) and rfb-type(s) for each genome were used to construct an example rfb operon profiling system, utilizing the nomenclature system previously proposed for rfbA-type reporting in Bacteroidota (3).

Intergene and rfb loci statistics:

The linear distance between each rfb gene was determined by calculating the number of base pairs in between consecutive genes in each genome. Rfb loci were counted in each genome, where a locus was determined to be a discrete location of either a single rfb gene or a cluster of contiguous rfb genes (operons/minioperons). Statistical analyses were performed to determine if rfb intergene linear distances and number of rfb gene loci differed significantly between the genera and phyla examined. The range and variance of rfb intergene distances was also determined at the genus and species level for Parabacteroides and Alistipes. Prior to statistical analysis, rfb intergene linear distance data was log transformed. Transformed rfb intergene linear distances and rfb gene loci data were analyzed using Brown-Forsythe ANOVA and Welch’s ANOVA to determine if statistically significant differences existed between the respective mean values of these data for Enterobacteriaceae, Parabacteroides, Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Alistipes.

Construction of phylogenetic trees:

The phylogenetic tree of whole genomes was made by Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC), under the default setting for codon tree (which uses 100 amino acids) and nucleotide sequences from BV-BRC’s global Protein Families to build an alignment and then generate a tree based on the differences within those selected sequences. For the phylogeny of rfb gene clusters (operons and minioperons), the nucleotide FASTA sequences encoding the rfb operons and minioperons were downloaded from NCBI database. The multiple sequence alignments of all nucleotide sequences were performed using the clustal omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) which was used for the construction of phylogenetic trees with the maximum likelihood methods for evolutionary analysis by using Webserver IQ-Tree (http://iqtree.cibiv.univie.ac.at/) under default parameters of ultrafast bootstrap. The phylogenetic trees with branches were built with iTOL (https://itol.embl.de/).

Primer design for amplification of the Alistipes spp. rfbBDCA/ACDB operon:

Primer design was conducted by identifying left and right flanking regions of the Alistipes spp. rfbBDCA/ACDB operon alignment of which were whole (i.e., no gaps or deletions) throughout all sequences. Then, from the corresponding regions of the rfbBDCA/ACDB operon sequence alignment consensus sequence, left and right flanks of approximately 20 base pair sequences were selected and entered into the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) to confirm accuracy in identifying Alistipes spp. utilized in this study.

Random sequences.

Random generation of genomes and the random shuffling of complete genomes were conducted using Sequence Manipulation Suite software (https://www.bioinformatics.org/sms2/shuffle_dna.html) with parameters that matched the %GC content of relevant and selected species, including 43% GC content to mimic Bacteroides genomes (B. thetaiotaomicron CL15T119C52: 43.07%, B. fragilis DCMOUH0085B: 43.61%, B. ovatus F-12: 41.98%, B. vulgatus NCTC10583: 42.03%, and B. dorei MGYG-HGUT-02478: 42.04% for an average of 42.55%).

Calculation of the gene combination of rfb minioperons:

For the bacterial genomes used in this study, the number of potential rfb minioperon combinations for each bacterium was determined by calculating the sum of the permutations of these minioperon gene combinations.

LPS Extraction and Glycoprotein Staining:

P. distasonis and E. coli were cultured in five different conditions (BHI+ 5% Yeast Extract, 50% BHI Broth, BHI Broth+5% Yeast Extract with normal person heat-killed feces, BHI+ 5% Yeast Extract with 4% bile and 50% BHI Broth with CD patient heat-killed feces) and centrifuged at 2000g for 10 minutes. The supernatant was decanted and the masses of the pellets were obtained. The LPS was extracted by LPS extraction kit (Sigma Aldrich Catalogue Number: MAK339) using the manufacturer’s instructions. In short, the cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer at a ratio of 100 μL of buffer for every 10 mg of cell pellet. The bacterial cells were lysed using a MP Fast-Prep 24 Homogenizer, using 4 rounds of shaking at 4 m/s for a duration of 20 seconds. The lysed pellets were then centrifuged at 10000g for 5 minutes to sediment the cell debris. The supernatant containing LPS was collected in a separate tube, to which proteinase K was added for a final concentration of 0.01 mg proteinase K/ml. The solution was heated to 60°C and held for 60 minutes. Following this, the solution was centrifuged at 10000g for 5 minutes, and the supernatant containing the free LPS was collected. The LPS extracts were loaded into a NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris Gel (NP0335BOX) along with commercially available LPS (Sigma) derived from E. coli, as well as a pre-stained protein ladder. The gel bands were fixed by incubating the gel in 50% Methanol for 30 minutes at room temperature. The gel was stained using a commercially available Pierce™ Glycoprotein Staining Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the gel was then immersed in a 3% acetic acid solution and incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature. The solution was removed and replaced with fresh acetic acid for another 10 minutes. The gel was then submerged in the oxidizing solution and incubated for 15 minutes with agitation using an orbital shaker. The gel was washed three times with 3% acetic acid for minutes. The gel was then transferred to the glycoprotein staining solution and incubated for 15 minutes on an orbital shaker.

TNF-α Stimulation Assay in RAW 264.7 cells:

The RAW 264.7 cells were flushed and cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM)) and supplemented with 10% FCS, NEAA, glutamax, penicillin–streptomycin. Cells were plated for experiments after 6 days. Cells were plated at 4 × 104 cells per well of a 96-well plate, and all cell lines were seeded 16 hours prior to challenging. The bacteria were cultured, and pellets were resuspended in PBS. Each pellet was heat killed by placing in a heating block for 30 min at 95°C. To normalize the concentrations of each bacterial suspension, the OD600 value was taken. The different dilutions (1:1, 1:5, 1:25 and 1:125 dilution) of the heat killed bacterial extract were added to the RAW 264.7 cells, then the medium was collected after 18 h for testing by TNF enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Peritonitis model.

To quantify the impact of bacteria on the ability to trigger inflammation in vivo, we conducted studies with mice using a peritonitis model. Using fresh anaerobic bacterial preparations (10^8 CFU/mL), each animal received an intraperitoneal injection of selected bacteria and underwent continuous monitoring for 24h prior to being euthanized. Real time mobility in the cage measured with subcutaneous RFID tags, response to stimuli, body temperature, mortality, and bacterial viability in the peritoneal fluid were measured as main outcomes.

Statistics.

Data analysis was conducted using parametric and non-parametric statistics using parametric or non-parametric methods (e.g., student T-tests, ANOVAs) using the software STATA (v17), R, and GraphPad, which was used primarily to make bar plots or boxplot illustrations where significance is represented as asterisks based on the level of significance which was held at p<0.05(*), <0.001(**) and <0.0001(***). Stata functions were used to assess multimodality (minioperon types observed vs. simulated random) as previously reported in our laboratory (48). Together, data analysis represents over 636 analytical submissions made to the various bioinformatic resources described in this study.

Assessing operon fragmentation.

Using the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC; Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center) as the data source and genome alignment tool, genomic homologies were first assessed between P. distasonis and representative members of Bacteroides, Alistipes, and Escherichia, respectively, to test the hypothesis that genomic insertions were not from random sources but rather derived primarily from Bacteroides. We then identified unique rfb order series that were present across seemingly unrelated genomes (chronologically, geographically), including the series ‘rfbFGC ➔ rfbA’, wherein a triplet (rfbFGC) is followed by a nearby separated singlet gene (rfbA). Focused on Bacteroides and P. distasonis as recipient genomes, including CavFT strains, we examined inter-minioperon DNA sequences (e.g., between rfbFGC and rfbA) to conduct genome-wide arrangement analysis between such regions in P. distasonis and the genomes of B. thetaiotaomicron, other Bacteroidota, and E. coli to quantify their genus-dependent potential as donors of ‘foreign DNA’. Intra-phylum genome homologies of Enterobacteriaceae were also measured as a referent. We assessed the genetic homologies of three inter-minioperon segments (rfbFGC ➔ rfbA, rfbCB ➔rfbD, fimCBA ➔fimE) present either completely or uniquely across three P. distasonis strains (CavFT-hAR46, CavFT-hAR56, and CL11T00C22). Whole genome homologies were then compared to inter-minioperon genetic homologies. Next, selectivity of operon fragmentation was assessed in the P. distasonis ATCC 8503 reference genome, for which 7 16S rRNA loci were annotated in BV-BRC. These 7 loci were compared with 20 randomly generated loci of similar size to compare the amount of B. thetaiotaomicron DNA in or near each locus.

Genome fragmentation alignment analysis.

We quantified and plotted the distribution of DNA fragments detected by genome alignment ranked by fragment number (x-axis) vs. the size of each fragment (y-axis) across 16 genomes (4 Escherichia spp., 5 Alistipes spp., and 7 Bacteroides spp.) individually aligned to P. distasonis in BV-BRC.

Assessment of fragmentation in other antigenic (fimbriae, fim) operons.

Recently, researchers investigating the antigenic cell surface structure of P. distasonis identified fimbriae (fim) operon genes in several strains (34), though there was again ample heterogeneity in the type and quantity of these genes amongst the strains investigated, suggesting operon fragmentation could also occur for other functions. For this analysis we used the P. distasonis CL11T00C22 strain genome as it contains the most complete set of identified fim operon genes.

Metagenomics of Bacteroidota.

Whole genome sequences of select Bacteroidota (and Escherichia coli K-12 as referent) downloaded from NCBI were split into 250bp sequences using FASTA-splitting software (https://www.bioinformatics.org/sms2/split_fasta.html) to approximate the range of in vivo DNA samples which are commonly used for shotgun sequencing (49). The sequences for each respective genome were then used as inputs for taxonomic classification in BV-BRC as well as for assessment of matching protein sequences using BLASTX.

We validated our hypothesis using principles of genomic and metagenomics data analysis using well-referenced and established methods that are readily accessible over the internet to the scientific community (50–52). We used the Bacteria and Virus Bioinformatics Resources Center (BV-BRC) web server as it integrates multiple analysis steps into single workflows (52), by combining the resources from the former Pathosystems Resource Integration Center (PATRIC), the Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR) and the Influenza Research Database (IRD) (50, 51). Analysis tools include pipelines for read assembly, open reading frame prediction, and annotation with BLAST, and GO pathways classifiers. The BV-BRC web server is an easy-to-use web-based interface for processing, annotation, and visualization of genomic and functional metagenomics sequencing data, designed to facilitate the analysis of data by non-bioinformaticians (52). Metagenomics results derived from Kraken2, are visualized via Krona as a dynamic online feature for hierarchical data and prediction confidence (35). The BV-BRC online setting provides scientists a fast open-source strategy to analyze raw sequences and generate complex comparative analysis by selecting reference genomes or genomes uploaded by the user to an academic account. Genome arrangement analysis was conducted using the tool ‘Comparative Analysis tools’ available in beta version. Sequence and genome coordinate data can be examined as summary tables or visually through colored interactive arrangement plots. BV-BRC facilitates effortless inspection of gene function, clustering, and distribution. The webserver is available at https://www.bv-brc.org/.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements.

This project was supported by 1) NIH grant R21 DK118373 to A.R.-P., entitled “Identification of pathogenic bacteria in Crohn’s disease.” and 2) Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation Student Research Fellowship Award #932611 to Nicholas Bank, entitled “Molecular Immunology of Parabacteroides distasonis in Crohn’s Disease and Role of Strain Diversity in Macrophage Activation. Partial support earlier originated for A.R.-P. from a career development award and recently from a Litwin Pioneers award from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Parker BJ, Wearsch PA, Veloo ACM, Rodriguez-Palacios A. The Genus Alistipes: Gut Bacteria With Emerging Implications to Inflammation, Cancer, and Mental Health. Front Immunol. 2020;11:906. Epub 20200609. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ezeji J, Sarikonda D, Hopperton A, Erkkila H, Cohen D, Martinez S, et al. Parabacteroides distasonis: intriguing aerotolerant gut anaerobe with emerging antimicrobial resistance and pathogenic and probiotic roles in human health. GUT MICROBES2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Bank NC, Singh V, Rodriguez-Palacios A. Classification of Parabacteroides distasonis and other Bacteroidetes using O-antigen virulence gene: RfbA-Typing and hypothesis for pathogenic vs. probiotic strain differentiation. Gut Microbes. 2022;14(1):1997293. Epub 2022/01/30. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1997293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nayfach S, Pollard KS. Average genome size estimation improves comparative metagenomics and sheds light on the functional ecology of the human microbiome. Genome Biol. 2015;16(1):51. Epub 20150325. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0611-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang F, Kumar A, Davenport KW, Kelliher JM, Ezeji JC, Good CE, et al. Complete Genome Sequence of a Parabacteroides distasonis Strain (CavFT hAR46) Isolated from a Gut Wall-Cavitating Microlesion in a Patient with Severe Crohn’s Disease. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2019;8(36). Epub 2019/09/05. doi: 10.1128/MRA.00585-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Lorenzo F, Pither MD, Martufi M, Scarinci I, Guzmán-Caldentey J, Łakomiec E, et al. Pairing Bacteroides vulgatus LPS Structure with Its Immunomodulatory Effects on Human Cellular Models. ACS Central Science. 2020;6(9):1602–16. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vatanen T, Kostic AD, d’Hennezel E, Siljander H, Franzosa EA, Yassour M, et al. Variation in Microbiome LPS Immunogenicity Contributes to Autoimmunity in Humans. Cell. 2016;165(4):842–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindberg AA, Weintraub A, Zähringer U, Rietschel ET. Structure-activity relationships in lipopolysaccharides of Bacteroides fragilis. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12 Suppl 2:S133–41. Epub 1990/01/01. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.supplement_2.s133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajilić-Stojanović M, de Vos WM. The first 1000 cultured species of the human gastrointestinal microbiota. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2014;38(5):996–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eggerth AH, Gagnon BH. The Bacteroides of Human Feces. J Bacteriol. 1933;25(4):389–413. Epub 1933/04/01. doi: 10.1128/jb.25.4.389-413.1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chow J, Mazmanian SK. A pathobiont of the microbiota balances host colonization and intestinal inflammation. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7(4):265–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Awadel-Kariem FM, Patel P, Kapoor J, Brazier JS, Goldstein EJ. First report of Parabacteroides goldsteinii bacteraemia in a patient with complicated intra-abdominal infection. Anaerobe. 2010;16(3):223–5. Epub 20100206. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henthorne JC, Thompson L, Beaver DC. Gram-Negative Bacilli of the Genus Bacteroides. J Bacteriol. 1936;31(3):255–74. doi: 10.1128/jb.31.3.255-274.1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun H, Guo Y, Wang H, Yin A, Hu J, Yuan T, et al. Gut commensal Parabacteroides distasonis alleviates inflammatory arthritis. Gut. England: © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2023. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by BMJ.; 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Lai H-C, Lin T-L, Chen T-W, Kuo Y-L, Chang C-J, Wu T-R, et al. Gut microbiota modulates COPD pathogenesis: role of anti-inflammatory Parabacteroides goldsteinii lipopolysaccharide. Gut. 2022;71(2):309. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Honda K, Littman DR. The microbiome in infectious disease and inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:759–95. Epub 20120106. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kverka M, Zakostelska Z, Klimesova K, Sokol D, Hudcovic T, Hrncir T, et al. Oral administration of Parabacteroides distasonis antigens attenuates experimental murine colitis through modulation of immunity and microbiota composition. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;163(2):250–9. Epub 2010/11/19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04286.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly D, Conway S, Aminov R. Commensal gut bacteria: mechanisms of immune modulation. Trends in Immunology. 2005;26(6):326–33. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly D, Campbell JI, King TP, Grant G, Jansson EA, Coutts AG, et al. Commensal anaerobic gut bacteria attenuate inflammation by regulating nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of PPAR-γ and RelA. Nature immunology. 2004;5(1):104–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Lorenzo F, De Castro C, Silipo A, Molinaro A. Lipopolysaccharide structures of Gram-negative populations in the gut microbiota and effects on host interactions. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2019;43(3):257–72. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuz002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.d’Hennezel E, Abubucker S, Murphy Leon O, Cullen Thomas W. Total Lipopolysaccharide from the Human Gut Microbiome Silences Toll-Like Receptor Signaling. mSystems. 2017;2(6):e00046–17. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00046-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duvallet C, Gibbons SM, Gurry T, Irizarry RA, Alm EJ. Meta-analysis of gut microbiome studies identifies disease-specific and shared responses. Nature Communications. 2017;8(1):1784. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01973-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh V, Rodriguez-Palacios A. Genomics of Parabacteroides distasonis from Gut-Wall Cavitating Microlesions Suggest Bacteroides Resemblance and Lineage Adaptation in Crohn’s Disease. [Manuscript submitted for publication]2023.

- 24.Koh GY, Kane A, Lee K, Xu Q, Wu X, Roper J, et al. Parabacteroides distasonis attenuates toll-like receptor 4 signaling and Akt activation and blocks colon tumor formation in high-fat diet-fed azoxymethane-treated mice. Int J Cancer. 2018;143(7):1797–805. Epub 2018/04/27. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobson AN, Choudhury BP, Fischbach MA. The biosynthesis of lipooligosaccharide from Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. MBio. 2018;9(2):e02289–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D’Souza JM, Samuel GN, Reeves PR. Evolutionary origins and sequence of the Escherichia coli O4 O-antigen gene cluster ⋆. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2005;244(1):27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bäckhed F, Normark S, Schweda EKH, Oscarson S, Richter-Dahlfors A. Structural requirements for TLR4-mediated LPS signalling: a biological role for LPS modifications. Microbes and Infection. 2003;5(12):1057–63. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(03)00207-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rocha EPC. The Organization of the Bacterial Genome. Annual Review of Genetics. 2008;42(1):211–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taboada B, Estrada K, Ciria R, Merino E. Operon-mapper: a web server for precise operon identification in bacterial and archaeal genomes. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(23):4118–20. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okuda S, Yoshizawa AC. ODB: a database for operon organizations, 2011 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D552–5. Epub 20101104. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taboada B, Ciria R, Martinez-Guerrero CE, Merino E. ProOpDB: Prokaryotic Operon DataBase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D627–31. Epub 20111116. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mao X, Ma Q, Zhou C, Chen X, Zhang H, Yang J, et al. DOOR 2.0: presenting operons and their functions through dynamic and integrated views. Nucleic Acids Research. 2013;42(D1):D654–D9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Groussin M, Poyet M, Sistiaga A, Kearney SM, Moniz K, Noel M, et al. Elevated rates of horizontal gene transfer in the industrialized human microbiome. Cell. 2021;184(8):2053–67.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chamarande J, Cunat L, Alauzet C, Cailliez-Grimal C. In Silico Study of Cell Surface Structures of Parabacteroides distasonis Involved in Its Maintenance within the Gut Microbiota. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23(16):9411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ondov BD, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. Interactive metagenomic visualization in a Web browser. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:385. Epub 20110930. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Kawashima S, Nakaya A. The KEGG databases at GenomeNet. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):42–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koropatkin NM, Cameron EA, Martens EC. How glycan metabolism shapes the human gut microbiota. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2012;10(5):323–35. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martens EC, Koropatkin NM, Smith TJ, Gordon JI. Complex Glycan Catabolism by the Human Gut Microbiota: The Bacteroidetes Sus-like Paradigm *. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(37):24673–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.022848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klena JD, Schnaitman CA. Function of the rfb gene cluster and the rfe gene in the synthesis of O antigen by Shigella dysenteriae 1. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9(2):393–402. Epub 1993/07/01. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu D, Reeves PR. Escherichia coli K12 regains its O antigen. Microbiology (Reading). 1994;140 ( Pt 1):49–57. Epub 1994/01/01. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-1-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boels IC, Beerthuyzen MM, Kosters MH, Van Kaauwen MP, Kleerebezem M, De Vos WM. Identification and functional characterization of the Lactococcus lactis rfb operon, required for dTDP-rhamnose Biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(5):1239–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liang J, Li X, Zha T, Chen Y, Hao H, Liu C, et al. DTDP-rhamnosyl transferase RfbF, is a newfound receptor-related regulatory protein for phage phiYe-F10 specific for Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:3. Scientific Reports. 2016;6(1):22905. doi: 10.1038/srep22905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chao CM, Liu WL, Lai CC. Peritoneal dialysis peritonitis caused by Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Perit Dial Int. 33. United States: 2013. p. 711–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Faur D, García-Méndez I, Martín-Alemany N, Vallès-Prats M. Mono-bacterial peritonitis caused by Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron in a patient on peritoneal dialysis. Nefrología (English Edition). 2012;32(5):694. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2012.Jun.11568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chao CT, Lee SY, Yang WS, Chen HW, Fang CC, Yen CJ, et al. Peritoneal dialysis peritonitis by anaerobic pathogens: a retrospective case series. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:111. Epub 20130524. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montravers P, Gauzit R, Muller C, Marmuse JP, Fichelle A, Desmonts JM. Emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in cases of peritonitis after intraabdominal surgery affects the efficacy of empirical antimicrobial therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23(3):486–94. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.3.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Metsalu T, Vilo J. ClustVis: a web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;43(W1):W566–W70. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Basson AR, Cominelli F, Rodriguez-Palacios A. ‘Statistical Irreproducibility’ Does Not Improve with Larger Sample Size: How to Quantify and Address Disease Data Multimodality in Human and Animal Research. J Pers Med. 2021;11(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alneberg J, Karlsson CMG, Divne A-M, Bergin C, Homa F, Lindh MV, et al. Genomes from uncultivated prokaryotes: a comparison of metagenome-assembled and single-amplified genomes. Microbiome. 2018;6(1):173. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0550-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parrello B, Butler R, Chlenski P, Pusch GD, Overbeek R. Supervised extraction of near-complete genomes from metagenomic samples: A new service in PATRIC. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):e0250092. Epub 20210415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davis JJ, Wattam AR, Aziz RK, Brettin T, Butler R, Butler RM, et al. The PATRIC Bioinformatics Resource Center: expanding data and analysis capabilities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(D1):D606–d12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Olson RD, Assaf R, Brettin T, Conrad N, Cucinell C, Davis JJ, et al. Introducing the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC): a resource combining PATRIC, IRD and ViPR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D678–d89. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.