Abstract

Genetic association studies have linked ATP10A and closely related type IV P-type ATPases (P4-ATPases) to insulin resistance and vascular complications, such as atherosclerosis. ATP10A translocates phosphatidylcholine and glucosylceramide across cell membranes, and these lipids or their metabolites play important roles in signal transduction pathways regulating metabolism. However, the influence of ATP10A on lipid metabolism in mice has not been explored. Here, we generated gene-specific Atp10A knockout mice and show that Atp10A−/− mice fed a high-fat diet did not gain excess weight relative to wild-type littermates. However, Atp10A−/− mice displayed female-specific dyslipidemia characterized by elevated plasma triglycerides, free fatty acids and cholesterol, as well as altered VLDL and HDL properties. We also observed increased circulating levels of several sphingolipid species along with reduced levels of eicosanoids and bile acids. The Atp10A−/− mice also displayed hepatic insulin resistance without perturbations to whole-body glucose homeostasis. Thus, ATP10A has a sex-specific role in regulating plasma lipid composition and maintaining hepatic liver insulin sensitivity in mice.

Introduction

The metabolic syndrome is a complex condition that affects 33% of Americans (1) and on a global scale, over 1 billion people (2). This syndrome is characterized by abdominal obesity, insulin resistance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, and an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) (3). Commonly found variants in ATP10A have been linked to increased risk of insulin resistance (4) and variants within a related gene, ATP10D, have been linked to increased atherosclerosis risk (5). ATP10A and ATP10D are P4-ATPases, also known as lipid flippases, that translocate lipids from the exoplasmic or luminal leaflets to cytosolic leaflets of cell membranes. This creates an asymmetric distribution of lipids within membranes that has several implications for the cell (6), including in apoptosis (7), vesicular trafficking (8), and signal transduction (9).

Interestingly, most of the 14 human P4-ATPases have established roles in disease, such as in severe neurological disorders and intrahepatic cholestasis (10). These enzymes transport specific lipid substrates, which are closely related to their cellular and physiological functions. ATP10A flips phosphatidylcholine (PC) (11) and glucosylceramide (GlcCer) (12). PC is the most abundant phospholipid in cellular membranes (13). Metabolites of PC, such as lysophosphatidylcholine (LysoPC), arachidonic acid (AA), and eicosanoids produced from AA, play important roles in modulating inflammation and various disease states (14–18). GlcCer is a bioactive lipid that can affect insulin signaling and energy homeostasis (19), as well as inflammation (20). Inhibiting GlcCer synthase enhances insulin sensitivity (21) and protects against cardiac hypertrophy (22). GlcCer can be broken down into ceramide or built up into gangliosides, which also have established roles in metabolism (23–25).

Previous reports suggested a role for murine ATP10A in diet-induced obesity, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia and these phenotypes were more severe in female mice (26,27). However, the mouse model used in these studies contained a large, irradiation-induced chromosomal deletion (p23DFiOD) encompassing the pink-eyed dilution (p) locus, Atp10A (previously named Atp10C) and several other genes. End-point mapping of a nested deletion series implicated Atp10A in the metabolic defects but whether an Atp10A-specific knockout is sufficient to cause insulin resistance has not been determined. Homozygosity of the irradiation-induced deletion resulted in embryonic lethality and heterozygous mice that inherited the chromosomal deletion maternally displayed more severe metabolic phenotypes compared to those who inherited the deletion paternally. This observation suggested that the Atp10A locus was imprinted to suppress expression of the paternal allele, however several studies failed to detect imprinted expression of the ATP10A gene (28–30). It appears that ATP10A expression pattern is complex and dependent on multiple factors including gender, genetic background, and tissue type.

Although correlations between ATP10A deficiency and insulin resistance, diet-induced obesity, and glucose uptake (31) have been reported, it is unclear whether this flippase plays a causative role in these processes. Here, we generated a gene-specific deletion and tested the impact of Atp10A deficiency in mice during high fat diet (HFD) feeding. Atp10A deficient mice display female-specific diet-induced dyslipidemia, broad changes to lipid metabolism, and disruptions in liver insulin signaling.

Results

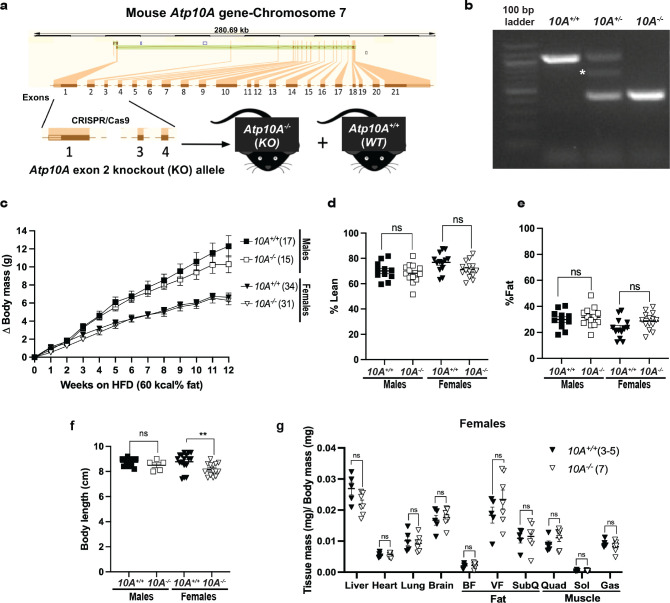

Atp10A deficiency does not affect body composition after high fat diet feeding.

To develop the Atp10A−/− mice, we created a gene-specific knockout allele of Atp10A in the C57BL/6J background using CRISPR/Cas9 guide RNA sequences targeted to regions flanking exon 2 (Figure 1a) and confirmed the genotype of the mice via PCR (Figure 1b). To test the potential impact of Atp10A on weight gain, we placed male and female WT (10A+/+) and KO (10A−/−) mice on a HFD for 12 weeks. We found that there was no significant difference in weight gain in males (P-value for 12th week on HFD: 0.3154) or females (P-value for 12th week on HFD: >0.9999) based on genotype (Figure 1c). We next examined body composition and size and found that male and female mice did not display a difference in % lean mass (Figure 1d) or % fat mass (Figure 1e) based on genotype. Male mice also did not exhibit changes in body length based on genotype, however, female Atp10A−/− mice had shorter body lengths compared to Atp10A+/+ littermates (Figure 1f). For the female mice, no significant difference was observed in daily (sum of light and dark hours) activity, food intake, or energy expenditure based on genotype. However, the Atp10A−/− female mice displayed reduced food intake and a negative energy balance during light hours compared to WT mice (Supplemental table 1). Additionally, we did not observe any changes in tissue mass (Figure 1g) in female mice based on genotype.

Figure 1. Atp10A deletion does not alter the development of diet-induced obesity after 12 weeks of HFD.

(a) Graphic illustrating how CRISPR/cas9 was used to delete exon 2 in the mouse Atp10A to create the Atp10A−/− (KO) mouse line. (b) PCR genotyping results from Atp10A+/+ (10A+/+) (1067 base pairs (bp)), Atp10A+/− (10A+/−), and Atp10A−/− (10A−/−) (460 bp) mouse tail clips. The white asterisk indicates a product at ~700 bp that appears in all 10A+/− samples due to hybridization of sequences from the 10A+/+ and 10A−/− PCR products. (c) Weight gain of male and female Atp10A+/+ (10A+/+) and Atp10A−/− (10A−/−) mice over the course of 12 weeks on a HFD (60 kcal% fat, Ad lib feeding), (Male: 10A+/+ n=17, 10A−/− n=15; Female: 10A+/+ n=34, 10A−/− n=31). (d) Lean and (e) fat body mass were normalized to the combined sum of lean and fat mass to calculate % Lean and % Fat mass (Male: 10A+/+ n=11,10A−/− n=13; Female:10A+/+ n=13,10A−/− n=14). (f) Body length of mice was measured after CO2 sacrifice, **P=0.0094. (Male: 10A+/+ n=11, 10A−/− n=5; Female: 10A+/+ n=17, 10A−/− n=14). (g)The wet mass of tissue was measured after removal from female mice on the 12th week on the HFD. Tissue mass is normalized to body mass (10A+/+ n=3–5,10A−/− n=7). P value by (a) 2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison or (d-g) unpaired t-tests.

We also measured weight gain, body composition, and body length in female mice on normal chow; and found no significant differences based on genotype (Supplemental Figure 1a–d). Altogether, these results indicate that Atp10A deficiency does not alter the development of diet-induced obesity under the conditions tested.

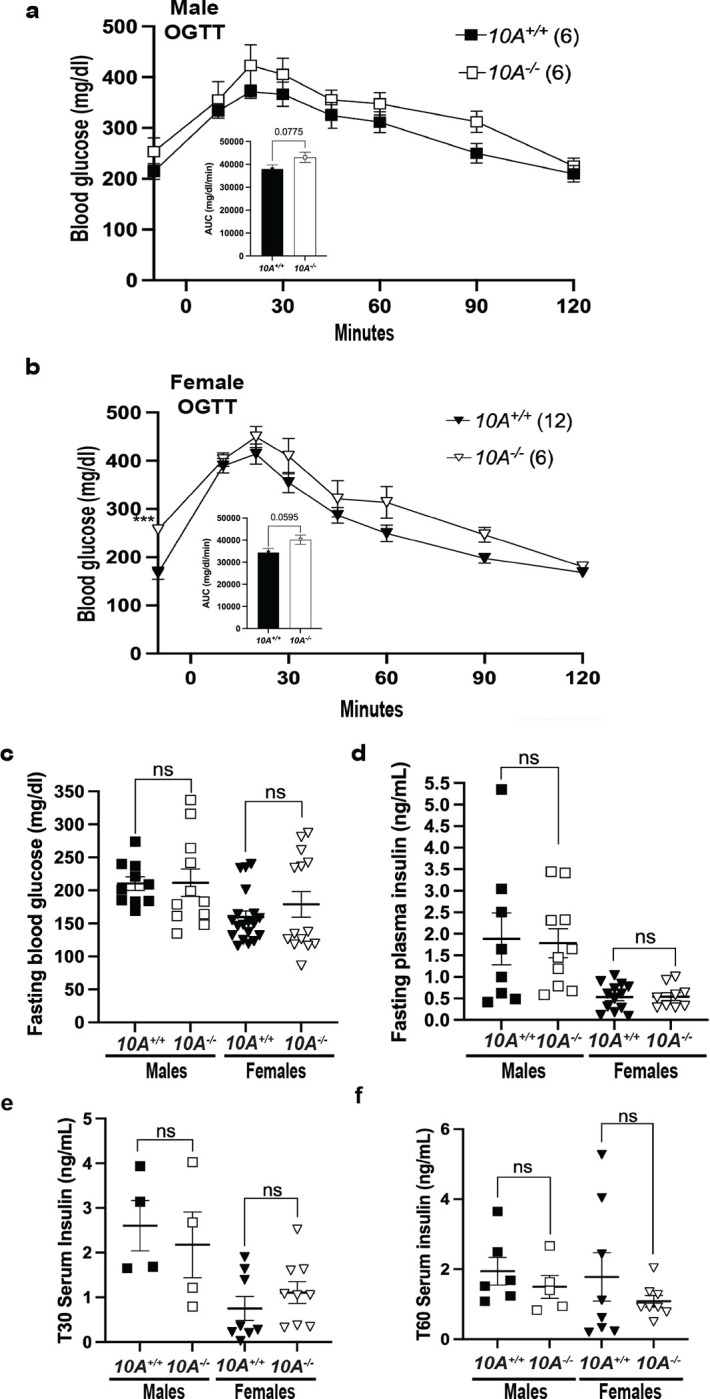

Atp10A deficiency does not affect whole-body glucose homeostasis in female mice.

Studies using the p23DFiOD deletion encompassing Atp10A, found that these mice were hyperinsulinemic, insulin resistant, and hyperglycemic (26,27). To specifically assess the influence of Atp10A on glucose homeostasis, we fasted WT and Atp10A−/− (exon 2 deletion) mice for 5 hours and performed an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) as well as measured fasting levels of glucose and insulin. During the OGTT, male Atp10A deficient mice did not exhibit differences in glucose excursion after the glucose bolus (Figure 2a) compared to WT mice. However, the female Atp10A−/− mice exhibited significantly elevated fasting blood glucose after a 5 hour fast (points before time 0 during the OGTT, Figure 2b) and trended toward exhibiting an elevated glucose excursion compared to the female WT mice, represented by the elevated area under the curve (AUC) (Figure 2b, inset). While the elevated fasting blood glucose was significant for the number of female mutant mice tested (n=6), the study was underpowered. Therefore, fasting blood glucose was measured from additional mice and we found no significant difference in fasting blood glucose in male or female mice based on genotype (Figure 2c). The reason for the variation in fasting blood glucose seen in the females is unclear, but could be due to experimental stress for the animals with the elevated fasting blood glucose There was also no significant difference in fasting plasma insulin (Figure 2d) or insulin levels at 30 minutes (T30, Figure 2e), or 60 minutes (T60, Figure 2f) after the glucose bolus (during the OGTT) in males or females based on genotype. Additionally, normal chow fed female Atp10A−/− mice did not exhibit differences in fasting blood glucose or insulin (Supplemental Figure 1e,f) compared to WT mice. Therefore, in contrast to expectations based on prior reports, Atp10A deficiency does not appear to significantly perturb whole-body glucose homeostasis.

Figure 2. Atp10A deletion does not result in changes to glucose homeostasis after 12 weeks of HFD.

(a) Male and (b) female mice were gavaged with 20% dextrose (time 0 on the graph) after a 5-hour fast then an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was performed. The inset shows the area under the curve (AUC) of the blood glucose (mg/dl) during the OGTT, normalized to fasting blood glucose (points before time 0 on the graph), ***P=0.0003. Male: 10A+/+ n=6,10A−/− n=6; Female: 10A+/+ n=12, 10A−/− n=6). (c) Fasting blood glucose was measured from tail blood after a 5 hour fast, via a glucometer (Male: 10A+/+ n=10, 10A−/− n=11; Female: 10A+/+ n=19, 10A−/− n=14). (d) Fasting plasma insulin was measured after a 5 hour fast (Male: 10A+/+ n=8, 10A−/− n=10; Female: 10A+/+ n=13,10A−/− n=9). Insulin was measured from serum collected during the OGTT shown in Figure 2a,b at the (e) 30-minute time point (T30) and the (f) 60-minute time point (T60), (Male: C: 10A+/+ n=4, 10A−/− n=4, D: 10A+/+ n=6, 10A−/− n=5; Female: 10A+/+ n=8, 10A−/− n=6). P value by (a,b, not AUC) 2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison or (a,b (AUC), c-f) unpaired t-tests.

Maternal inheritance of the Atp10A exon 2 deletion results in changes to body length and fasting blood glucose in males.

Prior reports showed that the inheritance pattern of the p23DFiOD deletion encompassing Atp10A effected the severity of the metabolic phenotypes in heterozygous mice, specifically if the deletion was inherited maternally or paternally (26,27). We tested this phenomenon using the Atp10A exon 2 deletion mice by measuring metabolic phenotypes after high fat diet feeding, in heterozygous mice reared from 10A+/− dams × 10A+/+ sires (maternal inheritance (inh.)) or 10A+/+ dams × 10A+/− sires (paternal inh.). We found no significant difference in weight gain, body composition, or fasting plasma insulin based on the inheritance patterns of the Atp10A exon 2 deletion in males or females after 12 weeks of HFD (Supplemental Figure 2a–c, f). However, the male mice inheriting the exon 2 deletion maternally trended toward having increased weight gain, although this did not reach statistical significance (P-value for 12th week of HFD: 0.0906), shorter bodies (Supplemental Figure 2d) and elevated fasting blood glucose levels after a 5 hour fast (Supplemental Figure 2e) compared to mice that inherited the deletion paternally. Therefore, the inheritance pattern of the Atp10A exon 2 deletion does not significantly impact weight gain, body composition, and fasting plasma insulin in males or females after HFD feeding, but does have distinct effects on body length and fasting blood glucose levels in male mice.

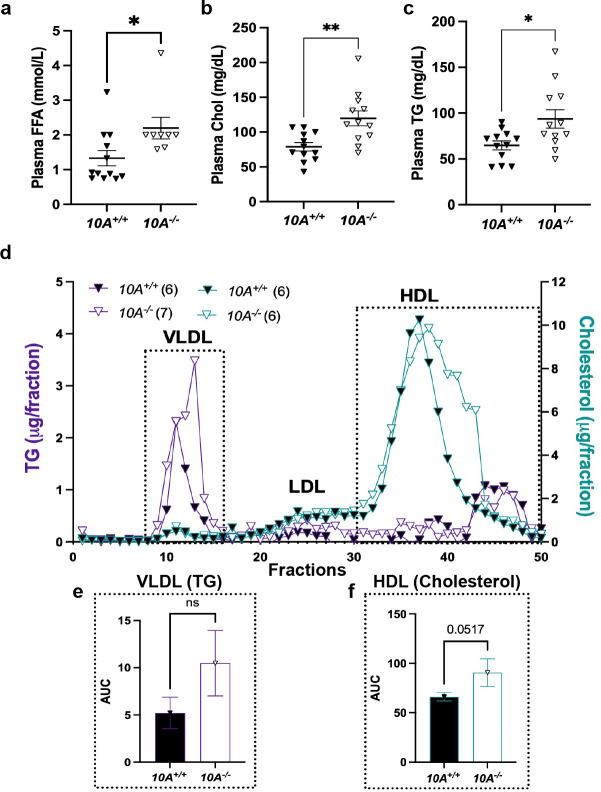

Atp10A deficiency causes diet-induced dyslipidemia in females.

To further probe the influence of Atp10A on whole-body metabolism, we measured the concentration of free fatty acids (FFA), cholesterol (chol), and triglycerides (TG) in the plasma. While the male mice showed no difference in plasma lipids based on genotype (Supplemental Figure 3a–c), the female Atp10A−/− mice display substantially elevated plasma concentrations of FFA (Figure 3a), chol (Figure 3b), and TG (Figure 3c) compared to Atp10A+/+ littermates. To further explore this female-specific dyslipidemia phenotype, we performed fast performance liquid chromatography (FPLC) on plasma to assess the relative size and lipid distribution in lipoprotein fractions (Figure 3d). We found that the Atp10A−/− mice carry most of their TG and cholesterol in smaller sized very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) particles, respectively (indicated by a shift to the right in the chromatograms). We also compared the AUC of the VLDL-TG (Figure 3e) and HDL-cholesterol (Figure 3f) fractions and found that the Atp10A−/− mice trend toward having more lipids in these fractions compared to controls, although this did not reach statistical significance. Together, these results show that Atp10A deficiency causes female-specific dyslipidemia and changes to lipoprotein metabolism after HFD feeding.

Figure 3. Atp10A deletion causes diet-induced dyslipidemia in female mice after 12 weeks of HFD.

(a-c) Free fatty acids (FFA), cholesterol (chol), and triglycerides (TG) were measured in plasma from females after a 5 hour fast or after a 5 hour fast followed by an OGTT (a, 10A+/+ n=12, 10A−/− n=9,*P=0.0320; b, 10A+/+ n=12, 10A−/− n=9, **P=0.0030; c, 10A+/+ n=12, 10A−/− n=9, *P=0.0165.) (d-f) Lipoproteins in pooled plasma from females, collected after a 5-hour fast or 5-hour fast and OGTT, were separated via FPLC. (e) Plasma TG (purple) and (f) cholesterol (blue) content were measured from the separated lipoproteins. AUC of (e) TG fractions 10–18 of VLDL and (f) cholesterol fractions 30–50 of HDL (TG:10A+/+ n=6, 10A−/− n=7, Chol:10A+/+ n=6, 10A−/− n=6). P value by unpaired t-test.

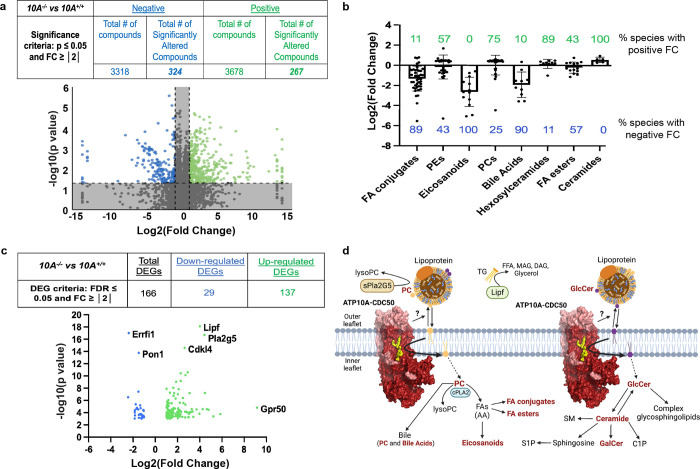

Atp10A deficiency in females causes substantial changes to the plasma lipidome and visceral fat transcriptome after HFD feeding.

To get a broader view of the dyslipidemia in the plasma of female Atp10A−/− mice, we performed mass spectrometry-based untargeted lipidomics on plasma from female Atp10A−/− and Atp10A+/+ littermates after 12 weeks on HFD after a 5-hour fast. We found that Atp10A deficiency resulted in statistically significant changes to the abundance of a large number of plasma lipid species; 591 in total, with 324 of these observed from positive ion mode and 267 from negative ion mode lipidomics (Figure 4a, Study ID ST002696, http://dx.doi.org/10.21228/M83H7N). To highlight how Atp10A deficiency altered specific classes of lipid species, we plotted the log2(Fold Change) of lipid species that were significantly changed and calculated the % of the lipid species in each group that had a positive fold change (increase in abundance, green values) versus a negative fold change (decrease in abundance, blue values) (Figure 4b). Interestingly, we saw modest increases in the abundance of ATP10A’s lipid substrates, PC and hexosylceramides (this includes GlcCer and galactosylceramide (GalCer)). Surprisingly, we observed that plasma eicosanoid, bile acid and fatty acid (FA) conjugate species were dramatically depleted in Atp10A−/− mice compared to Atp10A+/+ littermates.

Figure 4. Atp10A deletion leads to substantial perturbations in the plasma lipidome and visceral fat transcriptome in female mice on a HFD.

(a) Lipid metabolites from fasting plasma were measured by HPLC-IM-MS/MS and the data was processed via Progenesis QI. The table indicates the number of total and significantly changed lipid metabolites (compounds) observed from each ionization mode (Negative and Positive); the volcano plot illustrates the fold changes (FC) of compounds between 10A−/− vs. 10A+/+ mice, the grey shading indicates changes that did not meet the significance criteria. P-values by ANOVA. (10A+/+ n=8, 10A−/− n=8, see Supplemental Table 3 for complete information about sample size) (b) The log2(FoldChange) of lipid metabolites compared between 10A−/− vs. 10A+/+ mice are grouped by indicated categories (green and blue indicate the % of lipid species with positive and negative fold change, respectively, between 10A−/− vs. 10A+/+ mice; P values ≤ 0.1 by ANOVA). (c) Sequencing of visceral fat mRNA was performed using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000. The table provides the criteria used to calculate the number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and how many DEGs were measured; the volcano plot illustrates the DEGs (10A+/+ n=3,10A−/− n=3). (d) Schematic illustrating the metabolic pathways linking ATP10A substrates to observed changes in the plasma lipidome and visceral fat transcriptome. Lipid metabolites with significant changes due to 10A deletion from panel B are in bold red, the hexosylceramide category includes both GalCer and GlcCer. The protein products from two mRNA transcripts that were significantly upregulated in the visceral fat from 10A−/− mice (panel c), Pla2G5 and Lipf, are highlighted to show their role in lipid metabolism. Schematic created using Biorender.com. See Supplemental Table 2 for RNASeq KEGG pathway analysis. PC= phosphatidylcholine, AA=arachidonic acid, TG= triglyceride, FA=fatty acids, FFA=free fatty acids, DAG=diacylglycerol, MAG=monoacylglycerol, SM=sphingomyelin, S1P= sphingosine 1-phosphate, C1P= ceramide 1-phosphate, GalCer= galactosylceramide, GlcCer= glucosylceramide.

We further probed the influence of Atp10A on metabolism by performing RNAseq on visceral fat (Figure 4c, NCBI GenBank accession numbers: SRR24233646, SRR24233645). We found that 166 genes were differentially expressed in Atp10A−/− compared to Atp10A+/+ mice, where 29 were downregulated and 137 were upregulated. Some notable differences were substantial increases in expression of Lipf and Pla2g5, encoding a TG lipase and a secreted phospholipase A2, respectively, in Atp10A−/− mice (Figure 4c, Supplemental Table 2). Additionally, the orphan G protein-coupled receptor, GPR50, was upregulated 571-fold. This gene has been linked to circulating TG and HDL levels in humans (32), energy metabolism in mice (33), and the attenuation of inflammation and insulin signaling in 3T3-L1 adipocytes (34).

Taken together, these results indicate that ATP10A has a substantial role in lipid metabolism in female mice fed a HFD. The potential mechanistic links between the lipid transport activity of ATP10A and whole-body lipid metabolism are shown in Figure 4d. Briefly, by translocating PC and GlcCer from the outer leaflet to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane, ATP10A provides substrates to intracellular lipid metabolism enzymes for production of bioactive lipid signaling molecules while decreasing the availability of PC and GlcCer to molecules in circulation (i.e. lipoproteins, lipases) (Figure 4d). Thus, this lipid transport could affect levels of PC, GlcCer, and downstream metabolites in the intracellular space and in circulation (Figure 4b) as well as change the expression levels of lipid handling enzymes (Figure 4c).

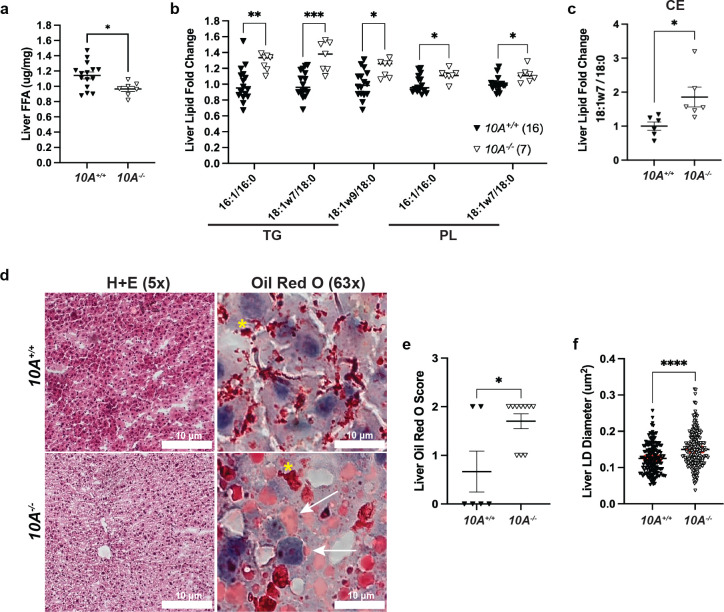

Atp10A deficiency in females results in changes to liver lipid metabolism after HFD feeding.

To further probe the impact of Atp10A deficiency on lipid metabolism, we measured levels of various lipid species in the liver. We found that female Atp10A−/− mice have less liver FFA (Figure 5a), but no significant differences in the levels of total cholesterol, cholesterol esters (CE), unesterified cholesterol, TG, phospholipids (PL), or ceramides compared to Atp10A+/+ littermates (Supplemental Figure 4a–f). Female Atp10A−/− mice also exhibit a significant increase in the abundance of monounsaturated vs. saturated species of several TG and PL species (Figure 5b) and one CE species (Figure 5c) with carbon chain lengths of 16 and/or 18. Although the total amounts of cholesterol and TG in the liver were not different based on genotype, Oil Red O stained lipid droplets (LD) from the Atp10A−/− mice were larger on average compared to Atp10A+/+ mice (Figure 5d–f). Therefore, Atp10A deficiency results in changes to the amount and saturation state of several lipid species in the liver.

Figure 5. Atp10A deletion causes changes to liver lipid metabolism in female mice after 12 weeks of HFD.

(a) FFAs were measured from flash frozen livers via gas chromatography. Livers were collected after a 5 hour fast or after a 5 hour fast followed by an OGTT. t (FFA: 10A+/+ n=15,10A−/− n=7, *P=0.0201). The saturation of liver (b) TG, PL, and (c) CE species was determined by gas chromatography. The fold change of monounsaturated vs saturated TG, PL, CE is shown, TG: **P=0.0025, ***P=0.0001, *P=0.0443, PL: *P=0.0297, *P=0.0281 (10A+/+ n=16, 10A−/− n=7). CE: *P=0.0223 (10A+/+ n=6, 10A−/− n=6). (d) Representative images of livers stained with H+E (5x) or Oil Red O (63x). The coalescence of the Oil Red O stain is indicated by yellow asterisks (artifact) and the arrows point to neutral lipids stained by Oil Red O. Scale bars = 10 μM. (e) Liver sections were scored using the Oil Red O Score described in the Materials and Methods, *P=0.0327 (10A+/+ n=6, 10A−/− n=10). (f) The diameters of Oil Red O positive lipid droplets (LD) in the liver sections with a score of 2 were measured using ImageJ. The red line in the graph represents the SEM, ****P=<0.0001 (10A+/+,120 LDs measured, n=2, 10A−/−, 203 LDs measured, n=3). P value by (a-c, f) unpaired t-test or (e) Mann-Whitney U test.

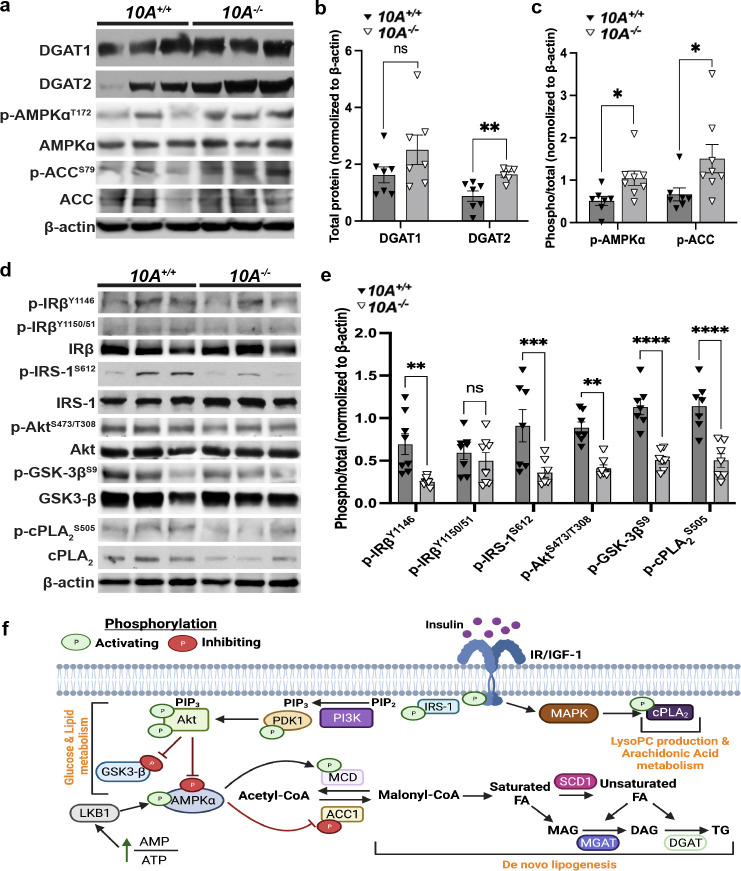

Atp10A deficiency results in changes to liver metabolic signaling.

Next, we evaluated potential hepatic mechanisms responsible for the metabolic phenotypes observed in the HFD fed female mice by examining key regulators of energy and lipid metabolism in the liver (Figure 6f). Diacylglycerol acyltransferases (DGATs) catalyze the final step in TG synthesis (Figure 6f) and we found that DGAT2 was significantly elevated in liver from HFD-fed Atp10A−/− females (Figure 6a,b). These results indicate that the lower liver FFA and larger lipid droplets in the hepatocytes might be due to the higher activity of DGAT2 in Atp10A−/− mice. AMP kinase (AMPK) is a central regulator of energy metabolism that inhibits acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) activity by phosphorylating it at S79 (Figure 6f). Western blot analysis showed that the phosphorylation of AMPKα at T172 and AMPK-dependent inhibitory phosphorylation of ACC at S79 were significantly increased in Atp10A−/− females (Figure 6a,c), which may further contribute to the decreased liver FFA in Atp10A−/− mice. Of note, insulin signaling including the activating phosphorylation of the insulin receptor β subunit (IRβ) at Y1146, insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) at S612, and Akt at S473/T308 were decreased in Atp10A−/− mice even though glucose tolerance was not significantly changed (Figures 6d,e and 2b). Consistent with the changes in insulin signaling, the Akt-dependent inhibitory phosphorylation at GSK-3β at S9 was also decreased in Atp10A−/− females (Figure 6d,e). Cytosolic phospholipase 2 (cPLA2) is an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of phospholipids, such as PC, to LysoPLs and AA, and AA can be oxidized to form eicosanoids (35). Interestingly, the activating phosphorylation of cPLA2 at S505 was decreased in the Atp10A−/− mice (Figure 6d,e), which might contribute to the decreases in eicosanoids in plasma from Atp10A−/− mice (Figure 4b). Altogether, these studies reveal that Atp10A deficiency in females fed a HFD results in several alterations to metabolic signaling in the liver, including depression of the insulin signaling pathway.

Figure 6. Atp10A deletion perturbs liver insulin signaling in female mice fed a HFD.

(a, d) Representative blots for total and/or phosphorylated (a) DGAT1, DGAT2, AMPKα, ACC, and (d) IRβ, IRS-1, Akt, GSK-3β, and cPLA2. (b) For DGAT1 and DGAT2 quantitation, total protein was normalized to β-actin levels. (c, e) The phosphoproteins were normalized to their respective total protein and β-actin levels. Mean measurements of 4–6 independent experiments are shown. P value by (b, c) unpaired t-test or (e) 2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test. (a-c, 10A+/+ n=7, 10A−/− n=7, b: **P=0.0050; c: *P=0.0229, *P=0.0481; d, e, 10A+/+ n=8, 10A−/− n=8, **P=0.0044, ***P=0.0007, **P=0.0038, ****P=<0.0001,). (f) Schematic adapted from (56) and created using Biorender.com. The illustration shows insulin binding to the insulin receptor and the resulting downstream signaling events that stimulate LysoPC production, AA metabolism, changes to glucose and lipid metabolism; including the promotion of lipogenesis. MAPK= mitogen-activated protein kinase, cPLA2= cytosolic phospholipase 2, IRS-1= insulin receptor substrate 1, PI3K= phosphoinositide 3-kinase, PIP2=phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, PIP3= phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate, PDK1= pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1, GSK-3β= glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta, LKB1= liver kinase B1, AMPKα= AMP-activated protein kinase alpha, MCD= malonyl-CoA decarboxylase, ACC1=acetyl-CoA carboxylase, SCD1= stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1, MGAT=monoglycerol acyltransferase, DGAT= diglyceride acyltransferase.

Discussion

This study reveals a requirement for ATP10A in protecting female mice from dyslipidemia after HFD feeding. Despite the normal weight gain and body composition (Figure 1), female Atp10A−/− mice display elevated plasma levels of FFA, cholesterol, and TGs, and these parameters are unchanged in male Atp10A−/− mice relative to WT controls (Figure 3, Supplemental Figure 3). The plasma lipidome, visceral fat transcriptome, as well as hepatic lipid metabolism are also substantially perturbed in the knockout female mice (Figure 4,5). Additionally, basal insulin signaling in the liver is depressed (Figure 6) although the plasma insulin levels are comparable to wild-type littermates (Figure 2d).

Atp10A deficient female mice exhibit dyslipidemia characterized by elevated plasma FFA, cholesterol, TG, and alterations in the size and lipid content of both VLDL and HDL (Figure 3a–f). A potential source of hyperlipidemia is de novo lipogenesis in the liver; however, Atp10A deficient mice exhibit decreased total liver FFAs (Figure 5a) and an increase in activating phosphorylation of hepatic AMPKα (Figure 6a,c), a master regulator of lipid metabolism, that increases FA oxidation and decreases de novo lipogenesis through inhibition of ACC (36). Consistently, we also observed elevated inhibitory AMPKα-dependent phosphorylation of ACC (Figure 6a,c). Thus, it is unlikely that de novo FA production in the liver is driving the excess plasma TG and FFAs. It is possible that an increased release of FFA from dietary lipids or adipose tissue drives an increase in TG synthesis in the liver and its secretion in VLDL (Figure 3g) (37–39). Indeed, we observed an increase in DGAT2 expression in the liver, which could account for the elevated TG. In addition, Lipf mRNA transcripts were elevated in visceral fat from Atp10A deficient mice (Figure 4c, Supplemental Table 2). Lipf codes for a gastric lipase that breaks down TG into glycerol and FFAs and has been shown to be highly expressed in adipose tissue in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity (40). It is possible that Atp10A deficiency exacerbates this phenomenon, even though the WT and mutant mice exhibit no difference in weight gain or adiposity during high fat diet feeding, via an unknown mechanism.

Loss of ATP10A also disrupts cholesterol metabolism in the female mice. Plasma cholesterol is elevated and the HDL particles carrying the cholesterol are skewed towards smaller sizes. Additionally, Atp10A deficient mice show reduced circulating levels of bile acids (Figure 4a,b), which are important signaling lipids with implications in cholesterol metabolism and cardiovascular health (41). Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms underlying the perturbations to cholesterol metabolism observed in Atp10A deficient mice.

The molecular basis for the female-specific dyslipidemia in Atp10A−/− mice is unclear. There are established differences in disease severity and prevalence between men and women (42). Premenopausal women tend to have lower cardiovascular risks compared to men and there are both hormonal and genetic contributions to sexual dimorphisms in lipid metabolism (43,44). The Atp10A promoter is predicted to have a transcription factor binding site for estrogen receptor alpha (Genecards.org, QIAGEN), so it is possible that differences in expression due to sex contribute to the consequences of Atp10A deletion. It is also possible that sex hormones either suppress the effect of Atp10A−/− on lipid metabolism in males or promotes these phenotypes in females. We did not measure the lipoprotein profiles, perform plasma lipidomics, or measure metabolic liver signaling pathways in male mice because they did not exhibit diet-induced dyslipidemia (Supplemental Figure 3a–c). Interestingly, we found that WT male mice exhibited higher levels of fasting FFA and cholesterol than WT females, suggesting a sex-based difference in the kinetics of lipid clearance during the postprandial response (Figure 3a–c, Supplemental Figure 3a–c). There is a need for a comprehensive investigation comparing fasting levels of lipids between male and female mice after HFD feeding to uncover potential sexual dimorphisms and elucidate the underlying mechanisms driving such differences.

Atp10A deficient female mice display elevated levels of monounsaturated versus saturated TG, PL, and cholesterol ester (CE) species in their livers (Figure 5b,c). This could be due to an increase in activity of stearoyl-CoA desaturase–1 (SCD1), an enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of monounsaturated FAs from saturated FAs (Figure 6f). Interestingly, Scd1 activity has been suggested to be required for the onset of diet-induced hepatic insulin resistance (45). Liver sections from Atp10A deficient mice exhibit increased Oil Red O staining, a stain that binds neutral lipids, as well as larger lipid drops compared to control mice (Figure 5d–f). We observed an increase in the expression of DGAT2 (Figure 6b) in the liver of Atp10A deficient mice, but no significant increase in liver TG (Supplemental Figure 4d) or cholesterol levels (Supplemental Figure 4a–c), therefore the increase in Oil Red O staining could be due to staining of another neutral lipid and this needs to be further explored. Furthermore, female Atp10A deficient mice display impaired insulin signaling in the liver (Figure 6), highlighting the need for further exploration to elucidate the relationship between dyslipidemia, liver lipid metabolism, and altered insulin signaling observed in these mice.

Our studies suggest that Atp10A deficiency disrupts the regulation of cPLA2 activity and the production of eicosanoids. We found a reduction of activating phosphorylation of cPLA2 in the liver (Figure 6d,e) as well as a depletion of circulating levels of eicosanoids (Figure 4a,b) due to ATP10A deficiency. cPLA2 hydrolyzes PC to release AA which can be oxidized to form eicosanoids, bioactive lipids with roles in inflammation and vasculature maintenance (46,47). cPLA2 can only act on lipids in the cytosolic leaflet and ATP10A could potentially provide additional PC substrate to this enzyme, derived from the extracellular leaflet or an external source, such as lipoproteins. Interestingly, ATP10A can also translocate GlcCer to potentially promote synthesis of ceramide 1-phosphate (C1P) (Figure 4d), another activator of cPLA2 (48). cPLA2 hydrolysis of PC also produces LysoPC, a bioactive lipid that may link saturated FAs to insulin resistance (49). Despite the reduction of eicosanoids in the plasma, there was no substantial difference in the levels of circulating LysoPC based on genotype. It is possible that the increased expression of Pla2g5 (Figure 4c, Supplemental Table 2), a secreted phospholipase, may have compensated for the perturbations in cPLA2 signaling and normalized LysoPC levels in the plasma. Further work is needed to better define the specific influence of ATP10A on cPLA2 signaling and eicosanoid production.

Prior studies analyzing mice with an overlapping series of radiation-induced deletions encompassing the p locus on chromosome 7 implicated Atp10A deficiency in diet-induced obesity, insulin resistance indicated by reduced efficacy of insulin in mediating glucose disposal, and hyperlipidemia, and reported that these phenotypes were more severe in females compared to males (26,27). Additionally, the phenotypes were observed in heterozygous mice that inherited the chromosomal deletion maternally, suggesting that the paternal Atp10A allele was silenced. In support of this possibility, we found that heterozygous male mice inheriting the Atp10A exon 2 deletion maternally displayed a trend toward increased weight gain over the course of the HFD and had significantly shorter bodies and elevated fasting blood glucose compared to mice that inherited the deletion paternally (Supplemental Figure 2a,d,e). However, we found no evidence for increased obesity or metabolic defects in female Atp10A+/− heterozygous mice inheriting the KO allele paternally or maternally (Supplemental Figure 2), nor did the Atp10A−/− homozygous mice display alterations to the development of diet-induced obesity or defects in glucose metabolism (Figure 1,2). This difference is most likely because the mice used in previous studies had a large chromosomal deletion that, in addition to Atp10A, removed several other genes, some of which are known to be imprinted (50). It is also possible that differences in the strain background or rearing environment alter the susceptibility of Atp10A deficient mice to weight gain on a HFD and glucose metabolism perturbations. However, our results are consistent with previous reports in that ATP10A has a stronger influence on lipid metabolism in female mice relative to males (26). We have shown that ATP10A is required to maintain lipid homeostasis and liver insulin sensitivity with HFD feeding, therefore, a therapeutic that acts as an ATP10A agonist could help treat diseases that cause dyslipidemia and hepatic insulin resistance.

Methods

Animals.

All mouse experiments were approved under the Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were housed in 12 h light/dark cycles in temperature and humidity-controlled facilities with ad-libitum access to diet and water.

Creating the mouse model.

The Atp10A mouse model (knockout allele name: Atp10Aem1(Vtrg) (allele designation approval pending)) was created via CRISPR-Cas9 in collaboration with the Vanderbilt Genome Editing Resource. Guide RNAs (crRNA) were created to target Atp10A on chromosome 7: Target Intron 1–2: TGACTGCTTAATGATTCGAGG, GAGTGACTGCTAATGATCG, Target Intron 2–3: GGAAAAAGCCCAATTCCACAC, AGCCCAATCCACACAGGAAC. CRISPR editing reagents were delivered into the pronuclei of one-cell fertilized mouse zygotes (C57BL/6J). Approximately 608 bp were deleted using this method: nucleotides 58389679–58390287 (NCBI reference sequence: NC_000073). The resulting pups were biopsied and screened by PCR and Sanger sequencing. The predicted founders were bred to WT C57BL/6J animals and the offspring were genotyped (N1 generation). The offspring with the appropriate genotype were then backcrossed two more times.

Genotyping.

Mice were genotyped using tail DNA. Atp10A DNA products were detected via PCR (Q5 DNA Polymerase, NEB) followed by gel electrophoresis; Atp10A-F (GTGCACTGTATTTGTCTGCCTGTTCC), Atp10A-R (GGTCCTTTGAAGAGATAATGTTCCCAAC).

Body composition, body length, and tissue mass.

WT and experimental mice were fed standard chow or 60% HFD (D12492, Research Diets) ad libitum, starting at the age of 3–12 weeks old (see Supplemental Table 3). Mice were weighed once per week to measure body weight gain over time. On the 12th week on the HFD, body composition was assessed via NMR (LF50 Body Composition Mice Analyzer, Bruker, stock # E140000501). Mice were sacrificed with CO2, the body lengths were measured and the mass of the wet tissue was measured using an analytical scale. Tissues were collected and flash frozen when mice were sacrificed.

Oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT) and fasting blood glucose/insulin measurements.

Mice were fasted for 5 hours (7AM-12PM) and then an OGTT was performed. Mice were gavaged with 20% w/v dextrose (final 2g/kg body weight), and a tail-vein blood glucose was measured via a glucometer (Accu-Chek, Accu-Chek Aviva Plus Meter) at baseline, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 min. The area under of the curve for glucose was calculated using GraphPad Prism. Plasma samples were collected from 5-hr fasted mice via a retroorbital bleed and were used for the insulin assay. Plasma insulin was measured using the Crystal Chem Ultrasensitive Mouse Insulin ELISA Kit (catalog # 90080).

Plasma lipid and lipoprotein analysis.

Plasma was collected, via a retroorbital bleed or cardiac puncture, from 5-hr fasted mice and 5-hr fasted mice that had undergone an OGTT (see Supplemental Table 3). For males and a portion of the female samples: plasma TG and cholesterol were measured using colorimetric kits (note that the TG measurements include free glycerol) (Inifinity, Thermo Scientific, TG catalog #TR22421, chol catalog #TR13421) and plasma FFAs were measured using Abcam’s Free Fatty Acid Assay Kit-Quantification (ab65341). For the rest of the females: plasma samples were measured by the Vanderbilt Hormone Assay and Analytical Services Core, where plasma cholesterol and TG were measured by standard enzymatic assays, and plasma FFAs were analyzed with an enzymatic kit (Fujifilm Healthcare Solutions, catalog #999-34691). Lipoproteins were separated using FPLC on a Superose6 column (GE Healthcare) from 150 μl plasma (single mouse or pooled) and the TG and cholesterol content were measured using colorimetric kits (Inifinity, Thermo Scientific, TG catalog #TR22421, chol catalog #TR13421). AUC was calculated using GraphPad Prism.

Plasma lipidomics.

Plasma was collected, via a retroorbital bleed or cardiac puncture, from 5-hr fasted mice and some samples are pooled plasma (see Supplemental Table 3). Lipid metabolites were extracted from 100 μL plasma by methyl methyltert-butyl ether (MTBE) extraction. The lipid metabolites were then analyzed by HPLC-IM-MS/MS on an Agilent 6560 mass spectrometer using a ZORBAX Extend-C18 RPLC column (Phase A: 0.1% formic acid and 10 mM NH4CHOO in water, Phase B: 0.1% formic acid and 10 mM NH4CHOO in 60:36:4 isopropanol:acetonitrile: H2O) (51). Data alignment and biostatical analysis was performed using Progenesis QI (Waters). Tentative compound identifications were assigned using accurate mass databases and a previously described ion mobility-based filtering method (52).

RNA Sequencing.

Visceral fat was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and then kept at −80°C until thawed at −20°C in RNAlater (ThermoFisher, catalog # AM7030). The tissue was then homogenized in QIAzol Lysis Reagent (Qiagen, catalog #79306) using a Bullet Blender (Next Advance, BT24M). The RNA layer acquired after the QIAzol Lysis protocol was cleaned up using the RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen, catalog #NC9036170). Quality control measurements and Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) was performed on 20 uL of RNA (>10 ng) by Vanderbilt Technologies for Advanced Genomics (VANTAGE); briefly, NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA kit (Cat no: E7760L) was used and for the sequencing; NovaSeq 6000 and PE150 read lengths were used. Analysis of NGS data was performed by Vanderbilt Technologies for Advanced Genomics Analysis and Research Design (VANGARD).

Immunoblot analysis.

For lysis of liver tissue samples, T-PER (Pierce, Rockford, IL) with phosphatase and protease inhibitors (Sigma) was used. Protein concentration was quantified using BCA Reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Protein extracts (100 μg) were subjected to Western immunoblot analysis. The following primary antibodies were used for detection of: DGAT1 (sc-32861, Santa Cruz Biotech), DGAT2 (sc-66859, Santa Cruz Biotech), phospho-AMPKαT172 (#2535, Cell Signaling), AMPKα (#2532, Cell Signaling), phospho-ACCS79 (#3661, Cell Signaling), ACC (#3676, Cell Signaling), phospho-IGF-IRβY1131/IRβY1146 (#3021, Cell Signaling), phospho-IGF-IRβY1135/1136/IRβY1150/1151(#3024, Cell Signaling), IRβ (#3025, Cell Signaling), phospho-IRS-1S612 (#3203, Cell Signaling), IRS-1 (#3407, Cell Signaling), phospho-AktT308/S473 (#13038/#4060, Cell Signaling), Akt (#9272, Cell signaling), phospho-GSK-3βS9 (#5558, Cell Signaling), GSK-3β (#9315, Cell Signaling), phospho-cPLA2αS505(#53044, Cell Signaling), cPLA2α (#5249, Cell Signaling). Antibody to β-actin (#4970, Cell Signaling) was used to evaluate protein loading in each lane. Immunoblots were developed using the Western Lightning Chemiluminescence Plus detection system (PerkinElmer, Wellesley, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Intensity of the immunoblot bands was measured using AI600 CCD Imager for chemiluminescent assays (Amersham). Densitometry was performed using ImageJ. For quantification, OD of bands for phosphoprotein was normalized to total protein and β-actin; otherwise, OD of bands for total protein was normalized to β-actin.

Promethion System.

Indirect calorimetry and additional measures of food intake and physical activity were performed in open-circuit indirect calorimetry cages (Promethion System, Sable Systems International) at Vanderbilt Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center (MMPC). One week prior to the experiment start date, mice were singly housed for acclimation. On the day of the experiment start date, mice were weighed and body composition was assessed. The mice were placed in the cages of the Promethion system, one mouse per cage. The cages were housed in a light and temperature-controlled chamber. The light cycle was set on a 12:12h cycle (6am-6pm). Mice were left undisturbed for 5 days during which all the measurements were made. The system periodically measured rates of O2 consumption (VO2) and CO2 production (VCO2) for each cage, as well as food intake and physical activity (infrared beam array). Data were processed in time segments (daily 24-hour, and 12-hour dark/12-hour light), and averages calculated for each as well as for the 24-hour period. After 5 days, the mice were removed from the cages, and body composition and weight were measured again. Data was further processed using CalR (www.calrapp.org).

Measuring liver lipids.

Liver FFA, total cholesterol, cholesterol ester, unesterified cholesterol, TG, PLs, and ceramides were measured by the Vanderbilt Hormone Assay and Analytical Services Core using methods described in (53,54).

Oil Red O.

Livers were placed in frozen section medium (Epredia, Neg-50, catalog #22-110-617) and then placed on dry ice. When the frozen section medium was solidified, the livers were placed at −20°C until further processing. Further processing was done by the Vanderbilt Translation Pathology Shared Resource (TPSR): Slides were brought to room temperature and placed in 10% NBF solution for 10 minutes. The Newcomer Supply Tech Oil Red O, Propylene Glycol staining kit (Newcomer Supply, catalog # 12772B) was used for visualization. Slides were then cover slipped with aqueous mounting medium. In regard to Oil Red O scoring: Dr. Katherine Gibson Corley, a board-certified veterinary pathologist at the Vanderbilt TPSR, created the scoring system used to score the Oil Red O stained liver sections. The scoring system is characterized by: 0= no Oil Red O staining, 1=rare and scattered Oil Red O staining, 2=multi-focal and coalescing Oil Red O staining, 3=diffuse Oil Red O staining (in whole tissue). To score the slides, the scorer was blinded to the slide IDs and then scored the slides twice, on two separate days. Then the scores from both days were compared and if they did not match, the scorer viewed the slide again and decided on a final score. The diameter of the Oil Red O positive lipid droplets was measured from slides with a score of 2, using ImageJ. Images of tissues were acquired using light microscopy (Zeiss AxioPlan, Upright Fluorescence Microscope, Germany) with a x5/1.0 or x63/1.0 Oil using the Zeiss Axio Color Camera (Axiocam 208c) and the ZEN 3.1 software (blue edition). Microscope settings were held constant for all experimental groups.

Statistics.

All statistical analysis was done using GraphPad Prism, version 9.5.0 (GraphPad Software). Error bars indicate mean with standard error of the mean (SEM). When more than 2 groups were compared, a 2-way ANOVA was used with Dunnett’s correction for multiple comparisons with a control group. Šidák’s correction was used for comparison of groups of means. Differences between group mean values were tested using a 2-tailed Student’s t test or a Mann-Whitney U test for nonparametric data. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Study approval.

The animal protocol was approved by Vanderbilt University Medical Center and IACUC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Vanderbilt Genome Editing Resource for creating the Atp10A mouse lines and assisting with genotyping (supported by the Cancer Center Support Grant (CA68485), the Vanderbilt Diabetes Research and Training Center (DK020593) and the Center for Stem Cell Biology), the Vanderbilt Division of Animal Care veterinarians and technicians for their support with mouse husbandry, the Vanderbilt Metabolic Mouse Phenotyping Center (MMPC) especially Louise Lantier, for providing the NMR machine for body composition measurements and for performing the indirect calorimetry (DK135073, DK020593, S10RR028101), the Vanderbilt Analytical services core for measuring plasma and liver lipids (supported by NIH grant DK020593 (DRTC)), the Translational Pathology Shared Resource (TPSR) for producing all of the paraffin embedded tissue sections and performing the Oil Red O and CD31 staining (supported by NCI/NIH Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA068485), the Vanderbilt Cell Imaging Shared Resource (CISR) for providing the Zeiss LSM880 Airyscan Confocal Microscope used in this study (supported by NIH grants CA68485, DK20593, DK58404, DK59637, and EY08126; Zeiss LSM880 Airyscan Confocal Microscope acquired through NIH 1 S10 OD021630 1), the Center for Innovative Technology at Vanderbilt for providing access to the mass spectrometry instrumentation and lipidomics software, The Metabolomics Workbench (supported by NIH grants U2C-DK119886 and OT2-OD030544), Sophia Yu, Teri Stevenson, and Staci Bordash for help with mouse experiments, and Bridget Litts for help with finding materials and using equipment. We also thank David Wasserman, Owen McGuiness and David Harrison for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH 1R35GM144123 (to TRG), K01AG077038 (to LZ), NIH R01DK109102, R01HL144846, and T35DK7383, The Department of Veterans Affairs BX002223 (to JMS).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Data Availability.

The untargeted lipidomics data is available at the NIH Common Fund’s National Metabolomics Data Repository (NMDR) website, the Metabolomics Workbench (55), where it has been assigned Study ID ST002696. The data can be accessed directly via its ProjectDOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21228/M83H7N. The reads from the RNASeq data can be found at NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/samplerecord/) using these accession numbers: SRR24233646 (Atp10A WT reads) and SRR24233645 (Atp10A KO reads).

References

- 1.Aguilar M., Bhuket T., Torres S., Liu B., & Wong R. J. (2015). Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in the United States, 2003–2012. JAMA, 313(19). 10.1001/jama.2015.4260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Neill S., & O’Driscoll L. (2015). Metabolic syndrome: A closer look at the growing epidemic and its associated pathologies. Obesity Reviews, 16(1). 10.1111/obr.12229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fahed G., Aoun L., Zerdan M. B., Allam S., Zerdan M. B., Bouferraa Y., & Assi H. I. (2022). Metabolic Syndrome: Updates on Pathophysiology and Management in 2021. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, Vol. 23. 10.3390/ijms23020786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnett D. K. (2011). Genome-wide detection of allele specific copy number variation associated with insulin resistance in african americans from the hyperGEN study. PLoS ONE. 10.1371/journal.pone.0024052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kengia J. T., Ko K. C., Ikeda S., Hiraishi A., Mieno-Naka M., Arai T., … Sawabe M. (2013). A gene variant in the Atp10d gene associates with atherosclerotic indices in Japanese elderly population. Atherosclerosis, 231(1). 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen J. P., Vestergaard A. L., Mikkelsen S. A., Mogensen L. S., Chalat M., & Molday R. S. (2016). P4-ATPases as phospholipid flippases-structure, function, and enigmas. Frontiers in Physiology. 10.3389/fphys.2016.00275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segawa K., Kurata S., Yanagihashi Y., Brummelkamp T. R., Matsuda F., & Nagata S. (2014). Caspase-mediated cleavage of phospholipid flippase for apoptotic phosphatidylserine exposure. Science. 10.1126/science.1252809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kook S., Wang P., Meng S., Jetter C. S., Sucre J. M. S., Benjamin J. T., … Guttentag S. H. (2021). AP-3-dependent targeting of flippase ATP8A1 to lamellar bodies suppresses activation of YAP in alveolar epithelial type 2 cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(20). 10.1073/pnas.2025208118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ristovski M., Farhat D., Bancud S. E. M., & Lee J. Y. (2021). Lipid transporters beam signals from cell membranes. Membranes, Vol. 11. 10.3390/membranes11080562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Mark V. A., Oude Elferink R. P. J., & Paulusma C. C. (2013). P4 ATPases: Flippases in health and disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 10.3390/ijms14047897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naito T., Takatsu H., Miyano R., Takada N., Nakayama K., & Shin H. W. (2015). Phospholipid flippase ATP10A translocates phosphatidylcholine and is involved in plasma membrane dynamics. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 290(24). 10.1074/jbc.M115.655191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roland B. P., Naito T., Best J. T., Arnaiz-Yépez C., Takatsu H., Yu R. J., … Graham T. R. (2019). Yeast and human P4-ATPases transport glycosphingolipids using conserved structural motifs. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.005876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Francisco Ramos-Martín Nicola D Amelio (2022). Biomembrane lipids: When physics and chemistry join to shape biological activity. Biochimie, Volume 203, Pages 118–138,ISSN 0300-9084. 10.1016/j.biochi.2022.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Law S. H., Chan M. L., Marathe G. K., Parveen F., Chen C. H., & Ke L. Y. (2019). An updated review of lysophosphatidylcholine metabolism in human diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, Vol. 20. 10.3390/ijms20051149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knuplez E., & Marsche G. (2020). An updated review of pro-and anti-inflammatory properties of plasma lysophosphatidylcholines in the vascular system. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, Vol. 21. 10.3390/ijms21124501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu P., Zhu W., Chen C., Yan B., Zhu L., Chen X., & Peng C. (2020). The mechanisms of lysophosphatidylcholine in the development of diseases. Life Sciences, Vol. 247. 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamaguchi A, Botta E, Holinstat M. Eicosanoids in inflammation in the blood and the vessel. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:997403. Published 2022 Sep 27. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.997403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell J. A., & Kirkby N. S. (2019). Eicosanoids, prostacyclin and cyclooxygenase in the cardiovascular system. British Journal of Pharmacology, Vol. 176. 10.1111/bph.14167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishibashi Y., Kohyama-Koganeya A., & Hirabayashi Y. (2013). New insights on glucosylated lipids: Metabolism and functions. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids, Vol. 1831. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mobarak E., Håversen L., Manna M., Rutberg M., Levin M., Perkins R., … Borén J. (2018). Glucosylceramide modifies the LPS-induced inflammatory response in macrophages and the orientation of the LPS/TLR4 complex in silico. Scientific Reports, 8(1). 10.1038/s41598-018-31926-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aerts J. M., Ottenhoff R., Powlson A. S., Grefhorst A., Van Eijk M., Dubbelhuis P. F., … Overkleeft H. S. (2007). Pharmacological inhibition of glucosylceramide synthase enhances insulin sensitivity. Diabetes, 56(5). 10.2337/db06-1619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baccam G.C., Xie J., Jin X. et al. Glucosylceramide synthase inhibition protects against cardiac hypertrophy in chronic kidney disease. Sci Rep 12, 9340 (2022). 10.1038/s41598-022-13390-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bikman B. T., & Summers S. A. (2011). Ceramides as modulators of cellular and whole-body metabolism. Journal of Clinical Investigation, Vol. 121. 10.1172/JCI57144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turpin-Nolan S. M., & Brüning J. C. (2020). The role of ceramides in metabolic disorders: when size and localization matters. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, Vol. 16. 10.1038/s41574-020-0320-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandhoff Roger, Schulze Heike, Sandhoff Konrad. (2018).Chapter One - Ganglioside Metabolism in Health and Disease, Editor(s): Schnaar Ronald L., Lopez Pablo H.H.. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science,Academic Press, Volume 156, Pages 1–62, ISSN 1877-1173, ISBN 9780128123416, 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dhar M. S., Sommardahl C. S., Kirkland T., Nelson S., Donnell R., Johnson D. K., & Castellani L. W. (2004). Mice Heterozygous for Atp10c, A Putative Amphipath, Represent A Novel Model of Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Journal of Nutrition, 134(4). 10.1093/jn/134.4.799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dhar M. S., Yuan J. S., Elliott S. B., & Sommardahl C. (2006). A type IV P-type ATPase affects insulin-mediated glucose uptake in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle in mice. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kayashima T., Ohta T., Niikawa N., Kishino T., & Oshimura M. (2003). On the conflicting reports of imprinting status of mouse ATP10a in the adult brain: Strain-background-dependent imprinting? (multiple letters). Journal of Human Genetics, Vol. 48. 10.1007/s10038-003-0061-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hogart A., Patzel K. A., & LaSalle J. M. (2008). Gender influences monoallelic expression of ATP10A in human brain. Human Genetics, 124(3). 10.1007/s00439-008-0546-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DuBose A. J., Johnstone K. A., Smith E. Y., Hallett R. A. E., & Resnick J. L. (2010). Atp10a, a gene adjacent to the PWS/AS gene cluster, is not imprinted in mouse and is insensitive to the PWS-IC. Neurogenetics. 10.1007/s10048-009-0226-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurst S. E., Minkin S. C., Biggerstaff J., & Dhar M. S. (2012). Transient silencing of a type IV P-type ATPase, Atp10c, results in decreased glucose uptake in C2C12 myotubes. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2012. 10.1155/2012/152902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhattacharyya S., Luan J., Challis B., Keogh J., Montague C., Brennand J., … O’Rahilly S. (2006). Sequence variants in the melatonin-related receptor gene (GPR50) associate with circulating triglyceride and HDL levels. Journal of Lipid Research, 47(4). 10.1194/jlr.M500338-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ivanova E. A., Bechtold D. A., Dupré S. M., Brennand J., Barrett P., Luckman S. M., & Loudon A. S. I. (2008). Altered metabolism in the melatonin-related receptor (GPR50) knockout mouse. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology and Metabolism, 294(1). 10.1152/ajpendo.00199.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yao Z., Meng J., Long J., Li L., Qiu W., Li C., … Ren P. G. (2023). Orphan receptor GPR50 attenuates inflammation and insulin signaling in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. FEBS Open Bio, 13(1). 10.1002/2211-5463.13516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niknami M., Patel M., Witting P. K., & Dong Q. (2009). Molecules in focus: Cytosolic phospholipase A2-α. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Vol. 41. 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcia D., & Shaw R. J. (2017). AMPK: Mechanisms of Cellular Energy Sensing and Restoration of Metabolic Balance. Molecular Cell, Vol. 66. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.05.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barter P. J., & Nestel P. J. (1973). Precursors of plasma triglyceride fatty acids in obesity. Metabolism, 22(6). 10.1016/0026-0495(73)90048-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kissebah A. H., Alfarsi S., Adams P. W., & Wynn V. (1976). Role of insulin resistance in adipose tissue and liver in the pathogenesis of endogenous hypertriglyceridaemia in man. Diabetologia, 12(6). 10.1007/BF01220632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewis GF. Lipid metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1999. Oct;10(5):475–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato H., Taketomi Y., Ushida A., Isogai Y., Kojima T., Hirabayashi T., … Murakami M. (2014). The adipocyte-inducible secreted phospholipases PLA2G5 and PLA2G2E play distinct roles in obesity. Cell Metabolism, 20(1). 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanafi N. I., Mohamed A. S., Kadir S. H. S. A., & Othman M. H. D. (2018). Overview of bile acids signaling and perspective on the signal of ursodeoxycholic acid, the most hydrophilic bile acid, in the heart. Biomolecules, Vol. 8. 10.3390/biom8040159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crimmins E. M., Shim H., Zhang Y. S., & Kim J. K. (2019). Differences between men and women in mortality and the health dimensions of the morbidity process. Clinical Chemistry, Vol. 65. 10.1373/clinchem.2018.288332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmisano B. T., Zhu L., Eckel R. H., & Stafford J. M. (2018). Sex differences in lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Molecular Metabolism, Vol. 15. 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Link J. C., & Reue K. (2017). Genetic Basis for Sex Differences in Obesity and Lipid Metabolism. Annual Review of Nutrition, Vol. 37. 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071816-064827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gutiérrez-Juárez R., Pocai A., Mulas C., Ono H., Bhanot S., Monia B. P., & Rossetti L. (2006). Critical role of stearoyl-CoA desaturase - 1 (SCD1) in the onset of diet-induced hepatic insulin resistance. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 116(6). 10.1172/JCI26991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell J. A., & Kirkby N. S. (2019). Eicosanoids, prostacyclin and cyclooxygenase in the cardiovascular system. British Journal of Pharmacology, Vol. 176. 10.1111/bph.14167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamaguchi A, Botta E and Holinstat M (2022) Eicosanoids in inflammation in the blood and the vessel. Front. Pharmacol. 13:997403. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.997403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chalfant C. E., & Spiegel S. (2005). Sphingosine 1-phosphate and ceramide 1-phosphate: Expanding roles in cell signaling. Journal of Cell Science, 118(20). 10.1242/jcs.02637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Han M. S., Lim Y. M., Quan W., Kim J. R., Chung K. W., Kang M., … Lee M. S. (2011). Lysophosphatidylcholine as an effector of fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. Journal of Lipid Research, 52(6). 10.1194/jlr.M014787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Butler M. G. (2020). Imprinting disorders in humans: a review. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, Vol. 32. 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.May J. C., Goodwin C. R., Lareau N. M., Leaptrot K. L., Morris C. B., Kurulugama R. T., … McLean J. A. (2014). Conformational ordering of biomolecules in the gas phase: Nitrogen collision cross sections measured on a prototype high resolution drift tube ion mobility-mass spectrometer. Analytical Chemistry, 86(4). 10.1021/ac4038448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rose B. S., May J. C., Picache J. A., Codreanu S. G., Sherrod S. D., & Mclean J. A. (2022). Improving confidence in lipidomic annotations by incorporating empirical ion mobility regression analysis and chemical class prediction. Bioinformatics, 38(10). 10.1093/bioinformatics/btac197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.FOLCH J., LEES M., & SLOANE STANLEY G. H. (1957). A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 226(1). 10.1016/s0021-9258(18)64849-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morrison W. R., & Smith L. M. (1964). Preparation of fatty acid methyl esters and dimethylacetals from lipids with boron fluoride–methanol. Journal of Lipid Research, 5(4). 10.1016/s0022-2275(20)40190-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sud M., Fahy E., Cotter D., Azam K., Vadivelu I., Burant C., … Subramaniam S. (2016). Metabolomics Workbench: An international repository for metabolomics data and metadata, metabolite standards, protocols, tutorials and training, and analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Research, 44(D1). 10.1093/nar/gkv1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang B. B., Zhou G., & Li C. (2009). AMPK: an emerging drug target for diabetes and the metabolic syndrome. Cell metabolism, 9(5), 407–416. 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The untargeted lipidomics data is available at the NIH Common Fund’s National Metabolomics Data Repository (NMDR) website, the Metabolomics Workbench (55), where it has been assigned Study ID ST002696. The data can be accessed directly via its ProjectDOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21228/M83H7N. The reads from the RNASeq data can be found at NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/samplerecord/) using these accession numbers: SRR24233646 (Atp10A WT reads) and SRR24233645 (Atp10A KO reads).