Abstract

Introduction

Given the vulnerability of children during the COVID-19 pandemic, paying close attention to their wellbeing at the time is warranted. The present protocol-based systematic mixed-studies review examines papers published during 2020–2022, focusing on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children's internalizing/externalizing symptoms and the determinants thereof.

Method

PROSPERO: CRD42022385284. Five databases were searched and the PRISMA diagram was applied. The inclusion criteria were: papers published in English in peer-reviewed journals; papers published between January 2020 and October 2022 involving children aged 5–13 years; qualitative, quantitative, and mixed studies. The standardized Mixed Method Appraisal Tool protocol was used to appraise the quality of the studies.

Results

Thirty-four studies involving 40,976 participants in total were analyzed. Their principal characteristics were tabulated. The results showed that children's internalizing/externalizing symptoms increased during the pandemic, largely as a result of disengagement from play activities and excessive use of the internet. Girls showed more internalizing symptoms and boys more externalizing symptoms. Distress was the strongest parental factor mediating children's internalizing/externalizing symptoms. The quality of the studies was appraised as low (n = 12), medium (n = 12), and high (n = 10).

Conclusion

Gender-based interventions should be designed for children and parents. The studies reviewed were cross-sectional, so long-term patterns and outcomes could not be predicted. Future researchers might consider a longitudinal approach to determine the long-term effects of the pandemic on children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

Systematic review registration

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022385284, identifier: CRD42022385284.

Keywords: COVID-19, child, internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, systematic mixed studies review, MMAT

1. Introduction

In most countries, the main restrictive measures applied to control the spread of COVID-19 between 2020 and 2022 included total lockdowns (or “sheltering in place” in North America), the closure of educational institutions and workplaces, social isolation, and prohibitions on gatherings. These restrictions significantly affected mental health within the general population (Hossain et al., 2020)—for instance, high levels of stress amongst health care professionals (Batra et al., 2020; Muller et al., 2020; Newby et al., 2020; Franklin and Gkiouleka, 2021) and low levels of wellbeing and even burnout amongst educators (partly as a response to the shift from one-to-one to remote teaching; Chan et al., 2021; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2021; Levante et al., 2023). Meanwhile, many parents found it difficult to balance work and family life (Graham et al., 2021). Because schools were closed, they were obliged to serve a range of roles (e.g., those of educator, caregiver, and playmate) for their typically developing children (Spinelli et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2022) or their atypically developing children (Levante et al., 2021; Calderwood et al., 2022).

Confinement and uncertainty (Petrocchi et al., 2022) had detrimental effects on several aspects of children's psychological functioning, such as high levels of anxiety (Orgilés Amorós et al., 2021; Aras Kemer, 2022), depression (Duan et al., 2020; Orgilés Amorós et al., 2021), hyperactivity and peer issues (Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2022), attention problems, aggressive behaviors (Khoury et al., 2021), and nervousness and irritability (Mariani Wigley et al., 2021). Some children developed sleep problems (Fidanci et al., 2021), insomnia (Bacaro et al., 2021), and eating disorders (Capra et al., 2023) consequent upon the disruption of their daily routines. Although COVID-19 was acknowledged by the authorities to pose a minute risk to children (Shekerdemian et al., 2020), previous literature has shown that they are more vulnerable to stress and low levels of wellbeing during emergencies and disasters (Danese et al., 2020; Raccanello and Vicentini, 2022).

In light of the above, we decided to carry out a systematic review of empirical studies investigating the impact of the pandemic on children's mental health. We focused on middle childhood, which encompasses the ages 5–13 years. According to Erikson's psychosocial model (Erikson, 1993), the circle of influence on children widens during this period (largely as a result of going to school and social interactions generally). When children have satisfactory social relationships (i.e., they develop a sense of industry), they perform developmental tasks successfully; when they do not, they are at risk of developing emotional and behavioral problems (e.g., a sense of inferiority; Erikson, 1993).

During the pandemic, children were compelled to forsake in-person social interactions for prolonged periods, and a pattern of internalizing and externalizing symptoms emerged (Nivard et al., 2017). Internalizing symptoms are an expression of an individual's internal distress (e.g., trait anxiety and depression; Cosgrove et al., 2011). Externalizing symptoms are expressed outwardly (e.g., aggression, defiance, and behavioral problems; Cosgrove et al., 2011). Pre-pandemic evidence (Bukowski and Adams, 2005; Laursen et al., 2007) revealed that social isolation during middle childhood negatively affected the mental health of adolescents and young adults (e.g., in terms of depression, anxiety, aggression, and anger).

To the best of our knowledge, four systematic reviews of empirical studies carried out during the pandemic have been published, primarily evaluating the mental health of children overall. Ma et al. (2021) measured the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children's and adolescents' depressive symptoms, trait anxiety, sleep problems, and post-traumatic stress symptoms. The three others (Aarah-Bapuah et al., 2022; Amorós-Reche et al., 2022; Ng and Ng, 2022) explored participants' emotional and mood problems (Amorós-Reche et al., 2022), depressive symptoms and anxiety (Aarah-Bapuah et al., 2022; Amorós-Reche et al., 2022; Ng and Ng, 2022), withdrawal (Ng and Ng, 2022), and anger and irritability (Ng and Ng, 2022).

Although these reviews provide valuable information, they have certain limitations. Amorós-Reche et al. (2022) and Ng and Ng (2022) examined studies published over 2 years (i.e., 2020–2021), but the other two papers (Ma et al., 2021; Aarah-Bapuah et al., 2022) covered only 6–9 months. Ma et al. (2021) and Amorós-Reche et al. (2022) limited their electronic searches to studies carried out in Spain and China/Turkey, respectively. The most recent review, by Ng and Ng (2022), extracted data from papers published up to February 2022 but did not include mixed studies carried out during the pandemic. Given that the impact of the latter on children's mental health is an exponentially growing field of research, an updated systematic review summarizing the results published thus far on children's internalizing/externalizing symptoms during the period is needed. The present study systematically extracted and reviewed studies that used qualitative, quantitative, and mixed study designs and applied a narrative approach to synthesize the findings in accordance with a standardized protocol. The research questions were formulated according to the PEO format. We extracted papers on typically developing children (Population) carried out during the pandemic (Exposure) that investigated their internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Outcomes), then formulated the following research questions:

RQ1: What was the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children's internalizing/externalizing symptoms?

RQ2: What psychological determinants were associated with or contributed to their internalizing/externalizing symptoms?

RQ3: Were there any gender differences in terms of children's internalizing/externalizing symptoms?

RQ4: Did any parent-related psychological determinants associate with or contribute to children's internalizing/externalizing symptoms?

2. Methods and materials

The review protocol was pre-registered on PROSPERO (Protocol No. CRD42022385284).

2.1. Search strategy

To extract the studies for review, we applied the updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) diagram (Page et al., 2021). An initial electronic search of MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, SCOPUS, and Web of Science was carried out in October 2022. In accordance with the PEO format, the keywords and MeSH terms were combined using the Boolean operators AND and OR: child*, OR children AND COVID* OR coronavirus OR corona OR COVID-19 OR COVID19 OR COVID OR SARS-CoV-2 OR SARSCoV-2 OR novel coronavirus OR SARS virus OR pandemic OR severe acute respiratory syndrome AND internal* OR external* OR emotion* OR behav*.

We confined the studies written in English in the fields of psychology, social science, and health but did not impose restrictions on the countries in which the studies were carried out. The inclusion criteria were: (a) participants recruited from the general population; (b) participants aged ≥5 and ≤ 13 years; (c) papers published in peer-reviewed journals; (d) papers published between January 1, 2020 and the end of October 2022; (e) papers based on COVID-19-related effects; and (f) qualitative, quantitative, and mixed study designs. The exclusion criteria were: (a) participants aged ≤ 4 and ≥14 years; (b) papers that did not report the participants' age; (c) papers from other research fields (e.g., medicine; biology); (d) dissertations, conference abstracts and/or papers, editorials, opinions, commentaries, recommendations, letters, books, and book chapters; (e) other systematic and non-systematic reviews; and (f) validation studies.

2.2. Selection of the studies

The PICOS (Bowling and Ebrahim, 2005; Hong et al., 2018) protocol was used to analyze the content of the studies.

Participants: typically developing children aged 5–13 years;

Intervention: studies assessing children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic;

Comparison: Gender differences between symptoms;

Outcomes: levels of children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms; children's psychological determinants associated with the Intervention variables; parental psychological determinants associated with or contributing to the Intervention variables.

Study: quantitative; qualitative; mixed.

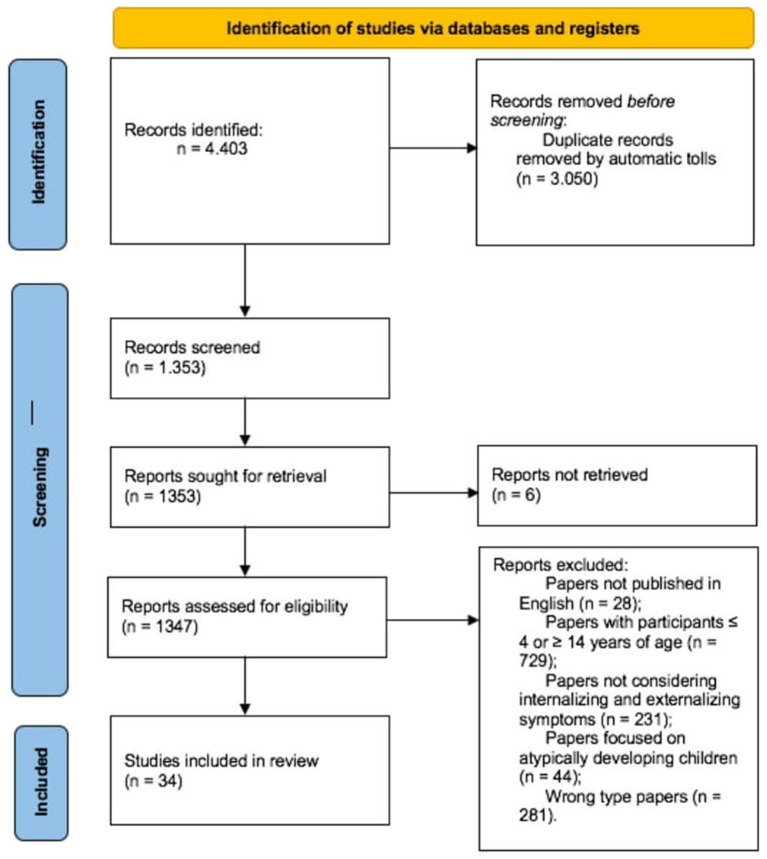

Figure 1 maps the selection process. Following the Identification stage of PRISMA, we searched papers in which our keywords appeared in either the title, abstract, subject heading, or keywords list. Each keyword combination was tabulated in an Excel spreadsheet and 4,403 records were ordered alphabetically. All duplicates (n = 3,050) were removed.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the selected studies.

A total of 1,353 papers were screened for the availability of the full text by two of the present authors (AL & CM); six papers were excluded because the full text could not be retrieved. A total of 1,347 papers were assessed and a total of 1,313 papers were excluded. Figure 1 details the number of papers that were excluded for each criterion. The inter-rater agreement was calculated using a set of 50 randomly selected papers; these were independently screened by AL and CM, and their disagreements were arbitrated by a third author (FL). The inter-rater agreement was good (Cohen's κ = 0.93). Thirty-four papers were included in the final review.

2.3. Quality appraisal

The quality of the papers was evaluated in accordance with the updated standardized Mixed Method Appraisal Tool protocol (MMAT; Hong et al., 2018). This protocol is used to evaluate five principal categories: qualitative studies (via four items), randomized control trials (via four items), non-randomized studies (via four items), quantitative descriptive studies (via four items), and mixed methods studies (via three items). For each category, a set of five questions are provided; a 3-point Likert scale (1 = yes and 0 = no and can't tell) is used to measure responses.

The MMAT comprises a spreadsheet into which the reviewer first inserts the study information (a reference ID number, the first author of the study, the publication year, and the full citation). The reviewer then selects from a drop-down menu the answer (yes vs. no vs. can't tell) to two preliminary screening questions (“Are there clear research questions?” and “Do the collected data allow to address the research questions?”). If no or can't tell are selected, the paper is excluded from the review. If yes is selected, the reviewer answers the five questions pertaining to the category of study.

In the present case, the inter-rater agreement was calculated using a set of 10 randomly selected papers. They were independently evaluated by two authors (AL & CM) and the disagreements were arbitrated by a third (FL). The inter-rater agreement was good (Cohen's κ = 0.95).

To calculate the overall score regarding the quality of α study, the MMAT developers suggest summing up the responses. They do not, however, recommend a cut-off point to categorize the overall score, arguing that reviewers make their own decision. We ranked the papers as low when they were rated as a 1 or 2, medium when they were rated as a 3, and high when they were rated as a 4 or 5.

2.4. Data synthesis

Because the results of the studies were heterogenous, a narrative approach was deemed appropriate. Section 3 herein comprises six parts. First, we provide an overview of the methodological characteristics of the studies (Section 3.1); the next four sections synthesize the findings and address the present study's research questions (Sections 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, and 3.5); and the sixth section summarizes the result of the quality appraisal (Section 3.6).

3. Results

Details of the main studies are tabulated in Table 1. For each study, we extracted the country and the time the data were collected; the overall methodology (i.e., quantitative vs. qualitative vs. mixed studies and cross-sectional vs. longitudinal); the strategies used to recruit the participants (probabilistic vs. non-probabilistic method and the specific strategy used); the method used to collect the data (online vs. face-to-face); and the individuals who completed the survey (parent vs. child). We also reported the sample's characteristics [i.e., the size of the total sample and the sub-samples (when present), gender distribution, mean age, standard deviation, and age range] and the outcome measures administered to evaluate children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms, the psychological determinants that were associated with or contributed to them, and any parent-related psychological determinants.

Table 1.

Methodological characteristics of the included studies and quality appraisal.

| References | Country | Period of data collection | Study designa | Participants | Outcome measuresb | Relevant findings | Study appraisalc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample n (% females) | M (sd); age range | |||||||

| Quantitative studies | ||||||||

| Andrés et al. (2022) | Argentina | n.s. | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (i.e., snowball); online survey; parent/caregiver-report. |

Total sample n = 1,205 (51.5% females). Sub-sample 6–8 yo n = 286 (% gender n.s.). Sub-sample 9–11 yo n = 297 (% gender n.s.). |

Total sample M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 3–18 yo. Sub-sample 6–8 yo M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 6–8 yo. Sub-sample 9–11 yo M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 9–11 yo. |

(1) Child Behavior CheckList (Achenbach and Rescorla, 2014): child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms; Positive and Negative Affect Schedule for Children (Positive Affect Subscale; Laurent et al., 1999): child' positive affect. (3) State-trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger et al., 1999): parent' anxiety; Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck et al., 1996): parent' depression; Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (López-Gómez et al., 2015): parent' affectivity; Ad hoc measure: parent' concerns and worry on COVID-19 infection. |

RQ1 Children aged 6–8 years showed a high level of internalizing (anxiety-depression) and externalizing (impulsivity-inattention; aggression-irritability) symptoms. Children aged 9–11 years showed internalizing (anxiety-depression) and externalizing (aggression-irritability) symptoms. RQ2 Total sample Females > males: internalizing (anxiety and depression symptoms) symptoms; Males > females: externalizing (aggression and irritability) symptoms: Sub-sample 8–9 yo Males > females: dependence-withdrawal. |

Medium |

| Dodd et al. (2022) | Ireland, UK | Irish sample April 3–April 26, 2020 UK sample April 4–April 15, 2020 |

Sub-sample Irish Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (i.e., snowball); online survey; parent-report. Sub-sample UK Quantitative; cross-sectional; probabilistic sampling; online survey; parent-report. |

Sub-sample Irish (Study 1) n = 427 (45% females). Sub-sample UK (Study 2) n = 1,919 (49% females). |

Sub-sample Irish (Study 1) M(sd) = 8.02 (1.98) yo; Age range = 5–11 yo. Sub-sample UK (Study 2) M(sd) = 8.45 (1.99) yo; Age range = 5–11 yo. |

Irish and UK samples (1) Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 2003; Tobia and Marzocchi, 2018): child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms; Positive and Negative Affect Schedule for Children-P (Ebesutani et al., 2012): child' emotional functioning. (2) Children's Play Scale (Dodd et al., 2021): child' play. (3) Kessler-6 (Kessler et al., 2002): parent' distress. |

RQ1 Irish and UK sample Child' internalizing symptoms were negatively associated with play activities; furthermore, low levels of child' internalizing symptoms were associated with low parent' distress levels. No significant associations between considered variables and child externalizing symptoms were found. RQ2 No significant gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were found. Females > males: positive affect. RQ3 The more child play activities involved the more positive effects. |

Irish sample: High UK sample: High |

| Lionetti et al. (2022) | Italy |

T1: January, 2020 T2: April, 2020 |

Quantitative; longitudinal; non-probabilistic sampling (convenience); online survey; parent-report. | n = 94 (55% females). | M(sd) = 9.08 (0.56) yo; Age range: 8–10 yo. | T1 (1) Pediatric Symptoms Checklist (Gardner et al., 1999): child' externalizing symptoms. (2) HSC scale (Pluess et al., 2018): child' environmental sensitivity. T2 (1) Pediatric Symptoms Checklist (Gardner et al., 1999): child' externalizing symptoms; (2) Closeness Scale of the Parent-Child Relationship Scale (Pianta, 1992): quality of parent-child relationship. |

RQ1 Sensitive children showed more internalizing symptoms during the pandemic than before. RQ2 No gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were evaluated. RQ4 A close parent-child relationship moderated the impact of time on child' externalizing symptoms. Furthermore, the close parent-child relationship leads sensitive children to show decreased internalizing symptoms during the pandemic. |

Low |

| Liu et al. (2022) | China | April 23–May 7, 2020. | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (convenience); online survey; self-report. |

Total sample n = 4,852 (51.5% females). Sub-sample 10–12 yo n = 1,524 (49.5% females). |

Total sample M(sd) = 13.80 (2.38) yo; Age range = 10–18 yo. Sub-sample 10–12 yo M(sd) = 10.96 (0.82) yo; Age range = 10–12 yo. |

(1) Chinese version of Self-Rating Depression Scale (Zung, 1965): child' depressive symptoms; Chinese version of Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (Zung, 1971): child' anxiety symptoms. (2) Chinese Internet Addiction Scale-Revised (Chen et al., 2003): child' internet addiction; Chinese version of Athens Insomnia Scale (Soldatos et al., 2000; Chiang et al., 2009): child' insomnia; Chinese version of Utrecht Work Engagement Scale for Students (Schaufeli and Salanova, 2007; Fang et al., 2008): child' academic engagement. |

RQ1 Depression and insomnia, as well as anxiety and insomnia mediated the relationship between problematic internet use and academic engagement. The indirect effects of Internet risk on academic engagement through depression and insomnia in middle and late adolescence were stronger than those in early adolescence; the direct effect in early adolescence was stronger than that in middle adolescence. RQ2 Females > males: internalizing (depression, anxiety) symptoms; Females > males: insomnia. RQ3 The older, female, and non-only children were significantly correlated with higher levels of internalizing (depression, anxiety and insomnia) symptoms. |

High |

| Martiny et al. (2022) | Norway | June 8–July 3, 2020 | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (snowball); online survey; parent and child -report. | n = 87 (51.7% females) | M(sd) = 9.66 (1.77) yo; Age range = 6-13 yo. | (1) How I feel Questionnaire, used with children as young as 8 years of age (Walden et al., 2003): child' internalizing symptoms. (2) Ad hoc measure: child' COVID-19 attitudes; KIDSCREEN-10 (Haraldstad et al., 2006; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2006): child' wellbeing. (3) World Health Organization Index (Topp et al., 2015): parent' wellbeing; Ad hoc measure: parent' stress because of the reopening. |

RQ1 Results show that high levels of child' wellbeing and positive emotions were associated with child' positive attitude toward the COVID-19. RQ2 No gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were evaluated. RQ4 Living with one parent was associated with low child' wellbeing; mother' wellbeing was associated with child' wellbeing and child' negative emotions. |

Low |

| Morelli et al. (2022) | Italy | April, 2020 | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (convenience); online survey; parent-report. | n = 277 (52% females). | M(sd) = 9.66 (2.29) yo; Age range = 6–13 yo. | (1) Emotion Regulation Checklist (Molina et al., 2014): child' emotions regulation. (2) Ad hoc measure: familiar risks related to the family situation during the lockdown, risks related to the COVID-19 pandemic, child' exposure to news related to COVID-19. (3) Modified version of the Television Mediation Scale (Valkenburg et al., 1999): parental mediation of children' exposure to news related to the COVID-19 pandemic. |

RQ1 Results show an increase in anxiety and sadness in children. High level of child' emotion regulation and low level of lability/negativity were associated with parental active mediation style; low level of child' lability/negativity was associated with the parental restrictive style; child' lower emotion regulation was associated with parental social co-viewing style. RQ2 No significant gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were found. RQ3 Early adolescents show a lower level of emotion regulation than younger children. |

Medium |

| Oliveira et al. (2022) | Portugal | June–July, 2020 | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (snowball); online survey; parent-report. | n = 110 (50% females). | M(sd) = 9.09 (0.80) yo; Age range = 7–10 yo. | (1) Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 2003): child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms. (2) KIDSCREEN-10 Index (Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2014): child' quality of life; Q25 Questionnaire (Oliveira et al., 2019): child' daily activities. |

RQ1 Internalizing symptoms were positively correlated with domestic chores and negatively with play. Externalizing symptoms were positively correlated with gaming and negatively with creative leisure and play. Level of engagement in physical activities was positively correlated with psychological and social wellbeing and negatively with internalizing and externalizing symptoms. RQ2 No gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were evaluated. Males > females: physically active; Females > males: engaged in play and social activities. RQ3 There is evidence of high levels of sedentary behavior (time spent on the screen) and low levels of play and recreation, particularly among socioeconomically vulnerable children. |

Low |

| Penner et al. (2022) | USA | February 2–April 4, 2021 |

Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (quota); online survey; parent-reported. |

Total sample n = 796 (42.1% females). Sub-sample 5–8 yo n = n.s. (% gender distribution n.s.). Sub-sample 9–12 yo n = n.s. (% gender distribution n.s.). |

Total sample M(sd) = 10.35 (3.16) yo; Age range = 5–16 yo. Sub-sample 5–8 yo M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 5–8 yo. Sub-sample 9–12 yo M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 9–12 yo. |

(1) Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 2003): child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms. (2) Child Routines Inventory (Daily Living Routines subscale; Sytsma et al., 2001): child' daily routines; Part 1 (Exposures) of the COVID-19 Exposure and Family Impact Survey (Kazak et al., 2021): family COVID-19 exposure. (3) Short Forms of the Patient- Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)-Depression and PROMIS-Anxiety (Pilkonis et al., 2011): parent' current depressive and anxiety symptoms; Short form of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (Elgar et al., 2007): parenting behaviors; Multidimensional Assessment of Parenting Scale (Hostility and Supportiveness subscales; Parent and Forehand, 2017): affective aspects of parenting; Parenting Sense of Competence Scale (Efficacy subscale; Johnston and Mash, 2010): parenting cognitions. |

RQ1 For internalizing and externalizing symptoms, indirect associations occurred through increased parental hostility and inconsistent discipline and decreased parental routines and support. A negative correlation was found between child' internalizing symptoms and levels of positive reinforcement, daily routine, parental support and parental self-efficacy. A negative correlation was found between child' externalizing symptoms and levels of positive reinforcement, daily routine, parental support and parental self-efficacy. RQ2 No gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were found. RQ4 A positive correlation was found between high levels of inconsistent discipline, poor supervision and parental hostility. |

Medium |

| Ravens-Sieberer et al. (2022) | Germany | May 26–June 10, 2020 | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (convenience); online survey; parent–report (sub-sample 7–10 yo); self-report (sub-sample 11–13 yo). |

Total sample n = 1,586 (50% females). Sub-sample 7–10 yo n = 546 (% gender distribution n.s.). Sub-sample 11–13 yo n = 351 (% gender distribution n.s.). |

Total sample M(sd) = 12.25 (3.30) yo; Age range = 7–17 yo. Sub-sample 7–10 yo M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 7–10 yo; Sub-sample 10–13 yo M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 10–13 yo. |

(1) Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 2003): child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms; Selected items from the German version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Barkmann et al., 2008): child' depression symptoms; Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (Birmaher et al., 1999): child' anxiety symptoms. (2) Ad hoc measure: child' burden of the pandemic; KIDSCREEN-10 Index (Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2014): child' quality of life; HBSC symptom check-list (Haugland et al., 2001): child' psychosomatic complaints. |

RQ1 During the pandemic, children experienced high levels of anxiety, hyperactivity symptoms and peer problems. RQ2 Males > females: internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Females > males: externalizing symptoms (only for peer problems subscale). RQ3 During the pandemic, children experienced lower health-related quality of life than before the pandemic. |

Medium |

| Sun et al. (2022) | USA |

T1 Spring, 2019 T2 Spring, 2020 |

Quantitative; longitudinal; non-probabilistic sampling (convenience); T1: data were collected at school; T2: data were collected online. | n = 247 (47% females) | M(sd) = 8.13 (0.46 yo); Age range = 7–9 yo. | T1 (1) Teacher-Child Rating Scale (Perkins and Hightower, 2002): child' pre-pandemic social-emotional skills. T2 (1) Pediatric Emotional Distress Scale (three subscales; Saylor et al., 1999): child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms. (3) Center for the Epidemiological Studies of Depression Short Form (Björgvinsson et al., 2013): parent' depression symptoms; Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7- Item Scale (Spitzer et al., 2006; Löwe et al., 2008): parent' anxiety symptoms; UCLA Loneliness Scale version 3 (Russell, 1996): parent' loneliness; Brief Resilience Scale (Smith et al., 2008): parent' resilience. |

RQ1 Results show that at the beginning of the pandemic, parents reported more children' externalizing symptoms than internalizing ones. Ability in relationships with peers before the pandemic predicted the child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms at pandemic onset. Child' externalizing symptoms were predicted by parental distress. RQ2 No gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were evaluated. |

Low |

| Andrés-Romero et al. (2021) | Spain | Started in the third week of confinement until the sixth week (3 weeks) | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (snowball); online survey; parent-report. |

Total sample n = 1,555 (53.18% females). Sub-sample 6–11 yo n = 353 (% gender distribution n.s.). |

Total sample M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 3–18 yo. Sub-sample 6–11 yo M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 6–11 yo. |

(1) Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 2003): child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms. (2) Ad hoc measure: child' habits of everyday living. (3) Parental Stress Scale (Oronoz Artola et al., 2007): parent' stress; Resilience Scale (Wagnild, 2009): parent' resilience. |

RQ1 High parental resilience levels were associated with low child' difficulties in terms of internalizing and externalizing symptoms. RQ2 No gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were evaluated. RQ3 Parents perceive a change in their child' habits and psychological difficulties. |

Medium |

| Balayar and Langlais (2022) | USA | n.s. | Quantitative; cross-sectional [comparison before (retrospective) and during pandemic]; non-probabilistic sampling (snowball); online survey; parent-report. | n = 80 (50% females). | M(sd) = 8.7 (6.67) yo; Age range = 8–13 yo. | (1) Ad hoc measure: child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms. (2) Ad hoc measure: child' learning performance and psychosocial activities before and during the pandemic. (3) Depression, anxiety, stress scale (Henry and Crawford, 2005): parent' distress. |

RQ1 Internalizing symptoms (withdrawn, anxious, depressed, and stressed) were significantly poorer during the pandemic than before. Regarding the externalizing symptoms, no significant differences before and during the pandemic were found. RQ2 No gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were evaluated. RQ3 Children' learning attainment during the pandemic was significantly predicted by externalizing symptoms. |

Low |

| Bate et al. (2021) | USA | March 31–May 15, 2020 | Quantitative study; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (snowball); online survey; parent-report. | n = 158 (43% females). | M(sd) = 8.73 (2.01) yo; Age range = 6–12 yo. | (1) Pediatric Symptoms Checklist (Jellinek et al., 1999): child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms; Child Revised Impact of Event Scale-13 (Perrin et al., 2005): child' trauma-related symptoms. (2) Child-parent relationship scale (Pianta, 1992): parent-child relationship quality. (3) Ad hoc measure: COVID-19 impact on parent; Patient Health Questionnaire (Spitzer et al., 1999): parent' emotional health; Impact of Events Scale -Revised (Weiss, 2007): parent' evaluation of own distress caused by traumatic events. |

RQ1 Child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms were positively predicted by parent' emotional problems. RQ2 Females > males: internalizing symptoms; Males > females: externalizing symptoms. RQ4 The more conflictual parent-child relationship, the more the child' internalizing symptoms. |

Low |

| Bianco et al. (2021) | Italy | April 1–May 4, 2020 | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (snowball); online survey; parent-report. | n = 305 (49.5% females). |

Females M(sd) = 10.58 (2.3) yo; Males M(sd) = 10.01 (2.4) yo; Age range = 6–13 yo. |

(1) Child Behavior CheckList 6–18 years (Achenbach and Rescorla, 2014): child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms. (3) Ad hoc measure: COVID-19 exposure: parental exposure to COVID-19; Depression Anxiety Stress Scale−21 (Fonagy et al., 2016): parent' distress; Reflective Functioning Questionnaire (Fonagy et al., 2016): parent' reflective function. |

RQ1 Child Internalizing symptoms (anxious/depressed) was associated with high maternal distress level and hypermentalization; child externalizing (attention problems, aggressive behavior) symptoms, were associated with high maternal distress level and hypermentalization. Child internalizing (anxious/depressed) symptoms and externalizing (attention problems, aggressive behavior) symptoms were associated with maternal exposure to COVID-19 infection. RQ2 Females > males: internalizing (anxiety and depression symptoms) symptoms. |

High |

| Cellini et al. (2021) | Italy | April 1–April 9, 2020 | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (snowball); online survey; parent-report. | n = 299 (46% females). | M(sd) = 7.96 (1.36) yo; Age range = 6–10 yo. | (1) Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 2003): child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms. (2) Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (Bruni et al., 1996): child' quality of sleep; Three items from Porcelli et al. (2018) and one item from Zakay (2014): child' time perception. (3) Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (Curcio et al., 2013): mother' quality of sleep; Subjective Time Questionnaire (Mioni et al., 2020): mother' perception of time; Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire−18+ (Goodman, 2003): parent' internalizing and externalizing symptoms (self-reported); Difficulties in Emotion Regulation (Giromini et al., 2012): parent' difficulties in emotional regulation. |

RQ1 Results show an increase in three areas: (1) child' emotional symptoms; (2) child' conduct; (3) child' hyperactivity/inattention. RQ2 Males > females: hyperactivity-inattention, felt more bored; Females > males: poorer sleep. RQ3; RQ4 Low quality of sleep, children increasing boredom and the mother' emotional problems predicted children's emotional symptoms. |

High |

| Khoury et al. (2021) | Canada | T0: 2016–2018; T1: May–November, 2020 | Quantitative; longitudinal; non-probabilistic sampling (convenience); online survey; parent-report. | n = 68 (47.1% females). | M(sd) = 7.87 (0.75) yo; Age range = 7–9 yo. | (1) Brief Problem Monitor-Parent form for ages 6–18 years (Achenbach and Rescorla, 2014): child' externalizing symptoms. (2) Parent Behavior Inventory (Lovejoy et al., 1999): mother' behaviors over the past month; Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Andresen et al., 1994): mother' depressive symptoms over the past week; Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006): mother' anxiety symptoms over the past 2 weeks; Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen, 1998): mother' experiences of stress over the past month. |

RQ1 The results show an increase in internalizing and externalizing symptoms during the pandemic than before. Child' externalizing symptoms were associated with parental hostility; child' internalizing symptoms were associated with maternal anxiety. RQ2 No significant gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were found. |

Low |

| Li and Zhou (2021) | China | February 28–March 5, 2020 | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (snowball); online survey; parent-report. |

Total sample n = 892 (47% females). Sub-sample 5–8 yo n = 647 (46% females). Sub-sample 9–13 yo n = 245 (51% females). |

Total sample M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 5–13 yo. Sub sample 5–8 yo M(sd) = 6.19 (0.99) yo; Age range = 5–8 yo; Sub-sample 9–13 yo M(sd) = 10.81 (1.40) yo; Age range = 9–13 yo. |

(1) Spence Children's Anxiety Scale-Parent Version (Spence, 1999): child' internalizing symptoms; Early School Behavior Rating Scale (Caldwell and Pianta, 1991): child' externalizing symptoms. (2) Ad hoc measure: Family-Based Disaster Education Scale: disaster education provided by parents to their children during COVID-19. (3) Parental Worry Scale (Fisak et al., 2012): parent' worry in relation to their children during COVID-19. |

RQ1 Child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms were associated with parental worry. RQ2 No gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were evaluated. RQ4 For the schoolchildren group only, fewer internalizing symptoms were associated with disaster-based education. |

High |

| Liu et al. (2021) | China | February 25–March 8, 2020 | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (snowball); online survey; parent-report. |

Total sample n = 1,264 (44% females). Sub-sample Huangshi n = 790 (% gender distribution n.s). Sub-sample Wuhan N = 474 (% gender distribution n.s). |

Total sample M(sd) = 9.81 (1.44) yo; Age range = 7–12 yo. Sub-sample Huangshi M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 7–12 yo. Sub-sample Wuhan M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 7–12 yo. |

(1) Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (Du et al., 2008): child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms. (3) Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (Zung, 1971): parent' anxiety symptoms. |

RQ1 Children in Wuhan had more externalizing symptoms (problems with peers) and general difficulties than children in Huangshi. Children aged 10–12 yo had more externalizing symptoms in terms of problems with peers than children aged 7–9 yo. Children aged 7–9 yo had more externalizing symptoms in terms of problems in prosocial behaviors than children aged 10–12 yo. RQ2 Females > males: externalizing symptoms (peer problems). RQ4 Parental anxiety was associated with emotional symptoms in children. |

Low |

| Mariani Wigley et al. (2021) | Italy | May 18–June 4, 2020 | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (snowball); online survey; parent-report. | n = 158 (53% females). | M(sd) = 8.88 (1.41) yo; Age range = 6–11 yo. | (1) Ad hoc measure: child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms (stress-related behaviors, e.g., nervousness and irritability, difficulty falling asleep). (2) Child and Youth Resilience Measure-Revised (Personal Resilience subscale of the Person Most Knowledgeable version; Jefferies et al., 2019): child' individual resources. (3) COPEWithME questionnaire (developed in the study): parental teaching of resilient behaviors in children; Italian version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (Connor and Davidson, 2003): parent' resilience. |

RQ1 Results show an increase in all child' stress-related behaviors (e.g., nervousness and irritability; difficulty falling asleep) investigated. RQ2 No gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were evaluated. RQ4 The greater was parental resilience, the better were the strategies used by parents to teach the child to manage stressful situations. |

Low |

| Orgilés Amorós et al. (2021) | Italy; Spain; Portugal. | Seven weeks after the lockdown (15 days). | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (snowball); online survey; parent-report. |

Total sample n = 515 (46% females). Sub-sample 6–12 yo n = 233 (gender distribution n.s.). |

Total sample M(sd) = 8.98 (4.29) yo; Age range = 5–18 yo. Sub-sample 6–12 yo M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 6–12 yo. |

(1) Spence Children's Anxiety Scale-Parent Version (Spence, 1999): child' anxiety symptoms; Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire-Parent Version (Angold et al., 1995): child' depressive symptoms. (2) Ad hoc measure: parent' stress due to the COVID-19 situation. |

RQ1 The results show a high level of anxiety and depression in Spain. Italian children were more likely to present internalizing symptoms (depressive symptoms) than the Portuguese children. Internalizing symptoms (anxiety and depressive symptoms) were more likely in children whose parents reported higher levels of stress. RQ2 No gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were evaluated. |

Low |

| Rajabi et al. (2021) | Iran | n.s. | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (snowball); online survey; parent-report. | n = 1,182 (44.5% females). | M(sd) = 7.18 (2.02) yo; Age range = 5–11 yo. | (1) Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire–Parent version (Goodman, 2003): child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms; The International Positive and Negative Affect Schedule Short Form (Thompson, 2007): child' positive and negative affect. (2) Children's Play Scale (Dodd et al., 2021): child' time spent playing. |

RQ1 Results show a significant negative correlation between mental health difficulties (internalizing and externalizing symptoms and positive and negative affect) and time spent playing. RQ2 Total sample Males > females: negative affect; Females > males: positive affect. Sub-sample 5–10 yo Males > females: Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire total score, emotional symptoms, hyperactivity/inattention subscales; Females > males: prosocial behavior subscale. Sub-sample 8–11 yo Males > females: emotional symptoms, hyperactivity/inattention, conduct problems, general problems subscales. Females > males: problems with peers and prosocial behavior subscales. RQ3 During COVID-19 children spent more time playing in the home setting and less time playing outdoors. |

High |

| Scaini et al. (2021) | Italy | n. s. | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (snowball); online survey; parent-reported. | n = 158 (52% females). | M(sd) = 7.4 (1.8) yo; Age range = 5–10 yo. | (1) Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 2003): child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms. (2) The Child and Youth Resilience Measure—Person Most Knowledgeable version (Ungar and Liebenberg, 2011): child' resilience; Junior Temperament and Character Inventory (Luby et al., 1999; Italian Version by Andriola et al., 2012): child' temperament and character. |

RQ1 Child' externalizing symptoms were associated with low levels of persistence and reward dependence; internalizing symptoms were more likely among children with high harm avoidance and low persistence. RQ2 No significant gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were found. RQ3 High levels of resilience were associated with high levels of persistence and reward dependence. |

Low |

| Vira and Skoog (2021) | Sweden | T1: October 2019–January, 2020; T2: November 2020–February, 2021. |

Quantitative; longitudinal; non-probabilistic sampling (convenience); T1: data were collected at school; T2: data were collected via online survey; self-report. |

N = 849 (51.83% females). |

T1 M(sd) = 10 (0.03) yo; Age range = 9–11 yo. T2 M(sd) = 11 (0.05) yo; Age range = 10–12 yo. |

(1) Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (subscale of emotional problems; Lundh et al., 2008): child' internalizing symptoms. (2) The Children's Hope Scale (Snyder et al., 1997): child' sense of hope; Ad hoc measure: Children's Self-Efficacy Scale: child' ability to be assertive and expressive; The Single-Item Self-Esteem Scale (SISE; Robins et al., 2001): child' self-esteem; Perceived Social Support (parents, close friends and teacher subscales; Malecki and Elliott, 1999): child' perceived social support; Ad hoc measure: child' school and class wellbeing. |

RQ1 There were no significant differences in children' internalizing symptoms between T1 and T2. RQ2 No significant gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were found. RQ3 The results show a decrease in all factors assessed, in particular, children' perceived low support from teachers and class; low school wellbeing and self-esteem. |

Medium |

| Wang et al. (2021a) | China | June 26–July 6, 2020 | Quantitative; cross-sectional; probabilistic sampling (cluster method); online survey; parent-report. | N = 6,017 (45.4% females). | M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 5–13 yo. | (1) Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 2003): child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms. (2) Ad hoc measure: child' knowledge and precaution levels regarding COVID-19. (3) Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (Henry and Crawford, 2005): parent' distress; Ad hoc measure: parent' knowledge and precaution levels regarding COVID-19. |

RQ1 Few child' emotional and behavioral symptoms were associated with increased knowledge and precautions regarding COVID-19 pandemic. Child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms were associated with parent' distress. RQ2 Males > females: Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire total score. |

High |

| Wang et al. (2021c) | China | May 20–July 20, 2020 | Quantitative; cross-sectional; probabilistic sampling (cluster method); online survey; parent-report. |

Total sample n = 12,186 (47.8% females). Sub-sample Wuhan 6–11 yo n = n.s. (% gender distribution n.s.). Sub-sample outside Wuhan 6–11 yo n = n.s. (% gender distribution n.s.). |

Total sample M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 6–11 yo. Sub-sample Wuhan 6–11 yo M(sd) = 9.3 (1.43) yo; Age range = 6–11 yo. Sub-sample outside Wuhan 6–11 yo M(sd) = 9.1 (1.33); Age range = 6–11 yo. |

(1) Child Behavior CheckList (Achenbach and Rescorla, 2014): child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms. (2) Ad hoc measure: psychosocial impact of pandemic on child. |

RQ1 Children from Wuhan reported higher levels of schizoid and depression than children from outside Wuhan. RQ2 No significant gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were found. |

High |

| Wang et al. (2021b) | China | June 26–July 6, 2020 | Quantitative; cross-sectional; probabilistic sampling (cluster method); online survey; parent-report. | n = 6,017 (% gender distribution n.s.). | M(sd) = n.s. Age range = 5–13 yo. | (1) Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (Stone et al., 2010): child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms. (2) Ad hoc measure: child' psychological stressors, daily activities, social interactions. |

RQ1 The prevalence of externalizing symptoms (low prosocial behavior) was 17.85%. RQ2 Males > females: Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire total score. RQ3 Time used in homework and computer games was positively related to child' mental health problems; child' physical exercises were negatively related to frequency of communication with others. |

Medium |

| Duan et al. (2020) | China | n.s. | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (convenience); online survey; self-report. |

Total sample n = 3,613 (49.85% females). Sub-sample 7–12 yo n = 359 (% gender distribution n.s) |

Total sample M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 7–18 yo. Sub-sample 7–12 yo M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 7–12 yo. |

(1) Chinese Version of Spence Child Anxiety Scale (Zhao et al., 2012): child' anxiety symptoms; The Child Depression Inventory (Kovacs and Beck, 1977): child' depression symptoms. (2) Ad hoc measure: COVID-19 related questions (e.g., degree of concerns, implementation of control measures); Short Version of Smartphone Addiction Scale (Kwon et al., 2013) and Internet Addiction Scale from DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000): child' smartphone addiction; Coping Style Scale (Chen et al., 2000): child' coping strategies. |

RQ1 The results show above-threshold results for depressive symptoms. RQ2 Females > males: internalizing (anxiety symptoms) symptoms. RQ3 The results show above-threshold results for internet addiction. The more time spent on the Internet, the higher the level of depressive symptoms. |

Medium |

| Liang et al. (2020) | Italy | March 26–April 12, 2020 | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (snowball); online survey; parent-report. | n = 1,074 (48% females) | M(sd) = 8.99 (1.97) yo; Age range = 6–12 yo. | (1) Impact Scale of the COVID-19 and home confinement on children and adolescents (Orgilés et al., 2020): child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms. (2) 11 items included the three dimensions proposed by Parker and Endler (Parker and Endler, 1992): child' coping strategies. |

RQ1 The results show that children from Northern Italy were scared and they had greater fear of death than children from Central Italy. No significant differences regarding internalizing and externalizing symptoms between children from Northern and Central Italy were found. RQ2 No gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were evaluated. RQ3 Regarding coping strategies, children from Northern Italy used emotion-oriented coping strategies, while children from Central Italy used task-oriented coping strategies. |

Medium |

| Morelli et al. (2020) | Italy | April, 2020 | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (snowball); online survey; parent-report. | n = 233 (52% females). | M(sd) = 9.66 (2.29) yo; Age range = 6–13 yo. | (1) Emotion Regulation Checklist (Molina et al., 2014): child' emotions regulations. (2) Ad hoc measure: familiar risks related to the family situation during the COVID-19 pandemic. (3) Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., 1983); Italian validation by Mondo et al. (2021): parent' distress; Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy Scale (Caprara et al., 2013): parental belief to be able to manage with their negative emotions; Parenting Self-Agency Measures (Dumka et al., 1996; Baiocco et al., 2017): parental belief to be able to manage with daily parental demands. |

RQ1 Parental self-efficacy mediated the relationship between the influences of parent' psychological distress and parent' emotional regulatory self-efficacy on children' emotional regulation and lability/negativity. RQ2 No significant gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were found. |

Medium |

| Petrocchi et al. (2020) | Italy | April 1–May 4, 2020 | Quantitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (snowball); online survey; parent-report. | n = 144 (43% females). | M(sd) = 7.54 (1.6) yo; Age range = 5–10 yo. | (1) Ad hoc measure: child' internalizing symptoms (emotional responses); Ad hoc measure: child' adaptive behaviors. (2) Ad hoc measure: mother' exposure to COVID-19. (3) Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-−21 (Fonagy et al., 2016): mother' distress; Coping Scale (Hamby et al., 2015): mother' coping strategies. |

RQ1 Child' internalizing symptoms (negative emotions) were associated with high maternal distress and low maternal coping strategies. RQ2 No gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were evaluated. RQ4 Mothers exposed to COVID-19 infection showed high distress levels and more coping strategies than mothers not exposed to virus infection. |

Medium |

| Qualitative studies | ||||||||

| Aras Kemer (2022) | Turkey | n.s. | Qualitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (snowball); online survey; self-reported. | n = 9 (66% females). | M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 7–10 yo. | (1) Ad hoc measure: child' anxiety evaluated via drawings and interviews. |

RQ1 Drawings and interviews revealed internalizing symptoms (anxiety, negative emotions). RQ2 No gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were evaluated. RQ3 Results showed limited knowledge of the COVID-19 pandemic in children. |

High |

| Cortés-García et al. (2021) | USA | May, 2020 | Qualitative; cross-sectional; probabilistic sampling (random); online focus group; self-report. |

Total sample n = 17 (52.9% females). Sub-sample 10–12 yo n = 9 (44.44% females). |

Total sample M(sd) = n.s; Age range = 10–14 yo. Sub-sample 10–12 yo M(sd) = n.s; Age range = 10–12 yo. |

(1) Ad hoc measure: semi-structured interview about child' emotional responses and coping strategies during pandemic. |

RQ1 The results were mixed. On the one hand, children experienced positive feelings such as happiness (spending more time with parents, more free time and to play), on the other hand, children experienced negative feelings such as loneliness, sadness, boredom and fear (due to lack of socialization with friends and other family members). RQ2 No gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were evaluated. RQ3, RQ4 Other revealed themes were perception of racism, perception of economic impact and information related to COVID-19, quality of relationships in the family, use of coping strategies. |

High |

| Idoiaga et al. (2020) | Spain | March 30–April 13, 2020 | Qualitative; cross-sectional; non-probabilistic sampling (convenience); online open-ended questions; self-report. |

Total sample n = 228 (52.21% females). Sub-sample 3–12 yo n = n.s. (% gender distribution n.s.). |

Total sample M(sd) = 7.14 (2.57) yo; Age range = 3–12; Sub-sample 3–12 yo M(sd) = n.s. Age range = 6–12 yo. |

(1)Ad hoc measure: open-ended questions about child' social and emotional representation of COVID-19. |

RQ1 Results were mixed. On the one hand, they say they are bored, angry, overwhelmed, tired and even lonely because they have to stay at home without being able to go out. On the other hand, they also say they are happy and cheerful in the family. RQ2 No gender differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms were evaluated. RQ3 Parents identified sibling relationship as particularly positive. Also, a disturbed sleep routine is reported. |

Low |

| Mixed study | ||||||||

| Wenter et al. (2022) | Austria |

T1: March/April, 2020 T2: December 2020/ January, 2021 T3: June/July, 2021 T4: December 2021/ January 2022. |

Mixed study (convergent design); longitudinal; non-probabilistic sampling (convenience); online survey; parent-report. |

Total sample n = 2.691 (48.8% females). Sub-sample 7–13 yo n = 1,740 (49.8% females). |

Total sample M(sd) = n.s.; Age range = 3–13 yo. Sub-sample 7–13 yo M(sd) = 9.6 (1.9) yo; Age range = 7–13 yo. |

(1) Child and Adolescent Trauma screen—caregiver report (Sachser et al., 2017): child' risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (Quantitative study); Child Behavior CheckList (Achenbach and Rescorla, 2014): child' internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Quantitative study); Kiddy-KINDL (Ravens-Sieberer and Bullinger, 2000): child' quality of life (Quantitative study). (2) Ad hoc measure: parent' evaluation of child exposure to COVID-19 infection (Quantitative study); Ad hoc measure: parent' evaluation of child' threat experience of COVID-19 (Quantitative study). (3) Ad hoc open-ended questions: parent description on the positive effects related to the COVID-19 pandemic (Qualitative study). |

RQ1 Quantitative results: Data collected during the T4 wave showed a clinical classification of internalizing (emotional reactivity, anxious/depressed; somatic complaints; withdrawn/depressed) and externalizing (aggressive behaviors) symptoms. Qualitative results: Thematic analysis showed that the themes were: importance of intra- and extra-familiar relationships; new competence and experiences; values and virtues; use of time; and family strengths. RQ2 Males > females: externalizing (aggressive behaviors) symptoms. RQ3 Threat experience increased internalizing and externalizing symptoms, post-traumatic symptoms, and low quality of life. |

Medium |

aStudy design (Qualitative vs. quantitative vs. mixed study) (cross-sectional vs. longitudinal); sampling strategy; data collection strategy (online vs. face-to-face); respondent (parent- vs. self-report).

bMeasures: (1) measure(s) administered to evaluate the child' internalizing/externalizing symptoms; (2) measure(s) administered to evaluate other(s) child' psychological factor(s); (3) measure(s) administered to evaluate parent(s) psychological factor(s).

cStudy appraisal: * and ** = low; *** = medium; **** and ***** = high.

n.s, not specified.

* and ** mean that the quality of the paper is low; *** means that the quality of the paper is medium; **** and ***** mean that the quality of the paper is high.

We then summarized the relevant findings of each study and organized them according to the research questions. We reported the main results (RQ1), the psychological determinants (RQ2), gender differences (RQ3), and the parental role (RQ4). In the last column of Table 1, we report the quality appraisal for each study (low vs. medium vs. high) based on the MMAT protocol.

3.1. Methodological characteristics

A total of 34 studies were included in this systematic mixed studies review. They derived from 15 countries across three Continents (Europe, America, and Asia). The majority (n = 18) were European, nine were Asian, and seven were American (n = 6 North America; n = 1 South America). Table 1 is structured according to the category of the research design: quantitative (n = 30), qualitative (n = 3), and mixed studies (n = 1).

Except for five quantitative studies (Duan et al., 2020; Rajabi et al., 2021; Scaini et al., 2021; Andrés et al., 2022; Balayar and Langlais, 2022) and one qualitative study (Aras Kemer, 2022), the papers provided information on when the data were collected. Most of them were quantitative and collected data during the first 7 months of 2020 (Liang et al., 2020; Morelli et al., 2020, 2022; Petrocchi et al., 2020; Andrés-Romero et al., 2021; Bate et al., 2021; Bianco et al., 2021; Cellini et al., 2021; Li and Zhou, 2021; Liu et al., 2021, 2022; Mariani Wigley et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021a,b,c; Dodd et al., 2022; Lionetti et al., 2022; Martiny et al., 2022; Oliveira et al., 2022; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2022), as did the qualitative studies (Idoiaga et al., 2020; Cortés-García et al., 2021). One quantitative study (Penner et al., 2022) collected data during the first months of 2021 (February–April).

Most of the papers applied a cross-sectional quantitative study design (n = 27); three collected longitudinal quantitative data. All three qualitative studies were cross-sectional. The mixed study applied a longitudinal design for the quantitative section and used cross-sectional data for the qualitative section. Of the four longitudinal studies (Khoury et al., 2021; Vira and Skoog, 2021; Sun et al., 2022; Wenter et al., 2022), three (Khoury et al., 2021; Vira and Skoog, 2021; Sun et al., 2022) compared data collected before and during the pandemic. Lionetti (Lionetti et al., 2022) collected data in January 2020 and April 2020. Sun et al. (2022) compared data collected during Spring 2019 and Spring 2020. Khoury et al. (2021) compared data collected during 2016–2018 with those collected during May–November 2020. The mixed study included data collected during four pandemic waves between 2020 and 2022 (Table 1).

Eighty-five percent of the studies (n = 26 quantitative studies; n = 2 qualitative studies; n = 1 mixed study) recruited participants using non-probabilistic sampling strategies. The remaining studies (n = 4 quantitative studies; n = 1 qualitative study) used probabilistic strategies (Table 1).

As expected, because of the COVID-19 restrictions, all the studies collected data remotely, inviting participants to complete an e-survey disseminated through the main social platforms and/or mailing lists. Only two longitudinal studies (Vira and Skoog, 2021; Sun et al., 2022) collected data face-to-face (before the pandemic) and online (during the pandemic).

Most of the study questionnaires (n = 27) were completed by a parent or caregiver; two (Martiny et al., 2022; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2022) were completed by both parents and children; and five (Duan et al., 2020; Idoiaga et al., 2020; Cortés-García et al., 2021; Vira and Skoog, 2021; Aras Kemer, 2022) were completed by the children. A total of 40,976 participants were enrolled on the studies. For the 30 quantitative studies, the total sample ranged between 80 and 12,186 participants; for the three qualitative studies, it ranged between 9 and 228. The mixed study involved 2,691 participants.

It is worth noting that the majority of the studies enrolled children from a wider age range (e.g., 5–18). Because the present study is focused on middle childhood (i.e., children aged 5–13), we extrapolated information regarding the size of the sub-group(s). In the quantitative studies, the sub-groups varied from 233 to 1,919 participants; two of the qualitative studies divided the total sample into sub-groups, and only one reported the number (n = 9). The sub-group in the mixed study comprised 1,740 participants.

We extracted information on the gender distribution percentage for each study. The majority of the quantitative studies (n = 21) reported the gender distribution percentage for both the total and sub-groups (where applicable); eight studies (Andrés-Romero et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; Orgilés Amorós et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021b; Andrés et al., 2022; Penner et al., 2022; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2022) reported the gender percentage for the total sample only. One study (Wang et al., 2021c) did not report the gender distribution. All the quantitative studies were balanced, as was the mixed study. Two qualitative studies (which were similarly balanced) provided detailed information on gender, while one study (Idoiaga et al., 2020) did not offer any.

We also calculated the participants' mean age, standard deviations, and age range(s), though this was not possible for six quantitative studies (Duan et al., 2020; Andrés-Romero et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021a,b,c; Andrés et al., 2022) because the necessary information was not available. Of the quantitative studies that split the total samples into sub-groups, seven did not report the above details (Duan et al., 2020; Andrés-Romero et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; Orgilés Amorós et al., 2021; Andrés et al., 2022; Penner et al., 2022; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2022). Three of the qualitative studies (Idoiaga et al., 2020; Cortés-García et al., 2021; Aras Kemer, 2022) did not report the participants' ages. Finally, the mixed design study authors did not provide the mean ages and the standard deviations of the total sample, though they did for the sub-samples.

Table 1 displays information on the measures administered by the authors of the studies. We filed the outcome measures according to the psychological construct(s): the measure(s) assessing children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms; the tool(s) evaluating the children's psychological determinant(s); and the measure(s) assessing the parent-related psychological determinants(s). For each measure, we point out the full name, reference, and the psychological construct that was evaluated.

The majority of the quantitative studies applied validated measures; most applied the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 2003). Three papers (Petrocchi et al., 2020; Mariani Wigley et al., 2021; Balayar and Langlais, 2022) applied non-validated measures. To evaluate the children's psychological determinant(s), 11 (Liang et al., 2020; Bate et al., 2021; Cellini et al., 2021; Mariani Wigley et al., 2021; Rajabi et al., 2021; Scaini et al., 2021; Dodd et al., 2022; Lionetti et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2022; Oliveira et al., 2022; Penner et al., 2022) applied validated measures only, nine (Morelli et al., 2020, 2022; Petrocchi et al., 2020; Andrés-Romero et al., 2021; Li and Zhou, 2021; Wang et al., 2021a,b,c; Balayar and Langlais, 2022) applied non-validated measures only, and four (Duan et al., 2020; Vira and Skoog, 2021; Martiny et al., 2022; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2022) applied validated and non-validated measures. To evaluate parental psychological determinants, 25 applied validated measures, five (Bate et al., 2021; Bianco et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021a; Andrés et al., 2022; Martiny et al., 2022) used both validated and non-validated measures, and one (Orgilés Amorós et al., 2021) applied a non-validated measure. All of the qualitative studies assessed children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms using non-validated measures; the children's and parents' psychological determinants were not evaluated. Finally, the mixed study applied validated measures to evaluate children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms and non-validated measures to assess children's and parent's psychological determinants.

3.2. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms

The present section addresses RQ1. As Table 1 shows, one study (Wang et al., 2021c) estimated that 17.85% of participants were above the threshold for externalizing symptoms only. The longitudinal studies revealed that the levels of both internalizing (Khoury et al., 2021; Lionetti et al., 2022) and externalizing (Khoury et al., 2021) symptoms were higher during the pandemic than they were previously. One longitudinal study (Sun et al., 2022) reported that the levels of externalizing symptoms were higher than internalizing ones during the pandemic. Only one study (Vira and Skoog, 2021) found no difference before and during the pandemic. The quantitative cross-sectional studies reported high levels of internalizing (Duan et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2020; Cellini et al., 2021; Orgilés Amorós et al., 2021; Andrés et al., 2022; Morelli et al., 2022; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2022) and externalizing (Cellini et al., 2021; Mariani Wigley et al., 2021; Andrés et al., 2022; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2022) symptoms compared with the threshold. By contrast, one study (Balayar and Langlais, 2022) reported low levels of both types of symptoms during the pandemic compared with the period before. The qualitative studies generated mixed results. Two suggested that children experienced low (Idoiaga et al., 2020; Cortés-García et al., 2021) levels of internalizing symptoms, while one (Aras Kemer, 2022) suggested the opposite. Finally, the quantitative results of the longitudinal mixed study demonstrated clinical scores (i.e., over the threshold) for internalizing and externalizing symptoms. The qualitative data of the mixed study did not focus on children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

3.3. The psychological determinants associated with or contributing to children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms

The present section addresses RQ2. We analyzed the associations between children's internalizing/externalizing symptoms and their relevant psychological determinant(s). Several quantitative studies demonstrated that high levels of children's internalizing (Petrocchi et al., 2020; Rajabi et al., 2021; Oliveira et al., 2022) and externalizing symptoms (Rajabi et al., 2021; Oliveira et al., 2022) were associated with low engagement during play activities. Furthermore, more widespread use of the internet during the pandemic led to high levels of internalizing symptoms (Duan et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2022). The qualitative studies did not examine this issue. The mixed studies revealed that the constant recommendations and restrictions imposed during the lockdowns increased children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

3.4. Gender differences between children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms

The present section addresses RQ3. The 30 quantitative studies reported mixed findings. Some studies (Duan et al., 2020; Bate et al., 2021; Bianco et al., 2021; Andrés et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2022) found that female children reached higher levels of internalizing symptoms than their male peers, with only two studies (Wang et al., 2021a,c) showing the opposite. Three studies (Bate et al., 2021; Rajabi et al., 2021; Andrés et al., 2022) reported that male children showed more externalizing symptoms than their female peers. One study (Liu et al., 2021) indicated that female children reached higher levels of externalizing symptoms than males. Six studies (Morelli et al., 2020, 2022; Scaini et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021b; Dodd et al., 2022; Penner et al., 2022) observed no difference, and 10 studies (Liang et al., 2020; Petrocchi et al., 2020; Andrés-Romero et al., 2021; Li and Zhou, 2021; Mariani Wigley et al., 2021; Orgilés Amorós et al., 2021; Balayar and Langlais, 2022; Martiny et al., 2022; Oliveira et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2022) did not investigate gender.

These included the qualitative studies. Finally, the quantitative findings of the mixed study revealed that male children showed more externalizing symptoms than females. The qualitative findings of the study did not examine gender differences.

3.5. Parental psychological determinants influencing children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms

The present section addresses RQ4. The 30 quantitative studies examined the associations between parental psychological determinants and children's internalizing/externalizing symptoms. They concluded that several parental psychological determinants, for example, distress (Petrocchi et al., 2020; Bianco et al., 2021; Orgilés Amorós et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021a; Andrés et al., 2022), hostility (Cellini et al., 2021), and emotional difficulties (Bate et al., 2021; Cellini et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021) affected their children's internalizing symptoms. In addition, parental self-efficacy, inconsistent discipline (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), conflictual parent–child relationships (Bate et al., 2021), hypermentalizing (Walden et al., 2003), worries (Li and Zhou, 2021), and poor ability to cope with stressful situations (Petrocchi et al., 2020) were negatively associated with children's internalizing symptoms. Similarly, high hostility and inconsistent discipline (Penner et al., 2022), low self-efficacy (Penner et al., 2022), emotional problems (Bate et al., 2021; Cellini et al., 2021), high distress and problems with hypermentalizing (Bianco et al., 2021), and low parental resilience were associated with children's externalizing symptoms.

The results of the quantitative longitudinal studies emphasized that positive and non-conflictual parent–child relationships moderated the degree of change in externalizing symptoms (Lionetti et al., 2022). The results also stressed that children's externalizing symptoms were predicted by parental distress (Sun et al., 2022) and that they were associated with parental hostility (Khoury et al., 2021). One study (Khoury et al., 2021) showed that internalizing symptoms were associated with maternal anxiety. Finally, the qualitative and mixed studies did not consider the influence of parental psychological determinants on children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

3.6. Quality appraisal

The quality appraisal of the studies using the MMAT protocol concluded that they were either low (n = 12), medium (n = 12), or high (n = 10). As was pointed out in Section 2.3, the quality of each study was regarded as low when it was rated as a one or two, medium when it was rated as a three, and high when it was rated as a four or five. The details of each study appraisal are tabulated in Table 2 (It should be noted before proceeding that the MMAT protocol takes a rather conservative approach to quality appraisal).

Table 2.

Details of the quality appraisal of the reviewed studies.

| Screening questions | Items | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| References | S1. Are there clear research questions? | S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? | 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? | 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? | 4.4. Is the risk of non-response bias low? | 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | Quality appraisal |

| Quantitative studies | ||||||||

| Andrés et al. (2022) | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Medium |

| Dodd et al. (2022) (Irish sample) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Dodd et al. (2022) (UK sample) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Lionetti et al. (2022) | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Can't tell | No | Low |

| Liu et al. (2022) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Martiny et al. (2022) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Medium |

| Morelli et al. (2022) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Medium |

| Oliveira et al. (2022) | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Low |

| Penner et al. (2022) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | Medium |

| Ravens-Sieberer et al. (2022) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Medium |

| Sun et al. (2022) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Low |

| Andrés-Romero et al. (2021) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Medium |

| Balayar and Langlais (2022) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Can't tell | Can't tell | Yes | Low |

| Bate et al. (2021) | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Low |

| Bianco et al. (2021) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Cellini et al. (2021) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Khoury et al. (2021) | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Low |

| Li and Zhou (2021) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Liu et al. (2021) | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Low |

| Mariani Wigley et al. (2021) | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Low |

| Orgilés Amorós et al. (2021) | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Can't tell | No | Low |

| Rajabi et al. (2021) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Medium |

| Scaini et al. (2021) | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Low |

| Vira and Skoog (2021) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Medium |

| Wang et al. (2021a) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Wang et al. (2021c) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Wang et al. (2021b) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Can't tell | Yes | Low |

| Duan et al. (2020) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Medium |

| Liang et al. (2020) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Medium |

| Morelli et al. (2020) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Petrocchi et al. (2022) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Medium |

| 1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | 1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | 1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | 1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | 1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | Quality appraisal | |||

| Qualitative studies | ||||||||

| Aras Kemer (2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Cortés-García et al. (2021) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Idoiaga et al. (2020) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Low |

| Mixed studies | ||||||||

| Wenter et al. (2022) | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Qualitative study | 1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | 1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | 1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | 1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | 1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | |||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Quantitative study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? | 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? | 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? | 4.4. Is the risk of non-response bias low? | 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | |||

| No | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | ||||

| Mixed study | 5.1. Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed methods design to address the research question? | 5.2. Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? | 5.3. Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? | 5.4. Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? | 5.5. Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? | Quality appraisal | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Medium | |||

First, the quantitative studies. Item 1 focuses on sampling strategy. As was expected, the preferred choice for the MMAT protocol is probabilistic sampling. For the quantitative studies, 28 used the main non-probabilistic sampling strategies; two (Wang et al., 2021a,c) did not. Item 2 examines whether the sample enrolled for a study is representative of the target population. The majority of the studies (n = 22) met the representativeness criteria proposed by the MMAT protocol (e.g., a clear description of any attempt to achieve the enrolled sample of participants represents the target population). Item 3 evaluates whether the measurements administered in a study are adequate to answer the research question(s). The majority of the studies (n = 24) applied appropriate, validated, and gold-standard measures. Item 4 assesses the risk of non-response bias. Just over one third of the studies (n = 11) met the criterion. In other words, they had a low non-response rate and/or they used statistical compensation for non-responses (e.g., the imputation method). Finally, Item 5 indicates whether the statistical plan is appropriate for answering the research question(s). All the studies, with the exception of two (Orgilés Amorós et al., 2021; Lionetti et al., 2022), clearly stated the statistical plan and adequately computed their analysis of the design and research question(s). The overall quality appraisal of the quantitative studies was low and medium in 11 cases and high in eight cases.