Abstract

The complex pathological mechanisms of autoimmune diseases have now been discovered and described, including interactions between innate and adaptive immunity, the principal cells of which are neutrophils and lymphocytes. Neutrophil-to–lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was proposed as a biomarker for inflammation that reflects the balance between these aspects of the immune system. NLR is widely studied as a prognostic or screening parameter in quantity diseases with important inflammatory components such as malignancies, trauma, sepsis, critical care pathology, etc. Although there are still no consensually accepted normal values for this parameter, there is a proposal to consider an interval of 1–2 as a normal value, an interval of 2–3 as a grey area indicating subclinical inflammation and values above 3 as inflammation.

On the other hand, several studies have been published indicating that a particular morphological type of neutrophils, low-density neutrophils (LDNs), play a pathological role in autoimmune diseases. Probably, the LDNs detected in patients with different autoimmune diseases, mostly than normal density neutrophils, are involved in the suppression of lymphocytes through different pathways: inducing of lymphopenia through neutrophil depending overproduction of type I interferon (IFN)-α/β and direct suppression by a hydrogen-peroxide-dependent mechanism. Their functional features involvement in IFN production is of particular interest. IFN is one of the critical cytokines in the pathogenesis of many autoimmune diseases, primarily systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). An interesting and important feature of IFN involvement in the pathogenesis of SLE is not only to be directly related to lymphopenia but also its role in the inhibition of the production of C-reactive protein (CRP) by hepatocytes. The CRP is the primary acute phase reactant, which in SLE often does not correlate with the extent of inflammation. NLR in such a case can be an important biomarker of inflammation. The study of NLR as a biomarker of inflammation also deserves attention in other diseases with established interferon pathways, as well as in hepatopathies, when CRP does not reflect the proper inflammation activity. Also, it may be interesting to study its role as a predictor of relapses in autoimmune diseases.

Keywords: Neutrophils, Neutrophil–to–lymphocyte ratio, Low-density neutrophils, Type I interferons, Neutrophil extracellular traps

1. Introduction

Ever since Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov described phagocytosis in 1884, neutrophils have been considered the first line of defence of the innate immune system. These polymorphonuclear leukocytes are the most abundant cell type in the blood; they act as surveillance cells in search of possible infectious or inflammatory processes and are short-lived but very efficient at destroying invading pathogens [1].

Today it is known that neutrophils being principal cells of innate immunity, are also lead actors and regulators of an adaptive immune response interacting with all classes of lymphocytes, modulating their effector functions [2].

Neutrophils have been studied to determine their morphology, functions, and phenotype [3].

Determining the heterogeneity of neutrophils and their pathophysiological role in different mechanisms of tissue damage is important for identifying new therapeutic targets to mitigate inflammation. Neutrophils are important producers of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and are involved in the production of type I IFNs via stimulation of plasmatic dendritic cells (pDC) by chromatin and immune complexes released with NETosis [4]. Type I IFNs are cytokines involved principally in antiviral immunity; however, also they are crucial players in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and many other autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases [5,6]. The therapeutic benefit of inhibiting the IFN pathway in patients with lupus has recently been demonstrated [7,8]. Neutrophils can both stimulate an exaggerated B-cell immune response as well as inhibit it [9].

These functions are mainly attributed to low-density neutrophils (LDNs). LDNs are neutrophils that remain in the fraction of peripheral blood mononuclear cells after density gradient separation [10].

On the other hand, an increasing number of studies described the feasibility of determining the NLR as a screening or prognostic inflammatory biomarker for almost all pathologies with a significant inflammatory component. Furthermore, the NLR is attractive for investigators due to its simplicity. Therefore, this review analyses the complex autoimmune processes that probably stay behind NLR and shows its usefulness in autoimmune diseases.

2. Characteristics of Low–Density neutrophils

Initially described by Hacbarth and Kajdacsy-Balla as “low buoyant density granulocytes” in patients with SLE, their presence correlated with disease activity [11].

Denny et al. developed a technique that demonstrated that adult patients with SLE had LDNs, and that patients with a higher number of these cells in the bloodstream had a higher prevalence of skin damage and vasculitis [12].

LDNs with a normal density neutrophil (NDN) morphology were also recently detected in small amounts in the blood of healthy individuals. Compared to an NDN, these cells show enhanced production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and increased phagocytic capacity, with a similar ability to produce neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) [13] and also higher capacity to suppress T-cell proliferation [14]. However, another study found no morphological or functional differences between low- and high-density neutrophils in healthy individuals, and the researchers could generate a population of LDNs from NDNs in vitro by activating the latter with tumour necrosis factor, lipopolysaccharide, or N-formyl methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine [15].

LDNs displayed by SLE patients, compared with control NDN, have enhanced capacity to synthesize type I IFNs in vitro upon stimulation by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor or polyinosinic: polycytidylic acid. Their phagocytic capacity is diminished, but their ability to form NETs is increased [16]. Furthermore, LDNs could release the NETs spontaneously [17].

NETs are a network of extracellular fibres, compounds of chromatin, neutrophil DNA, and histones, which are covered with antimicrobial enzymes with granular components such as myeloperoxidase (MPO), neutrophil elastase, cathepsin G, and other microbicidal peptides. Autophagy and the production of ROS by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase or mitochondria of neutrophils are essential in the formation of NETs. NETs formation is a mechanism that protects against pathogens, but many of NETs components could be recognized by the immune system as autoantigens, triggering immune response [18]. Additionally, in patients with SLE, NETs activate plasmatic dendritic cells to produce high levels of IFN-α [19].

Thus, there are two principal mechanisms by which neutrophils could influence on lymphocyte count.

Neutrophil dependent overproduction of IFN-α/β could induce reversible lymphopenia through direct action on B- and T-cells, redirecting the lymphocytes in the secondary lymphatic organs, liver and lungs [20].

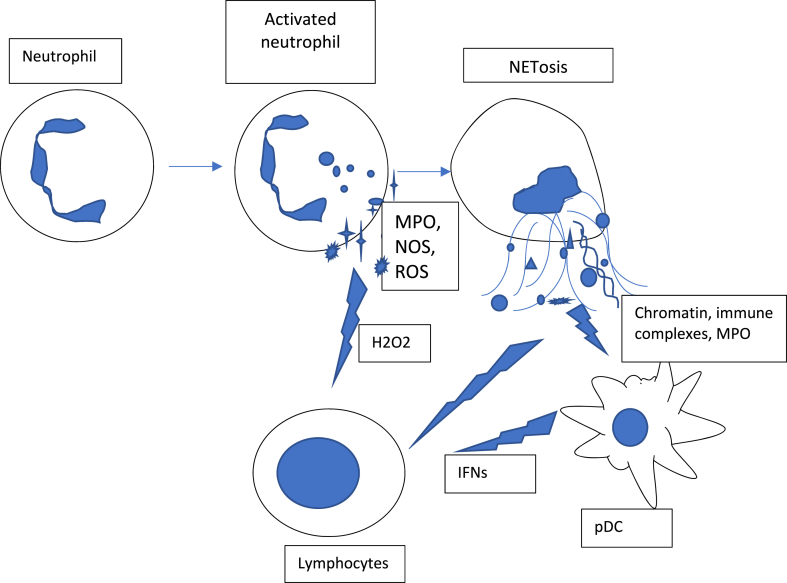

During neutrophil activation and NETs liberation, the expression of ROS and MPO increases, leading to a redox imbalance followed by cellular damage and persistent chronic inflammation [21], which is associated with elevated levels of superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and hypochlorous acid. In this manner, the activated neutrophils suppress T- and B-cell effector functions through a hydrogen-peroxide-dependent mechanism [22] (Fig. 1.).

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms of lymphocyte suppression by neutrophils. Activated neutrophils release reactive oxygen species (ROS), myeloperoxidase (MPO) that could induce lymphopenia by H202-dependent mechanism. NETs content stimulates production of type I Interferons (IFNs) by plasmatic dendritic cells (pDC).

The presence of LDNs has been associated with different autoimmune diseases such as SLE, rheumatoid arthritis [8], antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis [23], myositis [24], primary antiphospholipid syndrome [25], psoriasis [26], dermatomyositis/polymyositis [27].

3. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, C-reactive protein and type I interferons

The NLR, calculated as a simple ratio between the neutrophil and lymphocyte counts measured in peripheral blood, is a biomarker that reflects the balance between two aspects of the immune system: acute and chronic inflammation (as indicated by the neutrophil count) and adaptive immunity (lymphocyte count) [28].

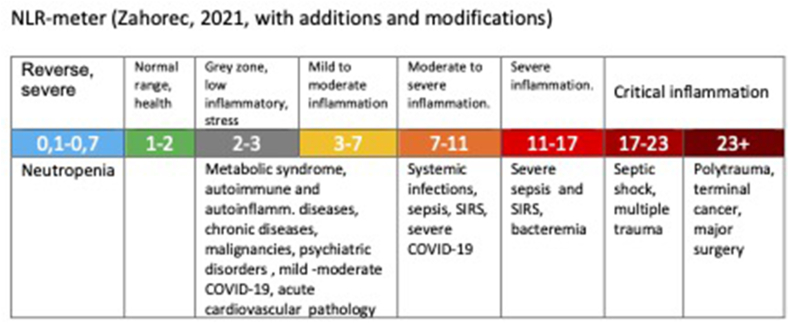

R. Zahorec (2021) has recently published the analysis of data from almost 200 studies conducted over the last 20 years, on the usefulness of NLR for screening, risk stratification and prognosis in different pathologies, especially in different types of cancer, bacterial and viral infections, systemic inflammation (SIRS), sepsis, trauma, psychiatric pathologies, myocardial infarction, ulcerative colitis and inflammatory bowel disease, stroke, different pathologies of critical care medicine. Based on this analysis, he proposes the normal range of NLR is between 1 and 2 (normal NLR median in healthy adults in different races worldwide 1,65, range 1.2–2.15), the values higher than 3 and below 0,7 in adults are pathological. The NLR between 2 and 3 is considered as a grey zone corresponding to latent, subclinical or low-grade inflammation [29] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio indicate the intensity of immune-inflammatory reactions. Cut-off values are prime numbers based on analysis of numerous epidemiological studies in different pathalogies [29].

A large observational Taiwanese study by Liu et al. (2019) with 34,013 subjects enrolled with a median age of 50.46 ± 11.09 shows that NLR is a good predictor for metabolic syndrome (MS). The median value of NLR in the no–MS group of 23,539 subjects was 1.84 ± 0.69; in the MS group of 10,475 subjects was 1.96 ± 0.77. One of the important limitations of this study was that the comorbidity of the subjects was not taken into account, which also could influence the range of NLR [30].

Azab et al. (2014) study with 9427 subjects from the database of The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) of the USA shows that non–Hispanic afrodecendents (mean NLR 1.76) and Hispanic (mean NLR 2,08) have significantly lower mean NLR value than compared with non-Hispanic Caucasians (mean NLR 2,15). Additionally, were observed that NLR was significantly higher in persons with elevated BMI (one-third of the studied population was overweight BMI 30kg/m2), in persons who reported diabetes, cardiovascular pathology, being smokers, older age and is negatively related with poverty index [31].

Kalra et al. studied the correlation between NLR and proinflammatory neutrophils, specifically LDNs, in patients with end-stage liver disease with cirrhosis and found that patients with an NLR greater than 4 had elevated levels of circulating LDNs and monocytes but reduced levels of natural killer cells. The authors concluded that NLR is an important marker of immune dysregulation and systemic inflammation and a predictor of mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Since the liver is physiologically related to other markers of systemic inflammation, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), vitamin D, and free cortisol, the investigators also note that NLR becomes a more appropriate marker of systemic inflammation in the case of liver involvement in a pathological process [32].

Han et al. demonstrated that patients with lupus exhibit higher NLRs than healthy controls and show an association between lupus activity by SLE-disease activity index (SLEDAI) and higher NLR values. The cut–off for high NLR was defined as 2.73 in this study. High NLR was associated with the immune complex-driven disease with the presence of anti-dsDNA antibodies, circulating immune complexes, and type I IFNs activity. The increased neutrophil count was associated with the presence of markers of their activity and a decrease in the number of lymphocytes - with activity and type I IFNs, and a high number of NLR [33].

In this context, it is important to remember that CRP levels in patients with lupus often do not correspond to the levels of disease activity and IL-6 expression [34]. Enoccson et al. (2004) demonstrated that IFN- α inhibits IL-6/IL-1 beta induced transcription genes for the production of CRP by hepatocytes [35]. Unlike in bacterial infections and autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, CRP levels are often not elevated in SLE [36], and this phenomenon limits the use of this inflammation marker for patients with lupus. Several studies have shown that decreased CRP production by hepatocytes can be influenced by both the rs1205 genetic polymorphism that is frequently detected in patients with lupus [37] and inhibition of CRP production by IFN-α [38]. The combination of two these factors rules to the inability of CRP to reflect the inflammatory activity in such SLE patients [39].

Considering that SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, dermatomyositis/polymyositis share activation of a common type I IFNs pathway [40], and that dysregulation of type I IFNs system is a key driver of inflammation in Sjögren syndrome [41], is reasonable to pay attention to biomarkers of inflammation in these pathologies, too, asking if CRP reflects really level of inflammation or is mitigated by IFNs?

4. Conclusion

The NLR is a parameter that is easily calculated from any differential white blood cell count as either the ratio of absolute cell count or as the ratio of relative cell count, dividing neutrophils by lymphocytes [42].

The NLR could reflect not only quantitative but also qualitative changes in neutrophils and lymphocytes in patients with autoimmune diseases.

This parameter could be helpful to evaluate the degree of inflammation or even subclinical inflammation in patients with systemic inflammatory diseases. Also, it could be interesting to test NLR as a prognostic biomarker for relapse in autoimmune diseases.

The latest findings indicate the need for further investigation of the applicability of NLR as an inflammatory biomarker in autoimmune diseases, particularly in specific phenotypes of lupus and other autoimmune pathologies in which the common acute phase reactants are not reflecting actual levels of inflammation.

Clinical studies in patients with autoimmune diseases are required to address each of these questions.

Credit author statement

Maria Kourilovitch: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Claudio Galarza–Maldonado: Writing – original draft preparation

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Authors declare no competing interests.

Both authors contributed equally to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Silva M.T., Correia-Neves M. Neutrophils and macrophages: the main partners of phagocyte cell systems. Front. Immunol. 2012;3 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navegantes K.C., Gomes R.D.S., Aparecida P., et al. Immune modulation of some autoimmune diseases: the critical role of macrophages and neutrophils in the innate and adaptive immunity. J. Transl. Med. 2017;15:e36. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1141-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng L.G., Ostuni R., Hidalgo A. Heterogeneity of neutrophils. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019;19:255–265. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Decker P. Neutrophils and interferon-α-producing cells: who produces interferon in lupus? Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011;13(4):118. doi: 10.1186/ar3345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sturge C.R., Benson A., Raetz M., et al. TLR-independent neutrophil-derived IFN- is important for host resistance to intracellular pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013;110(26) doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307868110. 10711–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganguly D. Do type I interferons link systemic autoimmunities and metabolic syndrome in a pathogenetic continuum? Trends Immunol. 2018;39(1):28–43. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Decker P. Neutrophils and interferon-ɑ-producing cells: who produces interferon in lupus? Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011;13:e118. doi: 10.1186/ar3345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morand E.F., Furie R., Tanaka Y., et al. Trial of anifrolumab in active systemic lupus erythematosus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:211–221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1912196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lelis F.J.N., Jaufmann J., Singh A., et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells modulate B-cell responses. Immunol. Lett. 2017;188:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zipursky A., Bow E., Seshadri R.S., Brown E.J. Leukocyte density and volume in normal subjects and in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1976;48(3):361–371. doi: 10.1182/blood.V48.3.361.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hacbarth E., Kajdacsy-Balla A. Low density neutrophils in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and acute rheumatic fever. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(11):1334–1342. doi: 10.1002/art.1780291105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denny M.F., Yalavarthi S., Zhao W., et al. A distinct subset of proinflammatory neutrophils isolated from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus induces vascular damage and synthesizes type I IFNs. J. Immunol. 2010;184(6):3284–3297. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanco-Camarillo C., Alemán O.R., Rosales C. Low-density neutrophils in healthy individuals display a mature primed phenotype. Front. Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.672520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassani M., Hellebrekers P., Chen N., et al. On the origin of low-density neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020;107:809–818. doi: 10.1002/JLB.5HR0120-459R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardisty G.R., Llanwarne F., Minns D., et al. High purity isolation of low density neutrophils casts doubt on their exceptionality in health and disease. Front. Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.625922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carmona-Rivera C., Kaplan M.J. Low-density granulocytes: a distinct class of neutrophils in systemic autoimmunity [review] Semin. Immunopathol. 2013;35:455–463. doi: 10.1007/s00281-013-0375-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papayannopoulos V. Neutrophil extracellular traps in immunity and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018;18:134–147. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bravo-Barrera J., Kourilovitch M., Galarza-Maldonado C. Neutrophil extracellular traps, antiphospholipid antibodies and treatment. Antibodies. 2017;6 doi: 10.3390/antib6010004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Romo G.S., Caielli S., Vega B., Connolly J., Allantaz F., et al. Netting neutrophils are major inducers of type I IFN production in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:73. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001201. https://doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3001201 73ra20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamphuis E., Junt T., Waibler Z., Forster R., Kalinke U. Type I interferons directly regulate lymphocyte recirculation and cause transient blood lymphopenia. Blood. 2006;108(10):3253–3261. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-027599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crucian B.E., Chouker A., Simpson R.J., et al. Immune system dysregulation during spaceflight: potential countermeasures for deep space exploration missions. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:e1437. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kramer P.A., Prichard L., Chacko B., et al. Inhibition of the lymphocyte metabolic switch by the oxidative burst of human neutrophils. Clin Sci. 2015;129(6):489–504. doi: 10.1042/CS20140852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ui Mhaonaigh A., Coughlan A.M., Dwivedi A., et al. Low density granulocytes in ANCA vasculitis are heterogenous and hypo-responsive to anti-myeloperoxidase antibodies. Front. Immunol. 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seto N., Torres-Ruiz J.J., Carmona-Rivera C., et al. Neutrophil dysregulation is pathogenic in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. JCI Insight. 2020;5(3) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.134189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yalavarthi S., Gould T.J., Rao A.N., et al. Release of neutrophil extracellular traps by neutrophils stimulated with antiphospholipid antibodies: a newly identified mechanism of thrombosis in the antiphospholipid syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(11):2990–3003. doi: 10.1002/art.39247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang W.M., Jin H.Z. Role of neutrophils in psoriasis. J Immunol Res. 2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/3709749. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang S., Shen H., Shu X., Peng Q., Wang G. Abnormally increased low-density granulocytes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells are associated with interstitial lung disease in dermatomyositis. Mod. Rheumatol. 2017;27:122–129. doi: 10.1080/14397595.2016.1179861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song M., Graubard B.I., Rabkin C.S., et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and mortality in the United States general population. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:e464. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79431-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zahorec R. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio past, present and future perspectives. Bratisl Med J. 2021;122(7):474–488. doi: 10.4149/BLL_2021_078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu C.C., Ko H.J., Liu W.S., Hung C.L., Hu K.C., Yu L.Y., Shih S.C. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a predictive marker of metabolic syndrome. Medicine. 2019;98(43) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azab B., Camacho-Rivera M., Taioli E. Average values and racial differences of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio among a nationally representative sample of United States subjects. PLoS One. 2014;9(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalra A., Wedd J.P., Bambha K.M., et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio correlates with proinflammatory neutrophils and predicts death in low model for end-stage liver disease patients with cirrhosis. Liver Transplant. 2017;23:2. doi: 10.1002/lt.24702. 155–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han B.K., Wysham K.D., Cain K.C., et al. Neutrophil and lymphocyte counts are associated with different immunopathological mechanisms in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus Science & Medicine. 2020;7 doi: 10.1136/lupus-2020-000382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gabay C., Roux-Lombard P., de Moerloose P., et al. Absence of correlation between interleukin 6 and C-reactive protein blood levels in systemic lupus erythematosus compared with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 1993;20(5):815–821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Enocsson H., Sjöwall C., Skogh T., Eloranta M.L., Rönnblom L., Wetterö J. Interferon-alpha mediates suppression of C-reactive protein: explanation for muted C-reactive protein response in lupus flares? Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(12):3755–3760. doi: 10.1002/art.25042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakayama S., Urano Sonoda T., et al. Monitoring both serum amyloid protein A and C-reactive protein as inflammatory markers in infectious diseases. Clin. Chem. 1993;39(2):293–297. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/39.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russell A.I., Cunninghame Graham D.C., Shepherd C., et al. Polymorphism at the C-reactive protein locus influences gene expression and predisposes to systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004;13(1) doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh021. 137–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Enocsson H., Gullstrand B., Eloranta M.-L., et al. C-reactive protein levels in systemic lupus erythematosus are modulated by the interferon gene signature and CRP gene polymorphism rs1205. Front. Immunol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.622326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Enocsson H., Sjöwall C., Kastbom A., Skogh T., Eloranta M.-L., Rönnblom L. J. Wetterö of serum, 2014 Association of serum C-reactive protein levels with lupus disease activity in the absence of measurable interferon-α and a C-reactive protein gene variant. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(6):1568–1573. doi: 10.1002/art.38408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Higgs B.W., Liu Z., White B., Zhu W., White W.I., Morehouse C., Brohawn P., Kiener P.A., Richman L., Fiorentino D., Greenberg S.A., Jallal B., Yao Y. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, myositis, rheumatoid arthritis and scleroderma share activation of a common type I interferon pathway. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011;70(11):2029–2036. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.150326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brito-Zerón P., Baldini C., Bootsma H., Bowman S.J., Jonsson R., Mariette X., Sivils K., Theander E., Tzioufas A., Ramos-Casals M. Sjögren syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2016;2 doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farkas J.D. The complete blood count to diagnose septic shock. J. Thorac. Dis. 2019;1:S16–S21. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.12.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]