Abstract

In simultaneous prompting procedures, an immediate (i.e., 0-s) prompt is presented during all training trials, and transfer to the target discriminative condition is assessed during daily probes. Previous research suggests that simultaneous prompting procedures are efficacious and may produce acquisition in fewer errors to mastery when compared to prompt delay procedures. To date, only a single study on simultaneous prompting has included intraverbal targets. The current study evaluated the efficacy of a simultaneous prompting procedure on the acquisition of intraverbal synonyms for six children at risk for reading failure. Simultaneous prompting alone produced responding at mastery levels in seven of the 12 evaluations. Antecedent-based procedural modifications were effective in four of the five remaining evaluations. Errors were generally low for all but one participant. The current findings support the use of simultaneous prompting procedures when targeting intraverbals for young children exhibiting reading deficits.

Keywords: Intraverbals, Prompting, Simultaneous prompting, Synonyms

The intraverbal is a verbal operant characterized by the emission of a verbal response that lacks point-to-point correspondence with the antecedent verbal stimulus (Axe, 2008; Palmer, 2016). Common intraverbal targets include fill-ins (e.g., “red, white, and…”), associations (e.g., “shoes and…”), and wh- questions (e.g., “what do you ride?”; Lukevich, 2008; Sundberg & Partington, 1998). One type of intraverbal, intraverbal synonyms, represent an understudied topic in verbal behavior research. Intraverbal synonyms may be distinguished from intraverbal associations as the latter include antecedent verbal stimuli and responses that are not equivalent. For example, a common intraverbal association includes the antecedent verbal stimulus “shoes and…” evoking the response “socks.” This relation would be categorized as an intraverbal association, but not a synonym. In contrast, the antecedent verbal stimulus “tell me another word for scared” and response “afraid,” may be considered an intraverbal synonym as both the antecedent and response may be used interchangeably (i.e., equivalent). To the authors’ knowledge, Kisamore et al. (2013) is the only study in the verbal behavior literature that included intraverbal synonyms; although, research on second-language instruction targeting native-to-foreign and foreign-to-native intraverbals may also be considered intraverbal synonym training (e.g., Daly & Dounavi, 2020; Dounavi, 2011). Nevertheless, additional studies on intraverbal synonyms are needed and previous research on methods to teach intraverbal behavior remain relevant.

Several studies have examined the use of various types of prompts on the acquisition of intraverbals (see review by Aguirre et al., 2016). Three prompt types have been described in the intraverbal training literature and include echoic (Ingvarsson & Hollobaugh, 2011; Ingvarsson & Le, 2011; Kisamore et al., 2013), tact (Goldsmith et al., 2007; Ingvarsson & Hollobaugh, 2011; Partington & Bailey, 1993), and textual (Vedora et al., 2009) prompts. The focus of these studies has generally been on the type of prompt, not the method to transfer stimulus control (i.e., prompt-fading procedure). Indeed, several of these articles used very similar constant prompt-delay procedures (Coon & Miguel, 2012; Emmick et al., 2010; Goldsmith et al., 2007; Humphreys et al., 2013; Ingvarsson & Le, 2011). As a result, additional research is needed on prompt fading or related methods to transfer stimulus control when targeting the intraverbal relation.

Simultaneous prompting is frequently arranged in a discrete-trial format and involves the immediate presentation of the prompt for the duration of training. In this way, simultaneous prompting is similar to prompt-delay procedures, except the prompt is never faded (Brown & Cariveau, 2022; Schuster et al., 1992). Instead, all training trials are conducted at a 0-s prompt delay and transfer to the target discriminative stimulus is assessed during daily or intermittent probes (Reichow & Wolery, 2009). In one example, MacFarland-Smith et al. (1993) taught three preschool-aged students with developmental disabilities to tact fruits and vegetables using a simultaneous prompting procedure. During training sessions, each target was presented six times using a 0-s echoic prompt. Acquisition of the target tacts was assessed during daily probe sessions that occurred before training each day. The authors observed rapid acquisition and high levels of maintenance across all target sets. Similar findings of efficacy are common in research on simultaneous prompting procedures with a recent review suggesting that they be considered an evidence-based practice (Tekin-Iftar et al., 2019).

Recently, Brown and Cariveau (2022) noted the considerable overlap between prompt-delay and simultaneous prompting procedures. In their systematic review of 11 studies comparing prompt delay and simultaneous prompting procedures, the authors found that both procedures were consistently effective and frequently did not differ across measures of efficiency (e.g., time or sessions to mastery). Brown and Cariveau (2022) noted, however, that simultaneous prompting resulted in fewer errors to mastery in 70.8% of comparisons. This finding suggests that simultaneous prompting may be an optimal prompting procedure as it has been commonly shown to be efficacious and may result in fewer errors to mastery than other instructional arrangements.

To the authors’ knowledge, only one study on simultaneous prompting has included intraverbal targets. Notably, this article was published in the educational literature and did not explicitly refer to their targets as intraverbals. Specifically, Akmanoglu et al. (2015) compared prompt delay and simultaneous prompting procedures on the acquisition of wh- intraverbals (e.g., “what is your phone number?”) for three children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The authors reported mastery in an equal number of sessions and trials for both procedures for two participants, although the simultaneous prompting procedure consistently required fewer errors and minutes to mastery for each participant. For the final participant, simultaneous prompting required fewer sessions, trials, errors, and minutes to mastery. Although promising, additional research is needed to demonstrate the efficacy of simultaneous prompting on the acquisition of academically relevant intraverbals for children. Moreover, the vast majority of research on simultaneous prompting has included children with intellectual or developmental disabilities (Tekin-Iftar et al., 2019; Waugh et al., 2011). As such, additional research is needed to determine the efficacy of simultaneous prompting with other populations, particularly those who may be underrepresented in the behavior-analytic literature, such as children from economically disadvantaged homes (Fontenot et al., 2019). The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the effects of a simultaneous prompting procedure on the acquisition and maintenance of intraverbal synonyms for kindergarten and first-grade students at risk for reading failure.

Method

Participant and Settings

Participants were five- and six-year-old children at risk for reading failure recruited from the surrounding community or a local elementary school. A caregiver provided permission and the participants provided daily assent. All participants except Julieta were enrolled in a high-poverty school, classified as greater than 75% of students being eligible for free or reduced-price lunch by the National Center for Education Statistics (McFarland et al., 2019). Reading benchmark assessments were completed with all participants within two months of participation using Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS; University of Oregon, 2020) curriculum-based measures. These data were unavailable for Dolores. Participant information is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographic information

| Participant | Age (years) | Gender | Race/ethnicity | Diagnosis | DIBELS classificationa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imani | 6 | Female | Black or African American | None | At risk |

| Keysha | 6 | Female | Black or African American | None | At risk |

| Keion | 6 | Male | Black or African American | None | At risk |

| Luisa | 5 | Female | Black or African American | None | At risk |

| Dolores | 5 | Female | Black or African American | None | Not available |

| Julieta | 6 | Female | White or Caucasian | ASD | At risk |

a80% of students below the 20th percentile are considered “at risk” (University of Oregon, 2020); ASD = autism spectrum disorder

All sessions took place in a 1:1 setting that included an individual table, chairs, and research-related materials (e.g., data sheets, timers, pens). Sessions were conducted during morning appointments either at a university laboratory (Julieta) or a classroom in their school. Preferred tangible items were made available during 2-min breaks following experimental sessions.

Dependent Variables and Response Measurement

The primary dependent variable was unprompted correct responses defined as the participant emiting the target response within 5 s of the presentation of the antecedent verbal stimulus. Throughout training, participants may have also emitted prompted correct responses, unprompted incorrect responses, and prompted incorrect responses. Prompted correct responses were defined as the participant emitting the target response within 5 s of the presentation of the echoic prompt. Unprompted and prompted incorrect responses were defined as the participant emitting a non-target response or no response within 5 s of the antecedent verbal stimulus or echoic prompt, respectively. The experimenter also recorded the number of errors that occurred prior to meeting the mastery criterion as a metric of instructional efficiency. This was determined by summing the total number of incorrect unprompted or prompted responses during training and daily probes. The mastery criterion was set as one daily probe with 100% unprompted correct responses for the target set.

Experimental Design

A concurrent multiple-baseline design across target sets was used to evaluate the effects of simultaneous prompting on unprompted correct responses during daily probes. This design was selected as baseline probes in the second (i.e., staggered) panel allowed for the detection of threats to internal validity such as historical variables and the effects of repeated testing. Target sets were also counterbalanced across participants when possible (Table 2).

Table 2.

Target sets for each participant

| Participant | Set 1 | Set 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Luisa | Yell (Shout) | Neat (Tidy) |

| Fast (Quick) | Hide (Cover) | |

| Mad (Angry) | Tired (Sleepy) | |

| Keysha | Hide (Cover) | Big (Large) |

| Trash (Garbage) | Under (Below) | |

| Yell (Shout) | Scared (Afraid) | |

| Dolores | Trash (Garbage) | Big (Large) |

| Yell (Shout) | Funny (Silly) | |

| Fast (Quick) | Mad (Angry) | |

| Julieta | Yell (Shout) | Neat (Tidy) |

| Mad (Angry) | Tired (Sleepy) | |

| Fast (Quick) | Hide (Cover) | |

| Keion | Present (Gift) | Fast (Quick) |

| Girl (Woman) | Boy (Man) | |

| Bag (Backpack) | Neat (Tidy) | |

| Imani | Scared (Afraid) | Trash (Garbage) |

| Big (Large) | Yell (Shout) | |

| Under (Below) | Hide (Cover) |

The word outside of the parenthesis was always presented as part of the antecedent verbal stimulus “Tell me another word for [word].” The target response is shown in parentheses

General Procedure

Appointments lasting approximately 50 min were conducted two-to-four times each week. Each appointment began with a daily probe. All daily probe and training sessions included a total of six trials. After an initial baseline phase, each daily probe was followed by two training sessions. All sessions were conducted in the morning; however, the timing of the training sessions varied across days and were conducted along with various other instructional or research-related protocols.

Daily Probe

The experimenter began by introducing the task using the following script: “Let’s work on some of our words. I want to see if you know these ones yet. I’m not going to tell you if you get them right, so just try your best.” The experimenter then presented the antecedent verbal stimulus (e.g., “tell me another word for scared”). No differential consequences were presented following unprompted correct or incorrect responses. All targets from each set were presented once for a total of six trials.

Simultaneous Prompting

Two training sessions were conducted daily. Each session included three targets presented twice for a total of six trials. Before the first training session, the experimenter said “Let’s work on some of our words. You say the word after I say it.” The experimenter then presented the antecedent verbal stimulus for the first target (e.g., “tell me another word for scared”) and immediately prompted the correct response (e.g., “say afraid”). If the participant emitted a prompted correct response, the experimenter delivered social praise and attention (e.g., “You got it!” and high fives) followed by the next trial. Prompted incorrect responses resulted in the re-presentation of the trial until a prompted correct response was emitted. After all six trials were presented, the participant received a 2-min break and access to a preferred tangible item (e.g., Legos, coloring books, slime).

Procedural Modifications

The experimenter reviewed the participants’ data using visual analysis and included procedural modifications as needed.

Differential Observing Response

Training trials began by requiring that the participant echo a portion of the antecedent verbal stimulus (e.g., “Say scared”). After the participant emitted the echoic (e.g., “scared”), the experimenter presented the trial as described above.

Re-Present Until Independent

This procedure required that the participant emit an unprompted correct response on each trial. Specifically, the experimenter presented the trial using the simultaneous prompting procedure described above. After a prompted correct response, the experimenter re-presented the antecedent verbal stimulus and allowed the participant 5 s to respond. Unprompted correct responses resulted in social praise and the presentation of the next trial. Incorrect responses resulted in the re-presentation of the trial beginning with the simultaneous (i.e., 0-s) prompt and an independent opportunity. This procedure was repeated until an unprompted correct response was emitted.

Prompt Delay

One participant exhibited frequent errors during daily probes characterized by emitting each target in the set in a seemingly random pattern (i.e., scrolling). For this participant, a 5-s prompt delay procedure was introduced. Specifically, all training trials began with the experimenter presenting the antecedent verbal stimulus and allowing the participant 5 s to respond. Unprompted correct responses resulted in social praise and the presentation of the next trial. Incorrect responses resulted in a prompted trial and the trial being re-presented using a 5-s prompt delay. This was repeated until the participant emitted an unprompted correct response.

Maintenance

Maintenance probes were conducted 8 to 20 days after the mastery criterion was met. Although we attempted to conduct 14-day maintenance probes with all participants, absences and school breaks resulted in considerable variation in the timing of these probes. Procedures were identical to the daily probes.

Interobserver Agreement and Procedural Integrity

An independent observer was present during at least 20% of sessions for all participants to collect reliability and procedural integrity data. Trial-by-trial interobserver agreement (IOA) was calculated by dividing the total number of trials in a session with an agreement by the total number of trials, multiplied by 100. Procedural integrity data were also recorded by an independent observer on a trial-by-trial basis. Procedural integrity was scored if all components of the trial were conducted as described in the research protocol. All IOA and procedural integrity data are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Interobserver agreement and procedural integrity

| Interobserver agreement | Procedural integrity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant | Sessions (%) | Mean (%) | Range (%) | Sessions (%) | Mean (%) | Range (%) |

| Luisa | 20.0% | 100% | 100% | 20.0% | 100% | 100% |

| Keysha | 91.3% | 99.2% | 83.3–100% | 91.3% | 96.8% | 50.0–100%* |

| Dolores | 27.7% | 98.7% | 83.3–100% | 27.7% | 100% | 100% |

| Julieta | 75.7% | 100% | 100% | 81.1% | 98.8% | 66.7–100%* |

| Keion | 88.0% | 100% | 100% | 88.0% | 99.5% | 66.7–100%* |

| Imani | 75.0% | 99.6% | 83.3–100% | 75.0% | 98.9% | 50.0–100%** |

Percent of sessions with IOA, mean IOA, and range of IOA are shown in the left-most columns. Percent of sessions with procedural integrity, mean integrity, and range of integrity are shown in the right-most columns. *One session fell below 80% fidelity. **Two sessions fell below 80% fidelity

Results

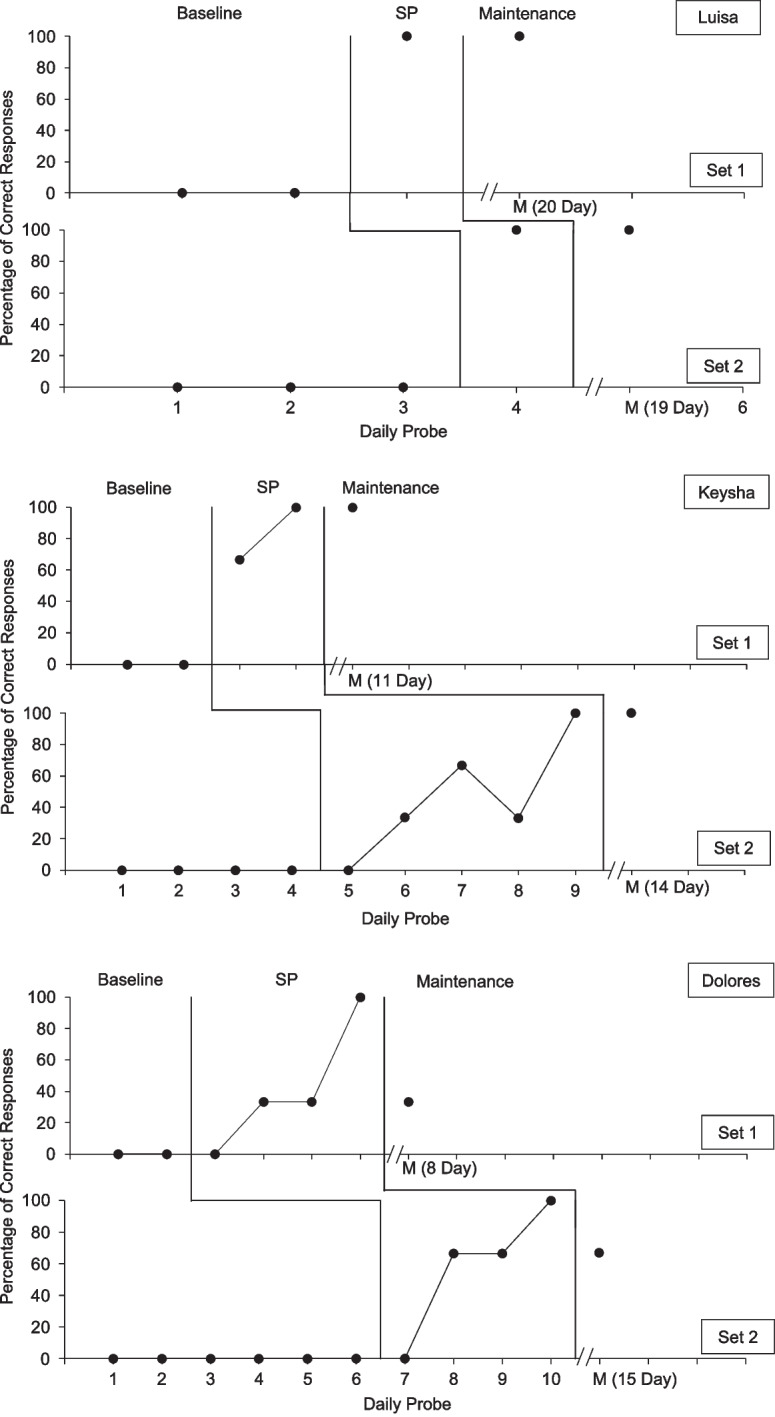

Luisa’s performance is shown in the top two panels of Fig. 1. No correct responses were emitted during the baseline phase for either target set. Mastery-level responding was observed in the first simultaneous prompting probe for both sets and her performance maintained at 100% unprompted correct responses during 20- and 19-day maintenance probes for Sets 1 and 2, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Simultaneous prompting evaluation for Luisa, Keysha, and Dolores. Note. SP = simultaneous prompting

The results for Keysha are displayed in the third and fourth panels of Fig. 1. No correct responses were emitted during baseline for either target set. Responding met the mastery criterion in two probes for Set 1 and five probes for Set 2. Maintenance probes were conducted after 11 days and 14 days for Sets 1 and 2, respectively. Correct responding remained at 100% across maintenance probes for both target sets.

The findings for Dolores are displayed in the bottom two panels of Fig. 1. No correct responses were observed during either baseline phase. Dolores’ performance met the mastery criterion in the simultaneous prompting phase in four probes for both Sets 1 and 2. Maintenance probes were conducted after eight days for Set 1 and 15 days for Set 2. Dolores emitted 33.3% and 66.7% correct responses across Sets 1 and 2, respectively.

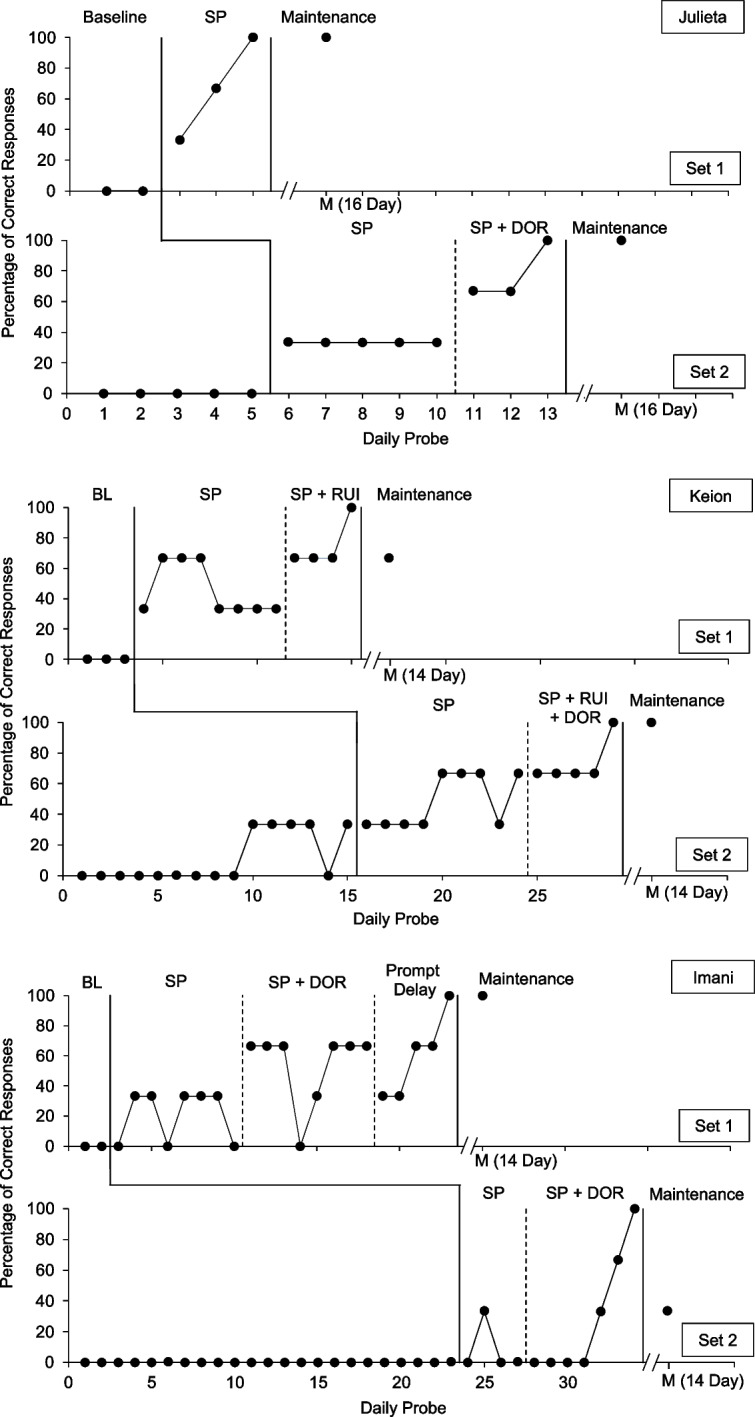

The findings for Julieta are shown in the top two panels of Fig. 2. Responding remained at zero levels during baseline for both target sets. During simultaneous prompting, Julieta’s performance met the mastery criterion in three probes for Set 1. During Set 2 training, her performance immediately increased, but remained at low levels for five probes. A DOR was introduced, and the mastery criterion was met in three probes. Sixteen-day maintenance probes were conducted for both sets and responding maintained at 100% correct responses.

Fig. 2.

Simultaneous prompting evaluation for Julieta, Keion, and Imani. Note. BL = baseline; SP = simultaneous prompting; RUI = re-present until independent; DOR = differential observing response; M = maintenance

Keion’s performance is shown in the third and fourth panels of Fig. 2. No correct responses were observed during the baseline phase for Set 1. Correct responding increased during simultaneous prompting but remained below the mastery criterion. A re-present until independent procedure was introduced and responding met the mastery criterion in four probes. During baseline for Set 2, correct responding increased for a single target. After the introduction of simultaneous prompting, responding increased; however, a pervasive response bias was observed for a single target. As a result, a DOR and re-present until independent procedure was introduced and responding met the mastery criterion in five probes. Fourteen-day maintenance probes were conducted for both sets and correct responding was observed at 66.7% and 100% for Sets 1 and 2, respectively.

The findings for Imani are shown in the bottom two panels of Fig. 2. No correct responses were emitted during the baseline phases for either target set. Simultaneous prompting was introduced for Set 1 and correct responding was observed at variable, but low, levels. A DOR was introduced and an immediate increase in correct responding was observed, although performance never reached the mastery criterion. A prompt-delay procedure was then introduced and responding at mastery levels was observed after five probes. Set 2 was then exposed to simultaneous prompting and a single correct response was emitted across four probes. A DOR was then introduced and responding met the mastery criterion after seven probes. Maintenance probes were conducted after 14 days for both sets. Imani emitted 100% correct responses for Set 1 and 33.3% correct responses for Set 2.

The total number of daily probes and errors are shown in Table 4. Participants generally emitted few errors during simultaneous prompting with Luisa exhibiting errorless performance for both target sets. Keysha also exhibited nearly errorless acquisition of Set 1 targets with only two errors emitted during training. Only Imani emitted greater than 20 errors during training, which was observed in both sets.

Table 4.

Number of daily probes and errors to mastery

| Participant | Set 1 | Set 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probes to mastery | Total errors | Probes to mastery | Total errors | |

| Luisa | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Keysha | 2 | 2 | 6 | 11 |

| Dolores | 4 | 8 | 4 | 5 |

| Julieta | 3 | 6 | 8* | 12* |

| Keion | 12* | 16* | 14* | 18* |

| Imani | 21* | 62* | 10* | 27* |

*Target sets that required a procedural modification to produce responding at mastery levels

Discussion

The current findings suggest that simultaneous prompting alone was effective in producing responding at mastery levels for seven out of 12 (58.3%) evaluations. Modifications to the simultaneous prompting procedure were required to produce responding at mastery levels for four target sets. Finally, a prompt-delay procedure was introduced following persistent error patterns for one target set (Imani). The current findings replicate those of previous research on the efficacy of simultaneous prompting (Tekin-Iftar et al., 2019). Further, we extended previous research by targeting intraverbal synonyms and incorporating antecedent-based procedural modifications, which have not been included in past research on simultaneous prompting.

The current study sought to extend the extant literature on intraverbal training and simultaneous prompting procedures. Although several prompt types (e.g., echoic, tact, or textual) have received attention in the literature on intraverbal training, the vast majority of research has only included prompt-delay procedures (Goldsmith et al., 2007; Ingvarsson & Hollobaugh, 2011; Vedora et al., 2009). The current study extended prior research by demonstrating the efficacy of simultaneous prompting using echoic prompts on the acquisition of intraverbal synonyms. For Imani, a prompt-delay procedure was introduced to remediate pervasive error patterns for one target set; however, it is unclear whether antecedent-based modifications, such as the re-present until independent procedure, would have also been effective.

Previous research comparing prompting strategies during intraverbal training suggest that certain prompt types may be more effective or efficient for an individual learner, although these findings are generally mixed. Comparison studies have found tact prompts to be more efficient than echoic prompts (Ingvarsson & Hollobaugh, 2011), echoic prompts to be more efficient than tact prompts (Kodak et al., 2012), or mixed findings of efficiency (Ingvarsson & Le, 2011). Additionally, similar ambiguous findings have also been reported in comparisons of textual and echoic prompts (Vedora et al., 2009; Vedora & Conant, 2015). The inconsistency of these findings may present challenges to behavior analysts attempting to identify optimal instructional arrangements. Nevertheless, because these comparisons have only included prompt-delay procedures, it is unclear whether similar findings would be observed using simultaneous prompting procedures.

The current study included echoic prompts for two reasons. First, textual prompts were deemed to be inappropriate because the participants exhibited reading deficits. Vedora et al. (2009) either directly trained the textual relation or used previously mastered textual relations as prompts. Due to the deficient textual performances of the participants in the current study, training the textual relations may have required substantial effort or time and were misaligned with their current academic goals. Tact prompts were also deemed to be inappropriate as the intraverbal targets were synonyms, so a nonverbal antecedent stimulus (e.g., picture) may not differentially evoke the target response as the response and antecedent verbal stimulus would ideally be interchangeable (i.e., equivalent). For example, the antecedent verbal stimulus “tell me another word for scared” should evoke the response “afraid.” However, presenting a tact prompt, such as a picture of an afraid face, may not reliably evoke the response “afraid” because it may also evoke the response “scared.” It would be possible to teach a learner to differentially respond to distinct pictures as “scared” or “afraid” to be used as prompts; however, doing so may be inappropriate as the terminal performance should involve the learner responding to both pictures as equivalent (i.e., tacting either picture as “scared” or “afraid”). Nevertheless, future research might use other prompt types or even conduct a formal assessment (e.g., Kodak & Halbur, 2021) to identify the most efficient or effective prompt type for an individual learner.

The current study extended previous research in several ways. First, we included a participant population that is infrequently included in research on simultaneous prompting: five Black or African American children from a high-poverty school who had no reported developmental or intellectual disabilities. Most of the research on simultaneous prompting has included individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities (Tekin-Iftar et al., 2019; Waugh et al., 2011). Indeed, Tekin-Iftar et al. (2019) conducted a descriptive review of studies on simultaneous prompting and identified only one article that included two children of typical development (Parker & Schuster, 2002). Reichow and Wolery (2009) also included two five-year-old children who identified as Black or African American and were of typical development or at risk of school failure, although this study was not included in the descriptive analysis by Tekin-Iftar et al. (2019). Additional research should include participants without intellectual or developmental disabilities, particularly children experiencing economic disadvantages as they represent an underrepresented population in behavior-analytic research (Fontenot et al., 2019). We also extended previous research by targeting intraverbal synonyms. These intraverbal relations are an understudied, but meaningful topic in verbal behavior research. Finally, we included antecedent-based interventions that have not previously been described in research on simultaneous prompting. Future research might consider how similar modifications may be used to bolster instructional gains while maintaining the potential development of errorless, or nearly errorless, stimulus control. Differential observing responses and re-present until independent procedures are just some of the ways in which simultaneous prompting procedures may be modified. Additionally, the current study only included these modifications after simultaneous prompting alone did not result in mastery levels of responding. Future research might consider whether including these modifications from the outset of training would result in more efficient, and hopefully errorless, acquisition.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, the use of extinction following all responses during daily probes may not be common practice in simultaneous prompting research. In fact, Reichow and Wolery (2009) explicitly identified differential consequences as a component of simultaneous prompting probes. Moreover, Brown and Cariveau (2022) reported that only two of the reviewed studies conducted probes in extinction (Klaus et al., 2019; Riesen et al., 2003). It is unclear whether differential consequences during probes may facilitate the development of stimulus control, which may be a meaningful area of future research.

A second limitation is the inclusion of a less stringent mastery criterion (i.e., one daily probe session at 100%) than is recommended in recent reviews of the literature (e.g., Wong et al., 2022). Notably, the participants’ performances maintained at perfect levels during maintenance probes for eight out of 12 evaluations. It is unclear whether a more stringent mastery criterion would have contributed to greater maintenance in the remaining four evaluations, particularly as previous research on selecting mastery criteria has almost exclusively included children with developmental disabilities (McDougale et al., 2019; Wong et al., 2022). Future research is needed to determine whether similar mastery criteria may be needed to promote durable responding by children without developmental disabilities. Additionally, we did not assess for the generalization of intraverbal synonyms or the emergence of untrained (e.g., symmetrical/reverse) relations, which may be fruitful areas of future research. Finally, we included modifications based on a participant’s performance using variables that were inconsistently recorded by data collectors (e.g., type of error). These data informed our modifications; however, researchers and practitioners would benefit from a more explicit delineation of the decision-making process to select a particular procedural modification.

Additional research is needed in several domains. First, the current study serves as a preliminary evaluation of intraverbal training using a simultaneous prompting procedure. Only Akmanoglu et al. (2015) taught intraverbals using simultaneous prompting previously, so additional research is needed. Researchers might also evaluate (a) the influence of prompt type on instructional gains using simultaneous prompting procedures, (b) whether the emergence of untrained (e.g., symmetrical or transitive) relations may be shown following intraverbal synonym training, (c) the role of antecedent-based procedural modifications in the efficiency or efficacy of simultaneous prompting procedures, and (d) the efficacy of similar simultaneous prompting procedures on the acquisitions of other intraverbal targets (e.g., intraverbal associations or fill-ins).

The current study serves as a demonstration of the efficacy of intraverbal training using a simultaneous prompting procedure and echoic prompts for six children at risk for reading failure. We extended previous research on simultaneous prompting by including procedural modifications that may retain the potential errorless development of stimulus control. Finally, we included participants that are understudied in research on simultaneous prompting and more broadly in the behavior-analytic literature. Although additional research is needed, the current findings suggest that simultaneous prompting may represent an emerging method to target verbal or other academic repertoires of children at risk for reading failure both with and without developmental disabilities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Marina Coutros, Lilly Wooten, Amy Doyle, Darcy Hill, Cassidy Montgomery, and Katie Grelck for their assistance with various parts of this study.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declaration

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

This research was approved by an Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained before participation began.

Conflicts of Interest

Tom Cariveau currently serves on the editorial board of The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. All remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aguirre AA, Valentino AL, LeBlanc LA. Empirical investigations of the intraverbal: 2005-2015. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2016;32:139–153. doi: 10.1007/s40616-016-0064-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akmanoglu N, Kurt O, Kapan A. Comparison of simultaneous prompting and constant time delay procedures in teaching children with autism the responses to questions about personal information. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice. 2015;15(3):723–737. doi: 10.12738/estp.2015.3.2654. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Axe JB. Conditional discrimination in the intraverbal relation: A review and recommendations for future research. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2008;24:159–174. doi: 10.1007/bf03393064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A., & Cariveau, T. (2022). A systematic review of simultaneous prompting and prompt delay procedures. Journal of Behavioral Education. Advance online publication

- Coon JT, Miguel CF. The role of increased exposure to transfer-of-stimulus-control procedures on the acquisition of intraverbal behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2012;45(4):657–666. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2012.45-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly D, Dounavi K. A comparison of tact training and bidirectional intraverbal training in teaching a foreign language: A refined replication. The Psychological Record. 2020;70:243–255. doi: 10.1007/s40732-020-00396-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dounavi K. A comparison between tact and intraverbal training in the acquisition of a foreign language. European Journal of Behavior Analysis. 2011;12(1):239–248. doi: 10.1080/15021149.2011.11434367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emmick JR, Cihon TM, Eshleman JW. The effects of textual prompting and reading fluency on the acquisition of intraverbals. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2010;26:31–39. doi: 10.1007/BF03393080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenot B, Uwayo M, Avendano SM, Ross D. A descriptive analysis of applied behavior analysis research with economically disadvantaged children. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(4):782–794. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00389-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith TR, LeBlanc LA, Sautter RA. Teaching intraverbal behavior to children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2007;1:1–13. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2012.45-657. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys T, Polick AS, Howk LL, Thaxton JR, Ivancic AP. An evaluation of repeating the discriminative stimulus when using least-to-most prompting to teach intraverbal behavior to children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46(2):534–538. doi: 10.1002/jaba.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingvarsson ET, Hollobaugh T. A comparison of prompting tactics to establish intraverbals in children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44(3):659–664. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingvarsson ET, Le DD. Further evaluation of prompting tactics for establishing intraverbal responding in children with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2011;27:75–93. doi: 10.1007/BF03393093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisamore AN, Karsten AM, Mann CC, Conde KA. Effects of a differential observing response on intraverbal performance of preschool children: A preliminary investigation. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2013;29:101–108. doi: 10.1007/BF03393127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaus S, Hixson MD, Drevon DD, Nutkins C. A comparison of prompting methods to teach sight words to students with autism spectrum disorder. Behavioral Interventions. 2019;34(3):352–365. doi: 10.1002/bin.1667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kodak T, Halbur M. A tutorial for the design and use of assessment-based instruction in practice. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2021;14:166–180. doi: 10.1007/s40617-020-00497-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodak T, Fuchtman R, Paden A. A comparison of intraverbal training procedures for children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2012;45(1):155–160. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2012.45-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukevich, D. (2008). Verbal behavior targets: A tool to teach mands, tacts and intraverbals. Different Roads to Learning.

- MacFarland-Smith J, Schuster JW, Stevens KB. Using simultaneous prompting to teach expressive object identification to preschoolers with developmental delays. Journal of Early Intervention. 1993;17(1):50–60. doi: 10.1177/105381519301700106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDougale CB, Richling SM, Longino EB, O’Rourke SA. Mastery criteria and maintenance: A descriptive analysis of applied research procedures. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;13:402–410. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00365-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland, J., Hussar, B., Zhang, J., Wang, X., Wang, K., Hein, S., Diliberti, M., Cataldi, E. F., Mann, F. B., Barmer, A., Nachazel, T., Barnett, M., & Purcell, S. (2019). The Condition of Education 2019 (NCES 2019-144). U.S. Department of Education.

- Palmer DC. On intraverbal control and the definition of the intraverbal. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2016;32:96–106. doi: 10.1007/s40616-016-0061-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MA, Schuster JW. Effectiveness of simultaneous prompting on the acquisition of observational and instructive feedback stimuli when teaching a heterogeneous group of high school students. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities. 2002;37:89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Partington JW, Bailey JS. Teaching intraverbal behavior to preschool children. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1993;11:9–18. doi: 10.1007/BF03392883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichow B, Wolery M. Comparison of everyday and every-fourth-day probe sessions with the simultaneous prompting procedure. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2009;29(2):79–89. doi: 10.1177/02711214093378855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riesen T, McDonnell J, Johnson JW, Polychronis S, Jameson M. A comparison of constant time delay and simultaneous prompting within embedded instruction in general education classes with students with moderate to severe disabilities. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2003;12(4):241–259. doi: 10.1023/A:1026076406656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster JW, Griffen AK, Wolery M. Comparison of simultaneous prompting and constant time delay procedures in teaching sight words to elementary students with moderate mental retardation. Journal of Behavioral Education. 1992;2:305–325. doi: 10.1007/BF00948820. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg ML, Partington JW. Teaching language to children with autism and other developmental disabilities. AVB Press; 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekin-Iftar E, Olcay-Gul S, Collins BC. Descriptive analysis and meta analysis of studies investigating the effectiveness of simultaneous prompting procedure. Exceptional Children. 2019;85(3):309–328. doi: 10.1177/0014402918795702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- University of Oregon (2020). 8th Edition of Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS®): Administration and Scoring Guide. University of Oregon. Available: https://dibels.uoregon.edu

- Vedora J, Conant E. A comparison of prompting tactics for teaching intraverbals to young adults with autism. The Analysis of Verbal behavior. 2015;31:267–276. doi: 10.1007/s40616-015-0030-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedora J, Meunier L, Mackay H. Teaching intraverbal behavior to children with autism: A comparison of textual and echoic prompts. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2009;25:79–86. doi: 10.1007/BF03393072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waugh, R. E., Alberto, P. A., & Frederick, L. D. (2011). Simultaneous prompting: An instructional strategy for skill acquisition. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 46(4), 528–543. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24232364

- Wong, K. K., Fienup, D. M., Richling, S. M., Keen, A., & MacKay, K. (2022). Systematic review of acquisition mastery criteria and statistical analysis of associations with response maintenance and generalization. Behavioral Interventions, 1–20. 10.1002/bin.1885

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.