Abstract

An intraverbal assessment was administered to older adults with aphasia, using a hierarchy of questions that required increasingly complex verbal discriminative stimulus control. Five categories of errors were defined and analyzed for putative stimulus control, with the aim to identify requisite assessment components leading to more efficient and effective treatments. Evocative control over intraverbal error responses was evident throughout the database, as shown by commonalities within four distinct categories of errors; a fifth category, representing a narrow majority of errors, was less clear in terms of functional control over responses. Generally, questions requiring increasingly complex intraverbal stimulus control resulted in weaker verbal performance for those with aphasia. A new 9-point intraverbal assessment model is proposed, based on Skinner’s functional analysis of verbal behavior. The study underscores that loss or disruption of a formerly sophisticated language repertoire presents differently than the fledgling language skills and errors of new learners, such as typically developing children and those with autism or developmental disabilities. Thus, we would do well to consider that rehabilitation may require a different approach to intervention than habilitation. We offer several thematic topics for future research in this area.

Keywords: Aphasia, Brain injury, Language skills, Speech, Stimulus control

The term acquired brain injury (ABI) encompasses many kinds of trauma after birth. One dominant category of ABI is cerebral vascular events (i.e., ischemic or hemorrhagic strokes), with 12.2 million new strokes occurring each year worldwide (World Stroke Organization, 2022). The condition is no longer restricted to the elder population; over 62% of all strokes occur in people under 70 years of age and 16% occur in people between 15 and 49 years. Regardless of age, the resulting economic, societal, and personal consequences can be severe, arguably due primarily to the devastating loss of the ability to communicate effectively.

About one-third of all strokes result in aphasia, a broad disability category describing disrupted language abilities of speaking, reading, writing, comprehension, gesturing, and other behaviors that generally define “language skills,” (American Speech Language and Hearing Association [ASHA], n.d.). Aphasia manifests itself along a continuum of severity, with some aphasias evincing only occasional verbal stumbles and others characterized by severe or near-total inability to communicate through any mode (e.g., speaking, writing, gesturing).

The breadth of language difficulties in aphasia has been variously classified (see Becker & Baltazar, 2021 for a review), but current descriptions overlap considerably in component skills and deficits. For example, according to the Aphasia Classification Chart (ASHA, n.d.), repetition is a characteristic skill deficit in not just one category, but in four: Broca’s aphasia, global aphasia, conduction aphasia, and Wernicke’s aphasia. The same skill is said to be at strength in three different categories: transcortical motor aphasia, anomic aphasia, and transcortical sensory aphasia. Thus, knowing the aphasia category does not necessarily reveal which skills are disrupted nor whether performance on aphasia tests can be accurately predicted from these classifications. The problem is complicated by the fact that terminology may be confusing. For example, fluent aphasia does not require effective, adaptive (i.e., functional) language skills, as a behavioral interpretation of fluent suggests (e.g., performance at mastered, automaticity level; see Binder, 1996). Instead, a person with fluent aphasia is described on the Aphasia Classification Chart (ASHA, n.d.) as being “able to produce connected speech [but] …Sentence structure …lacks meaning.” Similarly, word finding, which connotes disrupted fluency, is listed as characteristic of conduction aphasia and anomic aphasia, both of which fall within the fluent aphasia category. Such overlaps make it difficult to select aphasia assessments and subtests that will be most useful to pinpoint specific language deficits for a given individual. Moreover, these issues are exacerbated by urgency to intervene, as some evidence suggests aphasia may be most amenable to intervention within only a limited timeframe (Dromerick et al., 2021).

Standard approaches to aphasia assessment primarily focus on two types of tools. Comprehensive standardized tests (e.g., Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Evaluation [BDAE]; Goodglass et al., 2001) survey specific language skills, whereas informant assessments aim to identify how effectively a person communicates in everyday situations according to their own judgment or that of family members and familiar others (e.g., Communicative Effectiveness Index; Lomas et al., 1989). In the case of standardized tests, these are designed to assess performance across a broad array of verbal skills. For example, the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB-R; Kertesz, 2007) assesses Spontaneous Speech (Conversational Questions, Picture Description), Auditory Verbal Comprehension (Yes/No Questions, Auditory Word Recognition, Sequential Commands), Repetition, and Naming and Word Finding (Object Naming, Word Fluency, Sentence Completion, Responsive Speech). Other standardized assessments (e.g., BDAE; Boston Naming Test; Kaplan et al., 1983) probe additional language-related responses such as reading, writing, grammatical adherence, and gestures.

Similar to standard language tests for those with autism and developmental disabilities, current assessments for aphasia track response errors via subtests that classify formal (e.g., topographic) and structural (e.g., grammatical) aspects of verbal behavior. As with the other disorders, these assessments pinpoint general categories of weakness (e.g., reading/writing problems; errors with pronouns or verb tense). However, tests that yield only identification of response errors may be insufficient to guide effective treatment planning. What is lacking is context, an explication of the stimulus conditions that account for the occurrence of these errors. Without this knowledge, the verbal behavior of persons with aphasia may seem incomprehensible or unpredictable, as when they can utter a word or phrase in one situation but not in another. As Becker and Baltazar (2021) note: “Such patients do not suffer from a missing or damaged response, but rather an altered relation between stimulus conditions and the response” (p. 4). The authors cite (p. 4) the experience of one individual (see Broussard, 2015) who kept a diary of his recovery from aphasia:

I assumed that lost cells were somehow equivalent to lost words…Almost immediately, though, I also began to observe that there were few words lost. However, many words were flawed in one way or another (p. 47)…I could spell and pronounce each day of the week. But what had become an issue was the sequence of each day (p. 24). I read…out loud, assuming this would help me read better. But I made more errors reading “out loud” than by speaking (p. 145). Sometimes I couldn’t find one letter or another, yet could find it again in different applications. A deficit in one place may very well have been undamaged in another. (pp. 30-31)

The particulars of these seemingly arbitrary instances of failure and success are critical to identify because therein are the stimulus conditions (i.e., antecedent and consequent contexts) that explain verbal behavior (or lack of) and point us toward effective ways to strengthen needed repertoires.

This type of contextual evaluation, termed functional assessment (Cooper et al., 2020), has been used to assess language skills of those with autism and developmental disabilities (e.g., Partington, 2006; Sundberg, 2014), augmenting and expanding standardized assessment information by providing a mechanism for analyzing responses that appear to be “wrong.” Despite the lack of error analysis in standard speech-language assessments (Esch et al., 2010), there is value in considering its addition. Traditional assessments can identify language skills that are disrupted, but not the extent of the disruption in terms of its resistance to change. A complete picture would identify intact nonverbal and verbal skills (i.e., functional relations) that might assist in evoking correct responses, as well as those which offer no additional benefit. Without this contextual analysis, we have an incomplete account of why a response occurred. For example, upon hearing a person say “pickle,” we cannot be certain if the speaker wants one, sees or smells one, is reciting words that rhyme with ‘tickle,” or is reading a billboard for gherkins and dills. We look for clues to understand what evoked the utterance in the first place; in other words, to define the function of the response in this particular instance. In doing so, we emphasize the value of contextual analysis, recognizing that any response in the absence of such analysis is not sufficient to guide our efforts to remediate that response when it occurs “in error.”

Skinner (1957) provided an analysis of these contexts of verbal operants, defined by unique antecedent-consequent relations as functional context for verbal behavior. That is, when different stimuli evoke a common response, those evocative contexts are considered as separate verbal functions. In the case of “pickle,” the response could be variously evoked, for example (a) given motivating conditions (mand), (b) under conditions where nonverbal (e.g., visual, olfactory) stimuli impact the senses (tact), (c) upon hearing someone else say the same word (echoic), (d) in response to other verbal stimuli, like questions or comments (intraverbal), or (e) when reading the letters PICKLE written on a card (textual).

Although much of the functional assessment application has been with children and other early language learners, there is evidence that this type of evaluation can yield useful information not available through standard assessments for adults, specifically those who have experienced language loss after long communication histories with well-established verbal repertoires (e.g., Dixon et al., 2011; Gross et al., 2013; Oleson & Baker, 2014; Sundberg et al., 1990). In fact, there may be an assessment and treatment advantage with this population of experienced language learners. Those who are still acquiring basic language skills (e.g., children) may have few alternative responses available when skills are weak; if they cannot “name an animal that can fly,” they may be limited in responding to any other verbal stimuli involving “animal” or “fly.” Adults, on the other hand, have had years of experience talking about animals of all sorts as well as many things that fly. Thus, despite skills weakened due to ABI, it may be possible to evoke accurate responses more easily with this population, by identifying alternative stimuli related to those that resulted in failed (error) responses. That is, there may be unimpaired residual neural connections that allow certain stimulus conditions to prevail such that incipient error responses are circumvented and more effective responses can come to strength and be uttered. As Donahoe and Palmer (1994) note: “Some verbal functions may be localized, but considering the diversity of variables that control verbal responses, it is likely that the physical mechanisms mediating verbal behavior are widely distributed in the nervous system” (p. 300). Consequently, rehabilitation of disrupted language skills may have an advantage over habilitation of new repertoires through functional (i.e., contextual) assessment that enables us not just to identify response errors, but to identify and capitalize on strengths that remain among variables that control verbal functions (e.g., mand, tact, intraverbal, textual, echoic; see Skinner, 1957) and to test their utility as transfer agents from one function to another. Such a focus on error analysis in conjunction with error identification could guide a more integrated approach to language rehabilitation and improve intervention outcomes for those with ABI.

The current study focuses on the intraverbal relation, a functional unit in which verbal stimuli evoke a verbal response that has no formal similarity nor point-to-point correspondence with the evocative stimulus (Skinner, 1957; Sundberg, 2020). Examples include answering questions, engaging in conversations, describing activities and experiences, verbal problem solving, and recall. Failure to initially acquire intraverbal behavior—as is often seen in autism or developmental disabilities—or to repair acquired-but-disrupted intraverbal repertoires—as in aphasia—is likely due to the complexities, arrangements, and interactions of stimuli involved in strengthening the intraverbal relation. This myriad of stimuli, in the form of verbal stimulus discriminations, presents several unique challenges to assessment and treatment of impaired intraverbal behavior. One is the transitory nature of (spoken) verbal behavior, with speech (i.e., auditory) stimuli having salience for only a few seconds, as one spoken word is quickly followed by another and then another. In addition, the intraverbal relation, in its purest form, is verbal; it is independent of (but not necessarily free from) physical environmental supports (e.g., pictures, objects) to establish or maintain responding. Thus, acquisition of pure intraverbals may be at a disadvantage when verbal-only repertoires are weak because of insufficient learning history (e.g., young children) or weakened because of neurological damage (e.g., as in aphasia).

Perhaps most challenging is the complex nature of verbal discriminations themselves. Stimulus control may arise from and depend upon multiple sources, including compound verbal stimuli (e.g., “brown” and “dog”), verbal conditional stimuli (e.g., “which one is not a fruit”), or combinations of these (“name a big red fruit and a little yellow vegetable;” see Axe, 2008; Michael et al., 2011; Sundberg, 2016). In addition, verbal discriminative stimuli are not, and need not be, reliably linked (e.g., the word brown does not always precede the word dog), unlike stimuli controlling some other types of verbal behavior. For example, physical (nonverbal) stimuli that evoke tacts such as coffee aroma and “coffee” or two ears, fur, and a tail and “dog” typically occur together. Similarly, mands are reliably preceded by a motivating stimulus (e.g., “I’m hungry” does not usually occur when a person is full). By contrast, any number of verbal stimuli might evoke the intraverbal response “cookie” (e.g., what’s in your lunchbox; read this word COOKIE; what does c-o-o-k-i-e spell; does your dog have a name; tell me a 6-letter word that starts with C), none of which is required or predictable, except within a unique context. Of course, this does not mean that intraverbal behavior must be emitted without supplemental stimulus control (e.g., nonverbal stimuli; motivating operations); indeed, it is unlikely that the bulk of our intraverbal behavior is “pure” and free of such control. Our communication environments abound with other stimuli (e.g., physical objects, noises, texts, odors, tactile sensations, states of motivation) that are coincidentally salient with the multitude of verbal stimuli that evoke our verbal responses. Thus, the task of intraverbal assessment is weighty and demands that test design takes into account the continuum of stimulus variables active in assessing and establishing intraverbal control.

Although there is no intraverbal assessment for persons with aphasia, an intraverbal assessment by Sundberg and Sundberg (2011) provided a path to creating one. In Sundberg and Sundberg, participants were typically developing children and those with a diagnosis of autism. Their original assessment was designed to capture the influence of stimulus control on a continuum, from simple discriminative control (i.e., rote-learned responses, or “true” intraverbals, Palmer, 2016) to control exerted by the convergence and divergence of multiple discriminative stimuli, in the form of compound stimuli (e.g., what animal is big), verbal conditional stimuli (e.g., name an animal that can walk and swim), and combinations thereof. Eight groups of increasingly complex stimuli (e.g., open-ended phrases, fill-in-the-blank, WH questions) were presented. Question groups 1 through 3 evaluated rote-learned intraverbal responses, and the remaining groups presented questions requiring multiple stimulus control and some degree of mediated verbal problem solving or recall behavior. The authors reported data showing that performance tended to degrade as the stimulus control for accurate intraverbal responses became more complex. There was generally an “accuracy fracture point” at groups 3 and 4 with younger children, where rote-learning was no longer sufficient for a correct response. That is, multiple stimulus control in the form of verbal conditional discriminations was needed to make non-rote responses that did not have a specific reinforcement history (e.g., What’s in a house; What day is today; How do you know if someone is sick; What do you do with money).

At present, there are no extant descriptions of a similar hierarchical intraverbal skills assessment with ABI individuals. A starting place is to probe, identify, and track stimulus control elements that have been preserved post-ABI, either those producing exact targeted responses or as sources of control to be subsequently faded as intraverbal control is strengthened. Effectively, this would identify “the fault lines of possible stimulus-control problems” (Palmer, personal communication, January 10, 2022). Behavior analysts have begun this task; models and recommendations have been put forth for more pinpointed, behavioral approaches to language assessment and treatment for persons with aphasia, dementia, or other ABI (e.g., Baker et al., 2008; Becker & Baltazar, 2021; Dixon et al., 2011; Gross et al., 2013; Sidman, 1971) and specific training techniques have been articulated (e.g., Binder, 1996; Haughton, 1980; Lin & Kubina Jr., 2004; Ritchie et al., 2021; Valentino et al., 2012; also see Aguirre et al., 2016).

The current study modified the Sundberg and Sundberg (2011) intraverbal subtest for a population of adults with aphasia to determine if it revealed loss of the intraverbal function for this demographic, and, if so, how the complexity of verbal stimulus control might be related, specifically how increasing complexity might evoke particular types of errors. Ultimately, our goal is to find components of intraverbal stimulus control that should be included in assessments and to propose a new model comprising such components, designed to lead to more effective and targeted interventions for this population.

Method

Participants and Setting

Participants were attendees at a community-based aphasia communication group for adults. They all had experienced some form of ABI but were no longer receiving active medical treatment (acute, sub-acute, or rehabilitation services) related to the brain injury or its sequelae. Prior to their ABI, participants were able to effectively communicate in English. Self-referral to the communication group was typical, although some had been referred by their family doctor or speech pathologist. The intraverbal assessment was part of the intake assessment package for all attendees in the communication group. Thirty-eight participants initially started the assessment, but two requested to discontinue before finishing. Therefore, we included 36 completed data sets in the descriptive analysis. Participant age ranged from 51 years to 83 years, with a median age of 65 years. Referral diagnoses were variously stated by (a) loci of damage (e.g., left middle cerebral artery cerebral vascular event [L MCA CVA]), cerebral hemorrhage, MCA infarct, temporal lobe hemorrhage, cerebellar stroke, ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, left basal ganglia stroke, left temporal parietal CVA); (b) some form of aphasia (e.g., aphasia, fluent aphasia, Wernicke’s aphasia, conduction aphasia resolving to anomia and aphasia, Primary Progressive Aphasia); or (c) speech disruptions (e.g., word-finding difficulties, dysarthria, communication deficits, ataxic speech, apraxia of speech).

Sessions were conducted in small private rooms in community meeting buildings where the aphasia communication groups were offered. Rooms were all similar, containing a small table, chairs, and miscellaneous items (e.g., fan, stored TVs, phone). Test administrators used a clipboard, paper, and pen to record participant responses. Sessions were not videotaped. The participant and test administrator were alone in sessions, except when an observer was present for data collection for interobserver agreement and procedural integrity. The assessment was completed within a single session; median session duration was 19.5 minutes (range, 12 min to 54 min). Breaks were offered periodically, although these were usually declined.

Assessment Stimuli

The assessment was formatted similarly to that of the Sundberg and Sundberg (2011) Intraverbal Subtest, with eight “mini-tests” of 10 questions each, presenting increasing levels of complex verbal stimulus control along five general dimensions: (a) transition from simple (rote-learned) to conditional verbal discrimination (VCDs); (b) WH (or similar) questions in true VCDs; (c) increasing complexity of parts of speech, from nouns and verbs, to adjectives, prepositions, and pronouns; (d) increasing complexity of concepts such as negation, relative adjectives, and time; and (e) increasing complexity of vocabulary words included in the various questions (Table 1). All stimuli were deemed appropriate for the demographic (i.e., adult, verbally competent pre-ABI) by speech pathologists familiar with the participants. All items were presented vocally in English and were repeated as needed (see Procedure below).

Table 1.

Intraverbal assessment test items by set

| Set | Items | Alternates |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Common Fill-ins |

A cat says… Twinkle, twinkle, little… Ready, set… How are… A cow says… A dog says… I don’t like jazz music; I like rock and… Have a nice… Tell me yes or… Happy birthday to… |

From start to… Nice to meet… |

| 2. Name, Fill-ins, Associations |

What is your name? You brush your… Shoes and… You ride in a… You flush the… You sleep in a… You eat… One…two… You wash your… You sit on a… |

Cream and… Salt and… |

| 3. Simple What Questions |

What can you drink? What can fly? What are some numbers? What can you sing? What’s your favorite movie (or song)? What are some colors? What do you read? What is outside? What’s in a kitchen? What are some animals? |

What are some stores? What do you wear? |

| 4. Simple Who, Where, and Age |

Who is your friend? Where do you wash your hands? Who is in your family? Where is the refrigerator? Who drives a car? Where do you take a bath (or shower)? How old are you? Where are trees? Who do you see on TV? Who works in a school? |

Who cleans teeth? Where are birds? |

| 5. Categories, Function, Features |

What shape are wheels? What grows outside? What can sting you? What do you do with a sock? What melts? What do you do with a straw? What do you write on? What are some body parts? What is something that’s sharp? What do you wear on your head? |

What shape is a box? What’s something that is soft? |

| 6. Adjectives, Prepositions, Adverbs |

What color is my hair? What do you eat with? What’s up in the sky? What’s above a house? What do you smell with? What are some things that are hot? What grows on your head? What is under a boat? What animal can swim? What do you write with? |

What is on a bed? What animals are slow? |

| 7. Multiple-part Questions I |

What makes you sad? Name some clothing. Tell me something that is not a food. What helps a flower grow? When do we set the table? What do we use money for? Why do people wear glasses? Where do you put dirty clothes? What is something that you can’t wear? What’s something that is sticky? |

What animal can walk and swim? Why do people read books? |

| 8. Multiple-part Questions II |

What is inside a balloon? What do people take to a birthday party? Where do people go if they feel sick? Why do people wear coats? What do you do before getting into bed at night? What day comes before Tuesday? What can you put in a sandwich? What musical instrument has strings? What do you do with an umbrella? Why do people buy gas? |

What can you do with chocolate chips? Why do we pay taxes? |

Items are adapted from Sundberg and Sundberg (2011)

Response Measurement, Interobserver Agreement, and Procedural Integrity

Experimenters recorded participants’ verbatim responses on the data form for each set. Sets were administered sequentially, and each set included 12 questions. Ten questions were scored, but an additional two questions were administered in the event that any responses (up to two) within the first 10 questions were unclear (e.g., muffled), the question did not evoke a response, or a participant responded “I don’t know.”

Experimenters scored correct responses. A correct response was defined according to two related rubrics. First, any answer that would likely contact reinforcement in typical discourse was scored as correct. For example, in response to What can you eat, variations such as “sandwich,” “breakfast,” or “food” were all scored correct. Other examples of correct responses included: What do you write with (a pen; my hand); What can sting you (a bee; a man); What do you do with a sock (wear it; make a puppet); What’s on a bed (a sheet; a mess); and One, Two… (three; two and a half, ha ha). Second, we obtained a database of vocal–verbal responses to our assessment questions from 13 English-speaking adults (age range, 51–85 years; Mdn = 72 years) with no history of ABI; thus, these individuals were considered fluent, typical speakers. This database (data are not included) provided extensive samples of responses that, because they were emitted, presumably had a reinforcement history that met our definition of “reinforceable in typical discourse.” We used the sample response database as a comparative reference for participant responses. That is, if a participant response topography matched any of those in the typical sample database, these were considered correct responses. If not, those responses were scored as incorrect and were analyzed further as part of the error analysis.

Negative responses (i.e., “I don’t know” or no response) triggered a repeated presentation of the question. If another negative response occurred following re-presentation, the response was scored as an error. All other responses were counted as errors (see Table 2). In the error analysis, we aimed to pinpoint stimulus control for responses ranging from rote-learned (simple discriminations) to those requiring control by multiple verbal elements (VCDs). Therefore, we defined categories of response errors according to common elements of possible verbal stimuli evoking those responses. It should be noted that the term “error” is used for convenience of discussion, recognizing that any response may be considered accurate in the sense that past learning history and prevailing controlling variables could likely predict certain responses. Table 2 shows participant errors and examples classified into five types of possible stimulus control: (a) Atypical responses gave little notion of presumptive control; (b) Echoic responses contained fragments (or all) of the auditory stimulus; (c) Partial (i.e., “ballpark”) answers indicated the response was under the stimulus control of some, but not all, of the required elements; (d) General responses were non-specific or all-encompassing, suggesting relatively weak stimulus control for certain verbal functions (e.g., autoclitics and tacts) within intraverbal frames; and (g) Phonemic or Gestural, a category of “other” responses that indicated strong stimulus control for accurate responding, but illustrated disrupted vocal–verbal skills as an output channel (see Baker et al., 2008; Haughton, 1980; Lin & Kubina Jr., 2004).

Table 2.

Error classifications

| Error Type | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Atypical | Response is without any indication of stimulus control source |

Replies Fur to “Shoes and…?” Replies Together to “What are some animals?” |

| Echoic | Response contains echoic components or fragments of the verbal stimulus; may contain self-echoics |

Replies In the fridge to “Where is the refrigerator?” Replies Shoelaces slay lazes to “Shoes and …” |

| Partial (Ballpark) | Response indicates some, but not all, sources of required multiple stimulus control |

Replies Use it to eat milk to “What do you do with a straw?” Replies A bird, a human to “What can you sing?” Replies Brush to “Who cleans teeth?” |

| General | Response indicates weak stimulus control for specificity; response may be grammatical |

Replies Lots of things to “What is outside?” Replies Where it’s supposed to be to “Where is the refrigerator?” |

| Phonemic or Gestural | Response contains phonemic or gestural elements of a correct response |

Replies sar, skar, star to “Twinkle, twinkle, little…” Replies spood to “You eat…” Points to tissue box when asked “What is something that is not a food?” |

We obtained interobserver agreement data on participant responses, accuracy, and error categorization in the error analysis. Two independent data collectors recorded the participants’ responses verbatim for seven participants (19.4% of data sets). The first author compared transcriptions from both data collectors. Agreement was defined as responses that were verbatim or that were essentially equivalent in meaning (e.g., “it’s like this” and “like this;” “put it on” and “you put it on”). A disagreement was scored if the two data collectors recorded responses that were not essentially equivalent (e.g., “a ball” and “a bowling ball”). For each set, interobserver agreement (IOA) for responses was calculated by summing the number of agreements, dividing by total agreements plus disagreements, and multiplying by 100 to obtain a percentage. Mean agreement was 98.6% (range, 92.5–100%).

Two additional data collectors independently scored the participants’ responses as correct responses or errors for 22 participants (i.e., 61.1% of data sets). An agreement was scored if both data collectors scored the same response as a correct response or an error. A disagreement was scored if the data collectors did not score the same response as a correct response or an error. To calculate IOA for response accuracy, we summed the agreements, divided by the total agreements plus disagreements, and multiplied by 100 to obtain a percentage. Mean agreement was 96.6% (range, 87.5–100%) across participants.

Two data collectors independently categorized 170 error responses (i.e., 34.2% of errors), according to error type (Atypical, Echoic, Partial, General, and Phonemic or Gestural). An agreement was scored if both data collectors scored the same error response in the same error category. A disagreement was scored if the data collectors did not score the same error response in the same error category. To calculate IOA for error categorization, we summed the agreements, divided by the total agreements plus disagreements, and multiplied by 100 to obtain a percentage. Mean agreement was 92.9% (range, 81.8–100%) across error responses.

To assess procedural integrity, an independent observer scored three data sets (8.3%) for measures of testing implementation. Accurate testing implementation was defined as the test administrator reading test items as written on test form and praising/acknowledging every response. Procedural integrity for implementation measures was 100%; the test administrator implemented all steps of the test correctly.

Procedure

The assessment was completed in order to evaluate intraverbal repertoires of adults with a history of ABI. The assessment included eight sets of 12 questions each (see Table 1) and was administered during the standard intake interview. The sets required increasing levels of complex verbal stimulus control, from simple discriminations to conditional verbal discriminations in which multiple verbal antecedents are present and one (or more) of these alters the evocative effect of another.

Test administrators were speech-language pathologists who worked with the ABI communication group and had at least 5 years of experience. They presented questions sequentially, transcribed responses by hand, and acknowledged or praised (“ok,” “great,” “uh-huh”) each response regardless of accuracy. If a participant replied “I don’t know” or if there was no response, the administrator repeated the question one time. If a participant said “Skip” or “Pass,” the tester proceeded to the next item. All participants completed the assessment in a single session.

Results

Performance overall was high across the 80-point intraverbal subtests (Mdn = 76). Figure 1 shows composite test scores (sets 1 through 8) for all 36 participants. Half of the participants (n = 19) emitted no more than four errors (participants 17 to 36) on the 80 test items, and some participants (n = 8) made no errors (participants 28 to 36). For this group of responders, results suggest that this particular tool was not useful to identify potential treatment needs. The other half of the participants (n = 17) showed greater variability in scores (range, 16–73; Mdn = 56; participants 1 to 16), indicating difficulty responding to items requiring particular types of stimulus control across the intraverbal subtests. Specific errors and their relation to the unique stimulus conditions presented are discussed below.

Fig. 1.

Total score for each participant. Note. Participants are ordered from lowest to highest score and not in order of test completion. The numbers above each bar represent the total score

As noted earlier, participants’ diagnoses were not consistent in terms of aphasia type, so no conclusions can be drawn about performance according to this classification. Similarly, descriptive diagnoses did not predict performance. For instance, one individual diagnosed with word-finding problems had a perfect score on the test. Another with aphasia and apraxia of speech made only one error and was able to give sophisticated responses to questions requiring complex verbal stimulus control (e.g., Why do we pay taxes? “To fund the school and government programs”). Still another, diagnosed with anomic aphasia (i.e., unable to recall names of everyday objects or “word-finding”) named 18 appropriate items in response to naming questions (e.g., What can fly, What’s in a kitchen, What are some stores). Physical area of brain damage did not appear correlated. For example, participants whose ABI diagnoses included the words “left middle cerebral artery” had total scores that ranged widely (24–78, out of 80), indicating that locus of damage was not predictive of performance on this assessment.

Error Analyses

An error analysis was conducted to (a) determine whether test items requiring increasingly complex verbal conditional discriminations were more difficult than those under simple discriminative control and (b) to identify possible sources of stimulus control for these errors. Five different types of response errors were defined: Atypical, Echoic, Partial, General, and Phonemic or Gestural (see Table 2), with an effort to identify control for the responses evoked by the test items.

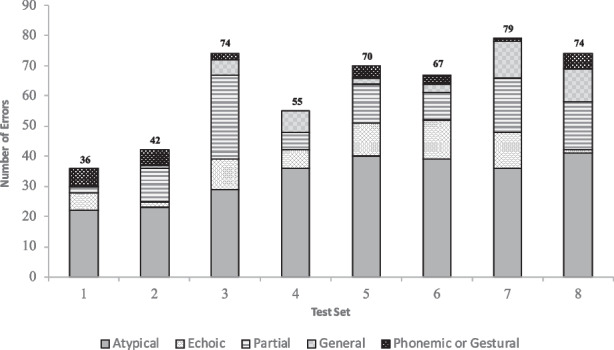

Figure 2 shows the frequency of errors across intraverbal assessment test items by set. The fewest errors were made to items in Set 1 (common fill-ins; n = 36), which is not surprising because this set assessed rote-learned “true” intraverbal responses for which complex stimulus control and verbal problem solving was not required. The greatest number of errors occurred in three sets: set 3 (simple What questions; n = 74), set 7 (multiple part questions I; n = 79), and set 8 (multiple part questions II; n = 74). Participants emitted more errors to questions on set 3 than sets 4, 5, and 6, even though the subsequent set required more complex stimulus control to respond correctly. Therefore, test performance did not show linear systematic decrement as a function of required stimulus control complexity across the sets of test items. Nevertheless, data in Fig. 2 show that such a decrease in performance was generally demonstrated as the participant moved through the assessment. That is, participants were more likely to err on questions in the higher-numbered sets than lower-numbered sets. These data suggest that, when more complex intraverbal stimulus control was required for accurate responding, it presented a more difficult task (i.e., more errors occurred) for those with aphasia.

Fig. 2.

Response error distribution. Note. This figure shows distribution of error responses in each test set, according to error category. Error categories refer to possible stimulus control for responses. Aggregate errors per test set appear in bold above each test set

Figure 3 shows the frequency of each error type, and these data are aggregated across sets. Across 2880 participant responses on the eight subtest sets, there were 497 error responses (17.3%) distributed among the five error categories. When conducting the error analysis, we found that a narrow majority of errors (53.5% or 266 responses; Fig. 3) fell into the Atypical category, where evocative stimulus control was undetermined; that is, responses gave little indication of what precipitated them. Examples included responses such as You ride in a…(“Major”); What melts? (“Cell”); Why do people buy gas? (“To charge the calls”); Name some clothing (“We’ve got some groupin groupin”).

Fig. 3.

Total errors by classification. Note. This figure shows error frequency across types of error responses (n = 497). Bars indicate total for all participants, according to defined error categories

Partial error responses, where only some of the required stimuli appeared to control responding, accounted for 20.7% (103 responses; Fig. 3), the second largest percentage of error types. We defined Partial categorical errors as those where simple stimulus control was clearly evident, but more complex control (e.g., convergence of multiple stimuli) was weak or difficult to discern. For example, intraverbal control over grammatical forms was lacking in responses such as You ride in a (“bike”); What do you do with a sock? (“I take it at side my foot”); Who works in a school? (“A teachers”). Similarly, common-phrase units were affected, as seen in responses to Shoes and… (“slippers, gloves, purse”); A dog says…(“meow”); or Have a nice… (“Are you?”). Partial (weak) conditional stimulus control also typified responses where only some, but not all, relevant stimuli evoked a response: What do you write on? (“pen”) and What’s something that you can’t wear? (“Socks, shirt”).

The remaining errors were categorized as Echoic, General, or Phonemic or Gestural. Errors involving Echoic responses represented 12.3% (61 responses; Fig. 3) of total errors. Echoic errors were so labeled because auditory products of these responses contained echoic components (fragments or all) of the evocative stimulus (e.g., A dog says… “a dof, a dof”). General error responses (n = 41) represented 8.2% of total errors. The General category was designated for responses that were non-specific (e.g., “where it’s supposed to be;” “for better;” “up there;” “when it’s time;” “because”) or all-inclusive (“everywhere;” “anytime;” “a bunch of stuff”). Phonemic or Gestural responses (n = 26), with indications of adequate stimulus control (but likely requiring clarification by listener), represented 5.2% of total errors. This category allowed for grouping two other types of responses. First, some utterances contained self-echoic behavior within a quasi-intraverbal response. That is, intraverbal control was evident in the initial response products that were phonetically close-to-correct (e.g., Twinkle twinkle little…[“Sar…”]. When these were self-echoed, at times with positional adjustments of the vocal mechanism (e.g., “Sar, skar…”), this rehearsal-like behavior often produced a correct response, as in A cow says… (“Me…meow, I mean moo”).

Discussion

We assessed the intraverbal repertoires of adults with aphasia using a hierarchy of questions that required increasingly complex verbal discriminative stimulus control. Evocative control over intraverbal error responses was evident across participant data, as shown by commonalities within four distinct categories of errors (Partial, Echoic, General, Phonemic or Gestural); a fifth category (Atypical), representing a narrow majority of errors, was less clear in terms of functional control over responses. Generally, questions requiring increasingly complex intraverbal stimulus control resulted in weaker verbal performance for those with aphasia.

Rather than marking a response as correct or incorrect, identifying the types of errors (vis-à-vis putative stimulus control) could provide data to guide intervention design for verbal behavior with individuals with ABI and aphasia. Responses observed in the Echoic error category suggest that an echoic response product may have served as a controlling variable for a subsequent intraverbal response (e.g., What do you do with an umbrella? “umbrella…rain”)1. It may be a useful strategy to evoke first an echoic response, followed by re-presenting the intraverbal antecedent stimulus, which may lead to greater accuracy (strengthened by compound and/or contiguous stimuli; see Eikeseth & Smith, 2013). Furthermore, it may be that merely echoing a question is a mediating strategy, a common occurrence in daily discourse. If this occurs during intraverbal assessment, testers may decide to disregard the echoic part of a response (i.e., not label it as an error) and focus their analysis on subsequent responding. For example, What is outside? may evoke “What is outside? Um, lots of things.” In this case, only the non-echoic components of the response might be sufficient to determine stimulus control.

The Partial error category offered unique information not available through standard assessments and could be particularly useful when planning interventions. That is, it provides a framework for interpreting errors as a function of particular kinds of stimuli, in this case those that increase in complexity along the dimensions discussed earlier (also, see Sundberg & Sundberg, 2011). Unlike responses in the other error categories, responses in the Partial category are partially controlled by the “right” stimuli. Therefore, stimulus-response relations have been preserved despite ABI and, when viewed as a verbal unit (i.e., question plus answer), the faulty stimulus control may be more readily identified. For example, when an individual is asked What’s something that you can’t wear? and replies “socks, shirt,” we can identify proper control by several components of the antecedent (what, something, you, wear) and lack of control by the negation stimulus (not). Similarly, completing the phrase A dog says (“meow”) signals the salience of animal and says, but weakness of the animal set member tact (dog). With this information, follow-up probes could then test any remaining strength of what appears to be a weak stimulus and work to increase its salience. For example, echoic repertoires may be less susceptible (than intraverbal) to deterioration (Skinner, 1957; also see Palmer, 2012; Sundberg, 2016), so adding Can you repeat my question – let’s say it together – “A dog says…” may evoke a corresponding point-to-point echoic, providing increased salience of the targeted stimulus (dog), which may then control an accurate response (e.g., “bow-wow” or “arf-arf”). If an echoic of the entire phrase is not evoked, it would be a simple matter to achieve point-to-point correspondence with smaller units (i.e., word by word) or to increase salience of prosodic features of loudness, intonation, or duration (e.g., A DOOOGG says).

For errors in the General category, more specificity might be achieved with follow-up probes such as those discussed in other error categories above. Other researchers also have discussed the issue of preserving and strengthening intraverbal control to evoke more fine-grained responses (e.g., Dixon et al., 2011; Gross et al., 2013; Oleson & Baker, 2014; see also Buchanan et al., 2010), offering guidance for both assessment and program planning.

Some responses observed in the Phonemic or Gestural error category suggest behavioral processes (e.g., self-echoic) that may have implications for treatment. Phonemic errors may be resolved by establishing a practice routine (i.e., history of self-echoic and self-editing) whereby auditory-vocal matching-to-sample (perhaps with perceptual stimuli) produces a reinforceable response. Other feedback could support an individual’s attempts to “get it right” when they are struggling with their own ineffective verbal responses. For example, weak intraverbal control for “beers, no, not right” in response to What can sting you? may have strengthened if additional stimuli (e.g., textual, auditory) had been available to the participant or manded, perhaps as transcriptive behavior (i.e., Can you write the word you’re trying to say?). This approach may have resolved response errors such as “I know it but I can’t say it.” A second type of response grouped in this category was Gestural. As with phonemic responses, gestural responses were deemed, at least partly, under intraverbal control and these non-vocal behaviors (e.g., pointing, tapping, drawing, miming) were reinforceable as vocal–verbal intraverbal analogs. Examples include drawing a square when asked What shape is a box? and licking an imaginary ice cream cone in response to What melts? Such alternative “error” responses during assessment could be recruited in clinical settings as additional antecedent stimuli to promote transfer (Cihon, 2007) and to strengthen intraverbal control (e.g., evoking a tact for the drawing; What did you draw – what is that? So what shape is a box?).

Individuals with aphasia could be expected to have increased difficulty communicating as more complex verbal stimulus control is required. However, it is challenging to explain failures within a single set of items that are putatively similar in difficulty. With some participants, we saw that like-question formats (e.g., Where is; Who is) evoked both correct and error responses within the same subtest. For example, in set 3 (simple What questions), one participant answered six items correctly, failing four similarly worded questions (e.g., What are some animals; What are some numbers); another individual correctly answered What do you read, but could not respond to What is outside. Similar disparity was seen with set 4 questions (Who and Where), where a participant correctly answered Where are birds but failed Where are trees. These instances illustrate that error identification alone is insufficient to inform the content of our interventions and assumptions should not be made that related sets of particular verbal stimuli (i.e., frames, constructions) will be of comparable difficulty in evoking appropriate responses.

The problem is complicated by the multiplicity of control required in common everyday verbal interactions. For example, asking someone their “favorite foods” requires, at a minimum, that any response be under verbal stimulus control that is both divergent (i.e., name more than one food) and convergent (i.e., name favorite foods, not favorite sports) at that time, in that setting, with those unique verbal stimuli. Because of the nature of ABI, clues as to the extent of neurologic disruptions (and thus stimulus control strength) lie within responses that, as our examples show, require some detective work. In fact, we need to both identify communicative errors and analyze them in terms of prevailing stimulus control. Then, we must be prepared to make agile adjustments in those stimulus conditions (e.g., follow-up probes) to evoke more functional responses.

Case Study

A closer look at one participant’s performance across subtests reveals several possibilities regarding conditions where a verbal repertoire may become less effective and suggests ways these could be addressed. The first is intrusive control from previous test item(s). The question What can you drink evoked a response that was a re-statement of a previous item You wash your… (“What can I wash? My clothes”). If this begins to occur during testing (and treatment as well), it may be useful to insert distractor items between questions to reduce stimulus control by previous items or to increase stimulus salience by repeating the question and asking the individual to echo as a differential observing response.

The second possibility is a defective true vocal intraverbal repertoire. A sentence completion item A cow says evoked “Get ready to jump over the house,” suggesting stronger control by a nursery rhyme (“…the cow jumped over the moon”) than by the rote-learned “Moo” response to this stimulus. In this situation and others when non-standard responses are evoked, it may be helpful to have alternate or varied test items readily available. For example, our participant responded to Ready, set with “Get setting, get star, get ready, get go.” One could re-do this item (perhaps after interspersing a few other questions), not with the previous Ready, set, but instead with the stimulus that appeared to have greater salience: Get ready, get set…. In addition to different variations of questions, it may be useful to enlist prosody as a source of control by providing longer antecedents. For example, instead of Twinkle, twinkle, little …, longer phrases from the song could be presented, with opportunities to fill-in at various points (e.g., Twinkle, twinkle, little star, how I wonder what you …; Up above the world so high, Like a diamond in the …). This also might help define severity of the loss of this particular function, aiding treatment design in terms of length of stimuli that may or may not be effective to control responding.

The third consideration is that attempts at strategic mediation (i.e., verbal problem solving) may have controlled “error” responses that, at first glance, appeared to be due to defective convergent/divergent control. Alternatively, errors may have resulted from inaccurate echoic/self-echoic of the antecedent stimulus (e.g., where versus when or why). Examples included: Where do people go if they feel sick (“Probably they’ve eaten too much”); Where do you take a bath (“I do a shower every day”); Where do you wash your hands (“Wash the car”); What do you write on (“A pen”); When do we set the table (“Food”). Treatments should consider both syllable length (i.e., number of syllables) and syllable complexity (i.e., number of consonant-vowel changes) of the echoic, either vocal or subvocal, required to comprehend (i.e., listener responding; see Schlinger, 2008) and to respond to these items.

Another possibility is that there was stronger control by motivating operations (MO) than by verbal stimuli or, at the least, the convergence of the two sources of control. Examples included: What do you do before you get into bed at night (“You’re tired”); What can you do with chocolate chips (“[I] like dark chocolate”); Where do you put dirty clothes (“Have to wash them”). Inserting an opportunity to echo the original question may strengthen verbal discriminative control over any MO variables. Related to MOs, another possibility is that an MO to share personal history or information and provide any answer at all (i.e., audience control) may at least partially, account for this participant restating question formats from one that required divergent verbal stimulus control to those requiring convergence of verbal stimuli. Examples included: Name some colors (“My favorite color is blue”); What are some animals (“Cats for 40 years”); Who works in a school (“I was in [name of] University”); What are some numbers (“What’s my number? My house number or my phone number?”). In the case of the word some failing to evoke “more than one,” (e.g., some colors, some animals), a logical follow up probe might be Name three colors or Tell me four animals.

Finally, stimuli related to syntax and verbal frames, as well as specific words within the participant’s own response, may have evoked some error responses. For example, What grows on your head (“What do I hair with my hair”) and What is in a balloon (“Water, hot air in the pool”) illustrate possible sources of control supplemental to that from antecedent stimuli. These “word salad” responses are often seen in persons diagnosed with particular types of aphasia (e.g., Wernicke’s), where emitted topographies seem to evoke subsequent responses so that the entire phrase resembles a word association task. Interrupting these strings may be indicated when it is important to sharpen discriminative control by a particular stimulus (i.e., the original question). On the other hand, it may be contraindicated in situations when prioritizing the assessment and strengthening of divergent stimulus control. In sum, the foregoing in-depth analysis of one participant’s responses shows that it may be less important to train isolated tacts and mands in lieu of strengthening intraverbal frame contexts, echoic and self-echoic skills, mean length of utterance, and to toggle tasks of convergence and divergence (e.g., name one, name some) to provide needed contrast among stimuli.

Limitations

Several limitations of the study should be noted. We conducted a single assessment, so comparative data were not available for repeated participant performances. Due to the inclusion of the assessment within the intake practices of a community group for individuals with aphasia, we were not able to control for participant maturation or history such as daily verbal experiences, time since ABI onset, or the extent of any rehabilitation. In addition, we could not obtain uniform diagnostic data, so conclusions about diagnosis and performance on the intraverbal assessment are limited. As with most language assessments, our test protocol had a restricted format and, as such, likely omitted some pertinent evocative stimuli. For example, to evoke “cream and sugar,” we did not offer the context of a hot beverage with the question What do you take in your coffee/tea? Our protocol did not allow administrators to pivot when errors occurred to evoke alternative responses (e.g., gesturing, writing), although participants themselves sometimes engaged in alternative communication attempts (e.g., pointing, writing, drawing). In addition, some questions may have been contextually unclear (e.g., Who is your friend?) or the items themselves may have been unfamiliar (e.g., animal sounds, song phrases) based on the individual’s culture and learning history.

A Proposal for Developing a Behavioral Aphasia Assessment and Future Directions

The impetus for a broader behavioral aphasia assessment was the unique and important format (Sundberg & Sundberg, 2011) upon which we based the current intraverbal assessment for ABI-related aphasia. Our experience creating and conducting this test and the results from our error analysis provide an opportunity to reflect on the current assessment and suggest directions for the future of a behavioral aphasia assessment. In our study, results in the largest error category (Atypical) mirror those in standard aphasia assessments, wherein errors are identified, but alternative stimuli are not presented as follow-up probes that might evoke a correct response. As stated in our limitations, such probes were not part of our format (nor of the intraverbal subtest by Sundberg &Sundberg, 2011) but would be useful to include. Not only would follow-up probes possibly account for atypical responses, but they would permit a more thorough survey of a range of stimuli needed for subsequent interventions. In addition to follow-up probes, a revised intraverbal assessment for ABI-related aphasia could include adjusting existing test items. For example, clarification probes (e.g., What or I don’t understand or Tell me more) may result in more targeted responses. Also, it may be useful to revamp assessment items to allow contextual antecedents (e.g., Name some clothing…I’ll start and then you name some more: coat, shirt…), interspersal of alternative response mode (e.g., Name some clothing…[if no response, add selection opportunity…] Can you point to your clothing… [if pointing response occurs, then…] Right, what clothing is that?), or to present the same intraverbal frame with different required set members (e.g., Name some clothing…; if no response, then Can you name some vehicles [or animals, or buildings]). Although treatment techniques may include these types of probes, current assessments generally lack this level of stimulus-control analysis. Several researchers have begun to address these needs (e.g., Gross et al., 2013; Petursdottir & Haflidadóttir, 2009; Sundberg & Sundberg, 2011). In addition to the modifications described above, we offer a proposal for an assessment model (see Table 3) that could form the basis for new lines of behavioral research for aphasia and other disrupted language repertoires. The proposed assessment specifies nine test-probe categories based on contextual variables, emphasizing our priority of identifying sources of extant antecedent control (including nonverbal stimuli; Devine et al., 2016) over the less informative, but traditional, assessment focus on response adequacy (i.e., correct/incorrect).

Table 3.

Palmer-Esch model of intraverbal assessment for aphasia

| Probe topic | Purpose | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Echoic* | To test for echoic control | Is echoic control normal, for individual words, phrases, sentences, including nonsense words? Deficits in this area will likely also be evident in intraverbal control. |

| 2 | Textuals** | To test for textual control | Can they read nonsense words, novel phrases/sentences? |

| 3 | True vocal intraverbal | To test for control of discriminated intraverbal | Initiate a familiar phrase (Twinkle twinkle…; Have a nice…; A penny saved is…). Test several of these. If only one is in error, then there has been damage to that particular pathway. If many samples are in error, there has been global damage, possibly affecting all vocal antecedent stimulus control. |

| 4 | Prosody | To test for control by prosodic features of auditory stimulus | Say the first part of a rhythmic intraverbal. Example: HUMPty DUMPty sat on a WALL… Can they continue cadence and form as modeled? Prosody plays many subtle roles in verbal behavior and insensitivity to it will cause some stimulus control to be lost. |

| 5 | Musical component | To test for control by musical component of a multiply controlled response | Hum a few bars of a familiar tune (e.g., happy birthday) and ask the person to hum along. Can they continue and finish the song after you stop humming? This would be a precise analog of a “true” intraverbal, but it is not contaminated by what the corresponding words mean. If they can’t do it, then there has been a loss of stimulus control by at least one dimension of a compound auditory antecedent. |

| 6 | Verbal component | To test for control by verbal component of a multiply controlled response | Using ordinary prosody, but without music, say the words to a familiar song (e.g., happy birthday). Can they continue speaking the song? If not, it shows loss of control by at least one dimension of a compound auditory antecedent. (Ordinarily, continuing the song is under multiple control of verbal and musical antecedents.) |

| 7 | Strategic mediated | To test for history of strategic problem solving | Ask (e.g.) What did you have for dinner last night or What day comes before Tuesday. The actual answer is not important, as long as it reflects some intervening thought (i.e., appropriate latency, some observable mediating responses). |

| 8 | Visually mediated | To test for history of visual mediation | Ask (e.g.) How many windows are there in your house. Accept any answer with a suitable latency, suggesting that the person has engaged in some sort of visualization to mediate the answer. |

| 9 | Own listener | To test for individual serving as own listener | Look for responses that involve self-editing. E.g., ask them to finish a phrase such as Tell me yes or … and they respond “Tess…Yes…Yes or No!” This self-correction indicates that their own auditory stimuli have salience and can be recruited. |

*The echoic can be thought of as a kind of elementary intraverbal

**If both echoics and textuals are intact, then those atomic repertoires are functioning, which means that the relevant forms of verbal response can be easily evoked when trying to remediate any intraverbal deficits that are found. But if both of these repertoires are defective, then intraverbal deficits might not be amenable to remediation

In the model proposed in Table 3, we suggest beginning with probes that test for echoic and textual control. These operants are atomic repertoires that require point-to-point correspondence and, as such, are less likely to have been disrupted after neurologic damage (Palmer, 2012; Skinner, 1957). If intact, these repertoires can be leveraged when remediating intraverbal deficits. Next, the model presents seven additional categories that test other sources of possible stimulus control that can be brought to bear on rehabilitation of the intraverbal repertoire: (a) True vocal intraverbal, which tests for control of a discriminated intraverbal; (b) Prosody, which tests for control by prosodic features of an auditory stimulus; (c) Musical component, which tests for control by musical component of a multiply controlled response; (d) Verbal component, which tests for control by verbal components of a multiply controlled response; (e) Strategic mediated, which tests for history of strategic problem solving; (f) Visually mediated, which tests for history of visual mediation; and (g) Own listener, which tests for an individual serving as their own listener.

Each test area within the model contains comments to inform testing; these comments also suggest research possibilities to define the necessary and sufficient stimulus-response relations to address intraverbal deficits. For example, the Strategic mediation task requires some indication of mediating behavior, such as appropriate latency to respond or perhaps some observable verbal response (e.g., What did you have for breakfast yesterday? “Let me think…yesterday I had to go to the doctor early, so we ate breakfast afterward, at a restaurant, so I must have had Annie’s Pancake Special”). Researchers could investigate how these mediated responses might differ as a function of varying the question formats on a continuum of complexity (e.g., What’s 2 plus 13 versus Can you count by 3’s, starting with 27) or specificity (e.g., Where did you go afterward? versus And then?). It is important that the design of these assessment categories vis-à-vis their test items reflect consonance with an individual’s cultural and experiential background, to the extent possible. Without this consideration, false conclusions may be drawn about the relative strength or weakness of the person’s verbal repertoire. Additionally, all items on the assessment should include a plan for repeating or adjusting the antecedent verbal stimuli following idiosyncratic (i.e., “error”) responses to identify whether correct responses can be evoked by repetition or variation.

Our assessment model’s initial paradigm may be sufficiently comprehensive, although the need for other inclusions (e.g., tact and motivative control) may become apparent with use and analysis. Logistically, one need is an assessment scoring format delineating stimulus control variables that are (a) required, (b) absent, and/or (c) apparently functional (i.e., “errors”) within certain probe categories. Such a format would be an improvement over current binary (correct or incorrect) scoring systems and would support more streamlined error analyses. Future research should consider evaluating the proposed assessment model and identify other operants and modifications that could be useful in the assessment and treatment of verbal repertoires of individuals with aphasia due to ABI. We offer several suggestions for future research.

Investigate Operants not Typically Considered “Verbal”

One research area to consider in assessment would be to probe categories not typically considered “verbal,” for example match-to-sample performance. A series of experiments with college students by Clough et al. (2016) might inform this theme of research. Clough et al. assessed the interplay between verbal mediation and nonverbal task performance, specifically the role of vocal blocking and joint control (i.e., echoic, tact) on visual sequencing performances. Results suggested that vocal blocking may interfere with covert verbal behavior needed to perform a sequencing task. One question, of course, is whether similar results would be found with an ABI population; that is, how match to sample (MTS) performances of persons with damaged intraverbal (or tact or echoic) repertoires vary as a function of vocal blocking. This information would be useful when considering nonverbal stimuli as components of verbal remediation tasks (e.g., tact prompts for intraverbal frames; stimulus selection grids as compound stimuli).

Another question is the degree to which vocal–verbal strategies themselves may interfere with verbal behavior. It is possible that, with some ABI individuals, vocal blocking occurs inadvertently in an attempt to “say it right.” For example, one participant in our assessment produced a string of seemingly off-topic syllables in response to What do you do with a straw? (“A straw, hey, or anyway”). Of course, it’s not difficult to posit putative control for such verbal behavior; the antecedent “straw” could have evoked the echoic “a straw,” which exerted intraverbal control over “hey/hay,” which, in turn, achieved partial echoic control over the rhyming response “anyway.” Regardless of their provenance, the products of responses, in the form of auditory stimuli, may have blocked, to a degree, the salience of the original auditory stimulus (What do you do with a straw). If this is the case, it underscores the need for procedural change (e.g., immediate echoic/self-echoic prompts) to support strategic mediation and to avoid blocking relevant verbal stimuli from achieving evocative control, particularly with longer utterances. Related experiments could vary the length (number of syllables) and complexity (e.g., syntax, grammar, autoclitics) of verbal stimuli to determine how “wandering, off-topic” responses are affected.

Identify Prerequisites and Re-acquisition Sequences of Verbal Behavior

Another area to address with future research is the re-acquisition sequence needed to establish prerequisite skills for functional intraverbal behavior. The work of Alonso-Àlvarez and Pérez-González (2006) with children suggests other research applicable to adults with impaired language resulting from ABI. First is the need to identify prerequisite skills for functional intraverbal behavior. The authors write: “in order for children with autism to answer questions with two relevant stimuli…the present study suggests that they should learn first to answer questions with only one relevant stimulus … It also suggests they should learn the relational [autoclitic] frame corresponding to two-stimuli questions” (p. 99). Adults with ABI may or may not need this same (re-)acquisition sequence, depending upon which repertoires have been disrupted and to what degree. Future work in this area could determine the need to strengthen repertoires that can support or augment disrupted ones (e.g., tacts for intraverbal frames; listener skills), particularly those dependent upon complex multiple control. To the extent that these repertoires are still intact (e.g., listener discriminations, tact skills), they may help reestablish weakened types of verbal stimulus control (e.g., verbal conditional discriminations, verbal function-altering effects; see Axe, 2008; Michael et al., 2011; Schlinger, 1993, Sundberg, 2016).

Develop Research on Function-altering Effects as Contrasted with Evocative Effects

A third area for additional research is the topic of evocative and function-altering effects on verbal behavior. When language skills are lost, as with aphasia, disruptions with evocative stimuli may be readily apparent (e.g., a picture of a fork, or the absence of one in a table setting, may not evoke “fork”). It is less obvious how verbal function-altering effects may be impacted. Function-altering effects involve contingency-specifying stimuli (Schlinger, 1993; Schlinger & Blakely, 1987). When contingencies are specified, but are not immediately active (e.g., When the bell rings, you can leave the room), certain stimuli (e.g., motivating, discriminative, conditional) are altered in such a way that they function to evoke behavior at some point when the contingency is met. In the example above, when the bell rings, the auditory stimulus produced by the bell has an altered function (to evoke leaving the room); thus, the statement (When the bell rings…) has function-altering effects. The foregoing example illustrates function-altering effects of verbal stimuli on nonverbal behavior, but these effects also are ubiquitous with verbal stimuli upon verbal behavior (e.g., When you’re finished eating, ask to be excused; Let me know when you’re ready to go). Multiple questions could provide fodder for future work. For example, what are the necessary conditions for function-altering stimuli to have their effect and how are disrupted repertoires affected if these conditions are altered (see Schlinger, 1993, p. 20)? What learning history is needed to follow verbal “rules” (e.g., tact, listener, match-to-sample)? When one or more of these repertoires has been weakened through ABI, can alternate repertoires assist, and how does stimulus complexity affect performances under these conditions? Researchers might vary stimulus length and conditionality (e.g., When I say go, write your name versus When I turn over the paper, read every third word, but only if it starts with “t”), but there are also clinical applications (e.g., When the nurse comes, what questions did you want to ask; When your daughter arrives, tell her what you need from the pharmacy). There is some evidence that the age of a child (as a “new” language learner) is related to the ability of verbal stimuli to produce function-altering effects; reliable effects are seen with children aged 4 and 5 years but only when simple verbal stimuli are involved; complex verbal stimuli may not reliably alter stimulus functions until age 11 (Braam & Malott, 1990; Mistr & Glenn, 1992; also see Schlinger, 1993). Further research could determine if similar disparities (in the relative effects of stimulus complexity) are seen in adults who, having already acquired functional verbal repertoires, are now experiencing language loss through neurologic disruption.

Final Considerations

The task of incorporating stimulus control variables into assessments and treatments suggests other issues to consider and may lead to modifications of our proposed model: (a) grammar and other structural properties of verbal behavior still require a lucid behavioral account (see Palmer, 2016); (b) intraverbal research must be translated into treatment protocols whereby clinicians are guided in vivo through problem solving those particular stimulus variables requiring focus, fading, transfer, or deletion; and (c) the importance of minimal (atomic) repertoires, such as echoic and self-echoic units (but also other verbal behavior; see Miguel et al., 2005) to effect rapid behavior change should be articulated in the context of repairing faulty intraverbal stimulus control (see Palmer, 2005, 2009, 2012; also, Michael et al., 2011; Skinner, 1957). Explicating the role of atomic repertoires would be of particular value as one of perhaps many self-mediating tools (e.g., Kisamore et al., 2011; also see Eikeseth & Smith, 2013) for communicative problem-solving (e.g., What did I/he/she say – can you repeat it?).

We know that not all inadequate verbal repertoires are the result of brain damage. However, in language assessment and treatment, we would do well to consider that rehabilitation may require a different approach than habilitation. We assume that adults with a history of verbal competence have, or had at one time, multiple skill sets at strength. Despite our clients’ disrupted neural connections resulting from ABI, we should strive to capitalize on strengths that remain and to allow for the possibility that what may appear to be an error in one verbal interaction has the potential to be a mediating response in another verbal interaction. Skinner’s (1957) functional analysis of verbal behavior can provide a conceptual foundation for this effort, resulting in more efficient and effective assessment and intervention programs for those whose once-sophisticated language repertoires have been disrupted. This perspective offers new hope for those with aphasia.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank David Palmer, Mark Sundberg, and John Esch for their comments and contributions to this manuscript.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Human and Animal rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Footnotes

Note that the latter (“rain”) would have been designated as a Partial error instead of Echoic on our assessment and may be a better type of error of sorts, as that response is under at least some intraverbal control and, as such, may have a greater likelihood of evoking non-echoic responses.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aguirre AA, Valentino AL, LeBlanc LA. Empirical investigations of the intraverbal: 2005-2015. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2016;32(2):139–153. doi: 10.1007/s40616-016-0064-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Àlvarez B, Pérez-González LA. Emergence of complex conditional discriminations by joint control of compound samples. The Psychological Record. 2006;56:447–463. doi: 10.1007/BF03395560. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Speech Language Hearing Association. (n.d.). Aphasia (Practice Portal). Retrieved February 19, 2022, from www.asha.org/Practice-Portal/Clinical-Topics/Aphasia/

- American Speech Language Hearing Association Classification of Aphasia Chart. (n.d.). https://www.asha.org/siteassets/practice-portal/aphasia/common-classifications-of-aphasia.pdf Aphasia Classification Chart; American Speech Language Hearing Association. https://www.asha.org/siteassets/practice-portal/aphasia/common-classifications-of-aphasia.pdf. Downloaded January 15, 2022

- Axe JB. Conditional discriminations in the intraverbal relation: A review and recommendations for future research. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2008;24:159–174. doi: 10.1007/BF03393064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JC, LeBlanc LA, Raetz PB. A behavioral conceptualization of aphasia. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2008;24(2):147–158. doi: 10.1007/BF03393063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, A. M., & Baltazar, M. (2021). Behavior analysis and aphasia: A current appraisal and suggestions for the future. Behavioral Interventions, 1–14. 10.1002/bin.1848

- Binder C. Behavioral fluency: Evolution of a new paradigm. The Behavior Analyst. 1996;19(2):163–197. doi: 10.1007/BF03393163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braam C, Malott RW. “I’ll do it when the snow melts”: The effects of deadlines and delayed outcomes on rule-governed behavior in preschool children. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1990;8:67–76. doi: 10.1007/BF03392848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broussard TG. Stroke diary: A primer for aphasia therapy. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan JA, Houlihan D, Linnerooth PJN. Implications of Skinner's verbal behavior for studying dementia. The Journal of Speech and Language Pathology – Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;5(1):48–58. doi: 10.1037/h0100265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cihon TM. A review of training intraverbal repertoires: Can precision teaching help? The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2007;23:123–133. doi: 10.1007/BF03393052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough CW, Meyer CS, Miguel CF. The effects of blocking and joint control training on sequencing visual stimuli. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2016;32:242–264. doi: 10.1007/s40616-016-0067-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JO, Heron TE, Heward WL. Applied behavior analysis. 3. Pearson; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine B, Carp CL, Hiett KA, Petursdottir AI. Emergence of intraverbal responding following tact instruction with compound stimuli. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2016;32:154–170. doi: 10.1007/s40616-016-0062-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon M, Baker JC, Sadowski KA. Applying Skinner’s analysis of verbal behavior to persons with dementia. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahoe, J. W., & Palmer, D. C. (1994). Learning and complex behavior. Boston: Allyn & Bacon (Reprinted, 2004; Richmond: Ledgetop Publishers).