Abstract

Background

In 2018, South Africa opened public consultations on its newly proposed tobacco control bill, resulting in substantial public debate in which a range of arguments, either in favour of or against the Bill, was advanced. These were accompanied by the recurring discussions about the annual adjustments in tobacco taxation. This study uses the concept of framing to examine the public debate in South African print media on the potential effects of the legislation, as well as tobacco tax regulations, between their proponents and detractors.

Methods

A systematic search of news articles using multiple data sources identified 132 media articles published between January 2018 and September 2019 that met the inclusion criteria.

Results

Seven overarching frames were identified as characterising the media debate, with the three dominant frames being Economic, Harm reduction and vaping, and Health. The leading Economic frame consisted primarily of arguments unsupportive of tobacco control legislation. Economic arguments were promoted by tobacco industry spokespeople, trade unions, organisations of retailers, media celebrities and think tanks—several of which have been identified as front groups or third-party lobbyists for the tobacco industry.

Conclusion

The dominance of economic arguments opposing tobacco control legislation risks undermining tobacco control progress. Local and global tobacco control advocates should seek to build relationships with media, as well as collate and disseminate effective counterarguments to those advanced by the industry.

Keywords: media, tobacco industry, public policy, advocacy, low/middle-income country

Introduction

The media often play a crucial role in policymaking. They can influence agenda setting (whereby some concerns rise to the attention of policymakers), draw the public’s attention to certain issues and help convey public attitudes to decision-makers.1 2 Media frequently inform the discourse around a policy debate by framing an issue in a particular way, which can condition perceptions of the appropriate policy solution(s) to that issue, and hence the policies regulators progress.3 Media can also potentially highlight the actors involved in the policy process and can aid or hinder their cause by drawing attention to their activities.2

Analyses of framings employed in public health debates are essential to strengthen public health advocacy efforts, particularly in tobacco control policymaking, which involves an increasingly complex array of competing stakeholders (eg, local and transnational tobacco manufacturers, business associations, electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) manufacturers, e-cigarette advocacy groups, retailers, tobacco growers, and health and welfare organisations).

Although some research has examined how arguments supporting or opposing tobacco control policies have been framed, these studies have mainly been conducted in high-income countries with progressive tobacco control policies.4–7 In Africa, where demand for cigarettes is projected to keep increasing,8 9 and where implementation of tobacco control measures is relatively limited,10 few studies have explored how tobacco control has been represented in the news media.11 12

In May 2018, public consultations were opened on South Africa’s (SA) proposed Control of Tobacco Products and Electronic Delivery Systems Bill (hereafter ‘the Bill’).13 The proposed legislation would remove designated smoking areas in restaurants and other public places, introduce standardised packaging with graphic health warnings, remove cigarette vending machines, ban point-of-sale tobacco marketing (making it illegal to display tobacco products at the point of sale in retail venues), and regulate e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products as tobacco products.14

As previous research in SA has demonstrated that English-language newspapers are influential with the public and policymakers in agenda setting,15 16 we examined the public debate around the Bill that ensued in SA print media, exploring how competing stakeholders framed their position and sought to dominate the debate.

Methods

We used the LexisNexis news archive to conduct a systematic search of news articles published in SA newspapers between 1 January 2018 and 16 September 2019, using terms ‘South Africa’ and ‘tobacco’. LexisNexis contains more than 4 billion searchable documents from tens of thousands of sources, and allows users to retrieve articles specific to a country of interest. We supplemented this search with a Google Alert for the same keywords from 2 April 2019 (when this research project was started) to 16 September 2019, and through the ‘find similar’ function of PressReader. SA has a vast multilingual media landscape, however only English-language newspapers were included in the searches due to their wide and varied readership and influence with policymakers,15–17 as well as the pragmatic advantage of not requiring resources for translation.

We identified and scanned 2082 (LexisNexis) and 44 (Google Alert) articles. We included articles (n=132) that referred to the Bill specifically in the title or body of article, and to tobacco tax regulations discussed alongside the Bill; we excluded articles that only referred to illicit tobacco or track-and-trace systems without mentioning the Bill. The Bill did not include a price component, but since tobacco taxes are adjusted annually by the SA National Treasury (under the Ministry of Finance), the public discussion on cigarette taxation closely accompanied the debate on the Bill and was included in the analysis.

For each article, we extracted the publication date, author, newspaper name, individuals and organisations mentioned, and any mentions of events relating to tobacco control and tobacco regulation (including policy reviews, tobacco control conferences, releases of studies and surveys evaluating the regulation, anti-regulation campaigns). The Tobacco Tactics website (a resource containing profiles of the tobacco industry’s key personnel, organisation and allies), which is curated by an academic institution and is rigorously sourced applying academic standards of evidence, was consulted for any links the identified organisations and individuals might have with the tobacco industry.18

Articles were first read by MZZ for data familiarisation and an initial coding framework capturing arguments organised under five conceptual, overarching frames (economic, health, moralistic, historical, political/legislative) was drafted based on previous research on the framing of policy debates over the regulation of unhealthy commodities, including tobacco and alcohol.19 20 Descriptive accounts of the identified arguments were developed and the most frequently recurring specific arguments were grouped under the relevant frames (for full list of arguments, see online supplemental table 2). MZZ and LR tested the initial codebook with a random sample of n=10 articles and as a result, two additional frames were identified inductively (international and harm reduction). The double-coding also served as a training exercise before MZZ reviewed the coding categories and processes. Following the double-coding, MZZ consulted the complete list of codes with COE, who served to refine and finalise the wording of the categories and contextualise them for the South African context. MZZ then coded the remaining articles using NVivo. Throughout the process, the authors periodically reviewed and discussed the coded data for consistency.

tobaccocontrol-2021-056675supp001.pdf (147.3KB, pdf)

Articles were assessed for whether they were broadly supportive (contained more positive than negative statements), unsupportive (vice versa) or neutral (they did not contain any value judgement) towards tobacco control. Descriptive analyses were used to present the frequency of media articles across the covered period, by frame and by support for tobacco control regulation.

Results

The included 132 articles were published in seven calendar quarters (Q1–Q7) between January 2018 and September 2019, in 31 news media outlets. They reported on key events surrounding tobacco control in SA, including milestones in the progress of the Bill, changes in tobacco taxation, and campaigns and events organised by supporters and opponents of tobacco control regulation (event timeline is presented in table 1). Descriptions of organisations most frequently mentioned in the articles, their stance towards the Bill and tobacco control regulation, and any known links with the tobacco industry are presented in online supplemental table 1. Organisations supportive of the Bill were primarily research and advocacy civil society groups and parastatal organisations, as well as academic research units. Organisations unsupportive of the Bill were pro-vaping groups, farmers’ and labour organisations,tobacco industry associations and libertarian groups. Among the included organisations critical of the tobacco control measures, 7 out of 10 had previously evidenced links with the tobacco industry.

Table 1.

Timeline of key events in tobacco control in South Africa by calendar quarter

| Calendar quarter | Date | Event | Event description |

| Q1 (January 2018–March 2018) |

21 February 2018 | South African National Treasury Budget Review for 2018 published | The annual budget review conducted by the South African National Treasury includes an increase of the amount of excise tax on tobacco products by 8.5%.62 |

| 7–9 March 2018 | 17th World Conference on Tobacco or Health (WCToH) | The 17th WCToH was held in Cape Town, South Africa and gathered around 2000 delegates from over 100 countries. During the conference, the South African Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi makes a commitment to amend and strengthen the country’s tobacco legislation.63 | |

| Q2 (April 2018–June 2018) |

9 May 2018 | South African tobacco control bill published for public comment | The Control of Tobacco Products and Electronic Delivery Systems Bill is published in the Government Gazette inviting persons to submit comments within 3 months of publication.64 |

| 31 May 2018 | World No Tobacco Day (WNTD) 2018 | Annual event promoted by the WHO raising awareness of the dangers of tobacco use and exposure. Accompanied by global and local tobacco control activities, including policy advocacy.65 | |

| Q3 (July 2018–September 2018) |

2 July 2018 | Japan Tobacco International (JTI) launches #HandsOffMyChoices campaign | #HandsOffMyChoices anti-plain packaging campaign materials begin to appear in print, electronic, broadcast and social media. The campaign criticised various provisions of the Bill, including plain packaging and the ban on point-of-sale marketing.66 The campaign ads largely concealed its tobacco industry funding.24 |

| 5 July 2018 | IPSOS releases study on illicit tobacco trade | Market research firm IPSOS releases report suggesting massive scale of illicit tobacco trade in South Africa and its cost for the country.25 The report is commissioned by the TISA and immediately followed by the launch of TISA’s #TakeBackTheTax campaign.24 | |

| 13 July 2018 | Tobacco Institute of Southern Africa’s (TISA) #TakeBackTheTax campaign goes live | Tobacco industry body TISA launches the #TakeBackTheTax campaign suggesting that tackling South Africa’s illicit cigarette trade should precede any further tobacco control regulations.24 Campaign is fronted by anti-crime activist Yusuf Abramjee.67 TISA pays social influencers to promote the campaign and publishes ads in leading newspapers.66 | |

| 8 August 2018 | Period of public comment for the Bill closes | The 3-month period of public comment on the Bill closes.68 | |

| 12 August 2018 | The Food and Allied Workers Union (FAWU) launches #NotJustAJob campaign | Trade union FAWU launches social media campaign profiling tobacco workers at risk of losing their jobs.69 Campaign is accompanied by statements from FAWU leadership criticising the Bill,70 and a march against illicit trade on 14 August 2018.71 | |

| Q4 (October 2018–December 2018) |

– | – | – |

| Q5 (January 2019–March 2019) |

22 January 2019 | Econometrix warns treasury against increasing excise tax | Consultancy firm Econometrix publishes study commissioned by British American Tobacco South Africa suggesting that increasing the tobacco excise tax would lead to a spike in illicit cigarette trade and cost the country billions in lost revenue.72 |

| 20 February 2019 | South African National Treasury Budget Review for 2019 published | The annual budget review conducted by the South African National Treasury includes an increase of the level of excise tax on tobacco products by 7.4% on cigarette tobacco and 9% on pipe tobacco.73 | |

| Q6 (April 2019–June 2019) |

31 May 2019 | WNTD 2019 | See WNTD 2018 above for details. |

| Q7 (July 2019–September 2019) |

24 July 2019 | JTI publishes survey on plain packaging | JTI-commissioned survey carried out by Victory Research claims that there is low support for plain packaging among the South African public, but its methodology is heavily criticised by researchers at the University of Cape Town.74 Survey results are advertised in leading South African newspapers.75 |

Analysis of dominant frames

Seven overarching frames, each composed of several distinct arguments, were identified as characterising the public debate on tobacco control. The three dominant frames were Economic, Harm reduction and vaping, and Health. A summary of the most frequent arguments (mentioned in at least 10% of the articles analysed) is presented in table 2 (the full list of arguments and their frequency is available in online supplemental table 2). Media articles referenced in the text are numbered S1–S32, and their full details are available in the online supplemental file.

Table 2.

Summary and frequency of arguments, by frame

| Argument name | Argument frequency* |

| Economic frame | |

| Unsupportive | |

| Regulation will increase illicit trade | 27 |

| Regulation will lead to job losses | 23 |

| Regulation will harm small businesses | 14 |

| Regulation will harm SA economy | 13 |

| Supportive | |

| Burden of smoking on SA economy and healthcare | 22 |

| Regulation will not substantially impact illicit trade | 10 |

| Harm reduction and vaping frame | |

| Unsupportive | |

| Regulation will take away safer alternative | 23 |

| Vaping is not smoking | 14 |

| Supportive | |

| Vaping is harmful | 27 |

| Vaping as a gateway or leading to dual use | 17 |

| Health frame | |

| Supportive | |

| Smoking is a key driver of morbidity and mortality | 61 |

| Health consequences of secondhand smoke | 28 |

| Smoking-related harm among women, young people, vulnerable populations | 25 |

| Moralistic frame | |

| Unsupportive | |

| Regulation is an attack on freedom of choice | 16 |

| Supportive | |

| Unethical nature of tobacco industry | 34 |

| Tobacco industry undermining tobacco control regulation | 32 |

| Tobacco industry targeting children | 17 |

| Historical frame | |

| Supportive | |

| Success of previous tobacco control legislation in SA | 24 |

| Tobacco control progress has stalled/reversed in South Africa | 22 |

| Tobacco industry is targeting Africa | 19 |

| International frame | |

| Supportive | |

| Examples of regulation in other countries | 29 |

| SA must fulfil WHO FCTC obligations | 21 |

| Regulation supported by international organisations | 20 |

| Political/legislative frame | |

| Unsupportive | |

| Regulation will not be effective | 16 |

| Enforcement of existing regulation should be the priority | 15 |

Supportive=arguments supportive of tobacco control regulation. Unsupportive=arguments unsupportive of tobacco control regulation.

*In how many individual articles was the specific argument mentioned.

FCTC, Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; SA, South Africa.

Economic frame

The most common argument was that further tobacco control legislation would contribute to increasing illicit trade in SA. This argument was deployed not only to criticise the Bill, but also the annual increases in cigarette taxation. On the eve of a tax increase in February 2019, the Black Tobacco Farmers Association (BTFA) issued a statement criticising the decision: ‘It is hugely disappointing that Treasury has offered no help at all but instead decided to make things easier for tax dodgers by increasing tax again on the legal industry’ (S1). This argument was also used to criticise other provisions of the Bill, such as plain packaging.

AgriSA, the Food and Allied Workers Union (FAWU) and the SA Spaza and Tuckshop Association (SASTA) said on Tuesday that the bill would “devastate SA’s agriculture and township businesses”. The plain packaging provisions would boost the illicit cigarette trade […]. (S2)

In July 2019, Japan Tobacco International (JTI) released the results of a survey it commissioned claiming that the SA public ‘expressed a high level of concern about plain packaging resulting in negative consequences, such [as] the spike in illegal cigarette sales’ (S3). To coincide with the release of the survey, The Star daily newspaper was published with a blank cover and a four-page spread wrap sponsored by JTI criticising plain packaging (S4).

Another prominent argument, job losses, was often mentioned alongside claims that regulation would harm small businesses and SA farmers. Retailers were reported saying that new laws will lead them to ‘retrench employees’ (S5). The Vaping Products Association of South Africa warned that e-cigarette regulations would stall job creation in the expanding vaping sector (S6). The Tobacco Institute of Southern Africa (TISA) threatened that the new laws would pose a risk to the over 100 000 jobs which the tobacco sector ‘directly and indirectly supported […] of which 8000–10 000 jobs are on farms in deep rural areas […]’ (S7).

The tobacco control community attempted to challenge the anti-regulation messages dominating the Economic frame. One argument supportive of legislation was that smoking is a burden for SA’s economy and healthcare through tobacco-related hospitalisations, productivity loss, premature mortality and the financial impact on SA families. Newspapers quoted the WHO and SA public health researchers that ‘tobacco imposes a heavy economic burden on South Africa, estimated at over R59 billion a year’ (S8). The media also reported research debunking the industry’s claim that regulation leads to illicit trade (S9).

Harm reduction and vaping frame

The most common unsupportive argument in this frame, often brought up by tobacco industry spokespeople and pro-vaping groups, was that regulation of e-cigarettes and novel tobacco products would take away a safer alternative from smokers who cannot quit. The Philip Morris SA Chief Executive urged the government to exempt IQOS (SA was the first African country in which this product was introduced on the market, in 2016),21 from the Bill, explaining that it generates, ‘on average, less than 10% of the levels of harmful constituents found in ordinary cigarettes smoke’ (S10). These claims were echoed by the e-cigarette industry and pro-vaping organisations. Delon Human, a medical doctor with a history of collaborating with British American Tobacco South Africa,22 and co-founder of the Africa Harm Reduction Alliance, argued that ‘Vaping and e-cigarettes have the potential to prevent tobacco-related disease and save hundreds of millions of lives from premature death’ (S11). Another prominent argument was that vaping is not smoking and should not be measured with the same regulatory yardstick (S11).

Several of the arguments within the Harm reduction and vaping frame were supportive of the regulation. The most common of these was that vaping is harmful. Media quoted researchers and the WHO that ‘emissions from heated tobacco products and e-cigarettes contained toxins, metals, nicotine and other harmful and potentially harmful substances’ (S12). Similar sources were cited in relation to the argument that vaping is a gateway for new smokers or leads to dual use. This included a study in the New England Journal of Medicine showing that the majority of e-cigarette users continue to smoke cigarettes (S13).

Health frame

The Health frame comprised arguments supportive of tobacco control, most commonly that smoking is a key driver of premature mortality and morbidity, with tobacco ‘one of the biggest public health threats the world has ever faced’ (S14). This was accompanied by Tobacco Atlas estimates that ‘more than 42 100 South Africans die from tobacco-related diseases each year’ (S15). Tobacco control legislation would help in ‘decreasing the number of people affected by tobacco-related diseases such as lung cancer’ (S16). This argument was also sometimes used to refute the tobacco industry’s economic arguments. Spokespeople of the Department of Health argued that ‘there is no economic development if people are sick or dead’ (S17). The SA Minister of Health put this point more bluntly: ‘are we creating these jobs for corpses?’ (S18).

Another argument focused on the health consequences of secondhand smoke. Media reported that the Bill would ‘decrease the effects of second-hand smoke on the majority of South Africans, who are non-smokers’ (S19). The final argument focused on smoking harm among vulnerable populations. This often took a more emotive tone, with headlines such as ‘Shocking nicotine levels in babies’ (S20). SA officials highlighted the importance of ‘evidence-based tobacco control interventions’ in reaching ‘the ultimate goal of zero initiation for young people’ (S21). Growing smoking rates among women were also singled out as a burning problem (S22) and WHO Africa figures cited that ‘two out of three deaths from second-hand smoke in Africans occur among women’ (S23).

Minor frames

The remaining frames were less prominent, and most were dominated by arguments supportive of the legislation, except for the Political/legislative frame, where unsupportive arguments were more frequent.

Under the Moralistic frame, media referred to the unethical nature of the tobacco industry, and argued that due to its long track record of ‘tax evasion, money laundering, racketeering and corruption’ and opportunistically targeting ‘young people in Africa’ (S24), the tobacco industry should not be allowed to engage in formulating public health policy. A related argument referred to the tobacco industry’s attempts to undermine tobacco control regulation. The SA Minister of Health said that ‘all the signs are there that the tobacco industry is staging a fightback after a slew of tobacco control legislation in the past two decades’ (S25). Journalists also suggested that TISA’s ‘comments should be taken with a grain of salt’ given that the ‘body has a history of pushing policymakers away from any regulations that would affect the tobacco industry’s bottom line’ (S26). The arguments critical of tobacco control regulation within this frame portrayed the Bill as an attack on the freedom of choice.

Under the Historical frame, the media cited the public health success of previous tobacco control legislation in bringing down smoking rates in SA (S27). Media also criticised the tobacco industry’s targeting of Africa, with the WHO Director General quoted in warning ‘that Africa was ‘ground zero’ for tobacco companies, who had identified it as a major growth market’ (S28).

The International frame’s most frequent supportive argument focused on examples of tobacco control regulation in other countries, for example, pointing out that ‘Gabon, the Gambia, Kenya, Senegal and Uganda are Africa’s shining lights in terms of tobacco control interventions’ (S29). The regulations proposed in the Bill were described as reflecting such best practice (S26). The Bill was presented as a step towards SA fulfilling its obligations to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (S30).

Finally, the Political/legislative frame was dominated by arguments critical of the Bill, such as the tobacco industry’s claims that proposed tobacco control regulation will not be effective in reducing smoking rates. Smokers were quoted speaking unfavourably about the feasibility of the proposed rules—‘What are they going to do? Arrest all of the smokers?’ (S31). This was often accompanied by the argument that the enforcement of existing regulation should be the priority. In July 2019, JTI sponsored stories promoting the results of its survey showing that rather than focusing on plain packaging, ‘87% of South Africans think it is important to prioritise more effectively enforcing existing rules prohibiting the sale of alcohol and cigarettes to minors’ (S32).

Stance, volume and timing of arguments

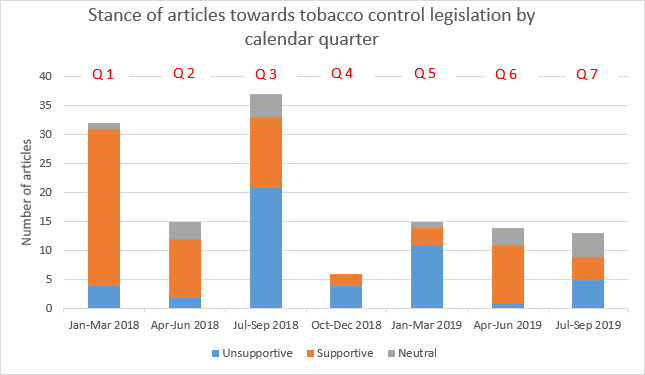

Public health advocates made a concerted effort to support the Bill in SA print media. The two organisations mentioned most frequently belonged to the tobacco control community—the National Council Against Smoking (NCAS) was mentioned in 28 articles, and the University of Cape Town (UCT) in 27. Tobacco industry body TISA came third with mentions in 23 articles (see online supplemental figure 1 for number of mentions of different organisations by quarter). In effect, a narrow majority (52%) of all media articles in the period between 1 January 2018 and 16 September 2019 identified in this study took a predominantly supportive stance towards tobacco control regulation. However, almost 40% of these supportive articles were published in Q1, coinciding with a major public health event which drew media attention—the World Conference on Tobacco or Health, held in Cape Town in March 2018. For most of the remaining quarters, media reporting was dominated by articles unsupportive of tobacco control regulation (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Stance of articles towards tobacco control legislation by calendar quarter

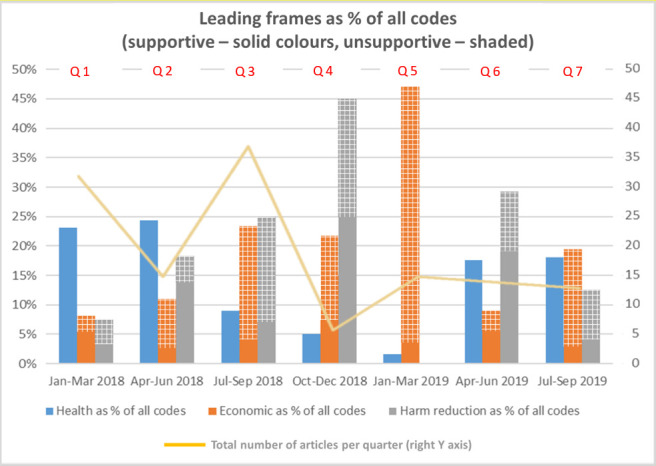

The quarters in which unsupportive media coverage prevailed were those in which arguments from the Economic frame outnumbered arguments from the Health frame. This was the case in Q3, which saw the peak in media reporting on tobacco control regulation, when almost one-third (n=37) of all articles included in this study were published (see figure 2). This quarter included an important policy window, namely the period of public comment for the Bill, closing on 8 August 2018. The tobacco industry intensified its activity to ensure its messages dominated the media debate in this period. In July 2018, JTI launched its anti-plain packaging #HandsOffMyChoices campaign, accompanied by print media advertisement and substantial coverage.23 24 At the same time, IPSOS released the TISA-commissioned study showing that illicit trade in cigarettes in SA has skyrocketed since 2014.25 A week later, TISA launched its #TakeBackTheTax campaign, which argued that a further tightening of tobacco control regulations will be counterproductive until SA curbed its illicit cigarette trade. The campaign was well publicised in leading newspapers such as Mail & Guardian and fronted by journalist and anti-crime activist Yusuf Abramjee.26 27 In Q3, TISA became the organisation most frequently mentioned by the media, overtaking UCT and NCAS, and articles critical of tobacco control regulation significantly outnumbered those in favour.

Figure 2.

Leading frames as percentage of all codes

Third parties sympathetic to the tobacco industry also appeared to mobilise ahead of specific policy windows. For example, all mentions of the SA Spaza & Tuckshop Association and of the SA Informal Traders Alliance were between 6 and 12 August 2018 (Q3), coinciding with the closing on public comments for the Bill on 8 August 2018. Both organisations were highly critical of the impact the Bill would have on their members. Another organisation, the BTFA, was set up in January 2019,28 with support from British American Tobacco South Africa.29 All its mentions in the media came in January and February 2019, coinciding with the SA Treasury Budget review in late February 2019, and related to the BTFA’s opposition to the planned increase in excise tax in cigarettes.

Discussion

The tobacco control legislation proposed in the Bill remains unenacted at the time of writing in September 2021, an outcome that could be, at least in part, due to the industry’s use of economic arguments to oppose the Bill in influential newspapers, arguments that appear to hold more sway than health-focused arguments.4 19 30–35

Our findings suggest that despite engagement of the SA public health community in the media, actors supportive of, or financially linked to the tobacco industry, have been able to successfully promote and dominate the Economic frame in the debate around tobacco control legislation between 1 January 2018 and 16 September 2019. Economic arguments critical of the Bill were promoted by tobacco industry spokespeople, trade unions, organisations of retailers, media celebrities and think tanks—most of which have been identified as front groups or third-party lobbyists for the tobacco industry. The analysed period included two budget reviews, in February 2018 and February 2019, and the tobacco industry harnessed these events to further highlight the economic arguments in reference to tobacco tax, but also tobacco control more broadly. The tobacco industry concentrated its efforts around specific policy windows, and launched tailored campaigns focusing on criticising individual provisions of the Bill or tobacco tax increases.

Our findings are consistent with evidence of tobacco industry strategies to garner media attention, including by launching tailored campaigns to coincide with policy windows, using third parties to amplify arguments against tobacco control regulation, and promoting its own data on illicit tobacco trade among journalists.20 36–43

The anti-regulation arguments identified in this study are also consistent with previous work on tobacco industry discursive strategies that has largely drawn on data from outside Africa.43 However, we identified several that have not been described before, or are only starting to begin to emerge in the literature,44 including the tobacco industry claim that it is a champion of SA’s black population, or that the local socioeconomic context impedes the introduction of global best practice tobacco control legislation. This provides a warning for low/middle-income country-based tobacco control advocates that while the industry recycles its discursive strategies from previous policy debates, it does carefully adapt them to the local context.

In addition, this is one of the first studies to categorise harm reduction arguments used by the tobacco industry and its allies.45 The tobacco industry has increasingly used its purported commitment to harm reduction to interfere with tobacco control legislation, including but not limited to regulation of e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products, often employing third party groups to lobby on its behalf.46 The findings from SA are an important heads-up for advocates and policymakers of the kind of tobacco industry messaging they should increasingly expect to see in the future.

Implementation of the Bill would make SA the first African country to adopt plain packaging, a policy that has seen extensive tobacco industry opposition in other jurisdictions.47–50 The SA case study can constitute a useful bellwether in trying to understand upcoming challenges, in particular industry interference, in tobacco control policy progress in sub-Saharan Africa. Specifically, a key implication of our study is that the public health community needs to prepare and pre-empt economic arguments about tobacco control policies, including economic studies that counter industry claims, modelling studies of the effectiveness of tobacco control policies and cost-savings to the health system, and accurate data about the number of people employed by the tobacco industry. A second implication is the need for the global tobacco control community and funders to support local tobacco control advocates to successfully access and use media in countering the tobacco industry’s arguments. This is especially important given evidence that tobacco companies provide journalists with a range of incentives,44 51 which likely affects how those journalists frame tobacco issues. Third, continued media monitoring and engagement by the public health community with journalists and editors could ensure greater transparency in media reporting, and greater awareness and exposure of conflicts of interest when reporting on issues of tobacco control. In particular, exposing the sometimes hypocritical nature of tobacco companies’ arguments could be important in driving tobacco industry denormalisation, which is an effective tobacco control intervention.52–55 One such example is the use of illicit trade as an argument against regulation by the same organisations that have been fuelling illicit trade and undermined measures to control it, in SA and globally.56 57 Another is the use of tax-based arguments, given the tobacco industry’s history of global tax evasion and avoidance.58 The detachment between the tobacco industry’s rhetoric and practice is well evidence in the literature,55 59 60 and should be exposed more forcefully if the tobacco control community hopes to challenge the tobacco industry’s use of economic arguments to oppose tobacco control.

Limitations

The identified dominance of economic arguments might be partly attributable to the fact that the analysis included articles that referred both to the Bill, and to the separate tobacco tax regulation. However, because these developments overlapped, and lobbying and arguments around these issues frequently conflated, separating the two would risk mischaracterising the actual picture of the public debate on tobacco control in SA in the analysed period.

This study only reported on English-language articles openly referencing tobacco control and tobacco tax regulation in SA and did not analyse the reach or prominence of the articles (the readership numbers, the word count of articles, what page they appeared on, how much space they occupied, the readership numbers, the political leanings of the newspapers) nor stakeholders’ responses to them.

Finally, this study only focused on newspaper media and did not include other media, such as social media platforms, or radio, which is a medium that is especially well used in SA.61 However, our approach nonetheless enabled an analysis of the range of arguments put forward during the public debate around tobacco control regulation in SA.

Conclusion

The tobacco industry and its allies were able to shape the media debate on tobacco control legislation in SA in 2018 and 2019. Their success in focusing the discussion on economic considerations risks undermining tobacco control progress in the country. Local and international tobacco control advocates, with support of global funders, should seek to build relationships with media ensuring greater transparency in reporting on tobacco control, and build a relevant scientific base to pre-empt, counter, and expose the hypocritical nature of economic arguments advanced by the industry.

What this paper adds.

Studies conducted in high-income countries have examined how arguments supporting or opposing tobacco control policies have been framed.

Tobacco control policy debates dominated by economic framing risk marginalising public health interests and undermining proposed legislation.

Few publications have this far focused on how tobacco control policies have been represented by the media in sub-Saharan Africa or other low/middle-income countries.

The tobacco industry used the media to promote mostly an economic framing of the proposed tobacco control legislation in South Africa between January 2018 and September 2019.

To amplify its message, the tobacco industry launched campaigns to coincide with policy windows, used third parties to advance its rhetoric and recycled anti-regulation campaigns from other countries.

Footnotes

Twitter: @ZatonskiMateusz

Contributors: All authors have contributed to the conceptualisation and drafting of this paper. MZZ and LR have conducted the data collection and analysis, and carried out the revisions. MZZ acted as a guarantor for the overall content of this article.

Funding: This project, and MZZ’s, LR’s, and AG’s time, were funded by Bloomberg Philantropies Stopping Tobacco Organisations and Products project funding (www.bloomberg.org). COE’s time was funded by the South African Medical Research Council.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Research Ethics Approval Committee for Health, University of Bath (reference number: EP 18/19 082).

References

- 1. Shiffman J. Agenda setting in public health policy. In: Quah SR, ed. International encyclopedia of public health. Elsevier, 2016: 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Soroka S, Lawlor A, Farnsworth S. Mass media and policymaking. In: Araral E, Fritzen S, Howlett M, eds. Routledge handbook of public policy. Routledge, 2012: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Entman RM. Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J Commun 1993;43:51–8. 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rowbotham S, McKinnon M, Marks L, et al. Research on media framing of public policies to prevent chronic disease: a narrative synthesis. Soc Sci Med 2019;237:112428. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. MacKenzie R, Mathers A, Hawkins B, et al. The tobacco industry's challenges to standardised packaging: a comparative analysis of issue framing in public relations campaigns in four countries. Health Policy 2018;122:1001–11. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chau J, Kite J, Ronto R, et al. Talking about a nanny nation: investigating the rhetoric framing public health debates in Australian news media. Public Health Res Pract;29. 10.17061/phrp2931922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miller CL, Brownbill AL, Dono J, et al. Presenting a strong and united front to tobacco industry interference : a content analysis of Australian newspaper coverage of tobacco plain packaging 2008-2014. BMJ Open 2018;8:e023485. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vellios N, Ross H, Perucic A-M. Trends in cigarette demand and supply in Africa. PLoS One 2018;13:e0202467. 10.1371/journal.pone.0202467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Méndez D, Alshanqeety O, Warner KE. The potential impact of smoking control policies on future global smoking trends. Tob Control 2013;22:46–51. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. WHO . The who framework convention on tobacco control: 10 years of implementation in the African region. Africa: WROf, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tam J, van Walbeek C. Tobacco control in Namibia: the importance of government capacity, media coverage and industry interference. Tob Control 2014;23:518–23. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abraham EA, Egbe CO, Ayo-Yusuf OA. News media coverage of shisha in Nigeria from 2014 to 2018. Tob Induc Dis 2019;17:33. 10.18332/tid/106139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tactics T. South Africa - Country Profile, 2020. Available: https://tobaccotactics.org/wiki/south-africa-country-profile/ [Accessed 03 Oct 2020].

- 14. Egbe CO. How South Africa is tightening its tobacco rules, 2018. Available: https://theconversation.com/how-south-africa-is-tightening-its-tobacco-rules-97382 [Accessed 21 Nov 2019].

- 15. Pratt CB, Ha L, Pratt CA. Setting the public health agenda on major diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: African popular magazines and medical journals, 1981–1997. Journal of Communication 2002;52:889–904. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Serino TK. ‘Setting the agenda’: the production of opinion at the Sunday Times. Soc Dyn 2010;36:99–111. 10.1080/02533950903561312 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Unknown. A guide to South African newspapers. Brand South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tactics T. Home Page, 2021. Available: https://tobaccotactics.org/

- 19. Zatoński M, Hawkins B, McKee M. Framing the policy debate over spirits excise tax in Poland. Health Promot Int 2016;26:daw093–524. 10.1093/heapro/daw093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Durrant R, Wakefield M, McLeod K, et al. Tobacco in the news: an analysis of newspaper coverage of tobacco issues in Australia, 2001. Tob Control 2003;12 Suppl 2:75ii–81. 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_2.ii75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Philip Morris International . South Africa: bringing a smoek-free future to the African continent, 2020. Available: https://www.pmi.com/integrated-report-2019/south-africa-bringing-a-smoke-free-future-to-the-african-continent [Accessed 24 Feb 2021].

- 22. Tobacco Tactics . Delon human, 2020. Available: https://tobaccotactics.org/wiki/delon-human/ [Accessed 03 Nov 2020].

- 23. Tobacco Tactics . South Africa: industry interference with the control of tobacco products and electronic delivery systems bill, 2020. Available: https://tobaccotactics.org/wiki/south-africa-industry-interference-with-the-control-of-tobacco-products-and-electronic-delivery-systems-bill/ [Accessed 03 Oct 2020].

- 24. Modjadji M, Cullinan K. Professionals co-opted to back tobacco giants, 2018. Daily Maverick. Available: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2018-08-19-professionals-co-opted-to-back-tobacco-giants/ [Accessed 03 Nov 2019].

- 25. Ipsos . New study finds that trade in illegal cigarettes flourished during 2014 – 2017 SARS crisis, 2018. Available: https://www.ipsos.com/en-za/new-study-finds-trade-illegal-cigarettes-flourished-during-2014-2017-sars-crisis [Accessed 04 Nov 2019].

- 26. van Dyk J. Did big tobacco buy Twitter? Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism 2018. https://bhekisisa.org/article/2018-09-07-00-did-big-tobacco-buy-twitter-industry-fights-new-tobacco-control-bill/ [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tobacco Tactics . Yusuf Abramjee, 2020. Available: https://tobaccotactics.org/wiki/yusuf-abramjee/ [Accessed 24 Feb 2021].

- 28. Noemdoe D. Black tobacco farmers band together to form association, 2019. Food for Mzansi. Available: https://www.foodformzansi.co.za/black-tobacco-farmers-band-together-to-form-association/ [Accessed 13 Jan 2020].

- 29. Black Tobacco Farmers Association . Black tobacco farmers association. black tobacco farmers unite to save 10,000 jobs fromillegal cigarettes, 2019. Available: https://btfa.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/BTFA_Press-Statement.pdf [Accessed 02 Feb 2020].

- 30. Townsend B, Schram A, Baum F, et al. How does policy framing enable or constrain inclusion of social determinants of health and health equity on trade policy agendas? Crit Public Health 2020;30:115–26. 10.1080/09581596.2018.1509059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Casswell S. Vested interests in addiction research and policy. Why do we not see the corporate interests of the alcohol industry as clearly as we see those of the tobacco industry? Addiction 2013;108:680–5. 10.1111/add.12011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Katikireddi SV, Bond L, Hilton S. Changing policy framing as a deliberate strategy for public health advocacy: a qualitative policy case study of minimum unit pricing of alcohol. Milbank Q 2014;92:250–83. 10.1111/1468-0009.12057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hawkins B, Holden C. Framing the alcohol policy debate: industry actors and the regulation of the UK beverage alcohol market. Crit Policy Stud 2013;7:53–71. 10.1080/19460171.2013.766023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gantiva C, Jiménez-Leal W, Urriago-Rayo J. Framing messages to deal with the COVID-19 crisis: the role of Loss/Gain frames and content. Front Psychol 2021;12:568212. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.568212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Townsend B, Friel S, Freeman T, et al. Advancing a health equity agenda across multiple policy domains: a qualitative policy analysis of social, trade and welfare policy. BMJ Open 2020;10:e040180. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Evans-Reeves K, Hatchard J, Rowell A, et al. Illicit tobacco trade is ‘booming’: UK newspaper coverage of data funded by transnational tobacco companies. Tob Control 2020:tobaccocontrol-2018-054902. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Harris JK, Shelton SC, Moreland-Russell S, et al. Tobacco coverage in print media: the use of timing and themes by tobacco control supporters and opposition before a failed tobacco Tax initiative. Tob Control 2010;19:37–43. 10.1136/tc.2009.032516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Magzamen S, Charlesworth A, Glantz SA. Print media coverage of California's smokefree bar law. Tob Control 2001;10:154–60. 10.1136/tc.10.2.154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Champion D, Chapman S. Framing PUB smoking bans: an analysis of Australian print news media coverage, March 1996-March 2003. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;59:679–84. 10.1136/jech.2005.035915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wiist WH. The bottom line or public health: tactics corporations use to influence health and health policy, and what we can do to counter them. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rowell A, Evans-Reeves K, Gilmore AB. Tobacco industry manipulation of data on and press coverage of the illicit tobacco trade in the UK. Tob Control 2014;23:e35–43. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Watts C, Freeman B. "Where There's Smoke, There's Fire": a content analysis of print and web-based news media reporting of the philip morris-funded foundation for a smoke-free world. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2019;5:e14067. 10.2196/14067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ulucanlar S, Fooks GJ, Gilmore AB. The policy Dystopia model: an interpretive analysis of tobacco industry political activity. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002125. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Matthes BK, Lauber K, Zatoński M, et al. Developing more detailed taxonomies of tobacco industry political activity in low-income and middle-income countries: qualitative evidence from eight countries. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e004096. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dewhirst T. Co-optation of harm reduction by big tobacco. Tob Control 2020:tobaccocontrol-2020-056059. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Evans-Reeves K. Addiction at any cost: Philip Morris International uncovered, 2020. Stopping Tobacco Organizations & Products. Available: https://exposetobacco.org/pmi-uncovered/ [Accessed 22 Jun 2020].

- 47. Hatchard JL, Fooks GJ, Gilmore AB. Standardised tobacco packaging: a health policy case study of corporate conflict expansion and adaptation. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012634. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ulucanlar S, Fooks GJ, Hatchard JL, et al. Representation and misrepresentation of scientific evidence in contemporary tobacco regulation: a review of tobacco industry submissions to the UK government consultation on standardised packaging. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001629. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hatchard JL, Evans-Reeves KA, Ulucanlar S, et al. How do corporations use evidence in public health policy making? The case of standardised tobacco packaging. The Lancet 2013;382:S42. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62467-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chapman S. Legal action by big tobacco against the Australian government's plain packaging law. Tob Control 2012;21:80–1. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Matthes BK, Robertson L, Gilmore AB. Needs of LMIC-based tobacco control advocates to counter tobacco industry policy interference: insights from semi-structured interviews. BMJ Open 2020;10:e044710. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Malone RE, Grundy Q, Bero LA. Tobacco industry denormalisation as a tobacco control intervention: a review. Tob Control 2012;21:162–70. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Antin TMJ, Lipperman-Kreda S, Hunt G. Tobacco denormalization as a public health strategy: implications for sexual and gender minorities. Am J Public Health 2015;105:2426–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ashley MJ, Cohen JE. What the public thinks about the tobacco industry and its products. Tob Control 2003;12:396–400. 10.1136/tc.12.4.396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Brandt A. The cigarette century New York: basic books, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gallagher A, Zatoński M, Hird T, et al. The tobacco industry's hypocrisy on illicit trade., 2020. Daily Maverick. Available: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-07-09-the-tobacco-industrys-hypocrisy-on-illicit-trade/ [Accessed 09 Jul 2020].

- 57. Tobacco Tactics . Illicit tobacco trade, 2021. Available: https://tobaccotactics.org/wiki/illicit-tobacco-trade/ [Accessed 25 Feb 2021].

- 58. Vermeulen S, Dillen M. Big tobacco, big avoidance. The investigative desk, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Proctor RN . Golden holocaust: origins of the cigarette catastrophe and the case for abolition Berkeley and Los Angeles. University of California Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kluger R. Ashes to ashes. New York: Vintage Books, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stuart C, Chotia A. Radio. PwC Southern Africa, 2016. Available: https://www.pwc.co.za/en/assets/pdf/enm-20120-chapter5.pdf [Accessed 01 Dec 2020].

- 62. National Treasury of the Republic of South Africa . Budget review, 2018. Available: http://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/national%20budget/2018/review/FullBR.pdf [Accessed 20 Oct 2019].

- 63. Solwandle N. Motsoaledi commits to amend tobacco act, 2018. SABC News. Available: https://www.sabcnews.com/sabcnews/motsoaledi-commits-amend-tobacco-act/ [Accessed 02 Nov 2019].

- 64. Neumann A. #HandsOffMyChoices campaign was designed to raise awareness of the tobacco bill. Daily Maverick, 2018. Available: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2018-09-04-handsoffmychoicescampaign-was-designed-to-raise-awareness-of-the-tobacco-bill-jti/ [Accessed 22 Oct 2019].

- 65. World Health Organization . World no tobacco day, 2019. Available: https://www.who.int/newsroom/events/detail/2019/05/31/default-calendar/world-no-tobacco-day [Accessed 04 Mar 2020].

- 66. Tactics T. South Africa: industry interference with the control of tobacco products and electronic delivery systems bill, 2020. Available: https://tobaccotactics.org/wiki/south-africa-industry-interference-with-thecontrol-of-tobacco-products-and-electronic-delivery-systems-bill/ [Accessed 03 Oct 2020].

- 67. van Dyk J. Did big tobacco buy Twitter? Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism 2018;2019 https://bhekisisa.org/article/2018-09-07-00-did-big-tobacco-buy-twitter-industry-fights-new-tobacco-controlbill/ [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chalumbira N. South Africa’s parliament considers tougher anti-smoking bill, 2018. Reuters. Available: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-safrica-tobacco-lawmaking-idUSKBN1L01NO [Accessed 03 Mar 2020].

- 69. Daniels L. #NotJustAJob campaign highlights threat illicit cigarette trade poses to SA jobs, 2018. IOL. Available: https://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/gauteng/notjustajob-campaign-highlights-threat-illicitcigarette-trade-poses-to-sa-jobs-16512120 [Accessed 03 Mar 2020].

- 70. Masemola K. Enforcing tobacco bill among informal traders is impractical and will cost jobs, 2018. Sunday Times. Available: https://www.timeslive.co.za/sunday-times/opinion-and-analysis/2018-09-01-enforcingtobacco-bill-among-informal-traders-is-impractical-and-will-cost-jobs/ [Accessed 04 Mar 2020].

- 71. Fair Play Movement . FAWU leads March over rampant tobacco tax evasion and illcit trade, 2018. FairPlay. Available: https://fairplaymovement.org/fawu-leads-march-over-rampant-tobacco-tax-evasion-and-illicittrade/ [Accessed 04 Mar 2020].

- 72. Khumalo K. Treasury warned on raising excise tax, 2019. IOL. Available: https://www.iol.co.za/businessreport/economy/treasury-warned-on-raising-excise-tax-18898744 [Accessed 01 Mar 2020].

- 73. National Treasury of the Republic of South Africa . Budget review 2018, 2019. Available: http://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/national%20budget/2019/review/FullBR.pdf [Accessed 20 Oct 2019].

- 74. Vellios N, Filby S. Sifting out facts in the tactics used by the tobacco industry against plain packaging, 2019. Daily Maverick. Available: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2019-08-04-sifting-out-facts-in-the-tactics-used-bythe-tobacco-industry-against-plain-packaging/ [Accessed 22 Mar 2020].

- 75. Unknown . The StAR publishes blank cover, 2019. Bizcommunity. Available: https://www.bizcommunity.com/Article/196/90/193591.html [Accessed 05 Mar 2020].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

tobaccocontrol-2021-056675supp001.pdf (147.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.