This editorial refers to ‘Inverse association between apolipoprotein C-II and cardiovascular mortality: role of lipoprotein lipase activity modulation’, by G. Silbernagel et al., https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad261.

‘I see too deep and too much’

Henri Barbusse, The Inferno (L’Enfer)

With the renewed interest in triglyceride-carrying lipoproteins in atherogenesis,1 researchers are evaluating several players with roles in metabolism of these particles. The central character is lipoprotein lipase (LPL), the plasma enzyme responsible for hydrolysis of triglyceride-carrying particles such as chylomicrons and very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDLs). LPL activity reduces triglyceride levels, and both primary and secondary insufficiency of LPL leads to hypertriglyceridaemia.2 Mild to moderate hypertriglyceridaemia is associated with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), while severe hypertriglyceridaemia can predispose to acute pancreatitis, and sometimes ASCVD.3 Endothelial bound LPL requires a supporting cast of molecules that can either facilitate or impede its activity. For instance, LPL is suppressed by apolipoprotein (apo) C-III4 and angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3),5 while its activity is promoted by apo C-II6 and apo A-V.2 LPL function also depends on glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored high-density lipoprotein-binding protein 1 (GPIHBP1) and lipase mature factor 1 (LMF1).2 In this issue of the European Heart Journal, Silbernagel and colleagues focus on apo C-II.7

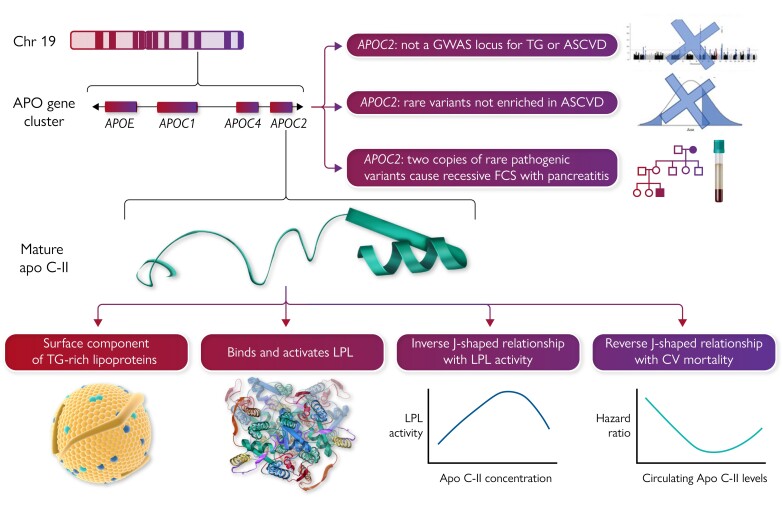

The APOC2 gene resides within the APOE–C1–C4–C2 gene cluster on chromosome 19q13.32 and encodes a 101 amino acid precursor (see the Graphical Abstract).8 The signal peptide is cleaved to yield a mature 79 amino acid protein that is a component of chylomicrons, VLDL, LDL, and HDL.6 Apo C-II contains three amphipathic α-helices, an N-terminal lipid-binding domain, and a C-terminal LPL-binding domain. Apo C-II and apo C-III have a ying–yang relationship, with the former usually acting as an accelerator and the latter as a brake on LPL activity.6 However, additional complexities characterize the actions of these small proteins; for instance, both the complete absence of circulating apo C-II—as seen in rare human deficiency syndromes—as well as very high concentrations of apo C-II—as seen in human APOC2 transgenic mice9—are associated with severe hypertriglyceridaemia.

Graphical Abstract .

Apolipoprotein (apo) C-II, whose two-dimensional structure is shown in the middle left, is the product of the APOC2 gene, which is part of the APOE–C1–C4–C2 (APO) gene cluster on the long arm of chromosome (Chr) 19. Mature circulating apo C-II is a component of triglyceride (TG)-rich lipoproteins and is an essential activator of endothelial-bound lipoprotein lipase (LPL), whose two-dimensional structure is also shown. Plasma levels of apo C-II have non-linear relationships with both TG levels and cardiovascular (CV) mortality. Genetic investigations, including genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and Mendelian randomization and DNA sequencing, do not provide convincing evidence that APOC2 is a causal determinant for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). Patients with two copies, i.e. biallelic homozygous or compound heterozygous, develop familial chylomicronaemia syndrome (FCS), an ultrarare condition characterized primarily by acute pancreatitis and certain physical manifestations, but generally not ASCVD. In contrast, single copies of such variants predispose to (but do not absolutely guarantee) developing mild, moderate, and even severe hypertriglyceridaemia.

A key role for apo C-II as an essential activator of LPL was established in 1978, when Drs Alick Little and Carl Breckenridge evaluated a patient who presented with relapsing acute pancreatitis and severe hypertriglyceridaemia.10 They noted transient normalization of his triglyceride level after he received a blood transfusion. This patient was found to have a deficiency of circulating apo C-II, which was qualitatively abnormal. Peptide sequencing later showed that affected homozygous family members had a mutated apo C-II variant, termed ‘apo C-II-Toronto’.11 This was the first identified human mutation in an apolipoprotein that caused dyslipidaemia. Subsequently, working with Dr Philip Connelly, Dr Little identified a second circulating variant termed ‘apo C-II-St. Michael’ in a Canadian family with multiple affected homozygotes who, likewise, expressed chylomicronaemia and acute pancreatitis.12

Since 1980, >30 pathogenic APOC2 variants have been reported that, when present on both alleles, i.e. bi-allelic homozygous or compound heterozygous, cause complete deficiency of apo C-II, producing a phenotype that resembles homozygous LPL deficiency, formerly known as Fredrickson hyperlipoproteinaemia type 1.6 We now know that bi-allelic pathogenic variants not only in LPL and APOC2 but also in APOA5, GPIHBP1, and LMF1 produce a similar phenotype named ‘familial chylomicronaemia syndrome’ (FCS).13 The main risk to health among individuals with FCS is pancreatitis rather than ASCVD.

Chylomicrons are not considered to be atherogenic. FCS patients also have a relative deficiency of proatherogenic remnant particles that are downstream products of normal lipolysis. In contrast, in those with partial or relative LPL deficiency, i.e. multifactorial chylomicronaemia syndrome (MCS), smaller triglyceride-rich lipoproteins such as VLDL and their remnants accumulate, leading to increased risk of ASCVD.13 While triglyceride molecules are not directly atherogenic, smaller triglyceride-rich lipoproteins contain cholesterol, which can be deposited within the arterial wall, leading to atherosclerotic plaques. Hypertriglyceridaemia in patients with MCS has a complex genetic basis, including polygenic risk from accumulated common DNA variants and sometimes heterozygosity for rare pathogenic variants in LPL, APOC2, APOA5, GPIHBP1, and LMF1 genes.8 Because cofactors for LPL such as apo C-II are central to the catabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, investigating their potential role in ASCVD risk is sensible. Such investigations are now reported in the European Heart Journal.7

Silbernagel and colleagues studied 3141 participants from the LURIC study at the Ludwigshafen Heart Center. Over a 10-year follow-up period, 590 individuals died from cardiovascular disease. The mean baseline plasma apo C-II concentration in participants was 4.5 ± 2.4 mg/dL, with the lowest and highest quintiles having levels of 1.98 ± 0.81 and 7.70 ± 2.91 mg/dL, respectively. Across the quintiles of apo C-II levels, there were significant stepwise increases in several risk factors, including body mass index, and plasma total and VLDL triglyceride, apo B and apo C-III. In contrast, apo C-II levels were negatively correlated with HDL cholesterol but unrelated to either LDL cholesterol or lipoprotein(a). Cardiovascular mortality followed a reverse J-shaped relationship with apo C-II levels, with hazard ratios of ∼1.7 and ∼1.4, respectively, in the lowest and highest quintiles relative to the middle quintile. However, non-fatal cardiovascular endpoints individually showed variable relationships with quintiles of apo C-II levels.

The authors also employed in vitro experiments to evaluate the ability of apo C-II to activate LPL complexed with GPIHBP1 using both an artificial substrate and human VLDL. As more apo C-II was added exogenously, they found an inverted J-shaped relationship, i.e. there was very low activity and somewhat low activity of the LPL–GPIHBP1 complex at very low and very high levels of apo C-II, respectively, with the highest LPL activity seen with intermediate levels of apo C-II. When using apo C-II-containing human VLDL as a substrate, they found that LPL–GPIHBP1 complex activity was attenuated by a neutralizing anti-apo C-II antibody, confirming the activating role of apo C-II. In aggregate, the authors proposed that pharmacologically raising depressed circulating apo C-II levels would improve LPL activity, in turn reducing triglyceride levels and possibly also reducing ASCVD risk.

This work adds fresh new data to the archival biochemical studies on apo C-II and LPL. However, while Silbernagel and colleagues advocate that boosting apo C-II may help to correct hypertriglyceridaemia, their findings also raise certain questions. For example, what explains the Goldilocks relationship of apo C-II concentration with LPL activity? Observing low LPL activity when apo C-II is low seems easy to understand since apo C-II is an essential cofactor for lipolysis, but why is LPL activity suppressed with high apo C-II levels? A genetically modified mouse may provide a clue. In human APOC2 transgenic mice expressing extremely high levels of apo C-II, Shachter and Breslow found that VLDL particles became freakishly apo C-II-rich and simultaneously apo E-poor.9 These qualitatively extreme VLDL particles bound poorly to heparin and were less accessible to endothelial bound LPL, probably explaining the attenuated lipolysis.

The mirror-image J-shaped relationships between apo C-II levels and both LPL activity and ASCVD mortality indicates that apo C-II delivers optimal effects within a relatively narrow window of plasma concentration. Hitting this biochemical sweet spot by precisely boosting its levels pharmacologically—but not over- or undershooting—might prove challenging compared with blunt suppression of different targets that show more straightforward effects, such as apo C-III or ANGPTL3.

Furthermore, human genetic studies indicate that compared with such validated targets as proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9), apo C-III, and ANGPTL3, apo C-II might be more problematic. For instance, genome-wide association studies have yet to directly implicate common DNA variation in APOC2 in either triglyceride levels or the risk of ASCVD outcomes, although the closely linked APOE gene is associated with both LDL cholesterol levels and ASCVD risk.14 In addition, next-generation DNA sequencing experiments show that heterozygous rare loss-of-function variants in APOC2, together with those in the other FCS genes, namely LPL, APOA5, LMF1, and GPIHBP1, are statistically over-represented in patients with MCS.15 However, there is minimal evidence that rare disabling APOC2 variants are associated with ASCVD risk in Mendelian randomization or DNA sequencing studies of ASCVD cohorts. Finally, patients with complete apo C-II deficiency—and FCS patients generally—do not as a rule present with increased ASCVD endpoints, although certain exceptions prove the rule.12 Indeed, two homozygous patients with apo C-II-Toronto whom I follow clinically, each in their eighth decade of life, remain free of ASCVD.

Thus, Silbernagel and colleagues are to be congratulated for shining the spotlight anew on apo C-II, a neglected and surprisingly complex little protein. The questions raised by their interesting studies should stimulate more research that would ideally deconvolute some of the apparent paradoxes posed by this essential cofactor for LPL. Population studies of apo C-II DNA variants, for instance in the UK Biobank, may help. Also, durable mimetic peptides such as D6PV16 might advance our physiological and pharmacological understanding. The clearest case for apo C-II supplementation would be for prophylaxis of pancreatitis in patients with the apo C-II deficiency subtype of FCS. However, the findings of Silbernagel and colleagues, if confirmed and expanded upon, may point towards a new path with potentially wider benefits.

Data availability

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this research.

Funding

R.A.H. is supported by the Jacob J. Wolfe Distinguished Medical Research Chair, the Edith Schulich Vinet Research Chair, and the Martha G. Blackburn Chair in Cardiovascular Research. R.A.H. holds operating grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Foundation award), the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada [G-21-0031455], and the Academic Medical Association of Southwestern Ontario [INN21-011].

References

- 1. Ginsberg HN, Packard CJ, Chapman MJ, Borén J, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Averna M, et al. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and their remnants: metabolic insights, role in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and emerging therapeutic strategies—a consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J 2021;42:4791–4806. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Basu D, Goldberg IJ. Regulation of lipoprotein lipase-mediated lipolysis of triglycerides. Curr Opin Lipidol 2020;31:154–160. 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laufs U, Parhofer KG, Ginsberg HN, Hegele RA. Clinical review on triglycerides. Eur Heart J 2020;41:99–109. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hegele RA. Apolipoprotein C-III inhibition to lower triglycerides: one ring to rule them all? Eur Heart J 2022;43:1413–1415. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kersten S. ANGPTL3 as therapeutic target. Curr Opin Lipidol 2021;32:335–341. 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wolska A, Reimund M, Remaley AT. Apolipoprotein C-II: the re-emergence of a forgotten factor. Curr Opin Lipidol 2020;31:147–153. 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Silbernagel G, Chen YQ, Rief M, Kleber ME, Hoffmann MM, Stojakovic T, et al. Inverse association between apolipoprotein C-II and cardiovascular mortality: role of lipoprotein lipase activity modulation. Eur Heart J 2023;44:2335–2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dron JS, Hegele RA. Genetics of hypertriglyceridemia. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020;11:455. 10.3389/fendo.2020.00455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shachter NS, Hayek T, Leff T, Smith JD, Rosenberg DW, Walsh A, et al. Overexpression of apolipoprotein CII causes hypertriglyceridemia in transgenic mice. J Clin Invest 1994;93:1683–1690. 10.1172/JCI117151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Breckenridge WC, Little JA, Steiner G, Chow A, Poapst M. Hypertriglyceridemia associated with deficiency of apolipoprotein C-II. N Engl J Med 1978;298:1265–1273. 10.1056/NEJM197806082982301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Connelly PW, Maguire GF, Hofmann T, Little JA. Structure of apolipoprotein C-IIToronto, a nonfunctional human apolipoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1987;84:270–273. 10.1073/pnas.84.1.270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Connelly PW, Maguire GF, Little JA. Apolipoprotein CII-St. Michael. Familial apolipoprotein CII deficiency associated with premature vascular disease. J Clin Invest 1987;80:1597–1606. 10.1172/JCI113246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chait A, Eckel RH. The chylomicronemia syndrome is most often multifactorial: a narrative review of causes and treatment. Ann Intern Med 2019;170:626–634. 10.7326/M19-0203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, Edmondson AC, Stylianou IM, Koseki M, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature 2010;466:707–713. 10.1038/nature09270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dron JS, Wang J, Cao H, McIntyre AD, Iacocca MA, Menard JR, et al. Severe hypertriglyceridemia is primarily polygenic. J Clin Lipidol 2019;13:80–88. 10.1016/j.jacl.2018.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wolska A, Lo L, Sviridov DO, Pourmousa M, Pryor M, Ghosh SS, et al. A dual apolipoprotein C-II mimetic-apolipoprotein C-III antagonist peptide lowers plasma triglycerides. Sci Transl Med 2020;12:eaaw7905. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw7905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this research.