Abstract

Background

Progress in breast cancer (BC) research relies on the availability of suitable cell lines that can be implanted in immunocompetent laboratory mice. The best studied mouse strain, C57BL/6, is also the only one for which multiple genetic variants are available to facilitate the exploration of the cancer-immunity dialog. Driven by the fact that no hormone receptor-positive (HR+) C57BL/6-derived mammary carcinoma cell lines are available, we decided to establish such cell lines.

Methods

BC was induced in female C57BL/6 mice using a synthetic progesterone analog (medroxyprogesterone acetate, MPA) combined with a DNA damaging agent (7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene, DMBA). Cell lines were established from these tumors and selected for dual (estrogen+progesterone) receptor positivity, as well as transplantability into C57BL/6 immunocompetent females.

Results

One cell line, which we called B6BC, fulfilled these criteria and allowed for the establishment of invasive estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) tumors with features of epithelial to mesenchymal transition that were abundantly infiltrated by myeloid immune populations but scarcely by T lymphocytes, as determined by single-nucleus RNA sequencing and high-dimensional leukocyte profiling. Such tumors failed to respond to programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) blockade, but reduced their growth on treatment with ER antagonists, as well as with anthracycline-based chemotherapy, which was not influenced by T-cell depletion. Moreover, B6BC-derived tumors reduced their growth on CD11b blockade, indicating tumor sustainment by myeloid cells. The immune environment and treatment responses recapitulated by B6BC-derived tumors diverged from those of ER+ TS/A cell-derived tumors in BALB/C mice, and of ER– E0771 cell-derived and MPA/DMBA-induced tumors in C57BL/6 mice.

Conclusions

B6BC is the first transplantable HR+ BC cell line derived from C57BL/6 mice and B6BC-derived tumors recapitulate the complex tumor microenvironment of locally advanced HR+ BC naturally resistant to PD-1 immunotherapy.

Keywords: Breast Neoplasms, Immunity, Immunocompetence, Tumor Microenvironment, Immunotherapy

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Hormone receptor-positive (HR+) breast cancer (BC) is the most commonly diagnosed and lethal neoplasm affecting women and remains so far resistant to immune checkpoint blockers such as programmed cell death-1 (PD-1). Preclinical mouse models accurately modeling the complex immune-context of advanced HR+BC are limited, explaining the lack of HR+BC cell lines transplantable into the most commonly used mouse strain (C57BL/6).

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

In our study we generated the first transplantable HR+ BC cell line derived from C57BL/6 mice, named B6BC. On inoculation in syngeneic counterparts B6BC-derived tumors recapitulate the complex tumor microenvironment of HR+ BC naturally resistant to PD-1 immunotherapy.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Our study provides a promising preclinical tool to better understand HR+BC (immuno)mechanisms and favor the development of (immuno)therapies, especially in the context of PD-1 resistance.

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC), the most prevalent malignancy developing in women (currently affecting one in eight to nine women), is diagnosed every year more frequently.1 This is in part explained by the improvement in diagnostic tools and population screenings,2 but also by the increasing exposure of women to BC risk factors including early menarche, low fertility, obesity, poor lifestyle and advanced age.3

At diagnosis, the degree of tumor invasiveness distinguishing early, locally advanced and metastatic disease (with the so-called ‘Tumor - lymph Node - Metastasis’ or TNM stage) and of positivity for the hormone receptors (HR) estrogen receptor (ER) and/or progesterone receptor (PR), as well as for ERBB2/HER2 receptor, will determine BC therapeutic choices.2 HR-positive (HR+ ERBB2−) tumors represent almost 70% of all diagnosed BC cases.1 HR+ and HER2-positive (HR+ or HR− ERBB2+) BCs in early-stage disease are generally managed with local therapy (such as surgery) together or not with systemic (neo-)adjuvant therapies targeting HR and ERBB2, respectively, accompanied in some cases by chemotherapy. Such systemic therapies and others (like CDK4/6 inhibitors for HR+ BC) are frequently the sole therapeutic option for locally-advanced and metastatic HR+ and HER2+ BC, as well as for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC or HR− ERBB2−) carcinomas.2

Despite these treatment differences among BC subtypes, in all of them the clinical efficacy of chemotherapy invariably relies on antitumor immune responses.4–6 Anthracycline-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy stimulates the invasion of BCs by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in those patients who exhibit complete pathological responses, and prior infiltration by T cells predicts the long-term outcome of adjuvant chemotherapy.5 6 Immunotherapies targeting programmed cell death-1 receptor (PD-1) on T lymphocytes have recently been incorporated into the clinical management of TNBC in combination with chemotherapy.7–9 However, similar immunotherapy combinations have failed against HR+ BC,10 11 which still represents the BC subtype with the highest number of patients that relapse and die.1 2 Of note, HR+ BC is considered the less infiltrated BC subtype regarding TIL density, indicative of a particular ‘lymphocyte-cold’ tumor microenvironment.10 However, HR+ BC are also infiltrated by the heterogeneous myeloid immune cell compartment, which comprises, among others, neutrophils, macrophages and dendritic cells with context-dependent protumorigenic and antitumorigenic effects.12 13 Immunotherapies targeting these cells are nowadays underdeveloped compared with T cell-targeted therapies. However, current efforts to decipher tumor myeloid heterogeneity promise futures advances in this field.10

The limited availability of suitable preclinical models that accurately model the complex immune-context of HR+ BC may also contribute to the current ‘immunotherapeutic-desert’.14 Such immunocompetent mouse models are essential for the present and future development of efficient long-lasting (immuno-) therapeutic strategies.15 In immunocompetent mice, BC can be induced by transgenic expression of oncogenes in mammary epithelial cells16 or by chemical carcinogenesis, which typically involves the combination of PR agonists, such as medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) for inducing the proliferation of mammary epithelia, and DNA damaging agents, such as 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA) to drive mutagenesis.17–19 MPA/DMBA-induced tumors are mostly HR+ and under natural- and chemotherapy-induced antitumor immunosurveillance, but are resistant to single agent immunotherapy targeting PD-1, rendering this model a suitable tool for the exploration of primary immunotherapy resistant HR+ BC.17 Unfortunately, MPA/DMBA-induced tumorigenesis requires up to 9 months,17 18 making it time-consuming and less affordable than cell-line derived models, which rely on the orthotopic injection of transplantable BC cells into the mammary fat pad of syngeneic recipient mice.15

In this context, it is noteworthy that HR+ BC cell lines transplantable into C57BL/6 mice are not available.14 C57BL/6 is the most widely used inbred mouse strain and the only one for which thousands of genetically modified substrains are available.20 For this reason, we decided to establish an HR+ BC cell line that would be transplantable to syngeneic C57BL/6 mice. Here, we report a strategy for establishing such cells and detail the molecular and immunological properties of the first transplantable, HR+ BC cell line derived from C57BL/6 mice, that we named B6BC. We compared these cells with the MPA/DMBA-induced tumor from which they derived and with commonly used syngeneic transplantable BC cell lines including TS/A (HR+ ERBB2− from the BALB/C mouse strain21), E0771 (also known as EO771) and AT-3 (both HR− ERBB2− from C57BL/6 mice12 22 23). Tumors arising from the newly generated B6BC cells mimic features of the tumor immune microenvironment of human HR+ BC, in particular, with respect to anti-PD-1 resistance.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and chemicals

Murine BC primary culture cell lines were established in-house as later specified, TS/A cells were a kindly gift of Dr Clothilde Thery (Institut Curie, Paris, France) and E0771 and AT-3 cells of Dr Laurence Zitvogel (Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France). Human BC cell lines MCF-7, BT-474 and BT-549 were kindly provided by the cell culture facility of CEINGE-Biotecnologie Avanzate s.c.a.r.l. (Naples, Italy). All cell lines were cultured as indicated in online supplemental materials. Unless specified otherwise, all reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, cell culture and tissue processing media and supplements were purchased from Gibco-Life Technologies and plasticware from Corning.

jitc-2023-007117supp001.pdf (277.1KB, pdf)

Cell treatments and proliferation assay

BC cells were seeded at 2–7×103/well in 96-well plates, allowed to adhere for at least 24 hours and treated with fulvestrant (Ref: S1191), RU-486 (Ref: S2606), lapatinib (Ref: S2111), ribociclib (Ref: S7440) (all from Selleck Chemicals), abemaciclib (Ref: T2381) and BLZ945 (Ref: T6119) (from TargetMol), 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT; Ref: H7904) and mitoxantrone (MTX, Ref: M6545) (from Sigma-Aldrich) or corresponding vehicles at the concentrations indicated in the figure legends. Hormone-depleted medium was used for 4-OHT, fulvestrant and RU-486. Four hours before time point accomplishment, 10 µL of 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)−2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) (5 mg/mL) was added to all wells. To dissolve formed formazan crystals, then medium was replaced by 100 µL of dimethylsulfoxide, incubated for 15 min with cells and absorbance was measured at 570 nm. Data were analyzed as specified in online supplemental materials.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

Total RNAs were extracted from snap-frozen microdissected tissues and cultured cells using RNeasy Mini Plus Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. To perform real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), first 1 µg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate (dNTPs) and random primers (Promega) and, second, 40 ng of complementary DNA (cDNA) were amplified with specific TaqMan probes (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (see online supplemental materials for details) on a StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with the following running conditions: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of target gene amplification (95°C for 1 s and 58°C for 20 s). Data were analyzed as specified in online supplemental materials.

Protein extraction and western blot

Thirty micrograms of total cell protein from snap-frozen microdissected tissues and cultured cells were loaded onto 4–12% polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen) and transferred to a 0.2 µM polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Bio-Rad) as further detailed in online supplemental materials. Membranes were blocked for unspecific antibody binding and incubated with suitable primary and secondary antibodies (see online supplemental materials) before development by chemiluminescence-based detection with Amersham ECL Prime (GE HealthCare) following manufacturer’s instructions. Images were acquired using the ImageQuant LAS 4000 software-assisted imager (GE HealthCare).

Animals

Six to nine weeks old female C57BL/6 or BALB/C mice were purchased from Envigo (UK) and housed in a pathogen-free, temperature-controlled environment with 12-hour day and night cycles. The animals received water and food ad libitum and were allowed to acclimate for at least 1 week. Animal experiments were conducted in compliance with the EU Directive 63/2010 and with protocol #22678 by the local Ethical Committee (‘C. Darwin’ registered at the French Ministry of Research).

MPA/DMBA tumor induction and monitoring

MPA/DMBA tumors were induced as previously described18 (see also online supplemental materials). Mice were routinely examined for tumor development by palpation and established tumors were monitored by caliper measurement. Tumor surface was calculated with the formula = ((length×width)×π)/4. When total tumor mass (which may comprise several tumors) reached a size ≥1.8 cm2 or if the animals showed signs of distress, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation and tumors were harvested for posterior analyses and processed to generate cancer cell lines.

Generation of cancer cell lines

MPA/DMBA tumors were mechanically and enzymatically dissociated using mouse tumor dissociation kit and gentleMACS Octo Dissociator with heaters (Miltenyi Biotec) following the manufacturer’s instructions under sterile conditions. Tumor cell suspensions were washed in cold HF solution (consisting of phenol red-free Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution supplemented with 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) and 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS)) and erythrocytes removed using red blood cell lysis buffer (BioLegend). Remaining cells were further dissociated with trypsin-EDTA (0.25%) and pre-warmed dispase solution (5 U/mL dispase (Worthington Biochemical) in DMEM/F12 media), before filtration through 70 µM strainers and further wash with HF solution. All centrifugation steps were performed at 400xg for 5 min. Single cell suspensions were plated on pre-warmed serum/fetuin-coated flasks (prepared by incubation of 2 mg/mL fetuin in DMEM/F12 with 20% FBS media for 1 hour) and cultured as specified in online supplemental materials. Medium was replaced after 24 or 48 hours from seeding. When first cell confluence was achieved, primary cultures were (partially) depleted in fibroblasts by differential resistance to trypsinization with TrypLE. Cell cultures were routinely checked and passed when cell confluence was of 70–80%.

Tumor growth of transplantable syngeneic mouse cell lines

Female mice were injected with 5×106 cells (for all primary cultures shown in figure 1C except B6BC cell lines (CL) cells), 2×105 B6BC CL, 7.5×104 TS/A CL, 1×105 E0771 CL, 5×105 AT3 CL cells in 150 µL of phosphate buffered saline subcutaneously (s.c.) into the right mammary fat pad. Tumor growth and animal survival were monitored as abovementioned for MPA/DMBA tumors and mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation when total tumor mass reached an average size of 0.5–1 cm2 (for cytofluorometric, histological and single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNAseq) analyses for B6BC TT) or ≥1.8 cm2 (for treatment response assessment and snRNAseq analyses of B6BC OT) or if depicting signs of discomfort.

Figure 1.

Generation and selection of a hormone receptor positive cell line from C57BL/6 mice transplantable to syngeneic immunocompetent counterparts. (A) Schematic representation of the schedule for mouse tumor induction by MPA/DMBA administration and for the subsequent generation of primary culture cell lines (CL) in three different media (medium 1–3) from the original MPA/DMBA tumors (OT) collected at the endpoint. Established cell lines were then injected subcutaneously (s.c) in the mammary fat pad of immunocompetent tumor-naïve C57BL/6 female mice generating transplanted tumors (TT). (B) Tumor-free survival (TFS) of the five C57BL/6 female mice developing the six original MPA/DMBA tumors (named OT1 to OT6) from which eight primary culture cell lines (called B1BC CL to B8BC CL) were established and give rise to eight transplanted tumors (named TT) when inoculated in syngeneic mice. (C) Tumor growth of original MPA/DMBA tumors (OT1 to OT6, n=1; black lines) compared with their cell line-derived tumors (B1BC TT to B8BC TT) once orthotopically transplanted in C57BL/6 female mice (n=2–5). The graphs show tumor size average±SEM pooled for graphical purposes. (D) RT-qPCR quantification of estrogen receptor α (ER α, Esr1) and progesterone receptor (PR, Pgr) gene expression levels on established cell lines (B1BC CL to B8BC CL) and the commonly used murine BC cell lines TS/A, E0771 and AT-3. Column graph shows average of 2-∆Ct values±SEM. Dots depict n=3 frozen cell pellets, each one assessed in one individual experiment out of three. Selected B6BC CL is highlighted in red. (E) Immunoblotting assessment of ERα and PR for TS/A, AT-3, B6BC and E0771 cell lines and original or transplanted tumors, as well as appropriate controls. Representative image of one membrane out of three. (F) Histological and molecular characterization of B6BC OT and its cell-line derived B6BC TT by hematoxylin-eosin-saffron staining (HES, first left panel) and immunochromogenic-staining of ERα, PR and the proliferation marker Ki-67. Scale bars: 100 µm. (G) Quantification of the percentage of positive nuclei among total nuclei for the stainings shown in figure 1F for B6BC OT (n=1) and TT and on TS/A, E0771 and AT-3 cell line-derived tumors (from online supplemental figure 1G) (n=4–10). Column graph shows average±SEM. Dots depict individual mice analyzed. Stats were calculated using ordinary one-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons corrected with Dunnett’s post hoc test. Exact p values for the comparisons performed are indicated in the graph. BC, breast cancer; DMBA, 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene: ERα, estrogen receptor alpha; MPA, medroxyprogesterone acetate.

jitc-2023-007117supp002.pdf (27.4MB, pdf)

Treatment of established mouse tumors

When tumors reached a surface of approximately 20–30 mm2, mice were randomized based on tumor size and treated with tamoxifen (10 µg/mL in drinking water; Ref: T5648, Sigma-Aldrich), fulvestrant (5 mg/mouse; Ref: S1191, Selleck Chemicals), MTX (5.17 mg/kg; Ref: M6545, Sigma-Aldrich) or corresponding vehicles as well as with the following antibodies (all from Bio X Cell): anti-PD-1 (200 µg/mouse; Ref: BE0273), anti-CD4 (100 µg/mouse; Ref: BE0003-1) and anti-CD8 (100 µg/mouse; Ref: BE0061) or anti-CD11b (200 µg/mouse; Ref: BX-BE0007) or with corresponding matched-isotype controls (Ref: BE0089, BE0090). Treatment frequencies appeared on figure legends and detailed on online supplemental materials. Researchers were not blinded to treatment arms.

Immunofluorescence cytofluorometric analyses

Freshly harvested tumors were dissociated to single cell suspensions and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated immune phenotyping antibodies for lymphocyte and myeloid populations for flow cytometry purposes as previously described17 and detailed in online supplemental materials. Fully stained samples were run through a BD LSRFortessa X-20 Cell Analyzer using BD FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). Post-acquisition analyses were performed using Omiq.ai (https://app.omiq.ai/) following the recommended pipeline (see also online supplemental materials).

Histological analyses of mouse tumors

Dissected tumors were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde before paraffin embedding. Freshly cut 5–6 µm sections were dewaxed before: (i) staining with Mayer’s hematoxylin, eosin and saffron (HES), (ii) chromogenic immunohistochemistry of estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), PR, Ki67, pan-cytokeratin, α-SMA, p63 and vimentin with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine or (iii) multiplex immunofluorescence labeling of lymphocytes (using CD3, CD4, CD8 and FoxP3 antibodies) with Akoya Opal (Opal 520, 570, 690 and 780, Akoya Biosciences) tyramid signal amplification, as detailed in online supplemental materials. Whole slides were imaged and analyzed as specified in online supplemental materials.

snRNAseq of frozen tumors

Total nuclei were extracted from snap-frozen microdissected tumors following the protocol described in24 and detailed in online supplemental materials, and loaded in the Chromium Controller with a targeted recovery of 8000 nuclei. snRNAseq libraries were generated using the 10x Genomics Chromium Single Cell 3′ kit V.3.1 and the 10x Chromium Controller (10x Genomics), according to the 10x Single Cell 3′ V.2 protocol. cDNA was purified with Dynabeads and amplified by 16 cycles of PCR (98°C for 45 s, (98°C for 20 s, 67°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min) × 16, 72°C for 1 min). The amplified cDNA was fragmented, end repaired, ligated with index adaptors and size selected with cleanups between each step using the SPRIselect reagent kit (Beckman Coulter) before barcoded library quality control with the Agilent Bioanalyzer. Libraries were sequenced by IntegraGen (https://integragen.com/) on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 as a 100 base paired-end reads. Full FASTQ files were aligned to the reference mouse genome GRCm38 using STAR in the Cell Ranger pipeline from 10x Genomics.

snRNAseq analyses

All snRNAseq analyses were conducted with Seurat V.4.3 R package on R V.4.2.2 (https://www.r-project.org).25 Individual sample data were filtrated and nuclei with more than 15% of mitochondrial genes were excluded. Nuclei with more than 1.000 RNA counts and 500 expressed genes in B6BC original tumor (OT) and more than 500 RNA counts and 300 expressed genes in B6BC transplanted tumors (TT) were retained for subsequent analyses. Filtered data were normalized and the 5.000 more variable features were identified using ‘vst’ method to select features and anchors for data integration of individual data sets. The merge data set was then used to perform classical Seurat analysis pipeline with data scaling and scanning for actual most variable features on principal component analysis (PCA) (explained by 20 first principal components) before dimensionality reduction by uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP). To segregate single cells in clusters, we performed clustering by ‘Shared Nearest Neighbors’ algorithm on the PCA dimensional-reduced integrated data with a resolution value=0.05 to retrieve the five main cell clusters within all cells and a resolution value=0.6 for the eleven leukocyte subclusters within the immune cell cluster. Cell clusters were analyzed using ‘MAST’ method26 for differential expressed genes (DEG) among other cell clusters and among tumors with a threshold of (adj) p value≤0.05; log2 fold change ≥1, corrected by Bonferroni. This gene list was used for Gene Ontology (GO) analysis with g:Profiler website tool (https://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/gost) with a significance threshold of (adj) p value≤0.05 adjusted by the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (false discovery rate).27 GO terms for graphical representation were selected taking into account the number of genes of interest contained in that GO term normalized by the number of total genes constituting the GO term (called % term size) with different thresholds for each cluster adapted to the number of genes of interest. Volcano plot representation of DEG was done with EnhancedVolcano V.1.14 (https://github.com/kevinblighe/EnhancedVolcano) while gene density plots on UMAPs were generated with plot_density function from the Nebulosa R package V.1.6.28 The heatmap was done using ComplexHeatmap package V.2.12.129 with gene expression converted by the score:

Statistical analyses

All in vitro data are presented as average±SEM of at least two technical replicates from at least three different samples of at least three independent experiments while all ex vivo data is presented as average±SEM of the total number of samples. For most in vitro and ex vivo data, statistical significance was calculated using GraphPad Prism software V.6 and V.9.5 and the tests indicated in the figure legends. For MTT cell proliferation assays, p values were extracted from the coefficients that are specific to a given treatment at a given time compared with time-matched vehicle-treated controls according to the function ‘lm(CellProliferation~time/treatment+experiment)’ of R (see online supplemental materials). Heatmap of online supplemental figure 1C was done using https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus/.

In vivo data representation and mouse numbers are indicated in the figure legends. Statistical analyses for tumor growth (TG) and survival curves were performed on the raw data (tumor area over time for each mouse) of individual or pooled experiments considering all measured days until the following day the first mouse in either group compared was sacrificed (for TG) or until all mice achieved tumor endpoint (for survival) and were calculated using TumGrowth web tool (https://kroemerlab.shinyapps.io/TumGrowth/) (see online supplemental materials for further details).

Results

Generation and selection of a transplantable ER+ BC cell line

Induction of orthotopic mammary tumors in C57BL/6 female mice with MPA/DMBA17 18 (figure 1A), led to the development of six OT, dubbed OT1 to OT6, in mammary glands from five animals (two tumors, OT2 and OT3, developed in the same mouse). Tumors appeared with variable intervals of latency (figure 1B) and showed distinct growth kinetics (figure 1C). At the indicated time points (figure 1C), OT were harvested and processed to establish primary cultures that were passaged to generate eight CL called B1BC CL to B8BC CL (figure 1A, B) (see Materials and Methods). On reinjection into the mammary fat pads of tumor-naïve female C57BL/6 mice, all CL led to the generation of TT named B1BC TT to B8BC TT (figure 1A, C), overcoming the previously reported immunological rejection of MPA/DMBA-derived CL in C57BL/6 mice.17 This may be in part explained by the injection of 10 times more cancer cells, leading to variable growth rates of TT, not always resembling those observed for OT (figure 1C, online supplemental figure 1A).

Next, to select an HR+ cell line, we quantified the expression of Esr1 (encoding ERα, the clinically relevant subunit of ER) and Pgr (for PR) by RT-PCR on the eight generated tumor CL and in three commonly employed mouse BC CL (TNBC AT-323 and E077122 cells from C57BL/6 mice and ER+ TS/A cells from BALB/C mice21). Although the generated tumor CL derived from Esr1-expressing and/or Pgr-expressing OT (online supplemental figure 1B), only B6BC CL cells continued to express high levels of both Esr1 and Pgr messenger RNAs (mRNAs), thus exhibiting dual HR positivity (figure 1D). The expression of ERα and PR by B6BC CL cells was also confirmed at the protein level by immunoblot analysis (figure 1E). Using RT-PCR, we also evaluated the expression of Erbb2 and other epithelial markers in all CL (online supplemental figure 1C). mRNA and protein levels of Erbb2 were concordant and low in B6BC CL cells (online supplemental figure 1D) as well as in other mouse CL. Accordingly, we selected the transplantable ER+ PR+ B6BC CL for further characterization.

In the first step, we compared cell line-derived B6BC TT to the original B6BC tumor (B6BC OT) and to reference cell line-derived tumors (TS/A TT, AT-3 TT and E0771 TT). Histologically, B6BC OT appeared as a multifocally invasive solid mammary adenocarcinoma mainly composed of numerous cords and islands (CI) of closely packed neoplastic epithelial cells with minimal glandular differentiation, embedded within a moderately abundant fibrovascular-mucinous stroma (figure 1F HES, online supplemental figure 1E,I). In contrast, B6BC TT were poorly delineated, densely cellular invasive malignant tumors composed of monomorphic spindle-shaped neoplastic cells within an inconspicuous connective tissue stroma (figure 1 HES, online supplemental figure 1I), resembling in some aspects more to TS/A than to AT-3 or E0771 TT (online supplemental figure 1G HES, I). Immunohistochemical analyses confirmed nuclear ERα expression in B6BC OT (although restricted to epithelial CI) and B6BC TT, with a lower proportion of ERα positive cells and ERα all-red score in the latter (figure 1E–G, online supplemental figure 1F,H left panel). In contrast, nuclear PR was totally absent in B6BC TT and only expressed by epithelial CI within B6BC OT, indicating PR downregulation on transplantation (figure 1E–G, online supplemental figure 1F,H right panel). As expected, TS/A TT were ER+ PR− while AT-3 and E0771 TT were ER− PR− (figure 1E and G, online supplemental figure 1G,H). The percentage of proliferating (nuclear Ki67+) cells seemed to increase in B6BC TT compared with the neoplastic epithelial CI of OT, however both tumors exhibited much lower proliferative indices than TS/A, AT-3 and E0771 TT (figure 1G, online supplemental figure 1G,I).

Altogether these results identified B6BC CL as a syngeneic ER+ PR+ BC cell line able to generate transplantable ER+ malignant mammary tumors on inoculation into the mammary fat pad from C57BL/6 mice.

B6BC CL and TT are sensitive to HR-targeting therapies

To evaluate HR functionality in B6BC CL we antagonized ER activity with the selective ER modulator 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) and the ER downregulator fulvestrant, while we blocked PR with the mixed progesterone/glucocorticoid receptor antagonist RU-486 (mifepristone). B6BC CL proliferated less on treatment with 4-OHT, fulvestrant and RU-486 already after 24 hours post-treatment (figure 2A, red bars). This response was comparable to that observed in the human ER+ PR+ MCF-7 BC cell line (figure 2A, green bars), which is notoriously estrogen-dependent.30 Consistent with their low Erbb2 expression (online supplemental figure 1C,D), B6BC, TS/A and E0771 CL did not respond to the Erbb2 inhibitor lapatinib (figure 2A), contrasting with sensitive human ER+ ERBB2+ BT-474 cells (online supplemental figure 1D, figure 2A). Moreover, B6BC CL cells were more susceptible to growth inhibition by MTX than BT-474 cells (online supplemental figure 2B) and responded to CDK4/6 inhibitors ribociclib, abemaciclib and palbociclib with a similar pattern as BT-474 cells for the latter one (figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Hormone-sensitivity of B6BC CL cells and B6BC TT cell line-derived tumors. (A). Evaluation of cell proliferation by MTT assay on treatment of B6BC CL mouse cells and ER+ MCF7 human cells with ER antagonists 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT, 5 µM) and fulvestrant (100 µM) and the progesterone receptor antagonist mifepristone or RU-486 (40 µM) overtime (24−96 hours). Data represent the average fold-change compared with vehicle from at least three experiments±SEM. (B) Schedule for the subcutaneous (s.c.) mammary orthotopic implantation and treatment of established B6BC TT with orally-available tamoxifen (10 µg/mL in drinking water) and weekly s.c. injection of fulvestrant (5 mg per week) or appropriate matched vehicles. (C, D) Tumor growth (left panel) and percentage of overall animal survival (OS, right panel) of B6BC TT-bearing mice treated with tamoxifen (n=6–8 mice) (C) or fulvestrant (n=6–8 mice) (D). For tumor growth, the graphs show tumor size average±SEM. (E) Immunohistochemical analyses of ERα in vehicle-treated and fulvestrant-treated tumors (n=3–4 tumors) collected at the end of the survival curves in (D). One representative image per treatment is shown. Bar scales: 100 µm. Column graphs show average±SEM. Dots depict individual mice analyzed. Statistical analyses were performed as follows: (A) p values were estimated using the linear model described in Materials and Methods; (C, D) using TumGrowth website (https://kroemerlab.shinyapps.io/ TumGrowth/) and (E) by unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. Exact p values for the comparisons performed are indicated in the graph. (Adj) p value=*<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. BC, breast cancer; CL, cell lines; ER, estrogen receptor; ERα, estrogen receptor alpha; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)−2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide; TT, transplanted tumors.

Accordingly, treatment of B6BC TT established in female C57BL/6 mice with these ER antagonists (figure 2B) resulted in significant tumor growth inhibition and increased animal survival, both in response to oral tamoxifen (figure 2C) and to weekly s.c. injections of fulvestrant (figure 2D). Immunohistochemical staining of ERα in vehicle-treated and fulvestrant-treated B6BC TT demonstrated a significant reduction of nuclear ERα+ cells in the latter (figure 2E), despite the presence of some ERα+ normal mammary gland acini within the tumor mass (online supplemental figure 2D). In contrast, the percentage of proliferating (Ki67+) cells remained unchanged on fulvestrant treatment (online supplemental figure 2E). Overall, these results confirmed the partial HR dependency of B6BC CL cells and B6BC TT derived from them.

SnRNAseq reveals signs of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in B6BC TT compared with epithelial-like B6BC OT

To better characterize B6BC OT and TT at the multicellular level, we performed snRNAseq on 8.000 nuclei from two frozen tumors (one OT and one TT). After a quality control filter of individual tumors, both data sets were integrated to perform shared cell clustering and intersample differential analyses (see Materials and Methods). Dimensionality reduction by UMAP revealed five clusters (1–5) (figure 3A), with four of them (1, 2, 3 and 5) composed of cells belonging to both tumors (figure 3B). Only cluster 4 was almost exclusively composed of B6BC OT cells (figure 3B). Non-cancer cell populations that appeared in clusters 2, 3 and 5 exhibited upregulation of genes associated with immune cells (such as Ptprc for CD45), endothelial cells and vessels (like Pecam1) and BC associated fibroblasts (like Pdgfrb),31 respectively (figure 3C, online supplemental table 1). In contrast, clusters 1 and 4 exhibited features of mammary epithelial cells and murine BC cells and stem cells, such as Epcam, Cd44 or Csn3 32 33 (figure 3C, online supplemental table 1).

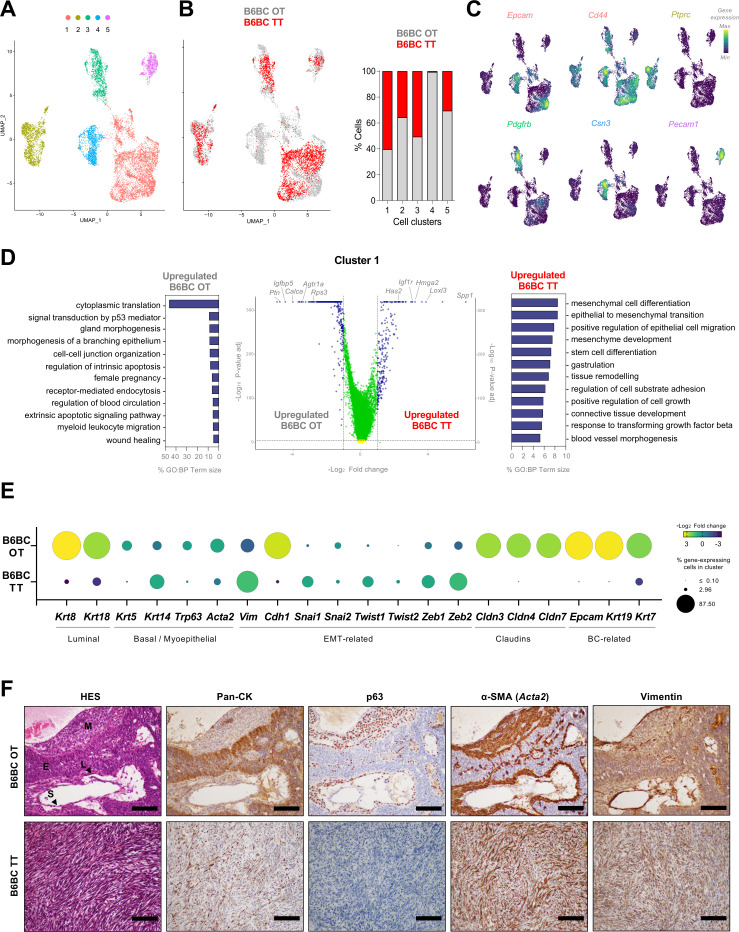

Figure 3.

B6BC TT exhibit features of epithelial to mesenchymal transition compared with the original B6BC OT they derived from. (A). UMAP projecting the clusters with main cell identities (clusters 1–5) identified within all filtered merged cell nuclei subjected to single-nucleus RNA sequencing analysis and derived from a piece of frozen tissue of B6BC OT and B6BC TT (n=1 for each). (B) Same UMAP as in (A) color-coded by tumor type (B6BC OT in gray and B6BC TT in red) (left panel) and bar graphs showing the percentage of cells in each cluster belonging to each tumor type (right panel). (C) Density plots for the expression of lineage marker genes belonging to the five clusters identified on (A), for which UMAP projection is recovered. (D) Volcano plot of main differentially expressed genes (DEG) (log2 fold change >1, (adj) p value<10−5) in cancer cells of cluster 1 between B6BC OT and B6BC TT (central panel). GO biological process (BP) term analysis of the selected DEG of B6BC OT (left panel) and B6BC TT (right panel) using g:Profiler website (https://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/). The bar graphs show the percentage of term size and are color-coded by term (adj) p value provided by g:Profiler. (E) Bubble-plot exhibiting the percentage of cancer cells of cluster 1 in B6BC OT and B6BC TT (bubble size) expressing the indicated genes as well as the fold change (bubble color) comparison between tumors. (F) Molecular characterization of B6BC OT and B6BC TT with chromogenic-staining of cytokeratins (here named Pan-CK), p63 (corresponding to the gene Trp63), α-SMA (Acta2 gene) and vimentin (gene). Tumor zonal differentiation marker expression can be repaired with aid of the hematoxylin-eosin-saffron staining (HES, first left panel, according to the regions defined in supplemental figure 1E (E, Epithelial cords and islands; L, Lining squamous cells; M, Myoepithelial cells -interstitial; S, Stromal cells).). Scale bars: 100 µm. BC, breast cancer; GO, Gene Ontology; OT, original tumor; TT, transplanted tumors.

jitc-2023-007117supp003.xlsx (4.3MB, xlsx)

To further characterize the differences between B6BC OT and TT at the level of BC cells, we focused on the tumor-shared cluster 1. We performed differential gene expression analysis between tumors to select upregulated genes in each (as depicted in the volcano plot by blue dots) for subsequent GO analyses (figure 3D). B6BC OT genes were associated to GO biological process (GO:BP) terms related to cancer cell-intrinsic features such as translation, female gland epithelium development and cell adhesion but also to microenvironment cues like myeloid leukocyte migration (figure 3D, left and central panel, online supplemental table 1). Conversely, B6BC TT-specific GO:BP terms were related to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), stem cell differentiation, response to transforming growth factor beta, cell-substrate adhesion and epithelial cell migration (figure 3D, right and central panel, (online supplemental table 1). These results indicate the acquisition of an EMT-like phenotype19 34 35 by B6BC TT compared with more epithelial-like B6BC OT cancer cells.

To examine this hypothesis, we selected a series of relevant mammary genes32–34 and analyzed their expression levels and the percentage of cancer cells expressing them in B6BC OT and TT (figure 3E). Luminal epithelial (Krt8, Krt18), BC cytoskeleton (Epcam, Krt19, Krt7) and cell–cell adhesion (Cdh1, Cldn3, Cldn4, Cldn7) factors were present and enriched in more than 60% of B6BC OT cancer cells in contrast to their minimal presence (<8% cells) in B6BC TT. Of note, claudins were almost completely absent (0–0.1% cells) in B6BC TT cancers, which is a characteristic feature of the so-called claudin-low BC phenotype.19 34 36 Both OT and TT presented a variety of basal/myoepithelial markers (such as Trp63 and Acta2 coding for p63 and α-SMA, respectively) at different cell proportions. However, EMT-related factors, such as the mesenchymal marker vimentin (Vim) were upregulated and more present in B6BC TT cancer cells (1–50% cells) than B6BC OT (0–20%) (figure 3E).

To corroborate these findings, we performed immunohistochemistry of cytokeratins (using a pan-cytokeratin cocktail), p63, α-SMA and Vim (figure 3F) in B6BC OT and TT. While these markers showed a clear cell type-specific spatial distribution in B6BC OT, there was no obvious topography in B6BC TT (figure 3F, online supplemental figure 2F). As expected, cytokeratins were expressed at a higher level in B6BC OT, especially in OT epithelial CI, than in TT, which showed a strong diffuse cytoplasmic staining. In contrast, nuclear p63 was completely absent from B6BC TT and restricted to lining squamous and interstitial myoepithelial cells in B6BC OT. Both tumors expressed high levels of cytoplasmic α-SMA, with a cell distribution pattern similar to p63 for B6BC OT. In contrast, Vim was abundant in the cytoplasm of B6BC TT cancer cells but mostly restricted to connective-tissue stromal cells in B6BC OT (figure 3F, online supplemental figure 2F).

Altogether, these results suggest that, compared with B6BC OT, B6BC TT cancer cells have reduced their mammary epithelial characteristics and acquired EMT-like features.

B6BC TT are poorly infiltrated by lymphocytes and are not under T-cell immunosurveillance

Tumor infiltrating immune cells were present in all studied tumors figure 1I) and were the second most abundant population recovered by snRNAseq in B6BC OT and TT (figure 3A–C). To better characterize these cells, we examined different panels of phenotypic leukocyte markers on freshly dissociated bulk B6BC, TS/A and E0771 TT by immunofluorescence-based multiparameter flow cytometry.

We first analyzed these data by manually supervised analysis (figure 3), normalizing cell counts by the number of total living cells to minimize the impact of structural tumor differences (online supplemental figure 1I; see online supplemental figure 4A for cell per tumor weight counts). Tumor-infiltrating leukocytes (CD45+) represented more than 60% of living dissociated cells in TS/A and E0771 TT, but less than 3% in B6BC TT. Regarding TILs, NK (CD3− Nkp46+) and T (CD3+ Nkp46−) cells were significantly more abundant in TS/A than in E0771 and B6BC TT (figure 4A, online supplemental figure 4B), while B cells constituted a minority in all TT (online supplemental figure 4C). Among T cell subsets, CD4+CD8−, CD4−CD8+ and TCRγδ+ T lymphocytes were also significantly more abundant in TS/A TT than in E0771 and B6BC TT. Only regulatory T lymphocytes (CD4+ CD8− FoxP3+ CD25+) were similarly present in TS/A and E0771 TT, and less abundant in B6BC TT (figure 4A). As such, the ratio of CD8+/FoxP3+ cells, associated with good prognosis,4 was significantly higher in TS/A than in E0771 TT (figure 4B). Similar trends in T lymphocyte composition were observed by multiplex immunofluorescence on histological tumor sections (online supplemental figure 4D,E).

Figure 4.

B6BC TT are poorly infiltrated by lymphocytes, not immunomodulated by T cells and exhibit resistance to single-agent anti-PD-1 treatment. (A–D) Fresh matched-size (0.5−1 cm2) harvested B6BC TT (n=6), TS/A TT (n=7) and E0771 TT (n=6) cell line-derived mammary orthotopic tumors were dissociated to single cell suspensions and analyzed by multiparametric flow cytometry. (A) Normalized percentage of the different leukoycte populations indicated in total living (Live/Dead negative) cells for B6BC, TS/A and E0771 TT and (B) ratio of CD3+ CD8+ over CD3+ CD4+ FoxP3+ lymphocytes on these tumors. In both dots depict individual mice analyzed and the line shows average±SEM. For the first panel in (A) corresponding to total leukocytes (CD45+), data from two different flow cytometry experiments (the one in this figure and the one in figure 5A–C) analyzed in the same way were pooled and stats were calculated on raw pooled data. (C) Visualization on opt-SNE of FlowSOM secreted clusters (L1 to L12, k-means=12) on total CD3+ cells from B6BC TT (left), TS/A TT (middle) and E0771 TT (right) tumors together (left panel). The heatmap shows the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of each protein marker per cluster (right panel). The MFI color-code of each protein marker is conditioned per ‘all clusters’ (columns) expression. (D) Bar graph with the percentage of CD3+ cells belonging to each cell cluster defined on (B) according to tumor type. Line shows average±SEM. Stats symbol comparisons: (*) B6BC TT versus TS/A TT; (#) B6BC TT versus E0771 TT and ($) TS/A TT versus E0771 TT. Only significant p values are shown. (E, F, G) Schedule for subcutaneous mammary implantation of B6BC TT and TS/A TT. By means of monoclonal antibodies, B6BC TT and TS/A TT BC naïve (E) or tumor-bearing mice (F, G) were depleted of CD4 and CD8 expressing cells (100 µg/mouse of each, intraperitoneally i.p.) (E, F), subjected to PD-1 blockade (200 µg/mouse, i.p.) (G) or treated with matched-isotype control antibodies. In (F), this treatment was concomitant with the administration of a single dose of the anthracycline mitoxantrone (MTX, 5.17 mg/kg, i.p.). The number of animals was: In (E) for isotype and α-CD4+α-CD8, in B6BC TT n=8, 10 and in TS/A TT n=8, 10, respectively. In (F), in this order, for isotype, α-CD4+α-CD8, MTX+isotype and MTX+α-CD4+α-CD8, in B6BC TT n=13, 15, 19, 15 and in TS/A TT n=8, 10, 10, 10, respectively. In (G) for isotype and α-PD-1, in B6BC TT n=6, 9 and in TS/A TT n=6, 11, respectively. (H) Tumor growth response of B6BC TT and TS/A TT naïve or tumor-bearing mice to the indicated treatments. Graphs show tumor size average±SEM. In left and central panel for B6BC TT, tumor growth data from two individual experiments was pooled for graphical purposes. Statistical analysis was performed as follows: (A, B) Ordinary one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or (D) two-way ANOVA both corrected for multiple comparisons with Tukey’s post hoc test and (H) using TumGrowth website in raw (pooled, when applying) data. (Adj) p value=*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001). Exact p values are indicated in the graphs or available in online supplemental table 3. BC, breast cancer; CL, cell lines; PD-1, programmed cell death-1; s.c., subcutaneously; TT, transplanted tumors.

jitc-2023-007117supp005.xlsx (31.7KB, xlsx)

To further dissect the heterogeneity of tumor-infiltrating T cells we analyzed by semi-supervised clustering CD3+ T cells of all TT together. We performed dimensionality reduction by opt-SNE and clustering using FlowSOM to retrieve 12 clusters (numbered L1 to L12) (figure 4C). This analysis confirmed predominance of regulatory T lymphocytes (L3 and L8) over CD4+ helper T cells (L5) in total CD3+ T cells in E0771, especially compared with TS/A TT (figure 4D). Interestingly, aside from minority cell clusters (L2 and L6), PD-1 expression was especially elevated among these T regulatory clusters (figure 4C). Furthermore, we found that a cluster of CD3+ CD8low CD4− FoxP3low (L4), likely corresponding to poorly differentiated immunosuppressor CD8+T cells,37 was over-represented in B6BC compared with TS/A and E0771 TT (figure 4D). Taken together, these results indicate a characteristically high T-cell tumor infiltration of TS/A TT compared with B6BC and E0771 TT, which present an overall similar lymphocyte composition, mostly differing by the abundance of likely immunosuppressive FoxP3-expressing CD8low T cells and CD4+ T cells.

Next, to evaluate T-cell contribution to antitumor responses of B6BC and TS/A TT, we depleted CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes using suitable monoclonal antibodies in two different settings (figure 4E,F). In the first setting, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were eliminated before the inoculation of B6BC and TS/A cells (figure 4E). While this depletion had no impact on B6BC progression, TS/A TT grew faster in CD4+ and CD8+ T cell-depleted animals than in matched isotype-treated counterparts (figure 4H left panel). Second, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were eliminated at the moment that the tumors reached a surface of 20–30 mm2 (figure 4F), with no impact on the growth of neither B6BC nor TS/A TT (figure 4H central panel). In some animals, this depletion was concomitant with the administration of a single dose of MTX, an anthracycline-based chemotherapy which induces immunogenic cell death (ICD)38 (figure 4F, online supplemental figure 4F). Both B6BC and TS/A TT reduced their tumor growth on MTX treatment. However, the depletion of T cells only compromised MTX efficacy against TS/A TT, not against B6BC (figure 4H central panel). Finally, we performed a three-dose treatment with the immune checkpoint blocker anti-PD-1 to target PD-1+ cells in established tumors (figure 4G). These cells represented a bigger proportion of CD3+ T cells in E0771 than in B6BC and TS/A TT (online supplemental figure 4G). Of note, anti-PD-1 treatment significantly reduced E0771 TT growth (online supplemental figure 4H) but could not control B6BC or TS/A TT progression (figure 4H right panel).

Altogether these results demonstrate that, in contrast to TS/A TT, B6BC TT progress independently of natural and therapeutically-induced antitumor T-cell responses. However, none of these ER+ BC tumors respond to immunotherapy targeting PD-1, as opposed to ER− E0771 TT.

CD11b+ myeloid cells dominate the immune landscape and provide tumor sustainment to B6BC cancers

Lymphocytes only represented 15–35% of all leukocytes infiltrating B6BC, E0771 and TS/A TT, which mostly contained myeloid cells (figure 4A, online supplemental figure 4B, C). Thus, we performed high-dimensional cytofluorometric analyses of tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells, first focusing on the pan-myeloid marker CD11b. CD45+ CD11b+ myeloid cells constituted ≥65% of all tumor-infiltrating leukocytes (figure 5A, online supplemental figure 5A). To dissect the heterogeneity of these CD11b+ myeloid cells, we performed semi-supervised clustering of CD11b+ cells of all TT together as above (figure 4) and retrieved 10 CD11b+ cell subsets (M1 to M10 CD11b+ clusters) (figure 5B). TS/A TT mostly contained CD11b+ macrophages expressing low levels of major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-II and high levels of M1/M2 polarization markers CD38 and CD206 (M9 CD11b+ cluster with a CD11c− F4/80+ MHC-IIlo CD38+ CD206+ phenotype), while E0771 TT mostly contained CD11b+ monocytes (M2 CD11b+ cluster with a CD11c− F4/80− Ly6C+ phenotype). B6BC TT exhibited a more heterogeneous CD11b+ myeloid composition (figure 5C), split among M9 macrophages (35% of all CD11b+ cells) and a mixture of cells composed of MHC-II+ antigen presenting dendritic cells (M3 cells with a CD11c+ F4/80− MHC-II+ phenotype and M10 cells with a CD11chi F4/80− MHC-IIhi phenotype) and monocyte-like (M2 and M7 cells, the latter with a CD115/Csf1rint Arg1int phenotype) and granulocyte-like cells (M5 cells with an Ly6Cint Ly6Gint CD38+ phenotype), indicative of a greater myeloid cell diversity (figure 5C). This cell dominancy of TS/A and E0771 TT and co-dominancy of B6BC TT was also found in the minority myeloid population of CD11b− cells (online supplemental figure 5B–D). We also inspected the expression of CD115/Csf1r in leukocyte (CD45+) and non-leukocyte (CD45−) cell populations of B6BC, TS/A and E0771 TT (online supplemental figure 3). For all tumors, more than 50% of leukocytes were CD115/Csf1r+, while these cells only represented a minority (less than 10%) of CD45− cells. Consistently, inhibition of CSF1R signaling with the small molecule CSF1R tyrosine kinase inhibitor BLZ945 had only a mild impact in the proliferation of B6BC and E0771 cultured cells (online supplemental figure 5E,F).

Figure 5.

The myeloid immune-infiltrating compartment dominates the landscape of all murine BCs, but is exclusively immuno-modulable in B6BC TT. (A–C) Size-similar (0.5–1 cm2) freshly-dissociated cells from B6BC TT (n=6), TS/A TT (n=7) and E0771 TT (n=9) cell line-derived tumors were analyzed by multiparametric flow cytometry. (A) Normalized percentage of CD11b+ cells on total leukocytes (CD45+) for B6BC, TS/A and E0771 TT. Dots depict individual mice analyzed and the line shows average±SEM. (B) Opt-SNE projection of FlowSOM attributed cell clusters (M1 to M10, k-means=10) on total CD11b+ cells from B6BC TT (left), TS/A TT (middle) and E0771 TT (right) tumors together (left panel).The heatmap shows the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of each protein marker per cluster (right panel). The MFI color-code of each protein marker is condition per ‘all clusters’ (columns) expression. (C) Bar graph with the percentage of CD11b+ cells belonging to each cell cluster defined on (B) according to tumor type. Line shows average±SEM. Stats symbol comparisons: (*) B6BC TT versus TS/A TT; (#) B6BC TT versus E0771 TT and ($) TS/A TT versus E0771 TT. (D) Schedule for orthotopic implantation of B6BC TT, TS/A TT and E0771 TT cell line-derived tumors and treatment of established tumors with a monoclonal antibody blocking CD11b (200 µg/mouse of each, i.p., three times per week) or matched-isotype controls. Number of animals per treatment arm and cell line appeared on the figure. (E) Tumor growth response of established BCs to CD11b blocking. Graphs show tumor size average±SEM B6BC TT growth data from two individual experiments was pooled for graphical purposes. (F to L) Multiparametric flow cytometry analyses of tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells on isotype-treated or α-CD11b treated B6BC TT mouse tumors (n=8 and n=10, respectively), harvested at the end of the curves from (E). (F) Percentage of CD45+ CD11b+ or CD11b− cells on total living cells (Live/Dead negative) on isotype and α-CD11b treated tumors. Bar graphs show average±SEM. (G, J) Opt-SNE projection of FlowSOM attributed cell clusters on total CD11b+ cells (b+M1 to b+M20, k-means=20) (G) or on total CD11b− cells (b–M1 to b−M12, k-means=12) (J) by treatment (left panel) and heatmap of the level of expression of protein markers by each cluster (right panel). (H, K) Bar graph with the percentage of CD11b+ cells (H) or CD11b− cells (K) belonging to each cell cluster defined on (G, J) according to treatment arm. Line shows average±SEM. (I, L) Column graphs with the normalized number of cells per tumor weight in all cell clusters defined on (G, J). Dots depict individual mice analyzed and graph shows average±SEM. Statistical analysis was performed as follows: (A) Ordinary one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with multiple comparisons corrected with Tukey’s post hoc test, (E) using TumGrowth website in raw (pooled, for B6BC TT) data, (F) by unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction and (C,H,I,K,L) by two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons corrected with Tukey’s (C) or with Sidak’s post hoc test (H,I,K,L). (Adj) p value=*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. For (C, H, I, K, L) only significant p values are shown. Exact p values are indicated in the graphs or available in online supplemental table 3. BC, breast cancer; CL, cell lines; i.p., intraperitoneally; s.c., subcutaneously; TT, transplanted tumors.

In sum, B6BC TT seem to exhibit greater diversity within both CD11b+ and CD11b− tumor-infiltrating myeloid compartments, compared with the macrophage-dominance or monocyte-dominance of TS/A or E0771 TT, respectively.

Since CD11b+ cells were the most abundant tumor-infiltrating leukocyte population in all TT, we used a monoclonal antibody specific for CD11b to block the extravasation and integrin signaling of myeloid cells into established tumors (figure 5D, online supplemental figure 5G). Of note, only B6BC TT, but not TS/A TT, E0771 TT or MPA/DMBA-induced tumors diminished their natural growth on CD11b neutralization (figure 5E, online supplemental figure 5H). To dissect the impact of CD11b blocking on tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells, we performed multiparametric flow cytometry on endpoint tumors from B6BC TT-bearing mice treated with anti-CD11b or an isotype-matched antibody (figure 5D). Neutralization of CD11b did not reduce the percentage of CD11b+ cells, but drove a significant increase of the CD11b− population (figure 5F, online supplemental figure 5I). Within tumor-infiltrating CD11b+ cells, we clustered cells into 20 distinct b+M clusters (figure 5G). Only cluster b+M20 (with CD11c− F4/80+ MHC-IIint CCR2+ Cx3cr1− phenotype), corresponding to macrophages with intermediate levels of MHC-II and expressing the C-C chemokine receptor type 2 CCR2 involved in monocyte extravasation, significantly increased on anti-CD11b treatment according to two metrics: (i) the percentage of cells within the CD11b+ cluster and (ii) the absolute weight-normalized cell count (figure 5H1). Tumor-infiltrating CD11b− cells were clustered in 12 b−M clusters (figure 5J). Again only one cluster, b−M11 (with CD11c− F4/80hi CD115/Csf1r+ MHC-IIint CCR2− Cx3cr1hi phenotype), corresponding to macrophages with intermediate levels of MHC-II increased in both metrics on CD11b neutralization (figure 5K,L). Interestingly, while b−M11 cells were relatively negative for CCR2, they expressed high levels of CX3C motif chemokine receptor 1 (Cx3cr1) (figure 5K), characteristic of mammary intraepithelial or ductal macrophages.39 In contrast, b+M20 cells exhibited relative low levels of Cx3cr1 (figure 5G).

In conclusion, these results show a BC-infiltrating myeloid landscape dominated by macrophages in TS/A TT or monocytes in E0771 TT, which is not impacted by the neutralization of CD11b. In sharp contrast, blockade of CD11b reduces B6BC TT growth driving the emergence of macrophage populations (F4/80+) mostly distinguished by their differential surface cell levels of CD11b, MHC-II, CCR2 and Cx3cr1 (CD11b+ MHC-IIint CCR2+ Cx3cr1− vs CD11b− MHC-IIint CCR2− Cx3cr1+).

B6BC TT are enriched in pro-angiogenic Spp1+ myeloid cells compared with the diverse myeloid infiltrate of B6BC OT

To further dissect the heterogeneity of B6BC TT-infiltrating myeloid cells, we re-clustered the immune cells (cluster 2) of our snRNAseq data set for B6BC OT and B6BC TT (figure 3A–C). We defined 11 cell clusters (named 1–11) recovering known leukocyte cell types (figure 6A). Most of these clusters belonged exclusively to B6BC OT or to B6BC TT, indicating strong transcriptomic differences in cell diversity between tumors (figure 6B). The four largest clusters (1−4) corresponded to a mixture of myeloid cells expressing characteristic genes of monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells such as Itgam (encoding CD11b), Itgax (for CD11c) and C1q-coding genes (C1qa, C1qb and C1qc) (figure 6C). Other myeloid clusters were clusters 5 and 6 (composed of myeloid proliferating cells enriched in genes linked to proliferation such as Mki67) and cluster 10 (formed by neutrophils which expressed Csf3r), while lymphocytes (identified by Il2rb expression) were found in the low-abundant clusters 7 and 11 (figure 6B and C). In both tumor types, the four major myeloid clusters (1−4) constituted almost 80% of all leukocytes (figure 6D). However, while the immune landscape of B6BC TT was exclusively dominated by cluster 1, three myeloid populations (clusters 2−4) were highly abundant in B6BC OT, indicative of a greater myeloid diversity in the latter tumor (figure 6D).

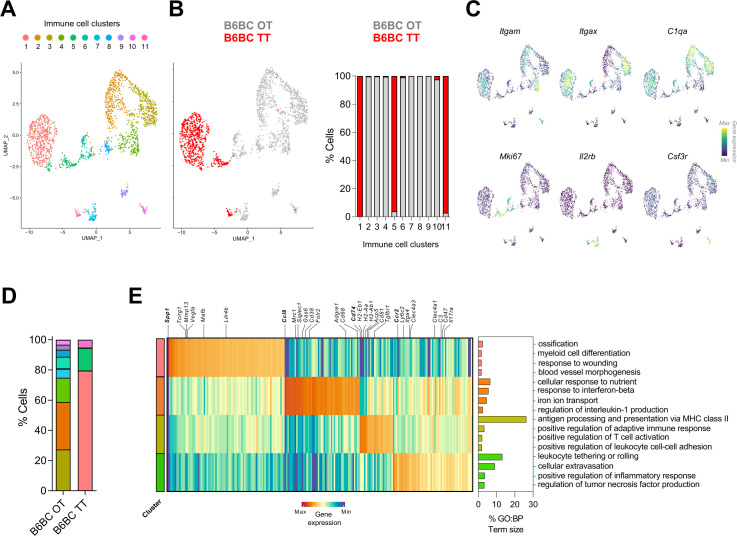

Figure 6.

Spp1 + myeloid cells dominate the immune landscape of B6BC TT in contrast to the myeloid diversity present in B6BC OT. (A). UMAP projecting the clusters with main immune cell identities (clusters 1–11) identified in the immune cell cluster (cluster 2, Ptprc + or CD45+) of all filtered merged cell nuclei subjected to single-nucleus RNA sequencing analysis from B6BC OT and B6BC TT (n=1 for each). (B) Same UMAP as in (A) color-coded by tumor type (B6BC OT in gray and B6BC TT in red) (left panel) and bar graphs showing the percentage of cells in each cluster belonging to each tumor type (right panel). (C) Density plots for the expression of lineage marker genes belonging to the main clusters identified on (A), for which UMAP projection is recovered. (D) Bar graph with the percentage of leukocytes belonging to each cell cluster defined on (A) according to tumor type. (E) Heatmap of main DEG (log2 fold change >0.5, (adj) p value<10−5) in immune cell clusters 1–4, comparing each individual cluster to the other three (left panel). GO biological process (BP) term analysis of the selected DEG of each cluster using g:Profiler (https://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/) (right panel). The bar graphs show the percentage of term size and are color-coded by the cluster they belong to. Only GO:BP terms with p value<0.05 were considered. BC, breast cancer; DEG, differential expressed genes; GO, Gene Ontology; OT, original tumor; TT, transplanted tumors.

To get deeper insights into the characteristics of such myeloid clusters, we selected the top upregulated genes for each cluster (compared to the other three), followed by GO term analysis (figure 6E, online supplemental table 2). Cluster 1 appeared to be composed by a mixture of myeloid cells with moderate expression of Itgax and C1q-coding genes. Of note, these cells strongly expressed Spp1, a widely described marker of pro-angiogenic tumor-associated macrophages (TAM)13 40–42 as well as Vegfa, and to a lower extent Lilr4b, a gene expressed by type 2 conventional dendritic cells (cDC2).41 Altogether, genes upregulated in cluster 1 were linked to myeloid cell differentiation, blood vessel morphogenesis, response to wounding and ossification (figure 6E).

jitc-2023-007117supp004.xlsx (360.1KB, xlsx)

Cells in cluster 2 upregulated typical lineage macrophage markers (like Adgre1 coding for F4/80 or Cd68) and TAM-associated genes such as Folr2, Mrc1 (coding for CD206) and Cd38.43 44 Importantly, these cells also expressed Siglec1 and Ccl8, previously associated to a protumorigenic TAM–BC crosstalk in humans.45 Consistently, GO term analysis revealed the implication of pathways related to cellular response to nutrient and iron ion transport, response to interferon-β and regulation of interleukin-1 (figure 6E), suggestive of an anti-inflammatory phenotype.43 In contrast, cluster 3 was enriched in genes related to antigen presentation (AP) via MHC-II (ie, Cd74, H2-Eb1, H2-AA or Ctss), and expressed markers of both macrophages (C1q-coding genes) and dendritic cells (DCs) (ie, Itgax or Axl).41 Accordingly, GO term analysis pointed to AP via MHC-II, positive regulation of T-cell activation and adaptive immune response (figure 6E). Finally, cluster 4 expressed lineage markers corresponding to monocytes (ie, Ccr2 and Ly6C2) and monocyte (mo)-derived cells such as mo-DCs, which share some markers with cDC2 (Clec4a3 and Clec4a1).41 In line with this interpretation, cluster 4-associated GO terms included leukocyte rolling and extravasation and positive regulation of inflammatory response (figure 6E).

Altogether, B6BC TT presented a reduced transcriptomic diversity of tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells compared with B6BC OT. The myeloid landscape of B6BC OT was notably composed of anti-inflammatory TAMs, AP cells expressing macrophage or DC lineage markers and pro-inflammatory monocytes or mo-DCs. This differs from B6BC TT cancers, in which a sole Spp1 + myeloid population associated with angiogenesis dominated the tumor immune microenvironment.

Discussion

HR+ BC has been particularly difficult to model in mice, perhaps explaining the lack of transplantable CL derived from the most common mouse inbred strain C57BL/6, which is most frequently used in (immuno)genetic studies. This is a major limitation for the study of HR+ BC-relevant (immuno)mechanisms.

In this report, we describe the generation of the first HR+ BC cell line transplantable to C57BL/6 mice, B6BC. We characterized B6BC cells and tumors at the molecular and immunological levels, comparing them to two well-defined models of ER+ BC (the MPA/DMBA-induced C57BL/6 model from which the B6BC cell line was derived, and the transplantable ER+ TS/A BALB/C cell line), as well as to two common TNBC C57BL/6 CL (AT-3 and E0771) in a setting of non-resectable locally advanced disease. Despite a recent report claiming luminal characteristics of E0771 tumors,46 47 E0771 cells only expressed ERβ (coding for Esr2), but not the HR+ BC-relevant subunit ERα (Esr1) and give rise to ERα− tumors on inoculation into mammary fat pads.22 We found that B6BC cells were ER+ PR+ and sensitive to both ER and PR antagonists. Once inoculated into the mammary fat pads from C57BL/6 mice, established B6BC TT cell line-derived tumors remained ER+ (although they lost PR expression) and reduced their growth on treatment with the ER antagonists tamoxifen and fulvestrant. Although overall animal survival was increased, these interventions did not lead to complete pathological responses, as previously reported for ER+ MPA/DMBA-induced tumors,17 indicating the need for more specific/early interventions or combinatorial approaches to eradicate such tumors. It is important to note that CDK4/6 inhibitors have some preclinical effects against MPA/DMBA tumors,48 suggesting that they should be tested against BCBC TT, knowing that B6BC cells respond to CDK4/6 inhibitors in vitro. Altogether, B6BC TT and MPA/DMBA tumors may be useful for the study of ER– and CDK4/6-modulable HR+ BC. Concerning HER2/ERBB2 expression and signaling, although B6BC, TS/A and E0771 cells expressed detectable levels of Erbb2 protein,46 47 they did not require Erbb2 signaling to proliferate in vitro, thus differing from BT-474 human BC cells, which overexpress ERBB2 and were sensitive to the ERBB2 inhibitor lapatinib.

With respect to the cancer cell compartment, invasive B6BC TT were composed of spindle-shaped cells enriched in EMT features compared with BC cells from the B6BC OT MPA/DMBA tumor they derived from. Acquisition of an EMT phenotype by cancer cells is frequently observed in claudin-low BC tumors and has been associated with tumor progression and metastasis.36 Of note, claudin gene transcripts were almost totally absent from B6BC TT compared with B6BC OT, suggesting that B6BC TT present a cancer cell-intrinsic claudin-low phenotype. Further studies will be necessary to address the impact of such features in the context of early-localized and metastatic disease.

Regarding the tumor immune microenvironment, ER+ TS/A TT appeared more infiltrated by T cells, notably CD8+ T cells, than TNBC E0771 TT and ER+ B6BC TT, the latter one showing a particularly low T-cell infiltrate. TNBC E0771 exhibited the highest proportion of regulatory T cells among all tumor types; and these cells expressed relatively high levels of the immune checkpoint protein PD-1. Depletion of T cells accelerated the growth of TS/A TT and affected the response of TS/A TT to ICD-inducing chemotherapy, yet failed to influence the spontaneous or chemotherapy-reduced proliferation of B6BC TT. Thus, TS/A TT resemble highly TIL infiltrated and T-cell immunomodulable ER+ human tumors, while B6BC TT mimic poorly TIL infiltrated, T-cell irresponsive ER+ BC.49

Regarding T-cell immunotherapeutic responses, neither poorly T cell-infiltrated ER+ B6BC nor the highly T cell-infiltrated TS/A TT responded to immune checkpoint blockade with anti-PD-1, thus behaving similarly to ER+ MPA/DMBA induced tumors.17 In sharp contrast, TNBC E0771 TT responded to PD-1 blockade in spite of the fact that E0771 TT contained similar levels of PD-1+ T cells over total living cells as non-responder TS/A TT. Thus, the levels of TILs or the percentage of PD-1+ T cells over total living cells were not associated with anti-PD-1 response outcomes in TS/A compared with E0771 TT. However, the percentage of PD1+ cells among CD3+ T cells was higher in E0771 TT than in TS/A TT and B6BC TT and hence may be a better predictor of the response to PD-1 blockade in these mouse models. In conclusion, B6BC TT, TS/A TT and MPA/DMBA induced tumors exemplify HR+ BC resistant to PD-1 targeted immunotherapy, contrasting with the immunotherapy sensitive E0771 TT.12

Consistent with previous studies in other mouse BC models,12 all murine tumors presented higher proportions of myeloid infiltrating cells over lymphocytes in the immune microenvironment. As previously reported, E0771 TT were enriched in CD11b+ monocytes, while all ER+ BC (TS/A TT, B6BC TT and B6BC OT for MPA/DMBA tumors) appeared to be dominated by macrophage infiltration. In particular, B6BC TT were infiltrated by a phenotypically heterogeneous population of myeloid cells that were homogenously expressing high levels of Spp1. Of note, Spp1+ have been identified in human BC and linked to angiogenesis in this and other cancer types.13 40 This contrasts with B6BC OT, in which three different myeloid populations consisting in tumor associated macrophages expressing Folr2, Mrc1 and Cd38, antigen presenting cells and extravasated monocytes coexisted in the tumor microenvironment. From a therapeutic point of view, approaches targeting the myeloid tumor compartment are so far under-represented50 and only a few such as targeting CSF1R have shown clinical efficacy,10 while other newly identified targets are currently undergoing clinical trials.51

Here, we demonstrate that CD11b blockade moderately reduced the growth of B6BC TT but not TS/A TT, E0771 TT or MPA/DMBA tumors. In B6BC TT, neutralization of CD11b favored the emergence of otherwise scarcely present populations of macrophages (F4/80+/hi) expressing the monocyte marker CCR2 (CD11b+ CCR2+), which may be indicative of their prior tissue recruitment and extravasation, or expressing Cx3cr1 (CD11b− Cx3cr1hi), a phenotype recently reported for mammary intraepithelial or ductal macrophages that are depleted in other BC mouse models when tumors progress.39 These cells also express different levels of MHC-II, which may be indicative of AP to the few lymphocytes present in the tumor bed. CD11b reportedly modulates tumor growth by affecting pro-angiogenic macrophage polarization, AP via MHC-II and T-cell activation, but also CCL2 (a ligand for CCR2)-dependent monocyte recruitment.52 Of note, other experimentally tested myeloid-targeting strategies may increase the number of MHC-II+ macrophages as a correlate of improved immune control.51 53 Thus, B6BC TT cell line-derived tumors might be a good model for testing novel approaches for targeting tumor infiltrating myeloid cells, notably in the context of abundant infiltration by Spp1+ .

Altogether, in this study we provide a complete molecular and immunological characterization of the first C57BL/6-compatible transplantable HR+ BC, B6BC, which appears a promising tool for the study of lymphocyte-cold, myeloid-rich, PD-1 resistant HR+ BC. It will be a welcome challenge to develop effective therapies against B6BC TT, which, in the context of locally advanced BC—in our hands—thus far has remained incurable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Laurence Zitvogel (Institut Gustave Roussy, Paris), Dr Clothilde Thery (Institut Curie, Paris) and the cell culture facility of CEINGE-Biotecnologie Avanzate s.c.a.r.l. (Naples, Italy) for kindly providing murine and human breast cancer cell lines. We are grateful to Kevin Garbin and Oumar Maiga from the CHIC platform at Centre de Recherche de Cordeliers and to Olivia Bawa from the PETRA platform at Institut Gustave Roussy for their help with histological sample processing and stainings. We also thank Dr Aurelien de Reynes for providing help with snRNAseq analyses.

Footnotes

Twitter: @plaurentpuig

Contributors: MP-L performed most in vivo and in vitro experiments and analyzed most of the data. VC performed informatics analyses of snRNAseq. PC carried out histological analyses. FDEDP and AP helped with in vitro and in vivo experiments. CK performed image acquisition of whole slides histological samples and helped with histology data analyses. KM and FA processed histological samples and set up and performed most histology stainings. SM-R, DLC, WX and MS helped with snRNAseq sample, library preparation and sequencing alignment. IM carried out image flow cytometry. JPa, HFT and JPo provided help with flow cytometry experiments and analyses. GS helped with statistical analyses. MCM, GK, JPo, CD and PL-P supervised the study. MP-L, CL-O, MCM and GK wrote the manuscript. MP-L, MCM and GK conceived the study. Critical revision of the manuscript: All authors. GK is the guarantor of the study.

Funding: GK is supported by the Ligue contre le Cancer (équipe labellisée); Agence National de la Recherche (ANR)—Projets blancs; AMMICa US23/CNRS UMS3655; Association pour la recherche sur le cancer (ARC); Cancéropôle Ile-de-France; Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM); a donation by Elior; Equipex Onco-Pheno-Screen; European Joint Programme on Rare Diseases (EJPRD); European Research Council Advanced Investigator Award (ERC-2021-ADG, ICD-Cancer, Grant No. 101052444), European Union Horizon 2020 Projects Oncobiome and Crimson; Fondation Carrefour; Institut National du Cancer (INCa); Institut Universitaire de France; LabEx Immuno-Oncology (ANR-18-IDEX-0001); a Cancer Research ASPIRE Award from the Mark Foundation; the RHU Immunolife; Seerave Foundation; SIRIC Stratified Oncology Cell DNA Repair and Tumor Immune Elimination (SOCRATE); and SIRIC Cancer Research and Personalized Medicine (CARPEM). This study contributes to the IdEx Université de Paris ANR-18-IDEX-0001. PC is a recipient of Plan Cancer INSERM (programme « Soutien pour la formation à la recherche fondamentale et translationnelle en cancérologie »).

Competing interests: GK has been holding research contracts with Daiichi Sankyo, Eleor, Kaleido, Lytix Pharma, PharmaMar, Osasuna Therapeutics, Samsara Therapeutics, Sanofi, Tollys, and Vascage. GK has been consulting for Reithera. GK is on the Board of Directors of the Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation France. GK is a scientific co-founder of everImmune, Osasuna Therapeutics, Samsara Therapeutics and Therafast Bio. GK is in the scientific advisory boards of Hevolution, Institut Servier and Longevity Vision Funds. GK is the inventor of patents covering therapeutic targeting of aging, cancer, cystic fibrosis and metabolic disorders. FDEDP, GK, JPo and MCM are listed as co-inventors on an international patent (‘Methods for diagnosing, prognosing and managing treatment of BC’; WO 2021/170777 A1). GK’s wife, Laurence Zitvogel, has held research contracts with GlaxoSmithKline, Incyte, Lytix, Kaleido, Innovate Pharma, Daiichi Sankyo, Pilege, Merus, Transgene, 9 m, Tusk and Roche, was on the Board of Directors of Transgene, is a cofounder of everImmune, and holds patents covering the treatment of cancer and the therapeutic manipulation of the microbiota. GK’s brother, Romano Kroemer, was an employee of Sanofi and now consults for Boehringer-Ingelheim. The other coauthors declare no conflict of interest.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Miller KD, et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin 2022;72:524–41. 10.3322/caac.21754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harbeck N, Penault-Llorca F, Cortes J, et al. Breast cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019;5:66. 10.1038/s41572-019-0111-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pfeiffer RM, Webb-Vargas Y, Wheeler W, et al. Trends in breast cancer incidence attributable to long-term changes in risk factor distributions. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2018;27:1214–22. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kroemer G, Senovilla L, Galluzzi L, et al. Natural and therapy-induced Immunosurveillance in breast cancer. Nat Med 2015;21:1128–38. 10.1038/nm.3944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Denkert C, von Minckwitz G, Darb-Esfahani S, et al. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis in different subtypes of breast cancer: a pooled analysis of 3771 patients treated with Neoadjuvant therapy. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:40–50. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30904-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Denkert C, Loibl S, Noske A, et al. Tumor-associated lymphocytes as an independent Predictor of response to Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. JCO 2010;28:105–13. 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.7370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cortes J, Cescon DW, Rugo HS, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-355): a randomised. Lancet 2020;396:1817–28. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32531-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schmid P, Cortes J, Dent R, et al. Vp7-2021: KEYNOTE-522: phase III study of Neoadjuvant Pembrolizumab + chemotherapy vs. placebo + chemotherapy, followed by adjuvant Pembrolizumab vs. placebo for early-stage TNBC. Annals of Oncology 2021;32:1198–200. 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.06.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abdou Y, Goudarzi A, Yu JX, et al. Immunotherapy in triple negative breast cancer: beyond checkpoint inhibitors. Npj Breast Cancer 2022;8. 10.1038/s41523-022-00486-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goldberg J, Pastorello RG, Vallius T, et al. The Immunology of hormone receptor positive breast cancer. Front Immunol 2021;12:1515. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.674192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Terranova-Barberio M, Pawlowska N, Dhawan M, et al. Exhausted T cell signature predicts Immunotherapy response in ER-positive breast cancer. Nat Commun 2020;11:3584. 10.1038/s41467-020-17414-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim IS, Gao Y, Welte T, et al. Immuno-Subtyping of breast cancer reveals distinct myeloid cell profiles and Immunotherapy resistance mechanisms. Nat Cell Biol 2019;21:1113–26. 10.1038/s41556-019-0373-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cheng S, Li Z, Gao R, et al. A Pan-cancer single-cell transcriptional Atlas of tumor infiltrating myeloid cells. Cell 2021;184:792–809. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Özdemir BC, Sflomos G, Brisken C. The challenges of modeling hormone receptor-positive breast cancer in mice. Endocrine-Related Cancer 2018;25:R319–30. 10.1530/ERC-18-0063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zitvogel L, Pitt JM, Daillère R, et al. Mouse models in Oncoimmunology. Nat Rev Cancer 2016;16:759–73. 10.1038/nrc.2016.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kersten K, de Visser KE, van Miltenburg MH, et al. Genetically engineered mouse models in oncology research and cancer medicine. EMBO Mol Med 2017;9:137–53. 10.15252/emmm.201606857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buqué A, Bloy N, Perez-Lanzón M, et al. Immunoprophylactic and Immunotherapeutic control of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Nat Commun 2020;11:1–18. 10.1038/s41467-020-17644-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Buqué A, Perez-Lanzón M, Petroni G, et al. MPA/DMBA-driven Mammary Carcinomas. Methods Cell Biol 2021;163:1–19. 10.1016/bs.mcb.2020.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fougner C, Bergholtz H, Kuiper R, et al. Claudin-low-like mouse Mammary tumors show distinct Transcriptomic patterns Uncoupled from Genomic drivers. Breast Cancer Res 2019;21:85. 10.1186/s13058-019-1170-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brayton CF, Treuting PM, Ward JM. Pathobiology of aging mice and GEM: background strains and experimental design. Vet Pathol 2012;49:85–105. 10.1177/0300985811430696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nanni P, de Giovanni C, Lollini PL, et al. TS/A: a new Metastasizing cell line from a BALB/C spontaneous Mammary adenocarcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis 1983;1:373–80. 10.1007/BF00121199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johnstone CN, Smith YE, Cao Y, et al. Functional and molecular Characterisation of Eo771.LMB tumours, a new C57Bl/6-mouse-derived model of spontaneously metastatic Mammary cancer. Disease Models & Mechanisms 2015;8:237–51. 10.1242/dmm.017830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stewart TJ, Abrams SI. Altered immune function during long-term host-tumor interactions can be modulated to retard autochthonous neoplastic growth. J Immunol 2007;179:2851–9. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.2851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Slyper M, Porter CBM, Ashenberg O, et al. Author correction: A single-cell and single-nucleus RNA-Seq Toolbox for fresh and frozen human tumors. Nat Med 2020;26:1307. 10.1038/s41591-020-0976-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]