Abstract

Objectives

Various organic acids are used to create nicotine salt formulations, which may improve the appeal and sensory experience of vaping electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes). This clinical experiment examined the effects of partially and highly protonated forms of two nicotine salt formulations (nicotine lactate and benzoate) vs. free-base (no acid additive) on the appeal and sensory attributes of e-cigarettes.

Methods

Current adult tobacco product users (N=116) participated in an online remote double-blind within-subject randomized experiment involving standardized self-administration of e-cigarette solutions varying in nicotine formulation (free-base, 50% nicotine lactate [1:2 lactic acid to nicotine molar ratio], 100% nicotine lactate [1:1 ratio], 50% nicotine benzoate, and 100% nicotine benzoate). Each formulation had equivalent nicotine concentrations (27.0–33.0 mg/mL) and was administered in 4 flavors in a pod-style device. After each administration, participants rated appeal (liking, disliking, willingness to use again) and sensory attributes (0–100 scale).

Results

Compared to free-base nicotine, 50% and 100% nicotine lactate and benzoate yielded higher appeal, smoothness, and sweetness and lower harshness and bitterness. Dose-response analyses found 100% vs. 50% nicotine salt improved appeal, smoothness, bitterness, and harshness for nicotine lactate and sweetness, smoothness, and harshness for nicotine benzoate. Solutions with higher pH were associated with worse appeal and sensory attributes across nicotine formulations. Nicotine formulation effects did not differ by tobacco use status and flavors.

Conclusion

Restricting benzoic or lactic acid additives or setting minimal pHs in e-cigarettes merit consideration in regulations designed to reduce vaping among populations deterred from using e-cigarettes with aversive sensory properties.

Keywords: nicotine salt, acid additives, dose-response, flavor, appeal, sensory attribute

INTRODUCTION

Free-base nicotine has aversive sensory effects (e.g., bitterness, airway irritation) when inhaled in e-cigarette aerosol, and these effects increase at higher nicotine concentrations.[1,2] Adding organic acids to e-cigarettes changes free-base nicotine to a protonated salt formulation, which may offset nicotine’s aversive sensory effects.[2] Although benzoic acid has been shown to improve e-cigarette sensory experience and appeal,[3] benzoic is just one of six common acid additives used in nicotine salt e-cigarettes.[4,5] Analyses of U.S.A. and Dutch e-cigarette solutions have found that lactic acid was the most commonly acid detected in marketed nicotine salt formulations.[4,5] It is unknown whether the effect of nicotine protonation on the sensory experience and appeal of e-cigarettes generalizes across lactic and benzoic acid. Addressing this question can inform whether regulatory policies should target one or multiple types of acid additives.

It is also important to consider the ratio of protonated vs. free-base nicotine used in solutions. E-cigarette nicotine salt solutions are often produced by mixing a 1:1 molar ratio of acid additives to free-base nicotine,[6] generating solutions with over 95% protonated nicotine.[7] Some products are made with lower molar ratios of acid to free-base nicotine,[6] resulting in solutions that partially contain protonated nicotine and partially contain free-base nicotine. It is unknown if there is a ‘dose-respons’ effect of nicotine protonation in which fully protonated (e.g., 1:1 molar ratio) incrementally improves product appeal and sensory attributes beyond partially protonated (e.g., 1:2 molar ratio) solutions. Evidence of a dose-response association could provide regulatory agencies with information toward identifying thresholds of nicotine protonation to set allowable limits.

Alternatively, pH might be a practical regulatory target for e-cigarettes.[8] The molar ratio of acid and free-base nicotine may not always correspond to nicotine protonation level of an e-cigarette solution because flavorings and other constituents might alter the protonation process. Instead, pH may be a more generalizable indicator of nicotine protonation in e-cigarette solutions.[9–11] Hence, secondary correlational evidence that products with lower pHs are associated with improved sensory experience and product appeal could point to minimal pH as a parsimonious and practical target for regulatory policy.

Finally, the generalizability of nicotine formulation effects on appeal and sensory attributes across tobacco product use status and flavor are important to consider. If nicotine salt formulations improve product appeal more in smokers than non-smokers, then regulatory restrictions on nicotine salt might dissuade smokers from switching to vaping. Also, if nicotine salt formulations improve product appeal only for particular flavors, then regulatory policies targeting nicotine salt may not necessarily need to extend across all flavors.

The primary aim of this clinical experiment was to examine the dose-response effects of partially and highly protonated forms of nicotine lactate and benzoate (vs. free-base nicotine) on the appeal and sensory attributes of e-cigarettes in adult nicotine product users. As secondary aim, we examined the association of pH of the products with appeal and sensory attributes. As tertiary aim, we examined generalizability across by tobacco product use status and flavor.

METHODS

Participants

Participants across the U.S.A. were recruited via internet (May-November 2021). Inclusion criteria were: ≥21 years old, access to an Internet connection, device, and quiet location for Zoom visits, and either current combustible cigarette smoking with interest in trying e-cigarettes (≥4 cigarettes/day for ≥2 years) or current nicotine vaping (vape ≥3 days/week for ≥2 months).[3] Current cigarette smokers who used e-cigarettes (i.e., dual users) were eligible. Exclusion criteria were: planning to cut down or quit vaping/smoking; pregnant/breastfeeding; cardiovascular or lung disease; recent COVID-19 illness/exposure; and daily use of other nicotine/tobacco products. Participants provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board and followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline for clinical trials.[12]

Design and Materials

As in prior work,[3,13,14] a single-day within-subject design e-cigarette appeal rating protocol was used. This protocol reduces participant and staff burden and prevents sampling biases stemming from attrition that often occurs in multi-visit experiments. Participants rated appeal and sensory attributes of custom manufactured e-cigarette solutions (Molecule Labs, Benicia, CA, U.S.A) in 5 different nicotine formulations-each representing a different within-subject condition: (1) free-base (no acid), (2) 50% nicotine lactate (1:2 lactic acid to nicotine molar ratio), (3) 100% nicotine lactate (1:1 lactic acid to nicotine), (4) 50% nicotine benzoate (1:2 benzoic acid to nicotine), and (5) 100% nicotine benzoate (1:1 benzoic acid to nicotine). Each nicotine formulation was administered in 4 flavors: bold tobacco, caramel, grape-menthol, and strawberry. Besides the addition of the benzoic or lactic acid, the constituents in each flavor’s e-cigarette solution were identical. There was a total of 20 solutions administered in a randomized order for each participant. Nicotine concentration, density, propylene glycol/vegetable glycerin (PG/VG) vehicle, and pH tests for each solution were conducted by the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center Nicotine and Tobacco Product Assessment Core. Each e-liquid was administered via a pod-based-style e-cigarette device (Avatar Go; 114 mm height; 19 mm width; 10.5 mm thickness; 3.7 Vdc lithium polymer battery input; 350 mAh battery; 30W output max) with refillable pod cartridge inserts.

Procedure

After a phone eligibility screen, participants attended a Zoom orientation visit involving informed consent, eligibility confirmation, and postal address for shipping study materials needed. Participants were instructed to abstain from nicotine product use for 2 hours prior to the experimental session. We then shipped the e-cigarette device and 20 pre-filled e-liquids (labeled 1–20), signifying the participant’s respective randomized order of e-cigarette solutions that they were to administer during the experimental session. Staff who administered the experimental sessions were blind to order.

At experimental session outset, staff verified (via visual inspection of video feed) that the shipping box was still sealed and each pod’s “tamper” tape was unadulterated to continue. Participants were explained the two-puff controlled puffing procedure they were to follow for each of the 20 exposure trials. During each trial, a video was replayed, which directed participants in real time to take two standardized puff sequences. Each puff sequence had a 10-second preparation interval, 4-second inhalation, 1-second hold, and 2-second exhale interval. After the completion of each two-puff trial, participants could take as much time as needed to complete appeal and sensory ratings of the e-liquid they just vaped on digital surveys. After each trial’s ratings, participants drank water and spent time as much as they needed to prepare for the next 2-puff trial. The overall procedure was separated into four, 5-trial blocks, with 10-minute inter-block intervals involving no vaping when participants completed demographic and tobacco product use questionnaires. Within each block, one trial was completed approximately every 8–10 minutes. The entire visit lasted approximately 4 hours. Staff instructed participants step-by-step as they completed each procedure via video chat in real time and corrected any deviations. Staff verified participants’ compliance via direct real time video observation on Zoom and session video tapes were later check for quality control by a project manager. Once the experiment session was completed, participants disposed of the device and pods.

Measures

Appeal.

Participants completed 3 visual analogue scale (VAS, range: 0–100) ratings of each product [“How much did you like the e-cigarette?” (liking); “How much did you dislike the e-cigarette?” (disliking); “Would you use it again?” (willingness to use again)]. Rating anchors were ‘not at all’ to ‘extremely’, except for willingness to use again (‘not at all’ to ‘definitely’).

Sensory ratings.

Participants also rated four sensory attributes: “how sweet was the e-cigarette?”; (2) smooth?; (3) bitter?; and (4) harsh? (VAS with 0–100 range anchored at ‘not at all’ and ‘extremely’).

Participant characteristics.

Self-report current combustible cigarette smoking (≥4 cigarettes/day for ≥2 years) and nicotine vaping (vape ≥3 days/week for ≥2 months) was recoded into a trichotomous tobacco use status variable (exclusive smoker vs. exclusive vaper vs. dual user). Among exclusive vapers and dual users, we assessed number of days vaped in the past 30 days, times vaped per vaping day, puffs per vaping episode; device type currently used; flavor used most frequently; and nicotine formulation currently used in participants’ own e-cigarettes. For exclusive smokers and dual users, we assessed number of days smoked in the past 30 days, number of cigarettes smoked per smoking day, and usual use of menthol cigarettes (yes/no). Sociodemographic characteristics for all respondents included self-reported age, gender identity, sexual identity, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, and employment status (see Table 1 for details).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics, Stratified by Tobacco Use Status

| Variables | Total (N = 116) | Exclusive Smoker (n = 31) | Exclusive Vaper (n = 26) | Dual user (n = 59) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age, M (SD) | 37.5 (13.5) | 43.1 (12.8) | 30.0 (13.0) | 37.9 (12.7) |

| Gender identity, N (%) | ||||

| Cisgender Man | 53 (46.1) | 17 (54.8) | 13 (50.0) | 23 (39.7) |

| Cisgender Woman | 56 (48.7) | 14 (45.2) | 11 (42.3) | 31 (53.4) |

| Another gendera | 6 (5.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.7) | 4 (6.9) |

| Sexual identity, N (%) | ||||

| Straight/heterosexual | 84 (73.7) | 24 (77.4) | 20 (80.0) | 40 (69.0) |

| Another sexual identityb | 30 (26.3) | 7 (22.6) | 5 (20.0) | 18 (31.0) |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 77 (67.0) | 23 (74.2) | 19 (73.1) | 35 (60.3) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 16 (13.9) | 3 (9.7) | 3 (11.5) | 10 (17.2) |

| Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin | 8 (7.0) | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (10.3) |

| Another race/ethnicityc | 14 (12.2) | 3 (9.7) | 4 (15.4) | 7 (12.1) |

| Educational attainment, N (%) | ||||

| High school diploma/GED or less | 28 (24.3) | 7 (22.6) | 6 (23.1) | 15 (25.9) |

| Some college completed or currently enrolled | 35 (30.4) | 9 (29.0) | 9 (34.6) | 17 (29.3) |

| College degree or higher | 52 (45.2) | 15 (48.4) | 11 (42.3) | 26 (44.8) |

| Employment status, N (%) | ||||

| Full-time | 35 (30.7) | 11 (35.5) | 8 (30.8) | 16 (28.1) |

| Part-time | 24 (21.1) | 8 (25.8) | 5 (19.2) | 11 (19.3) |

| Unemployed | 26 (22.8) | 4 (12.9) | 7 (26.9) | 15 (26.3) |

| Another employment statusd | 29 (25.4) | 8 (25.8) | 6 (23.1) | 15 (26.3) |

| Combustible cigarette use characteristics e | ||||

| No. of days smoked in past 30 days, M (SD) | 23.0 (10.9) | 28.7 (3.9) | - | 20.0 (12.2) |

| No. of cigarettes smoked per day, M (SD) | 10.7 (7.3) | 12.9 (5.8) | - | 9.5 (7.8) |

| Usually smokes menthol cigarettes, N (%) | 38 (43.7) | 10 (33.3) | - | 28 (49.1) |

| E-cigarette use characteristics f | ||||

| No. of days vaped in past 30 days, M (SD) | 23.5 (8.4) | - | 27.9 (3.5) | 21.4 (9.1) |

| No. of times vaped per day, M (SD) | 12.9 (7.3) | - | 16.3 (5.8) | 11.1 (7.4) |

| No. of puffs per vaping episode, M (SD) | 5.5 (5.2) | - | 5.8 (6.3) | 5.4 (4.7) |

| E-cigarette device type currently use g , N (%) | ||||

| Refillable, rechargeable deviceh | 39 (33.6) | - | 9 (49.2) | 30 (65.4) |

| Disposable device | 32 (26.7) | - | 12 (46.2) | 20 (33.9) |

| Juul | 24 (20.7) | - | 5 (19.2) | 19 (32.2) |

| Other pod device | 16 (18.8) | - | 7 (26.9) | 9 (15.3) |

| Another device | 3 (2.6) | - | 2 (7.7) | 1 (1.7) |

| E-cigarette flavor used most often, N (%) | ||||

| Tobacco | 12 (14.3) | - | 1 (3.8) | 11 (19.0) |

| Menthol/mint | 20 (23.8) | - | 6 (23.1) | 14 (24.1) |

| Fruit | 34 (40.5) | - | 14 (53.8) | 20 (34.5) |

| Icei | 12 (14.3) | - | 4 (15.4) | 8 (13.8) |

| Another flavorj | 6 (7.1) | - | 1 (3.8) | 5 (8.6) |

| Type of current nicotine formulation f , N (%) | ||||

| Nicotine Salt | 30 (35.7) | - | 12 (46.2) | 18 (31.0) |

| Nicotine free-base | 12 (14.3) | - | 7 (26.9) | 5 (8.6) |

| Switch back and forth between salt and free-base | 5 (6.0) | - | 1 (3.8) | 4 (6.9) |

| Do not know | 37 (44.0) | - | 6 (23.1) | 31 (53.4) |

Note. Frequencies may not sum to the total due to different patterns of missing data across variables. Exclusive vapers = vape ≥3 days/week for ≥2 months; exclusive cigarette smokers = ≥4 cigarettes/day for ≥2 years; dual users = dual users of e-cigarettes and cigarettes.

Transgender man/woman, non-binary/genderqueer, or something else.

Asexual (n=1), bisexual (n=12), gay (n=4), lesbian (n=1), pansexual (n=4), queer (n=4), questioning/unsure (n=1), or something else (n=3).

Alaska Native, American Indian, Asian or Pacific Islander, or multi-racial.

Retired/disability, summer only, student only, or student with full or part-time job.

Includes current exclusive smokers (n=31) and dual users (n=59).

Includes current exclusive vapers (n=26) and dual users (n=59).

Each device type was measured as binary variable (yes/no). Multiple response was allowed.

Tank system, canister system, vape pen or pen-like rechargeable device, mod or mech-mod rechargeable device, box mod.

Ice-flavor indicates a combination of fruit/sweet and cooling flavors (e.g., blueberry ice).

Unfavored, alcohol, clove, spice, dessert, or other sweets.

Statistical Analysis

Primary aim: Nicotine formulation.

After descriptive analyses of the study sample and e-cigarette solution constituents, we used multilevel linear modeling (MLM) to test the fixed effects of nicotine formulation on sensory and appeal ratings accounting for nesting of trials within participants. Ratings from each trial were analyzed as separate data points (20 per participant). Independent separate MLMs were tested for each outcome. To examine dose-response effects of nicotine lactate and benzoate salt separate from one another, we ran two MLM model sets: (a) MLMs testing the trichotomous dose-response nicotine benzoate independent variable (100% free-base, 50% nicotine benzoate, 100% nicotine benzoate), (b) MLMs testing the trichotomous dose-response nicotine lactate independent variable (100% free-base vs. 50% nicotine lactate vs. 100% nicotine lactate).

Secondary aim: pH effects.

We used each e-cigarette solution’s respective pH level as values in a continuous pH variable. We first fit MLMs using all 20 solutions testing the association of pH with each appeal and sensory rating controlling for flavor, testing both the linear and quadratic effects of pH. Next, to determine whether the association of pH with study outcomes generalized across nicotine benzoate and nicotine lactate solutions, we conducted a supplementary analysis excluding ratings of the 4 free-base solution conditions for each participant. Using data from the remaining 16 solutions with either partially or highly protonated nicotine, we examined whether the association of pH with study outcomes differed between the 8 nicotine benzoate solutions and the 8 nicotine lactate solutions by testing pH × acid type interactions

Tertiary aim: Generalizability of nicotine formulation effects across tobacco use status and flavor.

We tested the interaction effects of nicotine formulation with tobacco product use status (exclusive vapers, exclusive smokers, or dual users) and flavor (tobacco, caramel, grape-menthol, or strawberry) on outcomes to examine differential effects

Sensitivity analyses.

To determine if pre-existing preferences for nicotine salt solutions biased the primary aim results, we tested if study nicotine formulation condition effects differed depending on the nicotine formulation used in participants’ own e-cigarettes (condition × preferred nicotine formulation). To determine if PG/VG ratio variation across nicotine formulation conditions might have confounded the primary analyses, we retested the models controlling for the study e-liquids’ respective PG/VG ratio.

Results reflect unstandardized effect estimates (B) with standard errors (SE). MLMs utilized all available data for study participants with ≥1 observations. Eleven participants have partial trial-level missing data (range, 1–19 trials). Data were complete for all 20 trials in the remainder of the sample. Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple testing was used to control the false-discovery rate at 0.05.[15] Analyses were performed in R version 4.2.0 lme4 package.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Depicted in Table 1, the sample [age, M(SD) = 37.5(13.5) years] was socio-demographically diverse. Of the 116 participants (see flowchart in Supplement Figure S1), 50% were current dual cigarettes+e-cigarette users (50.9%), 26.7% were exclusive cigarette smokers, and 22.4% were exclusive vapers. Exclusive smokers reported smoking, on average, on 28.7(SD=3.9) of the past 30 days and 12.9(SD=5.8) cigarettes per smoking day. The mean number of days smoked in past 30 days and the number of times smoked per day among current dual users were 20.0(SD=12.2) and 9.5(SD=7.8), respectively. Exclusive vapers reported vaping, on average, on 27.9(SD=3.5) of the past 30 days and vaping 16.3(SD=5.8) times per vaping day. The mean number of days vaped in past 30 days and the number of times vaped per day among current dual users were 21.4(SD=9.1) and 11.1(SD=7.4), respectively. Refillable, rechargeable (33.6%) and fruit (40.0%) were the most frequently used e-cigarette device and flavor, respectively, used by participants. In exclusive vapers and dual users, 35.7% used nicotine salt in their own e-cigarettes, 14.2% used free-base nicotine, 6.0% switched between salt and free-base, and 44.0% did not know what nicotine formulation was in their own e-cigarette device.

Characteristics of 20 study e-cigarette solutions

The nicotine concentration [28.9(SD=1.3) mg/mL], PG/VG [62.0(SD=5.5)/38.0(SD=5.5)], and density [1.2(SD=0.02) g/mL] did not substantially vary among the solutions and did not significantly differ by nicotine formulation condition (see Supplement Table S1). The pHs of the solutions were successively lower across free-base [M=8.21(SD=0.23)], 50% nicotine salt [M=7.30(SD=0.45)], and 100% nicotine salt [M=5.15(SD=0.27)] conditions. pHs were comparable across the 50% lactate and 50% benzoate solutions [M=6.90(SD=0.35) vs. M=7.02(SD=0.53)] and across the 100% lactate and 100% benzoate solutions [M=5.38(SD=0.34) vs. M=4.92(SD=0.19)].

Effects of nicotine formulation on appeal and sensory ratings

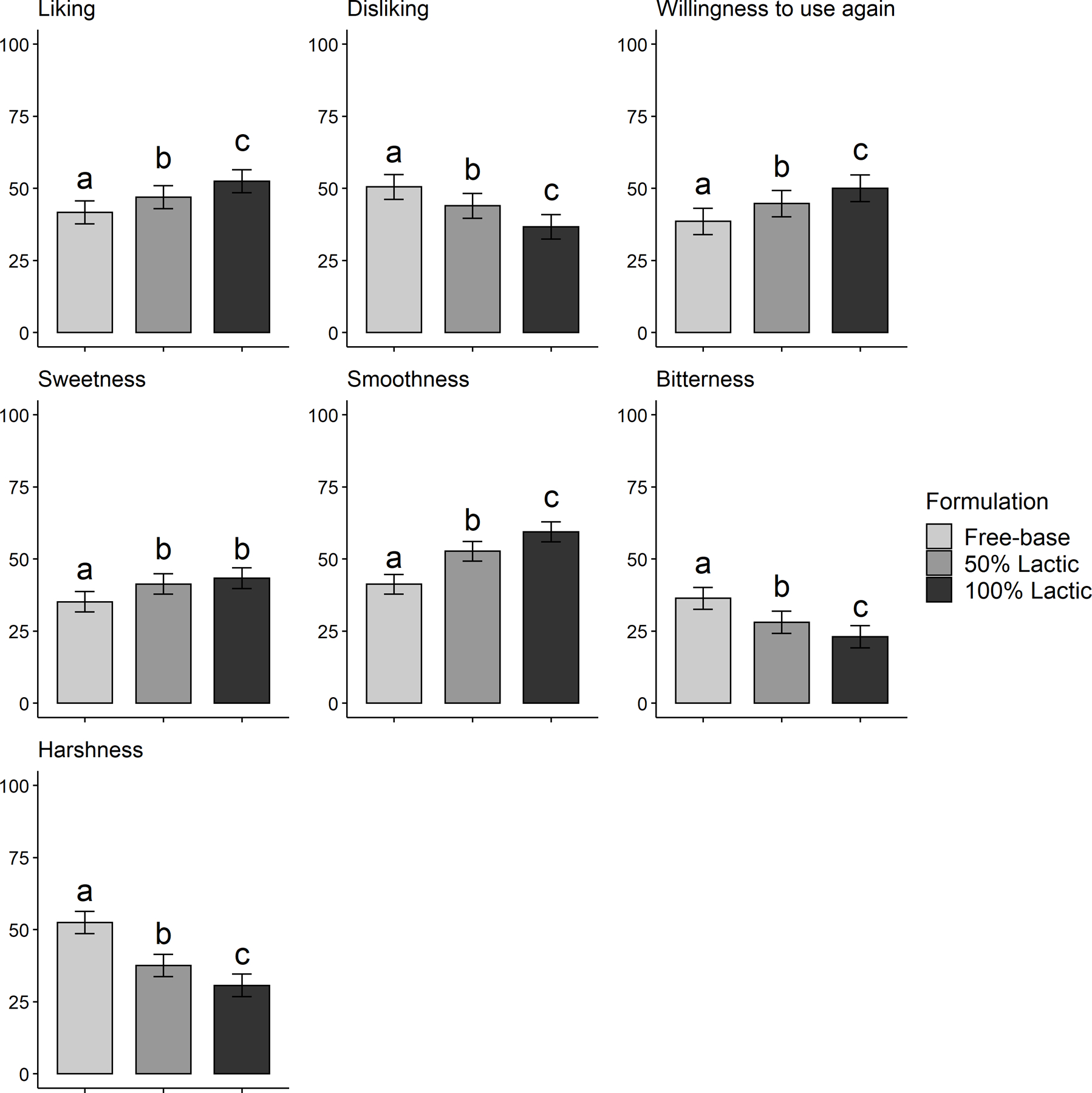

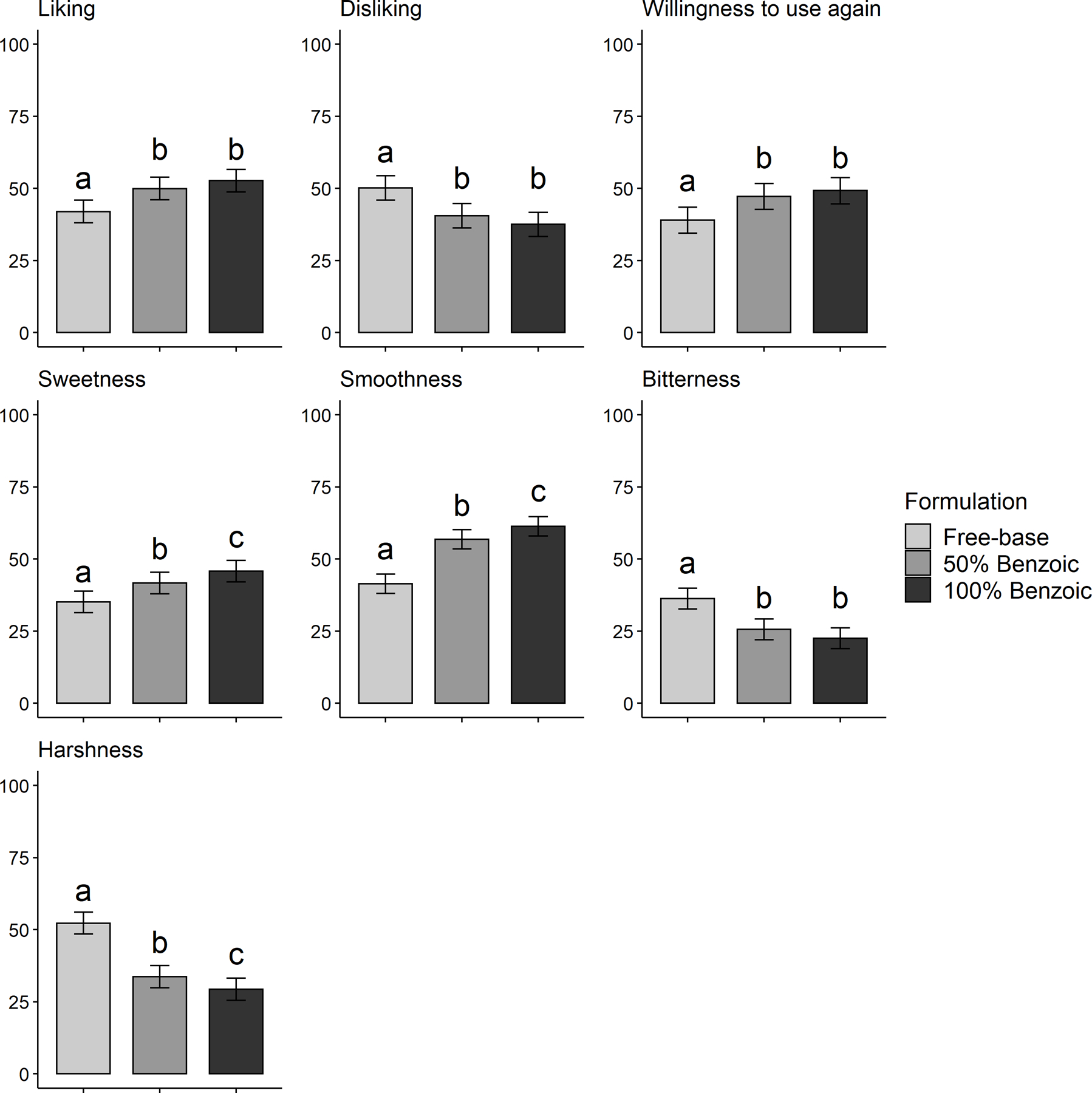

Depicted in Table 2, MLMs revealed that 100% and 50% nicotine salt (vs. free-base) formulations yielded significantly higher ratings of appeal (higher liking and willingness to use again, lower disliking) and more desirable sensory attributes (higher sweetness and smoothness, lower bitterness and harshness) for both acid types. Pairwise comparisons displayed in Figures 1 and 2 depict several dose-response effects (i.e., 100% vs. 50% conditions significantly differed). For nicotine lactate, 100% vs. 50% increased liking, willingness to use again, and smoothness, and reduced disliking, bitterness, and harshness (Figure 1). For nicotine benzoate, dose response effects of 100% vs. 50% were observed for sweetness, smoothness, and harshness (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Effects of Nicotine Formulation on Appeal and Sensory Attributes

| Estimates, 𝛽 (95% CI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appeal | Sensory attributes | ||||||

| Liking | Disliking | Willingness to use again | Sweetness | Smoothness | Bitterness | Harshness | |

| Formulation: Lactic | |||||||

| 50% Lactic vs. Free-base | 5.3* (1.8, 8.7) |

−6.5* (−10.3, −2.8) |

6.2* (2.5, 9.9) |

6.2* (2.6, 9.8) |

11.5* (8.0, 14.9) |

−8.3* (−11.7, −5.0) |

−14.9* (−18.5, −11.3) |

| 100% Lactic vs Free-base | 10.8* (7.3, 14.2) |

−13.8* (−17.6, −10.1) |

11.5* (7.8, 15.2) |

8.2* (4.7, 11.8) |

18.2* (14.7, 21.6) |

−13.3* (−16.7, −9.9) |

−21.8* (−25.5, −18.2) |

| Formulation: Benzoic | |||||||

| 50% Benzoic vs. Free-base | 8.0* (4.4, 11.6) |

−9.7v (−13.5, −5.8) |

8.2* (4.4, 12.1) |

6.6* (3.0, 10.1) |

15.5* (12.0, 18.9) |

−10.7* (−14.1, −7.2) |

−18.5* (−22.2, −14.9) |

| 100% Benzoic vs Free-base | 10.8* (7.2, 14.3) |

−12.6* (−16.5, −8.8) |

10.3* (6.4, 14.1) |

10.6* (7.1, 14.2) |

20.0* (16.5, 23.4) |

−13.7* (−17.1, −10.3) |

−22.9* (−26.6, −19.3) |

Statistically significant after Benjamini-Hochberg corrections for multiple testing to control the false-discovery rate at 0.05.

Figure 1.

Mean (SE) Appeal and Sensory Attribute Ratings, by Nicotine Formulation (lactic acid)

Note. Bars that do not share letters are significantly different in pairwise contrasts after correcting for multiple testing to maintain false discovery rate < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Mean (SE) Appeal and Sensory Attribute Ratings, by Nicotine Formulation (benzoic acid)

Note. Bars that do not share letters are significantly different in pairwise contrasts after correcting for multiple testing to maintain false discovery rate < 0.05.

Association of pH with appeal and sensory ratings

Depicted in Table 3, solutions with higher pH values (more basic/less acidic) were rated with lower appeal, sweetness, and smoothness and higher bitterness and harshness, controlling for flavor, in linear MLMs. Quadratic associations of pH with were also observed, indicating that the association of increasing pH with lower appeal, liking, willingness to use again, sweetness, and smoothness ratings tended to accelerate at pH values ≥7 (Table 3 and Supplement Figure S2). Similarly, the association of increasing pH with higher disliking, bitterness, and harshness accelerated with increasing pH. We found no significant interaction effects of pH with acid type (lactic vs. benzoic) on appeal and sensory ratings in 50% and 100% nicotine salt solutions (Supplement Table S2), indicating that the associations between pH and outcomes did not significantly differ by acid type.

Table 3.

Association of pH with Appeal and Sensory Attributes

| Outcome | Linear trend | Quadratic trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𝛽 (95% CI) | p-value | 𝛽 (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Appeal | Liking | −2.8 (−3.5, −2.0) | < .001 | −1.0 (−1.9, −0.1) | .035 |

| Disliking | 3.4 (2.6, 4.2) | < .001 | 1.3 (0.4, 2.3) | .008 | |

| Willingness to use again | −2.7 (−3.6, −1.9) | < .001 | −1.4 (−2.4, −0.5) | .006 | |

| Sensory attributes | Sweetness | −2.3 (−3.1, −1.6) | < .001 | −0.9 (−1.8, −0.9) | .035 |

| Smoothness | −4.6 (−5.4, −3.8) | < .001 | −2.4 (−3.3, −1.5) | < .001 | |

| Bitterness | 3.3 (2.6, 4.0) | < .001 | 2.0 (1.1, 2.8) | < .001 | |

| Harshness | 5.2 (4.4, 6.0) | < .001 | 3.3 (2.3, 4.2) | < .001 | |

Note. Models controlled for flavor. P-values were corrected for multiple testing to control the false-discovery rate using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure.

Test of difference in nicotine formulation effects by tobacco product use status or flavor

Tests of two-way interactions of nicotine formulation with tobacco product status or with flavor of study e-cigarette solution, were non-significant (Supplement Table S3), providing no evidence that the nicotine formulation effects differed across exclusive vapers, exclusive smokers, and dual users, or across tobacco, caramel, grape-menthol, or strawberry flavors.

Sensitivity analyses

Interactive effects of study nicotine formulation condition with nicotine formulation used in participants’ own device were non-significant for all outcomes (Supplement Table S4), indicating the generalizability of nicotine formulation effects regardless of what solutions participants use in their own device. PG/VG ratio adjusted models produced similar results with the main findings (Supplement Table S5), indicating no confounding of PG/VG with nicotine formulation condition.

DISCUSSION

This clinical experiment in adult nicotine product users found that both nicotine benzoate and nicotine lactate improved e-cigarette product appeal and sensory attributes relative to free-base nicotine. In several cases, effects followed a dose-response pattern whereby appeal and sensory experience was augmented for highly vs. partially protonated nicotine salt solutions, especially nicotine lactate. Across nicotine lactate and benzoate, pH was inversely associated with product appeal and desirable sensory attributes. Nicotine formulation condition effects did not differ by tobacco product use status, nor flavor of e-cigarettes.

Prior research has demonstrated that benzoic acid improves product appeal and sensory experience of vaping across different flavors.[3] This study’s findings meaningfully extend the literature by demonstrating that improvement of appeal and sensory attributes by nicotine salt formulations also generalize across flavors. More importantly, this study provides new evidence generalizing these results to nicotine lactate, a nicotine formulation frequently found in recent studies of e-cigarette solutions marketed in U.S.A and Netherlands [4,5].

This study yields a new finding that an e-cigarette solution’s pH was inversely associated with the perceived appeal and desirable sensory attributes of the solution, particularly after crossing the threshold from acidity to alkalinity (≥7). Evidence of non-significant acid type × pH interactions in this study suggests that the association of pH with appeal and sensory ratings held, regardless of whether lactic or benzoic acid was introduced to manipulate acidity-alkalinity. Hence, pH could be a cross-cutting metric indicative of the appeal and sensory qualities of e-cigarette solutions.

If regulatory agencies were to apply this study’s results to actionable policies, they could consider limiting inclusion of acid additives in e-cigarettes (or setting a minimum pH level) to decrease the appeal of e-cigarettes with medium or high nicotine concentrations. Given previous evidence that young populations with no history of cigarette smoking are more sensitive to harshness-enhancing effects of nicotine free-base vs. nicotine benzoate salt,[3] acid additive restrictions or minimum pH thresholds could prevent e-cigarette use among subgroups who do not use e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation aid. By contrast, older adult cigarette smokers who may be accustomed to the harshness and bitterness of free-base nicotine in tobacco smoke may be less deterred from using e-cigarettes with high pH because they may find such sensations more tolerable. Our findings did not provide evidence that the nicotine formulation effects differed between exclusive smokers, dual users, and vapers in this general adult sample, although the subgroup analysis may have had limited power. Also, there was not a large enough subsample of never smokers to test nicotine formulation effects in this important subgroup. Isolating whether there are differences in nicotine formulation effects by never vs. ever smoking status merits further research. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration considers each product separately and how regulation of products impact on youth uptake and on smoker’ likelihood of switching to less harmful products. By contrast, articles 7 (6d) and 20 (3c) of the European Tobacco Products Directive prohibits additives in e-cigarette products that facilitate inhalation or nicotine uptake, and could consider lactic, benzoic, and other organic acid additives in nicotine salt formulations under these policies.[16]

This study has limitations. First, the exposure paradigm has limits. There were 20 exposures during a single experimental session with short washouts between trials. This paradigm may not represent vaping patterns for some participants in the real world, especially for lighter vapers who may be unaccustomed to vaping those amounts within 4 hours. Additionally, each product exposure was brief (2 puffs) providing a small sample of experience with each product. These limits could reduce appeal ratings overall and restrict ability to differentiate the sensory attributes across products, which would reduce variability and statistical power. Consequently, this study’s effect sizes may be underestimates. Second, only one nicotine concentration level was tested in this study. While controlling the nicotine concentration is important for internal validity to isolate effects of nicotine formulation per se, the ecological validity is hampered because free-base products on the market usually have a lower concentration than what was tested here. Third, while lactic and benzoic acids may be the most frequently used acid additives in e-cigarettes, it is unclear whether effects found in this study generalize to other acids on the market (e.g., levulinic). Fourth, lack of biochemical verification of tobacco product use at orientation and deprivation at experimental session are limitations. Fifth, the effect of pH of the participants’ current e-cigarettes was not examined in this study. However, we found non-significant interaction effects of nicotine formulation condition in experiment with current nicotine formulation in participants’ own e-cigarettes on appeal and sensory outcomes. Hence, the primary nicotine formulation results are not likely to be inflated by pre-existing preferences for nicotine salt products. Sixth, while the overall sample provided sufficient statistical power for testing the study’s primary aims, subsamples may not have been large enough to detect interactions with tobacco product use status. Finally, the remote paradigm may provide less experimental control than laboratory settings and introduce unknown sources of error. Every effort was made to maintain standardization of protocols and experimental control and compliance with the procedures (e.g., monitoring participants via 1:1 video conference for the duration of the experiment). This included review of videotapes of study visits to determine whether all procedures were followed, including the timing of each exposure and inter-exposure interval. However, objective measures of puff topography were not collected, leaving us without precise puff duration estimates that would clarify exactly how compliant participants were in following the puffing parameters.

In conclusion, this experiment conducted with adult users of cigarettes and/or e-cigarettes found that 50% and 100% nicotine salt (vs. free-base) e-cigarette formulations produced higher ratings of appeal and more desirable sensory attributes, which were generalizable across tobacco use status and flavor. We also observed that increasing pH was associated with worsening appeal and sensory attributes across nicotine formulations. Our findings suggest that both acid additives and pH could be viable regulatory targets for e-cigarettes in efforts to reduce vaping among populations who find harsh and bitter e-cigarette products unappealing.

Supplementary Material

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS.

What is already known on this topic

Benzoic acid additives in electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) improves the appeal and sensory experience of vaping e-cigarettes.

What this study adds

This study demonstrates that both nicotine lactate and nicotine benzoate improve the appeal and sensory attributes of vaping across different flavors.

This study yields a new finding that an e-cigarette solution’s pH was inversely associated with the perceived appeal and desirable sensory attributes of the solution across nicotine lactate and benzoate.

How this study might affect research, practice or policy

Regulating the amount of acid additives or pH in e-cigarettes may decrease the appeal of e-cigarettes for populations who may find harsh and bitter e-cigarette aerosol.

Funding

This project was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute and the FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) under Award Number U54CA180905, National Cancer Institute under award number R01CA229617, National Institute on Drug Abuse under award number K24DA048160.

Footnotes

Registration

This study was registered under ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03742817 under the title “Effects of e-Cigarettes on Perceptions and Behavior.”

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NCI, NIDA or FDA.

Competing interests

None declared.

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The study obtained ethics approval from the University of Southern California institutional review board (protocol #: UP-20-00744) and participants gave informed consent before participation.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.DeVito EE, Krishnan-Sarin S. E-cigarettes: impact of e-liquid components and device characteristics on nicotine exposure. Curr Neuropharmacol 2018;16(4):438–459. doi: 10.2174/1570159X15666171016164430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackler RK, Ramamurthi D. Nicotine arms race: JUUL and the high-nicotine product market. Tob Control 2019;28(6):623–628. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leventhal AM, Madden DR, Peraza N, et al. Effect of exposure to e-cigarettes with salt vs free-base nicotine on the appeal and sensory experience of vaping: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4(1):e2032757–e2032757. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.32757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harvanko AM, Havel CM, Jacob P, Benowitz NL. Characterization of nicotine salts in 23 electronic cigarette refill liquids. Nicotine Tob Res 2020;22(7):1239–1243. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pennings JL, Havermans A, Pauwels CG, Krüsemann EJ, Visser WF. Talhout R. Comprehensive Dutch market data analysis shows that e-liquids with nicotine salts have both higher nicotine and flavour concentrations than those with free-base nicotine. Tob Control. Published Online First: 5 January 2022. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duell AK, Pankow JF, Peyton DH. Nicotine in tobacco product aerosols: ‘It’s déjà vu all over again’. Tob Control 2020:29(6):656–662. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talih S, Salman R, Soule E, et al. , Electrical features, liquid composition and toxicant emissions from ‘pod-mod’-like disposable electronic cigarettes. Tob Control. Published Online First: 12 May 2021. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voos N, Goniewicz ML, Eissenberg T. What is the nicotine delivery profile of electronic cigarettes?. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2019;16(11):1193–1203. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2019.1665647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benowitz NL. The central role of pH in the clinical pharmacology of nicotine: Implications for abuse liability, cigarette harm reduction and FDA regulation. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2022;111(5):1004–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lisko JG, Tran H, Stanfill SB, Blount BC, Watson CH. Chemical composition and evaluation of nicotine, tobacco alkaloids, pH, and selected flavors in e-cigarette cartridges and refill solutions. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17(10):1270–1278. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shao XM, Friedman TC. Pod-mod vs. conventional e-cigarettes: nicotine chemistry, pH, and health effects. J Appl Physiol 2020;128(4):1056–1058. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00717.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dwan K, Li T, Altman DG, Elbourne D. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised crossover trials. BMJ 2019;366:l4378. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leventhal AM, Goldenson NI, Barrington-Trimis JL, Pang RD, Kirkpatrick MG. Effects of non-tobacco flavors and nicotine on e-cigarette product appeal among young adult never, former, and current smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;203:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson MK, Whitted L, Mason TB, Pang RD, Tackett AP, Leventhal AM. Characterizing different-flavored e-cigarette solutions from user-reported sensory attributes and appeal. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. Published Online First: 25 April 2022. doi: 10.1037/pha0000563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol 1995;57(1):289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.European Union. Tobacco Products Directive 2014/40/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council, 2014. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014L0040. (Accessed 17 May, 2022)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.