Abstract

Cyclic AMP (cAMP) signaling is essential to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) pathogenesis. However, the roles of phosphodiesterases (PDEs) Rv0805, and the recently identified Rv1339, in cAMP homeostasis and Mtb biology are unclear. We found that Rv0805 modulates Mtb growth within mice, macrophages and on host-associated carbon sources. Mycobacterium bovis BCG grown on a combination of propionate and glycerol as carbon sources showed high levels of cAMP and had a strict requirement for Rv0805 cNMP hydrolytic activity. Supplementation with vitamin B12 or spontaneous genetic mutations in the pta-ackA operon restored the growth of BCGΔRv0805 and eliminated propionate-associated cAMP increases. Surprisingly, reduction of total cAMP levels by ectopic expression of Rv1339 restored only 20% of growth, while Rv0805 complementation fully restored growth despite a smaller effect on total cAMP levels. Deletion of an Rv0805 localization domain also reduced BCG growth in the presence of propionate and glycerol. We propose that localized Rv0805 cAMP hydrolysis modulates activity of a specialized pathway associated with propionate metabolism, while Rv1339 has a broader role in cAMP homeostasis. Future studies will address the biological roles of Rv0805 and Rv1339, including their impacts on metabolism, cAMP signaling and Mtb pathogenesis.

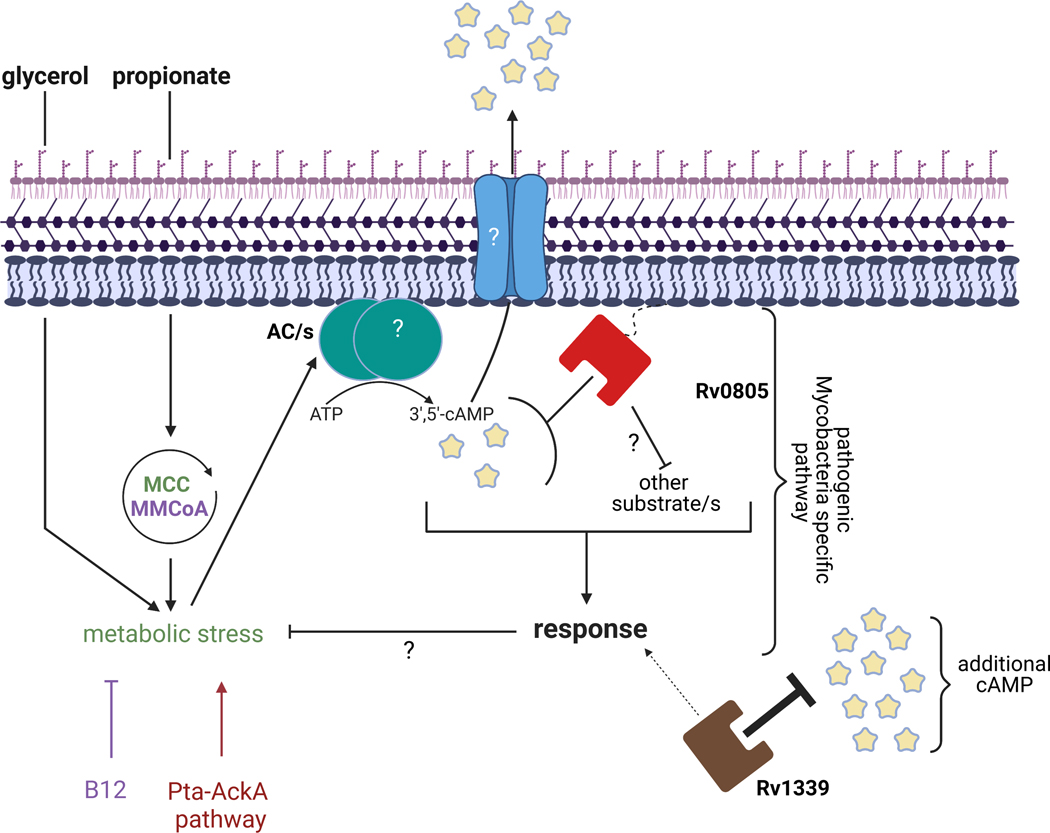

Graphical Abstract

This study shows that the mycobacterial phosphodiesterase Rv0805 contributes to Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence and modulates bacterial growth on host-associated carbon sources. Surprisingly, propionate was found to elevate cyclic AMP levels in TB complex mycobacteria, and the cyclic nucleotide hydrolytic activity of Rv0805 is required for growth of TB complex mycobacteria on a mixture of propionate and glycerol. Expression of an unrelated mycobacterial phosphodiesterase (Rv1339) reduced cAMP levels but failed to fully restore growth of the Rv0805-deletion mutants. We propose a model in which localized cAMP hydrolysis by Rv0805 modulates activity of a specialized pathway associated with propionate metabolism, while Rv1339 has a broader role in mycobacterial cAMP homeostasis.

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) kills approximately 2 million people annually and is estimated to latently infect one-fourth of the world’s population [1]. The large public health burden imposed by TB is worsened by the rise of antibiotic resistance and slow development of novel therapeutics [1]. Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is a facultative intracellular pathogen that obtains carbon directly from the host, and emerging evidence suggests that Mtb metabolism during infection is a major virulence determinant [2, 3]. Many aspects of how Mtb regulates its metabolism remain unclear, but it is known that coupled signal transduction pathways often control metabolic circuits [4–10].

Mtb encodes a large repertoire of 3’,5’-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-producing and binding proteins, including at least 15 adenylyl cyclases (ACs) and 11 cAMP-modulated effector proteins [11–14]. cAMP produced by mycobacteria in response to the macrophage environment and host-associated conditions has integral roles in Mtb biology [12, 15–18]. While intrabacterial cAMP modulates Mtb gene expression and protein function, secreted cAMP alters macrophage signaling [16, 19–24]. Anti-tubercular compounds that dysregulate cAMP levels and cause carbon source- and macrophage environment-specific Mtb growth defects exploit functional links between cAMP signaling and central carbon metabolism in Mtb, further demonstrating the importance of cAMP signaling in Mtb [10, 16, 23–27].

cAMP signaling in Mtb is mediated through transcriptional and post-translational responses. Three proteins in Mtb whose activities are modulated by cAMP include the transcriptional regulators, CRPMt (Rv3676) and Cmr (Rv1675c), and protein lysine acetyltransferase, Rv0998 [12, 23, 26–29]. Deletion of crpMt impacts central metabolism and attenuates Mtb for growth during mouse infection [26, 27, 29]. Cmr regulates genes involved in virulence and persistence, including some members of the dormancy survival regulon [21, 30]. Rv0998 modulates the activity of acetyl-CoA synthetase (ACS) and redirects carbon flow for adaptation to hypoxia and metabolic stress [23, 24, 31, 32]. In addition, bacterially-secreted cAMP affects TNF-α levels in Mtb-infected macrophages [16, 19] and contributes to phagolysosomal fusion inhibition by M. microti [33, 34].

Balanced production and degradation of cAMP provides dynamic responsiveness to cell stressors and nutrient sources [12, 13]. Rv0805, a Class III metallophosphoesterase, was initially thought to be the only phosphodiesterase (PDE) for cAMP degradation in Mtb despite the unusually large number of ACs [13, 17, 35, 36]. An orthologue of cpdA from C. glutamicum (cpdAcg), Rv1339, has recently been identified in M. smegmatis as an atypical class II PDE, where overexpression of Rv1339 decreases cAMP levels and contributes to antibiotic sensitivity [36, 37]. However, the role of Rv1339 in pathogenic mycobacteria has not been well characterized. Crystal structure and biochemical analyses of Rv0805 demonstrate that Rv0805 forms a dimer with divalent cations playing roles in catalysis and stabilization of Rv0805′s dimerization [35, 38].

The extent to which Rv0805 contributes to cAMP homeostasis and metabolism of TB complex mycobacteria is not known. Rv0805 displays a broad catalytic range on linear and cyclic PDE substrates in vitro [35, 38, 39]. Overexpression studies have identified Rv0805-dependent cAMP decreases and effects on the transcriptome along with PDE-independent interactions of Rv0805 with the mycobacterial cell wall that are facilitated by its C-terminal extension (CTE) [19, 35, 40–42]. Together with the biochemical analyses, these results raise numerous questions about the biological roles of Rv0805 and its cognate substrate/s in TB complex mycobacteria.

Observations from transposon mutagenesis screens suggest a role for Rv0805 in bacterial growth on cholesterol, propionate or long chain fatty acids [43, 44], and cAMP signaling has been implicated in lipid and propionyl-CoA metabolism of TB complex mycobacteria [23, 25]. Propionyl-CoA is a high energy intermediate derived from catabolism of odd-chained fatty acids that enables synthesis of virulence-associated lipids [45], but its accumulation is growth inhibitory [46]. Thus, propionyl-CoA is a double-edged sword that requires effective strategies for use and detoxification. Mtb employs the methylcitrate cycle (MCC), the methylmalonyl CoA (MMCoA) pathway, and incorporates propionyl-CoA into triacylglycerol (TAG) formation for these purposes [43, 47–49].

In the present work, we found that catalytic activity against cyclic nucleotides is a defining feature of Rv0805 in TB complex mycobacteria. The cNMP PDE activity of Rv0805 was essential for growth and cAMP homeostasis of Mycobacterium bovis BCG (BCG) exposed to media containing a mixture of glycerol and propionate (GP). Addition of vitamin B12 (B12) or spontaneous mutations in pta, ackA, or Rv0806c corrected the growth defect of BCGΔRv0805 in media with GP and reduced propionate-associated increases in cAMP levels. Furthermore, the C-terminal localization-determining domain of Rv0805 was required for bacterial growth. While Rv1339 had potent cAMP PDE activity in BCG, overexpression of Rv1339 only partially complemented Rv0805 function. Based on these results, we propose a model in which localized Rv0805 PDE activity is responsible for Rv0805’s importance to carbon metabolism and growth of TB complex mycobacteria.

RESULTS

Rv0805 catalytic activity

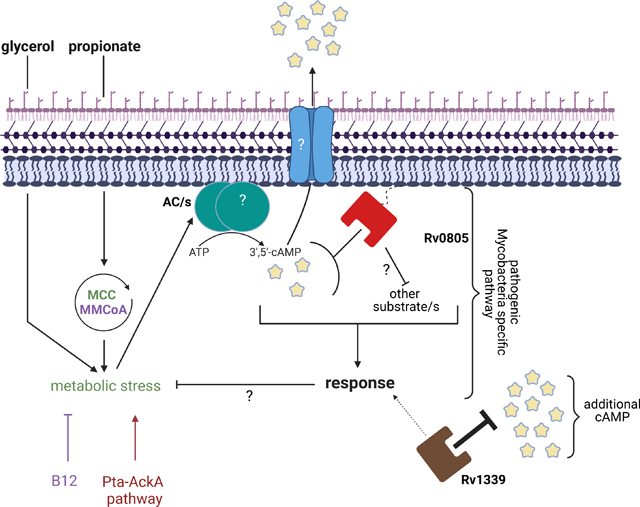

Rv0805 has been identified as the primary cAMP PDE in TB complex mycobacteria [35, 36, 50]. However, weak activity against cAMP in vitro and pleiotropic effects associated with Rv0805 overexpression have raised questions about the importance of cAMP hydrolysis by Rv0805 to Mtb biology [35, 38, 39]. We analyzed the in vitro activity of Rv0805 and that of a flagship cAMP phosphodiesterase, CpdA, from E. coli (CpdAEc). N-His-Rv0805 and N-His- CpdAEc were overexpressed in E. coli and purified under non-denaturing conditions (Fig. 1A). The catalytic activities of the purified proteins were first measured using Bis(p-nitrophenyl) phosphate (BnPP) as a generic substrate, under different pH conditions or in the presence of various metal ions. Both proteins exhibited similar levels of BnPP cleavage, with the highest activity levels occurring at pH ≥ 8.5 (Fig. 1B). Rv0805 was less restrictive than CpdAEc in its metal ion requirement, and both proteins were most active in the presence of Co2+ or Mn2+ (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1: Biochemical activities of Rv0805 and CpdAEc.

(A) Purification of recombinant N-His-Rv0805 and N-His-CpdAEc. Lane M, broad range protein MW marker (Promega). (B) Activities of Rv0805 and CpdAEc using BnPP as a substrate at indicated pH. (C) Activities of Rv0805 and CpdAEc using BnPP as a substrate in the presence of 0.1 mM of indicated metal ions. (D) Cleavage of 2′, 3′-cAMP by Rv0805 and CpdAEc. 10 mM 2′, 3′-cAMP, 2′AMP, and 3′-AMP were served as standards. (E) Cleavage of 2′, 3′-cGMP by Rv0805 and CpdAEc. 10 mM 2′, 3′-cGMP and 2′GMP/ 3′-GMP mixtures were served as standards. (F) Cleavage of 3′, 5′-cAMP by Rv0805 and CpdAEc. 10 mM 3′, 5′-cAMP, 3′AMP, and 5′-AMP were served as standards. (G) Cleavage of 3′, 5′-cGMP by Rv0805 and CpdAEc. 10 mM 3′, 5′-cGMP and 5′-GMP were served as standards. (H) Reactions of 3′, 5′-cAMP with purified Rv0805 or CpdAEc were separated using HPLC and monitored at 254 nm. (I) Detection of choline cleaved from GPC incubated with various concentrations of Rv0805, CpdAEc, or BSA. (J) Comparison of effect of divalent cations and Rv0805 point mutations on GDPD activity.

Statistical analysis of Panel C using two-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni correction. Compared each column to No metal control. ***, P <0.001.

The activities of Rv0805 and CpdAEc with different cNMPs were further analyzed using thin layer chromatography (TLC) with samples prepared at pH 8.5 and with 0.1 mM MnCl2. cAMP and 2’, 3’-cNMPs are structural isomers generated through distinct mechanisms, as cAMP is produced from ACs while 2’, 3’-cNMPs arise through the degradation of RNA [51, 52]. Rv0805 or CpdAEc at 2.5 μM completely cleaved the available 2′, 3′-cAMP (Fig. 1D) and 2′, 3′-cGMP (Fig. 1E). In contrast, only 0.25 μM CpdA was sufficient to completely hydrolyze the same amount of 3′, 5′-cAMP and 3′, 5′-cGMP; while Rv0805 showed little 3′, 5′-cAMP, or no detectable 3′, 5′-cGMP hydrolysis with up to 12.5 μM protein (Fig. 1F, G). The ~50-fold higher activity we observed for Rv0805 hydrolysis of 2′, 3′-cAMP compared to 3′, 5′-cAMP (Fig. 1D, F) is consistent with a previous report [39]. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) also showed that hydrolytic activity of Rv0805 with 3′, 5′-cAMP is low relative to that of CpdAEc, (Fig. 1H). In addition, Rv0805 converted 3′, 5′-cAMP into both 3′-AMP and 5′-AMP, whereas 5′-AMP was the only product with CpdAEc (Fig. 1H). These results indicate that purified Rv0805 has a strong bias for 2′, 3′-cNMPs relative to 3’,5’-cNMP’s (Fig. 1D–G) in agreement with previous studies [39, 41], while CpdAEc equally hydrolyzes both 2’,3’ and 3′, 5′-cNMPs. Neither enzyme showed a significant preference among purine nucleotides as cleavage of cAMP and cGMP was similar.

Rv0805 belongs to a superfamily of calcineurin-like metallophosphoesterases (MPEs), including purple acid phosphatase, Mre11, and GpdQ [53]. GpdQ is a promiscuous glycerophosphodiesterase (GDPD) that cleaves glycerophospholipids to generate glycerol 3-phosphate (Gly3P), a key intermediate for phospholipid synthesis and central metabolism [54]. Despite having only 22% sequence identity with GpdQ [55], Rv0805 has high structural similarities to GpdQ as suggested by a root-mean-square (r.m.s.) deviation of 1.8Å between Rv0805 V15-P265 and GpdQ L2-S253 monomers and 2.1Å between dimers [41, 42, 53]. We used a choline oxidase and HRP coupled fluorometric assay to investigate whether Rv0805 has GDPD activity and found that both Rv0805 and CpdAEc produced choline and Gly3P from glycerophosphocholine (GPC) (Fig. 1I). The GDPD activity of CpdAEc and Rv0805 is consistent with the presence of the conserved catalytic block DXH-Xn-GD-Xn-GNHD/E-Xn-H-Xn-GHXH, which is found in all class III PDEs, and suggests that the presence of these motifs rather than structural similarities is most indicative of GDPD activity [53].

Two catalytic mutants of Rv0805 were generated based on previous reports [35, 38, 41, 42] in an effort to separate the different activities of Rv0805 (Fig. S1). Rv0805N97A is described as a catalytic null mutant despite one report that it maintains some weak activity on 3’,5’-cAMP [35, 38, 41]. We found that Rv0805N97A was unable to cleave BnPP, 3’,5’-cAMP, and 2’,3’-cGMP, but surprisingly amino acid N97 was not required for Rv0805-mediated cleavage of GPC (Fig. S1, Fig. 1J). We therefore decided against using Rv0805N97A as a catalytic null mutant in subsequent studies. Rv0805H98A, a mutant reported to have selectively lost cNMP hydrolytic activity [39, 41], was also tested and found to be defective for cNMP hydrolysis but was more active than native Rv0805 protein against GPC in the presence of Mg2+ (Fig. S1, Fig. 1J). While these data indicate that Rv0805 substrate specificity is likely broader than previously recognized, in vitro analyses are limited in their ability to predict biological importance for any given substrate. Rv0805 has been most cited as a primary cAMP PDE in Mtb, so we first sought to determine the biological significance of Rv0805 and its cAMP hydrolytic activity for TB complex mycobacteria.

Rv0805 mediates Mtb growth within macrophages, during murine infection, and during growth in the presence of propionate

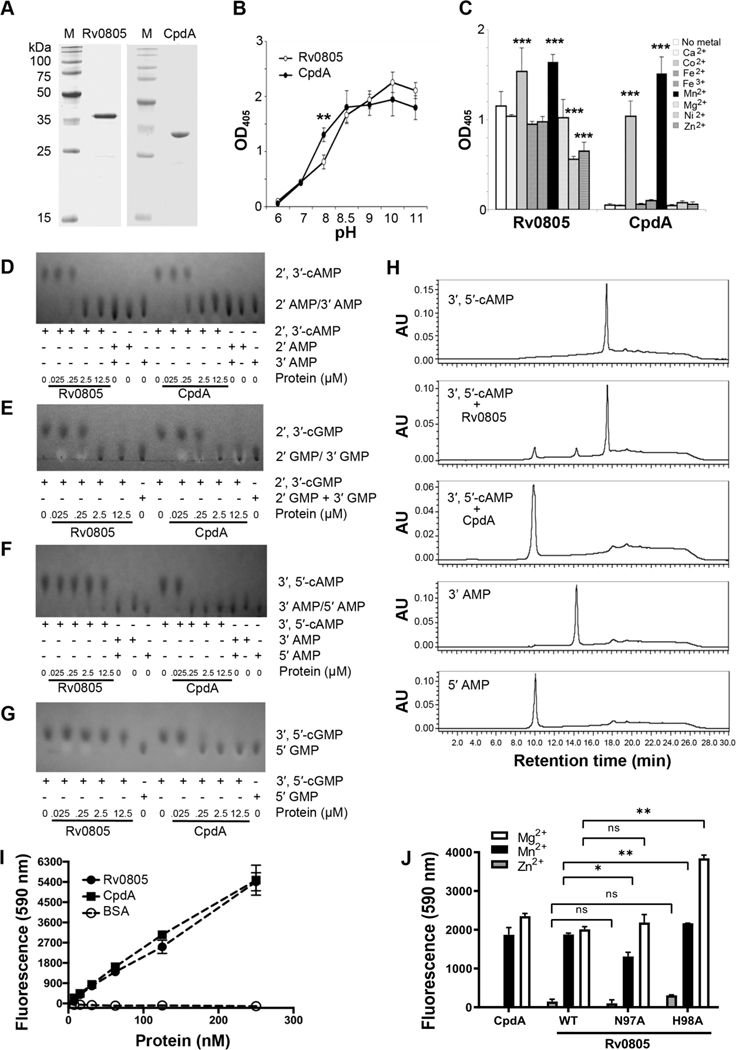

The DNA sequences of Rv0805 open reading frame (ORF) in Mtb and BCG are identical. We generated Rv0805 knockout mutants in Mtb and BCG to address the physiological relevance of Rv0805 (Fig. S2), and the experiments were performed using either genetic background as specified. BCGΔRv0805 grown in Mycomedia [Middlebrook 7H9 supplemented with 0.5% glycerol, 10% oleic acid-albumin-catalase-dextrose (OADC), 0.05% Tween-80] had a clumpy phenotype and increased sensitivity to low extracellular pH, while the Mtb mutant H37RvΔRv0805 was defective for growth in mouse lungs and murine macrophages (Fig. S3, Fig. 2A–C). Intracellular growth of Mtb is supported by lipid and fatty acid utilization, which can lead to the toxic accumulation of propionyl-CoA intermediates [43, 46, 56, 57]. We investigated the role of Rv0805 in central carbon metabolism via growth analysis on various carbon sources, including propionate. Rv0805 deletion mutants in both BCG and Mtb grew well in Mycomedia but were defective for growth in 7H12 media with propionate as a primary carbon source (Fig. 2D, E). H37RvΔRv0805, but not BCGΔRv0805, had additional growth defects in 7H12 media with either glycerol or cholesterol as a primary carbon source (Fig. 2E). All these growth deficiencies were rescued by complementation with a wildtype (WT) copy of Rv0805 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Mtb Rv0805 is required for optimal survival in an infected host.

(A) Growth of WT BCG, BCGΔRv0805, and BCGΔRv0805::Rv0805 in Mycomedia adjusted pH at 5.5. (B) Infection of J774.16 macrophages with MtbH37Rv WT, H37RvΔRv0805, and H37RvΔRv0805::Rv0805. (C) Eight to ten-week-old C3HeB/FeJ female mice were aerogenically infected with 50–100 CFU of Mtb H37Rv WT, H37RvΔRv0805, and H37RvΔRv0805::Rv0805. At the indicated time points after infection, lung bacterial loads were assessed. A group of 8 to10-week-old C57BL/6 mice were used for enumerating the bacterial loads in the lungs at 16–24 hours post-infection to determine the inoculum size. Four mice per group per time point were studied. The bacterial burden was significantly lower in the lungs of mice infected with the ΔRv0805 deletion mutant compared with WT H37Rv strain at 1, 3 and 6 months post infection. (D and E) BCG (D) or H37Rv (E) strains were grown in Mycomedia or 7H12 media containing 10 mM glycerol, 100 μM cholesterol, or 10 mM propionate in St/Amb conditions. Data shown are means of at least 2 independent experiments, except for d10 datapoints in (D) Glycerol, Cholesterol, or Propionate conditions, which are from one experiment, and Mycomedia condition in (E), which is representative of two similar experiments. Error bars denote SD. *, P <0.05; **, P <0.01; ***, P <0.001; ****, P <0.0001. In panels A, D, and E, p values displayed are between BCG and BCGΔRv0805, unless otherwise shown. p values between KO and complement strains are all <0.05, except for d15 of BCG in media with cholesterol, d5 and 14 of H37Rv in media with propionate, and d21 of H37Rv in media with glycerol where there is no significant difference.

Rv0805 limits effects of propionate toxicity in presence of glycerol

Itaconic acid (ITA), which reduces isocitrate lyase (ICL) activity, inhibited growth of Mtb on propionate, but had no effect on WT BCG or BCGΔRv0805 (Fig. S4A, B) [48, 58]. These results are consistent with a prior report indicating that reduced ICL activity in BCG could limit capacity for detoxifying methyl citrate cycle intermediates [59], and suggests that Rv0805 influences propionate metabolism in WT BCG in a largely ICL-independent manner. We reasoned that the growth defect for BCGΔRv0805 on propionate (Fig. 2D) could be used as a simplified model to further characterize the interactions of Rv0805 with propionate metabolism.

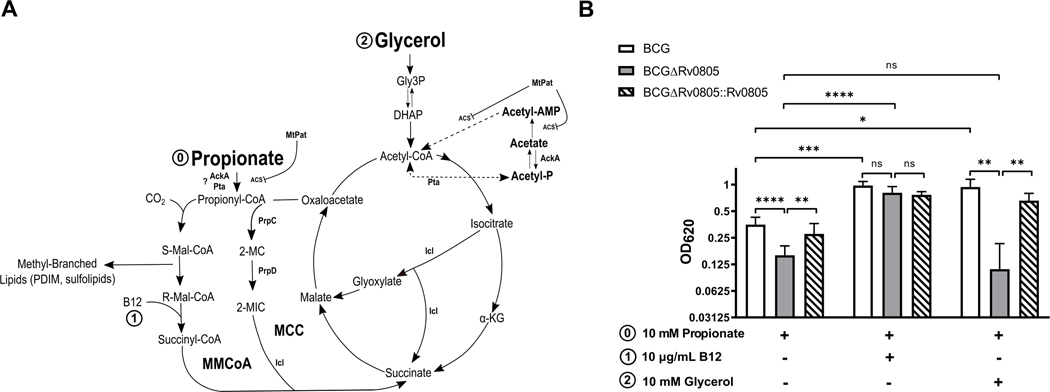

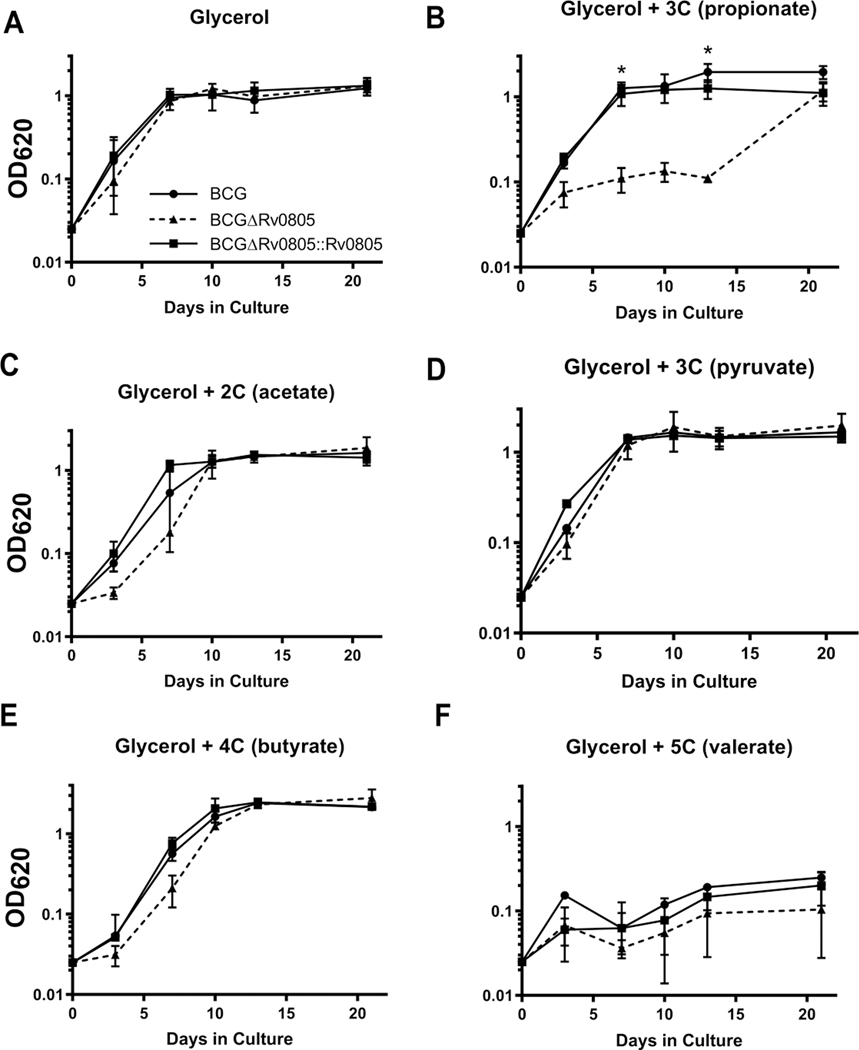

The MMCoA pathway generates virulence lipids from propionyl-CoA precursors and provides TCA anaplerotic substrates through a methylmalonyl-CoA mutase and a B12-catalyzed reaction (Fig. 3A) [47]. B12 treatment improved growth of WT BCG and fully restored growth of BCGΔRv0805 on propionate, showing that the B12-catalyzed reaction compensates for loss of Rv0805. Acetate has been shown to rescue ICL deficient bacteria in propionate [43], so we attempted to rescue BCGΔRv0805 grown on propionate with acetate. The glycolytic end-product pyruvate and TCA intermediate succinate were also tested. All additions marginally increased growth of WT BCG and BCGΔRv0805 but none rescued the Rv0805-dependent growth defect (Fig. S4C–E). In contrast, supplementation with glycerol, a glycolytic and gluconeogenic substrate, improved growth of WT BCG, but not the BCGΔRv0805 mutant, on propionate (Fig. 3B). BCGΔRv0805 appeared to grow less well on propionate when glycerol was also present, but the differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 3B, Fig. S5). Growth of BCGΔRv0805 was not affected by the presence of glycerol combined with other carboxylic acids of varying lengths, indicating a specific effect of the glycerol and propionate (GP) mixture (Fig. 4A–E). One exception was growth inhibition of all strains in the presence of glycerol with valeric acid, which can be broken down into acetyl-CoA and propionyl-CoA (Fig. 4F).

Figure 3: Rv0805 facilitates bacterial growth in GP.

(A) The methyl citrate cycle (MCC) and methylmalonyl-CoA (MMCoA) pathways are two mechanisms of propionyl-CoA detoxification. Both pathways can generate TCA intermediates, but the TCA anaplerotic generating step of the MMCoA pathway requires B12. Rv0998 can acetylate and inactivate ACS, it is unknown if Rv0998 contributes to the growth defect of BCGΔRv0805. It is unknown if Pta and AckA in mycobacteria can generate propionyl-CoA in an analogous pathway to acetyl-CoA formation. PrpC, methyl citrate synthase; PrpD, methyl citrate dehydratase; Icl, isocitrate lyase; AckA, acetate kinase; Pta, phosphate acetyltranferase; ACS, acetyl-CoA synthetase; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; α-KG, alpha-ketoglutarate. (B) Bacterial growth measured by OD620 was determined for BCG strains (BCG, ΔRv0805, ΔRv0805::Rv0805) at day 7 in 10 mM propionate media with additives listed. Data shown are means of at least 2 independent experiments. Error bars denote SD. *, P <0.05; **, P <0.01; ***, P <0.001; ****, P <0.0001.

Figure 4: BCGΔRv0805 growth defect is specific to GP.

BCG strains (BCG, ΔRv0805, and ΔRv0805::Rv0805) were grown under St/Amb condition in 10 mM glycerol alone, or 10 mM glycerol with 10 mM of specified carboxylic acid. 10 mM glycerol with 10 mM pyruvate served as a control for a non-carboxylic acid carbon. Only glycerol and propionate (GP) caused a large growth defect of BCGΔRv0805, indicating Rv0805 is required for a propionate specific pathway. Data shown are means of 2 independent experiments. Error bars denote SD. *, P <0.05. P values displayed are between BCG and BCGΔRv0805, unless otherwise shown. Growth of BCG and BCGΔRv0805 was not statistically significant on d10. P values between KO and complement strains on d7, 10, and 13 are all <0.05.

Growth of BCG on GP media is concomitant with a decrease in intracellular pH (pHi), and earlier work with ICL-deficient Mtb revealed that a defective MCC induces perturbations in pHi [46, 59]. We measured pHi to determine whether the Rv0805 dependent growth defect we observed on GP media was due to dysregulated pHi. While the decreased pHi in GP media we observed was consistent with what was previously described [59], these pHi effects were independent of Rv0805 (Fig. S6C). Together, these results indicate that the growth defect of BCGΔRv0805 on GP is not due to reduced pHi, although they do not rule out a pH-associated metabolic consequence of growth on GP that is mitigated by Rv0805.

Spontaneous mutations in the pta-ackA operon rescue BCGΔRv0805 growth defect

We consistently observed restoration of BCGΔRv0805 growth after ~13 days in GP and reasoned that it could be caused either by phenotypic adaptation or genetic mutation (Fig. 4B, S7). We tested the possibility of phenotypic adaptation by passaging BCGΔRv0805 to 21 days in GP media (GP passaged) and then growing GP-passaged BCGΔRv0805 in non-selective growth conditions including Mycomedia and 7H12 glycerol for 7 days before re-exposing the bacteria to GP. None of the conditions tested restored the delayed growth phenotype of BCGΔRv0805 (Fig. S7B), so GP-passaged BCGΔRv0805 bacteria were plated for single colonies and evaluated for mutations (Fig. S8).

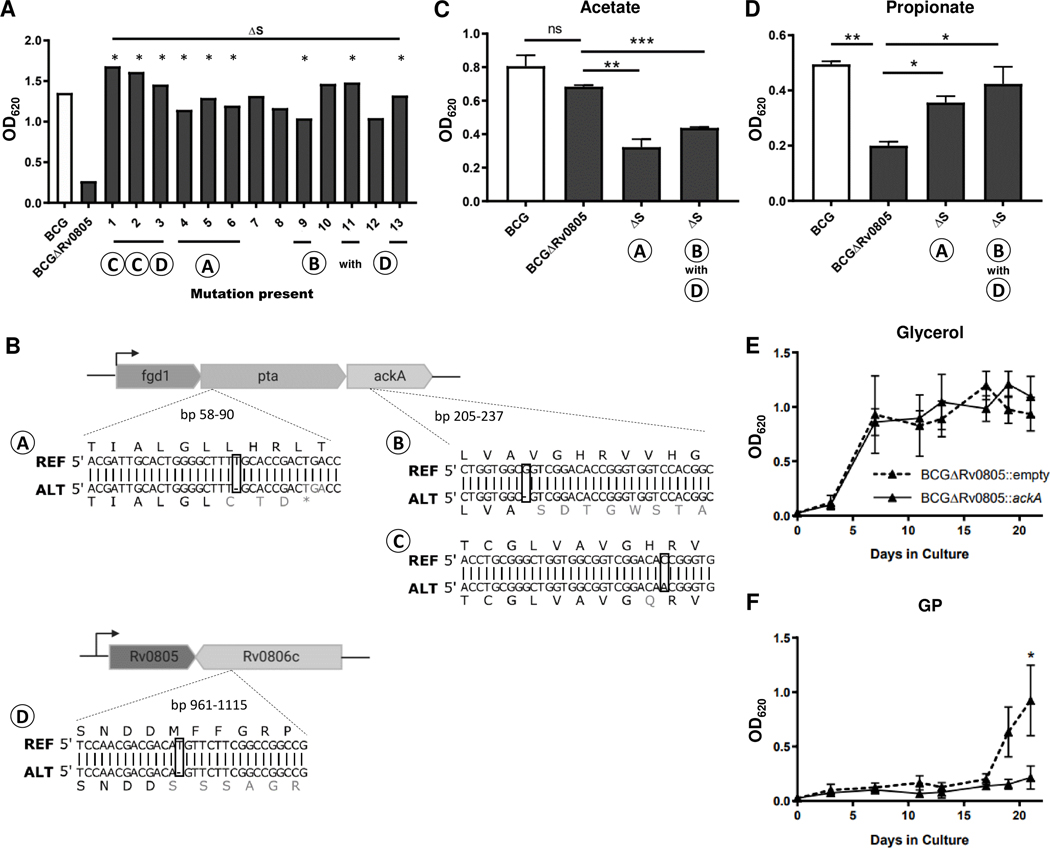

Bacteria from 13 selected colonies continued to suppress the growth delay phenotype upon re-exposure to GP, and we refer to these isolates as BCGΔRv0805 suppressor mutants (ΔS) and catalogued them numerically (Fig 5A). Whole genome sequencing (WGS) performed on genomic DNA (gDNA) from 9 of these ΔS colonies identified four mutations when compared to parental BCGΔRv0805 (Table 1, Fig. 5B). These mutations occurred in pta (BCG_0447, Rv0408), ackA (BCG_0448, Rv0409), or cpsY (BCG_0858c, Rv0806c). All these genes are identical between BCG and H37Rv, so the Mtb orthologues are used as default for simplicity. All ΔS mutations were found alone except the G deletion within ackA at nt524877 (mutation B), which occurred with mutation D in Rv0806c (Fig. 5A, B). A separate ΔS mutation at nt524887 within ackA introducing an H74Q variation (mutation C) occurred alone. Pta and ackA are present in a putative operon with fgd1 in TB complex mycobacteria and their products catalyze the reversible conversion between acetyl-CoA and acetyl-phosphate (Fig. 3A) [60]. Spontaneous mutations in the pta-ackA operon of ΔS strains reduced growth relative to BCGΔRv0805 when acetate was the primary carbon source, consistent with disruptions in the Pta-AckA pathway (Fig. 5C). However, these mutants grew better than BCGΔRv0805 on propionate as a primary carbon source (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5: Mutations within acetate metabolic genes and Rv0806c are associated with suppression of BCGΔRv0805 phenotype.

(A) BCG, BCGΔRv0805, or BCGΔRv0805 suppressor isolates were grown to 7 days in GP. BCGΔRv0805 displayed its characteristic growth defect, while BCGΔRv0805 strains with suppressor mutations (ΔS) clones 1–13 displayed WT like growth. BCG and BCGΔRv0805 are representative of 3 independent experiments. * above isolate indicates those that were sequenced. (B) Schematic showing the fdg1-pta-ackA locus (Rv0407-Rv0409, BCG_0446-BCG_0448) or Rv0805-Rv0806c (BCG_0857-BCG_0858c). Base and amino acid changes associated with each of the four mutations are highlighted beneath schematic for affected locus. Each mutation is boxed. REF refers to BCG reference genome while ALT indicates mutant sequence. BCG, BCGΔRv0805, and ΔS isolates were grown to day 7 in 7H12 supplemented with 10 mM acetate (C) or propionate (D). Notably these isolates displayed less growth on acetate (C) as primary carbon source as they have mutations within acetate metabolic genes but grew better than the KO on propionate. (E and F) Growth of BCGΔRv0805 expressing an empty or ackA containing overexpression vector were grown in glycerol (E) or GP (F). Data shown are from at least 2 independent experiments. Error bars denote SD. *, P <0.05; **, P <0.01; ***, P <0.001.

Table 1:

Summary of mutational analysisa

| Genome Position AM408590.11 | Protein description | Mutation name | Ref | Alt2 | Present in | % Alt3 | Result | Colony morphology4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 522673 BCG_0447 (Rv0408), pta | Phosphate acetyltransferase; Interconversion of acetyl-phosphate and acetyl-CoA | A | CTTTT | CTTT | ΔS 4–6 | 86.15, 88.54, 85.85 | Stop codon 87 bp into ORF | Small |

| 524877 BCG_0448 (Rv0409), ackA | Acetate kinase; interconversion of acetate and acetyl-phosphate | B | CGG | CG | ΔS 9,11,13 | 96.35, 89.17, 88.82 | Stop codon 276 bp into ORF | Large |

| 524887 BCG_0448 (Rv0409), ackA | Acetate kinase; Interconversion of acetate and acetyl-phosphate | C | CAC | CAA | ΔS 1,2 | 100,100 | H74Q | Normal |

| 930778 BCG_0858c (Rv0806c), cpsY | UDP-4 glucose epimerase | D | CA | C | ΔS 3,9,11,13 | 70, 94.68, 91.24, 96.88 | Stop codon 1107 bp into ORF | 3: Normal 9,11,13: Large |

gDNA from all BCG, BCGΔRv0805, or BCGΔRv0805 suppressor mutants (ΔS) was sequenced by the Wadsworth sequencing core.

WGS sequences were aligned to BCG reference genome AM408590.1 by Dr. Erica Lasek-Nesselquist.

All SNPs/INDELs are present only in BCGΔRv0805 suppressor mutants, compared to BCG and BCGΔRv0805.

All SNPs are supported by ≥ 40 reads depth and ≥ 85% or reads that support alternative (Alt) allele compared to reference allele (Ref), expect for ΔRv0805 C isolate (70%).

Colony morphology was determined by size of suppressor colony compared to non-GP passaged BCGΔRv0805 colonies.

ackA mutations occurred in two independent biological experiments and we reasoned that disruptions in this gene may be a dominant cause of suppression. We hypothesized that providing an additional copy of ackA would inhibit suppressor formation. Overexpression of ackA by the Rv0805 promoter extended the growth lag of BCGΔRv0805 compared to BCGΔRv0805 harboring the empty vector in GP conditions but did not affect growth in media with just glycerol as the primary carbon source (Fig. 5E, F). This result indicates that ackA expression has an inhibitory effect on BCGΔRv0805 growth in GP media and further supports an integral role of Rv0805 in metabolism. Additionally, overexpressing ackAH74Q improved growth of BCGΔRv0805 in GP compared to the ackA expressing vector (Fig. S9B). However, ackA overexpression in a ΔS with a pta frameshift did not alter the growth of the suppressor mutant in GP (Fig. S9C). This result suggests that pta expression also contributes to the growth phenotype. Together these results suggest that disruption of acetate metabolism can bypass the need for Rv0805 on GP media.

We also noted that an identical frameshift mutation in Rv0806c occurred in two independent ΔS isolates, providing support for its ability to suppress the growth arrest of BCGΔRv0805. Rv0805 has a 56-bp overlap with the convergent gene Rv0806c, which encodes a putative UDP-4-glucose epimerase. The Rv0805 deletion in the BCGΔRv0805 mutant does not alter the Rv0806c ORF. However, we considered the possibility that these two genes indirectly influence expression of one another due to their proximity. We found that BCGΔRv0805 complemented with Rv0805-Rv0806c together behaved similarly to the Rv0805-only complement with respect to growth and cytoplasmic cAMP levels, although it did not fully restore WT levels of secreted cAMP (Fig. S10).

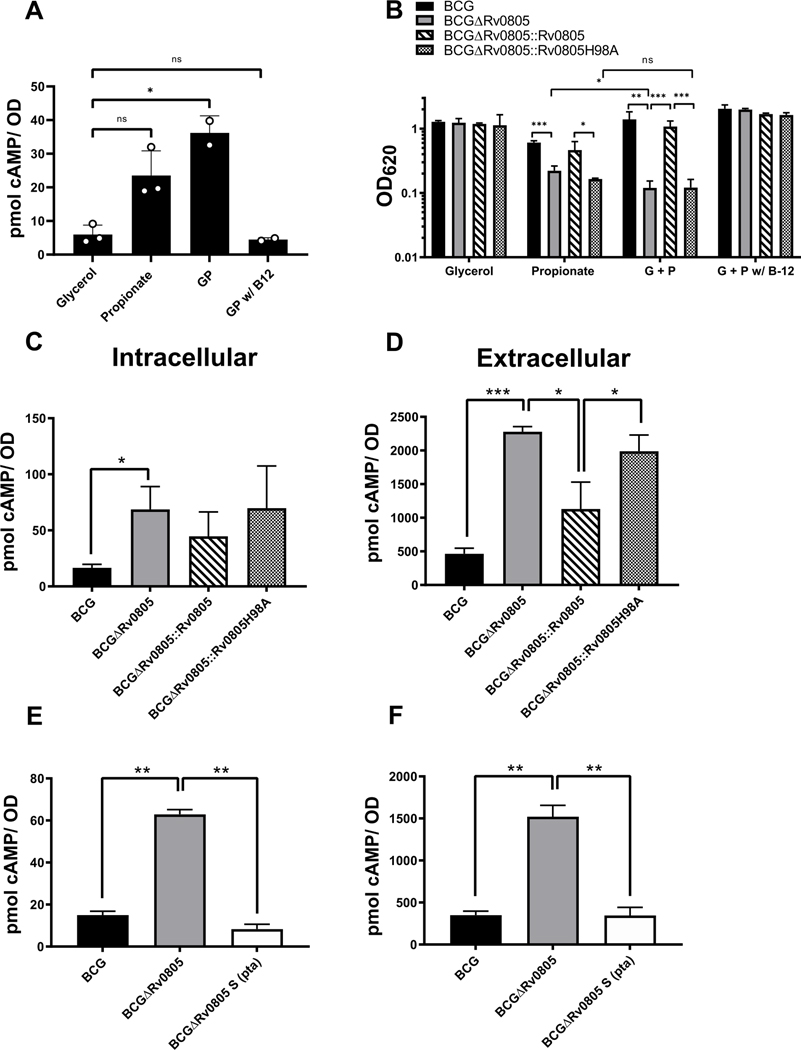

cNMP hydrolysis by Rv0805 is required for growth and cAMP homeostasis

We previously showed that cAMP levels are elevated in Mtb grown on propionate compared to glycerol and reasoned that cAMP levels could differentially affect growth [16]. cAMP levels drastically increased in WT BCG with GP compared to glycerol alone, but B12 addition restored the baseline cAMP levels found in glycerol alone (Fig. 6A). This propionate-associated cAMP increase was specific to TB complex mycobacteria, as cAMP levels in M. smegmatis were not affected by growth with glycerol versus GP (Fig. S11B). cAMP levels are higher overall in M. smegmatis than BCG for unknown reasons. Given the elevated levels of cAMP present and the relevance of Rv0805 in these growth conditions, we tested the importance of Rv0805’s cNMP catalytic activity for BCG growth. BCGΔRv0805 complemented with Rv0805H98A, which is defective for cAMP and 2’,3’-cNMP hydrolysis (Fig. S1) [39, 41], phenocopied BCGΔRv0805 in propionate and GP conditions. This result indicates that Rv0805 cNMP PDE activity is critical for BCG growth on propionate (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6: Rv0805 cNMP catalysis is required for growth and cAMP levels are restored by ΔRv0805 genetic suppression.

(A) Intracellular cAMP from WT BCG grown St/Amb in 7H12 with indicated carbon sources [glycerol (10 mM), propionate (10 mM), GP (both 10 mM) or, GP with 10 μg/mL B12]. (B) To determine if a propionate dependent metabolic defect contributed to Rv0805 dependent growth defects, 10 μg/mL B12 was added. Addition of B12 restored growth of BCGΔRv0805 (OD620 measured at day 13). All conditions were compared simultaneously in the same experiment at least once. Two additional biological repeats for propionate and GP are replotted from Fig. 2D or Fig. S7A, respectively. (C and D) Intracellular (C) and extracellular (D) fractions of cAMP measured from BCG strains grown to day 7 in GP media. (E and F) Intracellular (E) and extracellular (F) fractions of cAMP measured from BCG, BCGΔRv0805, or BCGΔRv0805 ΔS pta frameshift strains grown to day 7 in GP media were compared. Data shown are from at least 2 independent experiments. Error bars denote SD. *, P <0.05; **, P <0.01; ***, P <0.001. One sample from BCG WT in panel A was reanalyzed and used for comparison against BCGΔRv0805 samples in panel C, they were grown in the same experiment.

BCGΔRv0805 displayed higher cAMP levels than WT BCG had in both the secreted and bacteria-associated cAMP fractions when grown in GP media (Fig. 6C, D). Complementation with a WT copy of Rv0805 restored basal WT levels of cAMP in the secreted fraction. However, intracellular cAMP levels were variable and not fully complemented by WT Rv0805. The Rv0805H98A-complemented strains behaved like the Rv0805 KO strain in both intracellular and extracellular cAMP levels, thus cAMP levels of BCGΔRv0805 were not restored by Rv0805H98A complementation. There was no effect of Rv0805 in regulating cAMP levels when BCG or H37Rv was grown on glycerol (Fig. S12). As with BCG, cAMP levels increased in H37RvΔRv0805 relative to WT on propionate as a primary carbon source, but this phenotype was only partially complemented by ectopic Rv0805 expression (Fig. S12). These results indicate a conditional role of Rv0805 in regulating cAMP levels.

cAMP hydrolysis is only partially responsible for Rv0805-dependent growth defect

cAMP levels were next measured in the frameshifted pta suppressor mutant, which was found to have WT levels of cAMP (Fig. 6E, F). This restoration to WT cAMP levels in the suppressor mutant occurred despite the Rv0805 deletion. B12 treatment, which rescued growth of BCGΔRv0805 in GP media, also restored cAMP levels from BCGΔRv0805 grown in GP media to the levels observed in glycerol alone (Fig. S13).

We then addressed the role of cAMP levels in the BCGΔRv0805 growth phenotype by overexpressing Rv1339, which has been recently presented as a novel mycobacterial cAMP PDE [36]. The Rv1339 ORF was expressed as annotated or without an N-terminal sequence (MRRCIPHRCIGHGTV) that is not present in several other homologs (Fig. S14A). Some reports indicate that Rv1339 is expressed as a leaderless transcript that lacks this N-terminal sequence, despite the sequence being present in multiple genome annotations [60, 61]. The N-terminal truncated version is referred to as Rv1339-NTT. Deletion of the Rv1339 orthologue in M. smegmatis (MSMEG4902) increased cAMP levels in M. smegmatis in a preliminary experiment (Fig. S14B), and overexpression of either Rv1339 or Rv1339-NTT significantly reduced cAMP levels in the M. smegmatis mc2155 knockout strain (Mc2155 Δ4902) (Fig. S15A,B). Rv1339 overexpression also depleted BCG cAMP levels ~10 fold in every condition tested (Fig. 7A, B; Fig. S15C). Together these results confirm that Rv1339 is a robust cAMP PDE that can efficiently deplete cAMP levels. The activity of Rv1339-NTT was reduced compared to WT Rv1339 when expressed in BCGΔRv0805 (Fig. 7B), suggesting that the role of the N-terminal sequence in TB complex bacteria warrants further consideration.

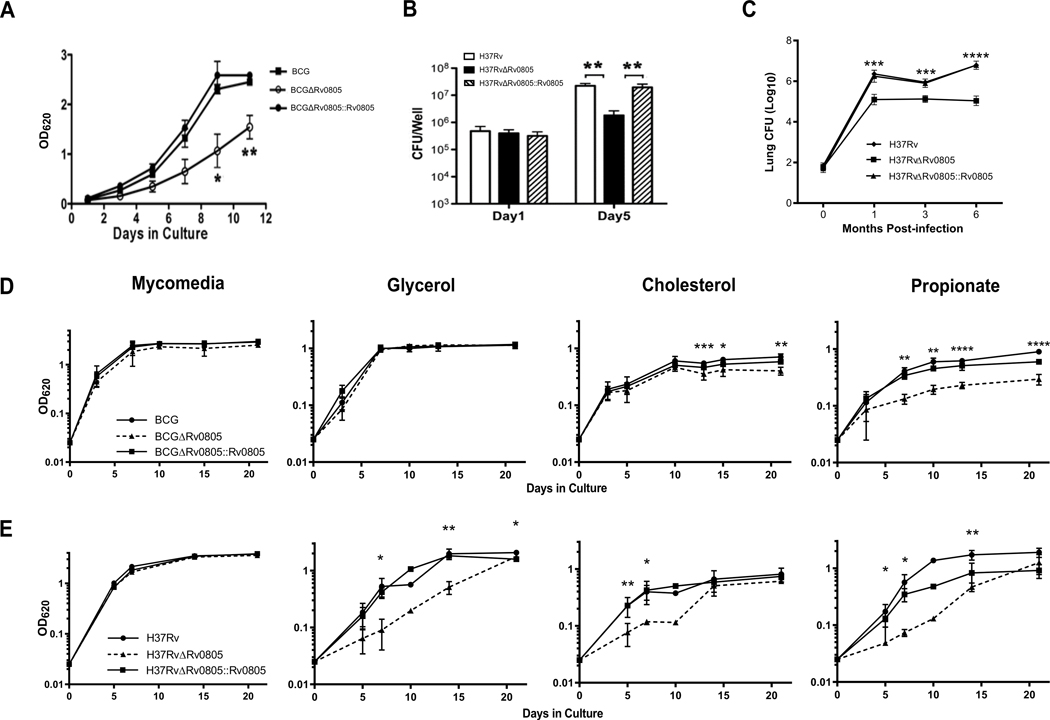

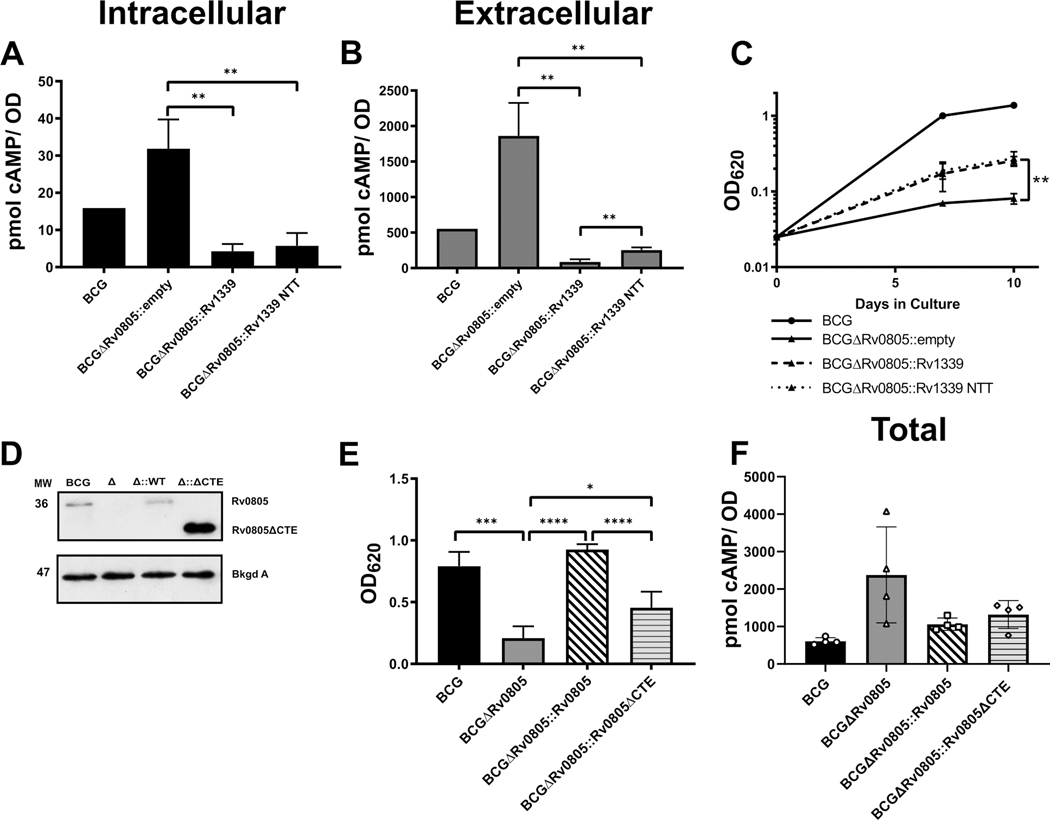

Figure 7: Partial growth increase by depletion of cAMP by Rv1339 overexpression suggests an importance of Rv0805 localization (A and B).

Effect of overexpressing Rv1339 or Rv1339-NTT on intracellular (A) and extracellular (B) cAMP levels in BCGΔRv0805 grown to 10 days in GP. (C) Comparison of growth between BCG and BCGΔRv0805 containing either empty or Rv1339 overexpressing constructs. (D) Western blot to confirm the truncation of Rv0805 CTE (removal of G279-D318). (E) Role of Rv0805 CTE in bacterial growth in GP media. (F) comparison of total (intracellular + extracellular) cAMP levels of WT BCG, BCGΔRv0805, BCGΔRv0805::Rv0805, and BCGΔRv0805::Rv0805ΔCTE. Error bars represent SD. *, P <0.05; **, P <0.01

We found that decreasing cAMP levels by Rv1339 overexpression increased BCGΔRv0805 growth on GP (Fig. 7C) but had no effect on growth of bacteria in glycerol alone (Fig. S15D). The growth improvement of BCGΔRv0805 on GP with Rv1339 overexpression was only ~20% that of WT BCG despite a reduction of cAMP to WT levels (Fig. 7A–C). In contrast, Rv0805 complementation restored ~90% of WT growth with only a minor reduction in cAMP levels (Figs. 6B–D, 7E, F). Together these results indicate that the importance of Rv0805-mediated cNMP hydrolysis for bacterial growth in GP media is more specific than a generalized need to reduce total levels of cAMP.

We reasoned that spatial and temporal factors could affect cAMP function in the complex signaling system of TB complex mycobacteria. Previous work showed that the Rv0805 CTE is required to localize Rv0805 to the mycobacterial membrane [42]. Therefore, we asked if Rv0805 localization is required for its biological role by generating a CTE truncation of Rv0805 (Rv0805ΔCTE) and tested its ability to complement the BCGΔRv0805 growth phenotype. Rv0805ΔCTE was expressed in BCGΔRv0805 at the expected size and at greater levels than the WT Rv0805 complement (Fig. 7D). Rv0805ΔCTE complementation of BCGΔRv0805 produced a partial growth rescue in GP media (Fig. 7E) and slightly elevated cAMP levels compared with those observed in bacteria complemented with the full-length Rv0805 (Fig. 7F). Our results suggest that the CTE of Rv0805 is crucial for its biological function and raise the possibility that proper localization is required for Rv0805 function. While PDE-mediated cAMP hydrolysis influences bacterial growth in high cAMP producing conditions, our results suggest that properly targeted catalytic activity is also required for Rv0805’s biological function.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies that focused on the presence of non-catalytic roles for Rv0805 and its modest cAMP cleavage activity in vitro raised questions about the importance of cNMP hydrolysis to Rv0805 function in TB complex mycobacteria [39–42]. The present study shows that Rv0805 has a central role in the biology of TB complex mycobacteria and that Rv0805’s ability to hydrolyze cNMPs is essential for bacterial growth in conditions that involve propionate metabolism. Rv0805 was also required for growth of Mtb within macrophages, and on cholesterol as a primary carbon source. While these results specifically demonstrate a critical role for Rv0805 in cAMP homeostasis in host-associated conditions, we found that additional unknown Rv0805 activities are also needed for bacterial growth in the combined presence of propionate and glycerol.

Rv0805 has alternative substrates

Our in vitro results showing that Rv0805 hydrolytic activities are significantly higher for 2’, 3’-cNMPs than their 3’, 5’-cAMP and cGMP counterparts are consistent with those of others (Fig. 1D, F) [39, 41]. CpdAEc and Myxococcus xanthus PDEs PdeA and PdeB hydrolyze both 2′, 3′-cAMP and 3′, 5′-cAMP ((Fig. 1) and [62]), suggesting that this activity is broadly distributed among bacteria. The roles of 2′, 3′-cyclic nucleotides and their PDEs are poorly understood, but they range from osmotic adaptation and virulence gene expression to biofilm formation [51, 62–68]. RNaseA produces 2’, 3’-cNMPs through the degradation of RNA in E. coli [51], and the possibility that Rv0805 hydrolyzes 2’, 3’-cNMPs in response to RNA damage in TB complex mycobacteria warrants further investigation.

Our finding that Rv0805 possesses GDPD activity raises the additional possibility that Rv0805 has biologically important catalytic roles other than cNMP cleavage in pathogenic mycobacteria. Gly3P generated by GDPDs can feed glycolytic, gluconeogenic and lipid synthetic pathways [69], and loss of GDPD activity associated with GlpQ in Mycoplasma pneumonia reduces their cytotoxicity toward HeLa cells [70]. Glycerol kinase, GlpK, which phosphorylates glycerol to form Gly3P, facilitates in vitro growth of Mtb on glycerol, but is not needed for growth in mice [71]. It is possible that the GPDP activity of Rv0805 provides an alternative catabolic pathway for generation of Gly3P during infection. We noted that Rv0805 deletion in H37Rv, but not BCG, results in lagged growth in glycerol (Fig. 2D,E), and reason that dispensability of Rv0805 for BCG grown on glycerol alone could be due to redundancy of glycerol utilization paths. BCG has two copies (BCG_3331c and BCG_3367c) of glycerol dehydrogenase (GlpD2), an essential enzyme for in vitro growth and glycerol utilization that catalyzes the reaction of Gly3P to dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP)[69, 72]. BCG also has a functional glycerol kinase (GlpK), which phosphorylates glycerol to form Gly3P, while many Mtb strains have reversible frameshift mutations in glpK [73].

It is not clear why the Rv0805H98A mutation increased GPDE activity. Rv0805 has an open active site with side chains that interact with phosphate moieties, which may be a major determinant of substrate specificity [41]. H98 interacts with the phosphodiester bond of substrates and is postulated to stabilize the leaving group once the bond is broken. It is possible that Rv0805H98A has an altered open site that allows for faster release of the product.

Rv0805 cNMP PDE activity is important for bacterial growth on propionate

Addition of glycerol improved the growth of WT BCG (Fig. 3B, Fig. 6A) but did not relieve the growth defect of BCGΔRv0805 on propionate. This suggests that the Rv0805 mutation reduces the ability of the bacteria to use the glycerol to mitigate propionate-associated toxicity. Our data suggest that Rv0805 facilitates Mtb growth on propionate by an ICL-independent pathway. ITA is a physiologically relevant stressor produced by macrophages in response to Mtb infection that limits intracellular growth of Mtb by inhibiting ICL activity [58]. We found that all Mtb strains, including the Rv0805 mutant, were further impaired for growth when ICL was inhibited with ITA (not shown), suggesting that Rv0805 facilitates alternative means of propionate detoxification during infection. Additionally, glycerol feeds TAG production in mycobacteria [74, 75], and we are exploring the possibility that Rv0805 contributes to this propionate detoxification pathway. The decreased pHi that occurred with the addition of GP is consistent with other reports [59]. However, the occurrence of this reduced pHi was independent of Rv0805 (Fig. S6), indicating that additional factors are required for the inhibition of BCGΔRv0805 growth in GP media.

cAMP levels were also elevated in bacteria grown on GP relative to those of bacteria grown in glycerol or propionate alone (Fig. 6A). Dysregulation of these cAMP levels in BCGΔRv0805 relative to WT BCG establishes the importance of Rv0805 for modulation of cAMP levels in conditions that require metabolism of propionate (Fig. 6C, D). In addition, the Rv0805H98A-complemented mutants showed that cNMP hydrolytic activity of Rv0805 is essential for both controlling cAMP levels and facilitating bacterial growth of BCG on GP (Fig. 6B–D). These data do not rule out the possibility that Rv0805 hydrolysis of additional cNMP substrates other than cAMP contributes to these phenotypes, and the importance to Mtb biology of 2’,3’ cNMP cleavage by Rv0805 warrants investigation.

While these results indicate that Rv0805 modulates both growth and cAMP levels in TB complex mycobacteria, the relationship between total cAMP levels and bacterial growth is unclear. For example, reduction of total cAMP levels in BCGΔRv0805 to below those of WT BCG by overexpressing Rv1339 had only a small impact on BCGΔRv0805 growth (Fig. 7A–C). Similarly, Rv0805 complementation fully restored BCGΔRv0805 growth despite only partial reduction of cAMP levels (Fig. 6B–D).

Suppression of growth inhibition may be due to bypass of cAMP induction

Addition of B12 or disruption of the pta-ackA operon similarly rescued growth of BCGΔRv0805 and both caused a striking restoration of cAMP levels to those observed in the presence of glycerol only (Fig. S13; Fig. 6A, E, F). It is not known whether B12 and the products of the pta-ackA operon rescue growth by distinct or overlapping mechanisms, but it seems likely that both pathways bypassed the propionate-associated cAMP burst. B12 could rescue growth of BCGΔRv0805 by detoxification of propionyl-CoA intermediates through methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (MutAB) [46, 47, 59]. However, additional B12 functions in mycobacteria that cannot be formally excluded include its ability to activate methionine synthase, MetH and ribonucleotide reductase, NrdZ, both of which have roles in nucleotide metabolism [76–78]. Rv1819c has recently been described as a B12 transporter that may enable Mtb to scavenge B12 during infection [79, 80], so these results may have in vivo implications.

The mechanism of genetic suppression achieved by the pta-ackA mutations is also unclear but may involve an imbalance of acetyl-CoA and/ or propionyl-CoA levels. Pta-AckA and acetyl-CoA synthase (ACS, Rv3667) provide alternative pathways to convert acetate to acetyl-CoA, a precursor for the TCA cycle and fatty acid metabolism [81]. Mtb ACS can produce propionyl-CoA as well as acetyl-CoA [81], but it is twice as active on acetate as propionate [81]. Rv0998, a cAMP dependent lysine acetyltransferase, inactivates ACS through acetylation or propionylation and may dampen the effects of propionate-associated toxicity by limiting the generation of propionyl-CoA [23, 82]. Products of the pta-ackA operon act on propionate as well as acetate in other bacteria [83]. The increased GP-associated growth defect that occurred with overexpression of ackA in BCGΔRv0805 suggests that ackA expression increases propionate toxicity (Fig. 5C, F). An additional possibility is that mutations in the pta-ackA operon result in dysregulated acetyl-phosphate levels, altering acetylation or phosphorylation of the proteome [84, 85]. Acetyl-phosphate has been shown to acetylate DosR and to be growth inhibitory, likely due to altered signal transduction [86, 87].

The metabolic impacts of Rv0805 catalytic activity and mechanisms underlying its importance to the interactions between cAMP and propionate metabolism require further characterization. We also previously showed that propionate increases cAMP levels in Mtb [16], but not in M. smegmatis (Fig. S11B), and propose that Rv0805 is part of a cAMP-modulated propionate response pathway that is specific to pathogenic mycobacteria. Identification of the AC responsible for propionate-dependent cAMP production will help to define this signaling pathway, which may involve one or more of six ACs that are present in Mtb but not M. smegmatis [17]. V-58, a potent stimulator of cAMP production by the AC Rv1625c, inhibits Mtb growth on cholesterol or propionate [16, 25]. Another Rv1625c agonist, V-59, disrupts cholesterol metabolism by inhibiting the breakdown of cholesterol sidechains through an unknown mechanism [10]. Inducible production of cAMP similarly disrupted cholesterol metabolism but yielded disparate transcriptomic effects compared to V-59 treatment [10], indicating again that total cAMP levels alone do not dictate physiologic responses. Acetate rescues V-58 mediated Mtb growth inhibition without a reduction in total cAMP levels [16], like the phenomenon we observed with Rv0805 complementation of BCGΔRv0805 (Fig. 6C). While acetate failed to rescue the BCGΔRv0805 growth defect on propionate (Fig. S4C), both cases involve propionate-associated impacts on both bacterial growth and cAMP levels in TB complex mycobacteria that warrant further investigation.

Rv1339 as additional cAMP PDE

The validation of Rv1339 activity in TB complex mycobacteria addresses a long-standing question regarding the presence of PDEs other than Rv0805 in mycobacteria [12, 17, 50, 88]. In contrast to Rv0805, which is found only in pathogenic mycobacteria, Rv1339 is conserved across pathogenic and non-pathogenic mycobacteria (Fig. S14A). Further study is needed to determine the significance of Rv1339 to cAMP signaling in mycobacteria and whether it has a broad role in modulating total cAMP levels that contrasts with the specialized activity of Rv0805 in pathogenic mycobacteria. The ability of both Rv1339 and Rv0805 to hydrolyze cAMP in vivo, but not be functionally interchangeable indicates that they serve separate roles in mycobacteria and is consistent with the possibility of localized regulation of cAMP levels by Rv0805. Future studies should consider the possibility that Mtb has additional PDEs that provide specificity to Mtb’s complex cAMP regulatory network.

Rv0805 localization may contribute to its activity

Rv0805 subcellular localization could contribute to its function, as Rv0805ΔCTE did not fully complement growth of BCGΔRv0805. Previous work has focused on Rv0805’s ability to interact with the mycobacterial membrane, which may serve to localize its catalytic activity [41, 42]. The non-structured CTE of Rv0805 is a key mediator of Rv0805 localization [42], and purified Rv0805ΔCTE has been shown to have catalytic activity equivalent to that of WT Rv0805 [41, 42]. Our finding that the CTE of Rv0805 is required for bacterial growth on GP media suggests that subcellular localization contributes to Rv0805 function in TB complex mycobacteria, and this warrants further consideration. It is also possible that the CTE modulates a critical activity other than localization or that the very high levels of Rv0805ΔCTE overexpression contribute to the growth defect in the Rv0805ΔCTE-complemented strain. However, expression of Rv0805ΔCTE did not affect BCG growth in glycerol media, suggesting that its expression alone is not toxic (data not shown). The higher levels of the truncated Rv0805 we observed by western analysis are consistent with reports that the CTE of Rv0805 negatively regulates its stability in vitro and its steady state levels in M. smegmatis [41, 42]. We did not observe decreased cAMP levels with overexpression of Rv0805ΔCTE in BCGΔRv0805 (Fig. 7F), which differs from results reported by others when Rv0805ΔCTE was overexpressed in M. smegmatis [42]. This variation may be due to differences in media compositions, cAMP production between M. smegmatis and TB complex organisms, or expression of the PDE.

Together, these findings support a model in which Rv0805 cNMP activity modulates levels of cAMP and maintains bacterial growth during propionate-induced stress (Fig. 8). We propose that Rv0805 selectively targets a localized pool of cAMP, or cAMP that is produced by only a subset of ACs to regulate a specific metabolic pathway, to explain the discordance between growth phenotypes and total cAMP levels. This model of local cAMP control by Rv0805 suggests sequestration of distinct regions or pools of cAMP to allow for signaling fidelity in Mtb [16]. PDE activity contributes to the specificity of cAMP signaling in eukaryotic cells by restricting cAMP to pools surrounding the ACs that produce it, establishing peripheral zones of low cAMP that insulate distally located cAMP effectors [89]. Multiple PDE inhibitors are required to affect global cAMP levels in mammalian cells and a combination of select PDE inhibitors is needed to increase total levels of cAMP because each PDE impacts only a local cAMP pool [90]. In addition to our finding that multiple PDEs are functional in pathogenic mycobacteria, we propose that the subcellular localization of ACs or the presence of the universal stress protein (USP), Rv1636, that tightly binds cAMP [14, 17, 18] could contribute to the specificity of cAMP signaling by modulating access to specific cAMP effector proteins. Rv0805 could serve as an additional mechanism to sequester local cAMP levels rather than regulate total cAMP levels, as our results suggest that Rv0805 and Rv1339 regulate separate pools of cAMP and their associated pathways.

Figure 8: Proposed model of Rv0805 function.

Growth on GP promotes metabolic stress in TB complex mycobacteria that results in increased levels of cAMP (depicted by star) through activation of undefined ACs (Fig. 6A, Fig. S11B). Up and down arrows above the AC represent the unknown localization (cytoplasmic or membrane associated) of the AC or ACs that are responsible for the cAMP production in GP conditions. B12 and Pta-AckA pathways have opposing effects on this metabolic stress, as B12 limited and the Pta-AckA pathway promoted cAMP levels (Fig. 6A, E, F; Fig. S13). Rv0805 localization is mediated through its CTE (represented by dotted line) [42], which may enable Rv0805 to regulate a local pool of functional cAMP or other unknown cNMP substrate/s that are modulated in response to the GP metabolic stress. The Rv0805 regulated cNMP may influence an unknown effector to respond to the GP induced metabolic stress. This signaling cascade may be overstimulated in the absence of Rv0805, or additional cNMP pathways may be turned on. The addition of B12 or disruption of pta-ackA, which both serve to lower cAMP levels, can compensate for loss of Rv0805 (Fig. 6E, F; Fig. S13). cAMP regulated by Rv0805 is secreted through an unknown mechanism (Fig. 6D). Rv1339 is an additional mycobacterial PDE described herein that can regulate other pools of cAMP (additional cAMP) and may have some overlap with the Rv0805 regulated cAMP, as growth was improved but not fully restored by overexpressing Rv1339 in BCGΔRv0805 (Fig. 7A–C). The presence of an additional PDE that is not functionally interchangeable leads to the possibilities that the cNMP regulated by each PDE serves disparate cellular fates, a phenomenon exemplified by study of eukaryotic PDEs [90], that the cognate substrates of Rv0805 or Rv1339 differ in vivo, or that the two PDEs are present in different regions of the bacteria. Subsequent studies to test these possibilities should focus on comparison between the subcellular distribution of Rv0805 and Rv1339 and substrate preferences of each PDE. In addition, the possibility of Rv0805 interacting with a protein complex, like how PDEs function within eukaryotes, can be probed through co-immunoprecipitation experiments. Image generated using BioRender.

MATERIAL & METHODS

Expression of Rv0805 and cpdA in E. coli

Mtb Rv0805 ORF was PCR amplified using primers Km961 + Km979. Sequences for all primers used in study are listed in Table S1. The PCR product was subcloned into pET28a(+) vector (Novagen) between EcoRI and HindIII to generate pMBC352. Rv0805 point mutations were generated using two-step primer overlap procedure. The first amplicons were generated using primer sets Km979 + Km5536 and Km5527 + Km5537 for Rv0805N97A and Km979 + Km5538 and Km5527 + Km5539 for Rv0805H98A. Amplicons were joined using Km979 and Km5527. The mutant Rv0805 ORFs were subcloned into pET28a(+) at EcoRI and HindIII to generate pMBC2190 (Rv0805H98A) and pMBC2234 (Rv0805N97A). The cpdAEc ORF was PCR amplified with primers Km1690 + Km1691 using E. coli W3110 strain as a template. The PCR product was subcloned into pET28a(+) between BamHI and HindIII to generate pMBC694. pMBCs 352, 694, 2190 and 2234 were sequence verified and maintained in E. coli BL21(DE3). The expression of Rv0805 and CpdAEc were induced with 1 mM IPTG for 3 hr to 18 hr at 37ºC. The His-tagged Rv0805 and CpdAEc were purified using a HisTrap column (Amersham Biosciences) [28] or a hand-packed Ni-NTA column. Protein concentration was measured with a NanoOrange Protein Quantitation Kit (Molecular Probes) or by densitometry compared to a BSA standard curve.

Hydrolysis of bis-p-nitrophenyl phosphate (BnPP)

Reaction mixtures (100 μl) containing 50mM Tris-HCl at specified pH, 10 mM NaCl, 5 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 mM metal ion, 2 mM bis-p-nitrophenyl phosphate and 0.1 μM purified protein were incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Samples were determined by measuring optical density at 405 nm (OD405). For kinetic studies 25 nM Rv0805 was incubated in 200μL reaction containing 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.5), 10 mM NaCl, 100 μM MnCl2 and varying [BnPP]. pNP was measured at 405 nm over-time. Michaelis-Menten kinetics were determined by fitting data using a non-linear regression in GraphPad Prism 6.

Hydrolysis of cyclic nucleotides

Reaction (10 μl) mixtures containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 1 mM MnCl2, 10 mM specified cyclic nucleotide, and serial dilutions of purified Rv0805 or CpdAEc protein were incubated for 1 h at 37ºC. An aliquot of each reaction was immediately spotted onto a pre-coated cellulose plate (Sigma) and was separated with solvent containing N-butanol:acetic acid:water (120:30:50). Image was taken under UV lights. 500 μM 2’,3’-cGMP or 3’,5’-cAMP were incubated with 1.5 μM of Rv0805, Rv0805H98, or Rv0805N97 containing the same reaction components as above. Reactions were incubated at 37oC for 1 hour and stopped by heat killing at 95oC. 20μL of reaction were injected on Nucleosil C-18 column and visualized at 254 nm. Chromatograms were generated using Waters software.

Hydrolysis of glycerophosphocholine

A coupled fluorometric assay described in [91] was optimized for Rv0805. Serial dilutions of Rv0805, CpdAEc, or BSA in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.14 M NaCl and 2 mM MgCl2) were incubated with a master mix of 0.5 mM glycerophosphocholine (GPC), 200 μM Amplex Red, 2 U/mL HRP, reaction buffer to desired volume; 1:1. Reactions were incubated at RT for two hours and fluorescence was detected at 590 nm using a Tecan Infinite plate reader.

Growth of bacteria and macrophages

Mtb H37Rv and recombinant M. bovis BCG (Pasteur strain, Trudeau Institute) were grown in Mycomedia [Middlebrook 7H9 supplemented with 0.5% glycerol, 10% oleic acid-albumin-catalase-dextrose (OADC), 0.05% Tween-80] [92] or 7H12 media [Middlebrook 7H9 with 0.1% casamino acids, 100 mM 2-morpholinoethanesulfuric acid (MES) pH 6.6, 0.05% tyloxapol] [25] with glycerol (10 mM), cholesterol (100 μM), propionate (10 mM) or both glycerol and propionate (10 mM of each), as primary carbon sources (as indicated in figures) or on Middlebrook 7H10 agar (Difco) supplemented with 10% OADC, and 0.01% cycloheximide. Fresh cultures were inoculated from single use frozen stocks for every experiment [93]. Bacteria were typically used after 7 days of growth, unless otherwise specified. Cultures were grown at 37oC under shaking or standing conditions and ambient air (as indicated in figures), Sh/Amb or St/Amb, respectively. Grown “in” or “on” are used interchangeably to describe liquid media grown bacteria. Grown “on plates” indicates bacteria were plated and grown on agar. In all cases 7H12 followed by a carbon source indicates that the media used was 7H12 containing that carbon source. Instances where just glycerol, cholesterol, propionate, or GP are listed indicate that these were the carbon sources present in 7H12 media.

Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani broth or on Luria-Bertani agar plates. Kanamycin at 25 μg/ml or hygromycin at 50 μg/ml was added for recombinant strains. All cultures were grown at 37ºC.

J774.16 murine macrophage cells were maintained and passed twice weekly in J774 medium containing Dulbecco′s modified Eagle′s medium (Gibco) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 5% NCTC109 medium (Gibco), and 1% nonessential amino acids (Gibco) as described previously [92].

Deletion of Rv0805 and complementation

The Rv0805 orthologue in BCG, BCG_0857, shares 100% sequence identity with Rv0805 from H37Rv, so Rv0805 was used interchangeably for BCG and H37Rv. Rv0805 deletion mutants were generated and complemented using methods as we previously reported [27]. The Rv0805 upstream fragment was amplified with Km1683 + Km1684 (with NotI ends) and the downstream fragment was amplified with Km2069 + Km2670 (with PflMI ends) using Mtb genomic DNA as a template. The two homolog fragments were sequentially subcloned into pMBC851 at NotI and PflMI, respectively, sequencing verified, and was designated as pMBC883. This plasmid was linearized with PacI and ligated with PacI-digested shuttle phasmid phAE159 (kindly provided by Dr. William Jacobs) [94]. The ligation mixture was packaged using MaxPlax lambda packaging extracts (Epicentre Biotechnologies) and transduced into E. coli HB101. Phasmid DNA (designated as pMBC916) was prepared from hygromycin-resistant colonies and transformed into M. smegmatis mc2155. Phages were prepared as earlier reports [95, 96]. Mtb and M. bovis BCG grown at log phase were infected with high titer phages [95]. Rv0805 mutants in both Mtb and M. bovis BCG were screened by PCR with primer pairs Km825 + Km2491 and Km2085 + Km826. The deletion of Rv0805 was further confirmed by Southern blot. In the mutants, the region from 19- to 622-bp of the Rv0805′s ORF was replaced with a hygromycin resistance marker. Rv0805 was not completely removed to keep the downstream gene cpsY (Rv0806c) intact as their ORFs have a 56-bp overlap.

To complement the ΔRv0805 mutants, Mtb Rv0805 promoter and ORF was amplified with primers Km2601 + Km961 and was cloned into pMBC409 at HindIII to generate pMBC1038. Rv0805H98A complement was generated using the same mutagenized primers as above (H98A: Km5538, 5539) but paired with Rv0805 forward and reverse primers Km2601 and Km5527, respectively. The mutant Rv0805 regions were cloned into pMBC409 at HindIII to generate pMBC2159 (Rv0805H98A). A CTE truncated version of Rv0805 (removal of G279-D318) with a stop codon after P278 was amplified using Km6081 + Km6082 and ligated into pMBC409 at HindIII to generate pMBC2359 (Rv0805ΔCTE). A full-length Rv0805-Rv0806c fragment containing the upstream regions of both genes was amplified using Km6240 + Km6241 and Km6242 + Km6243 and HIFI assembled into HindIII digested pMBC409 following NEB protocol to generate pMBC2378 (Rv0805-Rv0806c). These integrative plasmids were transformed into the ΔRv0805 mutants of M. bovis BCG and Mtb (pMBC1038, 2159 only), respectively.

Growth curves

WT, ΔRv0805, ΔRv0805::Rv0805, ΔRv0805::Rv0805H98A (BCG only) strains of both Mtb and M. bovis BCG were seeded at 0.025 OD620 from frozen stocks and grown in Mycomedia or 7H12 media supplemented with different primary carbon sources at various concentrations (see figure legends for specifics) within flasks by Sh/Amb or St/Amb at 37ºC. A threshold for inhibitory effects of propionate on BCGΔRv0805 was found to be 10 mM, but lower amounts were less growth inhibitory (Fig. S5). H37RvΔRv0805::Rv0805H98A was excluded from study due to the discovery of an additional SNP in this strain at the time the experiments were being performed. Samples of 100 μl were withdrawn and were diluted with corresponding media in a 96-well plate for each time point. The growth phase was determined by measuring OD620 with a microplate reader (Tecan).

Infection of macrophages

J774.16 macrophages were seeded at 1×105 cells/ml in 6-well plates. Macrophages were infected with Mtb at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 bacteria per macrophage. After 4 h of infection, cells were rinsed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before replaced with complete DMEM media. Plates were then incubated for 1 or 5 d at 37ºC with 5% CO2. The cells were finally lysed with 0.5% triton X-100 and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate for 2–3 min, and aliquots of dilutions were plated on Middlebrook 7H10 plates for colony forming units (CFUs) as described [97].

Mouse infection with Mtb

Eight-to-ten-week-old female C3HeB/FeJ and C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Lab) were used in all experiments following procedures as previously described [98]. The bacterial stocks of all three strains of Mtb studied in the low dose aerosolization murine experimental TB model, including Mtb H37Rv WT, MtbΔRv0805, and the complemented strain (H37RvΔRv0805::Rv0805) had been animal-passaged to maintain virulence. The resulting stocks were stored in aliquots at −80°C until use. At the time of the experiment, the Mtb stocks were diluted to a concentration, based on pre-calibration experiments, that is suitable for delivering 50–100 colony forming units (CFU) into the lungs of mice via aerosols. At the desired time intervals post-aerosolization, lungs were homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 80, and the inoculum size determined via plating serial dilutions of the homogenates onto plates of 7H10 agar (Difco) supplemented with 0.5% glycerol and 10% oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase (OADC) enrichment (Becton Dickinson). All experiment included a group of 8–10-week-old C57BL/6 female mice that were used for the enumeration of the infection inoculum at 16–24 hours post-infection. All mice were housed in a biosafety-level-3 (BSL-3) animal laboratory and maintained pathogen-free by routine serological and histopathological examinations. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Albert Einstein College of Medicine have approved the animal protocols used in this study. All experiments involving manipulation of Mtbwere conducted in a BSL-3 environment following protocols that have been approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee.

Construction of overexpression strains

The region upstream of Rv0805 was PCR amplified using primers Km1000 + Km1001, from a H37Rv gDNA template and placed in integrative mycobacterial expression vector pMBC409 to form pMBC2353. ackA, Rv1339, or Rv1339 with an N-terminal truncation (Rv1339-NTT) were amplified from a H37Rv gDNA template using Km6140 + Km6141, Km6149 + Km6150, or Km6150 + Km6151, respectively. All fragments were cloned with a T7 Shine-Dalgarno sequence (T7SD) cloned in front of the ORF and each fragment was cloned downstream of the Rv0805 promoter in the integrative construct pMBC2353. ackAH74Q was amplified from gDNA of BCGΔRv0805 suppressor mutant that had ackAH74Q mutation using Km6140 + Km6141 and ligated into pMBC2353. These integrative plasmids were transformed into the ΔRv0805 mutants of M. bovis BCG or into M. smegmatis. See Table S2 for construct names and descriptions.

3,’5’-cAMP Radioimmunoassay

Extracellular (secreted) or intracellular (cytoplasmic) cAMP was extracted from late log phase bacteria grown in Mycomedia or 7H12 media [16]. Extraction days specified in figure legends. cAMP concentrations were measured via radioimmunoassay, which is performed though competitive binding of cAMP antibody for 125I-labeled cAMP and unlabeled cAMP from sample as described previously in [16]. Intracellular or extracellular cAMP concentrations were normalized by bacterial OD620.

Rv0805 Western blot

Protein from Mtb and M. bovis BCG was extracted late log phase cultures. Bacteria were washed with PBS/0.25% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). The bacterial pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (0.3% SDS, 200 mM DTT, 28 mM Tris/HCl, 22 mM Tris base and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail). Bacteria were lysed via sonication and freeze-thaw cycles. 100 μg of protein from lysates was separated via SDS-PAGE (5% staking gel and 12% resolving gel) at 120V until the 20 kDa molecular weight marker was run off gel. Protein was then transferred to a PVDF membrane following a standard wet-transfer protocol. Rv0805 was detected by probing the membrane with rabbit anti-Rv0805 polyclonal serum, followed by goat-anti-rabbit PolyHRP antibody (Thermo Scientific). Peroxidase signal was detected using a 10:1 mix of SuperSignal Pico and Femto Chemiluminescent substrates (Life Technologies). Background band A (bkgd A) served as a loading control.

Intracellular pH measurement

A previously described methodology [20] was optimized to monitor changes in pHi produced by altered bacterial metabolism. BCG strains (WT, ΔRv0805, ΔRv0805::Rv0805, ΔRv0805::Rv0805H98A) were grown for 3–5 days in Mycomedia St/Amb then washed with dPBS/tyloxapol and resuspended in 7H12 glycerol or GP media at 0.5 OD620 and grown for 2 days St/Amb. The pH of both medias was equivalent. ~ 1 OD620 of treated cells were washed with media of interest then loaded with 10 μM BCECF diluted in media (for experimental) or dPBS (for standard curve). Cells were loaded for 2 hours at 37oC on rolling rack, then pelleted at 6 krpm for 10 minutes and washed to remove extracellular BCECF. Experimental cells (treated and loaded with media of interest) were resuspended in 500 μL of appropriate media. Cells needed for the pHi standard curve were resuspended in 250 μL of potassium phosphate buffers (pH 5.5–7.5) containing 10μM nigericin and incubated on ice briefly before loading into plate. Plates were read at 450/530 and 485/530 excitation/emission and a ratio of the 485:450 readings was used to measure pHi of the experimental cells by referencing to a standard curve calibrated to a pH5.5–7.5 range.

Identification of BCGΔRv0805 suppressor mutants

The schematic outlining methodology is found in Fig. S8. BCG or BCGΔRv0805 were grown for 21 days in GP, at which point cells were plated for individual colonies. BCGΔRv0805 served as an unexposed control. Individual colonies were picked and recovered in Mycomedia for 5 days, then re-tested for phenotype in GP. Stocks of spontaneous mutants were made and stored at −80oC. All tested colonies from BCGΔRv0805 grown to 21 days in GP suppressed the initial growth arrest phenotype. These isolates were denoted numerically, and we noted whether each colony was small or large compared to non-GP passaged BCGΔRv0805 (see Table 1). ΔS isolates and control strains (BCG or unexposed BCGΔRv0805) were prepped for gDNA following protocol outlined in [99]. gDNA libraries were prepped using Nextera XT and sequenced on Illumina MiSeq or NextSeq platforms. Reads were trimmed for quality with the Bbduk function of Bbtools v38.86 (https://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/) or with default parameters in Seqyclean v1.10.09 (https://github.com/ibest/seqyclean) and mapped to reference genome BCG1173 (AM408590.1) in BWA v0.7.17 [100]. SNVs in ΔS were identified by SAMtools v1.10 [81, 101] and only those occurring at ≥0.85 frequency at positions supported by ≥ 40 reads were considered (Table 1). Deletion of Rv0805 in BCGΔRv0805 and INDELS in ΔS were confirmed by manual inspection of reference mapped assemblies in IGV and by interrogating de novo assemblies generated in Spades v3.8.0 [102, 103]. A ~4.6 kbp deletion within the PDIM locus was noted in all strains used, including the parental BCG. No phenotypic differences were observed between this BCG variant and BCG with an intact PDIM locus.

Passage of suppressor mutants

Passage experiments were done to determine whether BCGΔRv0805 growth recovery in GP conditions was due to phenotypic adaptation, as follows. BCGΔRv0805 was grown to 21 days in GP condition and then recovered by pelleting to remove GP media then bacteria were resuspended at 0.025 OD620 in various conditions, including: Mycomedia standing/ambient, Mycomedia shaking/ambient, 7H12 10 mM glycerol standing/ambient, 7H12 10 mM glycerol with 0.05% Tween standing/ambient, or 7H12 10 mM glycerol with 10% oleic acid standing ambient. Bacteria were grown in these conditions for 7 days, then they were pelleted and resuspended in the GP condition at 0.025 OD620 (standing/ambient) and growth was monitored at 7 days. We hypothesized that if restoration of growth was due to phenotypic adaptation, “resetting” the bacteria by growing them in non-selective conditions would disable the phenotype that enabled growth in GP.

Statistics

Unless specified otherwise, two-tailed t tests were performed using Prism 4 software to determine the significance of differences between means of various samples. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank James Dias for the cAMP-specific antisera used in our cAMP RIAs and Joseph Wade for generously providing M. smegmatisΔ4902. Damen Schaak and Jessica Cardenas provided expert technical assistance and we are grateful to Michael Berney for helpful discussions. We also acknowledge the Wadsworth Center Media and Tissue Culture and Advanced Genomic Technologies Cores for providing bacterial media and DNA sequencing, respectively.

This work was funded in part by National Institutes of Health grant R21AI134080.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pai M, et al. , Tuberculosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2016. 2: p. 16076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ehrt S, Schnappinger D, and Rhee KY, Metabolic principles of persistence and pathogenicity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2018. 16(8): p. 496–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rhee KY, et al. , Central carbon metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: an unexpected frontier. Trends Microbiol, 2011. 19(7): p. 307–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galperin MY, What bacteria want. Environ Microbiol, 2018. 20(12): p. 4221–4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorke B and Stulke J, Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria: many ways to make the most out of nutrients. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2008. 6(8): p. 613–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan MZ, et al. , Protein kinase G confers survival advantage to Mycobacterium tuberculosis during latency-like conditions. J Biol Chem, 2017. 292(39): p. 16093–16108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Hare HM, et al. , Regulation of glutamate metabolism by protein kinases in mycobacteria. Mol Microbiol, 2008. 70(6): p. 1408–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leistikow RL, et al. , The Mycobacterium tuberculosis DosR regulon assists in metabolic homeostasis and enables rapid recovery from nonrespiring dormancy. J Bacteriol, 2010. 192(6): p. 1662–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh PR, Vijjamarri AK, and Sarkar D, Metabolic Switching of Mycobacterium tuberculosis during Hypoxia Is Controlled by the Virulence Regulator PhoP. J Bacteriol, 2020. 202(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilburn KM, et al. , Pharmacological and genetic activation of cAMP synthesis disrupts cholesterol utilization in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog, 2022. 18(2): p. e1009862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shenoy AR and Visweswariah SS, Mycobacterial adenylyl cyclases: biochemical diversity and structural plasticity. FEBS Lett, 2006. 580(14): p. 3344–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson RM and McDonough KA, Cyclic nucleotide signaling in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: an expanding repertoire. Pathog Dis, 2018. 76(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonough KA and Rodriguez A, The myriad roles of cyclic AMP in microbial pathogens: from signal to sword. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2011. 10(1): p. 27–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banerjee A, et al. , A universal stress protein (USP) in mycobacteria binds cAMP. J Biol Chem, 2015. 290(20): p. 12731–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bai G, Schaak DD, and McDonough KA, cAMP levels within Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis BCG increase upon infection of macrophages. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol, 2009. 55(1): p. 68–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson RM, et al. , Chemical activation of adenylyl cyclase Rv1625c inhibits growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis on cholesterol and modulates intramacrophage signaling. Mol Microbiol, 2017. 105(2): p. 294–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bai G, Knapp GS, and McDonough KA, Cyclic AMP signalling in mycobacteria: redirecting the conversation with a common currency. Cell Microbiol, 2011. 13(3): p. 349–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knapp GS and McDonough KA, Cyclic AMP Signaling in Mycobacteria. Microbiol Spectr, 2014. 2(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agarwal N, et al. , Cyclic AMP intoxication of macrophages by a Mycobacterium tuberculosis adenylate cyclase. Nature, 2009. 460(7251): p. 98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gazdik MA, et al. , Rv1675c (cmr) regulates intramacrophage and cyclic AMP-induced gene expression in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-complex mycobacteria. Mol Microbiol, 2009. 71(2): p. 434–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ranganathan S, et al. , Characterization of a cAMP responsive transcription factor, Cmr (Rv1675c), in TB complex mycobacteria reveals overlap with the DosR (DevR) dormancy regulon. Nucleic Acids Res, 2016. 44(1): p. 134–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agarwal N, Raghunand TR, and Bishai WR, Regulation of the expression of whiB1 in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: role of cAMP receptor protein. Microbiology, 2006. 152(Pt 9): p. 2749–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nambi S, et al. , Cyclic AMP-dependent protein lysine acylation in mycobacteria regulates fatty acid and propionate metabolism. J Biol Chem, 2013. 288(20): p. 14114–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rittershaus ESC, et al. , A Lysine Acetyltransferase Contributes to the Metabolic Adaptation to Hypoxia in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Chem Biol, 2018. 25(12): p. 1495–1505 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.VanderVen BC, et al. , Novel inhibitors of cholesterol degradation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveal how the bacterium’s metabolism is constrained by the intracellular environment. PLoS Pathog, 2015. 11(2): p. e1004679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knapp GS, et al. , Role of intragenic binding of cAMP responsive protein (CRP) in regulation of the succinate dehydrogenase genes Rv0249c-Rv0247c in TB complex mycobacteria. Nucleic Acids Res, 2015. 43(11): p. 5377–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bai G, et al. , Dysregulation of serine biosynthesis contributes to the growth defect of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis crp mutant. Mol Microbiol, 2011. 82(1): p. 180–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bai G, McCue LA, and McDonough KA, Characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv3676 (CRPMt), a cyclic AMP receptor protein-like DNA binding protein. J Bacteriol, 2005. 187(22): p. 7795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rickman L, et al. , A member of the cAMP receptor protein family of transcription regulators in Mycobacterium tuberculosis is required for virulence in mice and controls transcription of the rpfA gene coding for a resuscitation promoting factor. Mol Microbiol, 2005. 56(5): p. 1274–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith LJ, et al. , Cmr is a redox-responsive regulator of DosR that contributes to M. tuberculosis virulence. Nucleic Acids Res, 2017. 45(11): p. 6600–6612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang H, et al. , Lysine acetylation of DosR regulates the hypoxia response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Emerg Microbes Infect, 2018. 7(1): p. 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bi J, et al. , Acetylation of lysine 182 inhibits the ability of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DosR to bind DNA and regulate gene expression during hypoxia. Emerg Microbes Infect, 2018. 7(1): p. 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lowrie DB, Aber VR, and Jackett PS, Phagosome-lysosome fusion and cyclic adenosine 3’:5’-monophosphate in macrophages infected with Mycobacterium microti, Mycobacterium bovis BCG or Mycobacterium lepraemurium. J Gen Microbiol, 1979. 110(2): p. 431–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lowrie DB, Jackett PS, and Ratcliffe NA, Mycobacterium microti may protect itself from intracellular destruction by releasing cyclic AMP into phagosomes. Nature, 1975. 254(5501): p. 600–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shenoy AR, et al. , The Rv0805 gene from Mycobacterium tuberculosis encodes a 3’,5’-cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase: biochemical and mutational analysis. Biochemistry, 2005. 44(48): p. 15695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomson M, et al. , Expression of a novel mycobacterial phosphodiesterase successfully lowers cAMP levels resulting in reduced tolerance to cell wall-targeting antimicrobials. J Biol Chem, 2022. 298(8): p. 102151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schulte J, Baumgart M, and Bott M, Identification of the cAMP phosphodiesterase CpdA as novel key player in cAMP-dependent regulation in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Mol Microbiol, 2017. 103(3): p. 534–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shenoy AR, et al. , Structural and biochemical analysis of the Rv0805 cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Mol Biol, 2007. 365(1): p. 211–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]