Abstract

Acidity is a key determinant of fruit organoleptic quality. Here, a candidate gene for fruit acidity, designated MdMYB123, was identified from a comparative transcriptome study of two Ma1Ma1 apple (Malus domestica) varieties, “Qinguan (QG)” and “Honeycrisp (HC)” with different malic acid content. Sequence analysis identified an A→T SNP, which was located in the last exon, resulting in a truncating mutation, designated mdmyb123. This SNP was significantly associated with fruit malic acid content, accounting for 9.5% of the observed phenotypic variation in apple germplasm. Differential MdMYB123- and mdmyb123-mediated regulation of malic acid accumulation was observed in transgenic apple calli, fruits, and plantlets. Two genes, MdMa1 and MdMa11, were up- and down-regulated in transgenic apple plantlets overexpressing MdMYB123 and mdmyb123, respectively. MdMYB123 could directly bind to the promoter of MdMa1 and MdMa11, and induce their expression. In contrast, mdmyb123 could directly bind to the promoters of MdMa1 and MdMa11, but with no transcriptional activation of both genes. In addition, gene expression analysis in 20 different apple genotypes based on SNP locus from “QG” × “HC” hybrid population confirmed a correlation between A/T SNP with expression levels of MdMa1 and MdMa11. Our finding provides valuable functional validation of MdMYB123 and its role in the transcriptional regulation of both MdMa1 and MdMa11, and apple fruit malic acid accumulation.

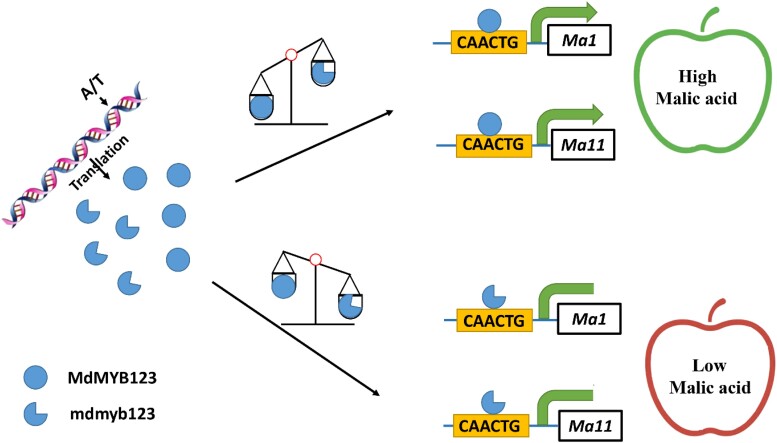

Competitive binding effect between MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 results in differential expression profiles of MdMa1 and MdMa11, which leads to variation in malic acid content.

Introduction

Acidity is one of the key factors controlling fruit flavor and quality. It mainly depends on the type and fruit organic acid contents, and usually expressed as acidic or using pH values (Harker et al. 2002). The main acids found in most ripe fruits are malic, citric, and tartaric acid (Zhang et al. 2010). Fruit acidity also has an important influence on the quality and color of processed products, such as fruit juice (Borsani et al. 2009). In addition, selection for low fruit acidity accompanied by changes in soluble sugar components and content during apple domestication have played important roles in determining fruit flavor quality (Ma et al. 2015a).

Organic acid accumulation in plant cells is mainly controlled by metabolism and vacuolar storage (Sweetman et al. 2009; Etienne et al. 2013). The metabolism of fruit organic acids begins with the synthesis of cytoplasmic dicarboxylate anions, through phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) fixation of CO2 under the action of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC) to form oxaloacetate (OAA). Subsequently, malate is produced by malate dehydrogenase (MDH) (Etienne et al. 2013; Batista-Silva et al. 2018), then transported into the vacuole by vacuolar transporters, which are crucial for controlling the extent of vacuolar acidification (Etienne et al. 2013). Numerous malate transporters, such as aluminum-activated malate transporter (ALMT) and tonoplast malate transporter (tDT) have been identified in the tonoplast of various plant species, including apple (Malus domestica) and Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) (Bai et al. 2012). A previous study mapped a quantitative trait loci (QTL) for malic acid in apple, designated Ma, on the top of linkage group 16, and showed that it accounted for 17% to 42% variation in apple fruit acidity (Xu et al. 2012). Later, a candidate Ma locus gene, MdMa1, was identified and shown to increase malate influx into the vacuole, accounting for ∼7.46% of the observed phenotypic variation in the malic acid content of mature fruits (Ma et al. 2015b; Li et al. 2020). Upon entering the acidic vacuole, malate, and citrate anions are protonated and trapped in the acid form, effectively maintaining their electrochemical potential gradient across the tonoplast for continuous diffusion into the vacuole (Etienne et al. 2013). Three major proton pumps, including vacuolar H+-ATPase, vacuolar pyrophosphatase (V-PPase), and P3A-type ATPase, which produces acidic vacuolar pH and positive electrical potential gradient have been identified in the tonoplast (Huang et al. 2021). In petunia (Petunia hybrida), PhPH5 encodes a vacuolar P3A-ATPase proton pump that mediates H+ transport across the vacuolar membrane (Verweij et al. 2008). Two tonoplast P-type proton pumps, PH1 and PH5, are regulated by a WRKY transcription factor (TF) encoding the PH3, leading to increased organic acids accumulation in citrus (Citrus sinensis) (Strazzer et al. 2019). In apple, a MdMa10 encoding P3A-type proton pump regulates malic acid accumulation in fruits by interacting with the MdMa1 gene (Ma et al. 2018). MdMa12 is a pyrophosphate proton pump located on the mitochondrial membrane, and its over-expression significantly increases malic acid content in apple fruits (Gao et al. 2022). In addition, MdMa11 and MdMa13 genes encoding P3A-type and P3B-type proton pumps, respectively, are located on the tonoplast. Both P3A-type and P3B-type proton pumps can directly or indirectly mediate the transmembrane transport of H+ and affect vacuolar acidity (Ma et al. 2021; Zheng et al. 2022). However, in apple, fewer studies have been reported on the simultaneously regulating malate transporters, such as MdMa1, and proton pumps, such as P-type ATPase.

Numerous TFs play crucial roles in regulating organic acid content by controlling the expression of structural target genes related to organic acid metabolism and transport. MYB proteins comprise one of the largest TF families in plants, and are extensively involved in plant development, hormone signaling, and metabolite synthesis (Liu et al. 2022). MYB TFs are categorized into four subgroups based on the number of MYB domains, including 2R-MYB (R2R3-MYB), 3R-MYB (R1R2R3-MYB), 4R-MYB, and 1R-MYB, of which R2R3-MYB is the largest in plants, and might have evolved from the R1R2R3-MYB subgroup by losing their R1 repeat (Huang et al. 2018). R2R3-MYB TFs harbors a highly conserved MYB domain in their structure, with a highly variable C-termini (Yang et al. 2022), and they have been closely associated with fruit acidity. In petunia, mutations in the MYB TFs encoding PH4 gene result in decreased vacuolar acidity (Quattrocchio et al. 2006). Transient over-expression of CrMYB73 encoding a PH-like gene significantly increased citric acid content in citrus (Li et al. 2015). MYB5a/b was shown to enhance the transcription of VvPH5 and VvPH1 on the tonoplast to promote vacuole acidification in grapes (Amato et al. 2019). In apple, MYB1 expressed in the red flesh apple peel altered malic acid accumulation in fruit by directly regulating the expression of MdVHA-B1 and MdVHA-B2 on the tonoplast (Hu et al. 2016). MdMYB73 predominantly expressed in root and leaves was shown to directly bind to and regulate the expression of acidity-related MdMa1, MdVHA-A, and MdVHP1 genes, leading to variation in pH and malate accumulation in the vacuole, and its interaction with MdCIbHLH1 TF enhanced its activity on target genes (Hu et al. 2017). In addition, MdMYB44 negatively regulated the accumulation of malic acid by inhibiting the transcription of MdMa1, MdMa10, MdVHA-A3, and MdVHA-D2 genes in apple (Jia et al. 2021). However, the mechanism underlying the regulation of fruit acidity by the highly expressed MYB TFs in apple fruit still remains unclear.

Previous studies have been identified MdMa1 and MdMa11 as major regulators of apple fruit acidity, and both genes were highly expressed in the mature fruits “HC” than of “QG” (Bai et al. 2012; Ma et al. 2015b; Ma et al. 2021). Here, comparative transcriptome analysis in the mature apple fruits of “QG” and “HC” was used to identify a MYB gene designated, MdMYB123. Sequence analysis identified an A→T SNP, located in the last exon, which resulted in a truncating mutation, designated mdmyb123. Notably, both proteins could bind to the promoters of MdMa1 and MdMa11, but only MdMYB123 could activate their transcription, suggesting their different roles in the regulation of apple fruit acidity. This study provides the valuable theoretical basis for understanding the molecular mechanism underlying the regulation of apple fruit acidity.

Results

Identification, phylogenetic analysis and expression profiling of MdMYB123

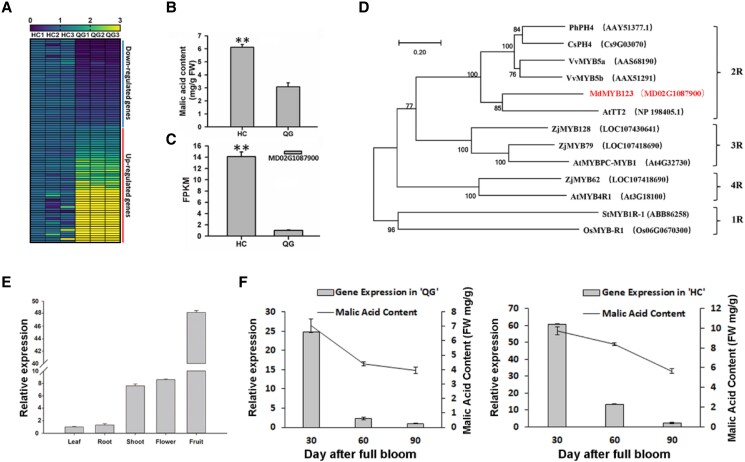

A total of 93 differentially expressed MYB TFs were identified from a comparative RNA-seq data of “QG” and “HC” (Ma et al. 2021). Of these TFs, 89 MYBs belonged to R2R3-MYB TFs (Supplemental Fig. S1). Fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped (FPKM) expression showed that 38 MYB TFs were up-regulated in the mature fruits of “HC”, while 51 MYB TFs were down-regulated in the mature fruits of “HC” (Fig. 1A). Among the 38 up-regulated genes, a candidate gene (MD02G1087900), designated MdMYB123, exhibited ∼13-fold higher expression levels in mature fruit of “HC” than in those of “QG” (Fig. 1, B and C).

Figure 1.

Identification, phylogenetic relationships, and expression profiling of MdMYB123. A) Heat map of 89 R2R3-MYBs in the mature fruits of “HC” and “QG”. B) Malic acid content in the mature fruits of “HC” and “QG”. The values are presented as the mean ± SD. **, significant difference as determined via t-test at P < 0.01. C) FPKM expression of MdMYB123 in the mature fruits of “HC” and “QG”. The values are presented as the mean ± SD. **, significant difference as determined via t-test at P < 0.01. FPKM: Fragments Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped fragments. D) Phylogenetic analysis of MYBs. Bootstrap values are indicated near the branch nodes, and gene accession numbers are displayed in parenthesis. Ph, P. hybrida; Cs, C. sinensis; Vv, V. vinifera; Md, M. domestica; At, A. thaliana; Zj, Ziziphus jujuba; St, Solanum tuberosum; Os, Oryza sativa. E)MdMYB123 expression levels in different apple tissues. Values are presented as the mean ± SD. F) Malic acid content and MdMYB123 expression in fruit of “QG” and “HC” at different developmental stages. Values are presented as the mean ± SD of three repetitions, FW, fresh weight.

Amino acid sequence alignment revealed that MdMYB123 consisted of both R2 and R3 domains (Supplemental Fig. S2). Phylogenetic analysis indicated that MdMYB123 closely grouped with an R2R3-MYB TF, AtTT2, from Arabidopsis (Fig. 1D). MdMYB123 expression profiling in five apple tissues revealed that it was predominantly expressed in fruit, followed by the flower, shoot, root, and leaf tissues (Fig. 1E). In addition, MdMYB123 profiling in fruits at three developmental stages in “QG” and “HC” showed that it was highly expressed in the mature fruits of “HC” than of “QG” in all developmental stages (Supplemental Table S1). Notably, MdMYB123 expression levels continuously decreased during fruit “HC” and “QG” development, which corresponded with the decrease in malic acid content during fruit development (Fig. 1F). In addition, the expression level of MdMYB123 exhibited similar trends with the change in malic acid content among 6 apple cultivars (Supplemental Fig. S3). These results suggested that MdMYB123 might play key roles in regulating malic acid content during apple fruit development.

Gene structure and subcellular localization of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123

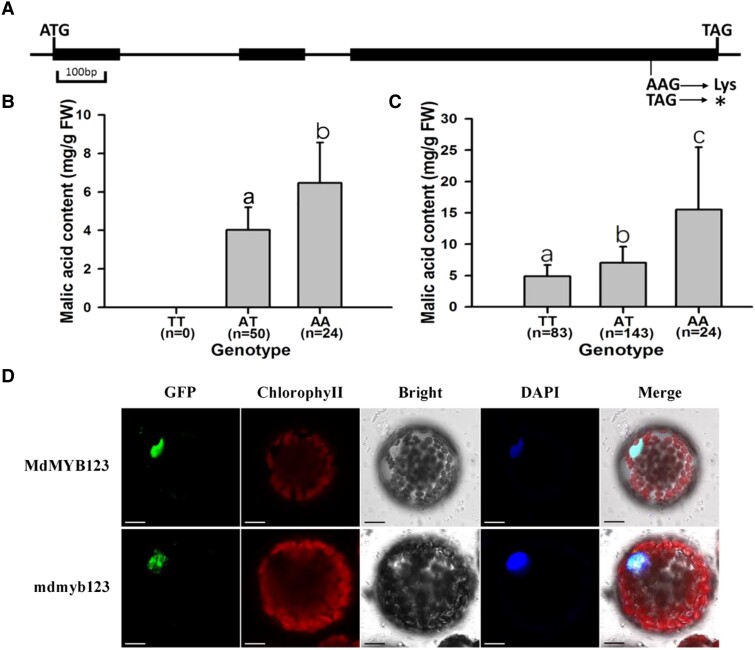

Gene structure analysis of the MdMYB123 sequence downloaded from the GDR revealed that it contained three exons and two introns, with a coding sequence (CDS) length of 987 bases translating 328 amino acids. Sequence analysis identified 11 SNPs in MdMYB123 whole genomic sequence between “QG” and “HC”. These 11 SNPs are all located in exons (Supplemental Fig. S4). However, among these 11 SNPs, 10 have the same genotype in “QG” and “HC”, one is heterozygous AT in “QG”, but homozygous AA in “HC”, which cause the translation of lysine amino acid into a stop codon, resulting in a truncating mutation (Fig. 2A) (Supplemental Table S2). Since the genotype is heterozygous AT in “QG”, but homozygous AA in “HC”, only two genotypes, AA and AT, occur in the “QG” × “HC” F1 hybrid population. The significant difference in malic acid content between these two genotypes was observed in the F1 hybrid population (Fig. 2B). Direct PCR sequencing method was used to identify the A/T SNP loci in a collection of 250 Malus accessions. Candidate gene-based association analysis showed that the A/T SNP was significantly associated with malic acid content, with P-values of 6.16 × 10−6, accounting for 9.45% of the observed phenotypic variation, respectively (Fig. 2C). For subcellular localization of MdMYB123 and its mutant mdmyb123, MdMYB123-/mdmyb123-GFP fusion construct under the control of dual CaMV35S promoter were transiently expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana mesophyll protoplasts. As a result, both MdMYB123-GFP and mdmyb123-GFP were found to be localized in the nucleus (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Gene structure, association analysis of MdMYB123 with fruit acidity, and its subcellular localization in N. benthamiana mesophyll protoplasts. A) Gene structure of MdMYB123 analysis, * indicates stop codon. B) The mean value of malic acid content in mature fruits of different apple genotypes based on A/T SNP of MdMYB123 gene in the “QG” × “HC” F1 hybrid population. C) The mean value of malic acid content in mature fruits of different genotype according to A/T SNP of MdMYB123 gene in an apple germplasm collection. In (B) and (C), the values are presented as the mean ± SD. Different letters over each bar indicate significant difference as determined via t-test at P < 0.01. FW, fresh weight. D) Subcellular localization of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123. Fluorescent DAPI served as the nuclear dye. Scale bars = 10 μm.

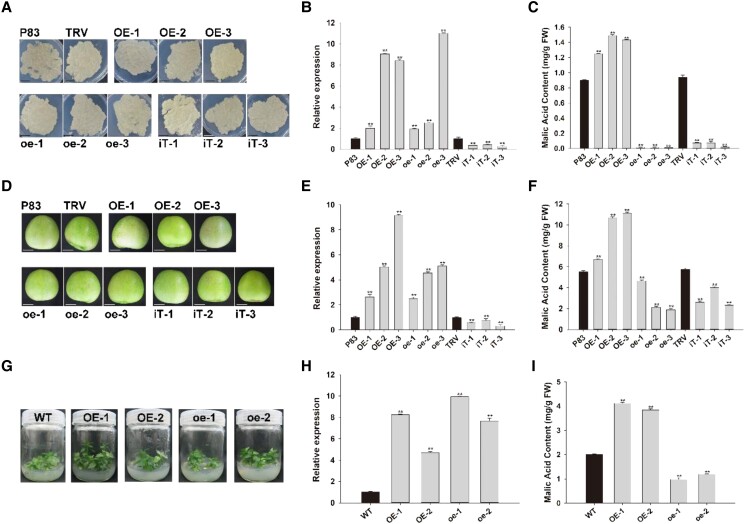

Functional analysis of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 in transgenic apple calli, mature fruits, and “GL3” plantlets

The roles of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 in regulating apple malic acid content were tested by cloning their whole CDS sequences into the pMDC83 vector to generate MdMYB123/mdmyb123 overexpressing apple calli. The pTRV2- MdMYB123/mdmyb123 virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) vectors were transformed into apple calli (Fig. 3A). Reverse-transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis showed significant up-regulated expression levels of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 in overexpression lines, while their profiles were significantly decreased in silenced lines (Fig. 3B). HPLC analysis revealed significantly higher malic acid content in transgenic apple calli overexpressing MdMYB123 gene than in control, while its content in the MdMYB123 silenced calli was significantly decreased (Fig. 3C). In contrast, significantly lower malic acid content was observed in transgenic calli overexpressing mdmyb123 gene than that in control (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Functional analysis of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 in transgenic apple calli, fruits, and plantlets. A) Overexpressing and silencing MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 in “Orin” apple calli. Scale bar, 1 cm. B) Relative expression of MdMYB123/mdmyb123 in apple calli. C) Measurement of malic acid content in transgenic apple calli. D) Overexpressing and silencing MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 in “Granny Smith” apple fruits. Scale bar, 1 cm. E) Relative expression of MdMYB123/mdmyb123 in apple fruits. F) Measurement of malic acid content in transgenic apple fruits. G) Overexpression analysis of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 in “GL3” apple plantlets. H) Relative expression of MdMYB123/mdmyb123 in “GL3” apple plantlets. I) Determination of malic acid content in apple leaves. The empty vector of pMDC83 (P83) and pTRV2 (TRV) were used as control. WT, wild-type. In (B, C, E, F, H) and (I), the values are presented as the mean ± SD of three repetitions. **, significant difference as determined via one-way ANOVA at P < 0.01, FW, fresh weight.

In addition, both overexpression and VIGS constructs of MdMYB123/mdmyb123 were transformed into “Granny Smith” apple fruits to further verify their roles in malic acid accumulation (Fig. 3D). As a result, the expression profiles of the two genes were significantly up-regulated in apple fruits overexpressing MdMYB123/mdmyb123, while the opposite result was observed in silenced fruits (Fig. 3E). HPLC analysis of in transgenic fruits revealed significant decrease and increase in malic acid content in silenced and overexpressed MdMYB123 apple fruits, respectively. In contrast, overexpressing mdmyb123 caused a significant reduction in the apple fruits malic acid contents (Fig. 3F).

Moreover, gene expression profiling in transgenic “GL3” plantlets overexpressing MdMYB123/mdmyb123 showed that MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 profiles were significantly up-regulated in transgenic overexpression lines relative to wild-type (Fig. 3, G and H). HPLC analysis revealed that malic acid content in transgenic apple leaves overexpressing MdMYB123 increased significantly, but was significantly decreased in apple lines overexpressing mdmyb123 (Fig. 3I). Taken together, these results obviously demonstrate that MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 have positive and negative regulatory effects on malate accumulation in apple, respectively.

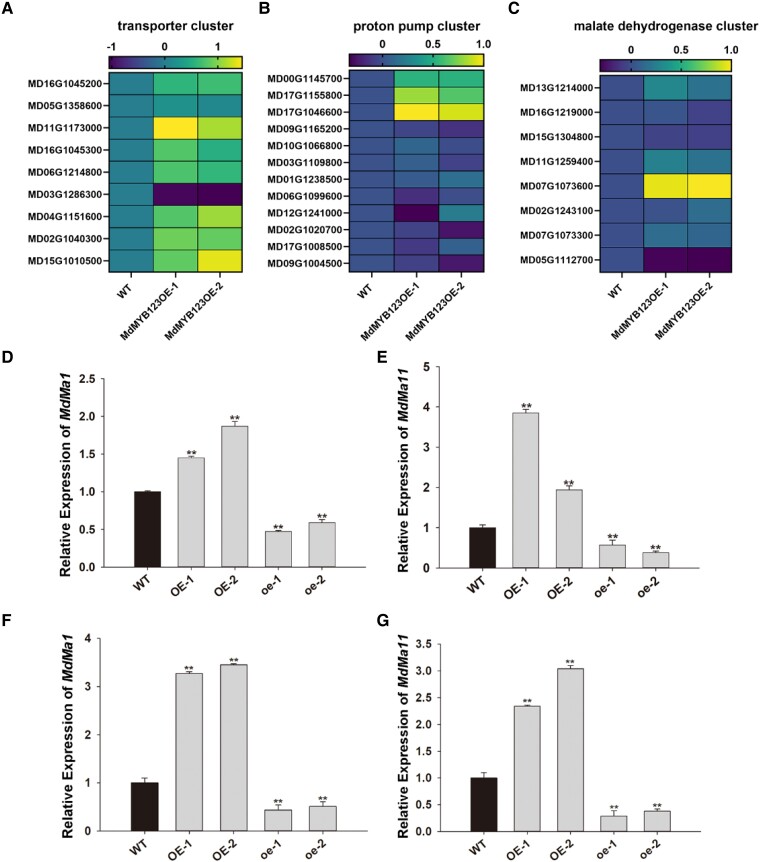

RNA-seq identification of candidate gene(s) associated with malic acid accumulation in “GL3” apple plantlets overexpressing MdMYB123/mdmyb123

Comparative RNA-seq analysis of wild type and MdMYB123-OE “GL3” apple plantlets revealed a total of 1,003 DEGs, of these 9, 12, and 8, were identified as candidate genes associated with malate transport, proton pumps, and malate dehydrogenases, respectively (Fig. 4, A–C) (Supplemental Table S3). Among these 29 genes, 11 were up-regulated in MdMYB123-OE “GL3” apple compared to wild type (Fig. 4C), subsequently, their expression levels were analyzed in wild type and MdMYB123/mdmyb123-OE “GL3” apples (Fig. 4D and Supplemental Fig. S5). Notably, only the expression levels of MD16G1045200 (MdMa1) and MD17G1155800 (MdMa11) showed an increase in MdMYB123-OE “GL3” apple and a decrease in mdmyb123-OE “GL3” apples compared to wild type (Fig. 4, D and E). In addition, the expression levels of MdMa1 and MdMa11 increased in MdMYB123-OE apple calli, while both genes had decreased profiles in mdmyb123-OE apple calli compared to wild type (Fig. 4, F and G). Consistently, a previous study also showed that MdMa1 and MdMa11 had lower expression levels in mature fruits of “QG” than of “HC” (Ma et al. 2021). Overall, these results suggest that MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 might alter malate content by regulating the expression levels of MdMa1 and MdMa11.

Figure 4.

RNA-seq analysis and expression profiles of MdMa1 and MdMa11 in transgenic “GL3” apple plantlets overexpressing MdMYB123. A–C) Heat maps showing the expression levels of malate transporter, proton pump, and malate dehydrogenases genes in the wild type and transgenic “GL3” apple plantlets overexpressing MdMYB123. D, E) The relative expression level of MdMa1 and MdMa11 in MdMYB123/mdmyb123-overexpressing “GL3” apple plantlets. F, G) The relative expression level of MdMa1 and MdMa11 in MdMYB123/mdmyb123-overexpressing “GL3” apple calli. In (D, E, F), and (G), the values are presented as the mean ± SD of three repetitions. **, significant difference as determined via one-way ANOVA at P<0.01.

MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 bind to MdMa1 and MdMa11 promoters, but only are transcriptionally activated by MdMYB123

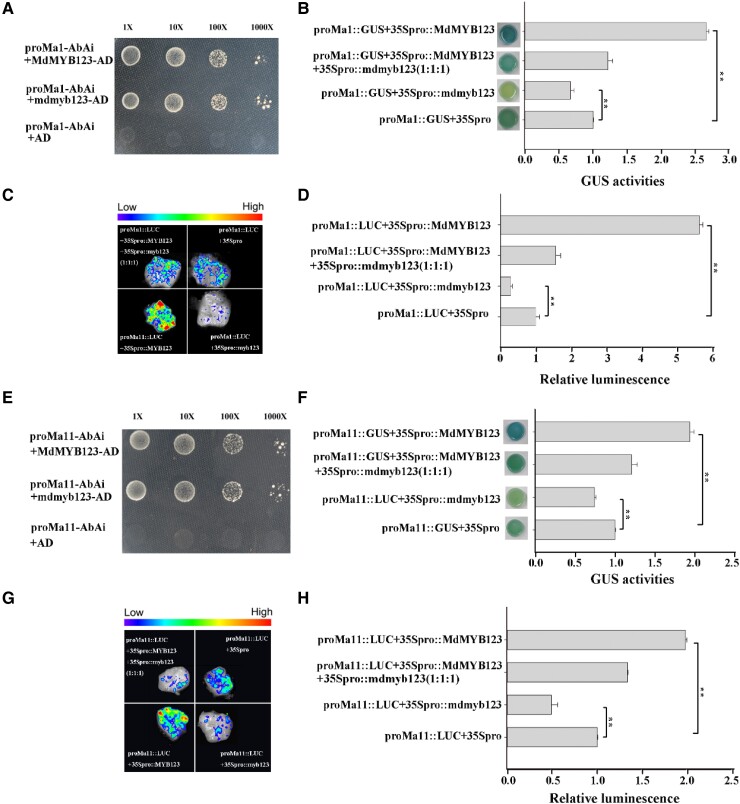

A yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) assay revealed that MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 could bind to the MdMa1 promoter (Fig. 5A). Moreover, the GUS reporter and luciferase (LUC) transactivation assays were performed to investigate whether MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 could bind to MdMa1 promoter and activate its transcription. As a result, GUS staining level and GUS content were significantly higher in apple calli containing both MdMa1pro::GUS and 35Spro::MdMYB123 than that containing both MdMa1pro::GUS and 35Spro::mdmyb123, while the GUS staining level and GUS content containing MdMa1pro::GUS: 35Spro::MdMYB123 : 35Spro::mdmyb123 (1:1:1) was intermediate to the two described above (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, the LUC activity assay also showed similar results as GUS reporter assay above. Co-expression of MdMa1pro::LUC and 35Spro::MdMYB123 exhibited more luminescence signal than the co-expression of MdMa1pro::LUC and 35Spro::mdmyb123, while the co-expression of MdMa1pro::LUC, 35Spro::MdMYB123 and 35Spro::mdmyb123 (1:1:1) exhibited luminescence signal that was intermediate to the two co-expressions above (Fig. 5, C and D).

Figure 5.

The binding of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 to MdMa1 and MdMa11 promoters and their transcriptional activation by MdMYB123. A, E) Y1H assay showing the binding of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 to MdMa1 and MdMa11 promoters, respectively. B, F) The GUS assay showing the binding of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 to MdMa1 and MdMa11 promoters, and their transcriptional activation by MdMYB123 and not mdmyb123. C, D, G, H) LUC activity assay showing the binding capacity of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 to MdMa1 and MdMa11 gene promoters, and their transcriptional activation by MdMYB123 and not mdmyb123. In (B, D, F), and (H), the values are presented as the mean ± SD of three repetitions. **, significant difference as determined via one-way ANOVA at P < 0.01.

Yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) assay showed that MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 could bind to the MdMa11 promoter (Fig. 5E). The GUS staining level and GUS content indicated that MdMYB123 could bind to the promoter of MdMa11, and activate its transcription, while mdmyb123 could also bind to the MdMa11 promoter, but with no capacity to activate its transcription (Fig. 5F). In order to further confirm the relationship between MdMYB123/mdmyb123 and MdMa11 promoter, The LUC activity assay was conducted and similar results to those of GUS staining level and GUS content above, were observed (Fig. 5, G and H).

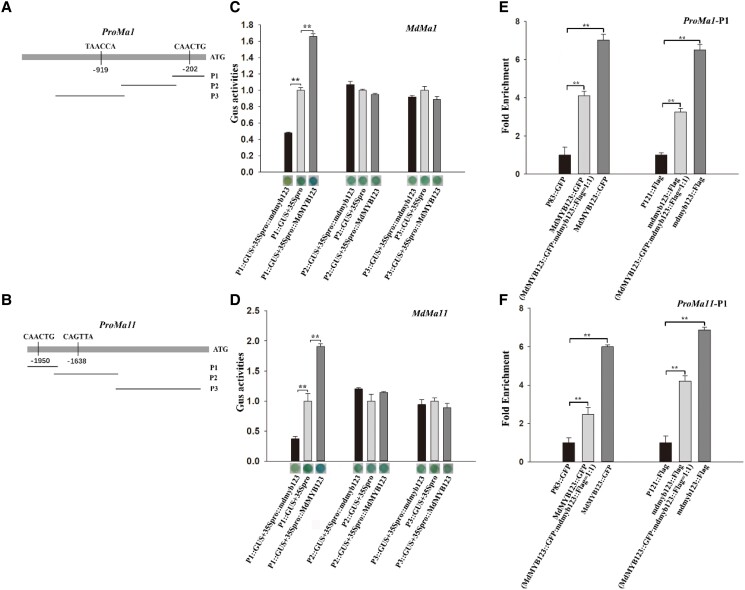

Moreover, the cis-acting elements in the 2-kb promoter regions upstream of the start codon (ATG) site of MdMa1 and MdMa11 were analyzed in PlantCare, and two MYB TF binding motifs were identified (Fig. 6, A and B). The GUS reporter assay indicated that MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 could only bind to the CAACTG motif sequence (Fig. 6, C and D). The chromatin immunoprecipitation quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR) assay showed about 6∼8-fold enrichment of MdMa1 and MdMa11 P1 promoters with MdMYB123 and mdmyb123. The fold enrichment of MdMa1 and MdMa11 P1 promoters with MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 in MdMYB123::GFP: mdmyb123::Flag (1:1) was higher than that of control, but low only in MdMYB123::GFP/mdmyb123::Flag (Fig. 6, E and F). Taken together, these results confirmed that MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 could bind to the promoters of MdMa1 and MdMa11, with their transcription being activated by MdMYB123 rather than mdmyb123. In addition, mdmyb123 competes with MdMYB123 for binding to the promoters of MdMa1 and MdMa11.

Figure 6.

Cis-acting elements screening and binding site competition of mdmyb123 and MdMYB123 to MdMa1 and MdMa11 promoters. A, B) The three fragments in the promoters of MdMa1 and MdMa11.C, D) The GUS assay showing the binding of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 to the P1 promoter region of MdMa1 and MdMa11, and their transcriptional activation by MdMYB123 and not mdmyb123. E, F) ChIP-qPCR showing the binding of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 and their competition for the MdMa1 and MdMa11 P1 promoter sites. In (C, D, E), and (F), the values are presented as the mean ± SD of three repetitions. **, significant difference as determined via one-way ANOVA at P<0.01.

Expression analysis of MdMa1 and MdMa11 in different MdMYB123 A/T SNP genotypes from “QG” × “HC” F1 hybrid population

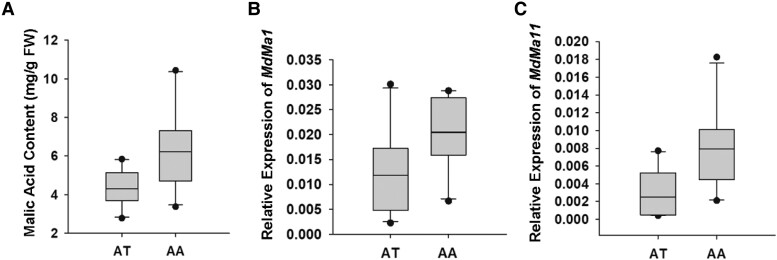

To further investigate the relationship between the A/T SNP locus and the expression levels of MdMa1 and MdMa11, 20 accessions from “QG” × “HC” F1 hybrid population, including 10 AA and AT individuals were randomly selected and screened. The mean malic acid content was significantly higher in “AA” than “AT” genotype group (Fig. 7A). Similarly, the expression levels of MdMa1 and MdMa11 genes were higher in “AA” than “AT” genotype group (Fig. 7, B and C). These results further support the observed transcriptional activation of MdMa1 and MdMa11 genes by MdMYB123 rather than mdmyb123. The observed low expression levels of MdMa1 and MdMa11 genes in the “AT” than “AA” genotype individuals could be attributed to the fact that mdmyb123 competes with MdMYB123 for promoter binding in these two genes, resulting in low gene expression levels and variation in malic acid content.

Figure 7.

The malic acid content and expression profiling of MdMa1 and MdMa11 in “QG” × “HC” F1 hybrid population with “AT” and “AA” genotypes. A) The malic acid content in “AT” and “AA” genotypes. FW, fresh weight. B) Relative expression profiles of MdMa1 in “QG” × “HC” F1 hybrid population with “AT” and “AA” genotypes. C) Relative expression profiles of MdMa11 in “QG” × “HC” F1 hybrid population with “AT” and “AA” genotypes. In (A, B) and (C), Center line: median; box limits: upper and lower quartiles; whiskers: 1.5 × interquartile range; points: outliers; n = 10.

Discussion

MYBs form one of the largest TF gene families in plants, and are widely involved in various plant-specific processes, such as development, hormone signaling, metabolite synthesis, cell differentiation, and response to external stimuli (Wu et al. 2022). Screening a comparative RNA-seq data of “QG” and “HC” identified a candidate, MdMYB123, with expression significantly correlated with apple fruit organic acids content (Fig. 2, B and C). In the previous study, several MYBs, such as MdMYB1, MdMYB10, MdMYB73 and MdMYB44 played crucial roles in determining apple fruit acidity (Hu et al. 2016, 2017; Jia et al. 2021). In this study, based on the RNA-seq data of “QG” and “HC” mature fruit, the expression levels of MdMYB1, MdMYB10, and MdMYB73 in “QG” mature fruit were higher than that in “HC” mature fruit, which were not consistent with malic acid content in “QG” and “HC” mature fruit. MdMYB44 expression levels exhibited no significant difference between “QG” and “HC”. In addition, the genomic variation of these MYBs was also investigated, and association analysis indicated that no significant difference was identified (Supplemental Table S4). Thus, MdMYB123 may play a unique role in the malic acidity regulation of “QG” and “HC”. Overexpression of MdMYB123 gene could significantly increase the content of malic acid in apple leaves, fruits, and apple calli, suggesting that MdMYB123 likely controls fruit acidity in apple.

MYB domains are classified into R1, R2, and R3 types according to their sequence similarities, with R2R3-MYB (2R-MYB) forming the predominant MYB subgroup in plant lineage based on their gene expansion patterns (Yang et al. 2022). Members of the R2R3-MYB genes have been closely linked to fruit acidity. Variations in gene sequences due to insertion, deletion, and mutation results in gene functional divergence. In Nicotiana benthamiana, overexpression of a truncated NtCBP4 caused improved tolerance to Pb2+, and attenuated lead accumulation (Sunkar et al. 2000). The apple Ma1 gene, encoding an ALMT9 homolog, has previously been identified as a key gene controlling fruit acidity (Bai et al. 2012; Ma et al. 2015), and a SNP in its last exon cause a premature stop codon that truncates the C-terminus of ma1 by 84 amino acids. Functional analysis of Ma1 and ma1 indicated a much stronger malate inward-rectifying current into vacuolar mediated by Ma1 than by ma1 (Li et al. 2020). Ectopic expression of Ma1 and ma1 in yeast exhibited significantly increased malic acid contents in transgenic lines expressing Ma1 compared to those carrying ma1 or empty vector (Ma et al. 2015). In this study, sequence analysis of MdMYB123 identified an A/T SNP variation in its last exon causing a truncating mutation, and resulting in a loss of 45 amino acids at the C-terminus of mdmyb123 (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, overexpression of the mutant mdmyb123 and MdMYB123 silencing caused similar phenotype characterized by decreased malic acid content in apple calli, fruit, and plantlets (Fig. 3), indicating differential regulation of malic acid accumulation by MdMYB123 and mdmyb123. Malic acid is the predominant organic acid in mature apple fruits, representing over 90% of total organic acid content (Zhang et al. 2012). A large proportion of malic acid in apple fruit is stored in the vacuole, and malate transport from the cytosol into the vacuole is crucial for determining fruit malic acid content (Ma et al. 2018). In addition, malate synthesis and degradation affect fruit malate level or malic acid content (Ma et al. 2018). RNA-seq analysis of wild type and MdMYB123-OE apples and identified 11 candidate genes associated with malate synthesis and transporters in this study (Fig. 4, A–C). Of the 11 genes, only MdMa1 and MdMa11 showed increased or decreased expression levels in MdMYB123-OE “GL3” or mdmyb123-OE “GL3” apple plantlets compared to the wild type, respectively (Fig. 4D and Supplemental Fig. S5). A previous RNA-seq study also reported lower expression levels of MdMa1 and MdMa11 in “QG” is than in “HC” (Ma et al. 2021), which is consistent with the patterns observed for MdMYB123 in this study. This suggests that MdMa1 and MdMa11 could be target genes of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123, thus, regulating malic acid accumulation in apple fruits. Moreover, Y1H, LUC transactivation, and GUS reporter assays indicated that MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 could bind to the promoter of MdMa1 and MdMa11, however, with only MdMYB123 having transcriptional activation capacity for the two structural genes (Fig. 5).

The R2R3-MYB protein harbors two key functional regions, including DNA binding and regulatory domains located at the N terminus and the C terminus, respectively. Normally, the N-terminal DNA binding domain is highly conserved, while the C-terminal regulatory domain show variability (Wu et al. 2022). Subcellular localization assay indicated nuclear localization of that both MdMYB123 and its mutant mdmyb123 (Fig. 2D). Meanwhile, both MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 are able to bind to the promoters of MdMa1 and MdMa11, MdMYB123 activates their transcription, and instead mdmyb123 cannot. Thus, we speculate that the missing 45 amino acids at the C-terminus of mdmyb123 contain whole or parts of regulatory domain, which plays crucial roles in activation of transcription of MdMa1 and MdMa11 genes.

The mean malic acid content in mature apple fruits “QG” × “HC” F1 hybrid population and Malus accessions showed significant differences among A/T SNPs with of “AA”, “AT” and “TT” genotypes, and followed the order of AA > AT > TT (Fig. 2). Similar results were observed for Ma1 A/G SNP genotypes in its last exon, including Ma1Ma1, Ma1ma1, and ma1ma1 (Ma et al. 2015). Ectopic expression of ma1 in yeast resulted in no significant difference in malic acid content compared to the control. However, the lower malic acid content in apple calli, fruits, and plantlets than in apple wild type or control was observed in overexpressing mdmyb123 in this study. The GUS staining level and GUS content were significantly higher in apple calli containing both MdMa1pro::GUS and 35Spro::MdMYB123 than in that containing both MdMa1pro::GUS and 35Spro::mdmyb123. In contrast, GUS staining level and GUS content of MdMa1pro::GUS: 35Spro::MdMYB123 : 35Spro::mdmyb123 (1:1:1) had intermediate levels with those two described above (Fig. 5B). Co-expression of MdMa1pro::LUC and 35Spro::MdMYB123 exhibited more luminescence signal than the co-expression of MdMa1pro::LUC and 35Spro::mdmyb123, while the co-expression of MdMa1pro::LUC, 35Spro::MdMYB123 and 35Spro::mdmyb123 (1:1:1) exhibited intermediate luminescence signal with those two described above (Fig. 5, C and D). These results were consistent with those observed for MdMa11. The fold enrichment of P1 MdMa1 and MdMa11 promoters with MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 regulators in MdMYB123::GFP: mdmyb123::Flag (1:1) was higher than that of control and only lower than for MdMYB123::GFP/mdmyb123::Flag. Among the 20 randomly selected “AA” and “AT” individual genotypes from “QG” × “HC” F1 hybrid population, malate content of “AA” genotypes was higher than of “AT” genotypes, while the expression levels of MdMa1 and MdMa11 in “AA” genotypes were higher than those of “AT” genotypes. Thus, we speculate the inherent binding site competition between MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 to MdMa1 and MdMa11 gene promoters, leading to their varied expression profiles.

Malic acid accumulation is controlled by malate metabolism and vacuolar storage in plant cells (Sweetman et al. 2009; Etienne et al. 2013). Vacuolar transporters can translocate malate into or out of the vacuole; therefore, their participation is crucial for controlling the extent of vacuolar acidification (Etienne et al. 2013). Proton pumps, including vacuolar H+-ATPase, P-type ATPases, and vacuolar pyrophosphatase (V-PPase), are involved in proton transportation and generation of proton electrochemical gradient that provides the driving force for malate translocation into the vacuole (Etienne et al. 2013). Malate and citrate anions are protonated upon entering the acidic vacuole, then trapped in acidic form to effectively maintain their concentration gradient across the tonoplast and enable continuous diffusion into the vacuole (Huang et al. 2021). In apple, the coordinated regulation of Ma10 and Ma1, which belongs to P3A-ATPase and ALMT gene families respectively, was shown to control malic acid accumulation (Ma et al. 2018). Here, the expression levels of both MdMa1 and MdMa11 were upregulated in MdMYB123-OE plantlets compared to wild apple plantlets. Both MdMa1 and MdMa11 are localized in the tonoplast, and mediate malate and H+ diffusion into vacuole, respectively (Ma et al. 2021). The MdMa11 mediated translocation of protons into the vacuole enhances the electrochemical gradient across the tonoplast and H+ concentration in vacuole (vacuole acidity). Once in the acidic vacuole, malate is immediately protonated (malic acid) then accumulated. The acid trapping strategy effectively maintains the high concentration of malic acid in vacuole, and facilitates diffusion of malate from cytosol into vacuole. In addition to high transcript abundance of MdMa1 and MdMa11, the expression of six genes related to malate transport, proton pumps, and malate dehydrogenases were also up-regulated in MdMYB123-OE “GL3” apple plantlets (Supplemental Fig. S5), suggesting that unknown genes besides MdMa1 and MdMa11 potentially involved in the regulation of apple fruit acidity, thus, indicating the complex regulatory mechanism of MdMYB123/mdmyb123 in fruit acidity.

Based on the above results, we proposed a model that could explain the different functions of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 in regulating fruit acidity (Fig. 8). The variation in A/T SNP at the last exon of MdMYB123 caused a premature stop codon at the C-terminus of MdMYB123, producing a truncated mutant gene, mdmyb123. Both MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 binds to the promoters of MdMa1 and MdMa11 genes, but are only activated by MdMYB123. Occurrence of the competitive binding effect between MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 results in varied expression profiles of target MdMa1 and MdMa11 genes.

Figure 8.

A working model illustrating the roles of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 in regulating apple fruit malate content. The A/T SNP on the last exon of MdMYB123 cause a truncated translation, resulting in a mutant truncated gene designated, mdmyb123. MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 compete for binding to the CAACTG sequences on the promoters of MdMa1 and MdMa11. The transcription of both MdMa1 and MdMa11 can be activated by MdMYB123 but not mdmyb123, causing differences in the regulation of malic acid content between these two genes.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The “QG” × “HC” F1 hybrid population used in this study is maintained at the Horticultural Experimental Station of Northwest A&F University, Yangling, Shaanxi province, China. The apple (Malus domestica) germplasm used is planted in the Xingcheng Institute of Pomology of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Xingcheng, Liaoning, China. The date of harvest, fruit size or weight, the number of fruit sampled, and the number of biological reps of apple germplasm were the same as previously described (Liao et al. 2021). Five apple tissues, including fully bloomed flower, root, mature leaf, ripening fruit, and shoot were collected from “HC” plants for RT-qPCR assay. The apple calli were induced from young fruits of “Orin” then cultured on solid Murashige and Skoog culture (MS) medium with 1.5 mg/L 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and 0.4 mg/L 6-benzylaminopurine at 25 °C in darkness. Tissue-cultured WT apple plantlets were grown on MS medium supplemented with 0.2 mg L−1 IAA, and 0.3 mg L−1 6-BA. MdMYB123/mdmyb123–transformed “GL3” apple plantlets were grown on MS medium supplemented with 25 mg L−1 kanamycin, 0.2 mg L−1 IAA, and 0.3 mg L−1 6-BA.

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree analysis

To identify MYB123 gene sequences in apple, the assembled GDDH13 version 1.1 M. × domestica genome (https://www.rosaceae.org) was screened with BLASTp to retrieve homologous sequences for phylogenetic analysis using the neighbor-joining method with default program parameters (http://www.megasoftware.net/).

RNA isolation and RT-qPCR analysis

Total RNA Extraction Kit (Wolact, Hong Kong, China) was used to extract total RNA from samples. cDNA samples were synthesized from total RNA using the TransScript® One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransGen, Beijing, China). RT-qPCR was performed in three biological replicates according to a previous protocol (Zhang et al. 2021), and relative expression levels were calculated according to the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Measurement of organic acid contents

Malic acid contents were measured using as previously described (Zheng et al. 2022). Briefly, malic acid was extracted using the water extraction method, then content was determined using the 1260 Infinity high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Agilent, Milford, MA, USA). The chromatographic separation was performed on an Athena C18 column (100 Å, 4.6 nm × 250 nm, 5 μm). The mobile phase was a 0.02 M KH2PO4 solution (pH 2.4), and the flow rate was 0.8 mL/min. The column temperature was maintained at 40 °C. Measurements were carried out in three biological replicates. The standards used in this study were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) and dissolved in deionized water.

Marker-trait association of MdMYB123/mdmyb123

The coding sequences of MdMYB123/mdmyb123 gene were retrieved from the GDDH13 version 1.1 apple genome (https://www.rosaceae.org). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and amplification primer sequence, 5′- ATGGGGAGAAGCCCTTG-3′/5′-TCAACTACTCTTTCCAACTCCA-3′, for screening apple germplasm were successfully developed. Candidate gene-based association mapping was performed with a mixed linear model in the software package TASSEL version 5.0 (Liao et al. 2021). The apple germplasm collection used and the population structure parameters, such as the Q matrix and K matrix were the same as those previously described (Liao et al. 2021). The criterion for marker–trait association was set at P ≤ 0.01 based on the false discovery rate.

Subcellular localization analysis

The coding sequences of MdMYB123 and the mutant mdmyb123 lacking the stop codon were cloned into pMDC83-GFP vector to generate the fusion 35Spro::MdMYB123::GFP and 35Spro::mdmyb123::GFP, which were transformed into N. benthamiana mesophyll protoplasts (Yoo et al. 2007). Images were acquired using a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope, equipped with a water immersion objective (40×/1.4). DAPI (4′-6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole, Solarbio, Beijing, China) excitation was performed using a 405 nm solid-state laser, and fluorescence was detected at 415–480 nm, and the intensity and gain were 4.99% and 100 in HyD SMD, respectively. GFP excitation was performed using a 488 nm solid-state laser, and fluorescence was detected at 498–540 nm, and the intensity and gain were 15.2% and 800 in PMT, respectively. The cell nuclear dye used was DAPI at 0.5 mg/mL, while the primers used are shown in Supplemental Table S5.

Plasmid construction and genetic transformation

The MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 coding sequences were inserted into pMDC83 vectors, while partial antisense sequences of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 were isolated and introduced into the pTRV2 (tobacco rattle virus) vector. In addition, the MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 coding sequences were inserted into the pHellsgate2 vectors with the CaMV35S promoter. The primers used are shown in Supplemental Table S3. Transgenic apple calli and “GL3” apple plantlets were generated using the Agrobacterium-mediated method as previously described (Yoo et al. 2007; Strazzer et al. 2019). The pTRV2-MdMYB123 and pTRV2-mdmyb123 were inserted in Agrobacterium (strain EHA105) for apple fruit transformation as previously described (Zhu et al. 2021).

RNA-seq analysis

Total RNA was extracted using the RNAprep Pure Plant kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China), and a total of 3 μg RNA per sample were used for RNA-seq library construction at the Biomarker Biotechnology corporation (Beijing, China) according to the methods of Lou et al. (2014). Transcriptome sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeqTM 2000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Gene expression levels were estimated using FPKM values.

The RNA-seq raw data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (project PRJNA915229 and PRJNA915227).

Y1H assay

The Y1H assays were performed as previously described (Tian et al. 2015; Li et al. 2017). The promoters of MdMa1 and MdMa11 were inserted into the pAbAi vector to generate MdMa1pro-pAbAi and MdMa11 pro-pAbAi constructs. The full-length CDSs of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 were cloned to the pGADT7 vector containing an activation domain, to generate MdMYB123-Ad and mdmyb123-Ad constructs, respectively. The yeast cells containing MdMa1pro-pAbAi and pGADT7 (Ad) vectors were used as control. Aureobasidin A (ABA) (Warbio, Nanjing, China) at concentrations of 500 ng/mL and 400 ng/mL were used for MdMa1 and MdMa11, respectively in this study. Primers used for the Y1H assay are shown in Supplemental Table S5.

LUC assay

LUC assay following a previously reported method (Jia et al. 2021). Briefly, the promoters of MdMa1 and MdMa11 were cloned into the pGreenII 0800-LUC vector to generate the luciferase reporter gene. The full-length coding sequences of MdMYB123 or mdmyb123 were cloned into the pGreenII 62-SK vector to generate the effector. The infiltration was performed as previously described (Jia et al. 2021). The in vivo imaging system was used for luminescence measurement. Primers for LUC assay are shown in Supplemental Table S5.

GUS analysis

Full-length coding sequences of MdMYB123 and mdmyb123 were introduced into the pMDC83 vector to form an effector plasmid. The promoters of MdMa1 and MdMa11 and their fragments were cloned into the pCAMBIA0390 vector to generate the GUS reporter plasmid. Each GUS assay was performed in triplicates. The detection of GUS activity was as previously described (An et al. 2018). Primers for the GUS assay are shown in Supplemental Table S5.

ChIP-qPCR analysis

The ChIp-qPCR analysis was performed as previously described (Zhang et al. 2022). The full-length coding sequences of mdmyb123 and MdMYB123 each without the stop codon were inserted into the pBI121-Flag vector and pMDC83-GFP vector, respectively. The recombinant MdMYB123-GFP, mdmyb123-Flag, and MdMYB123-GFP: mdmyb123-Flag (1:1) were then transformed into the apple calli. The ChIP-qPCR assays were performed using an anti-GFP antibody and anti-Flag antibody. Primers used in this assay are shown in Supplemental Table S5.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyzes were performed using SPSS Statistics 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA tests, and statistical significance was inferred at P < 0.01.

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in GenBank/GDR data libraries under accession numbers MdMYB123/mdmyb123 (MD02G1087900), MdMa1 (MD16G1045200), MdMa11 (MD17G1155800).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authorsare grateful to Dr. Jing Zhang, Miss Jing Zhao and Miss Wenjing Cao (Horticulture Science Research Center, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, China) for providing professional technical assistance with HPLC analysis.

Contributor Information

Litong Zheng, State Key Laboratory of Crop Stress Biology for Arid Areas/Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Apple, College of Horticulture, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, 712100, Shaanxi, China.

Liao Liao, CAS Key Laboratory of Plant Germplasm Enhancement and Specialty Agriculture, The Innovative Academy of Seed Design of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan Botanical Garden, Wuhan 430074, China.

Chenbo Duan, State Key Laboratory of Crop Stress Biology for Arid Areas/Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Apple, College of Horticulture, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, 712100, Shaanxi, China.

Wenfang Ma, State Key Laboratory of Crop Stress Biology for Arid Areas/Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Apple, College of Horticulture, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, 712100, Shaanxi, China.

Yunjing Peng, State Key Laboratory of Crop Stress Biology for Arid Areas/Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Apple, College of Horticulture, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, 712100, Shaanxi, China.

Yangyang Yuan, State Key Laboratory of Crop Stress Biology for Arid Areas/Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Apple, College of Horticulture, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, 712100, Shaanxi, China.

Yuepeng Han, CAS Key Laboratory of Plant Germplasm Enhancement and Specialty Agriculture, The Innovative Academy of Seed Design of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan Botanical Garden, Wuhan 430074, China.

Fengwang Ma, State Key Laboratory of Crop Stress Biology for Arid Areas/Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Apple, College of Horticulture, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, 712100, Shaanxi, China.

Mingjun Li, State Key Laboratory of Crop Stress Biology for Arid Areas/Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Apple, College of Horticulture, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, 712100, Shaanxi, China.

Baiquan Ma, State Key Laboratory of Crop Stress Biology for Arid Areas/Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Apple, College of Horticulture, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, 712100, Shaanxi, China.

Author contributions

B.M. and M.L. conceived and supervised this research. L.Z., C.D., W.M., and Y.P. performed the experiments. L.L. and Y.H. performed the marker-trait association experiments. Y.Y. provided assistance with the subcellular localization. L.Z. analyzed the data and wrote the paper. F.M. revised the paper.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Sequence alignment of 89 R2R3-MYBs.

Supplemental Figure S2. Multiple sequence alignment of R2R3-MYB proteins showing the R2 and R3 repeats of MYB domains marked at the top.

Supplemental Figure S3. The expression profiles of MdMYB123 and the malic acid contents in the fruit of different apple cultivars.

Supplemental Figure S4. SNPs in MYB123 genomic sequence.

Supplemental Figure S5. The relative expression level of 9 genes in wild type and MdMYB123/mdmyb123-OE “GL3” apples.

Supplemental Table S1. MdMYB123 expression in fruit of “QG” and “HC” during development.

Supplemental Table S2. SNPs in MdMYB123 whole genomic sequence between “QG” and “HC”.

Supplemental Table S3. Profiling of DEGs in transgenic “GL3” apple as compared between the wild type.

Supplemental Table S4. Genotype of MdMYB1, MdMYB10, MdMYB44, MdMYB73, MdMa1 and MdMa11.

Supplemental Table S5. Primer sequences used in this study.

Supplemental Table S6. Genotypic and phenotypic information in apple germplasm accessions.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers 32272665 and 31872059), the Program for the Shaanxi science and technology innovation team project (2022TD-18), the Key S&T Special Projects of Shaanxi Province, China (Grant Number 2020zdzx03-01-02), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant Number 2452022110).

References

- Amato A, Cavallini E, Walker AR, Pezzotti M, Bliek M, Quattrocchio F, Koes R, Ruperti B, Bertini E, Zenoni S, et al. The MYB 5-driven MBW complex recruits a WRKY factor to enhance the expression of targets involved in vacuolar hyper-acidification and trafficking in grapevine. Plant J. 2019:99(6): 1220–1241. 10.1111/tpj.14419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An JP, Li R, Qu FJ, You CX, Wang XF, Hao YJ. R2R3-MYB transcription factor MdMYB23 is involved in the cold tolerance and proanthocyanidin accumulation in apple. Plant J. 2018:96(3): 562–577. 10.1111/tpj.14050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Dougherty L, Li M, Fazio G, Cheng L, Xu K. A natural mutation-led truncation in one of the two aluminum-activated malate transporter-like genes at the Ma locus is associated with low fruit acidity in apple. Mol Genet Genomics. 2012:287(8): 663–678. 10.1007/s00438-012-0707-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista-Silva W, Nascimento VL, Medeiros DB, Nunes-Nesi A, Ribeiro DM, Zsögön A, Araújo WL. Modifications in organic acid profiles during fruit development and ripening: correlation or causation? Front Plant Sci. 2018:9: 1689. 10.3389/fpls.2018.01689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsani J, Budde CO, Porrini L, Lauxmann MA, Lombardo VA, Murray R, Andreo CS, Drincovich MF, Lara MV. Carbon metabolism of peach fruit after harvest: changes in enzymes involved in organic acid and sugar level modifications. J Exp Bot. 2009:60(6): 1823–1837. 10.1093/jxb/erp055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne A, Génard M, Lobit P, Mbeguié-A-Mbéguié D, Bugaud C. What controls fleshy fruit acidity? A review of malate and citrate accumulation in fruit cells. J Exp Bot. 2013:64(6): 1451–1469. 10.1093/jxb/ert035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Zhao H, Zheng L, Zhang L, Peng Y, Ma W, Tian R, Yuan Y, Ma F, Li M, et al. Overexpression of apple Ma12, a mitochondrial pyrophosphatase pump gene, leads to malic acid accumulation and the upregulation of malate dehydrogenase in tomato and apple calli. Hortic Res. 2022:9: uhab053. 10.1093/hr/uhab053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harker FR, Marsh KB, Young H, Murray SH, Walker SB. Sensory interpretation of instrumental measurements 2: sweet and acid taste of apple fruit. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2002:24(3): 241–250. 10.1016/S0925-5214(01)00157-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu DG, Li YY, Zhang QY, Li M, Sun CH, Yu JQ, Hao YJ. The R2R3-MYB transcription factor MdMYB73 is involved in malate accumulation and vacuolar acidification in apple. Plant J. 2017:91(3): 443–454. 10.1111/tpj.13579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu DG, Sun CH, Ma QJ, You CX, Cheng L, Hao YJ. MdMYB1 regulates anthocyanin and malate accumulation by directly facilitating their transport into vacuoles in apples. Plant Physiol. 2016:170(3): 1315–1330. 10.1104/pp.15.01333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XY, Wang CK, Zhao YW, Sun CH, Hu DG. Mechanisms and regulation of organic acid accumulation in plant vacuoles. Hortic Res. 2021:8(1): 227. 10.1038/s41438-021-00702-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Zhao H, Gao F, Yao P, Deng R, Li C, Chen H, Wu Q. A R2R3-MYB transcription factor gene, FtMYB13, from Tartary buckwheat improves salt/drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2018:132: 238–248. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia D, Wu P, Shen F, Li W, Zheng X, Wang Y, Yuan Y, Zhang X, Han Z. Genetic variation in the promoter of an R2R3-MYB transcription factor determines fruit malate content in apple (Malus domestica Borkh.). Plant Physiol. 2021:186(1): 549–568. 10.1093/plphys/kiab098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Dougherty L, Coluccio AE, Meng D, El-Sharkawy I, Borejsza-Wysocka E, Liang D, Piñeros MA, Xu K, Cheng L. Apple ALMT9 requires a conserved C-terminal domain for malate transport underlying fruit acidity. Plant Physiol. 2020:182(2): 992–1006. 10.1104/pp.19.01300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SJ, Liu XJ, Xie XL, Sun CD, Chen KS. CrMYB73, a PH-like gene, contributes to citric acid accumulation in citrus fruit. Sci Hortic. 2015:197: 212–217. 10.1016/j.scienta.2015.09.037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Xu Y, Zhang L, Ji Y, Tan D, Yuan H, Wang A. The jasmonate-activated transcription factor MdMYC2 regulates ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR and ethylene biosynthetic genes to promote ethylene biosynthesis during apple fruit ripening. Plant Cell. 2017:29(6): 1316–1334. 10.1105/tpc.17.00349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao L, Zhang W, Zhang B, Fang T, Wang XF, Cai Y, Ogutu C, Gao L, Chen G, Nie X, et al. Unraveling a genetic roadmap for improved taste in the domesticated apple. Mol Plant. 2021:14(9): 1454–1471. 10.1016/j.molp.2021.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Chao N, Yidilisi K, Kang X, Cao X. Comprehensive analysis of the MYB transcription factor gene family in Morus alba. BMC Plant Biol. 2022:22(1): 281. 10.1186/s12870-022-03626-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Q, Liu Y, Qi Y, Jiao S, Tian F, Jiang L, Wang Y. Transcriptome sequencing and metabolite analysis reveals the role of delphinidin metabolism in flower colour in grape hyacinth. J Exp Bot. 2014:65(12): 3157–3164. 10.1093/jxb/eru168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma B, Chen J, Zheng H, Fang T, Ogutu C, Li S, Han Y, Wu B. Comparative assessment of sugar and malic acid composition in cultivated and wild apples. Food Chem. 2015a:172: 86–91. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Li B, Zheng L, Peng Y, Tian R, Yuan Y, Zhu L, Su J, Ma F, Li M, et al. Combined profiling of transcriptome and DNA methylome reveal genes involved in accumulation of soluble sugars and organic acid in apple fruits. Foods. 2021:10(9):2198. 10.3390/foods10092198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma B, Liao L, Fang T, Qian P, Collins O, Hui Z, Ma F, Han Y. A Ma10 gene encoding P-type ATPase is involved in fruit organic acid accumulation in apple. Plant Biotechnol J. 2018:17(3): 674–686. 10.1111/pbi.13007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma B, Liao L, Zheng H, Chen J, Wu B, Ogutu C, Li S, Korban SS, Han Y. Genes encoding aluminum-activated malate transporter II and their association with fruit acidity in apple. Plant Genome. 2015b:8(3): 1–14. 10.3835/plantgenome2015.03.0016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quattrocchio F, Verweij W, Kroon A, Spelt C, Mol J, Koes R. PH4 Of Petunia is an R2R3 MYB protein that activates vacuolar acidification through interactions with basic-helix-loop-helix transcription factors of the anthocyanin pathway. Plant Cell. 2006:18(5): 1274–1291. 10.1105/tpc.105.034041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strazzer P, Spelt CE, Li S, Bliek M, Federici CT, Roose ML, Koes R, Quattrocchio FM. Hyperacidification of Citrus fruits by a vacuolar proton-pumping P-ATPase complex. Nat Commun. 2019:10(1): 744. 10.1038/s41467-019-08516-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunkar R, Kaplan B, Bouché N, Arazi T, Dolev D, Talke IN, Maathuis FJ, Sanders D, Bouchez D, Fromm H. Expression of a truncated tobacco NtCBP4 channel in transgenic plants and disruption of the homologous Arabidopsis CNGC1 gene confer Pb2+ tolerance. Plant J. 2000:24(4): 533–542. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00901.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetman C, Deluc LG, Cramer GR, Ford CM, Soole KL. Regulation of malate metabolism in grape berry and other developing fruits. Phytochemistry. 2009:70(11–12): 1329–1344. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J, Peng Z, Zhang J, Song T, Wan H, Zhang M, Yao Y. McMYB10 regulates coloration via activating McF3′H and later structural genes in ever-red leaf crabapple. Plant Biotechnol J. 2015:13(7): 948–961. 10.1111/pbi.12331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verweij W, Spelt C, Di Sansebastiano GP, Vermeer J, Reale L, Ferranti F, Koes R, Quattrocchio F. An H+ P-ATPase on the tonoplast determines vacuolar pH and flower colour. Nat Cell Biol. 2008:10(12): 1456–1462. 10.1038/ncb1805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Wen J, Xia Y, Zhang L, Du H. Evolution and functional diversification of R2R3-MYB transcription factors in plants. Hortic Res. 2022:9: uhac058. 10.1093/hr/uhac058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K, Wang A, Brown S. Genetic characterization of the Ma locus with pH and titratable acidity in apple. Mol Breeding. 2012:30(2): 899–912. 10.1007/s11032-011-9674-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Zhang B, Gu G, Yuan J, Shen S, Jin L, Lin Z, Lin J, Xie X. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the R2R3-MYB gene family in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.). BMC Genom. 2022:23(1): 432. 10.1186/s12864-022-08658-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SD, Cho YH, Sheen J. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat Protoc. 2007:2(7): 1565–1572. 10.1038/nprot.2007.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Li P, Cheng L. Developmental changes of carbohydrates, organic acids, amino acids, and phenolic compounds in ‘Honeycrisp’ apple flesh. Food Chem. 2010:123(4): 1013–1018. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.05.053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Ma B, Li H, Chang Y, Han Y, Li J, Wei G, Zhao S, Khan MA, Zhou Y, et al. Identification, characterization, and utilization of genome-wide simple sequence repeats to identify a QTL for acidity in apple. BMC Genom. 2012:13(1): 537. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Ma B, Wang C, Chen X, Ruan YL, Yuan Y, Ma F, Li M. MdWRKY126 modulates malate accumulation in apple fruit by regulating cytosolic malate dehydrogenase (MdMDH5). Plant Physiol. 2022:188(4): 2059–2072. 10.1093/plphys/kiac023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Sun S, Liang Y, Li B, Ma S, Wang Z, Ma B, Li M. Nitrogen levels regulate sugar metabolism and transport in the shoot tips of crabapple plants. Front Plant Sci. 2021:12: 626149. 10.3389/fpls.2021.626149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L, Ma W, Deng J, Peng Y, Tian R, Yuan Y, Li B, Ma F, Li M, Ma B. A MdMa13 gene encoding tonoplast P 3B -type ATPase regulates organic acid accumulation in apple. Sci Hortic. 2022:296: 110916. 10.1016/j.scienta.2022.110916 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Li B, Wu L, Li H, Wang Z, Wei X, Ma B, Zhang Y, Ma F, Ruan YL, et al. MdERDL6-mediated glucose efflux to the cytosol promotes sugar accumulation in the vacuole through up-regulating TSTs in apple and tomato. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021:118(1): e2022788118. 10.1073/pnas.2022788118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.