Abstract

Background

Evidence suggests that the intake of blueberry (poly)phenols is associated with improvements in vascular function and cognitive performance. Whether these cognitive effects are linked to increases in cerebral and vascular blood flow or changes in the gut microbiota is currently unknown.

Methods

A double-blind, parallel randomized controlled trial was conducted in 61 healthy older individuals aged 65–80 y. Participants received either 26 g of freeze-dried wild blueberry (WBB) powder (302 mg anthocyanins) or a matched placebo (0 mg anthocyanins). Endothelial function measured by flow-mediated dilation (FMD), cognitive function, arterial stiffness, blood pressure (BP), cerebral blood flow (CBF), gut microbiome, and blood parameters were measured at baseline and 12 wk following daily consumption. Plasma and urinary (poly)phenol metabolites were analyzed using microelution solid-phase extraction coupled with liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry.

Results

A significant increase in FMD and reduction in 24 h ambulatory systolic BP were found in the WBB group compared with the placebo group (0.86%; 95% CI: 0.56, 1.17, P < 0.001; −3.59 mmHg; 95% CI: −6.95, −0.23, P = 0.037; respectively). Enhanced immediate recall on the auditory verbal learning task, alongside better accuracy on a task-switch task was also found following WBB treatment compared with placebo (P < 0.05). Total 24 h urinary (poly)phenol excretion increased significantly in the WBB group compared with placebo. No changes in the CBF or gut microbiota composition were found.

Conclusions

Daily intake of WBB powder, equivalent to 178 g fresh weight, improves vascular and cognitive function and decreases 24 h ambulatory systolic BP in healthy older individuals. This suggests that WBB (poly)phenols may reduce future CVD risk in an older population and may improve episodic memory processes and executive functioning in older adults at risk for cognitive decline.

Clinical Trial Registration number in clinicaltrials.gov: NCT04084457.

Keywords: wild blueberry, polyphenol, cognition, vascular function, gut microbiota, flow-mediated dilation, cerebral blood flow, metabolomics, nutrition, older adults

Introduction

The risk of developing both cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases increases with aging. Adults aged 60 y and above have a particularly high increased rate of cognitive decline [1]. In parallel, endothelial function is known to decrease with increasing age, and endothelial dysfunction is associated with CVD development [2]. Growing evidence from epidemiological and human intervention trials indicates that (poly)phenols may have cardioprotective properties as well as the ability to improve cognitive function [[3], [4], [5]]. Blueberries are high in a subgroup of (poly)phenols known as anthocyanins, as well as other phenolic compounds such as procyanidins, flavonols, and phenolic acids [6,7]. Previous randomized control trials (RCTs) have shown beneficial effects of daily blueberry consumption on executive functioning and episodic memory following at least 6 wk of daily consumption in healthy older adults [[8], [9], [10], [11], [12]]. Sustained improvements in flow-mediated dilation (FMD) have also been shown after 4- and 24-wk daily consumption of the equivalent to 200 and 150 g fresh blueberries in healthy males and individuals with the metabolic syndrome, respectively [13,14]. It has been hypothesized that improvements in vascular function may influence cognitive performance, for example, through changes in cerebral blood flow (CBF) [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]]. Previous research has shown that an increase in grey matter perfusion in the parietal and occipital lobes was measured using fMRI, following 12-wk daily blueberry supplementation in older adults [22]. Similarly, following 4-mo WBB consumption, in older adults with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), an increase in neural activity during a memory task was observed [23].

Maintaining a healthy gut microbiota may be another important factor influencing CVD risk and cognitive function, in particular in older populations [[24], [25], [26]]. Growing evidence suggests that (poly)phenol-rich foods may influence gut microbiota diversity and composition [27], while the gut microbiota significantly impacts (poly)phenol metabolism, [28,29]. However, very little is known on whether blueberry consumption in particular can modulate the gut microbiota, except for a small study in 20 healthy men, which found an increase in the abundance of Bifidobacterium spp. following consumption of 25 g daily freeze-dried WBB powder for 6 wk [27].

To our knowledge, no study has investigated the effects of daily blueberry (poly)phenol consumption on cognition and vascular function simultaneously in a healthy older population, while investigating the potential mechanisms of action by measuring changes in CBF and gut microbiota diversity and composition. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effects of daily WBB (poly)phenol consumption on vascular function and cognitive performance in healthy older individuals. To gain insights on the potential mechanisms underlying these effects, we assessed the relationship between changes in clinical parameters, gut microbiota diversity and composition, and plasma, and urinary (poly)phenol metabolites.

Subjects and Methods

Intervention study subjects

Sixty-one healthy older adults were recruited from London, inclusion criteria: healthy men and women aged 65–80 y; BMI 18–35 kg/m2, able to understand the nature of the study and willing to give written informed consent. Exclusion criteria: manifest CVD including coronary artery diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, and peripheral arterial disease; hypertensive (BP >140/90 mmHg); diabetes mellitus; metabolic syndrome, as defined by the WHO [30]; acute inflammation (i.e., increases in cytokines, acute phase proteins, and chemokines), end-stage renal disease or malignancies; have any known cognitive impairments, dyslexic or unable to complete the cognitive function tasks for any reason (i.e., visual impairments); lost more than 10% of their weight in the past 6 mo; allergies to berries or other foods provided during the study (i.e., the standardized breakfast); taking blood pressure (BP) or lipid altering medication (or any other relevant medications); subjects already taking vitamin or minerals at a dose <200% of the UK RNI, or evening primrose/algal/fish oil supplements were asked to maintain habitual intake patterns and advised not to stop taking or begin new supplements during the study. Female participants were postmenopausal and not taking hormone replacement therapy.

Study design

A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled parallel design study was conducted in 61 healthy older individuals to investigate the effects of daily WBB (poly)phenol consumption on vascular and cognitive function. Randomization was conducted using a computerized research randomizer (www.randomizer.org), generated by one of the researchers conducting the study, using blinded treatment codes provided by the sponsor. All research staff involved in the collection and the analysis of the data remained blinded to the treatment randomization until all aspects of the study were complete, including the statistical analysis. No blocking or stratification was used. Participants received 26 g freeze-dried WBB powder (equivalent to 178 g fresh WBB) containing 302 mg anthocyanins, or an appearance, taste, and macronutrient, fiber and vitamin C–matched placebo containing 0 mg anthocyanins (Table 1). Treatment powders were given to the participants in an opaque sachet, to consume mixed with water once a day. Participants were asked to keep the sachets in their freezer once they arrived home with them, to minimize (poly)phenol degradation, and compliance was assessed using empty sachet returns. Participants were asked to maintain their normal dietary and exercise habits throughout the duration of the study, and diet was assessed using food diaries throughout the study.

TABLE 1.

Nutritional and phytochemical content of the freeze-dried WBB and placebo powder

| Wild blueberry powder (26 g) | Placebo powder (26 g) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total fat (g) | 1 | 0 |

| Protein (g) | 0.55 | 0 |

| Total carbohydrates (g) | 23.6 | 17.6 |

| Fructose | 9.01 | 9.23 |

| Glucose | 8.70 | 8.32 |

| Calories (kcal) | 106 | 100 |

| Dietary fiber, total (g) | 4.06 | 5.17 |

| Insoluble fibers (g) | 3.02 | 4.16 |

| Soluble fiber (g) | 1.05 | 1.01 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 87 | 90 |

| Anthocyanins (mg) | 302 | 0 |

| Chlorogenic acid (mg) | 202.1 | 0 |

Placebo treatment information from Nieman et al. [65] and WBB information provided by WBANA. The 26 g of freeze-dried WBB is equivalent to 178 g of fresh WBB. WBB, wild blueberry.

Because of the mechanistic nature of this study, aiming to measure vascular function and cognition within the same volunteers at the same time, we conducted an RCT with multiple primary outcomes. The primary outcomes were endothelial function, measured by flow-mediated vasodilation, using high-resolution ultrasound, and cognitive function, measured as a battery of 5 tasks (Reys Auditory Verbal Learning Task (AVLT), Corsi blocks task, Serial 3s and 7s subtraction tasks, and switching task). Secondary outcomes were arterial stiffness, measured as carotid–femoral pulse-wave velocity (PWV) and augmentation index (AIx) using applanation tonometry (Sphygmocor), 24 h ambulatory and office BP, and CBF measured using nonimaging transcranial Doppler ultrasound, plasma lipids (cholesterol, glucose, and other safety parameters such as liver function, kidney function, full blood count), plasma and urine polyphenol metabolites, mood measured as the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), gut microbiota diversity, and composition.

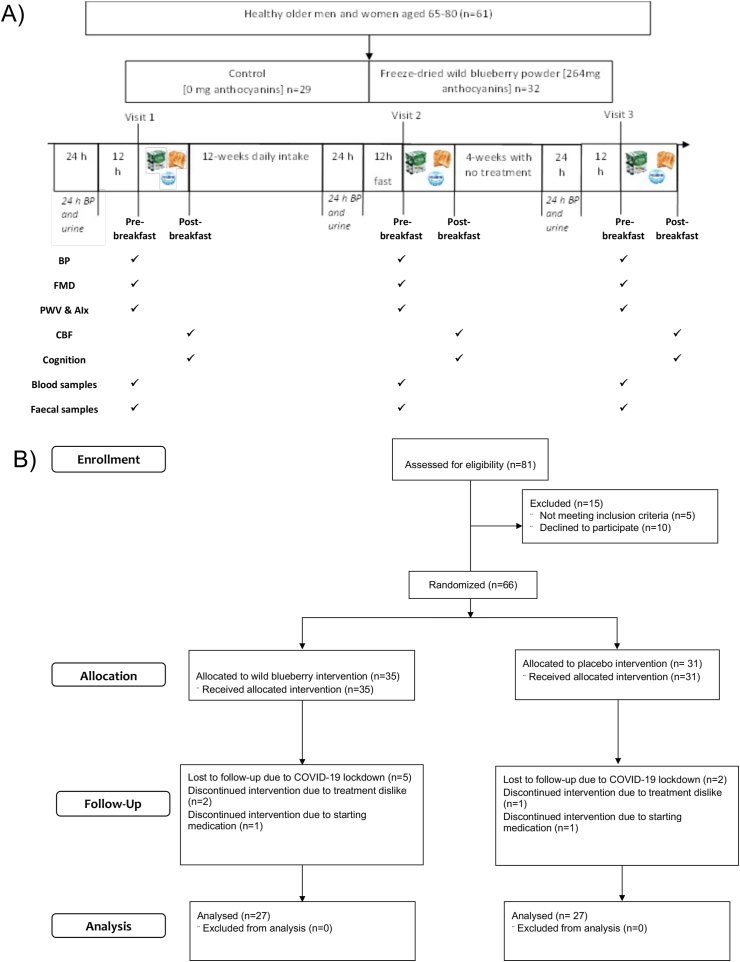

The day before coming in for their study visit (24 h before), participants attended the metabolic research unit (MRU) to be fitted with a 24-h ambulatory BP monitor and were given a urine collection kit (3 L opaque container in a cool bag with ice blocks). They were also asked to collect a fecal sample before their study visit, using a collection kit provided (OMNIgene·GUT, DNA Genotek). The following day, once the participants’ 24 h monitors were removed, they rested supine for 10 min and then measurements of BP, FMD, arterial stiffness, and blood samples were collected. Participants were then given breakfast before completing the cognitive battery along with CBF measurements. The low-fat and low-(poly)phenol breakfast consisted of 2 slices of medium white toast spread thinly with low-fat Philadelphia with a 120 g low-fat Activia vanilla yogurt container (Activia, Danone). CBF was measured for 10 min in a resting, seated position. Participants then completed the cognitive battery lasting ∼45 min, and during one of the tasks (task-switching) CBF was measured again for 10 min. Participants then went home and consumed the intervention treatment, either placebo or WBB, for 12 wk. At the end of the 12 wk, participants returned and all measurements were repeated. In addition, participants attended a followup visit 1 mo after completing the treatment, involving the same procedures stated above, to investigate whether any effects of the treatment remain without consumption (Figure 1). The study was conducted from December 2018 to March 2020, and it has been registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04084457). The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, with all volunteers providing informed consent. All procedures involved were approved by the King’s College London Research Ethics Committee (RESC reference: HR-18/19-9091).

FIGURE 1.

(A) Study design. (B) Flow diagram outlining study activity and participant numbers throughout the process. ∗Due to COVID-19 pandemic and research disruptions, 7 out of 61 participants did not complete their 12-wk followup study visit. Abbreviations: AIx, augmentation index; BP, blood pressure; CBF, cerebral blood flow; FMD, flow-mediated dilation; PWV, pulse-wave velocity.

Dietary assessment of background diet

To assess habitual dietary intake, the European Prospective Investigation on Cancer (EPIC) University of Cambridge, 7-d food diaries were completed. Participants were asked to record all food and drinks consumed over the 7-d period in as much detail as possible. The food diaries were put into food codes following a standardized protocol by trained coders using Nutritics software (Nutritics Professional Diet Analysis, version 3.74; Nutritics Ltd). The average daily macro- and micronutrient composition of participants’ diets were analyzed with data from the McCance and Widdowson’s “The Composition of Foods Integrated Dataset (CoFID) 2015” (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/composition-of-foods-integrated-dataset-cofid). (Poly)phenol intake was then assessed using an existing comprehensive database compiled at King’s College London, including data from the Phenol-Explorer (http://phenol-explorer.eu/) and the USDA database (https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/) by matching up the food codes generated from Nutritics software to the available food content data in the (poly)phenol content database.

Biochemistry analysis

Blood samples were collected by venepuncture using a 21-G butterfly needle (Beckton Dickinson). The blood samples were collected into vacutainer tubes including green top heparin tubes (6 mL, for plasma (poly)phenols- spares), purple top EDTA tubes (10 mL, for plasma (poly)phenols), grey top fluoride oxalate tubes (3 mL, for blood glucose levels), purple top EDTA (3 mL, for full blood count), red top serum separator tubes (8.5 mL, for blood lipids and liver function), PAXgene tubes (PreAnalytiX, 2.5 mL, for intracellular RNA analysis), glass cell preparation tubes (8 mL, for peripheral blood monocytes). Plasma samples for (poly)phenol analysis were spiked with 2% formic acid and frozen at −80°C. All clinical parameters, including total cholesterol, LDL and HDL cholesterol, triacylglycerols (TAG), glucose, glycated hemoglobin, and whole blood count, were analyzed according to standard procedures in an accredited laboratory (Affinity Biomarker Labs).

Wild blueberry powder and placebo interventions

The WBB interventionconsisted of 100% freeze-dried WBB. The placebo is an appearance, taste and macronutrient, fiber and vitamin C–matched powder containing blueberry flavoring and aroma, coloring (1.05% purple lake, 0.75% red lake, 0.45% blue 2 lake, 0.03% red dye, 0.008% blue 2 dye), glucose, fructose, citric acid, ascorbic acid, cellulose, fibersol-2, xanthan gum, pectin, and silica (Table 1). Methods used for anthocyanin and chlorogenic acid (5-O-caffeoylquinic acid) quantification of the WBB powder were previously described [7], with some minor modifications. Briefly, 2 g freeze-dried WBB powder was weighed and extracted 3 times with acidified methanol (0.1% HCl in MeOH). Samples were vortexed for 5 min, sonicated for 5 min in an ultrasonic bath (Fisher Scientific), and centrifuged at room temperature for 14 min at 1800 × g. The supernatants were combined and filtered. Samples were then analyzed using high pressure liquid chromatography diode-array detector (HPLC) using a method previously described, with some modifications [31]. Individual anthocyanins were separated by an Agilent 1100 series HPLC system (Agilent Technologies) equipped with a diode-array detector and a Poroshell 120 EC-C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 2.7 μm particle size; Agilent Technologies). The separation was accomplished at 40°C with the injection volume of 5 μL. The mobile phases A and B were acidified water (1% formic acid, v/v) and acidified acetonitrile (1% formic acid, v/v). The gradients were as follows: 0–5 min, 5% B; 5–35 min, 5%–17% B; 35–50 min, 17%–27% B; 50–60 min, 27%–90% B; 60–65 min, 90% B; 65–70 min, 90%–5% B; 70–80 min, 5% B, with a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The eluate was monitored at 520 nm for all the samples. Calibration curves were obtained by using authentic standards.

Flow-mediated dilation

FMD of the brachial artery was the primary outcome of the study, along with cognitive performance. FMD was measured as previously described [32] and analyzed using a semi-automated edge-detection software (Brachial Analyzer, Medical Imaging Applications). In short, participants rested in a supine position for 15 min, in a temperature-controlled room. The brachial artery was imaged longitudinally at 2–10 cm proximal to the antecubital fossa. After baseline images were recorded, a BP cuff placed around the forearm was inflated to 180 mmHg. After 5 min of occlusion, the pressure was released to induce reactive hyperemia, with an image collection at 20, 40, 60, and 80 s postocclusion. A single researcher, blinded to the treatments, analyzed all FMD images. FMD was calculated at each time point as maximal relative diameter gain relative to baseline and expressed as:

| [(diameter post-deflation – diameter baseline)/(diameter baseline)] ×100 |

Arterial stiffness and blood pressure

PWV and AIx were measured using a SphygmoCor CPV Arterial Tonometry system (ScanMed Medical), to assess arterial stiffness. PWV was determined through measurements taken at the carotid and femoral artery as described by Van Bortel [33]. Central BP was also measured using applanation tonometry. Ambulatory BP was measured using TM2430 ABP monitors (A&D Inc) worn for 24 h before each study day. Readings were taken every 30 min during the day and 60 min at night (19:00–7:00). Participants self-reported their physical activity at the times readings were obtained and noted the times they were asleep. A&D Professional Analysis software was used to analyze the average 24-h systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and pulse.

Cognitive testing

E-prime (Psychology Software Tools) was used to display the stimuli and record participants’ responses for all cognitive tasks. The AVLT assesses short-term verbal memory through word list learning and requires participants to recall lists of 15 nouns being presented audibly [34]. AVLT includes various submeasures of verbal memory and interference, calculated according to the previously published methods [35]. The Corsi Blocks task measures visual memory and targets short-term spatial episodic memory [36]. Participants observe a random sequence of blocks lighting up (ranging from 2 to 9 blocks), and the task is to repeat the sequence back in the same order. Serial 3’s and serial 7’s tasks were used to assess working memory. Here, participants were required to mentally subtract 3 from a randomly generated starting number between 800 and 999 and continue subtracting 3 from the answer for 2 min, this was then repeated with 7. Finally, participants completed the task-switching task (TST), which assesses executive functioning, attention, and reaction time, as previously described [37]. Briefly, participants are given a circle with 8 segments, 4 above and 4 below a bold line. A stimulus digit between 1 and 9 (excluding 5) appears in each segment in turn in a clockwise direction, and the participant’s task is to determine whether the stimulus is odd or even when the number is above the bold line, or higher or lower than 5 when below the bold line. Outcome measures were percentage accuracy and reaction time (ms). Finally, subjective mood scores were also collected at the beginning and end of the cognitive battery using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS-NOW) [38]. The PANAS-NOW is a self-report measure of positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA), with 10 positive and 10 negative mood states. Participants were asked to rate the degree to which they were currently experiencing each item, on a 5-point Likert scale.

Assessment of CBF using transcranial Doppler ultrasound

CBF was measured using nonimaging transcranial Doppler ultrasound (EZ-Dop, DWL, ScanMed medical instruments). We placed a 2-MHz ultrasound probe into an adjustable Diamon probe holder (DWL, Compumedics Germany CmbH, Singen) and placed securely onto the participant’s head on top of the temporal bone acoustic window. First, the signal was found on the right side of the middle cerebral artery using the waveform interpretation at a depth between 50 and 56 mm. We took a CBF reading of mean blood flow velocity (BFV) and pulsatility index (PI) every minute for 10 min while the participant was in a resting state. Subsequently, an active CBF measurement was taken while the participants were performing the cognitive task TST.

Quantification of plasma and urinary (poly)phenol metabolites using liquid chromatography–MS

Plasma samples were obtained by whole blood centrifugation with EDTA vacutainers (10 mL) at 1800 × g for 15 min at 4°C and spiked with 2% formic acid. For the 24 h urine collection, plastic containers (3 L) were used, and the volume was measured using a volumetric cylinder. Formic acid was added to the urine samples to yield a 2% concentration. Samples were stored at −80°C until analysis. These samples were thawed and processed using microelution solid-phase extraction as previously described [39]. Once the samples were washed and the compounds eluded in a collection plate (Waters), samples were run through a triple-quadruple mass spectrometer (SHIMADZU 8060, Shimadzu) coupled with a ultra-performance liquid chromatography system (Shimadzu) and the (poly)phenol metabolites were identified and quantified using authentic standards as previously described [39]. A list of the (poly)phenol metabolites investigated, as well as details on the chromatographic and MS conditions used are presented in Supplemental Table S1.

16S rRNA sequencing of fecal microbiota

DNA was extracted from 0.25 g of fecal material using the PowerFecal protocol (Qiagen) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Extracted DNA was quantified using both spectrophotometry, Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and fluorimetry, Qubit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). DNA was standardized to a 5 ng/mL using an automated protocol on a BiomekFX liquid handling robot (Beckman Coulter).

PCR

Five nanograms of DNA was amplified in a reaction volume of 10 mL using 0.5 U of FastStart High Fidelity Taq (Roche), 4.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 mM forward and reverse primer. The size of the amplified products was checked on a 2% agarose. One milliliter of 1 in 100 dilution of PCR product was used in a second round of PCR to add CS adapters (Fluidigm) 0.5 U of FastStart High Fidelity Taq (Roche), 4.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM forward and reverse primer. Barcode addition was QCed using a Tapestation D1000 tape (Agilent). The primers for the amplification of the 16S V3–V4 region were: ACACTGACGACATGGTTCTACACCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG (forward) and TACGGTAGCAGAGACTTGGTCTGACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC (reverse).

Sequencing

An equal volume of each barcoded PCR product was pooled and the final pool diluted to 4 nM. The pooled library was loaded at 7 pM onto a 300 bp paired end MiSeq (Illumina), as per manufacturer’s instructions, generating an average of 57,000 reads per sample.

Power calculation and statistical analysis of vascular and behavioral data

Power calculations were performed for FMD and episodic memory, based on previous human intervention trials using similar WBB treatments [8]. The power for FMD was based on the interindividual variability of the operator (SD = 1%). Assuming a power of 80% and significance level 0.05, the total number of subjects required to provide sufficient power to detect a 1% difference in FMD in a 2-arm parallel study was 40 (n = 20 per arm). In a previous study, this sample size was enough to see significant effects in FMD after 4 wk of daily supplementation with similar amounts of WBB powder [13]. Assuming a 10% drop out (based on previous studies from our group), 22 participants per arm should be recruited. For cognitive function, a medium effect size of d = 0.640 requires a total of 60 participants (n = 30 per arm) to achieve a statistical power of 80%. Our power calculation was based on our previous study that was conducted with similar study design, participant demography, and wild blueberry treatment [8].

Statistical analysis of the vascular and cognitive endpoints was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) v.27. (IBM). Z-scores analysis was conducted to identify outliers within the data set (Z >3.29). Linear mixed modeling (LMM) analysis was used to determine any posttreatment differences between the WBB and control groups. The models included subjects as a random factor, treatment as a fixed factor, and baseline as a covariate. Effects were deemed significant at P < 0.05. The normality of residuals was confirmed for each significant LMM model using Q–Q plots and Shapiro–Wilk analysis. In some cases, the distribution of residuals was observed to deviate slightly from normality; however, LMM is reported to be a robust model [40]. Any observed deviations are reported alongside the LMM result and are further considered in the discussion. Spearman correlations were performed in the R package version 2.5-6 along with heatmaps and correlation graphs.

Bioinformatics

DNA sequences of 16S rRNA amplicons were analyzed using a QIIME 2 Core 2021.2 distribution within a conda environment [41]. Samples were denoized using Dada2. Sequences were trimmed by 19 bp and truncated to 290 and 260 bp for forward and reverse reads, respectively. After denoizing and chimera removal, a total of 15,394 ± 5175 reads were available to assign the taxonomy of each sample. A classifier was trained on the V3/V4 region from the Silva 132 QIIME-compatible-release database using QIIME naïve-Bayes feature classifier. The classification of sequence variants, at 99% similarity, was performed with VSEARCH, reducing the number of spurious taxonomic assignments, ultimately reducing alpha error inflations [42,43]. We further removed sequence variants of chloroplasts or mitochondria (not bacterial or archaeal taxa), and sequences were only found in 1 sample. The output of the preprocessing with QIIME2 was then aggregated as a Phyloseq object for analysis in R.

Alpha diversity was calculated using Phyloseq. Differences in alpha diversity were evaluated using LMM, accounting for the personal differences as a random effect with lmerTest. As major factors affecting the variation in the data, gender, ethnicity, and age were used as covariates in the models. Beta diversity was evaluated using a nonmetric multidimensional scaling ordination of Bray–Curtis distance calculated from total sum scaled data. The significance of ordination was evaluated using Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance with R package vegan 2.5-6. To evaluate differences in the taxonomic composition, we performed multivariable associations with Microbiome Multivariable Associations with Linear Models (MaAsLin 2).

Random Forest classification was performed using the R package Caret (version 6.0-84). Because the 2 classes were not balanced, downsampling was performed before processing. Input variables were scaled and centered. Accuracy was estimated using repeated cross-validation (5-fold, repeated 10 times). The model was trained using 2/3 of the dataset, and the quality of this model was evaluated using predicted sample classification of the remaining 1/3 of the data set. The quality control metrics were calculated using the confusion Matrix function from Caret, which calculates the overall accuracy along a 95% CI, with statistical significance of this accuracy evaluated with a 1-side test comparing the experimental accuracy to the “no information rate.”

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study population

A total of 81 volunteers were recruited and screened, with 66 of these included in the study and randomly allocated a treatment (35 received the WBB powder and 31 the placebo) (Figure 1). Three volunteers withdrew during their first week due to a dislike of their allocated treatment, although no adverse side effects were reported in any volunteer throughout the study. Two volunteers started taking medications toward the end of their intervention and so were excluded, one for high BP and the other for prediabetes symptoms. Overall, 61 participants completed the study; however, due to COVID-related university closures, 7 participants were unable to complete their 12-wk visit and associated data collection. Therefore, data for 54 participants were analyzed on a per-protocol basis. The baseline characteristics of the study population were all within the normal limits (Table 2). Average daily nutrient and (poly)phenol intake at baseline is presented in Supplemental Table S2. There were significant changes in the overall protein intake (−6.61 g/d; P = 0.034) and vitamin A (−414.2 μg/d; P = 0.046) intake of the placebo group between baseline and visit 2 (12 wk later). No other significant dietary changes were found between the visits.

TABLE 2.

Baseline characteristics for both the placebo and wild blueberry treatment groups

| Placebo group Mean (SD) (N = 29) | WBB group Mean (SD) (N = 32) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (M/F) | 12/17 | 12/20 |

| Age | 70.76 ± (3.81) | 69.44 ± (3.48) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.16 (2.59) | 24.57 (2.7) |

| Body fat % | 26.13 (8.27) | 29.36 (7.92) |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 128.36 (10.01) | 128.52 (11.63) |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 79.59 (5.59) | 81.05 (7.86) |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 65.71 (8.86) | 65.94 (9.65) |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.12 (0.78) | 1.83 (0.47) |

| LDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.80 (1.07) | 3.90 (1.17) |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 4.72 (0.41) | 4.50 (0.58) |

| FMD (%) | 4.11 (1.14) | 3.62 (1.53) |

| PWV (m/s) | 8.47 (2.35) | 7.94 (3.07) |

| AIx @ HR75(%) | 29.4 (11.0) | 27.8 (7.11) |

| Blood flow velocity (cm/s) | 53.6 (7.95) | 54.9 (7.23) |

| Pulsatility index (cm/s) | 1.18 (0.27) | 1.02 (0.17) |

AIx, augmentation index; BP, blood pressure; FMD, flow-mediated dilation; PWV, pulse-wave velocity; WBB, wild blueberry.

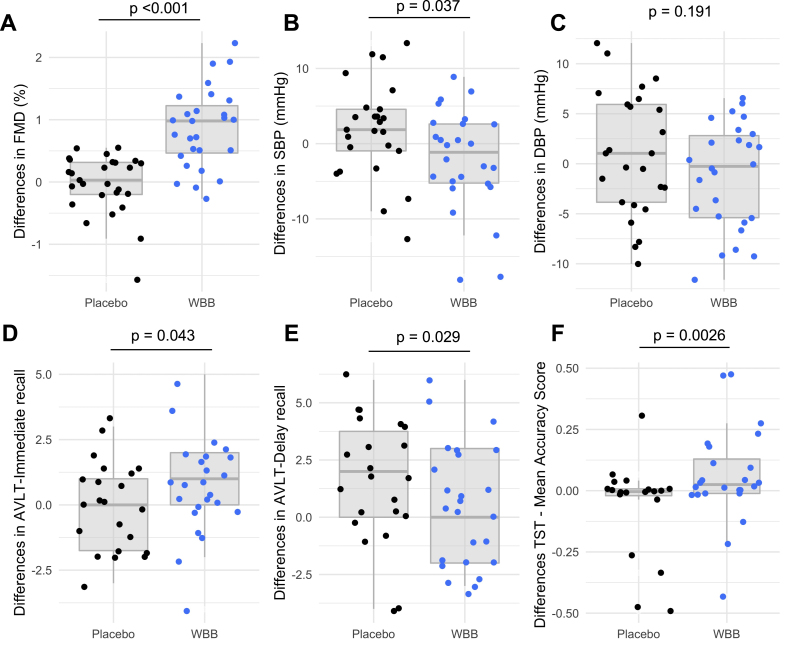

Wild blueberry intervention improved vascular function

The primary outcome was differences in FMD following 12 wk of daily supplementation with either placebo or WBB. FMD was significantly higher in the WBB group compared with the placebo after 12 wk by 0.86 % (95% CI: 0.56, 1.17, P < 0.001) (Figure 2A). In addition, there was a significant reduction in 24 h systolic BP of −3.59 mmHg following daily WBB consumption for 12 wk, when compared with the placebo (95% CI: −6.95, −0.23; P = 0.037) (Figure 2B). No significant differences in other secondary outcomes were found, including arterial stiffness, 24 h diastolic BP, CBF, blood lipids, or office BP (Figure 2C and Supplemental Table S3).

FIGURE 2.

Differences in vascular and cognitive function of the control group and wild blueberry (WBB)-treated group (n = 27 on each group) at 12 wk following consumption. Flow-mediated dilation (FMD) differences (A) evaluated by linear mixed modeling analysis (<0.001 for an overall WBB treatment effect compared with placebo, adjusted for baseline FMD values as a covariateTotal 24-h (B) systolic blood pressure (SBP) and (C) diastolic blood pressure (DBP) differences following WBB consumption in comparison to placebo. Linear mixed modeling analysis revealed no significance for DBP, and an overall treatment effect in SBP P = 0.037 when compared with the placebo. Baseline blood pressure values were used as a covariate; (D) analysis for mean words recalled for immediate recall (R1) revealed significantly improved performance following WBB consumption in comparison to placebo (P = 0.043). (E) Analysis for mean delayed word recall (R8) revealed a significantly improved performance following placebo consumption relative to WBB (P = 0.029) and (F) analysis for overall TST accuracy scores revealed a significant effect of treatment, with higher overall accuracy for WBB compared with placebo (P = 0.026). AVLT, auditory visual learning task; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FMD, flow-mediated dilation; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TST, task-switching task; WBB, wild blueberry.

Wild blueberry intervention improved some aspects of cognitive function

Significant differences in immediate word recall (R1) were seen following WBB treatment for 12 wk (F(1,46) = 4.321, P = 0.043; Figure 2D), with WBB-treated participants recalling 5.92 words compared with 5.28 words after placebo treatment. Contrary to previous work, no benefits to delayed memory recall were found following WBB treatment, and in fact, the placebo group demonstrated significantly better delayed recall than those treated with WBB (F(1,47) = 5.042, P = 0.029; 9.43 vs. 7.48 words, respectively) (Figure 2E). No significant differences in performance were observed for any other AVLT measure. In the TST, 12 wk of daily WBB treatment led to a significant improvement in the overall accuracy score, equivalent to an 8.5% increase in performance, relative to placebo (F(1,46) = 5.05, P = 0.029; Figure 2F). However, it should be noted that the residuals for the TST model deviated slightly from the assumption of normality (Shapiro–Wilk P < 0.001). No significant differences were seen for other cognitive outcomes or on the mood measure (Supplemental Table S4).

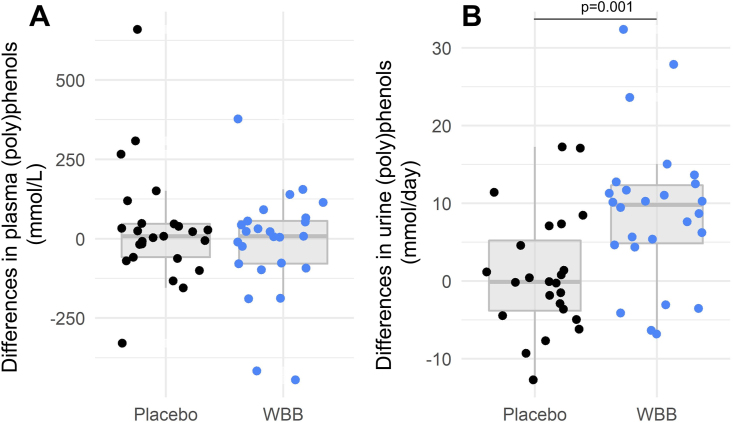

Plasma and urinary (poly)phenol metabolites

A total of 87 phenolic metabolites, potentially related to blueberry consumption, were quantified at baseline and after consumption of the treatments for 12 wk. No significant differences were found at 12 wk in fasting plasma total (poly)phenol metabolites between the WBB treatment and the placebo (P > 0.05) (Figure 3A). Total 24 h urinary (poly)phenol excretion levels were significantly higher in the WBB group compared with the placebo by 1235 μmol (95% CI: 600, 1870; F(50,1) = 13.62, P = 0.001) (Figure 3B). However, it should be noted that the residuals for the 24 h urine model deviated slightly from the assumption of normality (Shapiro–Wilk P = 0.003). At 12 wk, 5 (poly)phenol metabolites including pyrogallol-O-sulfate (P = 0.017), 2 methylpyrogallol-O-sulfate (P = 0.042), 4-methylcatechol-O-sulfate (P = 0.028), 4-methylcatechol (P = 0.011), and isoferulic acid (P < 0.001) were significantly higher in plasma in the WBB group compared with the placebo (Supplemental Table S5) In addition, 2 compounds were significantly lower in the WBB group when compared with the placebo: vanillic acid (P = 0.034) and phenylacetic acid (P = 0.015). Changes in urinary (poly)phenol metabolites are presented in Supplemental Table S6.

FIGURE 3.

Total (A) plasma and (B) 24 h urinary polyphenol metabolites after wild blueberry or placebo consumption for 12 wk, evaluated by linear mixed modeling analysis (n = 27 on each group). No significant differences were found in fasting plasma total (poly)phenols 12 wk after daily consumption of WBB or placebo; however, the WBB group had significantly higher total excreted (poly)phenols in 24 h than the placebo group (P = 0.001).

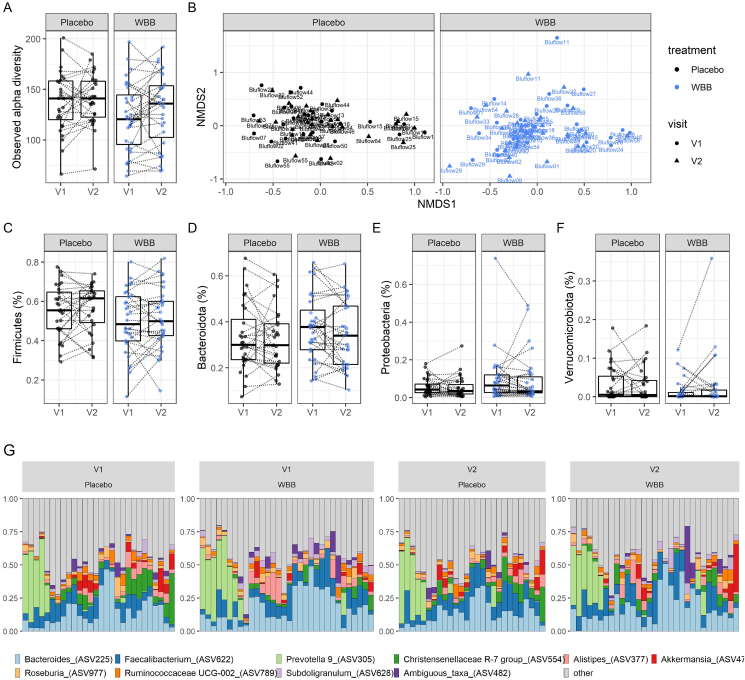

Effects of WBB consumption on gut microbiota diversity and composition

Fecal samples were collected at baseline and 12 wk postintervention and analyzed using 16s rRNA sequencing. Observed alpha diversity significantly increased from baseline in the whole cohort (P = 0.04). However, when the analysis was done individually per treatment group, there were no significant differences (P > 0.05) (Figure 4A). Beta diversity did not differ significantly at baseline between the treatment groups (P > 0.05), and this did not change after 12 wk following either of the treatments (Figure 4B). The taxonomic composition was typical of fecal microbiota from Western individuals with average abundance of 52% Firmicutes (Figure 4C), 34% Bacteroidetes (Figure 4D), 9% Proteobacteria (Figure 4E), and 2% Verrucomicrobiota (Figure 4F). Taxonomy at the phylum level was not statistically different between the different visits, although there was a trend suggesting an increase in the abundance of Firmicutes in the WBB concomitant to a decrease in the abundance of Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria. We then agglomerated ASV at the genus levels to obtain more details about the effects of WBB (Figure 4G). This provided the best resolution for taxonomic evaluations given the number of samples and the DNA sequencing strategy used in this study. The profiles were highly individualized, which suggests that additional factors could influence whether or not an individual will present fecal microbiome composition changes after the intervention. A group of individuals had high Prevotella and low Bacteroides, whereas Prevotella was not detected for some individuals with the highest Bacteroides levels. Multivariable association between clinical metadata and taxonomic abundances showed 3 genera that had their abundance increased by the intervention. These included increases in Ruminiclostridium 9 (P = 0.0007, q = 0.06), Ruminiclostridium 5 (P = 0.002, q = 0.11), and Parabacteroides (P = 0.003, q = 0.20). Although the increase in Parabacteroides abundance was observed in the placebo arm, the increase in Ruminiclostridium 5 and Ruminiclostridium 9 were due to changes in the WBB arm. Other changes were observed following WBB consumption, such as an increase in the levels of Christensenellaceae (P = 0.04, q = 0.80), Eggerthellaceae (P = 0.007, q = 0.36), or Intestinibacter (P = 0.02, q = 0.64) (Supplemental Table S7). Note that false discovery rates were high, and these results will have to be confirmed by other studies.

FIGURE 4.

Differences in fecal microbiota composition between the placebo and the blueberry-treatment group (n = 27 on each group). Alpha (A) and beta (B) diversity are compared, as well as relative abundances for the major phyla quantified in this study: Firmicutes (C), Bacteroidetes (D), Proteobacteria (E), and Verrucomicrobiota (F). The 10 most abundant bacteria genera are presented in (G). WBB, wild blueberry.

Correlations between clinical parameters and plasma (poly)phenol levels

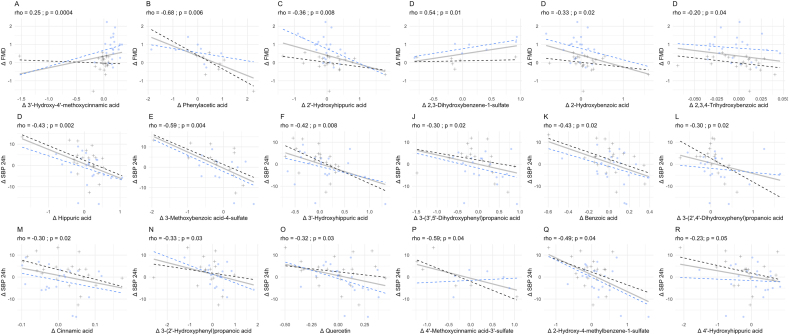

Mechanistic insights on the circulating metabolites responsible for the effect on blood vessel function, BP, and cognition observed in this study were investigated using correlational analysis. A total of 6 (poly)phenol metabolites correlated with changes in FMD; however, only 2 of these were positive correlations, including 3′-hydroxy-4′-methoxycinnamic acid (isoferulic acid) and 2,3-dihydroxybenzene-1-sulfate (pyrogallol-O-sulfate) (Figure 5 and Supplemental Figure 1). Changes in 24-h SBP correlated with changes in 12 (poly)phenol metabolites, including hippuric acid, 3-methoxybenzoic acid-4-sulfate (vanillic acid-4-O-sulfate), 3′-hydroxyhippuric acid, 3-(3′,5′-dihydroxyphenyl)propanoic acid, benzoic acid, 3(2′,4′-dihydroxyphenyl)propanoic acid, cinnamic acid, 3-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)propanoic acid, quercetin, 4′-methoxycinnamic acid-3′-sulfate (isoferulic acid 3-O-sulfate), 2-hydroxy-4-methylbenzene-1-sulfate (4-methylcatechol-O-sulfate), and 4′-hydroxyhippuric acid, all of which were negatively correlated, implying that reductions in 24-h SBP may correlate with increases in circulating (poly)phenol metabolites (Figure 5 and Supplemental Figure 1).

FIGURE 5.

Correlations between plasma metabolites and vascular outcomes (n = 27). Plots show correlations between plasma (poly)phenol metabolites and changes in main cardiometabolic outcomes (FMD and 24 h ambulatory SBP) showing significant changes from WBB treatment; FMD and 24 h SBP. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.001. FMD, flow-mediated dilation; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

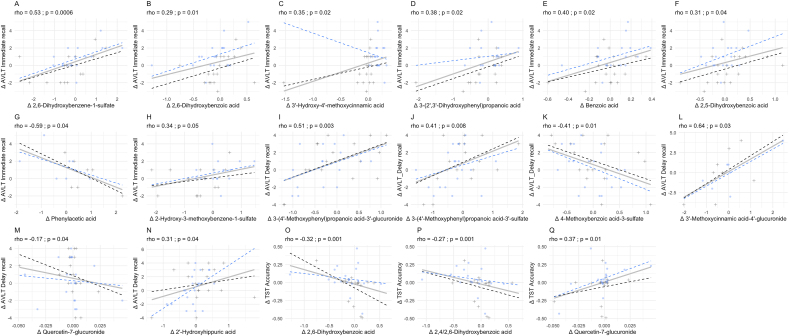

For cognitive function, it was found that 8 (poly)phenol metabolites correlated with changes for immediate recall score, with 7 out of the 8 being positive correlations. These metabolites included 2,6-dihydroxybenzene-1-sulfate (pyrogallol sulfate), 2,6- dihydroxybenzoic acid, 3′-hydroxy-4′-methoxycinnamic acid (isoferulic acid), 3-(2′,3′-dihydroxyphenyl)propanoic acid, benzoic acid, 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid, phenylacetic acid, and 2-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzene-1-sulfate (1-methylpyrogallol-O-sulfate). For delay recall, correlations with 6 plasma metabolites were found, with 4 being positive correlations. These included 3′-hydroxy-4′-methoxyphenyl)propanoic acid-3′-glucuronide (dihydroisoferulic acid 3-glucuronide), 3-(4′-methoxyphenyl)propanoic acid-3′-sulfate (dihydroisoferulic acid 3-O-sulfate), 4-methoxvbenzoic acid-3-sulfate (ferulic acid 4-glucuronide), and 2-hydroxyhippuric acid. For TST accuracy, correlations with 3 plasma metabolites were found 1 of which was positive, including quercetin-7-glucuronide. All correlations with cognitive outcomes are shown in Figure 6 and Supplemental Figure 1.

FIGURE 6.

Correlations between plasma metabolites and cognitive outcomes (n = 27). Plots with correlations between plasma (poly)phenol metabolites and changes in AVLT immediate recall performance showing significant changes from WBB treatment ∗P > 0.05, ∗∗P > 0.001. AVLT, auditory visual learning task; TST, task-switching task.

Correlations between the gut microbiota and clinical outcomes

A number of correlations were found between bacteria and clinical outcomes (for full heatmap please see Supplemental Figure 2). A total of 4 correlations were found with FMD (negative with Parabacteroides and Ruminococus UCG.003, positive with Cocoprocus and Family XIII AD03011), whereas no correlations were found with 24-h SBP. For the TST accuracy, 2 positive correlations were found (Anaerostipes and Eucbacterium xylanophilum), and the same for AVLT immediate recall 2 (1 negative with Ruminoccocus and 1 positive with Butyricicoccus). Finally, AVLT delayed recall had 4 positive correlations with Lachnospiracea UCG.004, Ruminocuccus UCG.005 and UCG.010, and Parabacteroides.

Machine learning discriminates WBB consumption based on changes in plasma or urine (poly)phenols

We tested whether the changes in plasma or urine total (poly)phenols could predict whether a participant has received the placebo or the blueberry treatment using a machine-learning approach. Despite the relatively low number of individuals, the model appropriately classified 80% of the plasma (poly)phenol profiles as belonging to the placebo or the blueberry-treatment group (Supplemental Table S8). This was largely driven by the changes in plasma isoferulic concentrations, although this parameter alone was not sufficient to appropriately classify the samples. The urine polyphenol profiles or the gut microbiome genera profiles were not sufficient to classify the placebo and the blueberry-treatment group.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the impact of blueberry consumption on cognitive and cardiovascular function simultaneously in a group of healthy older adults. We observed that 12 wk daily WBB consumption improved FMD by 0.85% and ambulatory systolic BP decreased by −3.59 mmHg with respect to the control, whereas no effects were found in arterial stiffness and blood lipids. This is consistent with our previous study in younger healthy males where a 1.5% increase in FMD and a 5.6 mmHg decrease in systolic BP was found after 4-wk consumption of similar amounts of WBB [13]. Overall, the changes in FMD and SBP found here are lower, which may be either due to the different study populations or due to other methodological differences. In the present study, the WBB treatment was consumed once daily in the morning for 12 wk, whereas in the previous study it was consumed twice daily for 4 wk, and the placebo was not matched for fiber. Improvements in endothelial function and BP after blueberry consumption have also been reported in individuals with metabolic syndrome [44,45] and hypertension [46], although mixed results exist and a small meta-analysis of 6 RCTs failed to show significant effects in BP after blueberry consumption [47]. It is important to note that most studies measured office BP, and very few studies used ambulatory BP, which is considered the gold standard method to assess an individual’s BP due to the multiple data points collected throughout 24 h, leading to much more reliable and accurate data than a single BP measurement, which is highly variable within individuals [48].

We also found improvements in episodic memory and executive function, in particular better immediate recall of a word list and improvement in switching accuracy, similar to findings from other studies recruiting older adults and supplementing with blueberry treatments over periods ranging from 12 to 48 wk [8,9,11,49]. However, a notable observation from the current study was a lack of any significant difference between WBB and placebo on our delayed recall measure, which contradicts previous findings using the methodologically similar California Verbal Learning Task in older adults >60 y of age [12]. The methodological demands of our study comprising a battery of 4 cognitive tasks, including a demanding TST, alongside a delay of 40 min between the list learning and delayed recall components of the AVLT may explain the overall performance and why no significant differences in delayed recall performance were seen. To date, the array of study designs, dosages, and (poly)phenol content of blueberry interventions hinder between-study comparison, and further work on these behavioral domains are required to confirm their sensitivity, or otherwise, to blueberry interventions. Despite the positive effects of WBB treatment on cognitive and cardiovascular parameters, and the predicted mechanistic link between the 2 outcomes, no changes were seen in CBF following the WBB treatment. The data obtained from our participants in the “resting” phase aligns with other published TCD studies as we saw a reduced BFV with increasing age. However, in our “active” phase (where participants were involved in completing the cognitive task), we saw only 2%–3% increase in BFV compared with studies that have used an exercise intervention, where increases in the range of 7%–24% have been seen or the 8%–10% increase in BFV seen following the administration of 900 mg cocoa polyphenols in a similar population of healthy older volunteers [16,50,51]. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has used TCD as a measure of CBF velocity to test the effects of blueberry (poly)phenols and may indicate that TCD may not have the sensitivity to detect small changes in vasculature arising from blueberry intervention given the intrinsic noisiness of the methods [52,53] and cerebral autoregulation [54].

In the present study, total 24 h urinary (poly)phenol metabolites significantly increased in the WBB group when compared with placebo following 12-wk daily consumption. Total plasma metabolites did not significantly change after 12 wk, although 5 individual metabolites increased significantly. As the blood collection took place 24 h after consumption of the last blueberry sachet, many of the blueberry-derived metabolites had likely already disappeared from circulation. This could explain why we only saw positive correlations between changes in FMD and plasma isoferulic acid and pyrogallol-O-sulfate. However, overall, there were 13 correlations between plasma metabolites and changes in 24-h SBP and 11 metabolites correlating with the improvements in cognition after WBB consumption. Interestingly, the metabolites that correlated with FMD, SBP, and cognitive outcomes were different, except for pyrogallol sulfate, which correlated both with FMD and TST accuracy. In our previous work, we showed that a mixture of the blueberry-derived plasma metabolites correlating with improvements in FMD after 4 wk daily consumption, of which 7 metabolites were also correlated with BP and cognitive outcomes in this study, improved vascular function in an FMD animal model [13]. Mechanistic studies are needed to understand whether mixtures and individual metabolites are the key bioactive compounds improving vascular function and cognition after blueberry consumption.

The potential mechanisms by which blueberry (poly)phenols may positively affect vascular function and cognitive performance, as reported in this study, are still largely unknown. In the present study, no significant changes in gut microbiota diversity and composition were observed in the blueberry group when compared with the placebo. However, the observed alpha diversity significantly increased from baseline in the whole cohort, likely driven by the blueberry arm. Increases in beneficial bacteria such as Ruminiclostridium and Christensellenacea were also found among volunteers in the wild blueberry arm. Furthermore, most of the bacteria correlating positively with the improvements in FMD and cognition belong to the butyrate producer Clostridium cluster of the phylum Firmicutes, including Coprococcus and Family XIII AD03011, which correlated positively with FMD: Anaerostipes, Eucbacterium Xylanophilum, Butyricicoccus, Lachnospiracea UCG.004, Ruminocuccus UCG.005, and UCG.010, which correlated with cognitive outcomes including TST accuracy and AVLT. A key proposed mechanism of action related to the improvements in vascular function by (poly)phenol-rich foods is by mediation of nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability [55,56]. In our previous work, acute improvements in FMD after blueberry consumption correlated with decreased neutrophil NADHP oxidase activity, and increases in blueberry-derived (poly)phenol metabolites were independent predictors of changes in gene expression linked to biological processes involved in cell adhesion, migration, immune response, and cell differentiation [7,13]. Similarly, a number of mechanistic studies also suggest that butyrate may improve endothelial function via a NO-mediated mechanism, including improvements in monocyte–endothelial interactions, macrophage lipid accumulation, smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, and lymphocyte differentiation and function [57,58]. Butyrate has also been shown to improve cognitive function and exert neuroprotective effects in experimental models [59,60]. Future work is needed to investigate whether butyrate may be a key player in the mechanisms of action of blueberry (poly)phenols.

The improvements seen here in vascular function have clinical significance, as according to recent meta-analyses, a 0.85% increase in FMD translates to a 8.5%–11% decreased risk of developing CVD [[61], [62], [63]], whereas a decrease in BP of 3.6 mmHg would translate into a 7% lower risk of CVD events [64]. The relatively modest improvements in episodic memory and executive function seen in our study highlight the need for further substantiation of these effects before a firm conclusion on risk reduction from flavonoid-rich interventions could be drawn.

Machine-learning algorithms have recently been shown to be very useful in stratifying patients or predicting the success of nutritional interventions from individual characteristics. Our results provide a proof of principle that this could be the case for (poly)phenol intake, with the changes in the plasma (poly)phenol metabolome being able to predict whether participants were enrolled on the blueberry or placebo arm in our study, despite the small sample size. No such predictive power was found for the urine (poly)phenols or gut microbiome data, indicating that plasma may be a better predictor of (poly)phenol consumption.

There are some key limitations of this research, including that the results are limited to a healthy older population, therefore cannot be directly extrapolated to all segments of the general population. We did not have access to an MRI machine, which would have potentially been a more sensitive measure of CBF. We did not investigate the factors affecting the high interindividual variability in response to the intervention we observed, which could be due to differences in absorption, metabolism, or gut microbiota composition across our population. We also acknowledge the inflated risk of type 1 error because of the number of statistical tests conducted. Although LMM is known to be a robust statistical test, residuals were observed to deviate from the assumption of normality is some cases that may limit the statistical reliability of those outcomes. Following the per-protocol exclusions, the low number of participants in the cognitive analyses means that the study may have been slightly underpowered. In conclusion, long-term consumption of a dietary achievable amount of WBB was observed to enhance vascular and cognitive function in older adults and may be a plausible and cost-effective dietary-based strategy to tackle the burden of age-related cognitive decline and vascular dysfunction. Our study findings indicate that gut microbiota and vascular blood flow may play important roles in mediating the cognitive benefits shown by the consumption of (poly)phenol-rich foods. Further large-scale studies are needed to confirm the findings of this small-scale investigation, and to explore the exact mechanisms of action

Funding

This work was funded by an unrestricted grant to the ARM and CW from the Wild Blueberry Association of North America. YX and ZZ were funded by King’s-CSC PhD studentships. The funders of this study had no input on the design, implementation, analysis or interpretation of the data. The authors received, by way of a gift, the experimental test products from the Wild Blueberry Association of North America.

Data Availability

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request pending application and approval.

Conflicts of interest

None of the authors declared any other conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors‘ responsibilities were as follows – EW, SH, CW, and ARM: designed the study and drafted the manuscript; EW, SH, and NA: carried out data collection; EW and SH: conducted the analysis of the vascular and cognitive behavioral data; RM: conducted the bioinformatic analysis of the gut microbiota and the correlation analysis between outcomes; FF: provided support and training for the analysis of TCD; YX, EW, and SH: conducted the analysis of plasma and urine (poly)phenols; ZZ: conducted the analysis of (poly)phenols in the wild blueberry intervention; LB: provided support with data analysis and contributed to the editing of the manuscript; ARM and CW: shared the primary responsibility for the final content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajcnut.2023.03.017.

Contributor Information

Claire Williams, Email: claire.williams@reading.ac.uk.

Ana Rodriguez-Mateos, Email: ana.rodriguez-mateos@kcl.ac.uk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Whitley E., Deary I.J., Ritchie S.J., Batty G.D., Kumari M., Benzeval M. Variations in cognitive abilities across the life course: cross-sectional evidence from understanding society: the UK Household Longitudinal Study. Intelligence. 2016;59:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2016.07.001. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heiss C., Rodriguez-Mateos A., Bapir M., Skene S.S., Sies H., Kelm M. Flow-mediated dilation reference values for evaluation of endothelial function and cardiovascular health. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023;119(1):283–293. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvac095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martini D., Marino M., Angelino D., Del Bo C., Del Rio D., Riso P., et al. Role of berries in vascular function: a systematic review of human intervention studies. Nutr. Rev. 2020;78(3):189–206. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuz053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hein S., Whyte A.R., Wood E., Rodriguez-Mateos A., Williams C.M. Systematic review of the effects of blueberry on cognitive performance as we age. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2019;74(7):984–995. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glz082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamport D.J., Williams C.M. Polyphenols and cognition in humans: an overview of current evidence from recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Brain Plast. 2021;6(2):139–153. doi: 10.3233/BPL-200111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michalska A., Lysiak G. Bioactive compounds of blueberries: post-harvest factors influencing the nutritional value of products. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16(8):18642–18663. doi: 10.3390/ijms160818642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez-Mateos A., Cifuentes-Gomez T., Tabatabaee S., Lecras C., Spencer J.P. Procyanidin, anthocyanin, and chlorogenic acid contents of highbush and lowbush blueberries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60(23):5772–5778. doi: 10.1021/jf203812w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whyte A.R., Cheng N., Fromentin E., Williams C.M. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study to compare the safety and efficacy of low -dose enhanced wild blueberry powder and wild blueberry extract ThinkBlue™ in maintenance of episodic and working memory in older adults. Nutrients. 2018;10(6):660. doi: 10.3390/nu10060660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller M.G., Hamilton D.A., Joseph J.A., Shukitt-Hale B. Dietary blueberry improves cognition among older adults in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018;57(3):1169–1180. doi: 10.1007/s00394-017-1400-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schrager M.A., Hilton J., Gould R., Kelly V.E. Effects of blueberry supplementation on measures of functional mobility in older adults. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2015;40(6):543–549. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2014-0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rutledge G.A., Sandhu A.K., Miller M.G., Edirisinghe I., Burton-Freeman B.B., Shukitt-Hale B. Blueberry phenolics are associated with cognitive enhancement in supplemented healthy older adults. Food Funct. 2021;12(1):107–118. doi: 10.1039/d0fo02125c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krikorian R., Shidler M.D., Nash T.A., Kalt W., Vinqvist-Tymchuk M.R., Shukitt-Hale B., Joseph J.A. Blueberry supplementation improves memory in older adults. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58(7):3996–4000. doi: 10.1021/jf9029332. PMID: 20047325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez-Mateos A., Istas G., Boschek L., Feliciano R.P., Mills C.E., Boby C., et al. Circulating anthocyanin metabolites mediate vascular benefits of blueberries: insights from randomized controlled trials, metabolomics, and nutrigenomics. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2019;74(7):967–976. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glz047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curtis P.J., van der Velpen V., Berends L., Jennings A., Feelisch M., Umpleby A.M., et al. Blueberries improve biomarkers of cardiometabolic function in participants with metabolic syndrome-results from a 6-month, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019;109(6):1535–1545. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D.J. Lamport, D. Pal, C. Moutsiana, D.T. Field, C.M. Williams, J.P. Spencer, et al., The effect of flavanol-rich cocoa on cerebral perfusion in healthy older adults during conscious resting state: a placebo controlled, crossover, acute trial, Psychopharmacology (Berl). 232(17) (237) 3227–3234. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3972-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Sorond F.A., Lipsitz L.A., Hollenberg N.K., Fisher N.D. Cerebral blood flow response to flavanol-rich cocoa in healthy elderly humans. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2008;4(2):433–440. PMID 18728792. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamport D.J., Pal D., Macready A.L., Barbosa-Boucas S., Fletcher J.M., Williams C.M., et al. The effects of flavanone-rich citrus juice on cognitive function and cerebral blood flow: an acute, randomised, placebo-controlled cross-over trial in healthy, young adults. Brit. J. Nutr. 2016;116(12):2160–2168. doi: 10.1017/S000711451600430X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson P.A., Wightman E.L., Veasey R., Forster J., Khan J., Saunders C., et al. A randomized, crossover study of the acute cognitive and cerebral blood flow effects of phenolic, nitrate and botanical beverages in young, healthy humans. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2254. doi: 10.3390/nu12082254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Francis S.T., Head K., Morris P.G., Macdonald I.A. The effect of flavanol-rich cocoa on the fMRI response to a cognitive task in healthy young people. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2006;47(Suppl 2):S215–S220. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200606001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brickman A.M., Khan U.A., Provenzano F.A., Yeung L.K., Suzuki W., Schroeter H., et al. Enhancing dentate gyrus function with dietary flavanols improves cognition in older adults. Nat. Neurosci. 2014;17(12):1798–1803. doi: 10.1038/nn.3850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marsh C.E., Carter H.H., Guelfi K.J., Smith K.J., Pike K.E., Naylor L.H., et al. Brachial and cerebrovascular functions are enhanced in postmenopausal women after ingestion of chocolate with a high concentration of cocoa. J. Nutr. 2017;147(9):1686–1692. doi: 10.3945/jn.117.250225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowtell J.L., Aboo-Bakkar Z., Conway M.E., Adlam A.L.R., Fulford J. Enhanced task-related brain activation and resting perfusion in healthy older adults after chronic blueberry supplementation. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2017;42(7):773–779. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2016-0550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boespflug E.L., Eliassen J.C., Dudley J.A., Shidler M.D., Kalt W., Summer S.S., et al. Enhanced neural activation with blueberry supplementation in mild cognitive impairment. Nutr. Neurosci. 2018;21(4):297–305. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2017.1287833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang W.H., Kitai T., Hazen S.L. Gut microbiota in cardiovascular health and disease. Circ. Res. 2017;120(7):1183–1196. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.309715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mu C., Yang Y., Zhu W. Gut microbiota: the brain peacekeeper. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:345. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manderino L., Carroll I., Azcarate-Peril M.A., Rochette A., Heinberg L., Peat C., et al. Preliminary evidence for an association between the composition of the gut microbiome and cognitive function in neurologically healthy older adults. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2017;23:700–705. doi: 10.1017/S1355617717000492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vendrame S., Guglielmetti S., Riso P., Arioli S., Klimis-Zacas D., Porrini M. Six-week consumption of a wild blueberry powder drink increases bifidobacteria in the human gut. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011;59(24):12815–12820. doi: 10.1021/jf2028686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shortt C., Hasselwander O., Meynier A., Nauta A., Fernández E.N., Putz P., et al. Systematic review of the effects of the intestinal microbiota on selected nutrients and non-nutrients. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018;57(1):25–49. doi: 10.1007/s00394-017-1546-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheatham C.L., Nieman D.C., Neilson A.P., Lila M.A. Enhancing the cognitive effects of flavonoids with physical activity: is there a case for the gut microbiome? Front. Neurosci. 2022;16 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.833202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alberti K.G., Zimmet P.Z. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabetic Med. 1998;15(7):539–553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136. 199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pertuzatti P.B., Barcia M.T., Rebello L.P.G., Gómez-Alonso S., Duarte R.M.T., Duarte M.C.T., et al. Antimicrobial activity and differentiation of anthocyanin profiles of rabbiteye and highbush blueberries using HPLC–DAD–ESI-MS n and multivariate analysis. J. Funct. Foods. 2016;26:506–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2016.07.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodriguez-Mateos A., Rendeiro C., Bergillos-Meca T., Tabatabaee S., George T.W., Heiss C., et al. Intake and time dependence of blueberry flavonoid-induced improvements in vascular function: a randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover intervention study with mechanistic insights into biological activity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013;98(5):1179–1191. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.066639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Bortel L.M., Laurent S., Boutouyrie P., Chowienczyk P., Cruickshank J.K., De Backer T., et al. Expert consensus document on the measurement of aortic stiffness in daily practice using carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity. J. Hypertens. 2012;30(3):445–448. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834fa8b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barfoot K.L., May G., Lamport D.J., Ricketts J., Riddell P.M., Williams C.M. The effects of acute wild blueberry supplementation on the cognition of 7–10-year-old schoolchildren. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019;58(7):2911–2920. doi: 10.1007/s00394-018-1843-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lezak M.D., Howiesonm D.B., Bigler E.D., Tranel D. 4th ed. OUP; New York: 2004. Neuropsychol assessment. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessels R.P., van Zandvoort M.J., Postma A., Kappelle L.J., de Haan E.H. The corsi block-tapping task: standardization and normative data. Appl. Neuropsychol. 2000;7(4):252–258. doi: 10.1207/S15324826AN0704_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whyte A.R., Cheng N., Butler L.T., Lamport D.J., Williams C.M. Flavonoid-rich mixed berries maintain and improve cognitive function over a 6-h period in young healthy adults. Nutrients. 2019;11(11):2685. doi: 10.3390/nu11112685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watson D., Clark L.A., Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dominguez-Fernandez M., Xu Y., Yang P.Y.T., Alotaibi W., Gibson R., Hall W.L., et al. Quantitative assessment of dietary (poly)phenol intake: a high-throughput targeted metabolomics method for blood and urine samples. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021;69(1):537–554. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c07055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schielzeth H., Dingemanse N.J., Nakagawa S., Westneat D.F., Allegue H., Teplitsky C., et al. Robustness of linear mixed-effects models to violations of distributional assumptions. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2020;11(9):1141–1152. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.13434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bolyen E., Rideout J.R., Dillon M.R., Bokulich N.A., Abnet C.C., Al-Ghalith G.A., et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37(8):852–857. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rognes T., Flouri T., Nichols B., Quince C., Mahe F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ. 2016;4 doi: 10.7717/peerj.2584. PMID 27781170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prodan A., Tremaroli V., Brolin H., Zwinderman A.H., Nieuwdorp M., Levin E. Comparing bioinformatic pipelines for microbial 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing. PloS One. 2020;15(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Basu A., Du M., Leyva M.J., Sanchez K., Betts N.M., Wu M., et al. Blueberries decrease cardiovascular risk factors in obese men and women with metabolic syndrome. J. Nutr. 2010;140(9):1582–1587. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.124701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stull A.J., Cash K.C., Champagne C.M., Gupta A.K., Boston R., Beyl R.A., et al. Blueberries improve endothelial function, but not blood pressure, in adults with metabolic syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nutrients. 2015;7(6):4107–4123. doi: 10.3390/nu7064107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson S.A., Figueroa A., Navaei N., Wong A., Kalon R., Ormsbee L.T., et al. Daily blueberry consumption improves blood pressure and arterial stiffness in postmenopausal women with pre- and stage 1-hypertension: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Academy Nutr. Dietetics. 2015;115(3):369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu Y., Sun J., Lu W., Wang X., Han Z., Qiu C. Effects of blueberry supplementation on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J. Human Hypertens. 2017;31(3):165–171. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2016.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Millar-Craig M.W., Bishop C.N., Raftery E.B. Circadian variation of blood-pressure. Lancet. 1978;1(8068):795–797. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92998-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McNamara R.K., Kalt W., Shidler M.D., McDonald J., Summer S.S., Stein A.L., et al. Cognitive response to fish oil, blueberry, and combined supplementation in older adults with subjective cognitive impairment. Neurobiol. Aging. 2018;64:147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fisher J.P., Hartwich D., Seifert T., Olesen N.D., McNulty C.L., Nielsen H.B., van Lieshout J.J., Secher N.H. Cerebral perfusion, oxygenation and metabolism during exercise in young and elderly individuals. J. Physiol. 2013;591(7):1859–1870. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.244905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ward J.L., Craig J.C., Liu Y., Vidoni E.D., Maletsky R., Poole D.C., Billinger S.A. Effect of healthy aging and sex on middle cerebral artery blood velocity dynamics during moderate-intensity exercise. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018;315(3):H492–H501. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00129.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sorteberg W., Langmoen I.A., Lindegaard K.F., Nornes H. Side-to-side differences and day-to-day variations of transcranial Doppler parameters in normal subjects. J. Ultrasound Med. 1997;9(7):403–409. doi: 10.7863/jum.1990.9.7.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sorond F.A., Hollenberg N.K., Panych L.P., Fisher N.D. Brain blood flow and velocity: correlations between magnetic resonance imaging and transcranial Doppler sonography. J. Ultrasound Med. 2010;29(7):1017–1022. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.7.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Silverman A., Petersen N.H. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Physiology, cerebral autoregulation. Published online 2023 Mar 15. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL) PMID: 31985976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steffen Y., Schewe T., Sies H. (−)−Epicatechin elevates nitric oxide in endothelial cells via inhibition of NADPH oxidase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;359(3):828–833. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Furuuchi R., Shimizu I., Yoshida Y., Hayashi Y., Ikegami R., Suda M., et al. Boysenberry polyphenol inhibits endothelial dysfunction and improves vascular health. PloS One. 2018;13(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tian Q., Leung F.P., Chen F.M., Tian Y.X., Chen Z., Tse G., et al. Butyrate protects endothelial function through PPARδ/miR-181b signaling. Pharmacol. Res. 2021;169:105681. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xiao Y., Guo Z., Li Z., Ling H., Song C. Role and mechanism of action of butyrate in atherosclerotic diseases: a review. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020;131(2):543–552. doi: 10.1111/jam.14906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang C., Zheng D., Weng F., Jin Y., He L. Sodium butyrate ameliorates the cognitive impairment of Alzheimer's disease by regulating the metabolism of astrocytes. Psychopharmacol. 2022;239(1):215–227. doi: 10.1007/s00213-021-06025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stilling R.M., van de Wouw M., Clarke G., Stanton C., Dinan T.G., Cryan J.F. The neuropharmacology of butyrate: the bread and butter of the microbiota-gut-brain axis? Neurochem. Int. 2016;99:110–132. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ras R.T., Streppel M.T., Draijer R., Zock P.L. Flow-mediated dilation and cardiovascular risk prediction: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013;168(1):344–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shechter M., Shechter A., Koren-Morag N., Feinberg M.S., Hiersch L. Usefulness of brachial artery flow-mediated dilation to predict long-term cardiovascular events in subjects without heart disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2014;113(1):162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Inaba Y., Chen J.A., Bergmann S.R. Prediction of future cardiovascular outcomes by flow-mediated vasodilatation of brachial artery: a meta-analysis. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2010;26(6):631–640. doi: 10.1007/s10554-010-9616-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ettehad D., Emdin C.A., Kiran A., Anderson S.G., Callender T., Emberson J., et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):957–967. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nieman D.C., Gillitt N.D., Guan-Chen G.Y., Zhang Q., Sha W., Kay C.D., Chandra P., Kay K.L., Lila M.A. Blueberry and/or banana consumption mitigate arachidonic, cytochrome P450 oxylipin generation during recovery from 75-km cycling: a randomized trial. Front. Nutr. 7 August 2020;7:121. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request pending application and approval.