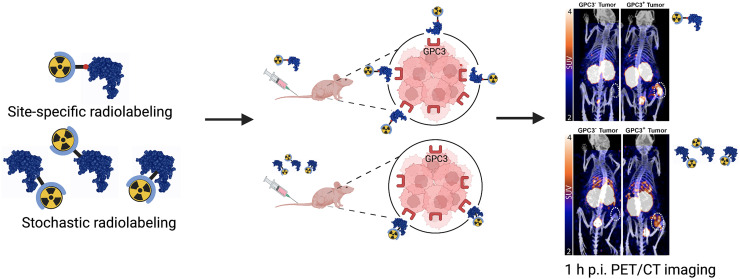

Visual Abstract

Keywords: glypican-3, GPC3, liver cancer, immuno-PET, molecular imaging, Nanobody

Abstract

Primary liver cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths, and its incidence and mortality are increasing worldwide. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for 80% of primary liver cancer cases. Glypican-3 (GPC3) is a heparan sulfate proteoglycan that histopathologically defines HCC and represents an attractive tumor-selective marker for radiopharmaceutical imaging and therapy for this disease. Single-domain antibodies are a promising scaffold for imaging because of their favorable pharmacokinetic properties, good tumor penetration, and renal clearance. Although conventional lysine-directed bioconjugation can be used to yield conjugates for radiolabeling full-length antibodies, this stochastic approach risks negatively affecting target binding of the smaller single-domain antibodies. To address this challenge, site-specific approaches have been explored. Here, we used conventional and sortase-based site-specific conjugation methods to engineer GPC3-specific human single-domain antibody (HN3) PET probes. Methods: Bifunctional deferoxamine (DFO) isothiocyanate was used to synthesize native HN3 (nHN3)-DFO. Site-specifically modified HN3 (ssHN3)-DFO was engineered using sortase-mediated conjugation of triglycine-DFO chelator and HN3 containing an LPETG C-terminal tag. Both conjugates were radiolabeled with 89Zr, and their binding affinity in vitro and target engagement of GPC3-positive (GPC3+) tumors in vivo were determined. Results: Both 89Zr-ssHN3 and 89Zr-nHN3 displayed nanomolar affinity for GPC3 in vitro. Biodistribution and PET/CT image analysis in mice bearing isogenic A431 and A431-GPC3+ xenografts, as well as in HepG2 liver cancer xenografts, showed that both conjugates specifically identify GPC3+ tumors. 89Zr-ssHN3 exhibited more favorable biodistribution and pharmacokinetic properties, including higher tumor uptake and lower liver accumulation. Comparative PET/CT studies on mice imaged with both 18F-FDG and 89Zr-ssHN3 showed more consistent tumor accumulation for the single-domain antibody conjugate, further establishing its potential for PET imaging. Conclusion: 89Zr-ssHN3 showed clear advantages in tumor uptake and tumor-to-liver signal ratio over the conventionally modified 89Zr-nHN3 in xenograft models. Our results establish the potential of HN3-based single-domain antibody probes for GPC3-directed PET imaging of liver cancers.

Primary liver cancer is the third most common cause of cancer death and has an 18% 5-y survival (1). New cases of primary liver cancer are on the rise, with the incidence projected to increase by more than 55% in the next 20 y (2). Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for around 80% of primary liver cancer cases worldwide, affecting over 600,000 individuals annually (3). Chronic hepatitis B virus infection is currently the main contributor to the disease. However, diabetes and obesity-related nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are of growing etiologic concern (4).

MR- and CT-based imaging are the standard of care for diagnosing and surveilling patients with a high risk of developing HCC (5). Although these modalities have been critical in diagnosing HCC, distinguishing treatment effect from residual or recurrent disease remains a challenge. 18F-FDG PET, used in these circumstances for other cancers, is of limited use in HCC because of the heterogeneous glucose uptake by this tumor type (6). As such, HCC tumor-selective or tumor microenvironment–selective imaging agents are needed to address this unmet clinical need.

Technological developments have allowed targeted radionuclide diagnostic agents, as well as β- and α-emitting radionuclide therapies, to play a role in precision oncology (7). Diverse biomolecules, including monoclonal antibodies, antibody fragments, small proteins, peptides, and small molecules, have been explored as tumor-targeting vectors for PET imaging and radiopharmaceutical therapy (8,9).

Glypican-3 (GPC3) is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored heparan sulfate proteoglycan expressed in 75%–90% of HCCs (10). Therefore, it is an attractive HCC-selective target that, if leveraged for molecular imaging, may help characterize postablation lesions and allow for more comprehensive screening, early diagnosis, and posttreatment surveillance. Full-length antibodies specific to GPC3 have been evaluated for immuno-PET imaging in preclinical (11,12) and clinical (13) studies. However, despite good imaging characteristics, the long blood half-life of full-length antibodies precludes same-day imaging, compromising existing patient workflows in the clinic. Furthermore, monoclonal antibodies typically exhibit hepatobiliary excretion, which can result in poor tumor-to-tissue ratios in patients with primary liver tumors. Although a smaller GPC3-specific F(ab′)2 (110 kDa) has been explored for imaging, it was not suited for same-day imaging (14).

Single-domain antibodies, (15 kDa), derived from camelids or sharks (15,16) are alternate scaffolds being explored for PET diagnostics (NCT04674722 and NCT05156515). Notably, one recent report describes the preclinical development of a GPC3-targeting single-domain antibody radiolabeled with 68Ga or 18F for immuno-PET, providing a proof of concept for HCC imaging with GPC3-directed single-domain antibodies (16). This conjugate was prepared using lysine conjugation, which is stochastic. Unlike full-size antibodies, single-domain antibodies have fewer lysine residues for conjugation. Modification of these residues by attaching prosthetic groups may worsen their binding affinity and pharmacokinetic properties. These drawbacks can be mitigated by site-specific conjugation or sequence alteration (17–20).

Here, we engineered the GPC3-specific single-domain antibody HN3 (21) to be compatible with sortase-based site-specific modification (22), which has previously been exploited for site-specific single-domain antibody radiolabeling (23–25), and labeled it with the radionuclide 89Zr for use as a PET probe. The performance of this construct was compared with that of a lysine-conjugated HN3 single-domain antibody that did not require sequence engineering. We determined that both radioconjugates exhibit GPC3-specific tumor targeting in vivo, and the site-specific conjugate has superior performance to the traditional lysine-conjugated HN3 tracer and 18F-FDG.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Production of HN3 Single-Domain Antibody and Bifunctional HN3-Chelate Constructs

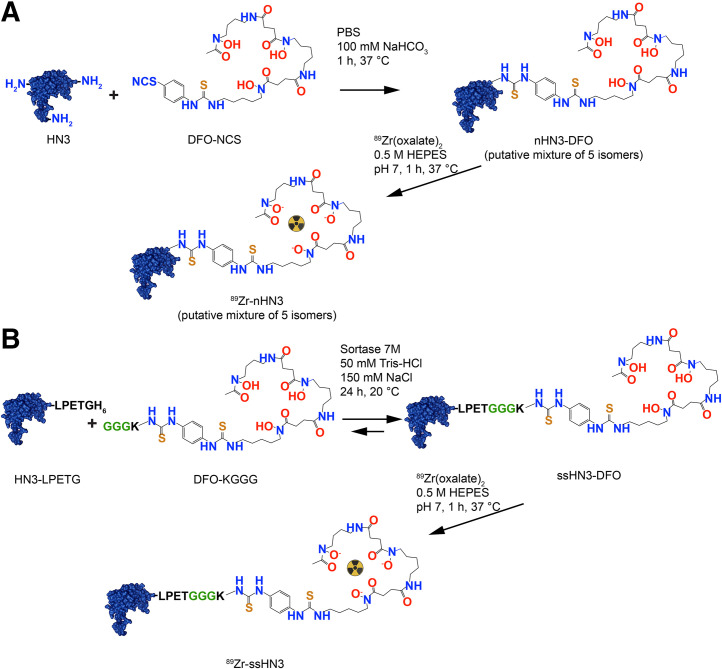

The HN3 human single-domain antibody, containing both -His6 and -FLAG tags at its C terminus, was produced following a protocol previously described (26,27). A full description of HN3 production and plasmid maps of the transformation are provided in Supplemental Figures 1 and 2 (supplemental materials are available at http://jnm.snmjournals.org). A sortase-reactive deferoxamine (DFO) chelator (GGGK-DFO) was prepared as described in Figure 1, Supplemental Scheme 1, and Supplemental Figures 3–6. Site-specific C-terminal conjugation of GGGK-DFO to HN3-LPETG-His6 (28) and stochastic lysine-directed conjugation of DFO to HN3 (29) were accomplished using previously reported methods detailed in the supplemental materials.

FIGURE 1.

Conventional lysine conjugation vs. site-specific conjugation. Shown are synthetic schema and structures of 89Zr-nHN3 (A) and 89Zr-ssHN3 (B). HEPES = 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid; PBS = phosphate-buffered saline.

Biolayer Interferometry

The binding kinetics and equilibria for the binding of native HN3 (nHN3)-DFO and site-specifically modified HN3 (ssHN3)-DFO to recombinant GPC3 were evaluated using biolayer interferometry. Full experimental details are provided in the supplemental materials.

Radiolabeling with 89Zr

Radiolabeling of DFO-conjugated single-domain antibodies was conducted using a modification of established methods (12,29). Gentisic acid (10 μL, 10 mg/mL) was added to a solution of 89Zr(oxalate)2 (40 μL, 92.5 MBq, cyclotron at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center) in oxalic acid. N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid buffer (2 μL, 1 M) was added. A solution of 2 M Na2CO3 was then added until the pH reached 7. ssHN3-DFO or nHN3-DFO conjugate in 0.1 M ammonium acetate (45 μL, 1.5 mg/mL) was added to the mixture, and the reaction was heated for 1 h at 37°C. The reaction mixture was then purified using a PD-10 gel filtration column with phosphate-buffered saline containing bovine serum albumin (1 mg/mL) as the mobile phase. Radiochemical yield and purity were determined by radio–instant thin-layer chromatography with silica gel–impregnated glass microfiber paper strips (Varian) using an aqueous solution of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (50 mM) and NH4OAc (100 mM, pH 5.5) as the mobile phase. An AR-2000 (Eckert-Ziegler) radio–thin-layer chromatography scanner was used to calculate the percentage total activity at the origin.

Saturation Binding Assays

To assess binding affinity, radioligand binding assays were performed as detailed in the supplemental materials by incubating varying amounts of radiolabeled single-domain antibodies with immobilized recombinant GPC3 for 2 h.

Cell Culture

The A431 human epithelioid cancer cell line and the GPC3-positive (GPC3+) HepG2 human hepatoblastoma cell line were purchased from ATCC and cultured according to vendor instructions. A431-GPC3+, a transfected A431 cell line engineered to overexpress GPC3 (30,31), was obtained from Dr. Mitchell Ho (National Cancer Institute). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FetaPlex (Gemini Bio-Products). All cell lines were used within 15 passages.

Murine Subcutaneous Xenograft Models

All mouse experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the National Institutes of Health under protocol ROB-105. Female athymic nu/nu 8- to 10-wk-old mice (Charles River Laboratories) were implanted subcutaneously with 2.5 × 106 HepG2, A431, or A431-GPC3+ cells in a 200-μL solution of phosphate-buffered saline (for A431 and A431-GPC3+) or a 1:1 mixture of Matrigel (Corning) and Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (HepG2). Tumors were grown to approximately 100 mm3 before biodistribution and imaging experiments. HepG2 and A431-GPC3+ cells were chosen for their high expression of GPC3. A431 cells were used as a negative control.

PET/CT Imaging of Mice Bearing A431 or A431-GPC3+ Tumors

Mice bearing A431 or A431-GPC3+ xenografts (n = 3 per tumor type) were injected with 1,961 ± 30 kBq (2.8 μg) of 89Zr-ssHN3 or 1,970 ± 40 kBq (10.9 μg) of 89Zr-nHN3. At 1 and 3 h after injection, images were obtained using PET/CT (BioPET/CT; Sedecal) as follows. The mice were anesthetized using 2% isoflurane, and static PET scans were acquired over 10 min. Whole-body CT scans (8.5 min, 50 kV, 180 μA) were obtained immediately after PET images and were used to provide attenuation correction and anatomic coregistration for the PET scans. PET data were reconstructed using 3-dimensional ordered-subsets expectation maximization and were normalized, decay-corrected, and dead-time–corrected before analysis using MIM software (MIM Software Inc.). After the final imaging time point, the mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, and 12 tissues, including tumor, were collected. All samples were weighed and counted on a γ-counter (2480 Wizard3; Perkin Elmer Inc.). The counts were converted to percentage injected activity (%IA) using a standard solution of known activity prepared from the injection solution. %IA/g was calculated by dividing the activity in each organ by its weight.

Ex Vivo Biodistribution Study in HepG2 Tumor–Bearing Mice

Mice (n = 4) were injected with 89Zr-labeled single-domain antibodies (370 ± 40 kBq/mouse for both the ssHN3 [0.90 μg] and the nHN3 [0.52 μg] conjugate) through a lateral tail vein. The biodistribution of 89Zr-nHN3 and 89Zr-ssHN3 was then evaluated at 1, 3, and 24 h after administration as described in the previous section.

PET/CT Imaging Comparison of 18F-FDG and 89Zr-ssHN3 in Mice Bearing HepG2 Tumors

Mice bearing HepG2 xenografts (n = 4) were kept fasting for 4 h before injection of approximately 4,180 ± 240 kBq of 18F-FDG. After 1 h, PET/CT images were obtained and processed as described above. One day later, the same mice were injected with 3,680 ± 130 kBq (5.1 μg) of 89Zr-ssHN3 and imaged 1, 3, and 24 h after injection. For comparison, another set of mice bearing HepG2 xenografts (n = 4) was injected with 4,110 ± 40 kBq (6.1 μg) of 89Zr-nHN3 and imaged after 1, 3, and 24 h. After the 24-h image acquisition, the mice were euthanized and the ex vivo biodistribution of the 89Zr conjugates was evaluated.

Statistical Analysis

Statistics were analyzed using Prism (version 9.0, GraphPad Software). Organ uptake, tumor volume, SUV, and stability were compared using the Student t test (unpaired, parametric, 2-tailed).

RESULTS

Synthesis of ssHN3 and nHN3 DFO Conjugates Was Successful

We successfully prepared derivatives of the GPC3-targeting single-domain antibody HN3 using previously reported methods (28,29). Analysis of the original single-domain antibodies and resulting DFO conjugates by size-exclusion high-performance liquid chromatography and high-resolution mass spectrometry confirmed their purity and identity (Supplemental Figs. 3–14). Synthetic schema for nHN3 and ssHN3 are presented in Figure 1. The nHN3 construct was conjugated to the commercially available bifunctional chelator DFO isothiocyanate using stochastic lysine labeling methods, yielding nHN3-DFO. Mass spectrometry analysis of this conjugate indicated a DFO:HN3 ratio of 0.2:1, consistent with minimal modification of the HN3 single-domain antibody. The ssHN3 single-domain antibody was conjugated specifically at the -LPETG sequence to GGGK-DFO, yielding ssHN3-DFO, which has a 1:1 HN3:DFO ratio. This conjugation reaction also results in cleavage of the -His6 sequence from the C terminus of ssHN3.

Single-Domain Antibody Radioconjugates Were Synthesized with Satisfactory Radiochemical Yield and Purity

Both conjugates were successfully radiolabeled with 89Zr using 89Zr-oxalate, resulting in 10%–30% yield. After radiolabeling, both conjugates exhibited similar specific activities, varying on the basis of the radiolabeling efficiency (610 ± 140 kBq/μg for ssHN3 and 520 ± 240 kBq/μg for nHN3), and the radiochemical purity of both conjugates was found to be more than 99% using instant thin-layer chromatography (Supplemental Figs. 15 and 16).

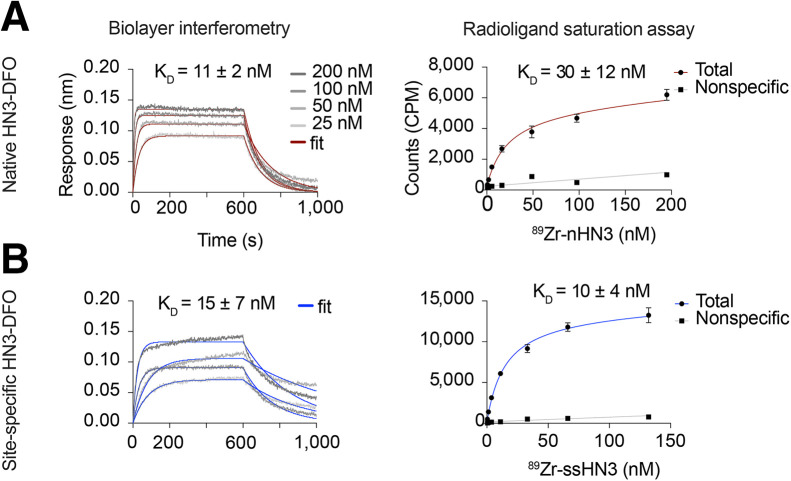

Single-Domain Antibody Conjugates Exhibited Nanomolar Binding Affinities for GPC3

Biolayer interferometry assays showed that affinities (dissociation constant, or KD) for human GPC3 were 11 ± 2 nM and 15 ± 7 nM for nHN3-DFO and ssHN3-DFO, respectively (Fig. 2). Cell-free saturation binding assays showed KD to be 30 ± 12 and 10 ± 4 nM for 89Zr-nHN3 and 89Zr-ssHN3, respectively (P = 0.14) (Fig. 2), indicating that the 2 radioconjugates have comparable binding affinities for GPC3. The somewhat lower binding affinity determined for 89Zr-nHN3 in the saturation assay versus the biolayer interferometry assay may arise from the biolayer interferometry’s detecting unmodified nHN3 in addition to the nHN3-DFO present in the sample. In contrast, the saturation assay detects only nHN3-DFO that has been radiolabeled with 89Zr.

FIGURE 2.

Single-domain antibody conjugates retain GPC3 affinity. Shown are biolayer interferometry (left) and radioligand saturation binding assay (right) results for stochastically modified single-domain antibody nHN3-DFO (A) and ssHN3-DFO (B), with determined KD values. KD values for biolayer interferometry assays are average of measurements using 4 different HN3 concentrations, whereas KD values for saturation assays are average of 3 independent replicates.

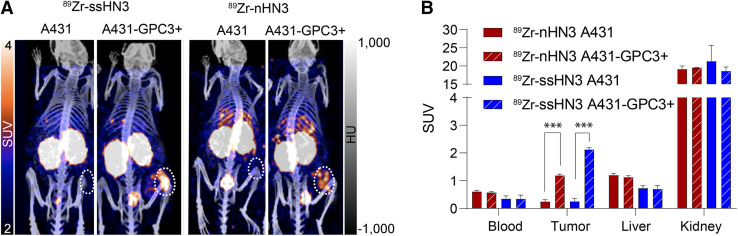

In Vivo Studies Confirmed That Single-Domain Antibody Radioconjugates Specifically Bind to GPC3+ Tumors

After confirming the high affinity of both radioconjugates for GPC3, we evaluated their performance in vivo. Mice bearing subcutaneous xenografts were administered the radioconjugates and underwent PET/CT imaging and ex vivo biodistribution analysis. We first compared the performance of the 2 radioconjugates in mice bearing GPC3-negative (A431) or expressing (A431-GPC3+) tumors. As shown in Figure 3, both conjugates exhibited highly specific tumor accumulation at 1 h after administration, with approximately 10-fold higher tumor uptake in the A431-GPC3+ model than in the otherwise isogenic A431 model. The two 89Zr-single-domain antibody conjugates showed rapid blood clearance and high kidney accumulation as expected. Notably, in ex vivo biodistribution analysis of these mice, 89Zr-ssHN3 exhibited both lower blood and liver accumulation and higher tumor uptake at 3 h (14.4 ± 1.8 %IA/g) than 89Zr-nHN3 (7.4 ± 1.2 %IA/g) in the A431-GPC3+ model (P = 0.0018) (Supplemental Figs. 17 and 18). These results likely stem from the fact that ssHN3 has a preserved GPC3-binding domain whereas the nHN3 conjugate represents a heterogeneous mixture of products, including ones with DFO modifications at lysine residues critical for binding (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the ssHN3 conjugate also lacks the polar -His6 and -FLAG tags present on nHN3, potentially increasing nonspecific uptake of nHN3 (20).

FIGURE 3.

Single-domain antibody PET tracers successfully image tumors engineered to express GPC3. Shown are representative PET/CT images (A) and calculated SUVs (B) of 89Zr-ssHN3 and 89Zr-nHN3 in A431 and A431-GPC3+ tumor–bearing mice (n = 3) 1 h after injection. Full ex vivo biodistribution data for mice bearing A431 and A431-GPC3+ tumors are reported in Supplemental Figures 17 and 18. ***P < 0.005.

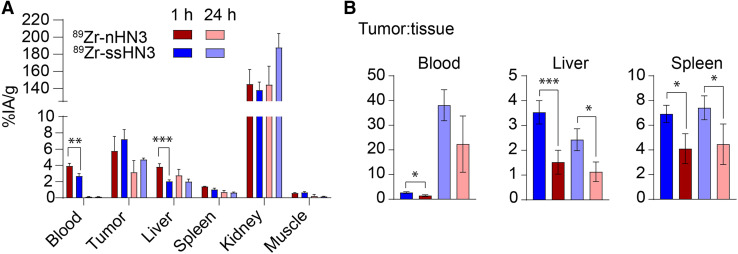

Encouraged by the biodistribution and imaging results in the A431-GPC3+ model, we next investigated the targeting ability of 89Zr-nHN3 and 89Zr-ssHN3 in mice bearing more clinically relevant HepG2 liver cancer xenografts (Fig. 4; Supplemental Figs. 19 and 20), which have lower GPC3 expression than the transfected A431-GPC3+ cell line (32). Generally, biodistribution results for both radiotracers in HepG2 tumor-bearing mice were comparable to those observed in the A431-GPC3+ model. 89Zr-ssHN3 demonstrated numerically higher tumor uptake at 1 h (7.2 ± 1.2 %IA/g) than did 89Zr-nHN3 (5.7 ± 1.8 %IA/g) (P = 0.235), as well as lower accumulation in the blood (P = 0.001), liver (P = 0.008), and spleen (P = 0.013). Kidney uptake of both tracers was quite high (∼140 %IA/g at 1 h after injection). Longitudinal analysis of the radioconjugates’ biodistribution indicates some elimination from both tumor and nontarget organs at 3 and 24 h after administration, but the highest tumor-to-nontarget tissue ratios were obtained at 1 h after injection for both probes (Supplemental Table 1). The tumor-to-liver ratio at 1 h was nearly 3-fold higher for 89Zr-ssHN3 (3.5 ± 0.5) than for 89Zr-nHN3 (1.5 ± 0.5) (P < 0.005), indicating that 89Zr-ssHN3 has superior performance as a liver cancer diagnostic.

FIGURE 4.

Single-domain antibody PET tracers successfully image GPC3+ liver tumor xenografts. Shown are selected ex vivo biodistribution of 89Zr-ssHN3 and 89Zr-nHN3 (A) and tumor-to-tissue ratios of HepG2 tumor-bearing mice (n = 4) (B). Full 12-organ biodistribution results for mice bearing HepG2 tumors are reported in Supplemental Figures 19 and 20. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.005.

Tumor Imaging with 89Zr-ssHN3 Was Superior to That with 89Zr-nHN3 or 18F-FDG in Mice Bearing HepG2 Tumors

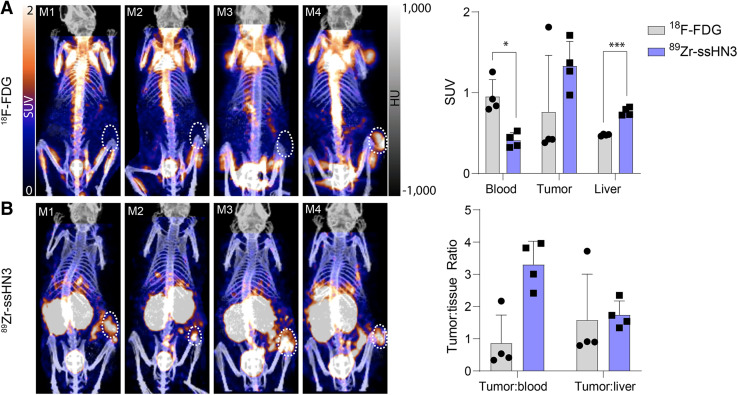

After evaluating the ex vivo biodistribution and PET imaging of 89Zr-ssHN3 and 89Zr-nHN3 in engineered models, we sought to assess their performance for imaging in HepG2 liver cancer xenografts. The 89Zr-ssHN3 tracer displayed both higher tumor accumulation and lower liver uptake than 89Zr-nHN3 (Supplemental Figs. 21–22). 89Zr-ssHN3 also showed positive tumor accumulation (SUV > 1) in all 4 animals, whereas 18F-FDG displayed an SUV of more than 1 in only 1 tumor (Fig. 5; Supplemental Fig. 21). 18F-FDG also exhibited a higher blood pool signal in all animals, indicating 89Zr-ssHN3’s better specificity. However, 18F-FDG did show a lower liver SUV and a much lower kidney signal than 89Zr-ssHN3. Together, our work confirms the potential of the 89Zr-ssHN3 conjugate for GPC3+ tumor detection, having superior imaging performance to either the lysine conjugation-based 89Zr-nHN3 or the clinically available 18F-FDG in models of human liver cancer.

FIGURE 5.

89Zr-ssHN3 PET tracer is superior to 18F-FDG for imaging liver tumors. Shown are PET/CT images of mice (n = 4) bearing HepG2 tumors injected with 18F-FDG (A) and 89Zr-ssHN3 (B). At top is SUV comparison, and at bottom is tumor-to-tissue ratios for both tracers. Error bars represent SD. Full SUV analysis of 89Zr-ssHN3 and 89Zr-nHN3 is reported in Supplemental Figures 21–22. *P < 0.05. ***P < 0.005.

DISCUSSION

Here, we have shown that the GPC3-targeting single-domain antibody HN3 can be engineered as a PET agent for same-day imaging of models of liver cancer. 89Zr-ssHN3 and 89Zr-nHN3 demonstrate high GPC3 affinity in vitro and tumor uptake in GPC3+ tumors in vivo. Notably, 89Zr-ssHN3 demonstrated clear advantages, including higher tumor uptake and lower accumulation in nontarget organs, especially the liver and spleen. The significantly better tumor-to-liver ratio for 89Zr-ssHN3 than for 89Zr-nHN3 (3.5:1 vs. 1.5:1, respectively) would result in a much higher signal-to-noise ratio for PET and thus the ability to better differentiate between cancerous and noncancerous liver lesions. 89Zr-ssHN3 also outperformed 18F-FDG, demonstrating more consistent localization in HepG2 tumor xenografts.

Although its tumor-targeting ability makes 89Zr-ssHN3 attractive for GPC3-directed PET, its high kidney uptake impedes single-domain antibody–based radiopharmaceutical therapy, and the long half-life of 89Zr leads to an unnecessarily high deposition of radioactivity in the kidneys. Strategies to reduce kidney uptake of single-domain antibodies include coadministration of lysine or Gelofusine (B. Braun Melsungen), alteration of the single-domain antibody sequence, or addition of an albumin-binding moiety (20,33,34). Efforts to decrease the kidney uptake of HN3 conjugates and prepare short-lived 68Ga or 18F conjugable derivatives are currently under way in our lab.

The GPC3-specific imaging capabilities of 89Zr-ssHN3 place it among a select few radiotracers with clinical potential for liver tumor PET imaging. Although GPC3-targeted antibody conjugates have demonstrated specific tumor accumulation, these agents suffer from slow tumor uptake kinetics and are generally unsuitable for same-day imaging (11–13). Single-domain antibodies represent an alternative targeting biomolecule with excellent specificity and rapid clearance. An et al. were the first to demonstrate the feasibility of using a GPC3-targeting single-domain antibody (G2) for immuno-PET (17). The authors reported relatively low tumor uptake (2.6 %IA/g) and tumor-to-liver ratios (1.67 ± 0.09) in animals bearing GPC3+ Hep3B liver cancer xenografts, likely resulting from the use of conventional lysine-based conjugation. Our work confirms that sortase-based site-specific modification of a GPC3-targeting single-domain antibody is superior to conventional lysine-based modification for immuno-PET of liver tumors.

The development of a tumor-specific imaging agent for HCC is critically needed to improve diagnosis, monitor treatment efficacy, and inform management. Local therapies such as stereotactic body radiation therapy, radiofrequency or microwave ablation, and transarterial embolization have proven effective against local disease (1). The efficacy of radiation-based treatments highlights the sensitivity of liver tumors to radiotherapy (1,35). Notable in leveraging this HCC radiosensitivity is 131I-metuximab, a F(ab′)2 specific to basigin or CD147 that is expressed on 60% of HCCs. This radioconjugate was approved as adjuvant therapy in China after demonstrating a survival benefit compared with observation after surgical resection in a randomized controlled phase 2 trial (36). These results are buoyed by clinical data showing noninferiority of proton stereotactic body radiation therapy compared with radiofrequency ablation in patients with small recurrent or residual HCC in a randomized phase 3 trial (35), survival benefit using adjuvant external-beam radiotherapy in a phase 2 trial (37), and promising results in the neoadjuvant setting as well (38). However, assessing the response of tumors to these liver-directed therapies is difficult because existing imaging modalities cannot differentiate viable from nonviable tumors. Our novel GPC3-selective immuno-PET probe might be used under these circumstances to help clinical decision making and improve patient outcomes.

In addition, tumor-selective imaging of GPC3 might serve as a noninvasive predictive biomarker to identify patients who may preferentially respond to GPC3-directed therapy, including chimeric antigen receptor T-cell strategies (NCT05003895). Tumor-selective targeting of GPC3 might also be extended toward the development of a therapeutic radiopharmaceutical. HN3-based PET agents may be particularly suitable for this application, given that therapies based on chimeric antigen receptor T cells and immunotoxins using the HN3 single-domain antibody have already shown preclinical success (39,40).

CONCLUSION

We successfully designed, synthesized, and characterized novel GPC3-selective single-domain antibody PET probes for imaging liver tumors, and these probes showed superiority to conventional imaging with 18F-FDG. Comparative analysis of 89Zr-nHN3 and 89Zr-ssHN3 showed that 89Zr-ssHN3 has superior in vivo target engagement and pharmacokinetic properties in GPC3+ liver cancer xenograft models. We confirmed that the sortase-mediated conjugation successfully preserves the affinity of the single-domain antibody, an approach that can be extended to other radioconjugates with a lower molecular weight. Efforts are ongoing toward developing second-generation ssHN3 conjugates that have short-lived radionuclides for imaging and improved kidney uptake for therapy.

DISCLOSURE

This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute from Intramural Research Program funds ZIA BC 011800 and ZIA BC 010891. Dr. Mitchell Ho holds the patent (WO2012145469) assigned to the National Institutes of Health for the HN3 single-domain antibody specific for GPC3. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

KEY POINTS

QUESTION: Can we engineer a GPC3-specific single-domain antibody for tumor-selective PET imaging of liver cancer?

PERTINENT FINDINGS: We used a GPC3-specific single-domain antibody to engineer 89Zr-nHN3 and 89Zr-ssHN3 immuno-PET probes and confirmed specific GPC3 binding in vitro and in vivo. Our 89Zr-ssHN3 immuno-PET tracer outperformed a lysine-conjugated probe and 18F-FDG for PET imaging of liver cancer xenografts.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PATIENT CARE: 89Zr-ssHN3 represents a promising same-day immuno-PET agent for diagnosis and posttreatment surveillance of liver cancer.

REFERENCES

- 1. Vogel A, Meyer T, Sapisochin G, Salem R, Saborowski A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2022;400:1345–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rumgay H, Arnold M, Ferlay J, et al. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J Hepatol. 2022;77:1598–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rumgay H, Ferlay J, de Martel C, et al. Global, regional and national burden of primary liver cancer by subtype. Eur J Cancer. 2022;161:108–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Estes C, Razavi H, Loomba R, Younossi Z, Sanyal AJ. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology. 2018;67:123–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Choi J-Y, Lee J-M, Sirlin CB. CT and MR imaging diagnosis and staging of hepatocellular carcinoma: part I. Development, growth, and spread: key pathologic and imaging aspects. Radiology. 2014;272:635–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lu R-C, She B, Gao W-T, et al. Positron-emission tomography for hepatocellular carcinoma: current status and future prospects. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:4682–4695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marcu L, Bezak E, Allen BJ. Global comparison of targeted alpha vs targeted beta therapy for cancer: in vitro, in vivo and clinical trials. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;123:7–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Strosberg J, El-Haddad G, Wolin E, et al. Phase 3 trial of 177Lu-Dotatate for midgut neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:125–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sartor O, de Bono J, Chi KN, et al. Lutetium-177–PSMA-617 for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1091–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang HL, Anatelli F, Zhai Q, Adley B, Chuang S-T, Yang XJ. Glypican-3 as a useful diagnostic marker that distinguishes hepatocellular carcinoma from benign hepatocellular mass lesions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1723–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sham JG, Kievit FM, Grierson JR, et al. Glypican-3–targeted 89Zr PET imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:799–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kelada OJ, Gutsche NT, Bell M, et al. ImmunoPET as stoichiometric sensor for glypican-3 in models of hepatocellular carcinoma. bioRxiv website. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.01.31.926972v1.full. Published February 2, 2020. Accessed March 21, 2023.

- 13. Carrasquillo JA, O’Donoghue JA, Beylergil V, et al. I-124 codrituzumab imaging and biodistribution in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. EJNMMI Res. 2018;8:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sham JG, Kievit FM, Grierson JR, et al. Glypican-3–targeting F(ab′)2 for 89Zr PET of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:2032–2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hamers-Casterman C, Atarhouch T, Muyldermans S, et al. Naturally occurring antibodies devoid of light chains. Nature. 1993;363:446–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Greenberg AS, Avila D, Hughes M, Hughes A, McKinney EC, Flajnik MF. A new antigen receptor gene family that undergoes rearrangement and extensive somatic diversification in sharks. Nature. 1995;374:168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. An S, Zhang D, Zhang Y, et al. GPC3-targeted immunoPET imaging of hepatocellular carcinomas. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022;49:2682–2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Massa S, Xavier C, De Vos J, et al. Site-specific labeling of cysteine-tagged camelid single-domain antibody-fragments for use in molecular imaging. Bioconjug Chem. 2014;25:979–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chatalic KLS, Veldhoven-Zweistra J, Bolkestein M, et al. A novel 111In-labeled anti–prostate-specific membrane antigen nanobody for targeted SPECT/CT imaging of prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1094–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. D’Huyvetter M, Vincke C, Xavier C, et al. Targeted radionuclide therapy with a 177Lu-labeled anti-HER2 nanobody. Theranostics. 2014;4:708–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Feng M, Gao W, Wang R, et al. Therapeutically targeting glypican-3 via a conformation-specific single-domain antibody in hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E1083–E1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mao H, Hart SA, Schink A, Pollok BA. Sortase-mediated protein ligation: a new method for protein engineering. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:2670–2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Massa S, Vikani N, Betti C, et al. Sortase A-mediated site-specific labeling of camelid single-domain antibody-fragments: a versatile strategy for multiple molecular imaging modalities. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2016;11:328–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rashidian M, Keliher EJ, Bilate AM, et al. Noninvasive imaging of immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:6146–6151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Truttmann MC, Wu Q, Stiegeler S, Duarte JN, Ingram J, Ploegh HL. HypE-specific nanobodies as tools to modulate HypE-mediated target AMPylation. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:9087–9100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Feng M, Bian H, Wu X, et al. Construction and next-generation sequencing analysis of a large phage-displayed VNAR single-domain antibody library from six naïve nurse sharks. Antib Ther. 2019;2:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Duan Z, Buffington J, Hong J, Ho M. Production and purification of shark and camel single-domain antibodies from bacterial and mammalian cell expression systems. Curr Protoc. 2022;2:e459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guimaraes CP, Witte MD, Theile CS, et al. Site-specific C-terminal and internal loop labeling of proteins using sortase-mediated reactions. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1787–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vosjan MJWD, Perk LR, Visser GWM, et al. Conjugation and radiolabeling of monoclonal antibodies with zirconium-89 for PET imaging using the bifunctional chelate p-isothiocyanatobenzyl-desferrioxamine. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:739–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Phung Y, Gao W, Man Y-G, Nagata S, Ho M. High-affinity monoclonal antibodies to cell surface tumor antigen glypican-3 generated through a combination of peptide immunization and flow cytometry screening. MAbs. 2012;4:592–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Berman RM, Kelada OJ, Gutsche NT, et al. In vitro performance of published glypican 3-targeting peptides TJ12P1 and L5 indicates lack of specificity and potency. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2019;34:498–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fu Y, Urban DJ, Nani RR, et al. Glypican-3 specific antibody drug conjugates targeting hepatocellular carcinoma (HEP-10-1020). Hepatology. 2019;70:563–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tijink BM, Laeremans T, Budde M, et al. Improved tumor targeting of anti–epidermal growth factor receptor Nanobodies through albumin binding: taking advantage of modular Nanobody technology. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2288–2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gainkam LO, Caveliers V, Devoogdt N, et al. Localization, mechanism and reduction of renal retention of technetium-99m labeled epidermal growth factor receptor-specific nanobody in mice. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2011;6:85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim TH, Koh YH, Kim BH, et al. Proton beam radiotherapy vs. radiofrequency ablation for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized phase III trial. J Hepatol. 2021;74:603–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li J, Xing J, Yang Y, et al. Adjuvant 131I-metuximab for hepatocellular carcinoma after liver resection: a randomised, controlled, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:548–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen B, Wu J-X, Cheng S-H, et al. Phase 2 study of adjuvant radiotherapy following narrow-margin hepatectomy in patients with HCC. Hepatology. 2021;74:2595–2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wu F, Chen B, Dong D, et al. Phase 2 evaluation of neoadjuvant intensity-modulated radiotherapy in centrally located hepatocellular carcinoma: a nonrandomized controlled trial. JAMA Surg. 2022;157:1089–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fleming BD, Urban DJ, Hall MD, et al. Engineered anti-GPC3 immunotoxin, HN3-ABD-T20, produces regression in mouse liver cancer xenografts through prolonged serum retention. Hepatology. 2020;71:1696–1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kolluri A, Li D, Li N, Ho M. Engineered, fully human nanobody-based CAR T cells have enhanced antitumor activity against hepatocellular carcinoma in preclinical models [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(suppl):e14512–e14512. [Google Scholar]