Abstract

Initiation of chromosomal replication requires dynamic nucleoprotein complexes. In most eubacteria, the origin oriC contains multiple DnaA box sequences to which the ubiquitous DnaA initiators bind. In Escherichia coli oriC, DnaA boxes sustain construction of higher-order complexes via DnaA–DnaA interactions, promoting the unwinding of the DNA unwinding element (DUE) within oriC and concomitantly binding the single-stranded (ss) DUE to install replication machinery. Despite the significant sequence homologies among DnaA proteins, oriC sequences are highly diverse. The present study investigated the design of oriC (tma-oriC) from Thermotoga maritima, an evolutionarily ancient eubacterium. The minimal tma-oriC sequence includes a DUE and a flanking region containing five DnaA boxes recognized by the cognate DnaA (tmaDnaA). This DUE was comprised of two distinct functional modules, an unwinding module and a tmaDnaA-binding module. Three direct repeats of the trinucleotide TAG within DUE were essential for both unwinding and ssDUE binding by tmaDnaA complexes constructed on the DnaA boxes. Its surrounding AT-rich sequences stimulated only duplex unwinding. Moreover, head-to-tail oligomers of ATP-bound tmaDnaA were constructed within tma-oriC, irrespective of the directions of the DnaA boxes. This binding mode was considered to be induced by flexible swiveling of DnaA domains III and IV, which were responsible for DnaA–DnaA interactions and DnaA box binding, respectively. Phasing of specific tmaDnaA boxes in tma-oriC was also responsible for unwinding. These findings indicate that a ssDUE recruitment mechanism was responsible for unwinding and would enhance understanding of the fundamental molecular nature of the origin sequences present in evolutionarily divergent bacteria.

Keywords: AAA+, DnaA, DNA replication, DNA–protein interaction, DNA unwinding, oriC, protein–protein interaction

Unwinding of duplex DNA is fundamental for chromosomal DNA replication in all cellular organisms. The origin of replication oriC encodes instructions to form a highly ordered nucleoprotein complex called the initiation complex. In bacteria, this complex is mainly comprised of the ubiquitous family of DnaA initiator proteins (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). The minimal oriC in Escherichia coli consists of an AT-rich DNA unwinding element (DUE) and a flanking DnaA oligomerization region (DOR) containing a cluster of DnaA-binding sequences (DnaA boxes) (Fig. 1A). The ATP-bound DnaA oligomers of the DOR are important for DUE unwinding and loading of DnaB replicative helicase onto the unwound region (5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11).

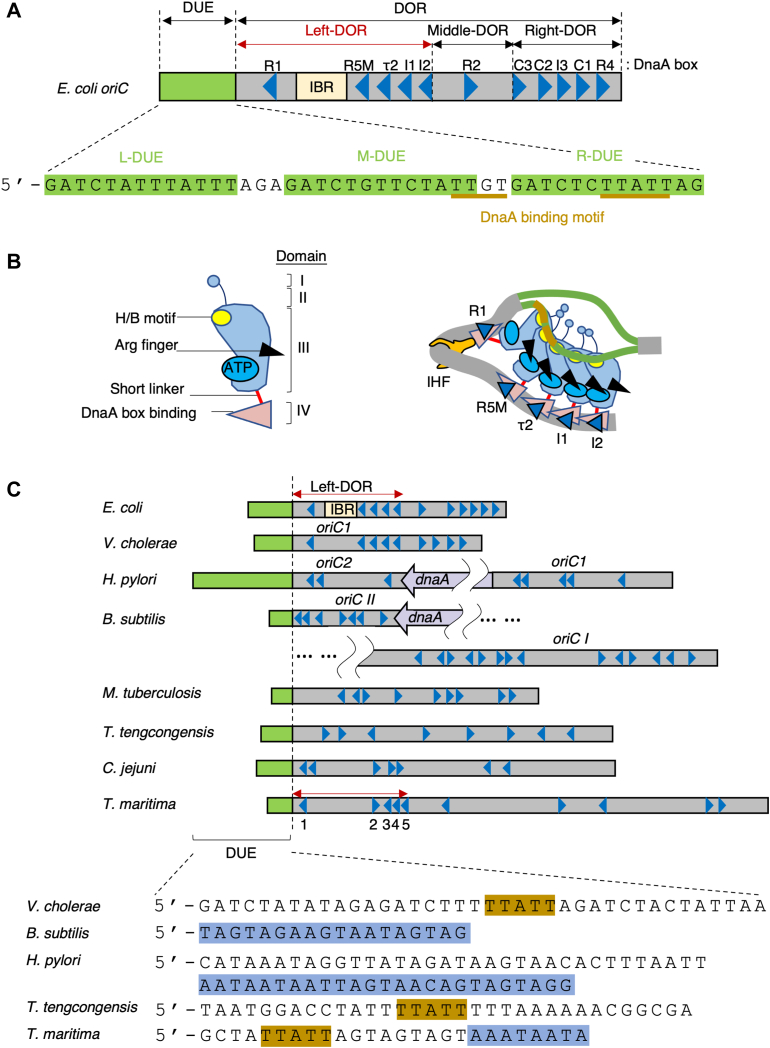

Figure 1.

Models for unwinding of the replication origin in eubacteria. A, the structure of E. coli oriC. DnaA boxes (R1, R5M, τ2, I1, I2, C3, C2, I3, C1, and R4) are indicated by arrowheads and the IHF-binding region (IBR) by a rectangle. DnaA box τ1, which overlaps IBR, is omitted for simplicity. DUE comprises L-, M-, and R-DUE (colored in green). The DnaA-binding motifs, TTGT and TTATT, are highlighted in brown bars. Left DOR spans DnaA boxes R1–I2, middle DOR consists of DnaA box R2, and right DOR spans DnaA boxes C3–R4. B, a model for open complex formation through the ssDUE recruitment mechanism. Schematic illustration of the domain architecture (I-IV) of a typical protein of the DnaA family. Domains III and IV are connected by a short linker in E. coli. The H/B and Arg-finger motifs are also indicated. In E. coli, the ATP-DnaA pentamer formed on IHF-bound left DOR unwinds DUE and concomitantly binds the upper strand of the ssDUE in a manner specific to the sequence TT[G/A]T(T). C, comparison of the overall structures of the replication origins of Eubacteria. DORs of the indicated eubacterial organisms are aligned. The bilobed structure of the origins of Bacillus subtilis and Heliobacter pylori are depicted, with one lobe, oriC II for B. subtilis and oriC2 for H. pylori, bearing the DUE. The overall structures of the origins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (29), Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis (30), and Camplyobacter jejuni (31) are also shown. DUE is indicated by green bars, and the sequences of experimentally characterized DUEs from B. subtilis H. pylori, T. tengcongensis, and Thermotoga maritima are shown below, highlighting the TTATT motif in brown and DnaA-trios in blue. DnaA boxes and IBR are shown as in panel A. E. coli Left-DOR and minimal tmaDOR are indicated by red left-right arrows. DOR, DnaA oligomerization region; DUE, duplex unwinding element; IHF, integration host factor; ss, single-stranded; tma, Thermotoga maritima.

Proteins in the DnaA family contain a central domain III with AAA+ (ATPases associated with various cellular activities) motifs (2, 4, 5, 12) (Fig. 1B). These motifs play essential roles in ATP/ADP binding, ATP hydrolysis, and DnaA–DnaA interactions (10, 12, 13). Similar to other proteins containing AAA+ motifs, head-to-tail oligomerization via this domain underlies the formation of an initiation complex by ATP–DnaA. In E. coli DnaA, the AAA+ arginine-finger motif Arg285 predominantly recognizes ATP bound to the adjacent DnaA protomer, promoting co-operative ATP-DnaA binding onto the DOR in a head-to-tail orientation (14, 15, 16) (Fig. 1B). Moreover, H/B-motifs (hydrophobic Val211 and basic Arg245) in this domain bind single-stranded DUEs (ssDUEs) in a sequence-specific manner (9, 17) (Fig. 1, A and B). The AAA+ domain III of DnaA is linked via a flexible hinge to its C-terminal domain IV, which is responsible for DnaA box-specific DNA binding (18)(Fig. 1B). The N-terminal domain I has multiple sites for interactions with DnaB helicase etc. and for weak domain I–domain I interactions (11, 14, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23). Domain II is a flexible linker between domains I and III (21, 24) (Fig. 1B).

The arrangement of DnaA boxes within the DOR provides an essential scaffold for formation of the initiation complex (Fig. 1, A and C). A canonical DnaA box consists of an asymmetric 9-mer consensus sequence, TTA[T/A]NCACA (3, 25). The DOR in E. coli contains no fewer than 12 DnaA boxes as well as a region for specific binding to integration host factor (IHF), a nucleoid-associated protein that introduces a sharp bend in DNA (IHF-binding region) (Fig. 1, A and B) (1, 2). Five of these DnaA boxes in the left DOR (R1, R5M, τ2, and I1-2) share the same orientation, whereas five boxes in the right DOR (R4, C1-3, and I3) share the opposite orientation (8, 14, 15, 26, 27, 28). The directional arrangement of the DnaA boxes facilitates head-to-tail oligomerization of ATP–DnaA proteins depending on the ATP–Arg finger interaction. This leads to formation of a pair of pentamers bound to the left and right DORs, with the two facing each other. In the left DOR, the IHF-dependent bending facilitates formation of the DnaA complexes, promoting DUE unwinding activity (26) (Fig. 1B). DnaA complexes in the right DOR are important for enhancement of the unwound state and efficient DnaB loading (7, 9).

Experimental determination of the oriCs of representative bacterial species has shown that the basic structure of Vibrio cholerae oriC1, the origin of chromosome I, is most similar to that of E. coli oriC, in that the DUE is flanked by a region containing two DnaA box clusters in the opposite directions (3) (Fig. 1C). The oriC of Heliobacter pylori is split into two subsequences, oriC1 and oriC2, by insertion of the dnaA gene; the oriC2 of H. pylori may correspond to the region of the E. coli oriC spanning DUE to the left DOR, a region containing a single cluster of unidirectional DnaA boxes (3) (Fig. 1C). However, the oriC sequences from other species vary in the directions of DnaA boxes, despite containing direct repeats of DnaA box sequences (29, 30, 31). Similar features have also been observed in the bioinformatically predicted oriCs of bacterial genomes (32) (Fig. S1). Thus, the principles underlying the designs of DnaA box arrangements within bacterial DORs that underlie the construction of DnaA oligomers remain unclear.

In E. coli, the ATP-DnaA–IHF–Left-DOR complexes are responsible for the unwinding of DUE. The upper strand of the resulting ssDUE is subsequently recruited to the ATP–DnaA pentamers through IHF binding-induced DOR bending, which directs interactions between the H/B-motifs of DnaA and ssDUE, resulting in open complex formation (7, 9, 17, 26) (Fig. 1, A and B). This ssDUE recruitment mechanism stabilizes the unwound state of DUE within the open complex, allowing efficient DnaB replicative helicase loading onto the ssDUE region. In-depth analyses have shown that the TTGT/TTATT motifs within DUE bind the DnaA–DOR complex and are crucial for the initiation of replication (17, 33) (Fig. 1, B and C), emphasizing the physiological importance of DnaA–ssDUE interactions.

Functional DnaA–ssDUE interactions have also been implicated in other bacterial species, including Bacillus subtilis and H. pylori (34, 35). Both origins display a bilobed structure, with oriC1 and oriC2 being separated by insertion of a dnaA gene. B. subtilis oriC2 carries the cognate DOR with seven DnaA boxes, followed by a GC-rich 5-mer and a flanking DUE region that includes 5′-TAG-TAG-AAG-TAA-TAG-TAG-3′ sequences (Fig. 1C). Of these sequences, the two adenine residues at positions 14 and 17 are crucial for in vivo initiation and repeats of the trinucleotide termed DnaA-trios, 5′-TAG-3′, 5′-TAA-3′, and 5′-AAG-3′, are contained (34, 36). Chemical cross-linking has indicated that the B. subtilis DnaA-trios on ssDUE promote the oligomerization of cognate ATP-DnaA, depending on the DnaA bound to the duplex DNA DnaA boxes flanking the DUE, thereby supporting DUE unwinding in vitro (34, 36). By contrast, in H. pylori oriC2 carrying the DUE with the cognate DnaA-trios (5′-AAT-AAT-AAT-TAG-TAA-CAG-TAG-TAG-3′), the cognate DnaA–DOR complexes bind the ssDUE (35) (Fig. 1C). Similar mechanisms involving ssDUE interactions of the initiator protein have been observed for the V. cholerae chromosome 2 origin (oriC2) and its cognate initiator RctB, although RctB is not an AAA+ protein (37). oriC2 carries the cognate DUE and the flanking regions with multiple RctB-binding sequences. RctB oligomers within oriC2 interact with ATCA repeats of ssDUE in a manner stimulated by IHF binding and DNA looping between the two RctB-interacting regions. These mechanisms in H. pylori and V. cholerae were principally similar to the ssDUE recruitment mechanism in E. coli (Fig. 1B).

The ssDUE recruitment mechanism has also been observed at the origin of replication of the bacterium Thermotoga maritima (tma-oriC). Phylogenetic and biological analyses have placed this organism at a deep branch in the tree of life (38, 39), with its DnaA initiator (tmaDnaA) recognizing the noncanonical DnaA box with an asymmetric sequence (tmaDnaA box) repeated 10 times within tma-oriC (Figs. 1C and S2). The 149 bp minimal tma-oriC, which is responsible for specific unwinding, contains a 24 bp AT-rich tmaDUE and a flanking tmaDOR consisting of tmaDnaA boxes 1 to 5 (40) (Fig. 2A). Although tmaDnaA box 2 is oriented in the opposite direction, the tmaDOR is associated with the formation of ATP-tmaDnaA oligomers responsible for DUE unwinding. Moreover, the upper strand of tma-ssDUE binds to ATP-tmaDnaA oligomers bound to tmaDOR, depending on the tmaDnaA residues Val176 and Lys209, which correspond to the H/B-motifs (17). These observations are in good agreement with the ssDUE recruitment mechanism. Notably, tmaDnaA boxes 3 to 5 play a crucial role in formation of ATP-tmaDnaA oligomers responsible for ssDUE binding (9). However, the contribution of the oppositely oriented tmaDnaA box 2 to the formation of the initiation complex remains unclear, as do the tmaDUE sequences responsible for DUE unwinding and ssDUE binding.

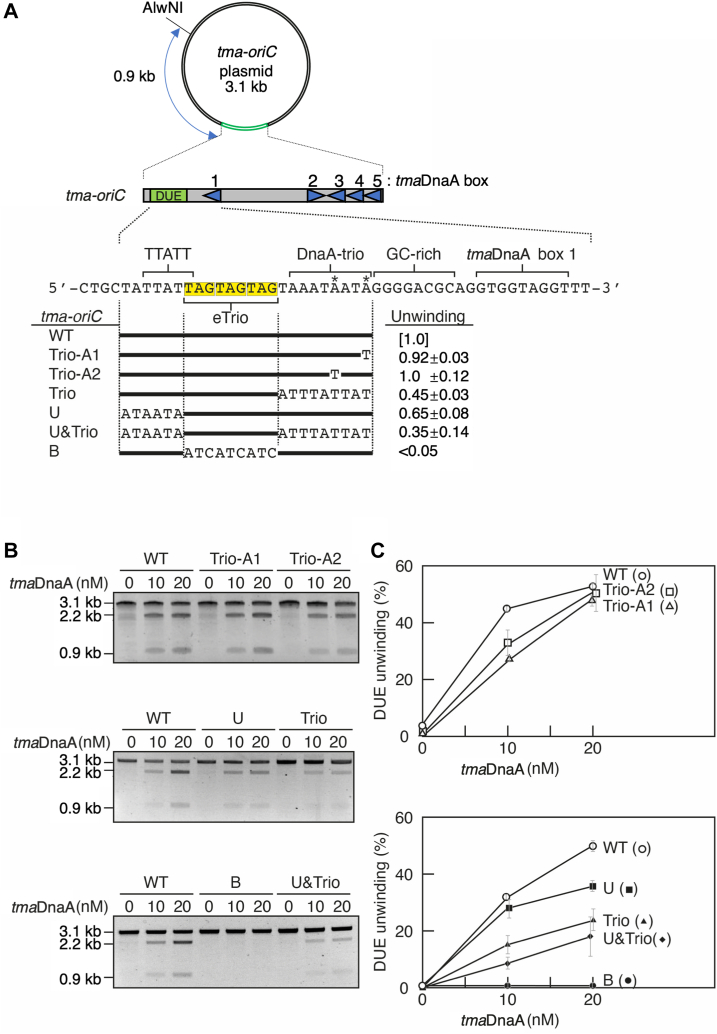

Figure 2.

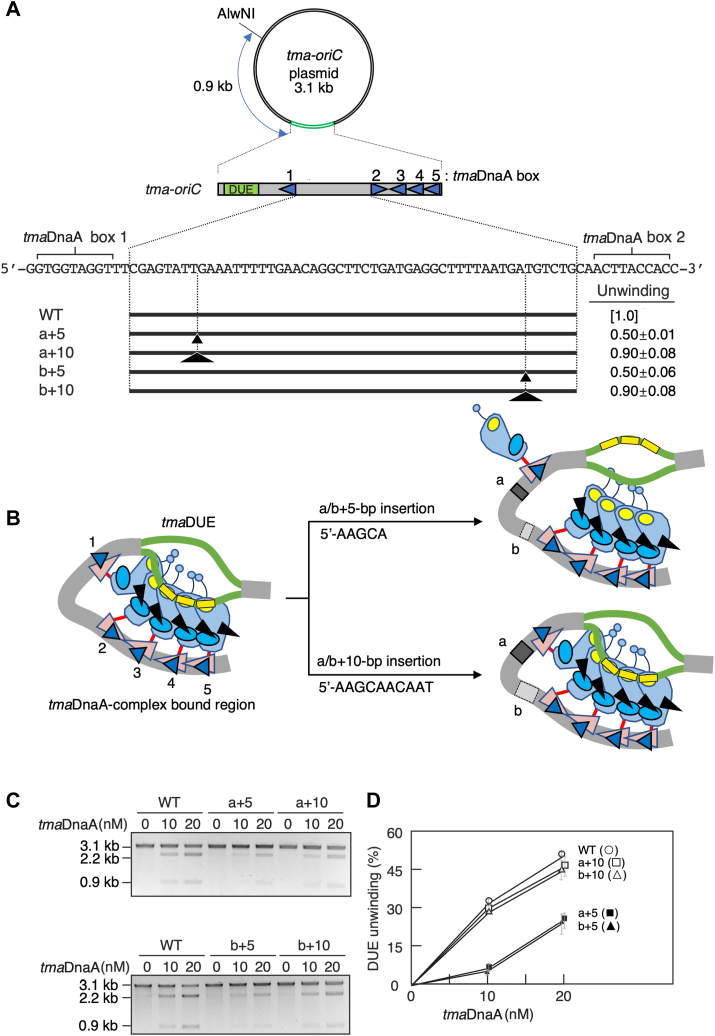

The three tandem TAG repeats are essential for DUE unwinding. A, the structure of tma-oriC plasmids. pOZ14 is a pBluescript derivative with a 149 bp minimal tma-oriC DNA (WT). tma-oriC is indicated by a gray bar, tmaDUE by an green box (DUE), and tmaDnaA boxes 1 to 5 by blue triangles (box 1–5). Sequences of the TTATT, eTrio, DnaA-trio, GC-rich, and tmaDnaA box 1 motifs are shown below the tma-oriC, as are derivatives of the tmaDUE region. For mutant tma-oriC plasmids, intact DUE regions are indicated by bold lines and base substitutions by letters. The percentages of the open complex at 20 nM tmaDnaA (unwinding) are shown relative to that of the wildtype (WT). B and C, open complex formation. WT and mutant tma-oriC plasmids were individually incubated with the indicated concentrations of ATP-tmaDnaA, followed by P1 nuclease digestion. After purification, DNA samples were further digested with AlwNI and analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. (B) Gel images. (C) Mean ± standard deviation percentages of P1 nuclease-digested DNA (n = 2) quantified by FIJI software. DUE, duplex unwinding element.

The present study provides evidence showing that the T. maritima DUE consists of at least two functional modules, an unwinding module and a DnaA-binding module, and that ATP-tmaDnaA head-to-tail oligomers can be constructed on a tmaDnaA box-cluster with an inverted box. The tmaDUE contained an E. coli-type TTATT motif and previously annotated DnaA-trios (5′-AAA-TAA-TA-3′) flanking tmaDnaA box 1 (34) (Fig. 1C), with both stimulating unwinding without binding to tmaDnaA–tmaDOR complexes. By contrast, binding was strictly dependent on three direct repeats of the trinucleotide TAG located between the two elements. The present study also determined the optimal arrangement of the tmaDnaA boxes, including their orientation and spacing. Notably, formation of head-to-tail oligomers of tmaDnaA did not always require DnaA box clusters in the same direction. These findings provide insight into the DnaA oligomer-binding mechanisms in oriCs of many species that vary in the directions of DnaA boxes.

Results

Identification of a novel motif within tma-oriC required for DUE unwinding

To gain insights into prototypic structures of the origin, the origin sequences of the deep-branching hyperthermophilic bacterium, T. maritima, were analyzed. The 149 bp minimal tma-oriC in the T. maritima chromosome consisted of an AT-rich tmaDUE and a flanking tmaDOR containing the five tmaDnaA boxes 1 to 5 recognized by tmaDnaA (Fig. 2A). The 12-mer sequence motifs have been named tmaDnaA boxes (40, 41). Based on further sequence analysis indicating that the terminal three bases of each motif are only moderately conserved (Fig. S2B) and previous data indicating that all tmaDnaA boxes had similar affinity, irrespective of the variations in these three bases (40), the consensus sequence was redefined as the most conserved 9-mer, 5′-ACCTACCAC-3′, preserving its asymmetry. Moreover, the right part of tmaDOR carrying tmaDnaA boxes 3 to 5 was found to permit formation of distinct ATP-tmaDnaA oligomers able to bind ss-tmaDUE, most likely through the ssDUE recruitment mechanism (9). Examination of the tmaDUE sequences suggested the importance of two ssDUE-binding motifs: TTATT from E. coli and the DnaA-trio from B. subtilis (Fig. 2A). Although each of these motifs has been implicated in initiation of replication of its respective organism, their functional importance in evolutionarily distant bacteria, such as T. maritima, was undetermined.

The DnaA-trios (5′-AAA-TAA-TA-3′) are previously annotated within tmaDUE at the site proximal to tmaDOR (34) (Fig. 2A). Importance of this sequence for open complex formation was assessed by P1 nuclease assays using tmaDnaA, the E. coli DNA-binding protein HU, and a 3.1 kb supercoiled plasmid DNA containing the tma-oriC (Fig. 2A). HU protein is the evolutionarily highly conserved IHF homolog in eubacterial species and can sustain DUE unwinding of E. coli oriC instead of IHF which is conserved only in proteobacteria, nitrospirae, and nitrospinae (42, 43, 44, 45, 46). As we previously demonstrated (40), ATP-bound, but not ADP-bound, tmaDnaA promotes open complex formation of tma-oriC at 48 °C in the presence of E. coli HU. In this assay, unwound tmaDUE is detected by the endonuclease P1 promoting cleavage of the single-stranded DNA. Further digestion with the restriction enzyme AlwNI yields 2.2 and 0.9 kb DNA fragments (Fig. 2, A–C).

First, tmaDUE unwinding was assessed using tma-oriC bearing mutations in the annotated DnaA-Trios (Fig. 2, B and C). Because a base substitution at either the first or third position from the 3′ end of the DnaA-trio sequence motif (5′-TAG-TAG-AAG-TAA-TAG-TA-3′, with the corresponding residues underlined), but not at the surrounding positions, was found to lead to severe initiation defects in B. subtilis (35), mutant tma-oriC plasmids bearing an A-to-T substitution at the corresponding positions (5′-AAA-TAA-TA-3′) were analyzed. The unwinding activities of these mutant plasmids were comparable to the activities of wildtype (WT) tma-oriC plasmid (Trio-A1 and Trio-A2 in Fig. 2, B and C). Moreover, moderate unwinding activities remained even when the entire DnaA-trio was scrambled (Trio in Fig. 2, B and C). Taken together, these results suggested that the previously annotated DnaA-trio plays a supportive, but not essential, role in open complex formation.

To further analyze the sequences essential for tmaDUE unwinding, the TTATT motif was examined similarly (Fig. 2A). Scrambling of this sequence slightly inhibited tmaDUE unwinding (U in Fig. 2, B and C). Moreover, when the TTATT and DnaA-trio sequences were simultaneously scrambled, the inhibition levels were additive, but slight unwinding activity remained (U&Trio in Fig. 2, B and C). These observations suggested that both the TTATT motif and the DnaA-trio are required for full tmaDUE unwinding activity.

Analyses of the sequences located between the TTATT motif and the DnaA-trio showed three tandem repeats of TAG. Strikingly, scrambling of these sequences completely abolished the tmaDUE unwinding activity (B in Fig. 2, B and C), indicating that these sequences were essential for open complex formation. Based on their homology to DnaA-trios, the three tandem TAG repeats have been named the extended Trio (eTrio).

ATP-tmaDnaA oligomers on DOR bind ssDUE through eTrio

To further dissect the roles of sequence motifs within DUE, interactions between ss-tmaDUE and ATP-tmaDnaA oligomers constructed on tmaDOR were analyzed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). In these assays, a radiolabeled, 28-mer ss-tmaDUE probe was coincubated with ATP-tmaDnaA and tmaDOR, followed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3A). As we previously reported (9), ATP-tmaDnaA oligomers constructed on tmaDOR (ATP–tmaDnaA–tmaDOR complexes) specifically interact with the ligand TMA28, an upper strand fragment of ss-tmaDUE (Figs. 3A and S3). These interactions depend on tmaDOR and ATP-bound, but not ADP-bound, tmaDnaA (Fig. S3), as previously reported (9). DnaA proteins are apt to form irregular aggregates in the absence of DNA binding, remaining in the gel well. Moreover, a right part of tmaDOR, including tmaDnaA boxes 3 to 5, is sufficient to construct ATP–tmaDnaA complexes capable of interacting with ss-tmaDUE (9).

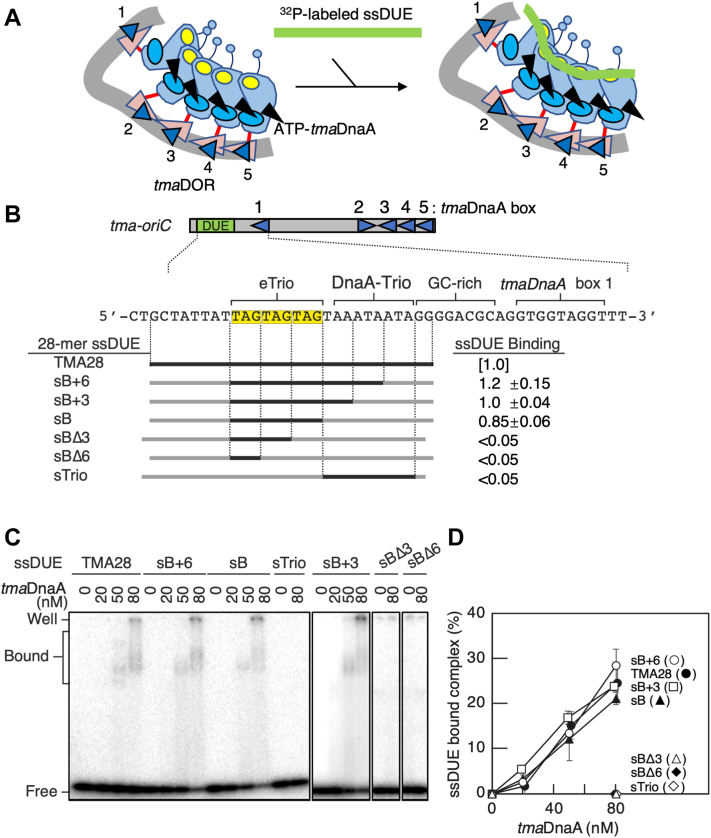

Figure 3.

The three tandem TAG repeats are essential for ssDUE binding. A, schematic of the ssDUE-binding assay. ATP–tmaDnaA–tmaDOR complexes were constructed and incubated with 32P-labeled ssDUE, followed by EMSA. See the other data in this paper for overall structure of ATP–tmaDnaA–tmaDOR complexes. B–D, wildtype ssDUE fragment (TMA28) or its derivatives with oligo-dC-substitution (2.5 nM) were incubated with tmaDOR (30 nM) and the indicated amount of ATP-tmaDnaA, followed by EMSA. Minimal tma-oriC is shown as in Figure 2A. The ssDUE sequences used in this assay are illustrated schematically in panel B, with intact and oligo-dC-substituted sequences shown in bold and gray lines, respectively. C, representative gel images. D, quantitation of the results in (C) (n = 2) relative to the input ssDUE. Binding activities (ssDUE binding) at 80 nM tmaDnaA are shown in panel B relative to that of TMA28. DOR, DnaA oligomerization region; EMSA, electrophoretic mobility shift assay; ssDUE, single-stranded duplex unwinding element; tma, Thermotoga maritima.

EMSAs using a set of ss-tmaDUE variants with oligo-dC substitutions were performed to determine the minimal sequence required by the upper strand of ss-tmaDUE to bind ATP–tmaDnaA–tmaDOR complexes. Because eTrio was found essential for DUE unwinding, its ability to bind ATP–tmaDnaA–tmaDOR complexes was analyzed, with results showing that the ss-tmaDUE variant bearing the eTrio and oligo-dC regions (sB) displayed binding activity comparable to WT TMA28 or variants bearing eTrio and a partial DnaA-trio (sB+6 and sB+3) (Fig. 3, B–D). Moreover, all three TAG trinucleotides within eTrio were required for binding as reducing the number of TAG trinucleotides to two (sBΔ3) or one (sBΔ6) completely abolished the binding activity. Similarly, the ss-tmaDUE variant bearing only the DnaA-trio and oligo-dC regions (sTrio) was inactive (Fig. 3, B–D), indicating that ss-tmaDUE binding strongly depends on the three TAG repeats within eTrio. Taken together with the results showing that eTrio is strictly required for DUE unwinding (Fig. 2), these findings indicate that direct interactions between ss-eTrio and ATP–tmaDnaA–tmaDOR complexes are important in stabilizing open complexes. Because the DnaA-trio within tmaDUE is dispensable for binding to ATP–tmaDnaA–tmaDOR complexes but plays only a supportive role in open complex formation, the DnaA-trio might assist in the process of initial AT-rich DNA-preferential duplex unwinding, reducing the stability of the duplex.

Individual tmaDnaA boxes within minimal tmaDOR are crucial for unwinding

To investigate the mechanisms underlying tmaDnaA-complex formation, the roles of individual tmaDnaA boxes in DUE unwinding were analyzed. DNase I footprint analyses show binding of ATP-tmaDnaA to tmaDnaA boxes 1 to 5 within tmaDOR (9), a finding supported by the EMSA results in the present study (Fig. S4). EMSA showed co-operative binding of ATP-tmaDnaA molecules to tmaDOR, as well as ADP-tmaDnaA binding to tmaDOR, the latter resulting from the absence of a competitor DNA and the occurrence of cage effects impeding diffusion, differing from the results of DNase I footprint experiments. In addition, deletion of tmaDnaA box 5 from minimal tma-oriC is found to reduce the DUE unwinding activity to ∼50% of the intact sequence (40). Residual activity is completely abolished by the simultaneous deletion of tmaDnaA boxes 4 and 5, suggesting that these tmaDnaA boxes are essential for activity (40).

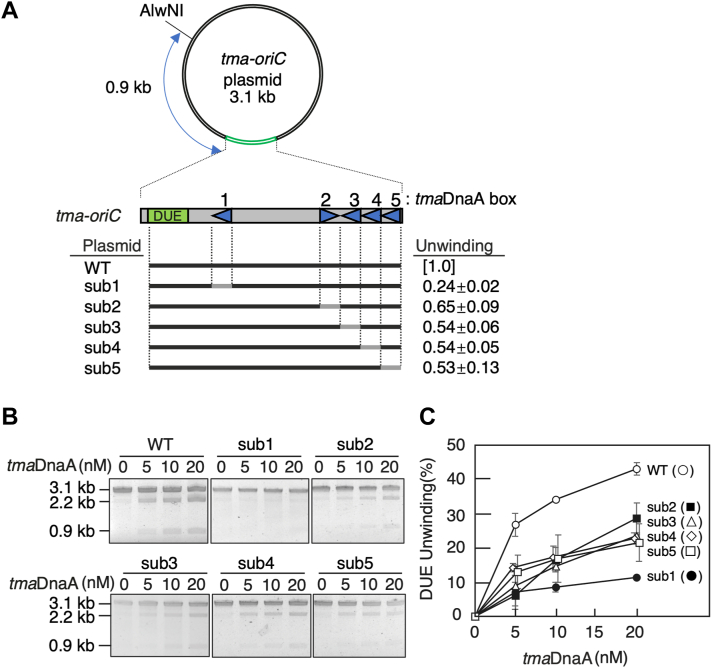

The requirements for individual tmaDnaA boxes 1 to 5 were analyzed by performing P1 nuclease assays using a set of minimal tma-oriC plasmid pOZ14 derivatives in which each tmaDnaA box sequence was randomized (Fig. 4A). Consistent with previous results, a mutation in tmaDnaA box 4 or 5 each inhibited the unwinding activity by ∼50% (sub4 and sub5 in Fig. 4, A–C). Similarly, randomization of tmaDnaA box 2 or 3 inhibited unwinding activity ∼50% (sub2 and sub3 in Fig. 4, A–C), and randomization of tmaDnaA box 1 almost completely abolished unwinding activity (sub1 in Fig. 4, A–C). These results are consistent with the hypothesis that each of the five tmaDnaA boxes plays a crucial role for full DUE unwinding activity. The stricter requirement of tmaDnaA box 1 was also in good agreement with the ssDUE recruitment mechanism, in that ATP-tmaDnaA bound to tmaDnaA box 1 brings tmaDUE close to ATP-tmaDnaA complexes on the tmaDnaA-complex–bound region (Fig. 3, A and B).

Figure 4.

Each of the tmaDnaA boxes 1 to 5 within tmaDOR is important for DUE unwinding. Open complex formation by wildtype (WT) tma-oriC and its mutant derivatives (sub1-5), analyzed by P1 assays as described in the legend to Figure 2. A, schematic illustration of the tma-oriC plasmids. Gray bars indicate base substitutions, in which the 12-mer sequence, including the 9-mer tmaDnaA box and its surrounding nucleotides, was replaced by the randomized sequence 5′-CCCAAGCAACAA-3’ (9). The WT sequence is indicated by bold bars. B, representative gel images. C, quantitative data (n = 2) shown as in Figure 2. The mean ± standard deviation activity relative to that of WT at a tmaDnaA concentration of 20 nM are also shown. DOR, DnaA oligomerization region; DUE, duplex unwinding element; tma, Thermotoga maritima.

Intact DNA helical turn between DUE and DOR is crucial for unwinding

To investigate the mechanisms required for open complex formation, importance of DNA helical turn differences in the tmaDnaA box 1-box 2 intervening region in tmaDUE unwinding was analyzed (Fig. 5A). Specifically, this study hypothesized that if the ssDUE recruitment mechanism was responsible for open complex formation, then inserting a full (10 bp) turn of a DNA helix would allow this region to retain its phasing, resulting in sustained unwinding activity (Fig. 5B). Conversely, inserting a half (5 bp) turn of a DNA helix would alter the phasing between the tmaDUE-tmaDnaA box 1 region and tmaDnaA boxes 2 to 5, altering the interaction modes between the ATP-tmaDnaA complexes and impairing interactions between the tmaDUE and DnaA complexes.

Figure 5.

The DNA helical turn between DUE and DOR underlies DUE unwinding. A, the structure of the tma-oriC plasmids. Wildtype (WT) and mutant tma-oriC plasmids are shown as described in the legend to Figure 2. The positions of base insertions are indicated by small (+5) or large (+10) arrowheads. The amounts of the open complex at 20 nM tmaDnaA (unwinding) are shown relative to that of WT. B, schematic presentation of the altered phasing between tmaDUE and a tmaDnaA-complex–bound region resulting from a 5 or 10 bp insertion within tmaDOR. Presumable conformations of the complexes are shown based on the ssDUE recruitment mechanism. Inserted sequences are shown. tmaDnaA and tmaDnaA boxes are shown similar to that of E. coli DnaA in Figure 1 and the DnaAs in Figure 2, respectively. eTrio in tmaDUE is indicated by yellow rectangles. C and D, open complex formation. WT and mutant tma-oriC plasmids were analyzed by P1 nuclease assays, as described in the legend to Figure 2. C, representative gel images and (D) quantitative data (n = 2) are shown as in Figure 2. DOR, DnaA oligomerization region; DUE, duplex unwinding element; eTrio, extended Trio; ss, single-stranded; tma, Thermotoga maritima.

These possibilities were tested by performing P1 nuclease assay using mutant tma-oriC plasmids with either a 5 bp or 10 bp insertion at a position flanking box 1 or box 2. DUE unwinding activity was fully preserved by insertion of a 10 bp fragment but was reduced by insertion of a 5 bp fragment (Fig. 5, C and D). These observations are in good agreement with the ssDUE recruitment mechanism, in that appropriate phasing between the DnaA complexes promotes these interactions via DNA looping, making this conformation crucial for the open complex at tma-oriC.

Involvement of the Arg-finger in open complex formation

It was unclear whether a conventional AAA+-family-type head-to-tail interaction was involved in the formation of the open complex at tma-oriC. Evaluation of the E. coli DOR showed that the direct repeats of DnaA boxes reinforced formation of ATP-DnaA oligomers in a head-to-tail manner via interactions between the DnaA Arg285 Arg-finger and ATP bound to the adjacent protomer (14, 15) (Fig. 1B). Although the Arg-finger motif was found to be conserved at position 251 in tmaDnaA, the minimal tma-oriC includes an inverted tmaDnaA box 2. Thus, the mechanism by which the tmaDnaA box 2-bound tmaDnaA protomer interacts with the flanking tmaDnaA protomers within the functional complex was unclear. Because previous DNase I footprint assays showed that ATP-tmaDnaA, but not ADP-tmaDnaA, binds co-operatively to the region from tmaDnaA box 2 to box 5 (9), then the tmaDnaA associated with the inverted tmaDnaA box 2 should sustain its ability to interact with the adjacent tmaDnaA molecule bound to tmaDnaA box 3 through either conventional head-to-tail or nonconventional head-to-head interactions through the AAA+ domains.

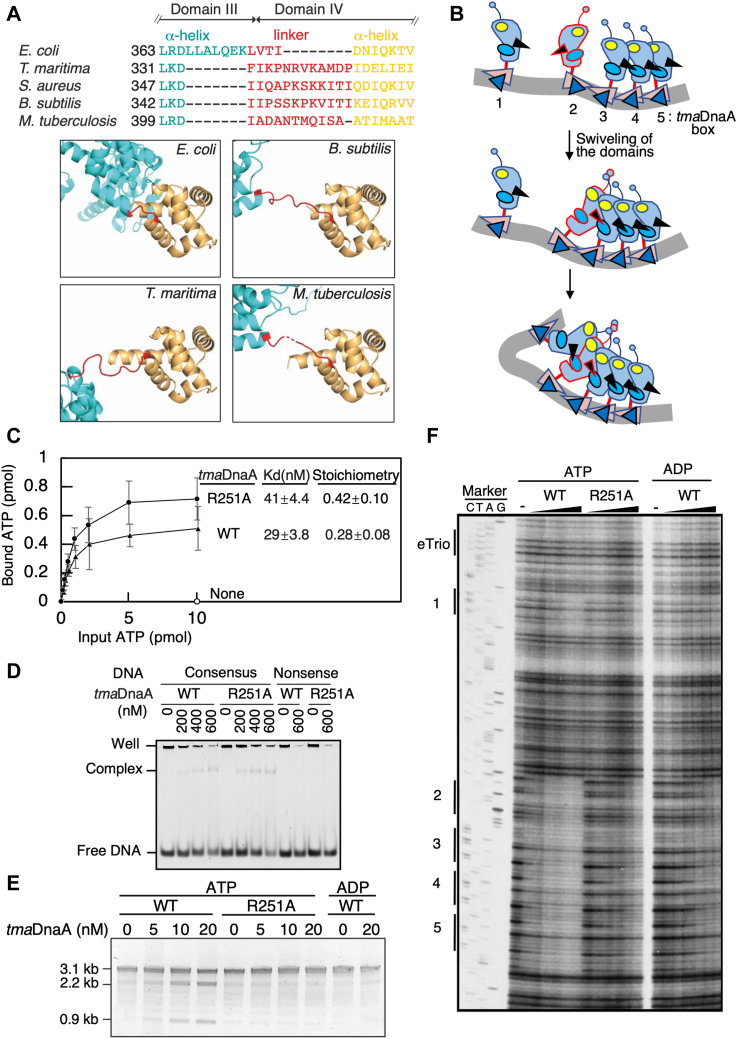

In E. coli DnaA, the C terminus of domain III (the AAA+ domain) is connected to the N terminus of domain IV (the DnaA box-binding domain) via a short flexible linker consisting of amino acids Leu367-Thr375, with the flexibility of this linker allowing limited swiveling of the two domains, as suggested by a study of the molecular dynamics underlying the construction of DnaA pentamers on left and right DORs (8). AlphaFold2-based structural model consistently suggested that E. coli DnaA contains a short flexible linker consisting of only four amino acid residues, Lue373-Ile376 (47). By contrast, similar modeling suggested that tmaDnaA and other representative DnaA orthologs have corresponding linkers with a longer region consisting of 11 to 12 amino acid residues, allowing greater swiveling of the domains (Fig. 6A). Thus, a tmaDnaA protomer bound to the inverted tmaDnaA box 2 may use its flexible linker to revolve around its AAA+ domain, bringing the Arg-finger close to the ATP at the adjacent protomer bound to tmaDnaA box 3 (Fig. 6B). The resultant head-to-tail interaction would stabilize the overall structure formed on tmaDnaA boxes 2 to 5.

Figure 6.

The Arg251 Arg-finger of tmaDnaA is required for open complex formation. A, longer linkers between DnaA domains III and IV in DnaA orthologs than in E. coli DnaA. (upper panel) Alignment of the amino acid residues (red letters) forming the predicted linkers of E. coli DnaA and the indicated DnaA orthologs. (lower panel) DnaA structures predicted using AlfaFold2, with the predicted structures spanning the region from the C terminus of domain III to the N terminus of domain IV shown for comparison; linker regions are indicated in red. B, model for the Arg-finger–mediated oligomerization of the tmaDnaA proteins on tmaDnaA boxes 2 to 5. ATP-tmaDnaA binds to each tmaDnaA box, with the protomers on tmaDnaA boxes 3 to 5 interacting in a head-to-tail manner through the function of the Arg-finger. Swiveling of the AAA+ domain of tmaDnaA on box 2 allows the Arg-finger–mediated interaction of ATP-tmaDnaA with the tmaDnaA trimer on boxes 2 to 3, stabilizing the overall structure of the ATP-tmaDnaA tetramer constructed on the region encompassing tmaDnaA boxes 2 to 5. C, ATP-binding activity. Wildtype (WT) tmaDnaA or tmaDnaA R251 was mixed with various concentrations of radiolabeled ATP, followed by filter retention assays. Mean ± standard deviation activity (n = 3) are shown. The dissociation constant (Kd) and stoichiometry deduced from the Scatcherd plot are also indicted. D, DNA-binding activity. ADP-forms of WT tmaDnaA or tmaDnaA R251A were incubated with 18 bp DNA (300 nM) containing tmaDnaA box 1 (5′-AGACCACCTACCACATAA-3’; tmaDnaA box is underlined) or a nonsense DNA (5′-AGACCCAAGCAACAATAA-3′), followed by EMSA using an 8% polyacrylamide gel. E, open complex formation. The DUE unwinding activities of ATP-tmaDnaA, ADP-tmaDnaA, and ATP-tmaDnaA R251 proteins were analyzed using pOZ14 DNA, as described in the legend to Figure 2. F, DNase I footprint. Various concentrations (0, 20, 40, 80, 150, 300, and 450 nM) of ATP-tmaDnaA (ATP, WT), ADP-tmaDnaA (ADP, WT), or ATP-tmaDnaA R251A (ATP, R251A) were incubated for 10 min at 48 °C in buffer containing 32P-labeled tma-oriC DNA (10 nM), followed by DNA digestion with DNase I, 5% sequencing gel electrophoresis, and visualization using a BAS2500 Bio-imaging analyzer. The positions of DnaA boxes 1 to 5 and eTrio are determined by Sanger sequencing marker. AAA+, ATPases associated with diverse cellular activities; DUE, duplex unwinding element; EMSA, electrophoretic mobility shift assay; tma, Thermotoga maritima.

To confirm this hypothesis, the dependence of the co-operative ATP-tmaDnaA interactions within the tmaDnaA-complex–bound region on the Arg-finger motif was assessed. To investigate the specific role of this motif, a tmaDnaA variant containing an Ala residue, rather than an Arg residue, at amino acid 251 was purified (R251A). A filter retention assay demonstrated that the affinity of tmaDnaA R251A for ATP or ADP was comparable to that of WT tmaDnaA (Figs. 6C and S5). Moreover, EMSA using a DNA carrying a single consensus tmaDnaA box sequence demonstrated that the tmaDnaA box-binding activity of tmaDnaA R251A was similar to that of WT tmaDnaA (Fig. 6D). Thus, the Arg-finger of tmaDnaA is not required for binding to either ATP or a single tmaDnaA box. By contrast, a P1 nuclease assay showed that tmaDnaA R251A is virtually inactive for unwinding DUE, indicating that the Arg-finger is essential for open complex formation (Fig. 6E). These properties are fully consistent with those of the E. coli Arg-finger variant DnaA R285A (14).

DNase I footprint assays were subsequently performed to determine whether the Arg-finger was required for co-operative ATP-tmaDnaA binding on the tma-oriC. The region encompassing tmaDnaA boxes 2 to 5 was found to be readily protected against DNase I at low ATP-tmaDnaA concentrations (i.e., 20 nM), whereas much higher concentrations of ATP-tmaDnaA (300–450 nM) were required for protection of tmaDnaA box 1 (9) (Fig. 6F). Conversely, only high ADP-tmaDnaA (300–450 nM) protected these tmaDnaA boxes against DNase I. These profiles were fully consistent with our previous findings and with results indicating that ATP-tmaDnaA, but not ADP-tmaDnaA, binds co-operatively to the tmaDnaA-complex–bound region. Notably, the footprint patterns of ATP-tmaDnaA R251A were virtually indistinguishable from those of WT ADP-tmaDnaA. These results indicated that co-operative ATP-tmaDnaA binding to the region encompassing tmaDnaA boxes 2 to 5 is strictly dependent on the R251 Arg-finger, supporting a model in which tmaDnaA co-opts conventional head-to-tail interactions to form an open complex at tma-oriC, despite the involvement of the inverted tmaDnaA box 2.

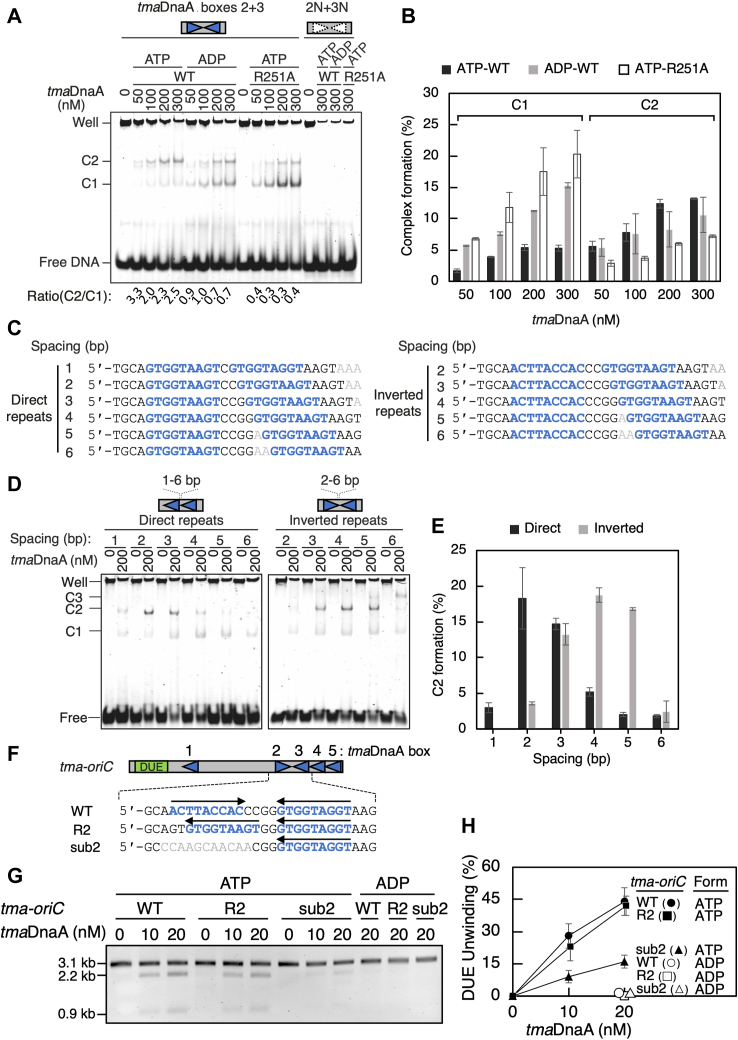

Inverted tmaDnaA boxes permit ATP-tmaDnaA interactions in a head-to-tail manner

To provide further evidence for this model, EMSA was performed using a DNA fragment with oppositely oriented tmaDnaA boxes 2 and 3. Canonical head-to-tail interactions should stabilize the binding of the two tmaDnaA molecules on DNA in a manner dependent on both ATP and the Arg-finger. Indeed, when WT ATP-tmaDnaA was used, the predominant DNA complex contained two tmaDnaA molecules (C2), whereas the complex containing one tmaDnaA molecule (C1) was barely detected (Fig. 7, A and B). This preference for C2 formation was evident even at limited concentrations of ATP-tmaDnaA (50, 100 nM). By contrast, C1 was the major product when WT ADP-tmaDnaA or ATP-tmaDnaA R251A was used. Thus, both ATP and the Arg-finger are involved in the efficient formation of C2 complexes. The residual amounts of C2 formed by WT ADP-tmaDnaA and ATP-tmaDnaA R251A suggest that subpopulations of these tmaDnaA molecules could interact with each other in a manner dependent on neither ATP nor the Arg-finger: as observed for E. coli and Streptomyces lividans DnaAs (21, 23, 48, 49), weak domain I–domain I interaction and head-to-head domain III–domain III interaction might be involved.

Figure 7.

Binding of tmaDnaA on DNA with two tandem tmaDnaA boxes. A and B, ATP- or ADP-bound wildtype tmaDnaA or ATP-bound tmaDnaA R251A was incubated with a 30 bp DNA (300 nM) containing tmaDnaA boxes 2 and 3 (tmaDnaA boxes 2 and 3) or with a DNA fragment lacking tmaDnaA boxes (2N and 3N). A, visualization of the tmaDnaA–DNA complexes (C1 and C2) by 8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and GelStar staining. B, percentages of the tmaDnaA–DNA complexes (C1 and C2) relative to input DNA. C–E, ATP-tmaDnaA (200 nM) was incubated with a 32 bp DNA (100 nM) containing direct or inverted repeats of tmaDnaA boxes, with various spaces between boxes. C, sequences of the substrate DNA. D, visualization of the C2 complexes by 8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and GelStar staining. E, percentages of C2 relative to input DNA. F–H, open complex formation. The P1 assay was performed as described in the legend to Figure 2. The tma-oriC mutant derivatives with inverted tmaDnaA box 2 (R2) or randomized tmaDnaA box 2 (Sub) are illustrated schematically (F). The gel image (G) and mean ± standard deviation percentages of P1 nuclease-digested DNA (n = 3) quantified by FIJI software (H) are shown respectively. Form, ATP- or ADP-forms of tmaDnaA. tma, Thermotoga maritima.

The dependence of C2 formation on the spatial arrangement of the two repeated tmaDnaA boxes was evaluated by EMSA using a set of direct or inverted repeats of tmaDnaA boxes with different interspacing distance. The results suggested that formation of C2 depends on appropriate spacing between two tmaDnaA boxes and their orientation (Fig. 7, C–E). Specifically, maximum C2 formation by two identically oriented tmaDnaA boxes was observed when they were separated by 2 bp, as shown in the arrangements of tmaDnaA boxes 3 to 4 and boxes 4 to 5. By contrast, maximum C2 formation by two inverted tmaDnaA boxes was observed when they were separated by 4 bp interspace, as observed for tmaDnaA boxes 2 to 3. Interestingly, a subpopulation of ATP-tmaDnaA showed formation of a higher ordered complex C3 on the inverted tmaDnaA repeat with separations of 5 or 6 bp (Fig. 7D). These findings suggest that there may be an as yet uncharacterized mode of inter-ATP–tmaDnaA interactions on DNA. Moreover, the intervening space between two tmaDnaA boxes and their orientation are key determinants for efficient formation of these dimeric complexes.

Finally, to confirm the concept that the inverted repeats of tmaDnaA boxes allow for head-to-tail ATP–tmaDnaA interactions to form an open complex at tma-oriC, a P1 nuclease assay was performed using a tma-oriC mutant derivative bearing the reversed tmaDnaA box 2, aligning tmaDnaA boxes 2 to 4 in the same direction with a 2-bp interspace (R2 in Fig. 7F). As a result, the unwinding activity of this mutant plasmid was comparable to that of the WT tma-oriC plasmid (Fig. 7, G and H). This finding contrasts with the compromised unwinding activity observed in the mutant plasmid with a randomized tmaDnaA box 2 (Figs. 4 and 7, G and H). These observations suggest that tmaDnaA box 2 is involved in open complex formation, regardless of its direction, highlighting a tunable nature of DnaA box orientation in the formation of bacterial initiation complexes at the origin.

Discussion

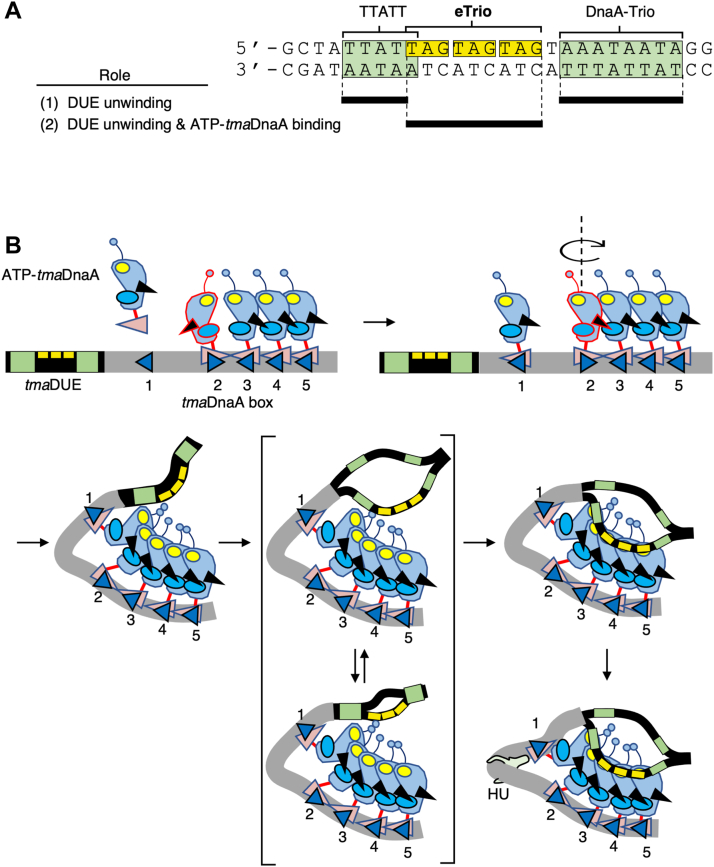

In bacteria, despite the significant sequence homology among the DnaA family of proteins, the origins of bacterial genomes differ substantially in the number of DnaA boxes and their spatial arrangements. Moreover, the unwinding sequences have been insufficiently determined due to the lack of in-depth characterization using in vitro reconstituted systems. The present study analyzed in vitro reconstituted open complexes of the deep-branching hyperthermophilic bacterium, T. maritima, and identified eTrio consisting of three direct repeats of the trinucleotide TAG as a novel functional module within the unwinding sequences (Fig. 8A). These in vitro reconstituted systems using ATP-tmaDnaA and tma-oriC provide concrete evidence that single-stranded eTrio interacts directly with ATP-tmaDnaA oligomers constructed on tmaDOR, thereby facilitating formation of the open complex. Moreover, the full activity of the open complex was dependent on the appropriate phasing between tmaDUE-tmaDnaA box 1 and tmaDnaA boxes 2 to 5. These observations strongly suggest that ssDUE recruitment underlies the formation of the tripartite complex consisting of ATP-tmaDnaA, tmaDOR, and single-stranded eTrio (Fig. 8B). Because the right part of tmaDOR, spanning tmaDnaA boxes 3 to 5, is responsible for single-stranded DNA binding, and because a single DnaA molecule can be in direct contact with up to three nucleotides (9, 13), each tmaDnaA box-bound ATP-tmaDnaA protein on the right tmaDOR likely senses a single TAG trinucleotide. tmaDnaA box 2-bound tmaDnaA might enhance this interaction by stimulating conformational changes of the tma–oriC complex (also see below).

Figure 8.

Model for ssDUE recruitment mechanism in T. maritima. A, structure of tmaDUE. The three tandem TAG repeats of eTrio are highlighted in yellow, and the TTATT motif and DnaA-trio are highlighted in green. Black bars indicate sites with crucial roles in DUE unwinding and/or ssDUE binding. B, model for open complex formation. The swiveled ATP-tmaDnaA bound to tmaDnaA box 2 facilitates formation of ATP-tmaDnaA pentamers on tmaDOR in a head-to-tail manner, inducing tmaDUE unwinding. While TTATT and DnaA-trio engage in efficient DUE unwinding, the single-stranded eTrio directly binds to ATP-tmaDnaA trimers bound to tmaDnaA boxes 3 to 5, stabilizing the unwound state. A presumable HU binding to the spacer between tmaDnaA boxes 1 and 2 further stabilizes open complex formation. DOR, DnaA oligomerization region; DUE, duplex unwinding element; eTrio, extended Trio; ss, single-stranded; tma, Thermotoga maritima.

Scrambling the sequences upstream and downstream of eTrio moderately inhibits duplex DNA unwinding. Although these regions have possible ssDUE-binding motifs, those have activities that are functionally distinct from those of eTrio in the stimulation of DUE unwinding. In papillomavirus, the adenine-thymine tracts flanked by the recognition sites of the initiator protein E2 are crucial for initiation of replication. Although these tracts are not in direct contact with the E2 protein, they display intrinsic DNA bending, thereby facilitating the ability of E2 proteins to recognize their binding sites (50). Similarly, the two AT-rich DNA regions flanking eTrio could contribute to local structural changes by destabilizing the duplex, thereby stimulating efficient unwinding of DUE and subsequent ssDUE binding to tmaDnaA.

Taken together, these findings suggest a mechanism for open complex formation in T. maritima (Fig. 8B). ATP-tmaDnaA proteins preferentially form a head-to-tail tetramer on tmaDnaA boxes 2 to 5. The flexible nature of the linker between tmaDnaA domains III and IV would allow considerable swiveling of the domains, whereby a tmaDnaA protomer bound to the inverted tmaDnaA box 2 swivels around its AAA+ domain to bring the Arg-finger close to the ATP on the adjacent protomer bound to tmaDnaA box 3. When tmaDnaA boxes 1 to 5 are all occupied by ATP-tmaDnaA, the ATP-tmaDnaA promoters bound to tmaDnaA boxes 1 and 2 would interact transiently as a result of Brownian motion, inducing tmaDUE unwinding. The unwound ssDUE would be stabilized though direct interaction of eTrio with the ATP-tmaDnaA trimer bound to tmaDnaA boxes 3 to 5. In addition, the interactions between the ATP-tmaDnaA protomers bound to tmaDnaA boxes 1 and 2 would induce bending of the DNA present in the space between tmaDnaA boxes 1 and 2, stimulating ssDUE recruitment and stable unwinding. The site-specific HU binding to this space was recently exemplified using DMS footprint experiments (51). Given HU homologs are ubiquitous in the bacterial kingdom and HU-accessible interspaces between two DnaA boxes are basically present in the predicted bacterial origins (44, 51), it is conceivable that the HU-promoted ssDUE recruitment mechanism is prevailing among diverse bacterial species. Besides, the unwound region of tmaDUE may further expand over the TTATT and DnaA-trio motifs for stable unwinding and subsequent helicase loading. Expansion of the unwinding regions has been well characterized in open complexes of E. coli (7). This proposed mechanism is also fully consistent with the mechanism underlying ssDUE recruitment.

The observation that single-stranded eTrio is specifically recognized by the DOR-bound tmaDnaA complexes also provides evolutionary insight into the functional structures required for eubacterial DUE. The DnaA-trios of B. subtilis and H. pylori that are crucial for single-stranded DNA binding of their cognate DnaA proteins contain multiple TAG trinucleotides like eTrio of tmaDUE, suggesting that proteins in the DnaA family generally prefer single-stranded TAG repeats (34, 35). Consistently, the DnaA residues responsible for ssDUE binding are highly conserved in DnaA proteins (17). The molecular mechanisms by which E. coli DnaA and tmaDnaA proteins recognize different ssDUE motifs remain to be elucidated in future.

Given the overall sequence dissimilarity of the AT-rich regions within the bacterial origins (Fig. S6), it is puzzling how evolutionarily distal bacteria such as T. maritima, B. subtilis, and H. pylori have co-opted TAG for initiation of replication. These bacteria thrive in different environments, leading us to speculate that the selective pressure for the DUE motifs may be determined by the chemical properties of DNA, rather than the environmental conditions. Supporting this hypothesis, the dinucleotide TA has shown flexible base pair morphology, including the ability to roll, tilt, and twist, thereby destabilizing the duplex structure (52, 53, 54). The DnaA proteins may therefore have evolved to bind to the transiently distorted TA, thereby stabilizing the unwound DNA. This is consistent with results showing that the TTATT motif with a central TA dinucleotide, instead of TAG, is present in E. coli DUE (7, 17). Intriguingly, TAG repeats have been observed in human telomeric DNA. Flexible TA dinucleotides contribute to pronounced DNA distortions necessary for formation of human telomeric nucleosome core particles (55).

The finding that inverted repeats of tmaDnaA boxes can assist in head-to-tail interactions of ATP-tmaDnaA protomers expands the view of tunability in the formation of bacterial initiation complexes at the origin. The predicted origins corresponding to the representative DnaA orthologs contain inverted DnaA boxes (Figs. 1 and S1). As in tmaDnaA, the central AAA+ domain and the C-terminal DNA-binding domain in most, if not all, of those DnaA orthologs, are structurally predicted to be connected by flexible linkers containing 11 to 12 amino acid residues, which could engage in head-to-tail DnaA oligomerization on inverted repeats of DnaA boxes to form an initiation complex via the mechanism described in this study. Conversely, the array of direct DnaA box repeats at the E. coli origin represents a head-to-tail oligomerization of ATP-DnaA. Because E. coli DnaA carries a relatively short and presumably less flexible linker between the AAA+ and C-terminal DNA-binding domains, this linker likely coevolved with the architecture of the origin to maximize the efficiency of formation of the initiation complex. The E. coli chromosome also carries an inverted repeat of the DnaA box motifs within the DnaA-reactivating sequences 1 and 2, specific chromosomal loci for ADP-DnaA assembly that promote ATP-DnaA production by nucleotide exchange of ADP-DnaA (1, 56). This activity is facilitated by a head-to-head interaction of DnaA protomers on the inverted DnaA boxes (48). Thus, E. coli DnaA utilizes the structural constraint of the linker between the AAA+ and C-terminal DNA-binding domains to enhance regulatory systems on DnaA or to expand their repertoire.

In nature, the ssDUE recruitment mechanism has been co-opted, even by non-“DnaA-oriC” replication systems. This is exemplified by a recent study of V. cholerae ori2 where the RctB initiator drives replication initiation (37). Similarly, the ssDUE recruitment mechanism could underlie initiation of the RK2 plasmid with the TrfA initiator (57). In either case, short oligonucleotide repeats are tandemly aligned in their corresponding DUEs, six direct repeats of ATCA in V. cholerae ori2 DUE and four direct repeats of GGTT in RK2 plasmid DUE. These repeated sequences are likely favored by their cognate initiator proteins. Based on the mechanisms of action of different initiator proteins, these origins may have evolved independently from the DnaA-oriC system, thus expanding the mechanisms for ssDUE recruitment.

Experimental procedures

Strains and proteins

E. coli strain DH5α was used for cloning. E. coli HU, WT tmaDnaA, and tmaDnaA R251A were purified as described previously (40). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was purchased from Roche and P1 nuclease from Wako.

Buffers

Buffer E consisted of 60 mM Hepes-KOH (pH 7.6), 130 mM potassium glutamate, 7 mM EDTA, 7.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.01% Triton X-100, 0.32 mg/ml BSA, 20% glycerol, and 3 μM ATP. Buffer P consisted of 60 mM Hepes-KOH (pH 7.6), 8 mM magnesium acetate, 0.1 mM zinc acetate, 30% glycerol, 0.32 mg/ml BSA, 100 mM potassium chloride, and 5 mM ATP. Buffer G consisted of 20 mM Hepes-KOH (pH 7.6), 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 4 mM dithiothreitol, 5 mM magnesium acetate, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, and 50 mM ammonium sulfate.

DNA

The plasmids and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pOZ14 | A 3.1 kb pBluescript II derivative bearing a 149 bp minimal tma-oriC | (40) |

| pOZ14_Trio-A1 | A pOZ14 derivative with modified DUE | This study |

| pOZ14_Trio-A2 | A pOZ14 derivative with modified DUE | This study |

| pOZ14_U | A pOZ14 derivative with modified DUE | This study |

| pOZ14_B | A pOZ14 derivative with modified DUE | This study |

| pOZ14_Trio | A pOZ14 derivative with modified DUE | This study |

| pOZ14_U&Trio | A pOZ14 derivative with modified DUE | This study |

| pOZsub1 | A pOZ14 derivative in which the sequence of tmaDnaA box 1 is randomized | (9) |

| pOZsub2 | A pOZ14 derivative in which the sequence of tmaDnaA box 2 is randomized | (9) |

| pOZsub3 | A pOZ14 derivative in which the sequence of tmaDnaA box 3 is randomized | (9) |

| pOZsub4 | A pOZ14 derivative in which the sequence of tmaDnaA box 4 is randomized | (9) |

| pOZsub5 | A pOZ14 derivative in which the sequence of tmaDnaA box 5 is randomized | (9) |

| pOZ14_a+5 | A pOZ14 derivative with a 5 bp insert between tmaDnaA boxes 1 and 2 | This study |

| pOZ14_a+10 | A pOZ14 derivative with a 10 bp insert between tmaDnaA boxes 1 and 2 | This study |

| pOZ14_b+5 | A pOZ14 derivative with a 5 bp insert between tmaDnaA boxes 1 and 2 | This study |

| pOZ14_b+10 | A pOZ14 derivative with a 10 bp insert between tmaDnaA boxes 1 and 2 | This study |

| pOZ14_R2 | A pOZ14 derivative in which the sequence of tmaDnaA box 2 is reversed | This study |

| pTHMA-1 | A plasmid for purification of wildtype tmaDnaA | (40) |

| pTMA R251A | A pTHMA-1 derivative carrying the tmaDnaA R251A allele | This study |

Table 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′-3′) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 305_PAT3 | GGGGACGCAGGTGGTAGGTTTC | (40) |

| 306_PBS2 | GTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGA | (40) |

| 614_EMSA | CCCCCCCCCTAGCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC | This study |

| 615_EMSA | CCCCCCCCCTAGTAGCCCCCCCCCCCCC | This study |

| 799_B | AGTGGATCCTGCTATTATATCATCATCTAAATAATAGGGGACGCAGGTGGTA | This study |

| 803_U | AGTGGATCCTGCATAATATAGTAGTAGTAAATAATAGGGGACGCAGGTGGTA | This study |

| 804_Trio | AGTGGATCCTGCTATTATTAGTAGTAGATTTATTATGGGGACGCAGGTGGTAGGTTTCGAG | This study |

| 805_U&Trio | AGTGGATCCTGCATAATATAGTAGTAGATTTATTATGGGGACGCAGGTGGTAGGTTTCGAG | This study |

| 823_PBS1 | AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAAC | (40) |

| 824_b+5 | ATCGAATTCAAACCTACCACTTACCTACCACTTACCTACCACCCGGGTGGTAAGTTGCAGACATGCTTTCATTAAAAGCCTCATCAGAAGCCT | This study |

| 825_b+10 | ATCGAATTCAAACCTACCACTTACCTACCACTTACCTACCACCCGGGTGGTAAGTTGCAGACAATTGTTGCTTTCATTAAAAGCCTCATCAGAAGCCT | This study |

| 887_EMSA | CCCCCCCCTAGTAGTAGCCCCCCCCCCC | This study |

| 888_EMSA | CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCTAAATAATACC | This study |

| 889_EMSA | CCCCCCCCTAGTAGTAGTAACCCCCCCC | This study |

| 890_EMSA | CCCCCCCCTAGTAGTAGTAAATACCCCC | This study |

| 912_a+5 | AGTGGATCCTGCTATTATTAGTAGTAGTAAATAATAGGGGACGCAGGTGGTAGGTTTCGAGTATTAAGCAGAAATTTTTGAACAGGCTTCTGATG | This study |

| 913_a+10 | AGTGGATCCTGCTATTATTAGTAGTAGTAAATAATAGGGGACGCAGGTGGTAGGTTTCGAGTATTAAGCAACAATGAAATTTTTGAACAGGCTTCTGATG | This study |

| 929_Trio-A1 | AGTGGATCCTGCTATTATTAGTAGTAGTAAATTATAGGGGACGCAGGTGGTAGGTTTC | This study |

| 930_Trio-A2 | AGTGGATCCTGCTATTATTAGTAGTAGTAAATAATTGGGGACGCAGGTGGTAGGTTTCGAG | This study |

| 1031-Consense-1 | AGAAAACCTACCACCTAA | (40) |

| 1032-Consense-2 | TTAGGTGGTAGGTTTTCT | (40) |

| 1033-Nonsense-1 | AGACCCAAGCAACAATAA | (40) |

| 1034-Nonsense-2 | TTATTGTTGCTTGGGTCT | (40) |

| 1035-9mer-1 | AGACCACCTACCACATAA | This study |

| 1036-9mer-2 | TTATGTGGTAGGTGGTCT | This study |

| 1037-8mer-L-1 | AGACCACCTACCAAATAA | This study |

| 1038-8mer-L-2 | TTATTTGGTAGGTGGTCT | This study |

| 1039-8mer-R-1 | AGACCCCCTACCACATAA | This study |

| 1040-8mer-R-2 | TTATGTGGTAGGGGGTCT | This study |

| 1052-DnaABox2+3_1 | TGCAACTTACCACCCGGGTGGTGGTAAAGT | This study |

| 1053-DnaABox2+3_2 | ACTTTACCACCACCCGGGTGGTAAGTTGCA | This study |

| 1054-DnaABox2+3N_1 | TGCAACTTACCACCCGGTGTTGTTGCAAGT | This study |

| 1055-DnaABox2+3N_2 | ACTTGCAACAACACCGGGTGGTAAGTTGCA | This study |

| 1056-DnaABox2N+3N_1 | TGCACAGGCAACACCGGTGTTGTTGCAAGT | This study |

| 1057-DnaABox2N+3N_2 | ACTTGCAACAACACCGGTGTTGCCTGTGCA | This study |

| 1306_DnaABox 2+3(2)_1 | TGCAACTTACCACCCGTGGTAGGTAAGTGGAA | This study |

| 1307_DnaABox 2+3(2)_2 | TTCCACTTACCTACCACGGGTGGTAAGTTGCA | This study |

| 1308_DnaABox 2+3(3)_1 | TGCAACTTACCACCCGGTGGTAGGTAAGTGGA | This study |

| 1309_DnaABox 2+3(3)_2 | TCCACTTACCTACCACCGGGTGGTAAGTTGCA | This study |

| 1310_DnaABox 2+3(4)_1 | TGCAACTTACCACCCGGGTGGTAGGTAAGTGG | This study |

| 1311_DnaABox 2+3(4)_2 | CCACTTACCTACCACCCGGGTGGTAAGTTGCA | This study |

| 1316_DnaABox 2R+3(1)_1 | TGCAGTGGTAAGTCGTGGTAGGTAAGTGGAAA | This study |

| 1317_DnaABox 2R+3(1)_2 | TTTCCACTTACCTACCACGACTTACCACTGCA | This study |

| 1318_DnaABox 2R+3(2)_1 | TGCAGTGGTAAGTCCGTGGTAGGTAAGTGGAA | This study |

| 1319_DnaABox 2R+3(2)_2 | TTCCACTTACCTACCACGGACTTACCACTGCA | This study |

| 1320_DnaABox 2R+3(3)_1 | TGCAGTGGTAAGTCCGGTGGTAGGTAAGTGGA | This study |

| 1321_DnaABox 2R+3(3)_2 | TCCACTTACCTACCACCGGACTTACCACTGCA | This study |

| 1322_DnaABox 2R+3(4)_1 | TGCAGTGGTAAGTCCGGGTGGTAGGTAAGTGG | This study |

| 1323_DnaABox 2R+3(4)_2 | CCACTTACCTACCACCCGGACTTACCACTGCA | This study |

| 1338_2+3(+5)_1 | TGCAACTTACCACCCAGGGTGGTAGGTAAGTG | This study |

| 1339_2+3(+5)_2 | CACTTACCTACCACCCTGGGTGGTAAGTTGCA | This study |

| 1340_2+3(+6)_1 | TGCAACTTACCACCCAAGGGTGGTAGGTAAGT | This study |

| 1341_2+3(+6)_2 | ACTTACCTACCACCCTTGGGTGGTAAGTTGCA | This study |

| 1342_2R+3(+5)_1 | TGCAGTGGTAAGTCCAGGGTGGTAGGTAAGTG | This study |

| 1343_2R+3(+5)_2 | CACTTACCTACCACCCTGGACTTACCACTGCA | This study |

| 1344_2R+3(+6)_1 | TGCAGTGGTAAGTCCAAGGGTGGTAGGTAAGT | This study |

| 1345_2R+3(+6)_2 | ACTTACCTACCACCCTTGGACTTACCACTGCA | This study |

| 1594_2R_R | ATATCGAATTCAAACCTACCACTTACCTACCACTTACCTACCACCCACTTACCACACTGCAGAC | This study |

| TMA28 | GCTATTATTAGTAGTAGTAAATAATAGG | (9) |

To construct pOZ14_Trio-A1, pOZ14_Trio-A12, pOZ14_a+5, pOZ14_a+10, pOZ14_b+5, pOZ14_b+10, pOZ14_U, pOZ14_B, pOZ14_Trio, pOZ14_U&Trio, and pOZ14_R2, the inserted DNA fragments were amplified by PCR using pOZ14 and mutagenic primers (929/306 for pOZ14_Trio-A1, 930/306 for pOZ14_Trio-A2, 912/306 for pOZ14_a+5, 913/306 for pOZ14_a+10, 824/823 for pOZ14_b+5, 825/823 for pOZ14_b+10, 799/306 for pOZ14_B, 803/306 for pOZ14_U, 804/306 for pOZ14_Trio, 805/306 for pOZ14_U&Trio, and 1594/823 for pOZ14_R2). The amplified products were digested with BamHI and EcoRI and ligated into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of pBluescript II (Stratagene).

To construct pTMA R251A, the mutation was introduced into pTHMA-1 using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Stratagene) (16, 17).

P1 nuclease assay

P1 nuclease assays were performed essentially as described (17, 40). Briefly, ATP-tmaDnaA (0–20 nM) and pOZ14 or its mutant derivatives (400 ng; 4 nM) were incubated in buffer P (50 μl) containing E. coli HU (16 ng; 17 nM) for 10 min at 48 °C, followed by digestion with 1.5 units P1 nuclease for 200 s at 48 °C. The DNA samples were extracted with phenol/chloroform, precipitated with ethanol, and further digested with the restriction enzyme AlwNI. The products were analyzed using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide straining.

P1 assays described in Figure 7, G and H were performed using buffer P containing 40 mM ammonium sulfate, instead of 100 mM potassium chloride, which did not affect the specific nuclease activity.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

EMSAs were performed essentially as described (7, 9). Briefly, ATP-tmaDnaA (0–80 nM) and a 203 bp DNA fragment–containing tmaDOR (30 nM) were incubated for 5 min at 48 °C, followed by electrophoresis on 4% polyacrylamide gels and visualization of tmaDOR using GelStar dye (Lonza). To analyze the formation of ss-tmaDUE–ATP–tmaDnaA–tmaDOR complexes, ATP-tmaDnaA (0–80 nM) and the 203 bp DNA fragment containing tmaDOR (30 nM) were incubated for 5 min at 48 °C; following the addition of 32P-labeled ss-tmaDUE (2.5 nM), the reaction mixtures were incubated for an additional 5 min at 48 °C. The mixtures were subjected to 4% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, with tmaDOR and 32P-labeled ss-tmaDUE visualized using GelStar dye and Typhoon FLA 9500, respectively.

DNase I footprint experiments

DNase I footprint experiments were performed essentially as described (9). Briefly, a 32P-end-labeled tma-oriC fragment (303 bp) was prepared by PCR using pOZ14 DNA and the primers 823 and 32P-end-labeled 306. The labeled DNA (10 nM) was incubated with WT tmaDnaA or tmaDnaA R251A (0–450 nM) for 10 min at 48 °C in buffer G (10 μl) containing 5 mM calcium acetate and 3 mM ATP or ADP, followed by incubation with DNase I (0.83 mU) for 4 min at the same temperature. DNA samples were analyzed by sequencing gel electrophoresis.

Filter retention assay

Filter retention assays were performed as described previously (40). Briefly, WT tmaDnaA or tmaDnaA R251A (1.9 pmol) was preincubated for 5 min at 38 °C in buffer (25 μl) containing 50 mM Hepes-KOH (pH 7.6), 0.3 mM EDTA, 7 mM dithiothreitol, 20% glycerol, 0.007% Triton X-100, and [α-32P] ATP or [3H] ADP. Following addition of 5 mM magnesium acetate, the samples were further incubated on ice for 15 min and filtered through nitrocellulose membranes. The retained radioactivity was quantified using a liquid scintillation counter.

Data availability

All data are available in the article.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information (32).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Christoph Weigel for discussion at a starting stage of this work. We appreciate the technical assistance from the Research Support Center, Research Center for Human Disease Modeling, Kyushu University Graduate School of Medical Sciences.

Author contributions

C. L. and S. O. investigation; C. L., R. Y., T. K., and S. O. validation; C. L., and S. O. writing–original draft; C. L., R. Y., T. K., and S. O. writing–review and editing; T. K. and S. O. supervision.

Funding and additional information

This study was supported by Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research, JSPS KAKENHI Grant numbers: JP18H02377, JP20H03212, JP17H03656, JP21K19233, JP23H02438, and JP23K05640. JSPS predoctoral fellowships (to R. Y.): JP22J11077. Kobayashi Foundation Special Research Fellowship to C. L.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Patrick Sung

Supporting information

References

- 1.Katayama T., Kasho K., Kawakami H. The DnaA Cycle in Escherichia coli: activation, function and inactivation of the initiator protein. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:2496. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grimwade J.E., Leonard A.C. Blocking, bending, and binding: regulation of initiation of chromosome replication during the Escherichia coli cell cycle by transcriptional modulators that interact with origin DNA. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.732270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolański M., Donczew R., Zawilak-Pawlik A., Zakrzewska-Czerwińska J. oriC-encoded instructions for the initiation of bacterial chromosome replication. Front. Microbiol. 2015;5:735. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costa A., Hood I.V., Berger J.M. Mechanisms for initiating cellular DNA replication. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013;82:25–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052610-094414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaguni J.M. Replication initiation at the Escherichia coli chromosomal origin. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2011;15:606–613. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozaki S. Regulation of replication initiation: lessons from Caulobacter crescentus. Genes Genet. Syst. 2019;94:183–196. doi: 10.1266/ggs.19-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakiyama Y., Nagata M., Yoshida R., Kasho K., Ozaki S., Katayama T. Concerted actions of DnaA complexes with DNA-unwinding sequences within and flanking replication origin oriC promote DnaB helicase loading. J. Biol. Chem. 2022;298 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimizu M., Noguchi Y., Sakiyama Y., Kawakami H., Katayama T., Takada S. Near-atomic structural model for bacterial DNA replication initiation complex and its functional insights. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016;113:E8021–E8030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609649113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozaki S., Katayama T. Highly organized DnaA-oriC complexes recruit the single-stranded DNA for replication initiation. Nucl. Acids Res. 2012;40:1648–1665. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felczak M.M., Kaguni J.M. The box VII motif of Escherichia coli DnaA protein is required for DnaA oligomerization at the E. coli replication origin. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:51156–51162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409695200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayashi C., Miyazaki E., Ozaki S., Abe Y., Katayama T. DnaB helicase is recruited to the replication initiation complex via binding of DnaA domain I to the lateral surface of the DnaB N-terminal domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295:1131–1143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.014235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozaki S., Katayama T. DnaA structure, function, and dynamics in the initiation at the chromosomal origin. Plasmid. 2009;62:71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erzberger J.P., Mott M.L., Berger J.M. Structural basis for ATP-dependent DnaA assembly and replication-origin remodeling. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:676–683. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawakami H., Keyamura K., Katayama T. Formation of an ATP-DnaA-specific initiation complex requires DnaA arginine 285, a conserved motif in the AAA+ protein family. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:27420–27430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502764200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noguchi Y., Sakiyama Y., Kawakami H., Katayama T. The Arg fingers of key DnaA protomers are oriented inward within the replication origin oriC and stimulate DnaA subcomplexes in the initiation complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:20295–20312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.662601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozaki S., Noguchi Y., Hayashi Y., Miyazaki E., Katayama T. Differentiation of the DnaA-oriC Subcomplex for DNA unwinding in a replication initiation complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:37458–37471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.372052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozaki S., Kawakami H., Nakamura K., Fujikawa N., Kagawa W., Park S.Y., et al. A common mechanism for the ATP-DnaA-dependent formation of open complexes at the replication origin. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:8351–8362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708684200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujikawa N., Kurumizaka H., Nureki O., Terada T., Shirouzu M., Katayama T., et al. Structural basis of replication origin recognition by the DnaA protein. Nucl. Acids Res. 2003;31:2077–2086. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutton M.D., Carr K.M., Vicente M., Kaguni J.M. Escherichia coli DnaA protein. The N-terminal domain and loading of DnaB helicase at the E. coli chromosomal origin. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:34255–34262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simmons L.A., Felczak M., Kaguni J.M. DnaA Protein of Escherichia coli: oligomerization at the E. coli chromosomal origin is required for initiation and involves specific N-terminal amino acids. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;49:849–858. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abe Y., Jo T., Matsuda Y., Matsunaga C., Katayama T., Ueda T. Structure and function of DnaA N-terminal domains: specific sites and mechanisms in inter-DnaA interaction and in DnaB helicase loading on oriC. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:17816–17827. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701841200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keyamura K., Abe Y., Higashi M., Ueda T., Katayama T. DiaA dynamics are coupled with changes in initial origin complexes leading to helicase loading. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:25038–25050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.002717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Felczak M.M., Simmons L.A., Kaguni J.M. An essential tryptophan of Escherichia coli DnaA protein functions in oligomerization at the E. coli replication origin. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:24627–24633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503684200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nozaki S., Ogawa T. Determination of the minimum domain II size of Escherichia coli DnaA protein essential for cell viability. Microbiology. 2008;154:3379–3384. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/019745-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaper S., Messer W. Interaction of the initiator protein DnaA of Escherichia coli with its DNA target. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:17622–17626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakiyama Y., Kasho K., Noguchi Y., Kawakami H., Katayama T. Regulatory dynamics in the ternary DnaA complex for initiation of chromosomal replication in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:12354–12373. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rozgaja T.A., Grimwade J.E., Iqbal M., Czerwonka C., Vora M., Leonard A.C. Two oppositely oriented arrays of low-affinity recognition sites in oriC guide progressive binding of DnaA during Escherichia coli pre-RC assembly. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;82:475–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07827.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGarry K.C., Ryan V.T., Grimwade J.E., Leonard A.C. Two discriminatory binding sites in the Escherichia coli replication origin are required for DNA strand opening by initiator DnaA-ATP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:2811–2816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400340101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar S., Farhana A., Hasnain S.E. In-vitro helix opening of M. tuberculosis oriC by DnaA occurs at precise location and is inhibited by IciA like protein. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pei H., Liu J., Li J., Guo A., Zhou J., Xiang H. Mechanism for the TtDnaA-Tt-oriC cooperative interaction at high temperature and duplex opening at an unusual AT-rich region in Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis. Nucl. Acids Res. 2007;35:3087–3099. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaworski P., Donczew R., Mielke T., Weigel C., Stingl K., Zawilak-Pawlik A. Structure and function of the Campylobacter jejuni chromosome replication origin. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:1–18. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong M.J., Luo H., Gao F. DoriC 12.0: an updated database of replication origins in both complete and draft prokaryotic genomes. Nucl. Acids Res. 2023;51:D117–D120. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang D.S., Kornberg A. Opposed actions of regulatory proteins, DnaA and IciA, in opening the replication origin of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:23087–23091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson T.T., Harran O., Murray H. The bacterial DnaA-Trio replication origin element specifies single-stranded DNA initiator binding. Nature. 2016;534:412–416. doi: 10.1038/nature17962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaworski P., Zyla-uklejewicz D., Nowaczyk-cieszewska M., Donczew R., Mielke T., Weigel C., et al. Putative cooperative ATP–DnaA binding to double-stranded DnaA Box and single-stranded DnaA-Trio motif upon Helicobacter pylori replication initiation complex assembly. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:6643. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richardson T.T., Stevens D., Pelliciari S., Harran O., Sperlea T., Murray H. Identification of a basal system for unwinding a bacterial chromosome origin. EMBO J. 2019;38 doi: 10.15252/embj.2019101649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chatterjee S., Jha J.K., Ciaccia P., Venkova T., Chattoraj D.K. Interactions of replication initiator RctB with single-and double-stranded DNA in origin opening of Vibrio cholerae chromosome 2. Nucl. Acids Res. 2020;48:11016–11029. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhaxybayeva O., Swithers K.S., Lapierre P., Fournier G.P., Bickhart D.M., DeBoy R.T., et al. On the chimeric nature, thermophilic origin, and phylogenetic placement of the Thermotogales. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:5865–5870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901260106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuwabara T., Igarashi K. Thermotogales origin scenario of eukaryogenesis. J. Theor. Biol. 2020;492 doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2020.110192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozaki S., Fujimitsu K., Kurumizaka H., Katayama T. The DnaA homolog of the hyperthermophilic eubacterium Thermotoga maritima forms an open complex with a minimal 149-bp origin region in an ATP-dependent manner. Genes Cells. 2006;11:425–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lopez P., Forterre P., le Guyader H., Philippe H. Origin of replication of Thermotoga maritima. Trends Genet. 2000;16:59–60. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01894-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swinger K.K., Rice P.A. IHF and HU: flexible architects of bent DNA. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004;14:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryan V.T., Grimwade J.E., Nievera C.J., Leonard A.C. IHF and HU stimulate assembly of pre-replication complexes at Escherichia coli oriC by two different mechanisms. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;46:113–124. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamashev D., Agapova Y., Rastorguev S., Talyzina A.A., Boyko K.M., Korzhenevskiy D.A., et al. Comparison of histone-like HU protein DNA-binding properties and HU/IHF protein sequence alignment. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chodavarapu S., Felczak M.M., Yaniv J.R., Kaguni J.M. Escherichia coli DnaA interacts with HU in initiation at the E. coli replication origin. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;67:781–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hwang D.S., Kornberg A. Opening of the replication origin of Escherichia coli by DnaA protein with protein HU or IHF. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:23083–23086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jumper J., Evans R., Pritzel A., Green T., Figurnov M., Ronneberger O., et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596:583. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sugiyama R., Kasho K., Miyoshi K., Ozaki S., Kagawa W., Kurumizaka H., et al. A novel mode of DnaA-DnaA interaction promotes ADP dissociation for reactivation of replication initiation activity. Nucl. Acids Res. 2019;47:11209–11224. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Majka J., Zakrzewska-Czerwiñska J., Messer W. sequence recognition, cooperative interaction, and dimerization of the initiator protein DnaA of Streptomyces. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:6243–6252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007876200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hizver J., Rozenberg H., Frolow F., Rabinovich D., Shakked Z. DNA bending by an adenine - Thymine tract and its role in gene regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:8490–8495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151247298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yoshida R., Ozaki S., Kawakami H., Katayama T. Single-stranded DNA recruitment mechanism in replication origin unwinding by DnaA initiator protein and HU, an evolutionary ubiquitous nucleoid protein. Nucl. Acids Res. 2023 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Young R.T., Czapla L., Wefers Z.O., Cohen B.M., Olson W.K. Revisiting DNA sequence-dependent deformability in high-resolution structures: effects of flanking base pairs on dinucleotide morphology and global chain configuration. Life. 2022;12:759. doi: 10.3390/life12050759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mack D.R., Chiu T.K., Dickerson R.E. Intrinsic bending and deformability at the T-A step of CCTTTAAAGG: a comparative analysis of T-A and A-T steps within A-tracts. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;312:1037–1049. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Balaceanu A., Buitrago D., Walther J., Hospital A., Dans P.D., Orozco M. Modulation of the helical properties of DNA: next-to-nearest neighbour effects and beyond. Nucl. Acids Res. 2019;47:4418–4430. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Soman A., Liew C.W., Teo H.L., Berezhnoy N. v, Olieric V., Korolev N., et al. The human telomeric nucleosome displays distinct structural and dynamic properties. Nucl. Acids Res. 2021;48:5383–5396. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miyoshi K., Tatsumoto Y., Ozaki S., Katayama T. Negative feedback for DARS2 –Fis complex by ATP–DnaA supports the cell cycle-coordinated regulation for chromosome replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:12820–12835. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wegrzyn K., Fuentes-Perez M.E., Bury K., Rajewska M., Moreno-Herrero F., Konieczny I. Sequence-specific interactions of Rep proteins with ssDNA in the AT-rich region of the plasmid replication origin. Nucl. Acids Res. 2014;42:7807–7818. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the article.