Abstract

The drug pair consisting of Sophora flavescens Aiton (Sophorae flavescentis radix, Kushen) and Coptis chinensis Franch. (Coptidis rhizoma, Huanglian), as described in Prescriptions for Universal Relief (Pujifang), is widely used to treat laxation. Matrine and berberine are the major active components of Kushen and Huanglian, respectively. These agents have shown remarkable anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory effects. A mouse model of colorectal cancer was used to determine the most effective combination of Kushen and Huanglian against anti-colorectal cancer. The results showed that the combination of Kushen and Huanglian at a 1:1 ratio exerted the best anti-colorectal cancer effect versus other ratios. Moreover, the anti-colorectal cancer effect and potential mechanism underlying the effects of matrine and berberine were evaluated by the analysis of combination treatment or monotherapy. In addition, the chemical constituents of Kushen and Huanglian were identified and quantified by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). A total of 67 chemical components were identified from the Kushen–Huanglian drug pair (water extraction), and the levels of matrine and berberine were 129 and 232 µg/g, respectively. Matrine and berberine reduced the growth of colorectal cancer and relieved the pathological conditions in mice. In addition, the combination of matrine and berberine displayed better anti-colorectal cancer efficacy than monotherapy. Moreover, matrine and berberine reduced the relative abundance of Bacteroidota and Campilobacterota at phylum level and that of Helicobacter, Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group, Candidatus_Arthromitus, norank_f_Lachnospiraceae, Rikenella, Odoribacter, Streptococcus, norank_f_Ruminococcaceae, and Anaerotruncus at the genus level. Western blotting results demonstrated that treatment with matrine and berberine decreased the protein expressions of c-MYC and RAS, whereas it increased that of sirtuin 3 (Sirt3). The findings indicated that the combination of matrine and berberine was more effective in inhibiting colorectal cancer than monotherapy. This beneficial effect might depend on the improvement of intestinal microbiota structure and regulation of the RAS/MEK/ERK-c-MYC-Sirt3 signaling axis.

Keywords: Sophora flavescens Aiton, Coptis chinensis Franch, matrine, berberine, colorectal cancer, intestinal microbiota, RAS signaling pathway, sirt3

Introduction

Colorectal cancer ranks second among malignant tumors in terms of incidence and is the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality (1, 2). Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are at a higher risk of developing colorectal cancer. This is because the inflammatory reaction influences the development of tumorigenesis, which is involved in the physiological and pathological reaction process (3).

Recently, an increasing number of research studies focus on the role of intestinal microbiota in the development of colorectal cancer (4–8). The abundance of gut microbiota differs between patients with colorectal cancer and healthy individuals (7, 9, 10). For example, Bacteroidetes is more abundant in patients with tubular adenomatous polyps (11). Helicobacter, Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group, Candidatus_Arthromitus, norank_f_Lachnospiraceae, Rikenella, Odoribacter, Streptococcus, norank_f_Ruminococcaceae, and Anaerotruncus play indispensable roles in colorectal tumorigenesis and inflammation (12–20). Gut microbiota regulate signaling pathways to promote or delay tumor progression (21–23). Thus, intestinal flora can directly or indirectly regulate tumor-related signaling pathways and affect tumor progression.

The activation and transformation of RAS, an important component of the family of GTPases, have been association with cancer (24). RAS activates the MEK/ERK cascade, thereby altering the transcription of genes relate to the control of extensive intracellular biological mechanisms. Activated RAS recruits RAF kinase, a MAP kinase kinase (MAP3K), to active MEK. In turn, RAF promotes the activation of the effector ERK kinases. Activated ERK phosphorylates several genes involved in cell growth, differentiation, and motility (25), including c-MYC (26). Abnormal c-MYC is involved in genomic instability and tumorigenesis and maintains tumor growth (27). As far back as 1996, the overexpression of c-MYC is considered as a good prognostic factor for survival in colorectal cancer (28). Furthermore, MYC expression improved acetylation-dependent deactivation of succinate dehydrogenase complex flavoprotein subunit A (SDHA) by activating S-phase kinase-associated protein 2-mediated (SKP2-mediated) degradation of Sirt3 deacetylase and tumorigenesis (29).

In recent years, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has been used for the prevention and treatment of colorectal carcinoma. It has been shown that TCM inhibits tumorigenesis, improves the therapeutic effect, reduces toxicity, and lowers the risk of recurrence and metastasis (30–34). The effect of TCM on the regulation of intestinal flora is attracting increasing research attention (35–38).

Sophora flavescens Aiton (Sophorae flavescentis radix, Kushen) and Coptis chinensis Franch (Coptidis rhizoma, Huanglian) are commonly used in the treatment of intestinal diseases. The earliest use of this drug pair was recorded in the Prescriptions for Universal Relief (Pujifang). In addition, it has been reported that Kushen and Huanglian exert good curative effects in the treatment of tumors (39, 40). Matrine and berberine are two alkaloids contained in Kushen and Huanglian, respectively (41, 42). Matrine prevents colorectal cancer by inhibiting the proliferation, invasion, and metastasis, and inducing the apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells (43–45). Berberine exerts anti-colorectal cancer efficacy by regulating proliferation-related signaling pathway, short-chain fatty acid metabolism, intestinal inflammation, and gut microbiota (46–48). All in all, Kushen and Huanglian and their compounds have certain anti-colorectal cancer effects.

However, the most effective combination of the drug pair Kushen–Huanglian in inhibiting colorectal cancer and the mechanisms underlying the anti-colorectal cancer effect of this combination are currently unclear. Further studies are warranted to investigate whether the oral administration of compounds affects the composition of intestinal flora before it is absorbed into the blood to regulated disease-related molecular mechanisms and play a therapeutic role.

In this study, an orthotopic xenograft mouse model of colorectal cancer was used to investigate the anti-colorectal cancer effect of different combinations of Kushen and Huanglian. LC-MS/MS was performed to identify the chemical constituents of the Kushen and Huanglian. We also examined the mechanism underlying the effects of matrine and berberine on the gut flora of mice with colorectal cancer through sequencing and pathway detection.

Material and methods

Chemical and materials

Matrine (purity≥98%, Cat. No. B20679) and berberine (purity≥ 98%, Cat. No. B21379) were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) ( Figures 1H, I ). The hematoxylin–eosin (HE) staining kit (Cat. No. G1120) was obtained from Solarbio (Beijing, China). Antibodies (c-MYC (Cat. No. 18583), phosphorylated-MEK [p-MEK] (Cat. No. 3958), MEK (Cat. No. 2352), p-ERK (Cat. No. 9106), ERK (Cat. No. 9102), Sirt3 (Cat. No. 2627), RAS (Cat. No. 67648), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [GAPDH] (Cat. No. 5174) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Horseradish-peroxidase (HRP)-labeled secondary antibodies (Cat. Nos. ab205718 and ab6789) were obtained from Abcam Plc (Cambridge, UK). Fufang Banmao capsules were produced by Guizhou Ebay Pharmaceutical Corporate Co. Ltd. (Guizhou, China). Acetonitrile gradient grade (Cat. No. 1.06007) for liquid chromatography were purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Kushen (from Chifeng, Inner Mongolia) and Huanglian (from Dazhou, Sichuan province) were purchased from Jiangsu Province Hospital of Chinese Medicine (Nanjing, China).

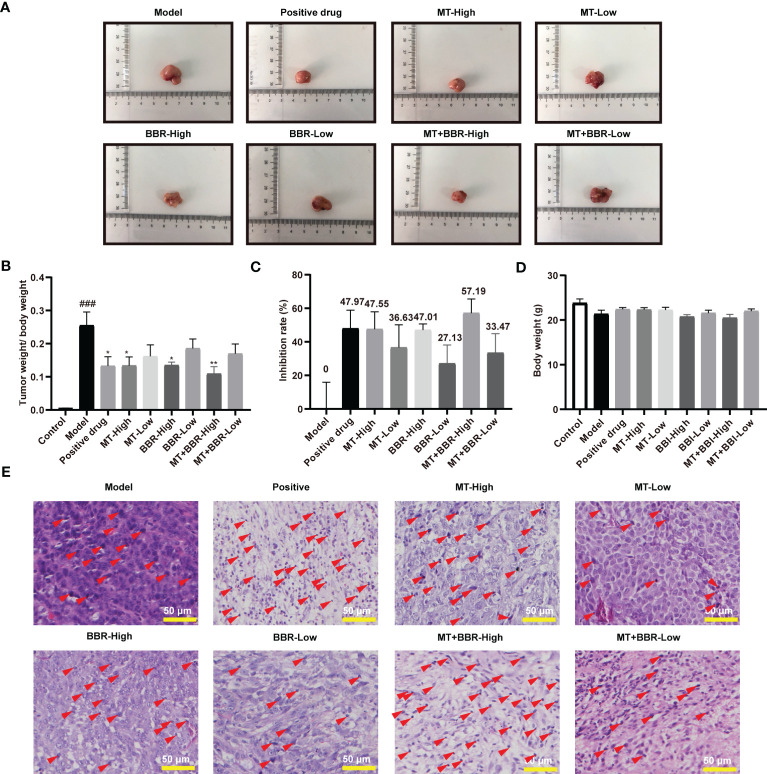

Figure 1.

Kushen and Huanglian extract prevents colorectal tumorigenesis in an orthotopic xenograft mouse model of colorectal cancer; chromatogram of Kushen and Huanglian (1:1) extract. (A) Representative image of tumor tissue from model mice. (B) Tumor weight/body weight of mice (n = 6, ### p < 0.001 compared with Control group, *p < 0.05 compared with Model group). (C) Inhibitory rate of Kushen and Huanglian extract on colorectal cancer in model mice (n = 6). (D) Body weight of mice (n = 6). (E) Representative image of HE-stanned tumor tissue obtained from model mice. Scale bar: 50 μm. (F, G) Total iron chromatogram of Kushen and Huanglian (1:1) extract in ESI+ (F) and ESI− (G) mode. (H, I) MRM chromatogram of matrine (H) and berberine (I). (J–L) MRM chromatogram of matrine and berberine in Kushen and Huanglian extract [(J) 1:1; (K) 1:2; (L) 1:4)]. Red arrows indicate nuclear pyknosis.

Water extraction

For water extraction, Kushen and Huanglian were soaked in water (10× volume) for 30 min at 100°C. This process was repeated in a reduced volume of water (8×). The two extracts were combined and concentrated to 1.6 g crude drug/ml at 60°C. The extraction samples containing 1 g crude drug were dissolved in methanol solution (30 ml) and sonicated for 30 min. Next, the extractions were filtered using a filter unit (pore size, 0.45 μm) and diluted to an appropriate concentration for LC/MS analysis.

LC/MS analysis

An AB Sciex 5600 Triple ultra-performance liquid chromatography time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-TOF-MS/MS) spectrometer was utilized to analyze the extracts of Kushen and Huanglian. A Waters Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column (1.8 µm, 2.1 mm × 50 mm) was used for the chromatographic separation. The LC eluents were acetonitrile (A) and deionized water with 0.1% formic acid (B). The gradient used was as follows: 0–1 min, 5% B; 1–33 min, 5%–95%B; 33–38 min, 95% B; 38–40 min, 95%–5% B; and 40–45 min, 5% B. The injection volume was 2 µl, and the flowrate was 0.3 ml/min.

The AB Sciex 5500 Triple UPLC-TQ-MS/MS was used for the quantitative analysis of Kushen and Huanglian extractions. A total of 10 chemical components were identified and quantified by using AB Sciex 5500 Triple Quad MS platform with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM). A Waters Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column (1.8 µm, 2.1 mm × 50 mm) was used for the chromatographic separation. The LC eluents were acetonitrile (A) and deionized water with 0.1% formic acid (B). The gradient used was as follows: 0–1 min, 15% B; 1–5 min, 15%–50%B; 5–7 min, 50% B; 7–10 min, 50%–15% B; and 10–13 min, 15% B. The injection volume was 5 µl, and the flowrate was 0.3 ml/min.

Standard solutions preparation

Matrine and berberine were accurately weighed and dissolved in methanol to obtain stock solutions at the concentration of 600 μg/ml. Mixed stock standard solution was prepared in methanol, and the concentrations of matrine and berberine in mix stock solution were 600 ng/ml. Then, the mixed standard stock solutions were diluted to seven concentrations for calibration curves. The linear range of matrine is 0.5–600 ng/ml, and berberine is 1–600 ng/ml.

Animal experiment

The protocol for animal experiments was approved by the Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (approval number of the Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation: 202012A010). All animal experiments were carried out under the guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine. CT26.WT cells (1 × 106 cells) were injected into subcutis of five BALB/c nude mice. When the tumor volume reached approximately 100 mm3, the mice were anesthetized, and the tumor tissues were extracted and cut into squares (~1 mm3). A blade was used to scratch the exposed proximal colon serosa of BALB/c nude mice, and tumor tissue fragments (1 mm3) were attached on the damaged proximal colon serosa and covered with tissue adhesive (10 μl). The adessive was allowed to fully solidify for an additional 60 s; thereafter, the peritoneum and skin were sutured with a nylon suture (Cat. No. 220103, obtained from Ningbo Medical Needle Co., Ltd., Ningbo, China).

The mice that had undergone surgery were classified into 11 groups (six for each group): model group; Fufang Banmao Capsules group (positive group); Kushen and Huanglian (1:1) group (1:1; 0.6 g/kg/day); Kushen and Huanglian (1:2) group (1:2; 0.6 g/kg/day); Kushen and Huanglian (1:4) group (1:4; 0.6 g/kg/day); low-matrine (MT-Low) group (15 mg/kg/day); high-matrine (MT-High) group (30 mg/kg/day); low-berberine (BBR-Low) group (30 mg/kg/day); high-berberine (BBR-High) group (200 mg/kg/day); matrine and low-berberine (MT+BBR-Low) group (100 mg/kg/day; ratio of matrine and berberine was 1:2); and matrine and high-berberine (MT+BBR-High) group (200 mg/kg/day; ratio of matrine and berberine was 1:2). Six mice underwent surgery without the use of tissue adhesive (control group). Mice in all groups received the extract in normal saline by gavage.

Mice were treated for 21 days. Thereafter, they were anesthetized for tumor extraction. Tumor tissues were collected, divided into two pieces, and subjected to Western blotting, histology, and immunohistochemistry analyses.

HE staining and immunohistochemistry

For histopathological evaluation, tumor tissue sections were stained with HE solution. Thereafter, the sections were observed under an inverted microscope to identify alterations.

For immunohistochemistry, sections were incubated with a primary antibody against Sirt3 overnight at 4°C. Next, they were washed using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer and incubated with HRP-labeled secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. A DAB kit was used for staining. The analysis of cells that exhibited positivity for Sirt3 was performed using the image analysis software ImageJ. Representative images were captured from six independent samples.

16S Ribosomal RNA gene sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

DNA of intestinal flora was extracted from fecal samples frozen at −80°C (n = 6 per group). The samples were processed and analyzed by Shanghai Majorbiao Bio-Pharm Technology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The V3–V4 hypervariable region of bacterial 16S rRNA was amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with barcode-indexed primers 319F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGTTTCTCATAT-3′). Gel extraction was used for the purification of amplicon. Following the quantification of amplicons, library preparation and sequencing were performed using a TruSeq Nano DNA LT Library Prep Kit. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with over 97% sequence similarity were used for data analyzed, which was performed on the Majorbio Cloud Platform (www.majorbio.com). The diversity of the samples is presented as alpha diversity, while OUT, genus species, and abundance were used to calculate the Chao and Shannon diversity indices. The Chao index denoted microbiota richness in the sample, while the Shannon index represented community diversity. Furthermore, differences in the diversity of intestinal microbiota between groups were determined using principal coordinates analysis (PCOA) and partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA).

Western blot

Radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Cat. No. P0013C, obtained from Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) containing protease and phosphorylase inhibitor cocktails (Cat. No. P1046, obtained from Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) was used to obtain protein from frozen tissues. The determination of protein content was performed by using BCA protein assay kit (Cat. No. P0010, obtained from Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel was used to separate proteins, which were subsequently transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. Next, the membranes were incubated with 5% skimmed milk for 2 h to block non-specific binding and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The next day, membranes were washed with TBST buffer and incubated with secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature. The immunoreactivity was revealed by using an ECL chromogenic substrate, visualized through an imaging system, and quantitatively analyzed by using ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

Values were presented as the means ± standard error of the mean. Student’s t-test and one-way ANOVA were used for statistical analysis, and p-values < 0.05 denoted statistically significant differences. The graph was drawn by using GraphPad Prism 9 and Majorbio Cloud Platform.

Results

Kushen and Huanglian extract prevented colorectal tumorigenesis

The tumor tissue weight, body weight, and the tumor inhibitory rate were calculated. As shown in Figures 1A–C , Kushen–Huanglian extract significantly reduced the ratio of tumor tissue weight to body weight of the model mice. Notably, the extraction at a 1:1 ratio was the most effective among the preparations.

The extract of Kushen and Huanglian did not exert an effect on the body weight of the model mice ( Figure 1D ), suggesting that there was no physical sign of poor condition in any of the experimental mice. According to the results of HE staining, treatment with Kushen and Huanglian effectively reduced the histological damage compared with control ( Figure 1E ). These results revealed that the combination of Kushen and Huanglian at a1:1 ratio showed the best inhibitory effect on colorectal tumorigenesis in mice with cancer versus other preparations.

Qualitative and quantitative analysis of Kushen and Huanglian extract

UPLC-TOF-electrospray ionization-MS/MS (UPLC-TOF-ESI-MS/MS) was used to analyzed the constituents of Kushen and Huanglian extract (1:1 ratio). The total ion chromatogram (TIC) (shown in Figures 1F, G ) displays the major peaks, which were studied using positive and negative ESI modes. A total of 67 compounds were identified according to a previous report ( Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Identified chemical compounds in the extract from Kushen and Huanglian.

| NO | Compound | Molecular formula | t R (min) | Measured molecular weight |

Theoretical molecular weight |

Fragment ion | Tolerance (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N-Methylcytisine | C12H16N2O | 1.4844 | 205.1337 | 205.1335 | 149,108,58 | 0.84 |

| 2 | 9α-Hydroxysophoramine | C15H20N2O2 | 1.4878 | 261.1601 | 261.1598 | 243,177,150 | 1.26 |

| 3 | 7α- Hydroxysophoramine | C15H20N2O2 | 1.4878 | 261.1601 | 261.1598 | 243,177,150 | 1.26 |

| 4 | Anagyrine | C15H20N2O | 1.5625 | 245.1647 | 245.1654 | 148 | 2.80 |

| 5 | Lupanine | C15H24N2O | 1.5642 | 249.1964 | 249.1961 | 166,136 | 1.18 |

| 6 | Matrine | C15H24N2O | 1.6116 | 249.1961 | 249.1961 | 176,148 | 0.00 |

| 7 | Isosophocarpine | C15H22N2O | 2.0622 | 247.1814 | 247.1810 | 179,150,148,136 | 1.51 |

| 8 | Sophocarpine | C15H22N2O | 2.3227 | 247.1809 | 247.1805 | 179,150,136 | 1.69 |

| 9 | 5,6-Dehydrolupanine | C15H22N2O | 2.3227 | 247.1809 | 247.1810 | 176,150,136 | 0.40 |

| 10 | Baptifoline | C13H22N2O2 | 2.5579 | 261.1600 | 261.1598 | 243,164,114 | 0.71 |

| 11 | 9α-Hydroxymatrine | C15H24N2O2 | 4.6859 | 265.1907 | 265.1916 | 247,150,148,112 | 3.00 |

| 12 | Oxymatrine | C15H24N2O2 | 4.7889 | 265.1908 | 265.1911 | 247,205,148 | 1.10 |

| 13 | 5α-Hydroxymatrine | C15H24N2O2 | 4.7889 | 265.1908 | 265.1916 | 247,150,148,112 | 3.00 |

| 14 | 14β-Hydroxymatrine | C15H24N2O2 | 4.7889 | 265.1908 | 265.1916 | 247,150 | 3.00 |

| 15 | Sophoridine | C15H24N2O | 4.8957 | 249.1965 | 249.1961 | 150 | 1.74 |

| 16 | Isomatrine | C15H24N2O | 4.9702 | 249.1968 | 249.1967 | 176,150,148 | 0.21 |

| 17 | Cis-caffeic acid | C9H8O4 | 5.6607 | 181.0495 | 181.0495 | 181,163,135,117,93,65 | 0.10 |

| 18 | Mamanine | C15H22N2O2 | 5.7132 | 263.1756 | 263.1754 | 231 | 0.67 |

| 19 | Oxysophocarpine | C15H22N2O2 | 5.7860 | 263.1758 | 263.1754 | 245,150 | 1.66 |

| 20 | Sophoranol | C15H24N2O2 | 5.8503 | 265.1913 | 265.1916 | 247,205 | 1.20 |

| 21 | 7,11-Dehydromatrine | C15H22N2O | 6.6567 | 247.1809 | 247.1810 | 176,148 | 0.40 |

| 22 | Sophoranol N-oxide | C15H24N2O3 | 8.1026 | 281.1863 | 281.1860 | 263,243,149 | 1.13 |

| 23 | 13-Hydroxycolumbamine | C20H20NO5 | 8.6227 | 354.1328 | 354.1326 | 339,324,296,306,278 | 0.45 |

| 24 | Magnoflorine | C20H24NO4 | 9.0748 | 342.1705 | 342.1705 | 297,265,237 | 0.07 |

| 25 | Norisocorydine | C19H22NO4 | 9.2687 | 328.1547 | 328.1543 | 313,298 | 1.24 |

| 26 | Tetradehydroscoulerine | C19H16NO4 | 9.6160 | 322.1068 | 322.1068 | 307,294,279 | 0.00 |

| 27 | Tetradehydrocheilanthifolinium | C19H16NO4 | 9.6160 | 322.1068 | 322.1068 | 307,294,279 | 0.00 |

| 28 | Lycoranine B | C18H13NO4 | 9.9450 | 308.0917 | 308.0918 | 280,265,250 | 0.40 |

| 29 | N-methlylcorydalmine | C21H26NO4 | 10.5913 | 356.1858 | 356.1857 | 206 | 0.27 |

| 30 | Menisperine | C21H26NO4 | 10.5928 | 356.1859 | 356.1853 | 311, 296 | 1.75 |

| 31 | Demethyleneberberine | C19H18NO4 | 10.8732 | 324.1228 | 324.1231 | 309,294,266;280 | 1.00 |

| 32 | Stecepharine | C21H26NO5 | 10.9242 | 372.1804 | 372.1806 | 222,207,189 | 0.60 |

| 33 | Beberrubine | C19H16NO2 | 11.0160 | 322.1080 | 322.1079 | 322,307,279,250 | 0.38 |

| 34 | Groenlandicine | C19H16NO4 | 11.2061 | 322.1071 | 322.1079 | 307,279 | 2.40 |

| 35 | Thalifendine | C19H16NO4 | 11.2061 | 322.1071 | 322.1072 | 307,294,279 | 0.20 |

| 36 | Columbamine | C20H20NO4 | 11.2668 | 338.1402 | 338.1391 | 322,294;308,280,265 | 3.23 |

| 37 | Noroxyhydrastinine | C10H9NO3 | 11.5192 | 192.0656 | 192.0655 | 192,174,163,192 | 0.37 |

| 38 | 13-Methyljatrorrhizine | C20H18NO5 | 11.5208 | 352.1184 | 352.1184 | 337,322,294,336,308 | 0.13 |

| 39 | Oxyberberine | C20H17NO5 | 11.5446 | 352.1179 | 352.1180 | 337,322,308,294 | 0.20 |

| 40 | 13-Hydroxyberberine | C20H18NO5 | 11.5651 | 352.1182 | 352.1180 | 337,336,308,322,318 | 0.43 |

| 41 | Protopine | C20H19NO5 | 11.8251 | 354.1339 | 354.1336 | 354,339,324,310 | 0.95 |

| 42 | Tetrahydroberberine | C20H21NO4 | 12.2755 | 338.1383 | 338.1387 | 338,323,295 | 1.10 |

| 43 | Coptisine | C19H14NO4 | 12.6173 | 320.0923 | 320.0923 | 318,290,262,249 | 0.00 |

| 44 | Palmatine | C20H18NO5 | 12.9400 | 352.1529 | 352.1535 | 337,322,308,294 | 1.80 |

| 45 | 13-Methylberberine chloride | C21H20NO4 | 13.1289 | 350.1392 | 350.1392 | 147,176 | 0.10 |

| 46 | Worenine | C20H15NO4 | 13.4120 | 334.1082 | 334.1079 | 334,319,304,290,277 | 0.83 |

| 47 | Epiberberine | C20H18NO4 | 13.7474 | 336.1238 | 336.1227 | 320,292 | 3.25 |

| 48 | Berberine | C20H18NO4 | 13.8362 | 336.1238 | 336.1228 | 336,320,290,278 | 2.90 |

| 49 | Linarin | C28H32O14 | 14.0601 | 593.1843 | 593.1838 | 593,447,285 | 0.89 |

| 50 | Daidzein | C15H10O4 | 14.3132 | 255.0663 | 255.0652 | 227 | 4.40 |

| 51 | 13-Methylpalmatine | C22H24NO4 | 14.3165 | 366.1705 | 366.1700 | 351,334,322,308,306 | 1.35 |

| 52 | 13-Methylberberine | C20H17NO4 | 13.8362 | 336.1238 | 336.1230 | 334,322 | 0.40 |

| 53 | Calycosin | C16H12O5 | 14.9714 | 285.0752 | 285.0758 | 270,253,225 | 2.00 |

| 54 | Cytisine | C11H14N2O | 16.1558 | 191.1173 | 191.1179 | 150,148 | 2.90 |

| 55 | Formononetin | C16H12O4 | 18.3435 | 269.0809 | 269.0811 | 254,213,137,118 | 0.70 |

| 56 | 8-Oxocoptisine | C19H13NO5 | 20.5454 | 336.0868 | 336.0867 | 336,308,293,278 | 0.54 |

| 57 | Kuraramine | C12H18N2O2 | 36.4231 | 223.1439 | 223.1441 | 191,162,114 | 0.95 |

| 58 | Anagyrine | C15H20N2O | 1.46215 | 245.1651 | 245.1648 | 148,118,98 | 1.11 |

| 59 | Danshensu | C9H10O5 | 5.9774 | 197.0469 | 197.0458 | 197,179,135,123 | 5.61 |

| 60 | Vanillic acid | C8H8O4 | 6.1849 | 167.0352 | 167.0350 | 167,152,108 | 1.06 |

| 61 | 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid | C7H6O4 | 6.4494 | 153.0198 | 153.0194 | 153,109,91,80 | 2.64 |

| 62 | Phellodendrin | C20H24NO4 | 9.0036 | 340.1557 | 340.1543 | 340,325,310,282,267 | 4.15 |

| 63 | Dehydrocheilanthifoline | C19H15NO4 | 11.5361 | 321.0995 | 321.0995 | 321, 193, 178, 134 | 0.05 |

| 64 | Canadine | C20H21NO4 | 11.2668 | 338.1402 | 338.1386 | 338,323,308,293,264 | 4.71 |

| 65 | 3-O-Feruloylquinic acid | C17H20O9 | 13.1451 | 367.1026 | 367.1029 | 191,173 | 0.80 |

| 66 | 5-O-Feruloylquinic acid | C17H20O9 | 13.1451 | 367.1026 | 367.1029 | 191 | 0.80 |

| 67 | 4-O-Feruloylquinic acid | C17H20O9 | 13.1451 | 367.1026 | 367.1029 | 191,173 | 0.80 |

UPLC-triple quadruple-MS/MS (UPLC-TQ-MS/MS) was used to quantitatively analyze matrine and berberine in the Kushen and Huanglian extract. The peaks of matrine and berberine are shown in Figures 1H–L . The levels of matrine and berberine were calculated based on their calibration curves. The results are shown in Table 2 . The levels of matrine and berberine were 129 µg/g (0.129‰ of the herb) and 232 µg/g (0.232‰ of the herb). The ratio was approximately 1:2, which was used in the subsequent experiments.

Table 2.

The contents of matrine and berberine in the extract from Kushen and Huanglian.

| Compound | t R (min) | Regression equation | R2 | Linear rang (ng/ml) | Content (µg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matrine | 1.29 | Y = 34340*X − 86061 | 0.999 | 0.5–600 | 129.47 ± 9.82 |

| Berberine | 6.83 | Y = 97034*X + 2117352 | 0.999 | 1–600 | 232.87 ± 89.94 |

Matrine and berberine prevented colorectal tumorigenesis

The tumor weights of mice in the MT-low group, BBR-low group, and MT+BBR-low group mice were decreased compared with that of mice in the control group; however, the difference was not statistically significant. In contrast, the tumor weight of MT-high group, BBR-high group, and MT+BBR-high group was remarkably declined ( Figures 2A, B ). The inhibitory rate in each group is displayed in Figure 2C . Of note, differences in the body weight between groups were not statistically significant ( Figure 2D ). Nevertheless, treatment with matrine and berberine reduced the weight of tumor tissue in the model mice.

Figure 2.

Matrine and berberine prevent colorectal tumorigenesis in an orthotopic xenograft model of colorectal cancer. (A) Representative image of tumor tissue obtained from model mice. (B) Tumor weight/body weight of mice (n = 6, ### p < 0.001 compared with Control group, *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 compared with Model group). (C) Inhibitory rate of matrine, berberine, and positive drug on colorectal cancer in model mice (n = 6). (D) Body weight of mice (n = 6). (E) Representative image of HE-stained tumor tissue from model mice. Scale bar: 50 μm. Red arrows indicate nuclear pyknosis.

Subsequently, pathological changes in tumor tissues were detected by HE staining. In the model group, the morphology of tumor tissue was obviously atypical and dense and was characterized by irregular arrangements. Compared with the model group, treatment with matrine and berberine (particularly at high dosage) effectively reduced the histological damage. As shown in Figure 2E , the morphological alterations demonstrated that, compared with the model group, positive drug, and treatment with matrine and berberine significantly reduced tumor cell density in the tumors. These results revealed that matrine and berberine could inhibit colorectal tumorigenesis in model mice.

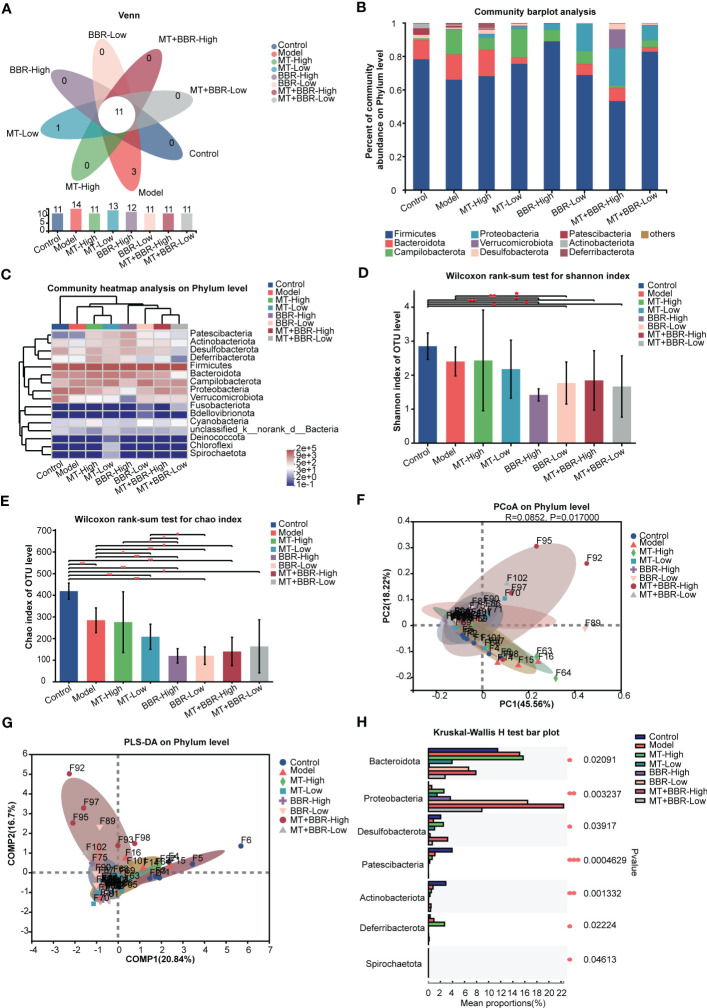

Matrine and berberine improved the intestinal microbiota structure

Thereafter, we sought to characterize the effects of treatment with matrine and berberine on the composition of intestinal microbiome through analysis of bacterial 16S rRNA compositions. The Venn diagram indicated that the number of OTUs was higher at the phylum and genus levels in the model group compared with the control or matrine and berberine treatment groups ( Figures 3A , 4A ). Higher Shannon index values represented higher species diversity in the sample. The results demonstrated that treatment with matrine and berberine significantly reduced the Shannon and Chao indices in the model mice ( Figures 3D, E , 4D, E ). Moreover, the abundances of genera in each group were visualized on a heatmap, displaying trends at the phylum and genus levels. In addition, differences in the composition of the intestinal microbiome at the phylum and genus levels were recorded in the individual treatment groups ( Figures 3C , 4C ). The abundance diversity histogram of the top 10 phylum structure demonstrated that the Bacteroidota and Campilobacterota (i.e., the predominant flora in the samples) presented a difference between the model and matrine and berberine treatment groups ( Figure 3B ). Further study demonstrated that treatment with matrine and berberine reduced the abundance of Helicobacter, Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group, Candidatus_Arthromitus, norank_f_Lachnospiraceae, Rikenella, Odoribacter, Streptococcus, norank_f_Ruminococcaceae, and Anaerotruncus at the genus level ( Figure 4B ).

Figure 3.

Matrine and berberine regulated the species diversity of intestinal microbiota in mice at the phylum level. (A) Venn diagram summarizing the numbers of common and unique phyla. (B) Relative abundance of the top 10 phyla classified as colorectal microbiota constituents. (C) Abundance of gut microbiota species at the phylum level in each group represented by clustering heatmap. (D, E) Alpha diversity of the gut microflora in mouse fecal at the phylum level, represented by the Shannon (D) and Chao (E) indices. (F, G) Matrine- and berberine-mediated impact on bacterial composition in model mice at the phylum level, represented by PCoA (F) and PLS-DA (G) analysis (H) Bar plot of compositional differences in the gut microbiome between groups at the phylum level, calculated by the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. n =6, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

Matrine and berberine regulated the species diversity of intestinal microbiota in mice at the genus level. (A) Venn diagram summarizing the numbers of common and unique genera. (B) Relative abundance of the top genera classified as colorectal microbiota constituents. (C) Abundance of gut microbiota species in each group at the genus level, represented by clustering heatmap. (D, E) Alpha diversity of the gut microflora in mouse fecal samples at the genus level, represented by Shannon (D) and Chao (E) indices. (F, G) Matrine- and berberine-mediated impact on bacterial composition in model mice at the genus level, represented by PCoA (F) and PLS-DA (G) analysis. (H) Bar plot of compositional differences in the gut microbiome between groups at the genus level, calculated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. n =6, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.001.

These results revealed that the species richness of intestinal microbiota in the orthotopic xenograft colorectal cancer model mice was observably downregulated following the administration of matrine and berberine.

Notably, different groups exhibited distinct bacterial composition ( Figures 3F, G , 4F, G ). Alterations at the phylum and genus levels were also assessed. The results revealed statistically significant differences in seven phyla (i.e., Bacteroidota, Proteobacteria, Desulfobacterota, Patescibacteria, Actinobacteriota, Deferribacterota, and Spirochaetota) and 10 genera (i.e., Staphylococcus, Lactococcus, Esherichia-Shigella, norank_f_Muribaculaceae, Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group, unclassified_f_Lachnospiraceae, norank_f_Lachnospiraceae, Enterobacter, Alistipes, and Rikenella) ( Figures 3H , 4H ). The abundance of Proteobacteria in the matrine- and berberine-treated groups was higher than that recorded in the model group. In contrast, the abundance of the other six phyla was lower than that in the model group.

Matrine and berberine decreased c-MYC expression, inhibited RAS signaling pathway, and increased Sirt3 expression

The Western blot analysis demonstrated that treatment with matrine and berberine decreased the expression of transcription factor c-MYC in vivo ( Figures 5A, B ).

Figure 5.

Matrine and berberine decreased c-MYC expression, inhibited RAS signaling, and increased SIRT3 expression in model mice. (A–F) Representative Western blotting with quantification results for proteins present in tumor tissue obtained from mice (n = 6, ***p < 0.001). (G, H) Representative immunohistochemistry images with quantification results for Sirt3 in tumor tissue obtained from mice (n = 6, ***p < 0.001). Scale bar: 100 μm. *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

The efficacy of matrine and berberine to regulate the RAS/MEK/ERK signaling pathway was also inquired in vivo. The levels of RAS, MEK, p-MEK, ERK, and p-ERK in tumor tissues were detected through Western blot. The levels of RAS, p-MEK, and p-ERK in the neoplasm tissue obtained from model mice were significantly reduced after treatment with matrine and berberine ( Figures 5A, C–F ). Furthermore, our results suggested that treatment with matrine and berberine upregulated the expression of Sirt3 in tumorous tissue ( Figures 5A, F–H ).

Discussion

Oral preparation with TCM has a complex composition. The active components of such preparations were absorbed and distributed through the gastrointestinal tract to reach the site of action. Before being absorbed, the compounds could perturb the composition of the gastrointestinal flora (15, 20).

In TCM, the combination of Kushen and Huanglian is used for the treatment of intestinal disease. The major active compounds from Kushen and Huanglian also reduce the inflammation action and exhibit anti-colorectal cancer efficacy (49–54). Different drug ratios can affect the effectiveness of the herbs. According to the record of the Pujifang, the proportion of Kushen and Huanglian was 1:2. In this study, we evaluated Kushen and Huanglian at 1:1, 1:2, and 1:4 ratios to determine the combination with the best anti-tumor effect. We found that the combination at a 1:1 ratio exhibited the most potent anti-colorectal cancer effect. The chemical constituents of this preparation were detected using of UPLC-TOF-ESI-MS/MS. A total of 67 compounds were identified according to literature data. Further analysis showed that the contents of matrine and berberine were 129.47 and 232.87 µg/g, respectively. The ratio of matrine and berberine was approximately 1:2. Thus, we used matrine and berberine at this ratio to evaluate their effect against colorectal cancer. According to the literature (55–57), 15 and 30 mg/kg matrine and 100 and 200 mg/kg berberine were used to mice. In the combination of two compounds group, the total dosage of two compounds were 100 and 200 mg/kg, with the ratio of matrine to berberine of 1:2. We showed that the combination of matrine and berberine exerted a better anti-colorectal cancer effect in the orthotopic xenograft colorectal model mice than monotherapy.

The gut microbiota is a key component of the colorectal cancer microenvironment. Intestinal microecology disorders are strongly associated with the development and progression of colorectal cancer (58). In our animal experiments, the mice were treated by oral gavage. Before the drug was absorbed into the blood in the gastrointestinal tract, the drug may affect the composition of the gastrointestinal flora before it is absorbed. Therefore, we analyzed the mouse fecal gut flora by 16S rRNA sequencing. Treatment with matrine and berberine treatment significantly reduced the diversity of intestinal microbiota in tumor-bearing mice. According to the literatures, Proteobacteria abnormal expansion is usually considered as a signature of dysbiosis in gut microbiota. Irinotecan is widely used in the treatment of colorectal cancer; it can also increase the level of Proteobacteria and cause intestinal mucositis with diarrhea (59). The combined matrine and berberine increased the abundance of Proteobacteria, suggesting that they might be causing intestinal mucositis with diarrhea, which should be noted when using the combined matrine and berberine in the treatment of colorectal cancer. The abundance of Bacteroidota and Campilobacterota was positive related to colorectal cancer (13, 60). Furthermore, our experiment showed that matrine and berberine decreased the abundance of Bacteroidota and Campilobacterota. According to the previous research, Helicobacter pylori (an important member of Campilobacterota) could encode CagA gene to activate the RAS/MEK/ERK signaling pathway (61). RAS/MEK/ERK is one of the most dysregulated signaling pathway in cancer. Extensive research has been conducted on the development of inhibitors targeting the RAS/RAF-MEK-ERK/MAPK signaling pathway (25). Due to its active compounds, the Huanglian and Kushen drug pair exerts an anti-cancer effect by regulating the RAS/ERK/MEK-related signaling pathway (62–64). Thus, we detected the effect of matrine and berberine on the expression of proteins linked to the RAS/MEK/ERK signaling axis in tumor tissues obtained from mice. Matrine and berberine significantly inhibited the RAS/ERK/MEK signaling pathway by decreasing the phosphorylation levels of MEK and ERK and expression of RAS. Furthermore, matrine and berberine decreased the level of c-MYC protein, which could improve acetylation-dependent deactivation of SDHA by activating SKP2-mediated degradation of Sirt3 deacetylase and tumorigenesis. Moreover, our results demonstrated that matrine and berberine improved the expression of Sirt3, which could inhibit growth of tumor cells (65). Therefore, matrine and berberine could inhibit MYC-induced tumorigenesis by regulating degradation of Sirt3 deacetylase. These findings suggested that matrine and berberine exert its anti-colorectal cancer effect by regulating the RAS/MEK/ERK-c-MYC-Sirt3 signaling axis.

Collectively, the results indicated that matrine and berberine may act against colorectal cancer by regulating the intestinal microecological and the signaling pathway related to cell proliferation ( Figure 6 ). The regulating effect of matrine and berberine on RAS/MEK/ERK-c-MYC-Sirt3 signaling axis may be attributed to their influence on the composition of intestinal microbiota. The present research study may provide a reference for the use of matrine and berberine in the prevention and treatment of colorectal cancer. However, the mechanisms underlying these have not been investigated far. Hence, further studies are warranted to clarify the role and mechanism of intestinal flora in anti-colorectal cancer effects.

Figure 6.

Mechanism underlying the anti-colorectal cancer effect of matrine and berberine.

Conclusion

The combination of Kushen and Huanglian at a1:1 ratio exerted the best anti-colorectal cancer effect among the combinations examined in this study. The chemical compounds contained in the Kushen and Huanglian extract were identified and evaluated. Additionally, the combination of matrine and berberine induced an almost equivalent anti-colorectal cancer effect to that noted after treatment with the drug pair. In addition, the combination exerted a better effect on colorectal cancer than monotherapy. The beneficial action of this treatment might depend on the improvement of the intestinal microbiota structure and regulation of the RAS/MEK/ERK-c-MYC-Sirt3 signaling pathway.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, PRJNA866510.

Ethics statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Author contributions

DS, HC and JG conceived and designed the experiment. ZC, YD and QY collaborated in the experiments, analyzed the data, interpreted the results, and developed the manuscript. QL, LL, CY, YL and JT collaborated in the experiment and analyzed the data. MF, CX and WS supervised the work and proofread the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82074318, 81930117, and 82004310), Natural Science Research of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (19KJA310007), and Qinglan Project of Jiangsu Province, College Students’ Innovative Entrepreneurial Training Plan Program (202010315023Z and 202010315025), a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Brody H. Colorectal cancer. Nature (2015) 521:S1. doi: 10.1038/521S1a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin (2021) 71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schmitt M, Greten FR. The inflammatory pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Immunol (2021) 21:653–67. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00534-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yang J, Wei H, Zhou Y, Szeto CH, Li C, Lin Y, et al. High-fat diet promotes colorectal tumorigenesis through modulating gut microbiota and metabolites. Gastroenterology (2022) 162:135–149 e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.08.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tilg H, Adolph TE, Gerner RR, Moschen AR. The intestinal microbiota in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell (2018) 33:954–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lucas C, Barnich N, Nguyen HTT. Microbiota, inflammation and colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci (2017) 18:1310. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cheng Y, Ling Z, Li L. The intestinal microbiota and colorectal cancer. Front Immunol (2020) 11:615056. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.615056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen F, Dai X, Zhou CC, Li KX, Zhang YJ, Lou XY, et al. Integrated analysis of the faecal metagenome and serum metabolome reveals the role of gut microbiome-associated metabolites in the detection of colorectal cancer and adenoma. Gut (2022) 71:1315–25. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Si H, Yang Q, Hu H, Ding C, Wang H, Lin X. Colorectal cancer occurrence and treatment based on changes in intestinal flora. Semin Cancer Biol (2021) 70:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clay SL, Fonseca-Pereira D, Garrett WS. Colorectal cancer: the facts in the case of the microbiota. J Clin Invest (2022) 132:e155101. doi: 10.1172/JCI155101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kordahi MC, Stanaway IB, Avril M, Chac D, Blanc MP, Ross B, et al. Genomic and functional characterization of a mucosal symbiont involved in early-stage colorectal cancer. Cell Host Microbe (2021) 29:1589–1598.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen KJ, Chen YL, Ueng SH, Hwang TL, Kuo LM, Hsieh PW. Neutrophil elastase inhibitor (mph-966) improves intestinal mucosal damage and gut microbiota in a mouse model of 5-fluorouracil-induced intestinal mucositis. BioMed Pharmacother (2021) 134:111152. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Flemer B, Lynch DB, Brown JM, Jeffery IB, Ryan FJ, Claesson MJ, et al. Tumour-associated and non-tumour-associated microbiota in colorectal cancer. Gut (2017) 66:633–43. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lin C, Li B, Tu C, Chen X, Guo M. Correlations between intestinal microbiota and clinical characteristics in colorectal adenoma/carcinoma. BioMed Res Int (2022) 2022:3140070. doi: 10.1155/2022/3140070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 15. Luo S, Wen R, Wang Q, Zhao Z, Nong F, Fu Y, et al. Rhubarb peony decoction ameliorates ulcerative colitis in mice by regulating gut microbiota to restoring th17/treg balance. J Ethnopharmacol (2019) 231:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Png CW, Chua YK, Law JH, Zhang Y, Tan KK. Alterations in co-abundant bacteriome in colorectal cancer and its persistence after surgery: a pilot study. Sci Rep (2022) 12:9829. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-14203-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shao S, Jia R, Zhao L, Zhang Y, Guan Y, Wen H, et al. Xiao-chai-hu-tang ameliorates tumor growth in cancer comorbid depressive symptoms via modulating gut microbiota-mediated tlr4/myd88/nf-kappab signaling pathway. Phytomedicine (2021) 88:153606. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sui H, Zhang L, Gu K, Chai N, Ji Q, Zhou L, et al. YYFZBJS ameliorates colorectal cancer progression in apc(min/+) mice by remodeling gut microbiota and inhibiting regulatory t-cell generation. Cell Commun Signal (2020) 18:113. doi: 10.1186/s12964-020-00596-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zackular JP, Baxter NT, Iverson KD, Sadler WD, Petrosino JF, Chen GY, et al. The gut microbiome modulates colon tumorigenesis. mBio (2013) 4:e00692–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00692-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang HY, Tian JX, Lian FM, Li M, Liu WK, Zhen Z, et al. Therapeutic mechanisms of traditional chinese medicine to improve metabolic diseases via the gut microbiota. BioMed Pharmacother (2021) 133:110857. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sun H, Tang C, Chung SH, Ye XQ, Makusheva Y, Han W, et al. Blocking dcir mitigates colitis and prevents colorectal tumors by enhancing the GM-CSF-STAT5 pathway. Cell Rep (2022) 40:111158. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Malik A, Sharma D, Malireddi RKS, Guy CS, Chang TC, Olsen SR, et al. SYK-CARD9 signaling axis promotes gut fungi-mediated inflammasome activation to restrict colitis and colon cancer. Immunity (2018) 49:515–530.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.08.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen L, Chen M-Y, Shao L, Zhang W, Rao T, Zhou H-H, et al. Panax notoginseng saponins prevent colitis-associated colorectal cancer development: the role of gut microbiota. Chin J Natural Med (2020) 18:500–7. doi: 10.1016/s1875-5364(20)30060-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Simanshu DK, Nissley DV, McCormick F. Ras proteins and their regulators in human disease. Cell (2017) 170:17–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Santarpia L, Lippman SM, El-Naggar AK. Targeting the MAPK-RAS-RAF signaling pathway in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Target (2012) 16:103–19. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.645805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dang CV. Myc on the path to cancer. Cell (2012) 149:22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Elbadawy M, Usui T, Yamawaki H, Sasaki K. Emerging roles of c-myc in cancer stem cell-related signaling and resistance to cancer chemotherapy: a potential therapeutic target against colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci (2019) 20:2340. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marmol I, Sanchez-de-Diego C, Pradilla Dieste A, Cerrada E, Rodriguez Yoldi MJ. Colorectal carcinoma: a general overview and future perspectives in colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci (2017) 18:197. doi: 10.3390/ijms18010197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li ST, Huang D, Shen S, Cai Y, Xing S, Wu G, et al. Myc-mediated sdha acetylation triggers epigenetic regulation of gene expression and tumorigenesis. Nat Metab (2020) 2:256–69. doi: 10.1038/s42255-020-0179-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang W, Sang S, Peng C, Li GQ, Ou L, Feng Z, et al. Network pharmacology and transcriptomic sequencing analyses reveal the molecular mechanism of sanguisorba officinalis against colorectal cancer. Front Oncol (2022) 12:807718. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.807718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yin FT, Zhou XH, Kang SY, Li XH, Li J, Ullah I, et al. Prediction of the mechanism of dachengqi decoction treating colorectal cancer based on the analysis method of " into serum components -action target-key pathway". J Ethnopharmacol (2022) 293:115286. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu H, Huang Y, Yang L, Su K, Tian S, Chen X, et al. Effects of jianpi lishi jiedu granules on colorectal adenoma patients after endoscopic treatment: study protocol for a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Trials (2022) 23:345. doi: 10.1186/s13063-022-06236-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li R, Zhou J, Wu X, Li H, Pu Y, Liu N, et al. Jianpi jiedu recipe inhibits colorectal cancer liver metastasis via regulating itgbl1-rich extracellular vesicles mediated activation of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Phytomedicine (2022) 100:154082. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cao Y, Lu K, Xia Y, Wang Y, Wang A, Zhao Y. Danshensu attenuated epithelial-mesenchymal transformation and chemoresistance of colon cancer cells induced by platelets. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) (2022) 27:160. doi: 10.31083/j.fbl2705160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang X, Liu W, Zhang S, Wang J, Yang X, Wang R, et al. Wei-tong-xin ameliorates functional dyspepsia via inactivating tlr4/myd88 by regulating gut microbial structure and metabolites. Phytomedicine (2022) 102:154180. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu P, Zhou X, Zhang H, Wang R, Wu X, Jian W, et al. Danggui-shaoyao-san attenuates cognitive impairment via the microbiota-gut-brain axis with regulation of lipid metabolism in scopolamine-induced amnesia. Front Immunol (2022) 13:796542. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.796542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu L, Lu Y, Xu C, Chen H, Wang X, Wang Y, et al. The modulation of chaihu shugan formula on microbiota composition in the simulator of the human intestinal microbial ecosystem technology platform and its influence on gut barrier and intestinal immunity in caco-2/thp1-blue cell co-culture model. Front Pharmacol (2022) 13:820543. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.820543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bian Y, Chen X, Cao H, Xie D, Zhu M, Yuan N, et al. A correlational study of weifuchun and its clinical effect on intestinal flora in precancerous lesions of gastric cancer. Chin Med (2021) 16:120. doi: 10.1186/s13020-021-00529-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hu HF, Wang Z, Tang WL, Fu XM, Kong XJ, Qiu YK, et al. Effects of sophora flavescens aiton and the absorbed bioactive metabolite matrine individually and in combination with 5-fluorouracil on proliferation and apoptosis of gastric cancer cells in nude mice. Front Pharmacol (2022) 13:1047507. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1047507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kim SY, Park C, Kim MY, Ji SY, Hwangbo H, Lee H, et al. ROS-mediated anti-tumor effect of coptidis rhizoma against human hepatocellular carcinoma Hep3b cells and xenografts. Int J Mol Sci (2021) 22:4797. doi: 10.3390/ijms22094797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang Y, Chen X, Li J, Hu S, Wang R, Bai X. Salt-assisted dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction for enhancing the concentration of matrine alkaloids in traditional chinese medicine and its preparations. J Sep Sci (2018) 41:3590–7. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201701504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xie L, Feng S, Zhang X, Zhao W, Feng J, Ma C, et al. Biological response profiling reveals the functional differences of main alkaloids in rhizoma coptidis. Molecules (2021) 26:7389. doi: 10.3390/molecules26237389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ren H, Zhang S, Ma H, Wang Y, Liu D, Wang X, et al. Matrine reduces the proliferation and invasion of colorectal cancer cells via reducing the activity of p38 signaling pathway. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) (2014) 46:1049–55. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmu101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ren H, Wang Y, Guo Y, Wang M, Ma X, Li W, et al. Matrine impedes colorectal cancer proliferation and migration by downregulating endoplasmic reticulum lipid raft associated protein 1 expression. Bioengineered (2022) 13:9780–91. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2022.2060777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cheng Y, Yu C, Li W, He Y, Bao Y. Matrine inhibits proliferation, invasion, and migration and induces apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells via miR-10b/PTEN pathway. Cancer Biother Radiopharm (2020) 37:871–81. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2020.3800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yan S, Chang J, Hao X, Liu J, Tan X, Geng Z, et al. Berberine regulates short-chain fatty acid metabolism and alleviates the colitis-associated colorectal tumorigenesis through remodeling intestinal flora. Phytomedicine (2022) 102:154217. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nie Q, Peng WW, Wang Y, Zhong L, Zhang X, Zeng L. Beta-catenin correlates with the progression of colon cancers and berberine inhibits the proliferation of colon cancer cells by regulating the beta-catenin signaling pathway. Gene (2022) 818:146207. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2022.146207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chen H, Ye C, Cai B, Zhang F, Wang X, Zhang J, et al. Berberine inhibits intestinal carcinogenesis by suppressing intestinal pro-inflammatory genes and oncogenic factors through modulating gut microbiota. BMC Cancer (2022) 22:566. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09635-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li P, Lei J, Hu G, Chen X, Liu Z, Yang J. Matrine mediates inflammatory response via gut microbiota in tnbs-induced murine colitis. Front Physiol (2019) 10:28. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yan X, Lu QG, Zeng L, Li XH, Liu Y, Du XF, et al. Synergistic protection of astragalus polysaccharides and matrine against ulcerative colitis and associated lung injury in rats. World J Gastroenterol (2020) 26:55–69. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i1.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhou BH, Yang JY, Ding HY, Chen QP, Tian EJ, Wang HW. Anticoccidial effect of toltrazuril and radix sophorae flavescentis combination: reduced inflammation and promoted mucosal immunity. Vet Parasitol (2021) 296:109477. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2021.109477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhang D, Jiang L, Wang M, Jin M, Zhang X, Liu D, et al. Berberine inhibits intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction in colon caused by peritoneal dialysis fluid by improving cell migration. J Ethnopharmacol (2021) 264:113206. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wang Y, Liu J, Huang Z, Li Y, Liang Y, Luo C, et al. Coptisine ameliorates dss-induced ulcerative colitis via improving intestinal barrier dysfunction and suppressing inflammatory response. Eur J Pharmacol (2021) 896:173912. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.173912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Huang C, Sun Y, Liao SR, Chen ZX, Lin HF, Shen WZ. Suppression of berberine and probiotics (in vitro and in vivo) on the growth of colon cancer with modulation of gut microbiota and butyrate production. Front Microbiol (2022) 13:869931. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.869931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Luo Z, Li Z, Liang Z, Wang L, He G, Wang D, et al. Berberine increases stromal production of wnt molecules and activates lgr5(+) stem cells to promote epithelial restitution in experimental colitis. BMC Biol (2022) 20:287. doi: 10.1186/s12915-022-01492-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wu C, Xu Z, Gai R, Huang K. Matrine ameliorates spontaneously developed colitis in interleukin-10-deficient mice. Int Immunopharmacol (2016) 36:256–62. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.04.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang Y, Wang S, Li Y, Xiao Z, Hu Z, Zhang J. Sophocarpine and matrine inhibit the production of TNF-alpha and IL-6 in murine macrophages and prevent cachexia-related symptoms induced by colon26 adenocarcinoma in mice. Int Immunopharmacol (2008) 8:1767–72. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Li Y, Li ZX, Xie CY, Fan J, Lv J, Xu XJ, et al. Gegen qinlian decoction enhances immunity and protects intestinal barrier function in colorectal cancer patients via gut microbiota. World J Gastroenterol (2020) 26:7633–51. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i48.7633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wang Y, Sun L, Chen S, Guo S, Yue T, Hou Q, et al. The administration of escherichia coli nissle 1917 ameliorates irinotecan-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction and gut microbial dysbiosis in mice. Life Sci (2019) 231:116529. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. He Z, Gharaibeh RZ, Newsome RC, Pope JL, Dougherty MW, Tomkovich S, et al. Campylobacter jejuni promotes colorectal tumorigenesis through the action of cytolethal distending toxin. Gut (2019) 68:289–300. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Alipour M. Molecular mechanism of helicobacter pylori-induced gastric cancer. J Gastrointest Cancer (2021) 52:23–30. doi: 10.1007/s12029-020-00518-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Huang T, Xiao Y, Yi L, Li L, Wang M, Tian C, et al. Coptisine from rhizoma coptidis suppresses HCT-116 cells-related tumor growth in vitro and in vivo . Sci Rep (2017) 7:38524. doi: 10.1038/srep38524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Li L, Wang X, Sharvan R, Gao J, Qu S. Berberine could inhibit thyroid carcinoma cells by inducing mitochondrial apoptosis, G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and suppressing migration via PI3K-AKT and mapk signaling pathways. BioMed Pharmacother (2017) 95:1225–31. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zhao Z, Zhang D, Wu F, Tu J, Song J, Xu M, et al. Sophoridine suppresses lenvatinib-resistant hepatocellular carcinoma growth by inhibiting RAS/MEK/ERK axis via decreasing vegfr2 expression. J Cell Mol Med (2021) 25:549–60. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.16108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Liu H, Li S, Liu X, Chen Y, Deng H. Sirt3 overexpression inhibits growth of kidney tumor cells and enhances mitochondrial biogenesis. J Proteome Res (2018) 17:3143–52. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, PRJNA866510.