Abstract

Cancer immunity is mediated by a delicate orchestration between the innate and adaptive immune system both systemically and within the tumor microenvironment. Although several adaptive immunity molecular targets have been proven clinically efficacious, stand-alone innate immunity targeting agents have not been successful in the clinic. Here, we report a nanoparticle optimized for systemic administration that combines immune agonists for TLR9, STING, and RIG-I with a melanoma-specific peptide to induce antitumor immunity. These immune agonistic nanoparticles (iaNPs) significantly enhance the activation of antigen-presenting cells to orchestrate the development and response of melanoma-sensitized T-cells. iaNP treatment not only suppressed tumor growth in an orthotopic solid tumor model, but also significantly reduced tumor burden in a metastatic animal model. This combination biomaterial-based approach to coordinate innate and adaptive anticancer immunity provides further insights into the benefits of stimulating multiple activation pathways to promote tumor regression, while also offering an important platform to effectively and safely deliver combination immunotherapies for cancer.

Keywords: polymeric nanoparticles, cancer immunotherapy, innate immunity, immunology

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Cancer progression is highly dependent on the interactions and cross-talk between immune and tumor cells.1 Tumor cells employ multiple strategies to evade anticancer immunity, such as immune editing, secretion of immune inhibitory cytokines, and downregulation of key surface proteins.2,3 To address these evasion and immune suppression mechanisms, the FDA has approved several therapies such as anti-Programmed Death Protein (PD-1), anti-Cytotoxic T-cell Ligand (CTLA4) monoclonal antibodies, and anti-CD19 chimeric antigen-receptor (CAR-T) cells that augment existing adaptive anticancer immunity. In addition, promising innate immunity therapeutic targets, on the other hand, including indoleamine-pyrrole 2,3-dioxygenase inhibitors (IDOi), stimulator of interferon (IFN) gene (STING) agonists, and toll-like-receptor (TLR) agonistic molecules, have yet to garner FDA approval despite elaborate or sometimes complex combinatorial therapeutic strategies.4 Short half-life and difficulty in targeted delivery to specific immune cell subsets within the tumor microenvironment represent one major shortcoming of these small molecule agonists that limited their therapeutic potential. Just as nanoparticles (NPs) have played a transformative role in augmenting the therapeutic index of chemotherapeutics, they may further expand the therapeutic utility of well-studied immunotherapy targets.

Cytokines play a critical role in stimulating the innate immune system in response to both foreign pathogens and cancer antigens alike, and they do so by augmenting antigen presentation, modulation of immune checkpoints, and upregulating costimulation of adaptive immune response.5–8 IFNs are a particularly important class of cytokines that are effective in generating antitumor activity through stimulating both the innate and adaptive immune responses.9,10 IFNs influence the innate immune response by upregulating major histocompatibility complexes (MHC)I and MHCII and promoting antigen presentation.11

One strategy to enhance IFN production is to stimulate native pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) using conserved ligands, which are frequently derived from microbial molecules, termed pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Recent clinical trials have shown promise to boost the immune system using PAMPs, which include single-stranded DNA, double-stranded RNA, and lipopolysaccharides.12 Distinct molecular patterns have been shown to activate different PRRs, including TLR and STING binding and downstream activation and retinoic acid inducible gene 1 (RIG-I).13

CpG-ODN 1826 has been studied as a TLR9 agonist to treat cardiac dysfunction and cancer.14–16 CpG ODNs have shown early success in phase I clinical trials as a promising modulator of the innate immune response and increased patient survival in melanoma cancer and is already an FDA-approved adjuvant.15,17–20 TLR9 recognizes unmethylated CpG dinucleotides, which are found in viral and bacterial DNA. In the cell’s resting state, TLR9 is found in the endoplasmic reticulum, but in the presence of CpG ODN, TLR9 colocalizes with CpG ODN in the endosomal compartment, resulting in binding and pathway activation. Upon binding to CpG ODN, TLR9 stimulation coordinates multiple elements of the immune system. This leads to stimulation of the Th1 pathway, stimulation of plasmocytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) to secrete type I interferons, and increasing stimulation of B-cells and pDCs, which lead to T-cell engagement (Figure 1). The overall TLR9 pathway activation can lead to tumor cell death directly through production of factors such as IFNα.

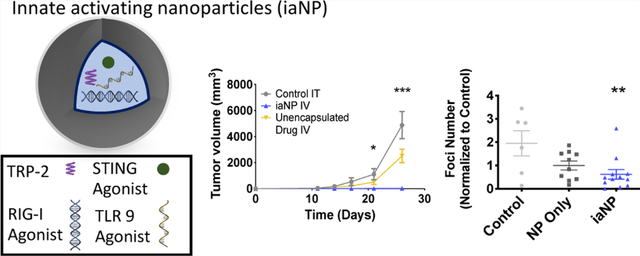

Figure 1.

Overview of potential antitumor pathways activated with iaNPs. iaNPs were loaded with STING, RIG-I, and TLR9 agonists along with cancer cell-specific peptide, TRP-2. (1) TLR9 agonist-activated B and pDCs leading to type I interferon production and activation of APCs. (2) RIG-I and STING agonists promoting type I interferon production and activation of APCs. (3) Activated APCs presenting the TRP-2 peptide on the surface leading to sensitizing of T-cells to generate TRP-2-specific T-cells. (4) Mature CD4 and CD8 T-cells traffic to the tumor-cell microenvironment (5) TRP-2-specific T-cells targeting cancer cells that express the TRP-2 protein on the surface leading to killing of cancer cells (6) tumor death due to TRP-2-specific T-cells and directly through activation of macrophages to lead to antitumor efficacy. (7) Antigen release occurs as tumor cells die, promoting further APC activation and tumor cell death.

STING agonists such as 3′3 cGAMP are potent antitumor modulators because of production of interferons.21–24 STING is a transmembrane protein that is found on many APCs such as macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs). The binding of 3′3 cGAMP with STING leads to signaling events, resulting in an increase in IFNβ expression.

Similar to the STING pathway, RIG-I activation with an agonist such as 5′pppdsRNA induces the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as Type 1 IFN.25,26 RIG-I is a cytosolic protein that recognizes viral RNA evoking the innate immune response. 5′pppdsRNA is an agonist to RIG-I, and once bound to the RIG-I receptor, RIG-I undergoes an ATP-dependent conformational change exposing the caspase recruitment domain (CARD); upon exposure to the CARD domain, this leads to downstream signaling and production of type I interferons (Figure 1). Although the RIG-I receptor targets RNA while the STING receptor targets DNA, there is cross-talk between these pathways, which can lead to amplification of the innate immune system.27

These three pathways enhance interferon production, antigen-presenting cell (APC), and activation and downstream antitumor efficacy.28,29 However, administration of PAMPs in clinical studies either required high dosages or was limited to local intratumoral injections to reach therapeutic efficacy as a result of the molecules’ short half-life and limited systemic exposure.30 For example, an ongoing clinical trial with the STING agonist MIW815 study was shown to have a half-life of 10–23 min31 We sought to develop a systemic delivery solution that can effectively deliver PAMPs systemically to the innate immune system, as this would extend their utility beyond locally accessible tumors. We hypothesized that this approach would improve pharmacokinetics of the fragile adjuvant cargo and would result in more potent and clinically significant antitumor activity.

Various nanobased carrier formulations have shown promising efficacy to deliver proteins and small molecules including polymer NPs, liposomes, and hydrogels.32–36 We sought to build a NP that orchestrates the complex cross-talk between innate and adaptive immune cells within the context of the cancer immunity cycle through enhanced cytokine signaling and improved antigen presentation (Figure 1). Immune agonistic NPs (iaNPs) composed of a biodegradable polymer loaded with a potent combination of a TLR9 agonist, RIG-I agonist, STING agonist, and melanoma specific peptide (TRP-2 or gp100) were designed to be systemically administered to have utility beyond locally accessible tumors. We hypothesize that iaNPs can activate and stimulate immune cells to secrete proinflammatory cytokines to subsequently elicit antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell antitumor activity (Figure 1).37–39

As a result, the development of a polymer nanoscale system loaded with a melanoma-specific adjuvant cocktail can improve cancer immunotherapy formulations by protecting the therapeutics from degradation, increasing the systemic half-life, and efficiently internalizing into the target cells.29,40,41 Immune agonists have shorter half-life, which impacts both the efficacy and utility of these therapeutics. Additionally, these immune agonists are limited to local delivery, which is practically challenging and restricts the types of tumors that can be treated. The short half-life of these adjuvants can be improved with coencapsulation into a NP platform to enable systemic delivery and increase antitumor responses. We studied the effects of colocalizing a TLR9 agonist, RIG-I agonist, STING agonist, and peptide antigen in a NP carrier system designed to activate DCs and promote antigen presentation. We investigated and characterized the response of APCs in the presence of iaNPs in vitro and in vivo and characterized the antitumor efficacy response in orthotopic and metastatic tumor models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

NP Fabrication.

NPs composed of carboxylic acidterminated poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) (PolySciTech) were fabricated by water in oil in water double emulsion. 1200 mg of 75:25 lactic/glycotic (L/G) PLGA was dissolved in ethyl acetate (Sigma) at 50 mg/mL. CpG ODN 1826 (TLR9 agonist, 1000 μg, Trilink), 5′ppp-dsRNA (RIG-I agonist, 200 μg, InvivoGen), 3′3-cGAMP (STING agonist, 1800 μg, InvivoGen), and a melanoma peptide (TRP-2 or gp100, 50 mg, Sigma) were solubilized in aqueous limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) reagent water. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, Mw ~ 31,000 g/mol, Sigma) at 3% (w/v) was added at a 1:2 ratio of polymer drug solution to PVA. The mixture was probe-sonicated on ice at 7–8 W for five cycles of 5 s on and 10 s off to form NPs. The NP solution was diluted 10-fold with 0.3% (w/v) PVA in water and slowly stirred for 2 h to evaporate residual ethyl acetate. The NPs were purified first to remove large aggregates by centrifuging at 500 rpm for 10 min. Then, to remove small NPs, ethyl acetate, and unencapsulated drug, the NP solution was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. The unencapsulated drug and ethyl acetate in the supernatant were removed, while the pellet containing the encapsulated NPs was resuspended in 1% PVA. The NPs were lyophilized for 48 h at −40 °C at 70 mTorr after flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen and subsequently stored at −80 °C. Prior to in vitro and in vivo works, the NPs were resuspended in 1% PVA in sterile phosphate buffer saline (PBS) to prevent shearinduced aggregation upon intravenous injection. NPs were visualized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with a Carl Zeiss Ultra 55 FE-SEM at 3 kV using a secondary electron detector and by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS.

Total Drug Payload.

Drug loading was determined by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) (Agilent AdvanceBio. 150 mm × 4.6 mm, 2.7 μm particle, 300 Å pore) combined with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) at 260 nm. The mobile phase was 0.05 M potassium phosphate buffer with 0.25 M potassium chloride, pH 6.8, which was run at a flow rate of 0.35 mL/min over 20 min. Adjuvant loading was determined over time until the total payload was released out of the NPs in PBS. Retention times for the adjuvants were 6.5 min for ODN 1826, 5.9 min for 5′ppp-dsRNA, 7.5 min for 3′3-cGAMP, and 11.9 min for the TRP-2 peptide.

Cell Culture.

Cell culture was performed with complete media containing RPMI 1640 with 10% calf serum (heat inactivated, Sigma), 1% penicillin streptomycin (Sigma), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma), 1% HEPES (Sigma), 1× nonessential amino acids (Sigma), and 50 μM of 2-beta mercaptoethanol (Sigma). B16F10 melanoma cells (ATCC) were cultured in a T-75 flask until 70% confluency prior to injection. For intravenous (IV) melanoma administration, the cells were removed from the flask, washed with ice-cold Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) (Thermo), and passed through a 40 μm mesh filter prior to mouse tail vein injection of 2.5 × 106 cells/mouse.42 Cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

J774.1 macrophages (ATCC) confocal experiments were performed with varying NP concentrations (1 ng/mL, 0.1 mg/mL, and 1 mg/mL) with 6% w/w of the fluorescent polymer cyano-polyphenylene vinylene (CN-PPV) (Sigma) incorporated to track the NPs. To induce baseline phagocytic activity, macrophages were activated overnight with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 ng/mL, Sigma) and cultured with NPs for 3 h prior to washing and imaging.

Mouse Studies.

The mouse studies were performed in compliance with the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines with the approved Protocol AN110246. Wild-type C57BL/6 mice aged 6–8 weeks purchased from The Jackson Laboratory.

In Vitro NP Association and Activation Experiments.

After fresh spleen was excised from the mouse, the tissue was mashed through a 70 μm filter with PBS. Splenocytes were centrifuged down at 1500 rpm for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended into RBC lysis (0.83% ammonium chloride in 0.01 M Tris buffer) for 5 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed twice with complete media. Cells (1 × 106) were placed in 96-well plates.

For NP association experiments, cells were cultured with NPs with a CN-PPV fluorescent polymer incorporated for tracking for 48 h. Excess NPs were washed thrice with PBS (Sigma) with 4% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma). Cells were then stained for flow cytometry.

For APC activation experiments, cells were treated with varying concentrations (1 ng/mL, 0.1 mg/mL, and 1 mg/mL) of iaNPs, NP-only, and control no treatment in cell culture media. After 48 h in culture, the cells were stained with antibodies and run on a BD Fortessa flow cytometer.

In Vitro Cell Stimulation.

The Protein Transport Inhibitor (GolgiPlug, BD) at 1 μL/mL was added to single-cell suspensions. Cells were then stimulated with 10 μg/mL of TRP-2 in culture for 12 h. The cells were stained for flow cytometry.

In Vivo DC Activation.

In vivo DC activation was measured 5 days after one dose of iaNP, NP-only, or control no treatment. The mice were sacrificed, and single-cell cultures of the spleen, lymph node, and lungs were generated as described above and stained for flow cytometry.

Subcutaneous In Vivo Melanoma Model.

Female C57BL/6 mice aged 6–8 weeks from Jackson Laboratory were inoculated with 1 × 105 B16F10 cells in PBS buffer. Mice were treated with saline, NP-only, iaNP, and free unencapsulated drug 3 days after tumor inoculation every 3 days for a total of four doses. Intratumoral treatment was injected in four separate spots in the tumor for a total of 100 μL. For intravenous treatment, 200 μL of treatment was injected via the tail vein. A caliper was used twice a week for tumor measurements, and tumor volume was measured using the formula: volume (mm3) = (l × w2)/2. Mice were euthanized once tumor volumes exceeded 2000 mm3. Mice in the NP-only group reached the limit at day 20 and were euthanized prior to the last time point. Additionally, mice in the control group reached 2000 mm3 shortly after the day 20 time point.

Intravenous In Vivo Melanoma Model.

B16.F10 melanoma cells were added via IV to C57BL/6 mice. After 4 days, treatment was administered PVA-only (control), NPonly, or iaNP IV to the melanoma-treated mice. Treatment was administered three times every 3 days. Each dose consisted of 10 mg of NPs with 8.5 μg of 3′3-cGAMP, 5.8 μg of ODN 1826, 0.33 mg of TRP-2 peptide, and 0.50 μg of 5′ppp-dsRNA. Three days after the last treatment, the mice were sacrificed and the spleen, lymph nodes, and lungs were harvested. The number of lung foci and weight was measured upon removal prior to digestion. The spleen and lymph nodes were passed through a 100 μm filter. RBC lysis was performed on splenocytes. Lung was finely minced and digested in media containing collagenase XI (2 mg/mL, Sigma Aldrich), DNAse (0.1 mg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich), and hyaluronidase (0.5 mg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich) at 200 rpm and 37 °C for 45 min. The lung suspension was diluted 10-fold with media, vortexed to resuspend the cell pellet, and passed through a 100 μm filter. After forming single-cell suspensions, the lymph node, splenocytes, and lung cells were plated in a 96-well plate.

Flow Cytometry Analysis and Panels.

For flow cytometry experiments, single cells were plated in 96-well plates at 1–2 × 106.The cells were washed twice with PBS + 2% FBS coupled with centrifugation at 650g for 2 min. The cells were resuspended in 50 μL of the surface antibody mixture and incubated at 4 °C for 30 min. After 30 min, the surface antibody was washed twice with PBS with 2% FBS. Cells were resuspended in 50 μL of Fix/Perm (eBioscience, FOXP3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer kit) (1:4) for 30 min, enabling fixation and permeabilization of cells for intracellular staining. Wells were washed twice with Perm Buffer (eBioscience, FOXP3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer kit) at 650g for 4 min. The cells were then incubated with intracellular antibody stain for 30 min at 4 °C. Cells were washed twice with PBS 2% FBS, resuspended, and stored in PBS + 2% FBS at 4 °C. Flow cytometry was performed on Fortessa X-20 (BD Biosciences), and data analysis was performed with FlowJo v10.5.2.

For cellular association experiments, 1–2 × 106 cells were stained with anti-CD3-FITC (17A2, eBioscience), anti-CD11c-PECy7 (N418, eBioscience), anti-CD11b-BV650 (M1/70, BD Bioscience), anti-CD45-Alexa700 (30-F11, eBioscience), anti-CD64-BV786 (X54–5/7.1, BD Bioscience), anti-B220-APCCy7, anti-CD19-PE (HIB19, BD Bioscience), and Ghost Violet 510 viability dye (Tonbo). NPs with the CN-PPV-incorporated polymer were analyzed in the PerCP channel.

For in vitro and in vivo APC activation studies, DCs and macrophages were investigated. For DC studies, 1–2 × 106 cells were stained with anti-CD3e-PerCP (145–2C11, BD Bioscience), anti-CD11c-PE-Cy7 (HL3, BD Bioscience), anti-CD11b-BV650 (M1/70, BD Bioscience), anti-CD45-Alexa700 (30-F11, eBioscience), anti-MHCII-e450 (M5/114.15.2, eBioscience), anti-Ly6C-BV605, anti-CD86-APC, anti-B220-APC-Cy7, anti-CD207-PE, and Ghost Violet 510 viability dye (Tonbo).

For macrophage studies, 1–2 × 106 cells were stained with anti-B220-FITC (RA3–6B2, BD Bioscience), anti-CD19-FITC (1D3, eBioscience), anti-CD3-FITC (17A2, eBioscience), anti-CD11c-PECy7 (N418, eBioscience), anti-CD11b-BV650 (M1/70, BD Bioscience), anti-CD45-Alexa700 (30-F11, eBioscience), anti-MHCII-e450 (M5/114.15.2, eBioscience), anti-CD64-BV786, anti-CD24-APC eFluor-780 (M1/69, eBioscience), and Ghost Violet 510 viability dye (Tonbo). Cells were then stained intracellularly with anti-IL10-APC (JES5–16E3, BD Bioscience) and anti-IL12-PE (C15.6, BD Bioscience).

For T-cell activation studies, 1–2 × 106 cells were stained with anti-CD45.2-FITC (104, eBioscience), anti-CD8-BV605 (53–6.7, BD Bioscience), anti-CD45-Alexa700 (30-F11, eBioscience), anti-CD4-BV650 (RM4–5, BD Bioscience), anti-CD3e-BV711 (145–2C, BD Bioscience), and Ghost Violet 510 viability dye (Tonbo). Intracellular staining was then performed with anti-Ki67-PECy7 (B56, BD Bioscience), anti-IFNγ-PE (XMG1.2, eBioscience), anti-TNFa-PerCP710 (MP6-XT22, eBioscience), anti-FOXP3-e450 (FJK-16s, eBioscience), and anti CTLA4-APC (UC10–4B9, eBioscience).

Statistics.

Flow plot data analysis was performed with Flow Jo 10.5.2. One-way ANOVA with the Dunnett multiple comparison was used to determine significance between each group in GraphPad Prism. All plots show mean ± standard deviation (SD), where * represents p < 0.05, ** represents p < 0.01, and *** represents p < 0.001.

RESULTS

Fabrication and Characterization of Innate-Activating NPs.

We hypothesized that systemic delivery of key immune activators was possible with the use of a polymer NP as a vehicle. To develop iaNPs, we used 75:25 L/G ratio PLGA for its biocompatibility and biodegradation properties to coencapsulate CpG ODN 1826 (TLR9 agonist), 5′ppp-dsRNA (RIG-I agonist), 3′3-cGAMP (STING agonist), and a melanoma peptide (TRP-2 or gp100).43–45 NP size was characterized by SEM and DLS (Supporting Information 1). The NPs were 258.1 ± 60 nm with a polydispersity index (PDI) of 0.2 in a hydrated form by DLS. The surface charge was measured with an average zeta potential of −21.7 ± 0.058 mV. The carboxylic acid-terminated polymer was utilized to prevent aggregation and reduce shear resistance upon injection to prevent embolisms upon IV injection. The lyophilized NPs were resuspended without aggregation in a 1% PVA solution. Loading of adjuvants in the NPs was determined by SEC: 69.1% of CpG ODN1826, 29.8% 5′ppp-dsRNA, 56.5% 3′3-cGAMP, and 80% melanoma peptide TRP-2.

iaNP Interaction with APCs.

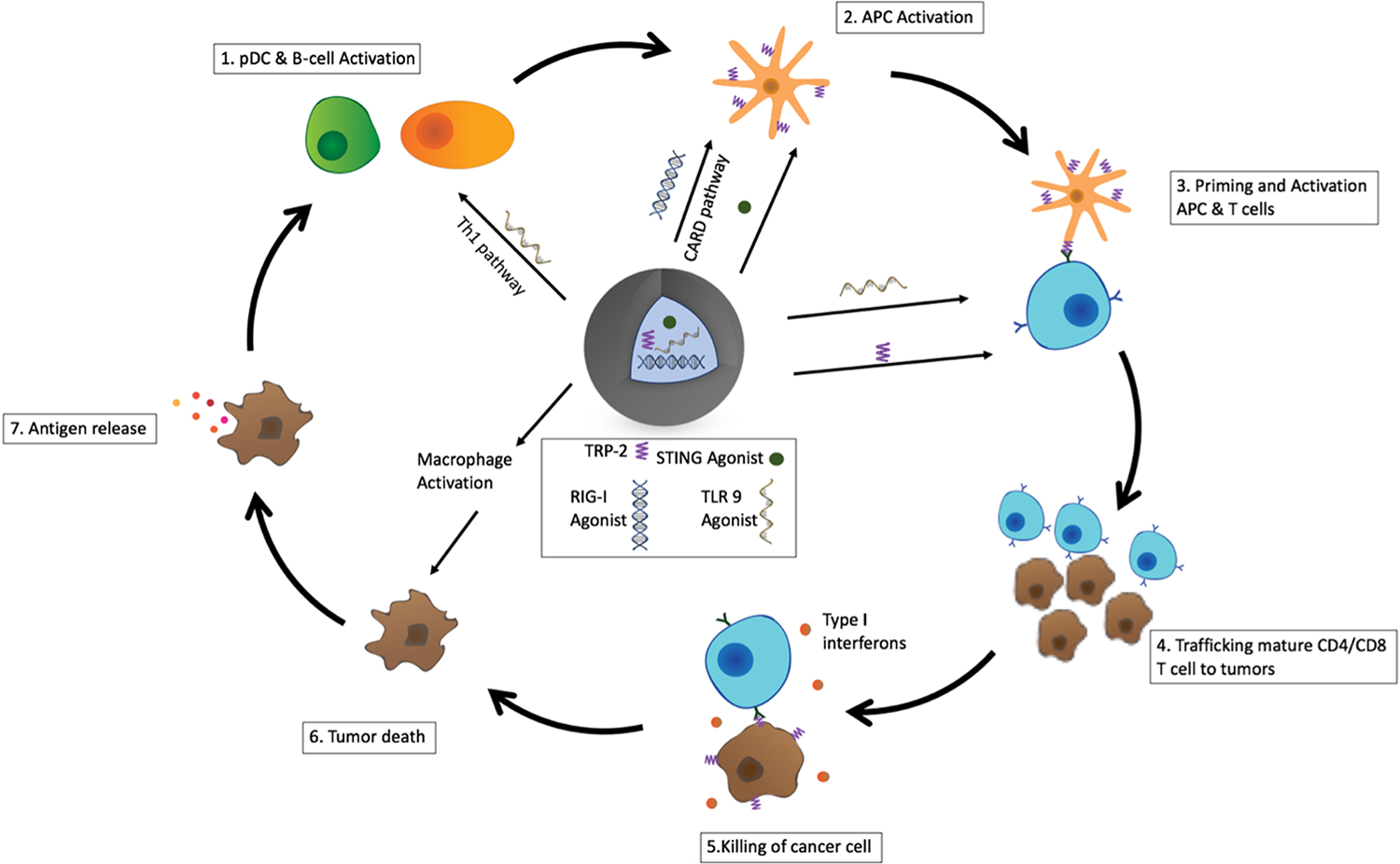

To study the mechanism of antitumor immunity orchestrated by iaNPs, we investigated the internalization and association of iaNPs. The cellular association of iaNPs as well as downstream cellular activation were characterized. Mouse macrophages (J774.1) were cultured with fluorescently labeled iaNPs and imaged with confocal microscopy (Figure 2A). To investigate cellular association by flow cytometry, iaNPs were cultured with mouse splenocytes. Increasing the concentrations of NPs resulted in increased NP positive cells by flow cytometry (Figure 2B). NP association in myeloid cells was observed in 9.35% of classical DCs (cDC), 20.43% of pDCs, and 32.16% of macrophages with minimal (<0.5%) association in lymphoid cells: T and B-cells (Figure 2C). From these results, we showed a selective uptake of iaNPs and targeted codelivery of adjuvants and tumor antigen peptides with these APC populations.

Figure 2.

NP association by APCs ex vivo. The confocal image of (A) J774.1 cells after 3 h incubation with fluorescently labeled NPs ex vivo. Scale bar: 5 μm. Nucleus DAPI stain: purple, actin phalloidin stain: blue, and NP stain: yellow. (B) Concentration-dependent NP association into splenocytes by flow cytometry. Data represent mean ± s.d., N = 4. (C) NP association with APCs after 3 h of NP incubation determined by flow cytometry. Control wells have no NPs present. Data represent mean ± s.d., N = 4, and two-way ANOVA, where *** denotes p < 0.001 w.r.t. control.

iaNP Activation of APCs In Vitro with Splenocytes.

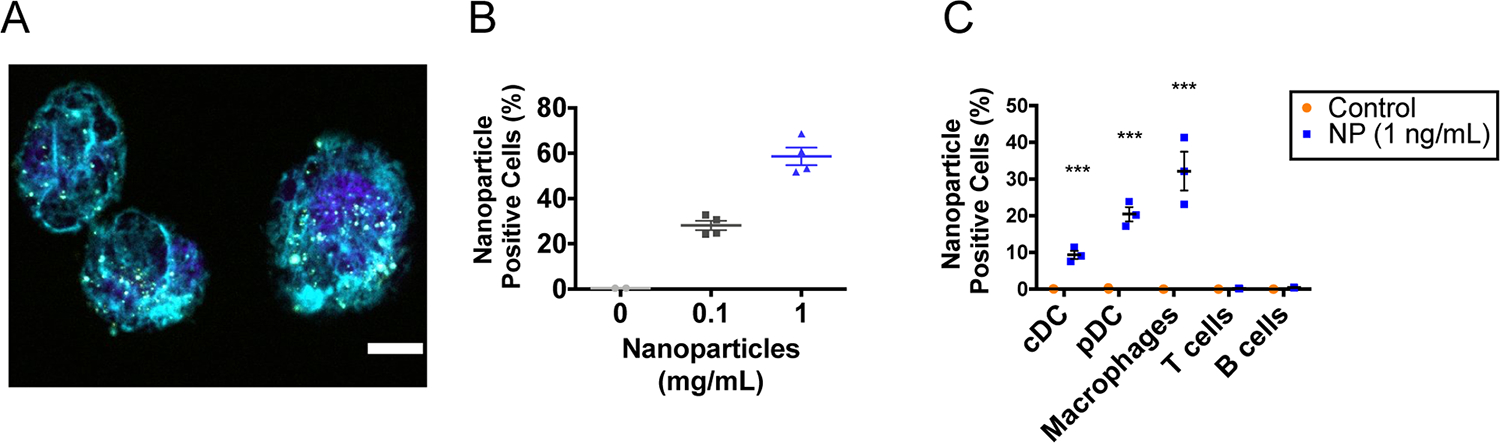

Then, we investigated the activation of DCs following iaNP association. CD86, a marker of DC activation, is a protein expressed on the surface of APCs that interacts with the CD28 ligand on T-cells, which is crucial in activation of antigen-specific T-cells.46 iaNP treatment significantly enhanced DC activation compared to control and NP-only groups, indicating that DC activation resulted from the coencapsulated agonists in iaNPs (Figure 3A). To further understand the subset of the activated DCs in the immune response, we focused on DC populations implicated in antitumor immunity. cDC1 is invoked in CD8 memory T-cell activation and CD8 cytotoxic T-cell priming, and Th1 induction, while cDC2 is responsible for Th2 and Th17 induction.59 pDCs principally secrete type I IFN, which can increase NK cell and CD8 + T-cell cytotoxicity, stimulate maturation of DCs, and promote proinflammatory activation of macrophages.60 Both cDC1- and cDC2-activated cells increased with iaNP treatment, while there was a larger, twofold increase in cDC2 compared to control (Figure 3B,C). Although pDC population is rare among mouse splenocytes, the iaNPs significantly increased the number of activated pDCs compared to control and NPonly groups (Figure 3D). As B-cells play a role in the adaptive immune system and when activated lead to antibody production, we further studied the effects of iaNPs on this cell population. iaNP treatment led to fourfold increase in activated B-cells, while NP-only did not alter the activated B-cell population (Figure 3E). When investigating the effects of iaNPs on secretion of cytokines by macrophages, IL-10 amounts were statistically unchanged, but there was a significant increase in IL-12, suggesting M1, proinflammatory, over M2, anti-inflammatory, and macrophage phenotypes (Figure 3F,G). iaNPs were selectively delivered to APCs and induced activation of cDC, pDC, and macrophages that are integral in antitumor immunity.

Figure 3.

iaNPs are preferentially internalized by APCs ex vivo. (A–D) Quantification of DC populations in splenocytes (A) MHCII+CD11c+CD86+ DCs, (B) CD11c+CD8+CD11b−CD86+ conventional DCs 1 (cDC1), (C) CD11c+CD8−CD11b+CD86+ conventional DCs 2 (cDC2), (D) CD11c+CD8−CD11b−B220+MHCII+CD86+ pDCs, and (E) quantification of CD3−B220+CD86 B-cell population of all CD45+ cells in splenocytes. (F,G) IL-10 and IL-12 expressing macrophages in splenocytes by intracellular cytokine staining. Each data point in the panels consists of one animal. One-way ANOVA, where * denotes p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Systemic Delivery of NP-Encapsulated Innate Agonists Induces Antitumor Responses in the Syngeneic Mouse Model.

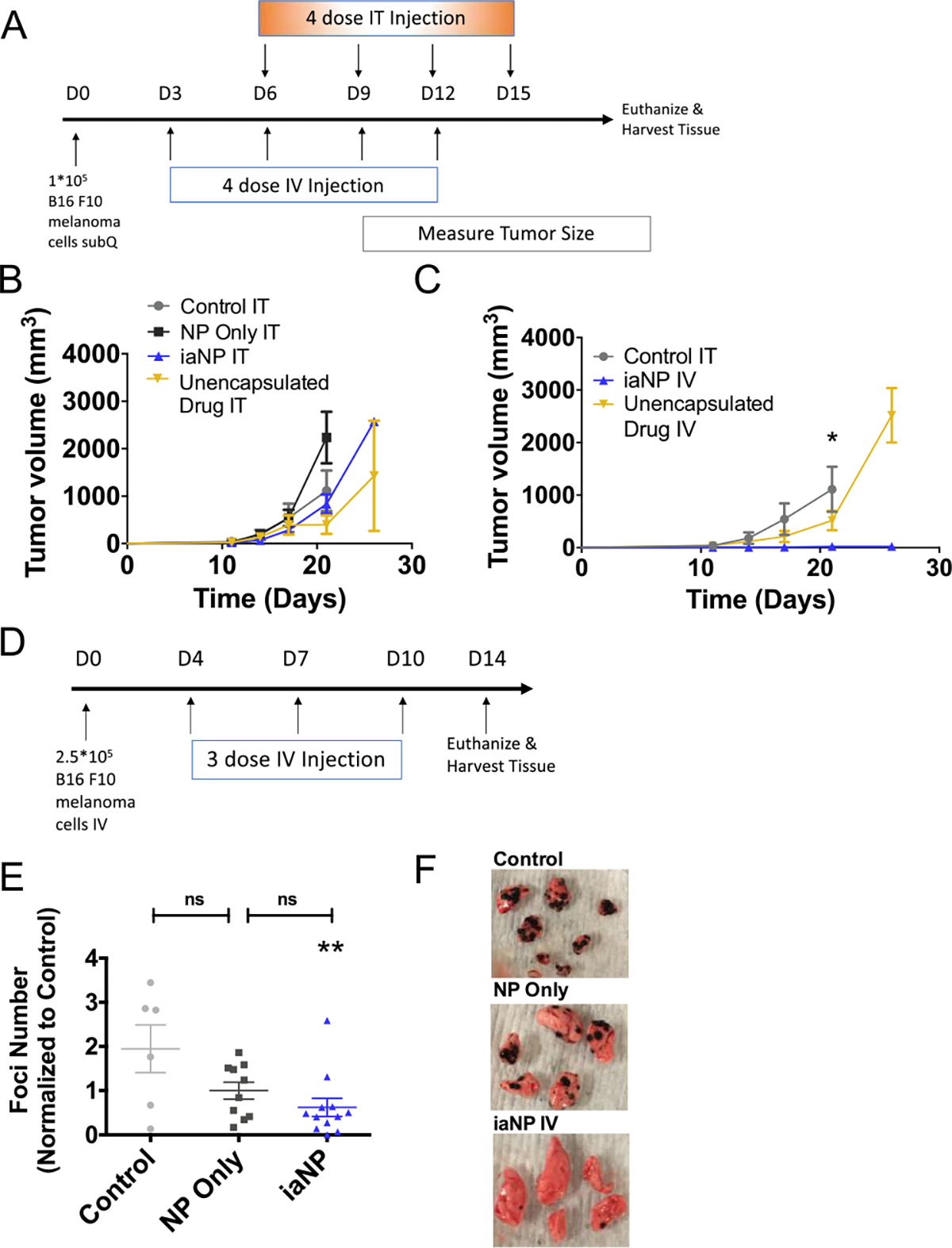

To understand the therapeutic effects of iaNPs, we investigate more diverse tumor types with intratumoral (IT) and intravenous (IV) administration. Melanoma cells were first subcutaneously (subQ) injected into the mouse flank. After the tumors were palpable, the mice were treated with PBS control, NP (NP)-only vehicle, iaNP, or unencapsulated drug and the tumor volume was monitored (Figure 4A). The tumor size grew to over 4000 mm3 at day 26 with the PBS vehicle and NP-only when treated with IT injection (Figure 4B). The tumor volume decreased with treatment below 2000 mm3 with the unencapsulated drug and iaNP, demonstrating superiority in the active dose compared to vehicle or PBS (Figure 4B). We hypothesized that IV administration of NPs would increase half-life, increasing efficacy. IV administration of iaNPs was performed 3 days after tumor inoculation prior to palpable tumor. Statistically significant differences were observed between all three groups with decreased tumor volume with iaNPs to 24.1 mm3 compared to unencapsulated drugs with an average tumor volume of 2187 mm3 at day 26 (Figure 4C). Taken together, the data demonstrate that iaNPs can not only provide the benefit of systemic delivery but also have profound antitumor properties.

Figure 4.

Systemic and intratumoral administration of iaNPs reduces tumor volume. The subcutaneous melanoma model (A) timeline (days) for B16F10 melanoma cell inoculation, treatments, and sacrifice for tissue harvest. (B,C) Tumor volume of measured subcutaneous tumor over time (days). (B) Treatment with intratumoral administration of vehicle PBS, NP-only, unencapsulated drug combo, and iaNPs. (C) Treatment with intravenous administration of unencapsulated drug combo and iaNPs and with intratumoral injection of vehicle PBS. The metastatic melanoma model in the lung tissue (D) timeline (days) for B16F10 melanoma cell intravenous inoculation, systemic treatments, and sacrifice for tissue harvest and (E) number of lung foci. Data are normalized to the control and presented as mean ± s.d n ≥ 6. Each data point represents one animal. (F) Representative lung from WT mouse with melanoma foci with no treatment (control, PVA-only), NP-only, and iaNPs. One-way ANOVA; Mean ± SD; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 w.r.t. control.

iaNP Reduce Tumor Burden in the Lung Metastasis Model.

Next, we hypothesized that systemic delivery of therapeutic iaNPs may have antitumor efficacy in a metastatic tumor model. We modeled a metastatic tumor by injecting B16F10 cells intravenously through the tail vein. Tumor-inoculated mice were treated 4 days later with iaNPs containing a RIG-I agonist, STING agonist, TLR9 agonist, and TRP-2 and subsequently every 3 days for a total of three doses by the IV route (Figure 4D). Therapeutic efficacy was assessed by harvesting lung tissue to quantify tumor foci (Figure 4F). Remarkably, there was significant reduction in metastatic melanoma foci in the lungs with less than 40 foci observed in iaNP-treated animals when compared to saline-treated animals that had an average of 116 foci (Figure 4F). A modest decrease in tumor burden resulted from NP-only treatment, while iaNP treatment significantly decreased tumor burden compared to control (Figure 4E). As a result, the combination of NPs with the drug combo led to an improvement in the metastatic melanoma present in the lung tissue with 25% of the animals with less than five nodules (Figure 4E,F).

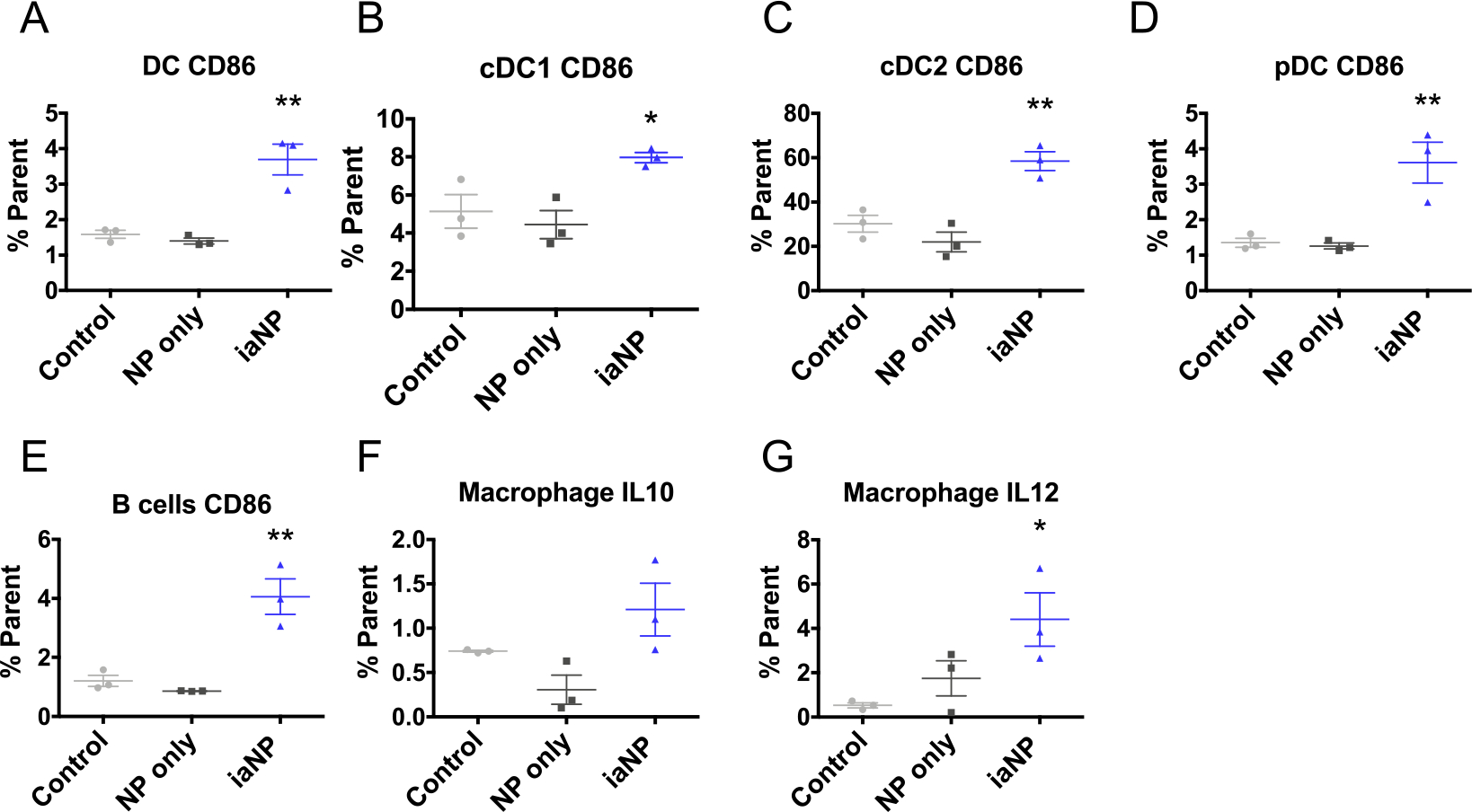

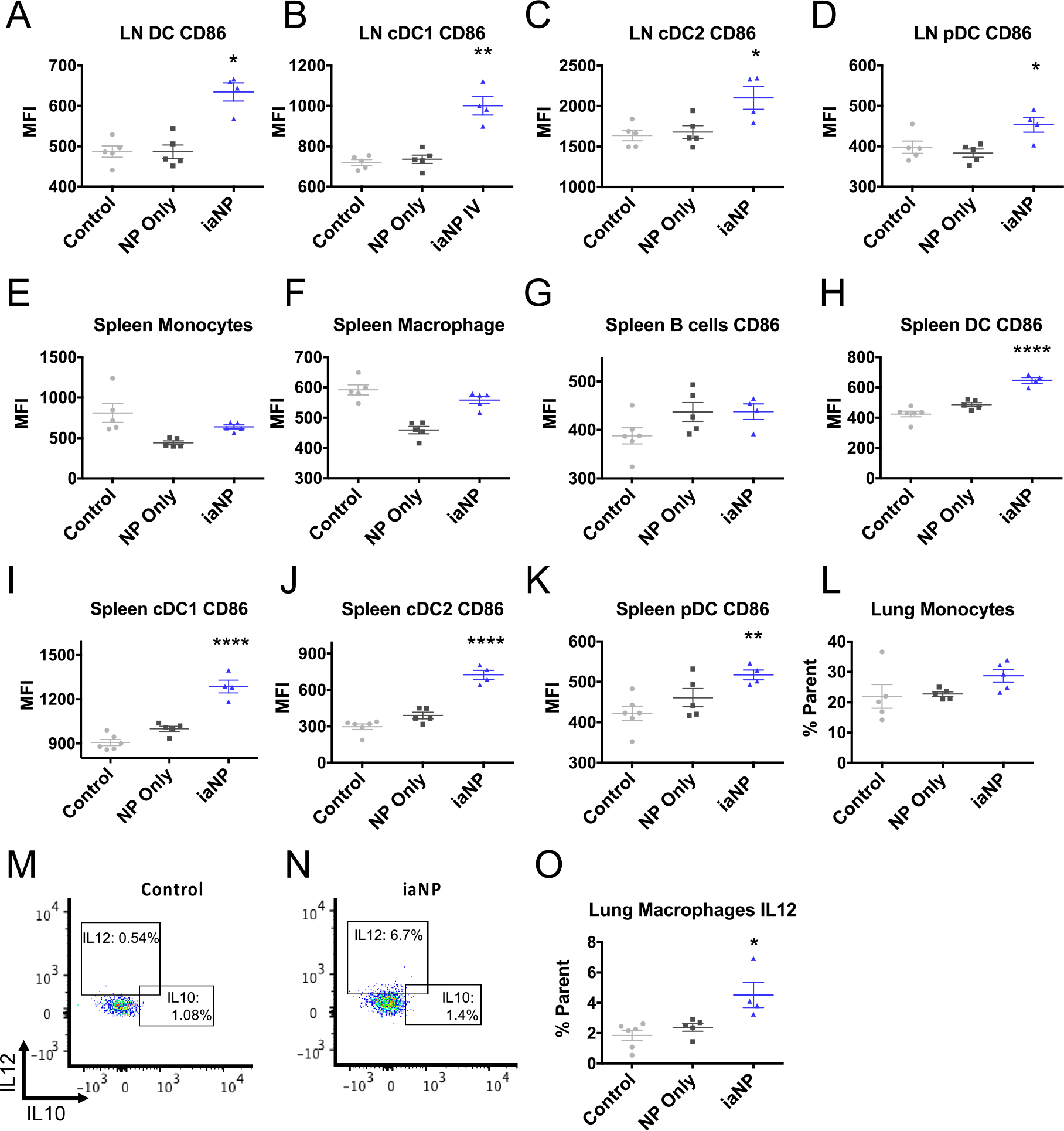

iaNP Activation of APCs in the Lymph Node and Spleen In Vivo.

We then further investigated how iaNPs would modulate immunity in an in vivo system. The mice were administered iaNP, NP-only, or PVA-only control by IV tail vein injections. Here, iaNPs increased APCs in the target tissue, lymph node, along with the spleen, while no change was seen in DCs or macrophages in the lung tissue (Figure 5). In the lymph node, we saw a broad activation of DC subpopulations (Figure 5A). iaNPs increased the activated cDC1 population by 1.4-fold with no change in the NP-only treatment compared to control (Figure 5B). cDC2 and pDC counts were also significantly increased only in the iaNP treatment group compared to NP-only and control (Figure 5C,D). In the lymph nodes, which are a main site of immunomodulatory activity, iaNPs functioned to enhance activation of APCs.

Figure 5.

Systemically administered iaNP selectively induces DC activation in primary lymphoid tissues. Control for these studies was PVA-only. (A–D) Lymph node APC CD86 expression in (A) CD8+CD11b−CD86+ DCs, (B) CD8+CD11b−CD86+ conventional DCs 1, (C) CD8−CD11b+CD86+ conventional DCs 2, (D) CD8−CD11b−B220+MHCII+CD86+ pDCs. Activation of monocytes and macrophages in splenocytes, (E) CD11b+CD64+Ly6c+ monocytes, (F) CD11b+CD64+Ly6c− CD64+ macrophages, (G) spleen CD3−B220+CD86+ B-cells (H–K) APC activation in splenocyte cell populations, (H) MHCII+CD11c+CD86+ DCs, (I) CD8+CD11b−CD86+ cDC1 cells, (J) CD8−CD11b+CD86+ cDC2 cells, (K), CD8−CD11b−B220+MHCII+CD86+ pDC cells, and (L) CD11b+CD64+Ly6c+ monocytes in lung cells (M–O) IL-10 and IL-12 expressing macrophages in lung cells by intracellular cytokine staining. Data are presented as mean ± s.d N = 5. Each data point represents one animal. One-way ANOVA was carried out. * denotes p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Cellular composition within the spleen provides crucial insights into systemic immunity. While the spleen macrophages and B-cell populations were unchanged with iaNP treatment, a significant increase was seen in key DC populations including cDC1, cDC2, and pDCs (Figure 5E–K). The B-cell population in the splenocytes was not significantly changed with treatment (Figure 4G). While the iaNPs increased activated DC populations, there was no effect on the spleen B-cells or spleen and lung monocyte populations (Figure 5E,L).

In the lung, there was no change in immunosuppressive IL-10 production from macrophages but a significant increase in immunostimulatory IL-12 production, which is similar to that seen in the ex vivo experiments (Figure 5M–O). These results demonstrated a mechanism by which iaNPs delivered systemically induced APC activation in the lymph nodes and spleen. Furthermore, IL-12 secretory macrophages were induced in the tumor microenvironment, likely contributing to innate antitumor immunity of these iaNPs.

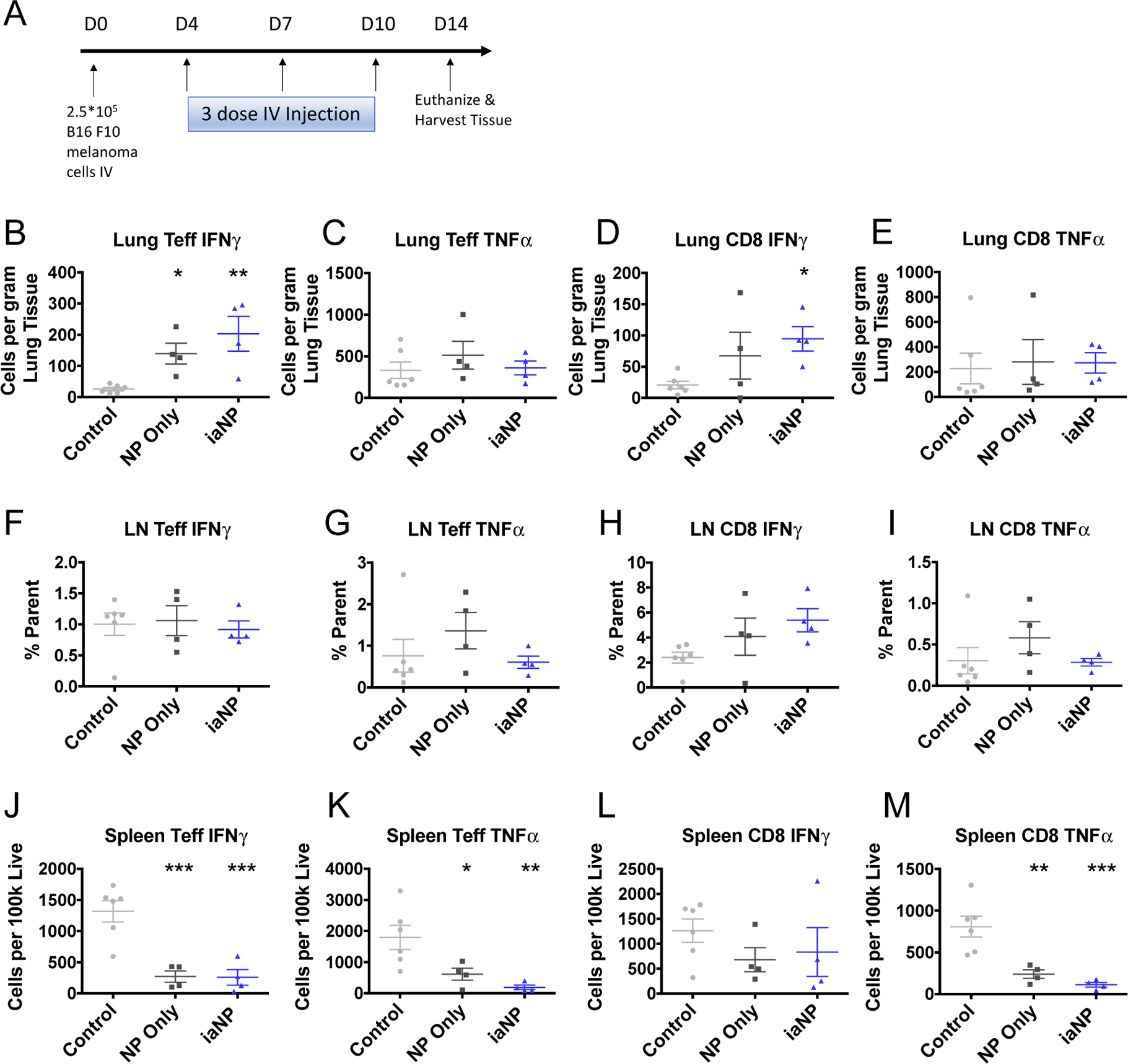

iaNP Increase TRP-2 Sensitized T cells, Stimulating Cytokine Production.

We hypothesized that iaNPs can induce tumor antigen specific T-cell adaptive immune response. Mice were injected IV with B16F10 melanoma on day 0 and treated with PVA only control, NP only, or iaNP intravenously over 10 days then lung tissue analyzed at day 14 (Figure 6A). After tissues were extracted, single-cell isolates were activated with the antigen TRP-2. The cytokine levels of iaNP treated mice were analyzed by flow cytometry. Here, we showed induction of cytokines produced from TRP-2 sensitive cells across all CD4+ and CD8+ populations. First, we analyzed the cell and cytokine populations in the target lung tissue where the melanoma foci localized. Statistically significant increase in type 1 IFN (IFNγ) secretion from CD8+/Foxp3− effector T (Teff) cells in the lung tumor microenvironment was seen with mice treated with iaNP compared to those treated with control (Figure 6B). Antigen-specific effector T-cell responses in the tumor microenvironment were demonstrated in iaNP treatment mice with an increase in the production of IFNγ in the CD8+ cells in the lung in response to TRP-2 stimulation (Figure 6D). TNFα production for Teff and CD8+ populations in the lungs was not changed with treatment (Figure 6C,E). We further investigated the effects on the lymph node and spleen which are distal tissue populations from the site of desired T-cell effects. iaNP treatment did not alter the Teff cytokine production of IFNγ and TNFα in the lymph node (Figure 6F,G). Additionally, we observed a trending increase in CD8+ IFNγ production in the lymph node with iaNP treatment but no change in TNFα production (Figure 6H,I). In the spleen tissue, interestingly, iaNP significantly decreased the IFNγ and TNFα production of Teff cells with NP-only and iaNP treatment (Figure 6J,K). Similarly, we saw a decrease in the TNFα production of CD8+ cells in the spleen, while no difference was seen with the IFNγ production with treatment (Figure 6L,M). Importantly, the iaNP treatment did not alter the T regulatory (Treg) cell populations in the LN, spleen, and lung tissues (Supporting Information 2). Here, we demonstrate not only DC activation, but also induction of TRP-2 specific T-cells localized to the lung tumor microenvironment.

Figure 6.

iaNP induces TRP-2 sensitized T-cells in the tumor environment in the lungs. (A) Timeline (days) for B16F10 melanoma cell intravenous inoculation, treatments, and sacrifice for tissue harvest. Cells are stimulated in aggregate with TRP-2 in culture. (B,C) IFNγ and TNFα expressing CD4+FOXP3− effector T-cells in lung by intracellular cytokine staining. (D,E) IFNγ and TNFα expressing CD45+CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells in the lung. (F,G) Teff and CD8 IFNγ staining in lymph node cells. (H–J) Teff cells in splenocytes. (H) CD4+FOXP3− effector T-cells. (I) IFNγ. (J) TNFα. (K–M) CD8 cells in splenocytes. (K) CD45+CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells. (L) IFNγ. (M) TNFα. Each data point represents one animal. One-way ANOVA was carried out. * denotes p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Immune agonists are promising and potent cancer immunotherapies that can lead to abrogated tumor growth and metastasis. Combination therapies have shown promising results combining immune stimulators with tumor specific antigens.33,47–49 CpG ODNs mimic toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands and are robust immune stimulators and inducers of IFN alpha production and DC maturation.15 RIG-I agonists have been shown to be a potent pathway to trigger the RIG-I pathway leading to an IFN-mediated antiviral response.50 STING agonists have been shown to induce production of IFN-β upon binding to STING, enhancing the activation of DCs.21 We hypothesized that the combination of these innate agonists, TLR9 agonist, RIG-I agonist, and STING agonist to enhance DC activation and presentation with a tumor-specific antigen to prime T-cells to the tumor would lead to enhanced downstream T-cell antitumor activity. However, the instability, short half-life, and potential systemic toxicity of these small molecules can lead to rapid clearance and decreased therapeutic benefit.29,41 Additionally, ongoing clinical trials with IT treatment of STING agonists (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT03010176, NCT03172936) have been promising; however, IT injections are not always feasible based on the tumor type. IT injections are feasible for local delivery, but are challenging in practice and limited to tumors that can be easily reached such as surface cancers like melanoma.51

Here, we wanted to understand the interactions between the NPs and the DC and T-cells that led to this therapeutic response. DC presentation and activation is necessary for the subsequent activation of T-cells. To prime the immune system, the NPs must first be taken up by and prime the appropriate APC population. We demonstrated in vitro that fluorescently labeled PLGA NPs were selectively associated with cDC, pDC, and macrophages with limited association with T- and B-cells. This agrees with prior work that shows particles of similar size range (2–3 μm) are preferentially internalized by macrophages.52 Once the NPs enter the cells, the innate agonists dissociate from the NP, resulting in release of these therapeutics to the desired cell populations with expected downstream activation of these cells.

Next, we showed that co-encapsulation of innate TLR9, RIG-1, and STING agonists with tumor-specific antigen (gp-100 or TRP-2) in biodegradable PLGA NPs led to a decrease in tumor volume compared to the unencapsulated ligand combination and PBS vehicle when administered IV in a subQ melanoma tumor model. The IV injection of the unencapsulated drug can be rapidly cleared, resulting in decreased efficacy in reducing tumor volume compared to the iaNP formulation. Interestingly, NP treatment compared to the unencapsulated drug did not increase efficacy with IT treatment. With IT injection the drug compounds were localized in the tumor, reducing the clearance of the drugs resulting in a therapeutic effect with and without the NPs.

While intratumoral injection is a viable delivery route for surface-accessible tumors such as melanoma, hematological cancer and malignancies require a systemic dosing approach. Because iaNP compared to unencapsulated drug combinations administered IV led to a significantly better efficacy, we believe encapsulation of the drug combination is essential for efficient delivery of these therapeutics. Other work has shown intratumoral versus intravenous administration of microparticles containing cGAMP had no significant difference in reduction in size of a B16.F10 orthotopic tumor, corroborating this study.34 While particles of this size and type accumulate preferentially in the lung, spleen, and liver because of their discontinuous endothelium, we observed immune cell activation at the spleen and distal lymph nodes, which together indicate that a coordinated, systemic antitumor effect is possible with a systemic dosing approach.41,53–55

In a lung melanoma metastasis model, iaNP treatment decreased tumor burden in the lung tissue compared to control and NP-only treatment. There was a modest decrease with NPonly compared to control which suggests the NPs alone generated a nonspecific immune response, leading to a decrease in foci. The PLGA material in the NPs have an acidic byproduct that results in a bystander inflammatory response.56–58 These particles alone are likely to accumulate near tumor foci in the lungs due to their restrictive size and presence of the foci, resulting in targeting by the reticuloendothelial system including monocytes and macrophages.59 This bystander activation likely gives rise to a nonspecific antitumor response. However, when the NPs were loaded with the immune agonist cocktail, we saw a significant decrease in foci indicating a more specific and potent response.

Overall, in vivo, we showed increased activation across DCs with iaNP in lymph nodes and splenocytes. Because the different populations of DC such as cDC1, cDC2, and pDC can lead to different therapeutic responses, we profiled these cell types in skin draining lymph nodes, spleen, and lung tissue of mice treated with iaNP. Peripheral lymph nodes are a target tissue for DC activation because it is the main site of interaction with T-cells to generate an adaptive immune response. In vivo, iaNP treatment increased activated DCs in lymph node and spleen tissue. cDC1 activation results in the cross presentation of antigen through MHCI to activate CD8+ T-cells to promote T helper type I and NK responses.60,61 We showed with iaNP treatment that the number of cDC1 activated cells increased in lymph node and spleen tissue. While we also showed an increase with cDC2 cells, these cells are activated by TLRs such as RIG-I and appear to stimulate CD4+ T-cells. Other groups have shown that STING agonist microparticles stimulate an NK and CD8 T-cell-dependent antitumor response, indicating that this multiadjuvant approach may coordinate a broader adaptive immune response that involves a T helper component.55

This cDC2 response is particularly interesting, as they are associated with promotion of the Th2 immune response, which activates B-cells to produce antibodies.60,61 While we observed little particle association with B-cells themselves, increased CD86 expression indicates at least partial bystander activation, which other groups have shown to be the case in response to type 1 IFNs.62,63 Because B-cells may produce tumor specific antibodies to recruit myeloid cells via ADCC, this would be an interesting finding to investigate further. pDCs migrate through the blood and lymphoid tissue which stimulates type I interferons, resulting in the stimulation and activation of T-cells.60,61 The activated pDC population increased with iaNP treatment was found in both lymph nodes and spleen.

Because 30% of the macrophages appear to be associated with NPs in vitro, we showed that with iaNP in vivo the macrophage population increased in the lung, while no difference was seen in the spleen. Macrophages produce cytokines IL-10 and IL-12; IL-10 has been shown to limit the extent of activation of innate and adaptive immune cells, while IL-12 is a proinflammatory cytokine that is produced by APCs and can further activate NK cells and induce differentiation of CD4+ T-cells to IFNγ producing T helper 1 effectors.64 The simultaneous generation of both alternatively activated macrophages via IL-10 as well as those with the suppressive M2 phenotypic signature secreting IL-12 by STING agonists has been demonstrated previously, and the specific role these macrophages play in antitumor immunity remains unclear.65 In this study, we showed that with IV administration of this adjuvant cocktail, the so-called M2 macrophages were found in the spleen but were not significantly different from control in the lung, which may resolve this disparity by showing that proinflammatory and antitumor macrophages expressing IL-12 are predominant at the tumor site, whereas suppressive IL-10 secreting cells remain in the spleen, possibly to compensate for systemic inflammation, as is seen post viral infection.66,67

Along with co-encapsulation of the agonists to enhance DC activation and antigen presentation, we encapsulated a melanoma-specific peptide with the goal of sensitizing T-cells to this antigen, allowing for the generation of T-cells with this peptide specific receptor on the surface which can then target the specific protein on the melanoma cancer cells. For this analysis, we utilized the TRP-2 peptide and the metastatic melanoma model. When cytotoxic T-cells are activated, they can target and kill tumor cells with multiple strategies including secretion of cytokines such as IFNγ and TNFα. After culturing tissue-specific single-cell isolates with TRP-2, we showed an increase in lung Teff and CD8+ production of IFNγ. The T-cell activation was minimal in the lymph node compared to the lung, which indicated that the T-cells have migrated from the lymph node to the site of action where the melanoma was present in the lungs. Interestingly, we also showed a decrease in the Teff IFNγ-producing cells, indicating that these cells have migrated from the spleen and to the site of action where we saw an increase in IFNγ-producing cells. This effector T-cell component provides further evidence for the benefit of coencapsulation, given that cGAMP encapsulated particles alone induce a predominantly NK and cytotoxic CD8 T-cell response.55,68

In summary, we demonstrated NP loading with an adjuvant agonist cocktail to reduce mouse tumor burden in a subQ and metastatic melanoma mouse model. NPs were efficiently internalized by APC, resulting in activation of these cell populations. APC activation led to an increase in activated T-cells primed against the melanoma target to result in an increase in cytokine production and decrease in melanoma. Further investigation of these systemically administered immune agonistic particles combined with other adaptive immunity therapeutic approaches such as PD-1 is supported by the current studies.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a UCSF Program in Breakthrough Biomedical Research (PBBR) grant to T.A.D. E.S.L. was supported by the American Foundation for Pharmaceutical Education and by the NIH Training grant 5T32GM007175-27. R.C. is supported by MSTP NIH Training grant 2T32GM007618. Confocal fluorescence imaging was conducted at the UCSF Nikon Imaging Center and flow cytometry at the UCSF Flow Cytometry Core.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest. L.F. has received research support from Abbvie, Bavarian Nordic, BMS, Dendreon, Janssen, Merck, and Roche/Genentech.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.0c00984.

NP characterization by SEM and DLS, SEC–HPLC traces, Treg analysis, and flow cytometry gating strategy (PDF)

Contributor Information

Elizabeth S. Levy, Department of Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California 94158, United States.

Ryan Chang, Department of Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California 94158, United States; Department of Medicine, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California 94143, United States.

Colin R. Zamecnik, Department of Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California 94158, United States.

Miqdad O. Dhariwala, Department of Dermatology, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California 94143, United Stats

Lawrence Fong, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California 94143, United States; Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California 94143, United States.

Tejal A. Desai, Department of Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California 94158, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Wang J; Li D; Cang H; Guo B Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: Role of tumor-associated macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 4709–4721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Vinay DS; et al. Immune evasion in cancer: Mechanistic basis and therapeutic strategies. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2015, 35, S185–S198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Prendergast GC Immune escape as a fundamental trait of cancer: Focus on IDO. Oncogene 2008, 27, 3889–3900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Komiya T; Huang CH Updates in the clinical development of Epacadostat and other indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 inhibitors (IDO1) for human cancers. Front. Oncol 2018, 8, 423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Dembic Z CThe Cytokines of the Immune System: The Role of Cytokines in Disease Related to Immune Response; Academic Press, 2015; pp 123–142. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Zhou F Molecular Mechanisms of IFN-γ to Up-Regulate MHC Class I Antigen Processing and Presentation. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 28, 239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kinter AL; et al. The Common γ-Chain Cytokines IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, and IL-21 Induce the Expression of Programmed Death-1 and Its Ligands. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 6738–6746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Marckmann S; et al. Interferon-β up-regulates the expression of co-stimulatory molecules CD80, CD86 and CD40 on monocytes: Significance for treatment of multiple sclerosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2004, 138, 499–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Fuertes MB; Woo S-R; Burnett B; Fu Y-X; Gajewski TF Type I interferon response and innate immune sensing of cancer. Trends Immunol. 2013, 34, 67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Dar TB; Henson RM; Shiao SL Targeting innate immunity to enhance the efficacy of radiation therapy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 9, 3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Fazle Akbar SM; Inaba K; Onji M Upregulation of MHC class II antigen on dendritic cells from hepatitis B virus transgenic mice by interferon-γ: abrogation of immune response defect to a T-cell-dependent antigen. Immunology 1996, 87, 519–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Mogensen TH Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 22, 240–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Kaufman HL; Kohlhapp FJ; Zloza A Oncolytic viruses: A new class of immunotherapy drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2015, 14, 642–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Sierra H; Cordova M; Chen C-SJ; Rajadhyaksha M Confocal imaging-guided laser ablation of basal cell carcinomas: An ex vivo study. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 612–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Krieg AM; Krieg AM Development of TLR9 agonists for cancer therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 2007, 117, 1184–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Krieg AM Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) agonists in the treatment of cancer. Oncogene 2008, 27, 161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Krieg AM Therapeutic potential of toll-like receptor 9 activation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2006, 5, 471–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Reilley M; et al. Phase 1 trial of TLR9 agonist lefitolimod in combination with CTLA-4 checkpoint inhibitor ipilimumab in advanced tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, TPS2669. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Sato-Kaneko F; et al. Combination immunotherapy with TLR agonists and checkpoint inhibitors suppresses head and neck cancer. JCI insight 2017, 2, No. e93397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Medrano RFV; Hunger A; Mendonca SA; Barbuto JAM¸; Strauss BE¸ Immunomodulatory and antitumor effects of type I interferons and their application in cancer therapy. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 71249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Jing W; et al. STING agonist inflames the pancreatic cancer immune microenvironment and reduces tumor burden in mouse models. J. Immunother. Canc. 2019, 7, 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Burdette DL; et al. STING is a direct innate immune sensor of cyclic di-GMP. Nature 2011, 478, 515–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Dubensky TW; Kanne DB; Leong ML Rationale, progress and development of vaccines utilizing STING-activating cyclic dinucleotide adjuvants. Ther. Adv. Vaccines 2013, 1, 131–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Zhang Y; Yeruva L; Marinov A; Prantner D; Wyrick PB; Lupashin V; Nagarajan UM The DNA sensor, cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) is essential for induction of IFN beta during Chlamydia trachomatis infection. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 2394–2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Yoneyama M; Fujita T RNA recognition and signal transduction by RIG-I-like receptors. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 227, 54–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Chen Y; et al. Gene expression profile after activation of RIG-I in 5’ppp-dsRNA challenged DF1. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2016, 65, 191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Zevini A; Olagnier D; Hiscott J Cross-Talk between the Cytoplasmic RIG-I and STING Sensing Pathways. Trends Immunol. 2017, 38, 194–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Hamdy S; et al. Co-delivery of cancer-associated antigen and Toll-like receptor 4 ligand in PLGA nanoparticles induces potent CD8+ T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity. Vaccine 2008, 26, 5046–5057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Hanson MC; et al. Nanoparticulate STING agonists are potent lymph node-targeted vaccine adjuvants. J. Clin. Invest. 2015, 125, 2532–2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Martins KA; Bavari S; Salazar AM Vaccine adjuvant uses of poly-IC and derivatives. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2015, 14, 447–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Meric-Bernstam F; et al. Phase Ib study of MIW815 (ADU-S100) in combination with spartalizumab (PDR001) in patients (pts) with advanced/metastatic solid tumors or lymphomas. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 2507. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Shae D; et al. Endosomolytic polymersomes increase the activity of cyclic dinucleotide STING agonists to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 269–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Conniot J; et al. Immunization with mannosylated nano-vaccines and inhibition of the immune-suppressing microenvironment sensitizes melanoma to immune checkpoint modulators. Nat. Nanotechnol 2019, 14, 891–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Cheng N; et al. A nanoparticle-incorporated STING activator enhances antitumor immunity in PD-L1-insensitive models of triple-negative breast cancer. JCI insight 2018, 3, No. e120638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Wang C; Ye Y; Hochu GM; Sadeghifar H; Gu Z Enhanced Cancer Immunotherapy by Microneedle Patch-Assisted Delivery of Anti-PD1 Antibody. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 2334–2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Jacobson ME; Wang-Bishop L; Becker KW; Wilson JT Delivery of 5′-triphosphate RNA with endosomolytic nanoparticles potently activates RIG-I to improve cancer immunotherapy. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 547–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Yang HG; Hu BL; Xiao L; Wang P Dendritic cell-directed lentivector vaccine induces antigen-specific immune responses against murine melanoma. Cancer Gene Ther. 2011, 18, 370–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Vasievich EA; Ramishetti S; Zhang Y; Huang L Trp2 peptide vaccine adjuvanted with (R)-DOTAP inhibits tumor growth in an advanced melanoma model. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2012, 9, 261–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Bloom MB; et al. Identification of tyrosinase-related protein 2 as a tumor rejection antigen for the B16 melanoma. J. Exp. Med. 1997, 185, 453–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Kim H; Niu L; Larson P; Kucaba TA; Murphy KA; James BR; Ferguson DM; Griffith TS; Panyam J Polymeric nanoparticles encapsulating novel TLR7/8 agonists as immunostimulatory adjuvants for enhanced cancer immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2018, 164, 38–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Das M; Shen L; Liu Q; Goodwin TJ; Huang L Nanoparticle Delivery of RIG-I Agonist Enables Effective and Safe Adjuvant Therapy in Pancreatic Cancer. Mol. Ther. 2019, 27, 507–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Overwijk WW; Restifo NP B16 as a Mouse Model for Human Melanoma. Current Protocols in Immunology; Wiley, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Blanco MD; Alonso MJ Development and characterization of protein-loaded poly(lactide-co-glycolide) nanospheres. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 1997, 43, 287–294. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Lecaroz MC; Blanco-Prieto MJ; Campanero MA; Salman H; Gamazo C Poly(D,L-lactide-coglycolide) particles containing gentamicin: Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in Brucella melitensis-infected mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 1185–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Cun D; et al. High loading efficiency and sustained release of siRNA encapsulated in PLGA nanoparticles: Quality by design optimization and characterization. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2011, 77, 26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Dolfi DV; et al. Dendritic Cells and CD28 Costimulation Are Required To Sustain Virus-Specific CD8 + T Cell Responses during the Effector Phase In Vivo. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 4599–4608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Rosalia RA; et al. CD40-targeted dendritic cell delivery of PLGA-nanoparticle vaccines induce potent anti-tumor responses. Biomaterials 2015, 40, 88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Nembrini C; et al. Nanoparticle conjugation of antigen enhances cytotoxic T-cell responses in pulmonary vaccination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108, No. E989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Lei YMK; Nair L; Alegre M-L The interplay between the intestinal microbiota and the immune system. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2015, 39, 9–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Binder M; et al. Molecular mechanism of signal perception and integration by the innate immune sensor retinoic acid-inducible gene-i (RIG-I). J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 27278–27287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Lammers T; et al. Effect of intratumoral injection on the biodistribution and the therapeutic potential of HPMA copolymer-based drug delivery systems. Neoplasia 2006, 8, 788–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Champion JA; Walker A; Mitragotri S Role of particle size in phagocytosis of polymeric microspheres. Pharm. Res. 2008, 25, 1815–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Meyer RA; et al. Biodegradable Nanoellipsoidal Artificial Antigen Presenting Cells for Antigen Specific T-Cell Activation Randall. Small 2015, 11, 1519–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Kosmides AK; et al. Biomimetic Biodegradable Artificial Antigen Presenting Cells Synergize with PD-1 Blockade to Treat Melanoma. Biomaterials 2018, 118, 16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Watkins-Schulz R; et al. A microparticle platform for STING-targeted immunotherapy enhances natural killer cell and CD8+ T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity. Biomaterials 2019, 205, 94–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Lee Y; Kwon J; Khang G; Lee D Reduction of inflammatory responses and enhancement of extracellular matrix formation by vanillin-incorporated poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) scaffolds. Tissue Eng., Part A 2012, 18, 1967–1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Kim MS; et al. An in vivo study of the host tissue response to subcutaneous implantation of PLGA- and/or porcine small intestinal submucosa-based scaffolds. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 5137–5143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Nicolete R; Santos DFD; Faccioli LH The uptake of PLGA micro or nanoparticles by macrophages provokes distinct in vitro inflammatory response. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2011, 11, 1557–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Tang Y; et al. Overcoming the Reticuloendothelial System Barrier to Drug Delivery with a ‘don’t-Eat-Us’ Strategy. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 13015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Collin M; Bigley V Human dendritic cell subsets: an update. Immunology 2018, 154, 3–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Schlitzer A; et al. Identification of cDC1- and cDC2-committed DC progenitors reveals early lineage priming at the common DC progenitor stage in the bone marrow. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 718–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Kiefer K; Oropallo MA; Cancro MP; Marshak-Rothstein A Role of type i interferons in the activation of autoreactive B cells. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2012, 90, 498–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Crampton SP; Voynova E; Bolland S Innate pathways to B-cell activation and tolerance. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1183, 58–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Ma X; et al. Regulation of IL-10 and IL-12 production and function in macrophages and dendritic cells. F1000Research 2015, 4, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Ohkuri T; Kosaka A; Nagato T; Kobayashi H Effects of STING stimulation on macrophages: STING agonists polarize into “classically” or “alternatively” activated macrophages? Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018, 14, 285–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Ohkuri T; et al. Intratumoral administration of cGAMP transiently accumulates potent macrophages for anti-tumor immunity at a mouse tumor site. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2017, 66, 705–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Borges da Silva H; et al. Splenic macrophage subsets and their function during blood-borne infections. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Collier MA; et al. Acetalated Dextran Microparticles for Codelivery of STING and TLR7/8 Agonists. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 4933–4946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.