Objectives:

Most biomarker studies of sepsis originate from high-income countries, whereas mortality risk is higher in low- and middle-income countries. The second version of the Pediatric Sepsis Biomarker Risk Model (PERSEVERE-II) has been validated in multiple North American PICUs for prognosis. Given differences in epidemiology, we assessed the performance of PERSEVERE-II in septic children from Pakistan, a low-middle income country. Due to uncertainty regarding how well PERSEVERE-II would perform, we also assessed the utility of other select biomarkers reflecting endotheliopathy, coagulopathy, and lung injury.

Design:

Prospective cohort study.

Setting:

PICU in Aga Khan University Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan.

Patients:

Children (< 18 yr old) meeting pediatric modifications of adult Sepsis-3 criteria between November 2020 and February 2022 were eligible.

Interventions:

None.

Measurements and Main Results:

Plasma was collected within 24 hours of admission and biomarkers quantified. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for PERSEVERE-II to discriminate 28-day mortality was determined. Additional biomarkers were compared between survivors and nonsurvivors and between subjects with and without acute respiratory distress syndrome. In 86 subjects (20 nonsurvivors, 23%), PERSEVERE-II discriminated mortality (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.72–0.94) and stratified the cohort into low-, medium-, and high-risk of mortality. Biomarkers reflecting endotheliopathy (angiopoietin 2, intracellular adhesion molecule 1) increased across worsening risk strata. Angiopoietin 2, soluble thrombomodulin, and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 were higher in nonsurvivors, and soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products and surfactant protein D were higher in children meeting acute respiratory distress syndrome criteria.

Conclusions:

PERSEVERE-II performs well in septic children from Aga Khan University Hospital, representing the first validation of PERSEVERE-II in a low-middle income country. Patients possessed a biomarker profile comparable to that of sepsis from high-income countries, suggesting that biomarker-based enrichment strategies may be effective in this setting.

Keywords: biomarker, children, low- and middle-income countries, prognostic enrichment, sepsis

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Most translational investigations of sepsis use blood samples from patients in high-income Western countries, whereas the human and financial cost of sepsis is higher in low- and middle-income countries.

As biomarker-based prognostic and predictive enrichment strategies gain favor, it is important to determine their utility in low- and middle-income countries.

We validated the Pediatric Sepsis Biomarker Risk Model (PERSEVERE)-II, a biomarker-based risk stratification tool for pediatric sepsis developed in North America, in a cohort of septic children from Aga Khan University Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan.

AT THE BEDSIDE

PERSEVERE-II performs equally well in pediatric sepsis subjects from Pakistan for risk stratification.

Biomarkers reflecting innate immune activity and endotheliopathy were associated with worse prognosis, and biomarkers reflecting lung damage were associated with development of acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Pediatric sepsis from Pakistan, a low-middle-income country, has a biomarker profile similar to what has been reported in adult and pediatric sepsis from high-income countries, suggesting that biomarker-based enrichment strategies may be applicable to this population.

Sepsis, defined as a dysregulated host response to infection causing organ failure (1), is responsible for 11 million deaths worldwide every year (2). However, this burden is not spread equally across the globe, with Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and Oceania over-represented for both sepsis incidence and mortality (2–5). Additionally, the impact is not constant across age groups, with children under 18 years old being approximately twice as likely to die from sepsis as adults (2). The etiologies for geo-economic discrepancies are multifactorial, including fewer resources in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), different infectious etiologies, lower vaccination rates for preventable infections, and different baseline comorbidities, including nutritional status (2–6). The biochemical ramifications of these differences, however, is unknown, as most translational investigations of sepsis use samples from patients in high-income Western countries (7–9). Given these differences in epidemiology, there is a disconnect between the existing translational knowledge of sepsis derived from children in high-income countries and those in the developing world most at risk.

In both adults and children, sepsis is heterogeneous, with patients having distinct comorbidities and inciting etiologies (6, 10, 11). This heterogeneity has contributed to negative trial results, as therapies effective in some patients are ineffective in others (12, 13). To mitigate this heterogeneity, biomarkers have been used to identify high-risk subgroups (14, 15) as well as subtypes with shared biochemical profiles (16–19). Accurate risk stratification is essential for prognostic enrichment in clinical trials, as several interventions studied in sepsis may only demonstrate benefit in patients at higher risk of mortality (12, 20). In the United States, the Pediatric Sepsis Biomarker Risk Model (PERSEVERE) is a validated biomarker-based risk stratification tool to estimate baseline mortality risk (14). An updated version, PERSEVERE-II, leverages five protein biomarkers and platelets collected within 24 hours of PICU admission in septic children to estimate 28-day mortality risk, with area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curves greater than 0.80 in multiple PICUs (15, 21). However, the utility of PERSEVERE-II in resource-limited settings is unknown. Therefore, given differences in sepsis epidemiology, we assessed the performance of PERSEVERE-II in septic children from Pakistan, a low-middle-income country. Due to uncertainty regarding how well PERSEVERE-II would perform in this cohort, we assessed the prognostic utility of other select biomarkers reflecting endothelial dysfunction and dysregulated coagulation (22). Finally, given the prognostic impact of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in sepsis (23), we also measured biomarkers reflecting lung epithelial injury (24, 25). We hypothesized that PERSEVERE-II would discriminate mortality with AUROC of at least 0.80 in this cohort, with an intent to revise the model with additional biomarkers if needed to improve discrimination.

METHODS

Study Design

This is an ongoing prospective cohort study conducted at the Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH) PICU between November 2020 and February 2022 and reported according to STAndards for the Reporting of Diagnostic accuracy studies guidance. The study was approved by the AKUH Ethics Review Committee (ERC 2020-5291-14343; Linking Endotypes and Outcomes in Sepsis Induced Pediatric ARDS; approved October 9, 2020), with consent obtained prior to research procedures, consistent with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Patient Selection

Eligible subjects met pediatric modifications of adult Sepsis-3 criteria (1, 26). Briefly, subjects were eligible if they were: 1) aged older than 44 weeks corrected gestational age and younger than 18 years, 2) presumed infection, 3) pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (pSOFA) score of at least 2, and 4) lactate greater than 2 mmol/L. Exclusion criteria were: 1) weight less than 3 kilograms, 2) not expected to survive longer than 72 hours, 3) limitations of care at time of screening, or 4) previous enrollment in this study.

Sample Collection and Measurements

Clinical data were prospectively collected prospectively at AKUH. After informed consent, plasma was collected in citrated tubes within 24 hours of PICU admission, centrifuged (2,000g for 20 min at 20°C), aliquoted, and frozen at –80°C. Samples were shipped on dry ice to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and to Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) for biomarker assays (transit times of 7 and 10 d on dry ice). Biomarkers at CHOP were measured using singleplex enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (R & D Systems) and included angiopoietin 2 (ANG2), the soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products (sRAGE), soluble thrombomodulin (sTM), and surfactant protein D (SPD), plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI1), and intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1). The PERSEVERE-II biomarkers of granzyme B, heat shock protein 70, interleukin-8, C-C motif chemokine ligand 3 (CCL3)/macrophage inflammatory protein-1α, and matrix metalloproteinase 8 (MMP8) were measured on a Luminex platform at CCHMC (15). Biomarkers were measured in duplicate. Platelets were recorded as part of clinical data collection at AKUH.

Definitions and Outcomes

Sepsis was defined using a pediatric modification of Sepsis-3 (pSOFA ≥ 2 and lactate > 2) (26). Pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome (PARDS) was defined using 2015 Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference (PALICC) criteria for intubated subjects (27). Severity of illness was recorded using pSOFA (26) and the Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction (PELOD)-2 score (28). Degree of shock was quantified using the highest vasopressor-inotrope score on the day of admission (29). The presumed type of infection was determined through a combination of clinical suspicion, culture (bacterial, fungal), and polymerase chain reaction (viral) data. The designation “immunocompromised” required an immunocompromising diagnosis (oncologic, immunologic, rheumatologic, transplant) on active immunosuppressive chemotherapy or a congenital immunodeficiency (30). The primary outcome was 28-day mortality.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted in State 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Our primary aim was to test the utility of PERSEVERE-II. Projecting a mortality rate of 15%, 73 subjects were required to detect an AUROC of at least 0.80 with α = 0.05 and power = 0.90. PERSEVERE-II was a recalibration of the original PERSEVERE risk prediction model that added platelets as a predictor variable (14, 15). Both models were developed using classification and regression tree (CART) and provided estimates for their terminal nodes corresponding to low, medium, and high risk of 28-day mortality. The PERSEVERE-II model cutoffs were applied to the AKUH cohort, and tested for discrimination of 28-day mortality, reporting AUROC. As a sensitivity analysis, we tested the discriminative ability of PERSEVERE-II in the AKUH cohort using the exact predicted probabilities of mortality reported in the original publication, which had a 28-day mortality rate of 12% (15). Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were reported after assigning subjects in low-risk nodes as predicted survivors, assigning medium- and high-risk nodes as predicted nonsurvivors, and comparing predicted with actual survival. Survival curves and biomarker levels were compared between subjects in low-, medium-, and high-risk nodes using log-rank tests and Cuzick’s test of trend, respectively. Additional biomarkers were compared between bacterial and viral sepsis, between survivors and nonsurvivors, between those without and without PARDS, using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Finally, in an exploratory analysis, we rederived a decision tree using all available biomarkers (including platelets) as input variables and report test characteristics.

RESULTS

Description of the Cohort

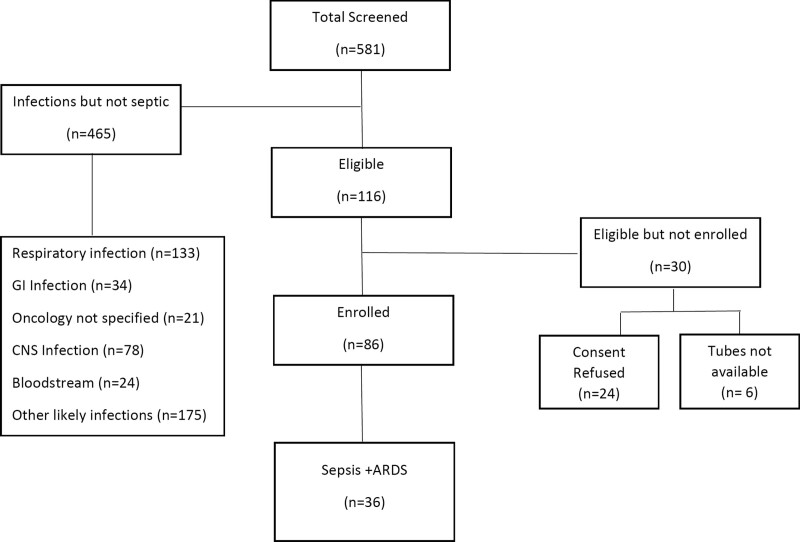

There were 86 subjects with sepsis enrolled (Fig. 1), of whom 20 died (23%) by day 28 (Table 1). Lung (66%) and abdomen (20%) were the most common sites of infection. Bacteria were implicated in the majority of infections (41%), followed by culture-negative (29%) and viral sepsis (27%). PELOD and pSOFA scores were high, and 88% required vasopressors at admission. Of the cohort, 36 (42%) met PARDS criteria by 96 hours, with a median of 4 hours (interquartile range, 2–12 hr) to onset. Mortality was higher in immunocompromised subjects (41% vs 19% in immunocompetent), as well higher in those with PARDS (31% vs 18% in those without).

Figure 1.

Patient flowchart. ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome.

TABLE 1.

Demographics of the Cohort (n = 86)

| Variable | Values |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age (yr), median (IQR) | 2.7 (0.4–12) |

| Assigned female sex (%) | 33 (39) |

| Stunted (height < 5%ile) (%) | 18 (21) |

| Weight for length < 5%ile (%) | 9 (10) |

| Comorbid conditions (%) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 3 (3) |

| Chronic liver disease | 6 (7) |

| Immunocompromised | 17 (20) |

| Oncologic | 13 (15) |

| Stem cell transplant | 2 (2) |

| Site of infection (%) | |

| Lung | 57 (66) |

| Abdomen | 20 (23) |

| Other | 9 (10) |

| Presumed type of infection (%) | |

| Bacterial | 35 (41) |

| Viral | 23 (27) |

| Fungal | 3 (3) |

| Culture negative | 25 (29) |

| Severity of illness | |

| Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction-2, median (IQR) | 6 (4–8) |

| Pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, median (IQR) | 8 (6–11) |

| Vasopressors (%) | 76 (88) |

| Vasopressor-inotrope score (n = 76), median (IQR) | 8 (5–11) |

| Lactate (mmol/L), median (IQR) | 3.1 (2.4–4.8) |

| Ancillary therapies, n (%) | |

| Corticosteroids | 38 (44) |

| IV immunoglobulin | 10 (13) |

| Renal replacement therapy | 10 (13) |

| PARDS | |

| PARDS within 96 hr of sepsis, n (%) | 36 (42) |

| Time to PARDS (hr), median (IQR) | 4 (2–12) |

| 28-d mortality, n (%) | 20 (23) |

IQR = interquartile range, PARDS = pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome.

PERSEVERE-II Performance in Septic Children From AKUH

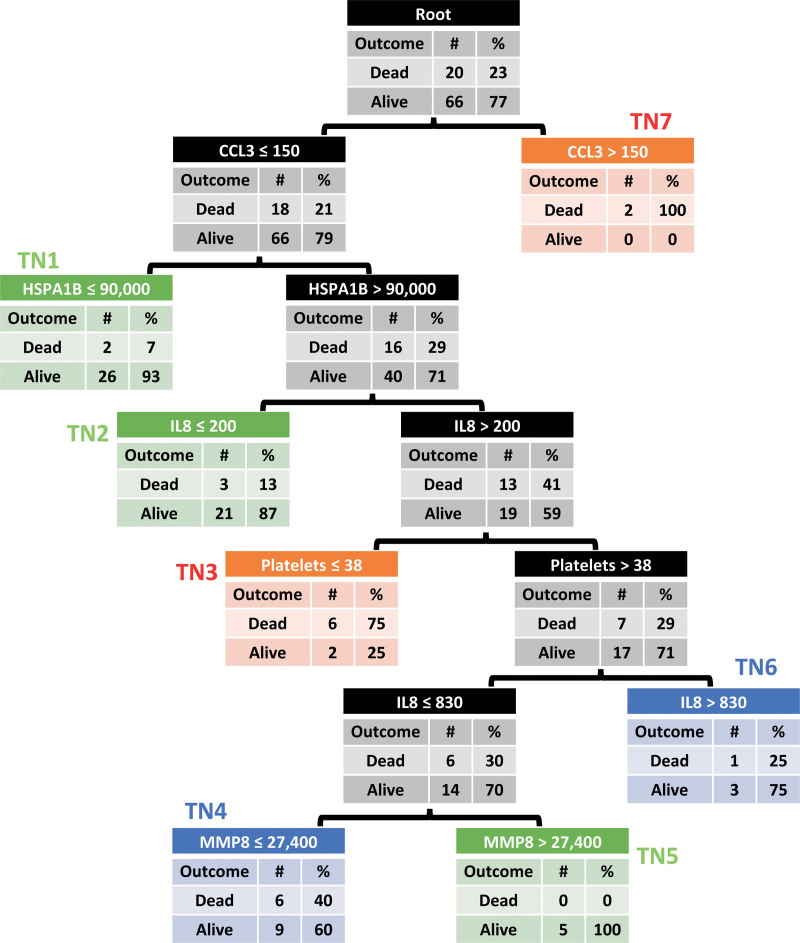

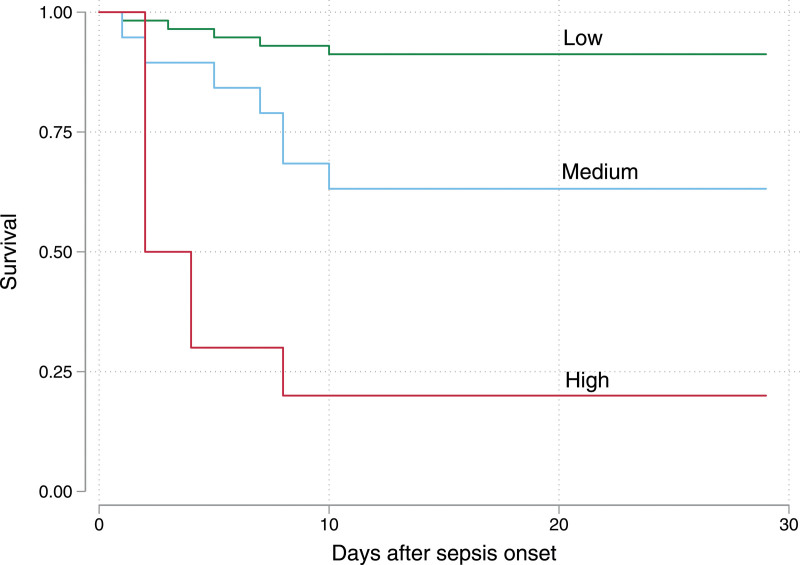

PERSEVERE-II was applied to the cohort using the original described cutoffs (Fig. 2) (15). Terminal nodes 7 to 11 in the original PERSEVERE were pruned to a single node (terminal node 7) as there were only two subjects with levels of CCL3 greater than 150 pg/mL. With this model, PERSEVERE-II discriminated mortality with an AUROC of 0.83 (95% CI, 0.72–0.94), a sensitivity of 0.75, a specificity of 0.79, a PPV of 0.52, and NPV of 0.91. Terminal nodes 1, 2, and 5 were low-risk, with mortality less than 15%. Terminal nodes 4 and 6 were medium-risk, with mortality between 25% and 40%. Terminal nodes 3 and 7 were high-risk, with mortality ranging from 75% to 100%. Figure 3 shows 28-day Kaplan-Meier curves for subjects grouped according to their risk strata (overall log-rank p < 0.001; all pairwise log-rank p < 0.01). PERSEVERE-II predicted mortality comparably to pSOFA (p = 0.431 for comparison of AUROCs) and PELOD-2 (p = 0.397) but significantly better than the vasopressor-inotrope score (p = 0.017) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Classification and regression tree-based Pediatric Sepsis Biomarker Risk Model (PERSEVERE)-II model stratifying septic children into one of seven terminal nodes (TNs). All subjects start at the root node at the top and subsequently stratified according to biomarker levels into TNs. TNs 1, 2, and 5 (green) are low-risk of 28-d mortality. TNs 4 and 6 (blue) are medium-risk. TNs 3 and 7 (red) are high-risk). For comparison, the color-coded low-, medium-, and high-risk TNs are identical to those identified using the PERSEVERE-II model in children from the United States, albeit with lower mortality rates in the original cohort (low-risk < 2%, medium-risk 15–20%, high-risk > 40% predicted mortality risk). TN7 in this cohort from Aga Khan University Hospital is pruned from the original PERSEVERE-II due to only having two subjects. CCL3 = C-C motif chemokine ligand 3, GI = gastrointestinal, HSPA1B = heat shock protein 72, IL8 = interleukin-8, MMP8 = matrix metalloproteinase 8.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for subjects stratified into low- (green), medium- (blue), and high-risk (red) Pediatric Sepsis Biomarker Risk Model-II strata. Overall log-rank p < 0.001. Pairwise comparisons (low-risk vs medium-risk p = 0.003; medium-risk vs high-risk p = 0.008; low-risk vs high-risk p < 0.001) are also significant.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves

| Model | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (95% CI) | p vs PERSEVERE-II |

|---|---|---|

| PERSEVERE-II | 0.83 (0.72–0.94) | — |

| Pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment | 0.72 (0.60–0.85) | 0.431 |

| Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction-2 | 0.72 (0.61–0.94) | 0.397 |

| Vasopressor-inotrope score | 0.58 (0.43–0.73) | 0.017 |

PERSEVERE-II = Pediatric Sepsis Biomarker Risk Model-II.

As a sensitivity analysis, we tested the performance characteristics of PERSEVERE-II using the exact mortality probabilities reported in the originally described model from the United States (mortality ranging from 0% in terminal node 1 to 44% in terminal node 3, 12% in the entire cohort) (15). Using these inputs, PERSEVERE-II had an AUROC of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.68–0.92). Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV would not change with this analysis.

Prognostic Biomarkers in Pediatric Sepsis

Endothelial dysfunction, thrombotic microangiopathy, and lung injury are thought to drive organ failure and worse outcomes in sepsis. Therefore, we assessed whether select markers of endotheliopathy (ANG2, ICAM1, sRAGE), dysregulated coagulation (sTM and PAI1), and lung injury (sRAGE and SPD) differed according to PERSEVERE risk strata (Supplementary Fig. 1, http://links.lww.com/PCC/C364). ANG2, ICAM1, sRAGE, sTM, and PAI1 were higher in medium- and high-risk strata (all Cuzick’s p < 0.05), with stepwise increases from low- to high-risk for ANG2 and ICAM1. We tested these additional biomarkers for association with mortality, as it was not clear how well PERSEVERE-II would perform in this cohort. ANG2, sTM, and PAI1 were all elevated in nonsurvivors (all rank-sum p < 0.05) relative to survivors (Supplementary Fig. 2, http://links.lww.com/PCC/C364). Biomarker levels were not significantly different between bacterial and viral sepsis etiologies (Supplementary Fig. 3, http://links.lww.com/PCC/C364).

SPD and sRAGE Are Elevated in Septic PARDS

We also compared biomarker levels between subjects who did (n = 36) and did not (n = 50) meet PALICC criteria for PARDS within 96 hours of sepsis onset. PARDS onset was rapid, with most PARDS subjects meeting concurrently meeting sepsis and PALICC criteria. Markers of type I (sRAGE) and type II (SPD) alveolar epithelial damage were elevated in subjects with PARDS (both rank-sum p < 0.01) relative to those without (Supplementary Fig. 4, http://links.lww.com/PCC/C364).

Exploratory Analysis Using All Biomarkers

To explore the potential added utility of the additional biomarkers measured, we rederived a decision tree using CART with all available biomarkers (and platelets) as inputs (Supplementary Fig. 5, http://links.lww.com/PCC/C364). This resulted in a tree with six terminal nodes, with PAI1, ANG2, platelets, MMP8, and sRAGE retained in the model. The new decision tree showed a higher AUROC for mortality discrimination (AUROC, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.63–1), a sensitivity of 1, specificity of 0.77, a PPV of 0.57, and NPV of 1. This AUROC, while higher, did not significantly differ from the AUROC 0.83 for PERSEVERE-II (p = 0.302).

DISCUSSION

We report the first validation of PERSEVERE-II, an established risk prediction model for pediatric sepsis, in a low-middle income country. In this cohort, with twice the mortality rate of comparable cohorts from high-income countries (15, 21), PERSEVERE-II had similar performance, with AUROC near 0.80. We additionally demonstrated preliminary evidence for added prognostic utility for biomarkers of endotheliopathy and coagulation in pediatric sepsis, as well as the utility of lung-associated biomarkers to identify PARDS in septic children. Overall, the molecular phenotype of sepsis from AKUH reflected in these biomarkers parallels what has been reported in cohorts from high-income countries, suggesting that biomarker-based risk stratification and subphenotyping strategies may generalize to LMICs.

The major utility of risk stratification models such as PERSEVERE-II is for identifying subjects at low risk, who potentially should be excluded from trials of aggressive intervention, and at very high risk, who may have limited ability to modify their outcome with a trial intervention (20, 21). While the utility of any risk stratification model requires rigorous prospective assessment in the setting of a trial, the first step is development and testing of a reliable risk stratification tool. Our results support the use of PERSEVERE-II for this purpose in pediatric sepsis. As in other reports of PERSEVERE-II (15, 21), NPV was higher than PPV, although not quite as high as in cohorts from the United States due to higher mortality at AKUH, which may limit its utility for excluding low-risk subjects from trials. The higher mortality at AKUH also resulted in a higher PPV than other reports of PERSEVERE-II in the United States. Overall, PERSEVERE-II stratified the cohort into low-, medium-, and high-risk subgroups, confirming prognostic utility. In exploratory analysis, the addition of endothelial, coagulation, and lung injury biomarkers improved the sensitivity and NPV of the mortality prediction model, suggesting potential value for better identifying low-risk subjects.

While the vast majority of biomarker-based studies for prognostic and predictive enrichment in critical illness syndromes like sepsis and ARDS have occurred in high-income countries, the mortality burden of these conditions is disproportionately carried by lower income countries (2). This cohort from AKUH, for example, has twice the mortality rate of comparable pediatric sepsis cohorts (14, 15), despite a similar distribution of age, primary site of infection, and comorbidity profile. With few biomarker studies in septic subjects from LMICs, adult or pediatric, it is unclear whether their molecular phenotypes are similar or not to what has been reported in the literature. Our results demonstrate that this cohort has a biomarker profile consistent with what has been reported and that existing biomarker-based strategies would likely be applicable.

There is a paucity of studies measuring biomarkers in pediatric sepsis from Pakistan, and none identifying prognostically useful proteins (31). In our study, in addition to the prognostic utility of the inflammatory biomarkers comprising PERSEVERE-II, we found higher levels of ANG2, a marker of endothelial damage, and of sTM and PAI1, markers of dysregulated coagulation, in nonsurvivors. These three biomarkers have predicted mortality in other sepsis cohorts (32–34) and mechanistically could plausibly contribute to worsening organ failures and death. Indeed, the respective implicated pathways of the endothelium and coagulation systems are linked, with damage in one contributing to dysregulation in the other (35). A very recent revision of PERSEVERE-II incorporating ANG2, its antagonist ANG1, and their shared receptor (tyrosine kinase with immunoglobin and EGF homology domains 2) was shown to improve prognostic performance in a large cohort of septic children from the United States (22). Thus, interventions to stabilize the endothelium and target the coagulopathy of sepsis may also be translatable to septic children in Pakistan. Our data also suggest the potential to further improve the performance of future sepsis prognostic models in this cohort, particularly with an incorporation of markers of endothelial dysfunction.

We also showed higher levels of sRAGE and SPD in subjects with PARDS, suggesting that markers of alveolar epithelial damage can identify subjects with significant lung injury in this cohort. While sRAGE expression is ubiquitous (36–38), levels are highest in type I alveolar epithelia (24, 39), and elevated sRAGE has been reported in adult and pediatric ARDS, with higher levels in nonsurvivors. SPD is expressed in type II alveolar epithelia (25, 40), with elevated levels in direct ARDS reflecting epithelial barrier disruption. Overall, our results preliminarily suggest that the molecular phenotype of PARDS, a syndrome related to sepsis, may also be similar to what has been reported in pediatric and adult ARDS cohorts from high-income countries. Thus, biomarker-based risk stratification and endotyping strategies in PARDS developed in high-income countries may also generalize to children in lower income countries.

Our study has several limitations. Subjects were recruited from a single center, and generalizability to other centers in Pakistan, Southeast Asia, or other LMICs cannot be assumed. The intrinsic heterogeneity of sepsis, and treatments specific to AKUH, could plausibly impact biomarker levels and thus affect performance of any biomarker-based risk prediction tool. The overall sample size was small, although the largest reported to date in pediatric sepsis from Pakistan. Samples were collected only at a single time point and the longitudinal trajectory of these biomarkers, or the longitudinal stability of PERSEVERE-II, remains unknown. While we used a modified definition for sepsis and an established definition for PARDS, clinical syndromes subjects to misclassification when making assignments in real-time. Biomarkers were measured after being shipped to the opposite side of the globe without comparison of biomarker levels before and after shipping, and we cannot exclude any errors during handling. However, we would expect this to bias results toward the null. Our study also has several strengths. We prospectively enrolled subjects with in order to test a specific risk stratification tool. Blood was collected within 24 hours of PICU admission, minimizing the impact of interventions on biomarker levels, and thus ensuring that plasma was reflective primarily of underlying mortality risk. Biomarkers were measured by institutions familiar with these assays, and this study represents a strong and ongoing collaboration between lower and higher income countries to advance pediatric critical care.

PERSEVERE-II, a biomarker-based risk stratification tool for pediatric sepsis developed in the United States, performs well in a cohort from AKUH in Pakistan, with an AUROC for discriminating 28-day mortality of 0.83. This is the first validation of PERSEVERE-II in a low-middle-income country. ANG2, sTM, and PAI1 were elevated in sepsis nonsurvivors, and sRAGE and SPD elevated in subjects with PARDS, suggesting a biomarker profile comparable to that of sepsis and PARDS from high-income countries. Biomarker-based risk stratification and subphenotyping strategies for critical illness syndromes developed in high-income countries may generalize to lower income countries with higher mortality.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

*See also p. 619.

Drs. Ishaque, Faisal Saleem, Thomas, and Yehya conceived of the study. Mr. Famularo, Dr. Siddiqui, and Ms. Kazi assisted with acquisition of the data. Dr. Parkar and Ms. Hotwani collected and organized the data. Ms. Thompson, Mr. Lahni, and Dr. Varisco analyzed the data.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/pccmjournal).

Supported, in part, by a grant from R01-HL148054 (to Dr. Yehya).

Drs. Famularo’s, Kazi’s, Parkar’s, Thompson’s, and Yehya’s institutions received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Drs. Kazi, Parkar, Thompson, and Yehya received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health. Drs. Parkar’s and Yehya’s institutions received funding from Pfizer outside of the scope of this work. Dr. Thomas received funding from Bayer AG. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. : The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016; 315:801–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, et al. : Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990-2017: Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020; 395:200–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleischmann-Struzek C, Goldfarb DM, Schlattmann P, et al. : The global burden of paediatric and neonatal sepsis: A systematic review. Lancet Respir Med. 2018; 6:223–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL, et al. ; Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group of WHO and UNICEF: Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: A systematic analysis. Lancet. 2010; 375:1969–1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. : Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000-13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: An updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015; 385:430–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss SL, Fitzgerald JC, Pappachan J, et al. ; Sepsis Prevalence, Outcomes, and Therapies (SPROUT) Study Investigators and Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network: Global epidemiology of pediatric severe sepsis: The sepsis prevalence, outcomes, and therapies study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015; 191:1147–1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikacenic C, Price BL, Harju-Baker S, et al. : A two-biomarker model predicts mortality in the critically ill with sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017; 196:1004–1011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scicluna BP, van Vught LA, Zwinderman AH, et al. ; MARS consortium: Classification of patients with sepsis according to blood genomic endotype: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2017; 5:816–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sweeney TE, Perumal TM, Henao R, et al. : A community approach to mortality prediction in sepsis via gene expression analysis. Nat Commun. 2018; 9:694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML, et al. ; Sepsis Definitions Task Force: Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: For the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016; 315:775–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seymour CW, Kennedy JN, Wang S, et al. : Derivation, validation, and potential treatment implications of novel clinical phenotypes for sepsis. JAMA. 2019; 321:2003–2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwashyna TJ, Burke JF, Sussman JB, et al. : Implications of heterogeneity of treatment effect for reporting and analysis of randomized trials in critical care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015; 192:1045–1051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harhay MO, Casey JD, Clement M, et al. : Contemporary strategies to improve clinical trial design for critical care research: Insights from the First Critical Care Clinical Trialists Workshop. Intensive Care Med. 2020; 46:930–942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong HR, Salisbury S, Xiao Q, et al. : The pediatric sepsis biomarker risk model. Crit Care. 2012; 16:R174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong HR, Cvijanovich NZ, Anas N, et al. : Pediatric sepsis biomarker risk model-II: Redefining the pediatric sepsis biomarker risk model with septic shock phenotype. Crit Care Med. 2016; 44:2010–2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calfee CS, Delucchi KL, Sinha P, et al. ; Irish Critical Care Trials Group: Acute respiratory distress syndrome subphenotypes and differential response to simvastatin: Secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2018; 6:691–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinha P, Delucchi KL, Thompson BT, et al. ; NHLBI ARDS Network: Latent class analysis of ARDS subphenotypes: A secondary analysis of the statins for acutely injured lungs from sepsis (SAILS) study. Intensive Care Med. 2018; 44:1859–1869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sinha P, Calfee CS, Delucchi KL: Practitioner’s guide to latent class analysis: Methodological considerations and common pitfalls. Crit Care Med. 2021; 49:e63–e79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinha P, Delucchi KL, Chen Y, et al. : Latent class analysis-derived subphenotypes are generalisable to observational cohorts of acute respiratory distress syndrome: A prospective study. Thorax. 2022; 77:13–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prescott HC, Calfee CS, Thompson BT, et al. : Toward smarter lumping and smarter splitting: Rethinking strategies for sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome clinical trial design. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016; 194:147–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong HR, Caldwell JT, Cvijanovich NZ, et al. : Prospective clinical testing and experimental validation of the Pediatric Sepsis Biomarker Risk Model. Sci Transl Med. 2019; 11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atreya MR, Cvijanovich NZ, Fitzgerald JC, et al. : Integrated PERSEVERE and endothelial biomarker risk model predicts death and persistent MODS in pediatric septic shock: A secondary analysis of a prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2022; 26:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Auriemma CL, Zhuo H, Delucchi K, et al. : Acute respiratory distress syndrome-attributable mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2020; 46:1222–1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uchida T, Shirasawa M, Ware LB, et al. : Receptor for advanced glycation end-products is a marker of type I cell injury in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006; 173:1008–1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisner MD, Parsons P, Matthay MA, et al. ; Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network: Plasma surfactant protein levels and clinical outcomes in patients with acute lung injury. Thorax. 2003; 58:983–988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matics TJ, Sanchez-Pinto LN: Adaptation and validation of a pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score and evaluation of the Sepsis-3 definitions in critically ill children. JAMA Pediatr. 2017; 171:e172352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference Group: Pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome: Consensus recommendations from the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015; 16:428–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leteurtre S, Duhamel A, Salleron J, et al. ; Groupe Francophone de Réanimation et d’Urgences Pédiatriques (GFRUP): PELOD-2: An update of the PEdiatric logistic organ dysfunction score. Crit Care Med. 2013; 41:1761–1773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaies MG, Gurney JG, Yen AH, et al. : Vasoactive-inotropic score as a predictor of morbidity and mortality in infants after cardiopulmonary bypass. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010; 11:234–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yehya N, Harhay MO, Klein MJ, et al. ; Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Incidence and Epidemiology (PARDIE) V1 Investigators and the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network: Predicting mortality in children with pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome: A pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome incidence and epidemiology study. Crit Care Med. 2020; 48:e514–e522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karim F, Adil SN, Afaq B, et al. : Deficiency of ADAMTS-13 in pediatric patients with severe sepsis and impact on in-hospital mortality. BMC Pediatr. 2013; 13:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ricciuto DR, dos Santos CC, Hawkes M, et al. : Angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-2 as clinically informative prognostic biomarkers of morbidity and mortality in severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2011; 39:702–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin JJ, Hsiao HJ, Chan OW, et al. : Increased serum thrombomodulin level is associated with disease severity and mortality in pediatric sepsis. PLoS One. 2017; 12:e0182324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tipoe TL, Wu WKK, Chung L, et al. : Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 for predicting sepsis severity and mortality outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Immunol. 2018; 9:1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu WK, McNeil JB, Wickersham NE, et al. : Angiopoietin-2 outperforms other endothelial biomarkers associated with severe acute kidney injury in patients with severe sepsis and respiratory failure. Crit Care. 2021; 25:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jabaudon M, Futier E, Roszyk L, et al. : Soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation end products is a marker of acute lung injury but not of severe sepsis in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2011; 39:480–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones TK, Feng R, Kerchberger VE, et al. : Plasma sRAGE acts as a genetically regulated causal intermediate in sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020; 201:47–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim MJ, Zinter MS, Chen L, et al. : Beyond the alveolar epithelium: Plasma soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products is associated with oxygenation impairment, mortality, and extrapulmonary organ failure in children with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2022; 50:837–847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jabaudon M, Blondonnet R, Roszyk L, et al. : Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products predicts impaired alveolar fluid clearance in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015; 192:191–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dahmer MK, Flori H, Sapru A, et al. ; BALI and RESTORE Study Investigators and Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network: Surfactant protein D is associated with severe pediatric ARDS, prolonged ventilation, and death in children with acute respiratory failure. Chest. 2020; 158:1027–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.