Abstract

The high incidence of HIV among US Black sexual minority men is a public health crisis that pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV can help address. Public health campaigns, which often include pictures of Black sexual minority men alongside PrEP-related messaging, have been developed to encourage PrEP awareness and uptake. However, the acceptability of the messaging within these campaigns among Black sexual minority men is unclear. We conducted four focus groups with 18 HIV-negative Black sexual minority men in Washington, DC to explore their perspectives regarding promotional messaging (textual elements) in PrEP visual advertisements, including their reactions to three large-scale public health campaigns. Primary themes included: (1) the need for additional information about PrEP, (2) preference for slogan simplicity, (3) the desire to normalise PrEP use, and (4) mixed views on the inclusion of condoms. Results indicated that the messaging in current PrEP visual advertisements may not sufficiently address Black sexual minority men’s questions about PrEP. Providing basic PrEP information and methods to access more information; using simple, unambiguous language; presenting PrEP use in a destigmatising, normalising fashion; and conveying the relevance of condoms if included in the advertisement could help increase the acceptability of future PrEP advertising among Black sexual minority men.

Keywords: HIV, pre-exposure prophylaxis, Black sexual minority men, sexual and gender minorities, social marketing

Introduction

The disproportionately high incidence of HIV among US Black sexual minority men—particularly Black sexual minority men in Washington, DC—signals an urgent public health crisis. Black sexual minority men accounted for 34% of new HIV diagnoses in Washington, DC, between 2016–2020 despite representing less than 1% of the population in Washington, DC. By contrast, White sexual minority men and Black heterosexual men each accounted for only 9% of new diagnoses in Washington, DC (District of Columbia Department of Health, HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis, STD and TB Administration 2021). Nationwide statistics further illustrate this high HIV incidence, where Black sexual minority men accounted for 32% of new HIV diagnoses in the USA in 2019 (CDC 2021a).

Although HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is an effective preventive measure that reduces the likelihood of HIV acquisition by over 99% (CDC, 2021b), PrEP prescription has been low overall (AVAC 2022). PrEP prescription has been particularly low among Black sexual minority men, who are less likely to be aware of PrEP, discuss PrEP with a health provider, or initiate PrEP following discussion with a provider compared with their White counterparts (Kanny et al. 2019). Understanding Black sexual minority men’s preferences related to messaging included in PrEP advertisements and identifying strategies to improve PrEP awareness, acceptability and access among Black sexual minority men is essential to help reduce the rate of HIV infection among this population and to end the HIV epidemic in accordance with local and national initiatives (District of Columbia Department of Health 2020; US Department of Health and Human Services 2019).

Social marketing is a commonly used technique designed to increase individual knowledge and facilitate adaptive behaviour change (Wymer 2011). Social marketing has been documented as a prominent technique within public health (Helmig and Thaler 2010), impacting awareness and uptake for a range of preventive health products and behaviours, including condoms (Bull et al. 2008) and smoking cessation (Naslund et al. 2017).

Public health campaigns have been developed to encourage PrEP awareness and access, and many have sought to reach Black sexual minority men specifically. For example, Chicago’s PrEP4Love campaign, which features images of sexual and gender minorities of colour alongside sex-positive messaging, has reached millions of viewers (Dehlin et al. 2019). However, research to date on the acceptability and effectiveness of existing campaigns is sparse and has yielded mixed findings. One study found that reported exposure to the PrEP4Love campaign was positively associated with perceptions of community support for PrEP and with PrEP uptake among a racially diverse sample of young sexual minority men and transgender women (Phillips et al. 2020). However, some members of the Chicago community perceived the same campaign to be stigmatising (and thus unacceptable), singling out Black Americans from other racial groups and associating them with HIV, a socially devalued condition (Keene et al. 2021). Similar concerns about the potential stigmatising effect of a selective focus on Black sexual minority men and other minority groups in PrEP visual advertising campaigns have been expressed by others (Amico and Bekker 2019; Calabrese et al. 2020; Rogers et al. 2019; Thomann et al. 2018). Greater insight into Black sexual minority men’s perspectives on such campaigns and the effect of viewing such campaigns on Black sexual minority men’s subsequent PrEP use is critical for maximising future campaign impact.

To date, the majority of research related to the acceptability of PrEP campaigns has focused on the visual elements within advertisements (e.g. the people in the advertisement; Calabrese et al. 2020; Keene et al. 2021), with minimal discussion of the textual elements. Those studies that have considered textual content within PrEP advertisements have found that sexual and gender minority viewers recommended incorporating clear, specific and fact-driven messaging, including basic information (e.g. that PrEP prevents HIV) to ensure that people unaware of PrEP understand the messaging (Goedel et al. 2021; Nakelsky, Moore and Garland 2022). Newly diagnosed young Black sexual minority men also recommended normalising PrEP use and including testimonials in PrEP advertisements (Elopre et al. 2021). A qualitative study with lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer/questioning youth of colour eliciting questions and concerns related to PrEP suggested that providing information about what PrEP is, the side effects of PrEP and how to access PrEP could be valuable (Golub, Meyers and Enemchukwu 2020). Finally, several messaging trials involving textual content only (absent accompanying visual imagery) have considered the impact of specific message content and frames on attitudes and intentions related to PrEP and other forms of prevention (Foley et al. 2021; Mustanski et al. 2014; Underhill et al. 2018). For example, one study found that framing content related to condoms as flexible in PrEP messaging (e.g. “You can enhance your protection by using safety strategies like condoms during sex”) versus inflexible (e.g. “You should still use safety strategies like condoms during sex”) had no significant effect on willingness to use PrEP among a primarily White sample of sexual minority men (Underhill et al. 2018). Though offering valuable preliminary insight, it remains unclear whether these early findings translate to Black sexual minority men’s reactions to the textual content within real-world PrEP visual advertisements.

Further research is needed to better understand Black sexual minority men’s perceptions and preferences related to textual elements within visual advertisements, which are essential to the overall acceptability of the advertisements and their effectiveness in promoting PrEP information-seeking and use. The purpose of this qualitative focus group study was to explore perspectives and recommendations regarding textual elements of PrEP visual advertisements among HIV-negative Black sexual minority men living in the Washington, DC/Baltimore metro area to inform future public health campaigns.

Method

Participants

Black sexual minority men (n = 18) were recruited to participate in the study through dating apps, social media and participant referral. Eligibility criteria included English language literacy, self-identifying as a man and as Black/African American, being age 18 or older, having an HIV-negative or unknown HIV status and having had anal sex with another man in the past 12 months. Focus group participants were identified through purposeful sampling. Purposeful sampling is a commonly used strategy involving the selection of individuals who can provide rich information about the phenomenon under study due to their relevant knowledge or experience (Creswell 2015; Palinkas et al. 2015). We included both current PrEP users and non-users given that these two groups offered unique viewpoints. For example, whereas PrEP users could reflect upon whether advertisements resonated with their own PrEP experience and motivated persistence, PrEP non-users could offer insight about how advertisements could enhance their motivation to initiate PrEP in the future.

Procedure

All study procedures were approved by George Washington University’s institutional review board prior to inception (IRB #031752). Data were collected as part of a larger mixed-methods project aimed at evaluating the acceptability and effectiveness of PrEP social marketing materials among Black sexual minority men. The principal investigator of this project (SKC), who was previously trained in qualitative research methods, supervised two research assistants (SR and DM) who facilitated four 90-minute, semi-structured focus groups (3–5 participants each) in Washington, DC, in 2019.1 This semi-structured format included lead questions and follow-up prompts. Participants provided pseudonyms to help maintain confidentiality. Saturation was evaluated through the inductive thematic saturation model, which considers the emergence of new codes or themes (Saunders et al. 2018). We concluded that saturation was achieved when no new themes were identified in the fourth focus group.

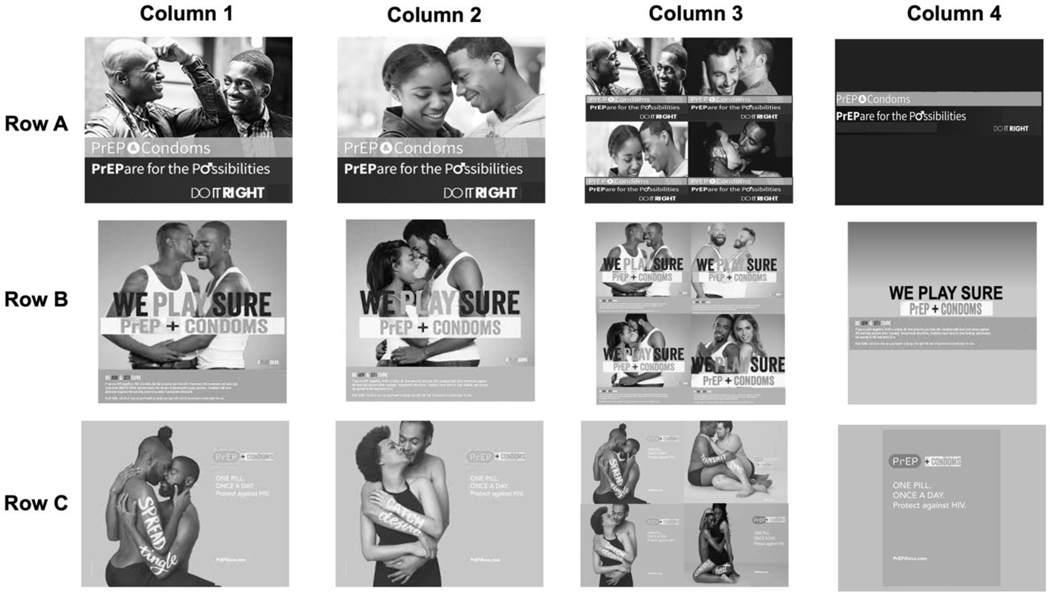

At the outset of the focus group, a brief, scripted overview of PrEP was read to ensure that all participants had a general understanding of PrEP, its effectiveness and the potential side effects. Participants were then asked to describe how they would design a PrEP advertisement, to discuss preferred imagery and to share their perspective on targeting PrEP advertisements to sexual minority men. Subsequently, all participants viewed a 3 × 4 grid of PrEP social marketing images, adapted from Washington, DC’s “PrEPare for Possibilities,” New York City’s “We Play Sure,” and Chicago’s “PrEP4Love” advertisement campaigns.

The advertisements were modified in several ways to eliminate variables that could impact their relative acceptability. For example, city names were covered up in all advertisements, messages about condoms were added to the ads in which they were not previously mentioned (so that condoms were mentioned in all ads) and advertisements were all presented in black and white. Rows varied by campaign, and columns varied by the composition of couples presented (Black sexual minority men couple, Black heterosexual couple, diversity of couples, no couples). An example grid is presented in Figure 1. All groups reviewed the same 12 images, but the ordering of campaigns and couple compositions presented in the grid varied across groups (e.g. the PrEP4Love campaign was in Row C for the first focus group and Row A for the third). Each focus group viewed a unique variation of the grid to eliminate the possibility that the order/position of the ads systematically impacted participant reactions. Some focus group participants were previously exposed to one or more of the same visual stimuli because they participated in an earlier survey phase of the study (Calabrese et al. 2020).

Figure 1.

Focus Group Advertisement Images

Questions in the guide were structured to promote discussion about the positive and negative aspects of the advertisements. Questions aimed to assess the acceptability of the advertisements to participants (e.g. “Is there anything about these ads that you find particularly appealing?”, “Is there anything that bothers you about any of the ads?”), participants’ comprehension of the advertisements (e.g. “Are any of these ads easier to understand than others? Why?”), participants’ perceived relatability to the ads (e.g. “To what extent do you feel like you could relate to these ads?”) and the impact of the ads on PrEP attitudes and intentions (e.g. “What questions about PrEP come to mind after seeing these ads, if any?”, “Do any of these ads make you more or less inclined to talk to a healthcare provider about PrEP?”). Participants were also asked to make direct comparisons across ads (e.g. “Which ad is your favourite? Why?”) A specific prompt was added to generate discussion about the inclusion of condoms within PrEP advertisements after the discussion occurred naturally in the first focus group.

Participants additionally completed a brief questionnaire before the focus group. The questionnaire assessed sociodemographic characteristics, HIV status, recent sexual behaviour, recent health service utilisation, prior awareness of PrEP, and PrEP usage. Participants received $40 in cash as compensation and were provided with reimbursement for transportation, an HIV prevention resource packet, and referrals for PrEP providers and HIV care at the conclusion of each focus group discussion.

Analysis

Focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were then imported into NVivo 11 for analysis. The Framework Method was utilised to assist in data organisation, summarisation, and identification of relevant themes through a systematic review of the textual data. This method consists of seven steps including transcription, familiarisation with the data, coding, development of a working analytical framework, framework application, data charting and interpretation (Gale et al. 2013).

One co-author who was not involved with the facilitation of the focus groups (DAK) constructed the initial draft of the analytic framework in consultation with the principal investigator (SKC). The analytic framework contained codes to appropriately define the emerging concepts from the focus groups, which were organised within broader categories. This initial draft of the analytic framework was refined through an iterative process, where two co-authors (DAK and SR) independently coded transcripts, and then discussed, revised, and added new codes when applicable. This collaborative process helped ensure that all newly emergent themes were identified and incorporated into the analytic framework. The final multi-level framework was used by DAK and SR to code all transcripts, with two transcripts double-coded to establish interrater reliability. DAK reviewed coded text by using NVivo’s matrix coding/query functions. Once coding was finalised, DAK read each of the transcribed focus group discussions and charted the textual data relevant to this study. In consultation with the principal investigator (SKC), DAK and SR used the charted textual data to interpret the data, to identify and organise themes, and to select illustrative quotes, which are presented within the Results section following.

Reflexivity

Reflexivity refers to researchers’ self-reflection on how their personal backgrounds and beliefs may have impacted the study’s design or the identified themes and interpretations from the data (Creswell and Creswell 2018). The research team for this study was led by a White, cisgender, heterosexual woman with a doctorate in psychology. All focus groups were co-facilitated by a White, genderqueer/genderfluid man who is sexually attracted to other men and a South Asian, cisgender, queer woman. Coding and data analysis were led by a White, cisgender, gay man and a South Asian, cisgender, queer woman. Cofacilitators and coders were doctoral students in a clinical psychology programme. Overall, the research team included racially and sexually diverse researchers from a variety of disciplines (e.g. psychology, public health, medicine) that had experience conducting HIV prevention research with Black sexual minority men. The members of the research team had background knowledge about PrEP and identified barriers to PrEP implementation and entered into the research with a shared belief that people should have access to and be informed about PrEP. While this background knowledge and belief about PrEP informed the research team’s conceptualisation of the project, the research team refrained from sharing such beliefs with participants to avoid impacting their responses. The focus groups were conducted as part of a larger mixed-methods project that evaluated Black sexual minority men’s perspectives on the acceptability and effectiveness of PrEP social marketing materials.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Participants were 18 Black HIV-negative sexual minority men, who ranged in age from 22 to 62 years [M(SD)=34(10.3)]. The majority of participants identified as non-Latino/x (89%), identified as gay (61%) and were born in the USA (89%). Most participants reported having anal sex with another man in the past six months (83%), of whom 87% indicated having condomless anal sex. Most participants had previously heard of PrEP prior to participating in this focus group study (88%). About half of the participants had ever taken PrEP (47%) and 35% of participants indicated that they were currently taking PrEP. Additional descriptive information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| N=18 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| N | % | ||

| Gendera | |||

| Male | 17 | 94.44 | |

| Genderqueer | 1 | 5.56 | |

| Racea | |||

| Black/African American | 17 | 94.44 | |

| Multiracial | 1 | 5.56 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Latino/x | 2 | 11.11 | |

| Non-Latino/x | 16 | 88.89 | |

| Place of Birth | |||

| United States | 16 | 88.89 | |

| Caribbean | 1 | 5.56 | |

| Africa | 1 | 5.56 | |

| Sexual Orientation | |||

| Gay | 11 | 61.11 | |

| Bisexual | 7 | 38.89 | |

| Condomless Anal Sex with Another Man in the Past 6 Months | |||

| Yes | 13 | 72.22 | |

| No | 5 | 27.78 | |

| Most Recent Physical or Mental Health Service Utilisation | |||

| 0–3 months ago | 10 | 55.56 | |

| 4–6 months ago | 3 | 16.67 | |

| 7–12 months ago | 1 | 5.56 | |

| >12 months ago | 4 | 22.22 | |

| Prior PrEP Awarenessb | |||

| Yes | 15 | 88.24 | |

| No | 1 | 5.88 | |

| Don’t know | 1 | 5.88 | |

| PrEP Useb,c | |||

| Present use | 6 | 35.29 | |

| Past use only | 2 | 11.76 | |

| Never | 9 | 52.94 | |

During original eligibility screening, consistent with eligibility criteria, all participants reported identifying as men and Black or African American. Characteristics reported here are based on questionnaires completed at the time of focus group participation.

n = 17 for these variables

Only those participants who reported prior PrEP awareness were subsequently asked to report use. Participants who reported no or unknown prior PrEP awareness were assumed to not use PrEP.

Themes

Thematic analysis using the Framework Method described above guided the interpretation of the charted textual data and the organisation of the data into relevant themes. We identified themes related to a need for additional information about PrEP, a preference for slogan simplicity, a desire to normalise PrEP use within PrEP visual advertisements, and mixed preferences for the inclusion of condoms within PrEP visual advertisements.

Need for Additional Information about PrEP

A majority of participants felt as though the text within the advertisements left them with many unanswered questions about PrEP. One of the most commonly referenced concerns about the PrEP advertisements shown was the lack of information about the potential side effects of using PrEP. Many participants indicated that they would have preferred advertisements that included information about side effects as well as effectiveness:

I feel like there’s degrees of vagueness in all these, and although Row C [PrEP4Love advertisements] has more information… Like for me, I want more information than like one pill once a day. I would need to know like what the success rate is, I would need to know what the side effects are, um, to know like what’s it doing to my liver. Um, so I would need way more information than all these are giving me. Um, and I don’t know like how to frame that in an advertisement but it’s definitely worth considering because there are people like me who will see that, and it will just wash over them. [FG2]

Another participant echoed this sentiment, suggesting that a lack of basic information could limit understanding of the advertisement’s meaning for those who are not already familiar with PrEP:

I think that there are some assumptions that you have a base understanding of what PrEP is, which I don’t know if everyone who is sexually active in this way would. [FG3]

Multiple participants suggested incorporating methods to find additional information about PrEP, and this suggestion was met with broad support from other participants. One participant acknowledged limits to the amount of information that could be captured in a single advertisement and suggested using a QR code as a possible mechanism for providing people with this additional information:

Since these are like ads that you’re going to see at bus stops and, uh, online and places like that, it’s kinda tough to like, uh, give – go into further detail… which is why I really think that QR codes should be added so people can check on their phones quickly. [FG2]

Aside from QR codes, participants recommended including websites (which were visible in some of the advertisements in the 3 × 4 grid of advertisements presented) and phone numbers (which were present but indiscernible in some of the advertisements given their reduced size) to provide viewers with access to more information about PrEP:

I like a website. We’re working adults, for the most part, most of us, and sometimes it’s just easier to kinda click around on the Web when I have a free moment and I can get away or – or, you know, in bed or on my iPad or somethin’ like that. So, a website is definitely a positive. [FG3]

Other participants recommended including text advising viewers to talk to a health provider to learn more about PrEP:

I would look at it and I would say, okay, like, this is something I would like, you know, I could be interested in but it doesn’t tell me what I need to do next. So, like – So, just like the quick steps, like… find a clinic, talk to a doctor, get a test. Uh, so I mean it doesn’t – it changes my mind at, like, it makes it relatable and it makes me think about being open to it, but then it doesn’t make me do action because I – it doesn’t tell me what I would need to do. [FG1]

Preference for Slogan Simplicity

While the majority of participants wanted the advertisements to contain more information about PrEP, participants appreciated the value of having simple messaging. As one participant explained:

It applies to the KISS method, which is keep it, um, keep it short and simple… one pill a day protects [against] HIV, that like pump and play, it just goes straight to the point right there. [FG1]

Despite this preference for message simplicity, participants believed that the current attempts at messaging simplicity sometimes missed the mark:

My general take is, um… to be careful with, uh, slogans. Even though slogans can, like, work really well. When they’re off, they have a certain disconnect. [FG2]

Nearly all of the participants in one focus group, in particular, reacted unfavourably to what they perceived to be ambiguous messaging in the PrEP advertisements:

I don’t really like any of ‘em… I don’t like the wor – I mean, I get what they’re tryin’ to do, but, like, spread, transmit, catch are not words that make me feel like I wanna be intimate with that person. So, like, I get they’re, like, tryin’ to say, like, ‘Oh, instead of catching HIV, transmit love,’ but I don’t know. It doesn’t [get] me there. [FG3]

Yeah, I’m confused by some for – what the hell is contract heat?... Just the words are weird. Like, I don’t know what contract heat is supposed to mean. [FG3]

Accordingly, this participant described a preference for a clearer, simpler slogan to mitigate the concerns about the ambiguity of slogans within the advertisements:

So I gravitate more towards like just the simple English, like ‘Prepare for the Possibilities.’ [FG2]

Desire to Normalise PrEP Use

When questioned about the content that should be included in PrEP advertisements, prior to viewing the existing PrEP advertisements, many participants recommended slogans that would normalise PrEP use. One participant suggested the slogan ‘gym, tan, PrEP’—referencing the ‘gym, tan, laundry’ mantra embraced by characters on ‘The Jersey Shore’ television show—to present PrEP as a part of people’s everyday routine:

The gym, tan, PrEP. Like something that like will like stand out to people and it kinda shows it’s like in the daily regimen of things. Or like an ad that has like a toothbrush, a stick – a bar of soap and like your PrEP pill. [FG2]

Multiple participants suggested comparing it to a multivitamin, which could decrease the stigma associated with PrEP use:

I think that’s compelling… like, anything that talks about or shows the ease of use just of taking, like, a pill once a day, like a multivitamin. I think makes it like it can just be part of a very easy daily routine. [FG3]

The negative connotation is, you know, PrEP is just for people who wanna be, uh, promiscuous or whoring around. And that way, if you have an advertisement that’s, you know, making it seem like it’s a vitamin or just a one-a-day kinda thing, then it would take away that negative connotation. [FG4]

Mixed Views on Including Messaging about Condoms

Participants held differing perspectives about whether condoms should be included within PrEP advertisements. Many opposed the inclusion of condoms, endorsing the belief that ‘If you’re gonna advertise PrEP, then advertise PrEP, and then just do that… adding in condoms, uh, that’s a separate – that’s somethin’ totally different. [FG3]’ Participants highlighted multiple ways in which the inclusion of condoms could confuse viewers of the advertisement. For example, one participant explained how inclusion of condoms in the advertisements could imply that PrEP must be used with condoms and foster confusion about the added value that PrEP offers:

It just sorta hit me that every single one of these ads has PrEP plus condoms. And I think just the average person on the street would– might ask, well, what’s the point of taking a pill every day if I still have to use condoms when, you know, condoms are inexpensive, there are no side effects like taking a drug every day. So, I think maybe someone might ask what would be the point of it, uh, when condoms can be just as effective to prevent HIV as, uh, as taking a pill. [FG2]

One participant pointed out that the pairing of PrEP and condoms could foster doubts not only about the protective value of PrEP, but also about the protective value of condoms:

It’s makin’ me question whether condoms were ever enough to protect yourself. That’s the only thing that I’m thinkin’ about when I see these. [FG4]

While many participants opposed the inclusion of condoms within PrEP advertisements, there were also a similar number of participants strongly supporting their inclusion. Supporters believed that the inclusion of condoms in advertisements could avoid the public misperception that PrEP protects against STIs other than HIV:

I think it’s dangerous when you advertise PrEP but don’t advertise condoms. Because what you don’t want is for people to think that they can take this pill, it’ll prevent HIV and everything else because it won’t prevent everything else, it’ll only prevent HIV. [FG2]

One participant also pointed out that adding information about STIs could help to avoid confusion or unanswered questions arising from the inclusion of condoms in PrEP ads:

If you’re gonna talk about condoms… you need to mention somethin’ about STDs. You can’t just say, ‘Oh, yeah, with a condom, too.’ [FG3]

Some proponents of joint messaging about PrEP and condoms viewed the advertisements as demonstrating the multiple options people have for HIV/STI prevention:

I think of it like a toolbox, right? Like, you got different tools. PrEP – PrEP’s one. Condom’s another. I don’t have any problem with condoms being added. Like, it doesn’t confuse me. [FG3]

Discussion

To our knowledge, there are no prior studies that focus on Black sexual minority men’s perspectives on the textual elements of PrEP visual advertisements in existing public health campaigns. By identifying such perspectives, public health campaigns can tailor the content of future PrEP advertisements to better reflect the content that Black sexual minority men view as important to include, which could aid in increasing PrEP awareness and PrEP uptake among Black sexual minority men. In this study involving Black sexual minority men living in the Washington, DC/Baltimore metro area, primary themes that emerged included: (1) the need for additional information about PrEP, (2) preference for slogan simplicity, (3) the desire to normalise PrEP use, and (4) mixed views on the inclusion of condoms within PrEP visual advertisements.

One of the most common critiques of the current PrEP visual advertisements was the lack of information provided regarding the purpose of PrEP. Similar to previous studies evaluating perceptions of PrEP, concerns about side effects, efficacy and other basic information about PrEP were evident (Cahill et al. 2017; Golub, Meyers and Enemchukwu 2020; Young and McDaid 2014). Participants believed that providing this information was essential for ensuring understanding of the advertisements and cultivating interest in PrEP among viewers. In particular, some participants cautioned that neglecting to provide basic information about PrEP in these advertisements assumes that people already have such knowledge and alienates those who do not. Black sexual minority men appeared to be a key audience targeted by these particular campaigns; although awareness about PrEP is growing and relatively high in urban areas, many Black sexual minority men remain unaware of PrEP (Kanny et al. 2019; Russ, Zhang and Liu 2021). To the extent that one of the goals of PrEP social marketing is to raise awareness about PrEP, inclusion of basic information is essential. Study findings indicate that the messaging included in current PrEP visual advertisements may not sufficiently address the basic questions Black sexual minority men and others have about PrEP, suggesting future adjustments to messaging are needed.

Despite their interest in receiving more information about PrEP, participants recognised the challenge of providing comprehensive information within these advertisements. To mitigate this challenge, some participants recommended including QR codes, websites, and/or phone numbers on the advertisement to provide viewers with a mechanism to address any further questions they may have about PrEP and pursue a PrEP prescription. While none of the advertisements from the three campaigns presented to participants included QR codes, all three campaigns included websites and one (‘We Play Sure’) included a phone number in the original versions of the advertisements presented to the public. (This information was not readily discernible in all of the modified stimuli presented to participants.) Including mechanisms within PrEP advertisements for viewers to learn more about PrEP allows viewers to access more thorough information about PrEP even when they are no longer viewing the advertisement. Additionally, it is important to incorporate methods for advertisement viewers to access information about PrEP from reliable sources considering medical mistrust can deter Black sexual minority men from accessing healthcare (Cahill et al. 2017) and, thus, accessing information about PrEP within healthcare settings.

Another critique shared by the majority of the participants was that the textual elements within the current advertisements, particularly the slogans, were confusing and sometimes off-putting. For example, several of the participants did not understand the meaning of the slogans (e.g. ‘contract heat’), particularly in the absence of accompanying information about PrEP. Although there was criticism over the word choices within these advertisements, participants universally appreciated that the advertisements utilised simple messaging. Additional research evaluating sexual minority men’s perspectives regarding PrEP visual advertisements also identified that direct and simple messaging was an important element to motivate engagement with advertisements (Goedel et al. 2021; Nakelsky, Moore and Garland 2022). Identifying strategies to increase engagement with PrEP advertisements is particularly important considering that viewing PrEP advertisements has been associated with being out to providers and with taking PrEP within a six-month period after viewing the advertisement (Phillips et al. 2020). Therefore, future public health campaigns may be more effective in engaging viewers and increasing PrEP uptake by choosing messaging that is considered to be both direct and simple.

Many participants wanted the PrEP advertisements to normalise PrEP use, which emerged as a prominent theme even prior to viewing the advertisements in this study. For example, one recommendation to normalise PrEP use with text in PrEP visual advertisements included equating PrEP use to taking a multivitamin, which would be a method of showcasing PrEP use in a less stigmatising fashion than presenting it in a sexual context. Previous literature addressing PrEP stigma as a barrier to PrEP uptake has also encouraged normalising PrEP use by presenting PrEP as a routine method of healthcare (Calabrese 2020; Golub and Myers 2019). Specific recommendations to normalise PrEP use include using ‘options counselling’ (in which PrEP is discussed as part of broader conversations about sexual health in conjunction with other preventive measures), discussing PrEP with all patients as a form of routine preventive care, and integrating PrEP services in a variety of health settings (Calabrese 2020; Golub and Myers 2019). Based on our study’s findings, researchers and public health officials should prioritise evaluating different approaches to normalising PrEP use that can be implemented in future public health campaigns, which could increase the acceptability of PrEP advertisements. Identifying these effective strategies to normalise PrEP use is essential in the effort to destigmatise PrEP use and increase uptake among anyone who could benefit from PrEP, including Black sexual minority men. It is also important that future research further explores Black sexual minority men’s preferences related to sexualised advertisement content, and whether normalising PrEP by relating it to a non-sexual, routine health behaviour (taking a daily vitamin) could help to counter sexual stereotypes of PrEP users.

Participants reported conflicting views about the inclusion of condoms within PrEP visual advertisements. Supporters of condom inclusion were primarily concerned with avoiding misperceptions that PrEP protects against STIs other than HIV. Supporters additionally mentioned that joint messaging about PrEP and condoms highlights the diversity of prevention options available. Opponents of including condoms in PrEP advertisements discussed how doing so could confuse viewers. For example, whereas sexual minority men in previous research have reported concerns that prospective PrEP users will perceive condom use as unnecessary while taking PrEP (Mimiaga et al. 2016; Thomann et al. 2018), our participants reported concerns that prospective PrEP users will perceive condom use as necessary while taking PrEP. These opponents of condom inclusion suggested that including condoms could foster doubts about the effectiveness of both PrEP and condoms as standalone safety strategies. Research on consumer confusion when presented with two complex products has identified ambiguous information as a key factor in deterring consumers from making a decision in a timely manner (Mitchell, Walsh and Yamin 2005). Considering that multiple participants in our study had concerns that the joint messaging of PrEP and condoms could confuse viewers, PrEP visual advertisements may be more effective if the focus of such advertisements was exclusively on PrEP or if the independent benefits of PrEP were specified in advertisements that included both PrEP and condoms.

Limitations

The results of this study should be interpreted within the context of its limitations. Although we believe saturation was achieved with respect to main themes, the sample size and the number of focus groups were relatively small. In addition, as a focus group study, the sample is not intended to be representative of US Black sexual minority men broadly, and findings are not intended to be broadly generalisable. Focus groups were conducted in an area with relatively high rates of HIV, and the majority of participants were aware of PrEP prior to participating in this study; in fact, nearly half had direct experience using PrEP. Perspectives on the advertisements may vary among Black sexual minority men from other geographic regions or with lower HIV prevalence and PrEP familiarity. Lastly, because we did not stratify groups by PrEP status, the opinions shared by PrEP users and non-users could have been influenced by the presence of one another to the extent that participants knew one another’s PrEP status. However, we saw value in integrating the focus groups, believing that inviting multiple perspectives within the group could enrich the conversation.

Conclusion

In addition to visual considerations of advertisement campaigns, it is important to concomitantly consider and tailor the textual elements of advertisements to maximise impact and acceptability for intended audiences. Specific adjustments to the textual aspects of PrEP visual advertisements – including (1) providing basic information and accessible methods to learn more information about PrEP; (2) using simple, unambiguous language; (3) presenting PrEP use in a destigmatising and normalising fashion; and (4) conveying the relevance of condoms when included in the advertisement – could enhance acceptability and facilitate further information-seeking among Black sexual minority men, ultimately enhancing PrEP access and uptake. Ultimately, this could help to reduce the spread of HIV in the USA and meet the goals of local and national initiatives to end the HIV epidemic (District of Columbia Department of Health 2020; US Department of Health and Human Services 2019).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the time and effort of study participants, as well as the We Play Sure, PrEP4Love, and Do It Right campaigns for supporting our use of their advertisements as visual stimuli in this study. The content of the paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the US National Institute of Mental Health, or the US National Institutes of Health.

Funding

This study was funded by the DC Center for AIDS Research (DC CFAR) Pilot Awards Program (P30-AI117970). SKC was supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health via Award Number K01-MH103080.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

One additional focus group was attempted but was ultimately excluded from the analytic sample because only one participant attended it.

References

- Amico KR, and Bekker LG. 2019. “Global PrEP Roll-Out: Recommendations for Programmatic Success.” Lancet HIV 6 (2): e137–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AVAC. 2022. “The Global PrEP Tracker.” Accessed on April 5, 2022. https://data.prepwatch.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Bull SS, Posner SF, Ortiz C, Beaty B, Benton K, Lin L, Pals SL, and Evans T. 2008. “POWER for Reproductive Health: Results from a Social Marketing Campaign Promoting Female and Male Condoms.” Journal of Adolescent Health 43: 71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill S, Taylor SW, Elsesser SA, Mena L, Hickson D, and Mayer KH. 2017. “Stigma, Medical Mistrust, and Perceived Racism May Affect PrEP Awareness and Uptake in Black Compared to White Gay and Bisexual Men in Jackson, Mississippi and Boston, Massachusetts.” AIDS Care 29 (11): 1351–1358. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1300633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese SK 2020. “Understanding, Contextualizing, and Addressing PrEP Stigma to Enhance PrEP Implementation.” Current HIV/AIDS Reports 17: 579–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese SK, Dovidio JF, Patel VV, Modrakovic D, Boone CA, Galvao RW, Rao S, et al. 2020. “The Stigmatizing Effect of ‘Targeting’ US Black Men Who Have Sex with Men in the Social Marketing of PrEP: A Mixed Methods Study.” Poster presented at the XXIII International AIDS Conference, Virtual, July 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2021a. “HIV Surveillance Report, 2019.” Accessed on April 5, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-updated-vol-32.pdf.

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2021b. “PrEP effectiveness.” Accessed on April 5, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/prep/prep-effectiveness.html.

- Creswell JW 2015. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, and Creswell JD. 2018. “Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.).” Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Dehlin JM, Stillwagon R, Pickett J, Keene L, and Schneider JA. 2019. “#PrEP4Love: An Evaluation of a Sex-Positive HIV Prevention Campaign.” JMIR Public Health and Surveillance 5 (2): e12822. doi: 10.2196/12822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- District of Columbia Department of Health. 2020. “DC ends HIV.” Accessed on April 5, 2022. https://www.dcendshiv.org/.

- District of Columbia Department of Health, HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis, STD, & TB Administration. 2021. “Annual Epidemiology & Surveillance Report: Data Through December 2020.” https://dchealth.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/doh/publication/attachments/2021%20Annual%20Surveillance%20Report_final.pdf.

- Elopre L, Ott C, Chapman Lambert C, Amico KR, Sullivan PS, Marrazzo J, Mugavero MJ, and Turan JM. 2021. “Missed Prevention Opportunities: Why Young, Black MSM with Recent HIV Diagnosis did not Access HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Services.” AIDS & Behavior 25: 1464–1473. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02985-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley JD, Firkey M, Sheinfil A, Ramos J, Woolf-King SE, and Vanable PA. 2021. “Framed Messages to Increase Condom Use Frequency Among Individuals Taking Daily Antiretroviral Medication for Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 50: 1755–1769. doi: 10.1007/s10508-021-02045-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, and Redwood S. 2013. “Using the Framework Method for the Analysis of Qualitative Data in Multi-Disciplinary Health Research.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 13: 117–124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedel WC, Coats CS, Sowemimo-Coker G, Moitra E, Murphy MJ, van den Berg JJ, Chan PA, and Nunn AS. 2021. “Gay and Bisexual Men’s Recommendations for Effective Digital Social Marketing Campaigns to Enhance HIV Prevention and Care Community.” AIDS & Behavior 25: 1619–1625. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-03078-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub SA, and Meyers JE. 2019. “Next-Wave HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Implementation for Gay and Bisexual Men.” AIDS Patient Care and STDs 33 (6): 253–261. doi: 10.1089/apc.2018.0290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub SA, Meyers K, and Enemchukwu C. 2020. “Perspectives and Recommendations From Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer/Questioning Youth of Color Regarding Engagement in Biomedical HIV Prevention.” Journal of Adolescent Health 66 (3): 281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmig B, and Thaler J. 2010. “On the effectiveness of social marketing – what do we really know?” Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 22 (4): 264–287. [Google Scholar]

- Kanny D, Jeffries WL IV, Chapin-Bardales J, Denning P, Cha S, Finlayson T, Wejnert C, and National HIV Behavioral Surveillance Study Group. 2019. “Racial/Ethnic Disparities in HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex with Men—23 Urban Areas, 2017.” MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 68 (37): 801–806. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6837a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene LC, Dehlin JM, Pickett J, Berringer KR, Little I, Tsang A, Bouris AM, and Schneider JA. 2021. “#PrEP4Love: success and stigma following release of the first sex-positive PrEP public health campaign.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 23 (3): 397–413. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2020.1715482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga MJ, Closson EF, Battle S, Herbst JH, Denson D, Pitts N, Holman J, Landers S, and Mansergh G. 2016. “Reactions and Receptivity to Framing HIV Prevention Message Concepts About Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for Black and Latino Men Who Have Sex with Men in Three Urban US Cities.” AIDS Patient Care and STDs 30 (10): 484–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell V-W, Walsh G, and Yamin M. 2005. “Towards a conceptual model of consumer confusion.” Advances in Consumer Research 32 (1): 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Ryan DT, Sanchez T, Sineath C, Macapagal K, and Sullivan PS. 2014. “Effects of Messaging about Multiple Biomedical and Behavioral HIV Prevention Methods on Intentions to Use Among US MSM: Results of an Experimental Messaging Study.” AIDS & Behavior 18: 1651–1660. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0811-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakelsky S, Moore L, and Garland WH. 2022. “Using Evaluation to Enhance a Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Social Marketing Campaign in Real Time in Los Angeles County, California.” Evaluation and Program Planning 90: 101988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslund JA, Jung Kim S, Aschbrenner KA, McCulloch LJ, Brunette MF, Dallery J, Bartels SJ, and Marsch LA. 2017. “Systematic Review of Social Media Interventions for Smoking Cessation.” Addictive Behaviors 73: 81–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, and Hoagwood K. 2015. “Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research.” Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 42: 533–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips G II, Raman AB, Felt D, McCuskey DJ, Hayford CS, Pickett J, Lindeman PT, and Mustanski B. 2020. “PrEP4Love: The Role of Messaging and Prevention Advocacy in PrEP Attitudes, Perceptions, and Uptake Among YMSM and Transgender Women.” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 83 (5): 450–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers B, Whiteley L, Haubrick KK, Mena LA, and Brown LK. 2019. “Intervention Messaging About Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Use Among Young, Black Sexual Minority Men.” AIDS Patient Care and STDs 33 (11): 473–481. doi: 10.1089/apc.2019.0139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ S, Zhang C, and Liu Y. 2021. “Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Care Continuum, Barriers, and Facilitators Among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men in the United States: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” AIDS & Behavior 25: 2278–2288. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-03156-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, Burroughs H, and Jinks C. 2018. “Saturation in Qualitative Research: Exploring its Conceptualization and Operationalization.” Quality & Quantity 52 (4): 1893–1907. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomann M, Grosso A, Zapata R, and Chiasson MA. 2018. “‘WTF is PrEP?’: Attitudes Towards Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender Women in New York City.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 20 (7): 772–786. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2017.1380230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underhill K, Guthrie K, Operario D, Calabrese SK, Kahler C, and Mayer K. 2018. “Message Framing Strategies for PrEP Education with Men Who Have Sex with Men in North America: Results of Three Randomized Trials.” Poster presented at the XXII International AIDS Conference, Amsterdam, July 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. 2019. “Ending the HIV Epidemic in the US.” Accessed on April 5, 2022. https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview. [Google Scholar]

- Wymer W. 2011. “Developing More Effective Social Marketing Strategies.” Journal of Social Marketing 1 (1): 17–31. doi: 10.1108/20426761111104400 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young I, and McDaid L. 2014. “How Acceptable are Antiretrovirals for the Prevention of Sexually Transmitted HIV? A Review of Research on the Acceptability of Oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis and Treatment as Prevention.” AIDS & Behavior 18 (2): 195–216. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0560-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]