Abstract

Background and Hypothesis

Two machine learning derived neuroanatomical signatures were recently described. Signature 1 is associated with widespread grey matter volume reductions and signature 2 with larger basal ganglia and internal capsule volumes. We hypothesized that they represent the neurodevelopmental and treatment-responsive components of schizophrenia respectively.

Study Design

We assessed the expression strength trajectories of these signatures and evaluated their relationships with indicators of neurodevelopmental compromise and with antipsychotic treatment effects in 83 previously minimally treated individuals with a first episode of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder who received standardized treatment and underwent comprehensive clinical, cognitive and neuroimaging assessments over 24 months. Ninety-six matched healthy case–controls were included.

Study Results

Linear mixed effect repeated measures models indicated that the patients had stronger expression of signature 1 than controls that remained stable over time and was not related to treatment. Stronger signature 1 expression showed trend associations with lower educational attainment, poorer sensory integration, and worse cognitive performance for working memory, verbal learning and reasoning and problem solving. The most striking finding was that signature 2 expression was similar for patients and controls at baseline but increased significantly with treatment in the patients. Greater increase in signature 2 expression was associated with larger reductions in PANSS total score and increases in BMI and not associated with neurodevelopmental indices.

Conclusions

These findings provide supporting evidence for two distinct neuroanatomical signatures representing the neurodevelopmental and treatment-responsive components of schizophrenia.

Keywords: structural MRI, semi-supervised machine learning, first-episode, long-acting injectable antipsychotic

Introduction

The neurodevelopmental and dopamine (DA) hypotheses are two major theories of schizophrenia that propose to explain the origins and underlying neurobiology of the disorder respectively.1 These hypotheses are broadly consistent with the proposal over 40 years ago by Crow2 of two distinct syndromes for schizophrenia, each with a specific pathological process. Crow proposed that “acute schizophrenia” is characterized by positive symptoms and is responsive to antipsychotic medication, while the “defect state” is characterized by negative symptoms, intellectual impairment, a poor long-term outcome and structural brain changes. However, while brain morphological differences have been consistently reported in schizophrenia,3 attempts to link these changes to both neurodevelopmental compromise4 and psychotic symptoms associated with DA dysregulation5 have met with limited success. This is not surprising given the heterogeneous nature of the illness with large variation in many aspects including brain structural changes.6 Additionally, differences in study populations and methodology including scanning protocols and selection of brain regions, likely contribute to the lack of consistent findings. A better understanding of these associations may further elucidate the underlying neurobiology of the illness and provide clinicians with tools for predicting outcome and individualizing treatment.

In a recent development using novel machine learning methods on regional brain volumetric measures to eliminate confounding variations, two markedly distinct and reproducible neuroanatomical signatures of schizophrenia were identified.7,8 Signature 1 is characterized by widespread lower grey matter volumes, particularly in the thalamus, nucleus accumbens, medial temporal, medial prefrontal/frontal and insular cortices, while signature 2 had larger basal ganglia and internal capsule but normal cortical anatomy. It was proposed that signature 1 is related to the neurodevelopmental component of the illness and signature 2 is related to functional abnormalities, perhaps in DA systems, leading secondarily to basal ganglia enlargement. These studies were cross-sectional and conducted in patients in different stages of illness and with varying medication exposure.

In this study, we applied these neuroanatomical signatures to a unique patient cohort to investigate their relationships with both indicators of neurodevelopmental deviance and with clinical and treatment effects. Our aims were 2-fold: to investigate the relationships of the two signatures with indicators of neurodevelopmental compromise and to assess their associations with treatment effects. For this study we examined the signatures as continuous variables rather than categorizing participants into subtypes as firstly, the signatures are not mutually exclusive but rather co-exist in individuals with different expression strengths and secondly, we were interested in assessing dynamic changes in the signature strengths over time. We measured the signature expression strengths in patients with a first episode of schizophrenia with no or minimal prior antipsychotic exposure, assessed their temporal stability over the first two years of treatment and investigated their relationships to selected factors associated with neurodevelopmental compromise (ie, factors implicated in disrupting normal neurodevelopment) and to antipsychotic treatment. Patients received treatment following a specified protocol with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic and underwent comprehensive clinical, cognitive, and neuroimaging assessments at fixed timepoints. This allowed us to investigate pre-treatment effects, to quantify the antipsychotic dose with precision and to assess longitudinal changes in signature expression in relation to treatment. In a recent study using similar methodology in an overlapping sample we found increased basal ganglia volumes that were associated with greater symptom reductions, weight gain, and more extrapyramidal symptoms. Additionally, although not differing significantly from controls, white matter volume increases were associated with greater clinical improvements, weight gain, and extrapyramidal symptoms, and slight cortical thickness reductions were unrelated to treatment.9 Based on these findings we hypothesized that signature 1 expression would be related to factors associated with neurodevelopmental compromise, would be stable over two years and would be uninfluenced by antipsychotic treatment. We further hypothesized that signature 2 expression would be unrelated to neurodevelopmental compromise but would be influenced by antipsychotic treatment in terms of dose, efficacy, and emergent side effects.

Methods

Study Sample

This single-site, case–control, prospective study was conducted between 2007 and 2017 and assessed clinical, cognitive, and brain-imaging changes over the first 2 years of treatment in patients with a first episode of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Previously published results from this cohort are provided in Supplementary Appendix 1. Of note is a recent publication reporting structural brain changes in relation to treatment effects in an overlapping sample to the present one.9 Patients were recruited from psychiatric community clinics and first admissions to hospitals within Cape Town and surrounding districts. Participants provided written, informed consent, and we obtained ethics approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of Stellenbosch University. Eligibility criteria were men and women, in- or out-patients, aged 16–45 years, meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnostic criteria for schizophreniform disorder, schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Exclusion criteria were lifetime exposure to > 4 weeks of antipsychotic medication, previous treatment with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic, serious or unstable medical condition or intellectual disability. The case–controls comprised healthy volunteers from the same community, matched by age, gender, and ethnicity. The patients and controls were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID).10 Controls were excluded if they had a DSM-IV axis I or II disorder or a first-degree family member with a psychotic disorder.

Predictors of Neurodevelopmental Compromise

Based on previous reports of associations with disrupted neurodevelopment in schizophrenia, we selected the following variables as putative indicators of neurodevelopmental compromise: A history of schizophrenia in a first-degree relative,11 obstetric complications,12 childhood trauma13 according to the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ),14 premorbid functioning15 according to the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS),16 scholastic achievement (highest school grade successfully completed), neurological soft signs17 as assessed by the Neurological Evaluation Scale (NES)18 and cognitive function19 as assessed by the MATRICS (Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia) Cognitive Consensus Battery (MCCB).20

Treatment Related Effects

We considered three aspects of treatment, namely antipsychotic dose, efficacy, and side effects. We calculated the precise antipsychotic dose in flupenthixol mg equivalents at each timepoint using consensus-derived guidelines for dose-equivalencies.21 For efficacy we assessed symptom severity with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS);22 for side effects we assessed body mass index (BMI) calculated as kg/m2 and for motor side effects we used the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS).23 Metabolic assessments comprised fasting blood glucose, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides and total cholesterol. The clinical, cognitive, laboratory, and MRI measures were assessed at baseline, month 12, and month 24. Urine toxicology tests for cannabis were conducted at months 0, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 and the number of positive tests was used as a proxy for frequency of use.

Treatment

Patients received treatment according to a standard protocol with the lowest possible antipsychotic dose. Oral flupenthixol 1–3 mg/day was prescribed for 1 week and thereafter flupenthixol decanoate intramuscular injections were administered 2-weekly for the study duration. Starting intramuscular dose was 10 mg 2-weekly, with 6-weekly 10 mg increments as required to a maximum of 30 mg 2-weekly. Other antipsychotics, mood stabilizers and psychostimulants were forbidden. Permitted medications included lorazepam, anticholinergics, propranolol, antidepressants and medications for general medical conditions. Five patients were initially treated for 12 weeks with long-acting risperidone injection at a starting dose of 25 mg intramuscular 2-weekly before switching to flupenthixol decanoate. Flupenthixol is pharmacologically similar to several new generation antipsychotics, binding primarily at the D1, D2, D3 receptors, 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C and alpha1-adrenergic receptors and its decanoate formulation has been extensively used in community settings.24,25

Image Acquisition and Pre-processing

Participants were scanned using a T1 ME-MPRAGE weighted structural sequence (TR = 2530 ms; TE1 = 1.53 ms TE2 = 3.21 ms, TE3 = 4.89 ms, TE4 = 6.57 ms, flip-angle: 7°C, FoV: 256 mm, 128 slices, 1 mm isotropic voxel size).26 Scans were segmented using a multi-atlas region segmentation utilizing an ensemble of registration algorithms and parameters, as described in detail elsewhere (MUSE).27 In brief, each individual’s T1 was segmented into 145 anatomical regions of interest from the grey matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid volumes (Supplementary table 1). Volumetric maps were generated voxel-wise28 for grey matter and white matter by a deformable registration of the skull stripped T1s in MNI space.29

Identifying Schizophrenia Imaging Signatures and Defining Subgroups

We used the heterogeneity through discriminative analysis (HYDRA) tool to identify the presence and expression strength of the schizophrenia imaging signatures. HYDRA is a semi-supervised machine learning algorithm that uses pre-specified patient and control labels in a data-driven approach to perform classification and clustering within the patient group. HYDRA allows for the separation of distinct patient groups rather than forcing patient data into a single common discriminative pattern. The HYDRA parameters were derived from the independent PHENOM consortium dataset (Psychosis Heterogeneity Evaluated via Dimensional Neuroimaging)7 and applied to the current dataset to estimate neuroanatomical signature expression strength (E1 and E2). Since controls are assigned a “−1” and schizophrenia patients a “+1” during HYDRA training, a positive E represents the presence of a signature, and a negative E represents its relative absence as described in previous work.8 Subgroups were determined accordingly, ie, subgroup 1 “S1” (E1 > 0, E2 < 0), subgroup 2 “S2” (E1 < 0, E2 > 0), both groups “S1+S2” (E1 > 0, E2 > 0) or neither group “S0” (E1 < 0, E2 < 0).

Statistical Analyses

The analysis set comprised a modified intent-to-treat population, which was participants with clinical data at baseline and at least one suitable MRI scan. Statistical analyses were performed with Statistica version 13.0 (Dell, 2015).

Primary Analyses

We used linear mixed effect repeated measures for fitting models (MMRM) to compare the visit-wise signature expression strength in patients versus controls. Signature 1 and 2 expression values were entered as the dependent variables in separate models, as repeated measures. We specified intercepts for participants as a random effect. Age and gender were covariates and time was a grouping variable. The group*time interaction was a fixed effect. We then conducted further MMRM analyses in the patients only to assess relationships of the signatures with predictors of neurodevelopmental compromise and treatment effects. Signature expression strength values were the dependent variables and modeled as repeated measures, time was a grouping variable and intercepts for participants were entered as a random effect. We first considered covariates comprising age, gender, ethnicity, duration of untreated psychosis, diagnosis, the number of positive cannabis urine tests, previous antipsychotic exposure (yes/no) and number of days of previous treatment. None had significant effects and were therefore not included in the subsequent models. We then assessed whether our selected predictors of neurodevelopmental compromise had significant effects on signature expression strength. Family history of schizophrenia, history of obstetric complications, CTQ Total score, highest educational achievement and PAS General score were time-invariant predictors, while NES Total score and MCCB composite score were time-dependent predictors. In the final model we investigated relations between treatment effects and signature expression strength. Antipsychotic dose, PANSS Total score, ESRS Total score, and BMI were time-dependent predictors. Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) test was used post hoc to compare within-group differences for the MMRM analyses, and we used Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR)30 to correct for multiplicity with a threshold of < 0.05 for the fixed effect tests. The adjusted significance level was 0.0059. The direction of the effects was established by partial correlational analyses.

Secondary Analyses

In a set of exploratory analyses, we investigated relationships between signature expression and neurodevelopmental compromise and treatment effects in greater detail. MMRM analyses were conducted in the patients with signature expression strength as the dependent variable and modeled as repeated measures, and intercepts for participants as a random effect. For predictors of neurodevelopmental compromise, we assessed CTQ subscale scores for emotional, physical and sexual abuse and emotional and physical neglect; premorbid adjustment by developmental stage (PAS scores for childhood, early adolescence, late adolescence); NES subscales of sensory integration, motor coordination and motor sequencing; and MCCB cognitive domains of speed of processing, attention/vigilance, working memory, verbal learning, visual learning, reasoning and problem solving and social cognition. For treatment effects, we assessed symptom changes in PANSS positive, negative and disorganized domains as determined by factor analysis,31 and fasting blood glucose, HDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, and total cholesterol. The secondary analyses were designated as exploratory, and corrections for multiplicity were not applied. These findings should therefore be regarded preliminary and suggestive of hypotheses for further studies.

Sensitivity Analysis

To test whether our results were not an artifact of the modified intent-to-treat population we repeated the primary analyses on the completer population only, ie, those participants who completed the 2 years of follow up and had a month 24 scan.

Results

Of 126 patients entered, 83 had baseline clinical data and at least one suitable scan. Forty-eight (58%) were antipsychotic naïve at baseline and 35 (42%) had received antipsychotics for a mean ± SD 9.7 ± 6.5 days before study entry. Forty-four patients completed the study. They did not differ significantly from the rest of the sample in terms of age (25.5 ± 7.4 vs 23.8 ± 6.0 years, P = .2503), gender (77% vs 71% male, P = .4915), highest school grade attained (9.8 ± 2.2 vs 9.9 ± 2.1, P = .7411), baseline PANSS total score (93.3 ± 14.2 vs 92.7 ± 15.7, P = .8626) and baseline expression strength for signature 1 (0.0015 ± 1.1330 vs −1.2396 ± 1303, P = .4095) and signature 2 (−0.7042 ± 1.1074 vs −0.8937 ± 1.1560, P = .4479). The control-group comprised 96 healthy volunteers. For patients and controls respectively, the mean age was 24.7 ± 6.8 and 26.0 ± 7.4 years (P = .1969), the percentage males was 74% and 62% (P = .0851) and the highest school grade achieved was 9.8 ± 2.1 and 10.5 ± 1.5 (P = .0237). Self-reported ethnic distribution was mixed ancestry 81% and 78%, black 13% and 15% and white 6% and 7% (P = .8549), being representative of the local community. For patients and controls respectively, the numbers of scans at each timepoint, were 83 and 96 at baseline, 39 and 52 at month 12 and 39 and 27 at month 24. Demographic, clinical, cognitive, and laboratory test details of the patients are provided in table 1. Neuroanatomical subtype assignment derived from the HYDRA results for the patients and controls at each timepoint is provided in Supplementary table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic, Clinical, Cognitive and Laboratory Test Details of the Patients

| Mean | SD |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 24.66 | 6.8 | ||

| Highest school grade passed | 9.85 | 2.1 | ||

| DUP (weeks) | 37.12 | 47.8 | ||

| Modal antipsychotic dose (flupenthixol mg equivalents) | 12.06 | 3.8 | ||

| % Adherence | 98.46 | 3.7 | ||

| Weeks in study | 68.82 | 39.5 | ||

| Childhood Trauma Questionnaire | ||||

| Total score | 48.13 | 16.5 | ||

| Emotional abuse subscale | 10.08 | 5.1 | ||

| Physical abuse subscale | 9.82 | 5.3 | ||

| Sexual abuse subscale | 7.25 | 4.1 | ||

| Emotional neglect subscale | 12.26 | 5.4 | ||

| Physical neglect subscale | 9.71 | 3.5 | ||

| Premorbid Adjustment Scale | ||||

| Childhood | 0.24 | 0.2 | ||

| Early adolescence | 0.29 | 0.2 | ||

| Late adolescence | 0.37 | 0.2 | ||

| Adulthood | 0.38 | 0.2 | ||

| General score | 0.48 | 0.2 | ||

| Overall score | 0.35 | 0.1 | ||

| Baseline | M24 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Baseline and M24 clinical, cognitive and laboratory assessments: | ||||

| PANSS Total score | 93.02 | 14.9 | 42.28 | 10.6 |

| PANSS Positive domain | 17.52 | 3.4 | 5.35 | 2.8 |

| PANSS Negative domain | 19.20 | 5.4 | 9.35 | 4.1 |

| PANSS Disorganized domain | 11.98 | 3.0 | 5.37 | 2.0 |

| ESRS Total score | 1.13 | 3.0 | 2.06 | 5.2 |

| MCCB Composite score | 19.87 | 12.3 | 27.78 | 15.5 |

| Speed of processing | 22.14 | 11.9 | 28.24 | 13.0 |

| Attention and vigilance | 24.02 | 11.5 | 32.24 | 10.7 |

| Working memory | 23.88 | 14.2 | 31.65 | 11.9 |

| Verbal learning | 31.05 | 9.5 | 37.34 | 11.4 |

| Visual learning | 28.43 | 14.7 | 35.47 | 15.1 |

| Reasoning and problem solving | 30.17 | 9.0 | 38.77 | 12.5 |

| Social cognition | 40.80 | 15.8 | 40.80 | 21.6 |

| BMI | 21.83 | 4.1 | 25.03 | 5.3 |

| Glucose | 4.72 | 0.7 | 5.10 | 1.9 |

| HDL-cholesterol | 1.19 | 0.6 | 1.00 | 0.3 |

| LDL-cholesterol | 2.59 | 0.8 | 2.76 | 0.9 |

| Triglycerides | 0.90 | 0.5 | 1.12 | 0.9 |

| Cholesterol | 4.14 | 0.9 | 4.31 | 1.0 |

Note: DUP, duration of untreated psychosis; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; ESRS, Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale; MCCB, MATRICS Cognitive Consensus Battery; BMI, Body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Signature Expression Strength Over the 2-Year Period for Patients and Controls

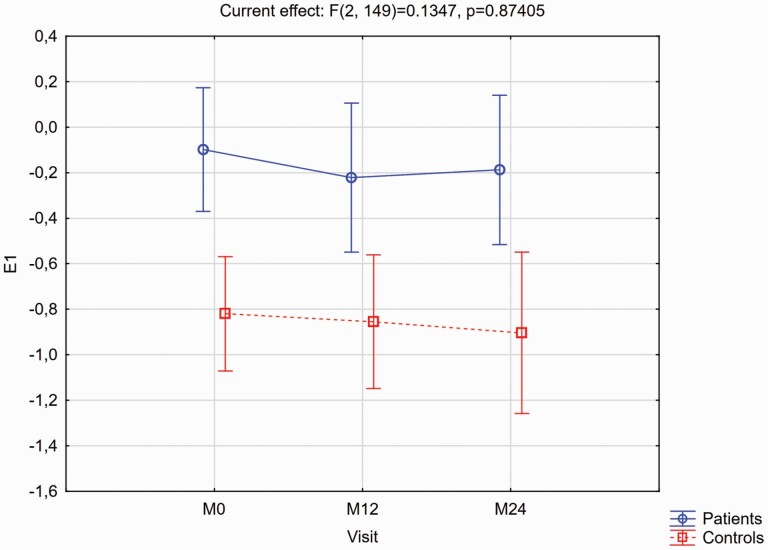

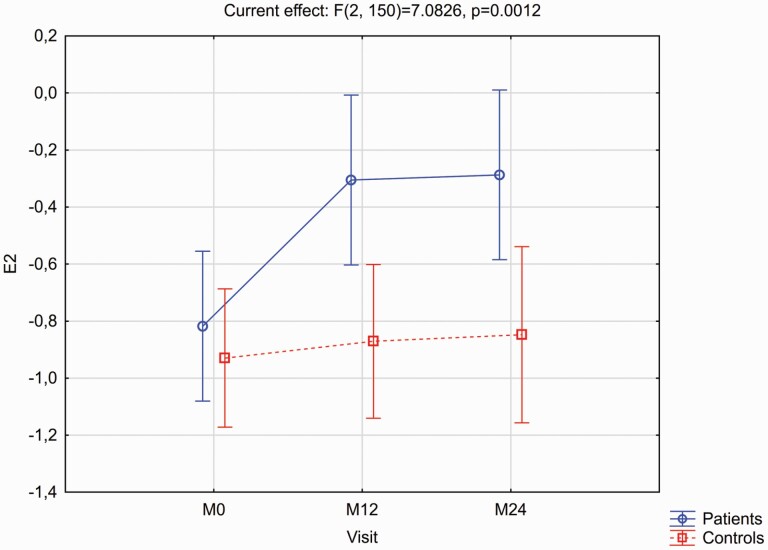

Figures 1 and 2 provide details of the expression strength of signatures 1 and 2 respectively over the two years in patients and controls, with the accompanying post hoc LSD test results as footnotes. For signature 1 the group*time interaction effect was not significant (F = 0.1347, P = .8741), and there were no significant within-group changes over time. However, at each timepoint patients had significantly greater signature 1 expression than controls. For signature 2 there was a significant group*time interaction (F = 6.9563, P = .0013). Expression strengths were similar between groups at baseline (P = .4561), and while controls did not change significantly over time (P = .4926) there was a highly significant increase in signature 2 strength in patients (P < .0001), with significant differences between the groups at M12 (P = .0047) and M24 (P = .0086).

Fig. 1.

Expression of signature 1 (E1) for the patients v. controls, as visit-wise least square means and 95% confidence intervals from baseline to month 24, from the MMRM models. Mean (95% CI) signature 1 expression differences for patients vs controls at each timepoint, and for the within-group changes from baseline to M24 derived from the post hoc Fisher’s LSD test results were: Between group differences: M0 = 0.72 (0.35–1.09), P = .0002; M12 = 0.68 (0.11–1.26), P = .0049; M24 = 0.85 (0.21–1.50), P = .0094. Within-group differences from M0 to M24: Patients 0.12 (–0.26 to 0.50), P = .5302; Controls –0.01 (–0.44 to 0.43), P = .9819.

Fig. 2.

Expression of Signature 2 (E2) for the patients v. controls, as visit-wise least square means and 95% confidence intervals from baseline to month 24, from the MMRM models. Mean (95% CI) signature 2 expression differences for patients vs. controls at each timepoint, and for the within-group changes from baseline to M24 derived from the post hoc Fisher’s LSD test results were: Between group differences: M0 = 0.14 (–0.22 to 0.50), P = .4561; M12 = 0.59 (0.18–0.99), P = .0047; M24 = 0.58 (0.15–1.01), P = .0086. Within-group differences from M0 to M24: Patients –0.53 (–0.73 to 0.32), P ≤ .0001; Controls –0.08 (–0.32 to 0.15), P = .4926.

Neurodevelopmental Compromise and Signature Expression in Patients

Results of the fixed effect tests for our predictors of neurodevelopmental compromise on the two signatures, derived from the MMRM analyses, are provided in table 2. There were no significant effects for any of our selected predictors at the FDR corrected significance level in the primary analyses. Stronger signature 1 expression was associated at trend-level with lower educational attainment (P = .0608) and poorer NES total score (P = .0635). In the secondary analysis (table 3) stronger signature 1 expression was significantly associated (uncorrected) with poorer NES sensory integration subscale scores (P = .0256) and poorer performance in the cognitive domains of working memory (P = .0175), visual learning (P = .0430) and reasoning and problem solving (P = .0371). For signature 2 there were no significant or trend-level associations with any predictors of neurodevelopmental compromise in the primary analysis, and in the secondary analysis there was a trend-level association between greater signature expression and better premorbid adjustment in late adolescence (P = .053).

Table 2.

Fixed Effect Test Results for the Primary Analysis of Potential Covariates, Predictors of Neurodevelopmental Compromise and Treatment Related Effects on the Two Signatures Expression Strengths, Derived from the MMRM Models

| Signature 1 | Signature 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | P * | F | P * | |

| Potential covariates | ||||

| Age | 0.10 | 0.7532 | 1.22 | 0.2737 |

| Gender | 0.11 | 0.7422 | 0.01 | 0.9030 |

| Ethnicity | 0.15 | 0.7043 | 0.11 | 0.7381 |

| DUP weeks | 0.02 | 0.8756 | 0.22 | 0.6414 |

| Axis 1 diagnosis | 1.48 | 0.2283 | 0.43 | 0.5162 |

| Cannabis number of positive tests | 0.05 | 0.8176 | 2.30 | 0.1337 |

| Factors associated with neurodevelopmental compromise | ||||

| Family history of schizophrenia | 1.74 | 0.1912 | 0.26 | 0.6119 |

| Obstetric complications | 0.30 | 0.5870 | 0.39 | 0.5336 |

| CTQ Total score | 2.47 | 0.1217 | 0.11 | 0.7369 |

| Highest grade passed | 3.64 | 0.0608 | 1.08 | 0.3021 |

| PAS Total General score | 0.01 | 0.9199 | 2.30 | 0.1341 |

| NES Total score | 3.56 | 0.0635 | 0.05 | 0.8202 |

| MCCB Composite score | 0.88 | 0.3541 | 0.91 | 0.3459 |

| Treatment related effects | ||||

| Flupenthixol dose | 2.73 | 0.1029 | 0.00 | 0.9660 |

| PANSS Total score | 0.20 | 0.6564 | 20.32 | <0.0001 |

| ESRS Total score | 0.19 | 0.6611 | 3.81 | 0.0550 |

| BMI | 0.30 | 0.5840 | 8.55 | 0.0046 |

Note: DUP, duration of untreated psychosis; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; PAS, Premorbid Adjustment Scale; NES, Neurological Evaluation Scale; MCCB, MATRICS Cognitive Consensus Battery; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; ESRS, Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale; BMI, Body mass index.

*FDR adjusted significance level = 0.0059.

Table 3.

Fixed Effect Test Results for the Secondary Analysis of Potential Covariates, Predictors of Neurodevelopmental Compromise and Treatment Related Effects on the Two Signatures, Derived from the MMRM Models

| Subtype 1 | Subtype 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | P * | F | P * | |

| CTQ Subscale scores | ||||

| Emotional abuse | 1.79 | 0.1869 | 0.07 | 0.7864 |

| Physical abuse | 0.89 | 0.3497 | 0.12 | 0.7266 |

| Sexual abuse | 1.75 | 0.1918 | 1.36 | 0.2488 |

| Emotional neglect | 0.70 | 0.4053 | 0.02 | 0.8814 |

| Physical neglect | 0.13 | 0.7181 | 0.23 | 0.6353 |

| PAS Subscale scores | ||||

| Childhood | 0.43 | 0.5158 | 0.04 | 0.8364 |

| Early adolescence | 2.82 | 0.0973 | 0.99 | 0.3219 |

| Late adolescence | 0.12 | 0.7289 | 3.87 | 0.0530 |

| PANSS domain scores | ||||

| Positive | 0.57 | 0.4536 | 20.22 | <0.0001 |

| Negative | 0.17 | 0.6794 | 0.26 | 0.6147 |

| Disorganized | 1.41 | 0.2397 | 0.33 | 0.5660 |

| NES Subscale scores | ||||

| Sensory Integration | 5.19 | 0.0256 | 0.54 | 0.4643 |

| Motor Coordination | 1.81 | 0.1824 | 0.32 | 0.5757 |

| Motor sequencing | 0.71 | 0.4018 | 0.51 | 0.4770 |

| MCCB cognitive domains | ||||

| Speed of processing | 0.36 | 0.5497 | 0.41 | 0.5274 |

| Attention and vigilance | 0.62 | 0.4342 | 0.00 | 0.9988 |

| Working memory | 6.13 | 0.0175 | 0.02 | 0.9026 |

| Verbal learning | 0.00 | 0.9831 | 0.52 | 0.4739 |

| Visual learning | 4.36 | 0.0430 | 0.05 | 0.8161 |

| Reasoning and problem solving | 4.64 | 0.0371 | 0.46 | 0.5034 |

| Social cognition | 0.36 | 0.5553 | 0.47 | 0.4959 |

| Fasting blood glucose and lipids | ||||

| Glucose | 1.06 | 0.3061 | 2.21 | 0.1420 |

| HDL-cholesterol | 0.17 | 0.6846 | 0.38 | 0.5393 |

| LDL-cholesterol | 0.97 | 0.3280 | 0.04 | 0.8358 |

| Triglycerides | 0.08 | 0.7759 | 5.28 | 0.0245 |

| Cholesterol | 0.12 | 0.7322 | 0.86 | 0.3565 |

Note: CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; PAS, Premorbid Adjustment Scale; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; NES, Neurological Evaluation Scale; MCCB, MATRICS Cognitive Consensus Battery; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

*P values uncorrected for multiple comparisons.

Treatment Effects and Signature Expression in Patients

Increased signature 2 expression was significantly associated (corrected) with greater PANSS Total score reductions (P < .0001) and greater BMI increase (P = .0046), and at trend-level with ESRS Total score (P = .0550) (table 2). In the secondary analysis (table 3) increase in signature 2 expression was significantly associated (uncorrected) with greater symptom reduction in the PANSS positive domain (P < .0001), and increased triglycerides (P = .0245).

Sensitivity Analysis

The analyses in the completers-only sample broadly confirmed those of the primary analyses. For the MMRM comparing signature 1 expression in patients versus controls the group*time interaction was non-significant (F = 1.3, P = .2683) but expression was significantly stronger (uncorrected) in the patients at baseline (P = .0022) and month 24 (P = .011) and at trend-level at month 12 (P = .0598). For signature 2 there was a near-significant group*time interaction (F = 3.1, P = .0510) and expression was similar in patients and controls at baseline (P = .8222) but increased significantly from baseline to month 12 (P = .0005) and month 24 (P < .0001) in patients, but not in controls at month 12 (P = .2471) and month 24 (0.4414). For the fixed effect tests in the completers-only sample, increase in signature 2 expression was significantly associated (uncorrected) with greater PANSS total score reductions (P = .0017) and with greater BMI increase (P = .0208).

Discussion

In this study investigating the temporal stability and correlates of two recently described neuroanatomical signatures of schizophrenia in previously minimally treated individuals we found that the signatures displayed distinctly different trajectories over the 2-year treatment period and were differentially associated with indicators of neurodevelopmental compromise and treatment effects.

Signature 1 and Neurodevelopmental Compromise

Several of our findings suggest a relationship between signature 1 and the neurodevelopmental component of schizophrenia. Consistent with the trait nature of neurodevelopmental deficits,32 signature 1 expression remained stable over time. However, this is at odds with previous reports of cortical thinning over time33 and our own earlier study finding of modest global cortical thickness reductions in patients but not controls.9 A possible confound here is that there may be some overlap between the signatures. Signature 1 includes some periventricular tissue, including thalamus and caudate, although these regions do not overlap with those of signature 2. The signature 1 score would then appear stable when in fact reductions in cortical thickness are balanced by increases in these structures in the basal ganglia. Furthermore, signature 1 was not influenced by treatment effects at all—again consistent with the proposal that subtype 1 represents non-dopaminergic abnormalities of the illness that are less responsive to DA blocking antipsychotics.7 However, we found only tentative links with our neurodevelopmental markers, suggesting weak effects for these variables and indicating caution when interpreting these results. Nevertheless, the trend-level association with poorer educational attainment is consistent with the initial study7 and the association with poorer cognitive performance was also reported in the second study.8 Finally, the trend-effect for neurological soft signs also suggests an association with underlying neurodevelopmental compromise. Subtle neurodevelopmental deficits including lower educational achievement, poorer cognitive ability and sensorimotor impairments are common in schizophrenia, and are considered promising candidates for endophenotypic markers of the illness.34 Unexpectedly, we did not find an association between negative symptom severity and signature 1 expression, as postulated by Crow. However, our negative symptom measure was not tailored for a defect state, and Crow specified that his type II syndrome related to those narrowly defined negative symptoms associated with the deficit state.35

Signature 2 and Treatment Effects

Our most compelling findings relate to the associations between signature 2 and antipsychotic treatment. The strengthening of signature 2 expression in patients over the treatment period could reflect a general and global response to antipsychotics, consistent with increased striatal volumes observed in healthy rats treated with antipsychotics.36 Furthermore, that signature 2 expression was similar to the controls in the patients prior to receiving study treatment counts against this signature being directly related to the illness, at least in its pre-treatment neuroanatomic manifestations. But rather than a non-specific effect, the significant association between signature 2 expression strength and symptom reduction suggests a relationship to mechanisms underlying psychosis. The association was highly significant and specific to positive symptoms—the symptoms with the closest relation to DA dysfunction37 and for which antipsychotics work best.38 The relationship between signature 2 and treatment emergent weight gain provides an additional link with antipsychotic treatment, in this case an adverse effect. Similarly, the association with increased triglyceride levels in our secondary analysis suggests a relationship with deteriorating lipid profiles. Weight gain and accompanying dyslipidemia are common and serious side effects associated with most antipsychotics39 and importantly, have been linked to the clinical benefits of these agents,40 thereby raising the possibility of a shared underlying mechanistic pathway.41 It is possible that signature 2 defines this mechanistic pathway. Finally, the trend-level association with ESRS scores suggests that signature 2 may also be related to antipsychotic induced motor symptoms.

The most likely mechanism underlying these associations would be via DA pathways, given that antipsychotic efficacy as well as treatment emergent extrapyramidal symptoms and (at least in part) antipsychotic induced weight gain have all been attributed to the DA receptor antagonistic effects of these agents.42 However, notwithstanding our ability to assess the dose with precision, we did not find a relationship between antipsychotic dose and signature 2 expression, consistent with a recent report of a hyperbolic dose-response with flattening of the curve beyond a certain point.43

Relating structural MRI measures to underlying cellular pathology is challenging. MRI is not a direct measure of brain structure and may be confounded by epiphenomena and artifacts.44 Nevertheless, several mechanisms could explain the link between antipsychotic responsiveness and increases in signature 2 expression and basal ganglia volume. While antipsychotics are proposed to have neuroprotective effects ranging from preventive to restorative mediated via multiple mechanisms including neurogenesis,45 counting against this is that baseline measures were similar in patients and controls and the treatment-associated increases in patients went beyond those of the healthy controls. This rather suggests an adaptive or compensatory response, possibly involving structural remodeling, changes in water content,46 microglial proliferation,47 or augmented blood flow to the striatum.48

Nonetheless, a treatment effect cannot fully explain the occurrence of signature 2, particularly when the neuroanatomical subtypes are considered categorically. Although not part of our analyses and only presented as Supplementary material, when allocated to subtypes,7 22% of our patients were classified as subtype 2 (either alone or together with subtype 1) prior to treatment. Subtype 2 was also present in 22% of our healthy controls. Indeed, the presence of both subtypes in some controls aligns with previous findings in healthy adults and may represent a biological vulnerability to schizophrenia found in the general population, the majority of whom will never develop the illness.8 Also, these supplementary findings suggest that pre-treatment allocation to subtypes does not predict treatment outcomes or changes in cortical thickness, basal ganglia or white matter volumes (Supplementary table 3).

Study Strengths and Weaknesses

Study strengths are related to the unique nature of our sample that allowed us to investigate the neuroanatomical signatures prior to treatment and to assess their trajectories longitudinally compared to healthy volunteers. We were also able to comprehensively assess treatment related effects in terms of the precise antipsychotic dose received, efficacy, and adverse effects. A further strength is that our sample was completely independent of the discovery sample, thereby providing additional information on the signatures in individuals with schizophrenia. There are also study limitations. First, while the sample size is relatively large for a single-site study of this nature the study power is limited when compared to larger multisite samples. This limitation needs to be weighed against the advantages of a single-site study such as standardized treatment, uniformity of assessments and the use of a single MRI scanner. Second, as with most longitudinal studies in schizophrenia49 the attrition rate was considerable. While the MMRM models offer a powerful framework for analyzing longitudinal imaging data50 the missing values introduce a risk of bias. However, counting against this is that our sensitivity analysis with completers-only produced a similar pattern to our main findings. Third, while our use of a single antipsychotic avoided possible confounding treatment effects of multiple antipsychotics, it also limits generalization of our findings to other antipsychotics with different pharmacologic profiles. Fourth, associations between neurodevelopmental compromise and signature 1 expression were largely non-significant and must be interpreted with caution. Finally, longer term changes in subtype signature expression cannot be extrapolated from our findings and would need to be evaluated in studies conducted over a longer study period.

In conclusion, we provide evidence that two distinct neuroanatomical signatures represent treatment-responsive and non-responsive components of the illness that may be linked to dopaminergic and neurodevelopmental components of schizophrenia. Future studies should include larger samples, a longer study period and additional indicators of neurodevelopmental deviance.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Stefan du Plessis, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Tygerberg Campus, Cape Town, South Africa.

Ganesh B Chand, Center for Biomedical Image Computing and Analytics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; Department of Radiology and Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis.

Guray Erus, Center for Biomedical Image Computing and Analytics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Lebogang Phahladira, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Tygerberg Campus, Cape Town, South Africa.

Hilmar K Luckhoff, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Tygerberg Campus, Cape Town, South Africa.

Retha Smit, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Tygerberg Campus, Cape Town, South Africa.

Laila Asmal, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Tygerberg Campus, Cape Town, South Africa.

Daniel H Wolf, Center for Biomedical Image Computing and Analytics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Christos Davatzikos, Center for Biomedical Image Computing and Analytics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Robin Emsley, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Tygerberg Campus, Cape Town, South Africa.

Funding

This research was supported by the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) through the Department of Science and Technology of South Africa grant UID 65174 and the South African Medical Research Council grant MRC- RFA-IFSP-01-2013. Study medication was supplied by Lundbeck International.

Conflict of interest statement

In the past 3 years, R.E. has received honoraria from Janssen, Lundbeck and Otsuka for advisory board and speaker activities. The other authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Howes OD, Murray RM.. Schizophrenia: an integrated sociodevelopmental-cognitive model. Lancet. 2014;383(9929): 1677–1687. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62036-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Crow TJ. Molecular pathology of schizophrenia: more than one disease process? Br Med J. 1980;280(6207):66–68. doi: 10.1136/bmj.280.6207.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Erp TGM, Walton E, Hibar DP, et al. Cortical Brain Abnormalities in 4474 Individuals With Schizophrenia and 5098 Control Subjects via the Enhancing Neuro Imaging Genetics Through Meta Analysis (ENIGMA) Consortium. Biol Psychiatry 2018;84:644–654. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murray RM, Bora E, Modinos G, Vernon AS.. A developmental disorder with a risk of non-specific but avoidable decline. Schizophr Res. 2022;243:181–186. doi: 10.1016/J.SCHRES.2022.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mathalon DH, Ford JM.. Neurobiology of schizophrenia: search for the elusive correlation with symptoms. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:1–6. doi: 10.3389/FNHUM.2012.00136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Voineskos AN, Jacobs GR, Ameis SH.. Neuroimaging heterogeneity in psychosis: neurobiological underpinnings and opportunities for prognostic and therapeutic innovation. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;88(1):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chand GB, Dwyer DB, Erus G, et al. Two Distinct Neuroanatomical Subtypes of Schizophrenia Revealed Using Machine Learning. Brain 2020;143:1027–1038. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chand GB, Singhal P, Dwyer DB, et al. Schizophrenia imaging signatures and their associations with cognition, psychopathology, and genetics in the general population. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179(9):650–660. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.21070686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Emsley R, Du Plessis S, Phahladira L, et al. Antipsychotic treatment effects and structural MRI brain changes in schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2021;1:10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721003809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW.. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, 11/2002 revision). 2nd. For DSMIV. 2002:132.

- 11. Lobato MI, Belmonte-De-Abreu P, Knijnik D, Teruchkin B, Ghisolfi E, Henriques A.. Neurodevelopmental risk factors in schizophrenia. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2001;34(2):155–163. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2001000200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murray RM, Lewis SW.. Is schizophrenia a neurodevelopmental disorder? BMJ. 1987;295(6600):681–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kilian S, Burns JK, Seedat S, et al. Factors moderating the relationship between childhood trauma and premorbid adjustment in first-episode schizophrenia. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0170178. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0170178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abus Negl. 2003;27(2):169–190. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Preston NJ, Orr KG, Date R, Nolan L, Castle DJ.. Gender differences in premorbid adjustment of patients with first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2002;55(3):285–290. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00215-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cannon-Spoor HE, Potkin SG, Wyatt RJ.. Measurement of premorbid adjustment in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1982;8(3):470–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Emsley R, Chiliza B, Asmal L, et al. Neurological soft signs in first-episode schizophrenia: state- and trait-related relationships to psychopathology, cognition and antipsychotic medication effects. Schizophr Res. 2017;188:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Buchanan RW, Heinrichs DW.. The neurological evaluation scale (NES): a structured instrument for the assessment of neurological signs in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1989;27(3):335–350. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bora E. Neurodevelopmental origin of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2015;45(1):1–9. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nuechterlein KH, Green MF.. MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery Manual. Los Angeles, MATRICS Assess Man. Published online 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, Centorrino F, Baldessarini RJ.. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):686–693. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09060802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA.. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chouinard G, Margolese HC.. Manual for the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS). Schizophr Res. 2005;76(2-3):247–265. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bandelow B. Wirkung von Flupentixol auf Negativsymptomatik und depressive Syndrome bei schizophrenen Patienten. In: Glaser, T., Soyka M (ed), Flupentixol—Typisches Oder Atypisches Wirkspektrum? Darmstadt: Steinkopff; 1998:67–77. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-93700-2_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mahapatra J, Quraishi SN, David A, Sampson S, Adams CE.. Flupenthixol decanoate (depot) for schizophrenia or other similar psychotic disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(6):CD001470. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001470.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van der Kouwe AJW, Benner T, Salat DH, Fischl B.. Brain morphometry with multiecho MPRAGE. Neuroimage. 2008;40(2):559–569. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2007.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Doshi J, Erus G, Ou Y, et al. ; Alzheimer's Neuroimaging Initiative. MUSE: MUlti-atlas region Segmentation utilizing Ensembles of registration algorithms and parameters, and locally optimal atlas selection. Neuroimage. 2016;127:186–195. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2015.11.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Davatzikos C, Genc A, Xu D, Resnick SM.. Voxel-based morphometry using the RAVENS maps: methods and validation using simulated longitudinal atrophy. Neuroimage. 2001;14(6):1361–1369. doi: 10.1006/NIMG.2001.0937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ou Y, Sotiras A, Paragios N, Davatzikos C. DRAMMS.. Deformable registration via attribute matching and mutual-saliency weighting. Med Image Anal. 2011;15(4):622–639. doi: 10.1016/J.MEDIA.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Genovese CR, Lazar NA, Nichols T.. Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using the false discovery rate. Neuroimage. 2002;15(4):870–878. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Emsley R, Rabinowitz J, Torreman M, et al. ; RIS-INT-35 Early Psychosis Global Working Group. The factor structure for the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) in recent-onset psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2003;61(1):47–57. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00302-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rapoport JL, Giedd JN, Gogtay N.. Neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: update 2012. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(12):1228–1238. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Van Haren NEM, Schnack HG, Cahn W, et al. Changes in cortical thickness during the course of illness in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(9):871–880. doi: 10.1001/ARCHGENPSYCHIATRY.2011.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rapoport JL, Addington AM, Frangou S, Psych MRC.. The neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: update 2005. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(5):434–449. doi: 10.1038/SJ.MP.4001642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Crow TJ. The two-syndrome concept: origins and current status. Schizophr Bull. 1985;11(3):471–486. doi: 10.1093/schbul/11.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Andersson C, Hamer RM, Lawler CP, Mailman RB, Lieberman JA.. Striatal volume changes in the rat following long-term administration of typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(2):143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kesby JP, Eyles DW, McGrath JJ, Scott JG.. Dopamine, psychosis and schizophrenia: the widening gap between basic and clinical neuroscience. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41398-017-0071-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lally J, MacCabe JH.. Antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: a review. Br Med Bull. 2015;114(1):169–179. doi: 10.1093/BMB/LDV017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Barton BB, Segger F, Fischer K, Obermeier M, Musil R.. Update on weight-gain caused by antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2020;19(3):295–314. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2020.1713091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Raben AT, Marshe VS, Chintoh A, Gorbovskaya I, Müller DJ, Hahn MK.. The complex relationship between antipsychotic-induced weight gain and therapeutic benefits: a systematic review and implications for treatment. Front Neurosci. 2018;11. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Venkatasubramanian G, Rao NP, Arasappa R, Kalmady SV, Gangadhar BN.. A longitudinal study of relation between side-effects and clinical improvement in schizophrenia: is there a neuro-metabolic threshold for second generation antipsychotics? Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2013;11(1):24–27. doi: 10.9758/CPN.2013.11.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kaar SJ, Natesan S, Mccutcheon R, Howes OD.. Antipsychotics: mechanisms underlying clinical response and side-effects and novel treatment approaches based on pathophysiology. Neuropharmacology. 2019;172. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.107704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Leucht S, Bauer S, Siafis S, et al. Examination of dosing of antipsychotic drugs for relapse prevention in patients with stable schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(11):1238–1248. doi: 10.1001/JAMAPSYCHIATRY.2021.2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Weinberger DR, Radulescu E.. Structural magnetic resonance imaging all over again. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(1):11–12. doi: 10.1001/JAMAPSYCHIATRY.2020.1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chen AT, Nasrallah HA.. Neuroprotective effects of the second generation antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:1–7. doi: 10.1016/J.SCHRES.2019.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zatorre RJ, Fields RD, Johansen-Berg H.. Plasticity in gray and white: neuroimaging changes in brain structure during learning. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(4):528–536. doi: 10.1038/nn.3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cotel MC, Lenartowicz EM, Natesan S, et al. Microglial activation in the rat brain following chronic antipsychotic treatment at clinically relevant doses. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25(11):2098–2107. doi: 10.1016/J.EURONEURO.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Corson PW, O’Leary DS, Miller DD, Andreasen NC.. The effects of neuroleptic medications on basal ganglia blood flow in schizophreniform disorders: a comparison between the neuroleptic-naïve and medicated states. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(9):855–862. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01421-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Homman LE, Smart SE, O’Neill F, MacCabe JH.. Attrition in longitudinal studies among patients with schizophrenia and other psychoses; findings from the STRATA collaboration. Psychiatry Res. 2021;305:114211. doi: 10.1016/J.PSYCHRES.2021.114211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bernal-Rusiel JL, Greve DN, Reuter M, Fischl B, Sabuncu MR; Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Statistical analysis of longitudinal neuroimage data with linear mixed effects models. Neuroimage. 2013;66:249–260. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2012.10.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.