Abstract

Objective

A healthy diet is a modifiable risk factor that may impact cognition. A unique type of diet may include intermittent fasting (IF), an eating pattern in which individuals go extended periods with little or no meal intake, intervening with periods of normal food intake. IF has multiple health benefits including maintenance of blood glucose levels, reduction of insulin levels, depletion or reduction of glycogen stores, mobilization of fatty acids, and generation of ketones. IF has shown neuroprotective effects as it may lead to increased neurogenesis in the hippocampus, which may contribute to cognitive resilience. Diets including IF were examined as lifestyle modifications in the prevention and management of cognitive decline.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) which assessed the effect of dieting on cognitive functions in adults.

Results

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH), low-glycemic diets, and caloric restriction have shown improvement in cognitive function; however, there was a negative impact on problem-solving in those with comorbid cardiovascular disease. There is also contradictory evidence that caloric restriction and diet alone may not be sufficient for the improvement of cognitive functions and that exercise may have better efficacy on cognition.

Conclusion

IF is considered a safe intervention, and no adverse effects were found in the reviewed studies; however, evidence is limited as there were only 9 low-quality RCTs that assessed the impact of IF on cognition. DASH, low-glycemic diets, and exercise may have effective roles in the management and prevention of cognitive decline, although further research is needed.

Keywords: Intermittent fasting, Dieting, Caloric restriction, Cognitive decline, Dementia, Time-restricted eating

Highlights of the Study

-

•

Dietary approaches such as low-glycemic diets and caloric restriction have shown improvements in cognitive function.

-

•

Dietary approaches may have a negative impact on problem-solving in those with comorbid cardiovascular disease.

-

•

There is contradictory evidence that caloric restriction and diet alone is sufficient for the improvement of the cognitive functions.

Introduction

A healthy diet is a modifiable risk factor that may impact cognition [1]. Two main dietary patterns have shown evidence of cognitive improvement, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet and the Mediterranean diet. The DASH diet involves eating foods that are rich in fruit, vegetables, fish, whole-cereal products, and low-fat dairy products while reducing foods high in saturated fat and sugar [2]. This diet has not only shown success in lowering cholesterol, saturated fats, and blood pressure but has shown improvements in cognitive function among older adults [3]. Similarly, the Mediterranean diet involves the consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, olive oil, fish, nuts, and legumes and low consumption of processed foods, dairy, and red meat [1]. The Mediterranean diet has shown slowing of neurodegenerative processes including oxidative stress and neuroinflammation which have been associated with improvement in cognitive function, lower rates of cognitive decline, and a reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease [4]. When both DASH and Mediterranean diets were compared, there were similar rates of slowing cognitive decline in adults [4]. The Mediterranean diet has shown a stronger association with positive cognitive outcomes compared to other specific food groups due to the cumulative beneficial effects of individual ingredients in the diet [5].

In addition to DASH and Mediterranean diets, intermittent fasting (IF) is defined as an eating pattern in which individuals go extended periods with little or no meal intake, intervening with periods of normal food intake [5]. Many regimens could be included under the term IF like complete fasting every other day, 70% energy restriction every other day, consuming only 500–700 calories (cL) on 2 consecutive days/week, and restricting food intake to 6–8 h daily. IF has shown multiple benefits in general health like maintenance of blood glucose levels in the low normal range, reduction of insulin levels, depletion or reduction of glycogen stores, mobilization of fatty acids, and generation of ketones [6]. IF is also considered an effective intervention against obesity and its complications such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and chronic diseases such as diabetes and cancer [7]. The effect of IF is not limited to metabolic dysfunction; it also reduces resting heart rate, blood pressure, and inflammation [6].

IF has also been shown to have a possible neuroprotective benefit as it may lead to an increase in neurogenesis levels in the hippocampus [8] and thus play an effective role against acute brain injuries such as stroke [8, 9] and neurodegenerative diseases in rodent models [10]. The proposed mechanism behind IF is mitochondriogenesis, which involves the synthesis of new mitochondria as well as the prevention of mitochondria decay that has shown improvement in overall health, including cognition [11]. Evidence from animal models suggests that mitochondrial metabolism, autophagy, and stress responses are the mechanism underlying IF, which is likely similar in humans [12]. However, the molecular mechanism involved in IF-induced neurogenesis is not well understood. There is little evidence that IF regimens are harmful for patients who can tolerate fasting [7]. Time-restricted eating is synonymous to IF, a popular dietary strategy that emphasizes the timing of meals in alignment with circadian rhythms during a restricted window each day, which has shown positive results in the cognitive status of older people compared to those without a restricted eating window [13]. Time-restricted eating has a defined window for meal intake with an interval of 8–12 h during the daytime with no caloric limitation.

Pharmacotherapy has shown limited benefits in the management of dementia [14], and as a result, lifestyle modification such as diet and physical activity and the management of chronic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension have been suggested to have a role in the management and prevention of dementia [14]. IF is one of the suggested dietary approaches in the management of cognitive decline due to its role in improving neurogenesis [8]. This review summarizes the current evidence-based literature on the effect of diet and IF in the prevention and management of cognitive decline.

Methods

MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and PubMed databases were searched with the keywords “Intermittent fasting” OR “Caloric restriction” OR “Time-restricted eating” AND “Diet” AND “Alzheimer’s disease” OR “Dementia” OR “Cognitive decline” OR “Memory,” Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in the English language, which assessed the effect of IF on cognitive functions in humans >18 years old were included. “Time-restricted eating” was initially used as a keyword; however, it did not add any additional articles to the search. As the registration is not a mandatory act, although it is a good practice, this study was not registered at PROSPERO as the topic is unique, and the impression was that it could be a very low risk to have it duplicated based on the current existent limited literature on this topic. Statistical significance for study results was defined as a test hypothesis being rejected with a cut-off of p < 0.05.

Data were extracted independently by two reviewers (O.F. and H.S.) from each report including the study design, number of fasting hours, amount of caloric restriction (CR), the compared variables, the statistical analysis, and authors’ conclusions about the impact of IF in prevention and management of dementia. The PRISMA checklist for this review can be found in online supplementary Table 1 (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000530269).

Results

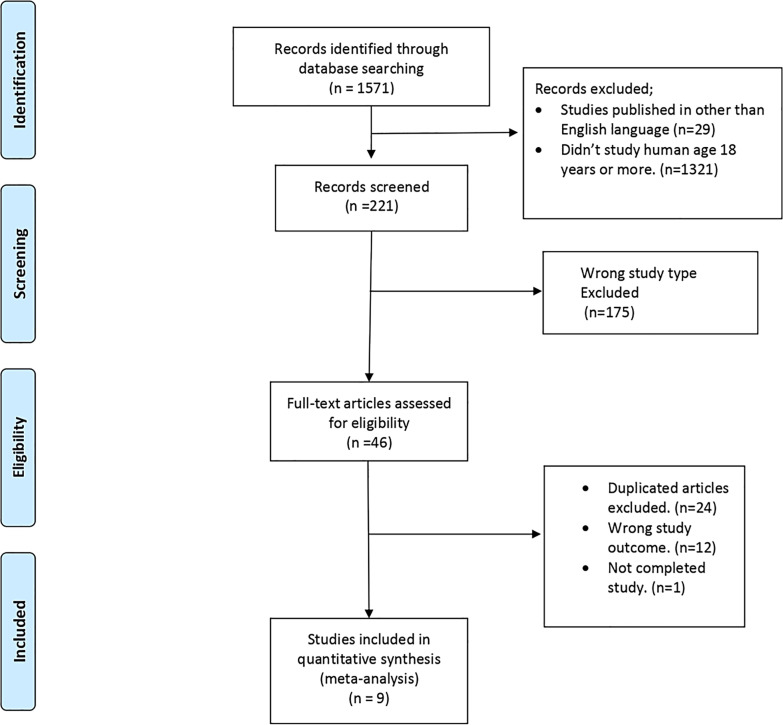

The search revealed a total of 1,571 studies; 29 of these were excluded as they were in a language other than English. 1,321 studies were excluded as they did not study humans aged 18 years or more. 175 studies were excluded as the study design was not an RCT, 12 were excluded for not assessing the effects of IF in cognitive decline, 24 were duplicates, and 1 study was incomplete. Thus, 9 studies met the inclusion criteria. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are displayed in Table 1, and the study selection is summarized in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Studies that assessed the effect of IF in dementia in humans of 18 years old and above | Studies that did not assess the effect of IF on dementia in humans of 18 years old and below |

| Studies published in English language | Studies published in languages other than English that cannot be reliably translated |

| RCT | Other study types and RCTs that were not assessing the effect of IF or similar interventions on dementia |

| Both statistically and non-statistically significant studies |

RCT, randomized controlled trial; IF, intermittent fasting.

Fig. 1.

Search flowchart and articles selection.

In a large RCT conducted by Espeland et al., 5,145 individuals (59.8% female, mean age 58) with comorbid diabetes and a body mass index (BMI) >35 kg/m2 on unspecified prescription medications were randomized into intensive lifestyle intervention or a control condition with diabetes support and education groups [15]. At baseline, 23% of participants reported at least some difficulty with memory, 12% reported some difficulty with problem-solving, and 16% reported some difficulty with decision-making abilities. Intensive lifestyle intervention included diet modification and physical activity designed to induce weight loss. Subjects were assessed using standardized questionnaires on difficulties with cognitive abilities at baseline and repeatedly over time, in addition to memory, thinking, and problem-solving, decision-making, and the Beck Depression Index-II. It was found that intensive lifestyle interventions were associated with significantly fewer complaints about difficulties in decision-making and problem-solving ability (p = 0.014), especially among overweight but not obese individuals, compared to the diabetes support and education group. However, no overall impact on the development of complaints regarding memory ability was found. Although the intensive lifestyle interventions were shown to have benefits seen at years 8–9 in processing speed (p = 0.008) and executive function (p = 0.11), they were limited to nonobese participants [15]. On the other hand, individuals who had difficulties in cognitive ability at baseline did not show benefits of intensive lifestyle interventions toward reducing the severity of complaints. It was found that intensive lifestyle interventions may have worsened the severity of complaints regarding problem-solving ability among individuals with history of cardiovascular disease [15].

Peven et al. [16] investigated healthy adults (78.4% female) with a BMI ranging from 25.0 to 39.9 kg/m2 (average age 44 years) who were randomized into diet-only, a diet with moderate exercise, and diet with high exercise groups. Overall, working memory, task switching, and inhibitory control tasks were within normal ranges at baseline for all participants. The group randomized to the highest extent of prescribed exercise showed significantly greater improvements in reward processing (p < 0.05) and the Iowa Gambling Task sensitivity score compared to the diet-only group and diet with moderate exercise group (all p ≤ 0.004). There were no significant differences between the diet-only group and the diet with moderate exercise group. As a result, it was suggested that weight loss alone was not sufficient for improvements in executive functions and reward processing, while engaging in exercise yielded greater cognitive gains over 12 months than weight loss through diet alone. The significant improvement in performance in the Iowa Gambling Task suggests that some cognitive processes (i.e., reward processing) might be more sensitive to the effects of exercise than others. This improvement was dose-dependent, which indicates that only higher engagement in exercise improved sensitivity to rewards [16].

Kim et al. [17] investigated the effects of intermittent and continuous energy restriction on human hippocampal neurogenesis-related cognition. 45 healthy adults with an average age of 52.8 (78.2% females) and a baseline BMI of 30 kg/m2 were randomized into continuous energy restriction group (n = 22) with a daily 500 kcal deficit and intermittent energy restriction group (n = 23) who consumed 600 kcal for two consecutive days each week. Recognition memory was the cognitive domain that was measured at baseline and endpoints, which was within the normal range for all participants. All endpoint measurements were taken in duplicate after 4–5 weeks of the dietary interventions. To test the acute effect of fasting, one endpoint measurement was taken following the 2 days of a very low-calorie diet for the intermittent energy restriction group and another one after a minimum of 2 days of normal eating. No significant differences were noted between the two diets in terms of cognitive improvement. A significant decrease in recognition memory performance in the intermittent energy restriction group was noted. Recognition memory performance was assessed using a recognition score. The intermittent energy restriction group had a significant reduction in the recognition score (p = 0.007), which was not observed in the continuous energy restriction group [17].

Martin et al. [18] assessed 48 overweight adults with an average age of 37 years and a BMI of 27.87 (60.0% female) who were randomized for 6 months into a control group (weight maintenance diet), CR with a 25% CR based on baseline energy requirements, a CR plus structured exercise (12.5% CR plus 12.5% increase in energy expenditure via structured exercise), and a low-calorie diet group (890 kcal/d liquid formula diet until 15% of body weight is lost, followed by weight maintenance). Rey auditory and verbal learning tests were used to assess verbal memory, while auditory consonant trigram was used to assess short-term memory and retention, which were the normal baseline for all participants. The Benton visual retention test which is a reliable measure of visual perception and memory, and Conners’ Continuous Performance Test-II were used to assess attention/concentration, inattentiveness, and impulsivity. Participants completed tests of cognitive function during a 5-day inpatient stay at baseline and months 3 and 6. The CR trial did not indicate a significant change in short-term verbal memory at month 3 or month 6 and did not indicate a change in performance on trials I-IV among the groups. Performance on the Auditory Consonant Trigram for 9- and 18-s delay conditions trials improved significantly at months 3 (p < 0.05) and 6 (p < 0.01). Visual perception and memory were not negatively affected during the trial. Conners’ Continuous Performance Test-II, and inattentiveness decreased significantly at month 3 (p < 0.01), indicating performance improvement, but it was not noted at month 6 [18]. Trevizol et al. [19] aimed to investigate the effect of CR on interleukin (IL)-6 and the effect of IL-6 on cognitive functions. Individuals with an average age of 37.8 years (68.5% female) and a BMI ranging from 22 to 28 kg/m2 were randomized to CR and ad libitum diet groups for 2 years. Participants were also advised to exercise. The cognitive performance and the spatial working memory were assessed using the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery. The baseline mean for all participants was within the normal range for spatial working memory scores. Sleep quality was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index questionnaire. The Profile of Mood States was used to evaluate transient mood states. In addition, the intensity of psychological stress was also assessed using the Perceived Stress Scale. It was found that both groups showed a decrease in peripheral levels of IL-6 at 12 and 24 months. There was an effect of time on IL-6 considering the whole sample (p = 0.030); however, participants who practiced lower levels of exercise had a positive association between caloric intake and IL-6 levels, but a negative association was noted among those who practice moderate-to-high levels of exercise. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index improved with time at 12 (p = 0.003) and 24 months (p = 0.008) in the CR group. The researchers also observed effects of time on mood disturbances at 12 months (p = 0.038) and 24 months (p = 0.005), on perceived stress at 12 and 24 months (p = 0.386 and p = 0.022, respectively), and on total metabolic equivalent at 12 months (p = 0.119) and 24 months (p = 0.009) in the CR group. An effect of IL-6 was also observed on spatial working memory (p = 0.004), mainly at month 24 (p = 0.093) only in the CR group [19].

Horie et al. [20] assessed 80 obese subjects aged ≥60 years (83.7% female) with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and an average BMI of 35.5 kg/m2 who were randomized into two groups: conventional medical care and brief lifestyle consultation only, and conventional medical care and CR counseling with a nutritionist. Participant baseline cognitive scores were within MCI ranges in global cognition, memory, executive function, attention, and/or psychomotor speed. After 12 months of the interventions, it was found that global cognition (p = 0.0001) and verbal memory (p = 0.0001) were correlated with a decreased BMI. Moreover, these findings were more correlated with younger patients (p < 0.05), which may indicate that starting the intervention earlier might be associated with better outcomes. In addition to that, a decrease in BMI was more beneficial for apolipoprotein E (APOE) ɛ4 carriers. It was found that a decrease in carbohydrate intake was associated with improvement in verbal memory, executive function, subjective complaints (p < 0.05). Decreased fat intake was also associated with improvements in verbal memory. Moreover, the authors suggested that cognitive change showed a dose-response relationship with variation in BMI [20].

Smith et al. [21] (2010) study assessed 124 healthy overweight or obese (BMI: 25–40 kg/m2) and sedentary adults (average age 52.4 years, 63.0% females) with elevated blood pressure (systolic blood pressure 130–159 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure 85–99 mm Hg) and without a clear diagnosis of dementia or MCI; these subjects were randomized into 1 of 3 groups based on the intervention: (i) a group that used DASH diet alone, (ii) DASH + weight management, and (iii) usual care control group without any intervention. Participants were assessed for the domains of executive function, memory, learning, and psychomotor speed before and after a 4-month treatment program. Participants had a baseline of normal neurocognitive measures across all domains. The DASH + weight management group received the DASH dietary intervention and also participated in a behavioral weight management program consisting of supervised aerobic exercise and behavior modification such as CR. After 4 months, it was found that the DASH + weight management group was associated with improvement in executive function, memory learning, and psychomotor speed performance compared to the control group (p < 0.05). Individuals who were on the DASH diet without losing weight or exercising exhibited improvement in psychomotor speed performance compared to controls but without improvement in executive function or memory learning. It was noted that improvements in executive function, memory, and learning in the DASH + weight management group were mediated by improved cardiorespiratory fitness, whereas improvements in psychomotor speed were mediated by weight loss. The beneficial effects in the DASH + weight management group were particularly pronounced for individuals with higher levels of carotid artery intima-medial thickness at baseline (p < 0.05), which may lead to a beneficial effect of IF and CR on patients with cerebrovascular accidents; this may minimize the risk of development of vascular dementia.

Prehn et al. [22] examined 37 postmenopausal women with an average age of 60 years and a BMI >27 kg/m2 who were randomized into the CR group (n = 19) or the control group (n = 18). Participants were assessed at baseline, after 12 weeks, and at 16 weeks. The CR group had 8 weeks of CR in the first 8 weeks of the 12 weeks, which was the weight-loss phase, supported by a low-caloric formula diet (800 kcal/day). At baseline, patients had normal ranges of recognition memory scores and were globally screened for cognitive impairment using the Mini-Mental State Examination. Participants were also advised to increase physical activity to reach a goal of 150 min of activity per week. The weight-loss phase was followed by an additional 4 weeks of weight maintenance phase, in which the CR group was advised to consume an isocaloric diet. Structural and functional neuroimaging and blood collection were done at 3 time points [22]. Subjects were tested in verbal recognition memory performance using the German version of the Auditory Verbal Learning Test; neuropsychological testing assessed sensorimotor speed, attention, and executive functions and included digit span and trail-making test parts A and B, Stroop color-word, and verbal fluency tests. Changes in effect and mood were measured using the Beck Depression Inventory, the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. After 12 weeks, subjects in the CR group showed significant weight loss (p < 0.001). The CR group was found to have an improvement in memory (p < 0.01), learning (p = 0.001), and delayed recall (p = 0.04). However, no significant improvement in recognition and memory was found after 16 weeks. Additionally, during the weight-loss phase, the CR group showed an improvement in processing speed after 12 (p = 0.03), and 16 weeks (p < 0.001), Stroop color-word interference at 12 (p = 0.008) and 16 weeks (p < 0.001), and a reduction in Beck's depression score at 12 (p = 0.003), and 16 weeks (p < 0.001) [22]. A significant increase in gray matter density in the bilateral inferior gyrus was found after 12 weeks in the CR group compared with the control group (p < 0.05). Interestingly, the gray matter density increased in the right hippocampus. The increase in gray matter density was previously reported to be linked to an improvement in cognitive function [22]. Furthermore, gray matter volume reductions in the CR group were found in the right olfactory cortex, the left postcentral gyrus, and the right cerebellum. However, no significant increase in the gray matter density was noted after 16 weeks in the CR group compared with the control. Interestingly, the increase in gray matter volume induced by CR was associated with metabolic changes and improved glycemic control [22].

Cheatham et al. [23] randomized 42 healthy overweight females with an average age of 35 years and BMI of 27.8 kg/m2 who received a high-glycemic or low-glycemic diet and one of two levels of CR (10% or 30% relative to baseline energy requirements) groups. Baseline cognitive function was within the normal range and was measured using reaction time, vigilance, short-term memory, attention, and language-based logical reasoning. A battery of tests assessing mood and cognitive function administered at baseline and at month 6 of CR revealed no significant difference. In addition, the percent of weight change did not correlate with any change in the score for cognitive function, regardless of whether a high- or low-glycemic weight-loss diet was maintained for 6 months. However, randomization to the high-glycemic diet was associated with a relatively negative change in the manifestation of subclinical depression (p < 0.04) over time compared to randomization to the low-glycemic diet [23].

Measures of Effectiveness of Research

A thorough review of the included studies was carried out to assess the quality of the selected studies and determine the risk of bias in each study. GRADE tool was utilized to assess the quality of the included studies. Based on our assessments of the overall quality of evidence using the GRADE tool for each outcome of the included RCTs, the evidence was “high quality” as there was no serious risk of bias reported in the studies.

Risk of Bias

Peven et al. [16] and Kim et al. [17] studies had a high-risk detection bias due to the absence of blinding; the studies of Martin et al. [18] and Trevizol et al. [19] had insufficient information to define “low-risk” or “high-risk” detection bias due to lack of clarity on the presence of the blinding in the statistical analysis of the reported outcome. Peven et al. [16] study had a high attrition bias due to missing outcome data. The risk of bias in each study is summarized in Table 2. Due to the nature of interventions used in the included studies, there was no blinding of participants; however, the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding, and therefore, all the studies had a low-risk performance bias.

Table 2.

Risk of bias and quality of evidence of the included studies

| Study | Selection bias | Performance bias | Detection bias | Attrition bias | Reporting bias | Other bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| random sequence generation | allocation concealment | blinding of participants and personnel | blinding of outcome assessor | incomplete outcome data | selective reporting | ||

| Prehn et al. [22] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Kim et al. [17] | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Low |

| Horie et al. [20] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Martin et al. [18] | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

| Cheatham et al. [23] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Peven et al. [16] | Low | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low |

| Espeland et al. [15] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Smith et al. [21] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Trevizol et al. [19] | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

Discussion

A comprehensive review was performed on the included randomized controlled trials. All studies consisted of populations with high percentages of females (>50%) and high BMI (>25 kg/m2). 4 out of the 9 studies reported high levels of efficacy of CR or dieting on cognitive functions with statistical significance ranging from p = 0.04 to p = 0.001. However, there was a negative effect of CR on subjects, especially those with cardiovascular disease, impacting problem-solving ability of those involved in the studies [15]. Three studies have found that dieting or CR alone is not sufficient for the improvement of cognitive functions and that exercise has a higher effect on cognition. None of the studies reported adverse effects of IF. A complete summary of the studies included is displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of articles on the role of IF in dementia management in humans

| Study name (year) | Population | Methodology | Outcomes and conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prehn et al. [22] | 37 postmenopausal women aged 40–80 years old with a BMI >27 kg/m2 | Participants were randomized into • CR group (n = 19) • Control group (n = 18) and assessed at baseline, after 12 weeks, and after 16 weeks. CR group had 8 weeks of 800 kcal/day, following 4 weeks of weight maintenance phase |

• After 12 weeks, CR group found to have a better memory performance, learning, delayed recall compared to the control group • No significant improvement in recognition and memory performance found after 16 weeks • A significant increase in gray matter density in bilateral inferior frontal gyrus in the CR compared to the control group after 12 weeks (p < 0.05) but not at 16 weeks |

|

| Trevizol [19] | 220 subjects, ages 21–50 with an initial BMI of 22–28 | Participants were randomized for 2 years to • 25% CR (n = 145) • Ad libitum diet (n = 75) Possible moderator effects of sleep problems, mood disturbances, perceived stress, and physical activity on longitudinal changes of IL-6 levels in the sample, as well as the effects of CR. |

• Both groups displayed a decrease in IL-6 peripheral levels in 12 and 24 months • A reduction in IL-6 level was associated with improvements in working memory tests, and to a greater degree working memory tasks |

|

| Horie et al. [20] | 80 participants with MCI, ages 60 and above | Participants were randomized into 2 groups • Conventional medical care and brief lifestyle change counseling (n = 40) • Conventional medical care and CR counseling with nutritionist (n = 40) Subjects were followed up for 12 months |

• A decrease in BMI through CR in obese subjects with MCI was safe and correlated with improvements in memory, executive function, global cognition, and language; this association was strongest in younger seniors and in APOE4 carriers | |

| Kim et al. [17] | 45 healthy, non-smoking subjects aged 35–75 years with a waist circumference of greater than 102 cm in men and 88 cm in women | Subjects were randomized into • Continuous CR (n = 22); with a daily deficit of 500 kcals • Intermittent CR (n = 23); 600 kcal for two consecutive days each week All endpoint measurements were taken in duplicate after four to 5 weeks of the dietary intervention |

• No significant difference in cognitive changes between the two diets • A significant decrease in recognition memory performance in the intermittent CR group compared to the continuous CR group |

|

| Martin et al. [18] | 48 overweight (BMI 25–30 kg/m2) adults ages 25–50 years |

Participants were randomized for 6 months to • Control (weight maintenance diet) (n = 12) • 25% CR (n = 12) • CR plus structured exercise (12.5% CR plus 12.5% increase in energy expenditure via structured exercise) (n = 12) • Low-calorie diet (890 kcal/d liquid formula diet until 15% of body weight was lost, followed by weight maintenance) (n = 12) |

• CR trial did not indicate a significant change in short-term verbal memory at 3- or 6-month follow-up • Performance on the Auditory Consonant Trigram for 9- and 18-second delay conditions trials improved significantly at months 3 and 6 months • Visual perception and memory were not negatively affected during the trial |

|

| Cheatham et al. [23] | 46 healthy, overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2) adults ages 20–42 years | Subjects were randomized to receive a high-glycemic or low-glycemic diet and one of two levels of CR (10% or 30% relative to baseline energy requirements). 34 subjects randomized to the 30% CR groups and 12 subjects to the 10% CR groups | • No effect on changes in cognition in either high- or low-glycemic weight loss at 6 months follow-up • High-glycemic diet was associated with increase signs of subclinical depression |

|

| Peven et al. [16] | 125 subjects aged 18–55 with BMI ranging from 25.0 to 39.9 kg/m2 | Subject were randomized for a 12-month follow-up into • Diet only (n = 50); 1,200–1,800 kilocalories per day (kcal/day) based on baseline body weight • Diet + moderate exercise (n = 30) prescribed exercise regimen progressed from 100 to 150 min per week by week 9 of the intervention • Diet + high exercise (n = 45), prescribed exercise that progressed from 100 to 250 min per week by week 25 |

• Weight loss alone was not sufficient to induce improvements in executive functions and reward processing, and supported studies that did not show intervention effects on cognition • Engaging in exercise yielded greater cognitive gains over a 12-month follow-up than weight loss through diet alone |

|

| Smith et al. [21] | 124 overweight (BMI from 25 to 40 kg/m2) | Participants were randomized into • DASH diet alone (n = 38) • DASH + weight management (n = 43) • Usual care control (n = 43) Following assessment of executive function, memory, learning, and psychomotor speed before and after a 4-month treatment program |

DASH diet associated with CR and aerobic exercise improved neurocognitive performance among individuals with high blood pressure, especially among individuals with poorer vascular health | |

| Espeland et al. [15] | 5,145 subjects aged 45–76 years, with BMI >25 kg/m2 overweight or obese with type 2 diabetes, and with no major cognitive deficits | Participants randomly assigned for a 10-year follow-up to • Intensive lifestyle intervention (n = 2,540), daily calorie goal (1,200–1,800 based on initial weight), and ≥175 min/week physical activity • Control diabetes support and education (n = 2,544) Participants were queried about difficulties with three cognitive abilities at baseline and repeated over time. Memory, thinking and problem-solving, decision-making, and depression |

• Intensive lifestyle intervention was associated with fewer complaints about difficulties in decision-making and problem-solving ability, especially in nonobese, but not memory deficit It was found that intensive lifestyle intervention may have worsened the severity of complaints about problem-solving ability among individuals with cardiovascular disease history |

APOE, apolipoprotein E; BMI, body mass index; CR, caloric restriction; DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension; IF, intermittent fasting; IL-6, interleukin-6; MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

As mentioned earlier, pharmacotherapy had shown limited benefits in the management of dementia [14], and as a result, lifestyle modification (e.g., diet, physical activity) and the management of chronic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension have been suggested to have a role in management and prevention of dementia [14]. Many studies and scholars have investigated the effect of dietary modifications in the management and prevention of dementia. This review included the RCTs that assessed the impact of dieting, including IF on cognition. Four of the 9 included studies have noted a positive effect of diet or IF on cognitive functions [15, 19–21]. These findings highlight how dieting may be used as an effective and safe intervention in the prevention and management of cognitive decline, especially if exercise is engaged with the intervention; however, robust conclusions are limited as the statistics were correlational with varying strengths and the population was predominantly female with a high BMI.

Limitations

This review has some limitations; first, there were only a limited number of studies discussing specifically the effect of IF on cognitive decline; some of the studies elicited by the above search assessed other types of interventions that may mimic IF, such as decreasing the caloric intake without a complete fasting period, weight loss, DASH diet, blood pressure reduction, and exercise. It is possible that observed cognitive benefits were associated more with the other interventions rather than with IF or a combination of all variables. Most of the selected studies in this review had a short follow-up period (≤24 months), with the only exception of Esplanade et al.’s, an RCT which spanned 10 years with a large sample cohort (n = 5,145). This may confound the results as dieting or IF may be more effective in the long run. Most of the studies were small with the sample sizes ranging from 37 to 220 subjects per sample. There was no standardized method to assess the outcomes of the interventions on the cognitive functions among the analyzed studies, and that might also affect the results. Moreover, all the included studies in this review have investigated subjects without diagnosed dementia or MCI; therefore, the effect of diet on the progression of dementia was not clear and could not be assessed properly. This review included only RCTs to ensure the highest accuracy and quality of the current evidence. However, it is important to emphasize that the baseline population demographics in the assessed RCTs were predominantly postmenopausal females with obesity, and as a result, robust conclusions cannot be made or generalized to other populations. It is unclear but quite possible that the exclusion of non-statistically significant observational studies such as cohort studies, case reports, case series, and other systematic and narrative review studies might skew the results and the reported outcomes. For each of the included studies, cognition was measured in different ways and across different domains. As a result, IF may have important negative consequences on individuals that were not elucidated in this review.

Future Directions

There is a requirement for RCTs with a large cohort, longer follow-up, and standardized outcome assessment for the effect of IF in people affected by dementia. Investigating the different types of IF to determine how the number of fasting hours and/or the amount of CR can affect the outcome of IF in the management of dementia and prevention is needed. In addition to study design, side effects of IF are not yet clearly understood; thus, more studies are needed to determine the impact of IF in humans on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular health. More insight is needed into the synergistic effect of weight change and IF on cardiovascular health and cognition in adults and IF and CR in older subgroups. There is evidence that there are cardiometabolic benefits of IF, including decreasing blood pressure, insulin resistance, oxidative stress, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglyceride levels while producing clinically significant weight loss [24]. Isolated RCTs are needed to compare the effect of IF on cognitive functions when combined with other lifestyle interventions such as exercise, weight loss, and blood pressure reduction interventions. All studies that met inclusion criteria in this review consisted of over 50% of postmenopausal female participants with a BMI >25 kg/m2 without baseline cognitive impairments. A comprehensive review on the impact of gender, BMI, age, and baseline cognitive function on IF is warranted as perimenopausal women and older adults are often excluded from research due to differences in metabolism compared to males and existent comorbidities. Low-density lipoprotein and weight loss have a larger decrease in premenopausal women compared to postmenopausal women [25]. This suggests that there may be significant differences in baseline between age and menopausal status, potentially due to hormones such as estrogen, that require further investigation. Additionally, IF in males >50 years of age showed increased weight loss compared to females, suggesting that gender and age differences are important to consider while assessing IF [26]. A study conducted by Li et al. [27] found that older individuals (>70 years old) with pre-existing MCIs showed worsening orientation to place and attention after IF. as a result, caution is necessary for older adults with pre-existing cognitive impairments. Importantly, standardized cognitive assessments across all domains are needed to assess IF in future studies. The mechanism of action of IF in the prevention and management of cognitive decline is not fully understood; as a result, future investigations on the effect of IF and/or CR on patients of different ages diagnosed with different types of diseases that affect cognition (e.g., different subtypes of dementia such as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, etc.) are needed to understand the impact on illness trajectory.

Conclusion

IF may have a role in the prevention and management of dementia as it may improve cognitive function; however, this is still controversial and should be explored further. Dieting and IF are considered safe interventions, and no adverse effects were linked to them in the reviewed studies; however, evidence is limited as there are only 9 low-quality RCTs that assessed the impact of IF on cognition are existing up to date. As a result, the negative impact of IF on individuals is not elucidated in this review. Caution should be used in individuals with comorbid cardiovascular disease as there were negative effects noted in problem-solving domains. Special consideration should be given to individuals with pre-existing eating disorders and other conditions as well as older individuals who may react differently to IF. Dieting may have better outcomes if added to lifestyle modifications such as exercise as exercise has been shown to also have positive effects on cognition. It is still difficult to conclude that the driver of these changes is only IF, diet, exercise, weight loss, or better vascular care, and thus further research is warranted.

Statement of Ethics

An ethics statement is not applicable because this study is based exclusively on published literature.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

No funding was received.

Author Contributions

Helen Senderovich: conception of the study, data acquisition, interpreting the results, drafting and revising the manuscript, and responsible for approval of the final version; Othman Farahneh: conception of the study, data acquisition, interpreting the results, and drafting and revising the manuscript; Sarah Waicus: drafting and revising the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding Statement

No funding was received.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Klimova B, Dziuba S, Cierniak-Emerych A. The effect of healthy diet on cognitive performance among healthy seniors: a Mini Review. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020;14:325. 10.3389/fnhum.2020.00325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Challa HJ, Ameer MA, Uppaluri KR. DASH diet to stop hypertension [Internet]. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. [cited 2022 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482514/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tangney CC, Li H, Wang Y, Barnes L, Schneider JA, Bennett DA, et al. Relation of DASH- and mediterranean-like dietary patterns to cognitive decline in older persons. Neurology. 2014;83(16):1410–6. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alanko V, Udeh-Momoh C, Kivipelto M, Sandebring-Matton A, Magiatis P, Martinez-Gonzalez MA. Mechanisms underlying non-pharmacological dementia prevention strategies: a translational perspective. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2022;9(1):3–11. 10.14283/jpad.2022.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Scarmeas N, Anastasiou CA, Yannakoulia M. Nutrition and prevention of cognitive impairment. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):1006–15. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mattson MP, Longo VD, Harvie M. Impact of intermittent fasting on health and disease processes. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;39:46–58. 10.1016/j.arr.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Patterson RE, Laughlin GA, LaCroix AZ, Hartman SJ, Natarajan L, Senger CM, et al. Intermittent fasting and human metabolic health. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(8):1203–12. 10.1016/j.jand.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Manzanero S, Erion JR, Santro T, Steyn FJ, Chen C, Arumugam TV, et al. Intermittent fasting attenuates increases in neurogenesis after ischemia and reperfusion and improves recovery. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34(5):897–905. 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arumugam TV, Phillips TM, Cheng A, Morrell CH, Mattson MP, Wan R. Age and energy intake interact to modify cell stress pathways and stroke outcome. Ann Neurol. 2010;67(1):41–52. 10.1002/ana.21798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bruce-Keller AJ, Umberger G, McFall R, Mattson MP. Food restriction reduces brain damage and improves behavioral outcome following excitotoxic and metabolic insults. Ann Neurol. 1999;45(1):8–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Visioli F, Mucignat-Caretta C, Anile F, Panaite SA. Traditional and medical applications of fasting. Nutrients. 2022;14(3):433. 10.3390/nu14030433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Longo VD, Anderson RM. Nutrition, longevity and disease: from molecular mechanisms to interventions. Cell. 2022;185(9):1455–70. 10.1016/j.cell.2022.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Currenti W, Godos J, Castellano S, Caruso G, Ferri R, Caraci F, et al. Association between time restricted feeding and cognitive status in older Italian adults. Nutrients. 2021;13(1):191. 10.3390/nu13010191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cremonini AL, Caffa I, Cea M, Nencioni A, Odetti P, Monacelli F. Nutrients in the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:9874159. 10.1155/2019/9874159.:no pagination. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Espeland MA, Dutton GR, Neiberg RH, Carmichael O, Hayden KM, Johnson KC, et al. Action for health in diabetes (Look AHEAD) research group. Impact of a multidomain intensive lifestyle intervention on complaints about memory, problem-solving, and decision-making abilities. The action for health in diabetes randomized controlled clinical trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018 Oct 8;73(11):1560–7. 10.1093/gerona/gly124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peven JC, Jakicic JM, Rogers RJ, Lesnovskaya A, Erickson KI, Kang C, et al. The effects of a 12-month weight loss intervention on cognitive outcomes in adults with overweight and obesity. Nutrients. 2020 Sep 29;12:2988. 10.3390/nu12102988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim C, Pinto AM, Bordoli C, Buckner LP, Kaplan PC, Del Arenal IM, et al. Energy restriction enhances adult hippocampal neurogenesis-associated memory after four weeks in an adult human population with central obesity; a randomized controlled trial. Nutrients. 2020 Feb 28;12(3):638. 10.3390/nu12030638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Martin CK, Anton SD, Han H, York-Crowe E, Redman LM, Ravussin E, et al. Examination of cognitive function during six months of calorie restriction: results of a randomized controlled trial. Rejuvenation Res. 2007 Jun;10(2):179–90. 10.1089/rej.2006.0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Trevizol AP, Brietzke E, Grigolon RB, Subramaniapillai M, McIntyre RS, Mansur RB. Peripheral interleukin-6 levels and working memory in non-obese adults. A post-hoc analysis from the CALERIE study. Nutrition. 2019 Feb;58:18–22. 10.1016/j.nut.2018.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Horie NC, Serrao VT, Simon SS, Gascon MRP, Dos Santos AX, Zambone MA, et al. Cognitive effects of intentional weight loss in elderly obese individuals with mild cognitive impairment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Mar;101(3):1104–12. 10.1210/jc.2015-2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smith PJ, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Craighead L, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Browndyke JN, et al. Effects of the dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet, exercise, and caloric restriction on neurocognition in overweight adults with high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2010;55(6):1331–8. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.146795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Prehn K, Jumpertz von Schwartzenberg R, Mai K, Zeitz U, Witte AV, Hampel D, et al. A. caloric restriction in older adults-differential effects of weight loss and reduced weight on brain structure and function. Cereb Cortex. 2017 Mar 1;27(3):1765–78. 10.1093/cercor/bhw008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cheatham RA, Roberts SB, Das SK, Gilhooly CH, Golden JK, Hyatt R, et al. Long-term effects of provided low and high glycemic load low energy diets on mood and cognition. Physiol Behav. 2009 Sep 7;98(3):374–9. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Varady KA, Cienfuegos S, Ezpeleta M, Gabel K. Cardiometabolic benefits of intermittent fasting. Annu Rev Nutr. 2021;41:333–61. 10.1146/annurev-nutr-052020-041327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lin S, Lima Oliveira M, Gabel K, Kalam F, Cienfuegos S, Ezpeleta M, et al. Does the weight loss efficacy of alternate day fasting differ according to sex and menopausal status? Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2021;31(2):641–9. 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Varady KA, Hoddy KK, Kroeger CM, Trepanowski JF, Klempel MC, Barnosky A, et al. Determinants of weight loss success with alternate day fasting. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2016;10(4):476–80. 10.1016/j.orcp.2015.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li J, Li R, Lian X, Han P, Liu Y, Liu C, et al. Time restricted feeding is associated with poor performance in specific cognitive domains of suburb-dwelling older Chinese. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):387. 10.1038/s41598-022-23931-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.