Abstract

Background

Chronic subdural haematoma (CSDH) is increasingly common. Although treatment is triaged and provided by neurosurgery, the role of non-operative care, alongside observed peri-operative morbidity and patient complexity, suggests that optimum care requires a multi-disciplinary approach. A UK consortium (Improving Care in Elderly Neurosurgery Initiative [ICENI]) has been formed to develop the first comprehensive clinical practice guideline. This starts by identifying critical questions to ask of the literature. The aim of this review was to consider whether existing systematic reviews had suitably addressed these questions.

Methods

Critical research questions to inform CSDH care were identified using multi-stakeholder workshops, including patient and public representation. A CSDH umbrella review of full-text systematic reviews and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA statement (CRD42022328562). Four databases were searched from inception up to 30 April 2022. Review quality was assessed using AMSTAR-2 criteria, mapped to critical research questions.

Results

Forty-four critical research questions were identified, across 12 themes. Seventy-three articles were included in the umbrella review, comprising 206,369 patients. Most reviews (86.3%, n=63) assessed complications and recurrence after surgery. ICENI themes were not addressed in current literature, and duplication of reviews was common (54.8%, n=40). AMSTAR-2 confidence rating was high in 7 (9.6%) reviews, moderate in 8 (11.0%), low in 10 (13.7%) and critically low in 48 (65.8%).

Conclusions

The ICENI themes have yet to be examined in existing secondary CSDH literature, and a series of new reviews is now required to address these questions for a clinical practice guideline. There is a need to broaden and redirect research efforts to meet the organisation of services and clinical needs of individual patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00701-023-05618-2.

Keywords: Chronic subdural haematoma, Umbrella review, Reporting quality, PRISMA, AMSTAR, ICENI

Introduction

A chronic subdural haematoma (CSDH) is a collection of aged blood lying in the subdural space [14]. Many CSDH are identified incidentally, but most present with symptoms akin to a slowly evolving stroke [29]. For symptomatic CSDH, surgical evacuation is considered the gold standard of care. CSDHs are associated with age, frailty and co-morbidity and are an increasingly common neurosurgical condition, with operative cases predicted to rise by more than 50% in the next 20 years, as a consequence of ageing populations [20, 30]. In the USA, it is forecast to become the most performed neurosurgical operation by 2030 [2]. CSDHs are associated with a 1-year mortality of up to 32% [18], and significant morbidity either from surgery, or from direct sequalae of disease [18, 28]. The rising incidence among elderly patients, and the associated morbidity and mortality makes CSDH, and its management, an important clinical problem [1, 23].

Targeted clinical research in CSDH, such as investigations into the use of surgical drains [24] and adjuvant steroid therapy [13], has led to a growing evidence base for management of CSDH. However, everyday clinical practice may conflict with this [3]. Moreover, inconsistencies between study findings can leave room for interpretation and barriers to implementation [13, 17, 21]. Further targeted research should only address specific knowledge gaps, and many additional uncertainties that remain within clinical practice may exist [26, 31]. This appears relevant to CSDH, where research has focused on procedural treatment such as surgery within specialist centres, consequently overlooking the burden of disease managed non-operatively, long-term care [9, 27] or challenges that may be encountered by other stakeholders involved in CSDH care, such as Geriatrics, Emergency and Acute Medicine, Anaesthesia and General Practice (Supplementary Figure 1).

These challenges have been recognised by the Improving Care in Elderly Neurosurgery Initiative (ICENI) group, a multi-disciplinary group of experts and stakeholders, who have come together to create comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for CSDH [27]. Clinical practice guidelines are an important tool to translate evidence into practice, enabling multiple sources of evidence to be considered, but also enabling knowledge gaps to be identified, often in the short-term bridged with consensus informed by expert opinion [31]. Aligned with guideline methodology, ICENI has convened a broad multidisciplinary group of professionals, alongside patient and public participants [27]. Working in groups, covering different components of the care pathway, these stakeholders have developed practice-relevant questions to inform targeted systematic reviews and develop clinical practice recommendations.

Recognising that relevant systematic reviews may already exist and to avoid duplicated effort, this guideline process included a framework to use existing reviews, specifically by conducting an ‘umbrella review’ (a systematic review of systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses), identifying those aligned with the guideline questions and using a pre-defined quality threshold for inclusion, including a consideration of their recency.

The primary objective of this article is therefore to report on this gap analysis. However, as the guidelines questions can be considered to represent the needs for clinical practice across CSDH care, and systematic review a surrogate of research activity or direction [5], this analysis can also provide an overview of how ongoing research aligns with current clinical practice need. This is considered and discussed as a secondary objective.

Methods

Identification of guideline questions

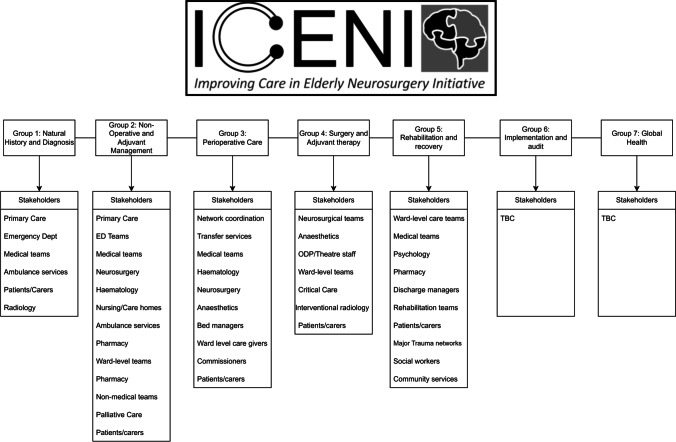

The ‘Improving Care in Elderly Neurosurgery Initiative’ is a multidisciplinary working group which, with the input and support of professional bodies such as the Society of British Neurological Surgeons (SBNS) and the Neuroanaesthesia and Critical Care Society, is developing a clinical practice guideline for CSDH. The process is supported by further allied organisations including The Neurological Alliance and British Association of Neuroscience Nursing with methodological support from the THiS institute. The group was formed due to a shared consensus that many aspects of CSDH care were unstandardised. Funding was independently secured through application to the National Institute of Academic Anaesthesia with the SBNS identified as the lead sponsor and forward custodian of the final guideline [27]. Building on an initial meeting, working groups were convened to address five areas of CSDH care, i.e. diagnosis, non-operative management, surgical care, peri-operative care and rehabilitation, with work streams around Implementation and Global Health planned at a later stage. For each theme, a dedicated multidisciplinary working group was formed (Fig. 1), and through facilitated discussion, a provisional list of research questions developed. These were initially reviewed using a workshop for patients and members of the public, before final iterations were approved by the steering committee. These research questions thus provide a comprehensive overview of the requirements for the CSDH evidence base.

Fig. 1.

ICENI consensus and stakeholder groups

Umbrella review

An umbrella review adhering to guidelines outlined by Fusar-Poli and Radua [10] was undertaken to critique the current evidence base. The review was prospectively registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022328562). No changes were made to the original protocol prior to extraction, and anonymised study data are available via the corresponding authors.

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed on 30 April 2022 of 4 databases: Medline, Excerpta Medica Database (Embase), Cochrane Library and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. The exact search strategy for all databases can be found in Supplementary Table 1. We reviewed bibliographies and reference lists of included articles to identify additional studies. Papers were limited to English language due to the feasibility of translation.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included all systematic reviews (SRs) published on CSDH, between 1 January 2000 and 30 April 2022. SRs published prior to 2000 were considered almost certainly out of date. An SR was defined by the Cochrane Collaboration as any published, full-text review that attempts to identify, appraise and synthesise available primary research, using prespecified methodology with an aim at minimising bias [6]. Reviews were also included if they contained the phrase ‘systematic review’ in the title or abstract, or if papers described their search strategy as ‘systematic’ or ‘comprehensive’. Studies were excluded if they were conference abstracts, were correspondence, assessed acute subdural haematoma (ASDH) only, assessed both ASDH and CSDH (and it was not possible to distinguish the two), were literature reviews and were invited editorial reviews. Inclusion was determined by two authors (CSG, KWF), with conflict settled by mutual agreement or involvement of a third author (BMD).

Data extraction

Independent data extraction was performed in duplicate, by two authors (CSG, KWF) using a standardised pre-piloted data collection proforma (Supplementary Table 2). The following variables were extracted: year of publication, country, continent, journal published; type of SR (SR, meta-analysis, umbrella review); whether the review described adhering to the Preferred Reporting in Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines or a similar review had been published prior to its publication; number of studies and participants; review typology; domains; and classification. Reporting quality was assessed by calculating the PRISMA checklist adherence [22], and overall quality of review results calculated according to the Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews-2 tool (AMSTAR-2). An AMSTAR-2 overall interpretation score was calculated (‘high’, ‘moderate’, ‘low’ or ‘critically low’) [25]. Formal risk of bias assessment was not performed.

Definitions

In our review, country was defined as the country of first listed affiliation of the first author. Review typology was defined according to Munn et al. [19], and review domains defined a priori according to the ICENI themes, and separately, a previously defined thematic analysis of CSDH education resources (Gillespie et al, unpublished data, 2022). Manuscripts were considered ‘similar’ if they reported the same research theme as an article published previously (i.e. recurrence rates following middle meningeal artery [MMA] embolization). If the article assessed the same research theme, was not published as part of a ‘review update’ by the same group of authors and was included the same outcomes, it was considered ‘duplicate’.

Analysis

Critical research questions ratified by the ICENI steering group were first grouped into topics by two authors (BMD and DJS). These were then matched to the review topics, with activity or lack of activity summarised using descriptive statistics.

The quality of identified reviews according to AMSTAR-2 was summarised using descriptive statistics, with results for individual components presented separately. Normally distributed variables were summarised with mean and standard deviation (SD), and non-parametric variables as medians and inter-quartile ranges (IQRs). All analysis and graphical representation was performed using R v4.0.2 (ggplot and tidyverse packages).

Results

Critical research questions

Forty-four questions were generated from the ICENI working groups and ratified by the steering committee (Table 1). These were felt to represent 12 distinct themes: anticoagulation (6 questions), communication (6 questions), decision making (2 questions), anaesthesia and surgical scheduling (7 questions), transfer and pathway (7 questions), perioperative care (3 questions), palliative care (3 questions), postop and recovery (5 questions), natural history (2 questions), surgical technique (3 questions) and MMA embolization (3 questions).

Table 1.

ICENI research questions, and themes

| Theme | Q | Research questions |

|---|---|---|

| Anticoagulant | 13 | In patients with cSDH who are not undergoing surgery (P) do antithrombotic drugs (e.g. anticoagulants, antiplatelets) (I) increase the risk of disease related complications (e.g. expansion (O) compared to those who do not take such agents (C) |

| 14 | In patients with cSDH who are not undergoing surgery (P) does discontinuation of antithrombotic agents (I) improve disease and safety related outcomes (O) compared to continuing these agents (C) | |

| 15 | In patients with cSDH (P) do antithrombotic drugs (e.g., anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents) (I) increase the risk of treatment related complications (O) compared to those who are not taking such drugs(C)? | |

| 16 | Does early (I) vs late (C) recommencement of anticoagulation increase the risk of recurrence or other complications (O) in patients recovering from cSDH surgery? | |

| 17 | In patients with cSDH scheduled for surgery who are taking an antithrombotic medication (P) what is the impact of using pharmacological or other (e.g. platelet) reversal (I) on perioperative outcomes (O) compared to standard care (C) | |

| 18 | In patients with cSDH who have undergone surgery (P) what is the impact of early (<72 hrs) (I) commencement of prophylactic LMWH on perioperative thromboembolic and rebleeding (incl recollection) (O) compared to standard care (C) | |

| Communication and decision-making | 1 | In patients with a radiological finding of a cSDH (P) does the use of standardised tools for neurosurgical referral and intervention (I) improve patient, system, and clinical outcomes (O) compared to standard care (C) |

| 2 | In patients with a symptomatic, cSDH (P) does active neurosurgical management (including surgery, MME, or adjuvant medical therapies) (I) compared to conservative or medical management (C) improve patient, system, clinical outcomes (O)? | |

| 3 | In patients with an incidental cSDH (P) does active neurosurgical management (including surgery, MME or adjuvant medical therapies) (I) compared to conservative or medical management (C) improve patient, system, clinical outcomes (O)? | |

| 6 | In patients with a cSDH being discussed with a neurosurgeon (P), do standardised communication tools (e.g. structured referral proformas or decision making tools) (I) improve surgical decision making (O) compared to standard care (C)? | |

| 7 | In patients with cSDH being triaged for surgery (P), does the explicit identification and consideration of patient and family recovery priorities (I), improve patient, provider, and clinical outcomes (O), | |

| 8 | In patients with cSDH being triaged for surgery (P) does a patient and family discussion around perioperative risks and benefits led by a specialist (e.g. neurosurgeon) (I) improve patient, provider, and clinical outcomes (O) compared to a non-specialist led discussion? (C) | |

| Anaesthesia and surgical scheduling | 22 | In patients undergoing surgery for cSDH (P) does the use of local anaesthesia (I) versus general anaesthesia (C) improve patient, system, and clinical outcomes (O) |

| 23 | In patients having surgery for cSDH (P) does protocolised or strict blood pressure control (e.g. avoidance of hypotension) (I) improve postoperative outcomes (O) compared to routine management (C) | |

| 24 | In patients having surgery for cSDH (P) does advanced or invasive monitoring (I) improve perioperative blood pressure control (O) compared to routine monitoring (C) | |

| 25 | In patients with a cSDH scheduled for surgery (P) does early surgery (I) improve patient, system, and clinical outcomes (O) compared to routine management (C) | |

| 26 | Do patients with a cSDH scheduled for surgery (P) who face a cancellation / delay / prolonged fasting (I) compared to those who do not (C) haved improved patient, system, and clinical outcomes (O) | |

| 27 | In patients with a cSDH scheduled for surgery (P) does in-hours surgery (I) improve patient, system, and clinical outcomes (O) compared to out-of hours surgery (C) | |

| 41 | In patients undergoing a procedural intervention for chronic subdural haematoma (P) does provision of surgical/procedural/anaesthetic care by a ‘senior’ (I) (i.e. consultant level) provider vs ‘junior’ (i.e. non-consultant level) (C) affect patient, system, and provider outcomes (O) | |

| Transfer and pathway | 9 | In patients with cSDH being transferred for surgery (P) how does an optimized/protocolized transfer (I) compared to routine care (C) affect patient, system, clinical outcomes (O) |

| 10 | In patients with cSDH being transferred for surgery (P) does immediate transfer to tertiary centre (I) compared to routine care (C) improve patient, system, clinical outcomes (O) | |

| 11 | For cSDH patients (P), what is the role of technology (I) (e.g., QR codes, e-communication) compared with standard care (C) in facilitating communication between centres (incl. transfer of relevant patient information)((O | |

| 12 | In patients with CSDH transferred for surgery (P) does repeating blood tests (I) compared to using those communicated from original hospital (C) improve patient, system, clinical outcomes (O) | |

| 30 | In patients presenting to healthcare services with an undiagnosed cSDH (P) do standardised symptom checklists (I) improve time to diagnosis and treatment decision (O) compared to routine care? (C) | |

| 33 | In patients who have undergone interventional treatment for a cSDH and being discharged or transferred to another centre (P), do standardised communication tools (e.g. structured proformas) (I) improve patient, system, and clinical (O) compared to standard care (C)? | |

| 4 | In patients with a CSDH (both operative and non-operative) is their outcome (both patient and clinical) (O) improved if they receive ongoing care (e.g. rehabilitation, medical management) in a specialist (I) (neurosciences or rehabilitation facility) compared to non-specialist (secondary care) setting? | |

| Perioperative care | 19 | Does the use of objective assessment tools (e.g. such as those used in Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment: frailty, cognition, multi-morbidity) to identify and optimise high-risk patients (I) in patients presenting with a cSDH (P) improve patient, system, and clinical outcomes (O) compared to standard care (C) ? |

| 20 | In patients with a cSDH (P) Does protocolised multidisciplinary care (e.g. co-management with a geriatrician) (I) improve patient, system, and clincial outcomes (O) compared to standard care (C)? | |

| 21 | Does assessing and optimising delirium risk (I) in cSDH patients who are scheduled for surgery (P) help to prevent, diagnose and treat this condition (O) compared to standard care? (C) | |

| Palliative Care | 36 | In patients with a symptomatic cSDH suspected not to benefit from treatment (P) does assessment by a nominated specialist (e.g. neurosurgeon) (I) improve diagnostic accuracy, patient, and family relevant outcomes (O) compared to standard care? |

| 37 | Is delivery of palliative care by specialists (e.g. specialist doctor or nurse) (I) associated with improved patient and family outcomes (O) for individuals with cSDH in whom this is felt to be an end-of-life diagnosis (P) compared to non-specialist delivered care (C)? | |

| Postop and recovery | 28 | Does standardised postoperative posture support and mobilisation rules (e.g. routine use of a supine position) (I) improve patient, system, and clinical outcomes (O) after cSDH surgery(P) compared to routine care (C) ? |

| 31 | In patients with a cSDH (both operatively and conservatively managed) (P) does the use of standardised tools to assess ongoing rehabilitation requirements (I) improve patient, system, and clinical outcomes (O) compared to standard care? | |

| 32 | In patients who have had interventional treatment for cSDH (P) does protocolised post-operative care and standardised discharge criteria (I) improve patient, system (e.g. time to discharge, DToC rates), and clinical outcomes (O) compared to standard care? | |

| 34 | In patients who have had surgery for cSDH (P) does the provision of standardised ‘red-flag’ checklists (I) improve time-to-diagnosis of symptomatic recurrence(O) compared to standard care (C) | |

| 4 | In patients with a CSDH (both operative and non-operative) is their outcome (both patient and clinical) (O) improved if they receive ongoing care (e.g. rehabilitation, medical management) in a specialist (I) (neurosciences or rehabilitation facility) compared to non-specialist (secondary care) setting? | |

| Natural history | 29 | What factors (I) are most associated with an increased risk for developing cSDH (O) among older adults in the community (P) compared with older adults without these factors (C)? |

| 35 | In patients with a CSDH triaged for non-operative management (P), does active surveillance (e.g. interval CT imaging) (I) compared to expectant management (C) improve patient, system, and clinical outcomes (O) | |

| Surgical technique | 38 | In patients who undergo surgical treatment for cSDH (P) does craniotomy (I) improve patient, system (e.g. time to discharge, DToC rates), and clinical outcomes (O) compared to burr holes? |

| 40 | In patients who undergo surgical treatment for cSDH (P) does (Drain Variation X) (I) improve patient, system (e.g. time to discharge, DToC rates), and clinical outcomes (O) compared to subdural catheter on free drainage? | |

| 41 | In patients undergoing a procedural intervention for chronic subdural haematoma (P) does provision of surgical/procedural/anaesthetic care by a ‘senior’ (I) (i.e. consultant level) provider vs ‘junior’ (i.e. non-consultant level) (C) affect patient, system, and provider outcomes (O) | |

| MMA embolisation | 42 | In patients with an incidental cSDH (P) does MMA (I) improve patient, system (e.g. time to discharge, DToC rates), and clinical outcomes (O) compared to surveillance and risk factor modification alone? |

| 43 | In patients with a symptomatic cSDH (P) does MMA (I) improve patient, system (e.g. time to discharge, DToC rates), and clinical outcomes (O) compared to surgical evacuation? | |

| 44 | In patients with a symptomatic cSDH (P) does MMA in addition to surgery (I) improve patient, system (e.g. time to discharge, DToC rates), and clinical outcomes (in particular recurrence) (O) compared to surgical evacuation? |

Umbrella review

Seventy-three articles (Supplementary Table 3) reporting on 1914 studies and 206,379 patients were included (Supplementary Figure 2). A list of full-text articles screened, but excluded from the review, is included in Supplementary Table 4.

Study characteristics are outlined in Table 2. Almost all papers (98.6%, n=72/73) were published between 2010 and 2022. Most articles were from China (32.9%, n=24), followed by USA (20.5%, n=15), UK (8.2%, n=6), Netherlands (8.2%, n=6) and Canada (8.2%, n=6). The most common publishing journals were World Neurosurgery (21.9%, n=16), Acta Neurochirurgica (9.6%, n=7) and Frontiers in Neurology (6.8%, n=5). The median number of studies included per review was 13 (IQR 7–21), and the median number of participants was 1119 (IQR 441–3149). 76.7% (n=56) explicitly referenced following PRISMA guidelines. The most common review typology was effectiveness (71.2%, n=52). The overall mean adherence to PRISMA guidelines was 58.5% (SD 16.9).

Table 2.

Study characteristics

| Baseline characteristics | Value (%) [SD] (IQR) |

|---|---|

| Total studies included | 73 |

| Review types | Frequency |

| Systematic review and meta-analysis | 50 (68.5) |

| Systematic review | 22 (30.1) |

| Umbrella review | 1 (1.4) |

| Continent of authors | Frequency |

| Asia | 29 (39.7) |

| North America | 21 (28.8) |

| Europe | 19 (25.8) |

| Other | 4 (5.7) |

| Journal | Frequency |

| World Neurosurgery | 16 (21.9) |

| Acta Neurochirurgica | 7 (9.6) |

| Frontiers in Neurology | 5 (6.8) |

| Neurosurgical Review | 3 (4.1) |

| Journal of Neurotrauma | 3 (4.1) |

| Medicine (Baltimore) | 3 (2.7) |

| Journal of Neurosurgery | 2 (2.7) |

| Journal of Clinical Neurosciences | 2 (2.7) |

| Journal of Neurointerventional Surgery | 2 (2.7) |

| British Journal of Neurosurgery | 2 (2.7) |

| Other | 28 (38.4) |

| Study details | Frequency |

| Number of included studies | 13 (7–21) |

| Number of included participants | 1119 [441–3149] |

| Total number of included participants | 206,379 |

| Review typology | Frequency |

| Effectiveness | 52 (71.2) |

| Prevalence and/or incidence | 3 (4.1) |

| Methodological | 3 (4.1) |

| Other | 15 (20.6) |

| Mentioned reporting according to PRISMA | Frequency |

| Yes | 56 (76.7) |

| No | 17 (23.3) |

SD standard deviation, IQR inter-quartile range

Content and domain reporting

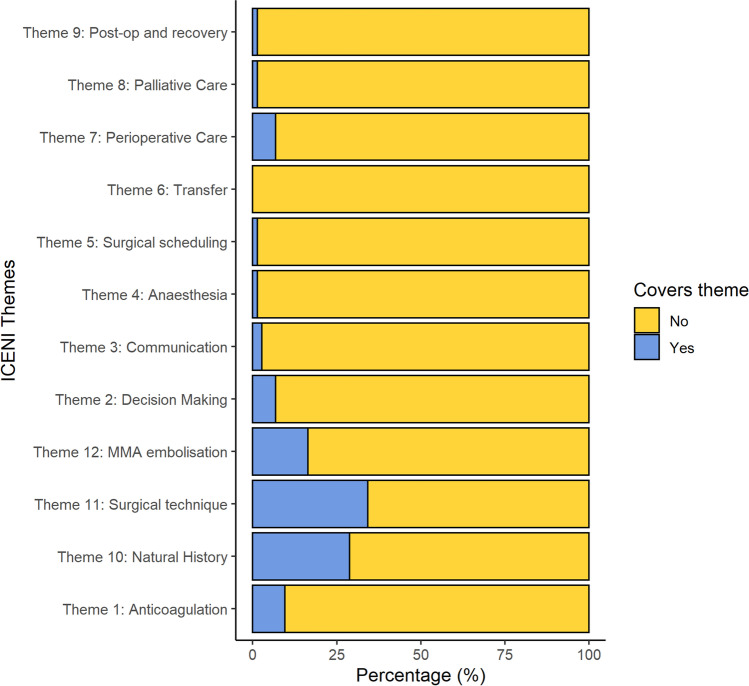

The number of reviews examining each ICENI theme is shown in Table 3, and Fig. 2. The three most common themes addressed were surgical technique (34.2%, n=25), natural history (28.8%, n=21) and MMA embolisation (16.4%, n=12). Content was additionally categorised according CSDH themes identified through thematic analysis of CSDH education resources. These are shown in Supplementary Table 5. In total, 86.3% (n=63) of reviews assessed complications and recurrence, 65.8% (n=48) survival and performance outcomes, 50.7% (n=37) non-surgical management and 43.8% (n=32) surgical management. No reviews assessed quality of life.

Table 3.

ICENI themes, number of research questions and number of reviews for each category

| Theme | Number of research questions (N) | Reviews identified (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Anticoagulant | 6 | 7 (9.6) |

| Decision-making | 6 | 5 (6.8) |

| Communication | 2 | 2 (2.7) |

| Anaesthesia and surgical scheduling | 7 | 1 (1.4) |

| Transfer | 7 | 0 (0.0) |

| Perioperative care | 3 | 5 (6.8) |

| Palliative care | 3 | 0 (0.0) |

| Postop and recovery | 5 | 1 (1.4) |

| Natural history | 2 | 21 (28.8) |

| Surgical technique | 3 | 25 (34.2) |

| MMA embolisation | 3 | 12 (16.4) |

Fig. 2.

Bar chart of ICENI themes included in existing CSDH reviews

In total, 55 studies were identified as work similar to that of previously published reviews (Supplementary Table 6). The number of ‘duplicate’ manuscripts was 54.8% (n=40). The most duplicated (‘similar’ or ‘very-similar’) reviews related to MMA embolisation (n=9), corticosteroid use (n=7) and drain use (n=6).

AMSTAR-2 reporting quality

The quality scores for each component are shown in Table 4. The highest reported field was item 8 (‘including details of studies’ (94.5%, n=69/73)) and item 10 (‘declaring review author funding’ (90.4%, n=66)). The lowest reported fields were item 10 (‘assessing funding of included papers in review’ (27.4%, n=20)), and item 2, (‘referring to a study protocol’ (32.9%, n=24)). Overall, 7 reviews (9.6%) were classified as having high confidence in the results of the review. A further 8 studies (11.0%) were classified as having moderate confidence in results, 10 (13.7%) as low confidence and 48 (65.7%) critically low confidence.

Table 4.

AMSTAR-2 reporting of CSDH reviews

| Item number | Description | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | PICO description | 62 (84.9) |

| 2 | Review methods and protocol deviations | 24 (32.9) |

| 3 | Explain study designs for inclusion | 56 (76.7) |

| 4 | Comprehensive search strategy | 38 (52.1) |

| 5 | Duplicate study selection | 55 (75.3) |

| 6 | Duplicate data extraction | 55 (75.3) |

| 7 | List of excluded studies with justification | 29 (39.7) |

| 8 | Description of included studies | 69 (94.5) |

| 9 | Risk of bias for included studies | 45 (61.6) |

| 10 | Funding sources for included studies | 20 (27.4) |

| 11 | Meta-analysis statistics | 24 (32.9) |

| 12 | Meta-analysis risk of bias | 21 (42.9) |

| 13 | Risk of bias in discussion | 44 (60.3) |

| 14 | Explanation of heterogeneity | 48 (65.8) |

| 15 | Publication bias | 29 (59.2) |

| 16 | Conflict of interest reporting | 66 (90.4) |

| Confidence rating | ||

| 1 | High | 7 (9.6) |

| 2 | Moderate | 8 (11.0) |

| 3 | Low | 10 (13.7) |

| 4 | Critically low | 48 (65.8) |

*Number lower as only applies to systematic reviews with meta-analysis

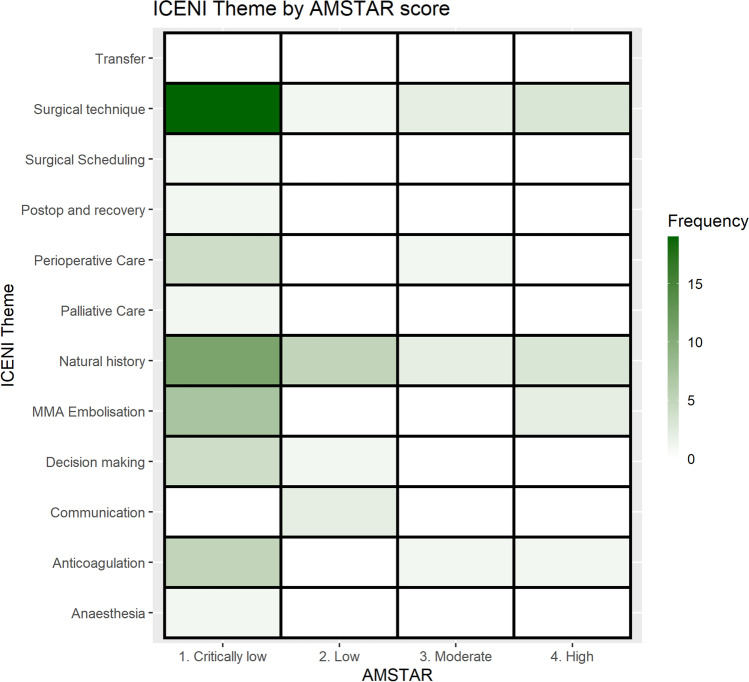

Gap analysis of ICENI themes matched to AMSTAR-2 score

The gap analysis of the 12 ICENI themes, mapped to AMSTAR-2 score, is shown in Fig. 3. In total, there was one high confidence review on anticoagulation, three on natural history, two on surgical technique and one on MMA embolisation. There was one moderate confidence review on perioperative care, two on natural history, two on surgical technique and two on MMA embolisation. All other reviews scored either low or critically low in confidence level when addressing ICENI themes. The reviews with high AMSTAR ratings are shown below in Online Supplementary Table 7.

Fig. 3.

Heatmap gap analysis of ICENI themes, stratified by AMSTAR-2 confidence rating (white indicates zero reviews available

Discussion

Summary of findings

This umbrella review and gap analysis identified that available systematic reviews on CSDH have critically low confidence in quality assessment. The CSDH evidence base focusses almost exclusively on procedural interventions, and binary outcomes (such as recurrence and mortality). Only 7 reviews targeted, with sufficient quality, questions posed for the proposed ICENI CSDH guidelines—indicating many areas relevant to CSDH management that are not addressed by current systematic reviews.

However, even within this narrow focus of procedural interventions, there exists a duplication of effort, and very often reviews were poorly placed to inform care; for example, almost two-thirds of reviews were categorised as having critically low confidence in their results according to AMSTAR-2. It is important to note that each component of AMSTAR-2 is not considered by all to have equal weighting or significance, for example factors such as protocol registration and the funding of included studies, which were the most poorly reported domains [12, 25]. Further, a risk of bias assessment was not formally completed. However, corroborating this finding, PRISMA compliance was also low.

Systematic reviews are important and influential—they inform future research, and are often required by research funders for trial applications [5, 11, 26]. Consequently, albeit a surrogate, the focus and activity within an umbrella review is an indication of the broader research environment. That CSDH is therefore focused on procedural interventions and their consequences is unsurprising. At present, despite a variety of other stakeholders that may be involved [29], the common focal point for anyone diagnosed with a CSDH is a consultation with Neurosurgery to determine whether treatment is required. The majority of CSDH research is undertaken by neurosurgical teams, and this therefore reflects their principal requirements [9]. Thus, whilst the evidence base around surgical management has improved and is ready to inform care, broader challenges remain. This reinforces the importance of the ICENI initiative, and specifically the role of multi stakeholder engagement to identify unsolved yet important challenges in the clinical pathway [4, 8, 9, 27].

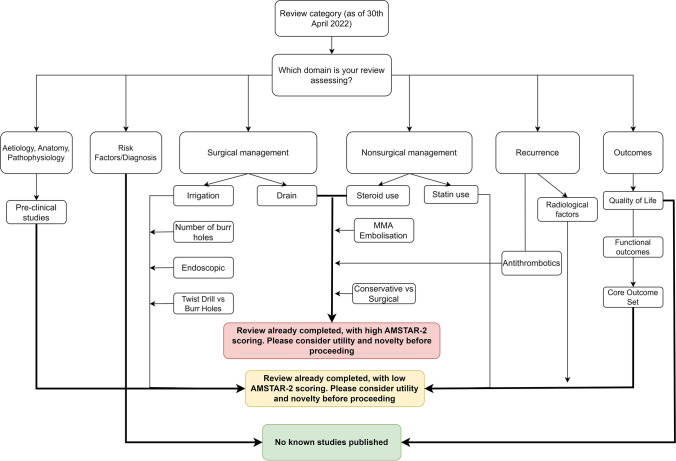

This study therefore has simple but important implications for improving care in CSDH. Firstly, the information gathered by this manuscript and literature gaps identified can be used to guide future reviews [9]. In particular, peri-operative anaesthesia [16] and quality of life appear areas of unmet need. Second, we have produced a decision flow-chart (Fig. 4) that can be used to guide the process of selection of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, to avoid review saturation as a consequence of duplication of work produced in the CSDH field in the last 5 years. Further, it reinforces the importance of aiming for quality when conducting reviews, to ensure their conduct can inform care, for example through uptake in clinical practice guidelines. Broader strategies including PROSPERO registration, and PRISMA Reporting Guidelines have been important interventions, and adherence is key to ensuring optimal reviews are performed. Finally, it reinforces the need to capture a multi-stakeholder perspective when seeking to solve a clinical problem. Research shows that professionals gravitate towards procedural research, in contrast to priorities set by organisations such as the James Lind Alliance [7, 15].

Fig. 4.

Decision aid to guide future systematic reviews on Chronic Subdural Haematoma

Conclusion

Systematic reviews and meta-analysis on management of CSDH focus on procedural interventions, such as surgery or MMA embolisation. Further, they are poorly compliant with recommended reporting checklists and are often of low quality. Many themes identified as critical to inform clinical care by multidisciplinary groups remain to be explored in CSDH. New evidence synthesis that adheres to available checklists, and addresses these gaps, is therefore required to strengthen the current limited evidence base, avoid bias and enhance CSDH care.

Supplementary information

(DOCX 827 kb)

(DOCX 48 kb)

Acknowledgements

ICENI collaborative: Thomas H Bashford, Ellie Edlmann, Andrew Bateman, Phillip Braude, Rowan Burnstein, Sophie Camp, Georgina Carr, PJ Clarkson, Jonathan Coles, Jugdeep Dhesi, Judith Dinsmore, Mary Dixon-Woods, Ari Ercole, Nicholas Evans, Anthony Figaji, Simon Griffin, Paul Grundy, Peter Hartley, Alexis Joannides, Angelos Kolias, Fiona Lecky, Paul May, Iain Moppett, Stephen Morris, Mike Nathanson, Joanne Outtrim, Nicola Owen, Nick Phillips, Terence Quinn, Shvaita Ralhan, David Sapsford, David JH Shipway, Charlotte Skitterall, Magdalena Smith, Michael Swart, Will Thomas, Krystyna Walton, Nicholas Wareham, Peter Whitfield, Sally R Wilson, Madhavi Vindlacheruvu.

Author contributions

CSG: conception, writing, data collection, reviewing, and editing. EKF: writing, data collection, reviewing, and editing. AMA: writing, data collection, reviewing, and editing. AYT: data collection, data analysis, reviewing, and editing. JD: writing, reviewing and editing, supervision. EE: writing, reviewing and editing, supervision. JC: conception, reviewing and editing, supervision, advice. DKM: writing, reviewing and editing, supervision. PJH: reviewing and editing, supervision. DJS: conception, critical reviewing, editing, supervision, advice; guarantor. BMD: conception, critical reviewing, editing, supervision, advice; guarantor

Funding

The ICENI initiative is supported by funding from the National Institute of Academic Anaesthesia (Association of Anaesthetists/Anaesthesia grant) (reference WKR0-2021-0014) with early work funded by the Addenbrooke’s Charitable Trust (reference 900268). Workshops to identify research questions were funded by the Addenbrookes charitable trust. This research was supported by the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC-1215-20014). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Adhiyaman V, Chattopadhyay I, Irshad F, Curran D, Abraham S. Increasing incidence of chronic subdural haematoma in the elderly. QJM: Int J Med. 2017;110:375–378. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcw231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balser D, Farooq S, Mehmood T, Reyes M, Samadani U. Actual and projected incidence rates for chronic subdural hematomas in United States Veterans Administration and civilian populations. J Neurosurg. 2015;123:1209–1215. doi: 10.3171/2014.9.Jns141550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brennan PM, Kolias AG, Joannides AJ, Shapey J, Marcus HJ, Gregson BA, Grover PJ, Hutchinson PJ, Coulter IC. The management and outcome for patients with chronic subdural hematoma: a prospective, multicenter, observational cohort study in the United Kingdom. J Neurosurg. 2017;127(4):732–739. doi: 10.3171/2016.8.JNS16134.test. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, Garattini S, Grant J, Gülmezoglu AM, Howells DW, Ioannidis JPA, Oliver S. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. The Lancet. 2014;383:156–165. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. The Lancet. 2009;374:86–89. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60329-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Barbui C. What is a Cochrane review? Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2011;20:231–233. doi: 10.1017/s2045796011000436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowe S, Fenton M, Hall M, Cowan K, Chalmers I. Patients’, clinicians’ and the research communities’ priorities for treatment research: there is an important mismatch. Res Involv Engagem. 2015;1:2. doi: 10.1186/s40900-015-0003-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies BM, Kwon BK, Fehlings MG, Kotter MRN. AO Spine RECODE-DCM: why prioritize research in degenerative cervical myelopathy? Global Spine J. 2022;12:5S–7S. doi: 10.1177/21925682211035379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edlmann E, Holl DC, Lingsma HF, Bartek J, Jr, Bartley A, Duerinck J, Jensen TSR, Soleman J, Shanbhag NC, Devi BI, Laeke T, Rubiano AM, Fugleholm K, van der Veken J, Tisell M, Hutchinson PJ, Dammers R, Kolias AG. Systematic review of current randomised control trials in chronic subdural haematoma and proposal for an international collaborative approach. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2020;162:763–776. doi: 10.1007/s00701-020-04218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fusar-Poli P, Radua J. Ten simple rules for conducting umbrella reviews. Evid Based Ment Health. 2018;21:95. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2018-300014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glasziou P, Chalmers I (2015) How systematic reviews can reduce waste in research. thebmjopinion. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2015/10/29/how-systematic-reviews-can-reduce-waste-in-research/. Accessed 21 Sept 2022

- 12.Grodzinski B, Mowforth O, Tetreault LA, Davies BM. Improving the quality of systematic reviews in spinal surgery requires community-wide engagement and pragmatism. Global Spine J. 2020;10:1078–1079. doi: 10.1177/2192568220952758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hutchinson PJ, Edlmann E, Bulters D, Zolnourian A, Holton P, Suttner N, Agyemang K, Thomson S, Anderson IA, Al-Tamimi YZ, Henderson D, Whitfield PC, Gherle M, Brennan PM, Allison A, Thelin EP, Tarantino S, Pantaleo B, Caldwell K, Davis-Wilkie C, Mee H, Warburton EA, Barton G, Chari A, Marcus HJ, King AT, Belli A, Myint PK, Wilkinson I, Santarius T, Turner C, Bond S, Kolias AG. Trial of dexamethasone for chronic subdural hematoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2616–2627. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2020473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolias AG, Chari A, Santarius T, Hutchinson PJ. Chronic subdural haematoma: modern management and emerging therapies. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:570–578. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lind Alliance J (2021) A project to map and analyse outputs from JLA PSPs. https://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/news/a-project-to-map-and-analyse-outputs-from-jla-psps/28765. Accessed 30/09/2022 2022

- 16.Liu HY, Yang LL, Dai XY, Li ZP. Local anesthesia with sedation and general anesthesia for the treatment of chronic subdural hematoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26:1625–1631. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202203_28230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mebberson K, Colditz M, Marshman LAG, Thomas PAW, Mitchell PS, Robertson K. Prospective randomized placebo-controlled double-blind clinical study of adjuvant dexamethasone with surgery for chronic subdural haematoma with post-operative subdural drainage: Interim analysis. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;71:153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2019.08.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miranda LB, Braxton E, Hobbs J, Quigley MR. Chronic subdural hematoma in the elderly: not a benign disease. J Neurosurg. 2011;114:72–76. doi: 10.3171/2010.8.Jns10298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munn Z, Stern C, Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Jordan Z. What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:5. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0468-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neifert SN, Chaman EK, Hardigan T, Ladner TR, Feng R, Caridi JM, Kellner CP, Oermann EK. Increases in subdural hematoma with an aging population-the future of American cerebrovascular disease. World Neurosurg. 2020;141:e166–e174. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ng S, Boetto J, Huguet H, Roche P-H, Fuentes S, Lonjon M, Litrico S, Barbanel A-M, Sabatier P, Bauchet L, Chevassus H, Lonjon N, Aloy E, Boniface G, Chan-Seng E, Cochereau J, Dufour H, Farah K, Fontaine D, Graillon T, Gras-Combe G, Gros V, Haynes W, Khouri K, Le Corre M, Maillard A, Paquis P, Poulen G, Quintard A, Rodriguez M-A, Rolland A, Ros M, Segnarbieux F, Suleiman N, Troude L, Vassal M, Verissimo A-S. Corticosteroids as an adjuvant treatment to surgery in chronic subdural hematomas: a multi-center double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Neurotrauma. 2021;38:1484–1494. doi: 10.1089/neu.2020.7560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rauhala M, Helén P, Seppä K, Huhtala H, Iverson GL, Niskakangas T, Öhman J, Luoto TM. Long-term excess mortality after chronic subdural hematoma. Acta Neurochirurgica. 2020;162:1467–1478. doi: 10.1007/s00701-020-04278-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santarius T, Kirkpatrick PJ, Ganesan D, Chia HL, Jalloh I, Smielewski P, Richards HK, Marcus H, Parker RA, Price SJ, Kirollos RW, Pickard JD, Hutchinson PJ. Use of drains versus no drains after burr-hole evacuation of chronic subdural haematoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1067–1073. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(09)61115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, Moher D, Tugwell P, Welch V, Kristjansson E, Henry DA. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Straus SE, Holroyd-Leduc J. Knowledge-to-action cycle. Evid Based Med. 2008;13:98. doi: 10.1136/ebm.13.4.98-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stubbs DJ, Davies B, Hutchinson P, Menon DK. Challenges and opportunities in the care of chronic subdural haematoma: perspectives from a multi-disciplinary working group on the need for change. Br J Neurosurg. 2022;36(5):600–608. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2021.2024508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stubbs DJ, Davies BM, Bashford T, Joannides AJ, Hutchinson PJ, Menon DK, Ercole A, Burnstein RM. Identification of factors associated with morbidity and postoperative length of stay in surgically managed chronic subdural haematoma using electronic health records: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e037385. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stubbs DJ, Davies BM, Menon DK. Chronic subdural haematoma: the role of peri-operative medicine in a common form of reversible brain injury. Anaesthesia. 2022;77:21–33. doi: 10.1111/anae.15583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stubbs DJ, Vivian ME, Davies BM, Ercole A, Burnstein R, Joannides AJ. Incidence of chronic subdural haematoma: a single-centre exploration of the effects of an ageing population with a review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2021;163:2629–2637. doi: 10.1007/s00701-021-04879-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. Bmj. 1999;318:527–530. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7182.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 827 kb)

(DOCX 48 kb)