Abstract

The mother represents one of the earliest sources of microorganisms to the child, influencing the acquisition and establishment of its microbiota in early life. However, the impact of the mother on the oral microbiota of the child from early life until adulthood remains to unveil. This narrative review aims to: i) explore the maternal influence on the oral microbiota of the child, ii) summarize the similarity between the oral microbiota of mother and child over time, iii) understand possible routes for vertical transmission, and iv) comprehend the clinical significance of this process for the child. We first describe the acquisition of the oral microbiota of the child and maternal factors related to this process. We compare the similarity between the oral microbiota of mother and child throughout time, while presenting possible routes for vertical transmission. Finally, we discuss the clinical relevance of the mother in the pathophysiological outcome of the child. Overall, maternal and non-maternal factors impact the oral microbiota of the child through several mechanisms, although the consequences in the long term are still unclear. More longitudinal research is needed to unveil the importance of early-life microbiota on the future health of the infant.

Keywords: Oral microbiota, Infancy, Mother, Dysbiosis, Vertical transmission, Oral health

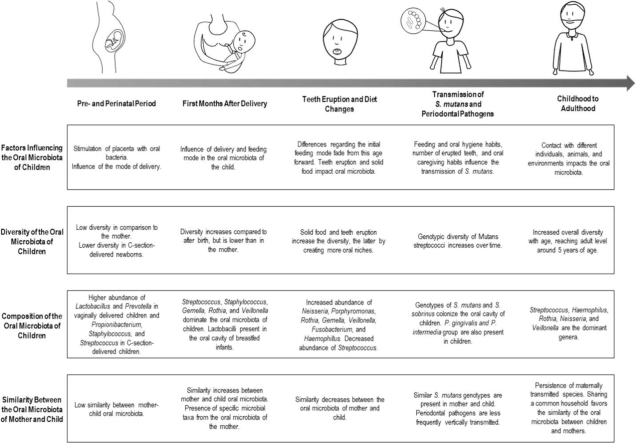

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

In the last decade, with the onset of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Human Microbiome Project, there has been a growing panoply of culture-independent studies focusing on the characterization of the human microbiome in health and disease [1]. The finding that hundreds of microbial species inhabit the human body and regulate the human metabolism, physiology, and immunity, therefore interfering in human development has revolutionized how medicine perceives the host-microbiota relationship [2], [3]. The microbiota comprises the totality of bacteria, archaea, viruses, and microeukaryotes that inhabit a certain ecological niche [4], [5]. The “omics” advent allowed not only to characterize human microbiota, but also to begin to unveil its mechanisms of action and its influence on the host physiology [6]. The human microbiota is responsible for a multitude of physiological functions, including fiber degradation, vitamin and amino acid biosynthesis, host immune-system modulation, the regulation of pH, among others [3], [7]. Each niche-specific microbiota also has evolved to resist foreign colonization, either through direct competition for nutrients, by releasing antimicrobial compounds (such as bacteriocins and reactive oxygen species), or by modulating microenvironmental conditions [8]. Concurrently, the human microbiota has a preponderant role in the normal training and functioning of the immune system, such as through the production of microbial metabolites (e.g., short-chain fatty acids), co-metabolites (e.g., polyamines and aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands), or on the control of proliferation and differentiation of T and B cells [3], [9].

The oral microbiota comprises microorganisms inhabiting the oral cavity [10], [11]. This ecosystem is subdivided into distinct soft and hard tissue niches, namely oral mucosa, lips, palate, tongue, and teeth [12]. Additionally, saliva harbors microorganisms from these niches and represents a reservoir and potential fingerprint of the oral microbiota [13]. Saliva, as it is an accessible oral sample, is often collected in clinical studies and differences in its microbial composition are suggested as a potential biomarker to monitor oral and systemic diseases [14]. According to numerous studies based on culture-independent molecular analysis, the healthy adult oral microbiota appears to be dominated by the phyla Bacillota (previously Firmicutes), Actinomycetota (previously Actinobacteria), Pseudomonadota (previously Proteobacteria), Fusobacteriota (previously Fusobacteria), Bacteroidota (previously Bacteroidetes), and Spirochaetota (previously Spirochaetae) [4], [15]. The oral microbiota represents the second most complex and studied microbial community in the human body and, in homeostasis, it coexists and contributes symbiotically with the overall physiology of the host [3], [16], [17], [18]. The oral microbiota plays an important role in human health and the identification of pioneer colonizers and factors influencing acquisition of these microorganisms is essential to elucidate the development of a eubiotic, i.e. an optimally balanced microbiota, or dysbiotic microbial community throughout life [19].

The composition of the human oral microbiota changes considerably throughout life, but particularly during childhood [20]. From an early stage in life, the human oral cavity comes in contact with a wide variety of microorganisms, and the set of initial colonizers conditions the subsequent colonization [21], [22], [23]. These early microbial communities have, therefore, a major role in the development of the microbiota of the adult-body and may represent a source of pathogenic and protective microorganisms in a very early-stage of human life. Regarding the trigger for oral colonization, there is still controversy on whether there is in utero microbial seeding of the infant, but it seems that delivery mode highly impacts the oral colonization [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]. Thereafter, the development and maturation of the human microbiota are shaped by microbial and host interaction and by numerous intrinsic and extrinsic elements, such as host genetics, maternal and environmental factors [29], [30], [31]. Studies on gut microbiota suggest that maternally acquired strains are more persistent and are better adapted, and this seems to gain particular relevance when mothers have dysbiosis of the gut [32], [33]. However, this has not yet been clarified for the oral microbiota.

Despite the importance of the mother as a source of microorganisms for the child, the extent of this vertical transmission and its impact on the oral microbiota and health of the child remains to be clarified [30]. Therefore, this narrative review aimed to i) explore the maternal influence on the oral microbiota of the child, ii) provide an overview of the similarity between the oral microbiota of mother and child throughout time, iii) understand the possible routes for vertical transmission, and iv) comprehend the clinical significance of oral microbiota transmission for the health of the child.

2. Pre- and perinatal factors

The exact timing for oral microbial colonization is still under much debate. Some studies in humans and murine models show that the oral microorganisms of pregnant individuals can spread via blood stream to the placenta and this seems to be associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preeclampsia or preterm labor [24], [25]. Conversely, some authors consider that the placenta has no microbiota, but it can be colonized by pathogens such as Streptococcus agalactiae [27]. However, recent scientific evidence suggests the presence of an intrauterine microbiota in full-term gestations without complications or infectious episodes [24], [34], [35], [36] and the colonization of the placenta, umbilical cord blood, and amniotic fluid by oral microorganisms, such as species from the phyla Bacillota, Pseudomonadota, and Fusobacteriota in full-term healthy pregnancies has been reported [34], [37]. Interestingly, the intrauterine microbiota was shown to be more similar to the maternal oral microbiota than to the intestinal, vaginal or skin microbiota [24], [38]. The hormonal changes, which impact the subgingival microbiota and immune physiology and inflammatory state of periodontal tissues, were proposed as a key factor for the relationship between oral and intrauterine microbiota [38], [39], [40]. It was also suggested that, during pregnancy, the placenta becomes an antigen-collecting site in order to stimulate the foetal immune system and enhance the newborn immunological tolerance to the maternal microbiota, thus allowing successful postnatal colonization with maternal microorganisms [39]. This leads us to infer that the stimulation with a dysbiotic microbiota might impair the development of the immune system since early life and condition the postnatal microbial colonization. Still, if and to what extent early tolerance of the foetus toward the maternal oral species is a key factor to the colonization of the newborn and healthy development of the gastrointestinal tract in the earliest phases of life is yet to be uncovered [41].

Despite this possibility, the most agreed on hypothesis is that the oral microbiota acquisition starts during birth, when the amniotic membranes rupture [41]. The process of colonization of the oral surfaces starts with the establishment of pioneer microorganisms organized in biofilms, which through antagonistic and/or cooperative interactions, promote or inhibit the growth of other species by the production of metabolic products and quorum sensing [42]. After delivery, the usual pioneer microorganisms are facultative aerobic microorganisms, mainly belonging to the Streptococcus and Staphylococcus genera [43].

Although immediately after birth the oral microbiota of the child does not seem to resemble the microbiota of the mother, it is well described that the early oral microbial profile is associated with the delivery mode (Table 1) [44], [45]. Dominguez-Bello et al. (2010) [46] performed a peri-natal cross-sectional study with 10 Venezuelan mother-child pairs, born vaginally and by C-section, and characterized the microbiota of different body sites. They observed that, during the first minutes of life, bacterial communities are undifferentiated across the body and that the oral microbiota of the mother does not seem to contribute significantly towards the oral microbiota of the newborn. The taxa detected in the microbiota of the infant reflected the mode of delivery and Lactobacillus, Atopobium and Sneathia spp. were abundant in vaginally delivered neonates, while Staphylococcus spp. and Propionibacterium spp. were detected in C-section delivered neonates. Nevertheless, transmission was suggested between the vaginal microbiota of the mothers and the microbiota of their vaginally delivered newborns, since the maternal vaginal community was significantly more similar to microbiota of her own infant than to the microbiota of other vaginally delivered infants. Likewise, Li et al. (2018) [47] also reported differences in the oral microbiota of the newborns according to the type of delivery, with a higher abundance of genus commensal from the vaginal microbiota (Lactobacillus, Prevotella, and Gardnerella) in the vaginal delivery group. [47]. In addition, Hurley et al. (2019) [48] reported that alpha diversity of the oral microbiota, i.e. the range of different species inhabiting a niche and measured by indices such as richness and Shannon, of 1-week-old infants was significantly affected by birth mode. However, this effect was not observed after the first week of life. Some studies found that children delivered by C-section were colonized by mutans streptococci and had a higher risk of early childhood caries (ECC) almost a year earlier than the vaginally delivered newborns [22], [49]. Despite this, the extent of the impact of this early life event on the oral microbiota is still under debate [48].

Table 1.

Children oral microbiota characterization by type of delivery.

| Author (year) |

Type of study & Number of participants |

Type of Samples | Moment of sampling |

DNA sequencing technique & Taxonomic Database |

Vaginal Delivery | C-section Delivery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dominguez-Bello et al. (2010)[126] | Cross-sectional case-control study 10 mother-child pairs |

Skin (Mo/Ch); Oral mucosa (Mo/Ch); Vagina (Mo); Nasopharyngeal aspirate (Ch); Meconium (Ch). |

1 h before delivery (Mo); < 5 min (Ch); Meconium < 24 h (Ch). |

Sequencing of the 16 S rRNA (V2) Ribossomal Database Project |

Vaginally delivered infants acquired bacterial communities resembling their own mother's vaginal microbiota, dominated by Lactobacillus, Prevotella, or Sneathia spp. | C-section infants harbored bacterial communities similar to those found on the skin surface, dominated by Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, and Propionibacterium spp. |

| Hurley et al. (2019)[48] | Longitudinal study 84 mother-child pairs |

Saliva (Mo/Ch) and vaginal/skin sample (Mo). | At delivery (Mo); 1, 4 and 8 weeks after birth, 6 months and 1 year of age (Ch). | Sequencing of the 16 S rRNA (V4-V5) CORE database |

After 1 week, vaginally delivered infants have more Porphyromonas and Prevotella than C-section-born infants. Identification of L. iners and P. acnes of maternal vagina and skin in the oral microbiota of vaginally-delivered infants 1 week after delivery. | Children born by C-section have a higher abundance of Streptococcus and Gemella. These children also present a higher Shannon diversity one week after delivery, but not afterwards. |

| Li et al. (2018)[47] | Cross-sectional 18 C-section delivered infants and 74 vaginally delivered children |

Oral bucal swab | Immediately after delivery | Sequencing of the 16 S rRNA (V3-V4) Ribossomal Database Project |

Significantly more Actinobacteria, Firmicutes and less Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria, in the vaginal delivery group. Higher abundance of Lactobacillus, Prevotella, Bifidobacterium, and Faecalibacterium. | Higher abundance of and Petrimonas, Desulfovibrio, and Pseudomonas. Vaginal delivery cases that clustered with the C-section group had longer time in the delivery process (Unweighted unifrac clustering). |

| Gomez-Arango et al. (2017)[50] | Cross-sectional 36 mother-child pairs |

Oral buccal swabs, stool samples (Mo), and placenta (Mo) | 16 weeks gestation: stool sample 36 weeks gestation: oral buccal swab (Mo) After delivery: placenta (Mo) 3 days after delivery: oral buccal swab (Ch) |

Sequencing of the 16 S rRNA (V6-V8) Greengenes |

The clustering of the neonatal oral microbiota was based on the maternal exposure to antibiotics at delivery, regardless of the delivery mode. Families from Pseudomonadota were more abundant in infants born from mothers who took intrapartum antibiotics. | --- |

| Chu, D.M. et al. (2017)[127] | Longitudinal cohort study 81 healthy mother-child pairs |

Antecubital fossa (Mo/Ch); Retro-auricular crease (Mo/Ch); Keratinized gingiva (Mo/Ch); Anterior nares (Mo/Ch); Stool (Mo/Ch); Introitus (Mo); Posterior fornix (Mo). |

At delivery; 4–6 weeks postpartum. |

Whole-genome shotgun sequencing; Sequencing of the 16 S rRNA (V5-V3). GreenGenes |

At birth, delivery mode influenced the patterns of oral microbial composition. Increased abundance of Lactobacillus. Oral microbiome was more similar to the vaginal microbiota of their mothers. Differences were not verified 6 weeks after delivery. |

Reduced alfa diversity at birth. Increased abundance of Propionibacterium and Streptococcus in infants born by C-section. |

Mo – Mother. Ch – Child. Min – minutes. H – Hours.

However, it is important to highlight that, in these studies, mothers who delivered through C-section had taken antibiotics prior to the surgery, which did not necessarily occur in women who delivered vaginally and may have also influenced the results [50]. In fact, literature seems to evidence that intrapartum antibiotic intake, either before C-section or for Group B Streptococcus prophylaxis, alters the vaginal microbiota prior to birth and influences the development of the microbiota in neonates and reduces intestinal host defenses [50], [51]. Li et al. (2019) [52] observed that there were ecological changes in the oral microbiota of children whose mothers were exposed to intrapartum antibiotics: an increased abundance of genera Klebsiella, Roseburia, Propionibacterium, Faecalibacterium, Escherichia/Shigella, Corynebacterium, Bifidobacterium, and Bacteroides, some of which are opportunistic pathogens. In these infants, the functional pathway analysis revealed an increased lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis, as endotoxin which plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of certain infections. Gomez-Arango et al. (2017) [50] observed that babies born from mother who had taken antibiotics had an enrichment in families belonging to Proteobacteria, whereas the families Streptococcaceae, Gemellaceae and Lactobacillales were dominant in unexposed neonates. Furthermore, the neonatal oral microbiota clustered based on maternal exposure to intrapartum antibiotics, but not with respect to mode of delivery [50].

Additionally, the exposure to postpartum environment may play a role in early colonization. For instance, a study by Shin et al. (2015) [53] verified that the operating room microbiota (e.g. lamps, ventilation grids, among others) was dominated by Staphylococcus and Corynebacterium, bacteria usually found on human skin, possibly serving as a source of bacteria after delivery. Moreover, a recent study by Shao et al. (2019) [54] verified the gut colonization by opportunistic pathogens associated with the hospital environment, such as Enterococcus, Enterobacter, and Klebsiella species, particularly in infants delivered by C-section.

Regarding the influence of the oral microbiota of the mother during this period, Ferretti et al. (2018) [33] studied longitudinally a cohort of 25 healthy Italian mother-child pairs, all born vaginally, by collecting several samples from the pairs such as oral swabs collected at delivery, 1 day and 3 days after birth. Through strain-level metagenomics profiling, they assessed the impact of the maternal microbiota on the development of the oral and fecal microbial communities of the child. The tongue microbiota of the infants had high inter-subject variability, especially in early points of life (at delivery, 1 day after delivery), and their microbiota did not resemble the respective maternal body site. This inter-subject diversity and lack of uniformity after a day of life may be due to the fact that infant seeding is influenced by different maternal microbiota, either in utero or through contact after delivery. In the oral cavity, the relative abundance of shared species between the mother-child pair raised from 77.6% in day 1–95.4% in day 3 in child’s oral swabs, with the most shared species being Rothia mucilaginosa and Streptococcus mitis/oralis, among others. However, the shared species were present at low relative abundance in the tongue of the mother (5.7% at day 1; 6.6% at day 3) compared to the child. At the third day of life, the oral microbiota of the infants shared more similar species with their mother than with other mothers. On day 3, the oral cavity of the child is predominantly populated by species more associated with oral communities. Regarding vertical transmission, the researchers detected a total of 52 strains shared between mother and child (16.4% transmission rate).

To summarize, immediately after delivery, the oral microbiota of the child does not resemble any particular microbiota of its mother. Although the impact of the birth mode on the oral microbiota seems to fade over time, the consequences imposed by this initial inoculation may extend beyond the first few months of life.

3. First months after delivery

A few days after delivery, the oral microbiota of the child starts resembling the oral microbiota of its mother and it seems that this similarity remains during the first months after delivery. Chu et al. (2017) [55] assessed longitudinally (at delivery and 4–6 weeks postpartum) 81 pairs of American mothers and their infants. The neonatal microbiota structure did not present any differentiation across any site of the body, unlike the mother, whose microbial community structure was mainly differentiated by body site. Conversely, at 6 weeks of age, the microbial communities seemed to be shifting due to body niche differences and the oral microbiota already clustered distinctly. Patterns of beta diversity and signature taxa were similar to maternal communities, with Streptococcus dominating their gingiva. In terms of shared operational taxonomic units (OTUs), the oral samples of the children clustered differently from those of their mothers. As for microbial diversity, the authors reported that children at 6 weeks of age have a simpler oral microbial community than their mothers. Similarly, Drell et al. (2017) [56] studied longitudinally a population of 7 Estonian mother-child dyads from birth to 6 months postpartum. Oral and gut communities were significantly different between mothers and their children, who presented lower diversity throughout the study. The highest proportion of shared OTUs was between the oral microbiota of mother and child and these belonged mainly to the genus Streptococcus. Bacillota constituted a large part of the oral microbiota of the infant in all time-points and dominated all the maternal communities analyzed. At lower taxonomic levels, Streptococcaceae and Pasteurellaceae were predominant in the oral cavity of children and Streptococcaceae, Prevotellaceae, Micrococcaceae, Pasteurellaceae and Veillonellaceae dominated the oral cavity of mothers. Oral communities were relatively stable during the time-period of the study. The authors concluded that the dominance of the same OTUs in oral microbiota of both mother and child indicates that, in comparison to the gut, the maternal oral microbiota has the largest influence on the acquisition and development of the oral microbiota in the first 6 months of life.

The feeding mode also seems to influence the oral microbiota in early life. Breastmilk is the usual initial nourishment of the infant and provides micro- and macronutrients, as well as bioactive molecules, such as immune cells, human milk oligosaccharides, cytokines, among others, presenting itself as crucial in the healthy development of the child [57], [58]. Given its benefits, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends exclusive breastfeeding until the age of six months [59]. Furthermore, breastfeeding exposes the infant continuously to the maternal vertically transmitted milk microbiota [57]. In fact, it is even hypothesized that breastmilk microbiota is originated from the maternal gastrointestinal tract by migration to the mammary glands via an endogenous cellular route, also known as the bacterial entero-mammary pathway [60]. These microorganisms would then colonize the gastrointestinal tract of the breastfed infant. Holgerson et al. (2013) [61] isolated oral species from a cohort of exclusively breastfed, partially breastfed, and formula-fed infants at 3 months of age. The authors verified that lactobacilli were only retrieved from exclusively and partially breastfed infants (27.8%) but not from formula-fed infants. These recovered isolates were tested for their growth inhibition ability of streptococci and, interestingly, they inhibited the growth of selected streptococci such as Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguinis, suggesting a potential protective role of the breastmilk. Moreover, Williams et al. (2019) [62] longitudinally assessed a cohort of 21 healthy American mother-child pairs from 2 days to 6 months postpartum. The 5 most-abundant genera in milk and mother-child oral microbiota were Streptococcus, Staphylococcus (except for the maternal oral microbiota), Gemella, Rothia, and Veillonella. The microbial diversity decreased in the child oral samples (day 2 until 5 months). Milk and the child’s oral microbiota as well as maternal and child’s oral microbiota became increasingly similar with time.

Nevertheless, these initial differences due to feeding mode in regard to oral diversity and composition seem to fade over time. Hurley et al. (2019) [48] observed that breastfeeding for less or more than 4 months did not influence the oral microbiota of children, regardless of the birth mode. A recent study by Eshriqui et al. (2020) [63] assessed the impact of breastfeeding in the oral microbiota of adolescents. Although abundance of commensal OTUs belonging to genera Veillonella and Eubacteria were higher in adolescents who had not been fed with formula, no differences were reported in the overall alpha diversity of the oral microbiota. Likewise, no differences were also reported regarding the beta diversity, which refers to the microbial compositional variability among different samples from a specific niche., The authors observed that the initial differences in composition at early age due to feeding mode did not persist over time. Nevertheless, after adjusting for age, delivery mode, and geographic area, infants who were breastfed had lower relative abundance of Veillonella, Prevotella, Granulicatella, and Porphyromonas.

In brief, the oral microbiota of the child starts resembling microbiota of its mother a few days postpartum, given the close proximity of the two, and the feeding mode seems to influence the oral microbiota of the child, although differences do not persist after the first months of life.

4. Teeth eruption and diet changes

Although the microbial diversity of the oral microbiota of the child increases with time, the similarity between the oral microbiota of mother and child seems to be disrupted around 6–9 months of age, concomitant with diet changes and eruption of teeth (Table 2). According to WHO, complementary feeding should be introduced around 6 months of age [64]. During this period, diet of infants changes considerably. Complementary food introduction heavily impacts the human microbiota [65]. Most studies on the effects of diet focus on the gut microbiota, where an increase in alpha diversity (evenness and richness) is observed and can be interpreted as a sign of microbiota stabilization [66], [67]. Regarding the oral cavity, a study by Koren et al. (2021) [68] using a murine model, demonstrated that neonate oral cavity colonization levels seem to decline to adult levels during weaning, seemingly being mediated by the upregulation of saliva production and induction of salivary antimicrobial components by the microbiota [68]. Moreover, a study by Oba et al. (2020) [69] reported that the oral microbiota of breastfed/formula-fed children had a different taxonomic profile when compared to children receiving solid food and breastmilk/formula, with the latter having an increased abundance of Gemella, Veillonella, Fusobacterium, Neisseria, and Actinobacillus [69]. As observed with the gut microbiota, species richness was higher in children who received solid food versus breastfed infants and mixed-fed children.

Table 2.

Impact of solid food introduction and teeth eruption in the oral microbiota.

| Author (year) | Type of study & Number of participants |

Type of Samples | Moment of sampling | DNA sequencing technique & Taxonomic Database |

Teeth Eruption & Solid Food Introduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oba et al. (2020)[128] | Longitudinal study 12 infants |

Tongue and cheek swabs | 2, 4, and 6 months of life | Sequencing of the 16 S rRNA (V3-V5) Greengenes |

At age of 2 months, children exclusively breastfed had a higher abundance of Streptococcus and lower abundance of Veillonella. At 6 months, these children had a higher abundance of unclassified Weeksellaceae versus mixed feeding children. Overall, infants who received solid foods had higher abundance of Gemella, unclassified Streptococcaceae, Veillonella, Fusobacterium, and Neisseria. Children who ingest solid food had a higher alpha diversity compared to children breastfed, formula-fed, or mixed-fed. |

| Mason, M.R. et al. (2018)[129] Mason et al. (2018)[129] |

Cross-sectional study 143 caries-free children; 60 mother-child pairs (caries-free children). |

Mucosal biofilm (Mo/Ch); Saliva (Mo/Ch); Supragingival and subgingival biofilm (Mo/Ch). |

Pre-dentate, primary, mixed, and permanent dentitions | Sequencing of the 16 S rRNA (V1–V3; V7–V9) Human Oral Microbiome Database (HOMD) |

In a pre-dentate stage, children shared 85% of OTUs their mothers. However, with the eruption of teeth, the similarity between mother and child in their oral microbiota decreased and remained stable throughout all dentition stages. |

| Sulvanto, RM et al. (2019)[130] | Longitudinal study 9 mother-child pairs |

Saliva, either by spitting (Mo) and swabbing the lingual vestibule (Ch) | Infant and maternal saliva samples were collected monthly for twelve months (baseline sample taken within 2 weeks after birth) | Sequencing of the 16 S rRNA (V1-V3 region) CORE Database |

Introduction of solid foods, but not tooth eruption, influenced the oral microbial diversity and composition. Solid food introduction increased alpha diversity. Streptococcus mitis became a significantly lower proportion of the total community over time. |

| Hurley et al. (2019)[48] | Longitudinal study 84 mother-child pairs |

Saliva (Mo/Ch) and vaginal/skin sample (Mo). | At delivery (Mo); 1, 4 and 8 weeks after birth, 6 months and 1 year of age (Ch). | Sequencing of the 16 S rRNA (V6). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (q-PCR) for certain species. CORE database |

Some changes from 6 months to 1 year of age may be explained by teeth eruption. These include increased abundance of Pseudomonadota and Bacteroidota and a decrease in Bacillota and Streptococcus. |

Mo – Mother. Ch – Child.

The eruption of teeth also begins at approximately 6 months of age and is associated with large ecological changes. Dental surfaces acquire a glycoprotein coat, also known as acquired pellicle, that shifts the colonization patterns [70]. Gingival sulci and interproximal spaces between teeth further contribute to the diversity of environments in the oral cavity for microbial colonization and growth, rich in serum and acids and poor in saliva and oxygen [71], [72]. After teeth eruption, planktonic bacteria bind to proteins of the acquired pellicle, resulting in polymicrobial biofilm formation [70]. Usually, these initial microorganisms belong to Streptococcus spp., Actinomyces spp., Haemophilus spp., Capnocytophaga spp., Veillonella spp., and Neisseria spp. [73]. Later colonization by other species is conditioned by these bacteria, as they recognize specific polysaccharide or protein receptors and attach by a process called coaggregation, which contributes to the biofilm maturation [42]. These late colonizers include species such as Fusobacterium nucleatum, Tannerella forsythia, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans [42]. Aggregation and co-adhesion are crucial for biofilm formation and allow bacterial strains to aggregate to each other as well as to co-adhered to epithelial cells [73]. The concept of early and late colonizer is currently under debate since these two groups of bacteria have been described to adhere together in multispecies aggregates in dental plaque samples [74].

Few studies have explored the evolution of the oral microbiota in children in parallel with their mothers during the eruption phase. characterized the oral microbiota communities across dentition states in 143 caries-free American children and 60 mother-child pairs. The oral microbial community composition and structure of pre-dentate children resembled their mother, with each child sharing 85% of their OTUs with their mother. However, with the eruption of teeth, the similarity between mother and child in their oral microbiota decreased and remained stable throughout all dentition stages. Likewise, Hurley et al. (2019) [48] reported remarkable differences in the alpha diversity of the oral microbiota of children at 6 months, suggesting that the oral microbiota this age undergoes significant changes possibly due to teeth eruption. The abundance of Bacillota begins to decrease from 6 months until 1 year and, concomitantly, the abundance of Pseudomonadota and Bacteroidota increases at around 1 year. At the genus level, Streptococcus gradually decreases in abundance from week 1–1 year of age, which is counteracted by increased abundance of the genera Neisseria, Porphyromonas, Rothia, Gemella and Haemophillus by 1 year of age. Sulyanto et al. (2019) [75] examined monthly the oral bacterial acquisition up to 12 months of life of 9 infants and their mothers. Although the overall oral microbial composition of mother and child differed, the most common species in children were also present in the mothers. In fact, when relative abundance was considered, the shared set of species accounted for two-thirds of the microbial communities at all ages. The authors suggest that the dominant ecological structure of the oral microbiota establishes early in life and the mother seems to have a pivotal role.

To sum up, this period implicates a large shift in the oral microbiota of the child due to physiological and nutritional alterations; in consequence, the similarities with the maternal oral microbiota decrease during this stage.

5. Transmission of mutans streptococci and periodontal pathogens

Since 1980, there is robust evidence that the mother is able to transmit mutans streptococci to her child in early life. Several techniques have been employed since then to identify species-level transmission of these cariogenic bacteria, from bacteriocin typing and ribotyping [76], [77], deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) fingerprinting [78], [79], arbitrarily primed polymerase chain reaction (AP-PCR) [80], [81], repetitive element sequence-based PCR [82], and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) [83].[83]. According to a meta-analysis by da Silva Bastos Vde et al. (2015) [84], the transmission rate does not seem to be statistically different according to the type of technique used to assess transmission. Due to the limitations of 16 S rRNA gene sequencing in identifying microorganisms at strain-level, culture-dependent methods followed by molecular identification are still relevant for oral streptococci identification.

According to literature, some predisposing factors for mutans streptococci transmission include a high maternal colonization, child teeth eruption and its timing, and behaviors that promote vertical transmission of these microorganisms (e.g. pacifier licking) [85], [86]. In fact, a recent study by Subramaniam and Suresh (2019) [81] found that high maternal levels of S. mutans was a significant factor for colonization by S. mutans in pre-school children. Similarly, Childers et al. (2017) [82] reported that more than 50% of mother-child pairs shared the same S. mutans genotypes and observed that at 36 months, the estimated decayed, missing, and filled surfaces of teeth of these children was 2.61 times higher than in children without matching genotypes.

Interestingly, the genotypes transmitted by the mother seem to persist over time. Klein et al. (2004) [87] reported that over 80% of mother-child pairs shared similar genotypes of S. mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus at 6 months of age and, although the genotypic diversity of S. mutans changed in the oral cavity, the initially acquired genotypes persisted, in particularly those transmitted by the mother. Furthermore, Kohler et al. (2003) [77] reported that 88% of the mother-child pairs shared at least one strain of S. mutans and 10 of the 13 families assessed longitudinally kept at least one strain over a period of 16 years.

Regarding the importance of teeth eruption and its timing on S. mutans colonization, Damle et al. (2016) [80] reported that colonization by S. mutans increases with age (30% of colonization in pre-dentate phase, and 100% of colonization at 30 months of age) and matching genotypes of S. mutans were found in 77.3% of mother-child pairs. In fact, Lynch et al. (2015) [86] described that, in their population, children acquired S. mutans earlier than what is described for other populations, which could be explained by the earlier teeth eruption in their study compared to others. This factor may thereby be implicated in early S. mutans acquisition and increase the risk of early childhood caries.

Additionally, maternal oral health and behaviors, such as licking the child’s pacifier, sharing kitchen utensils, and kissing the child on the mouth, may be associated with a higher transmission of cariogenic species [80], [88]. Interestingly, Damle et al. (2016) [80] also reported that feeding habits, gum cleaning, number of teeth and sharing the spoon with the mother were factors that significantly influenced S. mutans colonization. Nevertheless, evidence suggests that the colonization of early acquired S. mutans strains, particularly those transmitted by the mothers, persist through childhood until young adulthood [77], [80].

It is noteworthy stating that there is a great heterogeneity between studies regarding the type of samples used, which can also bias mutans streptococci identification. These species adhere to dental surfaces and this may be the reason for the absence in other types of oral samples.

Regarding specific periodontal pathogens and contrarily to what was observed for cariogenic microorganisms, the existing evidence does not seem to support vertical transmission. Rêgo et al. (2007) [89] studied the transmission of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans in 30 mothers with severe periodontitis and their children. A. actinomycetemcomitans was found in 26.6% of women; however, this bacterium was only found in 2 children of these mothers and there was no similarity between the strains present in the dyads. Likewise, Shimoyama et al. (2017) [90] evaluated the prevalence of Porphyromonas gingivalis and their virulence gene fimbrillin (fimA), but, in most cases, the bacterial prevalence and strains were distinct from the mother, indicating that vertical transmission was not significant. Also Kahharova et al. (2020) [91] verified that the presence of zOTUs corresponding to P. gingivalis was at a low relative abundance and in a small proportion of children, contrarily to what was observed for S. mutans in a caries-free population. Kononen et al. (2000) [92] examined the colonization by the Prevotella intermedia group in 23 mother-child pairs and verified that P. intermedia was almost exclusively found in mothers with periodontitis, whereas Prevotella nigrescens and Prevotella pallens were recovered in mother and child. In fact, distinct colonization patterns were observed for P. nigrescens and P. pallens and the presence of similar genotypes between mother and child was mainly observed in health.

In brief, it seems that while the mother may represent a source of cariogenic microorganisms in early life, the same may not apply to periodontopathogens at this stage. Nevertheless, more studies are needed to understand the timing and the role of different sources of pathogenic microorganisms in infancy.

6. The influence of other caregivers and horizontal transmission in the oral microbiota from childhood to adulthood

After the eruption of primary teeth is completed, it seems that the similarity in oral microbiota between mother and child begins to converge again, which may be consolidated by the sharing of a common household. Despite evidence supporting the important role of the mother on the vertical transmission of oral microbiota, various genotypes unrelated to the mother have been identified, foreshadowing a possible role for other intrafamilial and extrafamilial transmission sources, such as the father, other caretakers, and daycare or school classmates [93]. Additionally, events as primary tooth exfoliation, use of orthodontic appliances, and the hormonal changes during adolescence may impact the oral microbiota of the child [94].

Regarding the similarity with the maternal microbiota throughout this period of time, in 2 families evaluated, Sundström et al. (2020) [95] observed that mothers shared more OTUs with adult children compared to fathers, but this linkage seemed to be weaker in older children adult (aged 50–53 years old). Jo et al. (2021) [96] performed a cross-sectional study with 18-month-old children and their parents (N = 40) and observed that, despite significant differences between the oral microbiota of infants and adults, the similarity and abundance of OTUs between children and their mother was significantly higher than to unrelated mothers. Regarding the fathers, the oral microbiota of the children was not different from unrelated fathers. Also, Mukherjee et al. (2021) [97] assessed a group of biological and adopted children (N = 50) in different age groups from 3 months to 6 years. The authors observed that microbial profiles were similar (both at species and strain levels) between mother and child, either biological or adopted. Adopted and biological children shared 44% and 15% of their species and strains with their mothers, respectively. However, when considering the relative abundance, these percentages increased to 93% and 48%, respectively. The findings led the authors to hypothesize that the increased overall diversity with age may be responsible for the increasing similarity between mother and child, since the Shannon diversity index increased during early years, reaching levels comparable to mothers at the age of 5.

As for the role of co-habitation with other household members, Song et al. (2013) [98] collected a range of samples from 159 members of 60 American families with/without cohabiting children aged between 6 months and 18 years old or their dogs. Regarding human microbial community composition, household members tended to have more similar levels of bacterial diversity, as measured by Faith’s phylogenetic diversity. Nevertheless, the similarity between parent and offspring seemed to depend majorly on the age of the child. Parents shared significantly more similar tongue microbial communities with their own children (3–18 years) than with other children, but the same was not the case for parents and their younger infants (0–12 months). Curiously, dog-owning adults shared more skin microbiota with their dogs than to unrelated dogs, but this effect was not observed in children [106]. Burcham et al. (2020) Burcham et al. (2020) [99] explored the similarities between the oral microbiota of household members (N = 351 participants, from which 172 were adults and 179 were children with a median age of 10 years) and verified that cohabitation and familial relationships impact the oral microbiota similarity more than genetics, particularly regarding rare taxa. Moreover, intra-family relationships and cohabitation leads to less variation in similarity and, therefore, to the sharing of a core and rare taxa. The oral microbiota was dominated by Streptococcus, Haemophilus, Rothia, Neisseria, and Veillonella, which made up 85.4% of adult genera and 71.7% of youth genera. There were 12 genera differentially abundant in adults and children, with the three most significantly differential being Abiotrophia, Granulicatella (more abundant in youth) and Treponema (more abundant in adults).

Concerning the role of periodontal status of the parents in the oral microbiota of older children, Monteiro et al. (2021) [32] followed a cohort of children (N = 18), aged 6–12 years, whose parents were either healthy or diagnosed with periodontitis. No differences were identified in the beta diversity between parent-child dyad in both groups. The similarity between parents and their children was greater than between non-related individuals, which suggests a significant role of parental periodontal health in determining the colonizing species of the child. Interestingly, parents with periodontitis had a median 70% similarity with their child, versus 40% between healthy parent and child. Children of parents with periodontitis scored higher in the Bleeding on Probing index, which measures gingival inflammation. Moreover, microbiologically, these children presented higher species richness in the subgingival microbiota and species such as Filifactor alocis, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Streptococcus parasanguinis, Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. nucleatum and belonging to the genus Selenomonas were exclusively found in this group. This suggests that some periodontitis-related bacteria may colonize these children from an early age and may be vertically transmitted. The authors also did an intervention to control biofilm formation in the children from these two groups. However, they did not verify any difference in the microbial profile afterwards, which seems to indicate that vertical transmission may impact oral colonization more deeply than environmental or oral hygiene factors in this age group.

Regarding horizontal transmission, some studies observed that the acquisition of S. mutans from non-maternal sources is also noteworthy [100], [101]. In fact, a great proportion of children attend nurseries and schools worldwide, where they contact other children, caretakers, and different environments. This exposure may favor the transmission of oral microbiota and cariogenic species[102]. For instance, Lindquist and Emilson (2004) [101] followed a group of 15 mother-child pairs for 7 years and observed that 10 of the 15 children acquired S. mutans and only 4 of them were colonized by both S. mutans and S. sobrinus, although their mothers presented both species. However, only 9 out of 26 genotypes were identical between mother and child, which raised questions regarding the possibility of horizontal transmission or vertical transmission from other family members. Furthermore, Baca et al. (2012) [103] reported that, in a group of 42 schoolchildren aged 6–7 years, five genotypes were isolated in more than 1 schoolchild, suggesting that these children may be the source of mutual transmission of S. mutans. Moreover, a meta-analysis by Manchanda et al. (2021) [93] concluded that horizontal transmission of S. mutans genotypes occurs among children at home or in schools and that children who shared more than one genotype with other children had a higher risk for dental caries. Still, horizontal transmission usually occurs after vertical transmission has taken place and contributes further to the diversity of S. mutans colonizing the oral cavity [85].

Taken together, evidence suggests that the similarities between the oral microbiota of mother and child may increase and be perpetuated due to the sharing of a common household during childhood and adolescence. The identification of common strains confirms that vertical transmission may happen in early life and remains relevant in a later stage of life. However, evidence also demonstrates that the mother is not the exclusive source of microorganisms for the child and that the contact with different caregivers, other children, and several environments may also play an important role at this stage. Nevertheless, only a few studies approach the characterization of non-maternal sources of microorganisms in infancy and adolescence and further research is required.

7. Clinical relevance of the influence of the mother in early life oral microbiota

The mother plays an important role in the child’s microbiota acquisition, establishment and maturation. Even though the oral microbiota may only stabilize later than gut microbiota, early life events seem to interfere in its future composition. A recent study by Charalambous et al. (2021) [104] reported that once the oral microbiota is established in early life, it remains stable and resilient, retaining an imprint of the early life environment and early adverse events (i.e. potentially traumatic events, often associated with low socioeconomic status and correlated with a lifelong imbalance of health and disease) up to 24 years after they occur. This evidence suggests that differences in the initial microbiota may have repercussions in oral health and disturbances in this process may predispose to the most common oral diseases [32], [105].

In this context, some authors suggested interventions to prevent the development of future diseases from early-life. An increasingly explored strategy is seeding C-section-delivered neonates with maternal vaginal microbiota, also known as vaginal seeding [106]. Evidence suggests infants delivered by C-section have increased risk of developing chronic inflammatory and metabolic diseases, such as eczema, asthma, or even obesity [107]. To counteract the possible deleterious effect of C-section, maternal vaginal samples are collected and processed to be administered to the child, either through oral or skin inoculation [108], [109]. Theoretically, through vaginal seeding it would be possible to restore the microbiota of the infant and normalize the development of their immune system. Despite its putative potential, there is still controversy surrounding this intervention and concerns regarding its safety, ethics, and long-term efficacy in terms of health outcomes [110]. In the context of oral microbiota and health, little is known about its benefits. Dominguez-Bello et al. (2016) [111] performed a pilot study in which four C-section-delivered neonates were rubbed with maternal vaginal fluids and their microbiota was compared to babies born vaginally (N = 7) and born by C-section but without intervention (N = 8). The authors collected samples from different niches of the neonate throughout the first month of life. They observed that the oral and skin microbiota of infants seeded with their maternal vaginal microbiota resembled infants born by vaginal delivery. Overall, it seemed that their microbiota was partially restored after inoculation. However, the authors concluded that the long-term health consequences of restoring the microbiota of these neonates are not clear and should be further investigated [111].

Regarding dental caries, there is plenty of evidence suggesting that the vertical transmission of S. mutans between mother and child increases the risk of developing early childhood caries [82], [84], [112]. The transmission of bacteria typically associated with periodontal disease it may also happen, although there is less robust evidence on this topic [89], [90], [113]. Considering this, clinical trials and educational programs have been implemented as early as the prenatal period, aiming to minimize the transmission of maternal oral bacteria and thereby prevent the development of oral diseases. These strategies may vary between xylitol gum chewing by the mothers [114], [115], [116], use of antiseptic mouthwashes [116], [117], topical fluoride application [117], and educational sessions with the mother [118]. For instance, a study by Köhler and Andréen (2010) [118] that included an 11- and 15-year follow-up after an educational program in mothers (N = 62) with high and low levels of S. mutans and their respective children (N = 65 at 11 years of age and N = 72 at 15 years of age) demonstrated that there seems to be a long-term beneficial effect on the levels of S. mutans and carious lesions 15 years after the intervention. In this trial, a group of mothers with high levels of S. mutans were educated about oral health and diet, received treatment for dental caries, and applied repeatedly chlorhexidine gel to reduce S. mutans counts, which effectively reduced caries in their children. Moreover, Li and Tanner (2015) [119] performed a meta-analysis to assess the clinical effectiveness of antimicrobial interventions in the reduction of cariogenic bacteria. The authors verified that xylitol-based interventions were effective in reducing ECC and mutans streptococci counts. Interestingly, a recent meta-analysis by Riggs et al. (2019) [120] found moderate evidence that educational programs may be more effective than other types of interventions in preventing early childhood caries. However, studies from different populations [121], [122], [123], [124] agreed that the knowledge and attitudes of mothers regarding the association of their oral health with the oral health of the child was still insufficient. For instance, a study performed with an Italian population reported that about 53.6% of the 304 parents were not aware of the potential vertical transmission of cariogenic bacteria through saliva, with 53% of parents reporting to taste the food of the infant and 38.5% admitting to share cutlery with the infant [123]. Considering the lack of awareness regarding the impact of vertical transmission of oral bacteria, it is important to reinforce educational programs in maternities.

Lastly, it is fundamental to highlight that, despite the recognized cariogenic potential of mutans streptococci, these microorganisms are not the only culprits of dental caries. Nowadays, it is agreed that dental caries are seen as a biofilm-associated disease and a shift in the dental biofilm microbiota in the presence of fermentable carbohydrates leads to tooth demineralization [125]. Future research in this field should focus on the interplay within dental plaque biofilm to understand their complex microbial interactions in the pathophysiology of dental caries.

To sum up, the maternal transfer of microbiota may leave a durable imprint on the biology of the offspring by engaging in a reciprocal and dynamic relationship with the host, which can control the balance between oral health/disease throughout life. Given this scenario, the application of preventive and educational programs is fundamental to instruct caregivers on the importance of maintaining good oral health and its consequences on the oral microbiota, on the vertical transmission and its importance on the oral health of the child in early life.

8. General remarks and future directions

In conclusion, the mother may influence the oral microbiota of the child since gestation and throughout early life through multiple routes of vertical transmission. Cariogenic species from maternal origin, such as S. mutans, are most likely vertically transmitted, whereas the vertical transmission of periodontal pathogens should be further investigated. Therefore, non-maternal sources may also play a role in the oral colonization of the child. This early-life transmission may impact the oral pathophysiological outcome of the child from childhood to adulthood. For this reason, it is fundamental to implement preventive programs from a prenatal period. Although increasingly more evidence describes the characterization of the oral microbiota of both mothers and children, the mechanisms of transmission, colonization, and clinical significance on and beyond oral health are still unclear. With whole genome shotgun sequencing (WGS), we are now gaining a deeper, more accurate and precise insight at the strain-level transmission of the microbiota from different sources. In the meantime, more longitudinal large-scale studies are needed to understand the mechanisms of transmission and colonization of the oral microbiota, to evaluate the similarities between strains present in mother-child pairs and the impact of other main caregivers. Despite the great amount of information provided by WGS, it is necessary to reinforce that traditional microbiological studies are also fundamental to clarify the pathogenicity and virulence of different strains, both vertically and horizontally transmitted, found in the oral cavity of children to understand the role of both sources in the oral health of children. Combined, and considering that oral diseases remain one of the most prevalent conditions worldwide, this information can be used to develop personalized preventive programs from early childhood.

Funding

This research was funded by BIOCODEX (Biocodex National Call 2021 – Portugal) and by a Research Grant 2021 from the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) to MJA. MJA PhD fellowship was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia/Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior (FCT) scholarship (SFRH/BD/144982/2019). AG PhD fellowship was supported by FCT (UI/BD/151316/2021). CC PhD fellowship was supported by FCT scholarship (2020.08540. BD). AFF PhD fellowship was supported by FCT scholarship (SFRH/BD/138925/2018).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Scientific field of dental Science: Pediatric Oral Health Research.

References

- 1.Mukherjee C., Moyer C.O., Steinkamp H.M., Hashmi S.B., Beall C.J., Guo X., et al. Acquisition of oral microbiota is driven by environment, not host genetics. Microbiome. 2021;9(1) doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00986-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Proctor L. After the Integrative Human Microbiome Project, what's next for the microbiome community? Nature. 2019;569(7758):599. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-01674-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lloyd-Price J., Abu-Ali G., Huttenhower C. The healthy human microbiome. Genome Med. 2016;8(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0307-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blum H.E. The human microbiome. Adv Med Sci. 2017;62(2):414–420. doi: 10.1016/j.advms.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davenport E.R., Sanders J.G., Song S.J., Amato K.R., Clark A.G., Knight R. The human microbiome in evolution. BMC Biol. 2017;15(1):127. doi: 10.1186/s12915-017-0454-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sedghi L., DiMassa V., Harrington A., Lynch S.V., Kapila Y.L. The oral microbiome: Role of key organisms and complex networks in oral health and disease. Periodontol 2000. 2021;87(1):107–131. doi: 10.1111/prd.12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bana B., Cabreiro F. The Microbiome and Aging. Annu Rev Genet. 2019;53:239–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-112618-043650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kilian M. The oral microbiome - friend or foe? Eur J Oral Sci. 2018;126(Suppl 1):5–12. doi: 10.1111/eos.12527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rooks M.G., Garrett W.S. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(6):341–352. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graves D.T., Correa J.D., Silva T.A. The oral microbiota is modified by systemic diseases. J Dent Res. 2019;98(2):148–156. doi: 10.1177/0022034518805739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zarco M.F., Vess T.J., Ginsburg G.S. The oral microbiome in health and disease and the potential impact on personalized dental medicine. Oral Dis. 2012;18(2):109–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arweiler N.B., Netuschil L. The oral microbiota. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;902:45–60. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-31248-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X., Liu Y., Yang X., Li C., Song Z. The oral microbiota: community composition, influencing factors, pathogenesis, and interventions. Front Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.895537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang C.Z., Cheng X.Q., Li J.Y., Zhang P., Yi P., Xu X., et al. Saliva in the diagnosis of diseases. Int J Oral Sci. 2016;8(3):133–137. doi: 10.1038/ijos.2016.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verma D., Garg P.K., Dubey A.K. Insights into the human oral microbiome. Arch Microbiol. 2018;200(4):525–540. doi: 10.1007/s00203-018-1505-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosier B.T., Marsh P.D., Mira A. Resilience of the Oral Microbiota in Health: Mechanisms That Prevent Dysbiosis. J Dent Res. 2018;97(4):371–380. doi: 10.1177/0022034517742139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He J., Li Y., Cao Y., Xue J., Zhou X. The oral microbiome diversity and its relation to human diseases. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2015;60(1):69–80. doi: 10.1007/s12223-014-0342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Y., Cai Q., Zheng W., Steinwandel M., Blot W.J., Shu X.O., et al. Oral microbiome and obesity in a large study of low-income and African-American populations. J Oral Microbiol. 2019;11(1):1650597. doi: 10.1080/20002297.2019.1650597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nardi G.M., Grassi R., Ndokaj A., Antonioni M., Jedlinski M., Rumi G., et al. Maternal and Neonatal Oral Microbiome Developmental Patterns and Correlated Factors: A Systematic Review-Does the Apple Fall Close to the Tree? Int J Environ. 2021;18(11) doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sampaio-Maia B., Monteiro-Silva F. Acquisition and maturation of oral microbiome throughout childhood: An update. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2014;11(3):291–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dzidic M., Collado M.C., Abrahamsson T., Artacho A., Stensson M., Jenmalm M.C., et al. Oral microbiome development during childhood: an ecological succession influenced by postnatal factors and associated with tooth decay. ISME J. 2018;12(9):2292–2306. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0204-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y., Caufield P.W., Dasanayake A.P., Wiener H.W., Vermund S.H. Mode of delivery and other maternal factors influence the acquisition of Streptococcus mutans in infants. J Dent Res. 2005;84(9):806–811. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marsh P.D., Zaura E. Dental biofilm: ecological interactions in health and disease. J Clin Periodo. 2017;44(S18):S12–S22. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aagaard K., Ma J., Antony K.M., Ganu R., Petrosino J., Versalovic J. The placenta harbors a unique microbiome. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(237):237ra65. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fardini Y., Chung P., Dumm R., Joshi N., Han Y.W. Transmission of diverse oral bacteria to murine placenta: evidence for the oral microbiome as a potential source of intrauterine infection. Infect Immun. 2010;78(4):1789–1796. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01395-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borghi E., Massa V., Severgnini M., Fazio G., Avagliano L., Menegola E., et al. Antenatal Microbial Colonization of Mammalian Gut. Reprod Sci (Thousand Oaks, Calif) 2019;26(8):1045–1053. doi: 10.1177/1933719118804411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Goffau M.C., Lager S., Sovio U., Gaccioli F., Cook E., Peacock S.J., et al. Human placenta has no microbiome but can contain potential pathogens. Nature. 2019;572(7769):329–334. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1451-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez A., Nelson K.E. The Oral Microbiome of Children: Development, Disease, and Implications Beyond Oral Health. Micro Ecol. 2017;73(2):492–503. doi: 10.1007/s00248-016-0854-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gil A.M., Duarte D., Pinto J., Barros A.S. Assessing exposome effects on pregnancy through urine metabolomics of a Portuguese (Estarreja) Cohort. J Proteome Res. 2018;17(3):1278–1289. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDonald B., McCoy K.D. Maternal microbiota in pregnancy and early life. Science. 2019;365(6457):984–985. doi: 10.1126/science.aay0618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamburini S., Shen N., Wu H.C., Clemente J.C. The microbiome in early life: implications for health outcomes. Nat Med. 2016;22(7):713–722. doi: 10.1038/nm.4142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monteiro M.F., Altabtbaei K., Kumar P.S., Casati M.Z., Ruiz K.G.S., Sallum E.A., et al. Parents with periodontitis impact the subgingival colonization of their offspring. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80372-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferretti P., Pasolli E., Tett A., Asnicar F., Gorfer V., Fedi S., et al. Mother-to-infant microbial transmission from different body sites shapes the developing infant gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;24(1):133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.06.005. e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiménez E., Fernández L., Marín M.L., Martín R., Odriozola J.M., Nueno-Palop C., et al. Isolation of commensal bacteria from umbilical cord blood of healthy neonates born by cesarean section. Curr Microbiol. 2005;51(4):270–274. doi: 10.1007/s00284-005-0020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jimenez E., Marin M.L., Martin R., Odriozola J.M., Olivares M., Xaus J., et al. Is meconium from healthy newborns actually sterile? Res Microbiol. 2008;159(3):187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stout M.J., Conlon B., Landeau M., Lee I., Bower C., Zhao Q., et al. Identification of intracellular bacteria in the basal plate of the human placenta in term and preterm gestations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208(3) doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.01.018. 226 e1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu S., Yu F., Ma L., Zhao Y., Zheng X., Li X., et al. Do maternal microbes shape newborn oral microbes? Indian J Microbiol. 2021;61(1):16–23. doi: 10.1007/s12088-020-00901-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gomez-Arango L.F., Barrett H.L., McIntyre H.D., Callaway L.K., Morrison M., Nitert M.D. Contributions of the maternal oral and gut microbiome to placental microbial colonization in overweight and obese pregnant women. Sci Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03066-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaura E., Nicu E.A., Krom B.P., Keijser B.J.F. Acquiring and maintaining a normal oral microbiome: current perspective. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;4 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu M., Chen S.W., Jiang S.Y. Relationship between gingival inflammation and pregnancy. Mediat Inflamm. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/623427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang S., Ryan C.A., Boyaval P., Dempsey E.M., Ross R.P., Stanton C. Maternal vertical transmission affecting early-life microbiota development. Trends Microbiol. 2020;28(1):28–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2019.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kriebel K., Hieke C., Müller-Hilke B., Nakata M., Kreikemeyer B. Oral Biofilms from Symbiotic to Pathogenic Interactions and Associated Disease –Connection of Periodontitis and Rheumatic Arthritis by Peptidylarginine Deiminase. Front Microbiol. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nelson-Filho P., Borba I.G., Mesquita K.S., Silva R.A., Queiroz A.M., Silva L.A. Dynamics of microbial colonization of the oral cavity in newborns. Braz Dent J. 2013;24(4):415–419. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440201302266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nelun Barfod M., Magnusson K., Lexner M.O., Blomqvist S., Dahlén G., Twetman S. Oral microflora in infants delivered vaginally and by caesarean section. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2011;21(6):401–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2011.01136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dominguez-Bello M.G., De Jesus-Laboy K.M., Shen N., Cox L.M., Amir A., Gonzalez A., et al. Partial restoration of the microbiota of cesarean-born infants via vaginal microbial transfer. Nat Med. 2016;22(3):250–253. doi: 10.1038/nm.4039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dominguez-Bello M.G., Costello E.K., Contreras M., Magris M., Hidalgo G., Fierer N., et al. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(26):11971–11975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002601107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li H., Wang J., Wu L., Luo J., Liang X., Xiao B., et al. The impacts of delivery mode on infant’s oral microflora. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):11938. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30397-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hurley E., Mullins D., Barrett M.P., O'Shea C.A., Kinirons M., Ryan C.A., et al. The microbiota of the mother at birth and its influence on the emerging infant oral microbiota from birth to 1 year of age: a cohort study. J Oral Microbiol. 2019;11(1):1599652. doi: 10.1080/20002297.2019.1599652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pattanaporn K., Saraithong P., Khongkhunthian S., Aleksejuniene J., Laohapensang P., Chhun N., et al. Mode of delivery, mutans streptococci colonization, and early childhood caries in three- to five-year-old Thai children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013;41(3):212–223. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gomez-Arango L.F., Barrett H.L., McIntyre H.D., Callaway L.K., Morrison M., Dekker, Nitert M. Antibiotic treatment at delivery shapes the initial oral microbiome in neonates. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43481. doi: 10.1038/srep43481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Romano-Keeler J., Weitkamp J.H. Maternal influences on fetal microbial colonization and immune development. Pedia Res. 2015;77(1–2):189–195. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li H., Xiao B., Zhang Y., Xiao S., Luo J., Huang W. Impact of maternal intrapartum antibiotics on the initial oral microbiome of neonates. Pedia Neonatol. 2019;60(6):654–661. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2019.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shin H., Pei Z., Martinez K.A., Rivera-Vinas J.I., Mendez K., Cavallin H., et al. The first microbial environment of infants born by C-section: the operating room microbes. Microbiome. 2015;3(1):59. doi: 10.1186/s40168-015-0126-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shao Y., Forster S.C., Tsaliki E., Vervier K., Strang A., Simpson N., et al. Stunted microbiota and opportunistic pathogen colonization in caesarean-section birth. Nature. 2019;574(7776):117–121. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1560-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chu D.M., Ma J., Prince A.L., Antony K.M., Seferovic M.D., Aagaard K.M. Maturation of the infant microbiome community structure and function across multiple body sites and in relation to mode of delivery. Nat Med. 2017;23(3):314–326. doi: 10.1038/nm.4272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Drell T., Stsepetova J., Simm J., Rull K., Aleksejeva A., Antson A., et al. The Influence of Different Maternal Microbial Communities on the Development of Infant Gut and Oral Microbiota. Sci Rep. 2017:7. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09278-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Granger C.L., Embleton N.D., Palmer J.M., Lamb C.A., Berrington J.E., Stewart C.J. Maternal breastmilk, infant gut microbiome and the impact on preterm infant health. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110(2):450–457. doi: 10.1111/apa.15534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Comberiati P., Costagliola G., D'Elios S., Peroni D. Prevention of Food Allergy: The Significance of Early Introduction. Med (Kaunas, Lith) 2019;55(7):323. doi: 10.3390/medicina55070323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guideline: Counselling of Women to Improve Breastfeeding Practices. WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. Geneva, 2018. [PubMed]

- 60.Rodríguez J.M. The origin of human milk bacteria: is there a bacterial entero-mammary pathway during late pregnancy and lactation? Adv Nutr. 2014;5(6):779–784. doi: 10.3945/an.114.007229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Holgerson P.L., Vestman N.R., Claesson R., Ohman C., Domellöf M., Tanner A.C.R., et al. Oral microbial profile discriminates breast-fed from formula-fed infants. J Pedia Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56(2):127–136. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31826f2bc6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Williams J.E., Carrothers J.M., Lackey K.A., Beatty N.F., Brooker S.L., Peterson H.K., et al. Strong Multivariate Relations Exist Among Milk, Oral, and Fecal Microbiomes in Mother-Infant Dyads During the First Six Months Postpartum. J Nutr. 2019;149(6):902–914. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxy299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eshriqui I., Viljakainen H.T., Ferreira S.R.G., Raju S.C., Weiderpass E., Figueiredo R.A.O. Breastfeeding may have a long-term effect on oral microbiota: results from the Fin-HIT cohort. Int Breast J. 2020;15(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s13006-020-00285-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.WHO P PAHO/WHO Guiding principles for Complementary Feeding of the Breastfed Child2001 01/01/2001 00:00:00; (0):[0 p.]. Available from: https://www.ennonline.net/compfeedingprinciples.

- 65.Bäckhed F., Roswall J., Peng Y., Feng Q., Jia H., Kovatcheva-Datchary P., et al. Dynamics and Stabilization of the Human Gut Microbiome during the First Year of Life. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17(5):690–703. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Homann C.M., Rossel C.A.J., Dizzell S., Bervoets L., Simioni J., Li J., et al. Infants' First Solid Foods: Impact on Gut Microbiota Development in Two Intercontinental Cohorts. Nutrients. 2021;13(8) doi: 10.3390/nu13082639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Laursen M.F., Andersen L.B.B., Michaelsen K.F., Mølgaard C., Trolle E., Bahl M.I., et al. Infant Gut Microbiota Development Is Driven by Transition to Family Foods Independent of Maternal Obesity. mSphere. 2016;1(1):e00069–15. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00069-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koren N., Zubeidat K., Saba Y., Horev Y., Barel O., Wilharm A., et al. Maturation of the neonatal oral mucosa involves unique epithelium-microbiota interactions. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29(2):197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.12.006. e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oba P.M., Holscher H.D., Mathai R.A., Kim J., Swanson K.S. Diet Influences the Oral Microbiota of Infants during the First Six Months of Life. Nutrients. 2020;12(11):3400. doi: 10.3390/nu12113400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alaluusua S., Asikainen S., Lai C.H. Intrafamilial transmission of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Periodo. 1991;62(3):207–210. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.3.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blum J., Silva M., Byrne S.J., Butler C.A., Adams G.G., Reynolds E.C., et al. Temporal development of the infant oral microbiome. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2022:1–13. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2021.2025042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sureda A., Daglia M., Argüelles Castilla S., Sanadgol N., Fazel Nabavi S., Khan H., et al. Oral microbiota and Alzheimer’s disease: Do all roads lead to Rome? Pharm Res. 2020;151 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang R., Li M., Gregory R.L. Bacterial interactions in dental biofilm. Virulence. 2011;2(5):435–444. doi: 10.4161/viru.2.5.16140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Simon-Soro A., Ren Z., Krom B.P., Hoogenkamp M.A., Cabello-Yeves P.J., Daniel S.G., et al. Polymicrobial Aggregates in Human Saliva Build the Oral Biofilm. mBio. 2022;13(1) doi: 10.1128/mbio.00131-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sulyanto R.M., Thompson Z.A., Beall C.J., Leys E.J., Griffen A.L. The Predominant Oral Microbiota Is Acquired Early in an Organized Pattern. Sci Rep. 2019:9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46923-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Berkowitz R.J., Jones P. Mouth-to-mouth transmission of the bacterium Streptococcus mutans between mother and child. Arch Oral Biol. 1985;30(4):377–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(85)90014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kohler B., Lundberg A.B., Birkhed D., Papapanou P.N. Longitudinal study of intrafamilial mutans streptococci ribotypes. Eur J Oral Sci. 2003;111(5):383–389. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2003.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li Y., Caufield P.W. The fidelity of initial acquisition of mutans streptococci by infants from their mothers. J Dent Res. 1995;74(2):681–685. doi: 10.1177/00220345950740020901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Emanuelsson I.R., Thornqvist E. Genotypes of mutans streptococci tend to persist in their host for several years. Caries Res. 2000;34(2):133–139. doi: 10.1159/000016580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Damle S.G., Yadav R., Garg S., Dhindsa A., Beniwal V., Loomba A., et al. Transmission of mutans streptococci in mother-child pairs. Indian J Med Res. 2016;144:264–270. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.195042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Subramaniam P., Suresh R. Streptococcus mutans strains in mother-child pairs of children with early childhood caries. J Clin Pedia Dent. 2019;43(4):252–256. doi: 10.17796/1053-4625-43.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Childers N.K., Momeni S.S., Whiddon J., Cheon K., Cutter G.R., Wiener H.W., et al. Association between early childhood caries and colonization with streptococcus mutans genotypes from mothers. Pedia Dent. 2017;39(2):130–135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lapirattanakul J., Nakano K., Nomura R., Hamada S., Nakagawa I., Ooshima T. Demonstration of mother-to-child transmission of streptococcus mutans using multilocus sequence typing. Caries Res. 2008;42(6):466–474. doi: 10.1159/000170588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.da Silva Bastos Vde A., Freitas-Fernandes L.B., Fidalgo T.K., Martins C., Mattos C.T., de Souza I.P., et al. Mother-to-child transmission of Streptococcus mutans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent. 2015;43(2):181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Berkowitz R. Acquisition and Transmission of Mutans Streptococci. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2003;31:135–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lynch D.J., Villhauer A.L., Warren J.J., Marshall T.A., Dawson D.V., Blanchette D.R., et al. Genotypic characterization of initial acquisition of Streptococcus mutans in American Indian children. J Oral Microbiol. 2015;7:27182. doi: 10.3402/jom.v7.27182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Klein M.N., Florio F.M., Pereira A.C., Hofling J.F., Goncalves R.B. Longitudinal study of transmission, diversity, and stability of Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus genotypes in Brazilian nursery children. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(10):4620–4626. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4620-4626.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Virtanen J.I., Vehkalahti K.I., Vehkalahti M.M. Oral health behaviors and bacterial transmission from mother to child: an explorative study. BMC Oral Health. 2015:15. doi: 10.1186/s12903-015-0051-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rêgo R.O., Spolidorio D.M., Salvador S.L., Cirelli J.A. Transmission of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans between Brazilian women with severe chronic periodontitis and their children. Braz Dent J. 2007;18(3):220–224. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402007000300008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]