Importance:

Prehabilitation has potential for improving surgical outcomes as shown in previous randomized controlled trials. However, a marked efficacy-effectiveness gap is limiting its scalability. Comprehensive analyses of deployment of the intervention in real-life scenarios are required.

Objective:

To assess health outcomes and cost of prehabilitation.

Design:

Prospective cohort study with a control group built using propensity score–matching techniques.

Setting:

Prehabilitation Unit in a tertiary-care university hospital.

Participants:

Candidates for major digestive, cardiac, thoracic, gynecologic, or urologic surgeries.

Intervention:

Prehabilitation program, including supervised exercise training, promotion of physical activity, nutritional optimization, and psychological support.

Main Outcomes and Measures:

The comprehensive complication index, hospital and intensive care unit length of stay, and hospital costs per patient until 30 days after surgery. Patients were classified by the degree of program completion and level of surgical aggression for sensitivity analysis.

Results:

The analysis of the entire study group did not show differences in study outcomes between prehabilitation and control groups (n=328 each). The per-protocol analysis, including only patients completing the program (n=112, 34%), showed a reduction in mean hospital stay [9.9 (7.2) vs 12.8 (12.4) days; P=0.035]. Completers undergoing highly aggressive surgeries (n=60) additionally showed reduction in mean intensive care unit stay [2.3 (2.7) vs 3.8 (4.2) days; P=0.021] and generated mean cost savings per patient of €3092 (32% cost reduction) (P=0.007). Five priority areas for action to enhance service efficiencies were identified.

Conclusions and Relevance:

The study indicates a low rate of completion of the intervention and identifies priority areas for re-design of service delivery to enhance the effectiveness of prehabilitation.

Keywords: costs, exercise training, nutrition, physical activity, prehabilitation, psychological support

Postoperative morbimortality and slow recovery after surgery generate a major health burden,1,2 partly explained by population aging and multimorbidity. The 2 factors are increasing the proportion of frail patients facing surgeries at higher risk for postoperative complications.3–6 Therefore, implementation of preventive preoperative interventions constitutes a relevant unmet need.

Personalized multimodal prehabilitation aims to optimize physical and psychological resilience to cope with the stress generated by major surgical procedures. It implies a patient-centered preoperative process encompassing the following core actions: (i) enhance management of multimorbid conditions; (ii) address unhealthy habits; and (iii) optimize physiological (physical exercise and nutrition) and psychological status.

Over the last years, increasing evidence on efficacy and potential of prehabilitation to produce health value has been generated7–10; that is, improving patients’ outcomes while maintaining an adequate relationship with costs.11 Therefore, implementation of prehabilitation as a standard clinical practice, within the widely adopted Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) programs,12 could reasonably constitute a target milestone to achieve. However, despite the emerging recommendations from experts,13–16 there is a lack of studies assessing the implementation process and impact of prehabilitation programs in real-life scenarios.

Over the last 5 years, the Prehabilitation Unit at Hospital Clínic de Barcelona (HCB),9,10 a tertiary university hospital in Catalonia (ES), has conducted a 2-phase co-creation process17 to explore determinants of scalability of prehabilitation. During the first phase, until end-December 2019, main achievements were organization of the hospital-based service, and assessment of the activity of the Prehabilitation Unit following the evaluation framework described in the study by Baltaxe et al.18 The activities undertaken during the last 2 years, starting at January 2020, had a 3-fold objective: achievement of maturity of digital support,19 assessment of financial sustainability and transferability analysis.

The current study consists of a real-world data analysis of the activity carried out in the Prehabilitation Unit during a 30-month period, from mid-2017 to end-2019, on patients undergoing major surgeries in different specialties, namely: digestive, cardiac, thoracic, urologic and gynecologic.18 The research had a 2-fold objective: (i) assessment of effectiveness and costs of prehabilitation in a real-life setting; and (ii) generation of recommendations for scalability of the service.

METHODS

Study Design

The current manuscript reports a prospective cohort study conceived to evaluate the deployment of prehabilitation as mainstream service at HCB from June 2017 to December 2019.18 The Ethics Committee for Medical Research of HCB approved the study (HCB/2016/0883). The informed consent was understood, accepted, and signed by all subjects included in the trial. The study protocol is registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02976064).

We built a contemporaneous control group of patients using propensity score–matching techniques20 taking into account the following matching variables: (i) age; (ii) sex; (iii) American Society of Anesthesiologists risk scale21; (iv) type of surgery; (v) number of drugs; (vi) individual healthcare expenses across healthcare tiers over the year previous to study enrollment; and, (vii) multimorbidity and complexity evaluated by the adjusted morbidity groups population-based morbidity index.22

The matching parameters were tuned according to overall performance on covariate balancing, assessed by the Mahalanobis distance,23 Rubin’s B (the absolute standardized difference of the means of the linear index of the propensity score in the intervention and control groups) and Rubin’s R (the ratio of intervention to control variances of the propensity score index) metrics.24 Quality of comparability between intervention and control groups after propensity score matching was considered acceptable if Rubin’s B was <25 and Rubin’s R was between 0.5 and 2.24

Patients enrolled in prehabilitation fulfilled the following criteria: (i) candidate to major digestive, cardiac, thoracic, gynecologic, or urologic surgery; (ii) high risk for postoperative complications defined by age above 70 and/or American Society of Anesthesiologists risk scale 3 to 421 and/or patients suffering from severe deconditioning caused by cancer and/or undergoing highly aggressive surgeries; and (iii) preoperative schedule allowing for at least 4 weeks of prehabilitation without unnecessary delays of the surgical program. Exclusion criteria were: (i) nonelective surgery; and (ii) no possibility or willingness to attend the appointments.

It is important to note that all surgeries that were included in this study are considered as grade III (highly invasive procedures) based on “modified Johns Hopkins criteria.”25 However, there are very different grades of surgical severity among them so, based on our own experience and taking into account some criteria such as potential blood loss, usual postoperative in-hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) stay, open or minimally surgical approach, we decided to differentiate 3 levels of aggression (high, intermediate, and low surgical aggression) within grade III surgeries (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Groups

| Prehabilitation (n=328) | Matched Controls (n=328) | P | Training-based Prehabilitation (n=189) | Matched Controls (n=189) | P | Physical Activity–based Prehabilitation Intro (n=139) | Matched Controls (n=139) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [median (P25–P75)] (y) | 71 (63–77) | 71 (63–77) | 0.797 | 71 (63–76) | 71 (64–76) | 0.809 | 72 (63–78) | 70 (62–79) | 0.521 |

| Sex: male [n (%)] | 225 (69) | 230 (70) | 0.672 | 139 (74) | 133 (70) | 0.492 | 91 (66) | 92 (66) | 0.899 |

| ASA index [n (%)] | 0.217 | 0.519 | 0.123 | ||||||

| ASA 1 | 3 (1) | 5 (2) | 2 (1) | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |||

| ASA 2 | 150 (45) | 165 (51) | 78 (41) | 77 (41) | 72 (52) | 88 (63) | |||

| ASA 3 | 154 (47) | 127 (39) | 97 (51) | 87 (46) | 57 (41) | 40 (29) | |||

| ASA 4 | 24 (7) | 30 (9) | 15 (8) | 19 (10) | 9 (7) | 11 (8) | |||

| GMA score | 23 (13) | 24 (13) | 0.829 | 23 (13) | 25 (14) | 0.337 | 24 (13) | 22 (13) | 0.423 |

| Previous year healthcare expenses (Euros 2019) | 7479 (6750) | 6997 (7659) | 0.393 | 7352 (5791) | 6985 (7982) | 0.608 | 7650 (7888) | 7012 (7225) | 0.483 |

| No. drugs | 11 (6) | 10 (6) | 0.750 | 11 (6) | 11 (6) | 0.701 | 10 (6) | 10 (6) | 0.345 |

| Level of surgical aggression* [n (%)] | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| High surgical aggression | 191 (58) | 191 (58) | 104 (55) | 104 (55) | 87 (63) | 87 (63) | |||

| Intermediate surgical aggression | 72 (22) | 72 (22) | 50 (26) | 50 (26) | 22 (16) | 22 (16) | |||

| Low surgical aggression | 65 (20) | 65 (20) | 35 (19) | 35 (19) | 30 (21) | 30 (21) | |||

Data presented as mean (SD), unless otherwise indicated.

Detailed description of the subsets of patients can be found in Tables 1S and 2S (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/E177).

Detailed information on prehabilitation-induced effects are provided in Tables 3S and 4S (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/E177).

Surgeries have been stratified by level of surgical aggression: (i) high surgical aggression: total esophagectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, total gastrectomy, open cardiac surgery, oncologic gynecologic surgery, radical cistectomy; open bilobectomy or pneumonectomy, colorectal cytoreductive surgery (CRS) with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC); (ii) intermediate surgical aggression: gastric bypass, total colectomy, rectal resection, major liver resection, pancreas resection, open prostatectomy, open partial lung resection (thoracotomy); (iii) low surgical aggression: partial gastrectomy, sleeve gastrectomy, segmental colon resection, minor liver resection, minor lung resection (videothoracoscopy).

ASA indicates American Society of Anesthesiologists risk score; GMA, adjusted morbidity groups.

Interventions

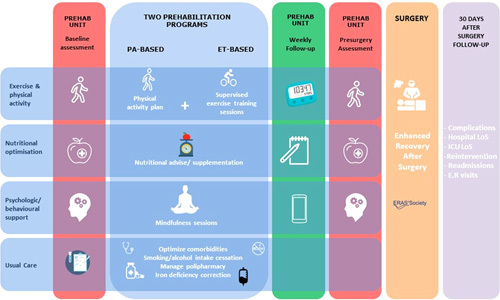

Figure 1 depicts patients’ workflow during the study period, from baseline assessment until 30 days after the surgical intervention, for both intervention and control groups:

FIGURE 1.

Patients’ workflow: ET-based and PA-based programs. After a first baseline assessment, patients were assigned either to the program promoting physical activity (PA-based) or to the intervention additionally scheduling hospital-based supervised exercise training sessions twice or 3 times per week (ET-based). Subsequently, all candidates of the intervention group attended weekly face-to-face sessions during the prehabilitation program. A postintervention evaluation was scheduled before surgery and a final assessment of all cases was done at 30 days after surgery. The care in the control group (usual care) is displayed at the bottom of the figure. ER indicates emergency room.

Prehabilitation Program

Apart from enhanced management of multimorbidity and prevention of unhealthy habits, the multimodal prehabilitation program, partly supported with a digital health platform includes: (i) motivational interviewing; (ii) a physical activity promotion plan; (iii) hospital-based supervised exercise training sessions 2 to 3 times a week; (iv) nutritional optimization; and (v) psychological support. The entire program was conducted by a multidisciplinary team including anesthesiologists, physiotherapists, dietitians, psychologists, and nurses. Patients’ diaries and/or activity trackers and a dedicated mobile application were provided to facilitate program adherence and weekly follow-up of program objectives.

As indicated in Figure 1, 2 modalities of prehabilitation program were offered: Physical activity (PA)-based, including all the elements indicated above, without supervised training sessions; and Exercise training (ET)-based that additionally included hospital-based supervised exercise training sessions. The latter, ET-based program, was prioritized for patients with relevant comorbidities associated with physical deconditioning (patient-related risk factors) and/or undergoing highly aggressive surgeries (surgery-related risk factors). Patients who could not attend to the sessions scheduled in the ET-based program due to logistical problems (ie, patients living far away from the hospital or unavailability of an accompanying caregiver) were referred to the PA-based program. PA goals for this group were adjusted on a weekly basis.

Figure 1 indicates, from left to right, the temporal events followed by candidates to the intervention group: (i) baseline evaluation; (ii) assignment to 1 of the 2 prehabilitation programs (PA-based or ET-based); (iii) weekly follow-up of the program; (iv) postprehabilitation evaluation; (v) surgical intervention; and, (vi) final assessment at 30 days after surgery. A detailed version of the interventions can be found in the Supplementary Material (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/E177).

Usual Care

Consisted of physical activity recommendation, nutritional counseling, and advice on smoking and alcohol intake cessation. Moreover, patients suffering from iron deficiency anemia received intravenous iron and in those at high risk of malnutrition [Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST)≥2]26 a nutritional intervention was done by a registered dietician (Fig. 1, bottom).

Study Variables

Main study outcome variables for the prehabilitation and control groups were blindly assessed. They included the comprehensive complication index (CCI),27 hospital and ICU length of stay (LoS), surgical reinterventions, hospital readmissions, and emergency room visits at 30 days after the intervention. In addition, preoperative functional capacity and mood change from baseline to immediately before surgery were measured in the prehabilitation group using (i) 6-minute walk test28; (ii) sit-to-stand test29; (iii) hand-grip strength; (iv) Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale30; and (v) Yale Physical Activity Survey (YPAS).31

A cost-consequence analysis (CCA) of the service was carried out. Total individual costs were prospectively obtained for each group from the hospital perspective, so, the CCA was restricted to direct healthcare costs. Hospital patient-level data were collected to analyze the impact of the program on hospital care costs. A combination of diagnostic-related groups–based costs and microcosting was used to identify and measure cost allocation. The implementation strategy, and the co-creation process, during the study period has been reported in detail in the study by Baltaxe et al.17

Data Analysis

Health outcomes and cost analysis were assessed for the entire study group (intention-to-treat analysis). Moreover, a per-protocol analysis was conducted including only those patients completing the program (ie, completers). Program completion was defined as a minimum duration of 4 weeks of prehabilitation and at least 80% of attendance to the weekly follow-up sessions or exercise training sessions for PA-based and ET-based prehabilitation patients, respectively. We also analyzed the impact of prehabilitation on health outcomes for the level of surgical aggression.

The costs of the prehabilitation program and hospital costs up to 30 days after surgery were calculated, as described in detail in the Supplementary Material (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/E177). Moreover, we assessed the impact of program adherence and level of surgical aggression on hospital costs per patient by the generation of different simulation approaches.

We computed the difference on the average cost per patient between groups in a reduced set of 200 patients (100 patients from the prehabilitation group and their 100 paired controls) using a 10,000 estimates bootstrap sampling approach. In each iteration we increased gradually, from 0 to 1, the probability of sampling individuals that meet the modeled conditions: (1) completers; (2) patients undergoing highly aggressive surgeries; and (3) completers undergoing highly aggressive surgeries. Afterwards, we calculated Pearson correlation coefficients to measure the association among the costs and the 3 modeled parameters. Finally, we created Linear models to estimate the potential savings generated by increasing either the rate of completers or the rate of patients undergoing highly aggressive surgeries, and the interaction of both factors.

Data are presented as mean (SD), median (P25–P75), or n (%) as indicated. Comparisons were done using Student t tests, nonparametric tests and χ2 or Fisher exact tests for numerical (Gaussian or non-Gaussian distributions) and categorical variables, respectively. Comparisons between groups for the CCA were done using the Fisher-Pitman permutation test. Data analyses were conducted using R, version 3.6.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The significance threshold was set at P value<0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 355 patients were included in the prehabilitation program. Twenty-seven out of them did not eventually undergo surgery and were excluded from all analyses. Finally, 328 prehabilitation patients were included in the study. Main baseline characteristics of patients and their matched controls are showed in Table 1. It is of note that 189 patients (58%) were allocated into the ET-based program, whereas 139 individuals (42%) were included into the PA-based modality. By design, patients undergoing the PA-based program were less severe in terms of frailty and multimorbidity. From the overall sample of patients, 20% of them required protein supplementation and 60% participated in the mindfulness sessions in addition to availability for App-based practices at home.

The duration of the intervention for the entire study group, excluding cardiac surgeries, showed a median of 39 (24–54) days. Cardiac surgery patients underwent a lengthier prehabilitation intervention, lasting 64 (49–81) days. From the entire study group, 112 patients (34%) were considered completers. No baseline differences in matching variables were found between completers and either the entire study group or the subset of noncompleters.

Effects of Prehabilitation on Exercise Performance and Physical Activity Before Surgery

Prehabilitation increased exercise performance (sit-to-stand test, Δ2.3 repetitions; P=0.001) and daily physical activity (YPAS, Δ12 points; P=0.018) in the PA-based program (Table 3S, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/E177). Similar effects were observed in the ET-based program (6-minute walk test, Δ13 m; P=0.004; and, YPAS Δ20 points; P<0.001) (Table 4S, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/E177). The impact of prehabilitation on exercise performance and on daily physical activity was similar between the entire study group, the subset of patients identified as completers (n=112; 40 PA-based and 72 ET-based prehabilitation) and those undergoing highly aggressive surgical procedures (n=60; 21 PA-based and 39 ET-based prehabilitation). None of the other tests showed changes after prehabilitation.

Health Outcomes and Value Generation

Impact on Postoperative Outcomes

The entire study group (n=328), intention-to-treat analysis, did not show significant differences in the CCI, hospital and/or ICU LoS, or use of healthcare resources at 30 days compared with the control group (Tables 5S–7S, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/E177). However, patients identified as completers (n=112), per-protocol analysis, showed a significant reduction in-hospital LoS [9.9 (7.2) vs 12.8 (12.4) days; P=0.035] (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Health Outcomes and Use of Healthcare Resources in Completers

| Prehabilitation Completers (N=112) | Matched Controls (N=112) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive complications index (score) | 15.5 (16.7) | 16.4 (19.0) | 0.725 |

| Hospital LoS (d) | 9.9 (7.2) | 12.8 (12.4) | 0.035 |

| ICU LoS (d) | 1.7 (2.5) | 2.3 (3.6) | 0.105 |

| 30-d surgical reinterventions [n (%)] | 4 (4) | 7 (6) | 0.354 |

| 30-d hospital readmissions [n (%)] | 18 (16) | 14 (13) | 0.445 |

| 30-d emergency room visits [n (%)] | 37 (33) | 32 (29) | 0.469 |

Data presented as mean (SD), unless otherwise indicated.

Detailed results are depicted in Tables 5S to 8bS (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/E177).

Likewise, the sensitivity analysis, including only completers undergoing highly aggressive surgeries (n=60), additionally showed a reduction of both hospital and ICU LoS [hospital LoS: 11.0 (5.4) vs 16.7 (13.1) days; P=0.002 and ICU LoS: 2.3 (2.7) vs 3.8 (4.2) days; P=0.021] (Table 3), as well as a trend to CCI reduction (1715 vs 2321; P=0.083).

TABLE 3.

Health Outcomes and Use of Healthcare Resources in Completers Undergoing Highly Aggressive Surgeries

| Prehabilitation Completers Undergoing Highly Aggressive Surgeries (N=60) | Matched Controls Intro (N=60) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive complications index (score) | 17 (15) | 23 (21) | 0.083 |

| Hospital LoS (d) | 11.0 (5.4) | 16.7 (13.1) | 0.002 |

| ICU LoS (d) | 2.3 (2.7) | 3.8 (4.2) | 0.021 |

| 30-d surgical reinterventions [n (%)] | 3 (5) | 5 (8) | 0.464 |

| 30-d hospital readmissions [n (%)] | 14 (23) | 10 (17) | 0.361 |

| 30-d emergency room visits [n (%)] | 27 (45) | 22 (37) | 0.353 |

Data presented as mean (SD), unless otherwise indicated.

Detailed results are depicted in Tables 5S to 8bS (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/E177).

Cost-consequence Analysis

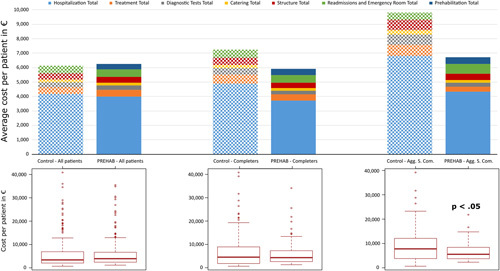

Figure 2 depicts the total hospital costs of the surgical process per patient. When analyzing the full sample of patients, we did not find a reduction of costs in the prehabilitation group (€−125 per patient; P=0.806). In contrast, completers generated a trend towards mean cost reduction of 18% (€1323 per patient; P=0.140). Moreover, completers undergoing highly aggressive surgeries showed a significant mean cost reduction of 32% (€3092 per patient; P=0.007). De-aggregated data on costs and savings are indicated in Tables 8aS and 8bS.

FIGURE 2.

Average costs per patient and cost structure of prehabilitation and matched controls for 3 groups of patients. Solid bars correspond to prehabilitation and hatched bars to controls. Prehabilitation in the entire study group (n=328) did not show cost reductions (left). Patients completing the program (n=112) (central), presented showed an 18% reduction in costs (P=0.140) with prehabilitation. The third group (right), completers undergoing highly aggressive surgical procedures (n=60) showed statistically significant cost savings, 32% (P=0.007).

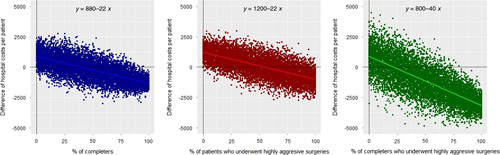

The simulations depicted in Figure 3, indicate that 2 factors: program completion (R=−0.7, P<0.001, β=−22) and highly aggressive surgeries (R=−0.7, P<0.001, β=−22) are separately associated to cost savings and both factors have a synergistic effect (R=−0.69, P<0.001, β=−40) on reductions of hospital costs per patient.

FIGURE 3.

Impact of program adherence and prehabilitation in patients undergoing highly surgical aggression on hospital costs per patient. The figure presents 3 different simulations assessing the impact of completing the program (left panel, blue), prehabilitation of patients undergoing highly aggressive surgeries (central panel, red) and completers undergoing highly aggressive surgeries (right panel, green) on hospital costs. The x axis indicates the relative frequencies of completers, prehabilitation of patients undergoing highly aggressive surgeries and completers undergoing highly aggressive surgeries in each sample, whose proportion was gradually increased from 0% to 100% in each model. The y axis indicates the difference of hospital costs per patient between prehabilitation and controls. Detailed information on costs analysis is provided in the Online Supplementary Material (Table 8bS, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/E177).

DISCUSSION

Main Study Findings

The current research assessed health outcomes and potential savings generated by the Prehabilitation Unit at HCB during a 30-month period, wherein multimodal prehabilitation was conceived, and implemented, as a preventive intervention well integrated into ERAS standard of care recommendations.12

The study was carried out as a first phase of the 5-year strategy undertaken to explore factors modulating the transition from clinical research to scalability of the intervention into a real-world setting.17 The final aim of the scalability program was to minimize the efficacy-effectiveness gap19 of the intervention. It is of note that comparisons between the current study outcomes and those reported by the same team in the context of a previous randomized controlled trial9,10 confirm such efficacy-effectiveness gap. The main lesson learnt from the current research was that the healthcare value generation of the intervention cannot be inferred from randomized controlled trials. Instead, there is a clear need for careful assessment of the deployment process in real-life settings, as well as an adequate long-term follow-up of service outcomes after adoption.

Highly relevant findings of the current research were the identification of 2 main factors associated with the effectiveness of the intervention; that is: (i) completion of the intervention; and (ii) patients undergoing highly aggressive surgical procedures. We acknowledge that the low completion rate (34%) achieved in the current study was partly explained by a rather strict threshold applied (program duration of 4 weeks and 80% attendance to the sessions). Factors determining completion are diverse, namely: (i) adherence to the program; (ii) logistic barriers (transportation, time availability, etc.); and/or, (iii) alignment of the intervention with surgical agendas.

We observed that, whereas significant benefits of prehabilitation on daily physical activity and/or exercise performance were seen in the entire study group, positive impacts of the intervention on postsurgical outcomes were only observed in program-completers and even more clearly in completers undergoing high aggression surgical procedures. This finding suggests that other factors beyond optimization of patients’ fitness may play significant roles in determining surgical outcomes. The current study does not exclude the potential benefits of prehabilitation in mediumrisk and low-risk patients because relevant outcomes like patient-reported experience and patient-reported outcomes were not evaluated.

The effects of prehabilitation on candidates to highly aggressive surgical procedures seem to indicate that further studies are needed exploring adjustment of the characteristics of the intervention to presurgical risk level. Three major blocks of determinants of preoperative patients’ risk in prehabilitation candidates are: (i) baseline multimorbidity, age, unhealthy lifestyles, and socioeconomic frailty; (ii) level of surgical aggression; and (iii) risks associated to exercise training in frail patients.

The results of the current study, combined with those generated in the study by Baltaxe and colleagues,17,19 seem to provide strong grounds to pave the way toward large-scale adoption of prehabilitation, following a population-based approach. The uniqueness of the scalability program undertaken at HCB is the combination of the current prospective cohort study design and qualitative analysis of the deployment process following well-established implementation research methodologies.17,18 It is of note that the cost of prehabilitation represented a small percentage of the total costs per patient, therefore, the financial sustainability of the service seems achievable if the intervention is adequately implemented.

Study Limitations

The continuous learning process experienced during the implementation of prehabilitation as an innovative service at HCB implies inherent inefficiencies reflected in the current study. Consequently, both completion rates and health outcomes reported in the current study may markedly underestimate the potential of the intervention. It can be reasonably assumed that achievement of service maturity in the future should contribute to the consolidation of prehabilitation as a standard of care intervention. A more comprehensive assessment of the intervention, for example using a triple/quadruple aim approach, may contribute to identify potential benefits in a broader spectrum of patients.

Although we assume that prehabilitation programs should be effective in all phases of care including posthospital recovery, home care, etc. the present study has only taken into account the direct costs of hospitalization.

Finally, the simulations created for cost analysis are based on the prehabilitation program currently in place at the HCB, so it is challenging to extrapolate the results to different prehabilitation settings.

Lessons Learnt and Recommendations for Scalability

The lessons learnt in the co-creation process reported in the study by Baltaxe et al17 are aligned with the results of current study allowing to identify 5 interlinked key challenges modulating adoption in the clinical scenario, as well as to build-up specific recommendations for successful service scalability which may require further evaluation on a multicenter basis.

Increase Rate of Completion of the Intervention

The observed low percentage of completers (34%) is limiting effectiveness of prehabilitation. Such limitation could be overcome with: (i) increase patients’ accessibility to the program through refinement of the delivery of the intervention; (ii) better alignment with surgical agendas to prevent unnecessary dropouts; and (iii) enhance patients’ engagement and self-efficacy through appropriate digital support, as well as with introduction of cognitive behavioral therapies (CBTs).32

Refinement and Standardization of Service Delivery

Since the estimated coverage of existing demand at HCB for candidates to major surgical procedures during the period was 21%, on average, additional capacity of the Prehabilitation Unit could be potentially built with a service re-design using a Lean approach.33 For example, a progressive standardization of prehabilitation pathways such that service delivery can be done by one type of health professional acting as a case manager. But, most importantly, capacity building can be achieved by partly transferring service delivery to the community.

An ongoing pilot study seem to confirm feasibility of a 3-layer service design covering low-risk, medium-risk, and high-risk candidates to surgery. Briefly, low-risk patients should receive preoperative education and remotely supported CBT. In medium-risk candidates, prehabilitation should additionally include promotion of daily-life physical activity and community-based, partly remotely supported, physical training carried out through sports. Finally, in high-risk patients, those showing higher benefits of the intervention in our study, an initial period with hospital-based face-to-face supervised high-intensity exercise training should be followed by community-based physical training. Networking and collaborative work among professionals delivering the intervention across healthcare layers should be highly encouraged to enhance safety and efficiency of the interventions.

Enhanced Risk Assessment and Personalization of Interventions

Despite current assessment strategies allow reasonable estimations of patients’ risk, there is room for improvement using multilevel predictive modeling considering as covariates: (i) multimorbidity indices such as adjusted morbidity groups,22 (ii) clinical information, (iii) patients’ self-tracking data; and (iv) biological markers.34,35

Maturity of Digital Support19

Digitally supported prehabilitation plays a key enabling role to face some of the identified. Cloud-based digital support, ensuring interoperability between different healthcare providers, constitute a key requirement. There is a clear need to broaden the current scope of digital support to prehabilitation encompassing the following facets: (i) self-monitoring data including goal setting and feedback on achievements; (ii) CBT to enhance intervention adherence and outcomes; (iii) facilitating patients’ accessibility, as well as bidirectional remote interactions with health professionals; (iv) collaborative work among professionals within and beyond healthcare tiers36; (v) decision support tools for patients and professionals; and, (vi) facilitating service management and business intelligence.

Toward a Community-based Service

The transfer of prehabilitation delivery to the community setting, involving different types of actors (ie, primary care, health clubs, etc.), is a must. A hospital-centric approach, as reported in the current study, shows several major limitations in terms of service capacity and patients’ accessibility.

It is of note that lessons learnt during the implementation of prehabilitation will likely open novel opportunities in promising nonsurgical areas like rehabilitation of chronic patients, prevention of multimorbidity, and enhancement of resilience in oncologic patients. However, specific cost-benefit analyses should be undertaken for each of these potential areas of application of the approach.

CONCLUSIONS

The current study points out that further efforts are required focusing on optimization of service delivery, as well as on identification of patients’ profiles that can benefit from the intervention. Multicenter evaluations of prehabilitation programs are clearly needed, ideally considering the potential offered by federated data analysis across centers.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the high quality work carried out the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona Prehabilitation Group: Graciela Martínez-Pallí, Marta Ubré, Raquel Risco, Manuel López-Baamonde, Antonio López, María José Arguis, Ricard Navarro-Ripoll, Mar Montané-Muntané, Marina Sisó, Raquel Sebio, Monique Messaggi-Sartor, Fernando Dana, David Capitán, Amaya Peláez Sainz-Rasines, Francisco Vega-Guedes, Beatriz Tena, Betina Campero, Bárbara Romano-Andrioni, Silvia Terés, Elena Gimeno-Santos, Eurídice Álvaro, Juan M Perdomo, and Ana Costas. They are also indebted to the following projects that contributed to support the work done during the study period: PAPRIKA EIT-Health-IBD-19365; NEXTCARE COMRDI15-1-0016; and Generalitat de Catalunya (2014SGR661); CONNECARE (H2020-689802); ISCIII-FIS-PI18/00841; ISCIII-FIS-PI17/00852.

Footnotes

Hospital Clínic de Barcelona Prehabilitation Group Collaborators: Graciela Martínez-Pallí, Marta Ubré, Raquel Risco, Manuel López-Baamonde, Antonio López, María José Arguis, Ricard Navarro-Ripoll, Mar Montané-Muntané, Marina Sisó, Raquel Sebio, Monique Messaggi-Sartor, Fernando Dana, David Capitán, Amaya Peláez Sainz-Rasines, Francisco Vega-Guedes, Beatriz Tena, Betina Campero, Bárbara Romano-Andrioni, Silvia Terés, Elena Gimeno-Santos, Eurídice Álvaro, Juan M Perdomo and Ana Costas.

Supported by JADECARE project—HP-JA-2019—Grant Agreement no. 951442 a European Union’s Health Programm 2014–2020.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.annalsofsurgery.com.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Graciela Martínez-Pallí, Marta Ubré, Raquel Risco, Manuel López-Baamonde, Antonio López, María José Arguis, Ricard Navarro-Ripoll, Mar Montané-Muntané, Marina Sisó, Raquel Sebio, Monique Messaggi-Sartor, Fernando Dana, David Capitán, Amaya Peláez Sainz-Rasines, Francisco Vega-Guedes, Beatriz Tena, Betina Campero, Bárbara Romano-Andrioni, Silvia Terés, Elena Gimeno-Santos, Eurídice Álvaro, Juan M. Perdomo, and Ana Costas

REFERENCES

- 1. Nepogodiev D, Martin J, Biccard B, et al. Global burden of postoperative death. Lancet. 2019;393:401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD, et al. An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modelling strategy based on available data. Lancet. 2008;372:139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Snowden CP, Prentis J, Jacques B, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness predicts mortality and hospital length of stay after major elective surgery in older people. Ann Surg. 2013;257:999–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sandini M, Pinotti E, Persico I, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of frailty as a predictor of morbidity and mortality after major abdominal surgery. BJS Open. 2017;1:128–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sepehri A, Beggs T, Hassan A, et al. The impact of frailty on outcomes after cardiac surgery: a systematic review. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:3110–3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burg ML, Daneshmand S. Frailty and preoperative risk assessment before radical cystectomy. Curr Opin Urol. 2019;29:216–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arthur HM, Daniels C, McKelvie R, et al. Effect of a preoperative intervention on preoperative and postoperative outcomes in low-risk patients awaiting elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:253–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barakat HM, Shahin Y, Khan JA, et al. Preoperative supervised exercise improves outcomes after elective abdominal aortic aneurism repair. Ann Surg. 2016;264:47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barberan-Garcia A, Ubre M, Roca J, et al. Personalised prehabilitation in high-risk patients undergoing elective major abdominal surgery: a randomized blinded controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2018;267:50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barberan-Garcia A, Ubre M, Pascual-Argente N, et al. Post-discharge impact and cost-consequence analysis of prehabilitation in high-risk patients undergoing major abdominal surgery: secondary results from a randomised controlled trial. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123:450–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Michael EP. Value-based health care delivery. Ann Surg. 2008;248:503–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;1:292–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levy N, Grocott MPW, Carli F. Patient optimisation before surgery: a clear and present challenge in peri-operative care. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(suppl 1):3–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gillis C, Wischmeyer PE. Pre-operative nutrition and the elective surgical patient: why, how and what? Anaesthesia. 2019;74(suppl 1):27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Levett DZH, Grimmett C. Psychological factors, prehabilitation and surgical outcomes: evidence and future directions. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(suppl 1):36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chan SP, Ip KY, Irwin MG. Peri-operative optimisation of elderly and frail patients: a narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(suppl 1):80–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baltaxe E, Cano I, Risco R, et al. on behalf of the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona Prehabilitation Group. Role of co-creation for large-scale sustainable adoption of digitally supported integrated care: prehabilitation as a use case. IJIC; 2022 (submitted). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18. Baltaxe E, Cano I, Herranz C, et al. Evaluation of integrated care services in Catalonia: population-based real-life deployment protocols. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barberan-Garcia A, Cano I, Bongers BC, et al. Digital Support to multimodal community-based prehabilitation: looking for optimization of health value generation. Front Oncol. 2021;11:1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Garrido M, Kelley A, Paris J, et al. Methods for constructing and assessing propensity scores. Health Serv Res. 2014;49:1701–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mayhew D, Mendonca V, Murthy BVS. A review of ASA physical status—historical perspectives and modern developments. Anaesthesia. 2019;74:373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dueñas-Espin I, Vela E, Pauws S, et al. Proposals for enhanced health risk assessment and stratification in an integrated care scenario. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mahalanobis Distance. The Concise Encyclopedia of Statistics. New York, NY: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rubin DB. Using propensity scores to help design observational studies: application to the tobacco litigation. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2001;2:169–188. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Donati A, Ruzzi M, Adrario E, et al. A new and feasible model for predicting operative risk. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93:393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Malnutrition Advisory Group. A Standing Committee of BAPEN. Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool; 2003. https://www.bapen.org.uk/pdfs/must/must_full.pdf .

- 27. Slankamenac K, Graf R, Barkun J, et al. The comprehensive complication index: a novel continuous scale to measure surgical morbidity. Ann Surg. 2013;258:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holland A, Spruit M, Troosters T, et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical standard: field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:1428–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Strassmann A, Steurer-Stey C, Lana KD, et al. Population-based reference values for the 1-min sit-to-stand test. Int J Public Health. 2013;58:949–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Donaire-Gonzalez D, Gimeno-Santos, Serra I, et al. Validation of the Yale Physical Activity Survey in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Arch Bronconeumol. 2011;47:552–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Duff OM, Walsh D, Furlong BA, et al. Behavior change techniques in physical activity ehealth interventions for people with cardiovascular disease: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19:e281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chokshi SK, Mann DM. Innovating from within: a process model for user-centered digital development in academic medical centers. JMIR Hum Factors. 2018;5:e11048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Calvo M, Gonzalez R, Seijas N, et al. Health outcomes from home hospitalization: multi-source predictive modelling. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e21367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roca J, Tenyi A, Cano I. Wolkenhauer O. Digital. health for enhanced understanding and management of chronic conditions: COPD as a use case. Systems Medicine: Integrative, Qualitative and Computational Approaches, Volume 1. Oxford, UK: Elsevier. 256–273. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cano I, Alonso A, Hernandez C, et al. An adaptive case management system to support integrated care services: lessons learned from the NEXES project. J Biomed Inform. 2015;55:11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]