Abstract

Diabetes mellitus (DM) has been shown to be a clinical risk factor for bone diseases including osteoporosis and fragility. Bone metabolism is a complicated process that requires coordinated differentiation and proliferation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs). Owing to the regenerative properties, BMSCs have laid a robust foundation for their clinical application in various diseases. However, mounting evidence indicates that the osteogenic capability of BMSCs is impaired under high glucose conditions, which is responsible for diabetic bone diseases and greatly reduces the therapeutic efficiency of BMSCs. With the rapidly increasing incidence of DM, a better understanding of the impacts of hyperglycemia on BMSCs osteogenesis and the underlying mechanisms is needed. In this review, we aim to summarize the current knowledge of the osteogenesis of BMSCs in hyperglycemia, the underlying mechanisms, and the strategies to rescue the impaired BMSCs osteogenesis.

Keywords: bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell, osteogenesis, hyperglycemia, diabetes mellitus, Reactive Oxygen Species

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a metabolic disease characterized by hyperglycemia (1). Prolonged exposure to hyperglycemia results in a range of chronic complications, including cardiovascular diseases, chronic kidney diseases, nerve damage, and bone diseases, thereby greatly compromising individuals’ quality of life (2–5). The number of people suffering from DM was 537 million in 2021 and was projected to reach 643 million by 2030 (6). Currently, DM is one of the leading causes of death worldwide and has become a public concern of global health (7).

The skeletal complications caused by DM are well-documented. The skeletal fragility and risk of bone fractures increase in patients with DM (8, 9). Long-term exposure to hyperglycemia jeopardizes the healing of bone fractures (10). In addition, DM patients are predisposed to a higher risk of periodontitis and peri-implantitis (11–14). The molecular modulation of bone metabolism in high glucose (HG) conditions has been widely investigated. Massive evidence indicates that the osteogenic ability of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) is inhibited under HG conditions, which contributes to reduced bone turnover and impaired bone quality in DM patients (9). With the increasing incidence of DM and the resultant socioeconomic burden, it is of great significance to obtain a better understating regarding the impacts of the HG environment on BMSCs osteogenesis and the underlying mechanisms. Therefore, the aim of this review is to summarize and discuss the current knowledge about BMSCs osteogenesis under HG conditions and provide new insights into future research and clinical management of DM.

2. Osteogenesis of BMSCs

BMSCs are a type of multipotent progenitors in bone marrow, which can differentiate into osteogenic, adipogenic, myogenic, and chondrogenic lineages to support tissue homeostasis, repair, and regeneration (15, 16). The osteogenesis of BMSCs is vital for bone growth, fracture healing, and osseointegration (17, 18). To achieve osteoblastic function, BMSCs need to move from bone marrow niche to target tissues through blood circulation (19–22). The homing and migration of BMSCs is a complex process governed primarily by chemical factors including chemokines (23, 24), cytokines (25–27), and growth factors (28–33), as well as mechanical factors including mechanical strain (34, 35), shear stress (36), matrix stiffness (37), and microgravity (38).

Upon being recruited to the site where bone formation is required, the osteogenic commitment and differentiation of BMSCs which are delicately orchestrated by multiple intracellular signaling pathways and extracellular environment are of utmost importance to osteogenic activity (39). The early regulators of osteogenic commitment of BMSCs include Wnt/β-catenin signaling, bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), hedgehog proteins, and endocrine hormones (40, 41). After that, runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) and Osterix 1 (Osx1) are crucial to shifting the gene expression of BMSCs to osteogenic genes that are responsible for type I collagen-based extracellular matrix deposition (42). Then, the BMSCs committed to osteogenic lineage gradually present the gene expression profile and morphological features of osteoblasts and later osteocytes, expressing osteoprotegerin (OPG), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), type I collagen, and osteocalcin (43). The osteoblasts and osteocytes can synthesize and secrete osteoid and mineralization factors to produce bone tissue, which couples with the osteoclastic activity, thus achieving bone modeling and remodeling to adapt to the metabolic and structural needs (44–46).

3. Impaired BMSCs osteogenesis under HG conditions

As stated, BMSCs osteogenesis, in a broad sense, is a complex process including migration, proliferation, osteogenic differentiation, etc. Plethora of research have suggested that HG conditions have comprehensive impacts on BMSCs osteogenesis. The most studied process implicated in the impaired BMSCs osteogenesis under HG conditions will be discussed in the following subsections, from the perspective of migration, proliferation, senescence, apoptosis, and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs.

3.1. Migration of BMSCs

Although the mechanisms involved are incompletely understood, current evidence demonstrates the migration of BMSCs is mainly regulated by a series of cytokines and chemokines such as stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) and CXC ligand 12 (CXCL12) (47, 48). Exposure to a hyperglycemic environment can alter the expression of related agents, thus modulating the migration of BMSCs. For example, HG conditions inhibited the migration and proliferation of BMSCs by reducing the expression of CXC receptor 4 (CXCR-4) via activating glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β) (49). Besides, the expression of integrin subunit alpha 10 (ITGA10) in BMSCs was down-regulated in the HG environment, which suppressed the migration and adhesion of BMSCs via FAK/PI3K/AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin pathway (50).

3.2. Proliferation of BMSCs

Proliferation of BMSCs is essential for bone growth and formation. However, the impaired proliferation and the consequent deficiency of BMSCs can significantly delay fracture healing and reduce the efficacy of regenerative therapy (51–54). The consensus on the inhibited BMSCs proliferation under HG conditions has been reached by previous studies. The decreased proliferative ability under HG conditions has also been reported in the MSCs derived from adipose tissue (55), gestational tissue (umbilical cord, placenta, and chorion) (56), and periodontal ligament tissue (57). Intriguingly, it has been reported that the HG treatment lower than 25 mM promoted the proliferation of BMSCs while the HG treatment of 35 mM displayed an inhibitory effect (58). The perplexing findings emphasize the significance to standardize the simulation of hyperglycemic settings in vitro. The glucose concentrations and HG treatment duration of the studies regarding BMSCs proliferation were summarized in Table 1 , which showed substantial heterogeneity. Thus, it is of great significance to determine the appropriate HG treatment to diminish the heterogeneity of in vitro studies, and hopefully, provide more reliable evidence.

Table 1.

Main information of the studies regarding BMSCs proliferation.

| Authors, Year | Results | HG treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Xing Q et al., 2021 (59) |

HG significantly decreased BMSCs proliferation compared with that of any of the other groups at each indicated time point. | 25 mM for 24h, 48h and 72h |

| Zhang B et al., 2016 (49) |

From days 3 to 7, proliferation was reduced in the presence of 16.5 mM compared with that at 5.5 mM. | 16.5 mM for 7d |

| Gu Z et al., 2013 (60) |

The ability of the BMSCs to proliferate was significantly reduced. | Not clear |

| Kim YS et al., 2013 (61) |

In 7 days, the proliferation rate had significantly decreased and had been restored by oxytocin. | Higher than 250 mg/dl |

| Zhao YF et al., 2013 (62) | Proliferation of the diabetic BMSCs proceeded slower than the normal BMSCs at days 3, 5 and 7. | Higher than 16.7 mmol/l |

| Stolzing A et al., 2012 (63) |

The formation of BMSC colonies was reduced. | 25mmol/L for 2 weeks |

| Ezquer F et al., 2011 (64) |

Although viable BMSCs were less abundant in diabetic bone marrow, they exhibited the same proliferation potential. | Higher than 400 mg/dl for more than 2 months |

| Jin, P et al., 2010 (65) |

Proliferative abilities at day 3, 5 and 7 were lower. | Higher than 16.7 mmol/l |

| Stolzing A et al., 2010 (66) |

While the sizes of the colonies were smaller, CFU numbers increased in 4-week diabetic rats but declined in 12-week ones. | Not clear |

| Gopalakrishnan V et al., 2006 (67) |

Proliferation of BMSCs was decreased. | 16.5 and 49.4 mmol/L for 3, 7, and 28 days |

3.3. Senescence of BMSCs

Senescence is a cellular response featured with a stable cell cycle arrest that limits the potential of cell proliferation (68, 69). The senescent MSCs are characterized by decreased stemness, cell phenotype changes, immunomodulatory property damage, impaired proliferative ability, and higher susceptibility to apoptosis, which highly restricts their therapeutic value (70). Evidence have shown that hyperglycemic settings alter MSCs’ characteristics and functions, resulting in the senescence of MSCs (70, 71). The increased oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS) could be a main cause of senescence of BMSCs under HG conditions (72). BMSCs displayed a greater rate of senescence owing to the facilitated autophagy mediated by ROS in hyperglycemic environment (73). Mechanistically, HG induces ROS generation in BMSCs primarily through the activation of NADPH oxidase, while the generated ROS activates autophagy and upregulates the expression of aging markers (73). The relationship between TNF-α and stem cell senescence under HG conditions has also been noticed. TNF-α expression is elevated in obese and diabetic individuals (74, 75), while the addition of TNF-α significantly increased cellular senescence of stem cells (76). Therefore, inhibiting ROS or TNF-α production to relieve BMSCs senescence seems to be a plausible strategy for the treatment of bone complications induced by DM.

3.4. Apoptosis of BMSCs

Currently, most studies agree that the HG conditions promote the apoptosis of BMSCs. The molecular modulation of HG-induced apoptosis is complex. First, an excess of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) that refer to a family of compounds formed by non-enzymatic reactions between carbohydrates and proteins, lipids, or nucleic acids can be produced under HG conditions (77, 78). AGEs can bind to their multiple receptors (RAGEs) on BMSCs and elicit apoptosis via activating caspases through TNF-α production, p38 AMPK pathway, and oxidative stress (79). It has been shown that it is AGEs rather than HG conditions per se decrease the proliferation and increase the apoptosis of BMSCs via producing ROS and selective reduction of superoxide dismutase (SOD)-1 and SOD-3 (80). Besides, it should be noted that the up-regulation of RAGEs expression in BMSCs by HG conditions can amplify the pro-apoptotic effect of AGEs (81). Second, the increased ROS production and the resultant oxidative stress in BMSCs are prominent contributors to HG-induced apoptosis. The HG-induced ROS overproduction can be attributed to mitochondrial dysfunction (82–84) and the pathologic activation of the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway (79, 85). ROS overproduction results in high levels of free radicals, which further cause DNA damage and trigger apoptosis via activating the p53 pathway (86). In addition, the high levels of ROS under HG conditions enhance the expression of apoptotic proteins and inhibit anti-apoptotic proteins via regulating AKT signaling pathways, thus leading to apoptosis (87). Third, autophagy is involved in the HG-mediated apoptosis of BMSCs. Autophagy is a necessary process for the homeostasis and stemness of BMSCs. The activation of protective autophagy has been suggested to ameliorate hypoxia-induced pancreatic β cell apoptosis and senescence (88). Similarly, enhanced autophagy has been found to inhibit the apoptosis of BMSCs in a hyperglycemic setting (73). Moreover, the HG-induced apoptosis of BMSCs can be partially reversed by enhancing AMPK/mTOR pathway-mediated autophagy (89). Although the regulatory effects of autophagy on apoptosis of stem cells derived from other sources remain controversial (90–92), it is conceivable to reach a preliminary conclusion that enhanced autophagy protects BMSCs away from HG-induced apoptosis.

The reciprocal interaction between ROS, AGEs, and autophagy in the regulation of HG-induced BMSCs apoptosis have received increasing concern. It is believed that ROS acts as the master regulator. The ROS and oxidative stress which are induced and maintained by the HG environment result in the exacerbated formation of AGEs (93). The AGEs not only elicit the apoptosis of BMSCs but also further elevates the ROS levels, thus forming a vicious cycle and amplifying the apoptotic effect (79). In contrast, the excessive ROS in BSMCs activates autophagy through transcriptional and posttranslational mechanisms, whereas autophagy is thought to degrade impaired organelles and proteins to reduce the intracellular ROS (94, 95), thus keeping BMSCs away from the ROS-induced apoptosis under HG conditions. Overall, although the detailed molecular process remains enigmatic, the role of ROS, AGEs, and autophagy in HG-mediated BMSCs abnormality have been recognized. Future studies are still needed to decipher the detailed mechanisms.

3.5. Osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs

The most prominent feature of BMSCs is multipotency. BMSCs can differentiate into adipocytes and osteoblasts depending on the prevailing signaling molecules (16, 96). High glucose environments can induce alterations in the expression levels of various signaling molecules, which impact the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs through signal transduction, gene expression, as well as immune regulation. The most widely studied mechanisms that underlie HG-mediated BMSCs osteogenesis include ROS overproduction (97, 98), AGEs-RAGEs signaling axis (99), and immunomodulation (100, 101). etc. Considering that the regulatory effects of ROS and AGEs have been discussed above, in this part we will focus on the signal transduction, gene expression, and immune regulation of BMSCs in hyperglycemia.

3.5.1. Signal transduction

3.5.1.1. Wnt pathways

Wnt signaling plays a central regulatory role in the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs (102–105). HG conditions exert comprehensive disturbance to Wnt pathways, from the upstream regulator to the downstream core molecule. Wnt10b is critical to maintaining trabecular bone thickness and bone mineral density (106, 107), and the suppression of Wnt10b facilitated adipogenesis (108, 109). Whereas, the Wnt10b concentration in blood samples of DM patients was greatly lower than that of healthy individuals, and activating Wnt10b effectively reversed HG-induced osteogenic inhibition in BMSCs (110). Moreover, hyperglycemia has been reported to selectively enhance autogenous Wnt11 expression in BMSCs to stimulate adipogenesis through Wnt/protein kinase C pathway (109). Besides, HG conditions have been shown to activate GSK-3β, which compromised β-catenin stabilization and had negative effects on BMSCs osteogenesis (111, 112). Histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1), a widely recognized inhibitor of β-catenin (113), has been found to be up-regulated under HG conditions, thus inhibiting the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs (114). Additionally, hyperglycemia has been shown to increase sclerostin production, which induced adipogenesis of BMSCs by inhibiting Wnt signaling (115).

The regulation of miRNAs in BMSCs osteogenesis under HG conditions has been recognized in the past decade. It has been found that the HG-induced reduction of miR-124-3p expression greatly activated GSK-3β expression, thereby causing decreased osteogenesis in BMSCs (116). Furthermore, HG conditions upregulated the expression of miR-214-3p, which inhibited the osteogenesis of BMSCs by suppressing Wnt signaling via targeting β-catenin directly (117). Likewise, HG-induced upregulation of miR-493-5p inhibited ZEB2, thus preventing the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin and the subsequent osteogenesis of BMSCs (118). More basic research is needed to elucidate the mechanisms regarding the regulatory of HG conditions on miRNA expression and the precise roles of miRNAs in HG-induced inhibited BMSCs osteogenesis.

3.5.1.2. PPARs pathways

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are nuclear receptors that serve as transcription factors upon ligand activation and are implicated in numerous biological processes (119–121). Three known PPAR isotypes have been identified in mammals, termed PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ (122).

The ties between PPARγ and Wnt signaling in BMSCs osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation have been widely investigated (123, 124). PPARγ is known to act as the master transcriptional regulator of adipogenic differentiation of BMSCs at the expense of repressed osteogenic differentiation (125, 126). It has been proven that the up-regulated expression of PPARγ in diabetic mice correlates with increased bone adiposity and impaired bone quality (127). Exposure to hyperglycemia has been shown to induce the adipogenic differentiation of BMSCs via the PI3K/AKT-regulated PPARγ pathway both in vitro and in vivo (128). In short, the increased PPARγ expression shifts BMSCs toward adipogenic lineage and reduces the osteogenic capability under HG conditions. The regulatory effects of PPARβ/δ on bone turnover were first recognized in 2013 (129). The activation of PPARβ/δ amplified Wnt-dependent and β-catenin-dependent osteogenesis, and the knockout of PPARβ/δ impaired bone remineralization and bone mass (129, 130). The involvement of PPARβ/δ in the BMSCs osteogenesis under HG conditions has been identified recently. PPARβ/δ has been found to be down-regulated in BMSCs under HG conditions, while the application of PPARβ/δ agonist rescued the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs under HG conditions and promoted the bone regeneration of calvarial defects in diabetic rats by enhancing AMPK/mTOR pathway-mediated autophagy (89).

3.5.1.3. PI3K/AKT pathways

Phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks) are a family of intracellular phosphorylating enzymes involved in cellular functions including cell growth, apoptosis, senescence, and differentiation (131). The activation of PI3Ks mediates the phosphorylation of protein kinase B (AKT), a signal transducer, which regulates multiple downstream agents (132–136). GSK3β is a known downstream target of AKT phosphorylation and plays a pivotal role in bone formation and remodeling (137). It has been shown that the reduced Runx2 expression in BMSCs led to the inhibition of osteogenic differentiation by PI3K/AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin pathway under HG conditions (137, 138). Besides, the down-regulation of miR-32-5p induced by hyperglycemia has been found to inhibit BMSCs osteogenic differentiation through the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β pathway (139). Another study also identified that the phosphorylation of AKT and GSK3β reversed the inhibited osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs under HG conditions (140).

ROS has been found to regulate PI3K directly, thus modulating downstream signaling and the transcription of target genes (141). The elevated ROS levels under HG conditions have been shown to prevent the phosphorylation of AKT and the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), inducing osteogenic inhibition in BMSCs (142, 143). Moreover, the suppression of PI3K/AKT pathways caused the reduction of antioxidant factor Nuclear factor-erythroid factor 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), which compromised ROS scavenging ability and aggravated oxidative stress, thereby forming a vicious cycle with osteogenic inhibition as the consequence (144). Besides ROS, it has been demonstrated that the reduction of periostin resulted in the osteogenic inhibition of BMSCs under HG conditions through the AKT pathway (145). Furthermore, the enhanced semaphorin3B expression has been demonstrated to alleviate the inhibition of osteogenic markers of BMSCs under HG conditions via PI3K/AKT pathways (59). Collectively, it has been well illustrated that PI3K/AKT/pathways are implicated in HG-mediated BMSCs osteogenesis and targeting PI3K/AKT/pathways might be a promising therapeutic approach to treat diabetic bone diseases.

3.5.1.4. MAPK pathways

The mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) cascades encompass major signal transduction pathways that are involved in the regulation of cell morphology, growth, survival, differentiation, and apoptosis upon a wide range of stimuli including cytokines, growth factors, oxygen radicals, and cell-cell interactions (146–149). The conventional MAPKs are characterized into three groups, termed extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK),c-Jun amino (N)-terminal kinases (JNK), and p38 isoforms, with phosphatase-mediated cross-talk between these MAPK cascades (150). The regulation of ERK, JNK, and p38 pathways on human MSC osteogenesis has been identified in 2000 (151). Of the three pathways, ERK is the most extensively studied cascade and has been shown to be vital for BMSCs osteogenesis, while its actual impacts under HG conditions remain controversial. It has been reported that HG treatment suppressed the phosphorylation of ERK by increasing the expression of miR-221-3p and miR-222-3p, thus inhibiting the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs (152). However, another study found that the phosphorylation of ERK was facilitated and MAPK/ERK pathway was activated in the impaired BMSCs osteogenesis under HG conditions (153). The different glucose concentrations might account for the perplexing findings, which need further investigation. The dephosphorylation of p38 and suppressed p38-MAPK pathway have also been found to correlate with the impaired BMSCs osteogenesis under HG conditions (154). The potential regulatory of JNK in this process is less well understood.

3.5.1.5. BMP pathway

BMPs are members of the transforming growth factor superfamily, which play a crucial role in bone and cartilage formation (155). BMP-2 is critical in the osteoblastic differentiation of BMSCs (156, 157). However, the BMP-2 expression in BMSCs under HG condition was significantly decreased, which led to reduced expression of osteogenic markers and impaired osteogenesis of BMSCs (58). Smads are also pivotal for the BMP pathways, which transduce the signal to the nucleus and regulate the transcription of target genes (158). Under HG conditions, the increased miR-203-3p expression inhibited the osteogenesis of BMSCs in vitro and impaired jaw bone quality of diabetic rats in vivo by suppressing BMP/Smad pathway via targeting Smad1 (159, 160). Moreover, hyperglycemia has been reported to hinder BMSCs osteogenesis through inhibition of the BMP/Smad pathway by targeting Smad1, Smad4, and Smad5 (161).

3.5.2. Epigenetic regulation

Epigenetic regulation, such as DNA methylation, histone acetylation, histone methylation and non-coding RNA, plays an important role in determining the differentiation direction of BMSCs (162, 163). Liu et al. discovered that diabetic rats with elevated levels of DNA methylation exhibited decreased bone mass and density. The in vitro application of 5-aza2’-deoxycytidine (5-aza-dC), a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, to reduce the levels of DNA methylation, rescued the osteogenic differentiation capacity of MSCs under hyperglycemic conditions (164). MicroRNAs (miRNAs), a small noncoding RNA, play a key role in modulating various cellular life processes, and they regulate gene expression via targeting specific mRNAs (165). It was reported that miR-337 suppressed osteogenesis in high glucose-treated BMSCs by targeting the 3’-UTR region of Rap1A, and knockdown of miR-337 promoted osteogenic differentiation. These results suggest that upregulated miR-337 inhibits osteogenesis in high glucose (166). The level of miR-9-5p has also been found to be increased in HG condition. MiR-9-5p knockdown promotes HG-induced osteogenic differentiation BMSCs in vitro and mitigates the diabetic osteoporosis condition of rats in vivo by targeting DDX17 (167). Over-expression of miR-542-3p induced by HG inhibits the osteoblast differentiation, whereas inhibition of miR-542-3p function by anti-miR-542-3p promoted expression of osteoblast-specific genes, alkaline phosphatase activity and matrix mineralization (168). Therefore, epigenetics, as an important regulatory mechanism of BMSC differentiation, plays a crucial role in determining the direction of differentiation. However, the epigenetic regulation mechanism underlying osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs in high glucose environments remains insufficiently studied.

3.5.3. Protein expression

Proteomics has been widely used as a powerful tool to investigate the protein expression on a large scale to identify potential biomarkers or activated proteins (169). One proteomic study found that high glucose levels can affect the expression of 12 proteins in BMSCs, including upregulation of annexin A7, fumarate hydratase, annexin A2, annexin A1 and alpha2-HS-glycoprotein. This may impair osteogenic differentiation and lead to glucose toxicity in diabetic conditions (170, 171). Additionally, tropomyosin alpha-1 chain was found to be downregulated in BMSCs cultured with high glucose, which plays roles in regulating cell proliferation, morphogenesis, vesicle trafficking and glucose metabolism. The results indicate that protein functions involved in bone formation can plausibly explain the bone deformability in patients with hyperglycemia (171–173). Although very little research has been done on proteomics, this is an area worth investigating as it could help us to better use stem cells in the field of tissue engineering.

3.5.4. Macrophage immunomodulation

DM alters components of immune systems and has been regarded as an inflammatory disease (174). Macrophages are specialized innate immune cells that orchestrate the immune response, tissue repair, and inflammation (175, 176). Macrophages produce distinct functional phenotypes in response to specific stimuli and signals, which is termed macrophage polarization. The two polarization outcomes are the classically-activated M1 subtype and the alternatively-activated M2 subtype (177, 178). Both M1 and M2 macrophages are closely related to inflammatory responses. M1 macrophages secret pro-inflammatory agents including IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, which inhibit osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs and have destructive effects on tissues (179–183). On the contrary, M2 macrophages exhibit an anti-inflammatory phenotype, which secrete multiple anti-inflammatory factors (184) and promote bone regeneration, and participate in tissue repair (182, 183). Studies have shown that the relationship between macrophages and BMSCs is reciprocal. As mentioned before, M2 macrophages can promote the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs, while M1 macrophages have a negative effect. Meanwhile, BMSCs can significantly regulate the phenotype and function of macrophages (185–188). Hence, improving the inflammatory environment by modulating the polarization state of macrophages has been considered a potential approach for the treatment of related diseases (189).

In a hyperglycemic setting, the morphology of macrophages has been shown to adopt a fried egg-like shape with dense filopodia that presents a typical M1-like appearance, while the macrophages cultured in normal glucose condition showed a more typical round shape that suggests a resting state (101). Besides, the restoration of the electrical microenvironment has been found to enhance M2/M1 ratio, which further facilitated BMSCs osteogenesis and bone regeneration in diabetic conditions (101). Moreover, the hyperglycemia enhanced the macrophage infiltration and expression of pro-inflammatory factors by up-regulating CCL2, a key regulator for macrophage recruitment and polarization during inflammation (190), which ultimately inhibited osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs through MAPK pathways and facilitated alveolar bone loss (191).

4. Strategies to rescue BMSCs osteogenesis under HG conditions

The impaired osteogenesis of BMSCs under HG conditions is a complicated process with comprehensive mechanisms. The approaches facilitating the recruitment and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs under HG conditions are in urgent demand for therapeutic purposes. Many attempts have been made to recover BMSCs osteogenesis in hyperglycemic settings to obtain sound clinical efficacy. Here, we summarized the approaches to attenuate the impaired BMSCs osteogenesis in the HG environment based on the aforementioned mechanisms.

The accumulation of ROS is a major cause of the impaired osteogenic capability of BMSCs. Hence, the methods targeting the removal of excessive ROS are promising to ameliorate impaired osteogenesis. Using the scaffolds with ROS-scavenging abilities greatly promoted the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs and improved the efficiency of bone defect regeneration in diabetic rats (192, 193). Other antioxidants, such as high-density lipoprotein (194), chrysin (144), and silibinin (142), have also been reported to alleviate HG-suppressed osteogenesis of BMSCs via an antioxidant effect. Furthermore, as the lead candidate for treating diabetes, metformin has been identified to scavenge the overproduced ROS under HG conditions to rescue the inhibited osteogenesis of BMSCs by reactivating the AMPK/β-catenin pathway (54). However, it is noteworthy that the physiological amount of ROS concentration is vital for the proliferation and differentiation of BMSCs, thus the proper dosage of antioxidants in specific conditions is critical and remains to be prudently determined.

The potentials of AGEs and autophagy in recovering BMSCs osteogenesis under HG conditions have also been identified. The application of adrenomedullin 2 reversed the HG-impaired BMSCs in vitro and accelerated bone regeneration in diabetic rats via attenuating AGE-induced imbalances in macrophage polarization through PPARγ/NF-κB signaling (195). Morroniside treatment also recovered the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs and reduced bone loss in diabetic rats by suppressing AGEs formation and RAGEs expression (196). In addition, the activation of PPARβ/δ improved the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs under HG conditions and promoted the bone regeneration of calvarial defects in diabetic rats by enhancing AMPK/mTOR pathway-mediated autophagy (89). Similar to ROS, both AGEs formation and autophagy are physiological events that play a pivotal role in cell metabolism. Hence, their potential to result in unwanted effects such as DNA damage and tumorigenicity should not be ignored and deserve further investigation.

The alteration of the pro-inflammatory environment has been proposed to recover the HG-induced inhibition of BMSCs osteogenesis. It has been reported that a novel biomimetic electrical nanocomposite membrane could attenuate pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage polarization via PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, thereby enhancing the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs and bone regeneration in rats with type 2 diabetes mellitus (101). The inhibition of inflammation using adrenomedullin 2 also exhibited similar effects in rats with type 1 diabetes mellitus (195). Moreover, the addition of BMP-4-loaded sustainable release nanoparticles into a scaffold reduced the levels of pro-inflammatory factors by promoting the polarization of RAW264.7 to M2 macrophages, which achieved favorable osteogenic activities both in vitro and in vivo on the basis of HG environment (100). Overall, the management of inflammation seems to be an ideal strategy allowing BMSCs to regain osteogenic ability under HG conditions, especially considering its benefits on other complications of DM such as kidney diseases, brain diseases, etc (197–199).

5. Conclusions

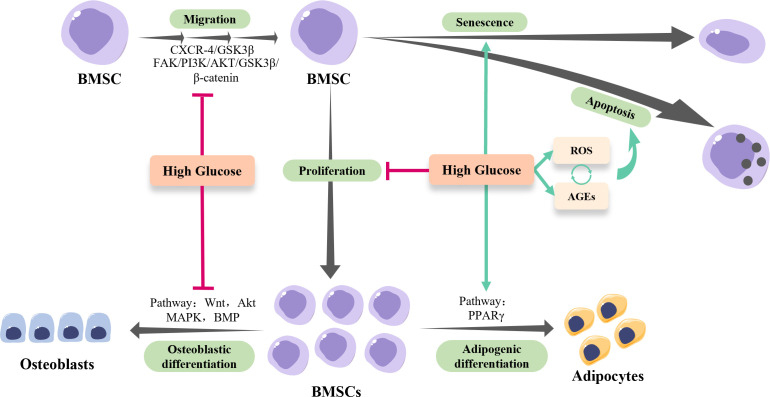

Individuals living with DM are more vulnerable to skeletal complications. Massive evidence indicates that the impaired osteogenic ability of BMSCs in hyperglycemic settings is a main cause of diabetic osteopathy such as increased fracture risk and impaired bone healing ( Figure 1 ). The osteogenesis of BMSCs is vital for bone growth and remodeling. In addition, BMSCs have been considered the ideal candidate for regenerative therapy to treat bone defects due to their easy accessibility, osteogenic potentials, and immunoregulatory function. Hence, revealing the mechanisms underlying and developing the strategies to rescue the HG-induced inhibition of BMSCs osteogenesis are of great significance for both diabetic bone diseases and regenerative therapy in diabetic patients.

Figure 1.

The osteogenesis of BMSCs in hyperglycemia. High-glucose conditions inhibit the migration and proliferation of BMSCs, while facilitate the senescence and apoptosis of BMSCs via regulating reactive oxygen species (ROS) and advanced glycation end products (AGEs) production. Of note, the excessive ROS generated by hyperglycemia results in the accumulation of AGEs, which in turn exacerbates ROS production, forming a positive feedback loop. In addition, high-glucose conditions shift BMSCs towards adipogenic lineage rather than osteogenic lineage via modulating multiple pathways.

The impacts of the HG environment on the osteogenic activities of BMSCs have been well characterized, while the underlying mechanisms are still elusive ( Figure 1 ). Based on current evidence, it is conceivable to summarize that the HG conditions disable the injury site to recruit enough BMSCs by suppressing the migration and proliferation of BMSCs. Moreover, the HG conditions inhibit the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs indirectly by promoting its senescence and apoptosis, and directly via multiple signaling pathways. As for the strategies, reducing intracellular ROS and suppressing AGEs-RAGEs axis activities seem to be effective, while the potential adverse effects should be studied in a holistic view. Modulating the pro-inflammatory micro-environment of DM might be more promising with relatively safe outcomes and fewer adverse effects.

In short, we have summarized the detailed impacts of HG conditions on the osteogenesis of BMSCs and the underlying mechanisms, the approaches to rescue the diminished osteogenesis of BMSCs and facilitate the BMSCs-based regenerative medicine in the diabetic environment and proposed some suggestions for future research.

Author contributions

ZZ and JY jointly conceived the manuscript. ML and JY performed the literature research and writing of the manuscript. ZZ revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 81801018 and 32271416) and Major Special Science and Technology Project of Sichuan Province (No. 2022ZDZX0031).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Herman WH. Diabetes epidemiology: guiding clinical and public health practice: the Kelly West award lecture, 2006. Diabetes Care (2007) 30:1912–9. doi: 10.2337/dc07-9924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Greene DA, Sima AAF, Stevens MJ, Feldman EL, Lattimer SA. Complications: neuropathy, pathogenetic considerations. Diabetes Care (1992) 15:1902–25. doi: 10.2337/diacare.15.12.1902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature (2001) 414:813–20. doi: 10.1038/414813a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kasperk C, Georgescu C, Nawroth P. Diabetes mellitus and bone metabolism. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes (2017) 125:213–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-123036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Geng T, Wang Y, Lu Q, Zhang Y-B, Chen J-X, Zhou Y-F, et al. Associations of new-onset atrial fibrillation with risks of cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and mortality among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care (2022) 45:2422–9. doi: 10.2337/dc22-0717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. International Diabetes Federation . IDF diabetes atlas. Available at: https://diabetesatlas.org/atlas/tenth-edition/.

- 7. Zheng Y, Ley SH, Hu FB. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat Rev Endocrinol (2018) 14:88–98. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Napoli N, Chandran M, Pierroz DD, Abrahamsen B, Schwartz AV, Ferrari SL. IOF bone and diabetes working group. mechanisms of diabetes mellitus-induced bone fragility. Nat Rev Endocrinol (2017) 13:208–19. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Khosla S, Samakkarnthai P, Monroe DG, Farr JN. Update on the pathogenesis and treatment of skeletal fragility in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol (2021) 17:685–97. doi: 10.1038/s41574-021-00555-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bizzarri C, Benevento D, Giannone G, Bongiovanni M, Anziano M, Patera IP, et al. Sexual dimorphism in growth and insulin-like growth factor-I in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Growth Horm IGF Res (2014) 24:256–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2014.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Watanabe K. Periodontitis in diabetics: is collaboration between physicians and dentists needed? Dis Mon (2011) 57:206–13. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2011.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dreyer H, Grischke J, Tiede C, Eberhard J, Schweitzer A, Toikkanen SE, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors of peri-implantitis: a systematic review. J Periodontal Res (2018) 53:657–81. doi: 10.1111/jre.12562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Genco RJ, Borgnakke WS. Diabetes as a potential risk for periodontitis: association studies. Periodontol 2000 (2020) 83:40–5. doi: 10.1111/prd.12270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Preshaw PM, Bissett SM. Periodontitis and diabetes. Br Dent J (2019) 227:577–84. doi: 10.1038/s41415-019-0794-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abdallah BM, Kassem M. Human mesenchymal stem cells: from basic biology to clinical applications. Gene Ther (2008) 15:109–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. De Luca M, Aiuti A, Cossu G, Parmar M, Pellegrini G, Robey PG. Advances in stem cell research and therapeutic development. Nat Cell Biol (2019) 21:801–11. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0344-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jin Z, Chen J, Shu B, Xiao Y, Tang D. Bone mesenchymal stem cell therapy for ovariectomized osteoporotic rats: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord (2019) 20:556. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2851-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huo S-C, Yue B. Approaches to promoting bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell osteogenesis on orthopedic implant surface. World J Stem Cells (2020) 12:545–61. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v12.i7.545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Son B-R, Marquez-Curtis LA, Kucia M, Wysoczynski M, Turner AR, Ratajczak J, et al. Migration of bone marrow and cord blood mesenchymal stem cells in vitro is regulated by stromal-derived factor-1-CXCR4 and hepatocyte growth factor-c-met axes and involves matrix metalloproteinases. Stem Cells (2006) 24:1254–64. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kyriakou C, Rabin N, Pizzey A, Nathwani A, Yong K. Factors that influence short-term homing of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a xenogeneic animal model. Haematologica (2008) 93:1457–65. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sordi V. Mesenchymal stem cell homing capacity. Transplantation (2009) 87:S42–45. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181a28533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lin W, Xu L, Zwingenberger S, Gibon E, Goodman SB, Li G. Mesenchymal stem cells homing to improve bone healing. J Orthopaedic Translation (2017) 9:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2017.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xiao Ling K, Peng L, Jian Feng Z, Wei C, Wei Yan Y, Nan S, et al. Stromal derived factor-1/CXCR4 axis involved in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells recruitment to injured liver. Stem Cells Int (2016) 2016:8906945. doi: 10.1155/2016/8906945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Deng Q-J, Xu X-F, Ren J. Effects of SDF-1/CXCR4 on the repair of traumatic brain injury in rats by mediating bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Mol Neurobiol (2018) 38:467–77. doi: 10.1007/s10571-017-0490-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zou C, Song G, Luo Q, Yuan L, Yang L. Mesenchymal stem cells require integrin β1 for directed migration induced by osteopontin in vitro . In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim (2011) 47:241–50. doi: 10.1007/s11626-010-9377-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu L, Luo Q, Sun J, Wang A, Shi Y, Ju Y, et al. Decreased nuclear stiffness via FAK-ERK1/2 signaling is necessary for osteopontin-promoted migration of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Cell Res (2017) 355:172–81. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu L, Luo Q, Sun J, Ju Y, Morita Y, Song G. Chromatin organization regulated by EZH2-mediated H3K27me3 is required for OPN-induced migration of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol (2018) 96:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2018.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Forte G, Minieri M, Cossa P, Antenucci D, Sala M, Gnocchi V, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor effects on mesenchymal stem cells: proliferation, migration, and differentiation. Stem Cells (2006) 24:23–33. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ball SG, Shuttleworth CA, Kielty CM. Vascular endothelial growth factor can signal through platelet-derived growth factor receptors. J Cell Biol (2007) 177:489–500. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nedeau AE, Bauer RJ, Gallagher K, Chen H, Liu Z-J, Velazquez OC. A CXCL5- and bFGF-dependent effect of PDGF-b-activated fibroblasts in promoting trafficking and differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Cell Res (2008) 314:2176–86. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xinaris C, Morigi M, Benedetti V, Imberti B, Fabricio AS, Squarcina E, et al. A novel strategy to enhance mesenchymal stem cell migration capacity and promote tissue repair in an injury specific fashion. Cell Transplant (2013) 22:423–36. doi: 10.3727/096368912X653246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang X, Zhen L, Miao H, Sun Q, Yang Y, Que B, et al. Concomitant retrograde coronary venous infusion of basic fibroblast growth factor enhances engraftment and differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells for cardiac repair after myocardial infarction. Theranostics (2015) 5:995–1006. doi: 10.7150/thno.11607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dubon MJ, Yu J, Choi S, Park K-S. Transforming growth factor β induces bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell migration via noncanonical signals and n-cadherin. J Cell Physiol (2018) 233:201–13. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhou S-B, Wang J, Chiang C-A, Sheng L-L, Li Q-F. Mechanical stretch upregulates SDF-1α in skin tissue and induces migration of circulating bone marrow-derived stem cells into the expanded skin. Stem Cells (2013) 31:2703–13. doi: 10.1002/stem.1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liang X, Huang X, Zhou Y, Jin R, Li Q. Mechanical stretching promotes skin tissue regeneration via enhancing mesenchymal stem cell homing and transdifferentiation. Stem Cells Transl Med (2016) 5:960–9. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yuan L, Sakamoto N, Song G, Sato M. Low-level shear stress induces human mesenchymal stem cell migration through the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis via MAPK signaling pathways. Stem Cells Dev (2013) 22:2384–93. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Raab M, Swift J, Dingal PCDP, Shah P, Shin J-W, Discher DE. Crawling from soft to stiff matrix polarizes the cytoskeleton and phosphoregulates myosin-II heavy chain. J Cell Biol (2012) 199:669–83. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201205056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mao X, Chen Z, Luo Q, Zhang B, Song G. Simulated microgravity inhibits the migration of mesenchymal stem cells by remodeling actin cytoskeleton and increasing cell stiffness. Cytotechnology (2016) 68:2235–43. doi: 10.1007/s10616-016-0007-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pierce JL, Begun DL, Westendorf JJ, McGee-Lawrence ME. Defining osteoblast and adipocyte lineages in the bone marrow. Bone (2019) 118:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2018.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Weinstein RS, Jilka RL, Almeida M, Roberson PK, Manolagas SC. Intermittent parathyroid hormone administration counteracts the adverse effects of glucocorticoids on osteoblast and osteocyte viability, bone formation, and strength in mice. Endocrinology (2010) 151:2641–9. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. D’Alimonte I, Lannutti A, Pipino C, Di Tomo P, Pierdomenico L, Cianci E, et al. Wnt signaling behaves as a “master regulator” in the osteogenic and adipogenic commitment of human amniotic fluid mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Rev Rep (2013) 9:642–54. doi: 10.1007/s12015-013-9436-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Adhami MD, Rashid H, Chen H, Javed A. Runx2 activity in committed osteoblasts is not essential for embryonic skeletogenesis. Connect Tissue Res (2014) 55 Suppl 1:102–6. doi: 10.3109/03008207.2014.923873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jensen ED, Gopalakrishnan R, Westendorf JJ. Regulation of gene expression in osteoblasts. Biofactors (2010) 36:25–32. doi: 10.1002/biof.72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Knothe Tate ML, Adamson JR, Tami AE, Bauer TW. The osteocyte. Int J Biochem Cell Biol (2004) 36:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(03)00241-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yu B, Wang C-Y. Osteoporosis: the result of an “Aged” bone microenvironment. Trends Mol Med (2016) 22:641–4. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhou R, Guo Q, Xiao Y, Guo Q, Huang Y, Li C, et al. Endocrine role of bone in the regulation of energy metabolism. Bone Res (2021) 9:25. doi: 10.1038/s41413-021-00142-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang H, Li X, Li J, Zhong L, Chen X, Chen S. SDF-1 mediates mesenchymal stem cell recruitment and migration via the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis in bone defect. J Bone Miner Metab (2021) 39:126–38. doi: 10.1007/s00774-020-01122-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Carbone LD, Bůžková P, Fink HA, Robbins JA, Bethel M, Hamrick MW, et al. Association of plasma SDF-1 with bone mineral density, body composition, and hip fractures in older adults: the cardiovascular health study. Calcif Tissue Int (2017) 100:599–608. doi: 10.1007/s00223-017-0245-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang B, Liu N, Shi H, Wu H, Gao Y, He H, et al. High glucose microenvironments inhibit the proliferation and migration of bone mesenchymal stem cells by activating GSK3β. J Bone Miner Metab (2016) 34:140–50. doi: 10.1007/s00774-015-0662-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Liang C, Liu X, Liu C, Xu Y, Geng W, Li J. Integrin α10 regulates adhesion, migration, and osteogenic differentiation of alveolar bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in type 2 diabetic patients who underwent dental implant surgery. Bioengineered (2022) 13:13252–68. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2022.2079254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang T, Yang X, Qi X, Jiang C. Osteoinduction and proliferation of bone-marrow stromal cells in three-dimensional poly (ϵ-caprolactone)/hydroxyapatite/collagen scaffolds. J Transl Med (2015) 13:152. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0499-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chen I, Salhab I, Setzer FC, Kim S, Nah H-D. A new calcium silicate-based bioceramic material promotes human osteo- and odontogenic stem cell proliferation and survival via the extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling pathway. J Endod (2016) 42:480–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lee DJ, Lee Y-T, Zou R, Daniel R, Ko C-C. Polydopamine-laced biomimetic material stimulation of bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells to promote osteogenic effects. Sci Rep (2017) 7:12984. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13326-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wang H, Chang X, Ma Q, Sun B, Li H, Zhou J, et al. Bioinspired drug-delivery system emulating the natural bone healing cascade for diabetic periodontal bone regeneration. Bioact Mater (2022) 21:324–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.08.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang X, Qin J, Wang X, Guo X, Liu J, Wang X, et al. Netrin-1 improves adipose-derived stem cell proliferation, migration, and treatment effect in type 2 diabetic mice with sciatic denervation. Stem Cell Res Ther (2018) 9:285. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-1020-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hankamolsiri W, Manochantr S, Tantrawatpan C, Tantikanlayaporn D, Tapanadechopone P, Kheolamai P. The effects of high glucose on adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of gestational tissue-derived MSCs. Stem Cells Int (2016) 2016:9674614. doi: 10.1155/2016/9674614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Guo Z, Chen R, Zhang F, Ding M, Wang P. Exendin-4 relieves the inhibitory effects of high glucose on the proliferation and osteoblastic differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells. Arch Oral Biol (2018) 91:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2018.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wang J, Wang B, Li Y, Wang D, Lingling E, Bai Y, et al. High glucose inhibits osteogenic differentiation through the BMP signaling pathway in bone mesenchymal stem cells in mice. EXCLI J (2013) 12:584–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Xing Q, Feng J, Zhang X. Semaphorin3B promotes proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in a high-glucose microenvironment. Stem Cells Int (2021) 2021:6637176. doi: 10.1155/2021/6637176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gu Z, Jiang J, Xia Y, Yue X, Yan M, Tao T, et al. p21 is associated with the proliferation and apoptosis of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells from non-obese diabetic mice. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes (2013) 121:607–13. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1354380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kim YS, Kwon JS, Hong MH, Kang WS, Jeong H, Kang H, et al. Restoration of angiogenic capacity of diabetes-insulted mesenchymal stem cells by oxytocin. BMC Cell Biol (2013) 14:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-14-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhao Y-F, Zeng D-L, Xia L-G, Zhang S-M, Xu L-Y, Jiang X-Q, et al. Osteogenic potential of bone marrow stromal cells derived from streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Int J Mol Med (2013) 31:614–20. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Stolzing A, Bauer E, Scutt A. Suspension cultures of bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells: effects of donor age and glucose level. Stem Cells Dev (2012) 21:2718–23. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ezquer F, Ezquer M, Simon V, Conget P. The antidiabetic effect of MSCs is not impaired by insulin prophylaxis and is not improved by a second dose of cells. PloS One (2011) 6:e16566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jin P, Zhang X, Wu Y, Li L, Yin Q, Zheng L, et al. Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat-derived bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells have impaired abilities in proliferation, paracrine, antiapoptosis, and myogenic differentiation. Transplant Proc (2010) 42:2745–52. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.05.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Stolzing A, Sellers D, Llewelyn O, Scutt A. Diabetes induced changes in rat mesenchymal stem cells. Cells Tissues Organs (2010) 191:453–65. doi: 10.1159/000281826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gopalakrishnan V, Vignesh RC, Arunakaran J, Aruldhas MM, Srinivasan N. Effects of glucose and its modulation by insulin and estradiol on BMSC differentiation into osteoblastic lineages. Biochem Cell Biol (2006) 84:93–101. doi: 10.1139/o05-163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hernandez-Segura A, Nehme J, Demaria M. Hallmarks of cellular senescence. Trends Cell Biol (2018) 28:436–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Weng Z, Wang Y, Ouchi T, Liu H, Qiao X, Wu C, et al. Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal cell senescence: hallmarks, mechanisms, and combating strategies. Stem Cells Transl Med (2022) 11:356–71. doi: 10.1093/stcltm/szac004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kornicka K, Houston J, Marycz K. Dysfunction of mesenchymal stem cells isolated from metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetic patients as result of oxidative stress and autophagy may limit their potential therapeutic use. Stem Cell Rev Rep (2018) 14:337–45. doi: 10.1007/s12015-018-9809-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yin M, Zhang Y, Yu H, Li X. Role of hyperglycemia in the senescence of mesenchymal stem cells. Front Cell Dev Biol (2021) 9:665412. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.665412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Stolzing A, Coleman N, Scutt A. Glucose-induced replicative senescence in mesenchymal stem cells. Rejuvenation Res (2006) 9:31–5. doi: 10.1089/rej.2006.9.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Chang T-C, Hsu M-F, Wu KK. High glucose induces bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell senescence by upregulating autophagy. PloS One (2015) 10:e0126537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-α: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science (1993) 259:87–91. doi: 10.1126/science.7678183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Uysal KT, Wiesbrock SM, Marino MW, Hotamisligil GS. Protection from obesity-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking TNF-alpha function. Nature (1997) 389:610–4. doi: 10.1038/39335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Cramer C, Freisinger E, Jones RK, Slakey DP, Dupin CL, Newsome ER, et al. Persistent high glucose concentrations alter the regenerative potential of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev (2010) 19:1875–84. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Jakus V, Bauerová K, Michalková D, Cársky J. Serum levels of advanced glycation end products in poorly metabolically controlled children with diabetes mellitus: relation to HbA1c. Diabetes Nutr Metab (2001) 14:207–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Valcourt U, Merle B, Gineyts E, Viguet-Carrin S, Delmas PD, Garnero P. Non-enzymatic glycation of bone collagen modifies osteoclastic activity and differentiation*. J Biol Chem (2007) 282:5691–703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610536200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Weinberg E, Maymon T, Weinreb M. AGEs induce caspase-mediated apoptosis of rat BMSCs via TNFα production and oxidative stress. J Mol Endocrinol (2014) 52:67–76. doi: 10.1530/JME-13-0229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zhu Q, Hao H, Xu H, Fichman Y, Cui Y, Yang C, et al. Combination of antioxidant enzyme overexpression and n-acetylcysteine treatment enhances the survival of bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells in ischemic limb in mice with type 2 diabetes. J Am Heart Association: Cardiovasc Cerebrovascular Dis (2021) 10:e023491. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.023491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Jiang M, Wang X, Wang P, Peng W, Zhang B, Guo L. Inhibitor of RAGE and glucose−induced inflammation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: effect and mechanism of action. Mol Med Rep (2020) 22:3255–62. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.11422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Fulda S, Gorman AM, Hori O, Samali A. Cellular stress responses: cell survival and cell death. Int J Cell Biol (2010) 2010:e214074. doi: 10.1155/2010/214074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Dai P, Mao Y, Sun X, Li X, Muhammad I, Gu W, et al. Attenuation of oxidative stress-induced osteoblast apoptosis by curcumin is associated with preservation of mitochondrial functions and increased akt-GSK3β signaling. CPB (2017) 41:661–77. doi: 10.1159/000457945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Li H, Liu J, Wang Y, Fu Z, Hüttemann M, Monks TJ, et al. MiR-27b augments bone marrow progenitor cell survival via suppressing the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab (2017) 313:E391–401. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00073.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Du X, Matsumura T, Edelstein D, Rossetti L, Zsengellér Z, Szabó C, et al. Inhibition of GAPDH activity by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activates three major pathways of hyperglycemic damage in endothelial cells. J Clin Invest (2003) 112:1049–57. doi: 10.1172/JCI200318127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Li J, He W, Liao B, Yang J. FFA-ROS-P53-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis contributes to reduction of osteoblastogenesis and bone mass in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Sci Rep (2015) 5:12724. doi: 10.1038/srep12724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Kong Y, Cheng L, Ma L, Li H, Cheng B, Zhao Y. Norepinephrine protects against apoptosis of mesenchymal stem cells induced by high glucose. J Cell Physiol (2019) 234:20801–15. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Fang J, Chen Z, Lai X, Yin W, Guo Y, Zhang W, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells-derived HIF-1α-overexpressed extracellular vesicles ameliorate hypoxia-induced pancreatic β cell apoptosis and senescence through activating YTHDF1-mediated protective autophagy. Bioorg Chem (2022) 129:106194. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2022.106194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Chen M, Jing D, Ye R, Yi J, Zhao Z. PPARβ/δ accelerates bone regeneration in diabetic mellitus by enhancing AMPK/mTOR pathway-mediated autophagy. Stem Cell Res Ther (2021) 12:566. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02628-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Zhang M, Yang B, Peng S, Xiao J. Metformin rescues the impaired osteogenesis differentiation ability of rat adipose-derived stem cells in high glucose by activating autophagy. Stem Cells Dev (2021) 30:1017–27. doi: 10.1089/scd.2021.0181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Lu J, Li R, Ni S, Xie Y, Liu X, Zhang K, et al. Metformin carbon nanodots promote odontoblastic differentiation of dental pulp stem cells by pathway of autophagy. Front Bioeng Biotechnol (2022) 10:1002291. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.1002291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Li Q, Yin Y, Zheng Y, Chen F, Jin P. Inhibition of autophagy promoted high glucose/ROS-mediated apoptosis in ADSCs. Stem Cell Res Ther (2018) 9:289. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-1029-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Murray CE, Coleman CM. Impact of diabetes mellitus on bone health. Int J Mol Sci (2019) 20:E4873. doi: 10.3390/ijms20194873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Scherz-Shouval R, Elazar Z. Regulation of autophagy by ROS: physiology and pathology. Trends Biochem Sci (2011) 36:30–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Chang K-C, Liu P-F, Chang C-H, Lin Y-C, Chen Y-J, Shu C-W. The interplay of autophagy and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis and therapy of retinal degenerative diseases. Cell Biosci (2022) 12:1. doi: 10.1186/s13578-021-00736-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Takada I, Kouzmenko AP, Kato S. Wnt and PPARγ signaling in osteoblastogenesis and adipogenesis. Nat Rev Rheumatol (2009) 5:442–7. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Jiating L, Buyun J, Yinchang Z. Role of metformin on osteoblast differentiation in type 2 diabetes. BioMed Res Int (2019) 2019:9203934–9203934. doi: 10.1155/2019/9203934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Dong K, Zhou W, Liu Z-H. Metformin enhances the osteogenic activity of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells by inhibiting oxidative stress induced by diabetes mellitus: an in vitro and in vivo study. J Periodontal Implant Sci (2022) 52:54–68. doi: 10.5051/jpis.2106240312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Li Z, Wang X, Hong T-P, Wang H-J, Gao Z-Y, Wan M. Advanced glycosylation end products inhibit the proliferation of bone-marrow stromal cells through activating MAPK pathway. Eur J Med Res (2021) 26:94. doi: 10.1186/s40001-021-00559-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Sun X, Ma Z, Zhao X, Jin W, Zhang C, Ma J, et al. Three-dimensional bioprinting of multicell-laden scaffolds containing bone morphogenic protein-4 for promoting M2 macrophage polarization and accelerating bone defect repair in diabetes mellitus. Bioact Mater (2021) 6:757–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Dai X, Heng BC, Bai Y, You F, Sun X, Li Y, et al. Restoration of electrical microenvironment enhances bone regeneration under diabetic conditions by modulating macrophage polarization. Bioact Mater (2021) 6:2029–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Yu S, Zhu K, Lai Y, Zhao Z, Fan J, Im H-J, et al. atf4 promotes β-catenin expression and osteoblastic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Biol Sci (2013) 9:256–66. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.5898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Zhu Y, Wang Y, Jia Y, Xu J, Chai Y. Catalpol promotes the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via the wnt/β-catenin pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther (2019) 10:37. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1143-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Matsushita Y, Nagata M, Kozloff KM, Welch JD, Mizuhashi K, Tokavanich N, et al. A wnt-mediated transformation of the bone marrow stromal cell identity orchestrates skeletal regeneration. Nat Commun (2020) 11:332. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14029-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Zhou T, Gao B, Fan Y, Liu Y, Feng S, Cong Q, et al. Piezo1/2 mediate mechanotransduction essential for bone formation through concerted activation of NFAT-YAP1-ß-catenin. Elife (2020) 9:e52779. doi: 10.7554/eLife.52779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Bennett CN, Ouyang H, Ma YL, Zeng Q, Gerin I, Sousa KM, et al. Wnt10b increases postnatal bone formation by enhancing osteoblast differentiation. J Bone Miner Res (2007) 22:1924–32. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Stevens JR, Miranda-Carboni GA, Singer MA, Brugger SM, Lyons KM, Lane TF. Wnt10b deficiency results in age-dependent loss of bone mass and progressive reduction of mesenchymal progenitor cells. J Bone Miner Res (2010) 25:2138–47. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Ross SE, Hemati N, Longo KA, Bennett CN, Lucas PC, Erickson RL, et al. Inhibition of adipogenesis by wnt signaling. Science (2000) 289:950–3. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Keats EC, Dominguez JM, Grant MB, Khan ZA. Switch from canonical to noncanonical wnt signaling mediates high glucose-induced adipogenesis. Stem Cells (2014) 32:1649–60. doi: 10.1002/stem.1659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Lao A, Chen Y, Sun Y, Wang T, Lin K, Liu J, et al. Transcriptomic analysis provides a new insight: oleuropein reverses high glucose-induced osteogenic inhibition in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via Wnt10b activation. Front Bioeng Biotechnol (2022) 10:990507. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.990507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Ling LS, Voskas D, Woodgett JR. Activation of PDK-1 maintains mouse embryonic stem cell self-renewal in a PKB-dependent manner. Oncogene (2013) 32:5397–408. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Chen Y, Chen L, Huang R, Yang W, Chen S, Lin K, et al. Investigation for GSK3β expression in diabetic osteoporosis and negative osteogenic effects of GSK3β on bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells under a high glucose microenvironment. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2021) 534:727–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Huang X, Xu J, Huang M, Li J, Dai L, Dai K, et al. Histone deacetylase1 promotes TGF-β1-mediated early chondrogenesis through down-regulating canonical wnt signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2014) 453:810–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Deng Y, Zhu W, lin A, Wang C, Xiong C, Xu F, et al. Exendin-4 promotes bone formation in diabetic states via HDAC1-wnt/β-catenin axis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2021) 544:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.01.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Fairfield H, Falank C, Harris E, Demambro V, McDonald M, Pettitt JA, et al. The skeletal cell-derived molecule sclerostin drives bone marrow adipogenesis. J Cell Physiol (2018) 233:1156–67. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Li Z, Zhao H, Chu S, Liu X, Qu X, Li J, et al. miR-124-3p promotes BMSC osteogenesis via suppressing the GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling pathway in diabetic osteoporosis rats. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim (2020) 56:723–34. doi: 10.1007/s11626-020-00502-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Wang R, Zhang Y, Jin F, Li G, Sun Y, Wang X. High-glucose-induced miR-214-3p inhibits BMSCs osteogenic differentiation in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cell Death Discovery (2019) 5:143. doi: 10.1038/s41420-019-0223-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Zhai Z, Chen W, Hu Q, Wang X, Zhao Q, Tuerxunyiming M. High glucose inhibits osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via regulating miR-493-5p/ZEB2 signalling. J Biochem (2020) 167:613–21. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvaa011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Cuzzocrea S, Wayman NS, Mazzon E, Dugo L, Di Paola R, Serraino I, et al. The cyclopentenone prostaglandin 15-deoxy-Delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J(2) attenuates the development of acute and chronic inflammation. Mol Pharmacol (2002) 61:997–1007. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.5.997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Takayama O, Yamamoto H, Damdinsuren B, Sugita Y, Ngan CY, Xu X, et al. Expression of PPARdelta in multistage carcinogenesis of the colorectum: implications of malignant cancer morphology. Br J Cancer (2006) 95:889–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Chawla A, Barak Y, Nagy L, Liao D, Tontonoz P, Evans RM. PPAR-gamma dependent and independent effects on macrophage-gene expression in lipid metabolism and inflammation. Nat Med (2001) 7:48–52. doi: 10.1038/83336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Cariello M, Piccinin E, Moschetta A. Transcriptional regulation of metabolic pathways via lipid-sensing nuclear receptors PPARs, FXR, and LXR in NASH. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol (2021) 11:1519–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2021.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Xu C, Wang J, Zhu T, Shen Y, Tang X, Fang L, et al. Cross-talking between PPAR and WNT signaling and its regulation in mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther (2016) 11:247–54. doi: 10.2174/1574888x10666150723145707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Li Y, Jin D, Xie W, Wen L, Chen W, Xu J, et al. PPAR-γ and wnt regulate the differentiation of MSCs into adipocytes and osteoblasts respectively. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther (2018) 13:185–92. doi: 10.2174/1574888X12666171012141908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Beresford JN, Bennett JH, Devlin C, Leboy PS, Owen ME. Evidence for an inverse relationship between the differentiation of adipocytic and osteogenic cells in rat marrow stromal cell cultures. J Cell Sci (1992) 102:341–51. doi: 10.1242/jcs.102.2.341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Dorheim M-A, Sullivan M, Dandapani V, Wu X, Hudson J, Segarini PR, et al. Osteoblastic gene expression during adipogenesis in hematopoietic supporting murine bone marrow stromal cells. J Cell Physiol (1993) 154:317–28. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041540215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Botolin S, Faugere M-C, Malluche H, Orth M, Meyer R, McCabe LR. Increased bone adiposity and PPARγ2 expression in type I diabetic mice. Endocrinology (2005) 146:3622–31. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Chuang CC, Yang RS, Tsai KS, Ho FM, Liu SH. Hyperglycemia enhances adipogenic induction of lipid accumulation: involvement of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 1/2, phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma signaling. Endocrinology (2007) 148:4267–75. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Scholtysek C, Katzenbeisser J, Fu H, Uderhardt S, Ipseiz N, Stoll C, et al. PPARβ/δ governs wnt signaling and bone turnover. Nat Med (2013) 19:608–13. doi: 10.1038/nm.3146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Müller DIH, Stoll C, Palumbo-Zerr K, Böhm C, Krishnacoumar B, Ipseiz N, et al. PPARδ-mediated mitochondrial rewiring of osteoblasts determines bone mass. Sci Rep (2020) 10:8428. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-65305-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. The phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase–AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer (2002) 2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Sliva D, Jedinak A, Kawasaki J, Harvey K, Slivova V. Phellinus linteus suppresses growth, angiogenesis and invasive behaviour of breast cancer cells through the inhibition of AKT signalling. Br J Cancer (2008) 98:1348–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Liu X, Bruxvoort KJ, Zylstra CR, Liu J, Cichowski R, Faugere M-C, et al. Lifelong accumulation of bone in mice lacking pten in osteoblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2007) 104:2259–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604153104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Vincent EE, Elder DJE, Thomas EC, Phillips L, Morgan C, Pawade J, et al. Akt phosphorylation on Thr308 but not on Ser473 correlates with akt protein kinase activity in human non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer (2011) 104:1755–61. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Kim SY, Lee J-Y, Park Y-D, Kang KL, Lee J-C, Heo JS. Hesperetin alleviates the inhibitory effects of high glucose on the osteoblastic differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells. PloS One (2013) 8:e67504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Akinleye A, Avvaru P, Furqan M, Song Y, Liu D. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors as cancer therapeutics. J Hematol Oncol (2013) 6:88. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-6-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Muccioli S, Brillo V, Chieregato L, Leanza L, Checchetto V, Costa R. From channels to canonical wnt signaling: a pathological perspective. Int J Mol Sci (2021) 22:4613. doi: 10.3390/ijms22094613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Chen Y, Hu Y, Yang L, Zhou J, Tang Y, Zheng L, et al. Runx2 alleviates high glucose-suppressed osteogenic differentiation via PI3K/AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin pathway. Cell Biol Int (2017) 41:822–32. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Zhu G, Chai J, Ma L, Duan H, Zhang H. Downregulated microRNA-32 expression induced by high glucose inhibits cell cycle progression via PTEN upregulation and akt inactivation in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2013) 433:526–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Gong F, Gao L, Ma L, Li G, Yang J. Uncarboxylated osteocalcin alleviates the inhibitory effect of high glucose on osteogenic differentiation of mouse bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells by regulating TP63. BMC Mol Cell Biol (2021) 22:24. doi: 10.1186/s12860-021-00365-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Kma L, Baruah TJ. The interplay of ROS and the PI3K/Akt pathway in autophagy regulation. Biotechnol Appl Biochem (2022) 69:248–64. doi: 10.1002/bab.2104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Ying X, Chen X, Liu H, Nie P, Shui X, Shen Y, et al. Silibinin alleviates high glucose-suppressed osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow stromal cells via antioxidant effect and PI3K/Akt signaling. Eur J Pharmacol (2015) 765:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Zhou R, Ma Y, Qiu S, Gong Z, Zhou X. Metformin promotes cell proliferation and osteogenesis under high glucose condition by regulating the ROS−AKT−mTOR axis. Mol Med Rep (2020) 22:3387–95. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.11391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Li Y, Wang X. Chrysin attenuates high glucose-induced BMSC dysfunction via the activation of the PI3K/AKT/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther (2022) 16:165–82. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S335024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Yan Y, Zhang H, Liu L, Chu Z, Ge Y, Wu J, et al. Periostin reverses high glucose-inhibited osteogenesis of periodontal ligament stem cells via AKT pathway. Life Sci (2020) 242:117184. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.117184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Wada T, Penninger JM. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in apoptosis regulation. Oncogene (2004) 23:2838–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Panka DJ, Atkins MB, Mier JW. Targeting the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in the treatment of malignant melanoma. Clin Cancer Res (2006) 12:2371s–5s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Wang X, Tournier C. Regulation of cellular functions by the ERK5 signalling pathway. Cell Signal (2006) 18:753–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Johnson GL, Lapadat R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science (2002) 298:1911–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1072682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Kiel C, Serrano L. Challenges ahead in signal transduction: MAPK as an example. Curr Opin Biotechnol (2012) 23:305–14. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Jaiswal RK, Jaiswal N, Bruder SP, Mbalaviele G, Marshak DR, Pittenger MF. Adult human mesenchymal stem cell differentiation to the osteogenic or adipogenic lineage is regulated by mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem (2000) 275:9645–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Gan K, Dong G-H, Wang N, Zhu J-F. miR-221-3p and miR-222-3p downregulation promoted osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchyme stem cells through IGF-1/ERK pathway under high glucose condition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract (2020) 167:108121. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Wang Y-N, Jia T, Zhang J, Lan J, Zhang D, Xu X. PTPN2 improves implant osseointegration in T2DM via inducing the dephosphorylation of ERK. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) (2019) 244:1493–503. doi: 10.1177/1535370219883419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Wang Y, Huang L, Qin Z, Yuan H, Li B, Pan Y, et al. Parathyroid hormone ameliorates osteogenesis of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells against glucolipotoxicity through p38 MAPK signaling. IUBMB Life (2021) 73:213–22. doi: 10.1002/iub.2420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Wang RN, Green J, Wang Z, Deng Y, Qiao M, Peabody M, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling in development and human diseases. Genes Dis (2014) 1:87–105. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Chen D, Zhao M, Mundy GR. Bone morphogenetic proteins. Growth Factors (2004) 22:233–41. doi: 10.1080/08977190412331279890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Wang A, Ding X, Sheng S, Yao Z. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor in the osteogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow stromal cells. Yonsei Med J (2010) 51:740–5. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2010.51.5.740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Nishimura R, Hata K, Ikeda F, Matsubara T, Yamashita K, Ichida F, et al. The role of smads in BMP signaling. Front Biosci (2003) 8:s275–284. doi: 10.2741/1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Miyazono K, Maeda S, Imamura T. Coordinate regulation of cell growth and differentiation by TGF-beta superfamily and runx proteins. Oncogene (2004) 23:4232–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Tang Y, Zheng L, Zhou J, Chen Y, Yang L, Deng F, et al. miR−203−3p participates in the suppression of diabetes−associated osteogenesis in the jaw bone through targeting Smad1. Int J Mol Med (2018) 41:1595–607. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]