Abstract

Importance: To fulfill their societal role, occupational therapists need to exist in sufficient supply, be equitably distributed, and meet competency standards. Occupational therapy workforce research is instrumental in reaching these aims, but its global status is unknown.

Objective: To map the volume and nature (topics, methods, geography, funding) of occupational therapy workforce research worldwide.

Data Sources: Six scientific databases (MEDLINE/PubMed, Scopus, CINAHL, Web of Science Core Collection, PDQ–Evidence for Informed Health Policymaking, OTseeker), institutional websites, snowballing, and key informants.

Study Selection and Data Collection: Research articles of any kind were included if they involved data regarding occupational therapists and addressed 1 of 10 predefined workforce research categories. Two reviewers were used throughout study selection. No language or time restrictions applied, but the synthesis excluded publications before 1996. A linear regression examined the publications’ yearly growth.

Findings: Seventy-eight studies met the inclusion criteria, 57 of which had been published since 1996. Although significant (p < .01), annual publication growth was weak (0.07 publications/yr). “Attractiveness and retention” was a common topic (27%), and cross-sectional surveys were frequent study designs (53%). Few studies used inferential statistics (39%), focused on resource-poor countries (11%), used standardized instruments (10%), or tested a hypothesis (2%). Only 30% reported funding; these studies had stronger methodology: 65% used inferential statistics, and just 6% used exploratory cross-sectional surveys.

Conclusions and Relevance: Worldwide occupational therapy workforce research is scant and inequitably distributed, uses suboptimal methods, and is underfunded. Funded studies used stronger methods. Concerted efforts are needed to strengthen occupational therapy workforce research.

What This Article Adds: This review highlights the opportunity to develop a stronger, evidence-based strategy for workforce development and professional advocacy.

This review highlights the opportunity to develop a stronger, evidence-based strategy for occupational therapy workforce development and professional advocacy.

The health workforce refers to all people engaged in actions whose primary aim is to enhance health (World Health Organization [WHO], 2006). It includes health professionals such as, but not limited to, nurses, pharmacists, physical therapists, physicians, and occupational therapists.

Occupational therapists are needed to meet the health, rehabilitation, and occupational needs of the population worldwide (World Federation of Occupational Therapists [WFOT], 2021). According to WFOT (2013), occupational therapists aim to improve the health and well-being of individuals and communities through the promotion of meaningful occupational engagement. Occupational therapists address the occupational needs of people experiencing a wide range of health conditions and disabilities, and they also assume health promotion roles (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2020). In addition, occupational therapists address health, human rights, and occupational injustices arising from socioenvironmental factors (Bailliard et al., 2020; Serrata Malfitano et al., 2016; WFOT, 2019).

To fulfill their societal role, occupational therapists need to be in sufficient supply, equitably distributed (e.g., across geographical or practice areas), and motivated in their everyday practice, and they need to meet key competency standards (WFOT, 2021). One strategy for assessing, meeting, or improving performance of these requirements is to develop and use occupational therapy workforce research. In particular, this research can identify current and future supply shortages; determine inequitable workforce distribution (e.g., scarcity in rural areas); and study the impact of policy, management, and regulations on workforce recruitment, retention, and performance (Campbell, 2013; Campbell et al., 2013; George et al., 2018; Kuhlmann et al., 2018). Overall, health workforce research is key to providing evidence to inform and evaluate population-centered workforce policies and practices, as well as development and professional advocacy activities (Buchan et al., 2020; George et al., 2018; Kuhlmann et al., 2018).

The World Health Organization’s (WHO’s; 2016b) Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health provides global guidance for health workforce research and development as a whole. At the health professions level, the WHO (2016a; Ajuebor et al., 2019) also launched the Global Strategic Directions for Strengthening Nursing and Midwifery, a profession-specific framework used to guide global, concerted developments for this workforce.

With respect to the rehabilitation field, strategies to guide workforce development have been reported (Gimigliano & Negrini, 2017; Jesus et al., 2017), and WHO recently launched the Rehabilitation Competency Framework to provide a cross-professional, cross-national tool for framing, studying, and developing the competencies of the rehabilitation workforce (Mills et al., 2021).

Finally, WFOT (2021) recently published a position statement endorsing the role and value of workforce research and development activities for the occupational therapy profession, including identifying and reducing workforce disparities to improve access to occupational therapy. Little is known, however, about occupational therapy workforce research, warranting the need to map workforce research at the global level.

The aim of this scoping review was to identify and map the extent, range, and nature (e.g., volume, topics, geographical focus, funding status, study design, and methods) of occupational therapy workforce research worldwide. An assessment of the global status of such research can help inform strategic directions for further investigations in this area.

Method

Design

Scoping reviews often address exploratory research questions with the aim of mapping concepts, research methods, and types of evidence; they also identify gaps in the literature or in a research area. In short, scoping reviews determine the volume and nature of research activity on a broad topic to inform policy, practice, and research (Colquhoun et al., 2014; Levac et al., 2010; Peters et al., 2021; Tricco et al., 2018).

In addition to the traditional Arksey and O’Malley (2005) framework and subsequent refinements (Colquhoun et al., 2014; Daudt et al., 2013; Levac et al., 2010), we followed the recent Joanna Briggs Institute’s guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews (Peters et al., 2020). Although the review protocol is not registered (the PROSPERO database does not accept scoping review protocols), it has been peer reviewed and published a priori (Jesus et al., 2021). The protocol provides a detailed description of the review procedures and methodological options; here, we provide a synthesis of the methodology we used.

In this article, we provide the first part of our scoping review results: a quantitative map of the volume, yearly distribution, topics, geographical focus, study design and methods, and funding status of the included literature. The types of findings and reported recommendations or limitations—largely a qualitative synthesis—will be published in a separate article.

Database Searches

Systematic searches of six electronic databases (MEDLINE/PubMed, Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus, CINAHL, PDQ–Evidence for Informed Health Policymaking, OTseeker) were conducted in June 2021. The full details of the search strategy for the MEDLINE/PubMed database, which was used to guide the searches of the other databases, can be found in Jesus et al. (2021). The search strategy was built by Tiago S. Jesus, who has an extensive track record in bibliometric research and in designing database search strategies for the rehabilitation and health workforce fields, and it was appraised with the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies guidelines (McGowan et al., 2016). Web of Science and Scopus cover multidisciplinary literature beyond the health sector, which accommodates the diverse practice fields (e.g., educational and social sectors) in which occupational therapists work, in addition to the health sector.

The gray literature, here only official research-based reports, was searched through screening and keyword searches of the websites of the following select international institutions: WFOT, the rehabilitation and health workforce subsections of WHO, the Health Workforce Research section of the European Public Health Association, and the member organizations of WFOT, as planned in the protocol (Jesus et al., 2021).

Finally, we also used snowballing techniques (e.g., searching reference lists of included articles, author tracking), and we consulted with representatives of 105 WFOT member organizations. We supplied them with a preliminary list of inclusion criteria and asked them to identify any additional references that potentially fit the criteria and were missed from the combination of search strategies. Sixteen member-organization representatives responded and collectively generated 15 additional articles considered for inclusion.

Eligibility Criteria

We included occupational therapy workforce research fitting at least one category of workforce research defined a priori in the study protocol (Jesus et al., 2021). Table 1 describes each inclusion category as synthesized from the protocol. The design of the inclusion categories was informed by a WFOT (2021) position statement; a review of the rehabilitation workforce literature (Jesus et al., 2017); the Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health (WHO, 2016b); and a reader on health policy, systems, and services research falling into the spectrum of health workforce research (George et al., 2018).

Table 1.

Inclusion Categories for the Major Workforce Research Topics Included in the Scoping Review, Synthesized From the Review Protocol (Jesus et al., 2021)

| Inclusion Category | Category Type |

|---|---|

| 1 | Workforce supply (e.g., supply of practicing therapists or mapping their profile) |

| 2 | Workforce production (e.g., supply of graduates or entry-level requirements) |

| 3 | Workforce needs, demands, or supply–demand shortages, forecasts |

| 4 | Employment trends (e.g., employment or unemployment patterns, unfilled vacancies) |

| 5 | Workforce distribution (e.g., geographical, practice area, public vs. private sectors) |

| 6 | Geographical mobility (e.g., emigration, immigration; internationally trained workers) |

| 7 | Attractiveness and retention (e.g., salaries, incentives, job satisfaction, intention to leave the profession, recruitment determinants) |

| 8 | Staff management and performance (e.g., human resources management, workload management, managerial recruitment practices, staffing and scheduling, burnout associated with performance or productivity) |

| 9 | Regulation and licensing (e.g., continuing education requirements, task shifting, evaluating the impact of licensing or regulatory changes) |

| 10 | Systems-based or systematic analysis of workforce policies |

Although Table 1 includes workforce production topics (e.g., number of new graduates entering the profession), studies on the education of occupational therapists from a curriculum or pedagogical perspective were excluded. Students contribute to workforce development, but educational research is a gigantic field and a subject on its own; this scoping review focuses on the workforce of those in practice, ready to practice, or in transition from or to practice. Similarly, studies of occupational health (e.g., prevalence of burnout) were excluded, unless they involved explicit human resources practices such as recruitment, retention, or productivity. Revisions of or updates to scope of practice or competency standards were also excluded, unless their development or evaluation is framed as a study (e.g., with a given, replicable methodology).

Methodologically, we included any quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods research, including secondary analyses, case studies, and systematic or scoping reviews, as long as it was published in a peer-reviewed journal or an official institutional venue (e.g., governmental or nongovernmental agencies) at the global, regional, national, or provincial or state level. We planned to review articles available in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. To avoid language restrictions, we also planned to obtain translated versions of documents published in other languages, when available (Jesus et al., 2021), although no such articles emerged in the review process. We excluded editorials, letters, conference abstracts, posters, study protocols, peer-reviewed articles without an abstract, perspective papers, narrative reviews, and broad raw databases or papers that did not address a study question, have replicable methods, or include analysis, interpretation, or implications of the results.

Articles on the occupational therapy workforce or with occupational therapists as participants were included, even if they included other professions or workers—including associate professionals, such as occupational therapy assistants. To be included, however, articles needed to report either comparative or stratified results for occupational therapists. Articles were excluded when the data or results were fully aggregated with those of other health workers.

Using these criteria, two independent reviewers (Jesus and Karthik Mani) conducted title and abstract screening and full-text review to determine eligibility. This process was conducted after the two reviewers reached 80% or greater agreement in pilot tests on at least 5% of the references. For the full-text screening, one or two rounds of discussions were needed for the reviewers to reach consensus on papers rated differently on eligibility. Although we planned to consult a third reviewer to resolve disputes, there was no need to do so.

As defined in the protocol, we reviewed the literature from all geographical areas with no time limitation, but we could have applied a temporal cutoff a posteriori as collectively determined by the authors in the face of saturation (Jesus et al., 2021). We did not apply the temporal cutoff to the eligibility determination, but data extraction was subsequently conducted only for articles published since 1996. In the face of more recent publications, we determined that there was no benefit to extracting and analyzing data from articles published more than 25 yr ago.

Data Extraction

Citation elements such as journal titles and dates were extracted from the reference management software (EndNote). We extracted data relating to methodology or study design, participants (number and type), data sources, data types, study aim or research questions, use of standardized instruments, and use of inferential statistics. Also, we extracted the geographical areas addressed (type and specific location) and the existence of funding support. We conducted a pilot test of the data extraction process with two independent reviewers (Jesus and Mani) for 10% of the included references. Then, one experienced reviewer (Jesus) extracted the information, which was then fully verified by another research author (Mani, Sutanuka Bhattacharjya, or Sureshkumar Kamalakannan). As is typical in scoping reviews (Colquhoun et al., 2020; Peters et al., 2015), quality appraisals were not performed.

Data Synthesis

The findings incorporate a summative description of the extent and range of the literature for the extracted information. For each type of information, we used descriptive statistics, such as percentage of the included studies with a given characteristic (e.g., those who focused on a given country) or grouped characteristics (e.g., those focused on low- and middle-income countries [LMICs]). We also used inclusion categories (see Table 1) to provide the structure to report on the number and percentage of papers per large topic type. To determine the growth trend of publications over the years, we used a simple linear regression analysis with years as the independent variable and number of publications as the dependent variable. The analysis was conducted in Excel, with an add-in for statistical analysis (XLMiner Analysis ToolPak) to compute the simple linear regression. Finally, for the free-text quotations extracted on the aims of each study (i.e., qualitative data), we developed a summative content analysis approach (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) to determine more specific topics addressed by the included studies.

Results

Figure 1 shows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart for this scoping review. Of 1,246 deduplicated articles initially assessed for eligibility, 141 were subject to full-text review, and 78 met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 57 articles were published after the temporal cutoff (i.e., they had been published since 1996). We extracted and analyzed data from these publications.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart for the selection of studies for the scoping review.

Note. Figure format from “The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews,” by M. J. Page, J. E. McKenzie, P. M. Bossuyt, I. Boutron, T. C. Hoffmann, C. D. Mulrow, . . . D. Moher, 2021, BMJ, 372, 71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

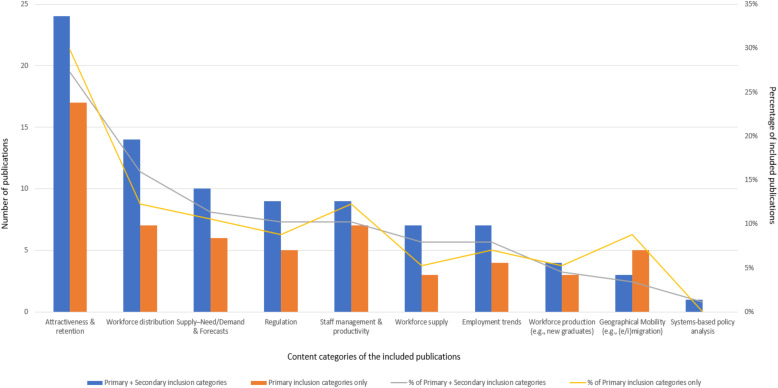

Figure 2 provides the distribution of articles for the primary category alone and for both primary and secondary categories combined. The categories of “attractiveness and retention” and “workforce distribution” were those most frequently addressed as a primary or secondary topic, at 27% and 16% of the occurrences, respectively.

Figure 2.

Distribution of articles in each inclusion category.

Table A.1 in the Supplemental Appendix (available online with this article at https://research.aota.org/ajot) provides the key data extracted from each article by primary inclusion category. A total of 28 papers (49%) met more than one inclusion category.

The scope of the literature is summarized next, using various categories of analysis.

Annual Volume and Growth

An analysis of the annual volume and growth of occupational therapy workforce research indicated an erratic evolving trend (r2 = .26), with no more than 7 articles published worldwide in a single year and, in some recent years (2011, 2012, 2016, 2017), fewer than two publications per year. Although we found a statistically significant growth trend for the total number of articles published each year (p < .01), the slope of the linear regression model (b = 0.07) indicates that it will take 14 yr to increase the annual publication rate by one additional article.

Study Design

Cross-sectional surveys accounted for most of the publications (n = 30; 53%), and secondary analyses (n = 10), qualitative research (n = 5), and systematic reviews (n = 4) accounted for 18%, 9%, and 7% of the included articles, respectively. Three studies had unique study designs, which included 1 pilot experiment study (Rodger, Thomas, et al., 2009).

Participants

A total of 5,813 occupational therapy participants were directly involved in the primary research (i.e., excluding systematic reviews and secondary analyses of databases). Among the articles included, 75% (n = 43) focused only on occupational therapists, whereas 25% (n = 14) included data from occupational therapists compared with or disaggregated from other types of health workers.

Geographical Areas

A total of 9% (n = 5) of the articles had a transnational or worldwide focus. Most focused on specific countries, either the country overall (58%; n = 33) or a region, province, or state (18%; n = 10); rural or remote area (9%; n = 5); or metropolitan area of a given country (7%; n = 4). Among the articles focused on specific countries (n = 52), Australia accounted for 31% (n = 16), followed by the United States (30%; n =15), Canada (12%; n = 5), and the United Kingdom (6%; n = 3). Four articles addressed LMICs: two for Brazil and 1 each for India and South Africa, for a total of 7% of included articles. One additional article (2%) addressed the anglophone sub-Saharan Africa as a resource-poor global region.

Publication Venue

All of the articles except 1 were published in peer-reviewed journals. Aligned with the geographical focus, the Australian Occupational Therapy Journal was the publication venue for 24% (n = 13) of the peer-reviewed publications; the American Journal of Occupational Therapy published the second highest number of peer-reviewed articles (9%; n = 5). In total, most peer-reviewed articles (57%) were published in occupational therapy journals. Among the articles published in non–occupational therapy journals, the most common choice for publication was Human Resources for Health (6%; n = 3).

Sources of Data or Participants

The sources of data or methods for recruiting participants were diverse. For example, 19% (n = 11) of the included articles used data sourced from licensing or registration bodies, and 12% (n = 7) used data from national associations. A greater percentage of articles (25%; n = 14) used more than two sources to obtain data or recruit participants.

Study Question Type, Data Collection Tools, and Data Analysis

A total of 77% (n = 44) of articles focused on either descriptive or exploratory research questions, and 23% percent (n = 13) addressed an analytical type of question (e.g., determining statistical associations, predicting supply–demand shortages, examining the impact of a new policy or intervention); 2% (n = 1) explicitly tested a hypothesis.

Aligned with these findings, 10% of the eligible articles (i.e., excluding qualitative research and systematic reviews) used standardized tools; 39% of articles with quantitative data applied inferential statistics during the analysis.

Funding Status

A total of 70% of papers (n = 40) reported no form of funding support. Altogether, 21% of articles (n = 12) reported external funding. Four percent (n = 2) used intramural funding, and 5% (n = 3) reported funding support for specific authors (i.e., not for the specific research project or program).

Of the 17 articles reporting funding, one was a cross-sectional survey study with an exploratory study question (6%), in contrast to the articles without funding (n = 40), which relied heavily on cross-sectional survey studies and exploratory study questions (53%; n = 21). Sixty-five percent of the funded articles used inferential statistics compared with 20% of the unfunded articles (i.e., 8 of 40).

A total of 47% of the articles reporting funding (i.e., 8 of 17) focused on data for both occupational therapists and other workers. In turn, 88% of the 40 nonfunded articles (n = 35) used data for occupational therapists only and thereby were less able to establish cross-professional comparisons.

Content Analysis of Specific Topics

A qualitative analysis of the study aims of the articles included in this scoping review identified common topics for occupational therapy workforce research.

Seven articles addressed workforce attractiveness and retention in mental health (Ceramidas et al., 2009; Hunter & Nicol, 2002; Rodger, Thomas, et al., 2009; Scanlan et al., 2013; Scanlan & Still, 2013; Scanlan & Still, 2019; Scanlan et al., 2010), including 4 articles that had the same first author. In turn, 5 Australian articles addressed the issues of attractiveness and retention specifically in rural or remote areas (McAuliffe & Barnett, 2009, 2010; Merritt et al., 2013; Mills & Millsteed, 2002; Millsteed, 2000).

Among other topics addressed by workforce studies, 4 articles focused on continuing professional development behaviors and licensing requirements (Fields et al., 2021; Hall et al., 2016; Vachon et al., 2018; White, 2005); 4 studies from the United States determined that there were workforce shortages or surplus based on supply and demand data (HRSA Health Workforce, 2016; Lin et al., 2015; Powell et al., 2005, 2008), and 3 focused on variation in employment and staffing levels in skilled nursing facilities in the context of reimbursement policy changes in the United States (McGarry et al., 2021; Mroz et al., 2021; Prusynski et al., 2021).

Finally, 3 articles focused on internationally trained occupational therapists, including 2 from Canada that investigated workforce integration (Dhillon et al., 2019; Mulholland et al., 2013; Pittman et al., 2014). No other topics were addressed by more than 2 articles.

Discussion

This scoping review highlights the global status of occupational therapy workforce research worldwide. Our results show a limited volume of such research, with weak growth over time, little focus on LMICs, a restricted breadth of topics, an overreliance on exploratory cross-sectional surveys, the limited use of inferential statistics, a lack of experimental studies, and low rates of funding support. Furthermore, the review indicates that the studies with funding support tended to use stronger methodology. All of these findings are worthy of discussion.

The findings revealed a low volume of occupational therapy workforce research, coupled with weak annual growth (i.e., 14 yr to add one additional yearly publication; 2011 and 2012 without a single publication), especially when compared with other health workforce research. As many as 867 research articles were found for health workforce research topics in 2018 alone, with a significant and exponential type of growth over time from 129 yearly publications in 1990 to nearly 900 in 2018 alone (Jesus, Castellini, et al., 2022). In volume and growth, occupational therapy workforce research production lags behind expectations.

A few examples of commonly researched topics were found, including career attractiveness and retention issues (e.g., mental health as a practice area, practicing in rural areas) with studies in this area coming predominantly from Australia. Determining supply–demand shortages and the impact of changed reimbursement policies on reduced staffing and employment levels were study topics that came exclusively from the United States. In turn, Canada was the country with primary research articles studying internationally trained occupational therapists.

It is possible that country-specific policies, culture, or the overall landscape of research and its funding have shaped these country-specific patterns of occupational therapy workforce research. For example, studies and research structures for studying or forecasting workforce shortages for varied health professions are common in the United States (Juraschek et al., 2019; Landry et al., 2016; Ricketts et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2018, 2020; Zimbelman et al., 2010). Similarly, supplying rural and remote areas of the country with a needed and capable health workforce is a major policy, research, and research policy priority in Australia (Gillam et al., 2021; Russell et al., 2021; Wakerman et al., 2019). Finally, the Canadian studies on internationally educated occupational therapists were funded with sponsorship of governmental bodies in two provinces focused on employment and immigration issues (Dhillon et al., 2019; Mulholland et al., 2013).

Overall, the trends identified in this scoping review may be derived more from country-specific policies, research, or funding priorities than from any particularly needed occupational therapy–specific workforce topics prevalent across nations. Unlike for other health professions, such as nursing (WHO, 2016a), no global guidance exists for the development of occupational therapy human resources and workforce research. As a result of these findings, the WFOT aims to use a research- and consultation-based process to develop a strategy to provide such guidance.

The rates for funding of workforce research found in this review were not remarkable. Only 30% of included articles reported any form of funding (25%, if funding that supported only individual authors is excluded). These values differ from funding levels usually identified for health workforce research. Since 2010, the percentage of health workforce research with funding support has been stable at approximately 50% (Jesus, Castellini, et al., 2022), with rehabilitation- related health policy, systems, and services research receiving funding support at a level of 55% (Jesus et al., 2020). These findings help explain, in part, a suboptimal application of more advanced or stronger research designs and methods in the occupational therapy workforce literature. Funding occupational therapy workforce research at more standard rates will likely improve both the quantity and the quality of the methods used in occupational therapy workforce research and thereby provide a stronger evidence base for professional advocacy and workforce developments.

Of the 57 included articles, 7% focused on LMICs, which contrasts with the 77% of the world’s rehabilitation needs coming from LMICs (Jesus et al., 2019). Although this is a common problem in other areas of health research (i.e., LMICs account for about 12% of rehabilitation-related health policy, systems, and services research; Jesus et al., 2020), the low volume of research on LMICs may raise global public health concerns.

Existing data indicate scant, limited, or nonexistent occupational therapy workforces or education programs in many LMICs (Agho & John, 2017; Ledgerd & WFOT, 2020). Models of service delivery and workforce supply to feasibly meet the health and occupational needs of their populations might differ in many LMICs. Hence, there is a strong need to develop and study efficient and feasible means to develop the workforce in these contexts. This review, however, shows that occupational therapy workforce research rarely tackles issues in LMIC contexts.

We found that only 9% of the included articles had a cross-country focus, which prevents cross-national comparisons, benchmarks, partnerships, or knowledge exchange on the so-called North–North (Jesus, Landry, et al., 2022), South–South (Were et al., 2019), and North–South (Mwangi et al., 2017) partnerships on workforce research and developments (here North equates to high-income nations and South to LMICs).

Greater cross-national partnerships for occupational therapy workforce research have the potential to address existing issues with the lack of data on the international mobility of occupational therapists. Also, we found no studies directly looking at the international recruitment of occupational therapists or on the ethical issues that may arise from such recruitment (WFOT, 2014).

Limitations of this scoping review include the lack of inclusion of research on the education of occupational therapists, despite the key importance of education for the development of the profession. We included workforce research (i.e., with a study question and reported methodology) but not other forms of reports or databases with workforce data. This choice reflects a focus on knowledge generation beyond data generation. We did not search the ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global database because our focus was on studies published in the peer-reviewed literature or in institutional venues such as governmental or nongovernmental agencies. Although we did not have language restrictions on eligibility and used diverse search strategies (including key informants from diverse countries), we were unable to map literature in languages other than English. As a result, underrepresentation of literature from geographical areas using languages other than English in reporting research cannot be ruled out. Finally, we did not focus on reporting the findings, recommendations, and limitations that are a subject for other reports on this study (Jesus, Mani, Ledgerd, et al., 2022; Jesus, Mani, von Zweck, et al., 2022).

Implications for Occupational Therapy Practice

This scoping review uncovered the global status of occupational therapy workforce research worldwide and highlights the need for it to be strengthened. It has the following implications for occupational therapy practices:

▪ Occupational therapy stakeholders such as those in practice, academia, research funding, and policy and professional advocacy roles may collaborate (at the global, country, and regional levels) to develop systemic, strategic, and methodologically stronger occupational therapy workforce research agendas. These agendas may provide a more solid body of research and evidence to identify and address workforce gaps and thereby promote equitable population access to competent occupational therapy services.

▪ Funders of occupational therapy research or of health policy, systems, and services research may support funding (e.g., earmark a percentage of funds) for occupational therapy workforce research to align with funding of other health human resources research. This advancement is likely to strengthen the quantity, methods, and value of occupational therapy workforce research and evidence to inform everyday professional advocacy and workforce development practices.

Conclusion

Occupational therapy workforce research is key in providing evidence regarding whether and how the occupational therapy workforce exists in sufficient quantity, is equitably distributed, and meets key competency standards. The results of this scoping review map the global status of occupational therapy workforce research, which was found to be scant, barely growing, and inequitably distributed by geographical area; to use suboptimal methods; and to be underfunded, with stronger methods for the studies that were funded.

Apart from a few examples of research topics, mostly country specific, we could not find long-term research programs or agendas for the systematic study of the occupational therapy workforce. Doing so may be necessary to generate an evidence base for guiding and assessing occupational therapy workforce policies, advocacy, and development practices.

According to gaps identified in this review, concerted stakeholder development is required to strengthen funding mechanisms, provide guidance on topics and research questions to be addressed, and enhance the methodology of the occupational therapy workforce research within and across nations.

To align with strategic directions for health human resources (WHO, 2016b) and for specific health professions such as the nursing workforce (WHO, 2016a), there is a need to develop a global strategy and research agenda to strengthen the status of occupational therapy workforce research. The WFOT is planning to develop such a strategic guidance at the global level.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the WFOT delegates and other member organization representatives who suggested papers for inclusion in this scoping review. Tiago S. Jesus completed this work under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR; 90ARHF0003). NIDILRR is a center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this publication do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and the reader should not assume endorsement by the U.S. federal government.

Footnotes

Indicates articles included in the scoping review.

References

- *Agho, A. O., & John, E. B. (2017). Occupational therapy and physiotherapy education and workforce in Anglophone sub-Saharan Africa countries. Human Resources for Health , 15, 37. 10.1186/s12960-017-0212-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajuebor, O., McCarthy, C., Li, Y., Al-Blooshi, S. M., Makhanya, N., & Cometto, G. (2019). Are the Global Strategic Directions for Strengthening Nursing and Midwifery 2016–2020 being implemented in countries? Findings from a cross-sectional analysis. Human Resources for Health , 17, 54. 10.1186/s12960-019-0392-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Al-Senaani, F., Salawati, M., AlJohani, M., Cuche, M., Seguel Ravest, V., & Eggington, S. (2019). Workforce requirements for comprehensive ischaemic stroke care in a developing country: The case of Saudi Arabia. Human Resources for Health , 17, 90. 10.1186/s12960-019-0408-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy in the promotion of health and well-being. American Journal of Occupational Therapy , 74, 7403420010. 10.5014/ajot.2020.743003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology , 8, 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailliard, A. L., Dallman, A. R., Carroll, A., Lee, B. D., & Szendrey, S. (2020). Doing occupational justice: A central dimension of everyday occupational therapy practice. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy , 87, 144–152. 10.1177/0008417419898930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Brown, G. T. (1998). Male occupational therapists in Canada: A demographic profile. British Journal of Occupational Therapy , 61, 561–567. 10.1177/030802269806101208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan, J., Campbell, J., & McCarthy, C. (2020). Research to support evidence-informed decisions on optimizing the contributions of nursing and midwifery workforces. Human Resources for Health , 18, 23. 10.1186/s12960-020-0459-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J. (2013). Towards universal health coverage: A health workforce fit for purpose and practice. Bulletin of the World Health Organization , 91, 887–888. 10.2471/BLT.13.126698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J., Buchan, J., Cometto, G., David, B., Dussault, G., Fogstad, H., . . . Tangcharoensathien, V. (2013). Human resources for health and universal health coverage: Fostering equity and effective coverage. Bulletin of the World Health Organization , 91, 853–863. 10.2471/BLT.13.118729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Ceramidas, D., de Zita, C. F., Eklund, M., & Kirsh, B. (2009). The 2009 world team of mental health occupational therapists: A resilient and dedicated workforce. WFOT Bulletin , 60, 9–17. 10.1179/otb.2009.60.1.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Chun, B. Y., & Song, C. S. (2020). A moderated mediation analysis of occupational stress, presenteeism, and turnover intention among occupational therapists in Korea. Journal of Occupational Health , 62, e12153. 10.1002/1348-9585.12153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun, H. L., Jesus, T. S., O’Brien, K. K., Tricco, A. C., Chui, A., Zarin, W., . . . Straus, S. E. (2020). Scoping review on rehabilitation scoping reviews. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation , 101, 1462–1469. 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun, H. L., Levac, D., O’Brien, K. K., Straus, S., Tricco, A. C., Perrier, L., . . . Moher, D. (2014). Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology , 67, 1291–1294. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daudt, H. M., van Mossel, C., & Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology , 13, 48. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *De Boer, M. E., Leemrijse, C. J., Van Den Ende, C. H., Ribbe, M. W., & Dekker, J. (2007). The availability of allied health care in nursing homes. Disability and Rehabilitation , 29, 665–670. 10.1080/09638280600926561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *de Oliveira, M. L., do Pinho, R. J., & Malfitano, A. P. S. (2019). Occupational therapists inclusion in the “Sistema Unico de Assistencia Social” (Brazilian Social Police System): official records on our route. Brazilian Journal of Occupational Therapy , 27, 828–842. [Google Scholar]

- *Dhillon, S., Dix, L., Baptiste, S., Moll, S., Stroinska, M., & Solomon, P. (2019). Internationally educated occupational therapists transitioning to practice in Canada: A qualitative study. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal , 66, 274–282. 10.1111/1440-1630.12541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Dodds, K., & Herkt, J. (2013). Exploring transition back to occupational therapy practice following a career break. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy , 60, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- *Ferguson, M., & Rugg, S. (2000). Advertising for and recruiting basic grade occupational therapists in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Occupational Therapy , 63, 583–590. 10.1177/030802260006301205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Fields, S. M., Unsworth, C. A., & Harreveld, B. (2021). The revision of competency standards for occupational therapy driver assessors in Australia: A mixed methods approach. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal , 68, 257–271. 10.1111/1440-1630.12722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George, A. S., Campbell, J., & Ghaffar, A.; HPSR HRH Reader Collaborators. (2018). Advancing the science behind human resources for health: Highlights from the Health Policy and Systems Research Reader on Human Resources for Health. Health Research Policy and Systems , 16, 80. 10.1186/s12961-018-0346-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillam, M. H., Jones, M., & May, E. (2021). Beyond the black stump: Rapid reviews of health research issues affecting regional, rural and remote Australia. Medical Journal of Australia , 215, 141–141.e1. 10.5694/mja2.51167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimigliano, F., & Negrini, S. (2017). The World Health Organization “Rehabilitation 2030: a call for action.” European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine , 53, 155–168. 10.23736/S1973-9087.17.04746-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Haddad, A. E., Morita, M. C., Pierantoni, C. R., Brenelli, S. L., Passarella, T., & Campos, F. E. (2010). Undergraduate programs for health professionals in Brazil: An analysis from 1991 to 2008. Revista de Saude Publica , 44, 385–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hall, S. R., Crifasi, K. A., Marinelli, C. M., & Yuen, H. K. (2016). Continuing education requirements among state occupational therapy regulatory boards in the United States of America. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions , 13, 37. 10.3352/jeehp.2016.13.37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hitch, D., Lhuede, K., Giles, S., Low, R., Cranwell, K., & Stefaniak, R. (2020). Perceptions of leadership styles in occupational therapy practice. Leadership in Health Services , 33, 295–306. 10.1108/LHS-11-2019-0074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *HRSA Health Workforce. (2016). Allied health workforce projections, 2016–2030: Occupational and physical therapists. Health Resources & Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research , 15, 1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hunter, E., & Nicol, M. (2002). Systematic review: Evidence of the value of continuing professional development to enhance recruitment and retention of occupational therapists in mental health. British Journal of Occupational Therapy , 65, 207–215. 10.1177/030802260206500504 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jesus, T. S., Castellini, G., & Gianola, S. (2022). Global health workforce research: Comparative analyses of the scientific publication trends in PubMed. International Journal of Health Planning and Management , 37, 1351–1365. 10.1002/hpm.3401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesus, T. S., Hoenig, H., & Landry, M. D. (2020). Development of the rehabilitation health policy, systems, and services research field: Quantitative analyses of publications over time (1990-2017) and across country type. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 17, 965. 10.3390/ijerph17030965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesus, T. S., Landry, M. D., Dussault, G., & Fronteira, I. (2017). Human resources for health (and rehabilitation): Six rehab-workforce challenges for the century. Human Resources for Health , 15, 8. 10.1186/s12960-017-0182-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesus, T. S., Landry, M. D., & Hoenig, H. (2019). Global need for physical rehabilitation: Systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 16, 980. 10.3390/ijerph16060980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesus, T. S., Landry, M. D., Hoenig, H., Dussault, G., Koh, G. C., & Fronteira, I. (2022). Is physical rehabilitation need associated with the rehabilitation workforce supply? An ecological study across 35 high-income countries. International Journal of Health Policy and Management , 11, 434–442. 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesus, T. S., Mani, K., Ledgerd, R., Kamalakannan, S., Bhattacharjya, S., & von Zweck, C.; World Federation of Occupational Therapists. (2022). Limitations and recommendations for advancing the occupational therapy workforce research worldwide: Scoping review and content analysis of the literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 19, 7327. 10.3390/ijerph19127327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesus, T. S., Mani, K., von Zweck, C., Kamalakannan, S., Bhattacharjya, S., & Ledgerd, R.; on behalf of the World Federation of Occupational Therapists. (2022). Type of findings generated by the occupational therapy workforce research worldwide: Scoping review and content analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 19, 5307. 10.3390/ijerph19095307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesus, T. S., von Zweck, C., Mani, K., Kamalakannan, S., Bhattacharjya, S., & Ledgerd, R.; World Federation of Occupational Therapists. (2021). Mapping the occupational therapy workforce research worldwide: Study protocol for a scoping review. Work , 70, 677–686. 10.3233/WOR-210777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Josi, R., & De Pietro, C. (2019). Skill mix in Swiss primary care group practices: A nationwide online survey. BMC Family Practice , 20, 39. 10.1186/s12875-019-0926-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juraschek, S. P., Zhang, X., Ranganathan, V., & Lin, V. W. (2019). United States registered nurse workforce report card and shortage forecast. American Journal of Medical Quality , 34, 473–481. 10.1177/1062860619873217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Katz, N., Gilad Izhaky, S., & Dror, Y. F. (2013). Reasons for choosing a career and workplace among occupational therapists and speech language pathologists. Work , 45, 343–348. 10.3233/WOR-121532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kobbero, T. K., Lynch, C. H., Boniface, G., & Forwell, S. J. (2018). Occupational therapy private practice workforce: Issues in the 21st century. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy , 85, 58–65. 10.1177/0008417417719724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann, E., Batenburg, R., Wismar, M., Dussault, G., Maier, C. B., Glinos, I. A., . . . Ungureanu, M. (2018). A call for action to establish a research agenda for building a future health workforce in Europe. Health Research Policy and Systems , 16, 52. 10.1186/s12961-018-0333-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry, M. D., Hack, L. M., Coulson, E., Freburger, J., Johnson, M. P., Katz, R., . . . Goldstein, M. (2016). Workforce projections 2010-2020: Annual supply and demand forecasting models for physical therapists across the United States. Physical Therapy , 96, 71–80. 10.2522/ptj.20150010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Ledgerd, R., & World Federation of Occupational Therapists. (2020). WFOT report: WFOT human resources project 2018 and 2020. World Federation of Occupational Therapists Bulletin , 76(2), 69–74. 10.1080/14473828.2020.1821475 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science , 5, 69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Lin, V., Zhang, X., & Dixon, P. (2015). Occupational therapy workforce in the United States: Forecasting nationwide shortages. PM & R , 7, 946–954. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Lysaght, R. M., Altschuld, J. W., Grant, H. K., & Henderson, J. L. (2001). Variables affecting the competency maintenance behaviors of occupational therapists. American Journal of Occupational Therapy , 55, 28–35. 10.5014/ajot.55.1.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Maass, R., Bonsaksen, T., Gramstad, A., Sveen, U., Stigen, L., Arntzen, C., & Horghagen, S. (2021). Factors associated with the establishment of new occupational therapist positions in Norwegian municipalities after the coordination reform. Health Services Insights , 14, 1178632921994908. 10.1177/1178632921994908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Mani, K., & Sundar, S. (2019). Occupational therapy workforce in India: A national survey. Indian Journal of Occupational Therapy , 51, 45–51. 10.4103/ijoth.ijoth_1_19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *McAuliffe, T., & Barnett, F. (2009). Factors influencing occupational therapy students’ perceptions of rural and remote practice. Rural and Remote Health , 9(1), 1078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *McAuliffe, T., & Barnett, F. (2010). Perceptions towards rural and remote practice: A study of final year occupational therapy students studying in a regional university in Australia. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal , 57, 293–300. 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2009.00838.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *McBain, R. K., Kareddy, V., Cantor, J. H., Stein, B. D., & Yu, H. (2020). Systematic Review: United States workforce for autism-related child healthcare services. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , 59, 113–139. 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *McGarry, B. E., White, E. M., Resnik, L. J., Rahman, M., & Grabowski, D. C. (2021). Medicare’s new patient driven payment model resulted in reductions in therapy staffing in skilled nursing facilities. Health Affairs , 40, 392–399. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan, J., Sampson, M., Salzwedel, D. M., Cogo, E., Foerster, V., & Lefebvre, C. (2016). PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 guideline statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology , 75, 40–46. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *McHugh, G., & Swain, I. D. (2014). A comparison between reported therapy staffing levels and the Department of Health therapy staffing guidelines for stroke rehabilitation: A national survey. BMC Health Services Research , 14, 216. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Meade, I., Brown, G. T., & Trevan-Hawke, J. (2005). Female and male occupational therapists: A comparison of their job satisfaction level. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal , 52, 136–148. 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2005.00480.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Merritt, J., Perkins, D., & Boreland, F. (2013). Regional and remote occupational therapy: A preliminary exploration of private occupational therapy practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal , 60, 276–287. 10.1111/1440-1630.12042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Mills, A., & Millsteed, J. (2002). Retention: An unresolved workforce issue affecting rural occupational therapy services. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal , 49, 170–181. 10.1046/j.1440-1630.2002.00293.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mills, J. A., Cieza, A., Short, S. D., & Middleton, J. W. (2021). Development and validation of the WHO Rehabilitation Competency Framework: A mixed methods study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation , 102, 1113–1123. 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.10.129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Millsteed, J. (2000). Issues affecting Australia’s rural occupational therapy workforce. Australian Journal of Rural Health , 8, 73–76. 10.1046/j.1440-1584.2000.00245.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Mroz, T. M., Dahal, A., Prusynski, R., Skillman, S. M., & Frogner, B. K. (2021). Variation in employment of therapy assistants in skilled nursing facilities based on organizational factors. Medical Care Research and Review , 78(1, Suppl.), 40S–46S. 10.1177/1077558720952570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Mueller, E., Arthur, P., Ivy, M., Pryor, L., Armstead, A., & Li, C. Y. (2021). Addressing the gap: Occupational therapy in hospice care. Occupational Therapy in Health Care , 35, 125–137. 10.1080/07380577.2021.1879410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Mulholland, S., & Derdall, M. (2005). Exploring recruitment strategies to hire occupational therapists. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy , 72, 37–44. 10.1177/000841740507200109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Mulholland, S. J., Dietrich, T. A., Bressler, S. I., & Corbett, K. G. (2013). Exploring the integration of internationally educated occupational therapists into the workforce. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy , 80, 8–18. 10.1177/0008417412472653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwangi, N., Zondervan, M., & Bascaran, C. (2017). Analysis of an international collaboration for capacity building of human resources for eye care: Case study of the college-college VISION 2020 LINK. Human Resources for Health , 15, 22 10.1186/s12960-017-0196-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Ned, L., Tiwari, R., Buchanan, H., Van Niekerk, L., Sherry, K., & Chikte, U. (2020). Changing demographic trends among South African occupational therapists: 2002 to 2018. Human Resources for Health , 18, 22. 10.1186/s12960-020-0464-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Nelson, H., Giles, S., McInnes, H., & Hitch, D. (2015). Occupational therapists’ experiences of career progression following promotion. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal , 62, 401–409. 10.1111/1440-1630.12207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C. D., . . . Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ , 372, 71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M. D., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare , 13, 141–146. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., . . . Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis , 18, 2119–2126. 10.11124/JBIES-20-00167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., . . . Khalil, H. (2021). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation , 19, 3–10. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Pittman, P., Frogner, B., Bass, E., & Dunham, C. (2014). International recruitment of allied health professionals to the United States: Piecing together the picture with imperfect data. Journal of Allied Health , 43, 79–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Porter, S., & Lexén, A. (2022). Swedish occupational therapists’ considerations for leaving their profession: Outcomes from a national survey. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy , 29, 79–88. 10.1080/11038128.2021.1903992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Powell, J. M., Griffith, S. L., & Kanny, E. M. (2005). Occupational therapy workforce needs: A model for demand-based studies. American Journal of Occupational Therapy , 59, 467–474. 10.5014/ajot.59.4.467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Powell, J. M., Kanny, E. M., & Ciol, M. A. (2008). State of the occupational therapy workforce: Results of a national study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy , 62, 97–105. 10.5014/ajot.62.1.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Prusynski, R. A., Leland, N. E., Frogner, B. K., Leibbrand, C., & Mroz, T. M. (2021). Therapy staffing in skilled nursing facilities declined after implementation of the patient-driven payment model. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association , 22, 2201–2206. 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Randolph, D. S. (2005). Predicting the effect of extrinsic and intrinsic job satisfaction factors on recruitment and retention of rehabilitation professionals. Journal of Healthcare Management , 50, 49–60. 10.1097/00115514-200501000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts, T. C., Porterfield, D. S., Miller, R. L., & Fraher, E. P. (2021). The supply and distribution of the preventive medicine physician workforce. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice , 27(Suppl. 3), S116–S122. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Rodger, S., Clark, M., Banks, R., O’Brien, M., & Martinez, K. (2009). A national evaluation of the Australian Occupational Therapy Competency Standards (1994): A multistakeholder perspective. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal , 56, 384–392. 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2009.00794.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Rodger, S., Thomas, Y., Holley, S., Springfield, E., Edwards, A., Broadbridge, J., . . . Hawkins, R. (2009). Increasing the occupational therapy mental health workforce through innovative practice education: A pilot project. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal , 56, 409–417. 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2009.00806.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, D., Mathew, S., Fitts, M., Liddle, Z., Murakami-Gold, L., Campbell, N., . . . Wakerman, J. (2021). Interventions for health workforce retention in rural and remote areas: A systematic review. Human Resources for Health , 19, 103. 10.1186/s12960-021-00643-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Salsberg, E., Richwine, C., Westergaard, S., Portela Martinez, M., Oyeyemi, T., Vichare, A., & Chen, C. P. (2021). Estimation and comparison of current and future racial/ethnic representation in the US health care workforce. JAMA Network Open , 4, e213789. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.3789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Scanlan, J. N., Meredith, P., & Poulsen, A. A. (2013). Enhancing retention of occupational therapists working in mental health: Relationships between wellbeing at work and turnover intention. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal , 60, 395–403. 10.1111/1440-1630.12074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Scanlan, J. N., & Still, M. (2013). Job satisfaction, burnout and turnover intention in occupational therapists working in mental health. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal , 60, 310–318. 10.1111/1440-1630.12067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Scanlan, J. N., & Still, M. (2019). Relationships between burnout, turnover intention, job satisfaction, job demands and job resources for mental health personnel in an Australian mental health service. BMC Health Services Research , 19, 62. 10.1186/s12913-018-3841-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Scanlan, J. N., Still, M., Stewart, K., & Croaker, J. (2010). Recruitment and retention issues for occupational therapists in mental health: Balancing the pull and the push. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal , 57, 102–110. 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2009.00814.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrata Malfitano, A. P., Gomes da Mota de Souza, R., & Esquerdo Lopes, R. (2016). Occupational justice and its related concepts: An historical and thematic scoping review. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health , 36, 167–178. 10.1177/1539449216669133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Smith, T., Cooper, R., Brown, L., Hemmings, R., & Greaves, J. (2008). Profile of the rural allied health workforce in northern New South Wales and comparison with previous studies. Australian Journal of Rural Health , 16, 156–163. 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2008.00966.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Summers, B. E., Laver, K. E., Nicks, R. J., & Lannin, N. A. (2018). What factors influence time-use of occupational therapists in the workplace? A systematic review. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal , 65, 225–237. 10.1111/1440-1630.12466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., . . . Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine , 169, 467–473. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Vachon, B., Foucault, M. L., Giguère, C. É., Rochette, A., Thomas, A., & Morel, M. (2018). Factors influencing acceptability and perceived impacts of a mandatory eportfolio implemented by an occupational therapy regulatory organization. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions , 38, 25–31. 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakerman, J., Humphreys, J., Russell, D., Guthridge, S., Bourke, L., Dunbar, T., . . . Jones, M. P. (2019). Remote health workforce turnover and retention: What are the policy and practice priorities? Human Resources for Health , 17, 99. 10.1186/s12960-019-0432-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Were, V., Jere, E., Lanyo, K., Mburu, G., Kiriinya, R., Waudo, A., . . . Rodgers, M. (2019). Success of a south-south collaboration on Human Resources Information Systems (HRIS) in health: A case of Kenya and Zambia HRIS collaboration. Human Resources for Health , 17, 6. 10.1186/s12960-019-0342-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *White, E. (2005). Continuing professional development: The impact of the College of Occupational Therapists’ standard on dedicated time. British Journal of Occupational Therapy , 68, 196–201. 10.1177/030802260506800502 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Wilson, R. D., Lewis, S. A., & Murray, P. K. (2009). Trends in the rehabilitation therapist workforce in underserved areas: 1980–2000. Journal of Rural Health , 25, 26–32. 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00195.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Federation of Occupational Therapists. (2013). Definitions of occupational therapy from member organizations https://wfot.org/resources/definitions-of-occupational-therapy-from-member-organisations

- World Federation of Occupational Therapists. (2014). Recruiting occupational therapists from international communities. https://www.wfot.org/resources/recruiting-occupational-therapists-from-international-communities

- World Federation of Occupational Therapists. (2019). Occupational therapy and human rights (Rev.). [Google Scholar]

- World Federation of Occupational Therapists. (2021). Occupational therapy human resources: Policies, planning, and research. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2006). Working together for health: The World Health report. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2016a). The global strategic directions for strengthening nursing and midwifery, 2016–2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2016b). Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., Lin, D., Pforsich, H., & Lin, V. W. (2020). Physician workforce in the United States of America: Forecasting nationwide shortages. Human Resources for Health , 18, 8. 10.1186/s12960-020-0448-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., Tai, D., Pforsich, H., & Lin, V. W. (2018). United States registered nurse workforce report card and shortage forecast: A revisit. American Journal of Medical Quality , 33, 229–236. 10.1177/1062860617738328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimbelman, J. L., Juraschek, S. P., Zhang, X., & Lin, V. W. (2010). Physical therapy workforce in the United States: Forecasting nationwide shortages. PM & R , 2, 1021–1029. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.