Abstract

The integration of mechanically interlocked molecules (MIMs) into purely organic crystalline materials is expected to produce materials with properties that are not accessible using more classic approaches. To date, this integration has proved elusive. We present a dative boron–nitrogen bond-driven self-assembly strategy that allows for the preparation of polyrotaxane crystals. The polyrotaxane nature of the crystalline material was confirmed by both single-crystal x-ray diffraction analysis and cryogenic high-resolution low-dose transmission electron microscopy. Enhanced softness and greater elasticity are seen for the polyrotaxane crystals than for nonrotaxane polymer controls. This finding is rationalized in terms of the synergetic microscopic motion of the rotaxane subunits. The present work thus highlights the benefits of integrating MIMs into crystalline materials.

A dative boron–nitrogen bond-driven self-assembly strategy allows the preparation of polyrotaxane crystals.

INTRODUCTION

Mechanically interlocked molecules (MIMs) (1, 2) are topological structures containing two or more components that are held together by mechanical bonds. Typically, MIMs have a high degree of conformational freedom and display considerable intrastructural motion (3–6). The integration of MIMs, including rotaxanes and catenanes, into polymers is expected to produce new materials with exotic properties (7–10). However, the development of MIM-based polymer crystals, bulk systems precisely controlled at the molecular level, has been restricted by the random distribution and incoherent motion of the associated MIM components in solution and in amorphous phases (11–13). To date, metal coordination has been explored in an effort to overcome these limitations; it has allowed for the construction of various crystalline mechanically interlocked polymers (MIPs) and metal-organic rotaxane frameworks (MORFs) (14, 15). However, the preparation of MIPs or MORFs generally requires the use of metal ions as the nodes, which can lead to high regeneration costs and a lack of biocompatibility (16–19). The potential benefits of an alternative approach, involving integrating MIMs into purely organic crystalline polymer materials, have been noted on several occasions (20–22). These include inter alia lower density, a lack of heavy metal toxicity, improved environmental responsiveness, and higher overall flexibility. These perceived advantages notwithstanding, to our knowledge, the challenge of preparing purely organic crystalline MIM-integrated polymer materials have yet to be met. Presumably, this reflects the fact that crystallization of purely organic polymer backbones is difficult, and the presence of dynamic MIMs might further compound efforts at crystallization (20). Here, we report a crystalline polymeric polyrotaxane system based on dative boron–nitrogen (B─N) bonds that exists as a zigzag conformer when recrystallized from benzene but adopts a double-stranded helical structure when isolated from o-dichlorobenzene (Fig. 1). The forms display different bulk materials properties and can be readily interconverted via solvent exchange.

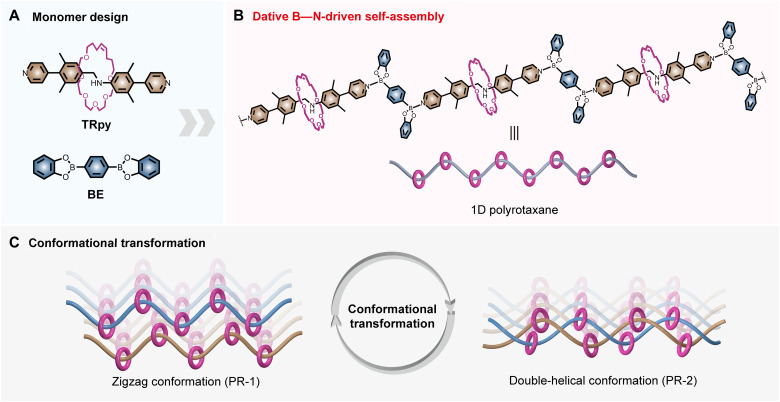

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the design and concept of polyrotaxanes.

(A) Chemical structures of monomers TRpy (pyridine end-modified [2]rotaxane building block) and bis(dioxaborole) (BE). (B) Formation of the polyrotaxanes via dative boron–nitrogen (B─N) bonds. 1D, one-dimensional. (C) Cartoon view of the conformational transformation between limiting polyrotaxane forms.

A key design element allowing access to the present ordered polyrotaxane material is the use of dative B─N bonds. These bonds arise from Lewis acid–base interactions between an electron-donating N-ligand and an electron-deficient boron atom (empty 2p orbital) (23, 24). They typically induce structural changes. For example, the boron atom of an aromatic boronic ester provides a trigonal planar coordination geometry. Upon binding to a pyridyl moiety, the geometry about the boron atom becomes approximately tetrahedral, and the pyridyl group adopts an orthogonal orientation relative to the ester (25). In addition, dative B─N bonds often undergo fast dynamic exchange in solution while stabilizing relatively strong bonds in solid materials (26–28). In the context of molecular engineering, this unique combination allows so-called kinetic traps to be avoided en route to the thermodynamically most stable state and hence the isolation of relatively large-sized single crystals (29, 30). We thus considered that dative B─N bonds would permit the integration of MIMs into purely organic polymeric crystals. As detailed below, these design expectations were met.

To create a crystalline ordered polyrotaxane material, a permanently interlocked pyridine end-modified [2]rotaxane building block (TRpy) was used to ensure retention of the mechanical link during self-assembly (Fig. 1A). An air and moisture stable bis(dioxaborole) (BE) was selected as the linker (Fig. 1A). The dative B─N bonds arising from the interaction of these two monomers was expected to permit the efficient synthesis of a one-dimensional (1D) polyrotaxane (Fig. 1B). The resulting structure was found to benefit from the dynamic nature of the TRpy-BE B─N bond with limiting zigzag versus helical structures being obtained depending on the choice of crystallization solvent (Fig. 1C). As detailed below, differences in mechanical features, including stiffness, elasticity, and reversible switching, were found to accompany the underlying conformation changes.

RESULTS

Monomers TRpy and BE were chosen as key building blocks to support the formation of a polyrotaxane structure through dative B─N bonds. Both are ditopic systems with the first (TRpy) containing two pyridine moieties, while the second (BE) encompasses two borate esters as the proposed respective points of attachment. The TRpy subunit also contains a permanent rotaxane motif provided by a rigid aniline axle with hindered xylene stoppers surrounded by a [24]crown ether-like wheel. Detailed synthetic procedures for TRpy and BE are provided in the Supplementary Materials along with associated characterization data (cf. section S1). Briefly, reductive amination followed by Grubbs catalyst–based clipping was used to create the [2]rotaxane core, which was then subject to Suzuki coupling to install the 4-pyridyl units. Separately, the planar diboronate ester monomer BE was prepared through the condensation of diboronic acid with catechol.

When a mixture of TRpy and BE (n/n, 1/1) in benzene was held at 25°C for 36 hours, micron-sized yellow transparent crystals were formed (Fig. 2A). Single-crystal x-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis revealed a paired zigzag polyrotaxane structure, PR-1, in an infinite stacked layer arrangement. The discrepancy factor R for the structure was 13.2%, which allowed key structural information, such as atomic positions, geometric parameters, chain conformation, and packing, to be obtained. It was found that one chain within the zigzag pair that makes up the smallest readily defined polymeric unit in PR-1 contains TRpy subunits in two different conformations (denoted in purple rings on the cyan chain in Fig. 2B). Two different TRpy conformations are seen in the adjacent chain (shown as purple rings on the brown chain in Fig. 2B). As a result, the four most closely aligned TRpy monomers all exhibit different conformations. Presumably, this finding reflects the fact that the rotational dynamics within the individual TRpy rotaxane subunits are relatively unrestricted.

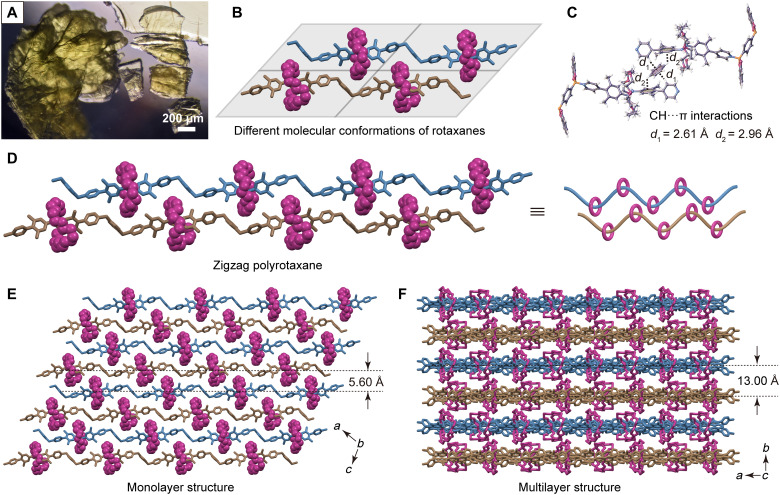

Fig. 2. Optical image and single crystal structure of PR-1.

(A) Photograph showing single crystals of PR-1 under an optical microscope with ×40 magnification. (B) Schematic showing the four different molecular conformations of TRpy unit seen in the single-crystal x-ray diffraction (SCXRD) structure of PR-1. (C) Illustration of the various CH⋯π interactions between the benzene solvent molecules and the adjacent polymer chains within PR-1 as inferred from the metric parameters. (D) Parallel zigzag arrangement of the two polyrotaxane chains that make up the smallest readily identifiable polymeric unit in PR-1. (E) Top view of the parallel arrangement of polyrotaxane chains within a given monolayer. (F) Lateral view of the overall stacked multilayered structure of PR-1. The H atoms and catechol groups in (B), (D), (E), and (F) have been omitted for clarity.

An analysis of the overall structure revealed that in PR-1 the neighboring chains are bridged by benzene solvent molecules and stabilized by two sets of symmetric CH⋯π interactions characterized by distances of 2.61 and 2.96 Å, respectively (Fig. 2C) (31). As a presumed consequence, a parallel zigzag conformation is stabilized (Fig. 2D) wherein one TRpy unit and one BE moiety make up the repeat unit of each polymer chain. A top view (ac planes) of the crystal structure reveals that the parallel polyrotaxane chains adopt an AB arrangement with an interchain distance of 5.60 Å (Fig. 2E). This ordering produces a 2D monolayer that stacks to form a 3D multilayer structure. As shown in the lateral view (ab planes; Fig. 2F), the adjacent 2D layers stack in an antiparallel fashion. Nevertheless, the distance between the layers is 13.00 Å, which allows enough space for the individual rotaxane subunits to sample different conformations without affecting adversely the crystallinity of the overall polymeric structure.

In accord with our design expectations, the formation of PR-1 appears driven by the formation of dative B─N bonds. To this end, the kinetics and thermodynamics underlying these interactions in the solution and solid state were probed. Accordingly, the association constant Ka of the B─N bond was calculated to be 22 ± 3 M−1, whereas the exchange equilibrium kdiss value was calculated to be 5.9 × 105 s−1 at 298.2 K (sections S3 and S4), which indicates a weak (but favorable) binding between the monomers with a correspondingly low degree of polymerization and relatively facile exchange between the monomers and the polyrotaxanes in solution (28). For the B─N bond interactions in the solid state, clear electron density changes before and after formation of B─N bond were seen by color-filled mapping of the electron localization function (figs. S5 to S7). At the same time, the B─N bond lengths, 1.645 to 1.679 Å for PR-1, are close to those seen in typical covalent bonds (32). The B─N bond energy was calculated to be 172.1(1) kJ mol−1 (table S3). The bond energy in the solid state exceeds those for most noncovalent interactions (fig. S8). Overall, the proposed dative B─N bonds appear sufficient to promote the formation of PR-1.

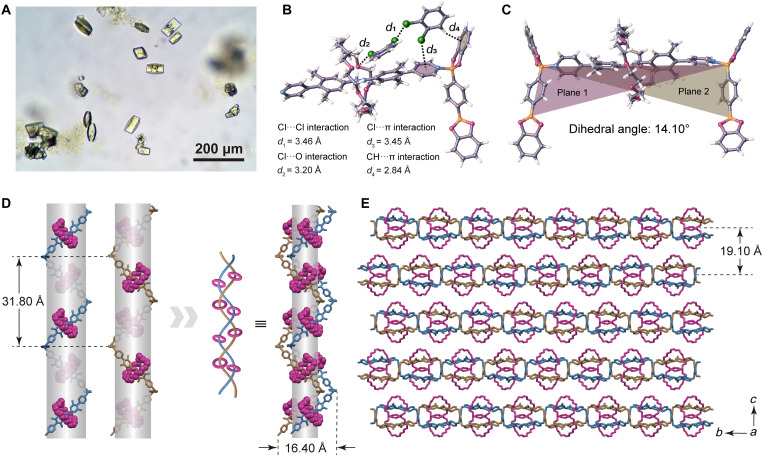

The CH⋯π interactions seen in PR-1 led us to consider that the aggregated forms of the polyrotaxane crystals produced from TRpy and BE might prove sensitive to the choice of solvent. As a test of this proposition, crystals of PR-1 were separated from the mother liquor by filtration and then soaked in o-dichlorobenzene. Letting stand at room temperature for a week led to a change in the color of the mixture from light yellow to orange. Many spindle-shaped yellow crystals were produced with an average size of 40 to 80 μm (the distance between two vertices), as shown by optical microscopy (Fig. 3A). An SCXRD analysis revealed that these crystals exhibited a double-stranded helical arrangement for the polyrotaxane chains; this crystalline form is referred to as PR-2. The discrepancy factor R of PR-2 is 11.2%, which also enabled key structural parameters to be determined. Analysis of the microstructure (Fig. 3B) revealed two o-dichlorobenzene molecules in close proximity, stabilized by a presumed Cl⋯Cl bond at a distance of 3.46 Å (33). This dimer is slotted between, and is in apparent contact with, the macrocycle of a TRpy subunit and with the benzene ring of an adjacent BE. The Cl⋯O distance is 3.20 Å (34), whereas the CH⋯π separation is a 2.84 Å (31). Moreover, a presumed halogen-π interaction characterized by a 3.45-Å separation was observed between an o-dichlorobenzene Cl atom and the TRpy pyridine ring (35). We suggest that these four sets of noncovalent interactions act in synergistic fashion to enforce a dihedral angle of 14.10° (Fig. 3C) between the benzene rings of two adjacent BE monomers. A gradual extension of the slight twist seen in the resulting individual twisted fragments gradually accumulates to yield a helical conformation. An intertwining between neighboring helical chains gives rise to an unusual double-helical structure in which right-handed and left-handed polyrotaxanes are braided together to give a double helix with a diameter of 16.40 Å and a helical pitch of 31.80 Å (Fig. 3D). Two TRpy and two BE monomers are required to form a complete turn. In the solid state, adjacent layers of the double-helical polyrotaxane are stacked in an antiparallel fashion along the a axis with an interlayer distance of 19.10 Å (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3. Optical image of single crystals of PR-2 and various views of the resulting x-ray diffraction structure.

(A) Photograph of single crystals of PR-2 as viewed under an optical microscope at ×100 magnification. (B) Illustration of the various noncovalent interactions between o-dichlorobenzene solvent molecules and the polymer chains of PR-2. (C) Twist seen in a BE-TRpy-BE subunit within the overall polyrotaxane chain. The dihedral angle between the two adjacent BE monomers is 14.10°. (D) Views of two complementary single strands with opposite conformations and the double helix formed by dislocated parallel stacking of two single helices. (E) Lateral view of the stacked multilayered structure present in the single-crystal structure of PR-2. The H atoms and catechol groups in (D) and (E) have been omitted for clarity.

The solvent-induced change in form proved reversible. Specifically, when solid PR-2, formed by immersing crystals of polyrotaxane PR-1 in o-dichlorobenzene, was isolated and immersed in benzene at room temperature for 4 days, the original zigzag form, PR-1, was regenerated. Soaking in o-dichlorobenzene then gave PR-2 once again. This process was repeated five times with no apparent loss of topological integrity. Optical microscopic analyses and the cell parameters of crystalline samples were used to confirm the stepwise conversion between the zigzag and helical topologies (cf. fig. S9).

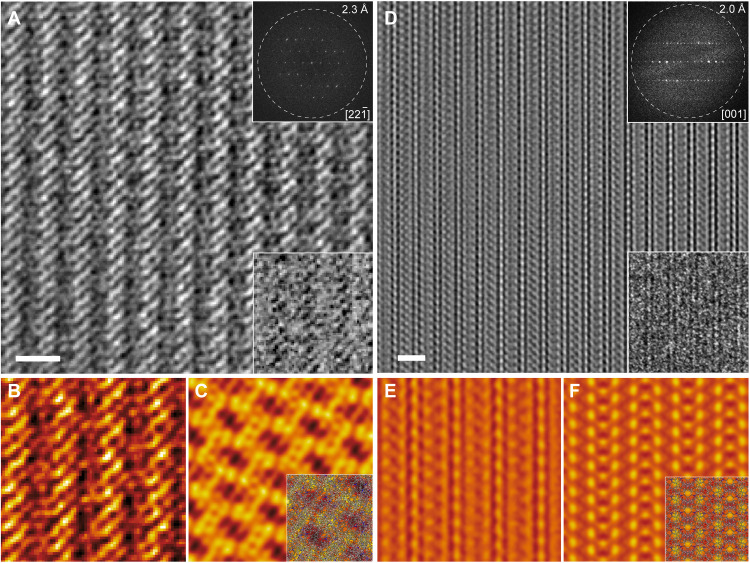

Electron microscopy (EM) constitutes a powerful tool that permits the visualization of molecular structures and associated packing modes at a high spatial resolution. It is thus an important complement to x-ray crystallography (i.e., SCXRD), which provides spatially averaged structural information from Bragg scattering in the reciprocal space. Unfortunately, organic crystals are prone to structural disintegration during the conventional high-resolution transmission EM (HRTEM) imaging, primarily reflecting the effects of radiolysis (36). In the present instance, these latter limitations were overcome by integrating cryo-EM, a state-of-the-art low-dose HRTEM imaging technique developed recently (37–39), with a custom-designed ultrastable cryo-transfer holder, and we were able to minimize radiolytic beam damage. Specifically, the critical dose could be increased from 5.9 to 11.6 e Å−2 (see fig. S17) to visualize the molecular structures of PR-1 and PR-2 with high spatial resolution and structural integrity. After denoising and correcting the contrast inversion effects arising from the contrast transfer function (CTF) of the objective lens, low-dose cryo-EM images of PR-1 and PR-2 acquired in this way revealed highly ordered parallel arrays of superimposed polyrotaxane chains throughout the entire imaged area (Fig. 4, A and D). Fast Fourier transforms (FFTs) of these images show that the structural information transfer is as high as ca. 2.3 and 2.0 Å, respectively (top right insets Fig. 4, A and D). This was taken as evidence for the preservation of the crystallinity in these polyrotaxane structures. A false-colored enlarged view of the image for PR-1 shows periodically parallel zigzag arranged bright strips (Fig. 4B). These features match well the simulated projected electrostatic potential map (Fig. 4C) and the structural projection of PR-1 along the [22] direction (inset in Fig. 4C). The double-stranded helical polymeric chains of PR-2 also show readily recognizable features. A top view (i.e., along the [001] direction) of the multilayer structure composed of double-stranded polyrotaxane chains can be clearly identified from the false-colored enlarged view of the low-dose cryo-EM image (Fig. 4E), which match well with the simulated electrostatic potential and structural projection of PR-2 along the [001] direction (Fig. 4F and inset). Together, these observations confirm the perfectly ordered polyrotaxane arrays and the absence of readily discernible defects for PR-1 and PR-2 inferred on the basis of the corresponding SCXRD analyses.

Fig. 4. Real-space high-resolution structural visualization of PR-1 and PR-2 by cryogenic low-dose HRTEM imaging.

(A and D) Cryogenic low-dose denoised high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images of PR-1 and PR-2 taken along the [22] and [001] directions, respectively. Insets show raw images (bottom right) and the fast Fourier transform (FFT) patterns (top right). (B and E) The enlarged images after correcting for contrast inversion effects due to the objective lens contrast transfer function (CTF) for PR-1 and PR-2. (C and F) Simulated projected electrostatic potential maps with point spread function widths of 2.3 and 2.0 Å for PR-1 and PR-2, respectively. Insets contain embedded the corresponding projected crystal structural models. Scale bars, 2 nm in (A) and (D).

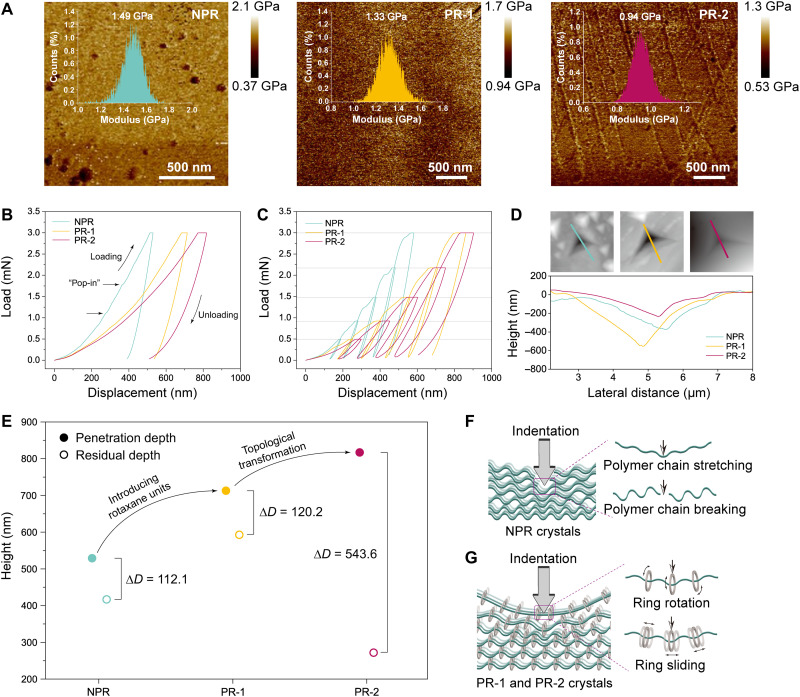

Next, we sought to explore whether the permanent and regiochemically defined rotaxane subunits present in PR-1 and PR-2 would be reflected in their macroscopic properties. With this goal in mind, diffraction-grade crystals of a control polymer (NPR) lacking the rotaxane wheel were also prepared (section S8). PeakForce quantitative nanomechanical mapping (QNM) was used to explore the difference among NPR, PR-1, and PR-2. The Derjaguin-Muller-Toporov (DMT) moduli of PR-1 and PR-2 were found to be ~1.33 and ~0.94 GPa, respectively. While both values are smaller than the ~1.49 GPa recorded for the nonrotaxane polymer NPR (Fig. 5A), a particularly noteworthy reduction is seen in the case of PR-2, a result that we interpret in terms of the constituent rotaxanes providing softness to the macroscopic crystals (40). Next, we scrutinized the deformation properties of these three crystalline materials under conditions of nanoindentation. Load-displacement (P-h) curves were obtained by indenting each crystal with a Berkovich tip under a fixed load of 3 mN. Under the same load, PR-1 and PR-2 exhibit greater displacement depths than NPR along an axis perpendicular to the multilayer stacking plane (along the b axis for PR-1 and NRP and the c axis for PR-2; Fig. 5B). From fittings of the unloading curves, the average values of the Young’s modulus E and hardness H of PR-1 and PR-2 (EPR-1 = 6.11 GPa, EPR-2 = 3.72 GPa, HPR-1 = 0.25 GPa, and HPR-2 = 0.15 GPa; tables S8 and S9) were found to be much smaller than those of NPR (ENPR = 9.01 GPa and HNPR = 0.35 GPa; table S7). These low E and H values provide further support for the conclusion that PR-1 and PR-2 are softer than NPR. Moreover, displacement bursts (pop-ins) are observed in the P-h curves, suggesting the sudden penetration of the indenter tip under a fixed load (41). The “pop-in” behavior in the P-h curve of NPR is attributed to a fracturing of the local crystalline structure under the force of the indenter tip (Fig. 5B) (41–44). This is not observed in the case of PR-1 and PR-2, further supporting the conclusion that these two polyrotaxane crystals display homogeneous elasticity behavior when subject to external mechanical stress by the Berkovich tip (45). This elasticity is ascribed to the dynamic response provided by the mobile rotaxanes within the crystalline polymers that act in concert to dissipate mechanical stress.

Fig. 5. Mechanical properties of NPR, PR-1, and PR-2.

(A) Mapping of the Derjaguin-Muller-Toporov (DMT) moduli of NPR, PR-1, and PR-2. Insets, the corresponding DMT modulus distribution. (B) Load-displacement (P-h) curves for NPR (along the b axis), PR-1 (along the b axis), and PR-2 (along the c axis) at a fixed load (3 mN). (C) Representative P-h curves of multiload nanoindentation for NPR, PR-1, and PR-2. (D) 2D representation of the scanning probe microscopic (SPM) images of the residual indent impressions for NPR, PR-1, and PR-2 and the corresponding height profiles along the line shown in the SPM images. (E) Plots of penetration depth (solid points), residual depth (hollow points), and rebound depth (ΔD) for NPR, PR-1, and PR-2. (F) Schematic illustration of the stress dissipation of NPR when subject to external pressure. (G) Schematic illustration of the stress dissipation of PR-1 or PR-2 when subject to external pressure.

Multiple load cycles with an increasing load were then performed to check the mechanical stability of NPR, PR-1, and PR-2. Compared with those for NPR, the multiple loading curves of PR-1 and PR-2 are relatively smooth and devoid of obvious pop-in effects (Fig. 5C). Moreover, the multiple loading parts of PR-1 (or PR-2) form a smooth continuously increasing trend (cf. black dashed line in fig. S24). These smooth trends reflect that the PR-1 and PR-2 crystals have no obvious structural damage during multiple load cycles, which further indicates their excellent stability (46). A particularly slight residual indentation impression and small residual depth were seen after pressing the surface of PR-2 (Fig. 5D). We also plotted the respective rebound depth (ΔD) for NPR, PR-1, and PR-2 and found that PR-2 is characterized by a ΔD value (543.6 nm) that is almost five times that of NPR or PR-1 (Fig. 5E).

On the basis of the above findings, we suggest that the nonrotaxane crystalline polymer, NPR, can dissipate stress only by stretching or even breaking the constituent polymer chains during external compression (Fig. 5F). In the case of PR-1, the polyrotaxane rings, although arranged regularly within the crystal lattice, can rotate and slide along the individual TRpy axle components. This motion provides for effective stress dissipation (Fig. 5G) (47–49) and endows the crystalline materials with excellent softness. In the case of PR-2, the intricate and synergetic rotaxane subunits endow the crystals with enhanced dynamic properties and an ability to disperse stress and dissipate energy under external stimuli. On the other hand, the relatively rigid double-helical backbone serves to maintain the integrity of the overall crystal arrangement. PR-2 thus displays enhanced softness and greater elasticity than PR-1. Overall, these findings serve to underscore the conclusion that the mechanical properties of polyrotaxane crystals are affected not only by the constituent repeating units but also by their overall topologies. In favorable cases, these effects can act in concert to provide for improvements in key macroscopic properties, such as softness and elasticity, which are not generally associated with crystalline materials.

DISCUSSION

In summary, we have successfully prepared a set of purely organic polyrotaxane crystals as confirmed by SCXRD and a novel cryogenic low-dose HRTEM technique. To meet this challenge, we exploited the fast exchange dynamics of dative B─N bonds to drive self-assembly. The resulting polyrotaxane strands aggregate to give a pair of zigzag chains, which constitute the key repeat unit within the overall 3D lattice. Reversible solvent-induced transformations from the zigzag form to a double-helix–containing structure are seen upon exposure to o-dichlorobenzene and retreatment with benzene. The process could be repeated multiple times. The polyrotaxane crystals of the present study display unique bulk properties, such as softness and elasticity, which are not recapitulated in a non-MIM polymeric control system. These mechanical features are ascribed to energy-dissipating microscopic motions of the constituent high-density rotaxane units. Of particular note is that the two limiting structural forms of the polyrotaxane aggregates are characterized by different bulk mechanical properties. This work not only provides a new strategy to integrate MIMs into purely organic crystalline materials but also opens up the possibility of tailoring organic 2D/3D mechanically interlocked frameworks to generate crystalline polymers with features that are beyond the reach of conventional mechanically interlocked materials, such as MORFs. Moreover, the motions of the rings on the rotaxane units are probably a unique factor to improve the elasticity of these organic polyrotaxane crystalline materials. It is expected that the mechanical properties of these organic crystalline materials can be further improved by including flexible spacers in the monomer or replacing the [2]rotaxane structure with a more flexible [3]rotaxane structure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All reagents were purchased from Shanghai Haohong Scientific Co. Ltd. and used without further purification. Compounds 1 to 7, TRpy, and BE were prepared according to literature procedures (50–55). 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE NEO 600-MHz instrument. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million and are referenced to the solvent residual peaks or TMS as the internal reference. Coupling constants (J) are reported in hertz. HR mass spectrometry measurements were performed on an Agilent G6545 instrument equipped with an electrospray ionization source and a quadrupole orthogonal acceleration–time-of-flight ion analyzer. SCXRD data were collected on a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer with a PHOTON III detector in shutterless mode with an Incoatec Microfocus source (Mo-diamond Kα radiation, λ = 0.71073 Å) equipped with an Oxford 800 Plus liquid nitrogen vapor cooling device. Thermogravimetric analyses were performed using a TA Instruments SDT Q600 instrument over the 25° to 800°C temperature range at a heating rate of 10°C min−1 under air. Low-dose HRTEM images were acquired on a Thermo Fisher Scientific Themis transmission electron microscope equipped with a Cs corrector on the objective lens and a Gatan K3 electron direct detection camera. The beam-sensitive specimens were loaded on a Gatan custom-made ultrastable double tilt Elsa 698 Cryo-Transfer holder, which was kept at −170°C during the experiment to enhance the durability of the specimen under conditions of electron beam irradiation. The microscope was operated at an acceleration voltage of 300 kV under a very low electron dose rate (1 e Å−2 s−1). Series of images were acquired by dose fractionation with a frame rate of 10 frame s−1 for 10 s. The image stack was then subjected to post-acquisition drift and contrast correction before comparing with the simulated projected electrostatic potentials. PeakForce QNM was carried out with a Bruker Atomic Force Microscopy Dimension Icon instrument using an Au-coated cantilever presenting a tip with a radius of 10 nm. Nanoindentation measurements were performed with a Bruker Hysitron TI980 nanoindenter equipped with a Berkovich diamond indenter. A maximum load value of 3 mN was applied, and a loading/unloading rate of 0.6 mN s−1 was used for all of the experiments. The holding time at the maximum load was set to be 2 s. After unloading, the residual indent impressions and corresponding height profiles were scanned immediately by scanning probe microscopy (SPM). In the multiple loading mode, each indentation was performed with five loading/unloading cycles until a peak load of 3 mN was reached. Scanning EM analyses were carried out with a Verios G4 field-emission scanning electron microscope combined with energy-dispersive x-ray analysis.

Preparation of PR-1

TRpy (22.2 mg, 0.0300 mmol) and BE (9.41 mg, 0.0300 mmol) were dissolved in benzene (15 ml) and placed in an ultrasonic bath for 15 min. The solution was then held at 25°C for 120 hours protected from light and vibration. Yellow transparent crystals of PR-1 were obtained that were clearly visible to the naked eye. Melting point: >260°C (decomp).

Preparation of PR-2

Crystals of PR-1 (5.00 mg) were added to o-dichlorobenzene (5 ml). The mixture was then held at 25°C for 160 hours protected from light and vibration. The color of the solution gradually changes from light yellow to orange. Yellow spindle-shaped crystals of PR-2 were obtained that were clearly visible to the unaided eye. Melting point: >250°C (decomp).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Q. He from the Chemistry Instrumentation Center, Zhejiang University for the technical support.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA0910100 and 2022YFE0113800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22035006, 22122505, 22075250, 22205200, and 21771161), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LD21B020001), the Starry Night Science Fund of Zhejiang University Shanghai Institute for Advanced Study (SN-ZJU-SIAS-006), and the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology Office of Sponsored Research (OSR-2019-CRG8-4032). The work in Austin was supported by the Robert A. Welch Foundation (F-0018).

Author contributions: X.X., D.X., T.S., and J.W. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. G.S., Y.L., and Y.Z. performed the HRTEM imaging and analyses. X.M. tested and analyzed the SCXRD data. X.X., G.L., J.L.S., and F.H. cowrote the paper.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. CCDC 2236355, 2236356, and 2236357 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Supplementary discussions

Figs. S1 to S40

Tables S1 to S9

References

Correction (15 November 2023):

Due to a production error, the reference list that appeared in the original Supplementary Materials did not match the reference list in the main text. The SM file has been corrected. The PDF and HTML have been updated. The original version is available here:

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.J. F. Stoddart, Mechanically interlocked molecules (MIMs)—Molecular shuttles, switches, and machines (Nobel Lecture). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 11094–11125 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.C. J. Bruns, J. F. Stoddart, in The Nature of the Mechanical Bond: From Molecules to Machines (John Wiley & Sons, 2016), pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- 3.B. Lewandowski, G. De Bo, J. W. Ward, M. Papmeyer, S. Kuschel, M. J. Aldegunde, P. M. E. Gramlich, D. Heckmann, S. M. Goldup, D. M. D’Souza, A. E. Fernandes, D. A. Leigh, Sequence-specific peptide synthesis by an artificial small-molecule machine. Science 339, 189–193 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.S. Choi, T.-W. Kwon, A. Coskun, J. W. Choi, Highly elastic binders integrating polyrotaxanes for silicon microparticle anodes in lithium ion batteries. Science 357, 279–283 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.H. Chen, J. F. Stoddart, From molecular to supramolecular electronics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 804–828 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 6.H. Xing, Z. Li, W. Wang, P. Liu, J. Liu, Y. Song, L. W. Zi, W. Zhang, F. Huang, Mechanochemistry of an interlocked poly[2]catenane: From single molecule to bulk gel. CCS Chem. 2, 513–523 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7.L. Zhang, Y. Qiu, W.-G. Liu, H. Chen, D. Shen, B. Song, K. Cai, H. Wu, Y. Jiao, Y. Feng, J. S. W. Seale, C. Pezzato, J. Tian, Y. Tan, X.-Y. Chen, Q.-H. Guo, C. L. Stern, D. Philp, R. D. Astumian, W. A. Goddard, J. F. Stoddart, An electric molecular motor. Nature 613, 280–286 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Y. Ren, R. Jamagne, D. J. Tetlow, D. A. Leigh, A tape-reading molecular ratchet. Nature 612, 78–82 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Y. Qiu, B. Song, C. Pezzato, D. Shen, W. Liu, L. Zhang, Y. Feng, Q.-H. Guo, K. Cai, W. Li, H. Chen, M. T. Nguyen, Y. Shi, C. Cheng, R. D. Astumian, X. Li, J. F. Stoddart, A precise polyrotaxane synthesizer. Science 368, 1247–1253 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Q. Wu, P. M. Rauscher, X. Lang, R. J. Wojtecki, J. J. de Pablo, M. J. A. Hore, S. J. Rowan, Poly[n]catenanes: Synthesis of molecular interlocked chains. Science 358, 1434–1439 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.J. W. Choi, A. H. Flood, D. W. Steuerman, S. Nygaard, A. B. Braunschweig, N. N. P. Moonen, B. W. Laursen, Y. Luo, E. DeIonno, A. J. Peters, J. O. Jeppesen, K. Xu, J. F. Stoddart, J. R. Heath, Ground-state equilibrium thermodynamics and switching kinetics of bistable [2]rotaxanes switched in solution, polymer gels, and molecular electronic devices. Chem. A Eur. J. 12, 261–279 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.H. Deng, M. A. Olson, J. F. Stoddart, O. M. Yaghi, Robust dynamics. Nat. Chem. 2, 439–443 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.E. R. Kay, D. A. Leigh, F. Zerbetto, Synthetic molecular motors and mechanical machines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 72–191 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.V. N. Vukotic, S. J. Loeb, Coordination polymers containing rotaxane linkers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 5896–5906 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.B. H. Wilson, S. J. Loeb, Integrating the mechanical bond into metal-organic frameworks. Chem 6, 1604–1612 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 16.J. Li, X. Wang, G. Zhao, C. Chen, Z. Chai, A. Alsaedi, T. Hayat, X. Wang, Metal–organic framework-based materials: Superior adsorbents for the capture of toxic and radioactive metal ions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 2322–2356 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.A. J. Stephens, R. Scopelliti, F. F. Tirani, E. Solari, K. Severin, Crystalline polymers based on dative boron–nitrogen bonds and the quest for porosity. ACS Materials Lett. 1, 3–7 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 18.J. G. Paithankar, S. Saini, S. Dwivedi, A. Sharma, D. K. Chowdhuri, Heavy metal associated health hazards: An interplay of oxidative stress and signal transduction. Chemosphere 262, 128350 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.M. Jaishankar, T. Tseten, N. Anbalagan, B. B. Mathew, K. N. Beeregowda, Toxicity, mechanism and health effects of some heavy metals. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 7, 60–72 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.L. Feng, R. D. Astumian, J. F. Stoddart, Controlling dynamics in extended molecular frameworks. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 705–725 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.G. Das, S. K. Sharma, T. Prakasam, F. Gándara, R. Mathew, N. Alkhatib, N. Saleh, R. Pasricha, J.-C. Olsen, M. Baias, S. Kirmizialtin, R. Jagannathan, A. Trabolsi, A polyrotaxanated covalent organic network based on viologen and cucurbit[7]uril. Commun. Chem. 2, 106 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 22.B. Colasson, T. Devic, J. Gaubicher, C. Martineau-Corcos, P. Poizot, V. Sarou-Kanian, Dual electroactivity in a covalent organic network with mechanically interlocked pillar[5]arenes. Chem. A Eur. J. 27, 9589–9596 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.J. P. M. Antonio, G. D. V. Farias, F. M. F. Santos, R. Oliveira, P. M. S. D. Cal, P. M. P. Gois, in Non-covalent Interactions in the Synthesis and Design of New Compounds, Abel M. Maharramov, Kamran T. Mahmudov, Maximilian N. Kopylovich, Armando J. L. Pombeiro, Eds. (John Wiley & Sons, 2016), pp. 23–48. [Google Scholar]

- 24.E. Sheepwash, V. Krampl, R. Scopelliti, O. Sereda, A. Neels, K. Severin, Molecular networks based on dative boron–nitrogen bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 3034–3037 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.G. Campillo-Alvarado, K. P. D'Mello, D. C. Swenson, S. V. Santhana Mariappan, H. Höpfl, H. Morales-Rojas, L. R. MacGillivray, Exploiting boron coordination: B←N bond supports a [2+2] photodimerization in the solid state and generation of a diboron bis-tweezer for benzene/thiophene separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 5413–5416 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.E. Sheepwash, N. Luisier, M. R. Krause, S. Noé, S. Kubik, K. Severin, Supramolecular polymers based on dative boron–nitrogen bonds. Chem. Commun. 48, 7808–7810 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.N. Christinat, R. Scopelliti, K. Severin, Multicomponent assembly of boron-based dendritic nanostructures. J. Org. Chem. 72, 2192–2200 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.F. Vidal, J. Gomezcoello, R. A. Lalancette, F. Jäkle, Lewis pairs as highly tunable dynamic cross-links in transient polymer networks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 15963–15971 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D. Beaudoin, T. Maris, J. D. Wuest, Constructing monocrystalline covalent organic networks by polymerization. Nat. Chem. 5, 830–834 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.S. Wang, Z. Zhang, H. Zhang, A. G. Rajan, N. Xu, Y. Yang, Y. Zeng, P. Liu, X. Zhang, Q. Mao, Y. He, J. Zhao, B.-G. Li, M. S. Strano, W.-J. Wang, Reversible polycondensation-termination growth of covalent-organic-framework spheres, fibers, and films. Matter 1, 1592–1605 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 31.M. Brandl, M. S. Weiss, A. Jabs, J. Sühnel, R. Hilgenfeld, C-H⋯π-interactions in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 307, 357–377 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.H. Höpfl, The tetrahedral character of the boron atom newly defined—A useful tool to evaluate the N→B bond. J. Organomet. Chem. 581, 129–149 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 33.D. Sutradhar, A. K. Chandra, Cl⋯Cl halogen bonding: Nature and effect of substituent at electron donor Cl atom. ChemistrySelect 5, 554–563 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 34.P. Auffinger, F. A. Hays, E. Westhof, P. S. Ho, Halogen bonds in biological molecules. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101, 16789–16794 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.H. T. Chifotides, K. R. Dunbar, Anion-π interactions in supramolecular architectures. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 894–906 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Z. Cai, S. Chen, L.-W. Wang, Dissociation path competition of radiolysis ionization-induced molecule damage under electron beam illumination. Chem. Sci. 10, 10706–10715 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Y. Zhu, J. Ciston, B. Zheng, X. Miao, C. Czarnik, Y. Pan, R. Sougrat, Z. Lai, C.-E. Hsiung, K. Yao, I. Pinnau, M. Pan, Y. Han, Unravelling surface and interfacial structures of a metal–organic framework by transmission electron microscopy. Nat. Mater. 16, 532–536 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D. Zhang, Y. Zhu, L. Liu, X. Ying, C.-E. Hsiung, R. Sougrat, K. Li, Y. Han, Atomic-resolution transmission electron microscopy of electron beam–sensitive crystalline materials. Science 359, 675–679 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.L. Liu, Z. Chen, J. Wang, D. Zhang, Y. Zhu, S. Ling, K.-W. Huang, Y. Belmabkhout, K. Adil, Y. Zhang, B. Slater, M. Eddaoudi, Y. Han, Imaging defects and their evolution in a metal–organic framework at sub-unit-cell resolution. Nat. Chem. 11, 622–628 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.U. Lewandowska, W. Zajaczkowski, S. Corra, J. Tanabe, R. Borrmann, E. M. Benetti, S. Stappert, K. Watanabe, N. A. K. Ochs, R. Schaeublin, C. Li, E. Yashima, W. Pisula, K. Müllen, H. Wennemers, A triaxial supramolecular weave. Nat. Chem. 9, 1068–1072 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.S. Varughese, M. S. R. N. Kiran, U. Ramamurty, G. R. Desiraju, Nanoindentation in crystal engineering: Quantifying mechanical properties of molecular crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 2701–2712 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.S. Mannepalli, K. S. R. N. Mangalampalli, Indentation plasticity and fracture studies of organic crystals. Crystals 7, 324 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 43.B. P. A. Gabriele, C. J. Williams, M. E. Lauer, B. Derby, A. J. Cruz-Cabeza, Nanoindentation of molecular crystals: Lessons learned from aspirin. Cryst. Growth Des. 20, 5956–5966 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.S. SeethaLekshmi, M. S. R. N. Kiran, U. Ramamurty, S. Varughese, Phase transitions and anisotropic mechanical response in a water-rich trisaccharide crystal. Cryst. Growth Des. 20, 442–448 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 45.S. Das, S. Saha, M. Sahu, A. Mondal, C. M. Reddy, Temperature-reliant dynamic properties and elasto-plastic to plastic crystal (rotator) phase transition in a metal oxyacid salt. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202115359 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.J. E. Jakes, D. S. Stone, Best practices for quasistatic Berkovich nanoindentation of wood cell walls. Forests 12, 1696 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 47.A. J. Thompson, A. I. Chamorro Orué, A. J. Nair, J. R. Price, J. McMurtrie, J. K. Clegg, Elastically flexible molecular crystals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 11725–11740 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.V. N. Vukotic, K. J. Harris, K. Zhu, R. W. Schurko, S. J. Loeb, Metal–organic frameworks with dynamic interlocked components. Nat. Chem. 4, 456–460 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.K. Zhu, C. A. O'Keefe, V. N. Vukotic, R. W. Schurko, S. J. Loeb, A molecular shuttle that operates inside a metal–organic framework. Nat. Chem. 7, 514–519 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.B. Kang, J. W. Kurutz, K.-T. Youm, R. K. Totten, J. T. Hupp, S. T. Nguyen, Catalytically active supramolecular porphyrin boxes: Acceleration of the methanolysis of phosphate triesters via a combination of increased local nucleophilicity and reactant encapsulation. Chem. Sci. 3, 1938–1944 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 51.P. Martinez-Bulit, C. A. O’Keefe, K. Zhu, R. W. Schurko, S. J. Loeb, Solvent and steric influences on rotational dynamics in porphyrinic metal–organic frameworks with mechanically interlocked pillars. Cryst. Growth Des. 19, 5679–5685 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 52.N.-K. Kim, H. Sogawa, T. Takata, Cu-tethered macrocycle catalysts: Synthesis and size-selective CO2-fixation to propargylamines under ambient conditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 61, 151966 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 53.P. G. Clark, E. N. Guidry, W. Y. Chan, W. E. Steinmetz, R. H. Grubbs, Synthesis of a molecular charm bracelet via click cyclization and olefin metathesis clipping. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 3405–3412 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.K. Zhu, V. N. Vukotic, C. A. O’Keefe, R. W. Schurko, S. J. Loeb, Metal–organic frameworks with mechanically interlocked pillars: Controlling ring dynamics in the solid-state via a reversible phase change. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 7403–7409 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.W. Niu, B. Rambo, M. D. Smith, J. J. Lavigne, Substituent effects on the structure and supramolecular assembly of bis(dioxaborole)s. Chem. Commun. 41, 5166–5168 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.A. D. Herrera-España, H. Höpfl, H. Morales-Rojas, Boron–nitrogen double tweezers comprising arylboronic esters and diamines: Self-assembly in solution and adaptability as hosts for aromatic guests in the solid state. ChemPlusChem 85, 548–560 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.F. Neese, Software update: The ORCA program system, version 4.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 8, e1327 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 58.A. D. Becke, Density‐functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 59.F. Weigend, R. Ahlrichs, Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 7, 3297–3305 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.S. Grimme, S. Ehrlich, L. Goerigk, Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.T. Lu, F. Chen, Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary discussions

Figs. S1 to S40

Tables S1 to S9

References

Correction (15 November 2023):

Due to a production error, the reference list that appeared in the original Supplementary Materials did not match the reference list in the main text. The SM file has been corrected. The PDF and HTML have been updated. The original version is available here: