Abstract

D‐1553 is a small molecule inhibitor selectively targeting KRASG12C and currently in phase II clinical trials. Here, we report the preclinical data demonstrating antitumor activity of D‐1553. Potency and specificity of D‐1553 in inhibiting GDP‐bound KRASG12C mutation were determined by thermal shift assay and KRASG12C‐coupled nucleotide exchange assay. In vitro and in vivo antitumor activity of D‐1553 alone or in combination with other therapies were evaluated in KRASG12C mutated cancer cells and xenograft models. D‐1553 showed selective and potent activity against mutated GDP‐bound KRASG12C protein. D‐1553 selectively inhibited ERK phosphorylation in NCI‐H358 cells harboring KRASG12C mutation. Compared to the KRAS WT and KRASG12D cell lines, D‐1553 selectively inhibited cell viability in multiple KRASG12C cell lines, and the potency was slightly superior to sotorasib and adagrasib. In a panel of xenograft tumor models, D‐1553, given orally, showed partial or complete tumor regression. The combination of D‐1553 with chemotherapy, MEK inhibitor, or SHP2 inhibitor showed stronger potency on tumor growth inhibition or regression compared to D‐1553 alone. These findings support the clinical evaluation of D‐1553 as an efficacious drug candidate, both as a single agent or in combination, for patients with solid tumors harboring KRASG12C mutation.

Keywords: inhibitor, KRASG12C , mutation, solid tumor, targeted therapy

D‐1553 is a novel and potent inhibitor of KRASG12C. D‐1553 shows an inhibitory effect on the RAS–MEK signaling pathway. D‐1553 has antitumor activity in vitro and in in vivo models with KRASG12C mutation.

Abbreviations

- 5‐FU

5‐fluorouracil

- AUC

area under the time‐concentration curve

- CNS

central nervous system

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- FOLFOX

oxaliplatin/5‐FU/leucovorin

- Kpuu

concentration ratio of unbound drug in brain to blood

- LC‐MS/MS

liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry

- NSCLC

non‐small‐cell lung cancer

- PDX

patient‐derived xenograft

- TGI

tumor growth inhibition

- TSA

thermal shift assay

1. INTRODUCTION

Missense mutations of the small GTPase Ras are common activating mutations found in cancer and occur in 30% of human tumors. 1 Although the RAS gene family comprises three isoforms, KRAS, HRAS, and NRAS, 85% of RAS‐driven cancers are caused by mutations in the KRAS isoform. 2 KRAS mutations are observed in ~90% of pancreatic cancers, 40%–50% of CRCs, and 31%–35% of lung cancers. 3 Among the tumors with KRAS mutation, 80% of all oncogenic mutations occur within codon 12. 4 The mutation of KRAS at codon 12 compromises the GTPase activity of KRAS and prevents GTPase activating proteins from promoting hydrolysis of GTP on KRAS, resulting in KRAS accumulation in the GTP‐bound active form, and driving the abnormal growth of cancer cells. 5

The most frequent KRAS mutants at codon 12 included G12D (41%), G12V (28%), and G12C (14%). 2 , 4 KRASG12C mutation, an activating mutation in the KRAS gene, is believed to drive abnormal growth in multiple tumor types. 6 Overall, it is estimated that approximately 15% of NSCLC, 3% of CRC, and 1%–2% of numerous other solid tumors (including pancreatic, endometrial, bladder, ovarian, and small‐cell lung tumors) harbor the KRASG12C mutation. 7 , 8 KRASG12C mutation is usually involved in poor prognosis and therapy resistance. Patients with KRASG12C metastatic CRC have a poor prognosis in response to cancer therapies versus those patients with WT KRAS. 9 Therefore, this mutation presents an unmet clinical need for a promising target.

Through decades of research, we have learned the role of mutant KRAS as a central driver of tumorigenesis and mechanism for clinical resistance to certain therapies. Mutated KRAS protein has been recognized as an undruggable target until recently when new chemical entities were developed to bind it specifically. Early studies indicated that the binding pocket under the switch II region was exploitable for drug discovery, leading to the identification of more potent KRASG12C inhibitors with improved physiochemical properties. 10 Several clinical candidates have emerged that covalently bind to KRASG12C at the cysteine 12 residue, lock the protein in its inactive GDP‐bound conformation, inhibit KRAS‐dependent signaling, and elicit antitumor responses in clinical trials. Further clinical development has resulted in the accelerated approval of the first KRASG12C inhibitor sotorasib (AMG 510) for the treatment of adult patients with KRASG12C‐mutated locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC by the US FDA in May 2021. 11 The FDA also awarded breakthrough therapy designation to adagrasib (MRTX849) as a potential treatment for NSCLC patients with KRASG12C mutation after previous systemic therapy. 12 In addition, there are several other investigational compounds (e.g., JDQ443, GDC‐6036, LY3537982, MK‐1084, and JAB‐21822) targeting KRASG12C mutation currently in various stages of clinical development.

D‐1553 is a novel, potent, and selective KRASG12C inhibitor that is being developed as an oral agent for patients with solid tumors bearing KRASG12C mutation. In this preclinical study, we determined that D‐1553 has an inhibitory effect on the RAS–MEK signaling pathway and shows antitumor activity in cancer cell lines as well as mouse xenograft tumor models bearing KRASG12C mutation.

2. METHODS

2.1. Cell lines and reagents

All human cancer cell lines were purchased from ATCC and maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. The cells growing in an exponential growth phase were harvested and counted for plating or tumor inoculation. Carboplatin, cisplatin, oxaliplatin, and GDC‐0077 were purchased from MCE. D‐1553, sotorasib, and adagrasib were made in‐house. RPMI‐1640, McCoy's 5a, DMEM, minimum essential medium, nonessential amino acids solution, PBS, penicillin–streptomycin and 0.25% trypsin–EDTA were purchased from Gibco. Eagle's minimum essential medium was purchased from ATCC, insulin was from BI, and FBS was from Excell Bio.

2.2. Thermal shift assay

The TSA was carried out in a 96‐well LightCycler 480 real time fluorescence plate reader (Roche). A 20 μL sample was added into the MicroAmp Optical 96‐Well Reaction Plate (ABI#N8010560). The sample was heated from 30°C to 95°C with a thermal ramping rate of 0.03°C/s, and fluorescence signals were measured with excitation and emission at 465 nm and 580 nm.

2.3. Nucleotide exchange assay

The SOS1‐catalyzed nucleotide exchange assay was carried out in the 384‐well format using Alpha technology (Perkin Elmer). GDP‐bound human KRASG12C (a.a. 1–169) (160 nM) was preincubated with serial diluted compounds or DMSO control for 15 min at room temperature in assay buffer. Then, 320 nM SOS1 (a.a. 564–1049) and 160 μM GTP were added and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Finally, 200 nM cRAF‐RBD (a.a. 1–149), 50 μg/mL Alpha glutathione donor beads, and 50 μg/mL nickel chelate acceptor beads were added and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The AlphaLISA signal was then read on an Envision plate reader.

2.4. Cellular p‐ERK and p‐AKT assays

The advanced ERK phospho‐T202/Y204 kit (Cat# 64AERPEG; CisBio) and phospho‐AKT (Ser473) kit (Cat# 64AKSPEG; CisBio) were used for the highly sensitive quantification of ERK and AKT phosphorylation, respectively. Cells were seeded in a 384‐well plate, and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 overnight. Serial diluted compound or DMSO was added to the cells and incubated for 4 h. After removing cell supernatant, 50 μL lysis buffer was added and incubated for at least 30 min under shaking. Cell lysate (16 μL) was then transferred to the 384‐well detection plate, followed by addition of 4 μL premixed Ab. The plate was incubated for 2 h at room temperature prior to detection with excitation and emission at 320 nm and 665/620 nm.

2.5. Cell viability assays

Cells were seeded in 96‐well plates and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 overnight. Assay medium (100 μL) was added into the blank wells for low control. Serially diluted compound or DMSO was added to the cells and incubated for 5 days (except 3 days for A427, Panc 10.05, and SK‐LU‐1) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cell viability was detected according to the Promega CellTiter‐Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay Kit (Cat# G7573; Promega). Luminescence was recorded on the Tecan Spark plate reader.

2.6. Caco‐2 permeability and unbound fraction in plasma and brain tissue

Caco‐2 cells were seeded on 96‐well transport inserts and cultured for 22 days before being used for the transport experiment. D‐1553 or adagrasib was dosed bidirectionally at 10 μM with the transport buffer (HBSS). Permeation of the test compounds from A to B direction or B to A direction was determined in duplicate over a 120 min incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2 with a relative humidity of 95%. Samples were analyzed by LC‐MS/MS.

To determine protein binding, plasma or brain homogenate (from CD‐1 mouse) containing D‐1553 or adagrasib (1 μM) was dialyzed against phosphate buffer for 5 h in a 96‐well HTDialysis device at 37 ± 1°C. Following dialysis, samples were analyzed using LC‐MS/MS to determine the relative concentrations in plasma, brain, and buffer. The unbound fraction (fu) was calculated using the follow equation: fu = Cu/Ct, Cu as buffer drug concentration, which was considered as unbound, Ct as total concentration in plasma or brain.

2.7. Mouse plasma and brain pharmacokinetic analysis

Female Balbc nude mice were from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. Animals in each group, with 24 animals/group, were treated with D‐1553 or adagrasib at 30 mg/kg. Blood and brain samples were collected postdose. Plasma separation was achieved in 1 h after blood collection by centrifugation at 4000 g for 5 min at 4°C. The collected brain samples were homogenized with PBS at the ratio of 1:10 (1 g brain with 10 mL PBS). The samples were treated with protein precipitation. The samples were analyzed by LC‐MS/MS.

2.8. Calculation of mouse brain penetration efficiency Kpuu

Plasma AUC and brain AUC were calculated from time‐concentration profiles using Winnolin (8.3). Unbound drug AUC in plasma (AUCu,plasma) was calculated by multiplying total plasma concentration (AUCplasma) and unbound fraction in plasma (fu, plasma). Unbound drug AUC in brain (AUCu,brain) was calculated by multiplying total brain concentration (AUCbrain) and unbound fraction in brain. Then brain Kpuu was calculated as an index for drug CNS penetration by the following equation: Brain Kpuu = (AUCu,brain)/(AUCu,plasma).

2.9. In vivo xenograft animal model studies

Female BALB/c Nude mice (6–8 weeks) were purchased from Shanghai SIPPR‐BK Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. The cells growing in an exponential growth phase were harvested and counted for tumor inoculation. Mice were inoculated subcutaneously at the right flank with 1 × 107 cells in 0.1 mL PBS for tumor development. Patient‐derived xenograft models were carried out at CRO (CrownBio, Genendesign, and START). Tumor sizes were measured in two dimensions using a caliper, and the volumes were expressed in mm3 using the formula: V = 0.5 a × b 2 where a and b are the longest and shortest diameters of the tumor, respectively. The treatments were started when the tumor size reached ~200 mm3 for various xenograft models. Tumor growth inhibition was calculated according to the following equation: TGI (%) = (1 − (TVTreatment/Dn − TVTreatment/D0)/(TVControl/Dn − TVControl/D0)) × 100%, where Dn indicates the final tumor volume and D0 indicates starting tumor volume prior to treatment. Tumor regression was calculated with the following equation: Regression (%) = −(TVTreatment/Dn − TVTreatment/D0)/TVTreatment/D0 × 100%.

3. RESULTS

3.1. D‐1553 is a potent and selective KRASG12C inhibitor without axial chirality

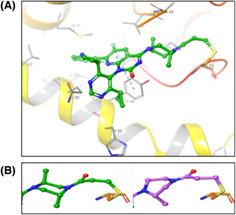

D‐1553 was developed as a covalent inhibitor of KRASG12C interacting with GDP bound‐KRASG12C without axial chirality. D‐1553 binds in the Switch II pocket with the acrylamide warhead covalently conjugated to C12 with a minimum energy conformation similar to the predicted bound conformation and confirmed by internal cocrystal structures of KRASG12C (Figure 1A). The di‐methyl substituted piperazine ring of D‐1553 results in a more potent compound. One of the symmetrically substituted cyclopropyl groups binds in the H95/Y96/Q99 pocket, while the other cyclopropyl group points towards the Switch II loop and occupies more hydrophobic pockets. The fluorosubstituted aniline group occupies the hydrophobic pocket formed by Val9, Met72, Tyr96, Ile100, and Val103. The two methyl groups on the piperazine ring not only help D‐1553 to adopt a low‐energy chair conformation, but also enhance the binding affinity by interacting with the G12C protein backbone. The C5 methyl group contacts with C12 and Y96, while the C2 methyl group fills an inner pocket, making additional contacts with T58 and A59. This di‐methyl substituted piperazine ring adjacent to the covalent warhead led to a conformational change in binding when compared to the published sotorasib X‐ray structure. The single methyl substituted piperazine ring of sotorasib's piperazine showed an unfavorable twist‐boat conformation, while the di‐methyl substituted piperazine ring of D‐1553 adopted a low‐energy chair conformation with two methyl substituents in opposite axial configuration (Figure 1B). In addition, the lipophilicity (log p) of D‐1553 is much lower than other KRASG12C inhibitors. This reduced lipophilicity can improve the free drug concentration in plasma, which will help brain penetration eventually.

FIGURE 1.

Structure and in vitro binding of D‐1553. (A) Cocrystal structure of D‐1553 bound to KRASG12C/GDP with 1.7 Å resolution. (B) The di‐methyl substituted piperazine ring of D‐1553 adopts a chair conformation (green) and the mono‐methyl substituted piperazine of AMG510 shows a twist‐boat conformation (violet). (C) Melting temperature shift (ΔTm) of D‐1553, sotorasib, and adagrasib bound to GDP‐bound KRASG12C in the thermal shift assay. Data are shown as mean ± SD from four independent experiments and each experiment had four replicates. ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001; one‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test.

To characterize the potency and specificity of D‐1553 in direct binding to KRASG12C, the TSA was carried out. Compared with other KRASG12C inhibitors (sotorasib, adagrasib), D‐1553 had a higher melting temperature shift (ΔTm), indicating the stronger binding of D‐1553 to GDP‐bound KRASG12C (Figure 1C, Figure S1A). D‐1553 had no shift with GDP‐bound WT KRAS (Figure S1B, Table S1), which suggested a highly selective binding of D‐1553 to KRASG12C over WT KRAS. All KRASG12C inhibitors (D‐1553, sotorasib, and adagrasib) had no shift with GMP‐PNP‐bound KRASG12C or WT KRAS (Figure S1C,D, Table S1).

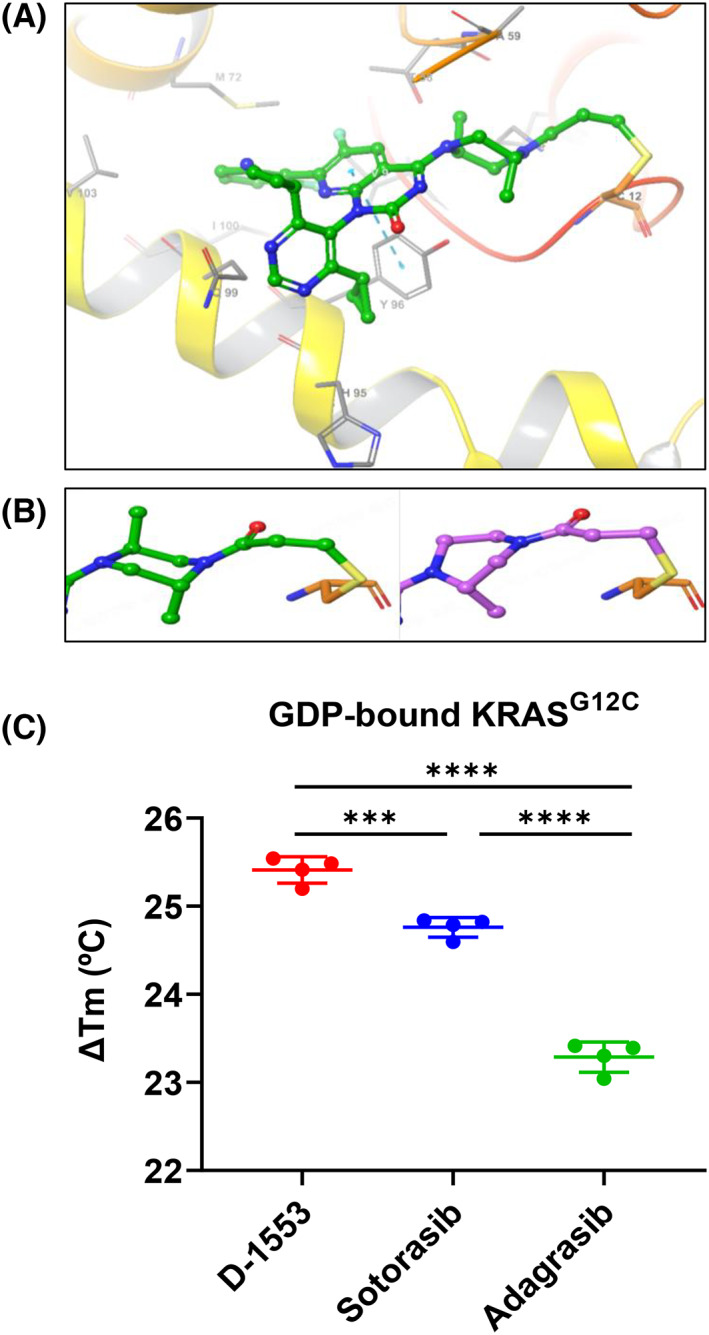

3.2. D‐1553 inhibits ERK signaling and in vitro cell growth

D‐1553 inhibited GDP to GTP conversion with an IC50 value of 18 nM, which was close to that of sotorasib (Figure 2A, Table S1). D‐1553, sotorasib and adagrasib showed dose‐dependent inhibition on the p‐ERK signaling in NCI‐H358 KRASG12C cell line (Figure 2B, Table S1). Conversely, these compounds failed to inhibit p‐ERK signaling in NCI‐H1993 KRASWT cell line (Figure S2A). The selectivity of D‐1553 shown in the binding assay was also confirmed in cellular systems, with selective and potent inhibition of growth of almost all KRASG12C cell lines, but not of the KRASG12D and KRAS WT cell lines (Figure 2C, Table S1). The antiproliferation effect of D‐1553 was slightly more potent than sotorasib and adagrasib in most KRAS G12C‐mutated cell lines.

FIGURE 2.

Inhibition of ERK signaling and in vitro cell growth by D‐1553. (A) A KRASG12C‐coupled nucleotide exchange assay was used to characterize the inhibitory effect of D‐1553 and sotorasib on KRASG12C mutation. Data are mean ± SD, n = 2 samples. (B) In NCI‐H358 cells, p‐ERK signal was determined using homogeneous time‐resolved fluorescence assay. Data are mean ± SD from three independent experiments and each experiment had three replicates. (C) Inhibition of D‐1553, sotorasib, and adagrasib on cell proliferation in a panel of KRASG12C, KRASG12D, or WT KRAS cell lines. KRAS and PIK3CA mutation status are from a public data source (DepMap Consortium). IC50 value was determined from three independent experiments and each experiment had three replicates. *p < 0.05 compared with D‐1553 in each cell line by two‐sided Student's t‐test.

Additionally, we investigated the inhibitory effect of D‐1553 on another important carcinogenic pathway, PI3K/AKT pathway. D‐1553 reduced the p‐AKT level in NCI‐H358 (KRASG12C, PIK3CAWT) cell line, but not in NCI‐H1993 (KRASWT, PIK3CAWT) cell line (Figure S2B,C, Table S2). The pan‐PI3K inhibitor GDC‐0077 reduced p‐AKT levels in both cell lines (Figure S2B,C, Table S2), while GDC‐0077 had a very weak inhibitory effect on cell proliferation (Figure S2D). These results are consistent with previous studies suggesting that Ras proteins can play an important role and interact with the PI3K p110 subunit to activate AKT, but PI3K activation is not entirely controlled by Ras. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16

3.3. D‐1553 has excellent brain penetration efficiency in mouse

For efflux substrates, brain Kpuu is a more reliable parameter than CSF Kpuu for estimating brain penetration efficiency, while CSF Kpuu tends to significantly overestimate the true brain penetration efficiency. 17 Therefore, brain Kpuu is used to calculate the CNS exposure of unbound drugs. Brain Kpuu of D‐1553 was determined along with adagrasib to predict their brain penetration efficiency. As shown in Table 1, both D‐1553 and adagrasib are efflux substrates with a similar efflux ratio (11–12), and this efflux ratio of adagrasib as we determined is consistent with the published information. 18 At the same dose of 30 mg/kg in nude mice, the brain Kpuu of D‐1553 and adagrasib were also very close, even though they had significant differences in free fraction and total exposure in plasma and brain tissue.

TABLE 1.

In vitro unbound brain exposure, brain Kpuu, of D‐1553 and adagrasib in mouse.

| D‐1553 | Adagrasib | D‐1553/adagrasib | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caco Papp (A–B) (10−6, cm/s) | 2.7 | 0.8 | 3 |

| Caco efflux ratio (1 μM) | 11 | 12 | 1 |

| fu, mouse plasma | 0.10 | 0.002 | 52 |

| fu, mouse brain | 0.07 | 0.001 | 90 |

| Mouse plasma AUC (μM h) at 30 mg/kg | 11.4 | 44.3 | 0.3 |

| Mouse brain AUC (eq μM h) at 30 mg/kg | 0.12 | 1.25 | 0.1 |

| Unbound plasma AUC (nM h) at 30 mg/kg | 1171 | 89 | 13 |

| Unbound brain AUC (nM h) at 30 mg/kg | 7.9 | 0.9 | 9 |

| Kpuu (unbound brain/unbound plasma) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1 |

Abbreviation: AUC, area under the time‐concentration curve.

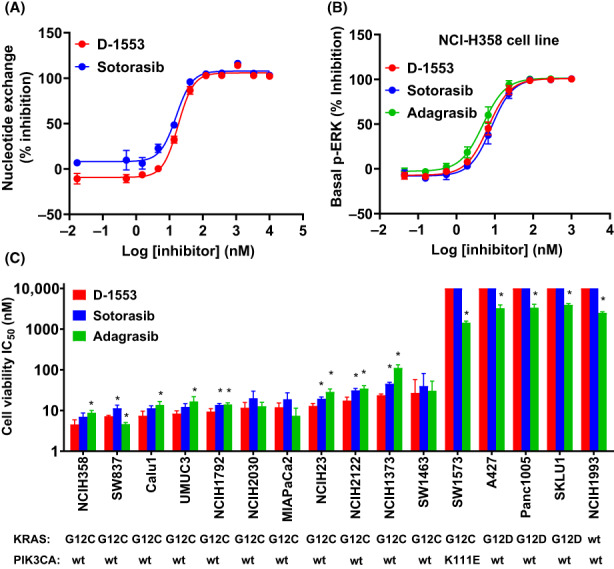

3.4. D‐1553 inhibits tumor growth in vivo in KRASG12C‐mutant xenograft tumor models

To evaluate the antitumor activity in KRASG12C‐mutant cancer models, a panel of cell line‐derived xenograft tumor models were studied. D‐1553 treatment (30 mg/kg) resulted in tumor regression in NCI‐H358 xenograft model and MIA PaCa‐2 xenograft model, with tumor regression value of −48% and −100%, respectively (Figure 3A,B, Table S3). D‐1553 (60 mg/kg) also significantly inhibited the growth of SW837 and NCI‐H2122 tumors, with TGI of 93% and 76%, respectively (Figure 3C,D, Table S3). All treatments were well tolerated with mice showing stable bodyweight, similar to the vehicle group (Figure S3). Taken together, D‐1553 is highly potent in human KRASG12C‐mutant cell line‐derived xenograft tumor models as a single agent.

FIGURE 3.

D‐1553 is highly potent in vivo in xenograft tumor models with KRASG12C mutation. Inhibition of tumor growth in mice bearing (A) NCI‐H358 KRASG12C‐mutated xenografts, (B) MIA PaCa‐2 KRASG12C‐mutated xenografts, (C) SW837 KRASG12C‐mutated xenografts, and (D) NCI‐H2122 KRASG12C‐mutated xenografts treated with D‐1553, sotorasib, or adagrasib. Data are shown as mean ± SEM, n = 8 mice per group; ****p < 0.0001 compared with vehicle; repeated‐measures ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison test. (E) Effect of D‐1553 (60 mg/kg) treatment on tumor growth in patient‐derived xenograft tumor models with KRASG12C mutation.

D‐1553 (60 mg/kg) was also evaluated in a large panel of PDX tumor models with KRASG12C mutation. D‐1553 showed TGI from 75% to 143% (Figure 3E, Figure S4–S6, Table S4). Tumor regression was observed in four lung cancer PDX models, two gastric cancer PDX models, one CRC PDX model, one pancreatic cancer PDX model, one ovarian cancer PDX model, and one bladder cancer PDX model.

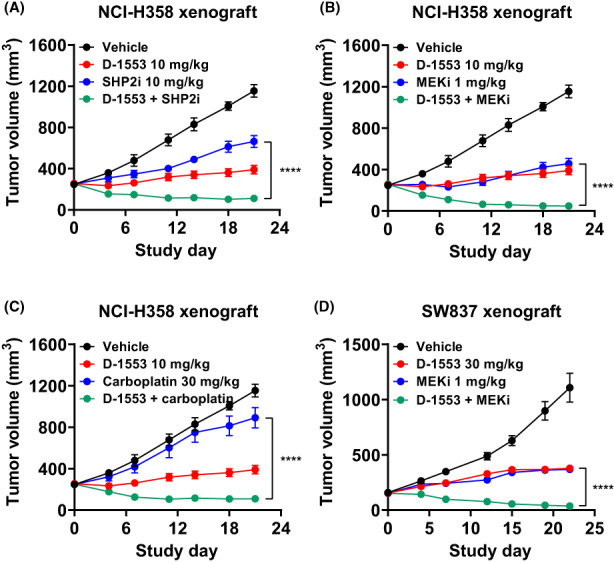

3.5. Combination of D‐1553 with chemotherapy or targeted agents enhances response in KRASG12C‐mutant cancer xenograft models

To support the clinical development of D‐1553, we undertook combination studies of D‐1553 with chemotherapy or targeted agents in cell‐derived xenograft and PDX models carrying KRASG12C mutation. In addition, in order to observe the synergistic effect of combination, the dose of D‐1553 was reduced. The lung cancer NCI‐H358 xenograft model treated with D‐1553 (10 mg/kg) in combination with MEK inhibitor (trametinib), SHP2 inhibitor (RMC‐4550), or carboplatin showed significant tumor growth inhibition or regression compared to either single agent alone (Figure 4A–C). Enhanced efficacy was also observed in the CRC SW837 xenograft model treated with the combination of D‐1553 (30 mg/kg) and MEK inhibitor (trametinib) (Figure 4D). Similar combination effects were also observed in multiple PDX models, including lung, colorectal, and bile duct cancer (Figures S7–S9).

FIGURE 4.

In vivo antitumor efficacy of D‐1553 in combination with chemotherapy or targeted agents in cell line‐derived xenograft tumor models with KRASG12C mutation. Inhibition of tumor growth in mice bearing NCI‐H358 KRASG12C‐mutated xenografts treated with D‐1553 either alone or in combination with (A) SHP2 inhibitor (SHP2i; RMC‐4550), (B) MEK inhibitor (MEKi; trametinib), or (C) carboplatin. For the convenience of observation, each group of drug combinations from one experiment are plotted separately. (D) Inhibition of tumor growth in mice bearing SW837 KRASG12C‐mutated xenografts treated with D‐1553 either alone or in combination with MEKi (trametinib). Data are shown as mean ± SEM, n = 8 mice per group. ****p < 0.0001 for combination treatment compared with the single agent; repeated‐measures ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison test.

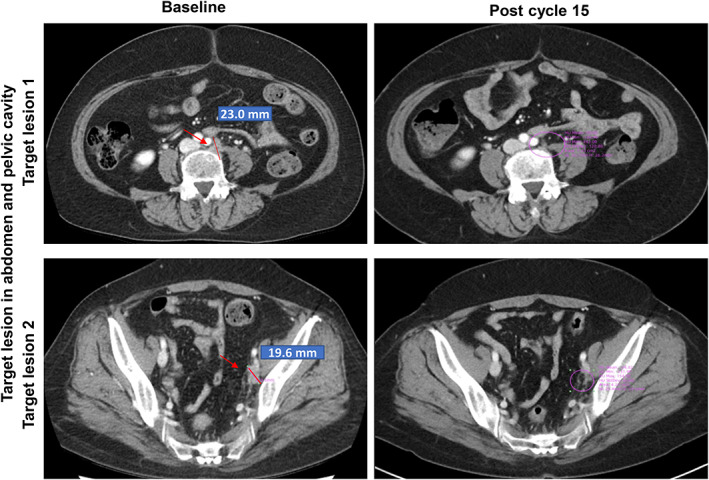

3.6. Evidence of D‐1553 and D‐1553 + chemotherapy clinical activity

A first‐in‐human clinical trial of D‐1553 (NCT04585035) is being undertaken to assess the safety, tolerability. and efficacy of D‐1553 alone or in combination with different therapies in patients with KRASG12C‐mutated solid tumors. In phase 1 of this study, among 21 evaluable patients (including 14 with CRC, 6 NSCLC, and 1 endometrial carcinoma), the confirmed objective response rate and disease control rate were 19.0% (4/21) and 85.7% (18/21), respectively. 19 Two cases of patients treated in this trial are provided here to illustrate the clinical antitumor activity of D‐1553 alone or in combination with FOLFOX chemotherapy.

3.6.1. Case 1

A 57‐year‐old Asian woman with metastatic KRASG12C‐mutated endometrial carcinoma had received two prior cancer surgeries and two lines of systemic treatments (carboplatin/paclitaxel and 5‐FU/cisplatin, respectively). She received D‐1553 monotherapy at 600 mg BID on a 21‐day cycle. After two cycles of treatment, she achieved partial response with a 52% reduction of target lesions compared with baseline. The partial response was confirmed on subsequent scans in cycle 4. Furthermore, from cycle 12, 100% tumor size reduction of target lesions was achieved based on computed tomography scan (Figure 5). The patient remained on study treatment for over 9 months without disease progression.

FIGURE 5.

Antitumor activities of D‐1553 in clinical case 1, a 57‐year‐old Asian woman with metastatic KRASG12C‐mutated endometrial carcinoma. Serial axial computed tomography images for clinical case 1. Red arrows indicate locations of tumors.

3.6.2. Case 2

A 59‐year‐old Asian man with metastatic KRASG12C mutated colon cancer with lung and liver metastases had not received any prior systemic treatments for metastatic disease. He received D‐1553 at 600 mg BID + FOLFOX on a 28‐day cycle. Partial response was observed after two cycles of treatment, with a 34.9% reduction of target lesions compared with baseline. The partial response was confirmed approximately 9 weeks later during the subsequent cycles and the patient continued on study treatment for more than 4 months without disease progression.

4. DISCUSSION

The development of selective inhibitors of KRASG12C mutant allowed the specific targeting of tumor cells with this mutation rather than normal cells, thus making a previously undruggable target sensitive to a targeted therapy. Sotorasib was the first KASG12C inhibitor conditionally approved by the FDA in May 2021 for the treatment of adult patients with advanced NSCLC. 11 Several other KRASG12C inhibitors, for example, adagrasib, JAB‐21822, JDQ443, and GDC‐6036, are also being developed in various stages of clinical trials. Preclinical evaluation of sotorasib, adagrasib, and JDQ443 have been reported previously. 10 , 20 , 21

We have developed D‐1553, an orally bioavailable, potent, and selective covalent inhibitor of GDP‐bound KRASG12C. In this report, D‐1553 strongly bound to GDP‐bound KRASG12C and potently inhibited KRASG12C cellular signaling and proliferation in a mutant‐selective manner. Importantly, D‐1553 showed no activity in KRASG12D or KRASWT tumor cell lines, indicating that D‐1553 is a highly selective KRASG12C inhibitor. These features of D‐1553 resulted in a potent antitumor activity profile in various cancer‐derived xenograft models including lung, colorectal, pancreatic, bile duct, and ovarian cancers, further indicating its broad activities in different types of solid tumors with KRASG12C mutation.

From a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic point of view, the in vivo efficacy against tumor lesions in the brain was determined by the ratio of the absolute brain exposure of unbound drug to its intrinsic potency. Encouraging results for adagrasib have been reported both in a preclinical brain tumor model and clinical brain metastases. 18 The IC50 values of D‐1553 and adagrasib, which reflect their potency against targets, were similar in different KRAS mutated cell lines. However, the absolute unbound brain exposure in human was different for these drugs, with D‐1553 having a higher unbound brain exposure than adagrasib, as indicated by the usual equation to estimate the brain exposure: AUCu,brain = AUCu,plasma × brain Kpuu. Even though the brain Kpuu values of D‐1553 and adagrasib were very close to each other, the unbound fraction of D‐1533 in plasma (AUCu,plasma) was higher than that of adagrasib. It is expected that D‐1553 can reach a high unbound exposure in brain tissue. Therefore, it is a good candidate for prevention and treatment of brain metastases in patients.

KRAS is one of the three major isoforms of the RAS family, with 85% of RAS‐driven cancers having KRAS mutation. 2 Receptor tyrosine kinase activation leads to RAS activation, which can then transmit highly diverse signals by binding to several downstream effectors. 22 The MAPK pathway is one of the most characterized pathways regulated by RAS. 22 Directly targeting mutant KRAS provides the first potential therapy opportunity for patients with KRAS mutation. However, emergence of adaptive feedback resistance could cause considerable vulnerabilities in clinical therapy targeting the RAS‐MAPK pathway. 23 Preclinical experiments have provided compelling evidence that combining a KRASG12C inhibitor with an EGFR inhibitor results in greater antitumor effects than either agent alone in KRASG12C CRC cells. 24 Adagrasib has been shown to be well tolerated when combined with anti‐EGFR Ab cetuximab and shows promising clinical activity in heavily pretreated patients with KRASG12C mutated CRC. 25 Thus, identifying potential combination therapy that could achieve durable and significant responses and delay resistance is key to the success of KRASG12C inhibitor therapy.

Combination therapy that suppresses adaptive feedback has proven to be the key to optimizing the frequency and durability of tumor response. 26 , 27 , 28 The MEK inhibitor trametinib has been approved in combination with BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib for treating patients with BRAFV600E mutated NSCLC. 28 In KRAS‐mutant tumor cell lines, trametinib has been shown to synergize with ARS‐1620, a KRASG12C inhibitor. 29 In addition, similar synergistic antitumor activity was observed in vivo with sotorasib in combination with MEK inhibitor (PD‐0325901). 20 Previous studies also reported that ERK remains as a key node in regulating pathway reactivation in the context of MEK inhibition. 30 , 31 , 32 Thus, it is hypothesized that deeper and more durable efficacy could be achieved by targeting two nodes concurrently rather than one. In line with this hypothesis, Merchant et al. showed that combined MEK and ERK inhibitor could lead to better tumor regression in KRAS mutant NSCLC cells. 33 In our study, phosphorylation of ERK or AKT was inhibited by D‐1553 treatment in KRASG12C cells, indicating that D‐1553 can block the downstream signaling, including ERK and AKT, from activated KRASG12C. Furthermore, the combination of D‐1553 and trametinib resulted in a strong synergistic antitumor activity in colorectal and bile duct cancer xenograft models.

SHP2 is a key phosphatase that can activate the RAS‐MAPK pathway by recruiting GRB2/SOS to receptor tyrosine kinases and increasing RAS–RAF association through dephosphorylation of tyrosine‐phosphorylated RAS, and can also facilitate the reactivation of RAS signaling after KRASG12C inhibition. 23 Combinations of adagrasib with SHP2 inhibitor RMC‐4550 showed significant antitumor efficacy in esophageal squamous carcinoma and lung cancer models. 10 KRASG12C inhibitor ARS‐1620 in combination with SHP2 inhibitor SHP099 led to sustained RAS pathway inhibition and enhanced efficacy in vitro and in vivo. 29 In addition, SHP099 and ARS‐1620 in combination conferred a substantial survival benefit in syngeneic KRASG12C mutant pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and NSCLC models. 34 Similar to these reports, the combination of D‐1553 and RMC‐4550 showed potent antitumor efficacy that was superior to treatment with either single agent in the lung cancer xenograft model in this study. Taken together, we showed that combining KRASG12C inhibitor with agents targeting the adaptive feedback, that is, SHP2 inhibitor and MEK inhibitor, could further suppress RAS signaling and enhance tumor suppression. Exploring other combinations of KRASG12C inhibitor with approved therapies might also be key to maximizing the antitumor efficacy. Our study also showed a synergistic effect when D‐1553 was combined with chemotherapy drugs. This finding suggests a potential development strategy of combining KRASG12C inhibitor with standard‐of‐care chemotherapeutic agents, and warrants further evaluation in clinical trials.

D‐1553 is currently in clinical development as a monotherapy and in combination with other therapies (NCT04585035). Here we report two clinical cases showing antitumor activity of D‐1553 as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy. The first case is particularly notable given that this patient with endometrial carcinoma had not benefited from prior standard‐of‐care chemotherapies. D‐1553 monotherapy in this case resulted in strong antitumor activity with 100% tumor size reduction of target lesions of her KRAS G12C ‐mutated cancer. In the other case, the synergistic effect between D‐1553 and chemotherapy was confirmed in a patient with advanced colon cancer with lung and liver metastases harboring KRAS G12C mutation.

In conclusion, D‐1553 is a potent and highly selective KRASG12C inhibitor. It has shown tumor growth inhibition in preclinical studies in vitro and in vivo. These data suggest that D‐1553 is suitable for clinical development targeting cancers with KRASG12C mutation. D‐1553 is currently in a phase II clinical trial evaluating its efficacy in patients with advanced solid tumors harboring KRASG12C mutation (NCT04585035).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Except for Seok Jae Huh, the authors are current employees of Inventisbio. The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Approval of the research protocol by an institutional review board: N/A.

Informed consent: Signed informed consent was obtained from patients.

Registry and registration no. of the study/trial: N/A.

Animal studies: All the procedures related to animal handling, care, and treatment in this study were performed according to the guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Shanghai SIPPR‐BK Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. following the guidance of the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). This study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Council for Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, and applicable local regulatory requirements.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Partial PDX experiment services were provided by Emily Robb, Alyssa Moriarty, and Michael Wick (XenoSTART).

Shi Z, Weng J, Niu H, et al. D‐1553: A novel KRASG12C inhibitor with potent and selective cellular and in vivo antitumor activity. Cancer Sci. 2023;114:2951‐2960. doi: 10.1111/cas.15829

REFERENCES

- 1. Bos JL. ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4682‐4689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lanman BA, Allen JR, Allen JG, et al. Discovery of a covalent inhibitor of KRAS(G12C) (AMG 510) for the treatment of solid tumors. J Med Chem. 2020;63:52‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Prior IA, Hood FE, Hartley JL. The frequency of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 2020;80:2969‐2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prior IA, Lewis PD, Mattos C. A comprehensive survey of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2457‐2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Downward J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:11‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hong DS. Targeting the KRAS G12C mutation in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2019;17:612‐614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Neumann J, Zeindl‐Eberhart E, Kirchner T, Jung A. Frequency and type of KRAS mutations in routine diagnostic analysis of metastatic colorectal cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2009;205:858‐862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tate JG, Bamford S, Jubb HC, et al. COSMIC: the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D941‐D947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Van Cutsem E, Köhne C‐H, Láng I, et al. Cetuximab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as first‐line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: updated analysis of overall survival according to tumor KRAS and BRAF mutation status. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2011‐2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hallin J, Engstrom LD, Hargis L, et al. The KRAS(G12C) inhibitor MRTX849 provides insight toward therapeutic susceptibility of KRAS‐mutant cancers in mouse models and patients. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:54‐71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. FDA approves first KRAS inhibitor: sotorasib. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:OF4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mirati Therapeutics' Adagrasib Receives Breakthrough Therapy Designation from U.S. Food and Drug Administration for Patients with Advanced Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer Harboring the KRASG12C Mutation. 2021. https://ir.mirati.com/press‐releases/press‐release‐details/2021/Mirati‐Therapeutics‐Adagrasib‐Receives‐Breakthrough‐Therapy‐Designation‐from‐U.S.‐Food‐and‐Drug‐Administration‐for‐Patients‐with‐Advanced‐Non‐Small‐Cell‐Lung‐Cancer‐Harboring‐the‐KRAS‐G12C‐Mutation/default.aspx

- 13. Adachi Y, Ito K, Hayashi Y, et al. Epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition is a cause of both intrinsic and acquired resistance to KRAS G12C inhibitor in KRAS G12C‐mutant non‐small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:5962‐5973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fruman DA, Chiu H, Hopkins BD, Bagrodia S, Cantley LC, Abraham RT. The PI3K pathway in human disease. Cell. 2017;170:605‐635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Castellano E, Downward J. RAS interaction with PI3K: more than just another effector pathway. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:261‐274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Janku F, Yap TA, Meric‐Bernstam F. Targeting the PI3K pathway in cancer: are we making headway? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:273‐291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nagaya Y, Katayama K, Kusuhara H, Nozaki Y. Impact of P‐glycoprotein‐mediated active efflux on drug distribution into lumbar cerebrospinal fluid in nonhuman primates. Drug Metab Dispos. 2020;48:1183‐1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sabari JK, Velcheti V, Shimizu K, et al. Activity of Adagrasib (MRTX849) in brain metastases: preclinical models and clinical data from patients with KRASG12C‐mutant non‐small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28:3318‐3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Price T, Grewal J, Abed A, et al. Abstract CT504: a phase 1 clinical trial to evaluate safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics (PK) and efficacy of D‐1553, a novel KRASG12C inhibitor, in patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumor harboring KRASG12C mutation. Cancer Res. 2022;82:CT504. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Canon J, Rex K, Saiki AY, et al. The clinical KRAS(G12C) inhibitor AMG 510 drives anti‐tumour immunity. Nature. 2019;575:217‐223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weiss A, Lorthiois E, Barys L, et al. Discovery, preclinical characterization, and early clinical activity of JDQ443, a structurally novel, potent and selective, covalent oral inhibitor of KRASG12C. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:1500‐1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McKay MM, Morrison DK. Integrating signals from RTKs to ERK/MAPK. Oncogene. 2007;26:3113‐3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chakraborty A. KRASG12C inhibitor: combing for combination. Biochem Soc Trans. 2020;48:2691‐2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xue JY, Zhao Y, Aronowitz J, et al. Rapid non‐uniform adaptation to conformation‐specific KRAS(G12C) inhibition. Nature. 2020;577:421‐425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adagrasib data create buzz at ESMO. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Corcoran RB, Andre T, Atreya CE, et al. Combined BRAF, EGFR, and MEK inhibition in patients with BRAF(V600E)‐mutant colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:428‐443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Flaherty KT, Infante JR, Daud A, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1694‐1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Planchard D, Besse B, Groen HJM, et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with previously treated BRAF(V600E)‐mutant metastatic non‐small cell lung cancer: an open‐label, multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:984‐993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ryan MB, Fece de la Cruz F, Phat S, et al. Vertical pathway inhibition overcomes adaptive feedback resistance to KRAS(G12C) inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:1633‐1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Manchado E, Weissmueller S, Morris JP, et al. A combinatorial strategy for treating KRAS‐mutant lung cancer. Nature. 2016;534:647‐651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rebecca VW, Alicea GM, Paraiso KH, Lawrence H, Gibney GT, Smalley KS. Vertical inhibition of the MAPK pathway enhances therapeutic responses in NRAS‐mutant melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:1154‐1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kitai H, Ebi H, Tomida S, et al. Epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition defines feedback activation of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling induced by MEK inhibition in KRAS‐mutant lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:754‐769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Merchant M, Moffat J, Schaefer G, et al. Combined MEK and ERK inhibition overcomes therapy‐mediated pathway reactivation in RAS mutant tumors. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0185862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fedele C, Li S, Teng KW, et al. SHP2 inhibition diminishes KRASG12C cycling and promotes tumor microenvironment remodeling. J Exp Med. 2021;218:e20201414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1