Abstract

Background

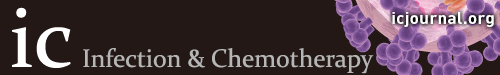

Tuberculous peritonitis is difficult to diagnose due to its non-specific clinical manifestations and lack of proper diagnostic modalities. Current meta-analysis was performed to find the overall diagnostic accuracy of adenosine deaminase (ADA) in diagnosing tuberculous peritonitis.

Materials and Methods

PubMed, Google Scholar, and Cochrane library were searched to retrieve the published studies which assessed the role of ascitic fluid ADA in diagnosing tuberculous peritonitis from Jan 1980 to June 2022. This meta-analysis included 20 studies and 2,291 participants after fulfilling the inclusion criteria.

Results

The pooled sensitivity was 0.90 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.85 - 0.94) and pooled specificity was 0.94 (95% CI: 0.92 - 0.95). The positive likelihood ratio was 15.20 (95% CI: 11.70 - 19.80), negative likelihood ratio was 0.10 (95% CI: 0.07 - 0.16) and diagnostic odds ratio was 149 (95% CI: 86 - 255). The area under the summary receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.97. Cut- off value and sample size were found to be the sources of heterogeneity in the mete-regression analysis.

Conclusion

Ascitic fluid ADA is a useful test for the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis with good sensitivity and specificity however, with very low certainty of evidence evaluated by Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach. Further well- designed studies are needed to validate the diagnostic accuracy of ascitic fluid ADA for tuberculous peritonitis.

Keywords: Ascitic fluid, ADA, Tuberculous peritonitis, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a bacterial disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It is a potentially life-threatening disease with very high worldwide burden in terms of morbidity and mortality [1]. TB affects all age groups and can involve any organ system of body. Usually, these bacteria infect lungs and cause pulmonary tuberculosis, but the bacteria may also disseminate to other organs and cause extrapulmonary TB [2]. Extrapulmonary TB cases account for 15% of all the cases of tuberculosis [3] and out of these, abdomen is involved in 11% cases [4]. Abdominal TB may affect gastrointestinal lumen, lymph nodes, abdominal viscera, and peritoneum [5]. Peritoneal TB or tuberculous peritonitis means that the infection due to M. tuberculosis has resulted in inflammation of the peritoneum, which may cause local complications like adhesions and subacute intestinal obstruction, or may lead to systemic complications and death by spreading in blood circulation, if not treated. Tuberculous peritonitis has emerged as a salient disease-causing morbidity and mortality due to its resemblance to other diseases and delay in diagnosis. For example, other conditions like cirrhosis and carcinomas can mimic TB and create confusion in the diagnosis. More than 90% of tuberculous peritonitis patients present with ascites, while others may present with fever and abdominal pain. Ascitic fluid analysis is done for diagnosis [6]. The ascitic fluid in tubercular infection shows high protein content (>3 g/dL), and 150 – 4,000/mm3 of cells with lymphocytic predominance. The ratio obtained by dividing ascitic fluid glucose to blood glucose is below 0.96 and the gradient between serum albumin and ascitic fluid albumin is below 1.1 g/d. Hematologic findings are nonspecific [7]. So, there is a major problem in diagnosing peritoneal tuberculosis because the clinical manifestations are non-specific and these laboratory test results overlap with other diseases. Although, culture of the tuberculous bacteria is regarded as the gold standard test, but it is challenging to detect the bacteria by culture due to their slow growth [8]. Therefore, many clinicians prefer a combination of clinical examination with other methods such as laparoscopic biopsy and histopathological examination of peritoneal tissue (which may reveal caseation necrosis), acid-fast bacilli (AFB) staining, along with radio imaging techniques like computed tomography (CT) scan of abdomen for the diagnosis [8]. But all these methods are either time consuming, expensive, less sensitive, invasive, or non-specific and thus are ineffective to use in daily practice. While CT scan shows non-specific findings, both culture and smear mostly fail to give positive results. Not more than 3% cases show positive AFB smear, while just 20% show culture positivity [2]. Hence, there is still an absence of a simple and economical diagnostic test for diagnosing peritoneal tuberculosis [9].

Tubercular peritonitis shows raised levels of ascitic fluid adenosine deaminase (ADA) up to more than 36 U/L. While serum levels of ADA are also elevated to more than 54 U/L, the ratio of ascitic fluid ADA to serum ADA is above 0.98. The presence of all these findings suggests tuberculosis [10]. ADA acts as a catalytic enzyme in the deamination of adenosine nucleosidases to inosine nucleosidases. ADA is extensively found in lymphocytes and stimulation of lymphocytes increases ADA activity in body fluids [10]. This stimulation of lymphocytes is caused by the tubercular bacteria which activates cellular immune response and in turn increases ADA levels. This activity of ADA is used as a test in ascitic fluid for diagnosing tuberculous peritonitis. The determination of ADA levels is a fast, easy, readily available, cost-efficient, and minimally invasive test [11]. Previously available systemic reviews and meta-analyses have also shown the diagnostic role of ascitic fluid ADA in patients of peritoneal tuberculosis with good accuracy [12,13,14]. Since then, many new studies have been performed and new methods of meta-analysis have been recommended. Therefore, this updated meta-analysis was conducted after including newer studies and using most recent and recommended meta-analysis methods to find the overall diagnostic accuracy of ascitic fluid ADA for using it as a convenient and effective marker in the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis.

Materials and Methods

We performed this updated meta-analysis in accord with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [15]. The protocol for this meta-analysis was registered in PROSPERO 2022 with registration number CRD42022341909.

1. PICO tool was used to formulate the research question of our study, which includes

Patients: Cases of tuberculous peritonitis as defined in individual studies.

Index test: Ascitic fluid ADA levels.

Comparator (or gold standard): Criteria used to diagnose tuberculous peritonitis as per individual studies.

Outcome: Diagnostic accuracy of ADA determined by pooled sensitivity and specificity.

2. Search strategy

PubMed, Google Scholar, and Cochrane library were used as search engines by two independent reviewers to systematically search and retrieve the published studies which assessed the role of ascitic fluid ADA in diagnosing tuberculous peritonitis from January 1980 to June 2022. We used, ascitic fluid AND ADA OR adenosine deaminase AND mycobacterium tuberculosis OR tuberculous AND peritonitis AND sensitivity as key words to search the studies. The filter to search restricted to human was applied. The references of related articles were also searched to find out any missing study.

3. Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria: Studies which met following inclusion criteria were included: Studies reporting sufficient data to determine pooled sensitivity and pooled specificity for diagnosing tuberculous peritonitis, studies reporting data in English language, studies conducted in patients with age more than 18 years, and studies which are published as full text article.

Exclusion criteria: Editorials, case reports, conference proceedings, and pre-print letters to editor were excluded.

The eligibility of studies was assessed by two independent reviewers and any disparity if present was solved by consensus.

4. Quality assessment of studies

Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2 (QUADAS-2) was used to assess the methodological quality of studies and risk of bias [16]. It is an evidence-based tool used for assessing the qualities of the diagnostic accuracy studies in systematic reviews, which includes four key domains: patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing. The risk of bias is categorised as high, low, or unclear risk. In case of disparity, a third reviewer was assigned to discuss and reach a conclusion.

5. Data extraction

The assessment of the final collection of articles was carried out by two independent reviewers who extracted the following data from the studies: author’s name, year of study, ethnicity of patients, mean age of patients, number of study participants (TBP and Non-TBP), reference standard or gold standard for diagnosis of TBP, study design and data collection method (prospective or retrospective), ADA assay method, cut-off value, true positive, false negative, true negative, false positive and sensitivity and specificity data. Any disparity, if present was settled by discussion with a third reviewer. In case, if any information was not present in the articles, the term “Not Available or NA” was used to label it.

6. Statistical analysis

The standard method which is recommended for the meta-analysis of diagnostic tests was used in this meta-analysis. Accuracy of ADA in diagnosing tuberculous peritonitis was assessed by calculating pooled sensitivity and specificity with 95% confidence interval (CI), using random-effects model. The effectiveness of ascitic fluid ADA as a diagnostic test was assessed by calculating diagnostic odds ratio (DOR). Positive likelihood ratios (PLR) and negative likelihood ratios (NLR) were also computed. The discriminatory accuracy of ascitic fluid ADA in diagnosing tuberculous peritonitis was assessed by forming summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve [17]. I2 statistics and Chi-square tests were used to assess heterogeneity among the study groups, where a value of >50% suggested presence of heterogeneity. Meta-regression and subgroup analyses were performed to check source of possible heterogeneity. The variables taken in meta-regression analysis included: cut-off value of ADA (categorical variable [≤30/>30 U/L]), sample size (categorical variable [≤115/>115]), mean age (continuous variable, in years), gender (categorical variable [male/female]), ethnicity (categorical variable [Asian/Caucasian]), reference standard (categorical variable [with/without radio-imaging]), ADA assay method (categorical variable [Giusti/Non-Giusti]), and data collection (categorical variable [prospective/retrospective]). Deek’s funnel plot was used for checking publication bias [18]. The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was used to work out the certainty of evidence for the ascitic fluid ADA as a diagnostic marker of tuberculous peritonitis. The analysis of data in our study was done using Stata version 13 (Stata Corp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). The risk of bias was assessed using Review Manager version 5.4.1 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Results

1. Study selection

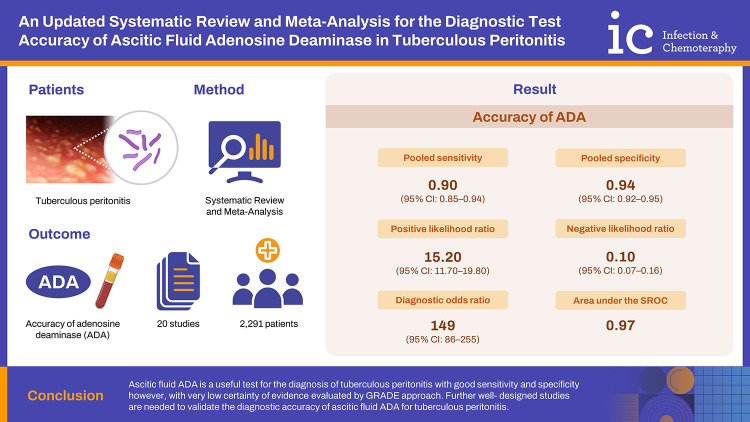

753 records were identified by electronic database and search engines from which duplicate and ineligible studies were excluded, leaving 534 studies for screening. Out of these, irrelevant studies and studies with insufficient data were excluded, leaving 65 records for eligibility assessment. After further exclusions based on the type of study, 11 eligible studies were obtained which were added to the 9 studies taken from previous versions of the review, leaving 20 studies for final data analysis. PRISMA chart for study selection and inclusion process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Study flow diagram (PRISMA) representing the study selection and inclusion.

2. Characteristics of studies included

The summary of the studies [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] included in this meta-analysis is shown in Table 1. The average sample size for the final 20 studies was 115 (16 - 368), and the total sample size was 2,291. Mean age of the patients ranged between 34.5 and 62 years. Out of 20, 6 studies had patients of Caucasian origin, while 14 studies had Asian patients. For the measurement of ascitic fluid ADA, 6 studies each used Giusti and 1 modified-Giusti method, 7 studies have used newer methods (non-Giusti) while, 6 studies did not reveal the assay method used for ADA determination. The cut-off value of ADA for diagnosing tuberculous peritonitis was >30 IU/l in 10 studies and ≤30 IU/l in the other 10 studies. The data collection was prospective in 13 studies and retrospective in 7 studies. The diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis was established by different methods like clinical examination including response to treatment, bacteriological (ascitic fluid culture/AFB staining) examination, histopathological examination of tissue, and radio-imaging techniques like CT scan of abdomen in different studies.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

| Study No. | First author | Year | Ethnicity | Study participants | Mean age (years) | Reference standard | ADA assay method | Cut-off value (U/L) | Data collection | Sn (%) | Sp (%) | TP | FN | TN | FP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBP | Non-TBP | |||||||||||||||

| 1 | Blake J [19] | 1982 | Caucasian | 2 | 14 | NA | CD + B + HP + RI | Kinetic method | 30 | P | 100.0 | 100.0 | 2 | 0 | 14 | 0 |

| 2 | Bhargava DK [20] | 1990 | Asian | 17 | 70 | NA | CD + B + HP + RI | Giusti | 36 | P | 100.0 | 97.0 | 17 | 0 | 68 | 2 |

| 3 | Brant CQ [21] | 1995 | Caucasian | 8 | 36 | NA | B + HP | Giusti | 31 | P | 100.0 | 92.0 | 8 | 0 | 33 | 3 |

| 4 | Hillebrand DJ [22] | 1996 | Caucasian | 17 | 351 | NA | B | Beckman DU-7 spectrophotometer | 7 | R | 58.8 | 95.4 | 10 | 7 | 335 | 16 |

| 5 | Sathar MA [23] | 1999 | Caucasian | 23 | 22 | 34.5 | CD + HP | Kinetic enzyme-coupled assay | 30 | P | 96.0 | 100.0 | 22 | 1 | 22 | 0 |

| 6 | Burgess LJ [24] | 2001 | Caucasian | 18 | 160 | NA | CD + B + HP | Giusti | 30 | P | 94.0 | 92.0 | 17 | 1 | 147 | 13 |

| 7 | Sharma SK [25] | 2006 | Asian | 31 | 88 | 40.4 | CD + B + HP | Giusti | 37 | P | 96.8 | 94.3 | 30 | 1 | 83 | 5 |

| 8 | Hong KD [26] | 2011 | Asian | 35 | 17 | NA | CD + B + HP | NA | 30 | R | 89.0 | 82.0 | 31 | 4 | 14 | 3 |

| 9 | Kang SJ [27] | 2012 | Asian | 27 | 25 | 59.7 | B + HP + RI | NA | 21 | R | 92.0 | 85.0 | 25 | 2 | 21 | 4 |

| 10 | Saleh MA [28] | 2012 | Caucasian | 14 | 27 | 51.7 | CD + B + RI | Giusti | 35 | P | 100.0 | 92.6 | 14 | 0 | 25 | 2 |

| 11 | Huang HJ [29] | 2014 | Asian | 12 | 25 | 58.3 | CD + B | NA | 30 | R | 66.7 | 100.0 | 8 | 4 | 25 | 0 |

| 12 | Ali N [30] | 2014 | Asian | 24 | 6 | 36.7 | CD + HP | NA | 24 | P | 87.5 | 83.3 | 21 | 3 | 5 | 1 |

| 13 | Shadia K [31] | 2015 | Asian | 10 | 8 | NA | CD + B + RI | Modified Giusti | 40 | P | 70.0 | 100.0 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 0 |

| 14 | Lee JY [32] | 2015 | Asian | 45 | 29 | 55.1 | CD + B + HP + RI | NA | 21 | P | 82.0 | 79.0 | 37 | 8 | 23 | 6 |

| 15 | Liu R [33] | 2020 | Asian | 115 | 76 | NA | CD + B + HP | Giusti | 31.5 | R | 89.6 | 92.1 | 103 | 12 | 70 | 6 |

| 16 | Kumabe A [34] | 2020 | Asian | 8 | 173 | 62 | CD + B + HP | NA | 40 | R | 100.0 | 96.0 | 8 | 0 | 166 | 7 |

| 17 | Nguyen HM [35] | 2020 | Asian | 17 | 26 | 54.5 | B + HP | Enzyme kinetic method | 30.2 | P | 100.0 | 88.5 | 17 | 0 | 23 | 3 |

| 18 | Sun J [36] | 2021 | Asian | 132 | 147 | NA | CD + B + HP + RI | Peroxidase assay f/b colorimetric testing | 21 | R | 83.3 | 95.2 | 110 | 22 | 140 | 7 |

| 19 | Dahale AS [37] | 2021 | Asian | 78 | 208 | 38.03 | CD + B + HP | Slaats method | 41.1 | P | 95.0 | 93.0 | 74 | 4 | 193 | 15 |

| 20 | Thiruveedhula CS [38] | 2022 | Asian | 21 | 129 | 40.8 | B | ADA-MTB kit | 40 | P | 85.7 | 98.4 | 18 | 3 | 127 | 2 |

TBP, tuberculous peritonitis; ADA, adenosine deaminase; Sn, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; TP, true positive; FN, false negative; TN, true negative; FP, false positive; NA, data not available; CD, clinical diagnosis; B, bacteriological (ascitic fluid culture/acid-fast bacilli staining) examination; HP, histopathological; RI, radio-imaging (computed tomography scan of abdomen); P, prospective; R, retrospective; MTB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

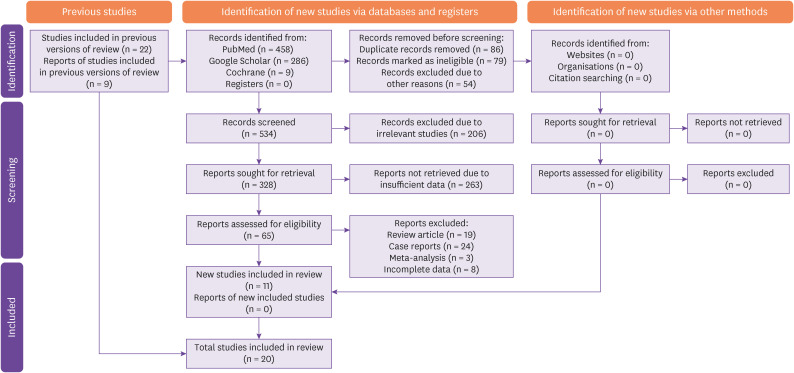

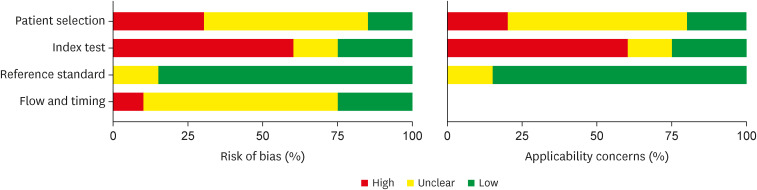

3. Methodological quality assessment

The results of assessment of risk of bias by QUADAS-2 are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. These results show that maximum risk of bias (50%) was observed in the index test domain as pre-defined cut-off values for ADA to diagnose tuberculous peritonitis were not set in maximum studies and blinding was not done for reference standard test results. Another domain where the risk of bias was revealed in this assessment was the patient selection domain as the sampling methods were not specified in most studies and case-control designs were not avoided.

Figure 2. Risk of bias for individual studies.

Figure 3. Summary risk of bias for each domain.

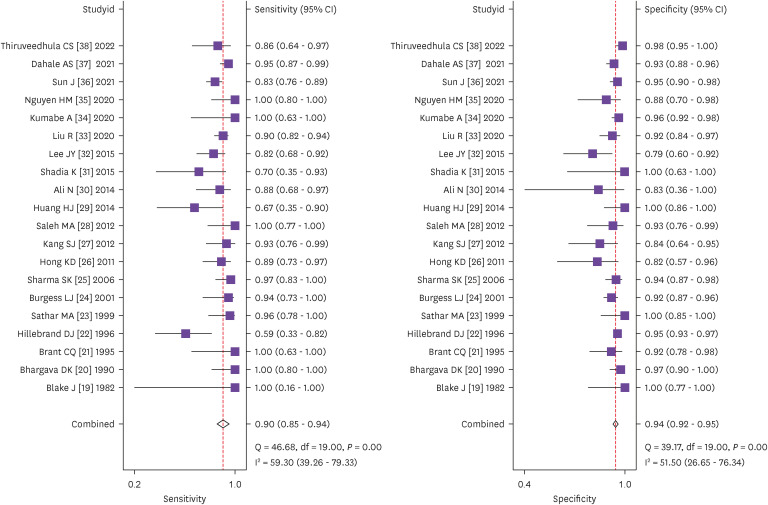

4. Diagnostic accuracy of ADA for TBP

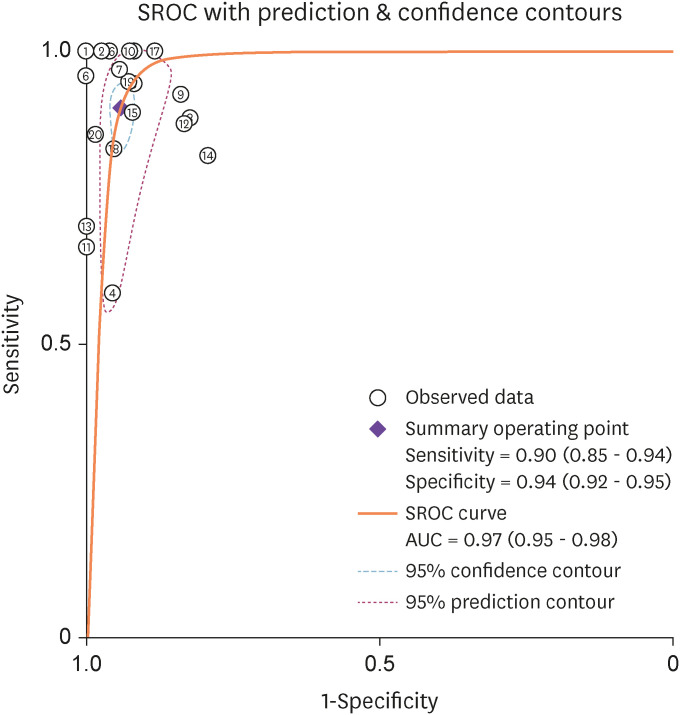

We performed heterogeneity analysis to select the appropriate model for calculation and it showed I2 values of 59.3% and 51.5% for sensitivity and specificity respectively, which suggests presence of significant heterogeneity among the studies. Hence, we used random effects model for our meta- analysis. The forest plots of the sensitivity and specificity of ascitic fluid ADA assay in diagnosing TBP are shown in Figure 4. The data computed from 20 included studies having total 2,291 patients showed pooled sensitivity of 0.90 (95% CI: 0.85 - 0.94), pooled specificity of 0.94 (95% CI: 0.92 - 0.95), and the DOR of 149 (95% CI: 86 - 255). The results of pooled analyses suggest clinically important diagnostic value of ascitic fluid ADA for tuberculous peritonitis. The discriminatory accuracy of ascitic fluid ADA to diagnose tuberculous peritonitis was shown by plotting SROC curve with area under the curve (AUC) = 0.97(95% CI: 0.95 - 0.98) (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Forest plots of pooled sensitivity and specificity of ascitic fluid ADA in the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis.

ADA, adenosine deaminase.

Figure 5. Summary ROC curve with confidence and prediction contours showing discriminatory power of ascitic fluid ADA in the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis.

X-axis, Specificity of ascitic fluid ADA for its discriminating accuracy to diagnose tuberculous peritonitis.

Y-axis, Sensitivity of ascitic fluid ADA for its discriminating accuracy to diagnose tuberculous peritonitis.

ROC, receiver operating characteristic; ADA, adenosine deaminase.

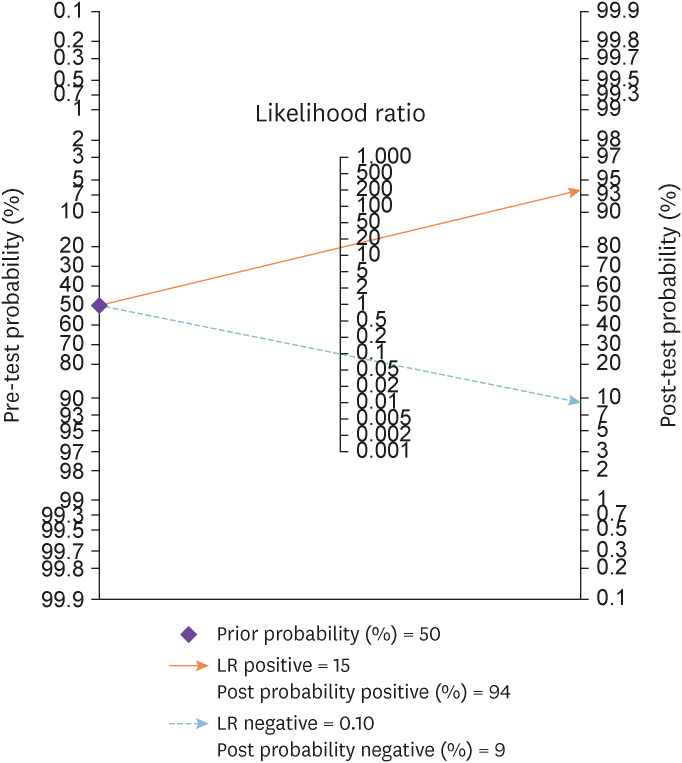

Nomogram analysis (Fagan plot) with pre-test probability of 50% was performed to find out post-test probabilities. The post-test probability of tuberculous peritonitis increased to 94% when ascitic fluid ADA levels were above cut-off value, and decreased to 9% when ascitic fluid ADA was below cut-off value. The PLR was 15.20 (95% CI: 11.70 - 19.80), while the negative likelihood ratio NLR was 0.10 (95% CI: 0.07 – 0.16) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Fagan plot showing pre-test and post-test probability of ascitic fluid ADA in the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis.

5. Publication bias

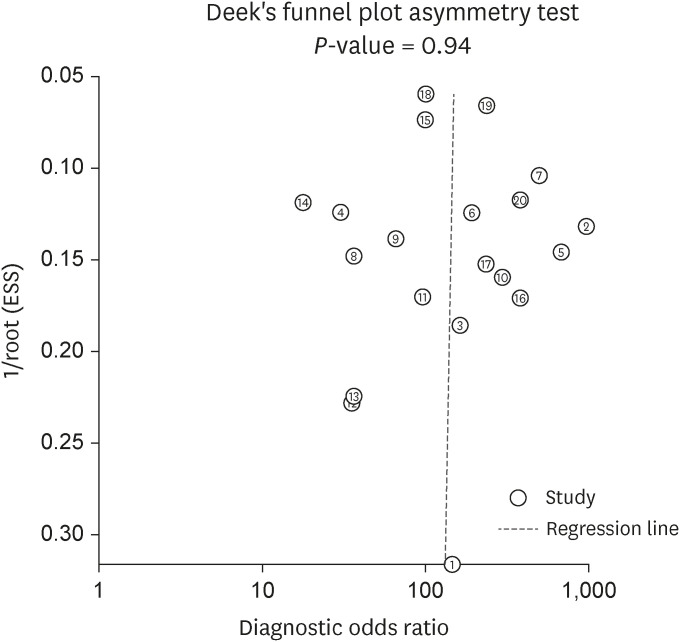

Deek’s funnel plot (Fig. 7) was formulated to check publication bias, which showed a P-value of 0.94 for the slope coefficient. This value is not statistically significant, suggesting symmetry in the data with less probability of publication bias.

Figure 7. Deek’s funnel plot for assessment of risk of publication bias.

6. Meta-regression analysis

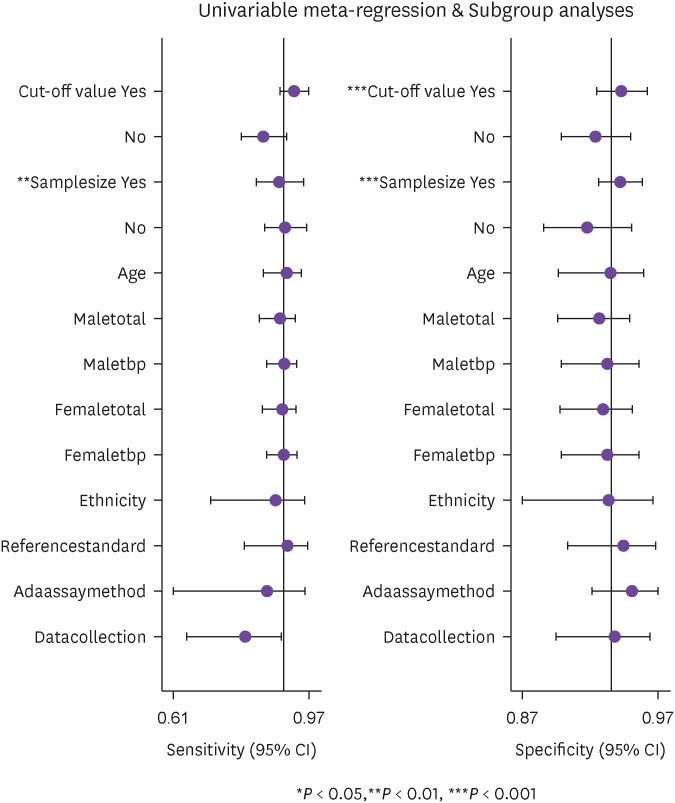

Meta-regression analyses were done to look for the source of possible heterogeneity with following variables: cut-off value of ADA (categorical variable [≤30/>30 U/L]), sample size (categorical variable [≤115/>115]), mean age (continuous variable), gender (categorical variable [male/female]), ethnicity (categorical variable [Asian/Caucasian]), reference standard (categorical variable [with/without radio- imaging]), ADA assay method (categorical variable [Giusti/Non-Giusti]), and data collection (categorical variable [prospective/retrospective]). The results of meta-regression analysis (Fig. 8) showed that the cut-off value for ascitic fluid ADA and sample size could be the possible sources of heterogeneity, which were further analysed by sub-group analysis.

Figure 8. Meta-regression analysis to find possible source of heterogeneity.

7. Sub-group analysis

Sub-group analysis was conducted for cut-off value of ascitic fluid ADA and sample size. The results of sub-group analysis are shown in Table 2. For ascitic fluid ADA, the AUC was 0.95 (95% CI: 0.93 - 0.97) for cut-off ≤30 U/L (10 studies) and 0.98 (95% CI: 0.96 - 0.99) for cut-off >30 U/L (10 studies).

Table 2. Sub group analysis.

| Subgroup | No. of studies | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Heterogeneity (95% CI) | PLR | NLR | DOR | AUC (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | |||||||||

| Cut-off value | ||||||||||

| <30 U/L | 10 | 0.85 (0.79 - 0.90) | 0.93 (0.89 - 0.95) | 48.96 (11.90 - 86.02) | 65.94 (43.10 - 88.79) | 11.7 | 0.16 | 72 | 0.95 (0.93 - 0.97) | |

| >30 U/L | 10 | 0.94 (0.87 - 0.97) | 0.95 (0.93 - 0.96) | 49.73 (13.31 - 86.15) | 16.83 (0.00 - 73.61) | 17.9 | 0.07 | 271 | 0.98 (0.96 - 0.99) | |

| Sample size | ||||||||||

| <115 | 12 | 0.92 (0.83 - 0.96) | 0.93 (0.87 - 0.96) | 57.57 (30.33 - 84.80) | 46.99 (11.54 - 82.45) | 12.6 | 0.09 | 139 | 0.97 (0.95 - 0.98) | |

| >115 | 8 | 0.89 (0.81 - 0.94) | 0.95 (0.93 - 0.96) | 71.44 (50.78 - 92.10) | 27.64 (0.00 - 85.49) | 16.4 | 0.11 | 145 | 0.96 (0.94 - 0.98) | |

CI, confidence interval; PLR, positive likelihood ratio; NLR, negative likelihood ratio; DOR, diagnostic odds ratio; AUC, area under curve.

For sample size ≤115 (12 studies), the AUC was 0.97 (95% CI: 0.95 - 0.98) and for sample size >115 (8 studies) , the AUC was 0.96 (95% CI: 0.94 - 0.98). Further, regarding the cut-ff value of ascitic fluid ADA there was not much difference in the sensitivity and specificity of the two groups (≤30 and >30). Also, there was not much difference in the heterogeneity of sensitivity in between these two cut-off values. However, the heterogeneity of specificity of the cut-off value >30 was lesser (16.83 CI: 0.00 - 73.61) than the ≤30 (65.94 CI: 43.10 - 88.79) group though, with large CI. Regarding the sample size, again there was not much difference in the sensitivity and specificity of the two groups (≤115 and >115). Heterogeneity was significant for the sensitivity in the two groups however, it was lesser in the sample size >115(27.64 CI: 0.00 - 85.49) group, but again with large CI.

8. GRADE analysis

GRADE analysis was also conducted in this meta-analysis and the results are shown in Table 3. For ascitic fluid ADA, the certainty of evidence to diagnose tuberculous peritonitis was found to be very low, both for sensitivity and specificity.

Table 3. GRADE analysis.

| Sensitivity | 0.90 (95% CI: 0.85 - 0.94) | Prevalences | 20% | 30% | 50% | ||||||

| Specificity | 0.94 (95% CI: 0.92 - 0.95) | ||||||||||

| Outcome | No. of studies (No. of patients) | Study design | Factors that may decrease certainty of evidence | Effect per 100 patients tested | Test accuracy CoE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of bias | Indirectness | Inconsistency | Imprecision | Publication bias | Pre-test probability of 20% | Pre-test probability of 30% | Pre-test probability of 50% | ||||

| True positives (patients with tuberculous peritonitis) | 20 studies | Cohort & case- control type studies | Very serious | Serious | Serious | Not serious | None | 18 (17 - 19) | 27 (26 - 28) | 45 (43 - 47) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| False negatives (patients incorrectly classified as not having tuberculous peritonitis) | 2,291 patients | 2 (1 - 3) | 3 (2 - 4) | 5 (3 - 7) | |||||||

| True negatives (patients without tuberculous peritonitis) | 20 studies | Cohort & case- control type studies | Very serious | Serious | Serious | Not serious | None | 75 (74 - 76) | 66 (64 - 66) | 47 (46 - 48) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| False positives (patients incorrectly classified as having tuberculous peritonitis) | 2,291 patients | 5 (4 - 6) | 4 (4 - 6) | 3 (2 - 4) | |||||||

GRADE, grading of recommendations, assessment, development and evaluation; ADA, adenosine deaminase; CI, confidence interval; CoE, certainty of evidence.

Discussion

Tuberculous peritonitis poses great concerns in terms of morbidity and mortality, especially in endemic zones. Timely diagnosis and treatment can prevent the fatal course of the disease. But the current standard methods of diagnosing this disease are either time consuming (culture), less sensitive (culture, AFB smear), invasive (laparoscopy), non-specific (CT scan), and expensive (laparoscopy, CT scan). Assay of lipoarabinomannan in urine is a useful rapid, cheaper and easily available diagnostic test for tuberculosis particularly in children and HIV positive patients. However, it’s sensitivity and specificity vary widely depending upon the patients status belonging to different age group, CD4+count, HIV infection status and testing method [40]. This gives rise to the need of a marker which is quick, less expensive, non-invasive, reliable and has good sensitivity and specificity. ADA has come up as an important tool with all these qualities and many studies have highlighted the role of ADA in diagnosing tuberculous peritonitis with good sensitivity and specificity. Although patients with liver cirrhosis are believed to have low levels of ascitic fluid ADA, when such patients get concomitantly infected with peritoneal tuberculosis, the levels of ascitic fluid ADA get elevated. Thus, ascitic fluid ADA may be useful in diagnosing TBP even in patients with underlying liver cirrhosis [39]. The diagnostic power of ascitic fluid ADA for peritoneal tuberculosis has been assessed via systematic reviews and meta-analyses in literature.

The meta-analysis performed by Riquelme et al in 2006 concluded that ADA proves to be a quick test with good discriminatory power for diagnosing peritoneal TB [12]. But their study had some shortcomings. Only four studies were included in that meta-analysis and it lacked assessment methods like quality assessment and publication bias. After that two more meta-analyses were conducted, one by Shen et al in 2013, and the other by Tao et al in 2014 [13,14]. The first meta- analysis included 16 studies while the second one included 17 studies. Both meta-analyses showed the promising diagnostic role of ADA in ascites with tuberculous etiology [13,14]. Since then, more studies have been conducted and new and robust methods of assessment have been recommended for diagnostic studies. Thus, we carried out an updated meta-analysis including older and newer studies, using latest recommended methods and guidelines for reporting meta- analysis results of diagnostic studies. We also reported results of meta-regression analysis, subgroup analysis and GRADE analysis. A Comparison between the current meta-analysis and the previous meta-analyses is shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Comparison of current meta-analysis with previous meta-analyses.

| Criteria | Riquelme A; 2006 [12] | Shen YC; 2013 [13] | Tao L; 2014 [14] | Present meta-analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of studies | 4 | 16 | 17 | 20 | |

| Number of participants | 264 | 1,574 | 1,797 | 2,291 | |

| Recommended guidelines for prognostic meta-analysis reporting | |||||

| Pooled sensitivity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Pooled specificity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Summary Area under the curve | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Diagnostic odds ratio | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| QUADAS | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ (QUADAS-2) | |

| Publication bias | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Meta-regression | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Sub-group analysis | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | |

| GRADE criteria | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | |

| Analysis used | Pooled sensitivity, Pooled specificity, Summary Area under the curve. | Pooled sensitivity, Pooled specificity, Summary Area under the curve, Diagnostic odds ratio, Publication bias and sub-group analysis. | Pooled sensitivity, Pooled specificity, Summary Area under the curve, Diagnostic odds ratio. Publication bias and meta-regression. | Pooled sensitivity, Pooled specificity, Summary Area under the curve, Diagnostic odds ratio, Publication bias, meta-regression, sub-group analysis and GRADE approach. | |

QUADAS, quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies; GRADE, grading of recommendations, assessment, development and evaluation.

In this study, we have put attention on the diagnostic role of ascitic fluid ADA in diagnosing tuberculous peritonitis. We included 20 studies with 2,291 participants. We performed heterogeneity analysis and it indicated the presence of significant heterogeneity among the studies. So, the random effects model was used for our meta-analysis.

Our meta-analysis included studies with adult patients. However, we included two studies in which the inclusion criteria for age of patients were above 16 years because the mean age in these two studies was above 50 years which corresponds to adult population.

The summary estimates for sensitivity and specificity in our study were 0.90 and 0.94 respectively, and summary AUC was 0.97. The AUC plays an important role in depicting overall accuracy of the diagnostic studies. An AUC value of 1 means that ADA can perfectly differentiate tuberculous from non-tuberculous peritonitis. Our meta-analysis reported AUC to be 0.97, indicating high accuracy level of ascitic fluid ADA for tuberculous peritonitis. In accord with the previous meta-analyses, this meta- analysis also reveals the diagnostic power of ADA in diagnosing tuberculous peritonitis.

Another parameter which indicates diagnostic accuracy in terms of a number value by combining sensitivity and specificity data is the DOR. It is obtained by dividing odds of giving a positive result in patients with TBP to the odds of giving a positive test result in patients without TBP. The higher DOR values correspond to better discriminatory power of the test. In our study, the DOR was found to be 149, indicating important role of ascitic fluid ADA as a marker in discriminating TBP from non-TBP patients.

In this study, we also calculated the likelihood ratios. The PLR was 15.20 indicating that probability of patients with tuberculous peritonitis giving a positive ascitic fluid ADA test result is 15.2 times more than patients not having TBP. The NLR was 0.10 indicating that probability of patients with tuberculous peritonitis giving a negative ascitic fluid ADA test result is 0.10 times as that of a patient, not having TBP.

The methodological quality assessment of studies was done by QUADAS-2 tool.

We also assessed the post-test probability of tuberculous peritonitis by nomogram analysis, setting the pre-test probability at 50%. The post-test probability increased to 94% when ascitic fluid ADA was above cut-off and decreased to 9% when it was below cut-off value. The publication bias was checked by Deek’s funnel plot which indicated symmetry in the data and less probability of publication bias.

In this meta-analysis, we performed meta-regression analyses which indicated sample size and cut-off value for ascitic fluid ADA to be the possible sources of heterogeneity, which were further analysed by sub-group analysis (Table 2). Heterogeneity is significant in the sensitivity and specificity of both the sample size sub-groups (≤115 and >115) except in sample size >115 group where it is less 27.64 (CI: 0.00 - 85.49) in the specificity. However, CI is wide hence precision is less. Similarly, heterogeneity is lesser (16.83 CI: 0.00 - 73.61) for the specificity in the cut-off sub-group >30U/L, but again with wide CI hence, here again precision is less. This heterogeneity may be due to the non-reporting of patient selection method or bias in the patient selection method, lack of blinding in the use of index test and using different cut-off value for ascitic fluid ADA in the included studies.

GRADE approach further analysed that the certainty of evidence to use ascitic fluid ADA for the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis is very low both for sensitivity and specificity due to very serious risk of bias and serious indirectness and inconsistency in the studies.

Our meta-analysis included 20 studies which is a relatively higher number as compared to any previous meta-analysis on the same topic. We included newer studies which were added in the literature after the last meta-analysis. We used newer and recommended methods of meta-analysis like the PRISMA guidelines (which stands for preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies) and QUADAS-2 in this study, which increases the reliability of our study. The results of pooled sensitivity and specificity of ascitic fluid ADA in diagnosing tuberculous peritonitis in our study were highly significant. We also assessed possible sources of heterogeneity in our study and conducted sub-group analyses for them. Further, GRADE approach was used to assess the certainty of evidence to use ascitic fluid ADA for the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis.

We included studies which were reported in English language only, which may have caused language publication bias in selection of studies. The diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis was established by different methods like clinical examination, bacteriological (ascitic fluid culture/AFB smear) examination, biopsy & histopathological examination, and response to treatment of tuberculosis. This may have caused misclassification bias. The meta-analysis included the studies which showed that patients with tuberculous peritonitis had raised ascitic fluid ADA levels, but the study of correlation between the value of ADA and severity of peritonitis was not assessed.

Another limitation was a lack of a definitive predefined cut-off value for ascitic fluid ADA for the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis and different studies used different ADA cut-off values. This lack of definitive cut-off value and differences in sample size of studies introduced heterogeneity in our study. The assessment of the studies was done based on the results of their data and individual patient data analysis was not done which could have otherwise given more homogenous findings.

In conclusion, On the basis of results summarised in this meta-analysis, the determination of ascitic fluid ADA plays a valuable role in diagnosing tuberculous peritonitis and it may be used as a marker of choice for diagnosis of TBP however with very low certainty of evidence. Hence, the diagnostic utility of ascitic fluid ADA should be used in addition to the pre-existing conventional diagnostic methods like clinical, bacteriological and histopathological examination. Moreover, further research is required for determining precise diagnostic accuracy of ascitic fluid ADA for TBP diagnosis by conducting more multi-centric studies with high methodological quality and using a predefined definitive cut-off value of ascitic fluid ADA to obtain homogenous data findings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank RIMS Ranchi for providing guidance and support for this meta-analysis.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest.

- Study concept and design: MKP.

- Data search and retrieval: MM, MKP.

- Analysis and interpretation of data: AK.

- Tables and figures: MM, AK.

- Drafting of manuscript: MM, MKP, PK.

- Supervision: MLP.

- Writing-original draft: MM, MKP, PK.

- Writing-review and editing: MKP, MM, PK, AK, MLP, SM, SS, NC.

References

- 1.Chakaya J, Petersen E, Nantanda R, Mungai BN, Migliori GB, Amanullah F, Lungu P, Ntoumi F, Kumarasamy N, Maeurer M, Zumla A. The WHO Global Tuberculosis 2021 Report - not so good news and turning the tide back to End TB. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;124(Suppl 1):S26–S29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Debi U, Ravisankar V, Prasad KK, Sinha SK, Sharma AK. Abdominal tuberculosis of the gastrointestinal tract: revisited. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:14831–14840. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i40.14831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben Ayed H, Koubaa M, Marrakchi C, Rekik K, Hammami F, Smaoui F, Ben Hmida M, Yaich S, Maaloul I, Damak J, Ben Jema M. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis: Update on the Epidemiology, Risk Factors and Prevention Strategies. Int J Trop Dis. 2018;1:006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rathi P, Gambhire P. Abdominal Tuberculosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2016;64:38–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho JK, Choi YM, Lee SS, Park HK, Cha RR, Kim WS, Kim JJ, Lee JM, Kim HJ, Ha CY, Kim HJ, Kim TH, Jung WT, Lee OJ. Clinical features and outcomes of abdominal tuberculosis in southeastern Korea: 12 years of experience. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:699. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3635-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srivastava U, Almusa O, Tung KW, Heller MT. Tuberculous peritonitis. Radiol Case Rep. 2015;9:971. doi: 10.2484/rcr.v9i3.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma MP, Bhatia V. Abdominal tuberculosis. Indian J Med Res. 2004;120:305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maulahela H, Simadibrata M, Nelwan EJ, Rahadiani N, Renesteen E, Suwarti SWT, Anggraini YW. Recent advances in the diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:89. doi: 10.1186/s12876-022-02171-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abu-Zidan FM, Sheek-Hussein M. Diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis: lessons learned over 30 years: pectoral assay. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14:33. doi: 10.1186/s13017-019-0252-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhargava DK, Gupta M, Nijhawan S, Dasarathy S, Kushwaha AK. Adenosine deaminase (ADA) in peritoneal tuberculosis: diagnostic value in ascitic fluid and serum. Tubercle. 1990;71:121–126. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(90)90007-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Light RW. Update on tuberculous pleural effusion. Respirology. 2010;15:451–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riquelme A, Calvo M, Salech F, Valderrama S, Pattillo A, Arellano M, Arrese M, Soza A, Viviani P, Letelier LM. Value of adenosine deaminase (ADA) in ascitic fluid for the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis: a meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:705–710. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200609000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen YC, Wang T, Chen L, Yang T, Wan C, Hu QJ, Wen FQ. Diagnostic accuracy of adenosine deaminase for tuberculous peritonitis: a meta-analysis. Arch Med Sci. 2013;9:601–607. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2013.36904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tao L, Ning HJ, Nie HM, Guo XY, Qin SY, Jiang HX. Diagnostic value of adenosine deaminase in ascites for tuberculosis ascites: a meta-analysis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;79:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McInnes MDF, Moher D, Thombs BD, McGrath TA, Bossuyt PM, Clifford T, Cohen JF, Deeks JJ, Gatsonis C, Hooft L, Hunt HA, Hyde CJ, Korevaar DA, Leeflang MMG, Macaskill P, Reitsma JB, Rodin R, Rutjes AWS, Salameh JP, Stevens A, Takwoingi Y, Tonelli M, Weeks L, Whiting P, Willis BH and the PRISMA-DTA Group. Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies: the PRISMA-DTA statement. JAMA. 2018;319:388–396. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, Leeflang MM, Sterne JA, Bossuyt PM QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walter SD. Properties of the summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve for diagnostic test data. Stat Med. 2002;21:1237–1256. doi: 10.1002/sim.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deeks JJ, Macaskill P, Irwig L. The performance of tests of publication bias and other sample size effects in systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy was assessed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:882–893. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blake J, Berman P. The use of adenosine deaminase assays in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. S Afr Med J. 1982;62:19–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhargava DK, Gupta M, Nijhawan S, Dasarathy S, Kushwaha AK. Adenosine deaminase (ADA) in peritoneal tuberculosis: diagnostic value in ascitic fluid and serum. Tubercle. 1990;71:121–126. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(90)90007-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brant CQ, Silva MR, Jr, Macedo EP, Vasconcelos C, Tamaki N, Ferraz ML. The value of adenosine deaminase (ADA) determination in the diagnosis of tuberculous ascites. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 1995;37:449–453. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651995000500011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hillebrand DJ, Runyon BA, Yasmineh WG, Rynders GP. Ascitic fluid adenosine deaminase insensitivity in detecting tuberculous peritonitis in the United States. Hepatology. 1996;24:1408–1412. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sathar MA, Simjee AE, Coovadia YM, Soni PN, Moola SA, Insam B, Makumbi F. Ascitic fluid gamma interferon concentrations and adenosine deaminase activity in tuberculous peritonitis. Gut. 1995;36:419–421. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.3.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burgess LJ, Swanepoel CG, Taljaard JJ. The use of adenosine deaminase as a diagnostic tool for peritoneal tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2001;81:243–248. doi: 10.1054/tube.2001.0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma SK, Tahir M, Mohan A, Smith-Rohrberg D, Mishra HK, Pandey RM. Diagnostic accuracy of ascitic fluid IFN-gamma and adenosine deaminase assays in the diagnosis of tuberculous ascites. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26:484–488. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong KD, Lee SI, Moon HY. Comparison between laparoscopy and noninvasive tests for the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis. World J Surg. 2011;35:2369–2375. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1224-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang SJ, Kim JW, Baek JH, Kim SH, Kim BG, Lee KL, Jeong JB, Jung YJ, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Role of ascites adenosine deaminase in differentiating between tuberculous peritonitis and peritoneal carcinomatosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2837–2843. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i22.2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saleh MA, Hammad E, Ramadan MM, Abd El-Rahman A, Enein AF. Use of adenosine deaminase measurements and QuantiFERON in the rapid diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:514–519. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.035121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang HJ, Yang J, Huang YC, Pan HY, Wang H, Ren ZC. Diagnostic feature of tuberculous peritonitis in patients with cirrhosis: a matched case-control study. Exp Ther Med. 2014;7:1028–1032. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ali N, Nath NC, Parvin R, Rahman A, Bhuiyan TM, Rahman M, Mohsin MN. Role of ascitic fluid adenosine deaminase (ADA) and serum CA-125 in the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2014;40:89–91. doi: 10.3329/bmrcb.v40i3.25228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shadia K, Mostofa Kamal SM, Saleh AA, Hossain MN, Gupta RD, Miah RA. Adenosine deaminase assay in different body fluids for the diagnosis of tubercular infection. Am J Biomed Life Sci. 2015;3:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JY, Kim SM, Park SJ, Lee SO, Choi SH, Kim YS, Woo JH, Kim SH. A rapid and non-invasive 2-step algorithm for diagnosing tuberculous peritonitis using a T cell-based assay on peripheral blood and peritoneal fluid mononuclear cells together with peritoneal fluid adenosine deaminase. J Infect. 2015;70:356–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu R, Li J, Tan Y, Shang Y, Li Y, Su B, Shu W, Pang Y, Gao M, Ma L. Multicenter evaluation of the acid-fast bacillus smear, mycobacterial culture, Xpert MTB/RIF assay, and adenosine deaminase for the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis in China. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;90:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumabe A, Hatakeyama S, Kanda N, Yamamoto Y, Matsumura M. Utility of ascitic fluid adenosine deaminase levels in the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis in general medical practice. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2020;2020:5792937. doi: 10.1155/2020/5792937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen HM, Dao MQ, Bui HTT, Luu TC. Using ascitic fluid adenosine deaminase assay in the diagnosis of tuberculous ascites. J Gastroenterol Hepatol Res. 2020;9:3124–3127. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun J, Zhang H, Song Z, Jin L, Yang J, Gu J, Ye D, Yu X, Yang J. The negative impact of increasing age and underlying cirrhosis on the sensitivity of adenosine deaminase in the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis: a cross-sectional study in eastern China. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;110:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dahale AS, Puri AS, Sachdeva S, Agarwal AK, Kumar A, Dalal A, Saxena PD. Reappraisal of the role of ascitic fluid adenosine deaminase for the diagnosis of peritoneal tuberculosis in Cirrhosis. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2021;78:168–176. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2021.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thiruveedhula CS, Chandrakar S, Yasmin T, Sushma BJ. Assessment of adenosine deaminase levels and lypmhocyte counts in tubercular ascitis. Int J Health Sci. 2022;6(Suppl 3):6707–6713. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liao YJ, Wu CY, Lee SW, Lee CL, Yang SS, Chang CS, Lee TY. Adenosine deaminase activity in tuberculous peritonitis among patients with underlying liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5260–5265. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i37.5260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yin X, Ye QQ, Wu KF, Zeng JY, Li NX, Mo JJ, Huang PY, Xie LM, Xie LY, Guo XG. Diagnostic value of Lipoarabinomannan antigen for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis in adults and children with or without HIV infection. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022;36:e24238. doi: 10.1002/jcla.24238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]