Key Points

Question

To what extent is the theoretical risk of opioid addiction associated with patients’ choice of pain medications after Mohs micrographic surgery?

Findings

This prospective discrete choice experiment involving 295 adult survey respondents found that as the theoretical risk of opioid addiction increased, the preference for using only over-the-counter pain medications (OTCs) also increased despite higher levels of pain. A postoperative pain threshold of 6.5 (10-point scale) was required for at least half of the respondents to consider OTCs plus opioids vs only OTCs for pain control.

Meaning

The findings of this prospective choice experiment indicate that a theoretical risk of opioid addiction is associated with patients’ choice of pain medications after Mohs surgery.

Abstract

Importance

Patient preferences for pain medications after Mohs micrographic surgery are important to understand and have not been fully studied.

Objective

To evaluate patient preferences for pain management with only over-the-counter medications (OTCs) or OTCs plus opioids after Mohs micrographic surgery given varying levels of theoretical pain and opioid addiction risk.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective discrete choice experiment was conducted in a single academic medical center from August 2021 to April 2022 among patients undergoing Mohs surgery and their accompanying support persons (≥18 years). A prospective survey was administered to all participants using the Conjointly platform. Data were analyzed from May 2022 to February 2023.

Main outcome and measure

The primary outcome was the pain level at which half of the respondents chose OTCs plus opioids equally to only OTCs for pain management. This pain threshold was determined for varying opioid addiction risk profiles (low, 0%; low-moderate, 2%; moderate-high, 6%; high, 12%) and measured via a discrete choice experiment and linear interpolation of associated parameters (pain levels and risk of addiction).

Results

Of the 295 respondents (mean [SD] age, 64.6 [13.1] years; 174 [59%] were female; race and ethnicity were not considered) who completed the discrete choice experiment, 101 (34%) stated that they would never consider opioids for pain management regardless of the pain level experienced, and 147 (50%) expressed concern regarding possible opioid addiction. Across all scenarios, 224 respondents (76%) preferred only OTCs vs OTCs plus opioids after Mohs surgery for pain control. When the theoretical risk of addiction was low (0%), half of the respondents expressed a preference for OTCs plus opioids given pain levels of 6.5 on a 10-point scale (90% CI, 5.7-7.5). At higher opioid addiction risk profiles (2%, 6%, 12%), an equal preference for OTCs plus opioids and only OTCs was not achieved. In these scenarios, patients favored only OTCs despite experiencing high levels of pain.

Conclusion and relevance

The findings of this prospective discrete choice experiment indicate that the perceived risk of opioid addiction affects the patient’s choice of pain medications after Mohs surgery. It is important to engage patients undergoing Mohs surgery in shared decision-making discussions to determine the optimal pain control plan for each individual. These findings may encourage future research on the risks associated with long-term opioid use after Mohs surgery.

This prospective discrete choice experiment investigated how the perceived risk of opioid addiction may be associated with patient preferences for pain management after Mohs surgery.

Introduction

In the US, approximately 26% of patients who underwent Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) from January 2009 to June 2020 filled an opioid prescription.1 During that time, the percentage of patients who filled an opioid prescription after MMS increased to 39.6% in 2011, and decreased annually thereafter to 11.7% in 2020.1 The duration of opioid prescriptions after MMS was short, ie, averaging 3 to 5 days.1,2 In other medical specialties, short-term opioid use after surgery may be associated with the development of continued, long-term opioid use (odds ratios, 1.28 [cesarean birth] to 5.10 [total knee arthroplasty]).3 In the primary care setting, up to 25% of individuals who fill long-term opioid prescriptions may struggle with opioid addiction.4,5,6 The risk of long-term opioid use after MMS is unknown; therefore, it is important to understand how patients consider the risks of potential long-term opioid use vs other oral pain management options after MMS.

Patient preferences for pain medications have been evaluated in other specialties,7,8 with discordance noted between physician prescribing and patient preferences.9 The purpose of this study was to investigate patient preferences for pain medications after MMS using a discrete choice experiment (DCE). This study evaluated how patients weighed the potential benefit of improved pain control vs the risk of long-term opioid addiction to determine when opioids plus over-the-counter pain medications (OTCs) are preferred to only OTCs for pain management after MMS.

Methods

This prospective discrete choice experiment study was approved by the institutional review board of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Informed consent was obtained digitally from each participant before survey initiation. The study followed the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) best practices for survey research and the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

From August 2021 to April 2022, patients undergoing MMS and their accompanying support person (≥18 years) were recruited to participate in the study and to complete an individual survey. The survey was administered only once to each patient and to their support person in the clinic waiting area, regardless of the timing of the visit (before, on the day of, or after MMS), as other studies have done.10,11

Survey Design

The survey was pilot-tested on multiple stakeholders, and the results were reviewed with the conjoint analysis statistician prior to the final data collection. Stakeholders included Mohs surgeons, office staff, patients, support persons, and the statistician and expert in conjoint analysis. Eligible participants completed an anonymous web-based survey evaluating preferences for only OTCs vs OTCs plus opioids for pain control after MMS. Respondent demographic information and any prior experiences with opioid use and/or oral OTCs for pain control were recorded.

First, to standardize participants’ knowledge of the potential adverse effects of receiving pain medications after surgery (degree of postoperative pain level and addiction risk), a stated choice survey was provided with descriptions of each adverse effect. Participants were asked to rate the importance (ie, important, neutral, not important) of limiting these adverse effects.

Next, participants completed the DCE portion of the survey, which was designed using the online platform, Conjointly12 (Analytics Simplified Pty Ltd, Australia), and administered using a tablet computer device. Discrete choice experiments can be used to elicit patient preferences in health care and to quantify the relative importance that patients allocate to various treatment attributes.13 The DCE evaluated how patients and support persons would weigh the potential benefit of improved pain control vs the risk of opioid addiction to determine the respondents overall preferences for pain control after MMS.

The DCE presented 12 different scenarios to the respondents. In each scenario, the respondent was asked to choose between 2 hypothetical pain management options: “opioids + OTC” or “OTC only” (eFigure in Supplement 1). The number of scenarios provided was set by the Conjointly platform and was determined by the size of the design, alternatives shown per task, and determined sample size target. The DCE scenarios were presented to participants in random order to mitigate any ordering bias.12 Each medication was associated with a different pain control and risk of addiction profile. Survey questions did not specify medication names.

The OTCs plus opioids option had the following risk profiles: pain (0, 3, or 8 on a 10-point scale) and risk of addiction (0%, 2%, 6%, 12%). The only OTCs option had the following risk profiles: pain (level, 0, 3, or 8) and risk of addiction (0%, 2%). Tested values for the pain levels14 and the potential risk of opioid addiction15,16,17,18,19 were determined by literature review. Pain levels and descriptions were derived from the Mankoski pain scale20 and defined on a 10-point scale as 0 (no pain), 3 (pain that is annoying enough to be distracting), and 8 (pain that limits physical activity). Although OTCs do not carry the potential for addiction, for the purposes of this study a 2% risk of addiction in the only OTCs group was used as a hypothetical value to permit adequate statistical overlap and comparison between the medication groups.

Risk of addiction profiles were categorized as low (risk difference [RD], 0% between OTCs plus opioids vs only OTCs), low-moderate (RD, 2%), moderate-high (RD, 6%), and high (RD, 12%). Based on the number of attributes and levels tested, the Conjointly platform estimated a minimum sample size of 250 respondents to achieve a conjoint analysis algorithm with a 90% CI and 5% margin of error.

Study Outcome

The primary outcome was median risk equivalence, defined as the pain level at which 50% of respondents would choose OTCs plus opioids with a given risk of addiction profile. Median risk equivalence was measured via conjoint analysis and linear interpolation between discrete attribute level parameters.

Statistical Analysis

Completed surveys were included in the analysis, and incomplete and/or low-quality (determined by Conjointly by short duration on DCE responses) surveys were excluded. Descriptive statistics described participant demographic information and stated choice survey results. Conjoint analysis, which estimates a hierarchical Bayesian multinomial logit model of choice, was used to determine respondents’ share predictions for attributes and attribute levels. The D-efficiency of this design was 93.9%.

Median risk equivalence was calculated by determining the RD necessary to make OTCs plus opioids equally preferable to only OTCs (ie, a 50% preference level). To determine median risk equivalence, pain levels for OTCs plus opioids were held at 0 pain (10-point scale), whereas for only OTCs, pain levels were varied. Linear interpolation between discrete attribute level parameters determined the pain threshold that OTCs plus opioids was equally preferable to only OTCs. Statistical tests were 2-tailed and P values < .10 were considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed from May 2022 to February 2023 using Conjointly (Analytics Simplified Pty Ltd); RStudio, version 2023.04.0+386 (Posit Software); and Microsoft Excel 365 (Microsoft Corp).

Results

Cohort Characteristics

The survey was initiated by 342 eligible participants and completed by 295 (86%) respondents (mean [SD; range] age, 64.6 [13.1; 22-94] years; 174 [59%] were female and 121 [41%] were male; race and ethnicity were not considered). The Table summarizes additional respondent demographic information and cohort characteristics. Of note was that 59 respondents (20%) were employed by the health care sector.

Table. Survey Respondents’ Demographic Information and Cohort Characteristics .

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Total survey respondents | 295 (100.0) |

| Female sex | 174 (59.0) |

| Male sex | 121 (41.0) |

| Mean (SD) age, y | 64.6 (13.1) |

| Role | |

| Patient | 147 (49.8) |

| Support person | 148 (50.2) |

| Employed as a health care worker | 59 (20.0) |

| Education level | |

| High school diploma/equivalent | 49 (16.6) |

| Trade school/associate degree | 30 (10.2) |

| College degree | 125 (42.4) |

| Graduate/professional degree | 84 (28.5) |

| Prefer not to answer/other | 7 (2.4) |

| Household income, $ | |

| <25 000 | 3 (1.0) |

| 25 000-50 000 | 18 (6.1) |

| 50 000-100 000 | 73 (24.7) |

| 100 000-150 000 | 55 (18.6) |

| >150 000 | 87 (29.5) |

| Prefer not to answer | 59 (20.0) |

| Medications/substance use | |

| Prescription drug for anxiety, panic attacks, and/or depression | 53 (18.0) |

| Tobacco use | 16 (5.4) |

| Alcohol use | 186 (63.1) |

| History of illicit substance use | 96 (32.5) |

| Able to discontinue alcohol/substance use if desired | 281 (95.3) |

Of the 295 respondents, 207 (70.2%) had been previously prescribed an opioid; 101 (34.2%) stated that they would never consider taking an opioid; and 147 (49.8%) were concerned about the risk of opioid addiction. Across all scenarios, 224 respondents (76%) preferred only OTCs to OTCs plus opioids for pain management. Respondents who previously had been prescribed an opioid had an elevated acceptance of OTCs plus opioids for pain management compared with respondents who had no prior opioid prescription. However, across almost all scenarios, respondents who previously had been prescribed opioids preferred only OTCs (eTables 1 and 2 in Supplement 1). There were no differences in preferences between patients and accompanying support persons.

Median Risk Equivalence

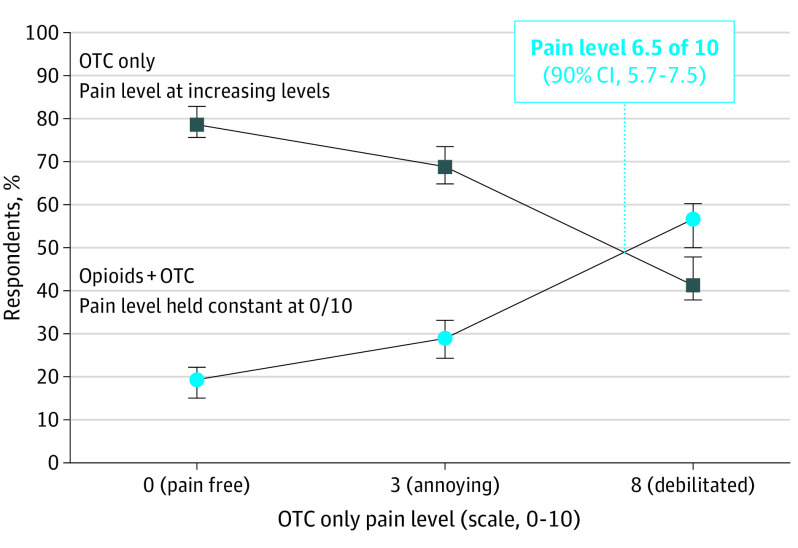

Median risk equivalence was calculated for opioid use with low (0%), low-moderate (2%), moderate-high (6%), and high (12%) risk of addiction profiles. When the theoretical risk of addiction was low (0%), half of respondents expressed a preference for OTCs plus opioids when pain levels reached 6.5 on a 10-point scale (90% CI, 5.7-7.5; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Median Risk Equivalence for a Low (0%) Theoretical Risk of Opioid Addiction.

With a low risk of opioid addiction, respondents equally preferred only OTCs vs OTC plus opioids at a theoretical pain level of 6.5 on a 10-point scale (90% CI, 5.7-7.5). OTCs refers to over-the-counter medications.

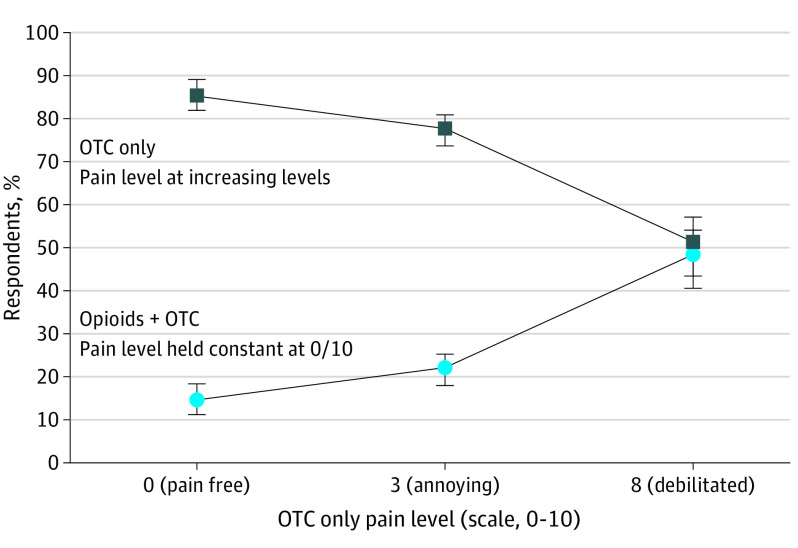

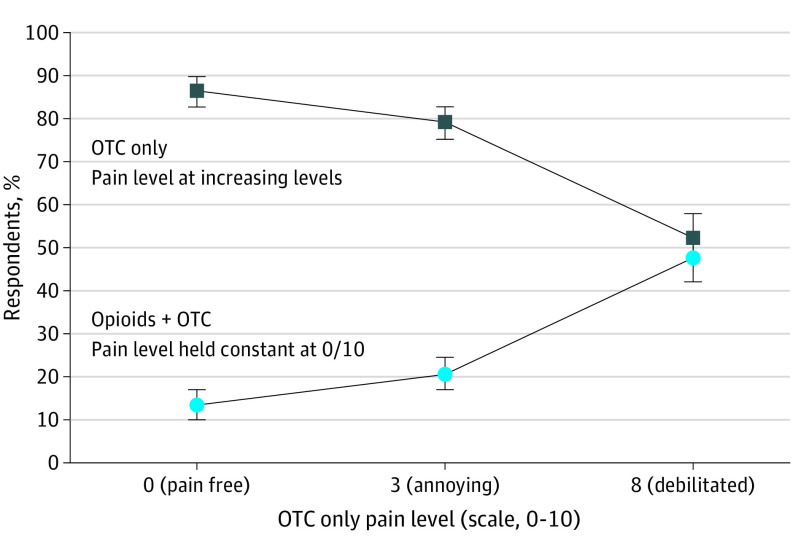

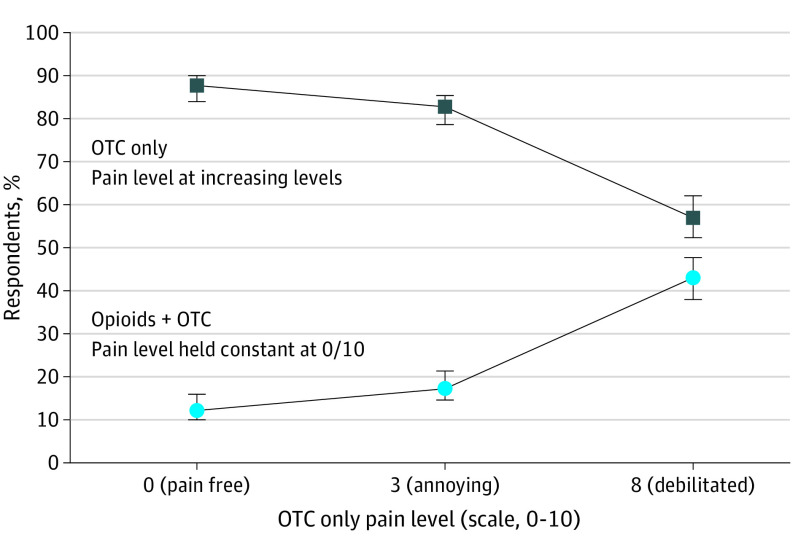

As the risk of opioid addiction increased from low to high, only OTCs were increasingly preferred. For opioids with a low-moderate (2%), moderate-high (6%), or high (12%) risk of addiction profile, a preference for OTCs plus opioids was not achieved (Figures 2, 3, and 4). In these scenarios, respondents preferred only OTCs to OTCs plus opioids despite the high levels of theoretical pain.

Figure 2. Median Risk Equivalence for a Low-to-Moderate (2%) Theoretical Risk of Opioid Addiction.

With a low-moderate risk of opioid addiction, median risk equivalence was not achieved (lines did not intersect). Even with a theoretical pain level of 8 on a 10-point scale, 51% (90% CI, 43.1%-56.7%) of respondents continued to prefer only OTCs over opioids plus OTCs for pain control after Mohs surgery. OTCs refers to over-the-counter medications.

Figure 3. Median Risk Equivalence for a Moderate-to-High (6%) Theoretical Risk of Opioid Addiction.

With a moderate-high risk of opioid addiction, median risk equivalence was not achieved (lines did not intersect). Even with a theoretical pain level of 8 on a 10-point scale, 52% (90% CI, 46.9%-57.5%) of respondents continued to prefer only OTCs over opioids plus OTCs for pain after Mohs surgery. OTCs refers to over-the-counter medications.

Figure 4. Median Risk Equivalence for a High (12%) Theoretical Risk of Opioid Addiction.

With a high risk of opioid addiction, median risk equivalence was not achieved (lines did not intersect). Even with a theoretical pain level of 8 on a 10-point scale, 57% (90% CI, 52.4%-62.1%) of respondents continued to prefer only OTCs over opioids plus OTCs. Additionally, the largest gap was observed between the 2 groups of respondents. OTCs refers to over-the-counter medications.

Discussion

This DCE describes how the theoretical risk of opioid addiction may be associated with patient preferences for pain medications after MMS. As the theoretical risk of opioid addiction increased, patients preferred only OTCs despite high levels of pain. These study findings highlight the need for shared decision-making discussions with patients to determine individualized postoperative pain control regimens.

Our study findings are consistent with literature describing individuals’ concerns of opioid addiction.21 Mohs surgeons prescribe substantially more opioids than do general dermatologists,2 yet there are no data evaluating the long-term risks of opioid use after MMS. In other specialties, minor surgical procedures have been associated with an increased incidence of long-term opioid use,3,17 and a study estimated a 3% incidence of prolonged opioid use after elective surgery.15 The data in our study suggested that perceived addiction risk was associated with patient preferences for postoperative pain medications. Further research is needed to characterize the risk of opioid addiction after MMS.

Across all scenarios, 224 respondents (76%) preferred only OTCs vs OTCs plus opioids for pain management. Postoperative pain after MMS can be controlled with nonnarcotic medications,22 and postoperative acetaminophen plus ibuprofen have been demonstrated to be superior to acetaminophen plus codeine and acetaminophen alone in controlling pain after MMS.23 If opioids are prescribed in cutaneous surgery, clinicians should prescribe short-acting agents with limited prescription durations.24 Understanding patient preferences can also guide pain control regimens.

More than one-third (34.2%) of respondents would not consider opioid use after MMS, and nearly half (49.8%) were concerned about the risk of opioid addiction. Patient factors—age, education, fear of addiction, and prior experiences—may be associated with these perspectives.21 Physicians may also affect patient preferences depending how they review adverse effects and the potential risk of opioid addiction.25 Engaging in discussions with patients about the pain control options, their past experiences with pain medications, and surgical expectations may help physicians to improve the quality of the care they provide and to empower patients to make informed and personalized decisions.26

Limitations

The limitations of this study include its single-center design at a tertiary academic medical center in an urban location. Our study population included a high percentage of health care workers and individuals with relatively high education and household income. Therefore, the findings of this study may not be generalizable to the larger population. Although DCEs have been used in MMS,10,11 DCEs do not measure actual behavior and may not include all possible risks and benefits that may be important to participants. For example, respondents who are in active pain may respond differently to the DCE’s hypothetical scenarios. Despite this, DCEs provide important data regarding implicit decision weights,27 which can inform future discussions with patients.

Conclusion

This prospective discrete choice experiment study evaluating patient preferences for pain control after MMS indicates that a theoretical risk of opioid addiction may affect a patient’s choice of pain medications. These findings may spur research investigating the risk of long-term opioid use after MMS and provide a framework for Mohs surgeons to engage in shared decision-making discussions with patients moving forward.

eTable 1. Average preference levels for opioids plus over-the-counter pain management in respondents who were previously prescribed opioids versus respondents with no prior opioid prescription

eTable 2. Average preference levels for over-the-counter only pain management in respondents who were previously prescribed opioids versus respondents with no prior opioid prescription

eFigure. Sample format of a discrete choice experiment question

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Veerabagu SA, Cheng B, Wang S, et al. Rates of opioid prescriptions obtained after Mohs surgery: a claims database analysis from 2009 to 2020. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(11):1299-1305. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feng H, Kakpovbia E, Petriceks AP, Feng PW, Geronemus RG. Characteristics of opioid prescriptions by Mohs surgeons in the Medicare population. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46(3):335-340. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000002038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1286-1293. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boscarino JA, Rukstalis M, Hoffman SN, et al. Risk factors for drug dependence among out-patients on opioid therapy in a large US health-care system. Addiction. 2010;105(10):1776-1782. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03052.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleming MF, Balousek SL, Klessig CL, Mundt MP, Brown DD. Substance use disorders in a primary care sample receiving daily opioid therapy. J Pain. 2007;8(7):573-582. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.02.432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Prescription Opioids. US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/basics/prescribed.html

- 7.Turk D, Boeri M, Abraham L, et al. Patient preferences for osteoarthritis pain and chronic low back pain treatments in the United States: a discrete-choice experiment. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2020;28(9):1202-1213. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2020.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poulos C, Soliman AM, Renz CL, Posner J, Agarwal SK. Patient preferences for endometriosis pain treatments in the United States. Value Health. 2019;22(6):728-738. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison M, Milbers K, Hudson M, Bansback N. Do patients and health care providers have discordant preferences about which aspects of treatments matter most? evidence from a systematic review of discrete choice experiments. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e014719. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aizman L, Barbieri JS, Feit EM, et al. Preferences for prophylactic oral antibiotic use in dermatologic surgery: a multicenter discrete choice experiment. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47(9):1214-1219. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000003113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neal DE, Golda N, Patel V, Black W, Lee MP, Etzkorn JR. Local anesthesia is preferred for skin cancer surgery-results of a choice-based conjoint analysis experiment. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46(8):1106-1108. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conjointly. Survey platform with easy-to-use advanced tools and expert support. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://conjointly.com/

- 13.Lancaster KJ. A new approach to consumer theory. J Polit Econ. 1966;74(2):132-157. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Firoz BF, Goldberg LH, Arnon O, Mamelak AJ. An analysis of pain and analgesia after Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(1):79-86. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clarke H, Soneji N, Ko DT, Yun L, Wijeysundera DN. Rates and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after major surgery: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g1251. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brat GA, Agniel D, Beam A, et al. Postsurgical prescriptions for opioid naive patients and association with overdose and misuse: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018;360:j5790. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(6):e170504. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, Crane E, Lee J, Jones CM. Prescription opioid use, misuse, and use disorders in US adults: 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(5):293-301. doi: 10.7326/M17-0865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heitz C, Morgenstern J, Bond C, Milne WK. Hot off the press: SGEM #264-hooked on a feeling? opioid use and misuse three months after emergency department visit for acute pain. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(3):240-242. doi: 10.1111/acem.13856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whelan E. Putting pain to paper: endometriosis and the documentation of suffering. Health. 2003;7(4):463-482. doi: 10.1177/13634593030074005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Sola H, Salazar A, Dueñas M, Failde I. Opioids in the treatment of pain. beliefs, knowledge, and attitudes of the general Spanish population. identification of subgroups through cluster analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(4):1095-1104. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.12.474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saco M, Golda N. Optimal timing of postoperative pharmacologic pain control in Mohs micrographic surgery: a prospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(2):495-497. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sniezek PJ, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. A randomized controlled trial comparing acetaminophen, acetaminophen and ibuprofen, and acetaminophen and codeine for postoperative pain relief after Mohs surgery and cutaneous reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37(7):1007-1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02022.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez JJ, Warner NS, Arpey CJ, et al. Opioid prescribing for acute postoperative pain after cutaneous surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(3):743-748. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gong J, Zhang Y, Feng J, Huang Y, Wei Y, Zhang W. Influence of framing on medical decision making. EXCLI J. 2013;12:20-29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oben P. Understanding the patient experience: a conceptual framework. J Patient Exp. 2020;7(6):906-910. doi: 10.1177/2374373520951672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bewtra M, Kilambi V, Fairchild AO, Siegel CA, Lewis JD, Johnson FR. Patient preferences for surgical versus medical therapy for ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(1):103-114. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000437498.14804.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Average preference levels for opioids plus over-the-counter pain management in respondents who were previously prescribed opioids versus respondents with no prior opioid prescription

eTable 2. Average preference levels for over-the-counter only pain management in respondents who were previously prescribed opioids versus respondents with no prior opioid prescription

eFigure. Sample format of a discrete choice experiment question

Data Sharing Statement