Abstract

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) has received much attention as a potential pulmonary hypertension (PH) treatment target because inhibition of HIF reduces the severity of established PH in rodent models. However, the limitations of small-animal models of PH in predicting the therapeutic effects of pharmacologic interventions in humans PH are well known. Therefore, we sought to interrogate the role of HIFs in driving the activated phenotype of PH cells from human and bovine vessels. We first established that pulmonary arteries (PAs) from human and bovine PH lungs exhibit markedly increased expression of direct HIF target genes (CA9, GLUT1, and NDRG1), as well as cytokines/chemokines (CCL2, CSF2, CXCL12, and IL6), growth factors (FGF1, FGF2, PDGFb, and TGFA), and apoptosis-resistance genes (BCL2, BCL2L1, and BIRC5). The expression of the genes found in the intact PAs was determined in endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and fibroblasts cultured from the PAs. The data showed that human and bovine pulmonary vascular fibroblasts from patients or animals with PH (termed PH-Fibs) were the cell type that exhibited the highest level and the most significant increases in the expression of cytokines/chemokines and growth factors. In addition, we found that human, but not bovine, PH-Fibs exhibit consistent misregulation of HIFα protein stability, reduced HIF1α protein hydroxylation, and increased expression of HIF target genes even in cells grown under normoxic conditions. However, whereas HIF inhibition reduced the expression of direct HIF target genes, it had no impact on other “persistently activated” genes. Thus, our study indicated that HIF inhibition alone is not sufficient to reverse the persistently activated phenotype of human and bovine PH-Fibs.

Keywords: HIF inhibition, pulmonary arterial hypertension, hypoxia-induced PH, Fibs, persistently activated phenotype

Clinical Relevance

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) has received much attention as a potential pulmonary hypertension (PH) treatment target because inhibition of HIF reduces the severity of established PH in rodent models. However, our study using cells from PH patients and animals indicated that HIF inhibition alone is not sufficient to reverse the "persistently activated" phenotype of human and bovine PH-fibroblasts.

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is characterized by a progressive increase in pulmonary vascular resistance resulting in right ventricular dysfunction and, ultimately, failure. Vasoconstriction and vascular remodeling are the major contributors to increased pulmonary vascular resistance. Existing therapeutic agents, broadly termed vasodilators, target pulmonary vasoconstriction and improve functional status and quality of life in some patients with PH; however, their use has a limited impact on vascular remodeling and the development of right ventricular failure. These limitations underscore the need to better understand the cellular and molecular underpinnings of PH to facilitate new therapeutic approaches.

There is a significant interest in targeting pathways that contribute to chronic vascular remodeling, including hypoxia, inflammation, dysregulated transcription, and genetic and epigenetic factors, which control several cellular processes, including proliferation, apoptosis, and synthesis of extracellular matrix (1, 2). One transcription factor that has received much attention related to potential PH treatment is hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) (3, 4). Studies have shown that HIF inhibition can partially reverse established PH in animal models of PH, which are induced directly by hypoxia/HIF activation (5, 6) or by Sugen/hypoxia or monocrotaline (5, 7). In addition, numerous studies have also shown that HIF activation is a significant component of the microenvironment in established human PH/pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), as evidenced by increased expression of HIFα protein and/or HIF target genes in lung vessels (8, 9). More importantly, multiple studies have reported that HIFα proteins are persistently detected in pulmonary vascular cells isolated from human PH vessels obtained from the lungs of patients with idiopathic PAH even when these cells are cultured under normoxic conditions (5, 8, 10–12). This dysregulation of HIFα protein stability in PH cells that exhibit persistently altered gene expression and cellular phenotype (13) supports a possible role of HIF protein in “locking” PH vascular cells into a diseased phenotype manifesting aberrant gene expression.

However, despite the data supporting HIF’s potential as a treatment target as described above, it is possible that HIF inhibition may not have dramatic effects on established chronic PH. It is important to note that, in cancer, prior observations by us and others revealed that HIF1 and HIF2 activities were dispensable for the expression of prototypic HIF target genes in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma cells (14–16) even though HIF1 and HIF2 are constitutively activated (because of mutation of VHL, the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor).

Based on this intriguing and conflicting information and because of the well-known limitations of small-animal models of PH in predicting the therapeutic effects of pharmacologic interventions in human PH, we employed an alternative system by examining the role of HIF in maintaining the activated phenotype of pulmonary vascular wall cells derived from pulmonary arteries (PAs) of patients with PAH/PH or calves with severe hypoxia-induced PH. We first sought to determine the gene-expression changes in pulmonary vessels of human patients with PH/PAH (normal pulmonary vessels as control), focusing on HIFs, HIF target genes, and other genes characteristic of vascular remodeling, including those related to inflammation, proliferation, and apoptosis. The purpose is to establish the gene-expression changes found in vivo. Then, the same set of genes was evaluated in resident cells derived from the human pulmonary vascular wall, including endothelial cells (ECs), smooth muscle cells (SMC), and adventitia fibroblasts (Fibs). Because, among the three structural cell populations in the pulmonary vessel wall, pulmonary vascular Fibs from patients with PH (PH-Fibs) were the cell type that consistently exhibited the highest level and the greatest increases in the expression of cytokines/chemokines and growth factors (GFs) in conjunction with HIF activation even under normoxic conditions, we focused our attention on the PH-Fibs in experiments designed to directly examine the role of HIFs in maintaining abnormal gene expression. We also performed an almost identical set of experiments in the calf model of severe hypoxia-induced PH. PH in this model, unlike in the human PAH condition, can be attributed directly to hypoxic exposure and, therefore, likely involves direct HIF activation. Further, unlike the human vessels and cells we have studied, which are from a late stage of disease development, the calf model represents an early stage of the disease and is well known to be characterized by significant changes in proliferation and inflammation. This allows us to compare and contrast the role of HIFs in maintaining the cell phenotype at different stages of disease development. We used molecular and pharmacologic inhibition strategies to interrogate the role of HIF in controlling PH-Fib cell phenotype in both models. Collectively, our data do not support a significant role for HIF activity in controlling the phenotype of PH-Fibs derived from the hypertensive pulmonary vascular wall of humans or calves.

Methods

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. GraphPad Prism 9.3.1 (GraphPad Software) was used to determine statistical significance. We first used a Shapiro-Wilk test to assess data distribution and found that data with two groups and data with more than two groups all exhibited normal (i.e., Gaussian) distribution. Because our data were generated from different cell populations, rather than from the same cell tested multiple times, we used unpaired analysis. We used a two-tailed t test for statistical analysis of data with two groups. For data with more than two groups, we used ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. The differences between specific groups, but not all groups, are presented. For experiments concerning gene-expression differences between PH PAs, Fibs, SMCs, or ECs versus respective controls in Figures 1 and 2 (human), Figures 4 and 5 (bovine), and the associated data in Figures E1 (human) and E8 (bovine) in the data supplement, the same samples were used for measurements of a total of 16 genes, including direct HIF target genes (CA9, GLUT1, and NDRG1), cytokines/chemokines (CCL2, CSF2, CXCL12, and IL6), GFs (FGF1, FGF2, PDGFb, and TGFA), apoptosis-resistance genes (BCL2, BCL2L1, and BIRC5), and proliferation markers (MKI67 and PCNA). For experiments concerning the effect of HIF inhibition on the expression of genes in PH-Fibs in Figures 3 (human) and 6 (bovine) and the associated data presented in Figures E6 and E7 (human) and E11 and E12 (bovine), besides the aforementioned 16 genes, we also performed analysis of additional HIF target genes (HK2, LDHA, PDK1, ADM, EGLN3, and VEGF). There are various ways to correct for the increased possibility of false-positive findings when the same samples are used to test differences in multiple genes, which range from very conservative methods to more lenient ones, but they all run the risk of missing important genes when the number of hypotheses tested is relatively small. Other methods and materials are described in the data supplement.

Figure 1.

Pulmonary arteries (PAs) from human PA hypertension (PAH) patient lungs exhibit increased mRNA levels of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) targets, cytokines/chemokines, growth factors (GFs), and apoptosis-resistance genes compared with the PAs from control (CO) human subjects. (A) Immunostaining of HIF1 (CA9) and HIF2 (PHD3) target genes in human PAH lungs. Expression of CA9 (a and b) and PHD3 (c and d) in serial sections of two idiopathic PAH (IPAH) PAs (a and c, b and d). Note the expression of CA9 in the intima (arrowheads) of obliterative lesions (a) and adventitia inflammatory cell clusters (arrows, a and b) and adventitia connective tissues (a and b). PHD3 expression predominated in the adventitia (c, arrows) while being expressed focally in the intima of PAs with marked media thickening (d, arrowheads). Scale bars, 200 μm; representative of n = 4 lungs per group. (B–F) qRT-PCR analysis of HIF targets (B), cytokines and chemokines (C), GFs (D), apoptosis-resistance genes (E), and proliferation markers (F) in PAs from human CO (n = 5) and PAH (n = 5) subjects. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.03, and ***P < 0.01. (G) Immunostaining of selected qRT-PCR targets CSF2 (a and c) or CXCL12 (b and d) in CO (a and b) and IPAH PAs (c and d, arrows). CSF2 is expressed along the intima (a) in the normal PA (arrow, a) while being expressed in the adventitia (arrow, b) in IPAH PA with media hypertrophy. CXCL12 is expressed in the intima and adventitia of a normal PA (arrow, b) and the adventitia (arrows, d) of an obliterated PA (arrowhead, d) in IPAH. Scale bars: a, c, and d, 100 μm; b, 200 μm; representative of n = 4 lungs per group.

Figure 2.

Among the vascular cells (fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells from patients or animals with pulmonary hypertension [PH]; PH-Fibs, PH-ECs, and PH-SMCs, respectively) established from PAs of human PAH lungs, human PH-Fib is the cell type that exhibits the most increase and produces the highest levels of cytokines/chemokines and GFs that are overexpressed in human PAH PAs. (A and B) qRT-PCR analysis of cytokines and chemokines (A) and GFs (B) in human CO (n = 4–5) and PH (n = 4–5) Fibs, SMCs, and ECs cultured under normoxia. *Statistical differences between CO and PH cells within the same cell type. +Difference between CO-SMCs or CO-ECs versus CO-Fibs. +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.03, and +++P < 0.01. ‡Difference between PH-SMCs or PH-ECs versus PH-Fibs. ‡P < 0.05, ‡‡P < 0.03, and ‡‡‡P < 0.01. The number in each panel indicates the average expression of the gene in CO-Fib (at 1), PH-Fib, CO-SMCs, PH-SMCs, CO-ECs, and PH-ECs. (C–E) qRT-PCR analysis of hypoxia-inducible factor targets (C), apoptosis-resistance genes (D), and proliferation markers (E) in human CO- and PH-Fibs cultured under normoxia. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.03, and ***P < 0.01.

Figure 4.

Distal (dPAs) from hypoxia-induced PH calves exhibit increased mRNA levels of HIF targets, cytokines/chemokines, GFs, antiapoptosis genes, and proliferation markers compared with distal PAs from normal CO calves. (A–E) qRT-PCR analysis of HIF targets (A), cytokines/chemokines (B), GFs (C), apoptosis-resistance genes (D), and proliferation markers (E) in dPAs from normal CO calves (n = 5) or dPAs from hypoxic calves (n = 5). *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.01.

Figure 5.

Among the bovine vascular cells (Fibs, ECs, and SMCs) established from dPAs of calves with PH, Fibs from animals with PH is the cell type that exhibits the most increase and produces the highest mRNA levels of most cytokines, chemokines, and GFs that are overexpressed in bovine PH dPAs. (A and B) qRT-PCR analysis of cytokines and chemokines (A) and GFs (B) in bovine CO (n = 4–6) and PH (n = 4–6) Fibs, SMCs, and ECs cultured under normoxia. *Statistical differences between CO and PH cells within the same cell type. +Difference between CO-SMCs or CO-ECs versus CO-Fibs. ++P < 0.03. ‡Difference between PH-SMCs or PH-ECs versus PH-Fibs. ‡P < 0.05, ‡‡P < 0.03, and ‡‡‡P < 0.01. (C–E) qRT-PCR analysis of hypoxia-inducible factor targets (C), apoptosis-resistance genes (D), and proliferation markers (E) in bovine CO-Fibs (n = 6) and PH-Fibs (n = 6) cultured under normoxia. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.03, and ***P < 0.01.

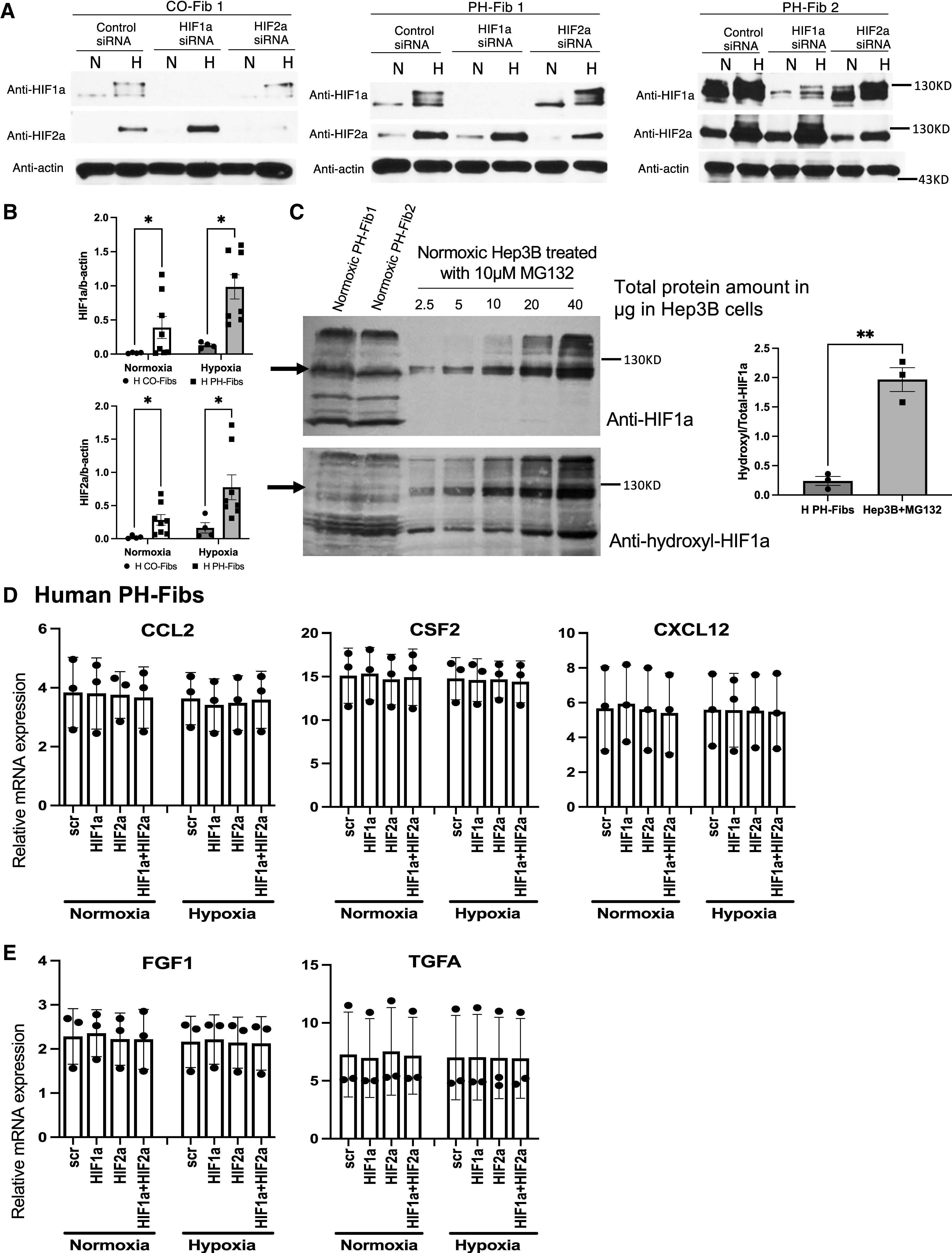

Figure 3.

Fibs from human patients with PH exhibit increased activation of HIF pathways compared with human CO-Fibs under normoxia or hypoxia. However, hypoxia and HIFs are not involved in maintaining high levels of cytokine/chemokines and GFs in human PH-Fibs. (A) Western blot (WB) analysis of HIF1α and HIF2α protein in human CO- and PH-Fibs cultured under “N” or “H” and targeted with CO or HIF1A- or HIF2A-specific siRNA. (B) Quantification of HIF1α/actin and HIF2α/actin ratio in human CO- and PH-Fibs under normoxia or hypoxia. (C) Left: WB analysis of total (anti-HIF1α) and proline-564 hydroxylated (anti-hydroxyl) HIF1α protein in 30 µg protein from two normoxic human PH-Fibs or in 2.5–40 µg protein from Hep3B cells, cultured under normoxia and in the presence of proteasome inhibitor MG132. Right: The ratio of hydroxyl-HIF1α versus total HIF1α protein in human PH-Fibs and Hep3B cells cultured under normoxia. (D and E) qRT-PCR analysis of cytokines/chemokines (D) and GFs (E) in human PH-Fibs (n = 3) transfected with scramble, HIF1A, HIF2A, or both siRNAs, cultured under normoxia or hypoxia. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.03. H = hypoxia; N = normoxia.

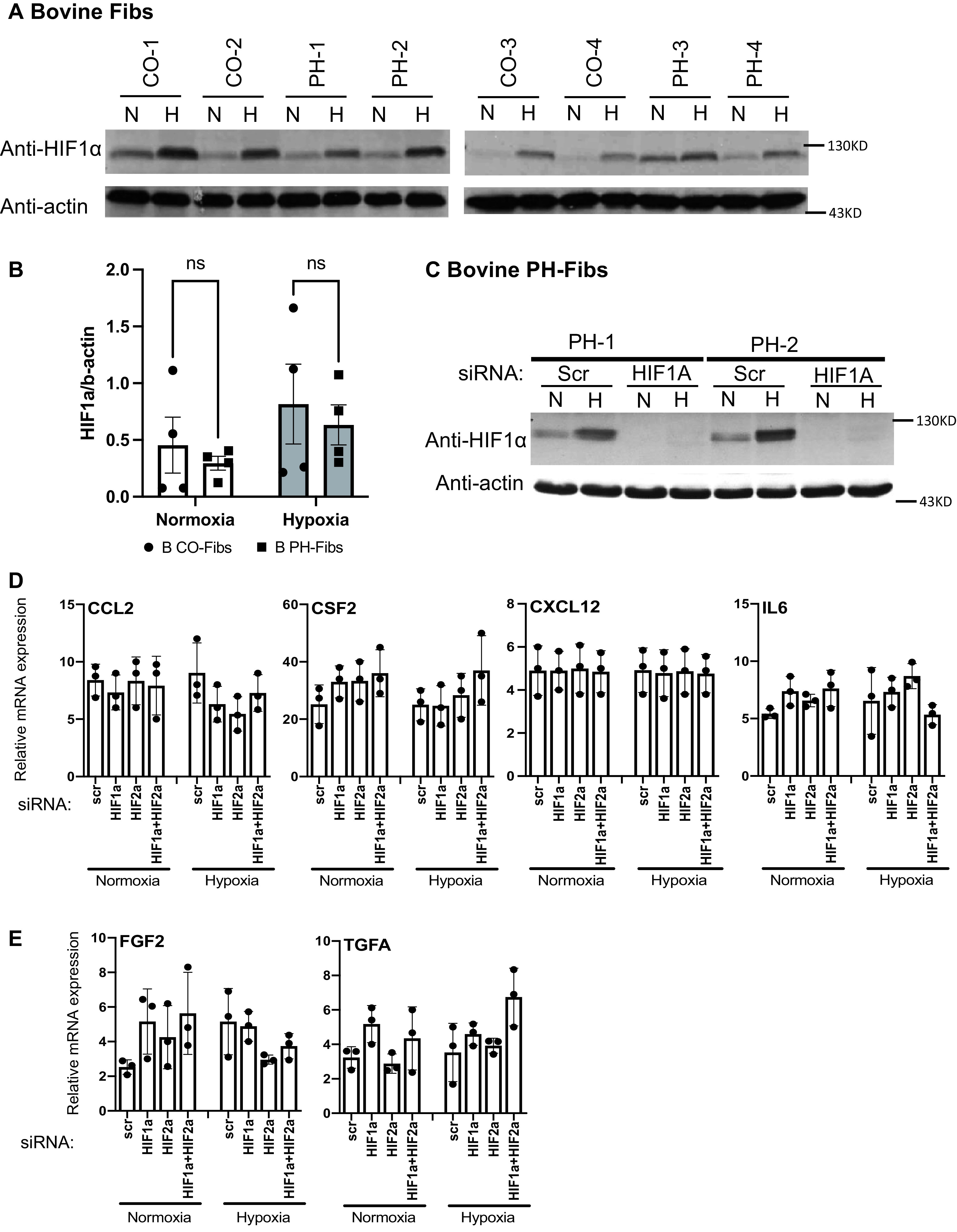

Figure 6.

Fibs from animals with PH did not exhibit increased activation of HIF pathways compared with CO Fibs under normoxia or hypoxia; in addition, hypoxia and HIFs are not involved in maintaining high mRNA levels of cytokines/chemokines and GFs in bovine PH-Fibs. (A) WB analysis of HIF1α protein in bovine CO-Fibs and PH-Fibs cultured under “N” or “H”. (B) Quantification of HIF1α/actin ratio in bovine CO- and PH-Fibs under normoxia or hypoxia. (C) WB analysis of HIF1α protein in bovine PH-Fibs transfected with scramble or HIF1A siRNA, cultured under “N” or “H”. (D and E) qRT-PCR analysis of cytokines/chemokines (D) and GFs (E) in bovine PH-Fibs transfected with scramble, HIF1A or HIF2A siRNA, or both, cultured under normoxia or hypoxia. Two-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. ns = not significant.

Results

Human PH Pulmonary Vessels Exhibit Increased Expression of HIF Targets, Cytokines/Chemokines, GFs, and Antiapoptosis Genes

We first sought to determine the expression of HIF proteins in PAs. Because of the lack of specificity of the available antibodies, especially for HIF2α protein, we focused on confirming the expression of HIF target genes in idiopathic PAH lungs (8, 9). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated that HIF1 (carbonic anhydrase 9/CA9) and HIF2 (prolyl hydroxylase domain 3/PHD3) target genes were highly expressed in the human PAH vessels (Figure 1A). Consistent with the reported increase (3, 4, 17–24), PAs from patients with PAH exhibited increased mRNA levels of HIF targets (CA9, glucose transporter 1/GLUT1, and N-Myc downstream-regulated 1/NDRG1; Figure 1B), cytokines/chemokines (C-C motif chemokine ligand 2/CCL2, colony-stimulating factor 2/CSF2, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12/CXCL12, and interleukin 6/IL6; Figure 1C), GFs (fibroblast growth factor 2/FGF2, platelet-derived growth factor subunit B/PDGFB, and transforming growth factor α/TGFα; Figure 1D), and apoptosis-resistance genes (B-cell lymphoma 2/BCL2, BCL2-like 1/BCL2L1, and baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 5/BIRC5; Figure 1E). Notably, the proliferation markers (marker of proliferation Ki-67/MKI67 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen/PCNA) (Figure 1F) were not increased in the PAs of patients with PAH. Immunostaining confirmed the increased expression of CSF2 and CXCL12, the selected targets, in human PAH PAs (Figure 1G).

Human PH-Fibs Exhibit Greater Expression of Cytokines/Chemokines and Growth Factors than Human PH-SMCs and PH-ECs

PAs comprise multiple cell types, including ECs, SMCs, and Fibs, the vascular wall cell types in which HIF1 or/and HIF2 activation leads to PH initiation (3, 4). Thus, we evaluated gene expression in pulmonary ECs, SMCs, and Fibs established from PAs of control donors and patients with PAH. We first addressed the expression of HIF target genes. Compared with their respective controls, the levels of HIF target genes CA9 and GLUT1 (but not NDRG1) were increased in human PH-Fibs (Figure 2C); only CA9 was increased in human PH-ECs (see Figure E1D), but no increases in the examined HIF target genes were observed in human PH-SMCs. Because the inflammatory mediators and GFs are extracellular and diffusible and have well-documented roles in PH disease (18–24), we performed a comparative analysis of these factors in all three cell types. Interestingly, compared with their respective controls, human PH-Fibs were found to be the cell type that exhibited increased mRNA levels of most of these factors, whereas PH-SMCs and PH-ECs showed no increases for most of these factors (Figures 2A and 2B). Further, human PH-Fibs expressed the highest mRNA levels of cytokines/chemokines (CCL2, CSF2, CXCL12, and IL6) (Figure 2A) and GFs (FGF1 and TGFA) (Figure 2B) compared with PH-SMCs and PH-ECs. mRNA levels of these factors in human PH-Fibs and control Fibs (CO-Fibs) were largely consistent with protein levels as assessed by cytokine/GF protein arrays (see Figure E2). For example, similar to increased mRNA levels, protein levels of CCL2/MCP1, CSF2/GMCSF, and CXCL12/SDF1 were also increased in human PH-Fibs (see Figures E2A and E2C). In addition, similar to unchanged (FGF2) or low (PDGFB) levels of mRNAs, FGF2 or PDGFB protein levels exhibited no difference or no detection, respectively, between PH-Fibs and CO-Fibs (see Figures E2A and E2C). The protein-array analysis also uncovered increases in additional proteins, including C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 5/CXCL5, FGF7, Growth-regulated α protein/GROa, Hepatocyte Growth Factor/HGF, interleukin-8/IL8, and PDGFA (see Figure E2C). We also examined the expression of other genes in human PH and control vascular wall cells. The levels of antiapoptotic genes BCL2, BCL2L1, and BIRC5 were increased in human PH-Fibs (Figure 2D) and human PH-SMCs (see Figure E1B), but not in human PH-ECs (see Figure E1E), compared with their corresponding control cells. Further, the levels of proliferation markers MKI67 and PCNA appeared to be slightly increased (not statistically significant) in PH-Fibs (Figure 2E) and in PH-SMCs (see Figure E1C) but not in PH-ECs (see Figure E1F). Because of higher levels of cytokines/chemokines and GFs in PH-Fibs and the reported involvement of inflammation mediators and GFs in PH, the following experiments will focus on PH-Fibs.

HIFα Protein Expression in Human CO- and PH-Fibs

After establishing the phenotype of human PH-Fibs described above, we sought to probe in depth the contribution of HIF activity in maintaining this phenotype. We first examined the levels of HIFα protein in human PH-Fibs under normoxic and hypoxic cell culture conditions because PH pulmonary vessels are likely exposed to hypoxic conditions in vivo (see consistently increased mRNA levels of HIF targets in human PH-distal PAs; Figures 1A and 1B). Under normoxic conditions, HIF1α and HIF2α proteins were detected in CO-Fibs and PH-Fibs (Figures 3A and E3A). Exposure to hypoxia increased the levels of HIF1α and HIF2α proteins in human CO- and PH-Fibs (Figures 3A and E3A). Further, based on data from Figures 3A and E3A, PH-Fibs showed increased HIF1α/b-actin and HIF2α/b-actin ratios compared with CO-Fibs under normoxic and hypoxic conditions (Figure 3B). Increased HIFα protein in PH-Fibs was further supported by increased levels of HIF1α and HIF2α protein in PH-Fibs compared with CO-Fibs when the samples from CO- and PH-Fibs were on the same gel/membrane (see Figure E3B). In addition, the specificity of the antibody to human HIF1α or HIF2α in the Western blots (WBs) of human Fibs was confirmed, as the intensities of these bands were completely abolished (HIF1α) or significantly reduced (HIF2α) in CO- and PH-Fibs targeted with HIF1A or HIF2A siRNA compared with scrambled sequences (Figures 3A and E3A).

HIFα protein is rapidly degraded in most normal cells under normoxic conditions. This process is initiated by hydroxylation of HIFα protein at two specific proline residues (human HIF1α: Pro402 and 564) within the oxygen-dependent degradation domain by PHD1–3 (prolyl hydroxylase domain-containing proteins 1–3), which use oxygen (O2), iron (Fe2+), α-ketoglutarate, and ascorbic acid as cosubstrates. Hydroxylated HIFα proteins are recognized by von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor/VHL-E3 ubiquitin complexes and degraded in the 26 s proteasome. We found that human PH-Fibs did not exhibit significant changes in mRNA levels of HIF1A, HIF2A, PHD1–3, and VHL compared with CO-Fibs (see Figure E4). Because PHD activity, and thus HIFα protein hydroxylation, could also be negatively impacted by cosubstrates other than O2, we decided to test the hypothesis that increased HIFα protein stability in normoxic human PH-Fibs is due to reduced HIFα protein hydroxylation. This was done by determining the levels of hydroxylated HIFα (using anti-HIF1α hydroxyproline-Pro564–specific antibody; HIF2α hydroxylation antibody is not available) relative to total HIF1α protein in human PH-Fibs cultured under normoxia. Hep3B cells are often used as a positive control for HIFα protein hydroxylation and degradation (25). Normoxic Hep3B cells treated with MG132 (a proteasome inhibitor to prevent degradation of hydroxylated HIFα protein) exhibited high levels of hydroxylated HIF1α protein (see Figure E5B) that was significantly reduced in normoxic Hep3B/MG132 cells treated with the PHD inhibitor DFX (see Figure E5B) despite similar levels of total HIF1α protein in Hep3B/MG132 and Hep3B/MG132 + DFX cells (see Figure E5A). This indicated that the hydroxylation-specific antibody correctly detected a hydroxylated HIF1α protein. Although HIF1α protein was detected in human PH-Fib3 (see Figure E5A), no hydroxylated HIF1α was detected (see Figure E5B). We then loaded different amounts of Hep3B/MG132 lysates and fixed quantities of PH-Fib lysate (Figures 3C and E5C and E5D). The purpose of this is to have lanes from Hep3B/MG132 cells that contain similar or lower amounts of total HIF1α compared with that in PH-Fibs. We found that, in all three human PH-Fibs, despite the total HIF1α protein detected in Hep3B/MG132 cells (some lanes) being lower than the HIF1α protein detected in human PH-Fibs, the hydroxylated HIF1α protein levels detected in Hep3B/MG132 cells were much higher than that in human PH-Fibs (Figures 3C and E5D). Consistently, the ratio of hydroxyl-HIF1α versus total HIF1α protein in human PH-Fibs was lower than that in Hep3B cells (Figure 3C, right).

Effects of HIF Inhibition on Human PH-Fib Gene Expression

We then examined the impact of HIF inhibition on the expression of direct HIF target genes and the other “persistently activated” genes in human PH-Fibs (Figures 3D and 3E and E6 and E7) under normoxia and hypoxia. Under normoxia, HIF1A and HIF2A siRNAs reduced or increased levels of CA9 (see Figure E6B), respectively, similar to what has been observed in cancer cells (26). However, neither HIF1A nor HIF2A siRNA, or even a combination of both HIFA siRNAs, reduced mRNA levels of most other HIF target genes (see Figures E6B and E7A and E7B). Hypoxia significantly upregulated expression of classical HIF targets such as CA9, GLUT1, NDRG1, and Apelin/APLN in human PH-Fibs (see Figures E6B and E7A and E7B). Interestingly, significant inhibition of hypoxia-mediated induction of CA9, GLUT1, hexokinase 2/HK2, lactate dehydrogenase A/LDHA, and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1/PDK1 was observed in cells targeted with HIF1A, but not HIF2A, siRNA, suggesting that these genes were HIF1-specific targets in human PH-Fibs (see Figures E6B and E7A). Hypoxia-mediated induction of NDRG1, APLN, ADM, EGLN3, and VEGF in human PH-Fibs was completely blocked only by combined HIF1A/HIF2A siRNAs; it was reduced slightly or not reduced at all by single HIF1A or HIF2A siRNA (see Figures E6B and E7B), suggesting that these genes were common targets of HIF1 and HIF2 in human PH-Fibs.

In normoxic conditions, HIF1A, HIF2A, or combined HIFA siRNAs did not alter the mRNA levels of the other persistently activated genes, including cytokines and chemokines (CCL2, CSF2, and CXCL12; Figure 3D), GFs (FGF1 and TGFA; Figure 3E), or antiapoptotic genes (BCL2, BCL2L1, and BIRC5; Figure E6C) in human PH-Fibs. In addition, different from classical HIF target genes (see Figures E6B and E7A and E7B), these persistently activated genes were not induced by hypoxia in human PH-Fibs (see Figures 3D and 3E and E6C). Consistently, HIF siRNAs had no impact on the mRNA levels of these factors in PH-Fibs cultured under hypoxia (see Figures 3D and 3E and E6C). Further, hypoxia did not increase proliferation of human PH-Fibs. Also, HIFA siRNA, alone or in combination, had no significant effect on PH-Fib proliferation under normoxic and hypoxic conditions (see Figure E7C).

Bovine PH Distal PAs Exhibit Increased Expression of HIF Targets, Cytokines/Chemokines, GFs, Antiapoptosis Markers, and Proliferation Markers

We decided to examine the role of HIF in hypoxia-induced PH in young calves. As opposed to human PAH, the bovine PH model is based on hypoxic exposure and likely involves direct HIF activation. Also, the calf model represents an early stage of the disease and is well known to be characterized by significant changes in proliferation, inflammation, and apoptosis resistance.

Distal PAs (diameter <2 mm) from calves with hypoxic PH exhibited increased mRNA levels of direct HIF target genes (CA9, GLUT1, and NDRG1; Figure 4A), cytokines/chemokines (CSF2 and CXCL12; Figure 4B), GFs (FGF1, PDGFb, and TGFA; Figure 4C), apoptosis-resistance genes (BCL2, BCL2L1, and BIRC5; Figure 4D), and proliferation markers (MKI67 and PCNA; Figure 4E).

Bovine PH-Fibs Exhibit Higher Expression Levels of Cytokines/Chemokines and GFs than PH-SMCs and PH-ECs

Compared with their respective controls, the HIF target gene GLUT1, but not CA9 and NDRG1, was persistently increased in bovine PH-Fibs and PH-ECs cultured in normoxia (Figures 5C and E8D). However, these genes were not increased in bovine PH-SMCs (see Figure E8A). Similar to what has been observed in human PH-Fibs, compared with their respective controls, bovine PH-Fibs were found to exhibit increased mRNA levels of many cytokines/chemokines and GFs, whereas bovine PH-ECs and bovine PH-SMCs exhibited no changes or reduced expression of a subset of these genes (Figures 5A and 5B). Further, bovine PH-Fibs expressed higher mRNA levels of CCL2 and IL6 (Figure 5A) and FGF1, FGF2, and TGFA (Figure 5B) compared with PH-SMCs or PH-ECs. Because increased protein levels of CCL2/MCP1, CXCL12/SDF1, and IL6 in bovine PH-Fibs have been reported (13, 27), we performed WB analysis of selected GFs, FGF2 and TGFA. Similar to increased mRNA levels, bovine PH-Fibs exhibited increased FGF2 protein levels compared with bovine CO-Fibs (see Figure E9). However, TGFA protein was not detected by WB in bovine CO- and PH-Fibs (not shown). Consistent with our previous study (13), bovine PH-Fibs also exhibited increased expression of antiapoptotic genes (BCL2, BCL2L1, and BIRC5; Figure 5D) and proliferation markers (MKI67 and PCNA; Figure 5E) compared with CO-Fibs. Bovine PH-SMCs exhibited increased mRNA levels of BIRC5 but not BCL2 and BCL2L1 (see Figure E8B), whereas bovine PH-ECs exhibited increased mRNA levels of BCL2 and BIRC5 but not BCL2L1 (see Figure E8E), compared with their respective controls. Interestingly, similar to bovine PH-Fibs, bovine PH-SMCs and PH-ECs exhibited increased mRNA levels of proliferation markers MKI67 and PCNA (see Figures E8C and E8F).

Effects of HIF Inhibition on Bovine PH-Fib Gene Expression

We also examined the levels of HIFα protein in bovine CO- and PH-Fibs under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. Similar levels of HIF1α protein were detected in bovine CO- and PH-Fibs under normoxic conditions (Figures 6A and 6B). (Note: One chronically hypoxic calf, PH-3, exhibited slightly increased HIF1α protein levels under normoxic conditions.) In addition, in CO- and PH-Fibs, hypoxia significantly, but similarly, increased the HIF1α protein levels (Figures 6A and 6B). HIF1A siRNA (knockdown efficiency of 90%) completely abolished the HIF1α protein band in bovine PH-Fibs, confirming the identities of the HIF1α protein bands in WBs (Figure 6C). However, we had difficulty finding a good antibody to detect bovine HIF2α protein. For example, the HIF2α antibody that successfully detected human HIF2α protein (Figures 3A and E3) detected a 95-kD protein (115 kD is the expected HIF2α protein size). This 95-kD protein was minimally induced by hypoxia (see Figure E10A) and minimally reduced by HIF2A siRNA (see Figure E10B), although the HIF2A siRNA reduced HIF2A mRNA levels by 80% (see Figure E11A). In addition, bovine CO-Fib-4 (see Figure E10A), which was deficient in the 95-kD protein, still exhibited similar hypoxia-mediated induction of several HIF2 target genes compared with other CO-Fibs (see Figure E10C). These data indicated that the 95-kD protein is not bovine HIF2α protein.

Under normoxia, HIF1A or HIF2A siRNAs reduced mRNA levels of some HIF target genes such as NDRG1, PDK1, and ADM (see Figures E11B and E12A and E12B). Hypoxia significantly upregulated expression of all HIF target genes assessed (see Figures E11B and E12A and E12B). Interestingly, complete inhibition of hypoxia-mediated induction of CA9, GLUT1, HK2, LDHA, and PDK1 was observed in cells targeted with HIF1A siRNA, suggesting that these genes are HIF1-specific targets (see Figures E11B and E12A). Hypoxic induction of NDRG1, APLN, ADM, EGLN3, and VEGF was completely blocked only by combined HIF1A and HIF2A siRNAs, indicating that these are HIF1/HIF2 common targets (see Figures E11B and E12B). So far, we have not identified an HIF2-unique/specific gene in bovine PH-Fibs.

However, HIF inhibition (by HIF1A, HIF2A, or both siRNAs) had no impact on the mRNA levels of the other persistently activated genes, including CCL2, CSF2, CXCL12, and IL6 (Figure 6D), FGF2 and TGFA (Figure 6E), BCL2, BCL2L1, and BIRC5 (see Figure E11C), and MKI67 and PCNA (see Figure E11D), or on proliferation (see Figure E12C) in bovine PH-Fibs cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. Consistently, none of these genes were induced by hypoxia in bovine PH-Fibs (Figures 6D and 6E and E11C and E11D).

We also examined the role of HIFs in maintaining bovine PH-Fib gene expression using HIF1 and HIF2 pharmacologic inhibitors. HIF1 and HIF2 target gene specificity is well established in Hep3B cells (28). We found that echinomycin, a reported HIF1 inhibitor, also inhibited HIF2 activity in Hep3B cells (see Figure E13). At the same time, PT2399 was a specific HIF2 inhibitor (see Figure E13) in Hep3B. Consistently, in bovine PH-Fibs, echinomycin blocked hypoxic induction of HIF1 (CA9, GLUT1, HK2, LDHA, and PDK1) and HIF1/2 (NDGR1, APLN, ADM, EGLN3, and VEGF) target genes, whereas PT2399 reduced only hypoxia-mediated induction of HIF2/1 targets (NDRG1, APLN, ADM, EGLN3, and VEGF) (see Figures E14A and E15A and E15B). However, echinomycin did not affect expression of CCL2, CSF2, CXCL12, and IL6 (cytokines/chemokines; see Figure E14B) or BCL2 and BIRC5 (see Figure 14D). Although echinomycin significantly reduced the mRNA levels of TGFA, FGF2, BCL2L1, MKI67, and PCNA in PH-Fib (see Figures E15C–E15E), this effect was likely HIF-independent because these genes were not induced by hypoxia and echinomycin’s effects on expression of these genes were identical in bovine PH-Fibs cultured under normoxia or hypoxia. Further, echinomycin significantly and similarly reduced bovine PH-Fib proliferation (see Figure E15C) when these cells were cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions.

Discussion

Increased levels of HIFα proteins and many of their target genes are almost universally observed in the PAs of humans and animals with PH. Further, at least in small-animal models of PH, inhibition of HIF reduces the severity of lung vascular remodeling in treatment models. As such, HIF inhibition has been proposed as a potential new therapeutic target for human PH. To examine in great detail the possible effect of HIF inhibition in PH, we used ex vivo tissues and cells from humans and calves with PH because these systems might be a better platform than existing murine or rodent hypoxic models. We found that, using human PH-Fibs (HIFα protein is persistently stabilized) and bovine PH-Fibs (cells are derived from animals with hypoxia-induced PH), HIF inhibition reduces the mRNA levels of direct HIF targets but has no impact on the persistently activated genes that characterize the humans and animals with PH, including cytokines/chemokines, GFs, apoptosis-resistance genes, and proliferation markers. Thus, our study indicated that HIF inhibition is not sufficient to reverse the persistently activated phenotype of human and bovine PH-Fibs.

We began by first determining gene-expression changes in intact human PH pulmonary vessels, believing that such a study can verify the gene-expression changes in PH vessels in vivo because the vessels have not been exposed to an ex vivo environment. We observed that genes, including hypoxia-inducible genes, cytokines/chemokines, GFs, and apoptosis-resistance genes, whose increase has been reported in pulmonary vessels in humans with PH, are indeed overexpressed in PAs from patients with PAH compared with PAs from controls (3, 4, 17–24).

Because HIF activation in pulmonary vascular wall cells has been implicated in PH initiation (3, 4), we analyzed the expression of the same set of genes that were analyzed in human PAs in all three vascular cell types from control and PH PAs. The results revealed that, indeed, most of the genes that were found to be increased in PH PAs are also increased in one or more cell types, indicating a good reflection of PH vascular cell phenotype relative to the PH PA phenotype. Importantly, we found that the human PH-Fibs, not human PH-ECs or PH-SMCs, exhibit the most significant changes concerning the number of genes and the fold increase in inflammation and GF genes. In addition, we found that human PH-Fibs produce the highest levels of most inflammation and GF genes compared with human PH-SMCs and PH-ECs. Although comparing and contrasting the expression of cytokines/chemokines and GFs in PH-Fibs, ECs, and SMCs was not the primary goal of this study, these findings have extended and strengthened our previously raised hypothesis (based on the expression of cytokines/chemokines and GFs in bovine PH-Fibs and PH-SMCs [13]) concerning the importance of PH-Fibs in recruiting (CCL2 and CXCL12), retaining (VCAM1), and activating (CSF2) inflammatory cells such as monocytes/macrophages in PH vessels, which is a hallmark of chronic inflammation in PH vessels. The gene-expression study in human PH-Fibs also established a set of genes that could be used to test HIF’s role.

We examined the protein levels of HIFα in human PH-Fibs. We determined the levels of HIF1α and HIF2α protein in CO- and PH-Fibs under normoxia as well as under hypoxic conditions (hypoxia should increase HIFα protein levels). More importantly, we performed HIFα WBs in cells transfected with HIFA siRNA (HIF1A or HIF2A siRNA should abolish or reduce HIFα protein levels). Thus, we are confident that the bands we showed (<130 kD but >95 kD; approximately 115 kD) are true human HIF1α or HIF2α proteins. We must point out that previous studies lack experiments to confirm that the shown bands are truly HIFα protein; more puzzling in these studies is that the reported HIFα protein size ranged from 115 kD to <100 kD; sometimes, the molecular weight of the HIFα protein was not shown (5, 10, 12).

We found that human PH-Fibs exhibit dysregulation of HIFα protein stability because, compared with CO-Fibs, human PH-Fibs exhibit increased HIFα protein levels even when these cells are grown under normoxia. In addition, for the first time, we found significantly reduced HIF1α protein hydroxylation in human PH-Fibs compared with Hep3B cells cultured under normoxic conditions. We found that human PH-Fibs exhibit normal mRNA (protein levels have not been examined) levels of PHDs and VHL, indicating that reduced PHD activity is likely due to abnormal levels of PHD cosubstrates such as iron (Fe2+), α-ketoglutarate, or ascorbic acid. It is interesting to notice that the trichloroacetic acid cycle intermediates such as fumarate, malate, and succinate are increased in human PH-Fibs (29), and these trichloroacetic acid cycle intermediates are endogenous PHD inhibitors (25) because of their structural similarity to α-ketoglutarate.

We then determined the role of HIFs in maintaining the cell phenotype of human PH-Fibs. HIF inhibition reduced the expression of HIF target genes such as CA9 and ADM in normoxic human PH-Fibs, indicating that normoxic HIFα protein did have a role. As a subset of HIF target genes are well known to be involved in metabolic controls, the aberrantly activated HIFα protein stability may contribute to the persistent abnormally metabolic activities of these human PH-Fibs (29). However, HIF inhibition did not reduce the expression of every HIF target gene, suggesting that other transcription factor(s) also support HIF target gene expression in PH-Fibs, similar to what we have observed in cancer cells (30). Thus, targeting HIF alone may be insufficient to even normalize the altered metabolic pathways in PH-Fibs.

The fact that all direct HIF target genes are consistently increased in human PH-Fibs by hypoxia indicates that HIF activity is important in the expression of HIF direct targets in PH-Fibs, a result different from what is observed in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. It is interesting to notice that all the hypoxia-inducible genes reported here can be activated by HIF1, and none of them is solely activated by HIF2, suggesting a dominant role of HIF1 in hypoxia response in PH-Fibs. However, HIF2 does have its own role because HIF1-inhibited PH-Fibs still exhibit hypoxic induction of HIF1/2 common target genes. The fact that hypoxic induction of HIF1/2 common targets is totally blocked in cells targeted with both HIF siRNAs supports the effectiveness of inhibition of both HIFAs. Despite the effective HIF1/2 inhibition, we found that the high levels of cytokines/chemokines, GFs, and apoptosis-resistance genes in human PH-Fibs is not impacted by HIF1/2 siRNAs cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. Moreover, different from HIF targets, these genes are not induced by hypoxia.

We performed an almost identical set of experiments in the calf model of severe hypoxia-induced PH. PH in this model, unlike the human PAH condition, is the result of hypoxic exposure and, therefore, likely involves early and direct HIF activation. Further, the bovine model allows us to study the gene expression in the distal pulmonary vessels (diameter <2 mm) and the vascular structure cells established from the same size vessels. Interestingly, we found that bovine PH PAs exhibit increased expression of HIF targets, cytokines/chemokines, GFs, and antiapoptosis genes, similar to what was found in human PH/PAH PAs. One significant difference is that bovine PH distal PAs, but not human PH PAs, exhibit markedly increased levels of proliferation markers. This significant difference could be due to the fact that experimental bovine PH represents an early/ongoing stage of the disease (31) whereas human PH typically presents as a chronic and late or end stage of the disease.

We also found that, similar to human PH-Fibs, bovine PH-Fibs produce the highest levels of most inflammation and GF genes compared with bovine PH-SMCs and PH-ECs. On the contrary, regulation of HIF1α protein stability appears largely normal in bovine PH-Fibs; in other words, there is no persistent activation of hypoxia response and HIFα protein stability in bovine PH-Fib despite the fact that bovine PH-Fibs were established from calves with PH that were exposed to chronic hypoxia. Again, it is not clear whether HIFα protein misregulation in human PH-Fibs, but not in bovine PH-Fibs, is related to the fact that human PH is a more advanced disease than bovine PH.

We conclude that the 95-kD band detected by the HIF2α antibody in bovine Fibs is not an HIF2α protein (see Figure E10). Although we showed that the HIF2α antibody works quite well for HIF2α protein in human Fibs (Figure 3A), the same antibody also detects a non-HIF2α protein (size is between 95 and 72 kD) that is hypoxia-induced and exhibits greater intensity than the true HIF2α protein in human ECs (see Figure E16). In light of the difficulty in detecting the HIFα protein, particularly HIF2α, it is important to confirm if the “HIFα” band is truly HIFα protein using HIFA siRNA.

Similar to what is observed in human PH-Fibs, hypoxia activates classical HIF targets in bovine PH-Fibs. Again, HIF1 is a dominant HIF subunit in bovine PH-Fibs because HIF1A siRNA totally blocks hypoxia-mediated induction of HIF1 unique target genes such as CA9 and also reduces the fold of induction of common HIF1/HIF2 targets (see Figures E11B and E12A and E12B). Again, HIF2 has a role in bovine PH-Fibs because HIF1A siRNA-treated PH-Fibs still exhibit hypoxic induction of HIF1/2 common target genes. That complete block of hypoxic induction of HIF1/2 common targets in cells targeted with HIF1A and HIF2A siRNAs demonstrates the effectiveness of inhibition of both HIFAs despite the fact that we lacked an antibody to detect bovine HIF2α protein. Again, these data support the role of both HIFs in maintaining high expression levels of direct HIF target genes in bovine PH-Fibs under hypoxia. However, similar to what was observed in human PH-Fibs, inhibition of HIF1A or/and HIF2A by siRNA did not reduce the persistently activated genes such as cytokines/chemokines and GFs in bovine PH-Fibs under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. Further, these genes are not induced by hypoxia in bovine PH-Fibs.

To confirm the results of siRNA-mediated HIF inhibition, we used HIF1 or HIF2 chemical inhibitors. Our study indicated that echinomycin is not an HIF1-specific inhibitor but an HIF1/HIF2 common inhibitor. In addition, echinomycin also has an HIF-independent role, as it significantly reduced expression of multiple persistently activated genes that were clearly not HIF direct targets in bovine PH-Fibs. Thus, echinomycin should be further tested for PH treatment; however, the effect of echinomycin on PH treatment, if there is one, is likely due to its role in the inhibition of HIF-dependent plus HIF-independent activities.

In summary, different from most previous studies in which the effect of HIF inhibition was tested in rodent models of PH, followed by showing that HIF protein is overexpressed in human PH lungs in “confirmation” studies, in this study, we directly determined if HIF activity was important in maintaining the transcriptional changes observed in human and bovine PH-Fibs in culture, established from patients with PH or animals. Importantly, changes in gene transcription that we used to test HIF’s role in PH-Fibs have been demonstrated to be important in PH disease and included a sufficiently large number of genes that were involved in diverse pathways (3, 4, 17–24). Our study demonstrated that HIF inhibition blocks hypoxia-mediated or persistent induction of direct HIF target genes but has no impact on expression of cytokines/chemokines, GFs, apoptosis-resistance genes, and proliferation markers. Although future studies to determine the role of HIFs in maintaining the activated phenotype of other PH cells, including PH-SMCs, ECs, and cardiomyocytes, is required, based on the results in PH-Fibs in this study, we speculated that HIF inhibition alone might not exert dramatic effects in established PH. The fact that a significant set of genes are not induced by hypoxia in CO-Fibs (not shown) and in PH-Fibs brings into question the idea that hypoxia/HIF activation alone is directly responsible for the generation of the PH-Fib phenotype during PH initiation in animals despite the fact that we and others have previously shown that inhibition of HIF blocks hypoxia-induced PH development (12, 32–34). Our current hypothesis is that, during the development of hypoxia-induced PH in animals, hypoxia, hypoxia-induced inflammation (recruiting macrophages), and other signaling pathways together “transform” normal Fibs to PH-Fibs.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant P01 HL014985 and U.S. Department of Defense grants W81XWH1910259 and W81XWH2010249 (K.R.S.).

Author Contributions: C.-J.H. and K.R.S. conceived and planned the experiments. C.-J.H., A.L., A.G., L.W., M.L., R.D.B., S.R., R.M.T., and H.Z. carried out the experiments and prepared figures. C.-J.H. and K.R.S. wrote the manuscript. V.O.K. performed statistical analysis. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript.

This article has a data supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of content online at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2022-0114OC on March 21, 2023

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Humbert M, Galiè N, McLaughlin VV, Rubin LJ, Simonneau G. An insider view on the World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension. Lancet Respir Med . 2019;7:484–485. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Olschewski A, Berghausen EM, Eichstaedt CA, Fleischmann BK, Grünig E, Grünig G, et al. Pathobiology, pathology and genetics of pulmonary hypertension: update from the Cologne Consensus Conference 2018. Int J Cardiol . 2018;272S:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pullamsetti SS, Mamazhakypov A, Weissmann N, Seeger W, Savai R. Hypoxia-inducible factor signaling in pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest . 2020;130:5638–5651. doi: 10.1172/JCI137558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shimoda LA, Yun X, Sikka G. Revisiting the role of hypoxia-inducible factors in pulmonary hypertension. Curr Opin Physiol . 2019;7:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cophys.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dai Z, Zhu MM, Peng Y, Machireddy N, Evans CE, Machado R, et al. Therapeutic targeting of vascular remodeling and right heart failure in pulmonary arterial hypertension with a HIF-2α inhibitor. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2018;198:1423–1434. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201710-2079OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ghosh MC, Zhang DL, Jeong SY, Kovtunovych G, Ollivierre-Wilson H, Noguchi A, et al. Deletion of iron regulatory protein 1 causes polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension in mice through translational derepression of HIF2α. Cell Metab . 2013;17:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Macias D, Moore S, Crosby A, Southwood M, Du X, Tan H, et al. Targeting HIF2α-ARNT hetero-dimerisation as a novel therapeutic strategy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J . 2021;57:1902061. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02061-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fijalkowska I, Xu W, Comhair SA, Janocha AJ, Mavrakis LA, Krishnamachary B, et al. Hypoxia inducible-factor1alpha regulates the metabolic shift of pulmonary hypertensive endothelial cells. Am J Pathol . 2010;176:1130–1138. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tuder RM, Chacon M, Alger L, Wang J, Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Kasahara Y, et al. Expression of angiogenesis-related molecules in plexiform lesions in severe pulmonary hypertension: evidence for a process of disordered angiogenesis. J Pathol . 2001;195:367–374. doi: 10.1002/path.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barnes EA, Chen CH, Sedan O, Cornfield DN. Loss of smooth muscle cell hypoxia inducible factor-1α underlies increased vascular contractility in pulmonary hypertension. FASEB J . 2017;31:650–662. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600557R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marsboom G, Toth PT, Ryan JJ, Hong Z, Wu X, Fang YH, et al. Dynamin-related protein 1-mediated mitochondrial mitotic fission permits hyperproliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells and offers a novel therapeutic target in pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res . 2012;110:1484–1497. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.263848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tang H, Babicheva A, McDermott KM, Gu Y, Ayon RJ, Song S, et al. Endothelial HIF-2α contributes to severe pulmonary hypertension due to endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2018;314:L256–L275. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00096.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li M, Riddle SR, Frid MG, El Kasmi KC, McKinsey TA, Sokol RJ, et al. Emergence of fibroblasts with a proinflammatory epigenetically altered phenotype in severe hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. J Immunol . 2011;187:2711–2722. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schonenberger D, Harlander S, Rajski M, Jacobs RA, Lundby AK, Adlesic M, et al. Formation of renal cysts and tumors in Vhl/Trp53-deficient mice requires HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha. Cancer Res . 2016;76:2025–2036. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murakami A, Wang L, Kalhorn S, Schraml P, Rathmell WK, Tan AC, et al. Context-dependent role for chromatin remodeling component PBRM1/BAF180 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncogenesis . 2017;6:e287. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2016.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shen C, Beroukhim R, Schumacher SE, Zhou J, Chang M, Signoretti S, et al. Genetic and functional studies implicate HIF1α as a 14q kidney cancer suppressor gene. Cancer Discov . 2011;1:222–235. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stenmark KR, Bouchey D, Nemenoff R, Dempsey EC, Das M. Hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling: contribution of the adventitial fibroblasts. Physiol Res . 2000;49:503–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duncan M, Wagner BD, Murray K, Allen J, Colvin K, Accurso FJ, et al. Circulating cytokines and growth factors in pediatric pulmonary hypertension. Mediators Inflamm . 2012;2012:143428. doi: 10.1155/2012/143428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hassoun PM, Mouthon L, Barberà JA, Eddahibi S, Flores SC, Grimminger F, et al. Inflammation, growth factors, and pulmonary vascular remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol . 2009;54:S10–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Humbert M, Monti G, Brenot F, Sitbon O, Portier A, Grangeot-Keros L, et al. Increased interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 serum concentrations in severe primary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 1995;151:1628–1631. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.5.7735624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rabinovitch M, Guignabert C, Humbert M, Nicolls MR. Inflammation and immunity in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Res . 2014;115:165–175. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Selimovic N, Bergh CH, Andersson B, Sakiniene E, Carlsten H, Rundqvist B. Growth factors and interleukin-6 across the lung circulation in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J . 2009;34:662–668. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00174908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Izikki M, Guignabert C, Fadel E, Humbert M, Tu L, Zadigue P, et al. Endothelial-derived FGF2 contributes to the progression of pulmonary hypertension in humans and rodents. J Clin Invest . 2009;119:512–523. doi: 10.1172/JCI35070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tu L, Dewachter L, Gore B, Fadel E, Dartevelle P, Simonneau G, et al. Autocrine fibroblast growth factor-2 signaling contributes to altered endothelial phenotype in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2011;45:311–322. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0317OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pan Y, Mansfield KD, Bertozzi CC, Rudenko V, Chan DA, Giaccia AJ, et al. Multiple factors affecting cellular redox status and energy metabolism modulate hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase activity in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell Biol . 2007;27:912–925. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01223-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pawlus MR, Wang L, Ware K, Hu CJ. Upstream stimulatory factor 2 and hypoxia-inducible factor 2α (HIF2α) cooperatively activate HIF2 target genes during hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol . 2012;32:4595–4610. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00724-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. El Kasmi KC, Pugliese SC, Riddle SR, Poth JM, Anderson AL, Frid MG, et al. Adventitial fibroblasts induce a distinct proinflammatory/profibrotic macrophage phenotype in pulmonary hypertension. J Immunol . 2014;193:597–609. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hu CJ, Sataur A, Wang L, Chen H, Simon MC. The N-terminal transactivation domain confers target gene specificity of hypoxia-inducible factors HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha. Mol Biol Cell . 2007;18:4528–4542. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-05-0419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Plecitá-Hlavatá L, Tauber J, Li M, Zhang H, Flockton AR, Pullamsetti SS, et al. Constitutive reprogramming of fibroblast mitochondrial metabolism in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2016;55:47–57. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0142OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pawlus MR, Hu CJ. Enhanceosomes as integrators of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) and other transcription factors in the hypoxic transcriptional response. Cell Signal . 2013;25:1895–1903. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bakerman PR, Stenmark KR, Fisher JH. Alpha-skeletal actin messenger RNA increases in acute right ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Physiol . 1990;258:L173–L178. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1990.258.4.L173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brusselmans K, Compernolle V, Tjwa M, Wiesener MS, Maxwell PH, Collen D, et al. Heterozygous deficiency of hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha protects mice against pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction during prolonged hypoxia. J Clin Invest . 2003;111:1519–1527. doi: 10.1172/JCI15496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dai Z, Li M, Wharton J, Zhu MM, Zhao YY. Prolyl-4 hydroxylase 2 (PHD2) deficiency in endothelial cells and hematopoietic cells induces obliterative vascular remodeling and severe pulmonary arterial hypertension in mice and humans through hypoxia-inducible factor-2α. Circulation . 2016;133:2447–2458. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hu CJ, Poth JM, Zhang H, Flockton A, Laux A, Kumar S, et al. Suppression of HIF2 signalling attenuates the initiation of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J . 2019;54:1900378. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00378-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]