Abstract

Long non-coding RNAs are a very versatile class of molecules that can have important roles in regulating a cells function, including regulating other genes on the transcriptional level. One of these mechanisms is that RNA can directly interact with DNA thereby recruiting additional components such as proteins to these sites via an RNA:dsDNA triplex formation. We genetically deleted the triplex forming sequence (FendrrBox) from the lncRNA Fendrr in mice and found that this FendrrBox is partially required for Fendrr function in vivo. We found that the loss of the triplex forming site in developing lungs causes a dysregulation of gene programs associated with lung fibrosis. A set of these genes contain a triplex site directly at their promoter and are expressed in lung fibroblasts. We biophysically confirmed the formation of an RNA:dsDNA triplex with target promoters in vitro. We found that Fendrr with the Wnt signalling pathway regulates these genes, implicating that Fendrr synergizes with Wnt signalling in lung fibrosis.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

INTRODUCTION

The number of loci in mammalian genomes, which produce RNA that do not code for proteins is higher than the number of loci that produce protein-coding RNAs (1,2). These non-protein coding RNAs are commonly referred to long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) if their transcript length exceeds 200 nucleotides. Many of these lncRNA loci are not conserved across species. However, some loci are conserved on the syntenic level and some even on the transcript level. One of the syntenic conserved lncRNAs is the Fendrr gene, divergently expressed from the essential transcription factor coding gene Foxf1. Both genes have been implicated in various developmental processes (3–5) and particularly in heart and lung development (6–9).

The mouse Fendrr and its human orthologue (FENDRR) seem to have opposing functions on fibrosis in heart and lung tissue, indicating that secondary cues such as active signalling pathways might be required. In a transverse aortic constriction (TAC) mouse model, Fendrr was upregulated in heart tissue. Loss of Fendrr RNA via an siRNA approach alleviated fibrosis induced by TAC, demonstrating a pro-fibrotic function for Fendrr in the heart (10). In contrast, in humans with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) and in mice with bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, the Fendrr/FENDRR RNA was downregulated (11). In addition, depletion of FENDRR increases cellular senescence of human lung fibroblasts. Overexpression of human FENDRR in mice reduced bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis, revealing an anti-apoptotic function of FENDRR in lungs. Moreover, this result also suggests some conservation of mouse and human Fendrr/FENDRR in this process (11).

In the lung, FENDRR is a potential target for intervention to counteract fibrosis. The analysis of its function in this process and how target genes are regulated is of interest to develop RNA-based therapies (12). LncRNAs can exert their function on gene regulation via many different mechanisms (13). One mechanism is that the RNA is tethered to genomic DNA either by base-pairing or by RNA:dsDNA triplex formation involving Hoogsteen base pairing (14). Here, we deleted such a triplex formation site in the Fendrr lncRNA in vivo. We identified genes that are regulated by Fendrr in the developing mouse lung and require the triplex forming RNA element, which we termed the FendrrBox. The gene network that is regulated by Fendrr and requires the FendrrBox element is associated with extracellular matrix deployment and with lung fibrosis. We have confirmed that the expression of these genes is dependent on the presence of the full-length Fendrr and the FendrrBox specifically, in conjunction with active Wnt signalling. This indicates that Fendrr and particularly its FendrrBox element is likely to play a role in Wnt-dependent lung fibrosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culturing of mouse ES cells

The mouse embryonic stem cells (mESC) were either cultured in feeder free 2i media or on feeder cells (mitomycin inactivated SWISS embryonic fibroblasts) containing LIF1 (1000 U/ml). 2i media: 1:1 Neurobasal (Gibco #21103049) :F12/DMEM (Gibco #12634-010), 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco), 1x Penicillin/ Streptomycin (100× penicillin (5000 U/ml)/streptomycin (5000 ug/ml), Sigma #P4458-100ML, 2 mM glutamine (100× GlutaMAX™ Supplement, Gibco #35050-038), 1× non-essential amino acids (100× MEM NEAA, Gibco #11140-035), 1× sodium pyruvate (100×, Gibco, #11360-039), 0.5× B-27 supplement, serum-free (Gibco #17504-044), 0.5× N-2 supplement (Gibco # 17502-048), glycogen synthase kinase 3 inhibitor (GSK-Inhibitor, Sigma, #SML1046-25MG), MAP-kinase inhibitor (MEK-Inhibitor Sigma, #PZ0162), 1000 U/ml Murine_Leukemia_Inhibitory_Factor ESGRO (107 LIF, Chemicon #ESG1107), ES-serum media: knockout Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM Gibco#10829-018), ES cell tested fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM glutamine, 1× penicillin/streptomycin, 1× non-essential amino acids, 110 nM ß-Mercaptoethanol, 1× nucleoside (100x Chemicon #ES-008D), 1000 U/ml LIF1.

The cells were split with TrypLE Express (1×, Gibco #12605–010) and the reaction was stopped with the same amount of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS Gibco #100100239) followed by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 5min. The cells were frozen in the appropriate media containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma Aldrich #D5879). To minimize any effect of the 2i (15) on the developmental potential mESC were only kept in 2i for the antibiotic selection after transient transfection with CRISPR/Cas9 or mini gene integration and DNA generation for genotyping. At all other times cells were maintained on ES-Serum media on feeder cells.

Generation of transgenic or CRISPR/cas9 edited mESC

Guide RNAs were designed, using the crispr.mit.edu website with the nickase option. The following, top-scoring guide RNAs were selected and cloned into pX330 (Addgene, #42230) plasmid to allow for transient puromycin selection after transfection. The sgRNAs used for the deletion of the FendrrBox are upstream(L): TCAGGCAACACTCACTGGAC, downstream(R): GGGAAGACATGGGGGAGTAA. Wild-type F1G4 cells were transiently transfected with 2μg/mL puromycin (Gibco, #10130127) for 2 days and 1 μg/ml puromycin for 1 day. Single mESC clones were picked 7–8 days after transfection and plated onto 96-well synthemax (Sigma, #CLS3535) coated plates and screened for genomic DNA deletion by PCR using primers outside of the deletion region.

Genotyping of Fendrr3xpA/3xpA and Fendrrem7Phg/em7Phg tissues

The REDExtract-N-Amp™ Tissue PCR Kit (Merck, XNAT) was used for genotyping for all tissue explants. Genotyping of FendrrNull (Fendrr3xpA/3xpA) embryos with the three primers: Fendrr3xpA_F1: GCGCTCCCCACTCACGTTCC, Fendrr3xpA_Ra1: AGGTTCCTTCACAAAGATCCCAAGC, genoNCrna_Ra4: AAGATGGGGAACCGAGAATCCAAAG that will generate a 696bp band in wild type and a 371bp band when the 3xpA allele is present. Genotyping of FendrrBox (Fendrrem7Phg/em7Phg) embryo tissues with: FendrrBox_F2: ATGCTTCCAAGGAAGGACGG, FendrrBox_R2: CTTGACGCCAAGCTCCTGTA that generate a 602bp product in wild type and a 503bp product when the FendrrBox is missing.

Culturing of NIH3T3 cells

NIH3T3 cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco #11960-044) containing 10% Bovine Serum (Fisher Scientific #11510526), 1% GlutaMAX™ (Gibco #35050–038) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Sigma Aldrich #P4458). For the experiment, the cells were detached using Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco #25300-054). The reaction was stopped by adding double the amount of fresh media followed by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 4 min. The pellet was resuspended in fresh medium and counted using a Chemometec NucleoCounter NC-200 Automated Cell Counter (Wotol #2194080-18). 0.15 × 106 cells were seeded per well (Greiner Bio-One™ #657160).

Generation of CRISPR/cas9 edited NIH3T3 cells

The same sgRNAs for deletion of the FendrrBox as used in the mESCs were used for the NIH3T3 cells (upstream(L): TCAGGCAACACTCACTGGAC, downstream(R): GGGAAGACATGGGGGAGTAA). The sgRNAs were cloned into an expression plasmid for two sgRNAs (addgene #100708). For selection purposes a CMV-mScarlet was inserted using the EcoRI restriction site. The plasmid was co-transfected into NIH3T3 cells with a Cas9-GFP plasmid (addgene #78311) as described above (1:3 Cas9 to sgRNA ratio). 48h after transfection the cells were detached and resuspended in DPBS containing 2mM EDTA (Invitrogen #AM9260G) and 2% bovine serum (Fisher Scientific #11510526). The cell suspension was passed through a 70 μm cell strainer (Corning™ #10788201) to obtain a single cell solution. GFP and mScarlet double-fluorescent single cells were sorted into 96-well plate using the FACSAria™ Fusion Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences) to obtain clonal cultures. Genotyping was conducted as described above. Positive clones harbouring the deletion of the FendrrBox were expanded and used for further experiments. The mutant cells were maintained and treated similar to wild type NIH3T3 cells.

Culturing of MLg cells

MLg cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco #11960-044) containing 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (PAN Biotech #P30-3300), 1% GlutaMAX™ (Gibco #35050–038) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Sigma Aldrich #P4458). For the experiment, the cells were handled and prepared as described above for NIH3T3 cells.

CRISPR-activation of fendrr and treatment of NIH3T3 cells

Three guide RNAs targeting the Fendrr promoter were designed using the crispor.tefor.net website (16). Fendrr_sg1: GGCCTCCGACGCTGCGCGCC, Fendrr_sg2: TCAACGTAAACACGTTCCGG, Fendrr_sg3: AGTTGGCCTGATGCCCCTAT. A non-specific guide RNA ctrl_sg: GGGTCTTCGAGAAGACCT served as control. The guide RNAs were cloned into the sgRNA(MS2) plasmid (addgene #61424). The CRISPR SAM plasmid (pRP[Exp]-Puro-CAG-dCAS9-VP64:T2A:MS2-p65-HSF1) was a gift from Mohamed Nemir from the Experimental Cardiology Unit Department of Medicine University of Lausanne Medical School.

For transfection, Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen #L3000001) was used following the manufacturer's guidelines. Briefly, 1 μg total plasmid DNA (1:3 SAM to gRNA ratio) was diluted in Opti-MEM (Gibco #31985062) and mixed with p3000 reagent. Lipofectamine reagent was diluted in Opti-MEM and subsequently added to the DNA mixture. During the incubation the cells were washed with DPBS (Gibco #14190250) and provided with fresh Opti-MEM. Transfection mix was added to the cells and incubated for 4 h at 37°C. After the incubation, the media was changed with full media containing FGF (10 ng/ml bFGF, Sigma Aldrich #F0291; 25 ng/ml rhFGF, R&D Systems #345-FG), BMP-4 (40 ng/ml, R&D Systems #5020-BP-010) or CHIR99021 (3 μM, Stemcell #72052). The treatment was replenished by changing media after 24 h, cells were harvested for RNA isolation after 48 h.

Lung preparation and RNA isolation

Staged embryo lungs were dissected from uteri into PBS and kept on ice in M2 media (Merck, M7167-50ML) until further processing. For direct RNA isolation the lung tissue was transferred into Precellys beads CK14 tubes (VWR, 10144–554) containing 1ml 900 μl Qiazol (Qiagen, #79306) and directly processed with a Bertin Minilys personal homogenizer. To remove the DNA 100 μl gDNA Eliminator solution was added and 180 μl Chloroform (AppliChem, #A3633) to separate the phases. The extraction mixture was centrifuge at full speed, 4°C for 15 min. The aqueous phase was mixed with the same amount of 70% ethanol and transferred to a micro or mini column depending of the amount of tissue and cells. The RNA was subsequently purified with the Qiagen RNAeasy Plus Min Kit (Qiagen, #74136) according to the manufacturer's manual. Remaining tissue from the same embryos was used for genotyping to select homozygous mutants.

Lung ex vivo culture

The lung culture was adopted from a previous published protocol (17). Lungs were dissected from the E12.5 staged embryos in ice-cold PBS containing 0.5% FCS. Lungs were then placed in holding medium: Leibovitz's L-15 Medium (ThermoFisher Scientific, 11415064) containing 1× Corning™ MITO + Serum Extender (Fisher scientific, 10787521) and 1× Pen/Strep. Explant media (Advanced DMEM/F12 (ThermoFisher Scientific, 12634010), 5× Corning™ MITO + Serum Extender, 1× Pen/Strep, 10% FCS) was placed into a 6-well tissue culture dish (0.8–1.0 ml) and the 6-well plate fitted with Falcon™ Cell Culture Inserts with 8 um pore size (Fisher Scientific, 08-771-20). The lungs were transferred from the holding medium onto the membrane with a sterile razor blade and 5–10 ul of holding media to keep the lungs wet. Cells were cultured at 37°C with an atmospheric CO2 of 7.5%. After the indicated time the lungs were removed from the membrane and RNA isolated as described above.

Generation of mouse embryos from mESCs

All animal procedures were conducted as approved by local authorities (LAGeSo Berlin) under the license number G0368/08. Embryos were generated by tetraploid morula aggregation of embryonic stem cells as described in (18). SWISS mice were used for either wild-type donor (to generate tetraploid morula) or transgenic recipient host (as foster mothers for transgenic mutant embryos). All transgenic embryos and mESC lines were initially on a hybrid F1G4 (C57Bl6/129S6) background and backcrossed seven times to C57Bl6J for the preparations of embryonic lungs. The study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org/).

Real-time quantitative PCR analysis

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis was carried out on a StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies) using Fast SYBR™ Green Master Mix (ThermoFisher Scientific #4385612). RNA levels were normalized to housekeeping gene. Quantification was calculated using the ΔΔCt method (19). Rpl10 served as housekeeping control gene for qPCR. The primer concentration for single a single reaction was 250nM. Error bars indicate the standard error from biological replicates, each consisting of technical triplicates. The Oligonucleotides for the qPCRs are as follows: Emp2_qPCR_fw:GCTTCTCTGCTGACCTCTGG, Emp2_qPCR_rv:CGAACCTCTCTCCCTGCTTG, Serpinb6b_qPCR_fw:ATAAGCGTCTCCTCAGCCCT, Serpinb6b_qPCR_rv:CTTTTCCCCGAAGAGCCTGT, Trim16_qPCR_fw:CCACACCAGGAGAACAGCAA,Trim16_qPCR_rv:AGGTCCAACTGCATACACCG,Fn1_qPCR_fw:GAGTAGACCCCAGGCACCTA,Fn1_qPCR_rv:GTGTGCTCTCCTGGTTCTCC,Akr1c14_qPCR_fw:TGGTCACTTCATCCCTGCAC,Akr1c14_qPCR_rv:GCCTGGCCTACTTCCTCTTC,Ager_qPCR_fw:TGGTCAGAACATCACAGCCC,Ager_qPCR_rv:CATTGGGGAGGATTCGAGCC,Fendrr_qPCR_fw:CTGCCCGTGTGGTTATAATG,Fendrr_qPCR_rv:TGACTCTCAAGTGGGTGCTG,Foxf1_qPCR_fw:CAAAACAGTCACAACGGGCC,Foxf1_qPCR_rv:GCCTCACCTCACATCACACA,Rpl10_qPCR_fw:GCTCCACCCTTTCCATGTCA,Rpl10_qPCR_rv:TGCAACTTGGTTCGGATGGA.

Triplex prediction

To calculate Fendrr triplex targets, deregulated (DE) genes from FendrrNull and FendrrBox RNA-Seq output were intersected and RNA-DNA triplex forming potential of the shared genes were calculated with Triplex Domain Finder (TDF) algorithm (20). The command was executed with promotertest option and –organism = mm10. The rest of the options were set to the default settings.

CD spectroscopy and melting curve analysis

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were acquired on a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter. The measurements were recorded from 210 to 320 nm at 25°C using 1 cm path length quartz cuvette. CD spectra were recorded on 8 μM samples of each DNA duplex and RNA:dsDNA triplex in 20 mM LiOAc, 10 mM MgCl2, pH 5.5. For the RNA:dsDNA triplex an excess of 5 eq. RNA was used. By hybridization DNA duplex and RNA:dsDNA triplex were formed. Therefore, the complementary DNA strands were incubated at 95°C for 5 min and afterwards cooled down to room temperature. For the triplex formation RNA was added to the DNA duplex and incubated at 60°C for 1 h and then cooled down to room temperature (21). The sequences used are listed below. Spectra were acquired with 8 scans and the data was smoothed with Savitzky-Golay filters. Observed ellipticities recorded in millidegree (mdeg) were converted to molar ellipticity [θ] = deg × cm2 × dmol-1. Melting curves were acquired at constant wavelength using a temperature rate of 1°C/min in a range from 5°C to 95°C. All melting temperature data was converted to normalized ellipticity and evaluated by the following equation using SigmaPlot 12.5:

|

The RNA and DNA oligos used here were: Fendrr: UCUUCUCUCUCCUCUCUUCUCCCUCCCCUC (30 nt), Emp2 (GA-rich): AGGAGAGAGAGGAGAGAGGGGAGAGAGGGG (30 nt), Emp2 (CT-rich): CCCCTCTCTCCCCTCTCTCCTCTCTCTCCT (30 nt), Foxf1 (GA-rich): CCGAGCCGGGAGGAGGAGGAGGAGCAGGAGGGGAGGGAGGGGAGGGGGCT (50 nt), Foxf1 (CT-rich): AGCCCCCTCCCCTCCCTCCCCTCCTGCTCCTCCTCCTCCTCCCGGCTCGG (50 nt), Serpin6B (CT-rich): CCCCCTCTTCCTCTTCTCTTCTTTCC, Serpin6B (GA-rich): GGAAAGAAGAGAAGAGGAAGAGGGGG, Ager (CT-rich): CCCACCACCCTCTTCACTCCC, Ager (GA-rich): GGGAGTGAAGAGGGTGGTGGG, Trim16 (CT-rich): CCTCCCCCTCCCCTTCTCTCTACTCC, Trim16 (GA-rich): GGAGTAGAGAGAAGGGGAGGGGGAGG, Akr1c14 (CT-rich): TCTTCCCCTTCCTTACTCTCTCTTCT, Akr1c14 (GA-rich): AGAAGAGAGAGTAAGGAAGGGGAAGA, Fn1 (CT-rich): GTCCGACTCCTCCCGCCCCTCC, Fn1 (GA-rich): GGAGGGGCGGGAGGAGTCGGAC.

Sequencing and analysis of RNA-seq

RNA was treated to deplete rRNA using Ribo-Minus technology. Libraries were prepared from purified RNA using ScriptSeq™ v2 and were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq platform. We obtained 60 million paired-end reads of 50 bp length. Read mapping was done with STAR aligner using default settings with the option –outSAMtype BAM SortedByCoordinate (22) with default settings. For known transcript models we used GRCm38.100 Ensembl annotations downloaded from Ensembl repository (23). Counting reads over gene model was carried out using GenomicFeatures Bioconductor package (24). The aligned reads were analysed with custom R scripts in order to obtain gene expression measures. For normalization of read counts and identification of differentially expressed genes we used DESeq2 with Padj < 0.01 cutoff (25). GO term and KEGG pathways were analysed using g:Profiler (26) and metascape (27). The data are deposited to GEO and can be downloaded under the accession number GSE186703.

RESULTS

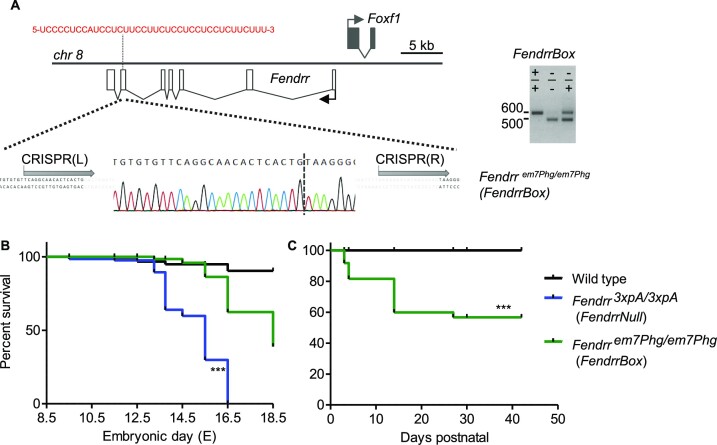

The FendrrBox region is partially required for Fendrr RNA function

We established previously that the long non-coding RNA Fendrr is an essential lncRNA transcript in early heart development in the murine embryo (3). In addition, the Fendrr locus was shown to play a role in lung development (7). Expression profiling of pathological human lungs revealed that FENDRR is dysregulated in disease settings (28). In the second to last exon of the murine Fendrr lncRNA transcript resides a UC-rich low complexity region of 38bp, which can bind to target loci and thereby tether the Fendrr lncRNA to the genome of target genes (29). To address if this region is required for Fendrr function, we deleted this FendrrBox (Fendrrem7Phg/em7Phg) in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) (Figure 1A). We generated embryos from these mESCs and compared them to the Fendrr null phenotype (Figure 1B). The FendrrNull (Fendrr3xpA/3xpA) embryos exhibit increased lethality starting at the embryonic stage E12.5 and all embryos were dead prior to birth and in the process of resorption (3). In contrast, the FendrrBox mutants, which survived longer, displayed an onset of lethality later during development (E16.5) and some embryos survived until short before birth. The surviving embryos of the FendrrBox mutants were born and displayed an increased postnatal lethality (Figure 1C). Thus, FendrrBox mutants exhibit an incomplete genetic penetrance for survival compared to the fully penetrant FendrrNull mutation. This shows that the FendrrBox element is most likely partially required for Fendrr function in embryo development and for postnatal survival, while the full Fendrr transcript is essential.

Figure 1.

Position and requirement of the FendrrBox for survival. (A) Schematic of the Fendrr locus and the localization of the DNA interacting region (FendrrBox) in exon six. The localization of the gRNA binding sites (grey arrows) are indicated and the resulting deletion of 99bp, including the FendrrBox, in the genome that generates the Fendrrem7PhG/em7PhG allele (FendrrBox). Genotyping of biopsies from embryos of the different genotypes. (B) Embryos and (C) life animals were generated by tetraploid aggregation and the surviving animals counted. *** P> 0.0001 by log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test.

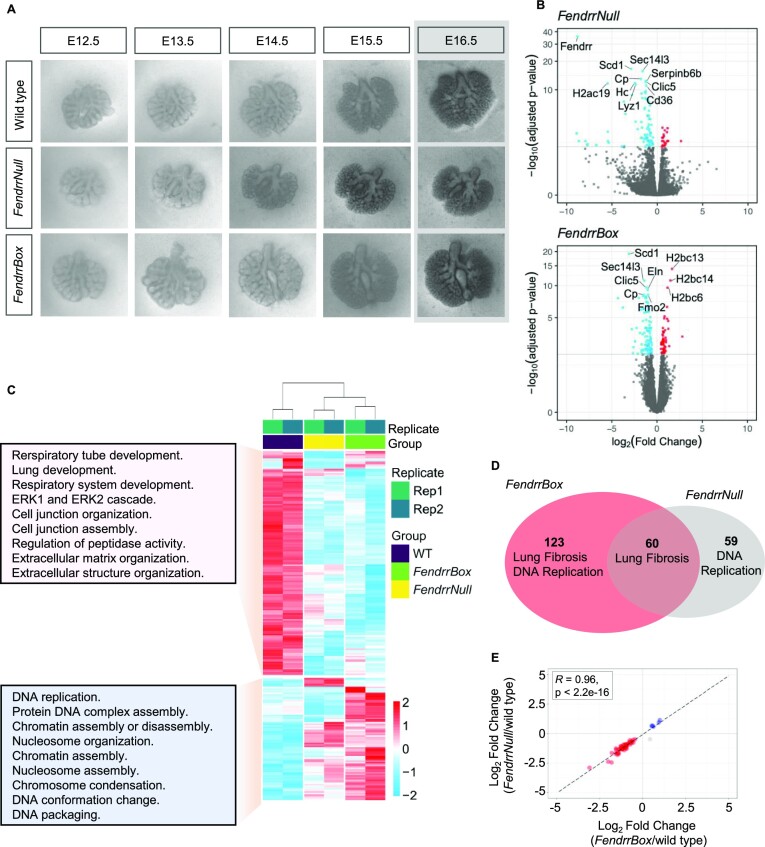

Gene expression in FendrrNull and FendrrBox mutant developing lungs

Given the involvement of Fendrr in lung development (7) and the involvement of mutations in human FENDRR in lung disease (9), we wanted to determine the genes affected by a loss of Fendrr or the FendrrBox in developing lungs to identify Fendrr target genes. However, when we collected the lungs from surviving embryos of the E14.5 stage, we did not identify any significant dysregulation of genes, neither in the FendrrNull nor in the FendrrBox mutant lungs (Supplementary Figure S1). One explanation could be that those embryos that survived compensated for the mutation with no detectable difference in gene regulation. To circumvent this issue, we collected embryonic lungs from E12.5 stage embryos, before the time point that any lethality occurs and cultivated the lung explants ex vivo under defined conditions. After 5 days of cultivation, some lungs from all phenotypes detached from the supporting membrane. Hence, we chose to analyse 4 day cultivated lungs (corresponding then to E16.5) (Figure 2A). When we compared expression between wild type, FendrrNull and FendrrBox mutant E16.5 ex vivo lungs we found 119 genes deregulated (DE) in FendrrNull and 183 genes in FendrrBox mutant lungs compared to wild type (Figure 2B). When we analysed the GO terms of downregulated genes in both Fendrr mutants we found mainly genes involved in lung and respiratory system development, as well as cell-cell contact organization and extracellular matrix organization (Figure 2C). Upregulated genes in both mutants were mostly associated with genome organization, replication, and genome regulation. Overall, 60 genes were commonly dysregulated in both mutants (Figure 2D) and in both mutants these genes are dysregulated in the same direction (Figure 2E). Moreover, separate analysis of FendrrNull and FendrrBox deregulated genes using the metascape database (27) identified lung fibrosis as a common pathway in both (Figure 2D and Supplementary Figure S2), a major condition of various lung diseases, including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

Figure 2.

Expression profiling of Fendrr mutant lungs in ex vivo development. (A) Representative images from a time course of ex vivo developing lungs from the indicated genotype. The last time point representing E16.5 of embryonic development is the endpoint and lungs were used for expression profiling. (B) Volcano plot representation of deregulated genes in the two Fendrr mutants determined by RNA-seq of two biological replicates. (C) Heatmap of all 242 deregulated genes of both Fendrr mutants compared to wild type. The GO terms of the either up- or downregulated gene clusters are given in the box as determined by clusterProfiler bioconductor package (43). (D) Venn diagram of the individually deregulated genes and the overlap in the two different Fendrr mutants. Pathway analysis performed by wikiPathaways (44) is given for each DE genes cluster. (E) Log2 fold change scatter plot of the 60 DE genes shared between FendrrBox and FendrrNull. The correlation coefficient between the log2 fold change is calculated using Pearson correlation coefficient test. Blue and red indicate that genes are upregulated and downregulated in both mutants, respectively, whereas gray indicates that the genes are changing in either mutant.

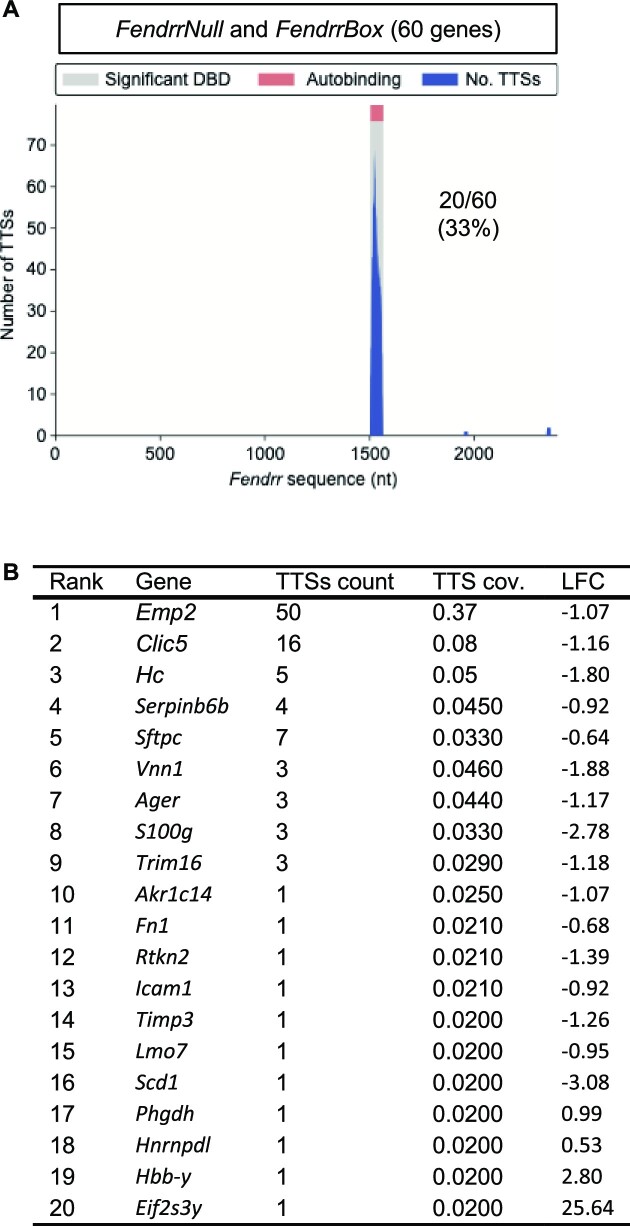

Prediction of Fendrr RNA:DsDNA triplex formation at promoters of DE genes

It is conceivable that some of these dysregulated genes are primary targets of Fendrr and some represent secondary targets. To identify which of these dysregulated genes in Fendrr mutant lungs are likely to be direct targets of Fendrr via its triplex forming FendrrBox, we used the Triplex Domain Finder (TDF) algorithm (20) to identify triplex forming sites on Fendrr within the promoters of the dysregulated target genes. The single significant triplex forming site (or DBD = DNA Binding Domain) discovered by TDF is the FendrrBox (Figures 1A, 3A), confirming previous results (3,29). The TDF algorithm found no significant binding of Fendrr to target promoters in either genes exclusive to FendrrBox or those exclusive to FendrrNull mutant lungs. However, the TDF algorithm detects a significant (p-value 0.0004) FendrrBox binding site in promoters of 20 out of the 60 target genes from the overlapping gene set of FendrrBox and FendrrNull mutants (Figure 3A). We refer to these genes as direct FendrrBox target genes and most of these 20 genes are downregulated in loss of function Fendrr mutants (Figure 3B). When we analysed more closely the GO terms associated with these shared genes, we find most terms to be associated with cell adhesion and extracellular matrix functions, a typical hallmark for fibrosis, where collagen and related components are deposited from cells (Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 3.

Potential direct target genes of Fendrr. (A) Triplexes prediction analysis of the 60 shared dysregulated genes identifies 20 genes with a potential Fendrr triplex interacting site at their promoter. DBD = DNA Binding Domain on RNA, TTS = triple target DNA site. (B) List of the 20 Fendrr target genes that depend on the Fendrr triplex and have a Fendrr binding site at their promoter.

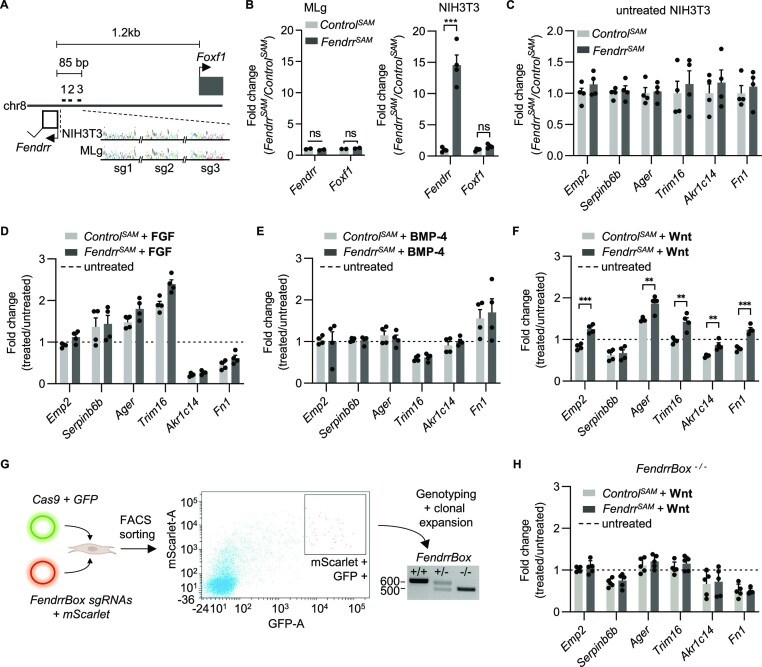

Signalling-dependent regulation by Fendrr

To functionally test for direct Fendrr targets, we wanted to analyse the expression of these 20 genes in fibroblasts. We selected MLg and NIH3T3 cells for further analysis. Only 6 out of these 20 genes are expressed in both cell lines at a level comparable or higher than Foxf1, a previously determined target of Fendrr (Supplementary Figure S3). To activate endogenous Fendrr expression, we tested several gRNAs to recruit the dCAS9-SAM transcriptional activator complex (30) to the promoter region of Fendrr. We identified three gRNAs (Figure 4A) that could exclusively activate endogenous Fendrr without significant activation of the Foxf1 gene (Figure 4B), but only in NIH3T3 cells. In MLg cells Fendrr could not be activated further, possibly due to its already higher expression level compared to NIH3T3 cells. We therefore continued working with NIH3T3 cells, in which specifically the Fendrr gene could be activated to achieve a 15-fold increase in Fendrr transcript. Upon over-activation of endogenous Fendrr, none of the expressed FendrrBox target genes displayed an increase in expression (Figure 4C), as it would be expected as these genes are downregulated in Fendrr loss-of-function mutants (Figure 3B). We speculated that in addition to overexpression of Fendrr, an additional pathway needs to be activated. The BMP, FGF and Wnt pathways are known to play an important role in lung fibrosis (31,32). We therefore activated the BMP, FGF and the Wnt-signalling pathways in these fibroblasts (Figure 4D–F). We found that only when Wnt signalling was activated, overactivation of Fendrr could increase the expression of nearly all the expressed FendrrBox target genes (Figure 4F). To investigate FendrrBox dependence of this effect, we generated NIH3T3 clonal cell lines that harbour the same FendrrBox deletion as the mice. We co-transfected Cas9-GFP and gRNA-mScarlet and sorted single double fluorescent cells (Figure 4G). We generated seven homozygous FendrrBox mutant NIH3T3 cell lines and selected five clonal cell lines that grew with the same characteristics as the parental NIH3T3 cell line. In contrast to the wild type cells, no difference in expression change after the treatment between the control and Fendrr overactivation could be detected in these independent clones (Figure 4H). Hence, Wnt signalling-dependent Fendrr activation requires the FendrrBox element. This places the lncRNA Fendrr as a direct co-activator of Wnt-signalling in fibroblasts to regulate fibrosis-related genes.

Figure 4.

Wnt-dependent Fendrr target gene regulation. (A) Schematic of the Foxf1 and Fendrr promoter region with the indication of the location of the 3 gRNAs used for specific Fendrr endogenous activation. Sanger sequencing of NIH3T3 and MLg genomic DNA verified absence of mutations in gRNA binding sites. (B) Expression changes of Fendrr and Foxf1 after Fendrr CRISPRa (FendrrSAM) in MLg and NIH3T3 cells. Note that only in NIH3T3 cells upregulation of Fendrr could be detected. (C) Fendrr triplex containing Fendrr target genes expressed in NIH3T3 cells after 48 h of FendrrSAM transfection. (D) Expression changes after 48 h of co-stimulation with FGF. (E) Expression changes after 48 h of co-stimulation with BMP-4. (F) Expression changes after 48 h of co-stimulation of Wnt-signalling. (G) Schematic of the generation of NIH3T3 FendrrBox deletion mutants. (H) Expression changes of NIH3T3 FendrrBox deletion mutants upon FendrrSAM and co-stimulation with Wnt. Each dot represents an independent clone. Expression changes after treatment are normalised to untreated cells transfected with control gRNA (set to 1), represented by the dashed line. (D–F, H) Statistics are given when significant by t-test analysis.

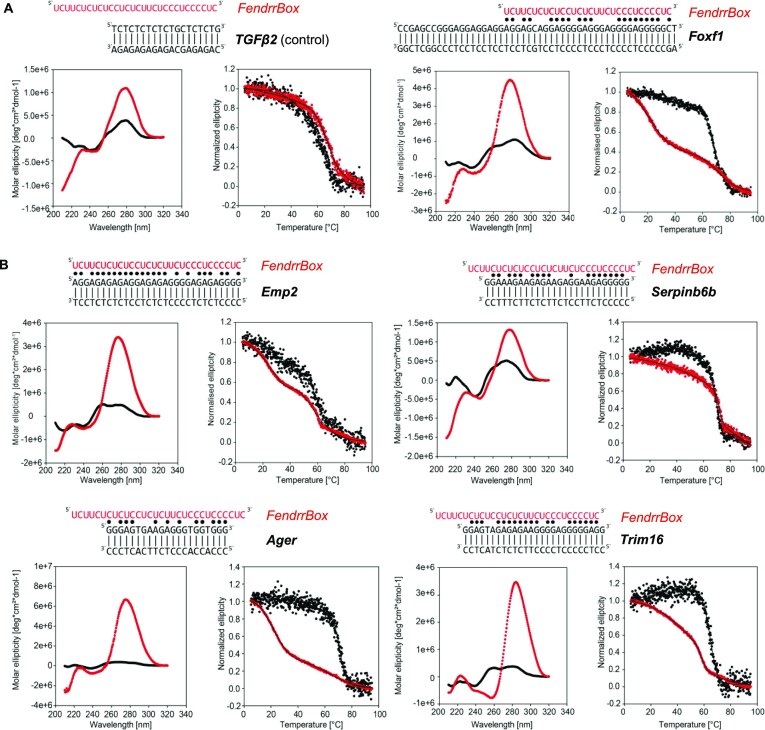

Biophysical RNA:DsDNA triplex characterization

We further wanted to verify that the FendrrBox does form triplexes and used CD spectroscopy and thermal melting analysis to confirm triplex formation on the identified target genes. We incubated an RNA oligonucleotide corresponding to the FendrrBox with dsDNA that was shown previously to form triplexes with RNA. We used the dsDNA element of the TGFβ2 promoter that was shown previously to form a triplex with the lncRNA Meg3 (33) as a negative control for the FendrrBox interaction and Foxf1 as the positive control (29). Both CD spectra presented typical features for interaction including an increased peak at ∼280 nm and a transition at ∼260 nm (Figure 5A). A slight negative peak at ∼240 nm and a positive peak at ∼220 nm (34,35) was only detectable in the presence of the Foxf1 promoter element (Figure 5A). In addition, we performed thermal melting assays to obtain the temperatures for Tm(DNA duplex) and Tm(RNA:dsDNA). While the melting temperature of the dsDNA from the TGFβ2 element was not altered by the addition of the FendrrBox RNA, the presence of the RNA with the Foxf1 triplex binding element dsDNA gave a clear biphasic melting curve. This is a unique feature of the triplex that we were able to characterize, which results from the dissociation of the weaker Hoogsteen base pairs at the first melting point, followed by the melting of the Watson-Crick base pairs at the higher melting transition (Figure 5A, right). We investigated all potential triplex binding elements in the promoters of direct target genes analysed before and found clear peaks at ∼220 nm (Figure 5B and Supplementary Figure S4). Together with the presence of the clear shift of the Tm(RNA:dsDNA) over the Tm(DNA duplex), this demonstrates that the FendrrBox can form indeed triplexes with the previously identified target genes.

Figure 5.

Fendrr RNA:dsDNA triplex formation capacity with target genes. Circular dichroism (CD) spectra (left graph) and Thermal melting (TM) (right graph) of the FendrrBox RNA with the target dsDNA elements (in red) and the dsDNAs alone (in black). RNA sequence and DNA sequences used are indicated. Watson–Crick base pairing is indicated with | and the Hoogsteen base pairing is indicated with •. (A) CD spectra and TM curves of a negative (TGFβ2) and a positive (Foxf1) DNA promoter region measured at 298 K. Triplex is indicated by strong negative peak in CD around 210–240 nm and two melting points in TM curve. (B) The four target genes Emp2, Serpin6b, Ager and Trim16 exhibit triplex formation in CD and in the TM analysis.

DISCUSSION

We showed previously that Fendrr can bind to promoters of target genes in the lateral plate mesoderm of the developing mouse embryo (3,29). As Fendrr can also bind to histone modifying complexes, it is assumed that Fendrr directs these complexes to its target genes. However, that the FendrrBox might be the recruiting element was so far only supported by a biochemical approach that showed binding of the FendrrBox RNA element to two target promoters in vitro (3).

The involvement of Fendrr in lung formation was shown previously, albeit with a completely different approach to the removal of Fendrr. The replacement of the full length Fendrr locus by a lacZ coding sequence resulted in homozygous postnatal mice to stop breathing within 5 h after birth (7). These mice also allowed for tracing Fendrr expression to the pulmonary mesenchyme, to which also vascular endothelial cells and fibroblasts belong. At the E14.5 stage FendrrLacZ mutant mice exhibited hypoplastic lungs. Our ex vivo analysis of lungs from our specific Fendrr mutants confirmed the involvement of Fendrr in lung development. Here we showed for the first time that the FendrrBox is at least partially required for in vivo functions of Fendrr and identified several, potential direct target genes of Fendrr in lung development. Moreover, the analysis of the dysregulated genes in the two different mouse mutant lungs indicates, that specifically Fendrr in the fibroblast might play an important role.

Studying embryonic development of the lung and its comparison to idiopathic lung fibrosis (IPF) in the adult lung has revealed that many of the same gene networks are in place to regulate both processes (36). A multitude of different signalling pathway are implicated in IPF (32). A prime example for an important pathway in IPF is the Wnt signalling pathway (37) and, in particular, increased Wnt signalling is associated with IPF and, hence, inhibition of Wnt signalling counteracts fibrosis (38). While the contribution of developmental signalling pathways to IPF is well understood, the contribution of lncRNAs in IPF is just beginning to be addressed (39). In humans, it was shown that in IPF patients FENDRR is reduced in lung tissue (11). Intriguingly, in single cell RNA-seq approaches from human lung explants, FENDRR is highly expressed in vascular endothelial (VE) cells, but also significantly expressed in fibroblasts (40). Moreover, FENDRR expression increases in both VE cells and fibroblasts in IPF (40,41). It was shown recently, that Fendrr can regulate β-catenin levels in lung fibroblasts (42). Our data support that Wnt signalling together with Fendrr is involved in target gene regulation and that Fendrr is a positive co-regulator of Wnt signalling in fibroblasts. This is in contrasts to the role of Fendrr in the precursor cells of the heart, the lateral plate mesoderm. Loss of Fendrr function results in the upregulation of Fendrr target genes, establishing that Fendrr is a suppressor of gene expression. The fact that Fendrr can exhibit opposite effects on transcription, as either a suppressor or an activator, depending on the cell type, demonstrates the intricate interactions between lncRNAs and signalling pathways, providing deeper insight into the multifaceted roles of lncRNA in cellular functions.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data are deposited to GEO and can be downloaded under the accession number GSE186703.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dijana Micic for excellent animal husbandry and Karol Macura for the generation of the transgenic mice. We want to thank Heiner Schrewe for help with ex vivo culture of embryonic lungs. We thank Saverio Bellusci and Stefano Rivetti for providing the MLg cells. The graphical abstract was created using BioRender.com.

Notes

Present address: Maria-Theodora Melissari, Department of Physiology, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens 11527, Greece.

Contributor Information

Tamer Ali, Institute of Cardiovascular Regeneration, Centre for Molecular Medicine, Goethe University, Theodor-Stern-Kai 7, 60590, Frankfurt am Main, Hesse, Germany; Faculty of Science, Benha University, Benha, 13518, Egypt; Georg-Speyer-Haus, Paul-Ehrlich-Str. 42-44, 60596, Frankfurt am Main, Hesse, Germany.

Sandra Rogala, Institute of Cardiovascular Regeneration, Centre for Molecular Medicine, Goethe University, Theodor-Stern-Kai 7, 60590, Frankfurt am Main, Hesse, Germany; Georg-Speyer-Haus, Paul-Ehrlich-Str. 42-44, 60596, Frankfurt am Main, Hesse, Germany.

Nina M Krause, Center for Biomolecular Magnetic Resonance (BMRZ), Institute for Organic Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Goethe University, Max-von-Laue-Str. 7, 60438, Frankfurt am Main, Hesse, Germany.

Jasleen Kaur Bains, Center for Biomolecular Magnetic Resonance (BMRZ), Institute for Organic Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Goethe University, Max-von-Laue-Str. 7, 60438, Frankfurt am Main, Hesse, Germany.

Maria-Theodora Melissari, Institute of Cardiovascular Regeneration, Centre for Molecular Medicine, Goethe University, Theodor-Stern-Kai 7, 60590, Frankfurt am Main, Hesse, Germany.

Sandra Währisch, Department of Developmental Genetics, Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics, Ihnestr. 63-73, 14195, Berlin, Germany.

Harald Schwalbe, Center for Biomolecular Magnetic Resonance (BMRZ), Institute for Organic Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Goethe University, Max-von-Laue-Str. 7, 60438, Frankfurt am Main, Hesse, Germany.

Bernhard G Herrmann, Department of Developmental Genetics, Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics, Ihnestr. 63-73, 14195, Berlin, Germany.

Phillip Grote, Institute of Cardiovascular Regeneration, Centre for Molecular Medicine, Goethe University, Theodor-Stern-Kai 7, 60590, Frankfurt am Main, Hesse, Germany; Georg-Speyer-Haus, Paul-Ehrlich-Str. 42-44, 60596, Frankfurt am Main, Hesse, Germany.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

DFG (German Research Foundation) Excellence Cluster Cardio-Pulmonary System [Exc147-2]; DFG research [GR 4745/1-1 to P.G. supported M.-T.M.]; T.A., S.R., N.K. J.K.B., H.S. and P.G. are supported by the 403584255 – TRR 267 of the DFG. Funding for open access charge: DFG. Part of this work was supported by the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft. The work at BMRZ is supported by the state of Hesse.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ali T., Grote P.. Beyond the RNA-dependent function of LncRNA genes. eLife. 2020; 9:e60583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hon C.C., Ramilowski J.A., Harshbarger J., Bertin N., Rackham O.J., Gough J., Denisenko E., Schmeier S., Poulsen T.M., Severin J.et al.. An atlas of human long non-coding rnas with accurate 5' ends. Nature. 2017; 543:199–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grote P., Wittler L., Hendrix D., Koch F., Wahrisch S., Beisaw A., Macura K., Blass G., Kellis M., Werber M.et al.. The tissue-specific lncRNA Fendrr is an essential regulator of heart and body wall development in the mouse. Dev. Cell. 2013; 24:206–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mahlapuu M., Ormestad M., Enerback S., Carlsson P.. The forkhead transcription factor Foxf1 is required for differentiation of extra-embryonic and lateral plate mesoderm. Development. 2001; 128:155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yu S., Shao L., Kilbride H., Zwick D.L.. Haploinsufficiencies of FOXF1 and FOXC2 genes associated with lethal alveolar capillary dysplasia and congenital heart disease. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2010; 152A:1257–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Herriges M.J., Swarr D.T., Morley M.P., Rathi K.S., Peng T., Stewart K.M., Morrisey E.E.. Long noncoding RNAs are spatially correlated with transcription factors and regulate lung development. Genes Dev. 2014; 28:1363–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sauvageau M., Goff L.A., Lodato S., Bonev B., Groff A.F., Gerhardinger C., Sanchez-Gomez D.B., Hacisuleyman E., Li E., Spence M.et al.. Multiple knockout mouse models reveal lincRNAs are required for life and brain development. eLife. 2013; 2:e01749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stankiewicz P., Sen P., Bhatt S.S., Storer M., Xia Z., Bejjani B.A., Ou Z., Wiszniewska J., Driscoll D.J., Maisenbacher M.K.et al.. Genomic and genic deletions of the FOX gene cluster on 16q24.1 and inactivating mutations of FOXF1 cause alveolar capillary dysplasia and other malformations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009; 84:780–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Szafranski P., Dharmadhikari A.V., Brosens E., Gurha P., Kolodziejska K.E., Zhishuo O., Dittwald P., Majewski T., Mohan K.N., Chen B.et al.. Small noncoding differentially methylated copy-number variants, including lncRNA genes, cause a lethal lung developmental disorder. Genome Res. 2013; 23:23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gong L., Zhu L., Yang T.. Fendrr involves in the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis via regulating miR-106b/SMAD3 axis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020; 524:169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huang C., Liang Y., Zeng X., Yang X., Xu D., Gou X., Sathiaseelan R., Senavirathna L.K., Wang P., Liu L.. Long noncoding RNA FENDRR exhibits antifibrotic activity in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2020; 62:440–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., Perez J.L., Perez Marc G., Moreira E.D., Zerbini C.et al.. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020; 383:2603–2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Melissari M.T., Grote P.. Roles for long non-coding RNAs in physiology and disease. Pflugers Arch. 2016; 468:945–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li Y., Syed J., Sugiyama H.. RNA-DNA triplex formation by long noncoding RNAs. Cell Chem. Biol. 2016; 23:1325–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Choi J., Huebner A.J., Clement K., Walsh R.M., Savol A., Lin K., Gu H., Di Stefano B., Brumbaugh J., Kim S.Y.et al.. Prolonged Mek1/2 suppression impairs the developmental potential of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2017; 548:219–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Concordet J.P., Haeussler M.. CRISPOR: intuitive guide selection for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing experiments and screens. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:W242–W245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hogan B., Hogan B.. Manipulating the Mouse Embryo : A Laboratory Manual. 1994; 2nd edn.Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- 18. George S.H., Gertsenstein M., Vintersten K., Korets-Smith E., Murphy J., Stevens M.E., Haigh J.J., Nagy A.. Developmental and adult phenotyping directly from mutant embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007; 104:4455–4460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Muller P.Y., Janovjak H., Miserez A.R., Dobbie Z.. Processing of gene expression data generated by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. BioTechniques. 2002; 32:1372–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kuo C.C., Hanzelmann S., Senturk Cetin N., Frank S., Zajzon B., Derks J.P., Akhade V.S., Ahuja G., Kanduri C., Grummt I.et al.. Detection of RNA-DNA binding sites in long noncoding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kalwa M., Hanzelmann S., Otto S., Kuo C.C., Franzen J., Joussen S., Fernandez-Rebollo E., Rath B., Koch C., Hofmann A.et al.. The lncRNA HOTAIR impacts on mesenchymal stem cells via triple helix formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:10631–10643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dobin A., Davis C.A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., Batut P., Chaisson M., Gingeras T.R.. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013; 29:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zerbino D.R., Achuthan P., Akanni W., Amode M.R., Barrell D., Bhai J., Billis K., Cummins C., Gall A., Giron C.G.et al.. Ensembl 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:D754–D761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lawrence M., Huber W., Pages H., Aboyoun P., Carlson M., Gentleman R., Morgan M.T., Carey V.J.. Software for computing and annotating genomic ranges. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013; 9:e1003118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S.. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014; 15:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Raudvere U., Kolberg L., Kuzmin I., Arak T., Adler P., Peterson H., Vilo J.. g:profiler: a web server for functional enrichment analysis and conversions of gene lists (2019 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:W191–W198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhou Y., Zhou B., Pache L., Chang M., Khodabakhshi A.H., Tanaseichuk O., Benner C., Chanda S.K.. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019; 10:1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xiao J.H., Hao Q.Y., Wang K., Paul J., Wang Y.X.. Emerging role of MicroRNAs and long noncoding RNAs in healthy and diseased lung. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017; 967:343–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Grote P., Herrmann B.G.. The long non-coding RNA Fendrr links epigenetic control mechanisms to gene regulatory networks in mammalian embryogenesis. RNA Biol. 2013; 10:1579–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Konermann S., Brigham M.D., Trevino A.E., Joung J., Abudayyeh O.O., Barcena C., Hsu P.D., Habib N., Gootenberg J.S., Nishimasu H.et al.. Genome-scale transcriptional activation by an engineered CRISPR-Cas9 complex. Nature. 2015; 517:583–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cassandras M., Wang C., Kathiriya J., Tsukui T., Matatia P., Matthay M., Wolters P., Molofsky A., Sheppard D., Chapman H.et al.. Gli1+ mesenchymal stromal cells form a pathological niche to promote airway progenitor metaplasia in the fibrotic lung. Nat. Cell Biol. 2020; 22:1295–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hosseinzadeh A., Javad-Moosavi S.A., Reiter R.J., Hemati K., Ghaznavi H., Mehrzadi S.. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) signaling pathways and protective roles of melatonin. Life Sci. 2018; 201:17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mondal T., Subhash S., Vaid R., Enroth S., Uday S., Reinius B., Mitra S., Mohammed A., James A.R., Hoberg E.et al.. MEG3 long noncoding RNA regulates the TGF-β pathway genes through formation of RNA-DNA triplex structures. Nat. Commun. 2015; 6:7743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Manzini G., Xodo L.E., Gasparotto D., Quadrifoglio F., van der Marel G.A., van Boom J.H.. Triple helix formation by oligopurine-oligopyrimidine DNA fragments. Electrophoretic and thermodynamic behavior. J. Mol. Biol. 1990; 213:833–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Scaria P.V., Will S., Levenson C., Shafer R.H.. Physicochemical studies of the d(G3T4G3)*d(G3A4G3).d(C3T4C3) triple helix. J. Biol. Chem. 1995; 270:7295–7303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shi W., Xu J., Warburton D.. Development, repair and fibrosis: what is common and why it matters. Proc. Congr. Asian Pac. Soc. Respirol., 7th. 2009; 14:656–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Baarsma H.A., Konigshoff M.. WNT-er is coming’: WNT signalling in chronic lung diseases. Thorax. 2017; 72:746–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cao H., Wang C., Chen X., Hou J., Xiang Z., Shen Y., Han X.. Inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling suppresses myofibroblast differentiation of lung resident mesenchymal stem cells and pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2018; 8:13644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hadjicharalambous M.R., Lindsay M.A.. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: pathogenesis and the emerging role of long non-coding RNAs. Int J Mol Sci. 2020; 21:524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Adams T.S., Schupp J.C., Poli S., Ayaub E.A., Neumark N., Ahangari F., Chu S.G., Raby B.A., DeIuliis G., Januszyk M.et al.. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals ectopic and aberrant lung-resident cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Adv. 2020; 6:eaba1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Morse C., Tabib T., Sembrat J., Buschur K.L., Bittar H.T., Valenzi E., Jiang Y., Kass D.J., Gibson K., Chen W.et al.. Proliferating SPP1/MERTK-expressing macrophages in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2019; 54:1802441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Senavirathna L.K., Liang Y., Huang C., Yang X., Bamunuarachchi G., Xu D., Dang Q., Sivasami P., Vaddadi K., Munteanu M.C.et al.. Long noncoding RNA FENDRR inhibits lung fibroblast proliferation via a reduction of beta-catenin. Int.J. Mol. Sci. 2021; 22:8536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wu T., Hu E., Xu S., Chen M., Guo P., Dai Z., Feng T., Zhou L., Tang W., Zhan L.et al.. clusterProfiler 4.0: a universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation (N Y). 2021; 2:100141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Martens M., Ammar A., Riutta A., Waagmeester A., Slenter D.N., Hanspers K., R A.M., Digles D., Lopes E.N., Ehrhart F.et al.. WikiPathways: connecting communities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021; 49:D613–D621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data are deposited to GEO and can be downloaded under the accession number GSE186703.