Abstract

Sporadic evidence exists for burnout interventions in terms of types, dosage, duration, and assessment of burnout among clinical nurses. This study aimed to evaluate burnout interventions for clinical nurses. Seven English databases and two Korean databases were searched to retrieve intervention studies on burnout and its dimensions between 2011 and 2020.check Thirty articles were included in the systematic review, 24 of them for meta-analysis. Face-to-face mindfulness group intervention was the most common intervention approach. When burnout was measured as a single concept, interventions were found to alleviate burnout when measured by the ProQoL (n = 8, standardized mean difference [SMD] = − 0.654, confidence interval [CI] = − 1.584, 0.277, p < 0.01, I2 = 94.8%) and the MBI (n = 5, SMD = − 0.707, CI = − 1.829, 0.414, p < 0.01, I2 = 87.5%). The meta-analysis of 11 articles that viewed burnout as three dimensions revealed that interventions could reduce emotional exhaustion (SMD = − 0.752, CI = − 1.044, − 0.460, p < 0.01, I2 = 68.3%) and depersonalization (SMD = − 0.822, CI = − 1.088, − 0.557, p < 0.01, I2 = 60.0%) but could not improve low personal accomplishment. Clinical nurses' burnout can be alleviated through interventions. Evidence supported reducing emotional exhaustion and depersonalization but did not support low personal accomplishment.

Subject terms: Health services, Occupational health, Health care

Introduction

Burnout, first described by Freudenberger1, is a negative condition characterized by the gradual depletion of physical, emotional, and mental energy due to excessive work2. Maslach (1976) later conceptualized burnout as a multidimensional syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and diminished personal commitment3. Burnout occurs during the maintenance of interpersonal relationships and is most prevalent in the fields of nursing, medicine, and education, which deal directly with many people3.

Nursing is an occupation that experiences one of the highest rates of burnout4. Nurse burnout is defined as a physical, psychological, emotional, and socially exhausted status caused by unsuccessfully managed job stress and limited social support5. The globally pooled prevalence of nurse burnout is 11.2%6. However, in other studies classifying burnout symptoms, nurse burnout was as high as 40.0%7,8. Moreover, nurse burnout in the post-COVID-19 pandemic era has worsened. In a recent study, nurse burnout was as high as 68.0%9.

The factors that contribute to burnout are diverse and intricate. Occupational stress is the most influential factor10. The causes of nurse burnout were excessive workload; lack of staffing; role conflict; low autonomy; time pressure; interpersonal conflict between patients, guardians, and medical staff; and absence of leadership support11. Burnout can have a significant impact on the group and the organization, so prevention and action are required2. The impact of nurse burnout is significant in that it not only negatively influences nurses but also patients and healthcare organizations5. Nurse burnout is associated with low-quality care, a threat to patient safety12, medication error13, and an extended patient hospital stay14. Nurses who experience burnout have physical symptoms, such as headache, fatigue, hypertension, and musculoskeletal problems5, and psychological symptoms, such as depression, sleep disorders, and difficulty concentrating15. Exhausted nurses may also experience behavioral disorders that negatively affect their health, such as smoking and drinking alcohol5. Nurse burnout might lead to the turnover16 and a subsequent burden to healthcare organizations11.

Nurse burnout has been a frequently investigated topic owing to its high prevalence and detrimental impact. However, systematic reviews and meta-analysis studies were focused on the description of the nurse burnout phenomenon such as the prevalence of nurse burnout7, burnout level and risk factors17, and burnout-related factors in nurses18. Previous systematic reviews or meta-analysis studies that evaluated the effects of burnout programs were limited to mindfulness training19 and coping strategies20. However, various programs, such as yoga, communication skills, stress management, mindfulness, meditation, and cognitive behavioral therapy, were implemented independently or in combination, and the level of evidence varied21,22. Nurse burnout interventions should be evaluated inclusively to understand their current effectiveness in reducing burnout among nurses. Previously conducted systematic reviews and meta-analyses on burnout interventions inclusively evaluated health professionals, which included nurses and medical doctors as participants22,23. However, nurses and medical doctors have different job descriptions24 and different patterns of burnout25. Accordingly, to retrieve evidence for nurse burnout programs, the analysis should be refined to interventions specifically designed and implemented for nurses.

Furthermore, burnout has been measured in many ways. Burnout could be measured as a single concept26–28, though it is often measured as three dimensions based on the International Classification of Disease-11 (ICD-11). The most frequently used measure is the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), which lists three areas of burnout: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment23,29. Some studies used the total score of the MBI and others used the three areas of burnout with some variations30,31. To be inclusive, burnout interventions should be evaluated by including studies that used burnout as a single concept and as three dimensions. Per this understanding, we aimed to analyze burnout interventions for clinical nurses.

Methods

Design

This study is a systematic review and meta-analysis study on the effects of burnout reduction programs for clinical nurses. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline32.

Eligibility criteria

We used the PICO-SD (Population, Interventions, Comparison, Outcome—Study Design) framework to organize our research question: What is the effect of an intervention on reducing burnout among clinical nurses? Detailed information regarding the eligibility criteria is described in Table 1. We selected articles published between 2011 and 2020 to yield results that reflected the reality of burnout intervention effects.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Registered Nurses or Licensed Practice/Vocational Nurses providing direct care to their patients in hospitals | Studies with nurses who did not provide care independently or worked at outpatient clinics |

| Interventions | Any type of program that aimed to reduce nurse burnout | |

| Comparison | Inactive control group that did not receive an intervention or received usual care, or an active control group that received an alternative intervention for burnout | Studies without comparison groups |

| Outcome | Burnout | Studies that did not provide information on intervention results such as mean or standard deviation |

| Study Designs | Randomized controlled trial or quasi-experimental study | All other methodological studies |

| Language | English or Korean | Studies that did not provide original content |

Search strategies

Nine search engines were utilized: seven global search engines in English (PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Scopus, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses (PQDT) Global, EBSCO, and Cochrane Library) and two domestic search engines in Korean (RISS, KISS). The search terms were “nurse*” and “burnout” and a combination of (Nurses OR nurse* OR registered nurse* OR healthcare provider* OR nursing staff OR healthcare worker* OR health care provider* OR health care worker* OR health personnel* OR health professional*) AND (burnout OR burn-out OR burn out) AND (treatment* OR intervention* OR program* OR therapy OR training OR exercise* OR practice* OR mindfulness OR meditation OR massage OR yoga).

Study selection and data extraction

Endnote 20.0 was used to manage retrieved studies and screen the redundant ones. After retrieval of the studies, titles and abstracts were reviewed to remove irrelevant studies. A full-text review of the studies was conducted afterward. Throughout the process, we worked independently and met weekly to discuss the process and select the studies.

Risk-of-bias assessment

To evaluate the risk of bias, we used the Cochrane’s Risk of Bias 2.0 (RoB 2.0) for the randomized controlled trials and Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (RoBINS-I) for the quasi-experimental studies. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. In addition, a funnel plot was utilized to evaluate the possibility of publication bias.

Data synthesis and meta-analysis

For the systematic review, tables were used to classify article contents for descriptive analyses. For the meta-analysis, the R-4.1.1 program for Windows was used. In 16 articles, burnout was measured as a single concept using various instruments, while in 11 articles, burnout was measured as three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment. Meta-analysis was conducted with the fixed effect model and the random effect model with 95% confidence interval, pooled mean differences, and weight of each article for each meta-analysis. The heterogeneity of the articles was calculated using the I2 index. This research was exempted after review by the institutional review board at the institution of the principal investigator.

Results

Study selection

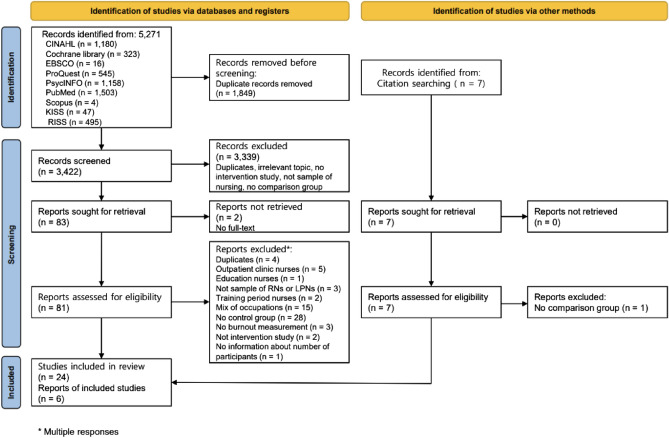

We retrieved 5271 articles from the initial search. After reviewing the title and abstract, 5188 were excluded (duplicates, no intervention study, no comparison group, not target population). During the full-text review, 59 articles were excluded (no full-text, duplicates, no intervention study, no comparison group, not target population). Through reference check, six articles were included. Finally, 30 articles were included in our final analysis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of studies and interventions are described in Table 2. Of the 30 articles, 12 were randomized controlled trials26,28,33–42 and 18 were quasi-experimental studies27,30,31,43–57. Nineteen studies were conducted in Asia (Korea = 14, China = 3, India = 1, and Japan = 1). The types of publication were journals (n = 26) and thesis (n = 4). Participants were mostly women, with the female gender ranging from 71.9 to 100%. The age range of the participants was 24–46 years. There were between 21 and 296 participants, for a total of 1935, with 975 in the experimental group and 960 in the control group.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Author, year (Country) |

Design | Risk of bias | Participants (Number, female ratio) |

Mean age of participants | Measures | Intervention (Type, duration, mode, comparison) |

Follow-up (f/u) time points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ahn (2017)37 (Korea) |

Quasi-experimental | Moderate |

E = 15, C = 15 100% |

N/A | MBI |

Type: mindfulness-based stress reduction program Duration: 5 weeks Mode: face to face, group Comparison: waitlist |

Pre, post |

|

Alenezi et al. (2019)38 (Saudi) |

Quasi-experimental | Moderate |

E = 154, C = 142 N/A |

N/A | MBI |

Type: burnout prevention workshop Duration: 2 days Mode: face to face, group Comparison: no information about intervention |

Pre, f/u (1, 3, 6 months) |

|

Alexander et al. (2015)27 (USA) |

RCT | Some concerns |

E = 20, C = 20 97.5% |

46.4 | MBI |

Type: yoga Duration: 8 weeks Mode: face to face, group Comparison: usual care |

Pre, post |

|

Bae et al. (2019)39 (Korea) |

Quasi-experimental | Moderate |

E = 17, C = 17 91.2% |

31.7 | MBI |

Type: mindfulness-based stress reduction program Duration: 4 weeks Mode: face to face, group Comparison: waitlist |

Pre, post, f/u (4 weeks) |

|

Bagheri et al. (2019)25 (Iran) |

Quasi-experimental | No Information |

E = 30, C = 30 88.1% |

33.2 | MBI |

Type: stress-coping & cognitive behavioral therapy Duration: 10 weeks Mode: face to face, group Comparison: no information about intervention |

Pre, post, f/u (1 month) |

|

Berger et al. (2011)28 (Israel) |

RCT | Some concerns |

E = 42, C = 38 100% |

E = 49.3 C = 47.7 | ProQoL |

Type: reducing secondary traumatization Duration: 12 weeks Mode: face to face, group Comparison: waitlist |

Pre, post |

|

Choi et al. (2016)40 (Korea) |

Quasi-experimental | Moderate |

E = 34, C = 15 N/A |

E = 24.0 C = 25.4 | Pines, Aronson, Kafry (1981) |

Type: empowerment program Duration: 2 days Mode: face to face, group Comparison: waitlist |

Pre, post |

|

Dincer et al. (2021)21 (Turkey) |

RCT | Some concerns |

E = 35, 91.4% C = 37, 86.5% |

E = 33.5 C = 33.4 | Pines & Aronson (1988) |

Type: emotional freedom techniques Duration: 20 min Mode: face to face, group Comparison: waitlist |

Pre, post |

|

Duarte et al. (2016)41 (Portugal) |

Quasi-experimental | High |

E = 29, 89.6% C = 19, 84.2% |

E = 38.9 C = 42.1 | ProQoL |

Type: mindfulness-based stress reduction program Duration: 6 weeks Mode: face to face, group Comparison: waitlist |

Pre, post |

|

Felker. (2013)42 (USA) |

Quasi-experimental | Moderate |

E = 17, C = 17 94.1% |

40.3 | MBI |

Type: yoga Duration: 6 weeks Mode: face to face, group Comparison: waitlist |

Pre, post |

|

Jang (2019)43 (Korea) |

Quasi-experimental | Moderate |

E = 24, 75.0% C = 24, 87.5% |

E = 26.1 C = 25.8 | MBI |

Type: workplace mutual respect program Duration: 4 months Mode: face to face, group Comparison: no information about intervention |

Pre, post |

|

Jang et al. (2015)26 (Korea) |

Quasi-experimental | Moderate |

E = 14, C = 15 100% |

N/A | MBI |

Type: group art therapy Duration: 8 weeks Mode: face to face, group Comparison: no information about intervention |

Pre, post, f/u (4 weeks) |

|

Kang et al. (2017)44 (Korea) |

Quasi-experimental | Moderate |

E = 15, C = 23 N/A |

E = 27.9 C = 26.6 | ProQoL |

Type: self-reflection program Duration: 6 weeks Mode: face to face, group Comparison: no information about intervention |

Pre, post |

| Kharatzadeh et al. (2020)29 (Iran) | RCT | Some concerns |

E = 26, 92.3% C = 27, 88.8% |

E = 41.0 C = 39.2 | ProQoL |

Type: emotional regulation training Duration: six 2-h sessions Mode: N/A Comparison: waitlist |

Pre, post |

|

Kil et al. (2016)30 (Korea) |

RCT | Some concerns |

E = 26, C = 30 100% |

N/A | MBI |

Type: self-cosmetology training program Duration: 3 weeks Mode: face to face, group Comparison: no information about intervention |

Pre, post |

|

Kim et al. (2016)45 (Korea) |

Quasi-experimental | Moderate |

E = 14, C = 18 71.9% |

26.9 | ProQoL |

Type: overcoming compassion fatigue program Duration: 5 weeks Mode: face to face, group Comparison: waitlist |

Pre, post |

|

Kim et al. (2018)22 (Korea) |

Quasi-experimental | Moderate |

E = 23, 100% C = 24, 91.7% |

N/A | OLBI |

Type: group rational emotive behavior therapy program with group counseling Duration: 8 weeks Mode: face to face, group Comparison: no information about intervention |

Pre, post, f/u (4 weeks) |

|

Kubota et al. (2016)31 (Japan) |

RCT | Some concerns |

E = 50, 96.0% C = 46, 96.0% |

E = 38.9 C = 40.0 | MBI |

Type: psycho-oncology training program Duration: 16 h (2 days) Mode: face to face, group Comparison: waitlist |

Pre, f/u (3 months) |

|

Lee et al. (2017)46 (Korea) |

Quasi-experimental | Moderate |

E = 18, C = 18 N/A |

30.6 | MBI |

Type: violence coping program Duration: 4 weeks Mode: face to face, group Comparison: waitlist |

Pre, post, f/u (4 weeks) |

|

Luo et al. (2019)47 (China) |

Quasi-experimental | High |

E = 41, C = 46 97.7% |

28.1 | MBI |

Type: record 3 good things Duration: 4 weeks Mode: mobile application Comparison: no information about intervention |

Pre, post |

|

Özbaş et al. (2016)32 (Turkey) |

RCT | Some concerns |

E = 38, C = 44 N/A |

N/A | MBI |

Type: psychodrama-based psychological empowerment program Duration: 10 weeks Mode: face to face, group Comparison: waitlist |

Pre, f/u (1 month after intervention), f/u (3 month after intervention) |

|

Rajeswari et al. (2020)23 (India) |

RCT | Some concerns |

E = 60, C = 60 80.0% |

N/A | ProQoL |

Type: accelerated recovery program Duration: 5 weeks Mode: N/A Comparison: routine activity |

Pre, post, f/u (3, 6, 9, 12 months) |

|

Redhead et al. (2011)33 (England) |

RCT | Some concerns |

E = 12, 83.0% C = 9, 78.0% |

E = 39.4 C = 42.6 | MBI |

Type: psychosocial intervention training Duration: 8 months Mode: face to face, group Comparison: waitlist |

Pre, post |

|

Rhee et al. (2012)48 (Korea) |

Quasi-experimental | Moderate |

E = 13, C = 15 100% |

E = 43.8 C = 41.5 | MBI |

Type: mindfulness-based stress reduction program Duration: 4 weeks Mode: face to face, group Comparison: no information about intervention |

Pre, post |

| Sabancıogullari et al. (2015)49 (Turkey) | Quasi-experimental | Moderate |

E = 33, 97.2% C = 30, 93.3% |

E = 27.5 C = 29.6 | MBI |

Type: professional identity awareness development education program Duration: 10 weeks Mode: face to face, group Comparison: no information about intervention |

Pre, post, f/u (6 months) |

|

Shin et al. (2020)34 (Korea) |

RCT | Some concerns |

E = 25, C = 25 100% |

E = 26.4 C = 26.6 | ProQoL |

Type: Patchouli oil inhalation Duration: 24 h Mode: N/A Comparison: pure sweet almond oil inhalation |

Pre, post |

|

Wei et al. (2017)35 (China) |

RCT | Some concerns |

E = 51, C = 51 86.0% |

N/A | MBI |

Type: active intervention and regular management Duration: 6 months Mode: N/A Comparison: regular management |

Pre, post |

|

Xie et al. (2020)36 (China) |

RCT | Some concerns |

E = 53, C = 53 100.0% |

27.7 | MBI |

Type: mindfulness Duration: 8 weeks Mode: face to face, group Comparison: education |

Pre, post, f/u (1, 3 months) |

|

Yoo (2017)50 (Korea) |

Quasi-experimental | Moderate |

E = 21, 90.5% C = 27, 96.3% |

E = 26.1 C = 26.5 | ProQoL |

Type: expressive writing program Duration: 5 weeks Mode: non-face-to-face, individual Comparison: no information about intervention |

Pre, post |

|

Yoon (2013)51 (Korea) |

Quasi-experimental | Moderate |

E = 25, C = 25 N/A |

N/A | MBI |

Type: happy arts therapy Duration: 4 weeks Mode: face to face, group Comparison: no information about intervention |

Pre, post |

C comparison group, E experimental group, MBI Maslach Burnout Inventory scale, OLBI Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, ProQoL Professional Quality of Life Scale, RCT Randomized controlled trial, N/A not available.

The most common interventions provided for burnout reduction were mindfulness-based stress reduction programs (n = 5) and face-to-face group format (n = 24). The duration of the intervention varied from one day to eight months. In most studies, control groups involved the waitlist group (n = 12) rather than an active control group. MBI (n = 19), ProQoL (n = 8) and others (n = 3) were the instruments used to measure burnout. Burnout was most often measured twice, before the intervention and immediately post-intervention. In three studies37,38,44, burnout was measured at baseline and follow-up only, not immediately post-intervention.

Risk-of-bias

Risk-of-bias is described in Table 2. In general, the level of risk of bias for 12 randomized controlled trials was “some concern.” The level of risk of bias for the 18 quasi-experimental studies was “low risk of bias” for 15 studies, “moderate risk of bias” for two studies, and non-assessable due to limited information for one study.

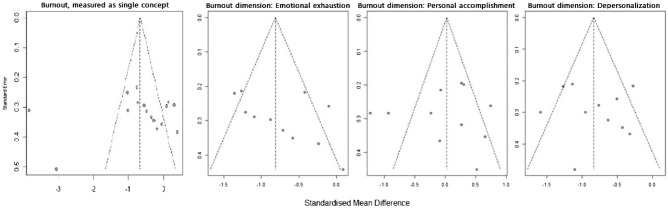

The risk of publication bias was evaluated using a funnel plot (Fig. 2). The plot is symmetrical when publication bias is at minimum58. Studies with a small sample size were on the lower side, while those with a large sample size were on the opposite side. The small number of articles used in our study was a risk factor because it could affect the precision of the results. Among 30 articles, three articles37,38,44 that did not conduct a post-test were excluded for meta-analysis. Sixteen articles measured burnout as a single concept26–28,31,34,35,40,45–47,49–52,54,56 and 11 measured burnout as three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment30,33,36,39,41–43,48,53,55,57. There was one outlier among articles that measured burnout as a single concept.

Figure 2.

Funnel plots.

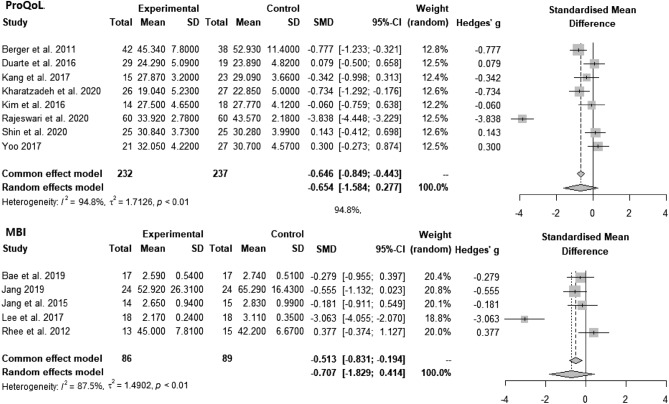

Meta-analysis

Instruments that measured burnout as a single concept were ProQoL (n = 8), MBI (n = 5), burnout questionnaire (n = 2), and OLBI (n = 1). Meta-analysis of articles that used ProQoL and MBI are described in Fig. 3. For the articles that used ProQoL, the pooled analysis showed that intervention could statistically alleviate burnout (SMD = − 0.654, CI = − 1.584, 0.277, p < 0.01, I2 = 94.8%). For the articles that used the MBI, the pooled analysis showed that intervention could statistically alleviate burnout (SMD = − 0.707, CI = − 1.829, 0.414, p < 0.01, I2 = 87.5%).

Figure 3.

Forest plots: Effect of interventions on burnout measured by ProQoL and MBI.

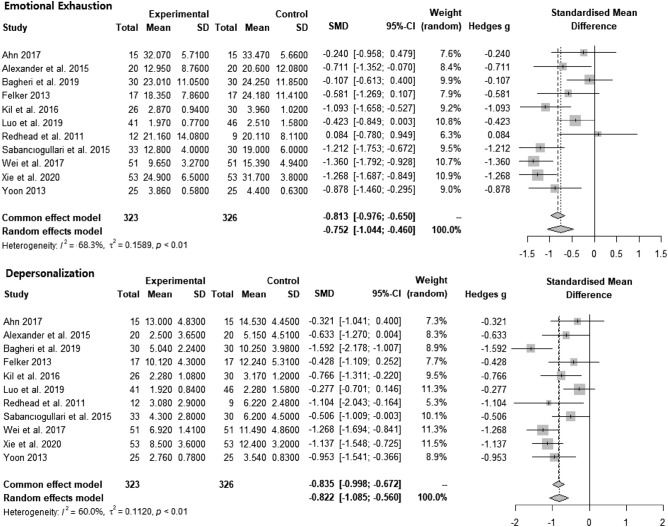

The meta-analysis of burnout interventions as three dimensions (n = 11) is described in Fig. 4. The pooled analysis showed that interventions could statistically significantly reduce emotional exhaustion (SMD = − 0.752, CI = − 1.044, − 0.460, p < 0.01, I2 = 68.3%) and depersonalization (SMD = − 0.822, CI = − 1.085, − 0.560, p < 0.01, I2 = 60.0%). For improving low personal accomplishment, the pooled analysis result was not statistically significant.

Figure 4.

Forest plots: effect of intervention on emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we analyzed 30 and 24 articles, respectively. Among 30 articles, more than half (n = 19) were published in Asia. Although nurse burnout is a global phenomenon, the prevalence of nurse burnout studies conducted in Asia might indicate the significance of the issue of nurse burnout in Asian countries. This notion is supported by a recent meta-analysis study on the global prevalence of nurse burnout, which reported that Southeast Asia and the Pacific region had a significantly higher prevalence of nurse burnout among si× global regions6. In Asia, nurses encounter poor working conditions such as low nurse patient ratios59 and a rapidly aging population. High prevalence of nurse burnout in Asian countries might have drawn the nurse administrators and nursing scholars to research on nurse burnout interventions.

Our systematic review revealed that a mindfulness-based program was the most frequently used intervention for nurse burnout. Meta-analysis studies19 have shown that mindfulness-based programs are effective in reducing nurse burnout. However, burnout refers to a state of physical, mental, and social exhaustion that may require various interventions. A systematic review of health professional burnout programs revealed that a vast array of interventions have been adopted alone or in combination24. Although mindfulness-based programs are helpful in lowering burnout level, their role might be limited to managing burnout rather than preventing or managing situations for burnout60. In many cases, the causes of burnout are multifaceted, which include but are not limited to issues with limited manpower, working longer shifts, not having schedule flexibility, and responding to high work and psychological demands11. Systematic support to improve work environments and tailored programs to train nurses to prevent repeated situations are needed.

All articles were appraised for risk of bias. The most concerning realm for risk of bias in both the randomized controlled trials and quasi-experimental studies was bias in the measurement of outcomes that were appraised as “some concern” or “moderate risk of bias.” As burnout is a subjective concept, all the interventions used a self-reported survey to measure the outcome, leading to a moderate risk of bias. To overcome this, biological indicators for burnout could be utilized. However, we would like to note that people are experts in their own feelings and psychological health. In measuring psychological concepts such as burnout, the concept of risk of bias should be re-assessed.

In our meta-analysis of articles that measured burnout as a single concept with ProQoL and MBI, the results favored intervention. Similarly, results of previous meta-analyses of various burnout interventions provided to health professionals reported that burnout could be reduced23. In this study, the authors argued that various factors, such as coping strategies, emotional regulation skills, and resilience, were enhanced through diverse burnout interventions and bridged health professionals’ burnout to wellness. Likewise, various programs could be utilized solitarily or in combination to reduce nurse burnout.

When burnout was measured as three dimensions, emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were lowered, leaving no evidence for increasing low personal accomplishment. In contrast, a recent meta-analysis study on burnout intervention for primary healthcare professionals reported that interventions had beneficial effects on all three dimensions of burnout, including low personal accomplishment61. In the previous meta-analysis study, 78.5% of the participants were physicians, while only 20.1% were nurses. This was one of the most significant differences between the studies. The nature of the profession in achieving personal accomplishment may explain the differences in intervention effect on low personal accomplishment. Personal accomplishment for nurses may be more closely tied to a workplace system. For instance, a study that measured personal accomplishment found that it was positively correlated with aspects of the workplace such as control, community, fairness, and values62. In accordance with this argument, a meta-analysis that examined the long-term effect of burnout intervention on nurses found that improvement in low personal accomplishment lasted only six months, whereas improvement in emotional exhaustion and depersonalization lasted a year20. The authors of this study also explained that low personal accomplishment is difficult to change in the long term because it is reliant on the work environment. Another possible reason for the burnout intervention not favoring low personal accomplishment might be owing to the contents of the intervention focusing on problem-solving skills, such as stress reduction, coping with the problem, and empowering the participants, which are helpful for emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.

Implications for future research are suggested as follows. This study revealed that the majority of burnout interventions for clinical nurses were delivered as face-to-face group programs, which could be challenging to implement during a pandemic such as COVID-19. Combining online and offline burnout programs may be an option for reducing the risk of infection. Despite the fact that clinical nurses benefit from burnout programs, they may require consistent support and feedback to continue the program63. Continual active feedback may be necessary for the implementation and maintenance of the burnout program for clinical nurses. A number of scholars view burnout as three dimensions in line with the ICD-11 definition of burnout and meta-analysis studies on the prevalence and risk factors for burnout explained burnout as three dimensions6,64, meaning there is ample evidence on the dimensions of burnout. However, when examining the effect of burnout interventions, burnout is often measured as a single concept. Burnout interventions should be designed to target all three areas. Additionally, more time and effort might be needed to promote personal accomplishment.

Limitations

In this study, we focused on nurses providing direct care in hospitals, excluding those who worked in outpatient clinics. Thus, our findings are limited to clinical nurses. The articles’ language was limited to English and Korean, half of which were in Korean. In addition, we limited our search to the past 10 years to reflect the reality of the burnout intervention effect, which may have caused selection bias. When the risk of bias was appraised, we identified some concerns, including moderate concerns. In addition, articles analyzed in this study used different instruments to measure burnout. We acknowledge the heterogeneity of the data, which is assumed by meta-analysis study. Thus, readers of this article should be aware of the risk of bias in the results and heterogeneity of the articles in instruments. The protocol of this systematic review and meta-analysis was not registered.

Conclusions

Thirty articles were included in the systematic review and 24 in the meta-analysis. Most of the evidence for nurse burnout was based on face-to-face group programs, which could be transformed into a virtual space in the post-COVID-19 era. Pooled analysis suggested that interventions could reduce burnout when measured as a single concept and reduce the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization dimensions of burnout. However, we could not find evidence for burnout interventions effectively promoting personal accomplishment.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence interval

- ICD-11

International Classification of Disease-11

- MBI

Maslach Burnout Inventory

- N/A

Not available

- OLBI

Oldenburg Burnout Inventory

- ProQoL

Professional Quality of Life Scale

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- SMD

Standardized mean difference

Author contributions

C.C. envisioned the systematic review and drafted the manuscript. C.C. and M.L. are involved in data search and assessing articles for eligibility and the risk of bias. C.C. and M.L. read and approved the final version of the manuscript. C.C. and M.L. wrote the manuscript together (M.L. was mainly in charge of the background and discussion and C.C. was mainly involved in the method and discussion). All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2021R1A2C2008166).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the IRB restriction but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Freudenberger HJ. Staff burn-out. J. Soc. Issues. 1974;30(1):159–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb00706.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stamm, B. H. The Concise ProQOL Manual. In Pocatello: ProQOL.org (2010).

- 3.Maslach C. Burned-out. Hum. Behav. 1976;5(9):16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim SH, Yang YS. A Meta analysis of variables related to Burnout of nurse in Korea. J. Dig. Converg. 2015;13(8):387–400. doi: 10.14400/JDC.2015.13.8.387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nabizadeh-Gharghozar Z, Adib-Hajbaghery M, Bolandianbafghi S. Nurses' job burnout: A hybrid concept analysis. J. Caring Sci. 2020;9(3):154–161. doi: 10.34172/jcs.2020.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woo T, Ho R, Tang A, Tam W. Global prevalence of burnout symptoms among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;123:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pradas-Hernández L, et al. Prevalence of burnout in paediatric nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(4):e0195039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramirez-Baena L, et al. A multicentre study of burnout prevalence and related psychological variables in medical area hospital nurses. J. Clin. Med. 2019;8(1):92. doi: 10.3390/jcm8010092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruyneel A, Smith P, Tack J, Pirson M. Prevalence of burnout risk and factors associated with burnout risk among ICU nurses during the COVID-19 outbreak in French speaking Belgium. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2021;65:103059. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgantini LA, et al. Factors contributing to healthcare professional burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid turnaround global survey. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(9):e0238217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dall'Ora C, Ball J, Reinius M, Griffiths P. Burnout in nursing: A theoretical review. Hum. Resour. Health. 2020;18(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s12960-020-00469-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salyers MP, et al. The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: A meta-analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2017;32(4):475–482. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montgomery AP, et al. Nurse burnout predicts self-reported medication administration errors in acute care hospitals. J. Healthc. Qual. 2021;43(1):13–23. doi: 10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nantsupawat A, Nantsupawat R, Kunaviktikul W, Turale S, Poghosyan L. Nurse burnout, nurse-reported quality of care, and patient outcomes in Thai hospitals. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2016;48(1):83–90. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudman A, Arborelius L, Dahlgren A, Finnes A, Gustavsson P. Consequences of early career nurse burnout: A prospective long-term follow-up on cognitive functions, depressive symptoms, and insomnia. EClinical Med. 2020;27:100565. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashrafi Z, Ebrahimi H, Khosravi A, Navidian A, Ghajar A. The relationship between quality of work life and burnout: A linear regression structural-equation modeling. Health Scope. 2018;7(1):e68266. doi: 10.5812/jhealthscope.68266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molina-Praena J, et al. Levels of burnout and risk factors in medical area nurses: A meta-analytic study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15(12):2800. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15122800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deldar K, Froutan R, Dalvand S, Gheshlagh RG, Mazloum SR. The relationship between resiliency and burnout in Iranian nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Access Maced J. Med. Sci. 2018;6(11):2250–2256. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2018.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suleiman-Martos N, et al. The effect of mindfulness training on burnout syndrome in nursing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020;76(5):1124–1140. doi: 10.1111/jan.14318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee HF, Kuo CC, Chien TW, Wang YR. A meta-analysis of the effects of coping strategies on reducing nurse burnout. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2016;31:100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de-Oliveira SM, de-Alcantara-Sousa LV, Vieira-Gadelha MDS, do-Nascimento VB. Prevention actions of burnout syndrome in nurses: An integrating literature review. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health. 2019;15:64–73. doi: 10.2174/1745017901915010064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aryankhesal A, et al. Interventions on reducing burnout in physicians and nurses: A systematic review. Med. J. Islam Repub. Iran. 2019;33:77. doi: 10.34171/mjiri.33.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang XJ, Song Y, Jiang T, Ding N, Shi TY. Interventions to reduce burnout of physicians and nurses: An overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Medicine. 2020;99(26):e20992. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Leary KJ, Sehgal NL, Terrell G, Williams MV, High Performance Teams and the Hospital of the Future Project Tea Interdisciplinary teamwork in hospitals: A review and practical recommendations for improvement. J. Hosp. Med. 2012;7(1):48–54. doi: 10.1002/jhm.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dubale BW, et al. Systematic review of burnout among healthcare providers in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–20. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7566-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dincer B, Inangil D. The effect of emotional freedom techniques on nurses' stress, anxiety, and burnout levels during the COVID-19 pandemic: A randomized controlled trial. Explore. 2021;17(2):109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2020.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim HR, Yoon SH. Effects of group rational emotive behavior therapy on the nurses’ job stress, burnout, job satisfaction, organizational commitment and turnover intention. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2018;48(4):432–442. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2018.48.4.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajeswari H, Sreelekha BK, Nappinai S, Subrahmanyam U, Rajeswari V. Impact of accelerated recovery program on compassion fatigue among nurses in South India. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2020;25(3):249. doi: 10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_218_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory, Manual. 3. Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bagheri T, Fatemi MJ, Payandan H, Skandari A, Momeni M. The effects of stress-coping strategies and group cognitive-behavioral therapy on nurse burnout. Ann. Burns Fire Disasters. 2019;32(3):184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jang OJ, Ryu UJ, Song HJ. The effects of a group art therapy on job stress and burnout among clinical nurses in oncology units. J. Korean Clin. Nurs. Res. 2015;21(3):366–376. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Page MJ, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021;88:105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexander GK, Rollins K, Walker D, Wong L, Pennings J. Yoga for self-care and burnout prevention among nurses. Workplace Health Saf. 2015;63(10):462–470. doi: 10.1177/2165079915596102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berger R, Gelkopf M. An intervention for reducing secondary traumatization and improving professional self-efficacy in well baby clinic nurses following war and terror: A random control group trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011;48(5):601–610. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kharatzadeh H, Alavi M, Mohammadi A, Visentin D, Cleary M. Emotional regulation training for intensive and critical care nurses. Nurs. Health Sci. 2020;22(2):445–453. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kil KH, Song YS. Effects on psychological health of nurses in tertiary hospitals by applying a self-cosmetology training program. J. Korean Soc. Cosm. 2016;22(6):1444–1453. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kubota Y, et al. Effectiveness of a psycho-oncology training program for oncology nurses: A randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2016;25(6):712–718. doi: 10.1002/pon.4000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Özbaş AA, Tel H. The effect of a psychological empowerment program based on psychodrama on empowerment perception and burnout levels in oncology nurses: Psychological empowerment in oncology nurses. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14(4):393–401. doi: 10.1017/S1478951515001121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Redhead K, Bradshaw T, Braynion P, Doyle M. An evaluation of the outcomes of psychosocial intervention training for qualified and unqualified nursing staff working in a low-secure mental health unit. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2011;18(1):59–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin YK, Lee SY, Lee JM, Kang P, Seol GH. Effects of short-term inhalation of patchouli oil on professional quality of life and stress levels in emergency nurses: A randomized controlled trial. J. Altern. Complement Med. 2020;26(11):1032–1038. doi: 10.1089/acm.2020.0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei, R., Ji, H., Li, J. & Zhang, L. Active intervention can decrease burnout in ED nurses. J. Emerg. Nurs.43 (2), 145–149 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Xie C, et al. Educational intervention versus mindfulness-based intervention for ICU nurses with occupational burnout: A parallel, controlled trial. Complement Ther. Med. 2020;52:102485. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahn, M. N. The effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction program on nurse's stress, burnout, sleep and happiness. Master’s thesis, Eulji University (Daejeon, 2017).

- 44.Alenezi A, McAndrew S, Fallon P. Burning out physical and emotional fatigue: Evaluating the effects of a programme aimed at reducing burnout among mental health nurses. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019;28(5):1045–1055. doi: 10.1111/inm.12608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bae HJ, Eun Y. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction program for small and medium sized hospital nurses. Korean J. Stress Res. 2019;27(4):455–463. doi: 10.17547/kjsr.2019.27.4.455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi KH, Kwon S, Hong M. The effect of an empowerment program for advanced beginner hospital nurses. J. Korean Data Anal. Soc. 2016;18(2):1079–1092. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duarte J, Pinto-Gouveia J. Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based intervention on oncology nurses’ burnout and compassion fatigue symptoms: A non-randomized study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016;64:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Felker, A. J. An Examination of yoga as a stress reduction intervention for nurses. Doctoral dissertation, Walden University (Minnesota, 2013).

- 49.Jang, Y. M. Development and evaluation of nurse's workplace mutual respect program, Doctoral dissertation, Eulji University (Daejeon, 2019).

- 50.Kang HJ, Bang KS. Development and evaluation of a self-reflection program for intensive care unit nurses who have experienced the death of pediatric patients. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2017;47(3):392–405. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2017.47.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim YA, Park JS. Development and application of an overcoming compassion fatigue program for emergency nurses. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2016;46(2):260–270. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2016.46.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee SM, Sung KM. The effects of violence coping program based on middle-range theory of resilience on emergency room nurses' resilience, violence coping, nursing competency and burnout. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2017;47(3):332–344. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2017.47.3.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luo YH, et al. An evaluation of a positive psychological intervention to reduce burnout among nurses. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2019;33(6):186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2019.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rhee JS, Kim SH, Lee WK, Shin JG. The effects of MBSR(Mindfulness based stress reduction) program on burnout of psychiatric nurses: Pilot study. J. Korean Assoc. Soc. Psychiatry. 2012;17(1):25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sabancıogullari S, Dogan S. Effects of the professional identity development programme on the professional identity, job satisfaction and burnout levels of nurses: A pilot study. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2015;21(6):847–857. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoo, D. Effect of an expressive writing program on professional quality of life and resilience of intensive care unit nurses. In Master’s thesis, Cha University (Gyeonggi, 2017).

- 57.Yoon HS. Effects of the happy arts therapy program to psychological well-being and emotional exhaust in nurse practitioners. Off. J. Korean Soc. Dance Sci. 2013;29(29):53–74. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Field AP, Gillett R. How to do a meta-analysis. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2010;63(3):665–694. doi: 10.1348/000711010X502733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Drennan VM, Ross F. Global nurse shortages: The facts, the impact and action for change. Br. Med. Bull. 2019;130(1):25–37. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldz014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Green AA, Kinchen EV. The effects of mindfulness meditation on stress and burnout in nurses. J. Holist. Nurs. 2021;39(4):356–368. doi: 10.1177/08980101211015818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Salvado M, Marques DL, Pires IM, Silva NM. Mindfulness-based interventions to reduce burnout in primary healthcare professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerl.) 2021;9(10):1342. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9101342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Whittington KD, Shaw T, McKinnies RC, Collins SK. Promoting personal accomplishment to decrease nurse burnout. Nurse Lead. 2021;19(4):416–420. doi: 10.1016/j.mnl.2020.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu X, Hayter M, Lee AJ, Zhang Y. Nurses' experiences of the effects of mindfulness training: A narrative review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Nurse Educ. Today. 2021;100:104830. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Galanis P, Vraka I, Fragkou D, Bilali A, Kaitelidou D. Nurses' burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021;77(8):3286–3302. doi: 10.1111/jan.14839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the IRB restriction but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.