Abstract

Introduction

Spondyloarthritis (SpA) is a serious chronic inflammatory rheumatism implying different painful and crippling symptoms that require a multidisciplinary approach for the patient. Fatigue is one of the less well treated symptoms, even if its repercussion on everyday life is noticeable. Shiatsu is a Japanese preventive and well-being therapy that aims to promote better health. However, the effectiveness of shiatsu in SpA-associated fatigue has never been studied yet in a randomized study.

Methods and Analysis

We describe the design of SFASPA (Etude pilote randomisée en cross-over évaluant l’efficacité du Shiatsu sur la FAtigue des patients atteints de SPondyloarthrite Axiale), a single-center, randomized controlled cross-over trial with allocation of patients according to a ratio (1:1) evaluating the effectiveness of shiatsu in SpA-associated fatigue. The sponsor is the Regional Hospital of Orleans, France. The two groups of 60 patients each will receive three “active” shiatsu and three sham shiatsu treatments (120 patients, 720 shiatsu). The wash-out period between the active and the sham shiatsu treatments is 4 months.

Planned Outcomes

The primary outcome is the percentage of patients responding to the FACIT-fatigue score. A response to fatigue is defined as an improvement, i.e., an increase of ≥ 4 points in the FACIT-fatigue score, which corresponds to the “minimum clinically important difference” (MCID).

Differences in the evolution of activity and impact of the SpA will be assessed on several secondary outcomes. An important aim of this study is also to gather material for further trials with higher proof of evidence.

Trial Registration

NCT05433168, date of registration, June 21st, 2022 (clinicaltrials.gov).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40744-023-00558-w.

Keywords: Spondyloarthritis, Fatigue, Shiatsu, Cross-over, Randomized controlled trial

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Among non-pharmacological treatments for the various symptoms associated with SpA, shiatsu is increasingly used and available. |

| Fatigue and back pain are among the most common and disabling symptoms for patients living with SpA. Targeted therapies mostly focus on treating inflammation-mediated symptoms. Conversely, shiatsu can address multiple symptoms including pain but also fatigue and sleep disturbance. |

| We therefore considered that it was a relevant task to evaluate its efficacy on fatigue in a SpA population. The present study is the first randomized study evaluating shiatsu treatment in order to reduce the fatigue associated with SpA. |

Introduction

Spondyloarthritis (SpA) is a potentially serious disease with reduced life expectancy [1, 2]. Even if the clinical presentation is eminently variable from one patient to another, the most frequently encountered manifestations such as inflammatory spinal pain, peripheral arthritis, or even extra-articular involvement of the disease all represent disabling symptoms, pain, temporary or in some cases permanent functional incapacity [3]. The disease also has general repercussions on daily life (fatigue, reactive depressive syndrome, etc.) [4] which require a multidisciplinary approach, involving several medical, paramedical, and other stakeholders.

Up to 50–65% of patients report suffering from fatigue [5]. However, little is known about the precise relationship between axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) and fatigue [6]. Although post hoc analyses have shown an improvement in pain provided by TNFi or IL-17A inhibitors [7–10], to date, no specific treatment targets fatigue in axSpA and thus, lacking a full explanation of the mechanisms underlying axSpA-associated fatigue, using a non-pharmacological intervention could be appropriate.

Shiatsu (finger pressure in Japanese) is an energetic manual discipline addressing the individual as a whole. It is a preventive and well-being therapy that aims to promote better health and is part of personal assistance. Shiatsu therapy is given with the patient dressed in soft clothes. Its objective is to correct both the energy flow (ki, blood, lymph, etc.) and the body structure (muscles, tendons, etc.) by applying rhythmic pressure to the whole body, most often with the thumbs. It can be applied to everyone at all ages. Its principle of action is to restore the free flow of Ki (qi, Energy) in the body and bodily flexibility. Shiatsu is a set of pressures performed mainly with the thumbs and the palms of the hands on different areas of the body, often the points of acupuncture meridians.

The effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions and in particular the care provided by shiatsu practitioners have not been the subject of studies evaluating, according to the criteria of evidence-based medicine, the benefit of this practice, particularly in the context of the treatment of axSpA.

In this study, we report the design of a preliminary trial to examine the impact of shiatsu on fatigue in patients with axSpA, as we suspected that shiatsu may result in alleviating the fatigue associated with axSpA.

Methods and Analysis

Study Design

SFASPA (Etude pilote randomisée en cross-over évaluant l’efficacité du Shiatsu sur la FAtigue des patients atteints de SPondyloarthrite Axiale) is a single-center randomized controlled cross-over trial with allocation of patients according to a ratio (1:1). The sponsor is the Regional Hospital of Orleans (CHRO), France. The trial is partially funded by the Shiatsu Professionals Syndicate (SPS) to remunerate shiatsu practitioners’ interventions. We followed the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Intervention Trials (SPIRIT) [11].

All patients included undergo shiatsu treatments given by a professional shiatsu practitioner according to the shiatsu protocol developed and validated by the SPS’s evaluation commission Shiatsu Professionals. Patients are randomized to receive either the shiatsu protocol or the sham shiatsu with a cross-over design.

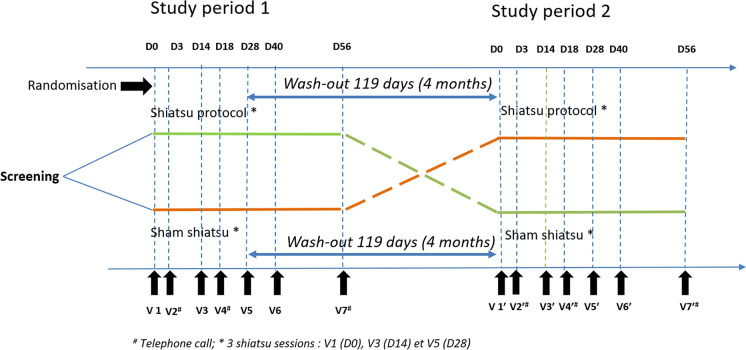

Each patient is scheduled for a visit at baseline and at following visits as indicated in Fig. 1. At each visit, patients complete questionnaires and undergo a clinical examination for efficacy and safety assessments, as specified in Table 1. All participants will be followed for up to 50 weeks.

Fig. 1.

Study design

Table 1.

Schedule of enrolment, interventions, and assessments of the SFASPA trial according to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) 2013 guidelines

| Visit name | V0 pre-screening | Study period 1 | Study period 2 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 | V6 | V7 | V1’ | V2’ | V3’ | V4’ | V5’ | V6’ | V7’ | ||

| Visit number | D0 | D3 | D14 | D18 | D28 | D40 | D56 | D0 | D3 | D14 | D18 | D28 | D40 | D56 | |

| Days | 0 | 3 ± 2 | 14 ± 2 | 18 ± 2 | 28 ± 2 | 40 ± 5 | 56 ± 2 | 147 ± 2 | 150 ± 2 | 161 ± 2 | 165 ± 2 | 175 ± 2 | 187 ± 5 | 203 ± 2 | |

| Enrolment | |||||||||||||||

| Review of inclusion/exclusion criteria | × | × | |||||||||||||

| Informed consent document signed | × | ||||||||||||||

| Randomization | × | ||||||||||||||

| Medical history and significant historical diagnosis | × | ||||||||||||||

| Physical examination | × | × | × | × | |||||||||||

| Assessment | |||||||||||||||

| BASMI | × | × | × | × | |||||||||||

| BASDAI | × | × a | × | × a | × | × | × a | × | × a | × | × a | × | × | × a | |

| VAS pain | × | × | × | x | × | × | x | × | × | × | X | × | × | × | |

| BASFI | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||

| SF-12 | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||

| ASQoL | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||

| ASAS HI | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||

| WPAI | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||

| HAD | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||

| PSQI | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||

| FACIT-F | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||

| Adverse events | × | × | |||||||||||||

| Interventions | |||||||||||||||

| Shiatsu sessionsb | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||||

| Follow-up telephone call | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||||

The italics is a precision on when the patient will receive their 3 shiatsu sessions. It is made this way to lighten the graphic

a1st BASDAI question

bShiatsu protocol or sham shiatsu

Study Participants

Patients are recruited during either outpatient visits or hospitalization in the Orleans Rheumatology Department. They are informed about the two phases of the protocol including the sham shiatsu phase. The investigator or subinvestigator confirms the selection criteria (patients with a visual analogue or numeric verbal rating scale ≥ 3 in the BASDAI (Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index) fatigue question) and then proposes the trial to the patients. If the patient agrees to participate, an inclusion visit is planned.

The inclusion visit is conducted by a medical doctor and includes checking inclusion and non-inclusion criteria, verifying that the patient has given informed written consent, conducting a physical examination, and completing questionnaires assessing the activity and impact of axSpA.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study includes patients aged ≥ 18 years to 70 years with symptomatic axSpA fulfilling the ASAS (Assessment in SpondyloArthritis international Society) criteria, followed in the Rheumatology Department of the Orleans regional hospital center and having a fatigue index ≥ 3 using the BASDAI fatigue question. Patients must give informed written consent and must be affiliated with a social security scheme. The exclusion criteria are the following: patient with a pathology that contraindicates the practice of shiatsu (evolving infectious skin pathology that would make shiatsu treatment difficult), previous shiatsu treatment, inability to attend appointments for the duration of the study, pregnant or breastfeeding woman, refusal to participate in the study or to sign the consent, patients not affiliated with or not beneficiaries of a social security scheme, person under guardianship or curatorship, patient with an uncontrolled epileptic or psychotic condition which, in the opinion of the investigator, would interfere with the smooth running of the study.

Randomization

Eligible patients who consent to participate will be randomized according to the following procedure. The allocation ratio will be 1:1, with permutation blocks whose size will be unknown to the investigators. A randomization list will be drawn up beforehand by the CHRO research department (or by the study statistician), by the permutation of blocks whose size will remain unknown to the investigators.

Each time a patient is included, the investigating doctor or a person delegated by him/her will deliver the envelope with the lowest order number, in the batch corresponding to the patient’s situation. In the envelope it will be indicated whether the patient will receive shiatsu or not (and in the latter case, will therefore be part of the sham shiatsu group). Only the shiatsu specialist will open the sealed envelope. He or she is the only one who knows if the patient will receive shiatsu or sham shiatsu. During the second phase of the study (cross-over), the patients who had the shiatsu in the first phase will receive a sham shiatsu, while the patients who had a sham shiatsu will have the shiatsu sessions in the second phase. The signed envelopes will be kept for verification of the randomization by the persons mandated to carry out the monitoring of the study.

The investigator or his/her delegate will note in the patient file the randomization arm assigned by the draw and the list of randomized patients will be recorded in a table provided for this purpose (list of patients participating in the study).

Interventions

The trial intervention is shiatsu treatment by a professional shiatsu practitioner according to the shiatsu protocol developed and validated by the SPS. The usual care of patients will not be modified, and management of the patients enrolled in this study will be modeled on the usually recommended management. The shiatsu protocol was developed by the SPS (see the appendix in the electronic supplementary material for details). This protocol was intended to be global: it was developed ad hoc for SpA and is not a fragment of a historical protocol as in the context of fundamental research at the shiatsu Research Lab.

Exercising a sham shiatsu is a challenging task. However, the consensus of the different schools and styles is that shiatsu pressure is a weight transfer. Therefore, we removed this aspect for the sham SFASPA shiatsu protocol. For sham shiatsu, the professional will run the same sequence of points, without any weight transfer, being only in contact with the receiver. Shiatsu and sham shiatsu sessions will have the same duration. Three shiatsu practitioners are involved in this study and for a given patient the same shiatsu professional will be required during both the shiatsu and the sham shiatsu sessions. In order to ensure that the shiatsu protocols are reproducible, the shiatsu professionals will exclusively carry out the shiatsu protocol established for this study. The three shiatsu professional practitioners were trained before the trial during a 1-day session by an experienced professional shiatsu practitioner (Bernardinelli N.).

Outcomes

Primary Outcome Measure

The primary outcome is the percentage of patients responding to the FACIT-fatigue (Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Fatigue Scale) score. The FACIT fatigue score is a short, easy-to-administer, 13-item tool that measures a person’s level of fatigue during their usual daily activities over the past week. The level of fatigue is measured on a four-point Likert scale (4 = not at all tired to 0 = very tired). A response to fatigue will be defined as an improvement (i.e., an increase of ≥ 4 points in the FACIT-fatigue score), which corresponds to the Minimum Clinically Important Difference [12].

The percentages of responders after a shiatsu intervention (three sessions) versus a sham (sham) shiatsu intervention (three sessions) (control group) will be assessed.

Secondary Outcomes

Differences in the evolution of activity and impact of the SpA will be assessed on several secondary outcomes listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Secondary assessments of the SFASPA study

| BASMI | Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index |

| BASDAI | Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index |

| VAS pain | Visual analog scale for pain |

| BASFI | Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index |

| SF-12 | The Short Form (12) Health Survey |

| ASQoL | Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| ASAS HI | The Assessment in Spondyloarthritis international Society (ASAS) Health Index Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire |

| WPAI | Work |

| HAD | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| PSQI | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

Assessment of pain (VAS, pain visual analogue scale for pain) is a graduated ruler ranging from 0 to 10 (0 = no pain; 10 = maximum imaginable pain). The BASDAI is a questionnaire to calculate the activity index of ankylosing spondylitis [13]. The intensity of five symptoms during the past week will be estimated, giving a score from 0 to 10. The BASFI (Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index) questionnaire that was developed specifically to assess joint mobility in SpA. The BASFI reflects the functional impact, that is to say the inability to perform actions of daily life. For each of the ten activities, you must rate from 0 to 10 the ease or difficulty of performing them during the past month. 0 means completely easy, 10 means impossible. This score is an aid in monitoring ankylosing spondylitis. SF-36 Health Questionnaire (The Short-Form) is a self-assessment quality of life scale comprising 11 questions. ASQoL Questionnaire (Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life Questionnaire) is composed of 18 double-choice (yes/no) items. All the points obtained are added together and divided by the maximum possible total [14]. ASAS Health Index (Health Index in Spondyloarthritis), this self-assessment questionnaire measures functioning and health across 17 aspects of health and nine environmental factors in patients with SpA [15]. The ASAS HI contains items covering the following categories: pain, emotional functions, sleep, sexual functions, mobility, autonomy, and community life. The WPAI scale (Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire), this is a self-administered questionnaire where the assessment is based on the patient's absenteeism, presence and difficulties in carrying out work or outside activities [15]. The HAD Scale (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) is an instrument used to screen for anxiety and depressive disorders. It comprises 14 items rated from 0 to 3. Seven questions relate to anxiety (total A) and seven others to the depressive dimension (total D), thus allowing two scores to be obtained (maximum score for each score = 21) [16]. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) is used to assess the sleep quality of subjects over the past month. The 17 scoring items in this study were combined into six components: sleep quality, time to fall asleep, sleep time, sleep efficiency, sleep disorder, and daytime dysfunction [17]. The BASMI (Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index) measurement index allows to evaluate the mobility of the spine. It is composed of five items including: cervical rotation, tragus wall distance, lateral flexion of the spine, lumbar flexion, and inter malleolar distance. The score for each item is added together to result in a rating out of 10 [18].

Post-Intervention Assessments

The post-intervention assessments took place at visit 6 (V5 ± 5 to 10 days) with completion of questionnaires by the patient (BASDAI, VAS, BASFI, SF-36, ASQoL, HAD, ASAS HI, WPAI, HAD, PSQI and FACIT-fatigue), physical examination, evaluation of the BASMI by the medical doctor and collection of serious adverse events.

Assessment of Safety

Due to the nature of the intervention (shiatsu or sham shiatsu), no particular vigilance linked to the research protocol is required. However, all unfavorable or unintended events affecting patients in the study will be recorded and followed up for the duration of the study or until resolution.

Blinding

Patients will undergo shiatsu sessions without knowing whether they will receive the shiatsu or the sham shiatsu treatment. Investigators, clinical nurses, and clinical research assistants will be blinded to the order in which patients will have shiatsu or sham shiatsu during the study. Then the end-point (FACIT-fatigue assessment) will be collected by a medical doctor blinded to the type of shiatsu protocol received by the patients.

Sample Size

Our primary study hypothesis is that shiatsu treatment should achieve a greater reduction in the fatigue associated with SpA compared to sham shiatsu treatment. A study [19] using the FACIT scale in SPA patients found baseline means between 25 ± 5.5 and 35 ± 11. The sample size needed to find a four-point delta in FACIT means between pre- and post-treatment groups (i.e., enough to indicate a significantly different proportion of responding subjects) at first risk of 5% and power of 80% in bilateral approach is 98 [20].

To allow for a loss to follow-up and other deviations from the protocol of 15 to 20%, a minimum sample size of 120 patients at baseline was required.

Data Analysis

Analysis will be performed at the end of the study after a blind data review and database lock. A flowchart will be drawn up in accordance with the SPIRIT statement. Concerning descriptive statistics, qualitative data will be presented as number and percentage of patients with 95% confidence interval, in each treatment group. Quantitative data will be presented by mean and standard deviation and for each arm. The absence of imbalance between the groups will be checked on the structure variables.

Primary analysis will be performed on the intent-to-treat (ITT) population defined as all patients randomized.

For the primary outcome, the comparison of the responder rate between the groups will use Fisher’s exact test.

Analyses for the secondary outcomes are as follows:

For the quantitative indicators, the means will be compared by a mixed intra-subject model for repeated measures in order to compare the mean values of the score or the indicator between the two groups, while distinguishing the specific effects of the treatment modality (shiatsu versus sham shiatsu), of the sequence of administration, the period of measurement, and the subject.

For the qualitative indicators, the comparison of the two groups, the numbers will be compared by Fisher’s exact test.

A correlation analysis between the clinical response and fatigue measurements will be conducted taking into account the following parameters:

Change in WPAI from the start of the study,

VAS,

Total intensity of spinal pain (2nd question of the BASDAI),

Mental component score (MCS) of the Short Form (SF-12),

Physical component score (PCS) of the Short Form (SF-12).

All statistical tests will be performed using a 5% type 1, two-sided error rate.

Patient and Public Involvement

Patients were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting of this research. However, SPS is involved in the design of the research as well as the co-authors. SPS as well as the authors will participate in the dissemination of the results to SpA patient organizations.

Discussion

Among non-pharmacological treatments for the various symptoms associated with SpA, shiatsu is increasingly used and available. We therefore considered that it was a relevant task to evaluate its efficacy on fatigue in a SpA population. The present study is the first randomized study evaluating shiatsu treatment in order to reduce the fatigue associated with SpA.

Fatigue and back pain are among the most common and disabling symptoms for patients living with SpA [5]. Targeted therapies mostly focus on treating inflammation-mediated symptoms. Conversely, shiatsu can address multiple symptoms including pain but also fatigue and sleep disturbance, as shown in [21, 22], which are appropriate outcomes that will be assessed in the present study in SpA patients.

In the present study, we try to apply the main rules of research methodology to the study protocol. However, one of the most important specificities of shiatsu is that it adapts itself to the person who receives it and it is not limited theoretically to the sole effect of acupoint massage. In the present study, in order to limit bias, we focused on the efficiency of shiatsu pressure and trained the three shiatsu practitioners to provide shiatsu therapy sessions based only on the specific shiatsu pressure protocol (see Figure S1 in the electronic supplementary material for details). Another potential issue was the conceptualization of a sham shiatsu procedure. Several different styles of shiatsu exist worldwide: some consider only the meridian points and also add some new ones, while others consider only the osteo-articular aspect of shiatsu, claiming that its founder, Tokujiro Namikoshi (1905–2000), never approached the energy dimension and that shiatsu was recognized by the Japanese Health Ministry on those grounds. We decided that the common point in all the shiatsu styles was the pressure applied to the body. In the present trial, we took a pragmatic and material approach, rather than an emotional and energetic approach. It would be another challenging task in the future to design a research trial with a “free” shiatsu that could be tailored to the patient and not only to specific symptoms.

We thus acknowledge a limitation in the present study, as there was no placebo group in this randomized controlled trial; indeed, in “energy medicine”, a real sham procedure is impossible. The “sham” acupressure we chose based on light touch may produce an effect. However, if, in addition to the acupressure and sham acupressure groups, an inert control group had also been included, the design of the protocol would have been less ethical than the cross-over design we conceived.

In the present study, we use a specific shiatsu/acupressure protocol to study its effectiveness in SpA fatigue to facilitate replicability for future studies, rather than a complex treatment based on “energy” diagnosis.

We hope that this shiatsu/acupressure study will adequately explore the effectiveness of shiatsu as an intervention in the care of patients with SpA and specifically in relieving its associated fatigue.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study is conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by an ethics committee (Sud Mediterrannée 1, approval number: 21. 04,540.000095). We registered the study with the clinical trials registry (registration number NCT05433168).

Strengths and Limitations of this Study

This study represents the sole randomized controlled cross-over trial to date assessing the effect of shiatsu therapy in the treatment of fatigue in SpA patients. The study design allows cross-over between shiatsu and sham shiatsu therapies. All participants will be followed up to 50 weeks. The study design does not include an inert control group. The single-center study may be a limitation due to potential recruitment biases.

Ethics and Dissemination

Trial results will be disseminated at relevant clinical symposia and society meetings, published in peer-reviewed journals and disseminated through relevant patient associations. This research will make it possible to show the clinical relevance of shiatsu therapy for reducing fatigue in patients living with SpA. Stakeholder partners will contribute to disseminating the study findings in order to raise awareness of the benefits of using shiatsu treatment as a non-pharmacological option for fatigue management in the SpA population.

The protocol’s version and date are Version 2 and July 15, 2022. The first participants were recruited in September 20, 2022. The recruitment is currently open.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mrs. Nathalie Dorland and Mrs. Sophie Leclercq, professional shiatsu practitioners, for their intervention in the study. We thank the Syndicate of Shiatsu Professionals for their help in the development of this study.

Funding

This research was funded by the University Hospital Center of Orleans but did not receive other funds from commercial or not-for-profit sectors. The journal’s Rapid Service Fee will be funded by University Hospital Center of Orleans.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: NB and EL; Investigation: NB and EL; Methodology: AV; Data curation: PP and NB; Project administration: EL, HT and NB; Writing of original draft: NB and EL; Writing-review and editing: all the authors have read and approved of the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Nathalie Bernardinelli, Antoine Valery, Denys Barrault, Jean-Marc Dorland, Patricia Palut, Hechmi Toumi, Eric Lespessailles have nothing to disclose Denys Barrault and Patricia Palut are now affiliated with IPROS, University Hospital Center of Orleans, Orleans, France.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study is conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by an ethics committee (Sud Mediterrannée 1, approval number: 21. 04,540.000095). We registered the study with the clinical trials registry (registration number NCT05433168). All participants provided and will provide informed consent to participate in the study. All participants provided consent for publication if any identifying information is included in the manuscript.

Data availability

The data is available.

References

- 1.Prati C, Claudepierre P, Pham T, Wendling D. Mortality in spondylarthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2011;78:466–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakland G, Gran JT, Nossent JC. Increased mortality in ankylosing spondylitis is related to disease activity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1921–1925. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.151191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakland G, Gran JT, Becker-Merok A, Nordvåg BY, Nossent JC. Work disability in patients with ankylosing spondylitis in Norway. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:479–484. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wendling D, Claudepierre P, Prati C. Early diagnosis and management are crucial in spondyloarthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2013;80:582–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gossec L, Dougados M, D’Agostino M-A, Fautrel B. Fatigue in early axial spondyloarthritis. Results from the French DESIR cohort. Jt Bone Spine. 2016;83:427–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearson NA, Tutton E, Martindale J, Strickland G, Thompson J, Packham JC, et al. Qualitative interview study exploring the patient experience of living with axial spondyloarthritis and fatigue: difficult, demanding and draining. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e053958. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deodhar AA, Mease PJ, Rahman P, Navarro-Compán V, Strand V, Hunter T, et al. Ixekizumab improves spinal pain, function, fatigue, stiffness, and sleep in radiographic axial Spondyloarthritis: COAST-V/W 52-week results. BMC Rheumatol. 2021;5:35. doi: 10.1186/s41927-021-00205-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deodhar A, Conaghan PG, Kvien TK, Strand V, Sherif B, Porter B, et al. Secukinumab provides rapid and persistent relief in pain and fatigue symptoms in patients with ankylosing spondylitis irrespective of baseline C-reactive protein levels or prior tumour necrosis factor inhibitor therapy: 2-year data from the MEASURE 2 study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019;37:260–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deodhar A, Mease P, Rahman P, Navarro-Compán V, Marzo-Ortega H, Hunter T, et al. Ixekizumab improves patient-reported outcomes in non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: results from the coast-X trial. Rheumatol Ther. 2021;8:135–150. doi: 10.1007/s40744-020-00254-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strand V, Deodhar A, Alten R, Sullivan E, Blackburn S, Tian H, et al. Pain and fatigue in patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: multinational real-world findings. J Clin Rheumatol. 2021;27:e446–e455. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000001544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, Altman DG, Mann H, Berlin JA, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ. 2013;346:e7586. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the functional assessment of cancer therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13:63–74. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(96)00274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2286–2291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pham T, van der Heijde DM, Pouchot J, Guillemin F. Development and validation of the French ASQoL questionnaire. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28:379–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiltz U, van der Heijde D, Boonen A, Cieza A, Stucki G, Khan MA, et al. Development of a health index in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (ASAS HI): final result of a global initiative based on the ICF guided by ASAS. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:830–835. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenkinson TR, Mallorie PA, Whitelock HC, Kennedy LG, Garrett SL, Calin A. Defining spinal mobility in ankylosing spondylitis (AS). The bath AS metrology index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:1694–1698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pilgaard T, Hagelund L, Stallknecht SE, Jensen HH, Esbensen BA. Severity of fatigue in people with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and spondyloarthritis—Results of a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0218831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.epiR: Tools for the Analysis of Epidemiological Data: available 2022. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=epiR [Assessed on Oct 05, 2022].

- 21.Molassiotis A, Sylt P, Diggins H. The management of cancer-related fatigue after chemotherapy with acupuncture and acupressure: a randomised controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2007;15:228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsay S-L, Cho Y-C, Chen M-L. Acupressure and transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation in improving fatigue, sleep quality and depression in hemodialysis patients. Am J Chin Med. 2004;32:407–416. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X04002065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data is available.