Abstract

Since 2015 the need for evidence-based guidance in primary health care management of refugees, asylum seekers, and immigrants has dramatically increased. The aims of this study were to identify the challenges met by primary care physicians in Switzerland, by performing semi-structured interviews and to identify possible approaches and interventions. Between January 2019 and January 2020, 20 GPs in 3 Swiss cantons were interviewed. The interviews were transcribed, coded with MAXQDA 18, and analyzed using the framework methodology. Following relevant findings were highlighted; (i) problems relating to health insurance companies among (health-insured) asylum seekers and refugees were negligible; (ii) there is a high acceptance for vaccination by refugees, asylum seekers, and immigrants; (iii) limitations in time for consultations and adequate reimbursement for practitioners pose a serious challenge; (iv) the majority of consultations are complaint-oriented, preventive consultations are rare; and (v) the language barrier is a major challenge for psychosocial consultations, whereas this appears less relevant for somatic complaints. The following issues were identified as high priority needs by the study participants; (i) increased networking between GPs, that is, establishing bridging services with asylum centers, (ii) improved training opportunities for GPs in Migration Medicine with regular updates of current guidelines, and (iii) a standardisation of health documentation facilitating exchange of medical data, that is, digital/paper-based “health booklet” or “health pass.”

Keywords: asylum seekers, healthcare access, physicians, refugees, Switzerland

Introduction

By the end of 2020 more than 2 million foreigners, including refugees and asylum seekers, were reported to be living in Switzerland. 1 Following the European refugee crisis of 2014 to 2015, host countries faced new public health challenges due to the unprecedented influx of migrants. In 2015 alone, Switzerland received close to 40 000 new asylum applications, representing the highest recorded influx since 1999 during the (Balkan countries) conflicts in Kosovo. 2

In addition to the extent of asylum seekers arriving from conflict areas in the Middle and Far East, such as Syria, Iraqi, Tibet (China), and Sri Lanka—especially Sub Saharan African countries including Eritrea, Somalia, Ethiopia were among the leading origins of refugees arriving in Switzerland, according to the state secretariat for migrants.1,2

In Switzerland, currently a third of asylum seekers and refugees are from Eritrea. 3 During the COVID-19 pandemic the migration trend of new arrivals to Europe decreased temporarily, and in the global and European context, the influx of immigrants is expected to rise above the pre-pandemic levels.1,4

Upon arrival in the host country, immigrants face a diverse set of challenges. After an often arduous journey lined with uncertainty, poverty, and disconnection of previous values, they face language barriers, tedious asylum application processes, limited access to work and healthcare, and many more, negatively affecting the critical phase of integration.

Health-related issues include chronic infectious and increasingly non-communicable diseases—especially mental health is of particular concern—many of which are potentially acquired or aggravated by passing through countries with limited healthcare facilities and/or conflict settings during the migration pathway. Upon arrival in Europe, a number of barriers are encountered that complicate integration and healthcare seeking behavior; these include limited understanding of healthcare systems and facilities in the host country, language, cultural and religious factors, as well as isolation, and insecurity leading to mistrust, which further impairs any efforts made.5,6

These barriers have been poorly characterised at the primary physicians’ health care level—especially from the view of the increasingly challenged GPs, who are seeing a rising number of patients from countries abroad and encountering a disease spectrum they were previously not exposed to—often intersecting between internal, psychiatric, tropical, and travel medicine aspects.7,8 Clearly, developing a prospective evidence-base for the major health challenges of asylum seekers and refugees would be ideal for identifying the dynamic challenges and needs for improving the access to healthcare and informing policy makers.

In this study, we explored the utilization of the primary healthcare system with a view on migration health challenges encountered mainly by sub–Saharan African (SSA) asylum seekers and refugees in North-Western Switzerland (Basel-City, Basel-Land, and Solothurn). Thus, identifying the major challenges from a Swiss family physician perspective was the basis for this study.

Methods

Participants

A comprehensive list of General Practitioners (GPs) in Northwestern Switzerland was generated, from which 174 interviewees were contacted for study participation via invitation letter mailed per post. Inclusion criteria required a documented exposure and experience with care or consultation of refugees and newly admitted asylum seekers under the Family physician healthcare model (HMO). Participation required the signing of a written informed consent sent with the invitation letter. A total of 20 primary healthcare physicians responded positively to participate in the study. All responders could demonstrate access to and availability for refugees, asylum-seekers, and patients with a migration background, including appropriate quality-of-care and regular clinical patient experience with this population. During the course of interviews it was evident that these 20 GPs represented the majority group of GPs that took care of the regional population of refugees, asylum-seekers, and patients with a migration background, and represented the most experienced individuals as experts for this study. About 11/20 (55%) of the participating GPs were male, 12 (60%) are based in Basel-Stadt, 7 (35%) in Basel-Land and 1 (5%) is based in Solothurn. About 18 (90%) of the GPs work in a GP group practice (Note. Original Table 1 was deleted, as it did not add relevant information).

Table 1.

Terms and Definitions of Migration.

| Definition | |

|---|---|

| Migrant | A person who has voluntarily left his or her home country to live temporarily or permanently in another country (area). |

| Refugee | A person who, owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of which he or she is a national and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself or herself of the protection of that country. |

| Asylum seeker | A person seeking safety from persecution or serious harm in a country other than his or her own and awaiting a decision on an application for refugee status under international and national laws. |

Measures

The semi-structured interview guide used in this open in-depth qualitative study was designed by consultations of an interdisciplinary research team, consisting of clinicians, social scientists, migration health advisors, and travel health experts. All interviews were held in German or Swiss German and conducted by the first author with a second author. The average time lap for each interview was around 45 minutes. The semi-structured interviews were held in non-clinical research study setting, but at the physicians’ office. Anonymity and confidentiality of informants were ensured by removing participants’ names.

Terminology

To prevent inconsistent use of migration-related terminology, we distinguished between refugees, asylum seekers, and immigrants during the semi-structured interviews in this study, and used the terms as listed in Table 1. 9 A quote by a family physician highlights this by stating;

But you must distinguish between refugees, asylum seekers and patients with a migration background; these are three completely different groups of patients. Refugees are underserved, asylum seekers are okay served, and migrant patients are normal served. 10

Data Analysis

Interview data were analyzed using the framework method, following the 6-step qualitative data analysis procedure. 10 Indexing or coding of the data was performed using the MAXQDA 18 11 qualitative data analysis tool. After repeated careful reading steps, data were coded into themes and specific topics. Codes and memos were shared and discussed among research team members to develop an analytic framework. The study followed the guidelines for qualitative research as well as the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research. 12

Results

All GP practices were located either in the city or in the metropolitan-area, and all GPs demonstrated a professional clinical experience ranging from 5 to over 20 years (accounting for the number of years working as a GP). The socio-economic status of the patient population visiting the GP practices was not assessed. The outcomes derived from the open in-depth semi-structured interviews with family physicians, were focused on the following areas; (i) health system related, including insurance and insurance models; (ii) prevention themes, including vaccination coverage and adherence to treatment/management; (iii) consultation seeking behavior and language barrier issues within a psychosocial context, and (iv) the GPs perspective.

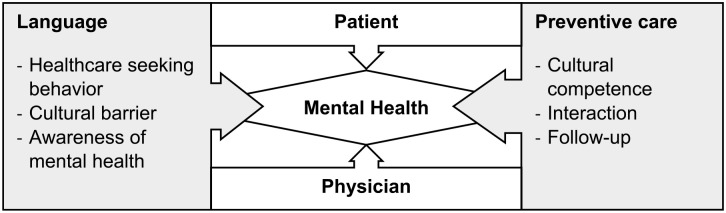

Four key areas were addressed in the various discussion topics summarized as the “4 Cs” (Figure 1); Communication (ie, networking, and exchange among physicians), Compliance (ie, acceptance of vaccination and preventive measures), Competence (ie, knowledge of healthcare and insurance systems), and Consultation (ie, healthcare seeking knowledge, behavior, and barriers).

Figure 1.

Focus of the interview topics.

Health System Related Findings, Including Insurance and Insurance Models

Since 2019, all asylum seekers in Switzerland receive full health insurance coverage from the moment they submit an asylum application at a border or to the state secretariat of migration (SEM). 13

[They] just have the mandatory, [they] all have basic insurance. And [they] are treated exactly the same as others.

Healthcare providers were asked whether they experienced problems relating to health insurance and whether the insurance system affected their medical approach or their routine procedures (“Do you experience health insurance related problems in the patient care?”, “Are your medical approaches and your medical routines affected? For example, does the insurance system play a role in your patient care?”) Disruptions in health insurance processing were denied, and family physicians did not indicate any problems with the insurance companies. Referrals to specialists or specific therapies were covered and did not cause any problems in their daily routine. However, around 15% of the interviewed GPs, highlighted disruptive factors relating to delays in billing procedures, especially in the handling of new admissions, and importantly an absence of a process for the financing of translators. Especially GPs without long term experience with patients of a migration background/asylum seekers/refugees described this more frequently as an obstacle.

Firstly, it’s the time factor for me. . . then also the translator, who costs twice as much. And then [it’ s]; also such different disease concepts. . . that can take even longer. . . and when it gets much longer, they [physicians] get to their limits with billing for all that.

In the study, family physicians’ function within an HMO model in the treatment of patients, especially for newly arrived asylum seekers, as is common in the cantons studied. In Switzerland, HMO stands for “Health Maintenance Organization” and is an alternative insurance model for basic health insurance. Under the HMO model, policyholders are required to consult a particular HMO practice first in the event of illness. Because the choice of doctors is limited, policyholders choosing this model benefit from a premium reduction of up to 25% compared to the standard model.

Within this GP model, anyone can treat asylum seekers. . . .

In this model, the family doctor takes a central coordinating role, and patients primarily consult their family doctor for health-related problems. 13 During the period where asylum seekers live in an asylum center, the staff physician of the respective center is seen, and later upon transitioning from center to independent housing, a family doctor nearby is found. If a specialist is required for certain investigations, the family doctor refers the patient but keeps a “gate-keeper” function and collates all findings in the medical history.

I think the most important thing is that they have a point of contact, . . . have a family doctor and don’t go to the hospital [independently]. . . This family doctor philosophy, with the continuous care. . . that’s important. . . they just need “a safe haven” for medical problems.

Trust was emphasized several times as a prerequisite in treating patients, as well as the commitment of the primary care physician in providing continuous care.

Ultimately, it’s also a little bit about them having one more place. . .where they can unload certain things and where there’s a way to discuss that

In this study, the health management issues for the particularly vulnerable group of non-legal migrants and rejected asylum seekers were not included, as these relate to more specialized outpatient clinics. The study distinguished between asylum seekers, refugees, and migrant patients, but there was no further differentiation within the latter group.

. . .what has not been discussed at all now is the status. I mean, these are people in an asylum procedure, and they are relatively safe. We also have people who are here illegally or who have no documents. And for them it is completely different. They have completely different questions and issues.

Prevention-Related Findings—Vaccination and Adherence to Treatment/Management

An important part of basic medical care relates to vaccination as a preventive measure. (“How is the willingness for vaccination? (For the patient and his/her family/children) Are there any difficulties with education?”, “Can you name factors that may be barriers?”) Regarding the inquiry on willingness to vaccinate, vaccine hesitancy, and difficulties in providing information, the interviewed physicians confirmed an overall good acceptance of proposed vaccinations and a very high willingness to vaccinate on the part of the patients.

. . ., I have treated people from all over the world, . . ., the willingness to vaccinate is high and people. . . in many countries actually accept vaccinations as a gift from the state. . . .

Although, the physicians’ propositions for vaccination are willingly accepted and not rejected, the documentation of vaccination—that is, finding a record of previous vaccines before migration is a real problem, as mentioned by nearly one third of the physicians.

If you offer it, it is actually good the vaccination willingness. It is just difficult to find out who has been vaccinated and how. . . But if you recommend it, . . ., definitely not a problem.

To resolve such obstacles, vaccination guidelines, such as the published guidelines “Vaccinations in Adult Refugees” 14 were mentioned as particularly helpful and important—especially as “tailored” vaccination strategies are mentioned for situations where the previous vaccination history of a patient remains unknown.

. . .there’s just. . .the documentation that they [don’t] have that with them.

These refugee-oriented guidelines are pragmatic and practical in supporting adequate vaccine coverage of asylum-seekers and refugees to Swiss standards, even if the vaccination status remains unknown.

. . .there are certain guidelines that have been published and that is very helpful.

Additional challenges mentioned are the number of vaccinations received and complying with the correct vaccination schedule, upon arrival in the host country. It was mentioned that scheduling follow-up vaccinations was difficult; on one hand, because communication was difficult (as it had to be explained that a single vaccination was not sufficient) and on the other hand, because consultations sometimes need to be planned for longer intervals between vaccinations. It was recommended to plan a clear follow-up vaccination schedule in advance and to provide reminders. A few GPs mentioned that some patients are illiterate so that they train their office staff to make sure that the patients know their follow-up appointments.

Consultation-Seeking Behavior and Language Barrier Findings

A viewpoint discussed among prevention measures, regarded the healthcare seeking behavior of asylum-seekers and refugees; in addition to general preventive measures in primary care, the GPs were asked in what context they were consulted for preventive examinations (ie, screening procedures). (“When and how often do refugees/asylum seekers/migrants from sub-Saharan Africa need medical care? In what context are you (medical staff/interviewees) visited?”, “Do patients come to you with special requests or desires, for example, checkups, screening?”, “Is it common for you to be consulted for a general check-up?”) Patient visits were more often about acute somatic complaints, and consultations were more problem-oriented and often perceived with a cultural influence according to the origin of the patient.

But the approach. . ., like all the screening, check-ups, what can you do, what has [you] already done, . . . is certainly different. I think it’s. . . more focused on something that’s current, rather than some overview of all the different points. For that, it needs a level of differentiation, from the language, but also from the same culture, which also plays a role, which is certainly different.

GPs specified that requests for general or specific examinations were also culturally based (ie, requests for medical imaging, check-up requests for diabetes, hypertension, requests for HIV-testing, or requests for general check-ups), which has also been described in previous studies.15,16

. . . You can’t make a blanket statement like that. . . . there is a difference between people who come from the African continent and people who come from . . . Syria, for example. . . . the Syrian asylum seekers . . ., want more check-ups. . . . They are . . . obviously used to a different medical level. . . . I think there is a difference.

Language Barriers in the Psychosocial Context

Although language barriers are perceived as less limiting when concerning visits about vaccination or somatic illnesses, this issue is repeatedly mentioned to be of enormous importance when it comes to assessing and treating psychosocial problems. (“Do you think patients are able to express their concerns, complaints, and feelings without language assistance?”, “Do you think patients are able to express their concerns, complaints, and feelings without language assistance?”, “Which language aids do you use?”)

There’s often a lot of desperation in communication and such an intuitive groping in the dark, but so for the mundane problems, somehow a flu-like infection or an acute musculoskeletal problem, that’s not a problem. But the more complex ones. . . that’s really bad, it doesn’t work at all. . .

The language barrier presents itself as a consistent obstacle of communication within the doctor-patient relationship. The unclear and limited financial coverage in the tariff structure for billing the use of translators, leads to the fact, that refugees and asylum seekers usually face their doctors alone without professional language support. In the case of acute, somatic complaints, it is often possible to work with linguistic aids such as Google Translate or Skype/telephone conversations with German-speaking acquaintances, in the case of psychological problems (ie, anxiety management, post-traumatic stress disorder etc.), the language barrier is a major challenge, and German-speaking acquaintances usually do not have the trust or language depth of skill required to be helpful.

It depends for which questions. Now if someone comes where you can . . . examine and measure, it’s not so important if there is a translator, but if it’s psychosocial . . . then you can’t do it without a translator.

More language and cultural competencies are needed when assessing mental health and psychosocial problems.

I think that for the whole psychosocial background, . . .you would have to ask yourself if you want to and can use even more resources there, but then that requires corresponding intercultural and linguistic competencies, . . . .

In addition, the language barrier was mentioned as a challenge when making appointments, explaining interventions and further diagnostics.

. . . the uncertainty as to whether I have really understood the patient correctly, in all his problems, and also the perception as to whether he is now really satisfied with what I have suggested to him or not. I get a much better impression with a patient from the same culture and the same language.

The GPs Perspective—Improving the Network and Communication Platforms

The need for improved networking platforms amongst migration medicine practicing physicians and facilitating exchange between GPs and asylum reception centers was expressed. (“For your part, what would you like to see in terms of optimal health care for refugees/asylum seekers/patients with a migration background?”) A call for better coordination and inclusion of tertiary healthcare service providers, that is, emergency and hospital outpatient services, was also made. Closer and more regular collaboration with social workers was desired. Improvement of migration-specific services in the outpatient setting requires priority, with access to interpreters with an established mechanism to claim remuneration for their services (Tarmed tariff regulations?). This is especially critical for immigrant patients with psychosocial problems; there is a need for a contact network including help points.

Language is and remains a problem. . . and I think that if one should now give a message to the outside world, then one should create, not only the clinics, but also in the practices the possibility to professional interpreters. I do think that the language barrier is a real barrier. . .

As an example, the services of the outpatient clinic transcultural psychiatry of the Psychiatric Clinics at the University Hospital of Basel (UPK) were mentioned as very helpful. The need for better access and availability to psychiatrists for common migration-associated issues was expressed.

There are overall many psychiatrists, but there is a lack of a focus on migration-oriented psychiatrists that one could ask. . . .

Some GPs stated that some of the required needs already exist and can in part also be financed through uncommon pathways like social welfare, but that even then the utilization of these services add to the already substantial administrational and organizational burden and even as such represent a hurdle in improving healthcare provision.

The whole interpreter situation. . . that was also one of those things when you finally realized that having an interpreter here is actually not such a problem. Social welfare finances it if you need it. We just have to claim it and learn to work with it.

The family doctor represents a “center” for the healthcare of many patients, where they have a stable contact person, a constant ear for complaints and problems, a service where all results are collated—that is, a “safe haven.” The centralized documentation of medical data plays an important role to create a sense of “continuous care.” However, due to the dynamics of migration, subsequent possible changes of location and associated change of doctor, the concept of a medical dossier accompanying the patient came up, similar to the concept of the “family booklet,” where all medical information was collated.

The need for improved access to training and updates for guidelines

The last point mentioned as approach for personal improvement of GPs activities was investment in continuing education (CE) in the transdisciplinary field of migration medicine. CE should be maintained—not only for specialists—but also for medical students. This requires expansion into language resources and transcultural competencies with easier accessibility at a lower threshold. Investment in updates and communication of guidelines was also felt to be important, especially vaccination guidelines, were felt to be very helpful. Table 2 summarizes the major findings of the experts’ opinion-seekeing an open in-depth interview using structured interview guideline.

Table 2.

Summary of the Most Important Findings and Approaches to Solutions, Derived From Open in-Depth Interviews With GPs Using Structured Interviews.

| Topics | Outcome and reflections | Implication and approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Vaccination | High acceptance, despite of challenges of documentation, and unavailability of vaccination records | Vaccination book-let and e-vaccination dossier |

| Insurances/Health insurance | Sufficient coverage of Swiss health insurance funds and insurances for asylum seekers/refugees/patients with a migration background | Solution for insurance/health insurance of “non-legal” and rejected patients in need of medical care |

| Consultations | Mostly complaint-oriented—preventive consultation

approaches are rare Continuity of care when visiting several physicians is aggravated by patient mobility, continuous change of address→difficult to keep track Psychological problems, such as depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress disorder are very common |

Improvement of documentation and exchange of medical

data, by means of a “health booklet” or “health

passport” approach Taking advantage of preventive offers, also on the part of the attending physicians |

| Language barrier | Especially problematic for psychosocial and mental problems—less so for somatic and preventive problems | Improved access to and financing of translators and transcultural skills |

| Administration | Very high time expenditure and difficulty in billing/reimbursing of long and complex consultations | Delegate administrative work time or account for it more easily |

| Network | Insufficient exchange of information between physicians in the field of migration health, and linkage with the Swiss Federal Asylum Centers | Expansion of networks between family doctors and with

asylum centers Simplified access to bridge offers (ie, transcultural consultations and social workers) Better exchange with Federal asylum centers |

| Further education | Insufficient further education and training

opportunities Networks or platforms for sharing important problems or findings Unavailability of opportunity to get acquainted with new guidelines |

Increased availability of continuing education for

primary care physicians with regular updates of current

guidelines Improvement and expansion further of access to guidelines through workshops, training, and exchange platforms |

. . . Ultimately, you have to like these patients, I think that’s a task for us as trainers or educators, that you convey to the students that it’s something great to treat migrants and people realize that you like them, if you take them seriously or if you perceive them as an obstacle. . . as soon as they realize that you treat and care for them the same way as Swiss patients, they feel comfortable and feel understood and then a lot is already achieved.

Discussion

Multiple studies have already dealt with identifying obstacles in the management of patients with migration background. 17 This study focused on the difficulties that primary health care providers encounter in managing healthcare services for asylum seekers and refugees. The barriers that GPs encounter are poorly characterised and remain under appreciated. Today’s primary health care provision is increasingly challenged with rising numbers of international immigrants and a broad spectrum of health problems that cannot be handled without a transdisciplinary approach. This study is a first step in opening the dialogue with family physicians, toward understanding their view and needs for improving healthcare provision at the primary level.

Health System Related Findings: There Is Good Insurance Coverage, But Better Access to Health Information and Improved Communication Between Healthcare Staff Is Needed

Through extensive discussions the participants revealed that the basic prerequisites for asylum seekers and refugees to access the health care system are in place; the universal health insurance system via the HMO model appears to be functioning well. In contrast to our expectations, no significant problems with the insurance system were found. This positive finding can be attributed to the collective health insurance of all asylum seekers in Switzerland since 2019. 18

Unfortunately, this is not the case for marginalized and vulnerable undocumented migrants “sans papiers” or asylum seekers that were rejected. The distinction in the status of migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers, is reflected by the differential access to health care they receive and that our results cannot be generalized to all migrants. A future goal could be to enable all immigrant or refugee patients, regardless of their residence status, to have access to universal health coverage and thus to the health care system.

In the HMO model health insurance system, the family doctor assumes a central mediating position and coordinates the efforts of medical specialties, hospitals, and asylum centers to create a centralized collation of health information—of perceived as a “safe haven” for migrants. However, the GPs state in interviews that information is poorly transmitted within the network between specialists, hospitals, and asylum centers, creating an additional burden for primary physicians. The increasing mobility of asylum seekers and refugees even within the host country emphasizes the need for these networks to develop and facilitate information exchange between health care workers. This would improve cost effectiveness, reduces the burden of GPs, and importantly benefit the health of the migrants. This issue was raised several times by the study participants, who openly criticized the common consequences of interruptions in the doctor-patient relationship and patient management.

As an example, some investigations are handled hesitantly or superficially due to concerns about lack of follow-up, and findings from previous interventions are not available. The approach for “mobile data” that remains with the patient or that could be accessed centrally was expressed several times. This could be implemented, for example, in the form of a health booklet/family booklet, as already implemented by pediatric physicians in Switzerland. Further suggestions were made regarding online retrievable medical data, for example via AHV number, e-booklet, mobile Health (mHealth). Legal framework conditions would have to be defined for this to prevent data leakage of personal health data for patients.

Prevention-Related Findings—Vaccination and Adherence to Treatment/Management

Despite these challenges, a strong positive perception toward vaccination among refugees and asylum seekers was reported. Study participants noted less difficulties and lower persuasion efforts in educating patients, compared to the native population. However, to ascertain long-term adherence to a vaccination plan including follow-up visits, physicians need to provide a reminder structure. It is established that “reminder/recall interventions,” as well as improved awareness, lead to better vaccination coverage. 19 Having trust in the physician is a key determinant in vaccination decision-making, as demonstrated in recent vaccine hesitancy literature. 20 Interviewees highlighted that the first doctor-patient contact should aim to build trust and not to administer as many vaccinations as possible—this is even mentioned in Swiss vaccination recommendations for under-vaccinated asylum seekers and refugees. 14

GPs reflected on their impression that the acceptance and perception of the importance for preventive healthcare services was higher when resources of the health care system in the country of origin were lower. A discrepancy in this acceptance was seen between children, adolescents, and adults; younger patients appear more systematically and comprehensively involved in preventive services within the framework of school medical services. It is conceivable that children and adolescents with access to the school system experience better integration and that this may act as a protective factor on their health.

. . .that is always the discussion, the young people, they are just not vaccinated by us or practically not. This has always gone through the school doctor clinic. . .I think children and adolescents somehow already get through that they are vaccinated. . .

In practice, the documentation of vaccination status is often not or only partially available (incomplete information), which complicates subsequent medical care substantially—especially for follow up visits with different doctors. Digital solutions, such as photographing documents with a mobile phone or national digital vaccination card strategies, were seen as a way forward and could be used to mitigate this problem. The federal government recommendations regarding vaccinations and their documentation were repeatedly stated as informative and helpful to effectively address this issue.14,21

Consultation-Seeking Behavior and Language Barrier Findings

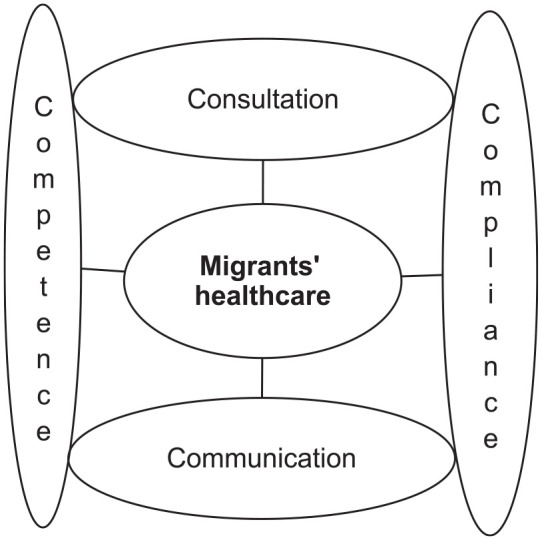

Our primary care physicians saw more patients for problem-oriented consultations, than preventive examinations (eg, check-ups and screening). The reasons were thought to be a lack of awareness and knowledge about what the health care system has to offer, resulting in reduced active inquiry from patients. How a disease is perceived and understood, or how prevention is dealt with, also depends (among other factors), on the respective culture—which includes seeing a doctor even in the absence of acute complaints. 15 The low rate of preventive medical checkups is partly due to migrants being younger and healthier—compared to the native (older) population. 22 However, during many symptom-oriented visits underlying psychosocial problems are revealed. Mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress disorder, occur more frequently in refugee patients. 23 Previous studies have showed the risk of depressive disorders to be twice as high among men with a migration background, than without, 16 and language barrier difficulties further complicate the management of mental complaints. All GPs agree that “mental health,” language barrier issues and attitude to preventive care are closely linked (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The interactions of language barrier and attitude toward preventive care in the setting of mental health management.

Previous studies in Germany, suggest that language barriers have less impact on the use of health care institutions, than factors like cultural, socioeconomic backgrounds and lack of knowledge about the system in the host country.16,24 In this study, the language barrier issue was raised in most of the interviews and was felt to be a serious challenge—especially in mental health related sessions. Individual GPs mentioned that a professional translator can be an additional obstacle in the doctor-patient relationship. Various modalities such as Google Translate, Skype, or conventional telephone calls with relatives or acquaintances are often used, usually initiated by the patients themselves. Previous studies have established that friends and family are suboptimal for translation solutions, especially when children act as translators for their parents as sensitive personal topics cannot be openly addressed.25,26

If the problems are of psychological origin or particularly complex, the language barrier represents an urgent problem, and if specialized outpatient clinics with transcultural competencies are available, they are called upon. Thus, many GPs participating in this study refer their patients to transcultural psychiatry to obtain a detailed migration history. Often a better evaluation of the psychosocial complaints can be achieved and professional translation is available—this however strongly depends on the availability of psychiatric care in the region. 27

Limitations of the Study

The participation of GPs in this study followed a selection procedure of voluntariness, which is prone to “selection bias.” All participating GPs regularly see asylum seekers, refugees, and migrant patients, in some cases with decades of experience—this could influence motivation to participate in the study. Some information could have been lost in the translation process from Swiss German to German or English. Lastly, the gender of participants was not stratified for during interviews, and further studies examining the effect of gender in GPs are warranted.

Conclusion and Outlook

This study used a qualitative approach to identify challenges of primary care physicians in Switzerland caring for refugees, asylum seekers, and patients with a migration background. GPs represent the primary point of contact for patients with medical questions, and in their role as “gate-keepers,” provide patients with a point-of-reference when confronted with a new health care system. Further, GPs can inform new immigrants about features of the new healthcare system, which in itself is an important component of the integration process. Despite emerging digital tools such as Google Translate, the language barrier continues to pose a major obstacle in the care of patients who do not speak the same language as their physician. Managing mental health problems, requires more often than not specialized outpatient clinics, which at present are underrepresented in Switzerland. The availability of and continuous education for recommendations and guidelines are needed and desired by GPs. While health insurance coverage is working well, continuity of care requires improved communication and exchange platforms for healthcare staff, and a digitalized solution for migrants to ensure access to their own health data—especially as migrants have a higher frequency of changing doctors and places.

This is one of very few Swiss studies on identifying problems of primary health care providers (as opposed to the migrants view). Strengthening the role of GPs in managing asylum seekers, refugees, and patients with a migration background is important, as GPs have a central but still under appreciated role in the integration process.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the all general practitioners (GPs) who volunteered to participate in the study, and shared their thoughts, experiences, and views through the open in-depth interview.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: JO, VS, AC, and DP have designed the study. JO and VS did data collection, translation, and translation. JO, VS, and AC, did the coding. JO, VS, and SM did the interpretation and analysis. JO, AC, and DP wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was funded by a Swiss School of Public Health (SSPH+), an Inter-university Initiatives and Collaborations launched in January 2017 following the “Foster Interuniversity Initiatives and Collaborations” call.

Ethical Approval: Study approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Northwestern and Central Switzerland (EKNZ), application No. 2018-01241. Anonymity and confidentiality of the participants and their patients were fully maintained. All volunteer participants in the study signed a written informed consent form for the open and in-depth interview using a structured interview guide.

ORCID iD: Afona Chernet  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8664-299X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8664-299X

References

- 1.SEM SfM. Ausländerstatistik 2020. 2021. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.sem.admin.ch/sem/de/home/sem/medien/mm.msg-id-82242.html

- 2.SEM SfM. Asylstatistik 2015. 2016. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.sem.admin.ch/dam/data/sem/publiservice/statistik/asylstatistik/2015/stat-jahr-2015-kommentar-d.pdf

- 3.SEM SfM. Asylsuchende aus Eritrea. 2019. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.sem.admin.ch/sem/de/home/asyl/eritrea.html

- 4.SEM SfM. Ausländerstatistik 1. Halbjahr 2021. 2021. Accessed July 13, 2023. https://www.sem.admin.ch/sem/de/home/sem/medien/mm.msg-id-84680.html

- 5.Lebano A, Hamed S, Bradby H, et al. Migrants’ and refugees’ health status and healthcare in Europe: a scoping literature review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pavli A, Maltezou H.Health problems of newly arrived migrants and refugees in Europe. J Travel Med. 2017;24(4). doi: 10.1093/jtm/tax016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chernet A, Probst-Hensch N, Sydow V, Paris DH, Labhardt ND.Mental health and resilience among Eritrean refugees at arrival and one-year post-registration in Switzerland: a cohort study. BMC Res Notes. 2021;14(1):281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chernet A, Probst-Hensch N, Sydow V, Paris DH, Neumayr A, Labhardt ND.Cardiovascular diseases risk factors among recently arrived Eritrean refugees in Switzerland. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglas P, Cetron M, Spiegel P.Definitions matter: migrants, immigrants, asylum seekers and refugees. J Travel Med. 2019;26(2):taz005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S.Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Software V. MAXQDA 2018. 2018. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://www.maxqda.com/maxqda-update-2018-1

- 12.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007; 19(6):349-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.BAG BfG. Medic-Help Asyl Bundesamt für Gesundheit BAG. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.medic-help.ch/de/medizinische-versorgung-in-der-schweiz/

- 14.Tarr P, Notter J, Sydow V, et al. Impfungen bei erwachsenen Flüchtlingen. Swiss Medical Forum. 2016;16(49-50):1075-1079. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaw SJ, Huebner C, Armin J, Orzech K, Vivian J.The role of culture in health literacy and chronic disease screening and management. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11(6):460-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rommel A, Saß AC, Born S, Ellert U.Die gesundheitliche Lage von Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund und die Bedeutung des sozioökonomischen Status. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015;58(6):543-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallimann C, Balthasar A.Primary care networks and eritrean immigrants’ experiences with health care professionals in Switzerland: a qualitative approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(14):2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eidgenösisches Departement des Inneren, Justiz-und Polizeidepartement. Gesundheitsversorgung für Asylsuchende in Asylzentren des Bundes und in den Kollektiv-unterkünften der Kantone [press release]. Eidgenösisches Departement des Inneren, Justiz-und Polizeidepartement; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarrett C, Wilson R, O’Leary M, Eckersberger E, Larson HJ.Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4180-4190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deml MJ, Buhl A, Huber BM, Burton-Jeangros C, Tarr PE.Trust, affect, and choice in parents’ vaccination decision-making and health-care provider selection in Switzerland. Sociol Health Illn. 2022;44(1):41-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Julia Notter SE, Philip Tarr Empfehlungen für Impfungen sowie zur Verhütung und zum Ausbruchsmanagement von übertragbaren Krankheiten in den Asylzentern des Bundes und den Kollektivunterkünften der Kantone. (BAG) BfG, editor. BfG; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rechel B, Mladovsky P, Ingleby D, Mackenbach JP, McKee M.Migration and health in an increasingly diverse Europe. Lancet. 2013;381(9873):1235-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindert J, Ehrenstein OS, Priebe S, Mielck A, Brähler E.Depression and anxiety in labor migrants and refugees: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(2):246-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santos-Hövener C, Kuntz B, Frank L, et al. [The health status of children and adolescents with migration background in Germany: results from KiGGS Wave 2]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2019;62(10):1253-1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaeger FN, Pellaud N, Laville B, Klauser P.The migration-related language barrier and professional interpreter use in primary health care in Switzerland. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hadziabdic E, Albin B, Heikkilä K, Hjelm K.Family members’ experiences of the use of interpreters in healthcare. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2014;15(2):156-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laubereau BK, Pim O, Manuela B, et al. Besoin d’assistance des médicins de famille et solutions. Schweizerische Ärztezeitung; 2017. [Google Scholar]