Key Points

Question

Is clinician well-being a cause for concern, and if so, what interventions hold promise for retaining physicians and nurses in hospital practice?

Findings

This cross-sectional multicenter survey study of 15 738 nurses and 5312 physicians found high and widespread burnout among clinicians in hospital practice that was associated with frequent turnover and patient safety concerns. In addition, clinicians lack confidence in management to resolve patient care problems and rated improvements in staffing and work environments as more important to their mental health and well-being than instituting clinician wellness and resilience programs.

Meaning

These findings indicate that enhancing clinician well-being and retention requires deliberate actions by management to improve nurse staffing, work environments, and patient safety culture.

Abstract

Importance

Disruptions in the hospital clinical workforce threaten quality and safety of care and retention of health professionals. It is important to understand which interventions would be well received by clinicians to address the factors associated with turnover.

Objectives

To determine well-being and turnover rates of physicians and nurses in hospital practice, and to identify actionable factors associated with adverse clinician outcomes, patient safety, and clinicians’ preferences for interventions.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a cross-sectional multicenter survey study conducted in 2021 with 21 050 physicians and nurses at 60 nationally distributed US Magnet hospitals. Respondents described their mental health and well-being, associations between modifiable work environment factors and physician and nurse burnout, mental health, hospital staff turnover, and patient safety. Data were analyzed from February 21, 2022, to March 28, 2023.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Clinician outcomes (burnout, job dissatisfaction, intent to leave, turnover), well-being (depression, anxiety, work-life balance, health), patient safety, resources and work environment adequacy, and clinicians’ preferences for interventions to improve their well-being.

Results

The study sample comprised responses from 15 738 nurses (mean [SD] age, 38.4 [11.7] years; 10 887 (69%) women; 8404 [53%] White individuals) practicing in 60 hospitals, and 5312 physicians (mean [SD] age, 44.7 [12.0] years; 2362 [45%] men; 2768 [52%] White individuals) practicing in 53 of the same hospitals, with an average of 100 physicians and 262 nurses per hospital and an overall clinician response rate of 26%. High burnout was common among hospital physicians (32%) and nurses (47%). Nurse burnout was associated with higher turnover of both nurses and physicians. Many physicians (12%) and nurses (26%) rated their hospitals unfavorably on patient safety, reported having too few nurses (28% and 54%, respectively), reported having a poor work environment (20% and 34%, respectively), and lacked confidence in management (42% and 46%, respectively). Fewer than 10% of clinicians described their workplace as joyful. Both physicians and nurses rated management interventions to improve care delivery as more important to their mental health and well-being than interventions directed at improving clinicians’ mental health. Improving nurse staffing was ranked highest among interventions (87% of nurses and 45% of physicians).

Conclusions and Relevance

This cross-sectional survey study of physicians and nurses practicing in US Magnet hospitals found that hospitals characterized as having too few nurses and unfavorable work environments had higher rates of clinician burnout, turnover, and unfavorable patient safety ratings. Clinicians wanted action by management to address insufficient nurse staffing, insufficient clinician control over workload, and poor work environments; they were less interested in wellness programs and resilience training.

This cross-sectional survey study explores physician and nurse burnout, intent to leave, turnover, mental health, work-life balance, patient safety, and preferences for interventions at 60 US hospitals.

Introduction

The hospital workforce remains in disarray despite the ebbing of the COVID-19 pandemic. The US Surgeon General has issued a national call to action in response to widespread reports that health care workers are reaching their breaking point.1 The US National Academy of Medicine is addressing the public health threat of high clinician burnout.2 Shortages of staff are among the top concerns of hospital leaders.3 Threats of strikes by physicians and nurses have increased, and progress in patient safety has slowed.4,5 The outpouring of public gratitude to clinicians during the height of the pandemic has failed to translate into actionable change by hospital management or public policies to address the causes associated with high clinician burnout and job dissatisfaction that predated and worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic.6,7,8,9

Knowledge of clinician well-being has mostly come from convenience samples of organizations and clinicians, and often from surveys of only physicians or only nurses.9,10,11,12 The US Clinician Wellbeing Study is a large, multisite collaborative investigation of the health and well-being of physicians and nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic practicing in 60 hospitals that received Magnet (American Nurses Credentialing Center) designation for being good places to work.13 This study explored the debate over whether interventions should prioritize bolstering the resilience of clinicians—a focus that angers many clinicians because it places the burden of adapting on them—or transforming hospital work environments to address modifiable sources of stress and burnout and to provide clinicians with more control over their work conditions.14,15

Methods

This cross-sectional study was reviewed and deemed exempt by the institutional review boards of the University of Pennsylvania and of the participating hospitals. Prospective respondents received an invitation to participate and information on the study’s purpose and design, including its voluntary nature and the anonymity of responses. Completion of the survey represented informed consent. This study followed Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines for cross-sectional studies.

Study Design, Data Collection, and Sample

This was a multisite collaborative study with data obtained via electronic surveys from more than 21 000 physicians (5312 respondents) and registered nurses (15 738 respondents) practicing in 60 US Magnet-recognized hospitals in 2021. The overall response rate was 26% (22% and 27% for physicians and nurses, respectively), and provided participating hospital-level information on turnover.

The Magnet Recognition Program is a voluntary institutional credentialing of good places to work based on nursing excellence and quality of health care as determined by the American Nurses Credentialing Center.13,16 Participating Magnet hospitals were enrolled as US twinning partners in the EU-funded Magnet4Europe intervention trial17 to improve mental health and well-being of clinicians in European hospitals.

In this study, the physician sample was drawn from hospitals with 10 or more physician-respondents and comprised 4064 attending physicians, 650 interns or residents, 212 fellows, and 125 other physicians from 53 hospitals. The registered nurse sample comprised 13 251 direct care nurses, 768 nurse managers, 194 advanced practice nurses, and 830 registered nurses in other positions from 60 hospitals.

Clinicians in adult medical and surgical specialties, including general inpatient units, intensive care units, and emergency departments, received electronic surveys. Each respondent described their mental health and well-being and the hospital’s staffing, management, patient safety, and quality of care. Respondents also ranked the importance of interventions to improve clinician well-being. Clinician surveys were modeled on multiple previous surveys of nurses from 1999 to 2021.18 Data collection occurred from January to June 2021. The final analytic sample included an average of 100 physicians and 262 nurses per hospital.

Clinician Well-Being Measures

Burnout was measured using the 9-item Emotional Exhaustion subscale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory,19,20 which has been associated with patient outcomes.21,22,23,24 Respondents were classified as high burnout if their score was higher than the published top tertile for health care workers (≥27).25 This measure has been used extensively and validated with physicians and nurses.26 Job dissatisfaction and intention to leave their employer were measured by single-item questions.27 Staff turnover was provided by each hospital as the number of full-time equivalents (FTEs) who resigned, retired, or were terminated, divided by the number of actual FTEs during the same period (1 FTE is the equivalent of 2080 hours per year).

Mental health measures included anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) associated with COVID-19, measured separately and together in a single measure. Anxiety was measured using Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 item28 scale. Depression was measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2-item29 scale. Clinicians were classified as having a positive result of screening for anxiety or depression with a score of 3 or greater. PTSD related to COVID-19 was determined using the Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5.30 Clinicians were identified as having probable PTSD if they responded yes to 4 or more of the 5 questions regarding whether traumatic event associated with COVID-19 had affected them during the past month. Additional clinician well-being measures included single-item global self-assessments of stress, work-life balance,31 overall health, and overall sleep. Overall health used the global health rating item from the Short Form-8 Health Survey.32 Overall sleep quality was assessed using the global quality item from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.33

Quality of Care and Patient Safety

Quality of care data provided by clinicians was in response to a single-item question that has been shown to be highly associated with mortality and other patient outcomes.34 Patient safety grades provided by clinicians ranged from A to F (per primary school grading system with no E grade available; unfavorable scores were C, D, and F).35 Clinicians rated patient readiness to manage care after discharge using a 4-point Likert scale dichotomized into “not confident” and “confident.” Culture of patient safety included 6 items from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture V1 reported as separate items and as an average across all 6 items.35

Resources and Management

Staffing was measured by asking clinicians whether there were enough nurses and to rate their own control over their workload.36 Items from the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index37,38 were used to describe clinician relationships with hospital management and with team members. Clinicians were asked whether they would recommend their hospital as a good place to work or to friends and family in need of medical care.39 The joyful workplace measure was assessed using the Mini-Z 2.0,40 a validated tool used to determine workplace satisfaction and wellness. Clinicians were classified as having a “joyful” current workplace if their score on the Mini-Z was 40 or greater (range, 10-50).

Interventions to Improve Clinician Well-Being

Clinicians were given a list of interventions generated from recommendations of the National Academy of Medicine2 and published research.41,42 Respondents selected the interventions that they thought would be most effective for alleviating burnout and improving clinician well-being.

Statistical Analysis

Responses from individual physicians and nurses were aggregated within hospitals to determine how much clinician outcomes, measures of patient care quality and safety, staffing adequacy, and management measures ranged across hospitals, and these hospital means were then averaged across all hospitals to obtain an overall mean for each of the measures. Descriptive statistics (percentages, ranges) were calculated separately for physicians and nurses. Coefficients from multilevel models were obtained by regressing individual-level measures of the odds of physician and nurse burnout, job dissatisfaction, and intent to leave on grand median-centered hospital-level measures of resources and management and the safety and quality reports used. To evaluate the size and significance of these associations in a way that was consistent with other parts of this report, we converted the odds ratios resulting from these models to probabilities at the median of the predictor and multiplied the probabilities by 100 to express the results as differences in percentages:

|

Because hospital turnover rates were provided at the hospital level, not the clinician level, ordinary least-squares regression models were used to estimate how physician and nurse turnover was affected by physician and nurse burnout, job dissatisfaction, and intent to leave. The coefficients from these regression models were further adjusted to indicate the differences in outcomes for physicians and nurses in hospitals at the 75th vs 25th percentiles of the different factors or independent variables or across similar ranges (eg, in hospitals at the 10th vs 60th percentile). We then described interventions that physicians and nurses reported as being the most and least important for improving their well-being.

Statistical tests were 2-tailed and P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. Data analyses were performed from February 21, 2022, to March 28, 2023, using Stata, release 17 (StataCorp LLC).

Sensitivity Analyses

Two sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the robustness of our findings under different model specifications. Using ordinary least-squares regression models with all variables (on both sides of the equations) aggregated to the hospital level (eTable 1 in Supplement 1), we found that coefficients from the ordinary least-squares models estimating the associations of clinician outcomes with hospital resources, management, and patient safety were comparable with the coefficients derived from multilevel models in the main analysis. The second sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine whether the coefficients would be different if we excluded the 7 hospitals that had an insufficient number of physician responses. We present only comparisons of nurse coefficients in the 53 vs 60 hospitals because the physician coefficients would be unchanged. Using Hausman test, we found no meaningful differences in the results (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

Results

The total sample comprised the survey responses of 15 738 nurses practicing in 60 hospitals and 5312 physicians practicing in 53 of the same hospitals. Participating hospitals had an average of 100 physicians and 262 nurses, and the overall survey response rate was 26%. The nurse-respondents had a mean (SD) age of 38.4 (11.7) years; approximately 69% were female, 8% male, and 22% unknown/other sex; 11% were Asian, 4% Black, 5% Hispanic, 53% White, 4% other or multiracial, and 23% did not provide data. The physician-respondents had a mean (SD) age of 44.7 (12.0) years; approximately 35% were female, 45% male, and 21% unknown/other sex; 16% were Asian, 4% Hispanic, 5% other or multiracial, 52% White, and 21% did not provide data.

Across hospitals, an average of one-third of the physician-respondents and one-half of the nurse-respondents reported experiencing high burnout. However, the percentage with high burnout in both groups ranged substantially across hospitals, from 9% to 51% for physicians and 28% to 66% for nurses (Table 1). More than 1 of every 5 physicians (23%) reported that they would leave their current hospital within the year if possible, and the range across hospitals for physicians (6%-43%) suggests that in some hospitals as many as 30% to 40% would leave if they could. Over 40% of nurses would leave their current hospital if possible. Actual turnover reported by participating hospitals reveals an overall turnover rate for physicians of 6% and 17% for nurses. More than 4 in 10 physicians and 5 in 10 nurses report a great deal of stress because of their job, and in some hospitals those percentages were as high as 62% and 74%, respectively. Problems with overall health and sleep were more characteristic of nurses than of physicians, and decidedly more common in some hospitals than in others.

Table 1. Clinician Well-Being and Reports of Patient Safety and Quality of Care Across Hospitals.

| Measure | Mean (range) across hospitals, %a | |

|---|---|---|

| Physicians in 53 hospitals | Nurses in 60 hospitals | |

| Survey respondents, No. | 5312 | 15 738 |

| Clinician well-being | ||

| High burnout | 32 (9-51) | 47 (28-66) |

| Job dissatisfaction | 15 (0-33) | 22 (2-48) |

| Intends to leave next year if possible | 23 (6-43) | 40 (21-69) |

| Turnover rate | 6 (0-49) | 17 (1-50) |

| Mental health | ||

| (i) High anxiety | 13 (0-25) | 25 (10-37) |

| (ii) Likely depressed | 9 (0-29) | 17 (7-26) |

| (iii) Exhibits PTSD related to COVID-19 | 4 (0-15) | 14 (3-27) |

| Morbidity includes i, ii, and/or iii | 18 (0-33) | 33 (18-48) |

| Great deal job-related stress | 43 (11-62) | 53 (35-74) |

| Work does not allow for personal/family life | 32 (0-67) | 18 (6-44) |

| Self-rated health is poor/fair | 29 (6-75) | 46 (29-62) |

| Self-rated quality of sleep is poor/fair | 51 (25-83) | 69 (50-88) |

| Clinician reports of patient safety and quality of care | ||

| Patient safety grade, poor (C, D, or F35) | 12 (0-40) | 26 (3-63) |

| Quality of care is poor/fair | 9 (0-30) | 16 (2-55) |

| Not confident patients can manage postdischarge care | 50 (25-78) | 53 (31-72) |

| Summary measure of poor culture of patient safety, average score of 6 | 21 (12-31) | 23 (10-31) |

| (i) Actions of management do not show that patient safety is a top priority | 13 (0-26) | 17 (3-45) |

| (ii) Clinicians feel mistakes are held against them | 33 (16-58) | 39 (11-50) |

| (iii) Patient information is lost during shift change when another is covering my patients | 26 (6-45) | 36 (19-52) |

| (iv) Do not feel free to question decisions or actions of authority | 29 (9-48) | 23 (3-41) |

| (v) Do not receive feedback about changes put into place based on event reports | 19 (4-31) | 16 (4-30) |

| (vi) Do not discuss ways to prevent errors from happening again | 9 (0-27) | 8 (0-19) |

Abbreviation: PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

Percentages are calculated at the hospital level, ie, the percentage of physicians with high burnout ranges from 9% in the hospital with the lowest percentage to 51% in the hospital with the highest percentage, and averages 32% across all hospitals. Poor culture of patient safety is the hospital average of 6 individual measures.

On patient safety, approximately 12% of physicians and 26% of nurses gave their hospital an unfavorable grade (C, D, or F), and for some hospitals more than one-quarter of the physician-respondents graded patient safety unfavorably. On average, 21% of physicians and 23% of nurses found fault with their hospitals’ culture of patient safety. One-third of physicians and 39% of nurses reported feeling their mistakes were held against them and 29% of physicians and 23% of nurses reported that they did not feel free to question authority. Although only 9% of physicians and 16% of nurses rated quality of care in their hospitals as poor or fair, in some hospitals those percentages rose to more than one-quarter of physicians and half of nurses. More than half of physicians and nurses across all hospitals and approximately three-quarters of both groups of clinicians in some hospitals were not confident that patients could manage their care after discharge.

Table 2 shows that 28% of physicians and more than half of nurses reported there were too few nurses. One-third of both physicians and nurses reported poor control over their workloads, and 39% of physicians and 63% of nurses reported a chaotic work environment. One of 5 physicians and one-third of nurses characterized the quality of their work environment as poor or fair. Approximately 42% of physicians and 47% of nurses reported lacking confidence that hospital management would resolve problems in patient care that clinicians identify, and close to one-third of physicians and half of nurses reported that the administration did not listen or respond to clinicians’ concerns. In some hospitals these percentages exceeded half of the clinicians. Less than 10% of clinicians described their workplace as joyful. Slightly more than 1 in 5 physicians and nurses reported not being involved in the internal governance of their hospital, and in some hospitals that problem was reported by approximately half of clinicians. Both groups of clinicians reported spending too much time on electronic health records (EHRs) and being frustrated by the task. On average across hospitals, close to 90% of physicians and nurses reported that professional relations between them were good and the majority reported that their care team worked efficiently together.

Table 2. Resources and Management Reported by Physicians and Nurses.

| Measure | Mean (range) across hospitals, %a | |

|---|---|---|

| Physicians in 53 hospitals | Nurses in 60 hospitals | |

| Survey respondents, No. | 5312 | 15 738 |

| Staffing | ||

| Not enough nurses to care for patients | 28 (0-57) | 54 (22-93) |

| My control over my workload is poor or marginal | 33 (13-51) | 36 (19-63) |

| Overall quality of work environment | ||

| Work environment is poor or fair | 20 (0-44) | 34 (8-64) |

| Work atmosphere is chaotic or tends to be chaotic | 39 (19-63) | 63 (36-86) |

| No clear philosophy of patient-centered care/nursing that pervades the clinical environment | 15 (0-33) | 20 (3-40) |

| Would not recommend hospital as a place to work | 13 (0-42) | 17 (1-57) |

| Would not recommend hospital to friends or family needing care | 7 (0-22) | 11 (0-35) |

| Joyful workplace | 9 (0-30) | 7 (0-20) |

| Management/clinician relations | ||

| Not confident management will act to resolve problems in patient care that clinicians identify | 42 (18-69) | 47 (14-74) |

| Administration does not listen or respond to clinician concerns | 29 (9-59) | 47 (6-77) |

| Do not agree my values are well aligned with management | 29 (0-48) | 33 (9-57) |

| Clinicians are not involved in internal governance of hospital | 23 (6-48) | 22 (6-55) |

| Lack freedom to make important patient care and work decisions | 14 (3-30) | 24 (9-45) |

| Professional relations | ||

| Physicians and nurses have good working relationship | 94 (80-100) | 89 (79-100) |

| Degree to which my care team works efficiently together is good/optimal | 74 (53-93) | 66 (54-87) |

| Electronic health records (EHRs) | ||

| Time spent on EHRs is moderately high to excessive | 74 (57-94) | 57 (37-72) |

| EHRs adds frustration to daily work | 62 (36-90) | 44 (20-71) |

Percentages are calculated at the hospital level, ie, the percentage of physicians who report that the work environment is “poor” or “fair” ranges from 0% in the hospital with the lowest percentage to 44% in the hospital with the highest percentage, and averages 20% across all hospitals.

Table 3 shows coefficients from multilevel models that regress hospital-level measures of physician and nurse outcomes (ie, burnout, job dissatisfaction, and intent to leave) on hospital-level measures of resources, management, and safety, after taking account of individual clinician differences in these outcomes. The hospital-level coefficients shown in Table 3 are percentage differences derived from odds ratios (described in the Statistical Analysis section previously) and indicate how different outcomes were for physicians and nurses in hospitals at the 75th rather than the 25th percentile of the independent variables (eg, resources). Hospitals characterized as having too few nurses, unfavorable work environments, and workloads that were beyond the control of clinicians had substantially more physicians and nurses who exhibited high burnout, job dissatisfaction, and intentions to leave their job. While the composite culture of patient safety scale appears to have little association with burnout of physicians, it does have a significant association with physician dissatisfaction and intent to leave and with all of the nurse outcomes. Significant effects shown in Table 3 are of substantive as well as statistical significance, given that they involve approximately 4% to 10% differences in job dissatisfaction and intent to leave for physicians in hospitals in which resource and management factors are at the 75th vs 25th percentile, and approximately 9% to 16% differences in all 3 outcomes for nurses.

Table 3. Coefficients From Multilevel Models Estimating the Differences in the Percentages of Clinicians With Various Outcomes (Burnout, Job Satisfaction, Intent to Leave) in Hospitals at the 75th vs 25th Percentiles of Resources, Management, and Patient Safety.

| Measure | Clinician outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician coefficients, % (95% CIs) | Nurse coefficients, % (95% CIs) | |||||

| Burnout | Job dissatisfaction | Intent to leave | Burnout | Job dissatisfaction | Intent to leave | |

| Not enough nurses to care for patients (physician IQR, 16.8%-36.8%; nurse IQR, 40.6%-67.9%) | 3.5 (0.2 to 7.1)a | 4.8 (2.0 to 8.0)b | 6.9 (4.1 to 9.9)b | 11.5 (9.0 to 14.0)b | 12.7 (10.3 to 15.3)b | 16.2 (13.2 to 19.1)b |

| Control over workload is poor/marginal (physician IQR, 23.5%-40.6%; nurse IQR, 29.7%-42.2%) | 10.1 (6.7 to 13.6)b | 7.1 (3.2 to 11.5)b | 8.9 (4.9 to 13.3)b | 9.4 (7.3 to 11.6)b | 10.8 (8.9 to 12.7)b | 13.7 (11.3 to 16.2)b |

| Not confident that management will resolve problems (physician IQR, 33.3%-51.7%; nurse IQR, 40.2%-53.9%) | 6.5 (3.3 to 9.8)b | 6.6 (3.6 to 10.0)b | 6.1 (2.8 to 9.6)b | 9.3 (7.2 to 11.2)b | 10.5 (8.6 to 12.3)b | 11.7 (9.0 to 14.3)b |

| Work environment is poor/fair (physician IQR, 13.5%-26.4%; nurse IQR, 24.8%-40.8%) | 6.7 (3.5 to 10.0)b | 9.7 (7.6 to 12.2)b | 10.7 (8.1 to 13.3)b | 11.2 (9.3 to 13.1)b | 12.2 (10.7 to 13.6)b | 14.7 (12.3 to 17.2)b |

| Culture of patient safety average of 6 itemsc (physician IQR, 18.6%-23.6%; nurse IQR, 19.5%-25.8%) | 2.4 (−0.5 to 5.5)d | 5.9 (3.3 to 8.9)b | 5.4 (2.5 to 8.5)b | 9.8 (6.9 to 12.7)b | 11.5 (8.5 to 14.8)b | 12.8 (9.1 to 16.6)b |

P = .04

P < .001.

The 6 items in the summated culture of patient safety measure include (1) disagree patient safety is a priority, (2) agree that mistakes are held against staff, (3) agree that important information is lost during shift changes, (4) disagree that they feel free to question authority, (5) disagree that feedback about changes are put into place based on event reports, and (6) disagree that they discuss ways to prevent errors from happening again.

P = .11

Table 4 shows that both physician and nurse turnover were significantly associated with nurse burnout, nurse dissatisfaction, and nurses’ intentions to leave their current job. Physician turnover was approximately 4% to 5% higher and nurse turnover was 5% to 8% higher in hospitals in which nurse burnout rates, nurse job dissatisfaction rates, and the percentage of nurses that intended to leave were at the 75th vs the 25th percentile; physician burnout, dissatisfaction, and intent to leave were not associated with physician or nurse turnover.

Table 4. Coefficients Estimating the Differences in Clinician Turnover in Hospitals at the 75th vs 25th Percentiles for Burnout, Job Satisfaction, and Intent to Leave.

| Measure | IQR, % | Physician turnover | Nurse turnover | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | P value | % (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Burnout rate | |||||

| Physicians | 28.8 to 37.0 | 0.7 (−2.6 to 3.9) | .69 | 0.6 (−3.1 to 4.2) | .76 |

| Nurses | 38.7 to 53.4 | 3.9 (0.1 to 7.7) | .046 | 5.1 (0.2 to 9.9) | .04 |

| Job dissatisfaction rate | |||||

| Physicians | 9.4 to 20.0 | 2.7 (1.7 to 7.1) | .23 | 3.9 (−1.5 to 9.2) | .16 |

| Nurses | 15.1 to 26.4 | 5.2 (1.8 to 8.6) | .004 | 5.4 (1.5 to 9.3) | .007 |

| Intent to leave rate | |||||

| Physicians | 17.0 to 28.4 | 0.9 (−4.1 to 5.9) | .73 | 3.7 (−2.2 to 9.5) | .22 |

| Nurses | 31.5 to 48.9 | 5.2 (1.1 to 9.2) | .013 | 8.4 (3.9 to 13.0) | < .001 |

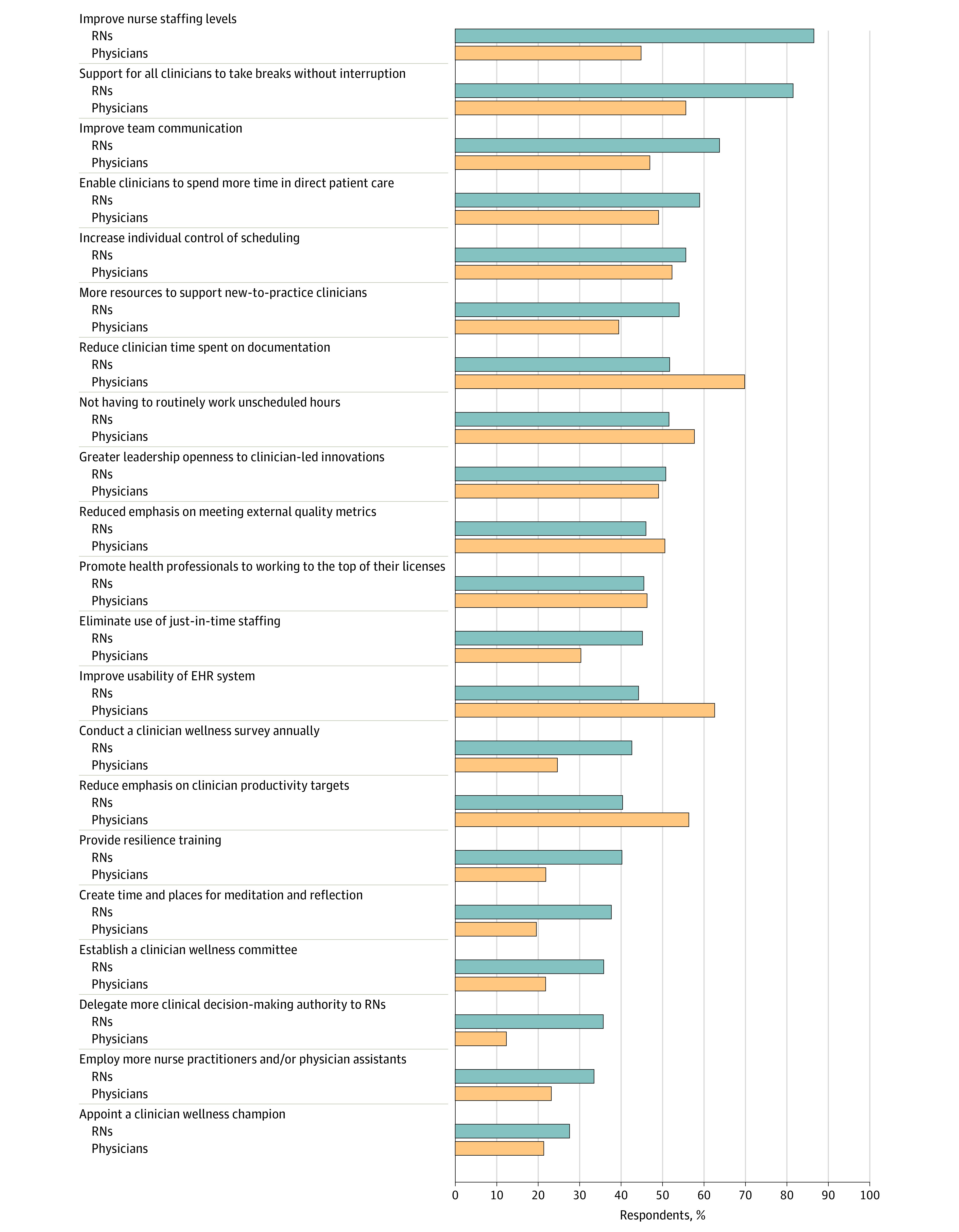

Physicians and nurses were asked to select from a list of interventions those that they judged would be most effective in reducing burnout and improving their well-being. Responses from individual physicians and nurses were aggregated within hospitals as well as reported as percentages among all respondents across hospitals (Figure). The first 9 of the interventions were viewed as important by half or more of the nurses, including the 2 interventions that most nurses said would be important: improving nurse staffing levels and supporting clinicians in taking breaks without interruption. Physicians agreed that adequate nurse staffing and breaks without interruption were important to their well-being; they ranked reducing time spent on documentation and not having to routinely work unscheduled hours as “very important”; nurses agreed these were important to them as well. More resources to support new-to-practice clinicians were ranked highly by more than half of nurses and 39% of physicians. Poor EHR usability annoyed both physicians and nurses, and both groups wanted more individual control over scheduling. Half or more of physicians wanted reduced emphasis on meeting external quality metrics and clinician productivity targets. Notably, currently popular interventions adopted by management were not ranked as important by most clinicians, including clinician wellness champions, resilience training, and quiet places.

Figure. Interventions that Physicians and Nurses Ranked as “Very Important” to Improving Their Well-Being.

Percentages of physicians (yellow) and nurses in (blue) who responded “very important” to an intervention that could improve their well-being.

Discussion

We provide detailed empirical evidence of substantial work-related health, mental health, and personal work-life balance challenges experienced by physicians and nurses in hospitals even at Magnet hospitals that have been formally recognized as being good places to work. Fewer than 10% of clinicians experienced joy in their hospital practices. Per our study findings, one-third of physicians and close to half of nurses are experiencing high burnout. One-third of physicians and one-half of nurses rate their own health as fair or poor. Physicians scored substantially worse than nurses on work-life balance, which was also a problem for 32% of physicians. Because the US Clinician Wellbeing Consortium is part of a 6-country European project to improve work environments,17 we found it notable that the US Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education partially addressed this problem in 2003 by limiting physician resident work hours to 80 per week while the EU limits physician resident work hours to 48 per week.

Hospitals that physicians and nurses characterized as having too few nurses, unfavorable work environments, and workloads that were beyond the control of clinicians had significantly more physicians and nurses that exhibited high burnout, job dissatisfaction, and intentions to leave their current job. For physicians, whether they have control over their workload was shown to be of paramount importance regarding level of burnout. For nurses, the factors of greatest importance to burnout were sufficiency of nurse staffing and quality of the work environment. Close to 90% of physicians and nurses reported that professional relations between them were good, and most reported that their care teams worked efficiently together. These findings hold promise for clinicians acting together to bring about important changes in their work environments. However, clinicians need management support for change, and our findings on clinician-management relations were concerning. Close to half of physicians and nurses were not confident that management would act to resolve problems that clinicians identify in patient care, and close to one-third of clinicians reported that their values were not well aligned with those of management. These are surprising findings in Magnet hospitals given that these issues may be even more pronounced in non-Magnet hospitals.6

The culture of patient safety is not usually discussed in the context of clinician well-being; however, our study found it to be significantly associated with physician dissatisfaction and intent to leave and with all nurse outcomes. The key tenets embraced in the culture of patient safety described 2 decades ago by the Institute of Medicine require close collaboration and trust between clinicians and management. This relationship seems to be lacking, as evidenced by the more than one-third of clinicians who reported that their errors were being held against them, and the 13% of physicians and 17% of nurses reporting that actions of management did not demonstrate that patient safety is an organizational priority.43

Both physicians and nurses prioritized interventions that influenced their ability to provide effective patient care over interventions focused on clinician wellness. Among their priority choices were improved nurse staffing (highly ranked by 45% of physicians and 87% of nurses) and improved work environments, including scheduled breaks without interruptions, not working unscheduled hours, more control over scheduling, and additional resources devoted to new-to-practice clinicians. Improving EHR usability and reducing emphasis on meeting external quality metrics were among the more highly ranked initiatives. Clinician wellness and resilience programs were ranked lowest, although they tended to be more commonly implemented than actions to improve clinicians’ working conditions. Research shows that physicians do not have a deficit in resilience but still experience job-related burnout, suggesting that other solutions are required.14

Limitations

The study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic when clinician well-being was likely worse than previously, although research showed high rates of clinician burnout before the pandemic.2,7 Hospitals were Magnet-recognized and not representative of all hospitals (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). A similar simultaneous study of representative hospitals showed that nurse well-being and quality and safety assessments were significantly worse in non-Magnet hospitals.6 This study was cross-sectional, so caution is warranted in assuming causality. Lower response rates for email surveys are increasingly common and worsened during the pandemic.44,45,46 Our prior research18 using nurse surveys reveals no differences between respondents and resurveyed nonrespondents in the items studied. Other research surveying physicians have yielded lower response rates than this study.14 We used clinicians’ assessments of patient care quality and safety; previous research shows that clinician reports of patient quality are highly associated with independently measured patient outcomes.34

Conclusions

This cross-sectional survey study found that physicians and nurses practicing in hospitals are under substantial stress, even in institutions known to be good places to work, which threatens the retention and vitality of the hospital workforce and patient safety. Clinicians report a lack of confidence in hospital management to act to resolve problems in patient care and to create supportive work environments and a work culture that promotes patient safety. Clinicians want improvements in nurse staffing and working conditions to address burnout and job dissatisfaction.

eTable 1. Coefficients from Ordinary Least Square Regression Models Estimating the Differences in the Percentages of Clinicians with Various Outcomes (Burnout, Job Satisfaction, Intent to Leave) in Hospitals at the 75th vs. 25th Percentiles of Resources, Management and Patient Safety

eTable 2. Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Nurse Coefficients from 53 vs 60 Study Hospitals using Ordinary Least Square Regression Models to Estimate the Differences in the Percentages of Clinicians with Various Outcomes (Burnout, Job Satisfaction, Intent to Leave) in Hospitals at the 75th vs. 25th Percentiles of Resources, Management and Patient Safety

eTable 3. Characteristics of Magnet and Non-Magnet Hospitals

Nonauthor Collaborators. US Clinician Wellbeing Study Consortium

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Murthy VH. Confronting health worker burnout and well-being. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(7):577-579. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2207252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: a Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. The National Academies Press; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Hospital Association . AHA urges Congress to address health care workforce challenges. AHA News. Accessed January 3, 2023. https://www.aha.org/news/news/2022-03-02-aha-urges-congress-address-health-care-workforce-challenges

- 4.Muoio DLA. County’s tentative labor deal heads off 1,300-physician strike at 3 public hospitals. Fierce Healthcare. Accessed January 3, 2023. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/providers/la-countys-tentative-labor-deal-heads-1300-physician-strike-3-public-hospitals

- 5.Gooch K. US healthcare workers walk off the job: 18 strikes in 2022. Accessed January 3, 2023. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/hr/us-healthcare-workers-walk-off-the-job-18-strikes-in-2022november9.html

- 6.Aiken LH, Sloane DM, McHugh MD, Pogue CA, Lasater KB. A repeated cross-sectional study of nurses immediately before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for action. Nurs Outlook. 2022:101903. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4204396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lasater KB, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, et al. Chronic hospital nurse understaffing meets COVID-19: an observational study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2021;30(8):639-647. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2020-011512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shanafelt TD. Physician well-being 2.0: where are we and where are we going? Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(10):2682-2693. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians during the first 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97(12):2248-2258. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah MK, Gandrakota N, Cimiotti JP, Ghose N, Moore M, Ali MK. Prevalence of and factors associated with nurse burnout in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2036469. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prasad K, McLoughlin C, Stillman M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of stress and burnout among US. healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cross-sectional survey study. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;35:100879. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linzer M, Jin JO, Shah P, et al. Trends in clinician burnout with associated mitigating and aggravating factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(11):e224163. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.4163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kutney-Lee A, Stimpfel AW, Sloane DM, Cimiotti JP, Quinn LW, Aiken LH. Changes in patient and nurse outcomes associated with magnet hospital recognition. Med Care. 2015;53(6):550-557. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Resilience and burnout among physicians and the general US working population. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e209385. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buchan J, Catton H. Recover to Rebuild: Investing in the Nursing Workforce for Health System Effectiveness. International Council of Nurses; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McHugh MD, Kelly LA, Smith HL, Wu ES, Vanak JM, Aiken LH. Lower mortality in magnet hospitals. J Nurs Adm. 2013;43(10):S4-S10. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000435145.39337.d5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sermeus W, Aiken LH, Ball J, et al. ; Magnet4Europe consortium . A workplace organisational intervention to improve hospital nurses’ and physicians’ mental health: study protocol for the Magnet4Europe wait list cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2022;12(7):e059159. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lasater KB, Jarrín OF, Aiken LH, McHugh MD, Sloane DM, Smith HL. A methodology for studying organizational performance. Med Care. 2019;57(9):742-749. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2(2):99-113. doi: 10.1002/job.4030020205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):397-422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schlak AE, Aiken LH, Chittams J, Poghosyan L, McHugh M. Leveraging the work environment to minimize the negative impact of nurse burnout on patient outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):610. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Welp A, Meier LL, Manser T. Emotional exhaustion and workload predict clinician-rated and objective patient safety. Front Psychol. 2015;5:1573. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cimiotti JP, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Wu ES. Nurse staffing, burnout, and health care-associated infection. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40(6):486-490. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.02.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White EM, Aiken LH, McHugh MD. Registered nurse burnout, job dissatisfaction, and missed care in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(10):2065-2071. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M, Schaufeli W, Schwab R. Maslach Burnout Inventory. Vol 21. Consulting Psychologists Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dyrbye LN, Meyers D, Ripp J, Dalal N, Bird SB, Sen S. A pragmatic approach for organizations to measure health care professional well-being. National Academy of Medicine. Published online October 1, 2018. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://nam.edu/a-pragmatic-approach-for-organizations-to-measure-health-care-professional-well-being/

- 27.McHugh MD, Kutney-Lee A, Cimiotti JP, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. Nurses’ widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout, and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(2):202-210. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Monahan PO, Löwe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):317-325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Crengle S, et al. Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(4):348-353. doi: 10.1370/afm.1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prins A, Bovin MJ, Smolenski DJ, et al. The primary care PTSD screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(10):1206-1211. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3703-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lefante JJ Jr, Harmon GN, Ashby KM, Barnard D, Webber LS. Use of the SF-8 to assess health-related quality of life for a chronically ill, low-income population participating in the Central Louisiana Medication Access Program (CMAP). Qual Life Res. 2005;14(3):665-673. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-0784-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193-213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McHugh MD, Stimpfel AW. Nurse reported quality of care: a measure of hospital quality. Res Nurs Health. 2012;35(6):566-575. doi: 10.1002/nur.21503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://www.ahrq.gov/sops/surveys/hospital/index.html

- 36.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288(16):1987-1993. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lake ET. Development of the practice environment scale of the Nursing Work Index. Res Nurs Health. 2002;25(3):176-188. doi: 10.1002/nur.10032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lake ET, Sanders J, Duan R, Riman KA, Schoenauer KM, Chen Y. A meta-analysis of the associations between the nurse work environment in hospitals and 4 sets of outcomes. Med Care. 2019;57(5):353-361. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aiken LH, Sermeus W, Van den Heede K, et al. Patient safety, satisfaction, and quality of hospital care: cross sectional surveys of nurses and patients in 12 countries in Europe and the United States. BMJ. 2012;344:e1717. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Linzer M, McLoughlin C, Poplau S, Goelz E, Brown R, Sinsky C; AMA-Hennepin Health System (HHS) burnout reduction writing team . The Mini Z worklife and burnout reduction instrument: psychometrics and clinical implications. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(11):2876-2878. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07278-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brooks Carthon JM, Hatfield L, Brom H, et al. System-level improvements in work environments lead to lower nurse burnout and higher patient satisfaction. J Nurs Care Qual. 2021;36(1):7-13. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516-529. doi: 10.1111/joim.12752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Donaldson MS, Corrigan JM, Kohn LT. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tourangeau R, Plewes T, eds. Nonresponse in Social Science Surveys: A Research Agenda. National Academies Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ward BW, Sengupta M, DeFrances CJ, Lau DT. COVID-19 pandemic impact on the national health care surveys. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(12):2141-2148. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spetz J, Cimiotti JP, Brunell ML. Improving collection and use of interprofessional health workforce data: progress and peril. Nurs Outlook. 2016;64(4):377-384. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Coefficients from Ordinary Least Square Regression Models Estimating the Differences in the Percentages of Clinicians with Various Outcomes (Burnout, Job Satisfaction, Intent to Leave) in Hospitals at the 75th vs. 25th Percentiles of Resources, Management and Patient Safety

eTable 2. Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Nurse Coefficients from 53 vs 60 Study Hospitals using Ordinary Least Square Regression Models to Estimate the Differences in the Percentages of Clinicians with Various Outcomes (Burnout, Job Satisfaction, Intent to Leave) in Hospitals at the 75th vs. 25th Percentiles of Resources, Management and Patient Safety

eTable 3. Characteristics of Magnet and Non-Magnet Hospitals

Nonauthor Collaborators. US Clinician Wellbeing Study Consortium

Data Sharing Statement