Abstract

Current digital health approaches have not engaged diverse end users or reduced health or healthcare inequities, despite their promise to deliver more tailored and personalized support to individuals at the right time and the right place. To achieve digital health equity, we must refocus our attention on the current state of digital health uptake and use across the policy, system, community, individual, and intervention levels. We focus here on a) outlining a multi-level framework underlying digital health equity, b) summarizing five types of interventions/programs (with example studies) that hold promise for advancing digital health equity, and c) recommending future steps for improving policy, practice, and research in this space.

Keywords: Digital health, health equity, social determinants of health, health technology

Introduction

Digital health is now foundational to both public health and medicine, given that online and mobile platforms are central to accessing public health information and resources as well as delivery of healthcare services.(2) Because of the diffusion of digital approaches in all aspects of health, we use a broad definition of digital health for this paper: “Digital health connects and empowers people and populations to manage health and wellness, augmented by accessible and supportive provider teams working within flexible, integrated, interoperable and digitally-enabled care environments that strategically leverage digital tools, technologies and services to transform care delivery.”(89)

Within the field of digital health, it is also known that there are disparities in both uptake and effectiveness of tools and platforms – with a range of evidence across settings and conditions.(60, 77) More specifically, it has long been known that new innovations or programs can exacerbate underlying health disparities, as outlined in the “inverse care law” that describes how well-resourced individuals are better positioned to be aware of and take up these interventions before less-resourced individuals, thereby widening gap(s) in health outcomes.(94) Not only is this misaligned with our goals of health equity, but it also reduces our ability to make population-level health impact with digital health tools by limiting the reach of platforms to individuals and communities who might benefit the most from our solutions.(81) Thus, centering digital health equity as a primary goal within the field is critical to interrupt this cycle and reframe how we design, implement, evaluate, and spread digital health tools.(35)

This paper has three objectives to advance digital health equity: 1) outlining what is known about the current state of digital health access and use among marginalized populations across critical levels of influence (policy, system, community, individual, and intervention), 2) focusing in on five sets of interventions that hold promise for addressing disparities across these domains, and 3) generating a set of future recommendations for public health and healthcare researchers and practitioners.

Outlining multi-level framework for digital health equity

First, we review here key literature and statistics that shape the current state of digital health use and existing barriers. We focus primarily on the United States within this summary, given the specific policy, organizational, and social structures in place, but believe the evidence also easily extends to other high and middle-income nations worldwide. To outline the multiple levels of influence on digital health equity, we were guided by the Socio-Ecological Model and the Technology Acceptance Model to frame the evidence.(23, 64) More specifically, we expand here on evidence within five levels of influence that have been consistently linked to digital health disparities: policy/structural drivers, system-level influences (such as public health and healthcare settings), community/social factors (such as the role of family/friends as well as community-based organizations), individual influences (such as skills and motivation), and finally the characteristics of the digital platforms themselves (such as usability and accessibility).

Policy and Structural Determinants

At the most foundational level, it is clear that societal structures and policies are key determinants of digital health disparities. These structures influence digital health equity and the potential reach of digital health tools by limiting implementation, dissemination, and access to technology in already marginalized communities. In 2021, nearly 1 in 4 Americans still did not have home broadband connections to enable high-speed Internet access, and nearly 1 in 6 Americans still did not own a smartphone, with clear inequities by income, age, and race/ethnicity.(74) Even among those with home broadband or a smartphone, about a quarter worry about being unable to afford their Internet and cellphone bills over the next few months.(63) For those who rely on federal assistance to access critically needed smartphones, the significant technical shortcomings of the Lifeline program -- which provides low-income individuals with discounts on voice or broadband Internet service -- including poor service coverage and limited monthly minutes, limit the usefulness of the program for the millions of Americans who could benefit.(79)

In addition, in the U.S. there are no current federal regulations in place to prevent preferential installation of fiber broadband by Internet service providers only in high-income communities, thereby limiting access to high-speed internet needed for in low-income communities. This practice is known as ‘digital redlining’ and parallels 20th century U.S. federal, state, and local housing policies that mandated racial segregation. (25) As health care delivery increasingly relies on digital tools requiring access to high-speed internet, the end result is that digital redlining ultimately limits care access and exacerbates health inequities in communities with already poorer health outcomes. For example, one recent study found that limited Internet access in communities was associated with higher rates of COVID-19 mortality. (53)

There has been increased focus on increasing access to high-speed Internet for all Americans, most notably through the Affordable Connectivity Program, a long-term $14 billion federal program for discounted broadband and computing devices enacted under the Infrastructure Act of 2022, and through renewal of a federal waiver for expanded eligibility of the long-standing Lifeline program. However, there are no structural or policy mechanisms that link broadband or other Internet service provision with health initiatives or health care service delivery, (79)even though it is becoming clearer that digital access is a foundational social determinant of health. Even more broadly, linking the policies involving determinants of health, such as utilizing a “health in all policies” approach,(80) might better connect concepts of digital access and inclusion and health in the future.

Systems-level Determinants

To achieve digital health equity, there must also be healthcare and public health system investment, given how critical these systems are in supporting individuals and communities in managing their health. Within these settings, digital equity requires availability of resources and a robust technical infrastructure. However, there is variable capacity within publicly funded systems to drive digital innovation, with settings such as safety net healthcare and social service settings least likely to have the digital infrastructure and staffing to support digital health innovation and/or implementation.(5, 99) Collectively, these public health and healthcare systems are the most likely to serve marginalized communities in the U.S., such as individuals with low income and those from racial/ethnic and linguistic minority groups.(20, 43) As was brought to light during the COVID-19 pandemic, there is severe underinvestment in the public health throughout the United States,(17, 32) with clear needs for digital supports such as electronic data sharing between public health and clinical settings, digital communication with the public, and advanced technologies to support disease monitoring and reporting. Similarly, many public and community-based healthcare systems were unable to leverage more sophisticated features of their electronic health records (EHRs) and other data systems to respond to the pandemic,(46) resulting in disparities by socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity in the uptake of critical digital healthcare services such as video-based telemedicine encounters.(1)

There are also system-level funding barriers in the private healthcare sector that can drive digital health inequities. For example, private funding of digital health companies (e.g., mobile apps, devices/wearables) has grown exponentially within the past decade, up to a trillion-dollar investment, yet there are stark differences in which type of digital health products are brought to market and which entrepreneurs receive funding. Entrepreneurs of color and those developing digital platforms to support complex medical and social needs continue to receive the smaller portions of funding.(3, 100) For example, Latinx- and Black-founded companies only account for 2% and 1.3% of overall startup investments, respectively.(62, 97)

In addition to having sufficient funding and infrastructure, public health and healthcare systems require leadership and culture that supports innovation to achieve digital health equity.(86) For example, health system leadership must jointly prioritize health equity and innovation to achieve digital health equity. Often metrics for innovation success do not include an equity perspective, such as digital implementation of new platforms or services without clear goals for uptake among domains such as race/ethnicity, language proficiency, or age.(52, 70, 87) Lack of coordination between health equity leaders and digital or innovation leaders can impede progress towards digital health equity.(26, 56, 57) (87)

Finally, local skills to develop and implement digital approaches vary widely among health and healthcare systems. To pursue digital health equity, the front-line workforce must be adaptable and receptive to changes in workflow that come with new digital tools. Because digital tools often support ongoing work (such as in-person visits or service provision), it is vital to redesign workflows when improving existing digital infrastructure to get the most value from implementation.(86) If properly integrated, digitally enabled workflows can help health systems maximize efficiencies, enhance the quality and safety of services, and improve care coordination. To complement these workflows, there must also be aligned reimbursement and incentives from payers to support and reinforce this work.(95) Implementation gaps can arise when skills or support for developing workflows are insufficient—and this is particularly true in settings serving marginalized communities who might need additional time and/or support to take up digital platforms.

Community/Social-Level Determinants

At the next level, there are social relationships that clearly influence the success of digitally enabled health and healthcare interventions.(93) This domain is built upon decades of public health research that document social influences on the effectiveness of any intervention or program.(9) Furthermore, it cannot be overstated that community and social factors play a particularly important role in reducing health inequities.(102) This is because societal structural barriers and historic injustices have specifically created barriers for many communities, underscoring the need for all digital health programs and interventions to focus on trustworthiness and usefulness within their work, which are deeply rooted in social connections and context.(16)

At the most foundational level within this community/social domain, there is a need to better understand how communities prioritize digital health platforms and programs to support health and wellness. It is critical to co-develop digital health solutions with marginalized communities often excluded from digital health research or implementation,(13, 28) starting with designing for topics that are most relevant to be addressed. Because digital health programs are often attempting to optimize or enhance existing resources or services, it is critical to ensure that digital platforms are viewed as acceptable, important, and timely from the outset.(109)

Next, even after the design is complete, social influences have a clear role in establishing both awareness and trust of the digital health platform. At a local level, there are many community-based organizations that are critical to spreading any health program within their communities,(69) and these groups should be considered as core partners in the digital health ecosystem. For example, community-based organizations are intricately tied to health and wellness within specific neighborhoods or racial/ethnic or cultural groups, and digital health programs that build from these existing relationships will be much better positioned to make an impact.(21, 49)

Finally, considering one-on-one interpersonal interactions within this domain, there are multiple relationships that influence both the use and the effectiveness of digital health solutions. The supportive accountability model helps to define how coaches and others support improves adherence through trustworthiness, benevolence, and expertise,(65) ranging or adapting from technical support to emotional support to expert support. There is existing literature on the broad (but often overlooked) impact of caregivers on health outcomes, and additional evidence on the importance of loved ones in learning or trying new digital programs. This research also extends beyond family and friends, with evidence about the role of trusted healthcare relationships (such as doctors and clinicians,(68, 108) or community health workers(73) or peers(34)) to recommend or assist with health interventions. Therefore, any assumptions or descriptions about digital health solutions ‘replacing’ in-person programs should be phased out for the more appropriate framing of blending human and digital support to achieve the greatest impact while also improving reach and efficiency.(50)

Individual-Level Determinants

At the individual level, there is more extensive behavioral research on digital health use and effectiveness. An individual’s access to devices and data/Internet, as described above, are core drivers of digital health equity, given their foundational influence on who is able to take advantage of digital services and communication from the outset. Yet even with universal access to digital devices and data, there are skills and motivational components at the individual level that must also be considered(23) -- related to skills, usefulness, and acceptance of digital health tools.(31)

One core aspect that emerges from the literature is related to the skills needed to use digital tools and platforms. UNESCO defines digital literacy as the “the ability to access, manage, understand, integrate, communicate, evaluate and create information safely and appropriately through digital devices and networked technologies for participation in economic and social life.”(4) This includes both cognitive and technical skills. It is well documented that individuals’ digital literacy skills play a crucial role in adoption of digital health interventions.(11, 29) As stated above, when individuals are socially connected, they may also experience greater ease of use and reduced barriers to uptake from a support network.(22, 40)

The usefulness of any digital health tool is also impacted by an individual’s motivation. Individuals with worse health status who are unable to get their health needs addressed through other means may have greater motivation and interest in using digital health tools.(71, 75) Health literacy (aside from digital literacy) can also impact whether individuals gain as much utility from using a digital health tool. For example, individuals with lower health literacy have greater challenges seeking and using online health information(8, 27, 61, 107); therefore, even if the user has adequate digital literacy skills, limited health literacy can impact usefulness of a digital tool.(107)

Individual acceptance of the digital tool is affected by factors beyond ease of use and usefulness. One important factor is trust in the digital tool developer or whoever is recommending the digital health tool.(14) Studies have shown that adoption of digital health tools, such as patient portals, are impacted by clinician recommendations and trust in their primary care clinicians.(58) Beyond trust, studies have found individuals vary in their concerns about the privacy and security of their personal data,(48) especially when it is unclear where data was stored and who had access to data.

Digital Health Intervention-level Determinants

At the final level of influence, there are several features within the digital platforms themselves that can support broader use across diverse end users. From the outset, it is critical that the digital health products are leveraging approaches to ensure language and literacy accessibility in their platforms. For example, there is a dearth of digital health apps in either iOS or Android formats that are available in fully translated versions to support non-English speaking populations. (67, 78) Furthermore, there are clear guidelines for improving the readability of content that can be adopted, such as writing text at less than 6th grade reading level and complementing written text with audiovisual features to support comprehension. (12, 54)

Digital tools must also be straightforward and usable. Many users report feeling overwhelmed by the time it takes to review large quantities of health information as well as vetting the varying quality of health information and apps.(92) In addition, digital health platforms are varied in the elements they employ as well as the complexity of the programs, from employing basic tools such as one-way text messaging, to engaging in conversations with chatbots that employ artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms, to using wearables or apps to collect data about user behavior and/or track health behaviors. These levels of complexity may themselves present challenges to use among certain populations, especially as they require active data entry or engagement from users.(82)

Relatedly, many existing digital health features have not been explicitly designed to be usable for people with lower levels of digital literacy. Typically, the more features that a platform has, the more difficult it is for users of all background literacy levels (health and digital) to use.(82) Therefore, it is crucial to integrate inclusive design methods that emphasize equity, simplicity, tolerance for error, and scaffolding approaches.(106) Similarly, digital design must be completed in different digital environments and devices as well as for varying levels of Internet speed and availability. Identifying user needs and abilities to shape digital interventions can greatly increase the relevance in people’s lives.(55)

Key intervention examples to address digital health equity determinants

Given these existing multi-level influences on digital health equity, there are many considerations when planning a public health or healthcare digital intervention to support inclusive and equitable uptake and effectiveness. Although it may not be possible to address all levels of influence in each digital intervention or program, previous work provides insights on how best to develop, implement, and evaluate digital health interventions across more than a single level of influence. In this section, we present evidence from both the peer-reviewed and the grey literature that center around five major types of interventions or programs to advance digital health equity.

Interventions that employ digital health co-design to advance equity in usability, uptake, and/or effectiveness of digital health platforms

Interventions that provide individual-level digital literacy support or training as a core program component

Digital programs that leverage community/social relationships to support use

Systems-level implementation of digital interventions or programs, specifically within safety net settings

Policies/programs that addressed structural barriers to digital health interventions, such as broadband access or devices

The examples within this section are also summarized in the Table. The included studies: a) utilized a multi-level digital intervention and/or implementation approach, b) focused explicitly on health equity within the study population/setting or the digital intervention or program itself, and/or c) employed novel or rigorous methods/processes that increased the generalizability of the work.

Table.

Example studies addressing digital health equity

| Study | Study setting | Primary objective of digital platform/ intervention | Study design / outcome (s) | Key findings/lessons for digital health equity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Interventions/Programs that employ digital health co-design to advance equity in usability, uptake, and/or effectiveness of digital health platforms | ||||

| Papoutsi et al., 2021 | Nationwide in the U.K. | Compare co-design in 3 case studies | Workshops with patients as well as providers to obtain feedback on tools. Pilot testing. | If co-design focuses narrowly on the technology, opportunities will be missed to coevolve technologies alongside clinical practices and organization routines. |

| Brewer et al., 2020 | African American churches, Rochester and Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN, U.S. | Engage the community to develop a general health app | CBPR: Community members involved in the mixed methods study design to incorporate community members in intervention development. FAITH! Partners designated to refine recruitment, implementation, and results dissemination |

Leveraged established stakeholders and trusted social networks Focused on understanding the social context of potential end users Integrated community engagement through user-centered design or participatory design Gain an understanding of community partner technology infrastructure |

| Buman et al., 2013 | Three senior, low-income housing sites, South San Francisco, Menlo Park, San Mateo, CA, U.S. | Develop and evaluate the utility of a computerized, tablet-based participatory tool designed to engage older residents in identifying neighborhood elements that affect active living opportunities | Formative testing. Participants used tool to record common walking routes and geocoded audio narratives and photographs of the local neighborhood environment while navigating their usual walking route | Tool was found to complement other assessments and can assist decision makers in consensus-building processes for environmental change |

| Jackson et al., 2022 | Prince George’s and Montgomery Counties, Maryland, U.S. | Design a prevention-focused, personalized mHealth, information-seeking smartphone app that is culturally appropriate and acceptable | 1-year, multi-method participatory research process that engaged English-speaking African American and bilingual or Spanish-speaking Hispanic adults | Community partnerships provided the chain of trust that help Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) participants feel comfortable participating in app research. Community-based participatory research principles yielded promising results to engage these populations in digital health research Interactive design sessions uncovered participants’ needs and development opportunities for digital health tools. Multiple design sessions with different methods provided an in-depth understanding of participants’ preferences and needs. |

| Avila et al., 2019 | Safety-net hospital, San Francisco, CA, U.S. | Inform development of text-messaging intervention to encourage physical activity | Focus group and individual interviews with English- and Spanish-speaking patients to integrate user feedback into intervention design | Key barriers to use (pain and depression) were identified and addressed in intervention, alongside technical requirements |

| Nouri et al., 2019 | Public sector urban primary care clinics, San Francisco, CA, U.S. | Assess relevance of user-centered methods for diverse patient pool | Semi-structured interviews, coding, and card sorting | Engagement in design methods varied by digital and health literacy Augmentation of card sorting with direct observation and audiovisual cues may be more productive in eliciting feedback for those with communication barriers |

| Unertl et al., 2016 | US and Canada. Projects using CBPR | Case analysis of 5 studies implementing community-based participatory research (CBPR) in health informatics work | Examined each case individually for success factors and barriers, and identified common patterns across cases | CBPR projects resulted in more relevant products that match community need. Challenges exist including longer time frame and mismatch in style and culture. |

| 2. Example studies that provide individual-level digital literacy support or training as a core program component | ||||

| Hoffman et al., 2020 | Boston, MA, U.S. | Identify digital resources for hospitalized patients with serious mental illness to increase wellness, make informed decisions about apps, and use apps and data for behavior change | Exploratory group evaluation of apps culminating into the development of two training manuals | Wide range of starting digital skills. Group training requires flexibility to meet participants at current digital literacy level Training can increase perception on importance of using digital tools to access health information and confidence in finding health information online |

| Lyles et al., 2019 | Safety-net clinics, San Francisco, CA, U.S. | Increase patient portal enrollment | Pre- and post-evaluation of effectiveness of in-person training vs web-based videos about patient portal navigation | Both in-person and web-based videos were better than no training However nearly 80% did not log-in after training, suggesting need for very intense training or significant improvement in usability of patient portals |

| Watkins and Xie, 2014 | N/A (review article) | Studies aiming to increase eHealth literacy | Systematic review. Collaborative learning and tailored content developed based on NIH materials (both in-person and web-based) |

Few evaluations of health outcomes Few theory-based interventions Few experimental study designs |

| Lee et al., 2014 | N/A (review article) | Studies aiming to increase ability to find reliable health information (workshops most common approach) | Review of in-person and web-based trainings, both group and individual sessions | Overall increases in self-reported knowledge and/or skills |

| Stein et al., 2018 | King County, WA, U.S. | Evaluate an intervention that teaches hospitalized patients at a safety net hospital how to access and use their EHR online portal | RCT of in-person patient portal education during admission involving registration, login, navigating website, and reviewing discharge summary | Education/training was effective at increasing portal use |

| Fields et al., 2020 | San Francisco, CA, U.S. | To assess barriers and facilitators to technology training implementation | Pilot involving community-based organization to evaluate the impact of technology training on older adults’ loneliness, social support, and technology use in real-world settings. | Embedding training within existing community-based programs holds promise as a potentially sustainable mechanism to provide digital training to isolated older adults. |

| National Health Services, Widening Digital Participation, 2017 | England, U.K. | 3-year program provided seed funding to (a) establish 20+ projects focused on specific patient populations in each community; (b) create portal to promote digital skills (Learn My Way) and use of digital tools to promote health (Staying Healthy); (c) support “pre-digital” skills | Help those without digital skills to access health information and support online. The program aimed to put the individual in charge of their health, with a long-term aim to also relieve pressure on frontline health services. | Projects reached 285,000+ people and specifically 53,000+ improved their digital literacy 83% that used the digital skills portal reported more confident about using online tools to manage their health; 33% who completed training reported fewer primary care visits Governments can support widescale dissemination and innovation through establishing standard curriculum and collaborating with community-based organizations to reduce overall costs |

| 3. Example digital health studies leveraging community/social relationships to support use | ||||

| Nguyen et al., 2021 | Community-based organizations, San Francisco, CA, U.S. | Development of a digital health search/referral platform to connect community members with resources in their neighborhoods | Qualitative study focused on user needs and requirements for a digital health platform | Community organizations essential for tangible resource connections as well as overall social support and trust Digital platforms must enhance existing human knowledge of community assets/needs |

| Heisler et al., 2019 | Urban VA clinic, Detroit, MI, U.S. | Peer coaching intervention for diabetes management, with vs without digital tool | RCT with glycemic control as primary outcome measure Assessments at baseline, 6 months, 12 months |

Peer coaching critical for improving outcomes, including detailed documentation of coaching implementation Digitally-enabled coaching may need longer-term use in future studies |

| Roddy et al., 2022 | Urban academic medical center and community clinics, Nashville, TN, U.S. | Text messaging intervention to support diabetes management, with specific sub-intervention that engaged family/adult supporters | Secondary analysis of RCT, with glycemic control as the primary outcome measure | Family/adult support mediated the improvements in diabetes control post-intervention Future studies needed to tease apart these influences |

| Holt et al., 2018 | African American churches in Metro DC area, U.S. | Evaluate and compare web-based vs. in-person peer coaching for preventive health behaviors | RCT evaluating cancer-related knowledge and screening behaviors between groups | No significant differences in cancer knowledge or screening rates at 24 months by group Web-based coaching as effective as in-person, but process measures by arm not reported |

| Handley et al., 2021 | Safety-net settings, San Francisco Bay area | Examine fidelity and acceptability of coaching intervention by language of participants (English vs Spanish speakers) | Secondary analysis of RCT data to determine how in-person and digital support might have varied by participant demographics | High overall engagement and acceptability of coaching in the study, with no differences in modality by participant language. Critical to have clear analytic plan to examine implementation outcomes based on modality of coaching (digital vs. in-person) and key participant demographics |

| 4. Example studies focusing on systems-level implementation of digital interventions or programs, specifically within safety net settings | ||||

| Watkinson et al., 2021 | U.K., England | Measure system-level acceptance of Health Information Exchange (HIE) and understand barriers/facilitators to adoption | Mixed-methods study to examine differences in acceptance between user groups and care settings | Social care users had lower acceptance and adoption. They also lacked resources to properly use HIE system |

| Peynetti Velázquez et al., 2020 | Boston, MA, U.S. safety net system | Rapid implementation of telepsychiatry to meet care needs for diverse patient population | Implementation study outlining change management processes used to implement services | Multiple departments engaged to create patient-focused implementation Core domains focused on during the intervention included people, process, technology, monitoring, environment, and equity |

| California Healthcare Foundation innovation fund, 2011 | California, U.S. | Philanthropic investment program to specifically fund private sector digital health companies with potential to improve care quality for Medicaid patients | By 2021, the fund’s portfolio served over 5M Medi-Cal enrollees at over 250 hospitals & 100 clinics in California. Portfolio companies experienced an average 115% annual growth the market opportunity in California | Vital and feasible to use capital investment for supporting private companies working in the Medicaid market |

| Barnett et al., 2017 | Los Angeles safety-net hospital | Decrease wait time to see a specialist | Examine growth, usage, and outcomes of eConsult system implementation | Rapid growth in eConsult use. Decreased wait times to see a specialist Health systems and plans partnered to solve a high-priority problem, achieving implementation prior to more well-resourced settings |

| Aulakh and Maguire, 2021 | Safety-net systems nationwide | Provide guidance for safety-net leaders and providers to improve digital healthcare services via innovation approaches | Collaboratives and peer learning for innovation is successful strategy for innovation in safety net settings | Shared learning models across sites and settings (healthcare, community-based organizations) can increase impact Phased implementation and support (technical assistance, training, networking) are critical |

| Lyles et al., 2014 | Safety-net systems in California | Qualitative study of safety net leaders, focusing on drivers of innovation implementation | Examples of successful innovations alongside unique contexts for implementation | Safety net leaders emphasize their approaches to centering equity and addressing highest priority topics, rather than supporting too many programs/pilots |

| 5. Example studies of programs that addressed structural barriers to digital health interventions, such as broadband access or devices | ||||

| Gujral et al., 2022 | Rural U.S. | Assess association between increased distribution of tablets during COVID-19 pandemic and mental health service use and related outcomes | Retrospective cohort study Loaned iPads to rural U.S. Veterans from March 2020-April 2021. Compared outcomes 10 months before tablet receipt and 10 months after tablets to controls |

Increased mental health care use, reduced suicidal behavior and ED visits For rural veterans already engaged in mental health care, tablets can help increase access to mental health services |

|

Zulman et al., 2019

Jacobs et al., 2019 Slightam et al., 2020 |

U.S., nationwide in the VA | Evaluate implementation of tablet distribution to high-need veterans with health care access barriers | Retrospective cohort study 2016 VA pilot distributed video-enabled tablets with 4G wireless or Wi-Fi to veterans with access barriers. Evaluated outcomes of tablet adoption and reach, and barriers and facilitators of tablet use for telehealth. |

Zulman et al, 2019: 80% of patients who received tablets used them; those who were older and who had fewer chronic conditions were less likely to use. Facility-level barriers to implementing tablet program included staffing shortages and lack of staff training Slightam et al, 2020: lack of digital skills and poor Internet connection associated with lower preference for video visits Jacobs et al, 2019: time and money savings for those who live far away from VA, have travel barriers, do not have mental health diagnosis |

| Whealin et al., 2017 | Rural areas of the Pacific Islands | Evaluate veterans’ perceptions of home therapy for PTSD through video-enabled tablets | VA pilot of tablets and secure WiFi for home treatment of PTSD Pre- and post- engagement questionnaire |

Feasible to use tablets to deliver treatment to rural veterans of racial/ethnic minority ancestry; Some patients still had privacy and connectivity concerns |

| Davis et al., 2016 | U.S. | Understand technical needs to support veterans after distribution of tablets for telemental health services | Assess workload and productivity of Peer Technical Consultant (PTC) in providing technical support to veterans Survey veterans and providers during and after telemental health program treatment about role of PTC |

For veterans with diverse digital literacy skills and mental health care needs, robust technical support is needed for successful use of devices and telehealth technologies. PTC should be a full-time contract-employee to increase availability of technical support |

| Schueller et al., 2019 | Homeless shelter network located in Chicago, IL, U.S. | Evaluate feasibility and acceptability of remotely delivered mental health intervention with brief emotional support and coping skills among young adults experiencing homelessness | Single-arm feasibility pilot trial, pre-post intervention evaluation Participants received mobile phone, service/ data plan, 1 month of coaching Assess session and program completion, and acceptability based on satisfaction ratings |

High rates of program completion and satisfaction among participants Little change on pre-post measures of depression, PTSD, emotion regulation Feasible and acceptable to provide technology-based mental health services to young adults experiencing homelessness |

| Kazevman et al., 2021 | Ontario, Canada | Improve access to primary care, adherence to public health directives and adherence to self-isolation guidelines during COVID-19 pandemic | Provide free donated and prepaid cell phones to patients without a listed phone number who presented for care at emergency department during COVID-19 pandemic Protocol paper for pilot mixed-methods study, no data reported |

Examination of program on health outcomes underway Approach attempts to improve patient access to health care, information, and social services |

| Moczygemba et al., 2021 | Austin, TX, U.S. | Assess the accuracy, acceptability, and outcomes of a GPS-mHealth intervention to alert community health paramedics when people experiencing homelessness were in emergency department or hospital | Pre-post design with assessments at baseline, 1 month, 2 months, 3 months, and 4 months post-enrollment | Limited accuracy for ED/hospital alerts Decrease in depression symptoms, improved medication adherence Cell phone provision can help individuals with complex medical needs and experiencing homelessness improve medication adherence and maintain contact with social support networks |

| LAUNCH program (FCC-NCI), 2020 | Appalachia (Rural U.S.) | Better understand landscape of connected cancer care management in rural America | Framework and proposed program to improve telehealth-enabled cancer care for rural America | Need for community-based participatory approach for human-centered design of digital cancer care |

1. Interventions/Programs that employ digital health co-design to advance equity in usability, uptake, and/or effectiveness of digital health platforms

Digital health interventions need to be designed with the communities they hope to help and to meet real needs. Content experts have important knowledge (such as clinical or technical expertise), but users are experts in their own lives and how to integrate digital tools with their ongoing needs and preferences. Co-design methods jointly conceptualize and develop digital products driven by the expertise of end users as well as those involved in their care such as family members and healthcare staff.(72) Co-design and user centered design have parallels with community-based participatory research and other community-engaged methods that have been implemented more broadly.(13)

There are multiple examples from the published literature that outline co-design work focused on marginalized and excluded communities (Table, part 1). For example, one study partnered with community members to design a smartphone app to collect user experience related to walking and the built environment, with an explicit goal of feeding these data back to decision makers about possible community improvements.(15) Other examples of co-design include studies outlining the longitudinal and iterative process of assessing feedback from users about both the content and early prototypes/features of digital health platforms, including the mix of traditional and design methods with an explicit focus on cultural relevance in all phases of work.(44) Despite the imperative for participatory co-design in digital health, there are challenges to effectively engaging in the work. It requires strong community partnerships that take time to develop. It is also important to address cultural mismatches between developers and community organizations/users in the way each addresses problems.(98)

These studies also present clear recommendations for the field. For example, studies often need to engage in over a year of formative design and development to achieve relevant tools when working with people with limited health and digital literacy.(7) In addition, co-design approaches must evolve in ways that match the experiences of underserved and marginalized populations. Methods that require abstraction and verbal communication (often linked to formal educational exposure) may not be relevant for all populations or studies.(38). For example, “card sorting” is a common task to help users rank intervention content and methods based on preference; however, users with limited health literacy, English proficiency, and digital literacy sometimes have difficulty with the method.(70)

2. Interventions that provide individual-level digital literacy support or training as a core program component

Another type of intervention with success in addressing digital health equity involves explicitly focusing on digital literacy skills through training or support programs. Many of the studies in this section (Table, part 2) focused on training programs have been small and delivered to a specific patient population (e.g., older adults or inpatients within a hospital setting).

Despite the limited number of these studies, the example studies highlight a few key points. First, both healthcare organizations and community-based organizations can conduct trainings successfully. However, trainings conducted by community-based organizations tend to focus more broadly on digital health skills,(33, 41, 91) whereas healthcare systems (and most interventional research studies) have focused primarily on increasing skills to access specific digital health tools (such as a patient portal or mobile health application).(59, 90)

There is also variation in the modalities in how training is delivered, including web-based videos or more intense in-person 1-on-1 or small group training.(103) Studies have found all of these modalities to be somewhat successful at increasing confidence and digital literacy for at least some of the participants; however, many studies have suggested that there is at least a plurality of individuals that need more intensive hands-on support to increase their digital literacy to a level where they can access digital tools.

Among studies focused specifically on health platforms, digital literacy efforts have focused primarily on use of patient portals, mobile health applications, or searching for online information.(51, 59, 90, 103) Very few studies have evaluated the impact of training on improving health outcomes or on long-term impacts of training, though some have shown some improvement in self-reported health behaviors (e.g., looking for information; using digital tools to engage with clinical team).

3. Digital programs that leverage community/social relationships to support use

Because of the important role of social connections within communities on the awareness, use, and ultimate effectiveness of digital health programs, there is also a growing body of work that implement and evaluate a digital health intervention within social contexts.(85) In many cases, these studies document processes and measure outcomes at an individual patient or community member level, as well as processes and outcomes that are specific to the caregiver or environment/setting in which the digital program or intervention was conducted. This work is critical to advancing our understanding of how we will blend digital and human support in public health and healthcare digitally-enabled programs into the future.

Part 3 of the Table documents studies from a range of community- or caregiver/provider-supported digital health platforms. Overall, these studies demonstrate the wide range of research on this topic: from understanding community-based organization assets related to chronic disease management prior to developing a digital health resource platform,(69) utilizing digital platforms to support peer coaching in clinical and community settings(39) (42); designing parallel text messaging programs to support both patients as well as caregivers/loved ones(76); and explicitly evaluating the implementation of digital and in-person support within an intervention.(37) All of the studies demonstrate – using either quantitative or qualitative results – that digital programs can be better tailored and/or easily delivered by leveraging implementation assistance from important social and interpersonal relationships.

However, the studies are less clear with regard to generalizability of this work, given that there is wide variation in what type of social relationship was engaged (e.g., family vs. peer coach vs. community organization) and the specific approach to implementation (e.g., starting with in-person support and then adding human follow-up or vice versa, what pieces of the intervention required in-person support). Additional attention will be needed to tease apart the influence of the in-person/human support from digital support, given that we know how effective in-person support can be on health outcomes and are often striving to reduce the intensity of in-person support within digital programs.

4. Systems-level implementation of digital interventions or programs, specifically within safety net settings

Safety-net health systems and public health settings are essential when implementing digital platforms to advance health equity. In part 4 of the Table, we enumerate some example health system innovations that shed light on digital health equity. First, there are several examples of successful implementation of programs such as telepsychiatry/telemedicine(101) and eConsults(10) that demonstrate how aligned incentives and a focus on team-based workflows are essential. In addition, there is an example(18) that demonstrates the importance of focusing on system-level investment (e.g., private investment into digital health companies working on products for the Medicaid market) to bridge the equity gaps in available products and tools. Finally, there is evidence from studies or collaboratives across multiple safety net settings that demonstrate differences in local priorities and the need to engage frontline staff and adapt implementation as relevant.(6, 56, 104)

Overall, these studies demonstrate that stakeholder engagement (such as through collaboratives, with mix of frontline staff plus leadership) is a core element of bringing a digital health tool into wider use at the system-level, and not a process that is done once or at the end of rolling out a new platform or solution. These examples also provide evidence that safety net and public settings face unique barriers to consider during implementation, such as the need for support/technical assistance to stand up digitally enabled services that work within their existing staffing and digital infrastructures. And finally, we must leverage the vast expertise within safety net settings, given that they have longstanding relationships in many marginalized communities and have centered equity within their health programs for many years.(57)

5. Policies/programs that addressed structural barriers to digital health interventions, such as broadband access or devices

There is a growing amount of literature documenting the provision of broadband and Internet-enabled devices within health or healthcare programs, with key studies summarized in part 5 of the Table. The most robust studies in this space are from the Veterans’ Administration (VA), which delivers health care to 9 million veterans in the U.S., with a third living in rural areas with limited access to in-person care. Throughout various waves of a nationwide VA connected care program, provision of video-enabled tablets increased access to both medical and mental health care,(36) but barriers persisted, such as lack of digital skills, a need for technical support, and a need for improved Internet connectivity.(24, 45, 88, 105, 110)

Providing smartphones with data plans is another strategy to help improve access to care. One pilot demonstrated modest success with this strategy to facilitate use of a mental health app-based intervention among youth, though data caps were a key obstacle for participants.(83) Among adult populations, one recent study described prescription of smartphones in the emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic with no health outcomes reported;(47) another pilot distributing smartphones to adults experiencing homelessness found limited impact of smartphones on care coordination, but increased empowerment for self-management activities in this population.(66, 96)

Finally, there are no studies to date assessing the direct impact of broadband or other Internet service provision on health outcomes. In 2017, the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) convened a public-private partnership with the National Cancer Institute to bridge the broadband health connectivity gap in Appalachia through the LAUNCH initiative (Linking and Amplifying User-Centered Networks through Connected Health) in order to improve cancer-related health care and symptom management, though no health or outcomes data are available yet.(19, 30, 84)

Recommendations for the field

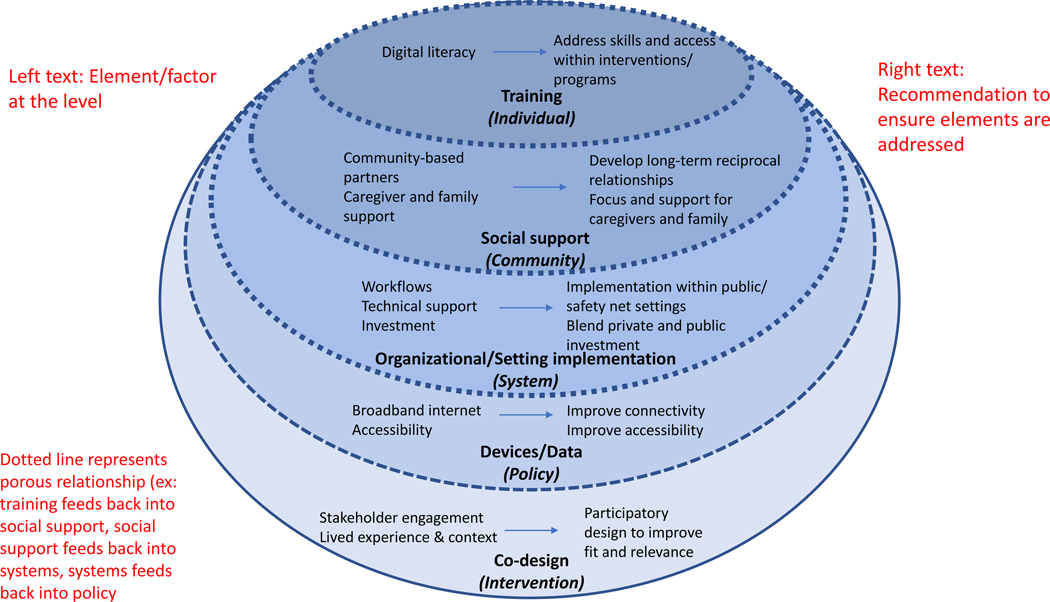

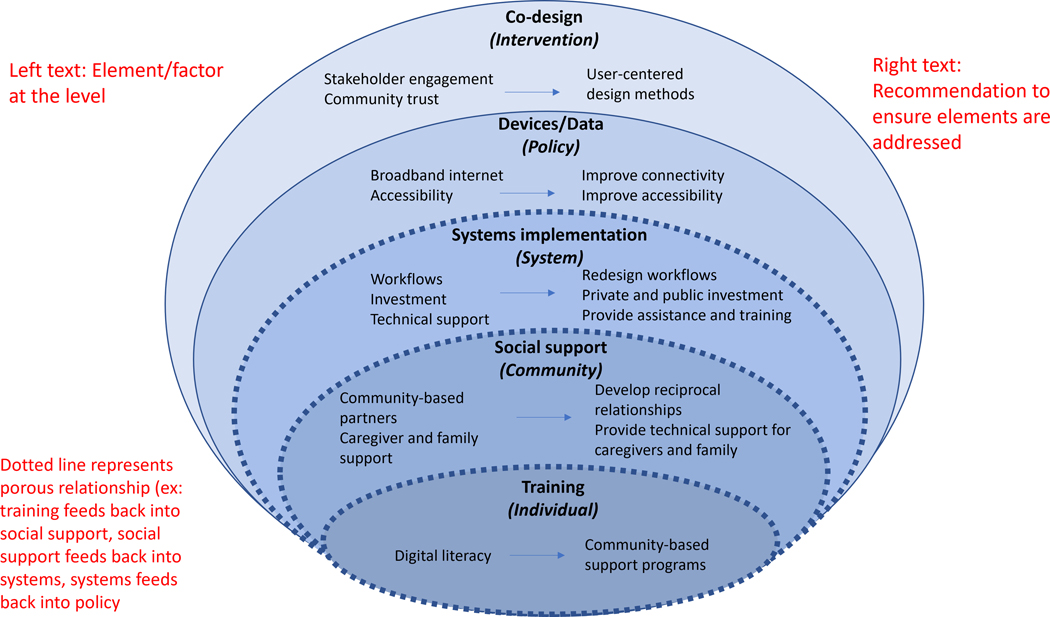

In summary, digital health equity necessitates a multi-level understanding of how policy, systems, community, individual, and intervention factors interact. A summary of the multi-level determinants of digital health and associated interventions to reduce inequities is shown in the Figure. While there are many barriers that impede the ability for all individuals to take up and effectively use digital health tools and services, there are also known strategies for advancing and centering equity that can be replicated and spread. It is critical for practitioners and researchers to move beyond a single level of influence and implement programs and interventions that target foundational aspects of digital health equity, such as: community co-design utilizing inclusive principles; digital skills/literacy training and interpersonal support; and implementation approaches that both reflect real-world practice within safety net and public settings and ensure universal access to devices and data/Internet.

Figure 1.

(Left, white boxes) Element/factor at the level. (Right, pink boxes) Recommendation to ensure elements are addressed. Dotted lines represent porous relationship (e.g., training feeds back into social support, social support feeds back into systems, systems feeds back into policy).

Moving forward, the work to date also indicates recommendations for advancing the field of digital health equity. First, much of the work presented here was often completed within a specific discipline, such as clinical research or public health practice. Future work must break down silos between fields, as well as ensure a broader definition or focus on overall health, not specific to a single disease or health behavior. Designing or implementing equitable digital health programs also requires both broad and deep stakeholder engagement. For example, stakeholders must be identified in healthcare, community, public/social service, and other sectors to generate better synergy in our work. In addition, the deep community-based partnerships and input from community members must be invested and supported in the long term, not on a project-by-project or transactional basis.

Second, to generate true impact, we must also utilize implementation approaches and generation of real-world evidence from the outset. Because we know that digital health often involves new ways to deliver existing health education or support/services and evolves very quickly as technology changes, we cannot rely on traditional program evaluation or research approaches alone. Instead, we must consider both the process of implementing digital health (particularly in public and safety net settings) alongside the effectiveness of digital health services and programs. This implementation focus will better allow us to understand key steps such as: 1) who is taking up the digital program as it is rolled out?, 2) how are care providers, coaches, or others involved in the program, and what are their roles in promoting or using the technology?, 3) what are the barriers to adoption and spread across the entire implementation process?

Finally, centering equity in digital health will require new measurement approaches and standards. We will not succeed in understanding and addressing digital health gaps unless we collectively measure and report on key equity domains. This will involve research studies and programs defining and reporting on such as: 1) digital access (such as devices and Internet at home), 2) skills and interest, such as comfort in using digital platforms without assistance and trust in digital services/tools, 3) and participant demographics, such as language or race/ethnicity, to monitor specific subpopulations that have been historically and presently excluded from many digital health programs to date.

All of us will use digitally enabled health and healthcare programs in the future, and this work can advance equity if we explicitly focus on the multi-factorial drivers of digital health use and then spread strategies that will better engage individuals, communities, and systems.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Marika Dy for her support with project management, data collection, and presentation of results.

Funding:

Courtney Lyles is funded by a UCSF/Genentech career development award. Elaine Khoong is supported by a career development award from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (K23HL157750). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References:

- 1.Adepoju OE, Chae M, Ojinnaka CO, Shetty S, Angelocci T. 2022. Utilization Gaps During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Telemedicine Uptake in Federally Qualified Health Center Clinics. J Gen Intern Med. 37(5):1191–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler-Milstein J.2021. From Digitization to Digital Transformation: Policy Priorities for Closing the Gap. JAMA. 325(8):717–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anthony C.2021. Black tech founders want to change the culture of healthcare, one click at a time. Fierce Healthcare. www.fiercehealthcare.com [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antoninis M, Montoya S. 2018. A Global Framework to Measure Digital Literacy. UNESCO. http://uis.unesco.org [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assessment of Health IT and Data Exchange in Safety Net Providers. 2010. National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago, Bethesda, MD [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aulakh V, Maguire L. 2021. Investing In Teaching Safety-Net Providers To Innovate Can Address Health Inequities. Health Aff [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avila-Garcia P, Hernandez-Ramos R, Nouri SS, Cemballi A, Sarkar U, et al. 2019. Engaging users in the design of an mHealth, text message-based intervention to increase physical activity at a safety-net health care system. JAMIA Open. 2(4):489–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azzopardi-Muscat N, Sørensen K. 2019. Towards an equitable digital public health era: promoting equity through a health literacy perspective. Eur J Public Health. 29(Suppl 3):13–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bandura A.2004. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 31(2):143–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnett ML, Yee HF, Mehrotra A, Giboney P. 2017. Los Angeles Safety-Net Program eConsult System Was Rapidly Adopted And Decreased Wait Times To See Specialists. Health Aff (Millwood). 36(3):492–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beaunoyer E, Dupéré S, Guitton MJ. 2020. COVID-19 and digital inequalities: Reciprocal impacts and mitigation strategies. Comput Human Behav. 111:106424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bobian M, Kandinov A, El-Kashlan N, Svider PF, Folbe AJ, et al. 2017. Mobile applications and patient education: Are currently available GERD mobile apps sufficient? Laryngoscope. 127(8):1775–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brewer LC, Fortuna KL, Jones C, Walker R, Hayes SN, et al. 2020. Back to the Future: Achieving Health Equity Through Health Informatics and Digital Health. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 8(1):e14512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Budd J, Miller BS, Manning EM, Lampos V, Zhuang M, et al. 2020. Digital technologies in the public-health response to COVID-19. Nat Med. 26(8):1183–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buman MP, Winter SJ, Sheats JL, Hekler EB, Otten JJ, et al. 2013. The Stanford Healthy Neighborhood Discovery Tool. Am J Prev Med. 44(4):e41–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carey TS, Bekemeier B, Campos-Outcalt D, Koch-Weser S, Millon-Underwood S, Teutsch S. 2020. National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop: Achieving Health Equity in Preventive Services. Ann Intern Med. 172(4):272–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerise FP, Moran B, Huang PP, Bhavan KP. The Imperative for Integrating Public Health and Health Care Delivery Systems. NEJM Catalyst. 2(4): [Google Scholar]

- 18.CHCF Innovation Fund.

- 19.Chih M-Y, McCowan A, Whittaker S, Krakow M, Ahern D, et al. 2020. The Landscape of Connected Cancer Symptom Management in Rural America: A Narrative Review of Opportunities for Launching Connected Health Interventions. Journal of Appalachian Health. 2(4):66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark D, Roberson B, Ramiah K. 2021. Essential Data: Results of America’s Essential Hospitals 2019 Annual Member Characteristics Survey. America’s Essential Hospitals, Washington DC [Google Scholar]

- 21.Community-Based Organizations Are Important Partners for Health Care Systems. 2020. The National Academies of Sciences, Medicine, an Engineering [Google Scholar]

- 22.Courtois C, Verdegem P. 2016. With a little help from my friends: An analysis of the role of social support in digital inequalities. New Media & Society. 18(8):1508–27 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis FD. 1985. A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems : theory and results. Thesis thesis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis T, Shore P, Lu M. 2016. Peer Technical Consultant: Veteran-Centric Technical Support Model for VA Home-Based Telehealth Programs. Fed Pract. 33(3):31–36 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Definitions. National Digital Inclusion Alliance. www.digitalinclusion.org [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desveaux L, Soobiah C, Bhatia RS, Shaw J. 2019. Identifying and Overcoming Policy-Level Barriers to the Implementation of Digital Health Innovation: Qualitative Study. J Med Internet Res. 21(12):e14994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diviani N, van den Putte B, Giani S, van Weert JC. 2015. Low health literacy and evaluation of online health information: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res. 17(5):e112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duncan MJ, Kolt GS. 2019. Learning from community-led and co-designed m-health interventions. The Lancet Digital Health. 1(6):e248–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El Benny M, Kabakian-Khasholian T, El-Jardali F, Bardus M. 2021. Application of the eHealth Literacy Model in Digital Health Interventions: Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res. 23(6):e23473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellison M, Vanderpool R. 2020. Preface: Experiencing Cancer in Appalachian Kentucky. Journal of Appalachian Health. 2(3):71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emani S, Yamin CK, Peters E, Karson AS, Lipsitz SR, et al. 2012. Patient Perceptions of a Personal Health Record: A Test of the Diffusion of Innovation Model. J Med Internet Res. 14(6):e150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farberman RK, McKillop M, Lieberman DA, Delgado D, Thomas C, et al. 2020. The Impact of Chronic Underfunding on America’s Public Health System: Trends, Risks, and Recommendations, 2020. Trust for America’s Health. www.tfah.org [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fields J, Cemballi AG, Michalec C, Uchida D, Griffiths K, et al. 2021. In-Home Technology Training Among Socially Isolated Older Adults: Findings From the Tech Allies Program. J Appl Gerontol. 40(5):489–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher EB, Ayala GX, Ibarra L, Cherrington AL, Elder JP, et al. 2015. Contributions of Peer Support to Health, Health Care, and Prevention: Papers from Peers for Progress. Ann Fam Med. 13(Suppl 1):S2–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friis-Healy EA, Nagy GA, Kollins SH. 2021. It Is Time to REACT: Opportunities for Digital Mental Health Apps to Reduce Mental Health Disparities in Racially and Ethnically Minoritized Groups. JMIR Ment Health. 8(1):e25456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gujral K, Van Campen J, Jacobs J, Kimerling R, Blonigen D, Zulman DM. 2022. Mental Health Service Use, Suicide Behavior, and Emergency Department Visits Among Rural US Veterans Who Received Video-Enabled Tablets During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 5(4):e226250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Handley MA, Landeros J, Wu C, Najmabadi A, Vargas D, Athavale P. 2021. What matters when exploring fidelity when using health IT to reduce disparities? BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 21(1):119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harrington C, Erete S, Piper AM. 2019. Deconstructing Community-Based Collaborative Design: Towards More Equitable Participatory Design Engagements. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 3(CSCW):216:1–216:25 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heisler M, Choi H, Mase R, Long JA, Reeves PJ. 2019. Effectiveness of Technologically Enhanced Peer Support in Improving Glycemic Management Among Predominantly African American, Low-Income Adults With Diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 45(3):260–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Helsper EJ, van Deursen AJAM. 2017. Do the rich get digitally richer? Quantity and quality of support for digital engagement. Information, Communication & Society. 20(5):700–714 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoffman L, Wisniewski H, Hays R, Henson P, Vaidyam A, et al. 2020. Digital Opportunities for Outcomes in Recovery Services (DOORS): A Pragmatic Hands-On Group Approach Toward Increasing Digital Health and Smartphone Competencies, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Alliance for Those With Serious Mental Illness. J Psychiatr Pract. 26(2):80–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holt CL, Tagai EK, Santos SLZ, Scheirer MA, Bowie J, et al. 2019. Web-based versus in-person methods for training lay community health advisors to implement health promotion workshops: participant outcomes from a cluster-randomized trial. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 9(4):573–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Institute of Medicine. 2000. America’s Health Care Safety Net: Intact but Endangered. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jackson DN, Sehgal N, Baur C. 2022. Benefits of mHealth Co-design for African American and Hispanic Adults: Multi-Method Participatory Research for a Health Information App. JMIR Formative Research. 6(3):e26764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jacobs JC, Blonigen DM, Kimerling R, Slightam C, Gregory AJ, et al. 2019. Increasing Mental Health Care Access, Continuity, and Efficiency for Veterans Through Telehealth With Video Tablets. Psychiatr Serv. 70(11):976–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.James CV, Lyons B, Saynisch PA, Scholle SH. 2021. Modernizing Race and Ethnicity Data in Our Federal Health Programs. The Commonwealth Fund. www.commonwealthfund.org [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kazevman G, Mercado M, Hulme J, Somers A. 2021. Prescribing Phones to Address Health Equity Needs in the COVID-19 Era: The PHONE-CONNECT Program. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 23(4):e23914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kolovson S, Pratap A, Duffy J, Allred R, Munson SA, Areán PA. 2020. Understanding Participant Needs for Engagement and Attitudes towards Passive Sensing in Remote Digital Health Studies. Int Conf Pervasive Comput Technol Healthc. 2020:347–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Korin MR, Araya F, Idris MY, Brown H, Claudio L. 2022. Community-Based Organizations as Effective Partners in the Battle Against Misinformation. Frontiers in Public Health. 10: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krist AH, Phillips R, Leykum L, Olmedo B. 2021. Digital health needs for implementing high-quality primary care: recommendations from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 28(12):2738–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee K, Hoti K, Hughes JD, Emmerton LM. 2014. Interventions to assist health consumers to find reliable online health information: a comprehensive review. PLoS One. 9(4):e94186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levy J, Álvarez D, Rosenberg AA, Alexandrovich A, del Campo F, Behar JA. 2021. Digital oximetry biomarkers for assessing respiratory function: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. NPJ Digit Med. 4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin Q, Paykin S, Halpern D, Martinez-Cardoso A, Kolak M. 2022. Assessment of Structural Barriers and Racial Group Disparities of COVID-19 Mortality With Spatial Analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 5(3):e220984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lopez KD, Chae S, Michele G, Fraczkowski D, Habibi P, et al. 2021. Improved readability and functions needed for mHealth apps targeting patients with heart failure: An app store review. Res Nurs Health. 44(1):71–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lyles CR, Aguilera A, Nguyen O, Sarkar U. 2022. Bridging the Digital Health Divide: How Designers Can Create More Inclusive Digital Health Tools. California Health Care Foundation [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lyles CR, Aulakh V, Jameson W, Schillinger D, Yee H, Sarkar U. 2014. Innovation and Transformation in California’s Safety-net Healthcare Settings: An Inside Perspective. Am J Med Qual. 29(6):538–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lyles CR, Handley MA, Ackerman SL, Schillinger D, Williams P, et al. 2019. Innovative Implementation Studies Conducted in US Safety Net Health Care Settings: A Systematic Review. Am J Med Qual. 34(3):293–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lyles CR, Sarkar U, Ralston JD, Adler N, Schillinger D, et al. 2013. Patient-provider communication and trust in relation to use of an online patient portal among diabetes patients: The Diabetes and Aging Study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 20(6):1128–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lyles CR, Tieu L, Sarkar U, Kiyoi S, Sadasivaiah S, et al. 2019. A Randomized Trial to Train Vulnerable Primary Care Patients to Use a Patient Portal. J Am Board Fam Med. 32(2):248–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lyles CR, Wachter RM, Sarkar U. 2021. Focusing on Digital Health Equity. JAMA. 326(18):1795–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Manganello J, Gerstner G, Pergolino K, Graham Y, Falisi A, Strogatz D. 2017. The Relationship of Health Literacy With Use of Digital Technology for Health Information: Implications for Public Health Practice. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 23(4):380–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marlize van Romburgh, Gene Teare. 2021. Funding To Black Startup Founders Quadrupled In Past Year, But Remains Elusive. Crunchbase News. https://news.crunchbase.com [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mcclain C, Vogels E a, Perrin A, Sechopoulos S, Rainie L. 2021. The Internet and the Pandemic [Google Scholar]

- 64.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. 1988. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 15(4):351–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meyerhoff J, Haldar S, Mohr DC. 2021. The Supportive Accountability Inventory: Psychometric properties of a measure of supportive accountability in coached digital interventions. Internet Interv. 25:100399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moczygemba LR, Thurman W, Tormey K, Hudzik A, Welton-Arndt L, Kim E. 2021. GPS Mobile Health Intervention Among People Experiencing Homelessness: Pre-Post Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 9(11):e25553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Muñoz AO, Camacho E, Torous J. 2021. Marketplace and Literature Review of Spanish Language Mental Health Apps. Front Digit Health. 3:615366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Muñoz RF, Chavira DA, Himle JA, Koerner K, Muroff J, et al. 2018. Digital apothecaries: a vision for making health care interventions accessible worldwide. Mhealth. 4:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nguyen KH, Fields JD, Cemballi AG, Desai R, Gopalan A, et al. 2021. The Role of Community-Based Organizations in Improving Chronic Care for Safety-Net Populations. J Am Board Fam Med. 34(4):698–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nouri S, Khoong EC, Lyles CR, Karliner L. 2020. Addressing Equity in Telemedicine for Chronic Disease Management During the Covid-19 Pandemic. NEJM Catalyst [Google Scholar]

- 71.O’Connor S, Hanlon P, O’Donnell CA, Garcia S, Glanville J, Mair FS. 2016. Understanding factors affecting patient and public engagement and recruitment to digital health interventions: a systematic review of qualitative studies. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 16:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Papoutsi C, Wherton J, Shaw S, Morrison C, Greenhalgh T. 2021. Putting the social back into sociotechnical: Case studies of co-design in digital health. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 28(2):284–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Peretz PJ, Islam N, Matiz LA. 2020. Community Health Workers and Covid-19 — Addressing Social Determinants of Health in Times of Crisis and Beyond. New England Journal of Medicine. 383(19):e108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Perrin A.2021. Mobile Technology and Home Broadband 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pratap A, Neto EC, Snyder P, Stepnowsky C, Elhadad N, et al. 2020. Indicators of retention in remote digital health studies: a cross-study evaluation of 100,000 participants. npj Digit. Med. 3(1):1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Roddy MK, Nelson LA, Greevy RA, Mayberry LS. 2022. Changes in family involvement occasioned by FAMS mobile health intervention mediate changes in glycemic control over 12 months. J Behav Med. 45(1):28–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rodriguez JA, Clark CR, Bates DW. 2020. Digital Health Equity as a Necessity in the 21st Century Cures Act Era. JAMA. 323(23):2381–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rodriguez JA, Singh K. 2018. The Spanish Availability and Readability of Diabetes Apps. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 12(3):719–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Romm T.2021. Lacking a Lifeline: How a federal effort to help low-income Americans pay their phone bills failed amid the pandemic. Washington Post, Feb. 9 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rudolph L, Caplan J, Ben-Moshe K, Dillon L. 2013. Health in All Policies: A Guide for State and Local Governments. American Public Health Association and Public Health Institute, Washington, D.C. and Oakland, CA [Google Scholar]

- 81.Safavi K, Mathews SC, Bates DW, Dorsey ER, Cohen AB. 2019. Top-Funded Digital Health Companies And Their Impact On High-Burden, High-Cost Conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 38(1):115–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sarkar U, Gourley GI, Lyles CR, Tieu L, Clarity C, et al. 2016. Usability of Commercially Available Mobile Applications for Diverse Patients. J Gen Intern Med. 31(12):1417–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schueller SM, Glover AC, Rufa AK, Dowdle CL, Gross GD, et al. 2019. A Mobile Phone-Based Intervention to Improve Mental Health Among Homeless Young Adults: Pilot Feasibility Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 7(7):e12347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Scutchfield F, Patrick K. 2020. Introducing the L.A.U.N.C.H. Collaborative. Journal of Appalachian Health. 2(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shaffer KM, Tigershtrom A, Badr H, Benvengo S, Hernandez M, Ritterband LM. 2020. Dyadic Psychosocial eHealth Interventions: Systematic Scoping Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 22(3):e15509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shaw J, Agarwal P, Desveaux L, Palma DC, Stamenova V, et al. 2018. Beyond “implementation”: digital health innovation and service design. npj Digital Med. 1(1):1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sieck CJ, Sheon A, Ancker JS, Castek J, Callahan B, Siefer A. 2021. Digital inclusion as a social determinant of health. NPJ Digit Med. 4:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Slightam C, Gregory AJ, Hu J, Jacobs J, Gurmessa T, et al. 2020. Patient Perceptions of Video Visits Using Veterans Affairs Telehealth Tablets: Survey Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 22(4):e15682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Snowdon A.2020. HIMSS Defines Digital Health for the Global Healthcare Industry. HIMSS. www.himss.org [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stein JN, Klein JW, Payne TH, Jackson SL, Peacock S, et al. 2018. Communicating with Vulnerable Patient Populations: A Randomized Intervention to Teach Inpatients to Use the Electronic Patient Portal. Appl Clin Inform. 9(4):875–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stone E, Nuckley P, Shapiro R. 2020. Digital Inclusion in Health and Care: Lessons learned from the NHS Widening Digital Participation Programme. Good Things Foundation, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 92.Svendsen MJ, Wood KW, Kyle J, Cooper K, Rasmussen CDN, et al. 2020. Barriers and facilitators to patient uptake and utilisation of digital interventions for the self-management of low back pain: a systematic review of qualitative studies. BMJ Open. 10(12):e038800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tao D, Shao F, Wang H, Yan M, Qu X. 2020. Integrating usability and social cognitive theories with the technology acceptance model to understand young users’ acceptance of a health information portal. Health Informatics J. 26(2):1347–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.The Lancet null. 2021. 50 years of the inverse care law. Lancet. 397(10276):767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Thielke A, King V. 2020. Electronic Consultations (eConsults): Promising Evidence and Policy Considerations for Implementation. Milbank Memorial Fund, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 96.Thurman W, Semwal M, Moczygemba LR, Hilbelink M. 2021. Smartphone Technology to Empower People Experiencing Homelessness: Secondary Analysis. J Med Internet Res. 23(9):e27787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Turi JB. 2022. VC Funding To Early-Stage Latinx-Founded Startups In The US Has Stalled. Here’s Why That Matters. Crunchbase News. https://news.crunchbase.com [Google Scholar]

- 98.Unertl KM, Schaefbauer CL, Campbell TR, Senteio C, Siek KA, et al. 2016. Integrating community-based participatory research and informatics approaches to improve the engagement and health of underserved populations. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 23(1):60–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Uscher-Pines L, Sousa J, Jones M, Whaley C, Perrone C, et al. 2021. Telehealth use among safety-net organizations in California during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 325(11):1106–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.VC Funding Diversity Entrepreneur Gap. 2019. Morgan Stanley. www.morganstanley.com [Google Scholar]

- 101.Velázquez PP, Gupta G, Gupte G, Carson NJ, Venter J. 2020. Rapid Implementation of Telepsychiatry in a Safety-Net Health System During Covid-19 Using Lean. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wallerstein N, Duran B. 2010. Community-Based Participatory Research Contributions to Intervention Research: The Intersection of Science and Practice to Improve Health Equity. Am J Public Health. 100(Suppl 1):S40–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Watkins I, Xie B. 2014. eHealth Literacy Interventions for Older Adults: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 16(11):e3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Watkinson F, Dharmayat KI, Mastellos N. 2021. A mixed-method service evaluation of health information exchange in England: technology acceptance and barriers and facilitators to adoption. BMC Health Serv Res. 21:737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]