Abstract

The electrical current blockade of a peptide or protein threading through a nanopore can be used as a fingerprint of the molecule in biosensor applications. However, threading of full-length proteins has only been achieved using enzymatic unfolding and translocation. Here we describe an enzyme-free approach for unidirectional, slow transport of full-length proteins through nanopores. We show that the combination of a chemically resistant biological nanopore, α-hemolysin (narrowest part is ~1.4 nm in diameter), and a high concentration guanidinium chloride buffer enables unidirectional, single-file protein transport propelled by an electroosmotic effect. We show that the mean protein translocation velocity depends linearly on the applied voltage, resembling translocation of ssDNA. Using a supervised machine learning classifier, we demonstrate that single translocation events contain sufficient information to distinguish their threading orientation and identity with accuracies larger than 90%. Capture rates of protein are increased substantially when either a genetically encoded charged peptide tail or a DNA tag is added to a protein.

Editorial summary:

Full-length, unfolded proteins are slowly translocated through nanopores without enzymes and fingerprinted.

Introduction

High-throughput and long-read genomic sequencing1 methods include several single-molecule techniques2 in which the nucleotide sequence of individual DNA molecules is determined either by monitoring DNA replication in real-time3 or by passing a DNA strand through a nanopore detector4,5. But molecular characterization of the >104 proteins in the canonical human exome, with a multitude of protein isoforms6,7 and post-translational modifications (PTMs)8,9, requires new quantitative methods for protein counting, sequencing, and discrimination among various isoforms and PTMs10. Mass spectrometry (MS) is currently the gold standard method for these characterizations, which commonly require protein fragmentation, quantification, and sequence reconstruction. The high sensitivity of MS to minute protein quantities permits single-cell proteomics11. However, low peptide ionization rates and other limitations result in only a few percent sampling efficiencies12,13. Alternative approaches are needed to deliver a complete single-cell proteome without extensive fragmentation.

Nanopores have emerged as key components of new proteomics tools14. The methodology of nanopore DNA sequencing has been adapted to sense the amino acid composition of model peptides and proteins14-19. However, biological proteins are much more complex than DNA, given their diverse secondary structures, strong intramolecular interactions, and a heterogeneous distribution of the electrical charge along their polypeptide chains. Voltage20-23, temperature24, and chemical denaturation16,25-30 have been used to enhance the access of unfolded proteins to the nanopore constrictions. However, protein unfolding does not guarantee protein translocation because an unmodified protein cannot be electrophoretically driven through a nanopore in the same manner that a charged DNA in an electric field produces a steady electromotive force31. Enzyme-assisted unfolding and translocation of large proteins have been demonstrated using ClpXP as a motor to linearize and pull the protein through α-hemolysin32,33. Recent works using phi29 DNA polymerase34 or Hel308 DNA helicase35,36 have shown enzyme-mediated ratcheting or unwinding of peptide-DNA conjugates through the MspA nanopore. However, to date, enzyme-free readout of a full-length protein using a nanopore has not been achieved.

Here, we demonstrate an enzyme-free platform for single-file unidirectional transport of full-length proteins through a nanopore reader. Electroosmotic flow, enhanced by the use of GdmCl as a denaturant, drives protein transport through the nanopore, conferring uniform and slow (~10 μs/amino acid) single-file protein transport. The ionic current signals produced by the transport are found to carry the information about the protein sequencing, which we demonstrate by matching the signals produced by the N-terminus and C-terminus transport of the same protein, the transport of a double concatemer of the same protein, and by determining the composition of a binary protein mixture. With further development, our approach paves the way for single-molecule protein identification and quantification of the protein isoforms.

Results

Experimental setup for unfolding and transporting full-length protein through a nanopore reader

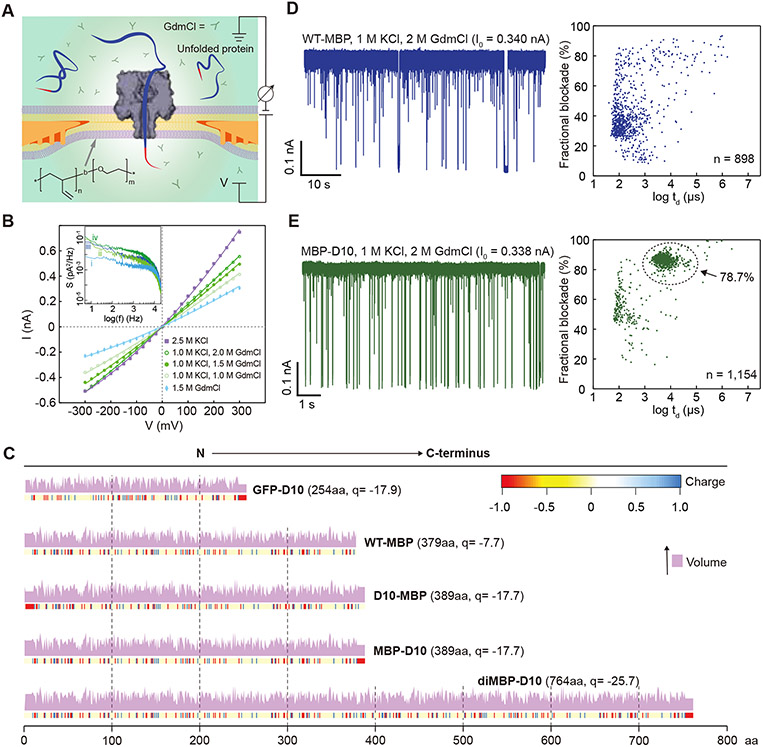

Our experimental setup (Figure 1A) comprises a wedge-on-pillar (WOP) membrane support37, a poly(1,2-butadiene)-b-poly(ethylene oxide) (PBDn-PEOm) block-copolymer bilayer that spans the aperture, as well as an inserted wild-type α-hemolysin channel, which is the nanopore used in our experiments. We chose this block copolymer membrane for its chemical compatibility with GdmCl buffers, and high voltage tolerance (>350 mV for 100 μm diameter bilayer membranes) when combined with the WOP support38. Also depicted in the figure is our use of high concentration GdmCl buffer, critical for protein unfolding. Figure 1B shows current vs. voltage curves for single α-hemolysin channels at different buffer conditions. All curves exhibit significant asymmetry, with higher current amplitudes at positive voltages. The impact of GdmCl on noise in α-hemolysin is moderate: The 10 kHz bandwidth noise at 300 mV is 7.2 pA for 2.5 M KCl and 10.7 pA for 1 M KCl + 2.0 M GdmCl, respectively. Power spectra at 0 mV and 300 mV for these two buffers (see inset) indicate a slight increase in the noise in the low-to-intermediate frequency regime (<5 kHz).

Figure 1.

Enzyme-free full-length protein translocation through nanopores. A) Schematic cut-away view of a PBDn-PEOm block-copolymer bilayer (inset shows polymer structure) suspended on the WOP aperture (orange depicts lipid solvent), with an α-hemolysin nanopore inserted into the bilayer. The guanidinium chloride (GdmCl) buffer unfolds the analyte proteins while leaving the α-hemolysin nanopore intact. A pair of Ag/AgCl electrodes generate transmembrane voltage and measure the ionic current through the nanopore. B) Current-voltage dependence of a single α-hemolysin channel at several buffer conditions (V is applied to the trans chamber). C) Graphical representations of the formal charges at pH 7.5 for the protein constructs used in this study in their unfolded (solvent accessible) state. A plot above each charge graph shows the relative amino acid volumes (pink). D) Current vs. time trace (left) and the fractional blockade vs. dwell time scatter plot (right) recorded from wild-type maltose binding protein (WT-MBP) at V = 175 mV, [WT-MBP] = 0.35 μM. Open pore current (Io) is indicated above each trace. E) Same as in panel D but for MBP containing a C-terminus aspartate tail (MBP-D10), [MBP-D10] = 0.35 μM. The scatter plot indicates the fraction of detectable events near the dashed circle.

Using the above experimental setup, we conducted nanopore translocation experiments on variants of the α-helix-rich maltose-binding protein (MBP) in its monomeric form (denoted as either MBP-D10 or D10-MBP, depending on the C- or N-terminus attachment of the D10 tail) and its dimeric form (diMBP-D10, with a GGSG linker between two MBP monomers). The nanopore translocation experiments were repeated using green-fluorescent protein (GFP), which stable β-barrel structure makes this protein notoriously challenging to unfold. Figure 1C shows the net charge (at pH 7.5)39 and length (number of aa's) of each protein, as well as pKa-based graphical profiles of the charge39 and relative volume40 of each aa residue.

The impact of a charged tail on protein threading is indicated in Figure 1D and 1E, where current traces for wild-type MBP (WT-MBP) and MBP-D10 are shown. While in both experiments, protein concentration was 350 nM, the capture rates for MBP-D10 (9.3 s−1μM−1) were ~80% higher than for WT-MBP (5.2 s−1μM−1). Further, WT-MBP events had a broad range of amplitudes and short durations (<1 ms), whereas MBP-D10 had nearly 79% of the events forming a tight distribution characterized by a ~85% fractional blockade and dwell times between 1 to 10 ms. Such reproducible dwell times and current amplitudes suggest a deterministic translocation process mediated by the insertion of the D10 tail, which is in agreement with earlier reports where charged tags, such as DNA oligomers22 or poly-aspartate tails32, were used to direct protein capture. However, modifying a full-length protein without any prior genetic engineering is crucial for a path to analysis of native proteins. We therefore demonstrate that DNA conjugation to a full-length protein tail is possible, albeit at low yields (~5-6%), by labeling WT-MBP with a dT20 DNA oligo (see SI, Figure S1 and Supplementary Note 1). We confirmed that the addition of the dT20 tail enhances threading of MBP through the pore, as indicated by an enriched cluster of events with similar dwell times and current blockades as observed for MBP-D10 (compare Figure 1E to SI Figure S2).

Influence of GdmCl concentration on complete protein unfolding

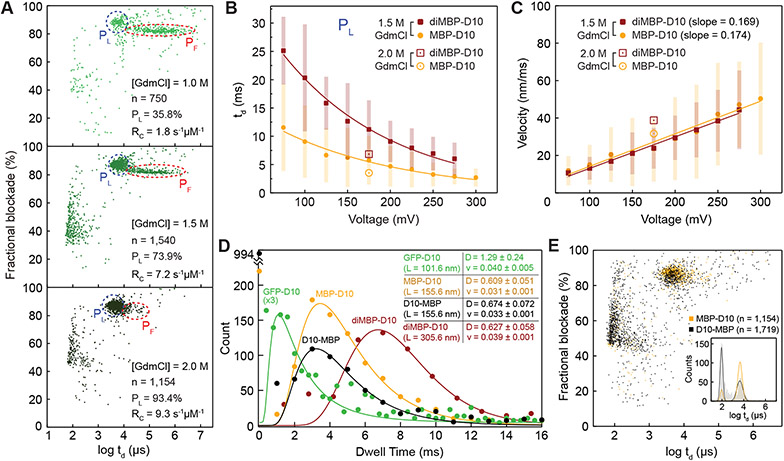

Bulk measurements suggest that MBP has an unfolding midpoint at 1.0 M GdmCl at room temperature, and that MBP fully denatures when GdmCl concentration exceeds ~1.2 M41,42. After adding MBP-D10 to the cis chamber, in Figure 2A, the current blockade vs. dwell time scatter plots (for 1.0 M, 1.5 M, and 2.0 M GdmCl, respectively) show two main distributions, highlighted by dashed red and blue circles, in addition to a very "fast" population at ~100 μs, which most likely corresponds to protein collisions with the pore entrance. Consistent with the scatter plots, the current traces in SI Figure S4 show two types of events (long and short). We assign the long-lived events (red dashed circle) to population PF, which encompass events from partially folded proteins. For the reasons described in the next paragraph, we ascribe the tight, shorter-lived population PL (blue dashed circle) to events produced by linearized, completely unfolded proteins. Since these two populations are generally well-resolved, we have determined the percentage of linear protein events PL as a function of GdmCl concentration (see SI, Figure S17). As shown in Figure 2A, PL increases with the GdmCl concentration from ~36% at 1.0 M GdmCl to >93% at 2.0 M GdmCl. The existence of one population at 2.0 M GdmCl suggests that the protein is fully unfolded during its translocation through the pore.

Figure 2.

Transport properties of unfolded protein analytes. A) Fractional current blockade vs. dwell time scatter plots for MBP-D10 in 1.0 M, 1.5 M, and 2.0 M GdmCl buffer (+1 M KCl). Red and blue ovals show populations that correspond to PF (partially folded) and PL (linear or unfolded) states of MBP-D10, respectively. [MBP-D10] = 0.7 μM for 1.0 M GdmCl and 0.35 μM for 1.5, 2.0 M GdmCl experiments. B) Mean dwell time vs. voltage with exponential fitting for the PL populations of MBP-D10 and diMBP-D10, respectively (error bars represent the FWHM of the distribution fits). C) Protein transport velocities calculated from estimated protein contour length and observed dwell times as a function of applied voltage (error bars are based on the dwell time distribution widths shown in B). Buffer conditions for data shown in B and C are 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 1 M KCl, and either 1.5 or 2.0 M GdmCl. For the latter, data at only one voltage (175 mV) are shown. D) Dwell time histograms for GFP-D10, MBP-D10, D10-MBP, and diMBP-D10 along with the mean diffusion coefficients (nm2/μs) and velocities (nm/μs) determined from fits to the 1D Fokker-Planck equation53,78,79. E) Fractional current blockade vs. dwell time scatter plots and dwell time histograms for C-terminus (MBP-D10) vs. N-terminus (D10-MBP) threading and transport of full-length MBP. Experiments in D and E were performed in 1 M KCl, 2.0 M GdmCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, under a 175 mV bias applied to the trans chamber.

Evidence of steady voltage-driven protein translocations

Figure 2B plots the mean dwell time of the PL population as a function of voltage for experiments conducted using an MBP monomer (MBP-D10) or a dimer (diMBP-D10) (see SI Figure S11 for the dwell time histograms). The average dwell time of population PL decreases as the voltage increases. The dwell time for the MBP dimer (di-MBP-D10) is a factor of two larger than that for the MBP monomer (MBP-D10). In contrast, the dwell time of events attributed to partially folded proteins, PF, are much larger for both MBP-D10 and diMBP-10 than for the unfolded events at all voltages and exhibit a steeper voltage dependence than the PL population (SI Figure S12). The plot of the protein mean "velocity", Figure 2C, calculated by dividing the protein contour length (0.34 nm per amino acid) by the dwell time (from Figure 2B) shows a linear dependence on voltage for both monomeric and dimeric MBP, thus indicating that the velocity does not depend on protein length. The electrophoretic mobility of a protein is described by

| (Eq. 1) |

where d is the protein’s contour length, and d/t = ve is the protein translocation velocity43. Estimating the electric field E as the ratio of the voltage to the length of the α-hemolysin lumen, D = 5 nm, we obtain

| (Eq.2) |

where ve/V is the slope of the fits from Figure 2C. Using Eq. 2, we find the electrophoretic mobility of MBP-D10 and diMBP-D10 at μm = 8.70 × 10−9 cm2/V·s and μd = 8.45 × 10−9 cm2/V·s, respectively. Moreover, two extra datapoints at 175 mV are shown for 2 M GdmCl condition (Figure 2C), indicating faster translocating speeds. The uniform translocation speed, and its linear relationship with voltage resembles ssDNA translocation through α-hemolysin44-46. Finally, a plot of the event rates (See SI, Figure S18) reveals a low-voltage regime characterized by short-lived high-frequency collisions and an exponentially increasing capture rate at higher voltages (V > 150 mV), which suggests an entropic barrier for capture47.

In Figure 2D, we present dwell-time distributions for GFP-D10 (254 aa), MBP-D10 (389 aa), D10-MBP (389 aa), and diMBP-D10 (764 aa) obtained at 175 mV applied voltage and 2 M GdmCl denaturant concentrations. We found no dependence of the protein transport time on its orientation of entry (MBP-D10 vs. D10-MBP), which differs from the orientation dependence of DNA transport through α-hemolysin48. This is supported by Figure 2E, which shows current blockade vs. dwell time scatters for MBP-D10 and D10-MBP. To a large extent, there is an overlap in the dwell time distributions, except that D10-MBP is captured less effectively, resulting in a greater fraction of collisions that appear as short-lived pulses (~100 μs) with lower current blockades. However, it is noteworthy that protein translocation from either direction proceeds with the same speed. Drift velocities for all molecules in this study are in the range of 0.031 – 0.04 nm/μs. The extended backbone distance between amino acids in a protein chain (0.34 nm)49 translates to a mean residence time of ~10 μs per amino acid in the pore. This average translocation velocity is roughly an order of magnitude smaller than that measured for a ssDNA transport through α-hemolysin (0.15 nm/μs) 44, which provokes the idea of enzyme-free protein readout using high-bandwidth electronics.

Electroosmotic flow drives protein transport

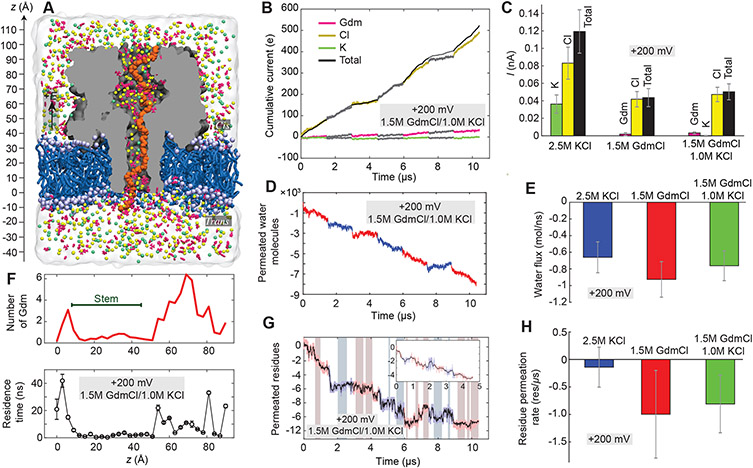

To determine how Gdm+ ions enable unidirectional transport of unfolded peptides, we built seven all-atom simulation systems, each containing a different 52-residue fragment of the MBP protein (Table S1) threaded through α-hemolysin, a lipid membrane, and 1.5 M GdmCl/1 M KCl electrolyte (Figure 3A). For comparison, two variants of each system were built, differing by the electrolyte solution composition (1.5 M GdmCl and 2.5 M KCl). Each design was equilibrated using the all-atom MD method50 and then simulated under a +200 mV bias for approximately 1,500 ns (see Materials and Methods for details).

Figure 3.

MD simulation of ion, water, and peptide transport through α-hemolysin. A) All-atom model of α-hemolysin (gray) containing a fragment of the MBP protein (orange), embedded in a lipid membrane (blue) and submerged in the 1.5 M GdmCl, 1 M KCl electrolyte mixture. B) Total charge carried by ion species in seven independent MD simulations differing by the sequence and initial conformation of the MBP fragment. Hereafter each trace is shown using two alternating colors to indicate data from independent trajectories. The traces are added consecutively to appear as a continuous permeation trace. The slope indicates the average current. C) Average ionic current for the three electrolyte conditions. Hereafter the average and the standard error are calculated considering each trajectory-averaged value as a result of an independent measurement. D) Number of water molecules permeated through the α-hemolysin constriction (residues 111, 113, and 147). Negative values indicate transport in the negative z-axis direction (defined in panel A). E) Average water flux for each electrolyte condition. F) The number of Gdm+ ions within 3 Å of the nanopore inner surface (top) and their average residence time (bottom) along the transmembrane pore of α-hemolysin. G) Number of amino acids permeated through α-hemolysin constriction under a +200 mV bias in the 1.5 M GdmCl/1.0 M KCl electrolyte simulations. Highlights indicate the parts of the trajectories where the peptide density within the stem (8<z<45 Å) of α-hemolysin is constant; the inset shows consecutive addition of the highlighted regions. H) the Average number of translocated amino acids for each electrolyte condition.

In the case of the GdmCl/KCl electrolyte, 94% of the blockade current was carried by Cl− ions, whereas the current carried by Gdm+ and K+ ions was 6 and 0%, respectively (Figure 3B). Similarly, strong ionic selectivity was observed for pure GdmCl electrolyte (Figure 3C, and SI Figure S20). The ionic selectivity was less pronounced but still substantial (70 and 30% for Cl− and K+ currents, respectively) for pure KCl. Consistent with the ion selectivity, we observed strong electroosmotic effects in all three systems (Figure 3D, E, and SI Figure S21). Further analysis found Gdm+ ions to accumulate at the inner nanopore surface, particularly near the termini of the α-hemolysin stem, see Figure 3F (top) and SI Figure S22. In the same regions, individual Gdm+ ions were observed to remain bound to the nanopore surface for considerable (> 10 ns) intervals of time, see Figure 3F (bottom). In all systems, the local concentrations of ionic species were found to satisfy the local electroneutrality condition (SI Figure S23). However, in the GdmCl/KCl system, K+ ions were almost excluded from the α-hemolysin stem (SI Figure S23), which explains their negligible current. Thus, binding of Gdm+ ions to the inner nanopore surface renders the surface positively charged. That surface charge is compensated by much more mobile chloride ions that carry most of the ionic current and produce a strong electroosmotic effect.

The electroosmotic effect produced by Gdm+ binding produced a small yet measurable net transport of the unfolded protein fragments through the nanopore. We next computed the number of residues translocated through the nanopore constriction as a function of simulation time (Figure 3G and SI Figure S24). To exclude the effect of peptide chain shrinking or stretching, we identified the parts of the simulation trajectories where the number of peptide residues within the α-hemolysin stem remained approximately constant (SI Figure S25). Averaged over such constant-density trajectory fragments, the peptides were found to move with the average rate of 1.0+/−0.8 and 0.8+/−0.5 residues/μs for pure and mixed GdmCl electrolytes, respectively, and 0.1+/−0.4 residues/microsecond for pure KCl (Figure 3H).

Protein-specific current signals

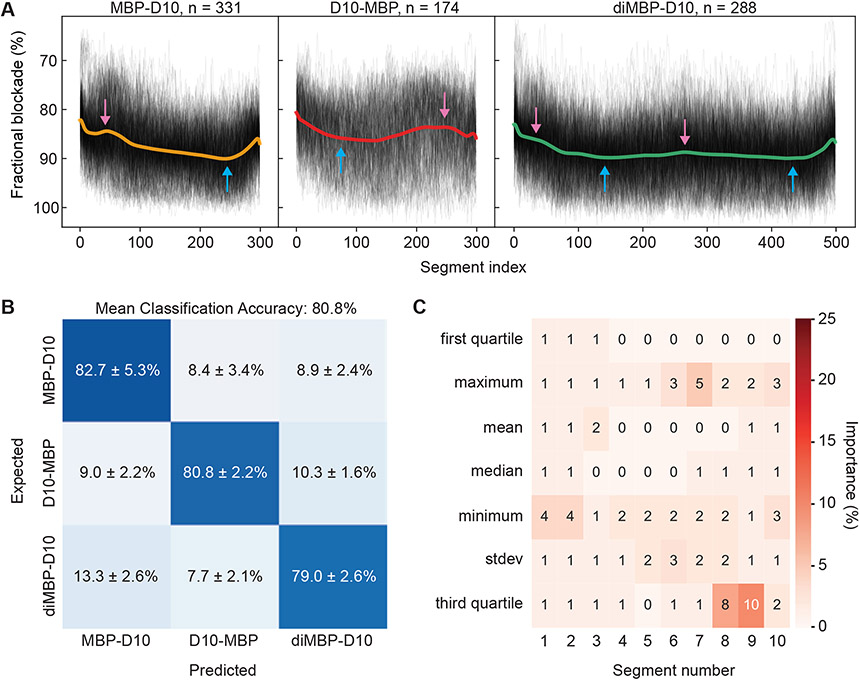

In order to extract an “average shape” of ionic current signals produced by the translocation of C- tagged MBP (MBP-D10), N- tagged MBP (D10-MBP), and C-tagged MBP dimer (diMBP-D10), their barycenters (Fréchet means) were computed using the Soft Dynamic Time Warping (SDTW) metric51. The result of the barycenter computation is a smooth curve, representing the centroid, or the “essence” of the translocation event shapes in the dataset. A barycenter for each of the variant datasets is shown as a solid curve in Figure 4A, superimposed on resampled events shown in the background (semi-transparent, black). The event selection criteria (dwell time and current maximum ranges), the number of passing events, and computation parameters, are listed in Table S4. We screened events with a narrow range of dwell times near the mean of each variant’s distribution (3-5 ms for MBP-D10 and D10-MBP, and 6-9 ms for diMBP-D10), which later allowed the SDTW algorithm to compute a clear and distinct signature shape for each variant. The current traces of the selected events were then resampled via interpolation to a segment count proportional to the average duration (300 points for MBP-D10 and D10-MBP, and 500 points for diMBP-D10). Resampling reduces the effect of dwell-time variation on this SDTW computation. The resulting barycenter curves show a trend of how the events of each protein type tend to progress, on average. Looking at the positioning of the local maxima and minima (pink and blue arrows, respectively), as well as the slope in the middle of the barycenter, we note that MBP-D10 and D10-MBP events show matching opposite trends (Figure 4A, left and middle panel, respectively). Whether due to the proteins remaining secondary structure in the pore, or purely due to sequence variation, the opposing current blockage trends are a strong indication of directional protein translocation. Further, the skewed “W” shape of diMBP-D10 barycenter and the position of its local minima and maxima appears similar to the MBP-D10 barycenter but repeated twice, especially the “bumps” in the beginning and the middle of the barycenter (Figure 4A, right panel).

Figure 4.

Unidirectional translocation and discrimination of MBP variants. A) Soft-DTW barycenters (solid curves) showing resampled events of MBP-D10 (left), D10-MBP (middle) and diMBP-D10 (right), with their respective events superimposed in the background (black). The positions of identified maxima (pink arrows) and minima (blue arrows) are shown. B) Three-way confusion matrix representing the mean classification accuracy of a multiclass gradient boosting classifier (GBC) trained to discriminate MBP-D10, D10-MBP, and diMBP-D10 (mean+/−standard deviation of 9 GBC models, each trained and tested on 80% of the data from a reshuffled dataframe, shown in SI Figure S27). C) A heatmap showing the relative importance of each feature used to generate the multiclass GBC model for discrimination of MBP variants (all 70 feature importance values sum to 100; shown percentages are rounded to the nearest integers). Each column of the heatmap represents a segment index of the event, and each row represents a statistical parameter extracted from every segment (refer to SI Figure S27 for further details on features). All experiments were performed in 1.0 M KCl, 2.0 M GdmCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5 and under a 175 mV bias applied to the trans chamber.

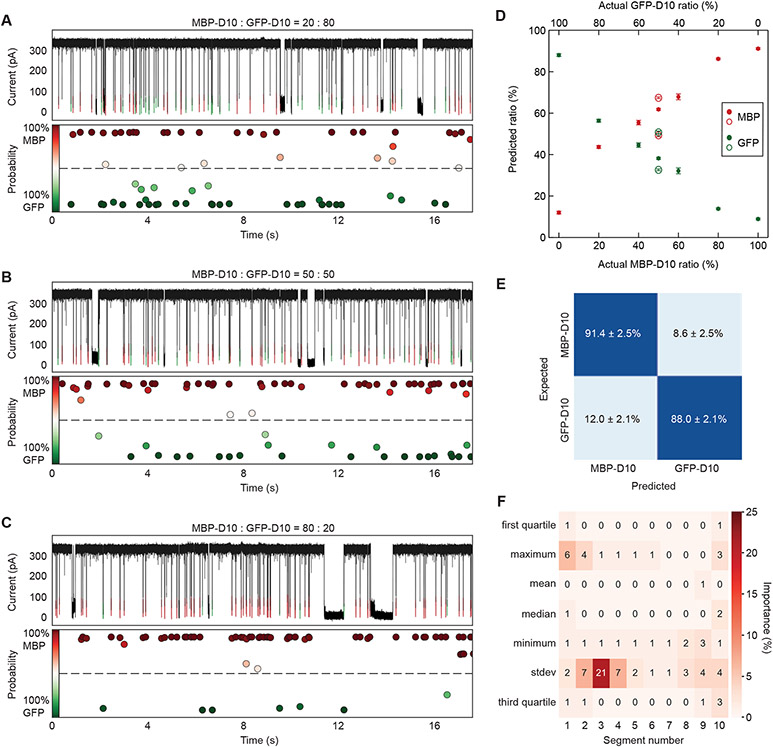

To investigate whether the signal properties from single events comprise sufficient information to discriminate among different protein variants and protein classes, we employed supervised machine learning (ML). A gradient boosting classifier (GBC) was trained and tested for discrimination among MBP variants (MBP-D10, D10-MBP, and diMBP-D10) and distinguishing MBP-D10 from GFP-D10 in a binary mixture. Both GBC models were generated and evaluated with features extracted from labeled translocation events recorded one protein type at time, where 80% of the data were used to train the model and the remaining 20% were withheld for testing the model’s accuracy (see SI Supplementary Note 4). While on a population-wide analysis, dwell time alone could inform on the ratio of protein types in a binary mixture (see SI Figure S26), single-molecule identification requires more information from the signal. Hence, blockade-based features from translocation events (dwell time ranging between 300 μs and 20 ms) were used to train and test both GBC models. Specifically, each event was divided into ten segments of equal length and seven statistical parameters from every segment were extracted, creating a feature space comprised of 70 dimensions for GBC model input (see SI, Figure S27 and Supplementary Note 4).

As confusion matrices in Figure 4B and Figure 5E show, mean classification accuracies of 80.8% and 89.6% were achieved with GBC models trained for three-way classification of MBP variants and two-way classification of MBP-D10 and GFP-D10, respectively. Each confusion matrix is an average of nine reshuffled combinations of samples allocated into the training set and testing set (see SI, Supplementary Note 4 and Figures S28 and S29). We investigated the relative importance of each feature for GBC prediction in each case (Figure 4C and Figure 5F). We found the third quartile value in the 8th and 9th event segments to have the highest predictive power for discrimination of MBP variants. This suggests that there is a distinguishable blockade current near the end of MBP-D10, D10-MBP and diMBP-D10 translocation. In contrast, the current standard deviation of the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th event segments had the greatest influence on GBC classification of MBP-D10 and GFP-D10. To support this result, we observed the greatest difference in local volume standard deviation to occur around these specific segments (see SI, Figure S30 and S31).

Figure 5.

Single-molecule fingerprinting of full-length MBP-D10 and GFP-D10. A-C) Post-training GBC classification results for unlabeled MBP-D10 (red) and GFP-D10 (green) mixture experiments at 20:80 (A), 50:50 (B) and 80:20 (C) ratios with a probability classification estimate associated with each translocation event. D) Percentage of MBP-D10 (red) to GFP-D10 (green) predicted by GBC model (shown on the y-axis) when applied to different MBP-D10:GFP-D10 ratio experiments. Each marker is the result of 9 GBC models, each fit with 80% of the training data from a reshuffled dataframe containing features from pure MBP-D10 and GFP-D10 experiments (mean+/− standard deviation). Experiments conducted on different days at 50:50 ratio are shown as hollow markers, highlighting experimental variability. Refer to SI Table S6 for sample size of events parsed for each ratio experiment. E) Two-way confusion matrix representing the mean classification accuracy of a GBC model trained to discriminate MBP-D10 and GFP-D10 (mean+/−standard deviation of 9 GBC models, each trained and tested on 80% of the data from a reshuffled dataframe, shown in SI Figure S28). F) A heatmap showing the relative importance of each feature used to generate the multiclass GBC model for discrimination of MBP-D10 and GFP-D10 (all 70 feature importance values sum to 100; shown percentages are rounded to the nearest integers). Each column of the heatmap represents a segment index of the event, and each row represents a statistical parameter extracted from every segment (refer to SI Figure S27 for further details on features). All experiments were performed in 1.0 M KCl, 2.0 M GdmCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5 and under a 175 mV bias applied to the trans chamber. The combined concentration of MBP-D10 and GFP-D10 for every ratio experiment is 0.70 μM.

To validate the discrimination capability of the trained model, we tested its performance on unlabeled mixture experiments. We note that simply deploying the model on a 50:50 mixture would not provide any useful information. Instead, we applied the trained GBC model on unlabeled events from mixture experiments containing different MBP-D10:GFP-D10 molar ratios and expected the classification ratios to follow the same trend. Figures 5A-C show experimental traces after GBC classification for experiments with 20:80 (A), 50:50 (B), and 80:20 (C) MBP-D10 (red) to GFP-D10 (green) mixture, with the model’s confidence score for each call labeled below the trace (see SI, Supplementary Note 4 and Table S6, S7). Plotting the ratio of MBP-D10 to GFP-D10 predicted by the model versus the true concentration of MBP-D10 (Figure 5D), we observe ~10% error by the model at an actual MBP-D10 ratio of 0%, followed by a trend where the number of MBP-D10 events called by the model increases roughly linearly with the actual concentration of MBP-D10 (as expected), and a saturation at around 90% when the actual ratio of MBP-D10 is 100%. Model calls where MBP-D10 is higher than expected (20%, 40%, and 50%) could be attributed by the higher capture rate observed with MBP-D10 in comparison to GFP-D10 (SI Figure S18). Example events from the training sets and mixture classification results are provided in SI Figure S32. The total event ratio predicted by the GBC model for 50:50 mixture experiment is in excellent agreement with the respective population size obtained by integrating the mixture experiment’s dwell time histogram after fitting with the 1D drift-diffusion model52-55 (see SI, Supplementary Note 2 and Figure S19).

Discussion

The commercial success and maturity of nanopore-based nucleic acid sequencing, with its ability to directly read native strands at full length, sparked a sizable interest in developing nanopore-based proteomics. If realized, the single-molecule aspect of nanopore-based proteomics could offer solutions to shortcomings of mass-spectrometry and Edman degradation-based methods, such as quantification of protein isoforms and detection of post-translational modifications14. The goal of our study was to identify and evaluate an enzyme-free method to translocate full-length proteins in a linearized state through nanopores, with downstream fingerprinting, isoform detection, and ultimately protein sequencing applications in mind. We showed that our protein sensing platform which consists of a wedge-on-pillar aperture for membrane support 37, a synthetic polymer bilayer membrane38 with a single insertion of a wild-type α-hemolysin nanopore can withstand and function under denaturant (GdmCl) concentrations that are high enough to unfold analyte proteins. We further showed that capturing and initiating the threading of the unfolded proteins through the nanopore sensor required addition of a charged tail, which forces the translocation to start from the tagged terminus. However, both our experimental results and molecular dynamics simulations showed that translocation progression of the protein after threading initiation no longer depended on the charged tail. Instead, the significant voltage-driven electro-osmotic flow generated by the presence of Gdm+ ions within the pore lumen applies the stretching/driving force to complete the protein translocation. Lastly, we proved that the current blockade signals from protein translocation events contained distinct information which a machine-learning model could use to classify single protein molecules.

In our model experiments, we showed protein threading is improved enormously by genetically engineering a charged D10 tail on our proteins. However, our platform can serve as an analytical tool only if it can measure wild-type proteins present in living organisms, which requires a general method to attach a charged tail to the N- or C-terminal of proteins without prior genetic engineering. In this work, we tagged a dT20 DNA oligo to the N-terminal of MBP and proved that it enhances protein capturing. Despite facing a low labeling efficiency (~5-6%) now, the potential of DNA-protein terminal conjugation methodology is highly important for native protein analysis, and future work is needed to optimize it or develop more efficient poly-ionic tags and optimized end-tagging chemistry.

For the protein molecules studied here, we find a linear relationship between the average protein velocity during translocation and voltage, which does not depend on either protein length or orientation of entry (MBP-D10 vs. D10-MBP). The smooth motion of proteins through the nanopore is driven by electroosmotic force enhanced by the binding of Gdm+ ions to the lumen of the α-hemolysin, as elucidated by MD simulations. The mean transport speeds are ~10 μs/amino acid, much slower than DNA transport, perhaps slow enough to collect several current datapoints for each protein segment while at the pore constriction. With improved measurement time resolutions that could be achieved by reducing the noise of our apparatus, enzyme-free protein “scanning” at high measurements bandwidths may prove useful for identifying proteins and resolving variants. Further, as seen from the haziness of the overlaid resampled events in the background traces of Figure 4A, transport of a given molecule is likely to have some velocity variations along the translocation coordinate. As with nanopore-based DNA and RNA sequencing, it may be possible to eliminate the effect of the non-constant velocity in protein translocation using a neural network analysis pipeline. However, the highest translocation velocities must not exceed the bandwidth capacity of the nanopore instrument to avoid signal loss.

In an ideal nanopore-based protein sequencing or fingerprinting tool, the current blockade signals would contain the protein’s sequence or subunit information. Here, we pointed out that both resolution and bandwidth limitations in our experimental setup would limit the degree of access to that information. However, we observed that general trends in the shape of the blockade signal from protein variants are distinct and reproducible, and used the blockade signals within events in a dynamic time warping analysis to illustrate the unidirectionality of protein translocation, achieved by the choice of where to place the D10 terminal tag. We then used features calculated from the blockade signals as the input to our GBC model to show that the embedded information in the signal, albeit convoluted, could result in classification accuracies of 80.8% among the three MBP variants and 89.6% between MBP-D10 and GFP-D10. Deploying the trained GBC model on binary mixtures of MBP-D10 and GFP-D10 at different molar ratios showed that the classification results are quantitative and in agreement with the relative molar ratios of proteins in the experiment. Based on these results, we speculate that our platform – in its current form and sensing resolution – may be capable of quantitative detection of protein isoforms, provided that a sufficiently large set of molecular standards exists which could be used for signal training. However, acquiring such data demands not only pore multiplexing and higher throughput, but also efficient terminal tagging chemistry for full-length native proteins. We noted that GdmCl both facilitates protein unfolding and generates a stretching/driving force through electroosmotic flow. This electroosmotic flow that can drive an unstructured protein chain through a pore is important not only in the enzyme-free approach we presented here, but also in keeping a protein chain taut at the pore during enzyme-mediated protein sequencing. As apparent in the data by Nivala et al.32,33, unfoldase-mediated protein translocation (pull-through) is susceptible to the jamming of the trailing folded or unfolded parts of the protein into the pore lumen, which modulates the current and corrupts the “favored” blockade signal generated by the protein regions residing in the pore constriction site. We speculate that addition of GdmCl to the cis-side of the pore in such unfoldase-mediated nanopore systems could initiate the electroosmotic flow and help prevent this jamming. For this to work, it may be required that the electrolyte concentrations and/or applied voltage are adjusted to generate an electroosmotic flow opposite to the pulling force of the unfoldase, which will ensure that the peptide chain in the pore is stretched. Further, unlike large detergent-like micellar denaturants such as SDS, Gdm+ ions are small, and we do not anticipate them to heavily coat the interacting protein side chains to degrade the readout signal quality. We finally note here that working the highly denaturing conditions of GdmCl are compatible not only with α-hemolysin but also MspA, which offers a potentially higher resolution while maintaining its structure and function in 2 M GdmCl56. Other improvements such as changing the electrolyte type57, pore variant58-60, and voltage waveform61, can be made to further enhance the ability of our method to obtain unique fingerprint signatures or sequence from full-length proteins, which would usher in a new era in single-molecule proteomics.

Methods

Polymer bilayer painting and nanopore measurement.

The 100 μm SU-8 wedge-on-pillar aperture supported by a 500 μm-thick Si chip with a square open window37 was mounted on our custom-designed fluidic cell, sealing properly to separate cis and trans chambers. Both sides of the aperture were pretreated with 4 mg/ml poly(1,2-butadiene)-b-poly(ethylene oxide) (PBD11–PEO8) block-copolymer (Polymer Source) dissolved in hexane to coat the aperture with a dry and thin polymer layer. The cis and trans chambers were filled with GdmCl electrolyte (all contain 1 M KCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5), and a pair of Ag/AgCl electrodes were immersed in the electrolyte and connected to an Axon 200B patch-clamp amplifier. The polymer membrane was painted across the aperture using 8 mg/ml polymer dissolved in decane. At least 60 mins waiting time were required until the polymer membrane thinned to a capacitance value of 60 – 80 pF. After verification of bilayer formation, 0.5 μl of 50 μg/ml α-hemolysin (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the cis chamber, and an ion conductance jump marked single pore insertion. A denatured protein sample (incubated in GdmCl buffer before use) was added to the cis chamber and mixed gently by pipetting. Current signals were low-pass filtered at 100 kHz using the Axopatch setting and digitized at 16-bits and 250 kHz sampling rate using a National Instruments Data Acquisition card and custom LabVIEW-based software that records and saves all raw current data and acquisition settings. In further data analysis digital low-pass filtering was used to further reduce the noise.

Cloning of the GFP and MBP constructs.

All primers (Eurofins MWG Operon) used in this study are listed in Table S1. The N-terminal 10-aspartate MBP (D10-MBP), C-terminal 10-aspartate MBP (MBP-D10), and C-terminal 10-aspartate GFP (GFP-D10) constructs were obtained by mutagenesis polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using pT7-MBP or pRSETB-GFP as the template plasmid. The PCR reaction mixtures were subjected to DpnI digestion for 3 h at 37 °C to degrade the template plasmids. The digested samples were then transformed into chemically competent E. coli DH5α cells. The desired mutant plasmids were isolated from colonies and verified by DNA sequencing.

The C-terminal MBP-D10 dimer construct (diMBP-D10) was generated as follows: the first mutagenesis PCR was performed using pT7-hisMBP as the template to remove the stop codon and add a flexible linker GGSG to the C-terminus of the MBP gene. The PCR products were digested with DpnI and transformed into E. coli DH5α cells resulted in a plasmid pT7-hisMBPggsg containing the hindIII and Sfbl restriction sites right after the GGSG linker gene. The second PCR was performed with pT7-MBP as the template to introduce HindIII and Sfbl cutting sites at the two ends of the MBP gene and add a D10 at the c-terminal to the MBP fragment. The PCR products and the plasmid pT7-hisMBPgsgg were digested with HindIII and Sfbl and ligated by T4 ligase. The ligated products were transformed into chemically competent E. coli DH5α cells. The mutant plasmid pT7-diMBP-D10 was verified by enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing.

Expression and purification of GFP and MBP proteins.

GFP and MBP protein variants (Table S2) were expressed and purified using similar protocols. Briefly, plasmids were transformed into chemically competent BL21(DE3) E. coli cells. The cells were grown in 1 L of LB medium at 37 °C until the OD600 reached 0.6 and induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside. The temperature was then decreased to 16°C for overnight expression. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 13000 RPM for 25 min. The cell pellets were used for protein purification or frozen at −20 °C for future use. Cells were resuspended in 50 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl buffer, and lysed via sonication to purify proteins. The lysate was centrifuged at 13000 RPM for 25 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm syringe filter (CELLTREAT Scientific Products) and then loaded to a Ni-NTA affinity column (ThermoFisher scientific) equilibrated with buffer 50mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl. MBP-D10, D10-MBP and diMBP-D10 were eluted in buffer 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 150 mM imidazole. GFP-D10 was eluted in buffer 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole. After Ni-NTA chromatography, MBP-D10, D10-MBP, and GFP-D10 exhibited more than 95% purity on SDS-PAGE, while the eluted diMBP-D10 fraction contained multiple low-molecular impurity bands. The eluted samples were run on a preparative 12 % SDS-PAGE to remove these impurity proteins. The band containing the full-length diMBP-D10 was cut out, and the protein was extracted from the gel with buffer 50mM Tris-HCl (pH8.0), 8M urea by incubating the gel and the extraction buffer at room temperature overnight. The supernatant containing the protein was collected by centrifuging the samples at 13000 RPM for 30 min. Protein concentrations of all samples were determined by A280 with Nanodrop and stored at −80 °C for future use.

MD simulation.

All MD simulations were performed using the molecular dynamics program NAMD262, a 2 femtosecond integration timestep, periodic boundary conditions, CHARMM3663 force field, and a custom non-bonded fix (NBFIX) corrections for K, Cl, and Gdm ions64. SETTLE algorithm65 was used to maintain covalent bonds to hydrogen atoms in water molecules, whereas RATTLE algorithm66 maintained all other covalent bonds involving hydrogens. The particle-mesh Ewald67 method was employed to compute long-range electrostatic interactions over a 1.2 Å grid. All van der Waals and short-range electrostatic interactions were evaluated every time step using a cutoff of 12 Å and a switching distance of 10 Å; Full electrostatics were evaluated every second-time step.

The all-atom models of α-hemolysin suspended in a lipid bilayer membrane were built using CHARMM-GUI68. The initial structural model of α-hemolysin was taken from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 7AHL)69. After adding missing atoms and aligning the primary principal axis of the protein with the z-axis, the protein structure was merged with a 15×15 nm2 patch of a pre-equilibrated 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) lipid bilayer. The protein-lipid complex was then solvated in a rectangular volume of ~78,500 pre-equilibrated TIP3P water molecules70. Gdm+, K+, and Cl− ions were added at random positions corresponding to target ionic concentrations. Additional charges were introduced to neutralize the system. Each final system was 15×15×18 nm3 in volume and contained approximately 300,000 atoms. Upon assembly, the systems were initially equilibrated using the default CHARMM-GUI's protocol. Specifically, the systems were subjected to energy minimization for 10,000 steps using the conjugate gradient method. Next, lipid tails and protein side chains were relaxed in a 2.5 ns pre-equilibration simulation that was run while restraining the protein backbones and lipid head groups. This step was followed by a 25 ns simulation in the NPT (constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature) ensemble using the Nosé-Hoover Langevin piston pressure control71. In all simulations, the temperature was maintained at 298.15 K by coupling all non-hydrogen atoms to a Langevin thermostat with a damping constant of 1 ps−1.

The atomic coordinates of the maltose-binding protein (MBP) were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (entry 1JW4)72. The missing hydrogen atoms were added using the psfgen plugin of VMD73. The protonation state of each titratable residue was determined using PROPKA74 according to the experimental pH conditions (7.5 pH). Next, the protein was split into seven peptide fragments producing six 53-residue and one 52-residue fragments. The N-terminal of each peptide was terminated with a neutral acetyl group (ACE patch), whereas the C-terminal was terminated with an N-methyl group (CT3 patch). Each peptide was stretched using constant velocity SMD in vacuum, followed by 5 ns equilibration in a 1.5 M GdmCl solution. During the 150 ps SMD run, the C-terminal of the peptide was kept fixed. At the same time, the N-terminal was coupled to a dummy particle utilizing a harmonic potential (kspring = 7 kcal/(mol Å2)), and the dummy particle was pulled with a constant velocity of 1 Å/ps. At the end of the equilibration step, each peptide fragment had a contour length of approximately 167 Å, ~3.16 Å per residue. Next, we used the phantom-pore method48 to convert the geometrical shape of the α-hemolysin nanopore to a mathematical surface. To fit the stretched peptide into the α-hemolysin pore, the phantom pore surface was initially made to represent a nanopore that was 1.4 times wider than the pore of α-hemolysin. During a 2 ns simulation, the phantom pore was gradually shrunk to match the shape of the α-hemolysin nanopore. At the same time, all atoms of the peptide and all ions laying outside the potential were pushed toward the nanopore center using a constant 50 pN force. At the end of the simulation, each peptide fragment and all guanidinium ions residing within 3 Å of any peptide atom were placed inside the pre-equilibrated α-hemolysin system having the peptide's backbone approximately aligned with the nanopore axis. Before the production runs, each system was equilibrated for 10 ns in the NPT ensemble at 1.0 bar, and 298.15 K with all Cα atoms of the α-hemolysin protein restrained to the crystallographic coordinates.

All production simulations were carried out in the constant number of particles, volume, and temperature ensemble (NVT) under a constant external electric field applied normal to the membrane, producing a ±200 mV transmembrane bias. To maintain the nanopore's structural integrity, all protein's Cα atoms were restrained to exact coordinates as in the last frame of the equilibration trajectory using harmonic potentials with spring constants of 1 kcal/(mol Å2). The ionic currents were calculated as described previously50. The quantify protein translocation, we defined the number of residues translocated as the number of non-hydrogen backbone atoms passing below the α-hemolysin constriction divided by the total number of non-hydrogen backbone atoms in one residue. The constriction's z-coordinate was defined by the center of mass of the backbone atoms of residues 111, 113, and 147. The concentration profile and guanidinium binding analyses were carried out using in-house VMD scripts. All MD trajectories were visualized using VMD73.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Caroline McCormick for assistance with editing the manuscript for clarity, and Dr. Nikolai Slavov for helpful discussions regarding protein sequencing. We acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health: HG0011087 (MW); GM115442 (MC), and the National Science Foundation: PHY-1430124 (AA). The supercomputer time was provided through the XSEDE allocation grant (MCA05S028) and the Leadership Resource Allocation MCB20012 on Frontera of the Texas Advanced Computing Center.

Data availability

All data used in this manuscript are available for download at https://figshare.com/s/5cd39ee415c62a316a6f.

Code availability.

All data parsing (excluding DTW and GBC) were performed using the Pyth-ion package (https://github.com/wanunulab/Pyth-Ion) and figures were generated using Igor. For analysis, the raw 100 kHz nanopore current data was further low-pass filtered to 10 kHz using the low-pass filter function in Pyth-ion. DTW and GBC analyses were conducted via python scripts written and documented in Jupyter Notebooks, tslearn (v0.5.2)75, SciKit-Learn (v1.0.2)76, and a modified version of the PyPore77 nanopore data analysis library. The Jupyter notebook and associated files are available on GitHub (https://github.com/wanunulab/protein-gd). A detailed description of the DTW and GBC analyses is provided in SI Section 6.

References

- 1.Shendure J et al. DNA sequencing at 40: past, present and future. Nature 550, 345–353, doi: 10.1038/nature24286 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ameur A, Kloosterman WP & Hestand MS Single-Molecule Sequencing: Towards Clinical Applications. Trends in Biotechnology 37, 72–85, doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.07.013 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eid J et al. Real-Time DNA Sequencing from Single Polymerase Molecules. Science 323, 133, doi: 10.1126/science.1162986 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venkatesan BM & Bashir R Nanopore sensors for nucleic acid analysis. Nature Nanotechnology 6, 615–624, doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.129 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deamer D, Akeson M & Branton D Three decades of nanopore sequencing. Nature Biotechnology 34, 518–524, doi: 10.1038/nbt.3423 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith LM et al. Proteoform: a single term describing protein complexity. Nature Methods 10, 186–187, doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2369 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogaert A, Fernandez E & Gevaert K N-Terminal Proteoforms in Human Disease. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 45, 308–320, doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2019.12.009 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tolsma Thomas O. & Hansen Jeffrey C. Post-translational modifications and chromatin dynamics. Essays in Biochemistry 63, 89–96, doi: 10.1042/ebc20180067 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conibear AC Deciphering protein post-translational modifications using chemical biology tools. Nature Reviews Chemistry 4, 674–695, doi: 10.1038/s41570-020-00223-8 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacCoss MJ, Alfaro J, Wanunu M, Faivre DA & Slavov N Sampling the proteome by emerging single-molecule and mass-spectrometry methods. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.00530 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slavov N Single-cell protein analysis by mass spectrometry. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 60, 1–9, doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2020.04.018 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Specht H & Slavov N Transformative Opportunities for Single-Cell Proteomics. J Proteome Res 17, 2565–2571, doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00257 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Specht H et al. Single-cell proteomic and transcriptomic analysis of macrophage heterogeneity using SCoPE2. Genome Biology 22, 50, doi: 10.1186/s13059-021-02267-5 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alfaro JA et al. The emerging landscape of single-molecule protein sequencing technologies. Nature Methods 18, 604–617, doi: 10.1038/s41592-021-01143-1 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao Y et al. Single-molecule spectroscopy of amino acids and peptides by recognition tunnelling. Nature Nanotechnology 9, 466–473, doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.54 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy E, Dong Z, Tennant C & Timp G Reading the primary structure of a protein with 0.07 nm3 resolution using a subnanometre-diameter pore. Nature Nanotechnology 11, 968–976, doi: 10.1038/nnano.2016.120 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swaminathan J et al. Highly parallel single-molecule identification of proteins in zeptomole-scale mixtures. Nature Biotechnology 36, 1076–1082, doi: 10.1038/nbt.4278 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Ginkel J et al. Single-molecule peptide fingerprinting. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, 3338–3343, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707207115 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Restrepo-Pérez L, Joo C & Dekker C Paving the way to single-molecule protein sequencing. Nature Nanotechnology 13, 786–796, doi: 10.1038/s41565-018-0236-6 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stefureac R, Long Y.-t., Kraatz H-B, Howard P & Lee JS Transport of α-Helical Peptides through α-Hemolysin and Aerolysin Pores. Biochemistry 45, 9172–9179, doi: 10.1021/bi0604835 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Movileanu L Squeezing a single polypeptide through a nanopore. Soft Matter 4, 925–931, doi: 10.1039/B719850G (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez-Larrea D & Bayley H Multistep protein unfolding during nanopore translocation. Nat Nanotechnol 8, 288–295, doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.22 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosen CB, Bayley H & Rodriguez-Larrea D Free-energy landscapes of membrane co-translocational protein unfolding. Commun Biol 3, 160, doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-0841-4 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Payet L et al. Thermal unfolding of proteins probed at the single molecule level using nanopores. Anal Chem 84, 4071–4076, doi: 10.1021/ac300129e (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soni N, Freundlich N, Ohayon S, Huttner D & Meller A Single-File Translocation Dynamics of SDS-Denatured, Whole Proteins through Sub-5 nm Solid-State Nanopores. ACS Nano 16, 11405–11414, doi: 10.1021/acsnano.2c05391 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oukhaled G et al. Unfolding of Proteins and Long Transient Conformations Detected by Single Nanopore Recording. Physical Review Letters 98, 158101, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.158101 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pastoriza-Gallego M et al. Dynamics of unfolded protein transport through an aerolysin pore. J Am Chem Soc 133, 2923–2931, doi: 10.1021/ja1073245 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merstorf C et al. Wild Type, Mutant Protein Unfolding and Phase Transition Detected by Single-Nanopore Recording. ACS Chemical Biology 7, 652–658, doi: 10.1021/cb2004737 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pastoriza-Gallego M et al. Evidence of Unfolded Protein Translocation through a Protein Nanopore. ACS Nano 8, 11350–11360, doi: 10.1021/nn5042398 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cressiot B et al. Protein Transport through a Narrow Solid-State Nanopore at High Voltage: Experiments and Theory. ACS Nano 6, 6236–6243, doi: 10.1021/nn301672g (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keyser UF et al. Direct force measurements on DNA in a solid-state nanopore. Nature Physics 2, 473–477, doi: 10.1038/nphys344 (2006). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nivala J, Marks DB & Akeson M Unfoldase-mediated protein translocation through an alpha-hemolysin nanopore. Nat Biotechnol 31, 247–250, doi: 10.1038/nbt.2503 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nivala J, Mulroney L, Li G, Schreiber J & Akeson M Discrimination among Protein Variants Using an Unfoldase-Coupled Nanopore. ACS Nano 8, 12365–12375, doi: 10.1021/nn5049987 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan S et al. Single Molecule Ratcheting Motion of Peptides in a Mycobacterium smegmatis Porin A (MspA) Nanopore. Nano Letters, doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c02371 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Z et al. Controlled movement of ssDNA conjugated peptide through Mycobacterium smegmatis porin A (MspA) nanopore by a helicase motor for peptide sequencing application. Chemical Science 12, 15750–15756, doi: 10.1039/D1SC04342K (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brinkerhoff H, Kang Albert SW, Liu J, Aksimentiev A & Dekker C Multiple rereads of single proteins at single–amino acid resolution using nanopores. Science 0, eabl4381, doi: 10.1126/science.abl4381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang X, Alibakhshi MA & Wanunu M One-Pot Species Release and Nanopore Detection in a Voltage-Stable Lipid Bilayer Platform. Nano Letters 19, 9145–9153, doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b04446 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu L et al. Stable polymer bilayers for protein channel recordings at high guanidinium chloride concentrations. Biophysical Journal 120, 1537–1541, doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2021.02.019 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haynes WM CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. (CRC Press, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perkins SJ Protein volumes and hydration effects. European Journal of Biochemistry 157, 169–180, doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09653.x (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu GP, Topping TB, Cover WH & Randall LL Retardation of folding as a possible means of suppression of a mutation in the leader sequence of an exported protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry 263, 14790–14793, doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)68107-4 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheshadri S, Lingaraju GM & Varadarajan R Denaturant mediated unfolding of both native and molten globule states of maltose binding protein are accompanied by large deltaCp's. Protein Sci 8, 1689–1695, doi: 10.1110/ps.8.8.1689 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakane J, Akeson M & Marziali A Evaluation of nanopores as candidates for electronic analyte detection. ELECTROPHORESIS 23, 2592–2601, doi: (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meller A, Nivon L & Branton D Voltage-Driven DNA Translocations through a Nanopore. Physical Review Letters 86, 3435–3438, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3435 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meller A & Branton D Single molecule measurements of DNA transport through a nanopore. ELECTROPHORESIS 23, 2583–2591, doi: (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hornblower B et al. Single-molecule analysis of DNA-protein complexes using nanopores. Nature Methods 4, 315–317, doi: 10.1038/nmeth1021 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Henrickson SE, Misakian M, Robertson B & Kasianowicz JJ Driven DNA Transport into an Asymmetric Nanometer-Scale Pore. Physical Review Letters 85, 3057–3060, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.3057 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mathé J, Aksimentiev A, Nelson DR, Schulten K & Meller A Orientation discrimination of single-stranded DNA inside the α-hemolysin membrane channel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102, 12377–12382, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502947102 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang G et al. Solid-state synthesis and mechanical unfolding of polymers of T4 lysozyme. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 97, 139, doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.139 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aksimentiev A & Schulten K Imaging α-Hemolysin with Molecular Dynamics: Ionic Conductance, Osmotic Permeability, and the Electrostatic Potential Map. Biophysical Journal 88, 3745–3761, doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.058727 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cuturi M & Blondel M in Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning Vol. 70 (eds Precup Doina & Teh Yee Whye) 894–903 (PMLR, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Larkin J, Henley RY, Muthukumar M, Rosenstein Jacob K. & Wanunu M High-Bandwidth Protein Analysis Using Solid-State Nanopores. Biophysical Journal 106, 696–704, doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.12.025 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ling DY & Ling XS On the distribution of DNA translocation times in solid-state nanopores: an analysis using Schrödinger’s first-passage-time theory. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 25, 375102, doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/25/37/375102 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li J & Talaga DS The distribution of DNA translocation times in solid-state nanopores. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 22, 454129, doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/22/45/454129 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Talaga DS & Li J Single-Molecule Protein Unfolding in Solid State Nanopores. Journal of the American Chemical Society 131, 9287–9297, doi: 10.1021/ja901088b (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pavlenok M, Yu L, Herrmann D, Wanunu M & Niederweis M Control of subunit stoichiometry in single-chain MspA nanopores. Biophysical Journal, doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2022.01.022 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ouldali H et al. Electrical recognition of the twenty proteinogenic amino acids using an aerolysin nanopore. Nat Biotechnol 38, 176–181, doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0345-2 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Versloot RCA, Straathof SAP, Stouwie G, Tadema MJ & Maglia G β-Barrel Nanopores with an Acidic–Aromatic Sensing Region Identify Proteinogenic Peptides at Low pH. ACS Nano, doi: 10.1021/acsnano.1c11455 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Versloot RCA et al. Quantification of Protein Glycosylation Using Nanopores. Nano Letters 22, 5357–5364, doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c01338 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang G et al. PlyAB Nanopores Detect Single Amino Acid Differences in Folded Haemoglobin from Blood**. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 61, e202206227, doi: 10.1002/anie.202206227 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Noakes MT et al. Increasing the accuracy of nanopore DNA sequencing using a time-varying cross membrane voltage. Nature Biotechnology 37, 651–656, doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0096-0 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Phillips JC et al. Scalable molecular dynamics on CPU and GPU architectures with NAMD. The Journal of Chemical Physics 153, 044130, doi: 10.1063/5.0014475 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Klauda JB et al. Update of the CHARMM All-Atom Additive Force Field for Lipids: Validation on Six Lipid Types. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 114, 7830–7843, doi: 10.1021/jp101759q (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yoo J & Aksimentiev A New tricks for old dogs: improving the accuracy of biomolecular force fields by pair-specific corrections to non-bonded interactions. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 20, 8432–8449, doi: 10.1039/C7CP08185E (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miyamoto S & Kollman PA Settle: An analytical version of the SHAKE and RATTLE algorithm for rigid water models. Journal of Computational Chemistry 13, 952–962, doi: 10.1002/jcc.540130805 (1992). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Andersen HC Rattle: A “velocity” version of the shake algorithm for molecular dynamics calculations. Journal of Computational Physics 52, 24–34, doi: 10.1016/0021-9991(83)90014-1 (1983). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Darden T, York D & Pedersen L Particle mesh Ewald: An N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. The Journal of Chemical Physics 98, 10089–10092, doi: 10.1063/1.464397 (1993). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jo S, Kim T, Iyer VG & Im W CHARMM-GUI: A web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. Journal of Computational Chemistry 29, 1859–1865, doi: 10.1002/jcc.20945 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Song L et al. Structure of staphylococcal α-hemolysin, a heptameric transmembrane pore. Science 274, 1859–1865 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW & Klein ML Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. The Journal of chemical physics 79, 926–935 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martyna GJ, Tobias DJ & Klein ML Constant pressure molecular dynamics algorithms. The Journal of Chemical Physics 101, 4177–4189, doi: 10.1063/1.467468 (1994). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Duan X & Quiocho FA Structural Evidence for a Dominant Role of Nonpolar Interactions in the Binding of a Transport/Chemosensory Receptor to Its Highly Polar Ligands. Biochemistry 41, 706–712, doi: 10.1021/bi015784n (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Humphrey W, Dalke A & Schulten K VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. Journal of Molecular Graphics 14, 33–38, doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li H, Robertson AD & Jensen JH Very fast empirical prediction and rationalization of protein pKa values. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 61, 704–721, doi: 10.1002/prot.20660 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tavenard R et al. Tslearn, A Machine Learning Toolkit for Time Series Data. J. Mach. Learn. Res 21, 1–6 (2020).34305477 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pedregosa F et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. the Journal of machine Learning research 12, 2825–2830 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schreiber J & Karplus K Analysis of nanopore data using hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics 31, 1897–1903, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv046 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Muthukumar M Polymer translocation through a hole. The Journal of Chemical Physics 111, 10371–10374, doi: 10.1063/1.480386 (1999). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ammenti A, Cecconi F, Marini Bettolo Marconi U & Vulpiani A A Statistical Model for Translocation of Structured Polypeptide Chains through Nanopores. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 113, 10348–10356, doi: 10.1021/jp900947f (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this manuscript are available for download at https://figshare.com/s/5cd39ee415c62a316a6f.

All data parsing (excluding DTW and GBC) were performed using the Pyth-ion package (https://github.com/wanunulab/Pyth-Ion) and figures were generated using Igor. For analysis, the raw 100 kHz nanopore current data was further low-pass filtered to 10 kHz using the low-pass filter function in Pyth-ion. DTW and GBC analyses were conducted via python scripts written and documented in Jupyter Notebooks, tslearn (v0.5.2)75, SciKit-Learn (v1.0.2)76, and a modified version of the PyPore77 nanopore data analysis library. The Jupyter notebook and associated files are available on GitHub (https://github.com/wanunulab/protein-gd). A detailed description of the DTW and GBC analyses is provided in SI Section 6.