Abstract

Objective:

Rumination is a risk factor for the development of internalizing psychopathology that often emerges during adolescence. The goal of the present study was to test a mindfulness mobile app intervention designed to reduce rumination.

Method:

Ruminative adolescents (N = 152; 59 % girls, 18% racial/ethnic minority, Mage = 13.72, SD = .89) were randomly assigned to use a mobile app 3 times per day for 3 weeks that delivered brief mindfulness exercises or a mood monitoring-only control. Participants reported on rumination, depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms at baseline, post-intervention and at 3 follow-up timepoints: 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months post-intervention. Parents reported on internalizing symptoms.

Results:

There was a significant Time × Condition effect at post-intervention for rumination, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms, such that participants in the mindfulness intervention showed improvements relative to those in the control condition. The effect for rumination lasted through the 6-week follow-up period; however, group differences were generally not observed throughout the follow-up period, which may indicate that continued practice is needed for gains to be maintained.

Conclusions:

This intervention may have the potential to prevent the development of psychopathology and should be tested in a longitudinal study assessing affective disorder onset, especially in populations with limited access to conventional, in person mental health care.

Keywords: adolescents, rumination, mindfulness, mobile app, internalizing symptoms

Rumination, which involves passively and repetitively focusing on one’s negative emotions and brooding about their meaning and consequences (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991), is a transdiagnostic risk factor involved in the development of a wide range of psychopathology, especially depression and anxiety (for reviews see Aldao et al., 2010; Nolen-Hoeksema & Watkins, 2011; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008; Watkins & Roberts, 2020). The tendency to ruminate develops throughout childhood and is thought to consolidate into a trait-like response style by adolescence (Shaw et al., 2019), a time when depression and anxiety begin to increase (e.g., Merikangas et al., 2010). A meta-analysis showed that rumination is associated with depressive symptoms, both concurrently and prospectively, among adolescents (Rood et al., 2009), and rumination prospectively predicts diagnoses of depression in adolescents (Abela & Hankin, 2011). Similarly, rumination concurrently and prospectively predicts anxiety symptoms in adolescents (e.g., McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011; Muris et al., 2004). Thus, rumination’s transdiagnostic risk status makes it an important target for preventive interventions, as intervening with individuals who ruminate may prevent the development of psychopathology.

Mindfulness offers an alternative rumination, by providing a way to attend to negative emotions without getting caught up in them. We designed a brief mindfulness mobile app intervention (i.e., the CARE app) appropriate for adolescents to target rumination and symptoms of psychopathology. We previously reported that this intervention was successful in targeting rumination in adolescents (Hilt & Swords, 2021). In that study, ruminative adolescents were asked to use the mobile app three times per day for three weeks and were followed for 12 weeks after the intervention period. The app involved both mood monitoring (through responses to ecological momentary assessment prompts) and brief mindfulness exercises. There were significant decreases in rumination and internalizing symptoms post-intervention with medium to large effects sizes (e.g., ηp2 = .06- .33), most of which lasted throughout the follow-up period. Furthermore, the study showed that the intervention was acceptable for adolescents (e.g., 77.4% of adolescents and 81.7% of parents found it acceptable). The primary limitation of the study was that it used a pre/post, within-subjects design (no control group) and was unable to control for threats to internal validity, such as the passage of time, regression to the mean, and the effect of repeated assessments. Additionally, because the mobile app utilized both mood monitoring and mindfulness exercises, it was unclear how much the outcomes may have been due to the mood monitoring aspect of the intervention. Accordingly, the goal of the present study was to test the mobile app intervention for ruminative adolescents utilizing a randomized, controlled design where a mood-monitoring-only version of the app was compared to the mood-monitoring-plus-mindfulness version from the previous trial.

Targeting Rumination with Mindfulness

Many have argued that the nonjudgmental awareness that is cultivated through mindfulness allows individuals to experience negative emotions in a different way. That is, rather than pushing that negative emotion away (i.e., experiential avoidance) or getting overly engaged with it (e.g., rumination), mindfulness allows people to experience their negative emotions and let them go (e.g., Chambers et al., 2009; Williams & Kuyken, 2012). Below, we review research on the relationship between mindfulness and rumination that informed the development of the intervention used in the present study.

Rumination and Mindfulness Have an Inverse Relationship

An important negative association between trait mindfulness (i.e., the tendency for one to focus attention on the present moment in a nonjudgmental manner) and trait rumination (i.e., the tendency to repetitively and passively focus on one’s negative emotions) exists. For example, in a study of college students, trait mindfulness was negatively correlated with levels of uncontrollable rumination (Raes & Williams, 2010). Further, other studies with adults have shown that global measures of trait mindfulness are negatively associated with rumination (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Keune et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2008). Studies that have examined specific aspects of mindfulness suggest that the nonjudgment facet, in particular, may be uniquely inversely associated with rumination (Petrocchi & Ottaviani, 2016; Thompson et al., 2019). We have also found that the nonjudgment facet of mindfulness (which focuses on taking a neutral and non-evaluative stance toward inner thoughts and feelings) predicts rumination concurrently and prospectively in both college students and adolescents (Swords & Hilt, 2021). This negative relationship may suggest that rumination and mindfulness are, in some ways, antithetical. While rumination tends to focus on the past and involve high levels of judgment about the self (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008), mindfulness focuses on the present and involves a more neutral stance towards the self. Of course, given the debate within the field about the validity of trait mindfulness measures (e.g., Karl & Fischer, 2022), it is critical to look beyond correlational studies of trait mindfulness and rumination. Importantly, an experimental study with adolescents showed that when participants experienced negative emotions about the self, engagement in rumination amplified them while engagement in mindfulness decreased them (e.g., Hilt & Pollak, 2012). Thus, training in mindfulness may offer an optimal way to reduce rumination by providing a different way of responding to negative thoughts.

Mindfulness Interventions Reduce Rumination

Mindfulness meditation (i.e., the practice of focusing one’s attention on the present moment, nonjudgmentally; Kabat-Zinn, 2003) has shown promise in reducing rumination. For example, studies of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (Kabat-Zinn, 2003) in healthy adults (e.g., Deyo et al., 2009; Shapiro et al., 2007) and stressed college students (e.g., Jain et al., 2007) have demonstrated a decrease in rumination. Similarly, studies of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (Segal et al., 2002) for depressed adults have shown decreases in rumination (Perestelo-Perez et al., 2017). Importantly, these studies have been conducted using rather intensive interventions (i.e., lasting 4–8 weeks, with weekly in-person sessions and daily home practice) and have only involved adults.

Brief mindfulness interventions also exist, but they have not generally been tested for their ability to reduce rumination. There are many mindfulness apps available in the marketplace, and the few that have been subject to empirical testing have demonstrated reductions in stress, depression, and anxiety (e.g., Howells et al., 2016; Cavanagh et al., 2013; Delgado et al., 2010; Flett et al., 2019; van Emmerik et al., 2018). Although several available mindfulness apps have been deemed appropriate for children or adolescents, they have generally not been subject to empirical testing (Nunes et al., 2020).

Laboratory studies have demonstrated the ability of brief mindfulness interventions to reduce state rumination in college students (Villa & Hilt, 2014) and adolescents (Hilt & Pollak, 2012). In both studies, participants were induced to ruminate (either via a standard rumination induction or social-evaluative stressor) and then engaged in an 8-minute exercise to which they were randomly assigned. A brief mindfulness exercise reduced rumination relative to other brief exercises in both studies, suggesting that mindfulness may be particularly helpful in targeting rumination, in both adults and adolescents.

Development of the CARE App

These findings led us to develop a brief mindfulness mobile intervention, the CARE app, to target rumination in adolescents. After pilot testing to help assess feasibility and determine an optimal length for the intervention, we conducted an open-label trial and found that the app significantly reduced trait rumination along with symptoms of depression and anxiety among a group of adolescents selected for at least moderate levels of rumination who were asked to use the app three times per day for three weeks (Hilt & Swords, 2021). In designing a randomized, controlled trial, we wanted to develop a comparison condition that was identical to the mindfulness intervention, but without mindfulness exercises. Thus, participants in the control condition would use the app to respond to mood prompts three times per day, just like those in the intervention condition, but they would never receive a mindfulness exercise to complete. Research on mobile mood monitoring shows that it reduces depressive symptoms among youth via increased emotional self-awareness, but it does not impact rumination (Kauer et al., 2012). Given the favorable outcomes associated with mobile mood monitoring in adolescents (Dubad et al., 2018), it appears the control condition would function as not only an assessment-only control but also as an active intervention.

The Present Study

The present study sought to answer the question of whether the CARE app, which involves both mood monitoring and mindfulness, would uniquely reduce rumination compared to a mood-monitoring only version of the app. We hypothesized that ruminative adolescents assigned to the mindfulness mobile app intervention three times per day for three weeks would show reductions in trait rumination compared to adolescents assigned to a mood monitoring-only control. We also expected that the reduction in rumination resulting from the intervention would mediate decreases in internalizing psychopathology during the follow-up period.

Method

Procedure

The present study was approved by the Lawrence University IRB. This study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and adhered to Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Participants were recruited from 2019–2020 from a mid-sized Midwestern city in the United States through mailed letters to parents and guardians of 6–9th grade students at public schools. Letters described a research study investigating how a mobile app may help adolescents cope with their emotions. In addition to recruitment letters, participants were also recruited through word-of-mouth, study posters in public spaces (e.g., gyms, community centers, and grocery stores), and online advertisements that used language identical to the letter advertisements. Interested families emailed to schedule a time to determine eligibility by phone. Eligible and interested families were scheduled for a 45-minute, in-person visit to our laboratory. Due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, 23 participants completed the visit virtually via videoconference. There were no differences in baseline measures between those enrolled virtually and those enrolled in person (ts = −.11 – 09; ps = .912 - .931).

During the visit, study personnel explained the details of the study and obtained informed consent and assent. After, adolescents and parents completed a series of baseline questionnaires through an online survey. Participants downloaded the app onto their device, or one borrowed from our lab (n = 19) and entered their unique ID number and a specialized code into the app that granted access to the version of the app they were randomly assigned to (using simple randomization) prior to completion of baseline questionnaires. Next, adolescents entered their sleep and wake time to calibrate notifications from the app that would not interrupt their sleep.

Participants were given a tour of the app to learn how to use it. After, all participants used the app once to practice. Adolescents in the mindfulness condition completed an example mindfulness exercise if they had not received one through the app and received brief psychoeducation about mindfulness from a script read to them by a research assistant. Participants were compensated for the visit ($15 for adolescent and $15 for parent).

All participants received notifications to use the app three times a day (i.e., once in the morning, once after school and once before bed). While participants were encouraged to use the app following the notification, they were permitted to use the app later if they missed a notification. Participants received $25 for completing the intervention and post-intervention questionnaire ($20 for adolescent and $5 for parent). To incentivize app use, all participants could also earn a weekly bonus of $5 for using the app twenty-one times or more during each week of the three-week intervention period (for up to $15 bonus). Study personnel emailed parents each week to let them know whether their child had earned the weekly bonus, and participants could reference a counter on the app to keep track themselves. After the three-week intervention period, participants were no longer prompted or incentivized to use the CARE app but were able to continue using it if they liked. Participants were also compensated for each follow-up questionnaire (6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months post-intervention) they completed ($10 for adolescent and $5 for parent).

Mood Monitoring Control Condition

Participants randomized to the control condition only completed mood monitoring questions. Each time adolescents used the app, they were prompted to rate how they were feeling (i.e., sad, anxious, happy, and calm) and whether they were ruminating (i.e., focusing on emotions or focusing on problems) in that moment. Using a slider, participants responded to each prompt on a 0 (not at all) to 100 (extremely) scale. Participants also reported state mindfulness and where they were taking the survey from (i.e., school, work, car, home).

Mindfulness Condition

In addition to the questions adolescents in the control condition received, participants in the mindfulness condition also received mindfulness exercises some of the time. To prevent adolescents from learning which responses would prompt a mindfulness exercise, adolescents had a 2/3 chance of receiving an exercise each time they used the app. To increase the chance they would receive an exercise when they most needed it, higher levels of state negative affect (i.e., sadness or anxiety ratings) increased the chances that an adolescent received a mindfulness exercise to 85%. If a mindfulness exercise was assigned, adolescents were prompted to report how much time they had available to practice from the following options: ~1 minute, ~5 minutes, or ~10 minutes. Participants were randomly assigned to an exercise that fit within the specified window of time they had available. Following the completion of a mindfulness exercise, participants again completed the same mood monitoring questions. All mindfulness exercises were selected from those in the public domain that were freely available and were tested through pilot studies to determine suitability for adolescents. The exercises primarily involved anchoring attention to the present moment through a focus on specific objects (e.g., breath, sounds, physical sensations). One-minute exercises were presented with written instructions on the screen along with a one-minute timer, and longer exercises (i.e., 3–12 minutes) were presented with recorded audio and involved a variety of voices.

Participants

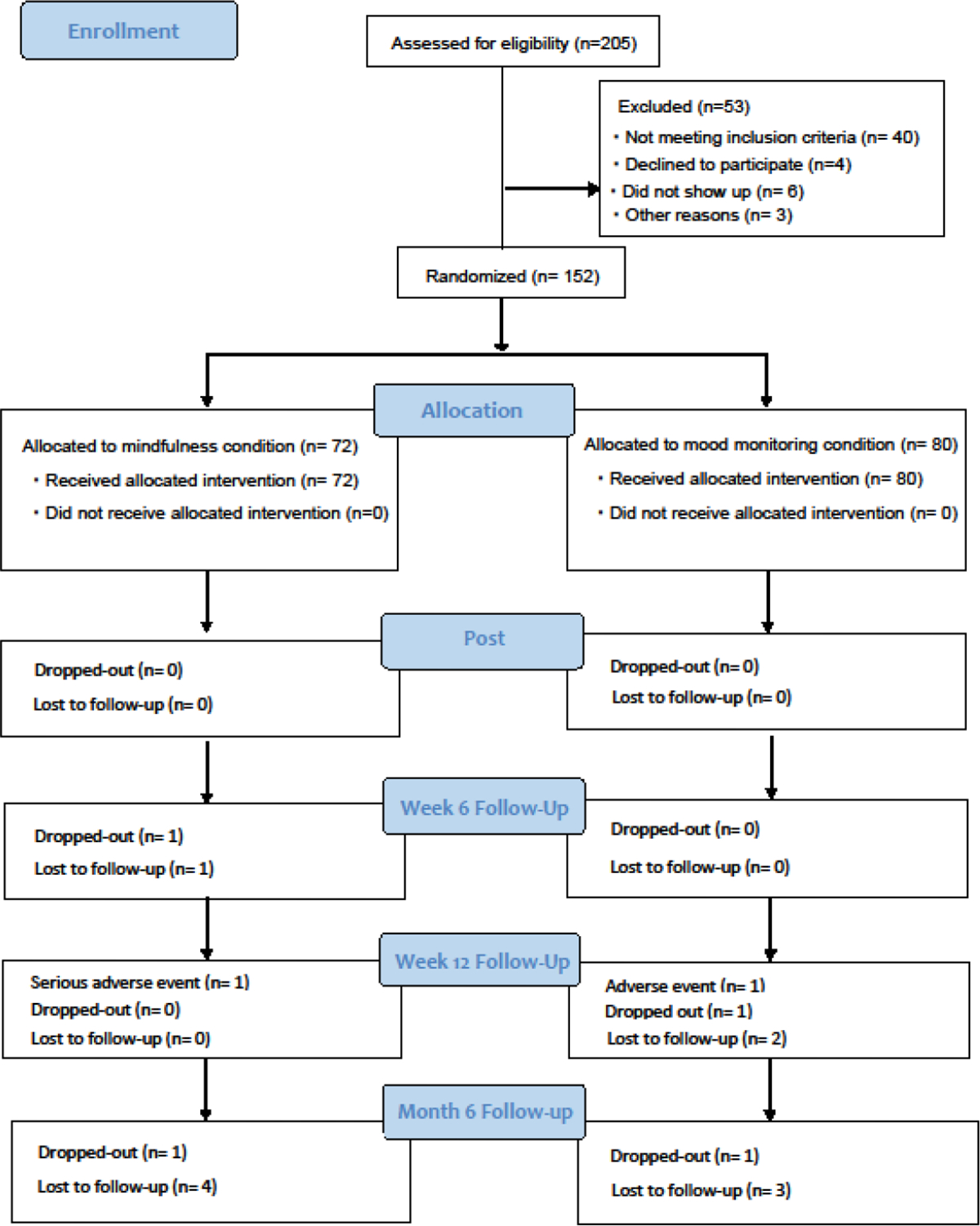

Participants were 152 adolescents (M age = 13.71 years, SD=.89) recruited from a mid-sized midwestern city in the United States. Inclusion criteria included being between the ages of 12–15 years old and reporting moderate-to-high levels of rumination during an initial phone screen. The phone screen involved two questions from the Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire (CRSQ; Abela et al., 2002) that are also included on the gold-standard brooding subscale from the Ruminative Response Scale (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) used for assessing rumination in adults. Participants were eligible if their responses indicated they ruminate “sometimes,” “often,” or “always” on average. Forty participants did not meet this inclusion criterion. Exclusion criteria included serious physical or cognitive disability that prevented the adolescent from using a mobile device, inadequate English proficiency to complete outcome measures (assessed during phone screen), or imminent suicide concerns. No participants were excluded based on these criteria. See Figure 1 for CONSORT diagram of participant flow.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram

Parents reported on sex, race, and ethnicity; participants were 58.55% female, 41.45.% male; 82.24% White, 10.53% Multiracial, 3.29% Black or African American, 1.97% Asian or Asian American, 1.32% other, and .66% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander; 89.47% non-Hispanic and 10.53% Hispanic. Prior research on adolescents has found that rumination is somewhat more common among girls compared to boys (e.g., Hilt et al., 2010) and does not vary across racial/ethnic background (e.g., Hankin, 2008), suggesting our sample is likely to be representative of adolescents at-risk for rumination. Parents also reported on income: range = $10,000–15,000 to more than $300,000; median = $90,000–100,000; 9.21% reported being recipients of a government-assisted food program. For full participant demographic and baseline clinical information, see Table 1. Children’s Depression Inventory scores showed that 18.42% of the sample (n = 28) scored a 20 or above, which is the recommended cut-off score for a non-clinical sample (Kovacs, 1992). This can be compared to recent epidemiological data suggesting past-year prevalence of a major depressive episode to be 11.2% for 12–13 year-olds and 18.2% for 14–15 year-olds (National Institute of Mental Health, n.d.).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Baseline Scores

| Control (n = 80) | Mindfulness (n = 72) | t | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| n | % | Mean (SD) | n | % | Mean | df = 150 | |

|

| |||||||

| Age | 13.66 (.86) | 13.78 (.93) | |||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 45 | 56.25% | 44 | 61.11% | |||

| Male | 35 | 43.75% | 28 | 38.89% | |||

| Race | |||||||

| White | 70 | 87.50% | 55 | 76.39% | |||

| Black; African American | 2 | 2.50 % | 3 | 4.17% | |||

| Asian; Asian American | 2 | 2.50% | 1 | 1.39% | |||

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 1.39% | |||

| Native American | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Other | 1 | 1.25% | 1 | 1.39% | |||

| Multi-racial | 5 | 6.25% | 11 | 15.28% | |||

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 73 | 91.25% | 63 | 87.50% | |||

| Hispanic | 7 | 8.75% | 9 | 12.50% | |||

| Baseline Scores | |||||||

| Rumination | 15.68 (8.16) | 17.81 (9.73) | 1.47 | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms | 12.04 (7.72) | 13.40 (8.77) | 1.02 | ||||

| Anxiety Symptoms | 50.84 (17.35) | 53.47 (16.51) | .96 | ||||

| Parent-Reported Internalizing | 3.88 (2.45) | 3.64 (2.38) | .60 | ||||

Measures

Rumination

We assessed trait-level rumination with the Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire (CRSQ; Abela et al., 2002). The CRSQ is a 25-item self-report questionnaire modeled after the Response Styles Questionnaire (RSQ; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991), for adults. On a scale from 0 (almost never) to 3 (almost always), respondents rank how often they respond to feelings of sadness as described by the item. The rumination subscale comprises 13 items (e.g., “Think about a recent situation, wishing it had gone better.”). Scores on each subscale are totaled, with higher scores indicating greater frequency and severity of rumination. Past research with the CRSQ rumination subscale in adolescent samples has shown high internal consistency, test-retest reliability and validity in predicting depressive symptoms (e.g., Hilt et al., 2010). In the present study, we modified the instructions of the CRSQ to ask how adolescents respond to sadness or distress (rather than just sadness per the original measure) to align with current conceptualization of rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008; Shaw et al., 2019) and the measure’s use in other, more recent studies (e.g., Hilt & Swords, 2021). The reliability of the CRSQ rumination subscale at each time point in the present study was high: α =.92, α =.92, α = .91., α =.92, α =.93.

Internalizing Symptoms

Depressive Symptoms.

We assessed depression using the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992), a 27-item measure adapted from the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1996) for adults. Like the BDI, respondents self-report on how they have been thinking and feeling during the past two weeks. Items on the CDI capture five dimensions of depression (anhedonia, ineffectiveness, interpersonal difficulty, negative mood, and negative self-esteem) and are scored on a scale from 0–2. A total score is calculated by summing items, with higher CDI scores indicating greater severity of depression. Past research demonstrates that the CDI is a reliable and valid measure used to assess the frequency and severity of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents between the ages of seven to 17 (Craighead et al.,1995; Klein, et al., 2005). In this sample, the reliability for the CDI at each time point was high: α = .90, α=.92, α =.91, α=.92, α=.92.

Anxiety Symptoms.

We assessed anxiety using the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March et al., 1997). The MASC contains 39 items that assess anxiety across five dimensions: physical symptoms (e.g., restlessness), harm avoidance, social (e.g., fear of humiliation and rejection), and separation anxiety. On a scale from 0 (never true) to 3 (often true about me), respondents identify how often and to what extent they experience the symptoms of anxiety described by each item. Past research suggests the MASC has good-to-excellent internal reliability (March et al., 1997; Baldwin & Dadds, 2007) and demonstrates satisfactory-to-excellent test-retest reliability among adolescents (March et al., 1997; March et al., 1999). In this sample, the reliability for the MASC total score at each time point was high: α = .90, α= .92, α= .92, α= .93, α= .93.

Parent-Reported Internalizing Symptoms.

Parents reported symptoms of psychopathology using the Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC; Jellinek et al., 1988). The PSC is a 35-item measure for parents to report on frequency of symptoms with three subscales: internalizing, externalizing, and attention. We used the five-item internalizing subscale to measure observable symptoms of internalizing (e.g., “Feels sad, unhappy”) as reported by parents. In this sample, the reliability for the internalizing subscale at each time point was as follows: α = .83, α= .77, α= .82, α= .81, α= .79.

Data Analytic Plan

Data were analyzed using R (vers. 4.1.0) and SPSS, version 28.0 (IBM Corp). Sample size was determined via power analysis for the primary RCT aim focused on testing between-group differences in reduction of rumination. Pilot work revealed a large difference on change in trait rumination (d = .88). The current sample size (n = 152) would provide excellent power (>.99; assuming alpha = 0.05) to detect this effect. With an alpha = .05 and power = 0.80, a sample size of 152 could detect a small-to-medium (d = .46) effect size for between-group differences in rumination change.

General Analytic Strategies

Baseline equivalence was examined on all outcome measures using t-tests. We also compared those who completed the study to those who dropped out or were lost to follow up on demographic and baseline characteristics. Compliance and intervention dose were assessed with time-stamped electronic records generated through the app.

Hypothesis Testing

We used multilevel models (via lme4and lmerTest packages in R; Bates et al., 2014; Kuznetsova et al., 2017) to test whether the mindfulness intervention condition significantly reduced rumination and psychopathology symptoms (i.e., depression, anxiety, and parent-reported internalizing symptoms) relative to the mood monitoring only control condition from baseline to post-treatment (via testing a Group × Time interaction). Time was centered to represent estimated post-treatment rumination/symptom scores. We specified a random intercept in the latter models (random intercepts and slopes cannot both be included given that these models only include two timepoints). Next, to examine whether any effects persisted during the follow-up period, we tested Group × Time interactions, with the time variable now also incorporating each follow-up timepoint (i.e., baseline, post-treatment, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months post-intervention). Time was centered to represent estimated rumination/symptom scores at the final follow-up. Both random intercepts and slopes were specified in the latter models. We included child sex in these analyses given previous research on sex differences in rumination and internalizing symptoms (e.g., Hilt et al., 2010). Standardized effect sizes Group × Time interactions were estimated using the dGMA-RAW (β11(time)/SDRAW) formula recommended by Feingold (2009) for multilevel models (for simplicity dGMA-RAW is simply referred to as d below). All available data were used in these multilevel models, including from participants who dropped out (i.e., intent-to-treat analyses). See Supplemental materials for multilevel model equations.

Causal mediation was tested using the PROCESS macro (v. 3.5, Model 4; Hayes, 2018) for SPSS (IBM Corp.) which relies on bootstrapping with 5000 resamples to generate bias corrected confidence intervals. In these models, condition (independent variable) was examined as a predictor of symptoms (dependent variable) during the first follow-up period, and rumination at post-intervention was specified as the mediator, with baseline symptoms, baseline rumination, and sex entered as covariates. We also specified the models in reverse to clarify directionality (i.e., post-intervention symptom as mediator of the effect of condition on rumination during follow-up).

For all significant effects, we report on clinical significance using the Jacobson-Truax (1991) method. We chose to calculate the reliable change index for ease of comparison across outcomes measures, since there is no clinical cut-off score for rumination.

Results

Table 1 shows baseline clinical and demographic data for each condition. There were no significant differences between condition on any outcome variables at baseline based on t-tests (ps = .144-.548). There were also no significant differences on any outcome variables at baseline between those who were retained throughout the study (n = 136) and those who dropped out or were lost to follow up (n = 16; ps = .112-.629). There were no differences between the retained and attrited groups on demographic variables, except that the attrited group had a larger percentage of government-assisted food program recipients (χ2 = 5.33, p = .02).

There was equal compliance in app use across conditions. On average, participants used the app 2–3 times per day. Participants in the mindfulness intervention group used the app 51.72 times (SD = 16.37) during the three-week intervention period compared to 54.26 times (SD = 15.26) in the mood monitoring only control group, t(150) = −.99, p = .326. Similarly, when app use was optional during the follow-up period, there was no significant difference between app use in the mindfulness group (M = 40.24, SD = 78.98) versus the control group (M = 39.74, SD =.70.22), t(150) = .04, p = .967.

Hypothesis Testing

Changes in Rumination and Internalizing Symptoms

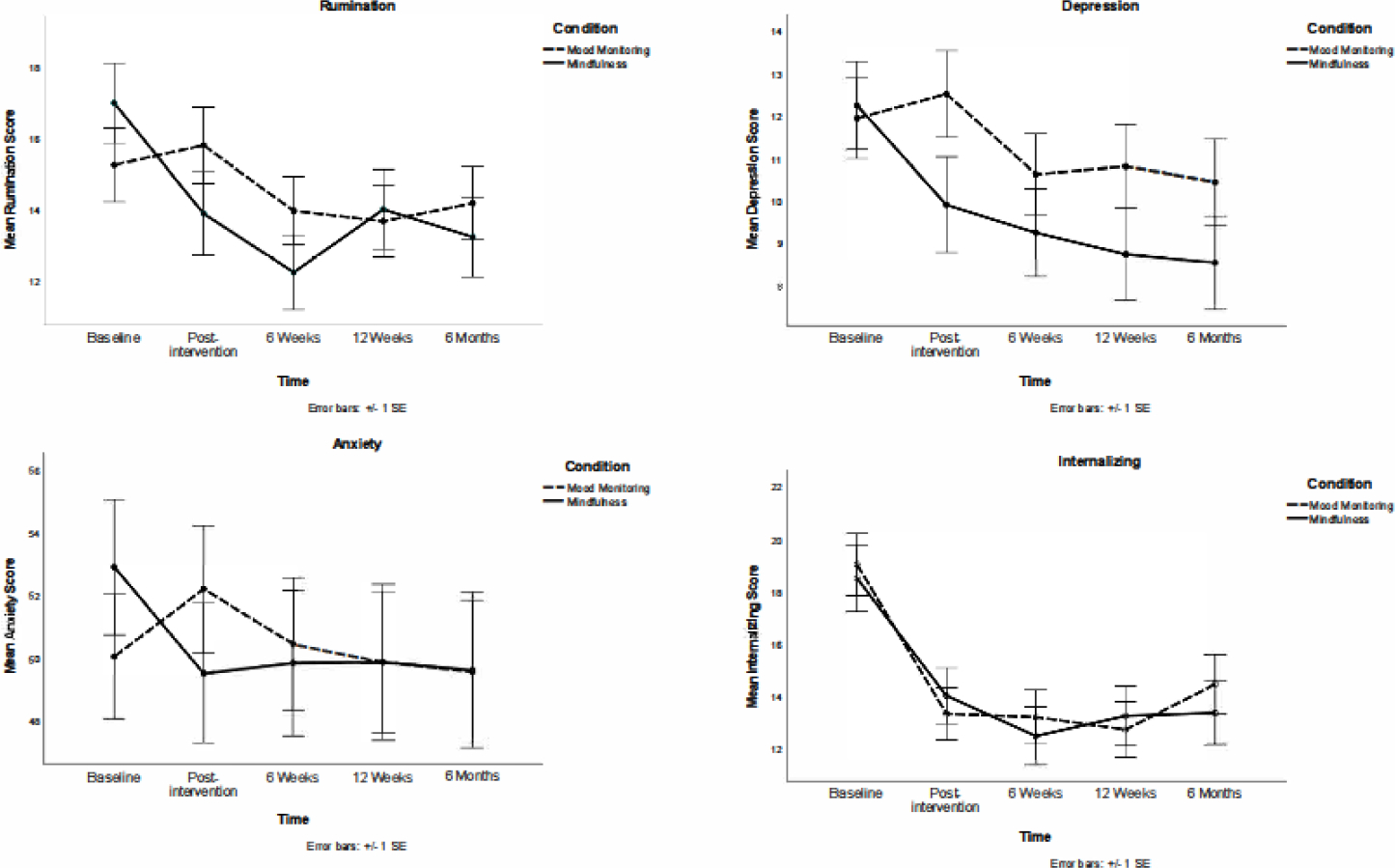

Our first hypothesis was that ruminative adolescents assigned to the mindfulness mobile app intervention would show reductions in trait rumination compared to adolescents assigned to a mood monitoring-only control. Results from the multilevel models testing group differences in changes in rumination and symptoms from during treatment are presented in Table 2 (also see Fig. 2 for line graphs of observed scores). There were significant Time × Condition effects at post-intervention, indicating that the mindfulness intervention reduced rumination as hypothesized (d = .43) as well as depressive symptoms (d = .24) and anxiety symptoms (d = .25) relative to the mood-monitoring only control. Specifically, there were reductions in rumination (b = 3.20; t(69.86) = 3.53, p < .001) and depressive symptoms (b = 1.85; t(70.32) = 2.95, p = .005) in the mindfulness group but not in the mood monitoring only control group [for rumination, b = −0.69; t(78.49) = −0.88, p = .380; for depressive symptoms, b = −0.18; t(78.46) = −0.26, p = .792]. For anxiety symptoms, probing of effects separately by group revealed no significant effect for the mindfulness group (b = 2.50; t(70.59) = 1.60, p = .114) or the mood monitoring only control group (b = −1.75; t(78.16) = −1.45, p = .150).

Table 2.

Multilevel Models Testing Group Differences in Changes in Rumination and Symptoms from Baseline to Post-Treatment

| Rumination | Depressive Symptoms | Anxiety Symptoms | Parent-Reported Internalizing | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | SE | p | Estimates | SE | p | Estimates | SE | p | Estimates | SE | p |

|

| ||||||||||||

| (Intercept) | 13.50 | 1.21 | <0.001 | 9.48 | 1.18 | <0.001 | 46.99 | 2.32 | <0.001 | 2.25 | 0.32 | <0.001 |

| Child Sex [females] | 5.09 | 1.29 | <0.001 | 4.86 | 1.29 | <0.001 | 9.94 | 2.52 | <0.001 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.373 |

| Time | −0.69 | 0.82 | 0.400 | −0.17 | 0.63 | 0.784 | −1.74 | 1.34 | 0.196 | 1.45 | 0.19 | <0.001 |

| Condition [mindfulness] | −2.01 | 1.41 | 0.154 | −0.89 | 1.36 | 0.511 | −2.10 | 2.68 | 0.434 | 0.07 | 0.37 | 0.848 |

| Time * Condition | 3.89 | 1.19 | 0.001 | 2.02 | 0.92 | 0.029 | 4.25 | 1.95 | 0.030 | −0.32 | 0.28 | 0.256 |

| Marginal R2 / Conditional R2 | 0.093 / 0.674 | 0.082 / 0.790 | 0.086 / 0.758 | 0.083 / 0.728 | ||||||||

Note. Significant p-values are in bold. For categorical predictors (i.e., child sex and condition), parameter estimates are provided for each level of a given predictor relative to the reference level (i.e., reference for Condition = Control Group; Child Sex = males). For example, Child Sex [females] has a parameter estimate of 5.09 for the Rumination model which indicates that females have a mean rumination level 5.09 points higher than males. SE = Standard Error. Marginal R2 considers the variance associated with fixed effects, whereas the conditional R2 takes both the fixed and random effects into account.

Figure 2.

Observed Scores for Rumination, Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety Symptoms, and Parent-reported Internalizing Symptoms Throughout the Study

There were no significant Group × Time interactions for the multilevel models which included all follow-up timepoints (all ps >.26; see Supplemental Table 1). Exploratory analyses did reveal that the Group × Time interaction for rumination remained significant through the first follow-up timepoint (i.e., 6-weeks post-intervention) but not the subsequent two follow-ups (ps > .29).

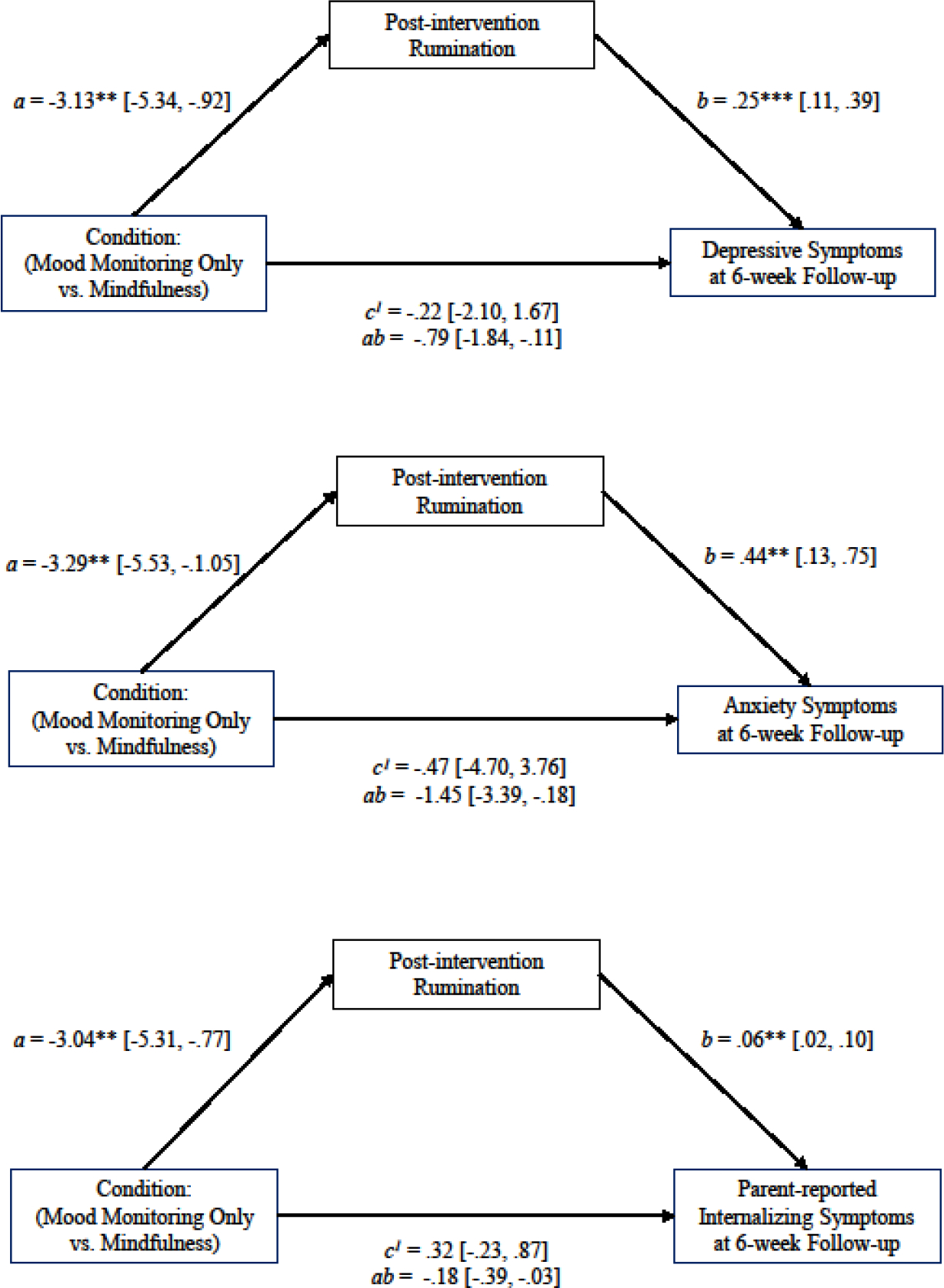

Rumination as a Mediator of Change in Internalizing Symptoms

Our second hypothesis was that the reduction in rumination resulting from the intervention would mediate decreases in internalizing psychopathology during the follow-up period. When examining mediation, there were significant indirect effects of condition on symptoms through rumination (see Figure 3). Participants in the mindfulness condition had a greater reduction in rumination following the intervention period, and this predicted a greater reduction in depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and parent-reported internalizing symptoms during the 6-week follow-up. None of the 95% bootstrap confidence intervals for the indirect effects (i.e., ab paths) overlapped zero, supporting mediation. There was no evidence that condition influenced symptoms independent of its effect on rumination (c1 paths). Importantly, the reverse was not true, i.e., post-intervention symptom changes did not mediate between-condition effects on rumination during follow-up, as all confidence intervals overlapped zero (see Supplemental Fig. 1).

Figure 3.

Indirect Effects of Condition on Symptom Change through Rumination

Clinical Significance

The reliable change index was calculated for post-intervention and for the end of the follow-up period (see Supplemental Table 2). Odds ratios were calculated to examine improvement (% reliable improvers in treatment group/% reliable improvers in comparison group) and deterioration (% reliable deteriorators in treatment group/% reliable deteriorators in comparison group). Odds ratios (OR) of 1.0 indicate an equal likelihood of reliable change in both the treatment and control conditions, an OR > 1.0 indicates a greater likelihood of reliable change in the treatment condition, and an OR < 1.0 indicates a lower likelihood of reliable change in the treatment condition. There was a greater likelihood of improvement in rumination, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms in the mindfulness condition compared to the control condition at post-intervention and at the end of the follow-up period: rumination (ORs = 1.23,1.23), depressive symptoms (ORs = 1.50, 1.31), anxiety symptoms (ORs = 3.25, 2.17). Furthermore, there was a greater likelihood of deteriorating rumination, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms in the control condition relative to the mindfulness condition (ORs = .43-.50). There was no clinically significant change in parent-reported internalizing symptoms in either condition.

Adverse Events

Please see Supplemental Table 3 for additional information related to the clinical trial, including adverse events. Nine events were reported and only four appear related to the study. All four of these events involved an increase in awareness of negative feelings during the intervention period, and there were two participants who reported this in each condition; thus, it may be related to monitoring negative emotions.

Discussion

This RCT examined whether adolescents with elevated rumination assigned to a mindfulness mobile app intervention three times per day for three weeks would show reductions in trait rumination compared to adolescents assigned to a mood monitoring only control. We found support for our hypothesis, and the reduction in rumination seen in the mindfulness group after the intervention lasted through the 6-week follow-up. Furthermore, the reduction in rumination resulting from the intervention mediated group differences in symptom reduction for depression, anxiety, and parent-reported internalizing. These results suggest that the mindfulness mobile app was effective in targeting rumination, as expected, and in turn, reduced internalizing symptoms among ruminative adolescents.

Targeting a Transdiagnostic Risk Factor

Given the high, increasing rates of internalizing symptoms among adolescents, our findings suggest that this type of intervention could be a useful tool for adolescents with moderate-to-high rumination. Rates of depression and anxiety are high among adolescents (Kessler et al., 2005; Merikangas et al., 2010), with a recent cross-national review reporting a 25–31% prevalence of depression and/or anxiety among adolescents ages 10–19 (Silva et al., 2020). Subclinical symptoms, which can confer risk for later diagnosis, also rise in adolescence (Leadbeater et al., 2012). Furthermore, rates of internalizing symptoms have risen in recent cohorts (e.g., Twenge et al., 2018), and this may be amplified by the current global pandemic (e.g., Hawes et al., 2021). Given the high comorbidity rates among disorders (e.g., depression and anxiety), researchers have argued for the importance of focusing on transdiagnostic models of psychopathology (e.g., Insel et al., 2010). Because our intervention successfully targeted a transdiagnostic risk factor for internalizing psychopathology, i.e., rumination, it may have the potential to prevent the development of psychopathology, especially if used by adolescents experiencing high levels of rumination (see Webb et al., 2022). It will be important for future studies to test this intervention over time using diagnostic interviews to examine whether it does in fact, prevent the onset of depression and anxiety disorders.

Acceptability

In addition, this intervention may be especially acceptable for adolescents. In our previous open label study, we found that adolescents enjoyed using the app and parents reported that the app was enjoyable and beneficial for their adolescents (Hilt & Swords, 2021). Furthermore, there were few adverse events reported in this trial or our previous one. The four adverse events that appeared related to the study involved an increased awareness of negative emotions. Because increased awareness of emotions is a goal of both mood monitoring and mindfulness, these events, though mildly distressing, indicate the intervention was working as intended. Because most interventions for internalizing problems involve individual or group treatments led by highly-trained therapists (Weisz et al., 2017) they may not be widely available; unfortunately, the majority of adolescents with depression and anxiety do not receive disorder-specific treatment (Merikangas et al., 2011). The present study provides proof-of-concept that a brief, mobile app intervention is helpful in targeting a transdiagnostic risk factor among adolescents. This is especially important given that no other mindfulness mobile apps in the marketplace have been tested with children or adolescents (Nunes et al., 2020). A recent survey found that 95% of adolescents own a smartphone (Pew Research Center, 2018) and they spend over two-and- a-half hours per day, on average, using it (Rideout, 2015), with some teens already seeking mental health support on their phones (Rideout & Fox, 2018). Therefore, mobile mental health apps like the CARE app can address critical gaps in service and are more accessible to adolescents who may not find more intensive interventions acceptable or may not have access to them due to barriers such as cost and long wait-lists (e.g., Gulliver et al., 2010). This approach is innovative in its practicality on many levels (i.e., low cost, easy to access, widely available) and may also be especially appealing to adolescents who consume much of their media on mobile platforms. An important next step would be to examine the efficacy of this intervention among adolescents with limited access to other mental health resources (e.g., those in low-income rural communities).

Role of Mood Monitoring and Assigning Exercises

Another important avenue for future research involves the role of mood monitoring in the mindfulness intervention. Findings from the present study suggested that brief mindfulness exercises, paired with mood monitoring, were superior in reducing rumination compared to mood monitoring only; yet, it is unclear whether mood monitoring itself is an essential element of this intervention. This is important to understand, as most mindfulness apps for youth involve guided audio exercises without mood monitoring (Nunes et al., 2020). Mobile mood monitoring interventions have been found to help alleviate symptoms in adolescents (Dubad et al., 2018), and in the present study, there was a main effect of time on depressive symptoms during the follow-up period suggesting that mood monitoring, alone and with mindfulness, reduced symptoms. Future research would benefit from comparing a mindfulness-only condition to the mindfulness with mood monitoring one to better understand the role of mood monitoring in the intervention. It is likely that mood monitoring helps with mindfulness skill acquisition by increasing awareness of emotions, and this may make the brief mindfulness exercises more impactful than if they were engaged in alone.

In addition to including mood monitoring, another feature of our app that differs from most other mindfulness apps is the assignment of mindfulness exercises. Most apps allow users to choose from a menu of exercises (Nunes et al., 2020), while the CARE app assigns exercises. We designed the app in this way to better control the dose of mindfulness and also to provide exercises when users may need them most.

Limitations

Some limitations of the study are worth considering. First, it is important to note that the trajectories of rumination and symptoms decreased in the mindfulness condition relative to the control condition; however, the two groups ended up in the same place at the end of the study, suggesting that consistent practice may be needed to maintain gains. Second, participants were paid a bonus to use the app regularly, and it will be important for future research to examine app use without this incentive. Third, although the statistically significant results are bolstered by the clinically significant results showing a greater likelihood of improvement in the mindfulness condition, it will be important for future work to replicate this effect. Finally, the generalizability of findings is also limited to adolescents with elevated rumination. We were particularly interested in whether it could help this population who are at-risk for the development of psychopathology. However, it would be interesting to see if it could also have a protective effect among non-ruminative adolescents and whether it would reduce rumination in adolescents with depression or anxiety diagnoses.

An important consideration in recommending this intervention in other populations, is that some adolescents experienced a deterioration in rumination. Nearly half of the adolescents in the mood monitoring only condition experienced clinically significant worsening of their rumination at the end of the intervention period, and nearly one-quarter of adolescents in the mindfulness intervention did as well. Thus, even though few adverse events were reported, this intervention may not be indicated for all adolescents. Additional research examining which adolescents may benefit from mood monitoring and mindfulness is needed (e.g.,Webb et al., 2022), and care should be taken in recommending this app with a clinical population.

In sum, results from the present study suggests the CARE mobile mindfulness app is a promising, brief, accessible intervention for ruminative adolescents. Future work is needed to examine the extent of generalizability and understand the role of mood monitoring versus mindfulness exercises. Doing so would help inform clinicians, parents, and adolescents about the types of mindfulness apps that may be most useful in targeting rumination to prevent the development of internalizing psychopathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the research assistants who helped with this project, especially Eliana Whitehouse, Eleanor Horner, Liesl Hostetter, Moeka Kamiya, Nina Austria, and Elsa Hammerdahl.

This study was registered with Clinicaltrials.gov (Identifier NCT03900416). Data and analysis code are available upon request. Funding was provided by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award R15MH116303 to LMH. CAW was partially supported by NIMH R01MH116969, NCCIH R01AT011002, the Tommy Fuss Fund and a NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: none.

References

- Abela JR, Brozina K, & Haigh EP (2002). An Examination of the Response Styles Theory of Depression in Third- and Seventh-Grade Children: A Short-Term Longitudinal Study Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 30, 515–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JR & Hankin BL (2011). Rumination as a vulnerability factor to depression during the transition from early to middle adolescence: A multiwave longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120(2), 259–271. 10.1023/A:1019873015594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Schweizer S (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin JS, & Dadds MR (2007). Reliability and validity of parent and child versions of the multidimensional anxiety scale for children in community samples. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(2), 252–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, & Walker S (2014). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. ArXiv preprint arXiv:1406.5823. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Manual for the beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, & Ryan RM (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh K, Strauss C, Cicconi F, Griffiths N, Wyper A, & Jones F (2013). A randomised controlled trial of a brief online mindfulness-based intervention. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(9), 573–578. 10.1016/j.brat.2013.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R, Gullone E, & Allen NB (2009). Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(6), 560–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craighead WE, Curry JF, & Ilardi SS (1995). Relationship of Children’s Depression Inventory factors to major depression among adolescents. Psychological Assessment, 7(2), 171–176. 10.1037/1040-3590.7.2.171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado LC, Guerra P, Perakakis P, Vera MN, Reyes del Paso G, & Vila J (2010). Treating chronic worry: Psychological and physiological effects of a training programme based on mindfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(9), 873–882. 10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyo M, Wilson KA, Ong J, & Koopman C (2009). Mindfulness and rumination: Does mindfulness training lead to reductions in the ruminative thinking associated with depression? EXPLORE, 5(5), 265–271. 10.1016/j.explore.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubad M, Winsper C, Meyer C, Livanou M, & Marwaha S (2018). A systematic review of the psychometric properties, usability and clinical impacts of mobile mood-monitoring applications in young people. Psychological Medicine, 48, 208–228. 10.1017/S0033291717001659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A (2009). Effect sizes for growth-modeling analysis for controlled clinical trials in the same metric as for classical analysis. Psychological Methods, 14(1), 43. 10.1037/a0014699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flett JAM, Hayne H, Riordan BC, Thomson LM, Conner TS (2019) Mobile Mindfulness Meditation: A Randomised controlled trial of the effect of two popular apps on mental health. Mindfulness 10, 863–876 (2019). 10.1007/s12671-018-1050-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL (2008). Rumination and depression in adolescence: Investigating symptom specificity in a multiwave prospective study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(4), 701–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes M, Szenczy A, Klein D, Hajcak G, & Nelson B (2021). Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Medicine, 1–9. 10.1017/S0033291720005358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilt LM, McLaughlin KA, & Nolen-Hoeksema S (2010). Examination of the response styles theory in a community sample of young adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(4), 545–556. 10.1007/s10802-009-9384-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilt LM, & Pollak SD (2012). Getting out of rumination: Comparison of three brief interventions in a sample of youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 1157–1165. 10.1007/s10802-012-9638-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilt LM, & Swords CM (2021). Acceptability and preliminary effects of a mindfulness mobile application for ruminative adolescents. Behavior Therapy, 6, 1339–1350. 10.1016/j.beth.2021.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howells A, Ivtzan I, & Eiroa-Orosa FJ (2016). Putting the ‘app’ in happiness: A randomised controlled trial of a smartphone-based mindfulness intervention to enhance wellbeing. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(1), 163–185. 10.1007/s10902-014-9589-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, et al. (2010). Research domain criteria (RDoC): Toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Ajp, 167(7), 748–751. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson JS, & Truax PT (1991). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59, (1), 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Shapiro SL, Swanick S, Roesch SC, Mills PJ, Bell I, & Schwartz GE (2007). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: Effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distraction. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 33(1), 11–21. 10.1207/s15324796abm3301_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinek MS, Murphy JM, Robinson J, Feins A, Lamb S, & Fenton T (1988). Pediatric symptom checklist: Screening school-age children for psychosocial dysfunction. The Journal of Pediatrics, 112(2), 201–209. 10.1016/S0022-3476(88)80056-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karl JA, & Fischer R (2022). The state of dispositional mindfulness research. Mindfulness, 13, 1357–1372. 10.1007/s12671-022-01853-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kauer SD, Reid SC, Crooke AHD, Khor A, Hearps SJC, Jorm AF, Sanci L, & Patton G (2012). Self-monitoring using mobile phones in the early stages of adolescent depression: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(3), e67. 10.2196/jmir.1858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keune PM, Bostanov V, Hautzinger M, & Kotchoubey B (2011). Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), cognitive style, and the temporal dynamics of frontal EEG alpha asymmetry in recurrently depressed patients. Biological Psychology, 88(2–3), 243–252. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Dougherty LR,& Olino TM (2005). Toward guidelines for evidence-based assessment of depression in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 34 (3), 412–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M (1992). Children’s Depression inventory manual North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Feldman G & Hayes A (2008). Changes in mindfulness and emotion regulation in an exposure-based cognitive therapy for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32, 734–744. 10.1007/s10608-008-9190-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, & Christensen RH (2017). lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software, 82, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater B, Thomson K, & Gruppuso V (2012). Co-occurring Trajectories of Symptoms of Anxiety, Depression, and Oppositional Defiance From Adolescence to Young Adulthood. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychology, 41(6), 719–730. 10.1080/15374416.2012.694608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Parker JDA, Sullivan K, Stallings P, & Conners CK (1997). The multidimensional anxiety scale for children (MASC): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(4), 554–565. 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Sullivan K, & Parker J (1999). Test-retest reliability of the multidimensional anxiety scale for children. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 13(4), 349–358. 10.1016/S0887-6185(99)00009-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA & Nolen-Hoeksema S (2011). Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in depression and anxiety. Behavior Research and Therapy, 49(3), 186–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, et al. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the national comorbidity survey Replication–Adolescent supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swendsen J, Avenevoli S, Case B, et al. (2011). Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results of the national comorbidity Survey–Adolescent supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(1), 32–45. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Roelofs J, Meesters C, & Boomsma P (2004). Rumination and worry in nonclinical adolescents. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28(4), 539–554. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health (n.d.). Prevalence of major depressive episode among adolescents. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression#part_2565

- Nolen-Hoeksema S (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Morrow JA (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 61, 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S & Watkins ER (2011). A heuristic for developing transdiagnostic models of psychopathology: Explaining multifinality and divergent trajectories. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), 589–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, & Lyubomirsky S (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes A, Castro SL, & Limpo T (2020). A review of mindfulness-based apps for children. Mindfulness, 11, 2089–2101. 10.1007/s12671-020-01410-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perestelo-Perez L, Barraca J, Penate W, Rivero-Santana A, & Alvarez-Perez Y (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of depressive rumination: Systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 17(3), 282–295. 10.1016/j.ijchp.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrocchi N, & Ottaviani C (2016). Mindfulness facets distinctively predict depressive symptoms after two years: The mediating role of Rumination. Personality and Individual Differences, 93, 92–96. 10.1016/j.paid.2015.08.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raes F, & Williams JM (2010). The relationship between mindfulness and uncontrollability of ruminative thinking. Mindfulness, 1(4), 199–203. 10.1007/s12671-010-0021-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout V (2015). The commonsense consensus: Media use by tweens and teens. Retrieved from Common Sense Media, Inc.https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/the-common-sense-census-media-use-by-tweens-and-teens [Google Scholar]

- Rideout V, Fox S, & Well Being Trust (2018). Digital health practices, social media use, and mental well-being among teens and young adults in the U.S. Articles, Abstracts, and Reports, 1093. https://digitalcommons.psjhealth.org/publications/1093 [Google Scholar]

- Rood L, Roelofs J, Bögels SM, Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Schouten E (2009). The influence of emotion-focused rumination and distraction on depressive symptoms in non-clinical youth: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(7), 607–616. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Teasdale JD, Williams JM, & Gemar MC (2002). The mindfulness-based cognitive therapy adherence scale: Inter-rater reliability, adherence to protocol and treatment distinctiveness. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 9(2), 131–138. 10.1002/cpp.320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro SL, Brown KW, & Biegel GM (2007). Teaching self-care to caregivers: Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the mental health of therapists in training. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 1(2), 105–115. 10.1037/1931-3918.1.2.105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw ZA, Hilt LM, & Starr LR (2019). The developmental origins of ruminative response style: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 74,101780. 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva SA, Silva SU, Ronca DB, Gonçalves VSS, Dutra ES, & Carvalho KMB (2020). Common mental disorders prevalence in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analyses. PLOS One, 15(4), e0232007. 10.1371/journal.pone.0232007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swords CM & Hilt LM (2021). Examining the relationship between trait rumination and mindfulness across development and risk status. Mindfulness, 12, 1965–1975. 10.1007/s12671-021-01654-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JS, Jamal-Orozco N, & Hallion LS (2019). Differential relationships of the five facets of mindfulness to worry, rumination, and transdiagnostic perseverative thought. Unpublished manuscript. 10.31234/osf.io/kxy67. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Joiner TE, Rogers ML, & Martin GN (2018). Increases in Depressive Symptoms, Suicide-Related Outcomes, and Suicide Rates Among U.S. Adolescents After 2010 and Links to Increased New Media Screen Time. Clinical Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–17. 10.1177/2167702617723376 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Emmerik AAP, Berings F & Lancee J (2018). Efficacy of a mindfulness-based mobile application: A randomized waiting-list controlled trial. Mindfulness, 9, 187–198. 10.1007/s12671-017-0761-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa CD, &, Hilt LM (2014). Brief instruction in mindfulness and relaxation reduce rumination differently for men and women. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 7, 320–333. 10.1521/ijct_2014_07_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins ER, & Roberts H (2020). Reflecting on rumination: Consequences, causes, mechanisms and treatment of rumination. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 127, 103573. 10.1016/j.beth.2021.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb CA, Swords CM, Lawrence H, & Hilt LM (2022). Which adolescents are well-suited to app-based mindfulness training? A randomized clinical trial and data-driven approach for personalized recommendations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 90, 655–669. 10.1037/ccp0000763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Kuppens S, Ng MY, Eckshtain D, Ugueto AM, Vaughn-Coaxum R, Jensen-Doss A, Hawley KM, Krumholz Marchette LS, Chu BC, Weersing VR, & Fordwood SR (2017). What five decades of research tells us about the effects of youth psychological therapy: A multilevel meta-analysis and implications for science and practice. American Psychologist, 72(2), 79–117. 10.1037/a0040360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JMG, & Kuyken W (2012). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: a promising new approach to preventing depressive relapse. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(5), 359–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.