Abstract

InhA, the Mycobacterium tuberculosis enoyl-ACP reductase, is a target for the tuberculosis drug isoniazid. InhA inhibitors that do not require KatG activation avoid the most common mechanism of isoniazid resistance, and there are continuing efforts to fully elucidate the enzyme mechanism to drive inhibitor discovery. InhA is a member of the short chain dehydrogenase/reductase superfamily characterized by a conserved active site Tyr, Y158 in InhA. To explore the role of Y158 in the InhA mechanism, this residue has been replaced by fluoroTyr residues that increase the acidity of Y158 up to ~3,200 fold. Replacement of Y158 with 3-fluoroTyr (3-FY) and 3,5-difluoroTyr (3,5-F2Y) has no effect on nor on the binding of inhibitors to the open form of the enzyme , whereas both and are altered by 7-fold for the 2,3,5-trifluoroTyr variant (2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA). 19F NMR spectroscopy suggests that 2,3,5-F3Y158 is ionized at neutral pH indicating that neither the acidity nor ionization state of residue 158 have a major impact on catalysis or on the binding of substrate-like inhibitors. In contrast, is decreased 6 and 35-fold for the binding of the slow-onset inhibitor PT504 to 3,5-F2Y158 and 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA, respectively, indicating that Y158 stabilizes the closed form of the enzyme adopted by EI*. The residence time of PT504 is reduced ~4-fold for 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA compared to wild-type, and thus the hydrogen bonding interaction of the inhibitor with Y158 is an important factor in the design of InhA inhibitors with increased residence times on the enzyme.

Keywords: Fluorotyrosine, enoyl-ACP reductase, InhA, M. tuberculosis, enzyme inhibition, transition state analog, residence time, 19F NMR spectroscopy

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Despite the availability of cheap and effective drugs, tuberculosis (TB) is still one of the deadliest infectious diseases in the world. The global increase in bacterial resistance coupled with co-infection with the human immunodeficiency virus have led to TB re-emerging as a major infectious disease threat.1 The standard TB treatment regimen is a six month cocktail of four antibiotics that includes isoniazid (INH), rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. INH, a front line antitubercular agent, is a pro-drug (Figure 1) that inhibits InhA, the Mycobacterium tuberculosis enoyl-ACP reductase. Following activation, INH reacts with NAD(H) to generate the INH-NAD-adduct which inhibits InhA (Figure 1).2-4 The primary mechanism of resistance to INH arises from mutations to the catalase-peroxidase enzyme KatG, which is responsible for activating INH.5 To avoid this type of resistance, there are continuing efforts to develop direct inhibitors of InhA that do not require activation by KatG. These efforts will be aided by detailed insight into the catalytic mechanism and active site architecture of the enzyme.6,7

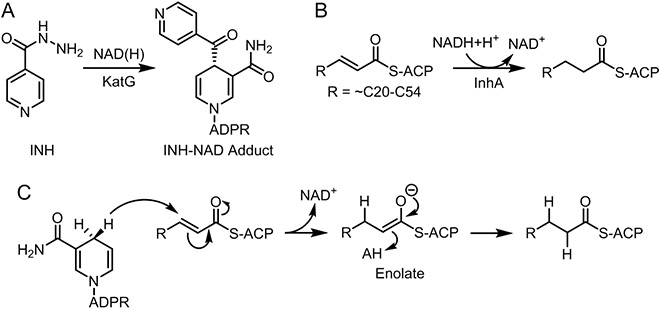

Figure 1. Isoniazid and the Reaction Catalyzed by InhA.

A) Formation of the INH-NAD adduct from INH and NAD(H). B) InhA catalyzes the NADH-dependent reduction of the enoyl-ACP double bond in the Type II fatty acid biosynthesis pathway. C) Formation of an enolate intermediate during substrate reductio which involves hydride transfer from NADH to C3 of the substrate followed by protonation of the enolate.

InhA catalyzes the NADH-dependent reduction of enoyl-ACP substrates in the last step of the FAS-II fatty acid biosynthesis pathway (Figure 1).4,8,9 The products of this pathway are used for the synthesis of mycolic acids, C60-C90 fatty acid components of the M. tuberculosis cell envelope. Inhibition of InhA thus compromises the integrity of the cell envelope accounting for the bactericidal activity of INH.

Extensive efforts to identify direct InhA inhibitors have resulted in the discovery of many potent and structurally distinct compound series,6,7,10-12 including the diphenyl ether scaffold series that are uncompetitive inhibitors, binding to the InhA-NAD+ complex.13,14 The diphenyl ethers inhibit InhA through a two-step, induced-fit mechanism similar to that of the INH-NAD adduct.15-17 Structural studies have revealed that conversion of EI to EI* involves reorganization of the substrate binding loop which involves movement of helix-6 from an open conformation to a closed conformation,18 and molecular dynamics simulations coupled with site-directed mutagenesis identified a steric clash between residues on helix-6 and helix-7 in the transition state (TS) on the binding reaction coordinate.19 Knowledge of the transition state structure led to the design of a series of triazole-based diphenyl ethers which demonstrate residence times of over 200 min on InhA by destabilizing the transition state.20

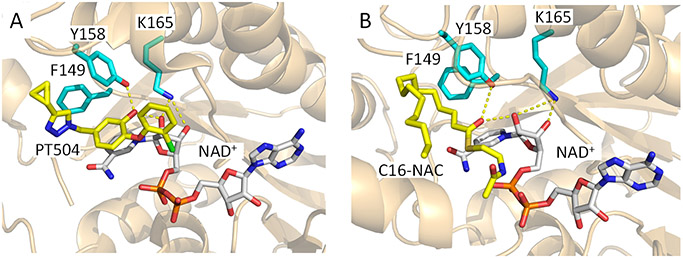

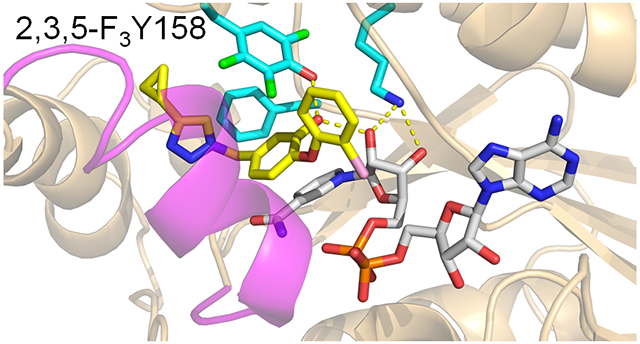

In addition, to revealing the mechanism of time-dependent inhibition, the structural studies also demonstrated that the diphenyl ether phenol forms a hydrogen bonding interaction with Y158, a Tyr that is part of a conserved Y-(X)n-K motif found in the short chain dehydrogenase reductase (SDR) superfamily. In InhA, where n=6, the conserved K165 forms interactions with the NADH ribose which in turn is also hydrogen bonded to the inhibitor phenol group (Figure 2). These interactions are recapitulated in the structure of the C16-NAC substrate analog bound to InhA (Figure 2), and it has been proposed that the hydrogen bonding network plays a key role in catalysis by stabilizing the enolate intermediate formed via hydride ion transfer from the NADH cofactor to the C3 position of the substrate (Figure 1).9,21 Given that the pKa of the diphenyl ether phenol group is ~8-9, it follows that the active site could also stabilize the anionic phenolate form of the inhibitor, thereby mimicking the transition state for the enzyme-catalyzed reaction.22 Elucidating the role of the hydrogen bonding network in enzyme inhibition is thus of interest for future inhibitor discovery and optimization.

Figure 2. InhA in Complex with an Inhibitor and a Substrate Analog.

The catalytic triad in InhA is comprised of K165, Y158 and F149. A) X-ray structure of InhA bound to NAD+ and the diphenyl ether inhibitor PT504 (5ugt.pdb).20 B) X-ray structure of InhA in complex with NAD+ and a C16 fatty acyl substrate analog (1bvr.pdb).21 Both the Y158 and ribose C2’ hydroxyl groups are within hydrogen bonding distance of the diphenyl ether hydroxyl group and the substrate carbonyl group. The figure was made with pymol.23

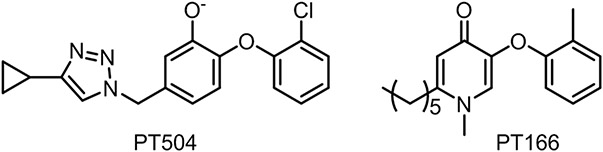

The role of Y158 in the catalytic mechanism has previously been investigated with site-directed mutagenesis. Although replacement with a Ser had no effect on catalytic efficiency, the Y158F and Y158A mutants had values that were reduced 24-fold and 1500-fold, respectively, in contrast to that of the wild-type enzyme.2 A subsequent study demonstrated that the diphenyl ether inhibitor triclosan bound with ~100-fold lower affinity to the Y158F mutant compared to wild-type InhA.13 While the data on Y158F InhA mutant apparently support a key role of the Y158 hydroxyl in catalysis and inhibition, it is intriguing that Y158S InhA has wild-type activity. To provide additional insight into the mechanism of substrate reduction and enzyme inhibition, in the present work we replaced Y158 with fluoroTyr residues that result in up to a ~3,200-fold increase in the acidity of the phenol hydroxyl group. Using enzyme kinetics, progress curve analysis and 19F NMR spectroscopy, we have explored the impact of changing the Y158 pKa on substrate reduction was well as on the inhibition of the enzyme by the rapid-reversible 4-pyridone inhibitor PT166 and by the slow-onset diphenyl ether inhibitor PT504 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. InhA Inhibitors.

PT504 is a diphenyl ether-based inhibitor of InhA that binds to InhA through a two-step induced-fit mechanism. PT166 is a 4-pyridone-based inhibitor that resembles the InhA substrate and binds through a one-step rapid reversible mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Antibiotics were purchased from Gold Biotechnology. 2-Fluorophenol and 2,6-difluorophenol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. 2,3-Difluorophenol was purchased from Acros Organics. 2,3,6-Trifluorophenol was purchased from Oakwood Chemical. Luria Broth and 2x -YT media were purchased from Millipore-Sigma.

Tyrosine Phenol Lyase (TPL) Expression and Purification.

Tyrosine phenol lyase (TPL; UniProt Accession ID P31013) was expressed and purified as described previously.24 BL21 (DE3) pLysS Escherichia coli (E. coli) competent cells were transformed with a plasmid containing the gene for TPL and plated on LB agar containing ampicillin and chloramphenicol. After incubation overnight at 37°C, a single colony was used to inoculate a starter culture of 10 mL LB media containing 0.5 mM ampicillin and 0.5 mM chloramphenicol. The culture was shaken overnight (250 rpm) at 37°C and then was used to inoculate 1 L LB media containing ampicillin and chloramphenicol in 4 L flasks. The flasks were shaken at 250 rpm and 37°C for ~3 h until the OD600 reached ~0.8, after which the culture was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG. The temperature was then decreased to 25 °C and the cultures were incubated overnight. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6,238xg, and immediately resuspended in lysis buffer (0.1 M NaH2PO4 buffer pH 7.0, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 5 mM β- mercaptoethanol, 0.1 mM pyridoxal 5′phosphate). The cells were then lysed by sonication (6 x 45 s at 18 W and 1 min on ice between cycles) and cell debris was removed by ultra-centrifugation (185,511x g for 1 h). TPL was purified from the supernatant by Ni-NTA chromatography using a 2 cm x 20 cm column and 0.1 M NaH2PO4, pH 7.0 buffer containing 150 mM NaCl and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, which also contained increasing concentrations of imidazole (0, 10 and 20 mM), followed by protein elution in 5 mL fractions of the same buffer containing 250 mM imidazole. Fractions containing TPL were pooled and loaded onto a size exclusion column (Sephadex G-25), in which the chromatography was performed with 0.1 M NaH2PO4 pH 7.0 buffer containing 150 mM NaCl. Fractions containing TPL were collected, and the purity of the protein was shown to be >95% by SDS-PAGE. After concentrating to ~ 5 mg/mL, the purified TPL was directly used for the fluoroTyr (FxY) synthesis.

FluoroTyr (FxY) Synthesis.

3-FluoroTyr (3-FY), 3,5-difluoroTyr (3,5-F2Y) and 2,3,5-trifluoroTyr (2,3,5-F3Y) were synthesized from 2-fluorophenol, 2,6-difluorophenol and 2,3,6-trifluorophenol, respectively, following a method described by Stubbe and co-workers.25 The reaction mixture (1 L) contained 60 mM sodium pyruvate, 40 μM pyridoxal-5’-phosphate, 30 mM NH4OAc, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 10 mM fluorophenol. The pH was adjusted to 8.0 by adding NH4OH to the reaction mixture. To initiate the reaction, 160 units/L (0.53 mg = 1 unit) of purified TPL was added, and the reaction was stirred in the dark at room temperature. An additional 40 units of TPL was added to the reaction mixture after 24 h, and after a further 6 days the reaction mixture was quenched by adding 5% TFA. Precipitated enzyme was removed by gravity filtration, and the mixture was extracted three times with three equivalents of ethyl acetate to remove excess phenol. The aqueous layer was then directly loaded onto a 200 mL cation exchange Amberlite column that was activated with 2 N HCl. After washing with H2O, the FxY amino acids were eluted with 10% NH4OH. Fractions containing FxY were identified using ninhydrin (4%), combined, and concentrated using a rotatory evaporator after which the solution was lyophilized to yield the FxY amino acids which were stored at room temperature.24

Incorporation of FluoroTyr Residues using an Orthogonal Amino-acyl-tRNA Synthetase.

The three fluorinated derivatives of Tyr, 3-FY, 3,5-F2Y and 2,3,5-F3Y were incorporated into position 158 of InhA (UniProt Accession ID P9WGR1) using an orthogonal polyspecific aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase, E3, generously provided by Prof. Stubbe.25 Site-directed mutagenesis was used to replace the Y158 codon (TAC) with the amber codon (TAG) in a pET23b plasmid in which a C-terminal 6-His-tag followed the gene for InhA, enabling the separation of the full-length protein from the truncated InhA. This plasmid was co-transformed into BL21(AI) E. coli cells together with the E3 pEVOL plasmid and plated on LB agar containing 200 μg/mL ampicillin and 50 μg/mL chloramphenicol to select cells harboring both plasmids. After incubation overnight at 37 °C, two individual colonies were used to inoculate a starter culture of 5 mL media containing 200 μg/mL ampicillin and 50 μg/mL chloramphenicol. The culture was shaken overnight (250 rpm) at 37 °C and then was used to inoculate 500 mL 2x-YT media containing ampicillin and chloramphenicol in 4 L flasks. The culture was grown until the OD600 reached ~0.4 (after ~1 h), when the FxY analogues (0.5 mmol) dissolved in 10 mL of 2x-YT media were added to the culture. After 30 min of incubation, 0.05% w/v arabinose was added to the culture to induce expression of the E3 synthetase. Cells were grown until the OD600 reached ~1, after which expression of InhA was induced with 1 mM IPTG. The temperature was then decreased to 25 °C and the culture was incubated overnight. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6,238xg for 15 min at 4 °C, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 40 mL lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.9 buffer containing 0.5 M NaCl, 5 mM imidazole). The bacteria were then disrupted by sonication followed by centrifugation at 185,511x g for 60 min at 4 °C to remove cell debris. The clear supernatant was loaded onto a Ni-NTA affinity column (2 x 20 cm) which was then washed with the same Tris buffer containing increasing concentrations of imidazole (5, 30 and 60 mM) until FxY158 InhA was eluted with buffer containing 500 mM imidazole. Fractions containing proteins were pooled and subjected to gel filtration chromatography using a Superdex 200 size exclusion column on an Akta. Chromatography was performed with 30 mM PIPES buffer pH 6.8 containing 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and fractions containing FxY158 InhA were pooled and shown to be >95% pure using SDS-PAGE. Aliquots of FxY158 InhA (50 μL) were flash frozen and stored at −80°C. Since a C-terminal His-tag was used, only fully translated protein bound to the Ni-NTA resin, thus selecting against InhA lacking an amino acid at position 158. The incorporation of FxY into InhA was assessed using mass spectrometry following tryptic digest and shown to be >99% in each case. For 3-FY158 InhA, mass spectra were acquired using a Bruker Impact II quadrupole time-of-flight (QTOF, Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA) equipped with an Agilent 1290 Infinity II UHPLC system, while mass spectra of peptides obtained from 2,3-F2Y158 InhA and 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA were obtained using a Thermo Orbitrap-XL instrument. Peptide sequences were identified via database searching of peak list files using the Mascot search engine.

Substrate Synthesis.

Trans-2-octenoyl-CoA (C8-CoA) and trans-2-dodecenoyl-CoA (DD-CoA) were synthesized from their corresponding acids using the mixed anhydride method as described previously.2,9

Steady State Kinetics.

Kinetics parameters were determined at 25 °C in 30 mM PIPES buffer pH 6.8 containing 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA by monitoring the oxidation of NADH at 340 nm using a Cary 100 spectrophotometer (Agilent). Assays contained 100-117 nM InhA. The and values for trans-2-dodecenoyl-CoA (dd-CoA) and NADH were determined by varying the concentration of dd-CoA from 0-180 μM while keeping the concentration of NADH fixed at 250 μM, or by varying the concentration of NADH from 0-500 μM while keeping the concentration of dd-CoA at 80 μM for wild-type InhA, 3FY158 InhA and 3,5-F2Y158 InhA or at 135 μM for 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA.26 Values for and were obtained by fitting the initial velocity data to the Michaelis Menten equation using GraphPad Prism.

Direct Binding Fluorescence Titration Assay.

Equilibrium fluorescence titrations were conducted using a Quanta Master (QM4) fluorometer (Photon Technology International) at 25 °C in 30 mM PIPES buffer pH 6.8 containing 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA. The excitation wavelength was 350 nm (1.5 nm slit width), and the emission wavelength was 455 nm (2 nm slit width). Experiments were carried out in a 1 mL solution of 0.8 – 1.5 μM protein, which was titrated with 0 – 100 μM NADH. The fluorescence intensity was recorded at 455 nm, and the fluorescence intensity data as a function of NADH concentration were fit to Equation 1 where and are the change in fluorescence intensity and the maximum change in fluorescence intensity, respectively, Kd is the dissociation equilibrium constant, [E]0 is the total enzyme concentration, and [NADH] is the total concentration of NADH. Data fitting was performed using GraphPad Prism.

| (1) |

Progress curve analysis.

Time-dependent enzyme inhibition experiments were performed on a Cary 100 spectrophotometer (Agilent) at 25 °C by monitoring the oxidation of NADH to NAD+ as described previously.20 Briefly, reactions were initiated by adding enzyme (30 – 50 nM) to a reaction mixture containing 400 μM octenoyl-CoA, 250 μM NADH, 200 μM NAD+, 1% v/v DMSO, and 0 - 20 μM of the inhibitor. Under these conditions time-dependent enzyme inhibition leads to curvature in the forward progress curves which were fit to the Morison & Walsh integrated rate equation (Equation 2).27

| (2) |

In Equation 2, At and A0 are the absorbance at time t and time 0, respectively, and are the initial and steady state velocities, respectively, and is the rate constant for conversion of the initial velocity to the steady state velocity. The values of k6, and were calculated by global fitting of the forward progress curve data, obtained for different inhibitor concentrations, to equations 2 to 5.

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

For the rapid-reversible pyridone inhibitor (PT166) all experimental data were fit to Equations 6 and 7.

| (6) |

| (7) |

Non-linear curve fitting was performed using GraphPad Prism.

pH titration of 2,3,5-F3Y158 in InhA using NMR spectroscopy.

19F NMR was used to determine the pKa of residue 2,3,5-F3Y158 in InhA. A 130 μM solution of InhA in 30 mM PIPES buffer pH 6.8 containing 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA was lyophilized and redissolved in D2O for the NMR experiments, a process that did not affect the enzyme activity. The pD was adjusted using DCl or NaOD to obtain pD values between 4.7 and 9.1. InhA was unstable below and above these pD values. 19F NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker Avance III HD 700 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a 5-mm QCI-F cryoprobe. 1D 19F NMR acquisition parameters were as follows: a 60o pulse, 80 ppm sweep width, 1.8 s repetition time, and 2048 scans (64 min). Spectra were referenced indirectly to neat CFCl3, and were processed with 50 Hz exponential line broadening followed by manual baseline correction.

As a control, the pKa of 2,3,5-F3Y in solution was also measured using a Bruker III HD Nanobay 400 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a 5-mm BBFOplus probe. 2,3,5-F3Y (5 mg) was dissolved in 30 mM deuterated PIPES buffer and the pD was adjusted using DCl or NaOD to obtain pD values between 3.6 and 12.5. For 2,3,5-F3Y in solution the 19F NMR chemical shift was plotted as a function of pD and pKa values were calculated by fitting the data in GraphPad Prism (Figure S1). Resonance assignments for the 19F signals of free 2,3,5-F3Tyr were obtained by 1D 19F NMR with selective 1H decoupling and confirmed with a 2D 19F-1H HOESY (heteronuclear Overhauser spectroscopy).

RESULTS

Equilibrium Binding of NADH to wild-type InhA and FxY158 InhA.

Dissociation constants of NADH for wild-type and the FXY variants were 7-9 μM (Table 1). In previous studies it was found that NADH had a value of ~0.5-1 μM for InhA, therefore introduction of a C-terminal His-tag, used to ensure that only fully translated protein containing the FxY amino acids would be purified by Ni-affinity chromatography, has altered NADH binding. However, the similarity of the values for wild-type and FxY InhA demonstrates that introduction of FxY residues into position Y158 has not perturbed the NADH binding site.

Table 1.

values of NADH binding to wild type and FxY158 substituted InhA1

| (μM) | N2 | |

|---|---|---|

| wild-type InhA | 8.2 ± 0.3 | 3.1 ± 0.3 |

| 3-FY158 InhA | 7.1 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.3 |

| 3,5-F2Y158 InhA | 8.1 ± 0.5 | 3.0 ± 0.5 |

| 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA | 8.7 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.2 |

Errors are the standard error on fitting the data to Equation 1.

N is the Hill coefficient.

Effect of Y158 fluorination on InhA enzymatic activity.

Steady-state kinetic parameters for wild-type, 3-FY158 InhA, 3,5-F2Y158 InhA, and 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA, were determined by varying the concentration of trans-2-dodecenoyl-CoA (dd-CoA) at a fixed concentration of NADH (Table 2), or varying the concentration of NADH at a fixed concentration of dd-CoA. Wild-type InhA had and values for dd-CoA of 525 ± 58 min−1 and 27 ± 8 μM, respectively, in agreement with the previously reported kinetic parameters for wild-type InhA.2 In keeping with the change in affinity observed for the binding of NADH (Table 1), the value for NADH was increased ~3-fold compared to the value observed for N-terminal His-tag InhA.2 The corresponding and values for 3-FY158 InhA, and 3,5-F2Y158 InhA were similar to those observed for the wild-type enzyme. However, while the value for 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA was also similar to wild-type InhA, the value for dd-CoA was ~5-fold higher than for wild-type InhA, leading to a ~6-fold decrease in of 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA compared to the wild-type enzyme.

Table 2.

Kinetics parameter of wild-type and FxY158 InhA1

|

(min−1) |

(μM) |

(μM) |

(μM−1 min−1) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wild-type | 525 ± 58 | 27 ± 8 | 228 ± 55 | 19 ± 6 |

| 3-FY158 | 363 ± 86 | 28 ± 16 | 183 ± 86 | 13 ± 8 |

| 3,5-F2Y158 | 414 ± 73 | 17 ± 8 | 282 ± 128 | 24 ± 12 |

| 2,3,5-F3Y158 | 395 ± 158 | 126 ± 53 | 294 ± 142 | 3 ± 2 |

Errors are the standard error from fitting the data to the Michaelis Menten equation

Tyr pKa and Inhibitor Binding.

Structural studies indicate that InhA inhibitors such as the 4-pyridones and diphenyl ethers form a stacking interaction with the NAD(H) nicotinamide ring and that the carbonyl group of the 4-pyridones or the phenolic hydroxyl group of the diphenyl ethers form a hydrogen bond with Y158 as well as with the ribose hydroxyl group of the co-factor.13,20,28 To investigate the impact of altering the acidity of the Y158 hydroxyl group on enzyme inhibition, we quantified the binding of the pyridone PT166 and the diphenyl ether PT504 to InhA.

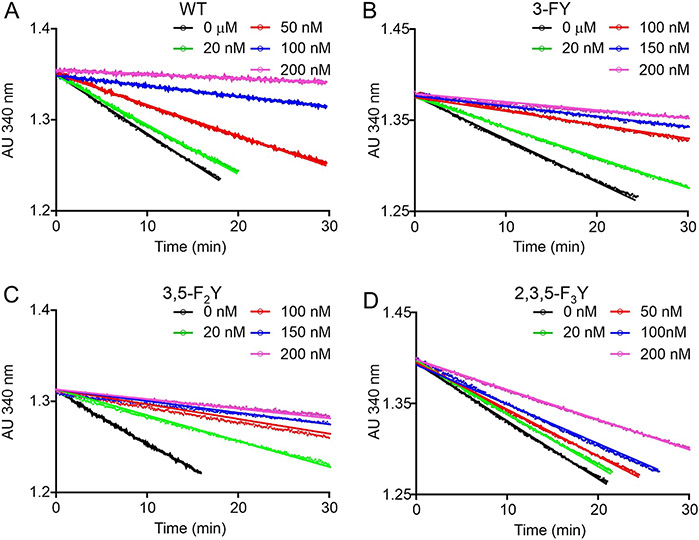

PT166.

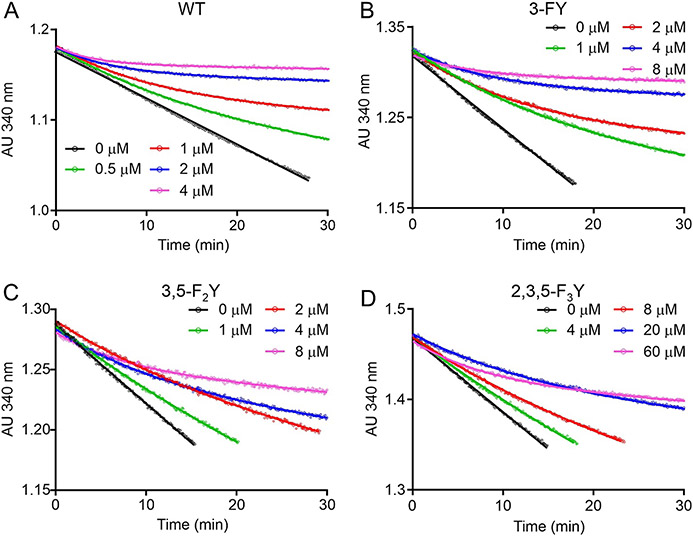

Pyridone-based compounds are substrate analogs and rapid-reversible inhibitors of InhA. In agreement, no curvature was observed in the progress curves for enzyme inhibition, demonstrating that PT166 is a rapid reversible inhibitor of wild-type InhA and the FxY158 variants (Figure 4). Global fitting of the progress curve data gave values of 30-50 nM for inhibition of wild-type, 3-FY, and 3,5-F2Y158 InhA, and 213 nM for 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA by PT166 (Table 3). These values indicate that binding affinity of PT166 for 3-FY158 and 3,5-F2Y158 InhA resembles wild-type InhA, while in the 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA variant it is ~ 7-fold decreased compared to wild-type (30 nM).

Figure 4. Forward progress curve analysis for the inhibition of wild-type and FXY InhA by PT166.

A) wild-type InhA. B) 3-FY158 InhA. C) 3,5-F2Y158 InhA. D) 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA. Data were globally fit to equations 6 and 7 to generate values for enzyme inhibition. All experiments were performed in triplicate and solid lines are the result of global fitting.

Table 3.

for inhibition of wild-type and FXY InhA by PT1661

| wild-type InhA | 3-FY158 InhA | 3,5-F2Y158 InhA | 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (nM) | 31 ± 1 | 33 ± 1 | 48 ± 1 | 213 ± 2 |

Experiments were performed in triplicate and errors are the standard deviation obtained from global nonlinear fitting of the data

Diphenyl Ether-based Inhibitors.

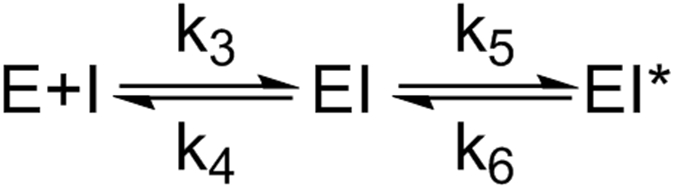

In general, the diphenyl ethers are transition state analogs of the InhA catalyzed reaction and bind to the enzyme through a two-step induced-fit mechanism (Scheme 1).20

Scheme 1: Two-step binding mechanism.

In agreement, the progress curves for InhA inhibition by PT504 displayed curvature (Figure 5) and global fitting of the data yielded values for and , the equilibrium constants for the formation of EI and EI*, respectively, as well as which is the rate constant for breakdown of EI* (Table 4). The results indicate that the impact of modulating the Y158 pKa is more pronounced on inhibition of InhA by PT504 than by PT166. Specifically, replacement of Y158 with 2,3,5-F3Y158 results in a 34-fold increase in for PT504 compared to a 7-fold change in for PT166. In addition, the residence time of PT504 for InhA is reduced by ~4-fold for 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA compared to wild-type.

Figure 5. Forward progress curve analysis for the inhibition of wild-type and FXY InhA by PT504.

A) Wild-type InhA. B) 3-FY158 InhA. C) 3,5-F2Y158 InhA. D) 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA. Data were globally fit to equations 2-5 to generate and values for enzyme inhibition. Residence times were calculated by taking the reciprocal of . All experiments were performed in triplicate and solid lines are the result of global fitting to all data sets using GraphPad Prism.

Table 4.

The result of global fitting of PT504 and wild-type and FxY158 InhA1

| wild-type InhA | 3-FY158 InhA | 3,5-F2Y158 InhA | 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (μM) | 16 ± 10 | 3 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 |

| (μM) | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 2.4 ± 0.1 |

| (min−1) | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.009 ± 0.002 | 0.012 ± 0.001 | 0.02 ± 0.01 |

| 220 ± 49 | 117 ± 26 | 83 ± 1 | 51 ± 1 |

Experiments were performed in triplicate and errors are the standard deviation obtained from global nonlinear fitting of the data..

pH titration of 2,3,5-F3Y InhA using 19F NMR.

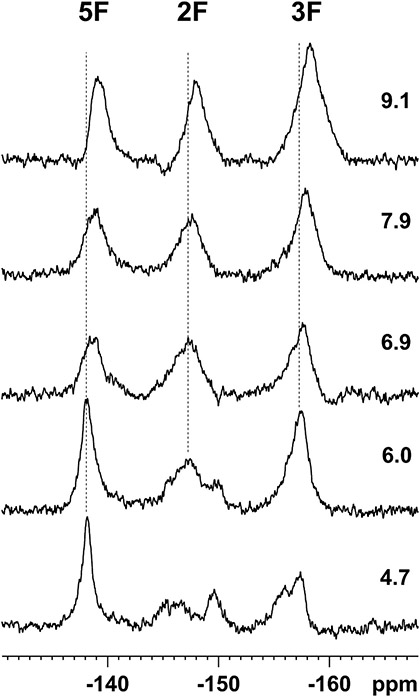

Given the relatively modest change in enzyme activity and inhibition caused by introduction of the fluoroTyr analogs into position 158 we were curious about whether the decrease in pKa of the phenolic hydroxyl group had altered the ionization state of the reside in the active site. We chose the most acidic variant for these experiments and used the 19F NMR chemicals shifts of each fluorine in 2,3,5-trifluoroTyr to determine the pKa of the free amino acid and of the residue in InhA. For the free amino acid, the chemical shift of each fluorine varied with pH, providing, in each case, a pKa value of 6.5 for the hydroxyl group that is consistent with the reported pKa of this unnatural amino acid (Figure S1). For 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA, the pH titration was performed from pH 4.7 to 9.1 since the protein was unstable at more acidic or basic pH values (Figure 6). Between pD 6 and 4.7 there was a significant decrease in peak intensity, suggesting issues with protein stability. From pD 6-9.1 the chemical shift of each fluorine varied with pH giving pKa values of 7 for the 2F and 8 for the 3F and 5F (Figure S1). However, in each case the change in fluorine chemical shift varied over a smaller range of chemical shifts in the protein than for the amino acid in solution (0.7-0.8 ppm compared to 1.2-2.1 ppm respectively).

Figure 6. Stacked plot of 19F NMR spectra of 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA from pD 4.7 to 9.1 at 658.8 MHz.

19F NMR spectra were acquired at 25 °C for 64 min (2048 scans) on a Bruker Avance III HD 700 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a 5-mm QCI-F cryoprobe as described in the Methods section. Resonances at ~138, 147 and 158 ppm are assigned to the 5F, 2F and 3F, respectively.

DISCUSSION

InhA, the enoyl-ACP reductase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is a component of the FAS-II fatty acid biosynthesis pathway and catalyzes the NADH-dependent reduction of long chain enoyl-ACPs. Products of the pathway are used in the synthesis of mycolic acids which are an essential constituent of the mycobacterial cell wall and several enzymes in the FAS-II pathway are targets for antibacterial drug development. InhA (FabI) is inhibited by the front-line anti-tuberculosis drug isoniazid and there are on-going efforts to develop InhA inhibitors that do not require activation by KatG, thus avoiding the primary mechanism of resistance to isoniazid. To aid in inhibitor discovery there have been extensive efforts to explore the mechanism of InhA and identify interactions critical for substrate reduction and ligand binding. Here we interrogate the role of Y158, the conserved active site Tyr, in catalysis and enzyme inhibition.

InhA is a member of the short chain dehydrogenase reductase (SDR) superfamily categorized by the presence of a Rossmann-fold that binds the NAD(P) cofactor and a highly conserved Tyr residue.29-32 The active site of many SDR enzymes also contains Ser and Lys residues that form a catalytic triad with the Tyr, although in the enoyl-ACP reductases enzyme (FabI) from E. coli the Ser is replaced with a Tyr residue, while in InhA it is a Phe (F149). The Ser residue in the NAD+-dependent dehydrogenases is thought to assist in polarization of the substrate carbonyl group,33 while the Tyr functions as an acid-base catalyst to either protonate or deprotonate the substrate, and the Lys binds the cofactor and enhances the acid/base properties of the Tyr,33-36 as proposed in the mechanism of the reaction catalyzed by E. coli 7α-HSDH.37

In the reductase family members, the conserved Tyr (Y158) is hydrogen bonded to the substrate carbonyl together with the NAD(H) ribose 3’-OH, while the catalytic Lys (K165 in InhA) plays a role in cofactor binding, forming hydrogen bonds with the NAD ribose group (Figure 2). However, while Y146, the Tyr homolog in E. coli FabI, can in principal hydrogen bond to the substrate, F149 in InhA cannot perform this function.38 The proposed mechanism for substrate reduction catalyzed by the reductase family members involves hydride transfer from the 3S NADH to the C3 carbon of the enoyl substrate leading to the formation of an enolate intermediate,9,13,18,21 and in InhA the transition states for hydride transfer and protonation of the enolate intermediate are both partially rate-limiting.2

The conserved Tyr in the enoyl-ACP reductases has been proposed to catalyze the reaction either by stabilizing the enolate via hydrogen bonding or, by analogy with the dehydrogenases, by protonating the enolate to generate an enol.21,39-41 In keeping with the potential importance of this residue in catalysis, the Y158F and Y158A enzymes have values that are decreased by 24-fold and 1500-fold, respectively, compared to wild-type InhA.2 In addition, Vogeli et al.42 reported that substitution of Y158 with a Ser residue also has a major impact on enzyme activity, resulting in a reduction in of 400-700-fold. We have now confirmed this result (data not shown) given that we had previously reported that the Y158S mutation had little impact on activity.

To provide a more subtle exploration of the role of Y158, we have replaced Y158 with fluoroTyr residues that alter the pKa of the phenol by up to 3.5 pH units. The FxY158 variants have similar affinities for NADH, indicating that the cofactor binding site has not been perturbed. In addition, the more than a 100-fold increase in the acidity of the Tyr hydroxyl group from wild-type to 3,5-F2Y158 InhA has no effect on the catalytic efficiency. Further alteration in the pKa of residue Y158 does have a modest impact on catalysis, where the for 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA is decreased 7-fold compared to wild-type InhA. Given that 2,3,5-F3Y in solution has a pKa of 6.5, it is plausible that 2,3,5-F3Y158 is partially or completely ionized. To explore this possibility, we used fluorine NMR spectroscopy to determine the pKa of 2,3,5-F3Y158 which gave values of 7-8 over the accessible pH range depending on which fluorine was monitored. Thus 2,3,5-F3Y158 could be partially protonated at pH 6.8, explain why this replacement had a more significant impact on catalysis.

Similar results were observed for binding of the substrate-like 4-pyridone inhibitor PT166 where replacing Y158 with 3-FY and 3,5-F2Y had no effect on binding while affinity was reduced 7-fold for the 2,3,5-F3Y158 compared to the wild-type enzyme. In addition, formation of the initial EI complex for the binding of the slow-onset two step inhibitor PT504 was similarly affected, with a 7-fold increase in for 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA. Taken together, the studies indicate that the pKa of the residue at position 158 has only a minor impact on catalysis and on the binding of substrate or inhibitor to the form of the enzyme that has an open substrate binding loop. Based on studies with 2,4-dienoyl-CoA reductase it has been proposed that stabilization of the enolate intermediate might be counterproductive, since this would increase the activation energy for proton transfer,43 and thus the single hydrogen bond to the substrate carbonyl provided by the ribose 3’OH in InhA may be sufficient to catalyze the reaction. Our observations are also consistent with similar studies on ketosteroid isomerase where increasing the acidity of the Tyr in the oxyanion hole had no significant impact on the catalytic efficiency.44

In contrast, alteration in Y158 acidity had a more marked impact on the conversion of EI to EI* for PT504, where was increased 6-fold for 3,5-F2Y158 and 35-fold for 2,3,5-F3Y158 InhA with a concomitant decrease in inhibitor residence time from 220 min to 50 min. Structural studies have shown that formation of EI* results in a closed state of the substrate binding loop in which helix-6 forms van der Waals interactions where the ACP substrate is expected to bind,18 such that the closed conformation of helix-6 is not part of the reaction pathway for the normal catalytic cycle of InhA.18 Therefore, the change in Tyr pKa has altered the stability of the closed state by up to 2 kcal/mol.

The modest changes in rate caused by replacing Y158 with fluoroTyr residues argues against this residue providing major stabilization to the transition state(s) for substrate reduction. However, Y158 is highly conserved in the SDR family indicating that this residue must play a central role in catalysis. In this regard, the ability of Y158F InhA to form an adduct between NADH and octenoyl-CoA has shown that Y158 plays a critical role in the stereospecificity of the reaction.42 Thus, while the equivalent residue in dehydrogenases may function as a proton donor, in the reductases the conserved Tyr may play a more important role in positioning the substrate for the stereospecific reaction. Finally, it is worth noting that the FAS-II pathway catalyzes the synthesis of fatty acids up to ~C60 in length, and thus it is plausible that the impact of the altering the pKa of Y158 on catalysis may be more marked with the natural substrates, which for InhA are very long chain (>C18) enoyl-ACPs rather than short chain enoyl-CoAs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM102864 to P.J.T.). J.N.I. and Y. L. were supported by an NIH Chemistry-Biology Interface training grant at Stony Brook University (T32 GM092714) and J.T.C. was supported by the IMSD-MERGE Program (T32 GM103962) and the IRACDA Program (K12 GM102778) at Stony Brook University. NMR data presented herein were collected in part at the City University of New York Advanced Science Research Center (CUNY ASRC) Biomolecular NMR Facility. The authors would like to thank Denize Favaro, Ph.D. (CUNY-ASRC) for assistance with the NMR experiments and helpful discussions.

Footnotes

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): P.J.T. is the cofounder of Chronus Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://

Supplementary figure S1, Fluorine NMR pH Titration of 2,3,5-trifluoroTyr

Analytical data for the fluoroTyr amino acids and fluoroTyr incorporation into InhA.

REFERENCES

- (1).Zumla A; George A; Sharma V; Herbert RH; Masham Baroness of, I.; Oxley A; Oliver M The WHO 2014 global tuberculosis report--further to go Lancet Glob Health, 2015, 3, e10–12. DOI: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70361-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Parikh S; Moynihan DP; Xiao G; Tonge PJ Roles of tyrosine 158 and lysine 165 in the catalytic mechanism of InhA, the enoyl-ACP reductase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis Biochemistry, 1999, 38, 13623–13634. DOI: 10.1021/bi990529c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Rozwarski DA; Grant GA; Barton DH; Jacobs WR Jr.; Sacchettini JC Modification of the NADH of the isoniazid target (InhA) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis Science, 1998, 279, 98–102. DOI: 10.1126/science.279.5347.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Chollet A; Maveyraud L; Lherbet C; Bernardes-Genisson V An overview on crystal structures of InhA protein: Apo-form, in complex with its natural ligands and inhibitors Eur J Med Chem, 2018, 146, 318–343. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.01.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Seifert M; Catanzaro D; Catanzaro A; Rodwell TC Genetic mutations associated with isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a systematic review PLoS One, 2015, 10, e0119628. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Xia Y; Zhou Y; Carter DS; McNeil MB; Choi W; Halladay J; Berry PW; Mao W; Hernandez V; O'Malley T; Korkegian A; Sunde B; Flint L; Woolhiser LK; Scherman MS; Gruppo V; Hastings C; Robertson GT; Ioerger TR; Sacchettini J; Tonge PJ; Lenaerts AJ; Parish T; Alley M Discovery of a cofactor-independent inhibitor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis InhA Life Sci Alliance, 2018, 1, e201800025. DOI: 10.26508/lsa.201800025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Manjunatha UH; SP SR; Kondreddi RR; Noble CG; Camacho LR; Tan BH; Ng SH; Ng PS; Ma NL; Lakshminarayana SB; Herve M; Barnes SW; Yu W; Kuhen K; Blasco F; Beer D; Walker JR; Tonge PJ; Glynne R; Smith PW; Diagana TT Direct inhibitors of InhA are active against Mycobacterium tuberculosis Sci Transl Med, 2015, 7, 269ra263. DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Banerjee A; Dubnau E; Quemard A; Balasubramanian V; Um KS; Wilson T; Collins D; de Lisle G; Jacobs WR Jr. inhA, a gene encoding a target for isoniazid and ethionamide in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Science, 1994, 263, 227–230. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Quemard A; Sacchettini JC; Dessen A; Vilcheze C; Bittman R; Jacobs WR Jr.; Blanchard JS Enzymatic characterization of the target for isoniazid in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Biochemistry, 1995, 34, 8235–8241. DOI: 10.1021/bi00026a004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Encinas L; O'Keefe H; Neu M; Remuinan MJ; Patel AM; Guardia A; Davie CP; Perez-Macias N; Yang H; Convery MA; Messer JA; Perez-Herran E; Centrella PA; Alvarez-Gomez D; Clark MA; Huss S; O'Donovan GK; Ortega-Muro F; McDowell W; Castaneda P; Arico-Muendel CC; Pajk S; Rullas J; Angulo-Barturen I; Alvarez-Ruiz E; Mendoza-Losana A; Ballell Pages L; Castro-Pichel J; Evindar G Encoded library technology as a source of hits for the discovery and lead optimization of a potent and selective class of bactericidal direct inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis InhA J Med Chem, 2014, 57, 1276–1288. DOI: 10.1021/jm401326j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Sink R; Sosic I; Zivec M; Fernandez-Menendez R; Turk S; Pajk S; Alvarez-Gomez D; Lopez-Roman EM; Gonzales-Cortez C; Rullas-Triconado J; Angulo-Barturen I; Barros D; Ballell-Pages L; Young RJ; Encinas L; Gobec S Design, synthesis, and evaluation of new thiadiazole-based direct inhibitors of enoyl acyl carrier protein reductase (InhA) for the treatment of tuberculosis J Med Chem, 2015, 58, 613–624. DOI: 10.1021/jm501029r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Martinez-Hoyos M; Perez-Herran E; Gulten G; Encinas L; Alvarez-Gomez D; Alvarez E; Ferrer-Bazaga S; Garcia-Perez A; Ortega F; Angulo-Barturen I; Rullas-Trincado J; Blanco Ruano D; Torres P; Castaneda P; Huss S; Fernandez Menendez R; Gonzalez Del Valle S; Ballell L; Barros D; Modha S; Dhar N; Signorino-Gelo F; McKinney JD; Garcia-Bustos JF; Lavandera JL; Sacchettini JC; Jimenez MS; Martin-Casabona N; Castro-Pichel J; Mendoza-Losana A Antitubercular drugs for an old target: GSK693 as a promising InhA direct inhibitor EBioMedicine, 2016, 8, 291–301. DOI: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Parikh SL; Xiao G; Tonge PJ Inhibition of InhA, the enoyl reductase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, by triclosan and isoniazid Biochemistry, 2000, 39, 7645–7650. DOI: 10.1021/bi0008940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Eltschkner S; Kehrein J; Le TA; Davoodi S; Merget B; Basak S; Weinrich JD; Schiebel J; Tonge PJ; Engels B; Sotriffer C; Kisker C A Long Residence Time Enoyl-Reductase Inhibitor Explores an Extended Binding Region with Isoenzyme-Dependent Tautomer Adaptation and Differential Substrate-Binding Loop Closure ACS Infect Dis, 2021, 7, 746–758. DOI: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Rawat R; Whitty A; Tonge PJ The isoniazid-NAD adduct is a slow, tight-binding inhibitor of InhA, the Mycobacterium tuberculosis enoyl reductase: adduct affinity and drug resistance Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2003, 100, 13881–13886. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2235848100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Pan P; Knudson SE; Bommineni GR; Li HJ; Lai CT; Liu N; Garcia-Diaz M; Simmerling C; Patil SS; Slayden RA; Tonge PJ Time-dependent diaryl ether inhibitors of InhA: structure-activity relationship studies of enzyme inhibition, antibacterial activity, and in vivo efficacy ChemMedChem, 2014, 9, 776–791. DOI: 10.1002/cmdc.201300429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Luckner SR; Liu N; am Ende CW; Tonge PJ; Kisker C A slow, tight binding inhibitor of InhA, the enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis J Biol Chem, 2010, 285, 14330–14337. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M109.090373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Li HJ; Lai CT; Pan P; Yu W; Liu N; Bommineni GR; Garcia-Diaz M; Simmerling C; Tonge PJ A structural and energetic model for the slow-onset inhibition of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis enoyl-ACP reductase InhA ACS Chem Biol, 2014, 9, 986–993. DOI: 10.1021/cb400896g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Lai CT; Li HJ; Yu W; Shah S; Bommineni GR; Perrone V; Garcia-Diaz M; Tonge PJ; Simmerling C Rational modulation of the induced-fit conformational change for slow-onset inhibition in Mycobacterium tuberculosis InhA Biochemistry, 2015, 54, 4683–4691. DOI: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Spagnuolo LA; Eltschkner S; Yu W; Daryaee F; Davoodi S; Knudson SE; Allen EK; Merino J; Pschibul A; Moree B; Thivalapill N; Truglio JJ; Salafsky J; Slayden RA; Kisker C; Tonge PJ Evaluating the contribution of transition-state destabilization to changes in the residence time of triazole-based InhA inhibitors J Am Chem Soc, 2017, 139, 3417–3429. DOI: 10.1021/jacs.6b11148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Rozwarski DA; Vilcheze C; Sugantino M; Bittman R; Sacchettini JC Crystal structure of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis enoyl-ACP reductase, InhA, in complex with NAD+ and a C16 fatty acyl substrate J Biol Chem, 1999, 274, 15582–15589. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Sivaraman S; Sullivan TJ; Johnson F; Novichenok P; Cui G; Simmerling C; Tonge PJ Inhibition of the bacterial enoyl reductase FabI by triclosan: a structure-reactivity analysis of FabI inhibition by triclosan analogues J Med Chem, 2004, 47, 509–518. DOI: 10.1021/jm030182i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).PyMOL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.5 Schrödinger, LLC, 2015. DOI: [Google Scholar]

- (24).Gil AA; Haigney A; Laptenok SP; Brust R; Lukacs A; Iuliano JN; Jeng J; Melief EH; Zhao RK; Yoon E; Clark IP; Towrie M; Greetham GM; Ng A; Truglio JJ; French JB; Meech SR; Tonge PJ Mechanism of the AppABLUF Photocycle Probed by Site-Specific Incorporation of Fluorotyrosine Residues: Effect of the Y21 pKa on the Forward and Reverse Ground-State Reactions J Am Chem Soc, 2016, 138, 926–935. DOI: 10.1021/jacs.5b11115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Minnihan EC; Young DD; Schultz PG; Stubbe J Incorporation of Fluorotyrosines into Ribonucleotide Reductase Using an Evolved, Polyspecific Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase J Am Chem Soc, 2011, 133, 15942–15945. DOI: 10.1021/ja207719f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Basso LA; Zheng R; Musser JM; Jacobs WR Jr.; Blanchard JS Mechanisms of isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: enzymatic characterization of enoyl reductase mutants identified in isoniazid-resistant clinical isolates J Infect Dis, 1998, 178, 769–775. DOI: 10.1086/515362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Morrison JF; Walsh CT The behavior and significance of slow-binding enzyme inhibitors Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol, 1988, 61, 201–301. DOI: 10.1002/9780470123072.ch5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Heath RJ; Rubin JR; Holland DR; Zhang E; Snow ME; Rock CO Mechanism of triclosan inhibition of bacterial fatty acid synthesis J Biol Chem, 1999, 274, 11110–11114. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Jörnvall H; Persson B; Krook M; Atrian S; Gonzàlez-Duarte R; Jeffery J; Ghosh D Short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases (SDR) Biochemistry, 1995, 34, 6003–6013. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Kallberg Y; Oppermann U; Jornvall H; Persson B Short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases (SDRs) Eur. J. Biochem, 2002, 269, 4409–4417. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Filling C; Berndt KD; Benach J; Knapp S; Prozorovski T; Nordling E; Ladenstein R; Jornvall H; Oppermann U Critical residues for structure and catalysis in short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases J Biol Chem, 2002, 277, 25677–25684. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M202160200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kavanagh KL; Jornvall H; Persson B; Oppermann U Medium- and short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase gene and protein families : the SDR superfamily: functional and structural diversity within a family of metabolic and regulatory enzymes Cell Mol Life Sci, 2008, 65, 3895–3906. DOI: 10.1007/s00018-008-8588-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Oppermann UC; Filling C; Berndt KD; Persson B; Benach J; Ladenstein R; Jornvall H Active site directed mutagenesis of 3 beta/17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase establishes differential effects on short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase reactions Biochemistry, 1997, 36, 34–40. DOI: 10.1021/bi961803v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Liu Y; Thoden JB; Kim J; Berger E; Gulick AM; Ruzicka FJ; Holden HM; Frey PA Mechanistic roles of tyrosine 149 and serine 124 in UDP-galactose 4-epimerase from Escherichia coli Biochemistry, 1997, 36, 10675–10684. DOI: 10.1021/bi970430a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Thoden JB; Wohlers TM; Fridovich-Keil JL; Holden HM Crystallographic evidence for Tyr 157 functioning as the active site base in human UDP-galactose 4-epimerase Biochemistry, 2000, 39, 5691–5701. DOI: 10.1021/bi000215l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Koumanov A; Benach J; Atrian S; Gonzalez-Duarte R; Karshikoff A; Ladenstein R The catalytic mechanism of Drosophila alcohol dehydrogenase: evidence for a proton relay modulated by the coupled ionization of the active site Lysine/Tyrosine pair and a NAD+ ribose OH switch Proteins, 2003, 51, 289–298. DOI: 10.1002/prot.10354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Tanaka N; Nonaka T; Tanabe T; Yoshimoto T; Tsuru D; Mitsui Y Crystal structures of the binary and ternary complexes of 7 alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from Escherichia coli Biochemistry, 1996, 35, 7715–7730. DOI: 10.1021/bi951904d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Rafi S; Novichenok P; Kolappan S; Zhang X; Stratton CF; Rawat R; Kisker C; Simmerling C; Tonge PJ Structure of acyl carrier protein bound to FabI, the FASII enoyl reductase from Escherichia coli J Biol Chem, 2006, 281, 39285–39293. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M608758200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Stewart MJ; Parikh S; Xiao G; Tonge PJ; Kisker C Structural basis and mechanism of enoyl reductase inhibition by triclosan J Mol Biol, 1999, 290, 859–865. DOI: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Tu X; Hubbard PA; Kim JJ; Schulz H Two distinct proton donors at the active site of Escherichia coli 2,4-dienoyl-CoA reductase are responsible for the formation of different products Biochemistry, 2008, 47, 1167–1175. DOI: 10.1021/bi701235t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Lu H; Tonge PJ Mechanism and inhibition of the FabV enoyl-ACP reductase from Burkholderia mallei Biochemistry, 2010, 49, 1281–1289. DOI: 10.1021/bi902001a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Vogeli B; Rosenthal RG; Stoffel GMM; Wagner T; Kiefer P; Cortina NS; Shima S; Erb TJ InhA, the enoyl-thioester reductase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis forms a covalent adduct during catalysis J Biol Chem, 2018, 293, 17200–17207. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.005405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Fillgrove KL; Anderson VE The mechanism of dienoyl-CoA reduction by 2,4-dienoyl-CoA reductase is stepwise: Observation of a dienolate intermediate Biochemistry, 2001, 40, 12412–12421. DOI: DOI 10.1021/bi0111606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Natarajan A; Schwans JP; Herschlag D Using unnatural amino acids to probe the energetics of oxyanion hole hydrogen bonds in the ketosteroid isomerase active site J Am Chem Soc, 2014, 136, 7643–7654. DOI: 10.1021/ja413174b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.