Abstract

NP10679 is a context-dependent and subunit-selective negative allosteric modulator of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. It is a more potent inhibitor of GluN2B-containing NMDA receptors at the acidic levels of extracellular pH (e.g. 6.9) found in the penumbral regions associated with cerebral ischemia than at physiological pH. This property allows NP10679 to act selectively in ischemic tissue while minimizing the non-selective blockade of NMDA receptors in healthy brain, thereby reducing on-target adverse effects. We report the results of a first-in-human pharmacokinetic and safety Phase 1 clinical trial in healthy volunteers receiving single or multiple doses of NP10679 (NCT04007263). We found that NP10679 was well-tolerated and with a half-life of 20 h, which is amenable to once per day dosing. The only notable side effect in this clinical trial was modest somnolence at higher doses, atypical in that the subject could easily be aroused. The overall results suggest that NP10679 is a candidate for further development for use in acute brain injury, such as ischemic stroke or aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH), as well as for use in neuropsychiatric indications.

Keywords: subarachnoid hemorrhage, neuroprotection, ischemia, NMDA receptor

Introduction

Cerebral ischemia is a central component of acute brain injuries such as stroke, traumatic brain injury, and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and may lead to significant subsequent neurological and cognitive deficits. Downstream mechanisms that are proposed to contribute to secondary tissue injury after ischemia-related neuronal death include neuroinflammation, microglial activation, oxidative stress1 and excess activation of receptors recognizing glutamic acid due to the accumulation of this amino acid neurotransmitter in the extracellular space2,3.

Previous neuroprotectant compounds have demonstrated promise but failed to achieve a tolerable safety profile or demonstrate significant efficacy in clinical investigations of stroke, spontaneous brain hemorrhage, or traumatic brain injury (TBI)4,5. Proposed reasons for the clinical failures include delay in initiating treatment after insult6,7, patient heterogeneity, complex endpoints, dose-limiting on-target effects, and a failure to reach efficacious dose levels at the site of injury5,8–11. Considering the potential reasons for past failures to identify an effective pharmacotherapy for ischemic brain injury, two elements appear necessary to provide the best chance to observe a meaningful positive signal in ameliorating the clinical manifestations of ischemic injury: a clinical plan that addresses pitfalls suggested from previous trials and a safe and effective neuroprotectant to implement that plan.

A major contributor to negative findings reported in stroke and TBI trials was the delay in time to treatment12. This latency to effective treatment would be reduced in clinical trials testing neuroprotectants in an indication such as aneurysmal SAH (aSAH), which is associated with the delayed onset of cerebral ischemia. Thus, this indication lends itself to early and prophylactic administration of a neuroprotectant. Referred to as delayed cerebral ischemia, the ischemia in aSAH appears to be driven by vascular events that occur 3–14 days after an aneurysmal hemorrhage. Dosing near the time of surgical repair of aneurysm would allow a neuroprotectant to be present in the brain prior to and essentially serve as prophylactic to a post-SAH ischemia. Furthermore, by dosing for 14 days after vessel rupture, the entire period of greatest ischemic risk would be covered with the neuroprotectant therapy. Additionally, by using imaging techniques such as MRI, patient heterogeneity could be reduced.

While aSAH accounts for only 3–5 percent of the overall stroke population, afflicted individuals tend to be younger and often have poorer long-term outcomes than do those with ischemic stroke13,14. These factors lead to the loss of productive years in the general population similar to that of cerebral infarction, the most common form of stroke15. Despite surgical advances such as surgical clipping and endovascular coiling to address the initial and subsequent bleeds, aSAH is associated with a significant risk of delayed cerebral ischemia and related events (e.g., vasospasm, infarct and diffuse microvascular disease)16. The underlying pathological mechanisms of delayed cerebral ischemia are still unclear and the calcium channel blocker nimodipine, introduced in 1988, remains the only approved pharmaceutical intervention to improve long term functional outcomes after aSAH. The efficacy of nimodipine across a number of clinical studies has been inconsistent. While meta analyses of nimodipine clinical studies indicate improved outcome17,18, the drug provides only 30–40% rescue from neurological and cognitive deficits, rendering pharmacological strategies to reduce delayed cerebral ischemia following aSAH an important unmet clinical need19.

A considerable amount of preclinical evidence demonstrates that prolonged exposure of neurons to extracellular glutamate released during cerebral ischemia leads to cell death that is largely mediated by calcium entry through N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs).2,3,20–22 NMDARs are composed of two GluN1 subunits and two GluN2 subunits, of which there are four subtypes (GluN2A-D). Blockade of NMDA receptors has been demonstrated to be neuroprotective in hundreds of preclinical studies in vivo (see Yuan et al., 2015)23, leading to clinical trials of this strategy in a number of disorders. However, the dose-limiting side effects associated with nonselective NMDA receptor blockade have prevented successful translation into clinical trials. For the first two generations of NMDA antagonists (i.e. non-selective channel blockers and competitive glutamate site antagonists), the level of occupancy needed for neuroprotection altered cardiovascular function and significantly disrupted cognition leading to dose-limiting side effects.9,24,25

To reduce the side effects associated with early NMDA inhibitors, modes of inhibition that provide selectivity for NMDAR subtypes were explored as early as the late 1980’s. Non-competitive inhibitors, such as ifenprodil, were identified that do not bind at either agonist binding sites or to the channel pore26–28, and are highly selective for GluN2B-containing NMDARs5,29. Ifenprodil and related GluN2B-selective inhibitors are better tolerated in animals and humans than previous NMDAR inhibitors, including high affinity channel blockers and competitive antagonists30. However, limited efficacy and/or unfavorable safety margins due to untoward cardiovascular or CNS effects, particularly at high doses, prevented late-stage clinical development of GluN2B-NMDAR inhibitors such as traxoprodil (CP-101,606)31, MK-0657 (CERC-301)32 and EVT-10133. Although promising in a study of TBI patients34, ketamine-like dissociative effects were noted with CP-101,606 in a study in depressed individuals31. Selective GluN2B-NMDAR inhibitors with properties that should further reduce on-target side effects have been discovered by NeurOp Inc. These compounds have increasing potency as extracellular pH is incrementally lowered, which may lead to increased selectivity in the ischemic brain areas associated with tissue acidosis, such as occur in aSAH23. This strategy has the potential for reducing NMDAR-related side effects in humans. In particular, NP10679 (Figure 1A)35 is a potent, context-dependent, GluN2B-selective inhibitor of the NMDAR that is being developed by NeurOp Inc. with the aim of identifying agents that ameliorate neurological deficits resulting from brain ischemic events such as those associated with stroke, head trauma, and SAH.

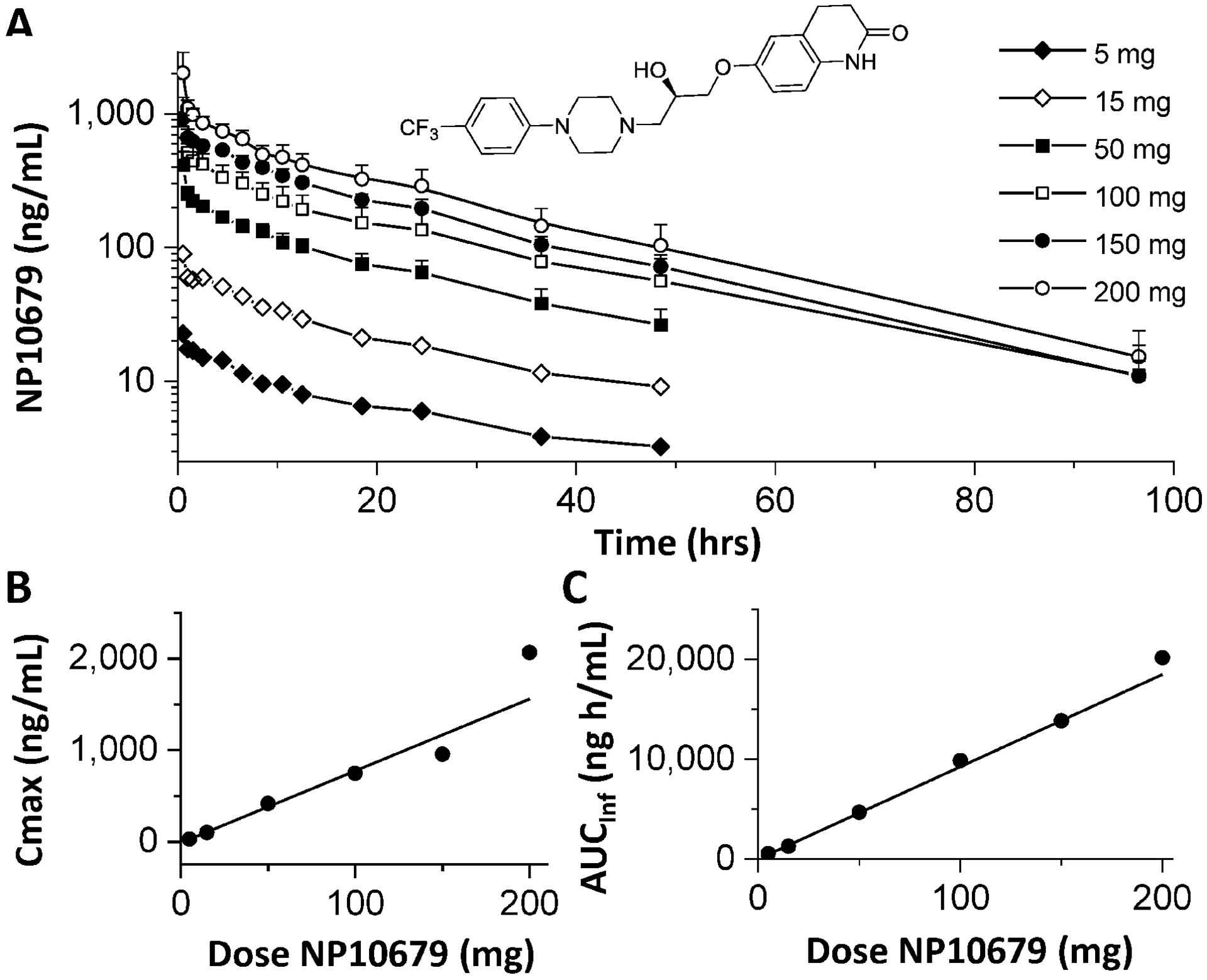

Figure 1:

Plasma exposure of NP10679 after a single IV dose in human subjects. (A) Plasma collection and quantification were performed as described in the Methods. Data presented as ng/mL of NP10679 represent the mean and SD of 6 subjects per dose except for 150 mg, which is the mean of 5 subjects. The inset shows the structure of NP10679, ((R)-6-(2-Hydroxy-3-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)piperazin-1-yl)propoxy)-3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-one). (B) Cmax (mean ± SD) as a function of dose (R2=0.919). (C) AUCinf is plotted against the dose, confirming dose linearity (R2=0.996).

In vitro, NP10679 has >100,000 fold selectivity for GluN2B over the other GluN2 subtypes of the NMDAR and is approximately 6-fold more potent at blocking the receptor at pH 6.9 than at pH 7.6. The in vitro metabolic stability profile of NP10679 is similar in mice, rats, dogs, and humans, with similar hepatic microsomal half lives greater than 2 hours in all species (unpublished). NP10679 is substantially bound to plasma proteins with 97.4 to 99.0% bound in the four species (unpublished). The compound readily distributes into brain tissues in mice suggested by the ratio of brain to plasma levels observed at steady state (1.3–2.6), and is orally available (F%=76% in mouse). NP10679 is a weak (IC50 > 10 μM), reversable inhibitor at multiple human liver CYP enzymes studied to date and does not lead to significant time-dependent inhibition of CYP3A (unpublished data and Ref35). These data suggest that the potential for pharmacokinetic-based drug-drug interactions between NP10679 and co-administered drugs is low. The compound is effective in reducing infarct volume in the murine MCAO model of ischemic brain injury when administered 15 minutes prior to occlusion35. The minimum effective dose of NP10679 in the MCAO model is 2 mg/kg IP.

NP10679 lacks demonstrable activity at over 40 CNS targets but does act as a histamine H1 antagonist (IC50 73 nM), and in pre-clinical models leads to somnolence at doses above those necessary to achieve efficacy35. NP10679 also inhibits the hERG channel with an IC50 value (620 nM) approximately 30-times higher than its activity to inhibit GluN2B-containing NMDA receptors35. This is likely reflected in the activity of the compound to only minimally prolong QT interval in dogs at doses several fold higher than those we predict will be associated with efficacy in rodent models (unpublished). The off-target activity, particularly in the context of the safety data collected, appears to pose no serious issues that would limit the clinical development of NP10679. In repeat-dose toxicity studies of up to 14 days duration in rats and dogs, the only adverse effect directly related to IV administration of NP10679 was sedation, which was the dose-limiting effect in both species. In total, the data from Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) rat and dog safety studies indicate a good safety margin when viewed in relation to plasma levels in the mouse when administered at doses leading to efficacy in the middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model35.

This report describes observations made from the initial phase 1 human clinical trials of NP10679. Results from both single ascending dose (SAD) and multiple ascending dose (MAD) studies are presented. The compound was found to be safe and has a pharmacokinetic profile in humans that lends itself to once per day dosing. The studies presented support further development of NP10679 in brain ischemic disorders such as aSAH.

Methods

These protocols as well as subject informed consent packages were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board (IRB) for the study, IntegReview IRB, Austin TX; the clinical research organization (CRO) for both studies was Pharmaron CPC, Baltimore, Maryland. All subjects were informed of the nature and purpose of the study, and their written informed consent was obtained before any study-related procedures were performed. Studies were conducted in accordance with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Tripartite Guidance on Good Clinical Practice. Protocols for both the single ascending dose (SAD) and multiple ascending dose (MAD) studies were reviewed and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration under an investigational new drug application.

Drug substance and product

Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) quality active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) of NP10679 for the manufacture of drug product to support Phase I clinical development was synthesized through a contract with DavosPharma (Saddle River, NJ). The molecular formula of NP10679 (6-{R-2-Hydroxy-3-[4-(4-trifluromethyl-phenyl)-piperazin-1-yl]propoxy}−3,4-dihydro-1H-2-one, structure shown in Figure, 1A) is C23H26F3N3O (MW = 449.5 g/mol).

Because NP10679 was to be administered by IV infusion in the SAD and MAD studies, API was formulated into clinical drug product for constitution into the IV solution at the clinical site. The manufacturing of drug product was performed by University of Iowa, Pharmaceuticals (UI-P) according to procedures established for the generation of lyophilized product. To formulate the drug product, API was solubilized in a vehicle consisting of 25% hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin (HPBCD) solution in 50 mM potassium phosphate monobasic buffer (pH 6.0) to a concentration of 5 mg/ml. This solution was then filter sterilized and lyophilized into sterile vials each containing 50 mg API. Subsequent dilutions of the appropriate quantity of the formulated material for each dose was made with 2.5% HPBCD in 0.9% saline up to 75ml for IV infusion. Sterility of the vial contents was confirmed.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Healthy male and female subjects aged 18 to 55 who were capable of providing consent and able to adhere to the visit schedule and other protocol requirements were eligible for the studies. If sexually active and of child-bearing potential (both men and women), volunteers were required to agree to use two forms of contraceptive methods (including one barrier) for the duration of the study.

Exclusion criteria were inadequate peripheral forearm vein access, pregnancy or lactation, use of nicotine-containing products during the study, current or recent (within 12 months) history of alcohol or drug abuse, recent blood donation within 90 days, and previous participation in a clinical trial withing 90 days. Subjects with excessive somnolence and those who had used medications or agents that might cause drowsiness within 7 days were also excluded. Volunteers with significant medical or psychiatric illness by history, examination, or clinical laboratory testing that would influence study results or preclude informed consent and study compliance were also excluded.

Clinical Study Designs

The SAD study (NP10679–101) was a single center, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, single dose, dose escalation trial to investigate the safety, tolerability and PK of NP10679 in healthy adult volunteers in six escalating dosing cohorts. The primary objective of the study was to assess the safety, tolerability and PK of a single dose of NP10679 when delivered by intravenous (IV) infusion in comparison to placebo. Secondary objectives were to obtain a maximum tolerated dose of NP10679 in healthy adult volunteers and to establish a safe starting dose for the MAD study (NP10679–102).

The study consisted of a 30-day screening period, Day 1 (single IV infusion NP10679 or placebo, as randomized), Day 2 in clinic/overnight assessments and Day 3 assessments. Subjects checked into the clinic on Day 1 and remained in the clinic through the 48 h post-dose blood draw on Day 3, after which time they were discharged. Subjects returned to the clinic for a follow-up visit at Day 8 after discharge.

There were six dosing cohorts studied in NP10679–101. Each cohort consisted of 8 subjects. Six subjects of each cohort were administered NP10679 and two subjects received placebo. Doses were evaluated sequentially before escalating to the next dose level. Doses included in the study were 5, 15, 50, 100, 150 and 200 mg. Drug and placebo were administered by IV infusion in 75 ml of dosing vehicle over 30 minutes. A sentinel dosing, adaptive design approach was used for all cohorts, in which the first 2 subjects (1 active, 1 placebo) were dosed on Day 1 and observed for 48 h or until sufficient time had elapsed to review safety. If the safety committee (at a minimum, the Principal Investigator (PI) and Medical Monitor (a subject matter MD independent from the conduct of the study) agreed that it was safe to proceed, the remaining 6 subjects (5 active, 1 placebo) were dosed in that cohort at the same dose level. Safety/tolerability data as well as available PK data were reviewed prior to dosing in the next cohort of subjects. Acceptable results of the interim safety/tolerability review triggered enrollment into the next dosing cohort.

The purpose of the MAD study was to evaluate safety and pharmacokinetics of NP10679 upon repeated dosing until steady state was reached. Based on results from the SAD study, it was determined that 5 days of once daily dosing would lead to steady state. Subjects in the MAD study (NP10679–102) were treated in the same way as those in NP10679–101. The study consisted of a 30-day screening period, dosing Days 1 through 5 (single 75 ml IV infusions of NP10679 or placebo over 30 min, as randomized), Day 6 in clinic/overnight assessments and Day 7 assessments prior to discharge. Subjects checked into the clinic on Day 1 and remained in the clinic through the 48 h post-dose blood draw on Day 7, after which time they were discharged. Subjects returned to the clinic for a follow-up visit at Day 9. Three dosing cohorts of 8 subjects each (6 drug and 2 placebo) were recruited and dosing decisions were made as in NP10679–101. Dose levels included 25, 50 and 100 mg per day.

Safety evaluations

SFor the SAD study, safety and ttolerability parameters were assessed according to the protocol schedule of assessments and included assessment of treatment-emergent adverse events based on physical examinations, infusion site examinations, laboratory findings, neuropsychiatric assessments, vital signs and subject reported tolerability. End points also include hematology, chemistry, urinalysis and 12-lead ECG. Since NP10679 is an NMDAR modulator and such compounds have a history of leading to neurobehavioral effects including cognitive and dissociative effects, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE), the Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R), the 7-item General Anxiety Disorders scale (GAD-7) and the Clinician-Administered Dissociative States Scale (CADSS) were included as standard assessments. There were no detectable changes in mean values for these assessments. NP10679 also is a histamine H1 inhibitor and as such might lead to drowsiness, therefore the Modified Observer’s Assessment of Alertness/Sedation (MOAA/S) and the Bond-Lader VAS sleepiness scale were also added.. Parameters used in the MAD study mirrored those used in the SAD. However, it was found in the SAD study that the MOAA/S and Bond-Lader scales were not helpful in capturing the features of somnolence beyond routine clinical observation and those two scales were not used in the MAD study.

All subjects who had at least one dose of the trial medication and a safety follow-up, whether withdrawn prematurely or not, were included in the safety analysis. Data were summarized by reporting the number and percentage of subjects in each category for categorical and ordinal measures, and mean, SD, median, and range for continuous measures. Safety endpoint included a summary of treatment-emergent clinical and laboratory-based adverse events and their severity. All adverse events were coded by System Organ Class and Preferred Term according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA). The treatment-emergent adverse events were tabulated by dose level, System Organ Class and Preferred Term.

Pharmacokinetic measurements

For the SAD study, blood was drawn via a vein opposite the infusion arm (if possible) for determination of systemic NP10679 levels at pre-dose and at end of infusion (30 min ± 5 min), and 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48, 96 h post-dose. Collection tubes containing K2EDTA were used to collect 5 mL of whole blood sample at each time point. Immediately after collection, tubes were inverted to mix the anticoagulant with the blood sample. Tubes were then centrifuged at a speed of approximately 3000 g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Within 5 minutes of centrifugation the plasma fraction was transferred into two equal aliquots (1.25 mL each) into 2 mL cryovials and then frozen and stored at −70°C (±10°C) until shipment. For the MAD study, blood was also drawn via a vein opposite the infusion arm (if possible) for determination of systemic NP10679 levels at pre-dose and at end of infusion (30 min ± 5 min), and at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 18 h on Days 1–5 and at 24, 36, 48 and 96 h following the final dose on day 5.

Bioanalytical methods were developed and validated at TDM Pharmaceutical Research, Inc to quantitate NP10679 for the SAD study. Standards, controls and test plasma samples containing NP10679 were quantified by a validated LC-MS/MS assay(s) subsequent to protein precipitation with a detection range of 1–1000 ng/mL in a 50 μl volume. A close structural analog of NP10679 (NP10767) was used as the internal standard (IS). Each 50 μL aliquot of quality control sample, standard, or plasma sample was mixed with 250 μl of acetonitrile and 50 μL of working IS solution (50 ng/mL in methanol). The sample was vortexed and centrifuged at 3000 rpm, and 150 μL of the resulting supernatant was transferred to autosampler vials for injection into an LC-MS/MS system for analysis. Chromatographic retention of NP10679 and the IS was obtained on an Agilent Poroshell 120 EC-C18, 2.1 × 30 mm, 2.7 μm column (Santa Clara, California) under gradient conditions with a flow rate of 0.3 mL/minute (mobile phase A was 0.1% formic acid in water, mobile phase B was 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile). Analytes were detected by multiple reaction monitoring using an MDS Sciex API 4000 mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA) in positive MRM mode (dwell time 100 ms, DP 11 Volts, EP 10 Volts, CE 43 Volts, CXP 20 Volts). The analyte NP10679 had an m/z of 450.2 with transition to 243.2. The IS had m/z of 464.2 and transitioned to 257.2. Plasma concentrations from the resulting LC-MS/MS data were calculated using a 6 point calibration curve constructed from known concentrations of NP10679 in human plasma prepared fresh daily. The lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) for NP10679 was 2 ng/mL in diluted plasma. The intra-run precision (coefficient of variation) was 1.3 to 9.7% for NP10679, and the inter-run precision was 1.5 to 10.0%. Mean absolute recovery was independent of concentration (94.2–106.4%). The validation consisted of at least three consecutive assay runs for precision and accuracy, each including blanks, duplicate standard curves, and six replicates of QCs at each concentration level.

The bioanalytical methods described above were adapted by Pharmaron ABS for the MAD study, with the following modifications. Each 50 μL aliquot of quality control sample, standard, or plasma sample was mixed with 25 μL of working IS solution (500 ng/mL in 5% acetonitrile in water) followed by addition of 500 μl of 50:50 acetonitrile:methanol. The sample was vortexed and centrifuged at 4800 × g, and 50 μL of the resulting supernatant mixed with 100 μL of mobile phase A was transferred to autosampler vials for injection into an LC-MS/MS system for analysis (Sciex 5500) under electrospray positive polarity MRM mode. The IS was deuterated NP10679-d8 with m/z of 458.2 and transitioned to 251.2. The intra-run precision (coefficient of variation) was 1.1 to 4.9% for NP10679, and the inter-run precision was 2.7 to 5.3%. Recovery was between 73–97% for NP10679 and 105% for the IS.

Descriptive pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated based on the plasma concentrations of NP10679. The pharmacokinetic analysis was performed based on a non-compartmental analysis36 using MS Excel® (Seattle, WA).

Results

Forty-eight subjects were enrolled (Supplemental Table S1a) into the seven cohorts of the NP10679–101 study. All subjects completed the study protocol, with the exception of one subject who left the study voluntarily due to personal reasons not related to the study. The median age for this study was 33.5 years (range 22–52 years). There were 30 males and 18 women enrolled into the study. Most subjects were Black (35) followed by White (13: 10 non-Hispanic and 3 Hispanic), and 1 patient was Asian. The NP10679–102 MAD study enrolled (Supplemental Table S1b) 24 subjects into its 4 cohorts. The median age for this study was 44.5 years (range 20–54 years). There were 15 males and 9 women enrolled into the study. As in the SAD study, most subjects were Black (15) followed by White (8) and Asian (1).

Supplemental Table S2 summarizes the treatment emergent adverse events (TEAEs) by organ class and dose for the SAD study NP10679–101. The most common treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE) was somnolence, which appeared to be dose dependent (Supplemental Table S3). The Modified Observer’s Assessment of Alertness / Sedation Scale is scored from 0 to 5 with level 5 representing the lowest level of sedation. At level 5, a subject readily responds to normal spoken tones, level 4 indicates a lethargic response to voice and level 3 requires a louder voice to elicit a response. Scores below 3 require increasing levels of physical stimuli to arouse subjects. NP10679 elicited moderate effects on the MOAA/S at higher dose levels. One of 6 subjects at doses of 5 and 15 mg, and 5 of 6 subjects at doses of 50 mg - 200 mg presented with somnolence. Two subjects in each of the 100 mg and 150 mg cohorts reached a transient level 3 score on the MOAA/S. However, no subject in the highest dose group (200 mg) achieved this score. There were also moderate increases in the Bond-Lader VAS scale starting at the 50 mg dose and continuing through to the 200 mg group. The somnolence observed in the study was viewed by the attending physician to be phenomenologically different from that observed with classic sedative hypnotics, which reduced confidence in the tools used to score it. Even at the highest dose tested, when subjects were stimulated, they quickly oriented to their environment within seconds, and were able to perform relatively complex cognitive tasks such as the Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST). NP10679 does not have activity at GABAergic receptors35, but does have some action at H1 histamine receptors. However, the somnolence observed with NP10679 was not accompanied by the impaired cognitive performance observed with some H1 blockers37.

TEAEs of dizziness, headache, and tremor were noted in 1–2 subjects, and were not deemed to impact subject safety. Conjunctival and scleral hyperemia occurred in 3 of 6 subjects at the 200 mg dose, and may be related to a non-clinically significant lower blood pressure (both systolic and diastolic) observed at the highest two doses. However, there were no clinically significant changes in vital signs or ECGs in the study. The increases in QTc intervals or hypertension observed with previous GluN2B inhibitors (Lengyel et al., 2004, Addy et al., 2009)32,38 were not observed in the NP10679–101 SAD study.

No serious adverse events (SAEs) were observed in either the SAD or MAD studies. There was no evidence of dissociative symptoms or cognitive impairment related to NP10679 as assessed by the Clinician Administered Dissociative States Scale (CADSS) or the Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST) in either the SAD or MAD studies, although one subject receiving a single 150 mg dose described intrusive thoughts. Consistent with the SAD study, the most common adverse effect in the MAD study was somnolence, which was observed in 3 subjects in the both the 50 and 100 mg groups and in 3 subjects in the placebo group. There were no signs of increased somnolence upon repeat dosing. While there may have been some accommodation to the somnolence effect, since observations of this effect occurred for the most part only on the first and second day of dosing, there was not enough of a pattern to support a firm conclusion. Table 1 summarizes the treatment emergent adverse events (TEAEs) by organ class and dose for the MAD study NP10679–102.

Table 1.

NP10679–102 Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events by System Organ Class and Preferred Term

| System Organ Class Preferred Term |

NP10679 25mg (N = 6) n (%) |

NP10679 50mg (N = 6) n (%) |

NP10679 100mg (N = 6) n (%) |

Placebo (N = 6) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects with at least one TEAE | 5 (83.3%) | 3 (50.0%) | 6 (100%) | 6 (100%) |

| Nervous system disorders | 3 (50.0%) | 3 (50.0%) | 4 (66.7%) | 5 (83.3%) |

| Somnolence | 0 | 3 (50.0%) | 3 (50.0%) | 3 (50.0%) |

| Headache | 2 (33.3%) | 0 | 2 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Dysgeusia | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Syncope | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 |

| Dizziness | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7%) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 1 (16.7%) | 2 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | 3 (50.0%) |

| Fatigue | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 2 (33.3%) |

| Pain | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0 |

| Asthenia | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Peripheral swelling | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | 2 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Contusion | 2 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 1 (16.7%) |

| Head injury | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 2 (33.3%) | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 |

| Anaemia | 2 (33.3%) | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 |

| Vascular disorders | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Phlebitis | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 |

| Nausea | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 |

| Investigations | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Blood pressure diastolic decreased | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 |

| Erythema | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 |

| Eye disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7%) |

| Vision blurred | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7%) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7%) |

| Back pain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7%) |

TEAE = Treatment-emergent adverse event; N = Number of subjects in Safety Population, n = Number of subjects with event, % = n/N*100. Adverse events are coded with MedDRA version 21.1.

Subjects with multiple occurrences of adverse events in the same preferred term are counted only once within that preferred term. Subjects with multiple occurrences of adverse events in the same system organ class are counted only once within that system organ class. System organ class as well as preferred terms under system organ class are sorted in descending order of frequency in combined NP10679 group first and then Placebo.

Pharmacokinetics

In the NP10679–101 study, NP10679 plasma concentrations (see Figure 1A and Table 2) increased linearly with dose. The Cmax was approximately dose-linear, especially at doses of 100 mg or less (Figure 1B). Likewise the AUCinf was linear with dose (Figure 1C). After the infusion period, plasma concentrations declined multi-exponentially with a terminal half-life of approximately 20 hr. The total clearance ranged from 9.8 L/h to 12 L/h over the doses studied and, as expected, was approximated by dose/AUC(0-inf).When compared to the hepatic blood flow in human of 87 L/h, NP10679 cleared the body slowly at less than 12% of the hepatic blood flow. NP10679 appears to distribute extensively throughout the body with a volume of distribution of more than 221 L, equating to 4.5 times the total body water space.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic Parameters Following an Intravenous Administration in NP10679 in the Single Ascending Dose Trial (NP10679–101)

| NP10679 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 mg | 15 mg | 50 mg | 100 mg | 150 mg | 200 mg | |

| Number of Subjects | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 27 ± 15 | 99 ± 67 | 415 ± 107 | 746 ± 223 | 954 ± 370 | 2070 ± 798 |

| AUC (0–96 h) | 335 ± 46 | 1140 ± 233 | 3980 ± 544 | 9370 ± 3090 | 13600 ± 1220 | 19700 ± 4370 |

| AUC(0-inf), ng·h/mL | 553 ± 204 | 1280 ± 227 | 4680 ± 797 | 9860 ± 3220 | 13900 ± 1280 | 20200 ± 4600 |

| CL (L/hr) | 9.8 ± 2.9 | 12 ± 1.8 | 11 ± 2.2 | 11 ± 3.1 | 11 ± 0.96 | 10 ± 2.5 |

| VSS (L) | 435 ± 178 | 306 ± 41 | 255 ± 20 | 259 ± 57 | 250 ± 23 | 221 ± 34 |

| Vd, area (L), mean | 396 | 346 | 286 | 317 | 286 | 245 |

| T1/2 Elimination (h) | 28 ± 12 | 20 ± 3.5 | 18 ± 3.3 | 20 ± 1.5 | 18 ± 1.7 | 17 ± 2.8 |

Data are mean ± SD.

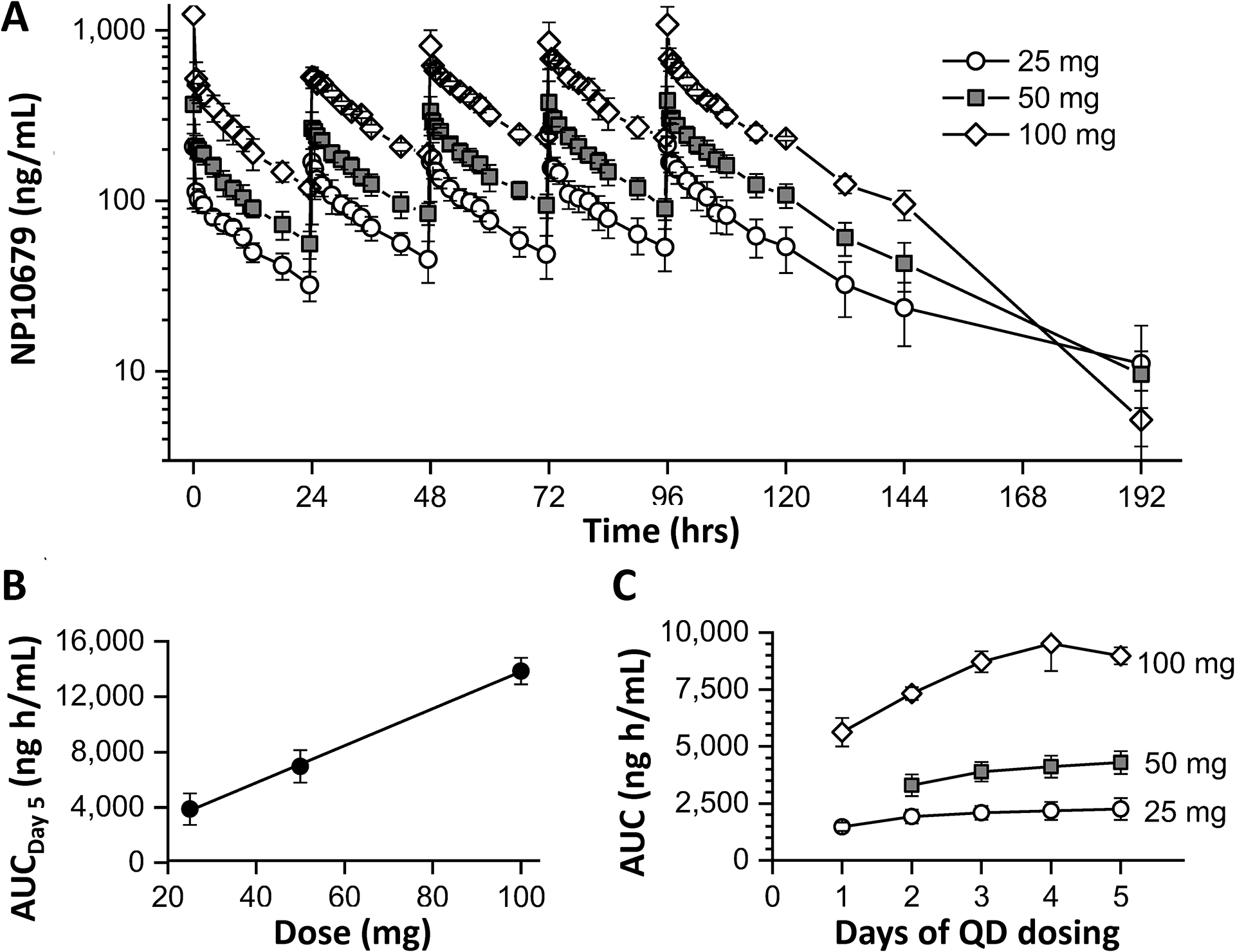

In the NP10679–102 MAD study, all subjects had quantifiable concentrations of NP10679 in plasma out to 24 hours (pre-dose time point of following day) after the first 4 doses and out to 96 hours (last PK time point) following the fifth dose (Day 5), except for one subject in the 50 mg Cohort. Mean Cmax increased with increasing dose (Figure 2A). Over the 25 to 100 mg dose range, there was a 5.9-fold and 2.7-fold increase in Cmax on Day 1 and Day 5 respectively (for pharmacokinetic parameters see Table 3). Mean AUC0–96 h determined on day 5 also increased linearly with increasing dose (Figure 2B). Thus, both Cmax and AUC were linear with increases in dose. As expected from the residual drug remaining 24 hr after each dose, there was some accumulation of drug in the plasma from days 1 through 5, which was most pronounced at the highest dose (100 mg/kg/day; Figure 2C). Terminal half-life was similar across all doses and days studied with a mean range of 15–19 hours, 16 – 21 hours, and 13 – 2 hours for 25 mg, 50 mg and 100 mg cohorts, respectively, excluding one value with the highest SD in each group, which was identified as an outlier by the Grubb’s test. Clearance at steady state was similar across the doses studied with means of 12 L/h, 12 L/h and 11 L/h for 25 mg, 50 mg and 100 mg cohorts, respectively.

Figure 2:

Plasma Exposure of NP10679 after five daily IV doses administered to human subjects. (A) Plasma collection and quantification were performed as described in Methods. Data presented as ng/mL of NP10679 represent the mean of 6 subjects per dose. (B) AUC0–96h calculated for day 5 is shown for doses administered during the multiple ascending dose trial (R2=0.999). (C) AUC0–24 h is shown for each day (0–24 hrs).

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetics Parameters of Plasma NP10679 in Multiple Ascending Dose Trial (NP10679–102)

| Treatment | Dose | Day | Cmax (ng/ml) |

Tmax (h) |

AUC 0–24 (h*ng/ml) |

AUC 0–96 (h*ng/ml) |

Cl (L/h) |

T 1/2 (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP10679 | 25 mg | 1 | 208 ±72 | 0.5±0.0 | 1470±186 | 15±3 | ||

| 2 | 211±57 | 0.9±0.8 | 1920±305 | 17±2 | ||||

| 3 | 207±35 | 0.8±0.4 | 2090±303 | 16±3 | ||||

| 4 | 250±34 | 0.5±0.0 | 2170±397 | 19±5 | ||||

| 5 | 213±26 | 0.5±0.0 | 2260±478 | 3880±1140 | 12±3 | 36±15 | ||

| 50 mg | 1 | 376±99 | 0.8±0.8 | 2650±283 | 18±4 | |||

| 2 | 276±60 | 1.0±0.4 | 3300±479 | 18±3 | ||||

| 3 | 335±73 | 0.8±0.5 | 3890±424 | 26±16 | ||||

| 4 | 389±116 | 0.8±0.5 | 4110±485 | 16±1 | ||||

| 5 | 394±72 | 0.7±0.4 | 4290±500 | 6960±1170 | 12±1 | 21±3 | ||

| 100 mg | 1 | 1240±1150 | 0.5±0.0 | 5630±625 | 22±5 | |||

| 2 | 570±29 | 0.8±0.3 | 7320±279 | 22±5 | ||||

| 3 | 812±190 | 0.5±0.0 | 8710±458 | 22±5 | ||||

| 4 | 873±236 | 0.6±0.3 | 9510±1200 | 34±28 | ||||

| 5 | 1080±295 | 0.5±0.0 | 8980±376 | 13900±962 | 11±0.5 | 13±5 |

As an internal check on the pharmacokinetic parameters derived from the MAD experiment, we verified that the calculated values of Clearance were approximated by the ratio of dose to the day 5 AUC(0–24hr), and that the 24 hr accumulation ratio at each dose (AUC(0–24hr, day 5) / AUC(0–24 hr, day 1)) was approximated by the predicted accumulation ratio calculated as 1/(1-exp(−24*beta)), where beta is the elimination rate constant determined from the terminal half-life. In this calculation we used the mean half-life at each dose, avoiding one outlier at each dose level with the largest standard deviation identified by a Grubb’s test.

Discussion

This report describes observations from the first-in-human administration of single and multiple doses of the novel pH context-dependent, GluN2B subtype-selective NMDAR inhibitor NP10679. Adverse events seen in the study were modest and primarily limited to an atypical somnolence characterized by ready arousal. Pharmacokinetic data from the SAD and MAD studies indicate exposure was linear with dose and a half-life suitable for once daily dosing.

These data support progression of NP10679 into phase 2 studies of the compound in an SAH patient population, given the potential for NP10679 to ameliorate neurological deficits arising from ischemia-induced neuronal damage during aSAH. This indication avoids a serious confounding variable of time to treatment that may have prevented positive outcomes in studies of neuroprotective agents in disorders like ischemic stroke. The strategy to be used with NP10679 is to administer the compound immediately following presentation with aSAH, to ensure that NP10679 treatment is on board throughout the time of highest risk (3–14 days post initial bleed) for delayed cerebral ischemia.

Along with issues related to timing of therapy, serious adverse events have prevented translation of previous NMDAR inhibitors for brain ischemia. These adverse events included psychotomimetic and dissociative effects, as well as off-target cardiovascular effects, such as increased blood pressure for MK-0657 (CERC-301)32 and potential hERG channel-related QT interval prolongation for CP-101,60639. In the current study, no dissociative symptoms or reduction in cognitive performance were observed in either the SAD or MAD studies nor were there clinically significant cardiovascular events at the doses tested. Somnolence was the only prevalent TEAE noted in the studies. This appeared to be dose-dependent, starting from the mid dose of 50 mg in the SAD study. The observation of somnolence did not appear to worsen over the course of 5 days of dosing in the MAD study. While there were signs of reduced somnolence upon repeat dosing, this was inconclusive based on the number of subjects and relatively short duration of dosing. It is important to note that the somnolence observed was not similar to that observed with classical sedatives. Even at the highest dose in the SAD study (200 mg), subjects were readily aroused and were able to complete complex tasks such as the digit symbol substitution test (DSST). This is relevant to the proposed use of NP10679 in the intended brain injury and SAH population, where longitudinal neurological assessments are important for care.

The focus of the current report is NP10679, a representative of a class of highly selective GluN2B NMDAR inhibitors that possess pH-context dependent increased potency. The increase in potency of this class of compound under lower pH conditions has been described in multiple publications.23,35,40,41 This selectivity should provide superior safety margins in the setting of cerebral ischemia associated with tissue acidosis.

The pharmacokinetic data from the NP10679 SAD and MAD studies indicated dose-linearity and a half-life (~ 20 hours) consistent with the compound being dosed once daily. The half-life of NP10679 compares favorably to that of nimodipine, the pharmaceutical standard of care for SAH, since nimodipine is traditionally dosed at 4 hour intervals. The Cmax and AUC0-inf values for NP10679 are in line with those that led to efficacy in the mouse MCAO model of stroke. For instance, at the 100 mg dose of NP10679 in the SAD study, the Cmax was 746 ng/ml and the AUC0-inf was 9860 h*ng/ml; at the minimum effective dose of 2 mg/kg IP in the mouse model, the Cmax was 581 ng/ml and the AUC0-inf was 5690 h* ng/ml35. The observation of somnolence in the phase 1 clinical studies of NP10679 also suggests that NP10679 is brain penetrant and interacts with a target, possibly the H1 histamine receptor, in sufficient occupancy to elicit the somnolence effect. Recent data suggest that the neuroprotective effects of NP10679 occur at lower doses than those associated with sedation in the mouse35. These observations along with that of somnolence observed in the human studies described in this report suggest that brain concentrations reached in humans with safe doses of NP10679 may be sufficient for efficacy in ischemic conditions such as the delayed cerebral ischemia associated with SAH.

Conclusions

The initial human studies NP10679–101 and NP10679–102 demonstrate that NP10679 at doses that are projected to be effective to treat the delayed cerebral ischemia associated with aSAH is safe in healthy humans. NP10679 administration to humans leads to dose linear pharmacokinetics with a half-life (20 h) that is compatible with once daily dosing. The studies are encouraging for further development of NP10679 in the setting of acute ischemic and traumatic brain injuries, including aSAH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Anupam Patgiri for helpful discussions and critical comments on the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH-NINDS R44NS071657, NIH-NINDS R35-NS111619, and NeurOp, Inc, which supplied study drug.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

DTL serves a consultant for NeuroOp. SFT is a member of the SAB for Eumentis Therapeutics, Sage Therapeutics, and Combined Brain, is a member of the Medical Advisory Board for the GRIN2B Foundation and the CureGRIN Foundation, is an advisor to GRIN Therapeutics, is co-founder of NeurOp Inc. and AgriThera Inc., and is a member of the Board of Directors of NeurOp Inc. RD is a co-founder and member of the Board of Directors for NeurOp, Inc. and Pyrefin, Inc. RZ and GWK have previously been employees of NeurOp Inc. RD and SFT are co-inventors on IP owned by Emory University and licensed to NeurOp.

Data Sharing Statement

Deidentified data described in this manuscript are available upon request when allowed, as patients were not consented to provide individual data beyond that used for the research study.

References

- 1.Weiland J, Beez A, Westermaier T, Kunze E, Sirén A-L, Lilla N. Neuroprotective Strategies in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (aSAH). Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 22(11): 5442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olney JW. Glutamate-induced retinal degeneration in neonatal mice. Electron microscopy of the acutely evolving lesion. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1969; 28(3): 455–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi DW. Calcium-mediated neurotoxicity: relationship to specific channel types and role in ischemic damage. Trends Neurosci. 1988; 11(10): 465–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipton SA. Failures and successes of NMDA receptor antagonists: molecular basis for the use of open-channel blockers like memantine in the treatment of acute and chronic neurologic insults. NeuroRx. 2004; 1(1): 101–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Traynelis SF, Wollmuth LP, McBain CJ, Menniti FS, Vance KM, Ogden KK, Hansen KB, Yuan H, Myers SJ, Dingledine R. Glutamate receptor ion channels: structure, regulation, and function. Pharmacol Rev 2010; 62(3): 405–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dirnagl U, Iadecola C, Moskowitz MA. Pathobiology of ischaemic stroke: an integrated view. Trends Neurosci. 1999; 22(9): 391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoyte L, Barber PA, Buchan AM, Hill MD. The rise and fall of NMDA antagonists for ischemic stroke. Curr Mol Med. 2004; 4(2): 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris GF, Bullock R, Marshall SB, Marmarou A, Maas A, Marshall LF. Failure of the competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist Selfotel (CGS 19755) in the treatment of severe head injury: results of two phase III clinical trials. The Selfotel Investigators.” J Neurosurg. 1999; 91(5): 737–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albers GW, Goldstein LB, Hall D, Lesko LM. Aptiganel Acute Stroke Investigators. Aptiganel hydrochloride in acute ischemic stroke: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001; 286(21):2673–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sacco RL, DeRosa JT, Haley EC Jr, Levin B, Ordronneau P, Phillips SJ, Rundek T, Snipes RG, Thompson JL. Glycine antagonist in neuroprotection for patients with acute stroke: GAIN Americas: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001; 285(13): 1719–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farin A , Marshall LF. Lessons from epidemiologic studies in clinical trials of traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2004; 89:101–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saver JL. The 2012 Feinberg Lecture: treatment swift and treatment sure. Stroke 2013; 44(1): 270–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cabral NL, Gonçalves AR, Longo AL, Moro CH, Costa G, Amaral CH, Fonseca LA, Eluf-Neto J. Incidence of stroke subtypes, prognosis and prevalence of risk factors in Joinville, Brazil: a 2 year community based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009; 80(7): 755–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sacco S, Marini C, Toni D, Olivieri L, Carolei A. Incidence and 10-year survival of intracerebral hemorrhage in a population-based registry. Stroke 2009; 40(2): 394–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feigin VL, Lawes CMM, Bennett DA, Anderson CS. Stroke epidemiology: a review of population-based studies of incidence, prevalence, and case-fatality in the late 20th century. Lancet Neurol. 2003; 2(1): 43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laskowitz DT, Kolls BJ. Neuroprotection in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2010; 41(10 Suppl): S79–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barker FG 2nd, Ogilvy CS. Efficacy of prophylactic nimodipine for delayed ischemic deficit after subarachnoid hemorrhage: a metaanalysis. J Neurosurg. 1996; 84(3):405–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu GJ, Luo J, Zhang LP, Wang ZJ, Xu LL, He GH, Zeng YJ, Wang YF. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness and safety of prophylactic use of nimodipine in patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2011; 10(7):834–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pickard JD, Murray GD, Illingworth R, Shaw MD, Teasdale GM, Foy PM, Humphrey PR, Lang DA, Nelson R, Richards P, et al. Effect of oral nimodipine on cerebral infarction and outcome after subarachnoid haemorrhage: British aneurysm nimodipine trial. BMJ. 1989; 298(6674):636–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellrén K, Lehmann A. Calcium dependency of N-methyl-D-aspartate toxicity in slices from the immature rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1989; 32(2):371–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mody I, MacDonald JF. NMDA receptor-dependent excitotoxicity: the role of intracellular Ca2+ release. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1995; 16(10):356–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wroge CM, Hogins J, Eisenman L, Mennerick S. Synaptic NMDA receptors mediate hypoxic excitotoxic death. J Neurosci. 2012; 32(19): 6732–6742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuan H, Myers SJ, Wells G, Nicholson KL, Swanger SA, Lyuboslavsky P, Tahirovic YA, Menaldino DS, Ganesh T, Wilson LJ, Liotta DC, Snyder JP, Traynelis SF. Context-dependent GluN2B-selective inhibitors of NMDA receptor function are neuroprotective with minimal side effects. Neuron 2015; 85(6): 1305–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis SM, Lees KR, Albers GW, Diener HC, Markabi S, Karlsson G, Norris J. Selfotel in acute ischemic stroke : possible neurotoxic effects of an NMDA antagonist. Stroke; 2000. 31(2):347–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muir KW, Lees KR. Excitatory amino acid antagonists for acute stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003; 2003(3):CD001244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carter C, Benavides J, Legendre P, Vincent JD, Noel F, Thuret F, Lloyd KG, Arbilla S, Zivkovic B, MacKenzie ET, et al. Ifenprodil and SL 82.0715 as cerebral anti-ischemic agents. II. Evidence for N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist properties. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988; 247(3):1222–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gotti B, Duverger D, Bertin J, Carter C, Dupont R, Frost J, Gaudilliere B, MacKenzie ET, Rousseau J, Scatton B, et al. Ifenprodil and SL 82.0715 as cerebral anti-ischemic agents. I. Evidence for efficacy in models of focal cerebral ischemia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988; 247(3): 1211–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carter CJ, Lloyd KG, Zivkovic B, Scatton B. Ifenprodil and SL 82.0715 as cerebral antiischemic agents. III. Evidence for antagonistic effects at the polyamine modulatory site within the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor complex. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990; 253(2): 475–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansen KB, Wollmuth LP, Bowie D, Furukawa H, Menniti FS, Sobolevsky AI, Swanson GT, Swanger SA, Greger IH, Nakagawa T, McBain CJ, Jayaraman V, Low CM, Dell’Acqua ML, Diamond JS, Camp CR, Perszyk RE, Yuan H, Traynelis SF. Structure, Function, and Pharmacology of Glutamate Receptor Ion Channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2021; 73(4):298–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyce S, Wyatt A, Webb JK, O’Donnell R, Mason G, Rigby M, Sirinathsinghji D, Hill RG, Rupniak NM. Selective NMDA NR2B antagonists induce antinociception without motor dysfunction: correlation with restricted localisation of NR2B subunit in dorsal horn. Neuropharmacology. 1999; 38(5): 611–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preskorn SH, Baker B, Kolluri S, Menniti FS, Krams M, Landen JW. An innovative design to establish proof of concept of the antidepressant effects of the NR2B subunit selective N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist, CP-101,606, in patients with treatment-refractory major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008; 28(6): 631–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Addy C, Assaid C, Hreniuk D, Stroh M, Xu Y, Herring WJ, Ellenbogen A, Jinnah HA, Kirby L, Leibowitz MT, Stewart RM, Tarsy D, Tetrud J, Stoch SA, Gottesdiener K, Wagner J. Single-dose administration of MK-0657, an NR2B-selective NMDA antagonist, does not result in clinically meaningful improvement in motor function in patients with moderate Parkinson’s disease. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009; 49(7): 856–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilkinson ST, Sanacora G. A new generation of antidepressants: an update on the pharmaceutical pipeline for novel and rapid-acting therapeutics in mood disorders based on glutamate/GABA neurotransmitter systems. Drug Discov Today. 2019; 24(2): 606–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yurkewicz L, Weaver J, Bullock MR, Marshall LF. The effect of the selective NMDA receptor antagonist traxoprodil in the treatment of traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2005; 22(12): 1428–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Myers SJ, Ruppa KP, Wilson LJ, Tahirovic YA, Lyuboslavsky P, Menaldino DS, Dentmon ZW, Koszalka GW, Zaczek R, Dingledine RJ, Traynelis SF, Liotta DC. A Glutamate N-Methyl-d-Aspartate (NMDA) receptor subunit 2B-selective inhibitor of NMDA receptor function with enhanced potency at acidic pH and oral bioavailability for clinical use. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2021; 379(1): 41–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gibaldi M, Perrier D. Pharmacokinetics 2nd Edition, Chapter 11: Non-compartmental Analysis Based on Statistical Moment Theory, Marcel Dekker, Inc. (New York: ), 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yanai K, Okamura N, Tagawa M, Itoh M, Watanabe T. New findings in pharmacological effects induced by antihistamines: from PET studies to knock-out mice. Clin Exp Allergy 1999; 29 Suppl 3:29–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lengyel C, Dézsi L, Biliczki P, Horváth C, Virág L, Iost N, Németh M, Tálosi L, Papp JG, Varró A. Effect of a neuroprotective drug, eliprodil on cardiac repolarisation: importance of the decreased repolarisation reserve in the development of proarrhythmic risk. Br J Pharmacol 2004; 143(1):152–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawai M, Ando K, Matsumoto Y, Sakurada I, Hirota M, Nakamura H, Ohta A, Sudo M, Hattori K, Takashima T, Hizue M, Watanabe S, Fujita I, Mizutani M, Kawamura M. Discovery of ( )-6-[2-[4-(3-fluorophenyl)-4-hydroxy-1-piperidinyl]-1-hydroxyethyl]-3,4-dihydro-2(1H)-quinolinone—A potent NR2B-selective N-methyl DD-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist for the treatment of pain. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2007; 17 (20): 5558–5562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mott DD, Doherty JJ, Zhang S, Washburn MS, Fendley MJ, Lyuboslavsky P, Traynelis SF, Dingledine R. Phenylethanolamines inhibit NMDA receptors by enhancing proton inhibition. Nat Neurosci. 1998. 1(8):659–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang H, James ML, Venkatraman TN, Wilson LJ, Lyuboslavsky P, Myers SJ, Lascola CD, Laskowitz DT. pH-sensitive NMDA inhibitors improve outcome in a murine model of SAH. Neurocrit Care. 2014; 20(1):119–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Deidentified data described in this manuscript are available upon request when allowed, as patients were not consented to provide individual data beyond that used for the research study.