Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To determine if maternal cardiac disease affects delivery mode and to investigate maternal morbidity.

STUDY DESIGN:

Retrospective cohort study performed using electronic medical record data. Primary outcome was mode of delivery; secondary outcomes included indication for cesarean delivery, and rates of severe maternal morbidity.

RESULTS:

Among 14,160 deliveries meeting inclusion criteria, 218 (1.5%) had maternal cardiac disease. Cesarean delivery was more common in women with maternal cardiac disease (adjusted odds ratio 1.63 [95% confidence interval 1.18–2.25]). Patients delivered by cesarean delivery in the setting of maternal cardiac disease had significantly higher rates of severe maternal morbidity, with a 24.38-fold higher adjusted odds of severe maternal morbidity (95% confidence interval: 10.56–54.3).

CONCLUSION:

While maternal cardiac disease was associated with increased risk of cesarean delivery, most were for obstetric indications. Additionally, cesarean delivery in the setting of maternal cardiac disease is associated with high rates of severe maternal morbidity.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, maternal morbidity, cesarean delivery, preeclampsia

INTRODUCTION

Maternal cardiac disease (MCD) complicates 1–4% of all pregnancies and is associated with an increased risk of significant morbidity and mortality.1,8–10 Increasing maternal age, higher prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities, and improved survival of individuals with congenital heart disease (CHD) has led to increased prevalence of women with pre-existing cardiovascular disease becoming pregnant.2,3 Pre-existing cardiovascular disease includes a spectrum of inherited and acquired cardiac disease, such as aortopathies, ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, valvular disease, simple and complex arrhythmias, and repaired and unrepaired congenital heart disease.4,5

Cardiac disease has important implications during pregnancy due to the notable hemodynamic changes that occur during pregnancy.6 Cardiac output rises throughout pregnancy, increasing by up to 40% in the third trimester, and can increase up to 50% in the second stage of labor.7 Due to these physiologic hemodynamic changes, women with MCD are at risk of significant cardiac morbidity and mortality,8–10 with pulmonary edema and arrhythmias being the most common complications.11–12 MCD is also associated with poor obstetric outcomes, including preterm delivery, preterm premature rupture of membranes, postpartum hemorrhage, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.12–13

Although there has been a reduction in pregnancy-related mortality due to hemorrhage and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy over the last several decades, there has been an increase in deaths attributable to MCD.14–16 While maternal cardiac death is a rare event occurring in 0.3% of women with MCD, cardiac events including arrhythmia, heart failure, stroke, and myocardial infarction occur in approximately 16% of these women.11 The Centers for Disease Control identified 21 indicators of severe maternal morbidity (SMM) and reported an increased rate of cardiac arrest, ventricular fibrillation, or conversion of cardiac rhythm between 1993–2004.17 However, these data do not stratify by presence of MCD and the prevalence of SMM in MCD patients is unknown.

Given the increased risk of cardiac events and cardiac death among women with MCD, an important consideration is safest delivery method. Although there are high risk MCD patients who may benefit from a cesarean delivery, vaginal delivery is considered the safest method of delivery for most patients, sometimes with a passive second stage (i.e., avoidance of pushing and use of operative vaginal delivery).4,20 Current consensus guidelines reserve cesarean delivery for standard obstetric indications for most cardiac lesions; however, a paucity in data supporting this approach can lead to potentially unnecessary cesarean deliveries.21 Cesarean delivery is not a benign intervention and carries acute maternal and fetal risks, as well as elevated risk of complications in subsequent pregnancies.18–19 At our tertiary care referral center, hypothesized that rate of cesarean delivery was increased among women with MCD. We additionally sought to investigate associations between maternal cardiac disease and adverse obstetric outcomes, including hypertensive disorders and incidence of SMM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective cohort study using data from deliveries performed at two hospitals in an academic health system from December 2015 (first center) and July 2016 (second center) until June 2020. The starting dates were selected based date of adoption of our current electronic medical record platform at each facility. Rather than manually reviewing all deliveries at each facility to identify MCD patients, we first screened for potential MCD using discharge codes from the delivery hospitalization or recorded on the patients EMR problem list (Appendix A for list of the codes used). For those patients identified with potential MCD, the chart was reviewed and a screening form completed to confirm the presence of MCD, and to categorize the patient’s MCD if present. Clinically-relevant patient characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes were then extracted from the EMR via automated queries.

MCD was defined as previous and existing aortopathy (such as Marfan’s disease, Ehlers Danlos, and dilation with bicuspid aortic valve), cardiomyopathy (including hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy), any valvular dysfunction, arrhythmias (including supraventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation and Wolff-Parkinson White), repaired and unrepaired congenital heart disease and ischemic heart disease. The manual chart review excluded clinically insignificant cardiac disease. If mitral valve prolapse was accompanied by any additional issues such as regurgitation, change in ejection fraction, or impact to care it was included in that category. If it was solely mitral valve prolapse it was excluded during manual chart review as it was not deemed clinically significant cardiac disease. Exclusion criteria for our primary analysis included any obstetric contraindication to vaginal delivery, including active herpes simplex virus infection, malpresentation, placenta or vasa previa, or three or more prior cesarean deliveries. The database was created to only include women who had at least one outpatient encounter before delivery (to exclude those patients who were transferred without records of their cardiac disease for delivery). Primary outcome was mode of delivery; secondary outcomes included indication for CD, and rates of severe maternal morbidity (SMM). Data collected included demographic data, delivery outcomes, patient comorbidities, and adverse obstetric outcomes including preeclampsia and preeclampsia with severe features by American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) criteria. Comorbid conditions were identified by using a version of an Obstetric-specific comorbidity index, updated by the study authors to ICD-10 coding, and by adjustment of criteria developed for an international version of ICD-10 for United States implementation8,9. Comorbid conditions were identified based on diagnosis codes present in the patient’s pregnancy problem list or delivery hospitalization. Similarly, the US Center for Disease Control’s Severe Maternal Morbidity (SMM) criteria were used to identify SMM from diagnosis codes during the delivery hospitalization17 because we did not have available for analysis the procedure codes from the delivery hospitalization, use of the CDC coding-based criteria for blood transfusion, hysterectomy, tracheostomy and ventilation were not available. We were able to identify blood transfusions through other data elements in the EMR, and in our experience viewing records from our facility, cases involving hysterectomy, tracheostomy, or ventilation are also captured as an SMM event by other element of the SMM composite outcome (e.g., even if not possible to capture the hysterectomy, patients having an unplanned hysterectomy had other SMM events occur such as blood transfusion and thus would be corrected identified has having had an SMM).

Unadjusted associations were assessed using t-tests and chi-squared tests as appropriate, with multivariable logistic regression employed for adjusted associations between MCD and outcomes. Clustering by patient was used to adjust standard errors for the multiple deliveries for some patients in the dataset. Variables were selected a priori based on hypothesized potential confounding with outcomes, and included patient age, race, body mass index, gestational age at delivery, number of prior cesarean deliveries, and a selected number of comorbid conditions, including alcohol use, asthma, chronic kidney disease, cystic fibrosis, gestational diabetes and pre-gestational diabetes mellitus, drug abuse, HIV, multiple gestation, sickle cell disease, and tobacco use. Of note, race was selected for inclusion not because we believe there to be an underlying biological link between race and mode of delivery, but because race as a social construct has been strongly correlated with cesarean delivery rates in prior studies. Body mass index was the only variable with missing values, and was missing in 13.9% of the sample. It was thus imputed using Predictive mean matching, a multiple imputation technique. We then conducted similar analyses for SMM.

Data were extracted from the EMR by the Johns Hopkins Core for Clinical Research and Data Acquisition. The additional clinical data were extracted from the EMR and entered via a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database by the study investigators. Data were analyzed using Stata, Version 16.1 (Statacorp, College Station, Texas). A two-sided alpha level of 0.05 was pre-specified as statistically significant. This study was approved by Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board, under protocol 00211591.

RESULTS

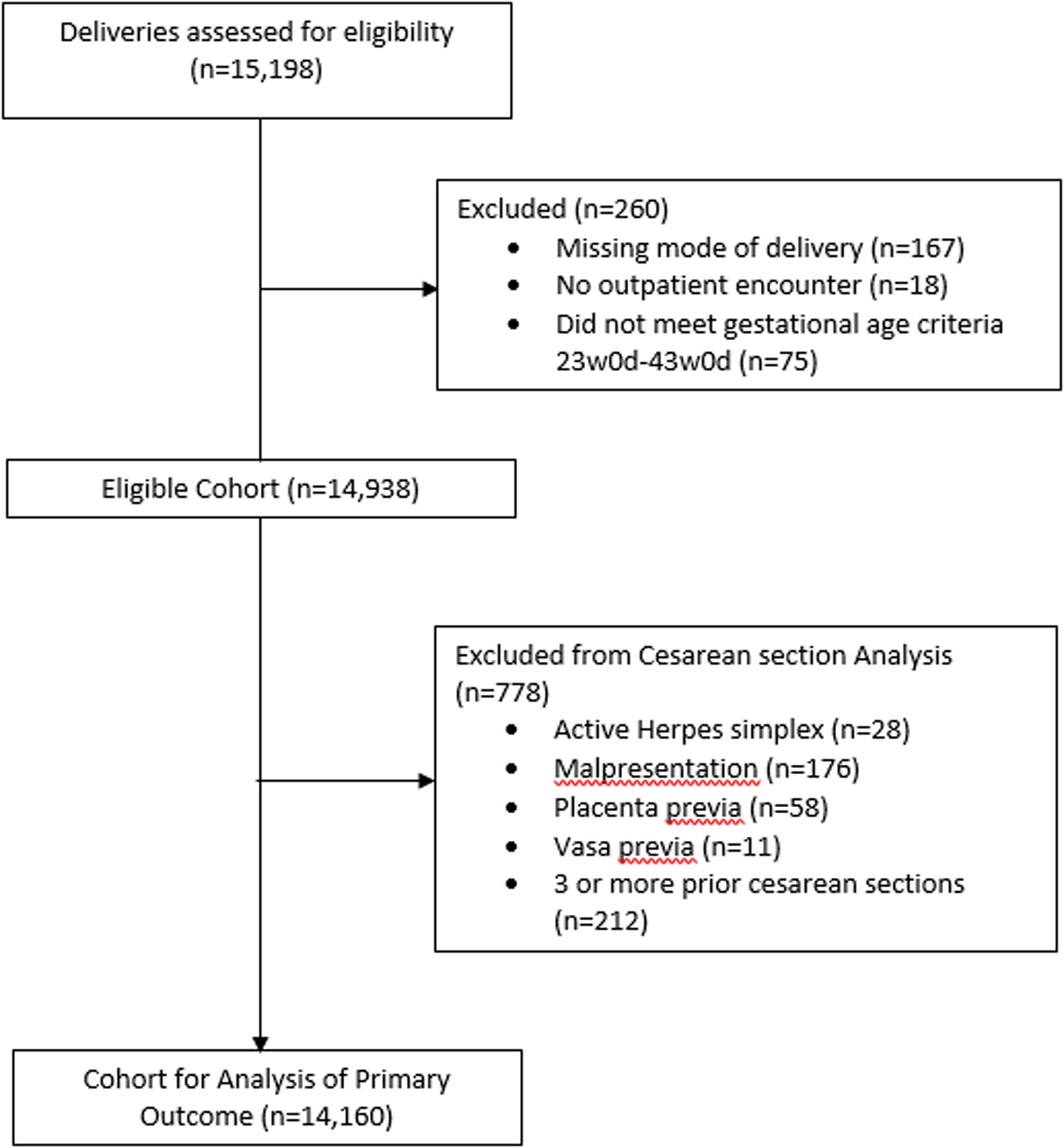

A total of 15,198 deliveries were assessed for eligibility in this study, based on deliveries starting December 2015 for one facility and July 2016 at the other and ending June 2020 (Figure 1). Exclusions included 260 for missing mode of delivery, lack of outpatient encounter, or falling outside the gestational age (GA) criteria of 23 to 43 weeks, leaving 14,938 deliveries eligible. Patients with a contraindication to vaginal delivery were excluded, including those with active herpes simplex virus outbreak, malpresentation, placenta previa, vasa previa, and those who had three or more prior cesarean deliveries, leaving a final total of 14,160 deliveries among 13,047 unique patients (Figure 1). Of these deliveries, 297 were screened as potentially having MCD, of which 218 were confirmed on manual review of charts. There was a variety of heart disease including 47 patients with cardiomyopathy, 32 patients with aortopathy, 86 with arrhythmia and 86 with congenital heart disease. Of note, these groups were not mutually exclusive as some patients had more than one category of cardiac disease and were then in both categories. There was also heterogeneity in the congenital heart disease: 8 patients had transposition of the great vessels, 7 had tetralogy of Fallot, 3 had double outlet right ventricle, 1 had valvular atresia, 23 had a ventricular septal defect, 17 had an atrial septal defect, and 43 had unspecified congenital heart disease.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram of Study Population

Deliveries assessed for eligibility were screened based on exclusion criteria and cohort for analysis of primary outcome was obtained.

Important differences were noted between the baseline characteristics of patients with and without MCD (Table 1). Patients with MCD were more likely to be white (50.9% vs 35.0%, p<0.001) and less likely to be Hispanic or Latina (9.2% vs 21.0%, p<0.001) than those without MCD. They were more likely to have asthma (27.5% versus 17.1%, p<0.001), chronic hypertension (11.0% versus 5.5%, p<0.001), chronic kidney disease (1.8% versus 0.4%, p = 0.001), multiple gestations (5.0% versus 2.7%, p = 0.04), and lupus (1.8% versus 0.6%) when compared to patients without MCD. They were additionally delivered at an earlier gestational age (38+0/7 weeks’ GA versus 38+5/7 weeks’, p<0.001) than those patients without MCD. Rates of other comorbid conditions, parity, history of cesarean birth, age, and body mass index did not differ between patients with and without MCD.

Table 1:

Patient characteristics, stratified by whether had maternal cardiac disease

| Any complex heart disease | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N=14,160) |

No (N=13,942) |

Yes (N=218) |

p | |

| Mean (Standard Deviation) or % | ||||

| Obstetric Characteristics | ||||

| Cesarean Delivery | 4,283 (30.2) | 4,191 (30.1) | 92 (42.2) | <0.001 |

| Gestational age (days) | 271.0 (14.9) | 271.1 (14.8) | 266.1 (18.5) | <0.001 |

| Parity | 0.88 | |||

| Nulliparous (%) | 5,811 (41.0) | 5,712 (41.0) | 99 (45.4) | |

| Para 1 | 4,549 (32.1) | 4,483 (32.2) | 66 (30.3) | |

| Para 2 | 2,229 (15.7) | 2,196 (15.8) | 33 (15.1) | |

| Para 3 or more | 1,571 (11.2) | 1,551 (11) | 20 (9.2) | |

| Prior Cesarean Births | 0.21 | |||

| No prior | 11,437 (80.8) | 11,269 (80.8) | 168 (77.1) | |

| One prior | 2,119 (15) | 2,083 (14.9) | 36 (16.5) | |

| Two prior | 604 (4.3) | 590 (4.2) | 14 (6.4) | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 29.4 (5.9) | 29.4 (5.9) | 29.7 (5.6) | 0.50 |

| Race/Ethnicity | <0.001 | |||

| Other | 567 (4.0) | 556 (4.0) | 11 (5.0) | |

| White | 4,991 (35.2) | 4,880 (35.0) | 111 (50.9) | |

| Black | 4,715 (33.3) | 4,646 (33.3) | 69 (31.7) | |

| Hispanic/Latina | 2,953 (20.9) | 2,933 (21.0) | 20 (9.2) | |

| Asian | 934 (6.6) | 927 (6.6) | 7 (3.2) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 32.2 (6.7) | 32.2 (6.7) | 32.2 (8.0) | 0.97 |

| Comorbid Conditions | ||||

| Alcohol abuse | 155 (1.1) | 150 (1.1) | 5 (2.3) | 0.09 |

| Asthma | 2,449 (17.3) | 2,389 (17.1) | 60 (27.5) | <0.001 |

| Gestational diabetes | 1,603 (11.3) | 1,581 (11.3) | 22 (10.1) | 0.56 |

| Pregestational diabetes | 451 (3.2) | 445 (3.2) | 6 (2.8) | 0.71 |

| Drug abuse | 1,683 (11.9) | 1,660 (11.9) | 23 (10.6) | 0.54 |

| HIV Disease | 104 (0.7) | 104 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.20 |

| Chronic hypertension | 787 (5.6) | 763 (5.5) | 24 (11.0) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 59 (0.4) | 55 (0.4) | 4 (1.8) | 0.001 |

| Gestational hypertension | 1,330 (9.4) | 1,309 (9.4) | 21 (9.6) | 0.90 |

| Preeclampsia without severe features | 673 (4.8) | 665 (4.8) | 8 (3.7) | 0.45 |

| Preeclampsia with severe features or ecclampsia | 1,016 (7.2) | 999 (7.2) | 17 (7.8) | 0.72 |

| Multiple gestations | 394 (2.8) | 383 (2.7) | 11 (5.0) | 0.04 |

| Sickle Cell Disease | 449 (3.2) | 445 (3.2) | 4 (1.8) | 0.26 |

| Lupus | 81 (0.6) | 77 (0.6) | 4 (1.8) | 0.01 |

| Tobacco Use | 1,212 (8.6) | 1,194 (8.6) | 18 (8.3) | 0.87 |

P-values by t-test for continuous variables and chi2 test for binary / categorical variables

Missing values in Body Mass Index (1,969 observations)

The primary outcome was cesarean delivery. Women with MCD were more likely to undergo cesarean delivery, with a cesarean delivery rate of 42.2% vs 30.1%, (p<0.001) compared to those without MCD (odds ratio 1.70, 95% CI: 1.28 to 2.25, p<0.001; Table 2). With adjustment for potential confounding variables, women with MCD continued to be more likely to undergo cesarean delivery (adjusted odds ratio 1.63, 95% CI 1.18 to 2.25, p=0.003). A secondary analysis was performed to assess if certain categories of cardiac lesion were more likely to be associated with cesarean delivery. After adjusting for potential confounders, patients with arrhythmia were more likely to have a cesarean delivery with an odds ratio of 1.77 (95% CI of 1.03 to 3.05, p=0.04). Indications for cesarean delivery were investigated (Table 3) and patients with MCD were more likely to have had reported an indication of maternal condition precluding vaginal delivery compared to patients in the control group (p<0.001). Otherwise, cesarean deliveries were performed for standard obstetric indications, most commonly for history of prior cesarean delivery, non-reassuring fetal heart tracing, and arrest of descent (Table 3).

Table 2.

Risk of cesarean Delivery, overall and stratified by MCD diagnosis

| n (%) Cesarean | Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted* Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any Maternal Cardiac Disease (N = 218) | 92 (42.2) | 1.70 (1.30, 2.23) | 1.63 (1.18, 2.25) |

| Cardiomyopathy (N = 47) | 23 (48.9) | 2.21 (1.25, 3.93) | 1.34 (0.63, 2.86) |

| History of Cardiac Surgery (N = 69) | 24 (34.8) | 1.23 (0.75, 2.02) | 1.06 (0.48, 2.35) |

| Congenital Heart Disease (N = 86) | 30 (34.9) | 1.23 (0.79, 1.93) | 0.93 (0.45, 1.93) |

| Arrhythmia (N = 86) | 38 (44.2) | 1.83 (1.20, 2.81) | 1.77 (1.02, 3.04) |

| Aortopathy (N = 32) | 17 (53.1) | 2.62 (1.31, 5.25) | 2.23 (0.95, 5.28) |

Odds ratios compared to no MCD.

Models adjusted for patient age, race, parity, number of prior cesarean deliveries, body mass index, gestational age at delivery, and presence of selected comorbid conditions (alcohol use, asthma, cystic fibrosis, chronic kidney disease, gestational diabetes mellitus, pre-gestational diabetes, drug use, HIV/AIDS, multiple gestations, sickle cell anemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, and tobacco use)

Table 3:

Indications for cesarean delivery

| Maternal Cardiac Disease | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N=4,283) |

No (N=4,191) |

Yes (N=92) |

p-value | |

| Mean (Standard Deviation) or % | ||||

| Repeat Elective | 1,102 (25.7) | 1,080 (25.8) | 22 (23.9) | 0.69 |

| Non-reassuring FHT | 877 (20.5) | 858 (20.5) | 19 (20.7) | 0.97 |

| Arrest of descent | 506 (11.8) | 496 (11.8) | 10 (10.9) | 0.78 |

| Malpresentation | 331 (7.7) | 323 (7.7) | 8 (8.7) | 0.73 |

| Other | 311 (7.3) | 304 (7.3) | 7 (7.6) | 0.9 |

| Primary Elective | 203 (4.7) | 198 (4.7) | 5 (5.4) | 0.75 |

| Remote Preeclampsia | 157 (3.7) | 153 (3.7) | 4 (4.3) | 0.72 |

| Prolonged Active Phase | 137 (3.2) | 134 (3.2) | 3 (3.3) | 0.97 |

| Multiples | 87 (2.0) | 85 (2.0) | 2 (2.2) | 0.92 |

| Prolonged Latent Phase | 82 (1.9) | 82 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.18 |

| Suspected CPD | 70 (1.6) | 70 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.21 |

| Placental Abruption | 46 (1.1) | 44 (1.0) | 2 (2.2) | 0.3 |

| Maternal Condition | 35 (0.8) | 31 (0.7) | 4 (4.3) | <0.001 |

| Suspected Macrosomia | 34 (0.8) | 32 (0.8) | 2 (2.2) | 0.13 |

| Failed operative delivery | 30 (0.7) | 29 (0.7) | 1 (1.1) | 0.65 |

| Fetal Anomaly | 27 (0.6) | 27 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.44 |

| Prolapsed Cord | 20 (0.5) | 20 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.51 |

| Suspected Rupture | 18 (0.4) | 18 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.53 |

| Fetal Condition | 13 (0.3) | 13 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.59 |

| Cerclage in Place | 5 (0.1) | 5 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.74 |

| Abnormal Placentation | 5 (0.1) | 4 (0.1) | 1 (1.1) | 0.006 |

P-values by t-test for continuous variables and chi2 test for binary / categorical variables

CPD: cephalopelvic Disproportion, FHT: Fetal heart rate tracing

Rates of severe maternal morbidity (SMM) were strongly correlated with the presence of MCD and route of delivery (Table 4). In unadjusted analyses, rates of SMM and non-transfusion SMM were lowest among patients who delivered vaginally without MCD and highest among patients with MCD who delivered by cesarean delivery. Adjusted analyses were consistent with these trends; compared with patients delivering vaginally without MCD, patients delivering by cesarean delivery with MCD had 24.38-fold higher adjusted odds of non-transfusion SMM (95% CI: 10.95 to 54.30), compared with 5.05-fold higher odds for MCD patients delivering vaginally (95% CI: 1.68 to 15.15).

Table 4:

Rates of Severe Maternal morbidity, stratified by MCD diagnosis and route of delivery

| N (%) | Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | Adjusted* Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe Maternal Morbidity | |||

| No MCD, Vaginal Delivery | 174 (1.8) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| No MCD, Cesarean Delivery | 377 (9.0) | 5.44 (4.53, 6.54) | 5.10 (4.00, 6.46) |

| MCD, Vaginal Delivery | 5 (4.0) | 2.27 (0.92, 5.65) | 2.33 (0.91, 5.99) |

| MCD, Cesarean Delivery | 26 (28.3) | 21.68 (13.24, 35.51) | 18.57 (10.67, 32.30) |

| Non-Transfusion Severe Maternal Morbidity | |||

| No MCD, Vaginal Delivery | 61 (0.6) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| No MCD, Cesarean Delivery | 101 (2.4) | 3.92 (2.85, 5.40) | 3.65 (2.49, 5.34) |

| MCD, Vaginal Delivery | 4 (3.2) | 5.21 (1.86, 14.58) | 5.05 (1.68, 15.15) |

| MCD, Cesarean Delivery | 14 (15.2) | 28.51 (15.26, 53.28) | 24.38 (10.95, 54.30) |

Odds ratios compared to no MCD / vaginal delivery.

Models adjusted for patient age, race, parity, number of prior cesarean deliveries, body mass index, gestational age at delivery, and presence of selected comorbid conditions (alcohol use, asthma, cystic fibrosis, chronic kidney disease, gestational diabetes mellitus, pre-gestational diabetes, drug use, HIV/AIDS, multiple gestations, sickle cell anemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, and tobacco use)

DISCUSSION

Principal findings

We find that patients with MCD have a higher rate of cesarean delivery than patients without MCD; however, this difference is driven in part by differences in underlying comorbidities, and that indications for cesarean delivery in this population are largely limited to standard obstetric indications. Only a small number of patients were delivered by cesarean delivery for maternal cardiac conditions alone. This may be due to the collaboration of cardiology and maternal fetal medicine in determining initial delivery mode plan. All patients who were delivered by cesarean for cardiac indications had a multidisciplinary planning meeting with cardiology, anesthesia, maternal fetal medicine, and intensive care units.

A subgroup analysis showed women with arrhythmias were more likely to have cesarean delivery in comparison to other MCD. This may be because women with arrhythmias are clinically decompensating, necessitating urgent delivery, given that arrhythmias are the most common cardiac complications antepartum.11 Alternatively, women with new arrhythmias may have undergone cesarean delivery to expedite delivery and recovery. Maternal arrhythmias are common antenatal complications in patients with CHD, which makes increased cesarean delivery rate in the arrhythmia population an interesting finding.25

Additionally, we find that when patients with MCD are delivered by cesarean delivery, their rates of SMM and non-transfusion SMM are significantly higher than patients with MCD delivered vaginally. We would hypothesize that MCD have low cardiac reserve and the added stress of a cesarean delivery puts them at higher risk for SMM. Interestingly, the most common reason for primary cesarean delivery in MCD was non-reassuring fetal status. Therefore, an alternative explanation is that a non-reassuring fetal status mirrored a sub-clinical maternal decompensation intrapartum necessitating urgent delivery, leading these patients to be more prone to SMM.

Results in Context of What is Known

The Registry on Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC), an extensive database on maternal cardiac disease, reports that maternal morbidity, specifically preeclampsia, heart failure, and maternal death, is increased in patients with MCD who undergo a planned cesarean delivery.26 Our data add to this existing literature by inclusion of a non-cardiac disease cohort for comparison, indicating that women delivered by cesarean delivery with MCD had the highest rates of non-transfusion related SMM. This is both in comparison to patients without MCD and in comparison to those with MCD who delivered vaginally.

Clinical and research implications

Clinically, demonstration of increased SMM in patients with MCD who have a cesarean delivery should lead providers to consider vaginal delivery the safest mode of delivery in this high risk population. Vaginal delivery, when it is not contraindicated for an obstetric or cardiac reason such as dilated aortic root, is a good option for women with heart disease to mitigate the risk of development of SMM.

Future research should focus on expanding data to specific cardiac lesions by collaborating with other institutions. Given that in our population, women with arrhythmias were more likely to have a cesarean delivery, this group should be investigated further, ideally with a prospective study enrolling patients with all types of arrhythmias. These women are also often advised to avoid prolonged Valsalva, and future studies should evaluate incidence of operative delivery in this population.27 Additionally, recent studies have identified an increased risk of preeclampsia in a subset of cardiac disease patients, specifically those with valvular disease.28 The increased risk of preeclampsia in that population was not replicated in our study, likely due to the overall high prevalence of preeclampsia in our population, but this warrants additional investigation. Future steps should also include evaluation of neonatal outcomes of patients with cardiac disease, especially those who developed preeclampsia, to evaluate for morbidity and mortality.

Strengths and Limitations

Analysis of this cohort of almost 15,000 deliveries and over 200 women with MCD adds important data to the growing literature on cardiac disease in pregnancy. All research was conducted at a tertiary care hospital system, with frequent referrals of cardiac patients. Data was collected both through automatic chart review and also through manual chart review in order to minimize missing or inaccurate information from electronic medical record. Limitations of the study include an overall small sample size of MCD patients (n=218), which precluded adequate statistical power to assess outcomes of more specific cardiac diagnoses. While our analysis was limited to maternal outcomes, addition of fetal outcomes would provide additional context. Additionally, these results may not be universally generalizable as not all hospitals have access to multidisciplinary teams and cesarean rate attributable to “maternal condition” may be higher.

Conclusions

In a center with extensive experience in delivery of patients with MCD, cesarean delivery was performed more commonly in patients with MCD than in those without, but primarily for usual obstetric indications. Among patients with MCD, rates of SMM were lower among those patients delivered vaginally. This supports the practice of offering women with MCD vaginal delivery in the majority of cases.

Supplementary Material

Source of Funding:

A.V. received funding through the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development Building Interdisciplinary Research in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) Award (K12-HD085845) and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Robert E. Meyerhoff Professorship Award. G.S is supported by Blumenthal Scholarship In Preventive Cardiology. A.M. was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute training grant T32HL007024, the Lou and Nancy Grasmick Endowed Research Fellowship and the Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Endowed Fellowship. J.J.F. was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences via award TL1TR002555.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflict of interest

DATA AVAILABILITY

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Regitz-Zagrosek V, Roos-Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Cifkova R, De Bonis M et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2018. Sep; 39:3165–3241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fretts RC, Schmittdiel J, McLean FH, Usher RH, Goldman MB. Increased maternal age and the risk of fetal death. N Engl J Med. 1995. October 12; 333 15: 953– 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan A, Wolfe D, Zaidi AN. Pregnancy and Congenital Heart Disease: A Brief Review of Risk Assessment and Management. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2020. Dec;63(4): 836–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canobbio MM, Warnes CA, Aboulhosn J, Connolly HM, Khanna A, Koos BJ et al. 2017. Management of Pregnancy in Patients with Complex Congenital Heart Disease, Circulation. 135(8):e50–e87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smok DA. Aortopathy in Pregnancy. Seminars Perinatology; 2014. 38(5):295–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ouzounian JG, Elkayam U. Physiologic Changes During Normal Pregnancy and Delivery. Cardiology Clinics; 2012. 30(3): 317–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nanna M, Stergiopoulos K. Pregnancy complicated by valvular heart disease: an update. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014. 5;3(3):e000712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashrafi R, Curtis SL. Heart Disease and Pregnancy. Cardiol Ther. 2017;6(2):157–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elkayam U, Goland S, Pieper PG, Silverside CK. High-Risk Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy: Part I. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016; 68(4):396–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elkayam U, Goland S, Pieper PG, Silverside CK. High-Risk Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy: Part II. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016; 68(5):502–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silversides CK, Grewal J, Mason J, Sermer M, Kiess M, Rychel V et al. Pregnancy Outcomes in Women With Heart Disease: The CARPREG II Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018. May, 71 (21) 2419–2430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anon. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 212: Pregnancy and Heart Disease. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2019;133:e320–e356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anon. ACOG Practice Bulletin No 222. Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2020; 135 (6): e237–e260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu P, Haththotuwa R, Kwok CH, Babu A, Kotronias RA, Rushton C et al. Preeclampsia and Future Cardiovascular Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2017; 10 (2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roos-Hesselink JW, Ruys TP, Stein JI, Thilen U, Webb GD, Niwa K et al. Outcome of pregnancy in patients with structural or ischaemic heart disease: results of a registry of the European Society of Cardiology. ROPAC Investigators. Eur Heart J 2013;34:657–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tuncalp O, Moller AB, Daniels A et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e323–e333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Severe Maternal Morbidity. Centers for Disease Control. Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2020.

- 18.Dahlgren LS, Dadelszen PV, Christilaw J, Janssen PA, Lisonkova S, Marquette GP et al. Caesarean section on maternal request: risks and benefits in healthy nulliparous women and their infants. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009. Sep; 31(9):808–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Signore C, Klebanoff M. Neonatal morbidity and mortality after elective cesarean delivery. Clin Perinatol. 2008. Jun; 35(2):361–71, vi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arendt KW, Lindley KJ. Obstetric Anesthesia management of the patient with cardiac disease. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2019;37:73–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Easter SR, Rouse CE, Duarte V, Hynes JS, Singh MN, Landzberg MJ et al. Planned vaginal delivery and cardiovascular morbidity in pregnant women with heart disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020. Jan;222(1):77.e1–77.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sibai BM. Evaluation and Management of Severe Preeclampsia before 34 weeks’ gestation. SMFM Clinical Opinion. 2013;203(3):p191–198. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malhamé I, Danilack VA, Raker CA, et al. Cardiovascular severe maternal morbidity in pregnant and postpartum women: development and internal validation of risk prediction models. BJOG. 2021. Apr;128(5):922–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ackerman CM, Platner MH, Spatz ES, et al. Severe cardiovascular morbidity in women with hypertensive diseases during delivery hospitalization. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019. Jun;220(6):582.e1–582.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hardee I, Wright L, McCracken C, Lawson E, Oster ME. Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes of Pregnancies in Women With Congenital Heart Disease: A Meta-Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021. Apr 20;10(8):e017834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruys TPE, Roos-Hesselink JW, Pijuan-Domenech A, Vasario E, Gaisin IR, Iung B et al. Is a planned caesarean section in women with cardiac disease beneficial? Heart 2015;101:530–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Safi LM, Tsiaras SV. Update on Valvular Heart Disease in Pregnancy. Curr Treat Options Cardio Med 2017. Sep; 19(9): 70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minhas AS, Rahman F, Gavin N, Cedars A, Vaught AJ, Zakaria S et al. Cardiovascular and Obstetric Delivery Complications in Pregnant Women With Valvular Heart Disease. The Ame J Cardiol. 2021. 158;90–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.