Abstract

Background

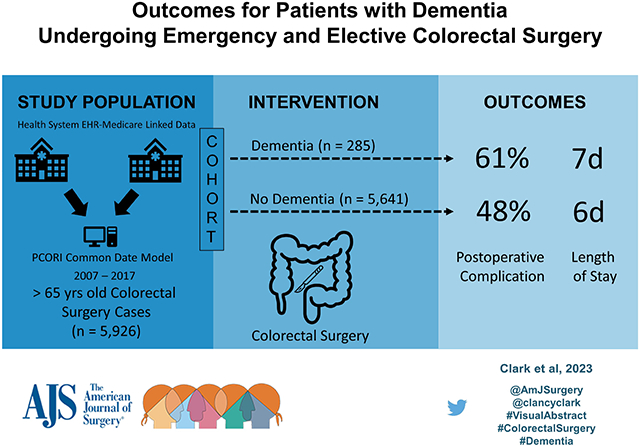

Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD) may result in poor surgical outcomes. The current study aims to characterize the risk of ADRD on outcomes for patients undergoing colorectal surgery.

Methods

Colorectal surgery patients with and without ADRD from 2007-2017 were identified using electronic health record-linked Medicare claims data from two large health systems. Unadjusted and adjusted analyses were performed to evaluate postoperative outcomes.

Results

5,926 patients (median age 74) underwent colorectal surgery of whom 4.8% (n=285) had ADRD. ADRD patients were more likely to undergo emergent operations (27.7% vs. 13.6%, p<0.001) and be discharged to a facility (49.8% vs 28.9%, p<0.001). After multi-variable adjustment, ADRD patients were more likely to have complications (61.1% vs 48.3%, p<0.001) and required longer hospitalization (7.1 vs 6.1 days, p=0.001).

Conclusions

The diagnosis of ADRD is an independent risk factor for prolonged hospitalization and postoperative complications after colorectal surgery.

Keywords: colectomy, proctectomy, total abdominal colectomy, dementia, Alzheimer's disease

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD) comprise a broad range of cognitive memory deficits that may result in poor clinical outcomes particularly for patients undergoing surgery.1-6 Dementia and cognitive impairment can lead to functional decline, postoperative delirium, and poor rehabilitation potential after surgery.3,7,8 In advanced cases, ADRD results in higher health care expenditures and requires significant care giver and institutional support.9-11 In general, patients with ADRD are more likely to undergo emergent surgery and are more likely to transition to nursing home after hospitalization than patients without ADRD.12 However, it is not well understood if an impairment in cognitive function adversely impacts recovery after colectomy. With an aging population in the United States, patients with ADRD will become more common and decisions around colorectal surgery will need to account for the impact of dementia on surgical risk, postoperative recovery, and resources required to ensure optimal surgical outcomes.13

Colorectal procedures are among the most common inpatient operations in adults.14,15 While multiple studies have demonstrated that major abdominal operations can be safely performed in older adults, worse postoperative outcomes are associated with increasing age.16,17 When examining surgical outcomes for nursing home patients, of whom 64% have a diagnosis of ADRD, postoperative complications are significantly more common compared to community-dwelling patients (32% vs 13%).18,19 In addition, nursing home residents undergoing colon cancer surgery have a one year postoperative mortality over 50%.7 It is not clear if the poor outcomes see in older institutionalized patients is due to ADRD or other factors such as comorbidities; in addition, the majority of persons with ADRD live at home and prior studies of nursing home patients may not be representative of the majority of patients with dementia undergoing colorectal surgery.20

The current study aims to measure associations between ADRD and postoperative condition-specific outcomes for patients undergoing elective and emergent colorectal operations using a large multi-institutional dataset. We hypothesize that patients with preoperative ADRD undergoing colectomy will have worse postoperative outcomes compared with patients without preoperative ADRD.

Materials & Methods

Patient Selection

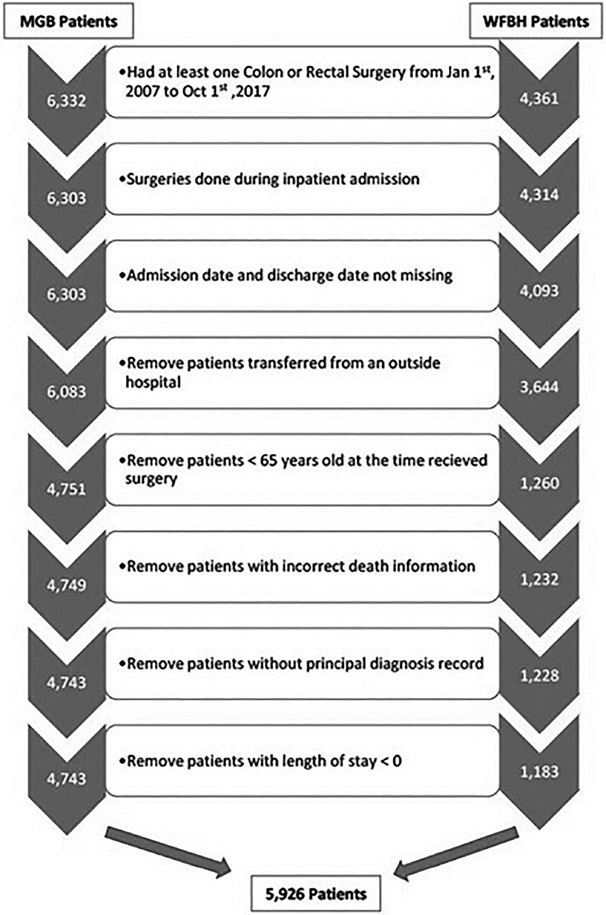

Patient cohort selection is outlined in Figure 1 flow chart. All patients over 65 years old who underwent colorectal surgery (ICD-9 and ICD-10 procedure codes available in Appendix) were identified using electronic health record (EHR)-linked Medicare claims data from two major health care networks, Wake Forest Baptist Health (WFBH) in Winston-Salem, North Carolina and Mass General Brigham (MGB) in Boston, Massachusetts, from January 1, 2007 to October 1, 2017. To enable linkage with Medicare claims data, patients were required to be enrolled in Medicare at time of inpatient encounter. The EHR-linked Medicare claims data is based on the PCORI Common Data Model (CDM) and contains rich clinical data including patient demographics, inpatient and outpatient encounters, procedures, diagnoses, medications, and test results.21-23 The PCORI CDM enables merging of complex and often heterogenous datasets from multiple independent healthcare organizations. Elective and emergency colorectal surgery requiring inpatient admission were included. Patients were excluded if they were missing admission date or discharge date or with invalid date information. Patients without principal diagnosis were removed. Patients transferred from an outside hospital also were excluded to avoid potential mis-categorization of admission type, as well as to avoid unknown biases associated with the transfer and indication for transfer.24-26 The both the MGB and Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Institutional Review Boards approved the study.

Figure 1.

Study Cohort Selection

Study Variables

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics included: age, sex, race, encounter diagnoses, in-hospital procedures, length of stay, postoperative outcomes, discharge destination, and mortality. To evaluate comorbidity burden, an Elixhauser comorbidity score was assigned to each patient using the van Walraven et al. comorbidity algorithm and was based on diagnoses at time of operation.27,28

The primary outcome measure was postoperative mortality based on vital status and date of death recorded in the EHR at time of discharge, 30-days and 90-days from operation. In-hospital mortality was defined as death during the index hospitalization. Vital status was missing for 207 (3.5%) patients.

Secondary outcomes included postoperative length of stay (number of days from date of operation to date of discharge), discharge location, readmission due to any cause (within 30 days and 90 days of index operation), and postoperative complications. Discharge location was defined as expired in hospital, facility, home, hospice, or other. Prolonged length of stay was defined as length of stay greater than six (6) days which was the median length of stay for the entire study cohort. Postoperative complications were determined using ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis and procedure codes at time of discharge from index operation, 30-days, and 90-days. The number of complications was defined as the total number of unique postoperative complication diagnosis and procedure codes documented at the outcome time point of interest (discharge, 30-day, or 90-days). Complications were organized into eight diagnostic subtypes (intraoperative, wound, infection, renal and urinary, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular) and two procedural subtypes (blood product transfusion and postoperative re-intervention).29 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) General Equivalence Mappings (GEMS) were used to map ICD-9 to respective ICD-10 diagnosis and procedure codes.30,31 Emergent operation was defined as having an emergency room encounter within one day of the admission.

Definition of a Colorectal Operation

Type of colorectal operation was defined using previously described categories determined by ICD-9 and ICD-10 procedure codes (Appendix).32-34 Categories included abdominal perineal resection, colostomy with or without colectomy, laparoscopic partial colectomy, open partial colectomy, other rectal, pull through, or total colectomy. For patients who underwent multiple colorectal procedures during the index operation, each procedure code combination was independently reviewed and categorized into a specific type of colorectal operation based on the more complex or more invasive procedure.

Indication for the colorectal operation was based on the discharge diagnosis at the index admission using previously described ICD-9 diagnosis codes.32-34 ICD-9 indication codes were mapped to respective ICD-10 diagnosis codes as described above. For encounters with multiple potential indications, each combination of diagnosis codes was independently reviewed and categorized based on expert opinion.

Additional procedures were defined as any procedure occurring after the date of the index colorectal operation and prior to discharge for the hospital.

Definition of the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD)

Patients with ADRD were identified using a validated algorithm with high sensitivity and specificity of identifying ADRD patients in a Medicare beneficiary population.35 This algorithm uses ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes from on all prior inpatient and outpatient encounters as well as the index hospitalization to identify patients with ADRD (Appendix).35 Patients diagnosed with ADRD after discharge, non-specific cognitive impairment, and reversible cognitive impairment were not classified as having preoperative ADRD.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted independently at MGB and WFBH per data use agreement and in accordance with the STROBE statement (https://www.strobe-statement.org). For each study site, continuous data, median and standard error were calculated by using quantile regression.36 For categorical data, proportions were calculated for each category. Unadjusted results from these two separate site analyses were then combined to conduct a multi-health system analysis. Medians from two sites were combined using optimal unrestricted weighted least squares for meta-analyses.37 Frequencies from two sites were combined by adding up counts in each category and two-sided Person chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests were performed to evaluate the unadjusted associations for categorical variables. Unadjusted analysis was performed examining postoperative outcomes including length of stay, mortality, and readmission. For adjusted analyses, multi-variable analyses within site were performed. The model adjusted for sex, age, Elixhauser comorbidity score and emergency operation. Optimal weighted least square regressions were conducted to combine adjusted results from the two sites. Per the data use agreement, if the number count was less than 11, the data are reported as < 11 with redaction of total number. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC).

Results

Sample Characteristics

A total of 5,926 patients (median age 74, 57.7% female) who underwent colorectal operations were included in the study cohort. Of these, 285 (4.8%) had a diagnosis of ADRD (Table 1). Nearly all patients 5,746 (97.0%) had at least one comorbidity. Patients with ADRD were more likely to have multiple comorbidities and significantly more likely to have congestive heart failure, cardiac arrhythmia, valvular heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, hypertension, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease (all p < 0.05). Overall, the median Elixhauser comorbidity index for patients with ADRD was slightly higher than patients without ADRD (14.0 vs 11.2, p=0.008).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics with and without Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD)

| Variable | Overall N=5,926 |

No ADRD N=5,641 |

ADRD N=285 |

p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (SE) | 73.6 (0.13) | 73.3 (0.12) | 80.0 (0.58) | <0.001 |

| Female Sex, No. (%) | 3,419 (57.69) | 3,245 (57.53) | 174 (61.05) | 0.240 |

| White, No. (%) | 5,238 (88.39) | 4,989 (88.44) | 249 (87.37) | 0.581 |

| Emergency Operation, No. (%) | 844 (14.24) | 765 (13.56) | 79 (27.72) | <0.001 |

| Type of Operation, No. (%) | 0.004 | |||

| APR* | - | 193 (3.42) | <11 | |

| Colostomy with or without colectomy | 216 (3.64) | 202 (3.58) | 14 (4.91) | |

| Laparoscopic Partial Colectomy | 1,130 (19.07) | 1,094 (19.39) | 36 (12.63) | |

| Open Partial Colectomy | 3,316 (55.96) | 3,135 (55.58) | 181 (63.51) | |

| Other Rectal | 787 (13.28) | 759 (13.46) | 28 (9.82) | |

| Pull through | - | 74 (1.31) | <11 | |

| Total Colectomy | 195 (3.29) | 184 (3.26) | 11 (3.86) | |

| Indication, No. (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Cancer | 2,412 (40.70) | 2,316 (41.06) | 96 (33.68) | |

| Cancer, Other Site | 866 (14.61) | 849 (15.05) | 17 (5.96) | |

| Diverticular Disease | 739 (12.47) | 701 (12.43) | 38 (13.33) | |

| Benign Neoplasm | - | 412 (7.30) | - | |

| Obstruction | 213 (3.59) | 188 (3.33) | 25 (8.77) | |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | - | 163 (2.89) | <11 | |

| Prolapse | 159 (2.68) | 136 (2.41) | 23 (8.07) | |

| Perforation or Fistula | 188 (3.17) | 174 (3.08) | 14 (4.91) | |

| Vascular or Bleeding | 199 (3.36) | 183 (3.24) | 16 (5.61) | |

| Infection | 222 (3.75) | 205 (3.63) | 17 (5.96) | |

| Other | 337 (5.69) | 314 (5.57) | 23 (8.07) | |

| Elixhauser Score, median (SE) | 11.24 (0.27) | 11.24 (0.28) | 14.00 (1.01) | 0.008 |

| Additional Procedures During Index Admission, No. (%) | <0.001 | |||

| None | 5,136 (86.67) | 4,911 (87.06) | 225 (78.95) | |

| One | 388 (6.55) | 352 (6.24) | 36 (12.63) | |

| More than One | 402 (6.78) | 378 (6.70) | 24 (8.42) |

Note: If count less than 11, the count is reported as < 11 and total is redacted per the data use agreement.

APR, abdomino-perineal resection

Cancer was the most common indication for colorectal operation (40.7%, n = 2,412) overall (Table 1). Indication for operation varied significantly between patients with and without ADRD (p < 0.05). Cancer operation was slightly less common with patients with ADRD than patients without ADRD (33.7% vs 41.1%, p<0.001). Operations for obstruction, prolapse, vascular complications, or bleeding were 2.5 times more common in patients with ADRD (22.5%, n = 64) compared with patients without ADRD (9.0%, n = 507).

Number of procedures ranged from one to six (e.g., colon resection and liver resection) during the index operation with 89.9% (n = 5,325) of patients having only one procedure. For patients with more than one procedure during the index operation, there was no difference between patients with ADRD (8.1%, n = 23) vs patients without ADRD (10.3%, n = 578) (p = 0.235). However, during the entire hospital admission, additional procedures were more frequent in patients with ADRD (23.3%, n = 60) vs patients without ADRD 12.9%, n = 730) (p < 0.001). See Appendix Table 4 for most common additional procedures by frequency.

Emergent colorectal operations were significantly more common for patients with ADRD (27.7%, n = 79) vs patients without ADRD (13.6%, n = 765) (p < 0.001). Partial colectomy was the most common operation (75.0%, n = 4,446) with the majority being an open partial colectomy (56.0%, n = 3,316). Colostomy with or without colectomy and total colectomy represented a small portion of all colorectal operations (7.0%, n = 411) but represented significantly larger proportion of emergency colorectal operations (13.6%, n = 115) (p < 0.001).

Unadjusted Outcomes

In-hospital mortality overall was 4.1% (n = 193), with 5.0% (n = 11) in patients with ADRD vs 4.0% (n= 182) without ADRD (p = 0.482). 30-day mortality overall was 4.5% (n = 212), with 7.3% (n = 16) in patients with ADRD vs 4.3% (n = 196) without ADRD (p = 0.045). 90-day mortality overall was 7.9% (n = 376) with 14.1% (n = 31) in patients with ADRD vs 7.6% (n = 345) without ADRD (p = 0.001).

Total number of in-hospital complications ranged from 0 to 7 with 48.9% (n=2,896) of patients having at least one complication (Table 2). For patients with ADRD, 61.1% (n = 174) had at least one in-hospital complication compared with 48.3% (n = 2,722) without ADRD (p < 0.001). At least one complication occurred within 30-days of operation for 59.6% (n = 3,531). 71.2% (n = 203) of patients with ADRD had a complication within 30-days of operation compared with 59.0% (n = 3,328) of patients without ADRD (p < 0.001). At least one complication occurred within 90-days of the operation for 64.5% (n = 3,821) of patients. 73.7% (n = 210) of patients with ADRD had a complication within 90-days of operation compared with 64.0% (n = 3,611) of patients without ADRD (p < 0.001). Patients with ADRD had significantly more postoperative infections; renal, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal complications, and required more blood transfusions than patients without ADRD (all p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Postoperative Outcomes for Patients with and without Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD)

| Variable | Overall N=5,926 |

No ADRD N=5,641 |

ADRD N=285 |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of Stay, median (SE), Days, missing = 0 | 6.13 (0.06) | 6.13 (0.06) | 7.08 (0.28) | 0.001 |

| Length of Stay > 6 days, No. (%) | 2,721 (45.92) | 2,549 (45.19) | 172 (60.35) | <0.001 |

| Mortality | ||||

| In-Hospital | 235 (3.97) | 220 (3.90) | 15 (5.26) | 0.250 |

| 30-day | 279 (4.71) | 256 (4.54) | 23 (8.07) | 0.006 |

| 90-day | 468 (7.90) | 427 (7.57) | 41 (14.39) | <0.001 |

| Readmission ** | ||||

| 30-day | 893 (15.69) | 831 (15.33) | 62 (22.96) | <0.001 |

| 90-day | 1,309 (23.00) | 1,232 (22.73) | 77 (28.52) | 0.027 |

| Discharge Location, No. (%) * | <0.001 | |||

| Expired | 235 (3.97) | 220 (3.90) | 15 (5.26) | |

| Facility | 1,773 (29.92) | 1,631 (28.91) | 142 (49.82) | |

| Home | 3,517 (59.35) | 3,425 (60.72) | 92 (32.28) | |

| Hospice | - | 31 (0.55) | <11 | |

| Other | - | 146 (2.59) | - | |

| Missing | 207 (3.49) | 188 (3.33) | 19 (6.67) | |

| In-Hospital Complications, n (%) | ||||

| Intraoperative Complication | 260 (4.39) | 246 (4.36) | 14 (4.91) | 0.658 |

| Wound Complication | - | 171 (3.03) | <11 | 0.829 |

| Postoperative Infection | 1,403 (23.68) | 1,306 (23.15) | 97 (34.04) | <0.001 |

| Renal Complication | 660 (11.14) | 602 (10.67) | 58 (20.35) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary Complication | 562 (9.48) | 518 (9.18) | 44 (15.44) | <0.001 |

| GI Complication | 817 (13.79) | 762 (13.51) | 55 (19.30) | 0.006 |

| Cardiovascular Complication | 425 (7.17) | 398 (7.06) | 27 (9.47) | 0.123 |

| Systemic Complication | - | 56 (0.99) | <11 | 0.217 |

| Blood Transfusion | 1,276 (21.53) | 1,196 (21.20) | 80 (28.07) | 0.006 |

| Postoperative Intervention | 425 (7.17) | 400 (7.09) | 25 (8.77) | 0.283 |

| 30-day Complications, n (%) | ||||

| Intraoperative Complication | 341 (5.75) | 322 (5.71) | 19 (6.67) | 0.498 |

| Wound Complication | 480 (8.10) | 451 (8.00) | 29 (10.18) | 0.188 |

| Postoperative Infection | 2,100 (35.44) | 1,958 (34.71) | 142 (49.82) | <0.001 |

| Renal Complication | 879 (14.83) | 809 (14.34) | 70 (24.56) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary Complication | 1003 (16.93) | 928 (16.45) | 75 (26.32) | <0.001 |

| GI Complication | 1,346 (22.71) | 1,260 (22.34) | 86 (30.18) | 0.002 |

| Cardiovascular Complication | 731 (12.34) | 688 (12.20) | 43 (15.09) | 0.148 |

| Systemic Complication | 210 (3.54) | 198 (3.51) | 12 (4.21) | 0.533 |

| Blood Transfusion | 1,153 (19.46) | 1,085 (19.23) | 68 (23.86) | 0.054 |

| Postoperative Intervention | 439 (7.41) | 420 (7.45) | 19 (6.67) | 0.624 |

Note: If count less than 11, the count is reported as < 11 and total is redacted per the data use agreement.

Vital status missing for 207patients.

Exclude patients died in hospital.

Overall median length of stay was 6 days (SE 0.06). Length of stay was significantly longer for patients with ADRD vs. without ADRD (7.1 days vs 6.1 days, p =0.001). Discharge destination was different for patients with ADRD. Discharge to facility occurred overall in 29.9% (n = 1,773) of patients with 49.8% (n = 142) in patients with ADRD vs 28.9% (n = 1,631) without ADRD (p < 0.001). 30-day readmission was overall 15.7% (n = 893) with 23.0% (n = 62) in patients with ADRD vs 15.3% (n = 831) without ADRD (p < 0.001). 90-day readmission was overall 23.0% (n = 1,309) with 28.5% (n = 77) in patients with ADRD vs 22.7% (n = 1,232) without ADRD (p = 0.027).

Adjusted outcomes

Multi-variable adjusted analysis of postoperative outcomes was performed to account for risk factors associated with worse postoperative outcomes (Tables 3). In-hospital, 30-day, and 90-day mortality were similar for patients with and without ADRD (all p > 0.05). ADRD was associated with a prolonged length of stay (> 6 days) (OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.14 - 1.20, p = 0.004). ADRD was also associated with an increased risk of postoperative complication (OR 1.32, CI 1.00 - 1.73, p = 0.049) and 30-day readmission (OR 1.57, CI 1.16-2.12, p = 0.004). Details of the adjusted analysis for length of stay, mortality, complications, and readmission are provided in the Appendix.

Table 3.

Adjusted Postoperative Outcomes for Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias*

| Outcome | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOS > 6 days ** | 1.50 | 1.14 - 1.98 | 0.004 |

| In-Hospital Mortality | 0.80 | 0.44 - 1.43 | 0.450 |

| 30-day Mortality | 1.13 | 0.70 - 1.85 | 0.612 |

| 90-day Mortality | 1.34 | 0.91 - 1.99 | 0.142 |

adjusted by age, sex, emergency operation, and Elixhauser score

Median LOS of entire study cohort

Discussion

In this current study of patients undergoing colorectal surgery, in-hospital, 30-day, and 90-day mortality did not differ between patients with ADRD and patients without, yet patients with ADRD experienced far greater morbidity. Over 60% of patients with ADRD had at least one complication, were more likely to have prolonged hospitalization, and were more likely to be discharged to a facility. While previous reports have also demonstrated poor postoperative outcomes for ADRD patients undergoing surgery, this is the first large multi-institutional study to evaluate adverse events in patients with dementia undergoing both elective and emergent colorectal operations.1,2,4,6-13

Short-term, 30-day and 90-day, mortality was nearly two times more common in patients with ADRD in unadjusted analyses; but, after adjusting for risk factors, ADRD was not associated with increased mortality. The current study results are similar to a Norwegian study of colorectal surgery patients with memory impairment. In this small study of 182 patients, memory impairment was not associated with an increased risk of complication or short-term mortality.38 Consistent with prior studies, the current found that advanced age, comorbidities, and emergent operation were significant risk factors for increased postoperative pmortality.17,39,40

Nearly a third (27.7%) of patients with ADRD underwent an emergent colorectal operation compared with 13.6% of patients without ADRD. Colorectal operations for cancer and diverticulitis were the common indications for both patients with and without ADRD. However, prolapse, bleeding, vascular disease, and obstruction, were more common among ADRD patients and likely explains the larger proportion of ADRD patients undergoing emergent surgery. Understanding the disproportionate number of patients with ADRD undergoing emergent operations warrants further investigation particularly if the operation is associated with increased postoperative complications. The higher proportion of emergent operations in patients with ADRD may align with patient and caregiver long-term goals of improving quality of life or potential achieving some palliation while assuming short-term postoperative complication risks. Unfortunately, the current study was not designed to evaluate patient and provider goals associated with the operation.

In the current study, 4.8% of patients undergoing colorectal surgery had a preoperative diagnosis of ADRD. This is significantly lower than the prevalence of ADRD among the general population of older adults but similar to prior studies of surgery patients.13,35,40,41 In a clinical chart review of Medicare beneficiaries from 2016-2018, 7% of all patients were found to have ADRD.35 In analysis of Premier Healthcare Database, an all-payer, hospital-based, administrative and billing database, overall 6.4% of patients were found to have diagnosis of ADRD and for surgical patients only 3.4% had a diagnosis of ADRD.13 Neuman et al. evaluated outcomes for surgical treatment of colon cancer in older patients using SEER-Medicare linked database.40 In the Neuman et al. study, the prevalence of ADRD for patients undergoing colectomy for cancer was only 1.8% compared with 6.1% for those who did not undergo resection.40 In a study by Raji et al., 10% of all colon cancer patients were found to have a diagnosis of ADRD.41 For patients with colorectal disease, our study and others indicate that a proportion of patients with ADRD will never undergo colorectal surgery where an operation may have been beneficial. Clinical outcomes along with the financial and emotional burden of this untreated population of ADRD patients with colorectal disease remains unknown.

The strength of the current study is that it is the first comprehensive evaluation of colorectal operations patients in patients over 65 years old with ADRD. We now have a better understanding of surgical indications, type of operation, and expected postoperative outcomes in ADRD patients undergoing a major colorectal operation. In developing management guidelines and recommendations regarding surgical decision making for ADRD patients, this is only the beginning. Findings in this study will help build a foundation for guidelines, such as the American College of Surgeons Geriatric Surgery Verification program.42 The current study indicates that patients with ADRD need careful preoperative optimization including focused efforts on management of comorbidities (e.g. chronic kidney disease, COPD), preoperative discussion of discharge destination, and education regarding prolonged recovery (i.e. significantly longer hospitalization). Programs focused on after discharge telemedicine and in-home assessments may help prevent readmissions in this high-risk population.43,44

The current study has several limitations. First, severity and etiology of ADRD could not be assessed due to limitations of the dataset. Severity of ADRD may significantly impact postoperative outcomes and disposition after surgery. While the study was not designed to investigate the intent of surgery, disease severity may also have influenced who was offered surgery and the decision to proceed with surgery. Second, the current study did not evaluate the impact of postoperative delirium on outcomes. Prior studies report that patients with cognitive impairment are two times more likely to develop postoperative delirium.45 Third, it is possible the study cohort does not represent all ADRD patients; however, prior sensitivity and specificity studies indicate that patients with ADRD can be identified using the methods applied in the current study.46 Expansion of the study cohort to a large dataset, such Medicare claims data, may be address these limitations. Lastly, admission source was missing for most of the study cohort preventing an analysis of the impact of admission source (home vs nursing facility) on postoperative outcomes and discharge destination.

Conclusions

In conclusion, colorectal surgery patients with ADRD are older, have multiple comorbidities, and are more likely to require emergent operations. Additionally, after adjusting for risk factors associated with worse postoperative outcomes, patients with ADRD undergoing colorectal operations require longer postoperative length of stay, are more likely to be readmitted, and are more likely to have postoperative complications.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Dementia may complicate recovery after colorectal surgery.

Multi-variable analysis of 5,926 patients was performed using a large dataset.

Dementia was associated with worse outcomes after elective and emergent colorectal surgery.

Supported by:

R01AG067507, U01AG076478, P01AG032952, R01AG062282 R01AG056368, R01AG071809, R01AG062713, R21AG060227, and K24AG073527

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to report.

Disclaimer: The authors declare that they have no Conflicts of Interest.

Presentation Status: The manuscript has not been and will not be a podium or poster meeting presentation.

References

- 1.Bai J, Zhang P, Liang X, Wu Z, Wang J, Liang Y. Association between dementia and mortality in the elderly patients undergoing hip fracture surgery: A meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018;13(1):298. doi: 10.1186/s13018-018-0988-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kassahun WT. The effects of pre-existing dementia on surgical outcomes in emergent and nonemergent general surgical procedures: Assessing differences in surgical risk with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1). doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0844-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Racine AM, Fong TG, Gou Y, et al. Clinical outcomes in older surgical patients with mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(5):590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seitz DP, Gill SS, Gruneir A, et al. Effects of Dementia on Postoperative Outcomes of Older Adults With Hip Fractures: A Population-Based Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(5):334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah SK, Jin G, Reich AJ, Gupta A, Belkin M, Weissman JS. Dementia is associated with increased mortality and poor patient-centered outcomes after vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2020;71(5):1685–1690.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2019.07.087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsuda Y, Yasunaga H, Horiguchi H, Ogawa S, Kawano H, Tanaka S. Association between dementia and postoperative complications after hip fracture surgery in the elderly: analysis of 87,654 patients using a national administrative database. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015;135(11):1511–1517. doi: 10.1007/s00402-015-2321-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finlayson E, Zhao S, Boscardin WJ, Fries BE, Landefeld CS, Dudley RA. Functional status after colon cancer surgery in elderly nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(5):967–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03915.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaller F, Sidelnikov E, Theiler R, et al. Mild to moderate cognitive impairment is a major risk factor for mortality and nursing home admission in the first year after hip fracture. Bone. 2012;51(3):347–352. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amini R, Chee KH, Swan J, Mendieta M, Williams TM. The Level of Cognitive Impairment and Likelihood of Frequent Hospital Admissions. J Aging Health. 2019;31(6):967–988. doi: 10.1177/0898264317747078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu CW, Cosentino S, Ornstein KA, Gu Y, Andrews H, Stern Y. Interactive Effects of Dementia Severity and Comorbidities on Medicare Expenditures. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017;57(1):305–315. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dening KH, Jones L, Sampson EL. Advance care planning for people with dementia: a review. Int Psychogeriatrics. 2011;23(10):1535–1551. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211001608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callahan CM, Arling G, Tu W, et al. Transitions in care for older adults with and without dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(5):813–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03905.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masutani R, Pawar A, Lee H, Weissman JS, Kim DH. Outcomes of Common Major Surgical Procedures in Older Adults With and Without Dementia. JAMA Netw open. 2020;3(7):e2010395. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fingar KR, Stocks C, Weiss AJ, Steiner CA. Most Frequent Operating Room Procedures Performed in U.S. Hospitals, 2003–2012: Statistical Brief #186. Healthc Cost Util Proj Stat Briefs. Published online 2006:1–15. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25695123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliphant SS, Ghetti C, McGough RL, Wang L, Bunker CH, Lowder JL. Inpatient procedures in elderly women: An analysis over time. Matnritas. 2013;75(4):349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Massarweh NN, Devlin A, Symons RG, Broeckel Elrod JA, Flum DR. Risk tolerance and bile duct injury: surgeon characteristics, risk-taking preference, and common bile duct injuries. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.02.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamel MB, Henderson WG, Khuri SF, Daley J, Henderson AWG, Khuri SF. Surgical outcomes for patients aged 80 and older: Morbidity and mortality from major noncardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(3):424–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53159.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finlayson E, Wang L, Landefeld CS, Dudley RA. Major abdominal surgery in nursing home residents: A national study. Ann Surg. 2011;254(6):921–926. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182383a78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alzheimer’s Association. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(2):208–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrison KL, Ritchie CS, Patel K, et al. Care Settings and Clinical Characteristics of Older Adults with Moderately Severe Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(9):1907–1912. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corley DA, Feigelson HS, Lieu TA, McGlynn EA. Building data infrastructure to evaluate and improve quality: Pcornet. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(3):204–206. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.003194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandl KD, Kohane IS, McFadden D, et al. Scalable Collaborative Infrastructure for a Learning Healthcare System (SCILHS): architecture. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(4):615–620. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.PCORnet. PCORnet - data. The National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network. Published 2021. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://pcornet.org/data/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mueller SK, Zheng J, Orav J, Schnipper JL. Interhospital Transfer and Receipt of Specialty Procedures. J Hosp Med. 2017;176(1):139–148. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanmer J, Lu X, Rosenthal GE, Cram P. Insurance status and the transfer of hospitalized patients: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(2):81–90. doi: 10.7326/M12-1977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mueller S, Zheng J, Orav EJ, Schnipper JL. Inter-hospital transfer and patient outcomes: A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(11):E1. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130–1139. Accessed February 26, 2013. http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:Coding+Algorithms+for+Defining+Comorbidities+in#1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A, Quan H. A modification of the Elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care. 2009;47(6):626–633. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819432e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Worni M, Castleberry AW, Clary BM, et al. Concomitant vascular reconstruction during pancreatectomy for malignant disease: a propensity score-adjusted, population-based trend analysis involving 10,206 patients. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(4):331–338. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark CJ. ICD-9 to ICD-10 Crosswalk. GitHub. Published 2021. Accessed July 12, 2021. https://github.com/ClancyClark/ICD9to10crosswalk [Google Scholar]

- 31.CMS. CMS ICD-10. Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Published 2021. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/ICD10 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diaz A, Nuliyalu U, Dimick JB, Nathan H. Variation in Surgical Spending Among the Highest Quality Hospitals for Cancer Surgery. Ann Surg. 2020;Publish Ah. doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000004641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peery AF, Cools KS, Strassle PD, et al. Increasing Rates of Surgery for Patients With Nonmalignant Colorectal Polyps in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(5):1352–1360.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Addae JK, Gani F, Fang SY, et al. A comparison of trends in operative approach and postoperative outcomes for colorectal cancer surgery. J Surg Res. 2017;208:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moura LMVR, Festa N, Price M, et al. Identifying Medicare beneficiaries with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(8):2240–2251. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koenker R, Bassett G. Regression Quantiles. Econometrica. 1978;46:33–50. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stanley T, Doucouliagos H. Neither fixed nor random: weighted least squares meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2015;34(13):2116–2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kristjansson SR, Jordhøy MS, Nesbakken A, et al. Which elements of a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) predict post-operative complications and early mortality after colorectal cancer surgery? J Geriatr Oncol. 2010;1(2):57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2010.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Massarweh NN, Legner VJ, Symons RG, McCormick WC, Flum DR. Impact of advancing age on abdominal surgical outcomes. Arch Surg. 2009;144(12):1108–1114. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neuman HB, O’Connor ES, Weiss J, et al. Surgical treatment of colon cancer in patients aged 80 years and older : analysis of 31,574 patients in the SEER-Medicare database. Cancer. 2013;119(3):639–647. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raji MA, Kuo YF, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Effect of a dementia diagnosis on survival of older patients after a diagnosis of breast, colon, or prostate cancer: Implications for cancer care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(18):2033–2040. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.18.2033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geriatric Surgery Verification Program. American College of Surgeons. Published 2022. Accessed March 1, 2022. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/geriatric-surgery [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stapler S-J, Brockhaus KK, Battaglia MA, Mahoney ST, McClure AM, Cleary RK. A Single Institution Analysis of Targeted Colorectal Surgery Enhanced Recovery Pathway Strategies That Decrease Readmissions. Dis Colon Rectum. Published online December 9, 2021. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000002129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eustache J, Latimer EA, Liberman S, et al. A Mobile Phone App Improves Patient-Physician Communication And Reduces Emergency Department Visits After Colorectal Surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. Published online December 20, 2021. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000002187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rudolph JL, Jones RN, Rasmussen LS, Silverstein JH, Inouye SK, Marcantonio ER. Independent Vascular and Cognitive Risk Factors for Postoperative Delirium. Am J Med. 2007;120(9):807–813. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee E, Gatz M, Tseng C, et al. Evaluation of medicare claims data as a tool to identify dementia. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019;67(2):769–778. doi: 10.3233/JAD-181005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.