Abstract

Background:

Social determinants of health have been inadequately studied in preschool children with wheezing and their caregivers but may influence the care received.

Objective:

This study evaluated the symptom and exacerbation experiences of wheezing preschool children and their caregivers, stratified by risk of social vulnerability, over one year of longitudinal follow-up.

Methods:

Seventy-nine caregivers and their preschool children with recurrent wheezing and at least one exacerbation in the previous year were stratified by a composite measure of social vulnerability into “low” (N=19), “intermediate” (N=27), and “high” (N=33) risk groups. Outcome measures at the follow-up visits included child respiratory symptom scores, asthma control, caregiver-reported outcome measures of mental and social health, exacerbations, and healthcare utilization. The severity of exacerbations reflected by symptom scores and albuterol usage and exacerbation-related caregiver quality of life were also assessed.

Results:

Preschool children at high risk of social vulnerability had greater day-to-day symptom severity and more severe symptoms during acute exacerbations. High risk caregivers were also distinguished by lower general life satisfaction at all visits and lower global and emotional quality of life during acute exacerbations that did not improve with exacerbation resolution. Rates of exacerbation or emergency department visits did not differ, but intermediate and high risk families were significantly less likely to seek unscheduled outpatient care.

Conclusion:

Social determinants of health influence wheezing outcomes in preschool children and their caregivers. These findings argue for routine assessment of social determinants of health during medical encounters and tailored interventions in high risk families to promote health equity and improve respiratory outcomes.

Keywords: Asthma control, asthma exacerbation, caregiver burden, disparity, mental health, patient-reported outcomes, social determinants of health, wheezing

Introduction

Social determinants of health, defined by the World Health Organization as the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes,1 are increasingly recognized as having an important influence on clinical outcomes. Whereas social determinants of health and clinical outcomes have been well described in older children and adults with asthma,2, 3 lesser focus has been directed to wheezing preschool children and their caregivers. This is a major shortcoming. Although preschool children account for less than 10% of all children with current asthma,4 they have the highest prevalence of exacerbations and emergency visits compared to all other age groups.5 A recent study also found that preschool children with recurrent wheezing at highest risk of social vulnerability had more severe symptoms during respiratory infections, accompanied by poorer caregiver quality of life.6 Separate studies have similarly shown poorer caregiver asthma-related quality of life in children with severe versus mild-to-moderate wheezing7 and altered caregiver emotions, concerns and experiences during acute asthma exacerbations.8 Since preschool children are completely reliant on their caregivers for symptom recognition, medication administration, and healthcare, these altered health outcomes in preschool caregivers are of potential significance and may be a target for future interventions to promote health equity.

In this study, we questioned whether the symptom and exacerbation experiences of preschool children with recurrent wheezing and their caregivers over one year of longitudinal follow up are influenced by specific social determinants of health, namely ethnicity, race, and income surrogates. We hypothesized that children at highest risk of social vulnerability based on these specific variables would have more severe respiratory symptoms independent of and during acute exacerbations and that their caregivers would have more impaired mental and social health and quality of life.

Methods

Caregivers and their preschool children 12–59 months of age with recurrent wheezing and at least one wheezing episode treated with systemic corticosteroids in the previous 12 months were included in the study. Recurrent wheezing was defined as a lifetime history of two or more episodes of wheezing, each lasting at least 24 hours and requiring repeated treatment with albuterol sulfate. Children were excluded if they had co-morbid disorders associated with wheezing (such as immune deficiency, cystic fibrosis, pulmonary aspiration, congenital airway anomalies, or premature birth before 35 weeks gestation) or if they had a significant developmental delay or failure to thrive. Informed written consent was obtained from caregivers prior to study participation. All study procedures were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Overview of study design and respiratory symptom action plan.

This was a 12-month longitudinal study conducted between September 2019 and September 2022. Caregivers and their children completed visits at enrollment (week 0) and study weeks 14, 26, 38 and 50 (eFigure 1). Visits were postponed if the preschool children had an exacerbation treated with systemic corticosteroids in the preceding two weeks. At the enrollment visit, caregivers received a written action asthma plan for their child, an albuterol sulfate metered dose inhaler with a valved holding chamber and face mask, and prednisolone (2 mg/kg/day for 2 days followed by 1 mg/kg/day for 2 days). The action plan included green, yellow and red zones defined by symptoms (eFigure 2). The yellow zone was reserved for children who had difficulty breathing, coughing or wheezing, who could not go to school or play, or who were not sleeping well due to respiratory symptoms. The yellow zone instructed caregivers to administer two inhalations of albuterol sulfate every four hours as needed for up to 24 hours. The red zone was reserved for children whose symptoms were not improved with albuterol or for those children who still required albuterol after 24 hours. The red zone instructed caregivers to initiate the prednisolone prescription and to seek medical care. Caregivers were also provided with 24-hour direct telephone support from the study team.

Characterization procedures at enrollment.

At enrollment, caregivers completed demographic questionnaires and medical history questionnaires. ZIP code features were obtained from the United States Census Bureau QuickFacts and expressed in 2020 dollars, where applicable.9 Residential addresses were geocoded to census tracts and the Childhood Opportunity Index 2.0 was joined to patient data using the census tract GEOID as described previously.10, 11 Higher Childhood Opportunity Index values reflect better opportunity.12 Preschool participants also submitted blood samples for blood eosinophil counts and total and specific serum IgE (Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Atlanta, Georgia). Specific IgE testing was performed with twelve extracts: Dermatophagoides farinae, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, dog dander, cat dander, Blatella germanica, Alternaria tenuis, Aspergillus fumagatis, oak tree, pecan tree, Bermuda grass, Johnson grass, and common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia) (Greer® Laboratories, Lenoir, North Carolina). Children were considered sensitized if specific IgE values were ≥0.35 kU/L.

Caregiver diaries.

At the enrollment visit, caregivers received a written (i.e., paper and pencil) diary to be completed at home when their child experienced a worsening of respiratory symptoms. Diary cards for each day instructed caregivers to record inhalations of albuterol sulfate and to score the severity of four respiratory symptoms (cough, wheezing, trouble breathing, and activity limitation) on a scale from 0 (none) to 5 (very severe). Symptom questions were adapted from the Pediatric Asthma Caregiver Diary13 and were summed for a total score of 0–20, with higher scores reflecting greater respiratory symptoms. The diary cards also questioned whether prednisolone was administered. The diary also included copies of the Pediatric Asthma Caregiver’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (PACQLQ) to be completed on the first day of respiratory symptoms, on day 8, and on day 15. The PACQLQ contains 13 questions in two domains (activity and emotional function) that reflect the impact of the child’s asthma symptoms during the previous week. Responses were scored on a 7-point scale and averaged, with lower scores indicating poorer quality of life.14

Follow-up visit procedures.

At study week 14, 26, 38 and 50, caregivers were questioned about any medical illnesses, physician visits, or breathing problems. If breathing problems were reported, caregivers were asked about the presence of any runny nose, nasal congestion, poor appetite, or fever and whether any medications were administered. Caregivers were also asked to score the severity of their child’s cough, wheeze, trouble breathing, and activity interference over the past week on a scale from 0 (none) to 5 (very severe). Respiratory and asthma control were assessed in preschool children with the Test for Respiratory and Asthma Control in Kids (TRACK) questionnaire.15 This tool contains three questions pertaining to symptoms over the past 4 weeks, 1 question pertaining to short-acting beta agonist use over the past 3 months, and 1 question pertaining to oral corticosteroids over the past three months. Each question has 5 responses that are each summed on a scale between 0 and 20, with scores ≥80 reflecting good control.16 Caregivers also completed eight patient-reported outcome measures of mental and social health, including the PROMIS tools for general life satisfaction (5a), meaning and purpose (4a), emotional support (4a), social isolation (4a), depression (4a), anger (5a), and anxiety (4a) and the National Institutes of Health Toolbox fixed form for perceived stress. The PROMIS tools assessed symptoms over the past 7 days whereas the NIH Toolbox form assessed symptoms over the past month. These tools utilize a T-score metric in which 50 is the mean of the reference population and 10 is the standard deviation of the reference population. Higher T-scores reflect more the concept being measured.17

Social vulnerability determination.

Social vulnerability was defined with a composite variable of self-reported race (white=0, non-white=1), ethnicity (not Hispanic or Latino=0, Hispanic or Latino=1), and income (private insurance=0, Medicaid or self pay=1) similar to our previous published work.6 The three variable items were summed for a composite score. Groups were designated as “low risk” (score=0), “intermediate risk” (score=1) and “high risk” (score≥2).

Outcome measures.

Outcome measures at the follow-up visits included child respiratory symptom scores, TRACK questionnaire scores, caregiver-reported outcome measures of mental and social health, exacerbations, and healthcare utilization (Figure E1). Diary-reported outcomes included the severity of exacerbations reflected by symptom scores and albuterol usage and exacerbation-related caregiver quality of life. Exacerbation was defined in accordance with Workshop recommendations from the National Institutes of Health as a worsening of respiratory symptoms necessitating the use of systemic corticosteroids.18 Exacerbation necessitating healthcare utilization were confirmed by a review of medical records.

Outcome analyses.

Outcome analyses were performed with IBM SPSS software, version 28. Features of the groups at baseline were compared with Chi-Square tests and analysis of variance. Outcome analyses utilized analysis of variance with Tukey’s least significant differences post-hoc tests where indicated. Diary-reported albuterol use was expressed as albuterol metered-dose inhalations using a conversion of four metered-dose inhalations per every nebulized treatment utilized.19 Exploratory analyses were performed with linear regression without adjustments. All analyses utilized a 0.05 significance level without adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Results

Seventy-nine preschool children with recurrent wheezing and their caregivers were enrolled. Features of the preschool participants at enrollment, stratified by social vulnerability risk, are shown in Table 1. By definition, groups differed by race, ethnicity and payor status. Children at highest risk of social vulnerability had more sensitization than low risk children and lived in homes with lower educational attainment and lower combined income. High risk children also resided in ZIP codes with a higher population per square mile and a lower median value of owner-occupied homes. The Childhood Opportunity Index 2.0, a composite of 29 indicators measured at the census tract level that reflects neighborhood resources and conditions that are important for child development, was also significantly different between groups, with lowest opportunity in the high risk group. Other features such as age, wheezing history and treatment, current symptom control, and features of Type 2 inflammation in the preschool children were not significantly different between groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Features of the preschool participants at enrollment. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation, median (25th, 75th percentile) or the number of participants (%).

| Feature | Low risk N = 19 | Intermediate risk N=27 | High risk N=33 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | 31 ± 13 | 33 ± 11 | 36 ± 16 |

| Males | 13 (68.4) | 18 (66.7) | 20 (60.6) |

| Race | |||

| White | 19 (100) | 16 (59.3)* | 0*# |

| Black | 0 | 9 (33.3) | 29 (87.9) |

| Other | 0 | 2 (7.4) | 4 (12.1) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0 | 6 (22.2)* | 4 (12.1) |

| Age of symptom onset (months) | 18 ± 12 | 14 ± 10 | 13 ± 9 |

| Wheezing episodes (past 12 months) | 5.6 ± 4.1 | 5.7 ± 5.0 | 5.9 ± 5.8 |

| With unscheduled visits | 2.7 ± 2.3 | 3.0 ± 1.6 | 2.8 ± 1.3 |

| With oral corticosteroid bursts | 2.5 ± 1.5 | 2.7 ± 1.5 | 2.8 ± 2.8 |

| Past healthcare utilization for wheezing (ever in lifetime) | |||

| Hospitalization | 10 (52.6) | 13 (48.1) | 19 (57.6) |

| Intensive care unit admission | 1 (21.1) | 8 (29.6) | 11 (33.3) |

| Current controller medications | |||

| Inhaled corticosteroid | 11 (57.9) | 15 (55.6) | 14 (42.4) |

| Long-acting beta agonist | 1 (5.3) | 2 (7.4) | 5 (15.2) |

| Montelukast | 0 | 6 (22.2) | 5 (15.2) |

| Highest household education | |||

| Did not complete high school | 0 | 1 (3.7) | 0*# |

| High school or GED | 1 (5.3) | 0 | 4 (14.8) |

| Technical training | 0 | 0 | 3 (9.1) |

| Some college, no degree | 1 (5.3) | 1 (3.7) | 12 (36.4) |

| Associate degree | 0 | 4 (12.1) | 7 (21.2) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 17 (89.5) | 21 (77.8) | 7 (21.2) |

| Combined household income | |||

| Don’t know | 1 (5.3) | 2 (7.4) | 1 (3.0)*# |

| Less than $25,000 | 0 | 0 | 6 (18.2) |

| $25,000 - $49,999 | 0 | 2 (7.4) | 15 (45.5) |

| $50,000 - $99,999 | 5 (26.3) | 8 (29.6) | 9 (27.3) |

| $100,000 or more | 13 (68.4) | 15 (55.6) | 2 (6.1) |

| Payor status | |||

| No insurance | 0 | 1 (3.7)* | 6 (18.2)*# |

| Medicaid insurance | 0 | 9 (33.3) | 26 (78.8) |

| Private insurance | 19 (100) | 17 (63.0) | 1 (3.0) |

| Indoor exposures | |||

| Cat | 4 (21.1) | 3 (15.8) | 1 (3.0) |

| Dog | 9 (47.4) | 13 (48.1) | 6 (18.2)*# |

| Tobacco smoke | 3 (11.1) | 3 (11.1) | 3 (9.1) |

| Any aeroallergen sensitization | 2 (10.5) | 9 (33.3) | 10 (37.0)* |

| Serum IgE (kU/L) | 52 (12, 95) | 56 (20, 293) | 105 (20, 180) |

| Blood eosinophil count (cells/microliter) | 330 (145, 483) | 173 (101, 356) | 236 (202, 292) |

| ZIP code features | |||

| Population per square mile | 2382±1068 | 1712 ± 1276 | 2435 ± 831# |

| Median gross rent ($) | 1325±205 | 1235 ±209 | 1266±176 |

| Median value of owned homes (thousand $) | 322 ± 96 | 281±130 | 223 ± 92*# |

| Bachelors degree (% of people age ≥25 years) | 47.6 ± 17.0 | 38.3 ± 19.2 | 36.6 ± 14.6* |

| Persons in poverty (%) | 11.7 ± 6.2 | 14.2 ± 6.8 | 14.3 ± 4.2 |

| Childhood Opportunity Index 2.0 values (census tract level, raw values) | |||

| Education domain | 72.8 ± 28.6 | 62.2 ± 31.1 | 34.6 ± 30.4*# |

| Health and environment domain | 53.7 ± 27.7 | 43.3 ± 23.5 | 21.6 ± 17.4*# |

| Social and economic domain | 67.3 ± 29.1 | 51.4 ± 26.9 | 28.5 ± 25.5*# |

| Overall index | 68.7 ± 30.7 | 53.9 ± 29.1 | 28.2 ± 26.9*# |

p<0.05 versus low risk

p<0.05 vs. intermediate risk

Child symptom severity and control at follow up visits.

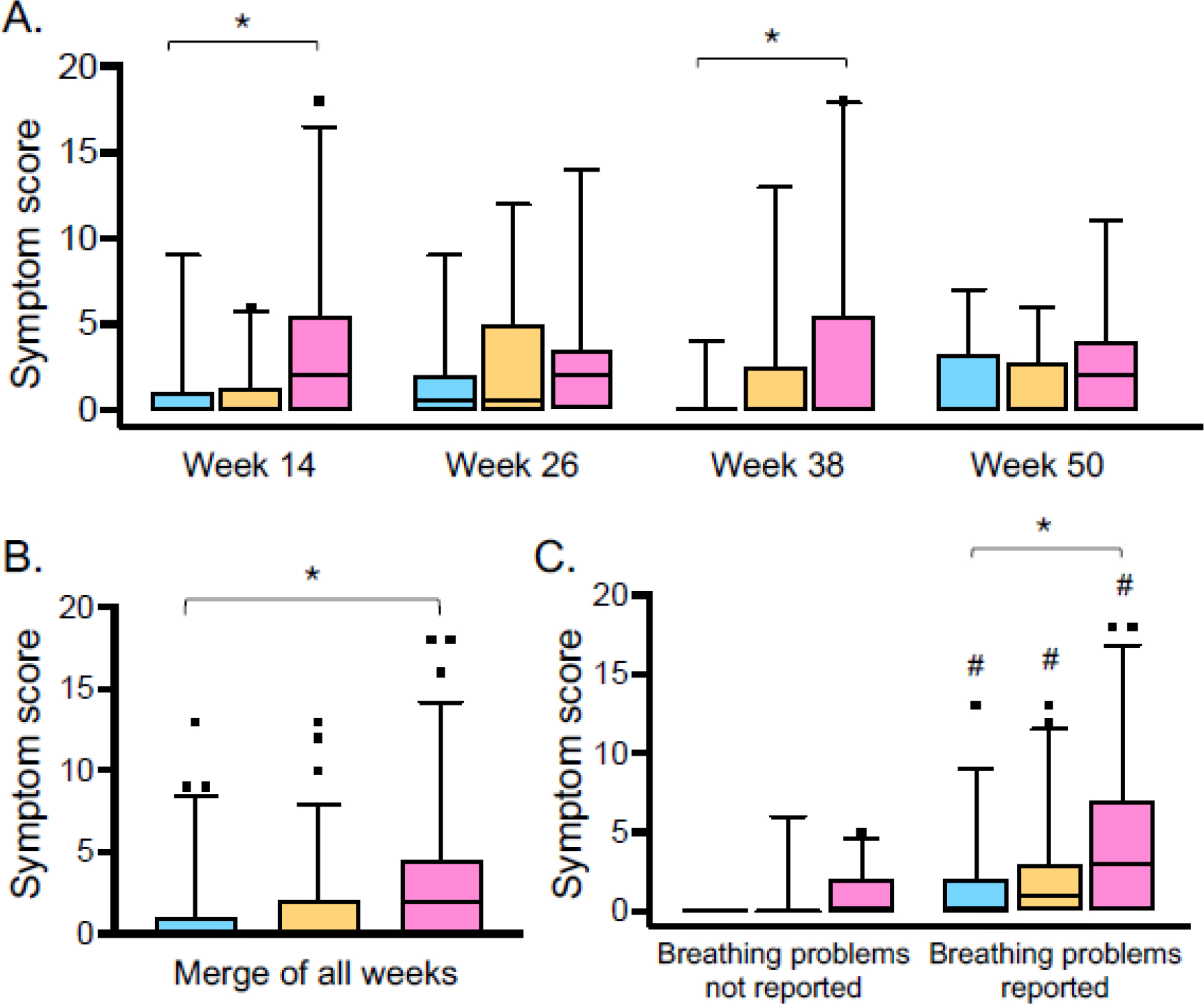

Child symptom scores at each visit were variable, but overall were higher in children at highest risk of social vulnerability (Figure 1A, B). Symptom scores remained significantly higher in the high risk group when the analysis was restricted to children with caregiver-reported “breathing problems” since the last visit (Figure 1C). In those children with caregiver-reported “breathing problems,” other symptoms of upper respiratory illnesses were also reported by caregivers, including runny nose (88.2% of children), nasal congestion (84.9% of children), poor appetite (57.9% of children), and fever (47.4% of children). These symptoms did not differ by social vulnerability grouping (runny nose, p=0.549; nasal congestion, p=0.693; poor appetite, p=0.293; fever, p=0.275).

Figure 1.

Child symptom scores (A) at each follow-up visit, (B) merged across all visits, and (C) stratified by caregiver reported “breathing problems” since the last study visit in children at low risk (blue), intermediate risk (orange), and high risk (pink) of social vulnerability. Boxplot lines and whiskers reflect the median and 5th-95th percentile, respectively. *p<0.05 for high risk vs. low risk; #p<0.05 versus breathing problems not reported, for same groups.

TRACK scores did not differ by social vulnerability group but were lower in all children with caregiver-reported “breathing problems” (eFigure 3). TRACK scores did correlate with symptom scores at each follow-up visit (week 14: r=−0.519, p<0.001; week 26: r=−0.492, p<0.001; week 38: r=−0.458, p<0.001; week 50: r=−0.527, p<0.001), suggesting that the performance of the TRACK instrument in this population was limited by the final question pertaining to exacerbations.

Caregiver mental and social health at follow-up visits.

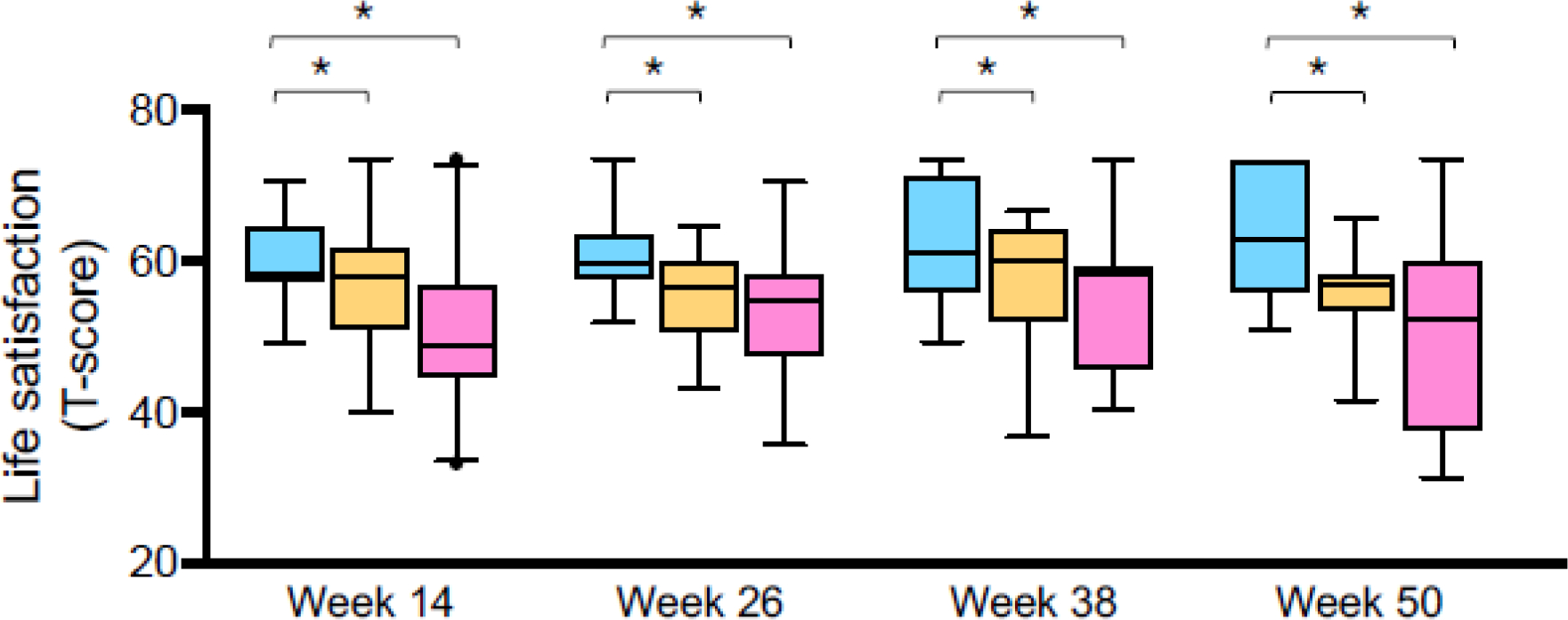

Caregiver-reported meaning and purpose, emotional support, social isolation, depression, anger, anxiety, and perceived stress were not different between groups at the follow-up visits (eTable 1). However, caregivers at highest risk of social vulnerability did report significantly lower general life satisfaction at each follow up visit (Figure 2). Life satisfaction scores were low in high-risk caregivers irrespective of the presence of any caregiver-reported “breathing problems” (eFigure 4), but these scores did correlate with the severity of the symptom score at three of the four follow-up visits (week 14: r=−0.458, p<0.001; week 26: r=−0.237, p=0.079; week 38: r=−0.387, p=0.009; week 50: r=−0.344, p=0.032).

Figure 2.

Caregiver general life satisfaction T-scores at each study visit, in caregivers at low risk (blue), intermediate risk (orange), and high risk (pink) of social vulnerability. Boxplot lines and whiskers reflect the median and 5th-95th percentile, respectively. *p<0.05 for pairwise comparisons. Comparisons that are not marked are not statistically significant.

Exacerbation occurrence and healthcare utilization.

Exacerbations treated with prednisolone occurred in 52 (65.8%) children, with no significant differences between groups (low risk, n=16 (84.2%); intermediate risk, n=16 (59.3%); high risk, n=20 (60.6%), p=0.152). The rate of exacerbations and rate of emergency department visits was also not different between groups (exacerbation rate: 2.50 ± 1.95 vs. 1.19 ± 1.39 vs. 2.13 ± 2.45 for low vs. intermediate vs. high risk, p=0.075; emergency department visits: 0.31 ± 0.48 vs. 0.33 ± 0.55 vs. 0.54 ± 0.88, p=0.475). However, children at lowest risk of social vulnerability were more likely to see an outpatient physician for unscheduled care (2.0 ± 1.5 vs. 0.70 ± 0.91 vs. 0.69 ± 1.0 visits for low vs. intermediate vs. high risk, p=0.036).

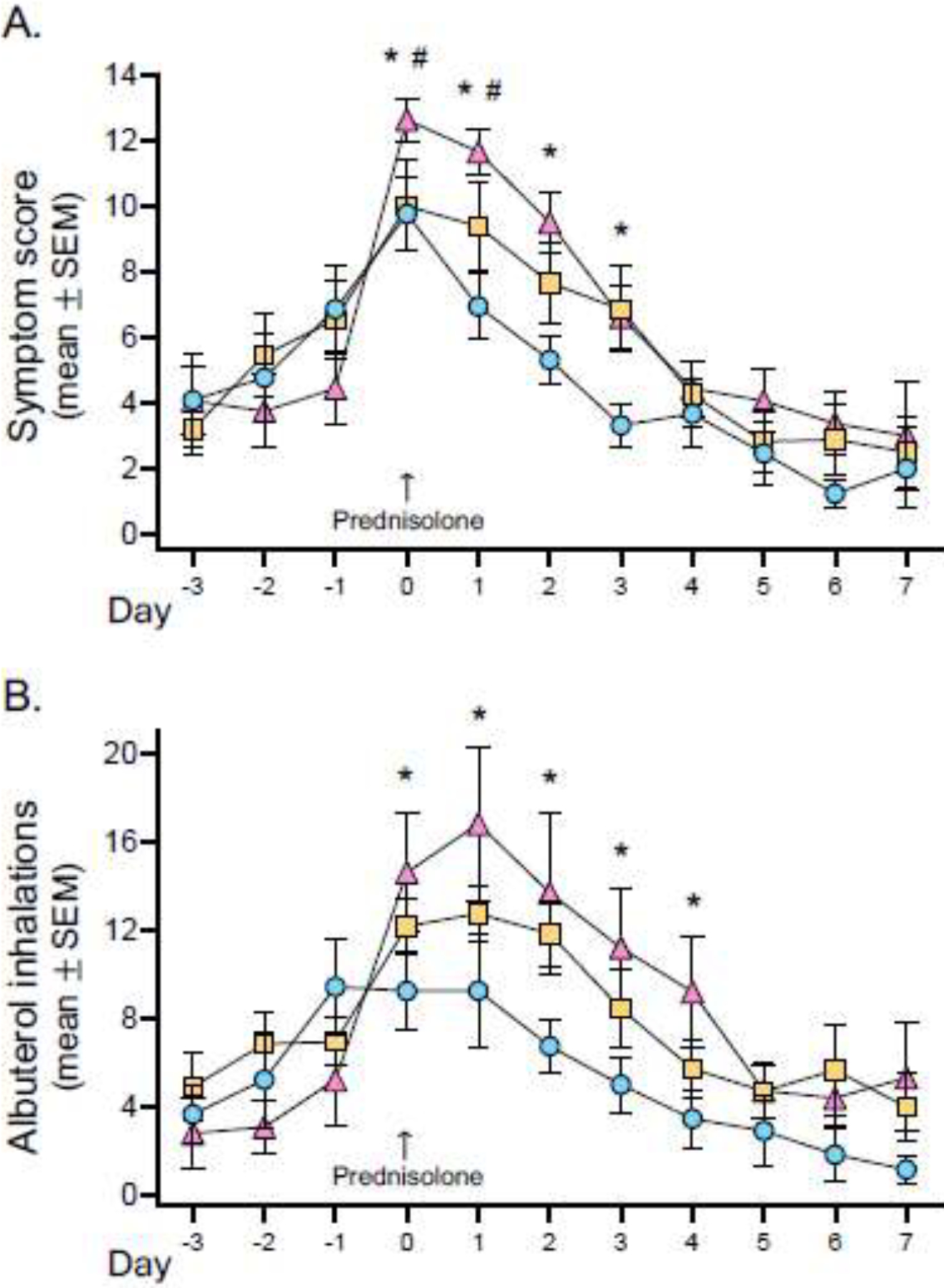

Exacerbation severity in children.

Eighty percent of caregivers submitted at least 3 consecutive weeks of completed diary cards for analysis (low risk, n=16 (84.2%); intermediate risk, n=23 (85.2%), high risk, n=24 (72.7%), p=0.420). Exacerbations treated with prednisolone were captured in 72 diary cards from 30 unique caregivers (low risk, n=10; intermediate risk, n=8; high risk, n=12). Symptom scores and albuterol use three days prior to the administration of prednisone and 7 days afterward are shown in Figure 3. Children at highest risk of social vulnerability had significantly higher symptom scores on the day of prednisolone administration and three days afterward (Figure 3A). Higher symptom scores were not attributed to lesser use of albuterol. Instead, children at highest risk of social vulnerability also received significantly more albuterol on the day of prednisolone administration and four days afterward (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Diary-reported (A) child symptom scores and (B) inhalations of albuterol sulfate over the course of an exacerbation treated with prednisolone in children at low risk (blue), intermediate risk (orange), and high risk (pink) of social vulnerability. *p<0.05 for high risk vs. low risk, #p<0.05 for high risk vs. intermediate risk.

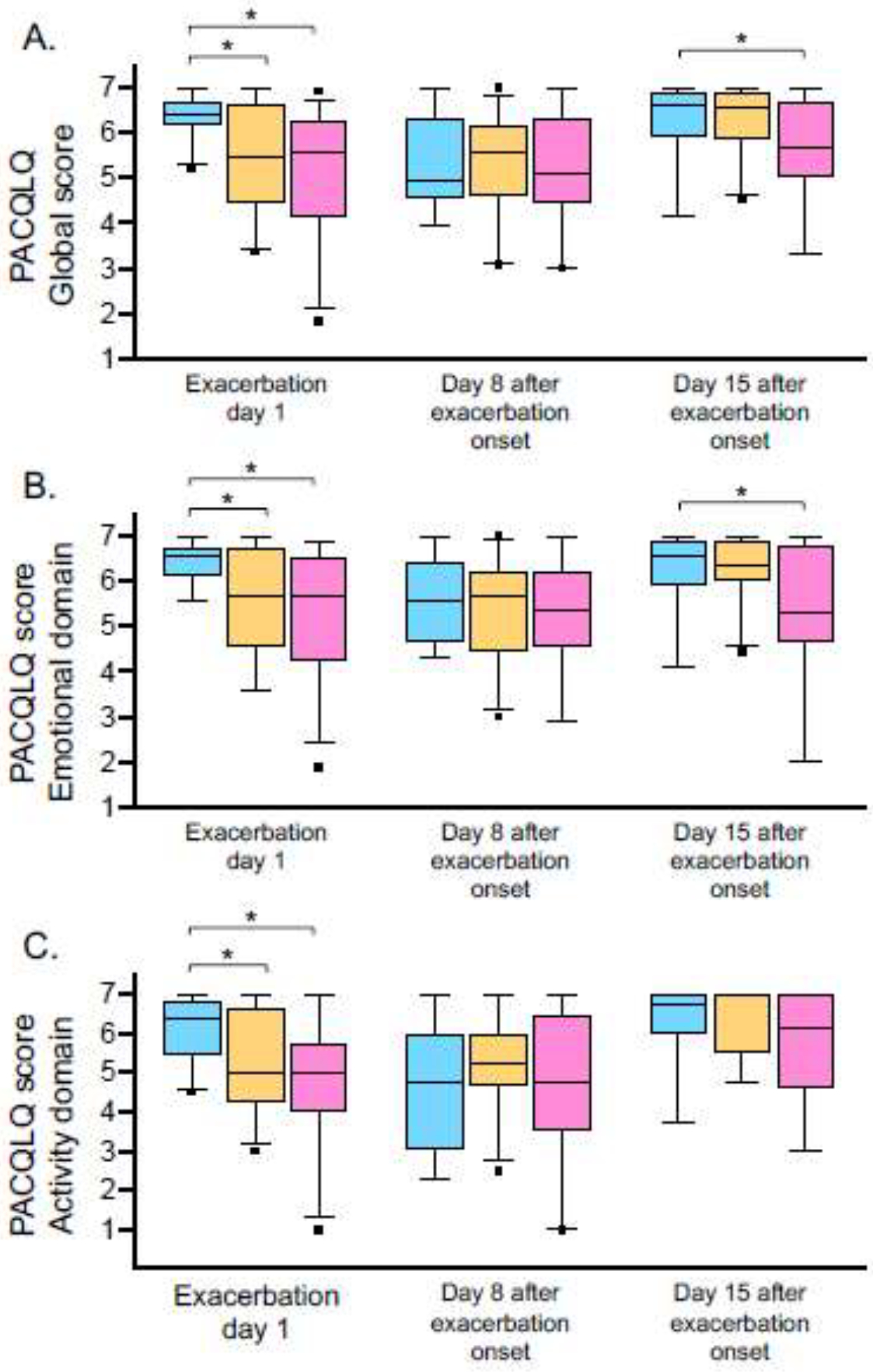

Caregiver quality of life during exacerbations.

Caregiver quality of life reflected by PACQLQ scores is shown in Figure 4. Caregivers at highest risk of social vulnerability reported significantly lower quality of life at the onset of the exacerbation that was related to emotional and activity functions. By exacerbation day 8, there were no differences between groups. However, by day 15, quality of life remained lower in high-risk caregivers, primarily due to impaired emotional functioning (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Pediatric asthma caregiver quality of life (PACQLQ) (A) global scores (B) emotional domain scores and (C) activity domain scores in caregivers at low risk (blue), intermediate risk (orange), and high risk (pink) of social vulnerability on exacerbation days one, six and fifteen. Boxplot lines and whiskers reflect the median and 5th-95th percentile, respectively. *p<0.05 for pairwise comparisons. Comparisons that are not marked are not statistically significant.

Exploratory analyses.

Given the limited number of variables utilized for risk stratification, exploratory analyses that were not pre-specified were performed with the original composite definition of social vulnerability utilized by Mutic et. al6 which included race, ethnicity, household education and income. The social vulnerability groupings of Mutic et. al6 correctly identified 94% of high risk children, 49% of intermediate risk children, and 69% of low risk children in the present study. This definition, as well as other individual variables, were then examined for their ability to discriminate child symptom scores, caregiver life satisfaction scores and exacerbation rates. Results are shown in eTable 2 and demonstrate that composite definitions of social vulnerability explain more variance in child symptoms and caregiver life satisfaction than single variable predictors.

Discussion

In this 12-month longitudinal study, we compared the symptom and exacerbation experiences of preschool children with recurrent wheezing and their caregivers in three groups of families at low, intermediate and high risk of social vulnerability based on a composite measure. Consistent with our hypothesis, we observed greater day-to-day symptom severity and more severe symptoms during acute exacerbations in high risk preschool children. High risk caregivers were also distinguished by lower general life satisfaction at all visits and lower global and emotional quality of life during acute exacerbations that did not improve with exacerbation resolution. Although there were no differences in rates of exacerbation or emergency department visits in this sample, perhaps due to the provision of emergency medications at study enrollment, intermediate and high risk families were significantly less likely to seek unscheduled outpatient care. Similar to other studies in adults and older children with asthma,2, 3 these findings highlight the influence of social determinants of health on wheezing outcomes in preschool children and argue for routine assessment of these factors during medical encounters. Although more studies are needed to understand the unique needs of high risk populations, these findings also argue for tailored interventions in high risk families to promote health equity and improve respiratory outcomes.

While the literature in this population is limited, our findings are aligned with those of other studies. Mutic et al.6 recently noted in a large, muti-center population that preschool children with recurrent wheezing at highest risk of social vulnerability did not have more frequent respiratory infections or exacerbations but instead had more severe exacerbations with significantly poorer caregiver quality of life. However, that study was conducted in a highly selected population of adherent children enrolled in multi-center clinical trials, with only 20% of the study population meeting criteria for high risk assignment.6 Although selection bias is still a potential issue in the present study, the enrolled population was largely representative of the local population served, which is 39% White, 36% Black, and 17% Hispanic. Our results are also aligned with studies that have shown impaired caregiver quality of life in preschool children with more severe wheezing7 and impaired caregiver functional status during acute exacerbations associated with emotions, concerns, and personal or family disruptions.8 However, unlike the latter study, our data highlight a unique population in which quality life and life satisfaction do not improve with exacerbation resolution.

In the present study, we did not observe associations with caregiver stress and depression and respiratory outcomes in preschool children, perhaps due to the small sample size. In a large multi-center birth cohort of children at high risk for asthma in low-income neighborhoods, maternal depression and perceived stress were associated with increased wheezing illnesses through the first three years of life.20, 21 This same study also noted a unique phenotype with a moderate degree of wheezing in preschool children characterized by lesser atopy.20 Although there were no differences in atopy in the present study, we were not powered to detect wheezing phenotypes. Furthermore, the proportion of children with aeroallergen sensitization in the present study was only 27%, which is markedly lower than in other preschool studies that ascertained phenotypes.22 23 Given our interest in exacerbation outcomes, we also limited our sample to children with at least one exacerbation requiring treatment with systemic corticosteroids in the previous year, which also limited the heterogeneity in our sample that may have been needed to detect other differences in caregiver-reported outcomes of mental and social health.

Strengths of the present study include the characterization of enrolled participants and the longitudinal design, which permitted assessment of symptoms both independent of and during acute exacerbations. However, this study also has limitations. First, we cannot rule out access to healthcare as a factor influencing our results. Although we tried to mitigate access to healthcare issues with the provision of rescue medications and action plans, the lower percentage of intermediate and high risk children who visited an outpatient physician for care was striking and suggests that healthcare access may differ between groups. This study was also affected by the COVID-19 pandemic between March and July of 2020, which may account for some of the variability in our results. Second, we did not measure health literacy, which could have influenced diary card interpretation. Third, social determinants of health are complex and multi-faceted.1 We did not measure many variables associated with health equity, such as systemic racism or other structural barriers which could impact care delivery.24, 25 We also caution extrapolation of these results to rural populations outside of those served by academic medical centers since material circumstances differ greatly. Fourth, we did not perform home visits and therefore cannot comment on whether poorer housing conditions or daily exposures differ in high risk families. Finally, is also unclear whether the patients in the high risk group were adequately treated with controller medications or if high risk caregivers had different concerns about the safety or efficacy of those medications. Other studies have also shown that self-assessment of asthma control may not align with physician assessments of control.26, 27

In summary, this study demonstrates that social determinants of health reflecting social vulnerability are associated with greater symptom burden in preschool children with recurrent wheezing and poorer general life satisfaction and quality of life in their caregivers. Although additional studies are needed to understand the unique factors associated with symptom management and healthcare utilization in high risk families, these results highlight the need for more comprehensive assessment of social determinants of health, health literacy, and access to care in routine health encounters as an essential first step to improve health equity. These results also argue for development of interventions tailored to the unique needs of high risk families to improve respiratory outcomes in their preschool children.

Supplementary Material

Funding source:

R01 NR017939, K24 NR018866, and UL1 TR002378

Abbreviations:

- PACQLQ

Pediatric Asthma Caregiver’s Quality of Life Questionnaire

- PROMIS

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

- TRACK

Test for Respiratory and Asthma Control in Kids

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Anne M. Fitzpatrick, Tricia Lee, Brian P. Vickery, Elizabeth Alison Corace, Carrie Mason, Jalicae Norwood, Cherish Caldwell, and Jocelyn R. Grunwell have no disclosures or conflicts of interest pertaining to the submitted work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Social determinants of health. Available online at http://who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1. Last accessed February 20, 2023.

- 2.Espaillat AE, Hernandez ML, Burbank AJ. Social determinants of health and asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant T, Croce E, Matsui EC. Asthma and the social determinants of health. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2022; 128:5–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most Recent National Asthma Data. Available online at http://cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm. Last accessed February 20, 2023.

- 5.Pate CA, Zahran HS, Qin X, Johnson C, Hummelman E, Malilay J. Asthma Surveillance - United States, 2006–2018. MMWR Surveill Summ 2021; 70:1–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mutic AD, Mauger DT, Grunwell JR, Opolka C, Fitzpatrick AM. Social Vulnerability Is Associated with Poorer Outcomes in Preschool Children With Recurrent Wheezing Despite Standardized and Supervised Medical Care. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022; 10:994–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleming L, Murray C, Bansal AT, Hashimoto S, Bisgaard H, Bush A, et al. The burden of severe asthma in childhood and adolescence: results from the paediatric U-BIOPRED cohorts. Eur Respir J 2015; 46:1322–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen ME, Mendelson MJ, Desplats E, Zhang X, Platt R, Ducharme FM. Caregiver’s functional status during a young child’s asthma exacerbation: A validated instrument. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 137:782–8 e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts. Available online at http://census.gov/quickfacts. Last accessed February 3, 2023.

- 10.Grunwell JR, Opolka C, Mason C, Fitzpatrick AM. Geospatial Analysis of Social Determinants of Health Identifies Neighborhood Hot Spots Associated With Pediatric Intensive Care Use for Life-Threatening Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022; 10:981–91 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Najjar N, Opolka C, Fitzpatrick AM, Grunwell JR. Geospatial Analysis of Social Determinants of Health Identifies Neighborhood Hot Spots Associated With Pediatric Intensive Care Use for Acute Respiratory Failure Requiring Mechanical Ventilation. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2022; 23:606–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diversitydatakids.org. 2023. Child Opportunity Index 2.0 database. Available online at http://data.diversitydatakids.org/dataset/coi20-child-opportunity-index-2-0-database?_external=True. Last accessed March 27, 2023.

- 13.Santanello NC, Demuro-Mercon C, Davies G, Ostrom N, Noonan M, Rooklin A, et al. Validation of a pediatric asthma caregiver diary. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000; 106:861–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Ferrie PJ, Griffith LE, Townsend M. Measuring quality of life in the parents of children with asthma. Qual Life Res 1996; 5:27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy KR, Zeiger RS, Kosinski M, Chipps B, Mellon M, Schatz M, et al. Test for respiratory and asthma control in kids (TRACK): a caregiver-completed questionnaire for preschool-aged children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 123:833–9 e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeiger RS, Mellon M, Chipps B, Murphy KR, Schatz M, Kosinski M, et al. Test for Respiratory and Asthma Control in Kids (TRACK): clinically meaningful changes in score. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 128:983–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol 2010; 63:1179–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuhlbrigge A, Peden D, Apter AJ, Boushey HA, Camargo CA Jr., Gern J, et al. Asthma outcomes: exacerbations. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 129:S34–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holland A, Smith F, Penny K, McCrossan G, Veitch L, Nicholson C. Metered dose inhalers versus nebulizers for aerosol bronchodilator delivery for adult patients receiving mechanical ventilation in critical care units. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 2013:CD008863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramratnam SK, Lockhart A, Visness CM, Calatroni A, Jackson DJ, Gergen PJ, et al. Maternal stress and depression are associated with respiratory phenotypes in urban children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021; 148:120–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramratnam SK, Visness CM, Jaffee KF, Bloomberg GR, Kattan M, Sandel MT, et al. Relationships among Maternal Stress and Depression, Type 2 Responses, and Recurrent Wheezing at Age 3 Years in Low-Income Urban Families. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 195:674–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitzpatrick AM, Bacharier LB, Guilbert TW, Jackson DJ, Szefler SJ, Beigelman A, et al. Phenotypes of Recurrent Wheezing in Preschool Children: Identification by Latent Class Analysis and Utility in Prediction of Future Exacerbation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019; 7:915–24 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bacharier LB, Beigelman A, Calatroni A, Jackson DJ, Gergen PJ, O’Connor GT, et al. Longitudinal Phenotypes of Respiratory Health in a High-Risk Urban Birth Cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 199:71–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burbank AJ, Hernandez ML, Jefferson A, Perry TT, Phipatanakul W, Poole J, et al. Environmental justice and allergic disease: A Work Group Report of the AAAAI Environmental Exposure and Respiratory Health Committee and the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Committee. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okelo SO. Structural Inequities in Medicine that Contribute to Racial Inequities in Asthma Care. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2022; 43:752–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuhlbrigge A, Marvel J, Electricwala B, Siddall J, Scott M, Middleton-Dalby C, et al. Physician-Patient Concordance in the Assessment of Asthma Control. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021; 9:3080–8 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yawn BP, Israel E, Wechsler ME, Pace W, Madison S, Manning B, et al. The asthma Symptom Free Days Questionnaire: how reliable are patient responses? J Asthma 2019; 56:1222–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.