Abstract

Background:

Donor-derived cell-free DNA (dd-cfDNA) testing is an emerging screening modality for noninvasive detection of acute rejection (AR). This study compared the testing accuracy for AR of two commercially available dd-cfDNA and gene-expression profiling (GEP) testing in heart transplant (HTx) recipients.

Methods:

This is a retrospective, observational study of HTx only patients who underwent standard and expanded single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) dd-cfDNA between October 2020 to January 2022. Comparison with GEP was also performed. Assays were compared for correlation, accurate classification, and prediction for AR.

Results:

A total of 428 samples from 112 unique HTx patients were used for the study. A positive standard SNP correlated with the expanded SNP assay (p < .001). Both standard and expanded SNP tests showed low sensitivity (39%, p = 1.0) but high specificity (82% and 84%, p = 1.0) for AR. GEP did not improve sensitivity and showed worse specificity (p < .001) compared to standard dd-cfDNA.

Conclusion:

We found no significant difference between standard and expanded SNP assays in detecting AR. We show improved specificity without change in sensitivity using dd-cfDNA in place of GEP testing. Prospective controlled studies to address how to best implement dd-cfDNA testing into clinical practice are needed.

Keywords: acute cellular rejection, acute rejection, antibody mediated rejection, biomarker, cell-free DNA, dd-cfDNA, endomyocardial biopsy, gene expression profiling, heart transplant

1 ∣. BACKGROUND

Surveillance and early detection of acute cellular rejection (ACR) and antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) are important determinants of treatment outcomes, transplant longevity, and patient survival.1 Currently, the reference standard of detecting acute rejection (AR) is an endomyocardial biopsy (EMB). This procedure is costly, invasive, and potentially associated with complications.2 There is strong interest in the heart transplant (HTx) community to find a non-invasive test that accurately detects and predicts AR.

Donor-derived cell-free DNA (dd-cfDNA) from peripheral blood has received growing attention as a biomarker of HTx rejection and has been suggested for possible use for AR surveillance by the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) and the American Society of Transplantation (AST).3,4 Cardiomyocytes damaged from AR release circulating DNA into the bloodstream that can now be measured to a high degree of sensitivity. Correlation between increased dd-cfDNA levels and AR was first shown by Snyder and colleagues using shotgun whole-genome sequencing.5 Subsequent prospective cohort studies clinically validated the use of dd-cfDNA in screening for AR in HTx recipients.6,7 Targeted amplification next-generation sequencing (NGS) significantly reduced the cost of dd-cfDNA testing that allowed for its routine use for AR detection. The standard SNP test examined in this study (AlloSure®; CareDx; Brisbane, California) was the first dd-cfDNA assay licensed for clinical use for noninvasive detection of AR in HTx patients and uses a 405 SNP panel.8 The expanded SNP test (Prospera™; Natera; Austin, Texas) is a dd-cfDNA assay that utilizes 13,292 highly polymorphic SNPs and has also been clinically validated.9 However, with the continued evolution in dd-cfDNA technology, clinical utility of dd-cfDNA may be critically influenced by technical and interpretive aspects of these assays.

Thus, this study evaluates the hypothesis that the standard SNP correlates with the expanded SNP assay, and despite the apparent technical differences, that both dd-cfDNA tests perform similarly with regards to screening performance for AR. While both assays have been compared in two studies of kidney transplant patients,10,11 this is a larger study that compares the two dd-cfDNA tests specifically in the clinical practice of HTx. Additionally, we compare the testing accuracy of GEP versus standard and expanded dd-cfDNA testing for ACR.

2 ∣. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 ∣. Data sharing

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Mendeley Data at 10.17632/cpyj7v99rj.2.12

2.2 ∣. Study design

This was a retrospective, observational study of HTx patients at the University of California, San Diego Health (UC San Diego Health) who had an EMB and both standard and expanded SNP dd-cfDNA testing in the 14 days preceding the EMB. Inclusion of an EMB performed within 14 days is based on previous literature and it also represents real world practice.13,14 Eligible subjects were HTx only recipients, 18 years of age or older, and at least 28 days post-HTx. Samples were collected from October 2020 to January 2022. Standard SNP testing refers to the use of a 405 SNP panel performed by CareDx (Brisbane, California) as part of clinical care at UC San Diego Health since October 2020. Expanded SNP testing refers to the use of a 13,292 SNP panel performed by Natera (Austin, Texas) for a separate research study for which patients had provided informed consent.9 Both standard and expanded SNP testing are CLIA (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment) certified but not FDA approved as standalone tests. Both dd-cfDNA tests are covered by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) as of March 31st, 2023. During the period of this study, our protocol was to obtain standard SNP testing with surveillance EMBs to establish an appropriate threshold for performing EMB at UC San Diego Health. Thus, treatment was based on EMB results and not dd-cfDNA results. The clinical protocol for induction, steroid taper, and treatment of AR at UC San Diego Health is provided in the Appendix. As a result, we currently utilize .15% as the cutoff value for the standard SNP testing. The expanded SNP testing uses also a .15% cutoff as previously described.9 Both for cause and surveillance EMBs were included in the study cohort. Demographic and clinical data were collected for all patients. Approval for this study was provided by the UC San Diego Health Office of IRB Administration (IRB #803607). This study adheres to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki formulated by the World Medical Association and the US Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects.

GEP testing (AlloMap®; CareDx; Brisbane, California) was also performed as part of clinical care and evaluated in this study. This test has been given FDA 510(k) clearance to aid in the identification of adult HTx patients who are at low risk for moderate/severe ACR. GEP testing is recommended after 55 days from HTx for ACR surveillance.15 GEP testing was considered positive if the score was > = 30 between 2 and 6 months post-HTx or > = 34 after 6 months post-HTx.16,17

2.3 ∣. Biopsy-defined rejection

We followed the ISHLT classification scheme and defined ISHLT grades 2R and 3R as clinically significant ACR and ISHLT grades pAMR1(H+ or I+), pAMR2 and pAMR3 as clinically significant AMR.18,19 AR refers to either clinically significant ACR, AMR, or both (mixed ACR and AMR).

2.4 ∣. Clinical outcomes

All HTx patients were followed for all-cause death. Cause of death was determined by review of the clinical charts by an experienced HTx cardiologist (PK).

2.5 ∣. Statistical analyses

The primary analysis was to compute the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) for the biomarker assays as screening tests for AR. To account for intraclass correlation related to multiple tests per patient, we implemented hierarchical bootstrapping; an equal number of patients as in our study was sampled at random with replacement, and then for each sampled patient the same number of observations for this patient as in the original dataset was sampled with replacement. This process was repeated 10,000 times, in order to generate approximate sampling distributions for the statistics of interest. The mean and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each statistic were taken from the bootstrap sampling distribution. The p-value of the comparison between assays is based on the tail probability of the value of 0 (no difference) in the bootstrap distribution of the difference statistic, multiplied by two (two-tailed test). Number of AR, AMR, ACR, and positive biomarker assays were also calculated by performing hierarchical bootstrapping and repeating this 10,000 times.

The correlation of standard and expanded SNP assays was evaluated using mixed-effects logistic regression, with participant-specific random effects, to account for repeated measures within patients. The standard and expanded SNP test results were dichotomized to above or below the lower limit of quantitation, with cutoff values for both assays being .15%.8,9,16 The agreement rate between standard and expanded SNP was also analyzed by Cohen’s kappa statistics. Mixed effects logistic regression with participant-specific random effects was performed to identify potential co-predictors of AR, in addition to dd-cfDNA and GEP assay results as primary predictors. Forward model selection using a p-value less than .15 threshold was used to identify potential co-predictors.

Fisher’s exact test was used for comparing independent proportions of cytomegalovirus (CMV) viremia in the EMB negative cases with GEP testing.

Analysis was conducted in R (RCore Team, 2022) with lme4 package for mixed effect modeling (v1.1-28)20 and fmsb package for Cohen’s kappa (v0.7.5).21 Figures were produced using the package ggplot2 (v3.3.5).22 We used the Bonferroni-Holm procedure whenever multiple comparisons were performed while implementing a particular statistical hypothesis test. The corrected p values are designated as pc. For single hypothesis testing we report the unadjusted p value. P or pc < .05 are considered significant.

3 ∣. RESULTS

3.1 ∣. Characteristics of study population

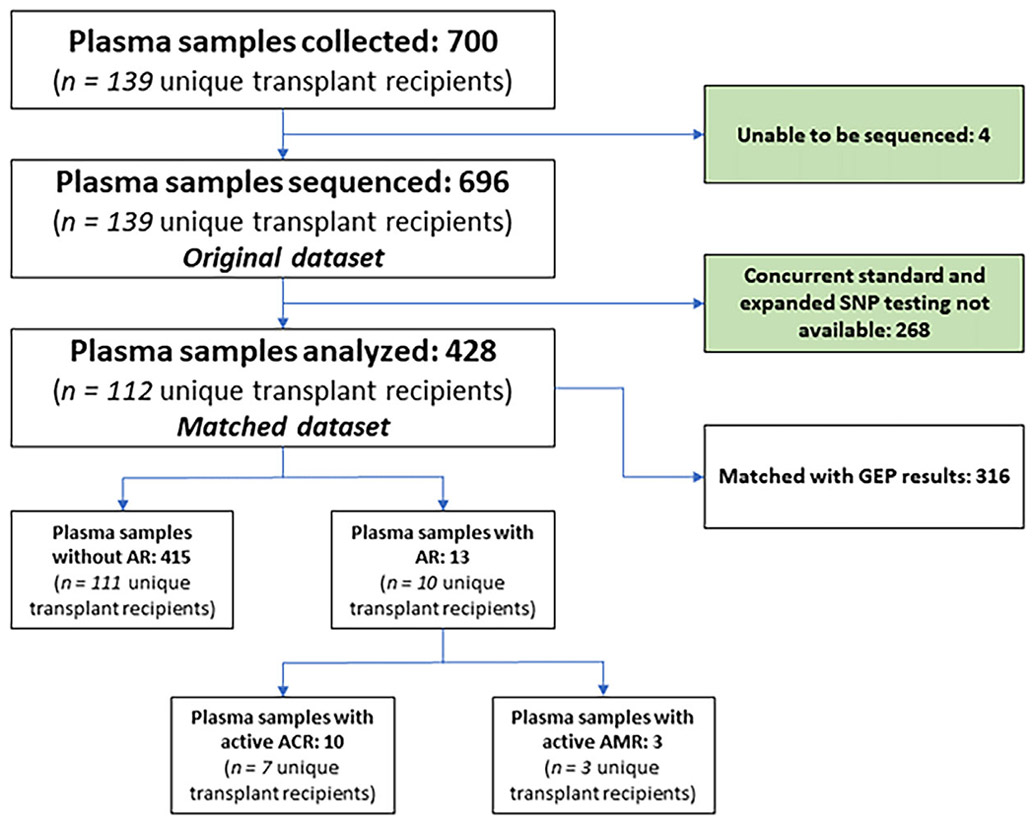

A total of 700 samples from 139 unique HTx patients with expanded SNP testing and contemporaneous EMB were eligible for the study (Figure 1). Expanded SNP testing was not able to be measured in four samples because of either loss of sample in transportation (n = 2) or low-quality reads (n = 2). Of the remaining 696 samples (original dataset), we identified 428 samples from 112 unique HTx patients (matched dataset) with standard SNP testing performed within 14 days preceding the EMB. Within these 428 samples, 316 (73.8%) also had a corresponding GEP result.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram. AR, acute rejection; ACR, acute cellular rejection; AMR, antibody-mediated rejection.

Patients were predominantly male (77.7%) and white (40.2%) with a median age of 60.0 years (IQR, 46.8-65.3 years; Table 1). The most reported indication for HTx was non-ischemic cardiomyopathy (67.9%). Median time from HTx to EMB was 114 days (IQR, 65-200 days). Median time difference between standard and expanded SNP testing was 1 day (IQR, 0-7 days; Figure S1). There were 187 person-years in this study from subject enrollment to end of follow-up. The observed AR prevalence was 3.0%, which also matched our bootstrap prevalence (Table S1). Table S2 summarizes the clinical information relevant for the 13 samples associated with AR. We observed higher prevalence of ACR (2.3%) compared to AMR (.7%) in our cohort.

TABLE 1.

Subject clinical characteristics.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 112 |

|

| |

| Gender | |

| Male | 87 (77.7%) |

| Female | 25 (22.3%) |

|

| |

| Age (years) | 60.0 (IQR, 46.8-65.3) |

|

| |

| Body mass index | 26.8 (IQR, 23.8-30.8) |

| Race | |

| Asian | 15 (13.4%) |

| Black | 16 (14.3%) |

| Native American | 2 (1.8%) |

| Other Race | 32 (28.6%) |

| Pacific Islander | 2 (1.8%) |

| White | 45 (40.2%) |

|

| |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 27 (24.1%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 85 (75.9%) |

|

| |

| Indication for transplant | |

| Nonischemic cardiomyopathy | 76 (67.9%) |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 30 (26.8%) |

| Congenital | 3 (2.7%) |

| Retransplant | 3 (2.7%) |

|

| |

| Panel-reactive Antibodies (PRA) | |

| Sensitized patients (PRA ≥ 10%) | 14 (12.5%) |

| Unsensitized patients (PRA < 10%) | 97 (86.6%) |

| Missing | 1 (.9%) |

|

| |

| Durable ventricular assist device pre-transplant | |

| Yes | 26 (23.2%) |

| No | 86 (76.8%) |

3.2 ∣. Association of standard with expanded SNP testing

We observed 323 (75.5%) samples at or below the limit of quantitation for standard and 140 (32.7%) samples for expanded SNP testing. Due to the high proportion of observations at or below the limit of quantitation, we assessed correlation of standard with expanded SNP testing using cutoff values of .15% for both assays.8,9,16 Table S3 shows cross-tables of the biomarker assays compared to AR diagnosis by EMB. We found a positive standard SNP result correlated with a positive expanded SNP result with an odds ratio (OR) of 54.0 (23.3, 125.5; p < .001; Figure 2). Consistent with this finding, we found standard and expanded SNP to show substantial agreement with a Cohen’s kappa of .69 (.59, .78; p < .001). Sensitivity analysis restricting the matched samples to 3 days time difference (n = 280 samples),8,23 also showed strong correlation that was statistically significant (p < .001) with a Cohen’s kappa of .74 (p < .001). We also found the standard and expanded dd-cfDNA tests to be concordant in 11 out of 13(85%) positive AR samples and did not find a significant difference in paired proportions using the McNemar test (p = 1.0).

FIGURE 2.

Scatter plot of standard and expanded single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) donor derived cell-free DNA (dd-cfDNA) tests. Values are log-transformed to provide a normal distribution. Blue dashed lines represent the log-transformed prespecified cutoff values (−1.9%) for the standard and expanded SNP tests. The black dashed line shows the regression line. There is a linear relationship seen for the standard and expanded SNP tests. Acute rejection (AR) samples are identified in red. A sharp demarcation is seen for the standard and expanded SNP tests in the bottom-left of the scatterplot due to the respective lower limits of quantitation for each test.

3.3 ∣. Test performance to detect AR

Both standard and expanded SNP dd-cfDNA tests showed no significant difference in testing accuracy for AR (Table S4). Sensitivity with standard SNP was 39% and expanded SNP testing also 39% (p = .66). Specificity with standard SNP was 82% and expanded SNP testing 84% (p = .26). PPV with standard SNP was 6.2% and expanded SNP testing 7.0% (p = .70). NPV with standard and expanded SNP testing were both 98% (p = .76).

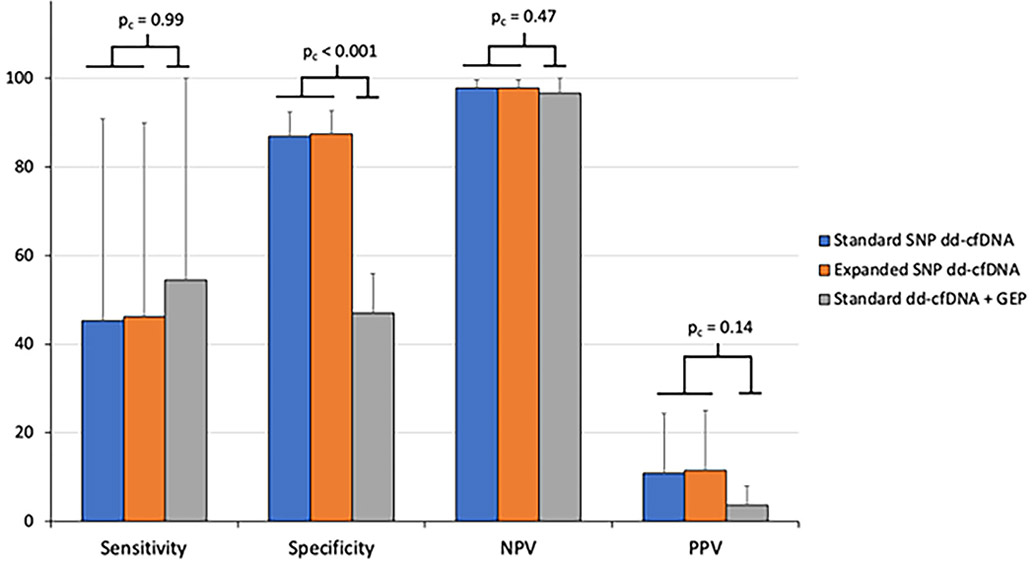

Furthermore, we evaluated the screening performance of combining GEP with standard SNP testing (standard dd-cfDNA + GEP), commercially packaged as HeartCare® (CareDx; Brisbane, California; Figure 3).15,24 Standard dd-cfDNA + GEP testing was considered positive if either standard dd-cfDNA or GEP tests were at or above the established cutoffs. We found specificity of standard dd-cfDNA + GEP was 47%, which was significantly lower when compared to either standard or expanded SNP dd-cfDNA tests individually (pc < .001).

FIGURE 3.

Barchart of sensitivity, specificity, NPV and PPV for standard and expanded SNP dd-cfDNA and standard dd-cfDNA + GEP tests. A subset (n = 316 samples) of the matched dataset was used for comparison with standard dd-cfDNA + GEP (i.e., HeartCare®) testing. Hierarchical bootstrapping was used to determine the mean and 95% confidence interval for each statistic. Sensitivity is not significantly different for the three tests. Standard dd-cfDNA + GEP shows significantly lower specificity compared to both standard and expanded SNP dd-cfDNA tests. Standard dd-cfDNA + GEP demonstrates a trend towards decreased PPV compared to standard or expanded SNP tests used individually. NPV is not significantly different for the three tests. dd-cfDNA, donor derived cell-free DNA; GEP, gene expression profiling; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Evaluating GEP for detection of ACR (Table S5), we showed GEP specificity was significantly lower than standard SNP dd-cfDNA (pc < .001) but otherwise did not show a significant difference for sensitivity, PPV, and NPV for detection of ACR. Although there was a trend for increased prevalence of cytomegalovirus (CMV) viremia in the EMB negative, GEP positive (4.2%) versus EMB negative, GEP negative cases (1.9%), this was not statistically significant (p = .32). Standard dd-cfDNA + GEP similarly showed significantly reduced specificity versus standard SNP testing alone for detection of ACR (pc < .001).

Using mixed-effects logistic regression with forward model selection, we observed that the subject’s age, race and ethnicity, history of either ACR or AMR, and number of months since HTx were also important co-predictors of AR with either standard or expanded SNP dd-cfDNA testing as the primary predictor (Table S6). However, a positive standard dd-cfDNA + GEP result was not predictive for AR.

3.4 ∣. Clinical outcomes

For clinical outcomes, we observed 8 (7.1%) deaths (Table S7 and Figure S2). The majority (50%) of deaths were due to infection or cancer. AR accounted for 25% of deaths. One AR episode associated with death was positive for both standard and expanded SNP testing while the other AR episode did not undergo dd-cfDNA testing.

4 ∣. DISCUSSION

The main finding of our study is that the results of both dd-cfDNA tests, standard and expanded SNP, were significantly correlated and did not show significant difference in the noninvasive detection of AR in HTx patients. In addition, we found significantly reduced specificity without improved sensitivity with the addition of GEP to dd-cfDNA testing. To the best of our knowledge, this is also the first study, outside of the sponsored CARGO II and OAR registries, to provide matched GEP and EMB results for evaluation of testing accuracy.

Expanded differs from the standard SNP assay by utilizing more 10,000+ more SNPs, with the potential benefit of achieving sufficient genetic diversity between donor and recipient DNA to enable confident differentiation of DNA source without a priori knowledge of donor and recipient genotypes. Though use of additional SNPs may have bioinformatic applications beyond the scope of this study, these technical differences do not show a direct impact on discrimination of AR in HTx patients in this study.

Though the specificity for detection of AR as compared to histopathology was high, sensitivity for both dd-cfDNA tests was relatively low. The sensitivity was lower compared to some previously published studies but similar to others.6-9 Agbor-Enoh used shotgun sequencing which is a very different technique from targeted NGS that both standard and expanded SNP testing utilize. Apart from technique, the differences in testing accuracy are also explained by the different prevalence of AMR for the studies as dd-cfDNA testing better detects AMR compared to ACR.7-9,25

The prevalence of AR in our matched cohort is comparable to 25% rejection prevalence observed in recent literature.7,8,14 The low AR prevalence in the current era is attributed to modern immunosuppression and improved post-HTx care.7,8,16,26 Additionally, it was reassuring to see the majority of the deaths in our matched cohort were not due to AR. This is consistent with recent literature showing low mortality due to AR in the current era.13,14 Of note, at UCS an Diego Health, a weekly pathologic review of all EMB samples are performed by a panel of three anatomic pathologists, led by our senior pathologist, in addition to our HTx cardiologist group for more consistent pathologic reads. This practice has been in place at our institution since 2012 in response to the known interobserver variability for the pathologic diagnosis of AR.27 It is likely that even this structured approach does not fully mitigate some of the diagnostic limitations of histopathology.

Because of the low prevalence of AR, the NPV without testing already starts very high at 97% in our study and 98.4% in a recent large, multi-center observational study.14 The low PPV has also been observed in other recent studies for dd-cfDNA.13,28,29 In our study, the probability of rejection for the expanded SNP assay moves from 3.0% pretest to 7.5% post-test for a positive test and 2.2% post-test for a negative test. As a result, in the setting of low AR prevalence, the value of dd-cfDNA testing is mostly derived from the high specificity. Thus, for the current commercial methodology of targeted NGS that quantifies dd-cfDNA as a percentage of total circulating cell-free DNA, we do not find clinically meaningful differences between the standard or expanded SNP panel. Additional test modifications such as the use of dd-cfDNA absolute quantity9,30 may result in further increase in testing accuracy and would be of interest to evaluate in future studies.

We also evaluated the use of standard dd-cfDNA + GEP (Heart-Care®, CareDx; Brisbane, California) as they are recommended to be used together to utilize both the superior detection of AMR by dd-cfDNA and the specific development of GEP for detecting ACR.15,31 However, we found significantly decreased specificity compared to either standard or expanded SNP dd-cfDNA tests alone. This was due to a significant decrease in specificity for ACR by GEP testing, which was also observed in the OAR registry.14 Thus, we did not find any benefit for detection of ACR with GEP on top of dd-cfDNA testing. Recently, Henricksen and coauthors showed similar survival with dd-cfDNA + GEP testing compared to GEP alone.13 However, our findings suggest that dd-cfDNA testing, without GEP, is sufficient. The use of dd-cfDNA testing alone would also provide more flexibility as blood samples can be obtained at the patient’s home due to the stability of cell-free DNA at room temperature for up to 14 days.15

With low AR prevalence and incidence of deaths from AR, we believe there is clinical equipoise that allows future prospective randomized control trials to address how to best implement dd-cfDNA testing into clinical practice for HTx. The noninvasive surveillance strategy of expanded dd-cfDNA testing alone will be evaluated in an upcoming clinical trial (NCT05081739: DETECT). Another study (NCT05459181: MOSAIC) plans to study whether standard dd-cfDNA + GEP testing can guide decrease in overall immunosuppression and minimization of tacrolimus in a low risk HTx population.

4.1 ∣. Limitations

Limitations of this study include: (1) This was a retrospective study from a single center and may not necessarily represent the experience of other centers with a different patient demographic. In particular, black patients are underrepresented in our study population compared to the UNOS database in the current era.32 However, the AR prevalence remained low (4.4%) with a 44% black patient cohort in a recent study.7 (2) The vast majority of samples obtained for this study were drawn early post-HTx with a median sample time of 114 days from HTx. Thus, conclusions from samples obtained further out from HTx cannot be confidently made. (3) The time difference between standard and expanded SNP testing may also be a confounding variable. However, the median time difference was only 1 day in our study and we found similar results in our sensitivity analysis restricting the sample time difference to 3 days. (4) Despite the larger number of samples used, our study remains underpowered to detect smaller differences between standard and expanded SNP testing that may exist. (5) The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV calculated for standard dd-cfDNA + GEP were performed on a 316-sample subset of the matched dataset. Although this still accounted for 74% of the matched dataset, selection bias is a potential confounder in the analysis of the results. (6) This study utilized cutoffs recommended by previous studies or based on UC San Diego Health’s experience, and it is possible that clinicians will eventually adopt more nuanced cutoffs based on the clinical context of individual patients.

5 ∣. CONCLUSION

This study shows there is no significant difference in testing accuracy for AR in HTx patients when comparing standard and expanded SNP dd-cfDNA tests. We also show significantly improved specificity without reducing sensitivity for AR using dd-cfDNA testing only versus dd-cfDNA + GEP testing.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Altman Clinical & Translational Research Institute (ACTRI) at UC San Diego Health (PJK). The ACTRI is funded from awards issued by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH KL2TR001444 and NIH UL1 TR001442.

APPENDIX

| Induction protocol | Selective induction therapy based on PRA, renal insufficiency (i.e., glomerular filtration rate < 40 ml/min), or African American race and age < 40 years old but ultimately per heart transplant cardiologist’s discretion. Usual dosing is thymoglobulin 1.0 mg/kg/day IV for 3 days. |

| Prednisone taper protocol post-heart transplant | First 2 weeks: 50 mg PO bid, taper by 10 mg/day daily until 20 mg total daily dose 1 month: 15 mg PO daily 6 weeks: 12.5 mg PO daily 2 months: 10 mg PO daily 3 months: 7.5 mg PO daily 4 months: 5 mg PO daily 5 months: 2.5 mg PO daily 6 months: discontinue May deviate from protocol based on patient specific factors, including AR, DSA, and infection. |

| ACR treatment, hemodynamically stable (normal echocardiogram and asymptomatic) | Prednisone 1.0 mg/kg/day PO for 5 days (maximum of 100 mg total daily dose) with taper of 30% per day back to baseline prednisone dose. Consider augmentation of baseline immunosuppression. |

| ACR treatment, hemodynamically unstable (abnormal echocardiogram, hemodynamics and/or symptoms of rejection) | Methylprednisolone 1 gram/day IV for 3 days followed by prednisone taper (see ACR treatment, hemodynamically stable) back to baseline prednisone dose. Thymoglobulin may be given in select cases based on severity of ACR or if the patient has had recurrent ACR. Consider augmentation of baseline immunosuppression. |

| AMR treatment (pAMR1-3) | Hemodynamically unstable:

|

Abbreviations: ACR, acute cellular rejection; AMR, antibody-mediated rejection; AR, acute rejection; DSA, donor specific antibody; IV, intravenous; IVIG, intravenous immunglobulin therapy; pAMR, pathological antibody-mediated rejection; PO, per os; PRA, panel reactive antibodies.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

PJK reports having received payments from CareDx and Natera for consulting and working at an institution that received research payments from CareDx and Natera. JS reports receiving payments from Natera for consulting and working at an institution that received research payments from Natera. Neither CareDx nor Natera were involved in the conceptualization of the study, data collection and analysis, manuscript preparation, and editing of the final manuscript.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Mendeley Data at https://doi.org/10.17632/cpyj7v99rj.2.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jaramillo N, Segovia J, Gómez-Bueno M, et al. Characteristics of patients with survival longer than 20 years following heart transplantation. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2013;66(10):797–802. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2013.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jamil AK, Afzal A, Nisar T, et al. Trends in post-heart transplant biopsies for graft rejection versus nonrejection. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2021;34(3):345–348. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2021.1873032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Velleca A, Shullo MA, Dhital K, et al. The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) guidelines for the care of heart transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2022.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobashigawa J, Hall S, Shah P, et al. The evolving use of biomarkers in heart transplantation: consensus of an expert panel. Am J Transplant. 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.ajt.2023.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snyder TM, Khush KK, Valantine HA, Quake SR. Universal noninvasive detection of solid organ transplant rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(15):6229–6234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013924108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Vlaminck I, Valantine HA, Snyder TM, et al. Circulating cell-free DNA enables noninvasive diagnosis of heart transplant rejection. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(241):241ra77. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agbor-Enoh S, Shah P, Tunc I, et al. Cell-free DNA to detect heart allograft acute rejection. Circulation. 2021;143(12):1184–1197. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.049098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khush KK, Patel J, Pinney S, et al. Noninvasive detection of graft injury after heart transplant using donor-derived cell-free DNA: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(10):2889–2899. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim PJ, Olymbios M, Siu A, et al. Absolute quantification of donor derived cell free DNA in heart transplant patients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2022;41(4):S116. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2022.01.270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melancon JK, Khalil A, Lerman MJ. Donor-derived cell free DNA: is it all the same? Kidney360.2020;1(10):1118–1123. doi: 10.34067/KID.0003512020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lum EL, Nieves-Borrero K, Homkrailas P, Lee S, Danovitch G, Bunnapradist S. Single center experience comparing two clinically available donor derived cell free DNA tests and review of literature. Transplant Rep. 2021;6(3):100079. doi: 10.1016/j.tpr.2021.100079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim NRA, dd-cfDNA and GEP in heart-transplantation. 2023. doi: 10.17632/cpyj7v99rj.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henricksen EJ, Moayedi Y, Purewal S, et al. Combining donor derived cell free DNA and gene expression profiling for non-invasive surveillance after heart transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2023;37(3):e14699. doi: 10.1111/ctr.14699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moayedi Y, Foroutan F, Miller RJH, et al. Risk evaluation using gene expression screening to monitor for acute cellular rejection in heart transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019;38(1):51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2018.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holzhauser L, DeFilippis EM, Nikolova A, et al. The end of endomyocardial biopsy?: A practical guide for noninvasive heart transplant rejection surveillance. JACC Heart Fail. 2023;11(3):263–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2022.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crespo-Leiro MG, Stypmann J, Schulz U, et al. Clinical usefulness of gene-expression profile to rule out acute rejection after heart transplantation: CARGO II. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(33):2591–2601. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pham MX, Teuteberg JJ, Kfoury AG, et al. Gene-expression profiling for rejection surveillance after cardiac transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(20):1890–1900. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart S, Winters GL, Fishbein MC, et al. Revision of the 1990 working formulation for the standardization of nomenclature in the diagnosis of heart rejection. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24(11):1710–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berry GJ, Burke MM, Andersen C, et al. The 2013 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Working Formulation for the standardization of nomenclature in the pathologic diagnosis of antibody-mediated rejection in heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32(12):1147–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67:1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakazawa M, Fmsb: functions for medical statistics book with some demographic data. 2018. R package. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wickham H ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag; 2009. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pham MX, Deng MC, Kfoury AG, Teuteberg JJ, Starling RC, Valantine H. Molecular testing for long-term rejection surveillance in heart transplant recipients: design of the Invasive Monitoring Attenuation Through Gene Expression (IMAGE) trial. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26(8):808–814. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2007.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamath M, Shekhtman G, Grogan T, et al. Variability in donor-derived cell-free DNA scores to predict mortality in heart transplant recipients – a proof-of-concept study. Front Immunol. 2022;13. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.825108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teuteberg J, Kobashigawa J, Shah P, et al. Donor-derived cell-free DNA predicts de novo DSA after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021;40(4, Supplement):S30. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2021.01.1810 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Chambers DC, et al. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty-fifth Adult Heart Transplantation Report-2018; Focus Theme: multiorgan Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018;37(10):1155–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2018.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crespo-Leiro MG, Zuckermann A, Bara C, et al. Concordance among pathologists in the second Cardiac Allograft Rejection Gene Expression Observational Study (CARGO II). Transplantation.2012;94(11):1172–1177. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31826e19e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amadio JM, Rodenas-Alesina E, Superina S, et al. Sparing the prod: providing an alternative to endomyocardial biopsies with noninvasive surveillance after heart transplantation during COVID-19. CJC Open. 2022;4(5):479–487. doi: 10.1016/j.cjco.2022.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kewcharoen J, Kim J, Cummings MB, et al. Initiation of noninvasive surveillance for allograft rejection in heart transplant patients >1year after transplant. Clin Transplant. 2022;36(3):e14548. doi: 10.1111/ctr.14548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oellerich M, Shipkova M, Asendorf T, et al. Absolute quantification of donor-derived cell-free DNA as a marker of rejection and graft injury in kidney transplantation: results from a prospective observational study. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(11):3087–3099. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng MC, Eisen HJ, Mehra MR, et al. Noninvasive discrimination of rejection in cardiac allograft recipients using gene expression profiling. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(1):150–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01175.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trivedi JR, Pahwa SV, Whitehouse KR, Ceremuga BM, Slaughter MS. Racial disparities in cardiac transplantation: chronological perspective and outcomes. PLoS One. 2022;17(1):e0262945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Mendeley Data at https://doi.org/10.17632/cpyj7v99rj.2.