Abstract

Numerous strategies are employed by cancer cells to control gene expression and facilitate tumorigenesis. In the study of epitranscriptomics, a diverse set of modifications to RNA represent a new player of gene regulation in disease and in development. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most common modification on mammalian messenger RNA and tends to be aberrantly placed in cancer. Recognized by a series of reader proteins that dictate the fate of the RNA, m6A-modified RNA could promote tumorigenesis by driving pro-tumor gene expression signatures and altering the immunologic response to tumors. Preclinical evidence suggests m6A writer, reader, and eraser proteins are attractive therapeutic targets. First-in-human studies are currently testing small molecule inhibition against the METTL3/METTL14 methyltransferase complex. Additional modifications to RNA are adopted by cancers to drive tumor development and are under investigation.

Keywords: Epitranscriptomics, RNA modifications, Cancer, METTL3, N6-methyladenosine

RNA modifications regulate gene expression

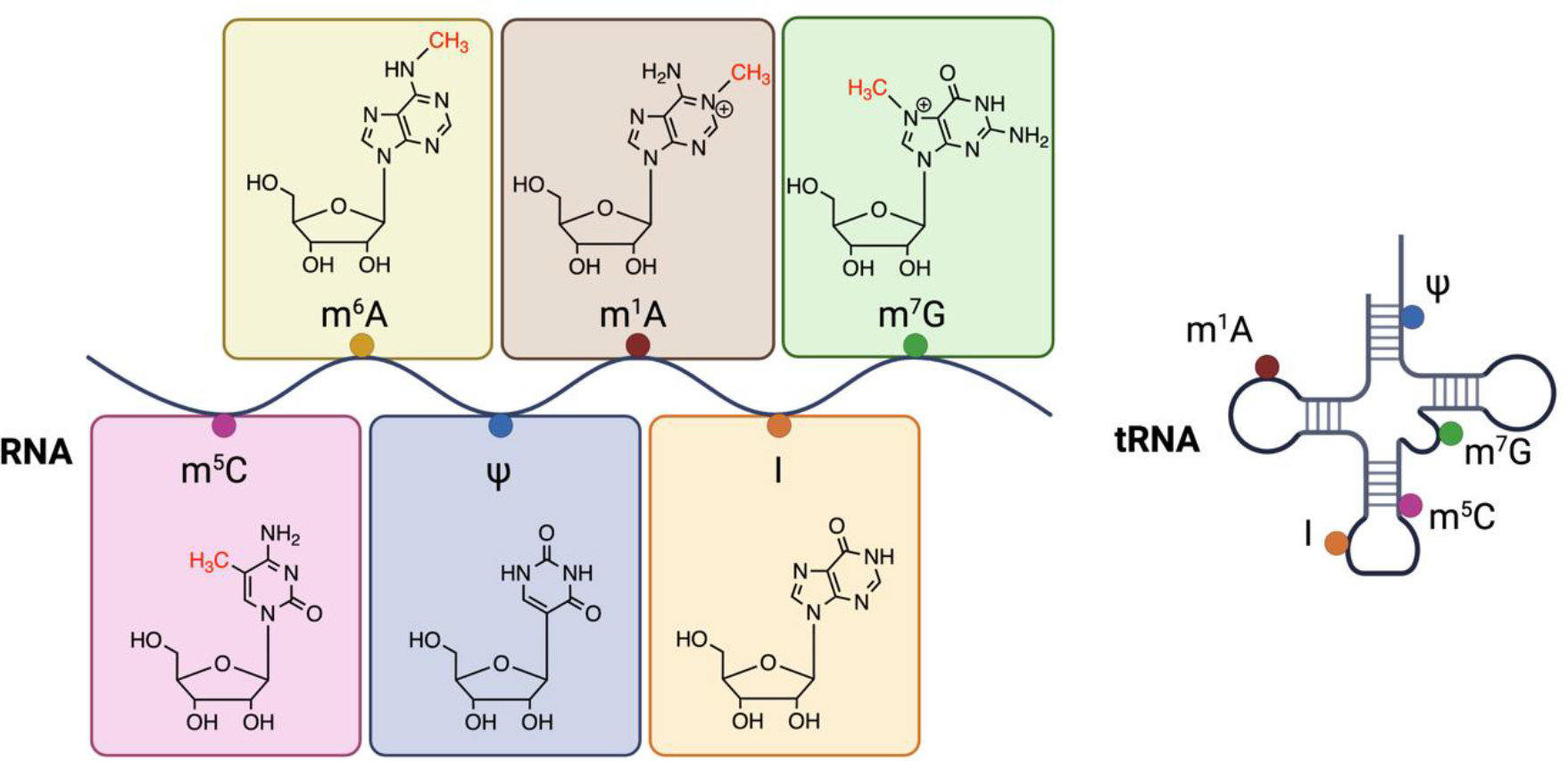

Gene expression relies on dynamic amplification and suppression of genetic signals into functional biomolecular units of RNA and protein, a process that is tightly regulated in time and space [1]. The word epitranscriptomics refers to a group of post-synthesis modifications to canonical A, C, G, and U bases on RNA [2–4]. Both coding and noncoding RNA can undergo more than 150 distinct alterations, which have an impact on a wide range of biological processes (Figure 1) [2]. tRNA and rRNA contain the highest number of modifications, additions that modulate structure and function of these RNAs and eventually alter translation of mRNA into protein. Modifications are placed by several writers, or enzymes that catalyze the deposition of RNA modifications.

Figure 1. RNA modifications are distributed across mRNA, noncoding RNA, rRNA, and tRNA.

m6A is the most abundant modification on mRNA. Marks can be distributed across the transcript body and at locations important for RNA processing, such as at splice sites and the 5’ cap of mRNA. tRNA contain a highly diverse set of modifications, few select examples shown in this figure. These modifications can alter the protein coding ability of transcripts. Created with BioRender.com.

The most common internal modification to mammalian mRNA is N6-methyladenosine, often studied in human disease due to the ability of m6A to affect the fate of protein-coding mRNA [5]. m6A is placed by a methyltransferase complex composed primarily of methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) and methyltransferase-like 14 (METTL14) [6–9]. m6A is detected by an expanding list of reader proteins that recognize marked RNA and enable a diverse set of cellular functions that mediate tumorigenesis [2, 10]. The discovery of eraser proteins fat mass and obesity associated protein (FTO) and alkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5) demonstrated the reversible nature of m6A [11, 12]. Pseudouridine is an abundant modification found on most types of RNA, including eukaryotic mRNA [13–17]. Commonly referred to as the “fifth nucleotide”, pseudouridine is the isomerization product of uridine [18, 19]. N1-methyladenosine (m1A) has been primarily characterized as a component of tRNA, deposited by the tRNA methyltransferase (TRM) family of proteins [20]. 7-methylguanosine (m7G) is found on multiple types of RNAs. Base editing of RNA is marked by adenosine residues switching to inosine, carried out by adenosine deaminase acting on double-stranded RNA (ADAR) family of proteins [21, 22].

Many cancers utilize RNA modifications as a mechanism to enhance or repress expression of genes in favor of an oncogenic state [20]. Efforts to characterize the function of RNA modifications have been aided by sequencing innovations that have hastened insight into their function in development and in disease [23, 24]. Targeting RNA modifications is a budding strategy to target various cancers, and determination of effective settings in which to modulate their function is underway, along with efforts to develop specific and effective compounds that target the enzymes that deposit such modifications.

As the role for epitranscriptomics in cancer has been unveiled, an outstanding question in the field is addressing the ability to therapeutically target the proteins that install these marks. Essentiality and tissue specificity of such broadly functioning proteins are concerns, though many groups have compared modification levels and methyltransferase levels in cancerous tissue to matched normal control tissue with notable differences. Genetic knockdown and knockout experiments are helpful in the study of methyltransferase proteins but can hinder the identification of catalytic effects due to the simultaneous obstruction of catalytic independent roles in cells. Despite these challenges, small molecules have been synthesized and have exhibited promising effects in early studies, with first-in-human studies currently ongoing. In this review, we look to critically evaluate the targeting potential of catalytic activity of proteins that deposit RNA modifications.

The role of METTL3 and METTL14

The METTL3/METTL14 complex as writers of m6A

Co-transcriptional placement of m6A on mRNA is guided by a methyltransferase complex composed of METTL3, METTL14, and Wilms-tumor associated protein (WTAP) together with accessory proteins [2, 6, 8]. m6A is found at a consensus DRACH sequence motif, where D = A, G, or U; R = A or G; and H = A, C, or U. Exon architecture guides the selection of transcripts for m6A installation, with areas encompassing exon-junction complexes (EJC) insulated from m6A placement [25–27]. m6A is recognized by nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA-binding reader proteins that dictate the fate of marked RNA and is removed by eraser proteins FTO and ALKBH5 [2, 11, 12].

From early studies, it was apparent that m6A influences ubiquitous aspects of tumorigenesis, such as cell proliferation, differentiation from a stem-like state, and invasion [2, 20]. m6A is placed co-transcriptionally and serves as a central mediator to gene expression, and a bridge to translation. To note, the activity of METTL3 can be disease-specific, as there are differences in cellular response to depletion of METTL3; in some instances, METTL3 promotes tumorigenesis, while few others use METTL3-mediated m6A deposition to drive tumor suppression [28, 29]. Mutations of methyltransferase components can also occur, such as a hotspot mutation of METTL14 that appears to promote progression of endometrial cancer [30]. These contradictions together with findings of concomitant catalytic dependent and catalytic independent functions of METTL3 have increased the complexity of characterizing the translational impact for inhibitors against the methyltransferase complex.

Many initial studies in cancer revealed that METTL3 functions in hematologic malignancies [20, 31]. Depletion of METTL3 generated a prominent influence on differentiation of leukemic cells and reduced cell proliferation, an effect that was only rescued with wild-type METTL3, suggesting the necessity for intact catalytic function [32]. In recent years, the phenotypic effect of METTL3 has extended to solid tumors [33–39]. Akin to the influence of METTL3 on prevention of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) cell differentiation, METTL3 also maintains a glioma stem-like state in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) [40]. Moreover, METTL3 depletion in GBM cells sensitized cells to gamma irradiation and reduced the cellular ability to undergo DNA repair [40]. In a pediatric-derived osteosarcoma cell line, lack of METTL3 sensitized tumors to DNA damage-inducing agent cisplatin, in addition to irradiation therapy [41].

The METTL3 protein can also be modified to alter its activity. METTL3 can be phosphorylated by DNA repair protein ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) at position S43, thus integrating into DNA damage response and repair [41]. Phosphorylated METTL3 localized to foci of DNA double strand breaks, placing m6A onto DNA damage-associated RNAs for protection from degradation, eventually forming DNA:RNA hybrid structures that recruit repair machinery. Interestingly, METTL3 catalytic and phosphorylation sites were both needed to observe this phenotypic effect [41]. METTL3 was also found to have two sites on its zinc finger domain that are susceptible to lactylation, endowing an immunosuppressive effect by promoting an environment with immune escape-promoting tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells (TIMs) [42].

The overlap of METTL3 and METTL14 depletion on cancer cell phenotype is intriguing, especially given the thought that METTL3 plays the predominant catalytic role, while METTL14 is thought to play a rather supportive role. In a recent study assessing the role of m6A in the response to checkpoint blockade, both METTL3 and METTL14 were found to influence response to anti-PD-1 [43]. m6A appears to influence immunoregulation by both cell intrinsic and extrinsic immune responses. While in some cancers immune checkpoint inhibition using anti-PD-1 has been fruitful, in others response has been limited [44]. METTL3 and METTL14 perturbation can enhance the response to anti-PD1 treatment in certain types of colorectal cancer and in melanoma, with m6A bound by YTH domain-containing family 2 (YTHDF2) [43], and in breast cancer recognized by IGF2BP3 [45]. Experiments assessing host-derived immune response show that depletion of METTL3 can contribute to an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by redirecting macrophage response, leading to a pro-tumorigenic effect [46]. Others have shown that loss of m6A after METTL3 depletion diminished immunologic response to tumors, promoting tumor growth [47]. It is clear that both m6A writer- and reader-mediated manipulation impact the immunologic response to tumors. The therapeutic effect of using either in anti-cancer therapy may be context specific, as targets of METTL3 show different response in different cell lines. Alternative isoforms of METTL3 have been identified after knockout in cell line experiments, an effect that if present in vivo could account for variation in effects depending on the system used [48].

METTL3 and METTL14 function are tightly intertwined with transcription. In mouse embryonic stem (mES) cells, knockout of METTL3 led to globally increased chromatin accessibility and increased nascent transcript synthesis [49]. Through interaction of nuclear exosome targeting (NEXT) complex components with nuclear m6A reader protein YTHDC1, m6A-marked chromatin-associated retrotransposon RNA was targeted for degradation at baseline that ultimately affected development. In absence of METTL3, m6A was depleted and resulted in increased differentiation capacity of mES cells [49].

Methyltransferase complex components can also directly interact with DNA and histone proteins. Noting an inverse relationship between repressive DNA mark 5-methylcytosine (5-MC) and m6A levels, METTL3-mediated m6A methylated RNA was found to be an important factor in tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 1 (TET1) binding to target chromatin, demonstrating crosstalk between RNA modifications and DNA modifications [50]. The close relationship is further demonstrated by H3K36me3, which recruits METTL14 to induce deposition of m6A at specific loci during transcription [51]. m6A RNA-binding reader proteins can also directly influence chromatin dynamics. In roles that may have implications on mammalian development, the nuclear m6A reader protein YTHDC1 mediated mES cell state by affecting chromatin through mediation of retrotransposons or retroviral elements [52, 53]. Acting, again, in coordination with histone modifications, YTHDC1 recruited histone demethylase KDM3B to remove H3K9me2 from histone proteins [54]. In other contexts, YTHDC1 together with hnRNP protected newly transcribed RNA from termination using the integrator complex [55].

METTL16 deposits m6A on a subset of mRNA. In a CRISPR-Cas9 screen, METTL16 was essential for survival of many cancers [56]. Similar to METTL3, METTL16 also functions in the cytoplasm to enhance translation initiation by recognizing m6A-marked mRNA of a larger proportion of nearly 4,000 mRNAs, implying cooperative functions of methyltransferase members in enhancing expression of transcripts [56].

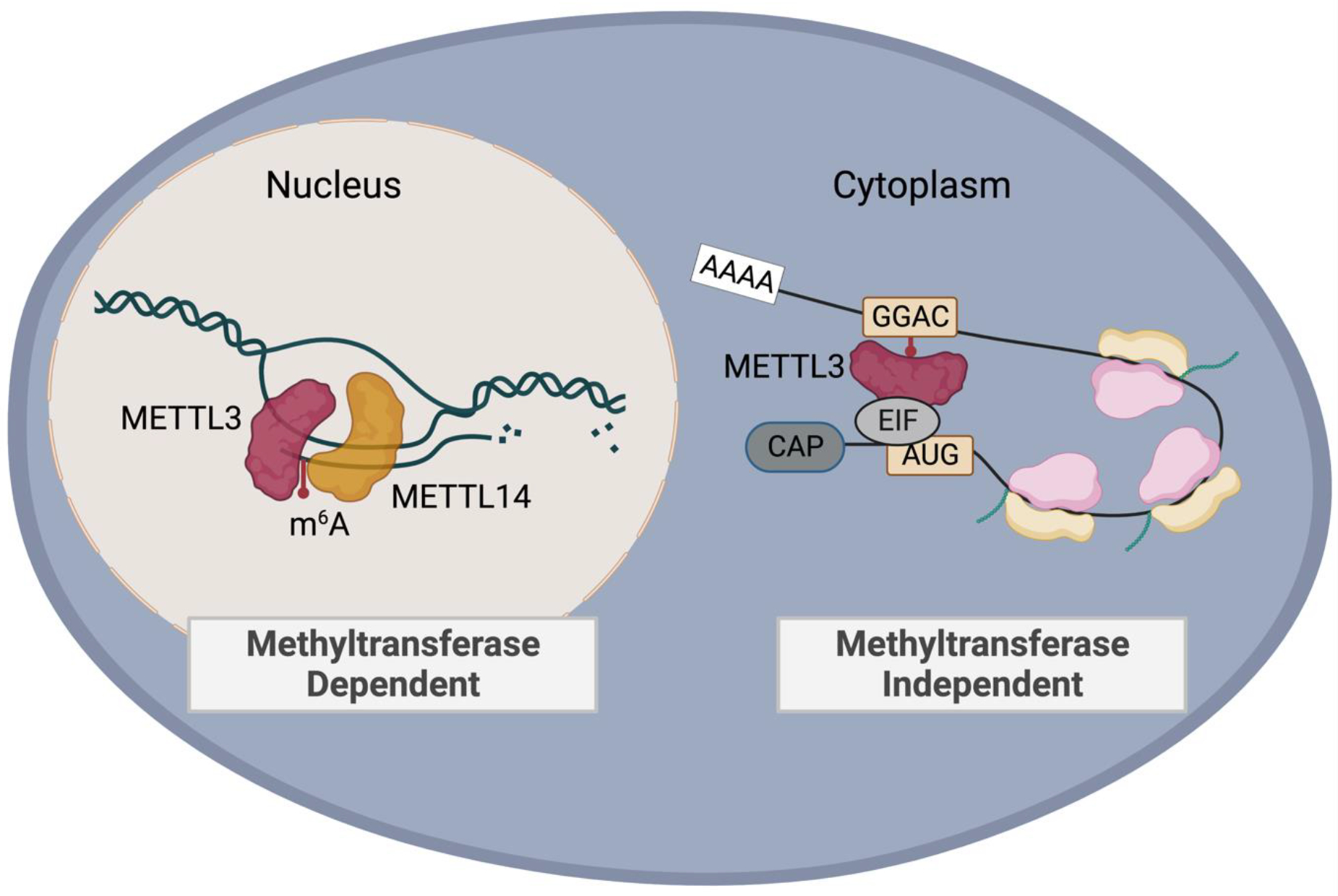

Catalytic-independent roles for METTL3/METTL14

An intriguing observation that METTL3 functioned in an oncogenic role, but that the effect was not dependent on m6A was identified by Lin et. al in 2016 [57]. In lung cancer, a reporter assay showed that METTL3 directly promoted translation of mRNA into protein by recruiting the translation initiation machinery. Expression of catalytic inactive METTL3 rescued protein translation deficiencies, suggesting that cytoplasmic METTL3 can function independent of m6A deposition. The mechanism was further characterized to show that METTL3 enhanced protein translation by promoting an mRNA looping-based structure with translation machinery [58]. Since then, this theme has been recapitulated in various settings and has shown that the ability of METTL3/METTL14 to induce oncogenicity can be both dependent on the ability of the methyltransferase complex to catalyze the deposition of m6A, and a function separate from catalytic deposition [59].

Using a system to induce cellular senescence, METTL3 and METTL14 were both able to drive a phenotype called senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) [60]. SASP is characterized by various cytokines and chemokines that endow cells with enhanced ability to mediate both recognition and evasion of detection by the host immune response. METTL3 scattered to transcription start sites and METTL14 to gene enhancers, ultimately mediating an immunoregulatory state. Interestingly, gene expression changes from METTL14 and METTL3 knockdown cells could be rescued with both WT and catalytic mutant forms of each protein, suggesting that SASP was not dependent on catalytic m6A deposition [60].

METTL14 can function independently of the catalytic complex responsible for m6a deposition by mediating transcription [61]. In mES cells, where METTL3 depletion led to a global increase in transcription, METTL14 depletion resulted in a global decreased production of nascent RNA. Mechanistically, the histone mark H3K27me3 is recognized by METTL14 and ultimately recruits demethylase KDM6B to globally repress transcription [61]. Insights gained from studying differentiation capacity in mES cells in response to the m6A methyltransferase complex represents a mechanism that may be replicated in other disease processes such as cancer [62].

m6A reader proteins

Translating the message of m6A-marked RNA is undertaken by a set of reader proteins that serve to recognize and recruit processing factors that dictate the fate of modified RNA. The primary family members that have been characterized include the YTH domain-containing family (YTHDF1-3, YTHDC1-2), insulin-like growth factor 1 mRNA-binding protein (IGFBP2) family, proline-rich coiled-coil containing protein 2A (PRRC2A), and heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoproteins A2/B1 (HNRNPA2B1) [20]. YTHDF1 and YTHDF2 bind m6A to modulate RNA translation and RNA degradation, respectively, while YTHDF3 can enhance the function of both YTHDF1 and YTHDF3 [2, 63]. In an animal model of melanoma and colon cancer, YTHDF1 depletion enhanced recruitment of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells into the tumor [64]. Loss of YTHDF1 decreased the translation of cathepsins, which allowed for decreased lysosomal-mediated degradation of tumor specific antigens. The effect of this was increased capacity for dendritic cells to promote cross-presentation to CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. In response, tumor growth was slowed, and response to checkpoint blockade therapy was markedly increased [64].

The host immune response to tumors is also mediated by reader protein YTHDF2. In a mouse model of melanoma and colorectal cancer, the antitumor CD8+ cytotoxic T cell response was blunted in presence of YTHDF2 [65]. By decreasing the stability of STAT1 mRNA in macrophages, YTHDF2 dampened cross presentation of tumor antigens to T cells, and subsequent downregulation of YTHDF2 led to reduced tumor growth and metastasis [65]. Enhanced response to checkpoint blockade in colorectal cancer (CRC) in the setting of METTL3 or METTL14 depletion was also dependent on YTHDF2 [43]. YTHDF2 is highly expressed in many different cancers, and tumors such as AML and glioblastoma exhibit a selective dependency on the protein [65–67]. In glioblastoma, YTHDF2 mediated the stability of LXRα and HIVEP2 mRNA, and depletion of YTHDF2 led to LXRα-mediated tumor growth inhibition by reducing intracellular cholesterol [68]. In AML, loss of YTHDF2 led to decreased proliferation in leukemic cells and sensitized them to tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-induced apoptosis [66]. Interestingly, sensitivity to YTHDF2 perturbation is dependent on the differentiation state of the cell. While YTHDF2 loss affected leukemic cells and led to expansion of HSCs, there was no impact on normal hematopoiesis [66].

The impact on HSC expansion has vast clinical applicability. In patients who undergo hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), the source for HSCs that produce the most optimal clinical outcome is often from cord blood donors. However, use of cord blood is limited by the low cell numbers derived that are needed for successful transplant. In mouse HSCs, YTHDF2 knockout led to expansion of phenotypical HSCs [69]. Knockdown of YTHDF2 in human cord blood samples led to increased expression of m6A-marked self-renewal-related transcription factors, supporting a role for YTHDF2-mediated mRNA degradation to maintain cord blood HSC self-renewal [69]. 10 weeks post-transplant, mice that were transplanted with YTHDF2 knockdown HSCs had a nine-fold increase in hematopoietic cell engraftment in the bone marrow, without any changes to the proportion of other cell lineages [69].

m6A reader proteins influence a variety of cellular processes linked to oncogenesis. m6A is detected in many DNA:RNA hybrid structures, otherwise known as R loops, which contribute to genomic instability [70]. YTHDF2 degrades m6A-marked RNA comprising R loop structures, which could have meaningful implications in cancer biology [70]. YTHDF1, YTHDF2, and YTHDF3 undergo liquid-liquid phase separation, capturing m6A-methylated RNA into organized structures such as P-bodies and stress granules for processing [71, 72]. As a binding partner of YTHDF1, fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) phosphorylation stimulated translational activity of YTHDF1, an effect that is recapitulated in fragile X syndrome [73].

m6A eraser proteins

The reversible nature of m6A is demonstrated by demethylases FTO and ALKBH5, which function to remove m6A from RNA in an iron(II)- and α-ketoglutarate-dependent manner [11, 74]. FTO can also remove methylation from N6,2’-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am) and m1A in tRNA, with the prominent number of sites comprising m6A. Consistent with the paradoxical effect of the METTL3/METTL14 complex as both tumor suppressive and oncogenic, FTO and ALKBH5 play diverse roles in driving cancer depending on the tumor and context in which they are studied. ALKBH5 and FTO both target a subset of genes in AML to influence cell growth and differentiation [75, 76]. In mES cells, FTO mediated the demethylation of m6A-containing long-interspersed element-1 (LINE1) RNA, which affected chromatin state and regulated gene expression during development [77]. These studies support the notion of RNA modifications as a fundamental component of human development and disease, and small molecules have been synthesized to target them (Table 1).

Table 1.

Small molecule inhibitors that target RNA modifications

| Inhibitor Name | Cancer | Anticancer Potency | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| METTL3/METTL14 | |||

| STM2457 | AML | 0.6 μM −10.3 μMa | [104] |

| STC-15 | advanced tumors | NCT05584111 | |

| Multiple small molecules | AML, ovarian adenocarcinoma | 80 nM–1.39 μM | [105–108, 132] |

| Multiple small molecules | AML | <1 μM, <10 μM | [109–111, 132] |

| UZH2 | AML, prostate cancer | 12 μM, 70 μM | [112] |

| UZH1a | AML, osteosarcoma | Not tested | [133] |

| CDIBA | AML | GI50 13–22 μM | [115] |

| Eltrombopag | AML | GI50 = 8.28 μM | [116] |

| Elvitegravir | esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | reduced metastasis | [134] |

| YTHDF | |||

| Ebselon | prostate cancer | 26.83 μM | [119] |

| YTHDF1 | |||

| Salvianolic Acid (SAC) | neuronal tissue | N/A | [73] |

| YTHDF2 | |||

| CpG-siRNAYTHDF2 | mouse melanoma, murine colon adenocarcinoma | reduced tumor growth and metastasis | [65] |

| FTO | |||

| CS1, CS2 | AML | CS1:22 nM–753 nM CS2: 55.9 nM–1.127 μM |

[122] |

| FB23–2 | AML | 1.9 μM −5.2 μM | [135] |

| MO-I-500 | triple-negative inflammatory breast cancer | Inhibited survival and colony formation | [136, 137] |

| MA | HeLa | N/A | [138] |

| MA2 | GSCs | Inhibited growth and self-renewal of GSCs, suppressed tumor progression and prolonged lifespan of GSC-grafted mice | [29] |

| FTO-04 | GSCs, glioblastoma |

Impaired self-renewal properties | [139] |

| Dac51 | Melanoma | Inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival of melanoma mouse models in combination with immunotherapy | [140] |

| R-2HG | Non-IDH mutant | decreased cell | [141] |

| AML, Glioma | proliferation | ||

| ALKBH5 | |||

| 2-[(1-hydroxy-2-oxo-2-phenylethyl)sulfanyl]acetic acid, 4-{[(furan-2-yl)methyl]amino}-1,2-diazinane-3,6-dione | AML | 1.38 μM −47.8 μM | [142] |

| PUS7 | |||

| C17 | Glioblastoma, GSCs |

56.77 nM–177.4 nM | [94] |

denotes IC50, unless otherwise specified

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; GSCs, glioma stem-like cells; METTL3, methyltransferase-like 3; METTL14, methyltransferase-like 14; YTHDF, YTH domain-containing family protein; FTO, fat mass and obesity-associated protein; ALKBH5, alkB homologue 5; PUS, pseudouridine synthase; MA, meclofenamic acid; N/A, not available; IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenases

Additional writers of RNA modifications

METTL1/WDR4 complex

METTL1, together with WD repeat domain 4 (WDR4), catalyze the synthesis of N7-methylguanosine (m7G), which is the addition of a methyl group to ribo-guanosine at the N7 position [78]. m7G is found on tRNA, mRNA, miRNA, and rRNA, representing the most common modification to the cap of mRNA, and found internally in the additional types of RNA [79, 80]. m7G functions to influence gene expression through its role in RNA processing, metabolism, and function. METTL1 is found at higher levels in cancerous tissue compared to non-cancerous tissue [81]. The METTL1/WDR4 complex has potential opposing mechanisms on tumorigenicity depending on the RNA modified; when found on tRNA m7G is tumor promoting, while on miRNA is tumor suppressing in cases known to date [80].

Knockdown of METTL1 or WDR4 has led to decreased m7G modifications on tRNA in nasopharyngeal carcinoma, neuroblastoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, bladder cancer, and AML, among others [81–85]. METTL1 knockdown in these instances impaired aspects of codon recognition and tRNA functionality that ultimately impaired protein translation. Collectively, this perturbation has led to features of decreased tumorigenicity such as increased apoptosis and decreased cell cycle progression, chemoresistance, and tumor growth in mice. Using a sensitive strategy to map m7G on miRNA, heightened let-7 miRNA processing was shown to inhibit cell migration and decrease tumorigenicity [86].

NOL1/NOP2/SUN domain family of proteins

Methylation of cytosine is common to multiple types of RNAs, such as rRNA, tRNA, mRNA, and non-coding RNA [87]. m5C is catalyzed by a family of proteins of the NOL1/NOP2/SUN domain family of SAM-dependent methyltransferases NSUN1 to NSUN7, and DNA methyltransferase homolog DNMT2 [88]. NOP2/NSUN1, previously known as p120, has classically been found upregulated in proliferating cancer cells [89, 90]. Their role in regulating gene expression stems from the ability to influence ribosomal RNA processing, which in turn has widespread effects on gene expression into proteins. m5C has also been implicated in leukemia and in glioma [91, 92]. Similar to the diverse effects of the m6A methyltransferase complex, NOP2/NSUN1 were shown to have both catalytic and non-catalytic functions. Using cells derived from a patient with colon cancer, NOP2/NSUN1 recruited U3 and U8 snoRNAs to pre-90s ribosomes and influenced the assembly into complete snoRNP complex, an effect that was rescued by both catalytic inactive and wild type NOP2/NSUN1 [89].

Pseudouridine synthases

Often activated by stressors, the isomerization product of uridine, pseudouridine is placed by a family of pseudouridine synthase enzymes PUS1-PUS7, PUS7L, RPUSD1 to RPUSD4, and DKC1 [20]. While in the context of embryonic stem cell development perturbations of epitranscriptomic writers affect broad swaths of gene expression [93], it appears as though this effect can also be used to direct specific cohorts of biological pathways in cancer. In glioblastoma, PUS7 is more highly expressed in cancer tissue compared to control tissue, and its high expression correlates with poor prognosis. Knockout of PUS7, instead of inducing global alterations in protein translation, led to codon-specific translation alterations that were vital in regulating glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs) [94]. Interestingly, a catalytic-independent role for PUS7 has also been discovered in CRC [95]. In probing for enhanced mechanistic understanding of the function of pseudouridine, sequencing of the marks revealed enrichment at RNA regulatory regions of nascent pre-mRNA. Pseudouridine was found at sites of alternative splicing and RNA binding sites, further supporting the role for such modifications in regulating gene expression [13]. A new method using bisulfite-induced deletion sequencing (BID-seq) enabled stoichiometric mapping of pseudouridine on mouse tissue mRNA with low sample input [96]. Using this method, pseudouridine was found to increase stability of mRNA, and writer-specific pseudouridine deposition could be characterized.

RNA editing

The facilitation of RNA base editing from adenosine to inosine is carried out by the ADAR family of proteins ADAR1, ADAR2, and ADAR3, with ADAR1 being the most actively studied [97] and ADAR2 that may be tumor-inhibitory [98]. The ADAR family of proteins alter gene expression by modulating sequence and structure of both RNA and protein [21, 22]. When found within the coding sequence, inosine is interpreted as guanosine, leading to codon changes that subsequently alter the amino acid sequence and affect protein production. During RNA processing, RNA editing leads to alternatively spliced RNA [21]. Structurally, inosine preferentially pairs with cytidine instead of adenosine to uridine [21]. Like other RNA modification writers, ADAR1 and ADAR2 have both tumor suppressive and tumor promoting functions, shown by knockdown studies [20]. A large portion of RNA editing occurs in the non-coding portions of RNA. A mechanism prominent in human disease, ADAR1 is used to edit endogenous double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) to avoid activation of the innate immune system that would typically recognize dsRNA as non-self and mark for destruction [97, 99]. Cancer cells adopt this process to avoid perception as non-self.

A genome-wide screen of dependencies in multiple lung cancer cells placed ADAR1 as a common node of susceptibility in cells with high expression of interferon response genes [100]. In cancer, depletion of ADAR1 has shown varying effects on tumor growth. In a solid tumor model, where ADAR1 depletion has led to negligible effects on tumor volume, tumors demonstrated a markedly enhanced response to PD-1 antibody treatment [101]. Loss of ADAR1 also was able to mitigate common methods of resistance to immune checkpoint blockade using PD-1 antibody treatment [101]. In a model of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), loss of ADAR1 led to decreased cell proliferation, however this was not completely dependent on the RNA editing effects of ADAR1 or on the interferon response [102]. Instead, a concomitant effect on interferon response and on protein translation was seen. Similarly, in lung cancer, catalytic mutant ADAR1 partially rescued the effect of ADAR1 depletion, suggesting both catalytic and noncatalytic functions of ADAR1 [100]. A relationship between m6A and ADAR1 is present, whereby deaminase independent ADAR1 is a target of METTL3 in glioblastoma, and perturbation impairs glioblastoma growth [103].

Optimizing anticancer therapy by targeting RNA modifications

Pharmacologic approaches to targeting m6A

Small molecules that exhibit specificity against RNA modification machinery are key tool compounds to dissect roles of these modifications in different cancer types. A prominent development in the targeting of RNA modifications was the development of a catalytic inhibitor against METTL3 [104] (Table 1). Catalytic inhibitors function to interfere with the methyltransferase dependent function of the METTL3/METTL14 complex (Figure 2). The first bioavailable synthesized small molecule STM2457 was tested in vitro against a panel of structurally similar methyltransferases and exhibited specificity primarily to the METTL3/METTL14 complex. What was distinctly promising about this small molecule was the ability to target bulk AML as well as leukemia stem cells in vitro and in vivo without notable differences in animal weight, impact on bone marrow-derived hematopoietic stem cells, or early progenitor cells. Mice treated with the small molecule at a dose of 50mg/kg showed decreased disease burden while leaving hematopoietic stem cell precursors (HSCPs) untouched and with no appreciable toxicity to animals [104]. Since then, an orally bioavailable small molecule, STC-15, was synthesized in the United Kingdom that is now in active multi-center phase I clinical trials to assess for safety in advanced tumors (NCT05584111). Other patents filed by companies Accent Therapeutics and Storm Therapeutics suggest an influx of newly synthesized small molecules with potential for enhanced specificity [105–111]. Structure-based screening also identified small molecule UZH2, which was tested in a leukemia and prostate cancer cell line and decreased m6A levels on mRNA without affecting other related modifications [112]. Virtual screening has detected small molecules amentoflavone and methyl heperidin that could be considered as tool compounds, though these molecules have not been validated [113]. Adenosine analogues have been described, albeit with lower sensitivity, as well as allosteric inhibitor 43n, which showed an antiproliferative effect in AML cell lines [114, 115]. Eltrombopag, a medication typically used to treat cytopenia, demonstrated properties of noncompetitive inhibition of METTL3 [116]. Additional proposed METTL3 inhibitors were less specific, such as the general nucleoside analogue sinefungin and s-adenosylhomocysteine, with additional molecules reviewed by Fiorentino et al. [117, 118].

Figure 2. Targeting the catalytic activity of the METTL3/METTL14 complex.

Small molecule inhibition of the METTL3/METTL14 m6A methyltransferase complex interferes with co-transcriptional deposition of m6A on target transcripts. Catalytic inhibition does not directly mediate the scaffold effect of METTL3. In the cytoplasm, a catalytic-independent function of METTL3 is to recruit proteins such as translation initiation factors to enhance translation of target transcripts. Created with BioRender.com.

Many m6A-mediated tumorigenic effects are mediated by downstream reader proteins. Identification of additional facets to the m6A-reader axis could help define therapeutic specificity. The fact that m6A-marked RNA can be read by multiple different reader proteins suggests that targeting specific pathways has potential to increase disease selectivity. Early studies shed light onto this possibility. Screening for molecules that fit inside the hydrophobic pocket of the YTH family of proteins identified ebselon, a small molecule that was able to interact with each YTHDF paralog [119]. Identification of the small molecule inhibitor salvianolic acid C (SAC) was able to ablate condensates containing YTHDF1 and inhibit hyperactive YTHDF1 in neurons, demonstrating the potential for small molecule therapy against YTHDF1 [73]. Despite YTHDF1 being structurally similar to YTHDF2, SAC showed multi-fold increase in specificity toward YTHDF1. While small molecules have been identified as a YTHDF2-based therapeutic dependency, therapies that directly and specifically target YTHDF2 have not been identified to date [67, 120]. In an alternative strategy, YTHDF2 siRNA was conjugated to a toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) agonist, that when internalized by antigen presenting cells slowed tumor growth and decreased metastasis [65].

A role for reader protein YTHDC1 has been described in AML, where m6A facilitated YTHDC1-containing condensates, restraining AML cells in an undifferentiated state [121]. These findings, together with those from YTHDF1 suggest disruption of phase separation may be a tenable mechanism to disrupt m6A-mediated oncogenesis. Multiple inhibitors have been identified against FTO and tested in various cancers, most recently CS1 and CS2, where at low nanomolar levels showed specificity against FTO in AML [122].

Targeting additional RNA modification proteins

In an effort to identify compounds with enzymatic activity against PUS7, a virtual screening platform of over 270,000 chemicals was used [94]. Prospective small molecules from the screen were then tested using an in vitro assay to assess target specificity, identifying compound NSC107512, or C17, as a top candidate. Addition of C17 decreased growth of GSC-derived tumors and extended lifespan of mice [94]. Though additional inhibitors of pseudouridine synthase enzymes have been proposed, their intracellular targets are rather widespread [123]. Analogues of adenosine substrates have been proposed as ADAR inhibitors [124]. However, characterization of these small molecules have questioned the specificity of both [125]. Three FDA-approved compounds were also predicted to target the interferon-responsive catalytic structure Zα domain of ADAR1, though untested in a biological system [126].

Implementation of targeted RNA modification therapies into the clinic

The failure of phase I clinical trials in cancer reaches approximately 90 percent [127]. Furthermore, limited scientific reproducibility hinders reliable drug development. It is imperative for those involved in preclinical target identification and drug design to consider the end goal of treatment response throughout initial mechanistic studies. Incorporating appropriate positive and negative controls, performing rescue experiments, and validating on-target effect are critical to improve preclinical studies [128]. In the case of targeting RNA methyltransferase proteins, catalytic inactive mutants have helped to dissect important functions of individual proteins and predict response to catalytic inhibition. Knockout of METTL3 in mES cells is embryonic lethal, consistent with the finding that loss of METTL3 can lead cells to lose self-renewal capabilities [9]. It is possible that the effect is a combination of the catalytic activity of METTL3 and its scaffold effect; catalytic inhibition could enhance specificity so that cancerous tissue is affected, leaving minimal toxicity to non-cancerous tissue. Indeed, a common theme among expression of RNA modification-inducing proteins is that the cancer cell often possesses higher levels of any given RNA modification enzyme compared to non-cancerous tissue. This has been demonstrated in the case of the m6A methyltransferase complex, enzymes that induce pseudouridylation, and RNA editing proteins, enabling a potential therapeutic window. If elimination of the whole protein is desired, protein degradation technology is an alternative approach [129]. This technique has the potential to disrupt both methyltransferase-dependent and methyltransferaseindependent functions of methyltransferase proteins.

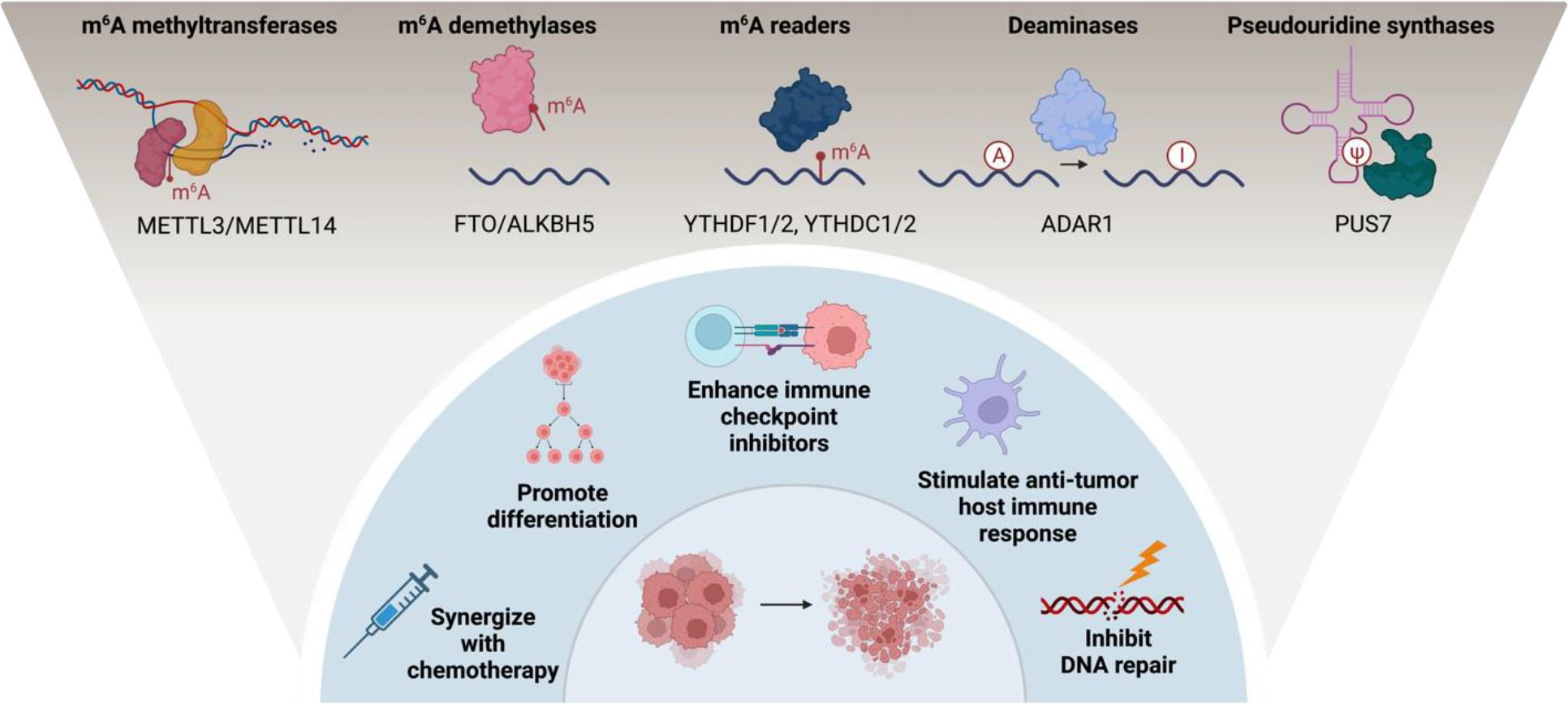

The therapeutic course of a patient’s disease presents multiple opportunities for use of RNA modification mediators to enhance response to therapy (Figure 3). METTL3 inhibition can synergize with common chemotherapy agents, radiation therapy, and in the case of reader proteins aid in the process of hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Leveraging RNA modifications to mitigate common barriers to anti-cancer therapy should be considered in future work. In breast cancer, YTHDF1 promoted resistance to standard chemotherapy agents, yielding an opportunity to deter resistance in the setting of YTHDF1 depletion [130]. RNA sequencing analysis of patients with AML found METTL3 to be a mediator of chemoresistance in patients with relapsed disease, an effect that was dependent on the catalytic activity of METTL3 [131]. Treatment with catalytic METTL3 inhibitor STM2457 reduced proliferation and increased apoptosis of chemoresistant AML cells. The orally available METTL3 inhibitor currently in phase I clinical trials, STC-15, also enhanced response to treatment with BCL2 inhibitor Venetoclax, an agent used in AML therapy protocols (Storm Therapeutics). Opportunities to reduce dosages of standard chemotherapy that carry lifetime toxicities could be opened in presence of strategies that reduce their need.

Figure 3. Using RNA modification enzymes to amplify the anti-tumor response of standard therapies.

Modifications mediated by m6A writers METTL3 and METTL14, pseudouridine synthase PUS7, m6A demethylases FTO and ALKBH5, reader proteins YTHDF1 or YTHDF2, and enzymes responsible for adenosine to inosine (A to I) RNA editing can synergize with existing modalities of treatment. Enhanced anti-tumor activity in the preclinical setting has been observed when combined with strategies such as standard chemotherapy and radiotherapy-induced DNA damage. Additional anti-tumor activity has been observed in combining depletion of select proteins with immune checkpoint inhibitors and by stimulating the host anti-tumor response. RNA modifications can also mediate differentiation of some cancer cells from a stem cell-like state. Created with BioRender.com.

Concluding Remarks

The arc of progression from a gene unit to functioning RNA and protein biomolecules is traditionally characterized as the output of transcription and translation. We discover that this process is more interconnected than a silo-like separation of systems. An extraordinarily functionally diverse collection of RNA alterations serve as a bridge to direct gene expression, which has a significant impact on tumor formation. When considering the efficacy of cancer treatment approaches, the targeting of a single identified driver has frequently failed for a variety of reasons, including the development of resistance and intra- or intertumoral heterogeneity. Hence, it is advantageous to consider nodes that can influence a shared network of targets within a tumor. Such is the possibility of RNA modification targeting. Furthermore, it appears that these methyltransferase-depositing proteins may be more active or expressed at higher levels in cancer cells compared to matched non-cancerous tissue.

Several studies have attributed the anti-tumor activity of methyltransferase depletion to catalytic function, demonstrating that pharmacologic approaches to targeting these proteins is a promising technique. Additional medicinal chemistry and characterization efforts are needed to develop new relevant small molecule inhibitors as well as enhance the efficacy of the existing ones, assess safety profiles, and identify responsive cancers (see Outstanding questions). In the future, it will be essential to consider clinical and genetic biomarkers to identify optimal patient selection and evaluate treatment response. Overall, targeting the catalytic activity of RNA modification proteins is a promising anti-cancer treatment strategy.

Outstanding Questions.

Initial studies used genetic methods of depletion to characterize the role of RNA modifications in cancer. Will the phenotypic findings from these studies be recapitulated with pharmacologic based activity inhibition?

Writers, readers, and erasers of RNA modifications are often more highly expressed in cancers compared to matched tissue controls. However, expression is not always limited to cancer tissue. Is there an appropriate therapeutic window to target these RNA modification proteins without inducing toxicity to patients?

The METTL3/METTL14 complex has shown both pro- and anti-tumorigenic functions in some cancers, such as glioblastoma. What accounts for this discrepancy?

Though most m6A deposition is catalyzed by the methyltransferase complex composed of METTL3 and METTL14, other proteins such as METTL16 have been shown to install m6A in cancers. Is there a redundant role for methyltransferase proteins that cancer cells could exploit to induce resistance to pharmacologic inhibition?

Highlights.

Epitranscriptomics is the study of a diverse set of chemical modifications to RNA that are installed, detected, and removed by a series of proteins.

RNA modifications mediate the expression of genes by affecting a diverse set of cellular processes.

Cancer cells commonly express high levels of certain writers, readers, and erasers of RNA modifications compared to matched non-cancerous tissue, and high expression is often associated with poor prognosis.

Preclinical evidence provides proof-of-concept that therapeutic targeting of RNA modifications is a promising anti-cancer strategy and has potential to synergize with existing treatment modalities.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank all authors who contributed to the work summarized in this review. We would also like to thank the authors who completed studies not included in this review whose work greatly contributes to our understanding of the evolving field of epitranscriptomics.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Statement: C.H. is a scientific founder; a member of the scientific advisory board and equity holder of Aferna Green, Inc. and AccuaDX Inc.; and a scientific co-founder and equity holder of Accent Therapeutics, Inc. M.P. has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Citations

- 1.Buccitelli C and Selbach M, mRNAs, proteins and the emerging principles of gene expression control. Nat Rev Genet, 2020. 21(10): p. 630–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roundtree IA, et al. , Dynamic RNA Modifications in Gene Expression Regulation. Cell, 2017. 169(7): p. 1187–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fu Y, et al. , Gene expression regulation mediated through reversible m⁶A RNA methylation. Nat Rev Genet, 2014. 15(5): p. 293–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li S and Mason CE, The pivotal regulatory landscape of RNA modifications. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet, 2014. 15: p. 127–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei CM, Gershowitz A, and Moss B, Methylated nucleotides block 5’ terminus of HeLa cell messenger RNA. Cell, 1975. 4(4): p. 379–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu J, et al. , A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol, 2014. 10(2): p. 93–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bokar JA, et al. , Purification and cDNA cloning of the AdoMet-binding subunit of the human mRNA (N6-adenosine)-methyltransferase. RNA, 1997. 3(11): p. 1233–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X, et al. , Structural basis of N(6)-adenosine methylation by the METTL3-METTL14 complex. Nature, 2016. 534(7608): p. 575–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, et al. , N6-methyladenosine modification destabilizes developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol, 2014. 16(2): p. 191–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X, et al. , N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature, 2014. 505(7481): p. 117–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jia G, et al. , N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol, 2011. 7(12): p. 885–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng G, et al. , ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell, 2013. 49(1): p. 18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez NM, et al. , Pseudouridine synthases modify human pre-mRNA co-transcriptionally and affect pre-mRNA processing. Mol Cell, 2022. 82(3): p. 645–659 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karijolich J, Yi C, and Yu YT, Transcriptome-wide dynamics of RNA pseudouridylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2015. 16(10): p. 581–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlile TM, et al. , Pseudouridine profiling reveals regulated mRNA pseudouridylation in yeast and human cells. Nature, 2014. 515(7525): p. 143–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz S, et al. , Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals widespread dynamic-regulated pseudouridylation of ncRNA and mRNA. Cell, 2014. 159(1): p. 148–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li X, et al. , Chemical pulldown reveals dynamic pseudouridylation of the mammalian transcriptome. Nat Chem Biol, 2015. 11(8): p. 592–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis FF and Allen FW, Ribonucleic acids from yeast which contain a fifth nucleotide. J Biol Chem, 1957. 227(2): p. 907–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoang C and Ferre-D’Amare AR, Cocrystal structure of a tRNA Psi55 pseudouridine synthase: nucleotide flipping by an RNA-modifying enzyme. Cell, 2001. 107(7): p. 929–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbieri I and Kouzarides T, Role of RNA modifications in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer, 2020. 20(6): p. 303–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishikura K, A-to-I editing of coding and non-coding RNAs by ADARs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2016. 17(2): p. 83–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bass BL and Weintraub H, An unwinding activity that covalently modifies its double-stranded RNA substrate. Cell, 1988. 55(6): p. 1089–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dominissini D, et al. , Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature, 2012. 485(7397): p. 201–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer KD, et al. , Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3’ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell, 2012. 149(7): p. 1635–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He PC, et al. , Exon architecture controls mRNA m(6)A suppression and gene expression. Science, 2023. 379(6633): p. 677–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang X, et al. , Exon junction complex shapes the m(6)A epitranscriptome. Nat Commun, 2022. 13(1): p. 7904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uzonyi A, et al. , Exclusion of m6A from splice-site proximal regions by the exon junction complex dictates m6A topologies and mRNA stability. Mol Cell, 2023. 83(2): p. 237–251 e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang J, et al. , The role of RNA N (6)-methyladenosine methyltransferase in cancers. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids, 2021. 23: p. 887–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cui Q, et al. , m(6)A RNA Methylation Regulates the Self-Renewal and Tumorigenesis of Glioblastoma Stem Cells . Cell Rep, 2017. 18(11): p. 2622–2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu J, et al. , m(6)A mRNA methylation regulates AKT activity to promote the proliferation and tumorigenicity of endometrial cancer. Nat Cell Biol, 2018. 20(9): p. 1074–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barbieri I, et al. , Promoter-bound METTL3 maintains myeloid leukaemia by m(6)A-dependent translation control. Nature, 2017. 552(7683): p. 126–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vu LP, et al. , The N(6)-methyladenosine (m(6)A)-forming enzyme METTL3 controls myeloid differentiation of normal hematopoietic and leukemia cells. Nat Med, 2017. 23(11): p. 1369–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li T, et al. , METTL3 facilitates tumor progression via an m(6)A-IGF2BP2-dependent mechanism in colorectal carcinoma. Mol Cancer, 2019. 18(1): p. 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han J, et al. , METTL3 promote tumor proliferation of bladder cancer by accelerating pri-miR221/222 maturation in m6A-dependent manner. Mol Cancer, 2019. 18(1): p. 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yue B, et al. , METTL3-mediated N6-methyladenosine modification is critical for epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of gastric cancer. Mol Cancer, 2019. 18(1): p. 142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xia T, et al. , The RNA m6A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and invasion. Pathol Res Pract, 2019. 215(11): p. 152666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Q, et al. , METTL3-mediated m(6)A modification of HDGF mRNA promotes gastric cancer progression and has prognostic significance. Gut, 2020. 69(7): p. 1193–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Q, et al. , N(6)-methyladenosine METTL3 promotes cervical cancer tumorigenesis and Warburg effect through YTHDF1/HK2 modification. Cell Death Dis, 2020. 11(10): p. 911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu X, et al. , Analysis of METTL3 and METTL14 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY), 2020. 12(21): p. 21638–21659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Visvanathan A, et al. , Essential role of METTL3-mediated m(6)A modification in glioma stem-like cells maintenance and radioresistance. Oncogene, 2018. 37(4): p. 522–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang C, et al. , METTL3 and N6-Methyladenosine Promote Homologous Recombination-Mediated Repair of DSBs by Modulating DNA-RNA Hybrid Accumulation. Mol Cell, 2020. 79(3): p. 425–442.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiong J, et al. , Lactylation-driven METTL3-mediated RNA m(6)A modification promotes immunosuppression of tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells. Mol Cell, 2022. 82(9): p. 1660–1677.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang L, et al. , m(6) A RNA methyltransferases METTL3/14 regulate immune responses to anti-PD-1 therapy. Embo j, 2020. 39(20): p. e104514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Donnell JS, et al. , Resistance to PD1/PDL1 checkpoint inhibition. Cancer Treat Rev, 2017. 52: p. 71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wan W, et al. , METTL3/IGF2BP3 axis inhibits tumor immune surveillance by upregulating N(6)-methyladenosine modification of PD-L1 mRNA in breast cancer. Mol Cancer, 2022. 21(1): p. 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yin H, et al. , RNA m6A methylation orchestrates cancer growth and metastasis via macrophage reprogramming. Nat Commun, 2021. 12(1): p. 1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tong J, et al. , Pooled CRISPR screening identifies m(6)A as a positive regulator of macrophage activation. Sci Adv, 2021. 7(18). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poh HX, et al. , Alternative splicing of METTL3 explains apparently METTL3-independent m6A modifications in mRNA. PLoS Biol, 2022. 20(7): p. e3001683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu J, et al. , N (6)-methyladenosine of chromosome-associated regulatory RNA regulates chromatin state and transcription. Science, 2020. 367(6477): p. 580–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deng S, et al. , RNA m(6)A regulates transcription via DNA demethylation and chromatin accessibility. Nat Genet, 2022. 54(9): p. 1427–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang H, et al. , Histone H3 trimethylation at lysine 36 guides m(6)A RNA modification co-transcriptionally. Nature, 2019. 567(7748): p. 414–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu W, et al. , METTL3 regulates heterochromatin in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature, 2021. 591(7849): p. 317–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu J, et al. , The RNA m(6)A reader YTHDC1 silences retrotransposons and guards ES cell identity. Nature, 2021. 591(7849): p. 322–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li Y, et al. , N(6)-Methyladenosine co-transcriptionally directs the demethylation of histone H3K9me2. Nat Genet, 2020. 52(9): p. 870–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu W, et al. , Dynamic control of chromatin-associated m(6)A methylation regulates nascent RNA synthesis. Mol Cell, 2022. 82(6): p. 1156–1168.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Su R, et al. , METTL16 exerts an m(6)A-independent function to facilitate translation and tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol, 2022. 24(2): p. 205–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lin S, et al. , The m(6)A Methyltransferase METTL3 Promotes Translation in Human Cancer Cells. Mol Cell, 2016. 62(3): p. 335–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Choe J, et al. , mRNA circularization by METTL3-eIF3h enhances translation and promotes oncogenesis. Nature, 2018. 561(7724): p. 556–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ianniello Z, et al. , New insight into the catalytic -dependent and -independent roles of METTL3 in sustaining aberrant translation in chronic myeloid leukemia. Cell Death Dis, 2021. 12(10): p. 870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu P, et al. , m(6)A-independent genome-wide METTL3 and METTL14 redistribution drives the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Nat Cell Biol, 2021. 23(4): p. 355–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dou X e.a. METTL14 is a chromatin regulator independent of its RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase activity. Protein & Cell, 2023. pwad009, DOI: 10.1093/procel/pwad009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tuck MT, et al. , Elevation of internal 6-methyladenine mRNA methyltransferase activity after cellular transformation. Cancer Lett, 1996. 103(1): p. 107–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shi H, et al. , YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N(6)-methyladenosine-modified RNA. Cell Res, 2017. 27(3): p. 315–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Han D, et al. , Anti-tumour immunity controlled through mRNA m(6)A methylation and YTHDF1 in dendritic cells. Nature, 2019. 566(7743): p. 270–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ma S, et al. , YTHDF2 orchestrates tumor-associated macrophage reprogramming and controls antitumor immunity through CD8(+) T cells. Nat Immunol, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Paris J, et al. , Targeting the RNA m(6)A Reader YTHDF2 Selectively Compromises Cancer Stem Cells in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cell Stem Cell, 2019. 25(1): p. 137–148 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dixit D, et al. , The RNA m6A Reader YTHDF2 Maintains Oncogene Expression and Is a Targetable Dependency in Glioblastoma Stem Cells. Cancer Discov, 2021. 11(2): p. 480–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fang R, et al. , EGFR/SRC/ERK-stabilized YTHDF2 promotes cholesterol dysregulation and invasive growth of glioblastoma. Nat Commun, 2021. 12(1): p. 177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li Z, et al. , Suppression of m(6)A reader Ythdf2 promotes hematopoietic stem cell expansion. Cell Res, 2018. 28(9): p. 904–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abakir A, et al. , N(6)-methyladenosine regulates the stability of RNA:DNA hybrids in human cells. Nat Genet, 2020. 52(1): p. 48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ries RJ, et al. , m(6)A enhances the phase separation potential of mRNA. Nature, 2019. 571(7765): p. 424–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fu Y and Zhuang X, m(6)A-binding YTHDF proteins promote stress granule formation. Nat Chem Biol, 2020. 16(9): p. 955–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zou Z, et al. , FMRP phosphorylation modulates neuronal translation through YTHDF1. Biorxiv, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li Y, et al. , FTO in cancer: functions, molecular mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. Trends Cancer, 2022. 8(7): p. 598–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shen C, et al. , RNA Demethylase ALKBH5 Selectively Promotes Tumorigenesis and Cancer Stem Cell Self-Renewal in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cell Stem Cell, 2020. 27(1): p. 64–80 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li Z, et al. , FTO Plays an Oncogenic Role in Acute Myeloid Leukemia as a N(6)-Methyladenosine RNA Demethylase. Cancer Cell, 2017. 31(1): p. 127–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wei J, et al. , FTO mediates LINE1 m(6)A demethylation and chromatin regulation in mESCs and mouse development. Science, 2022. 376(6596): p. 968–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Alexandrov A, Martzen MR, and Phizicky EM, Two proteins that form a complex are required for 7-methylguanosine modification of yeast tRNA. RNA, 2002. 8(10): p. 1253–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang LS, et al. , Transcriptome-wide Mapping of Internal N(7)-Methylguanosine Methylome in Mammalian mRNA. Mol Cell, 2019. 74(6): p. 1304–1316 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cheng W, et al. , Novel roles of METTL1/WDR4 in tumor via m(7)G methylation. Mol Ther Oncolytics, 2022. 26: p. 27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Orellana EA, et al. , METTL1-mediated m(7)G modification of Arg-TCT tRNA drives oncogenic transformation. Mol Cell, 2021. 81(16): p. 3323–3338 e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Huang Y, et al. , METTL1 promotes neuroblastoma development through m(7)G tRNA modification and selective oncogenic gene translation. Biomark Res, 2022. 10(1): p. 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen B, et al. , N(7)-methylguanosine tRNA modification promotes tumorigenesis and chemoresistance through WNT/beta-catenin pathway in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncogene, 2022. 41(15): p. 2239–2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chen Z, et al. , METTL1 promotes hepatocarcinogenesis via m(7) G tRNA modification-dependent translation control. Clin Transl Med, 2021. 11(12): p. e661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ying X, et al. , METTL1-m(7) G-EGFR/EFEMP1 axis promotes the bladder cancer development. Clin Transl Med, 2021. 11(12): p. e675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pandolfini L, et al. , METTL1 Promotes let-7 MicroRNA Processing via m7G Methylation. Mol Cell, 2019. 74(6): p. 1278–1290 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chellamuthu A and Gray SG, The RNA Methyltransferase NSUN2 and Its Potential Roles in Cancer. Cells, 2020. 9(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Garcia-Vilchez R, Sevilla A, and Blanco S, Post-transcriptional regulation by cytosine-5 methylation of RNA. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech, 2019. 1862(3): p. 240–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liao H, et al. , Human NOP2/NSUN1 regulates ribosome biogenesis through non-catalytic complex formation with box C/D snoRNPs. Nucleic Acids Res, 2022. 50(18): p. 10695–10716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Freeman JW, et al. , Prognostic significance of proliferation associated nucleolar antigen P120 in human breast carcinoma. Cancer Res, 1991. 51(8): p. 1973–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cheng JX, et al. , RNA cytosine methylation and methyltransferases mediate chromatin organization and 5-azacytidine response and resistance in leukaemia. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Janin M, et al. , Epigenetic loss of RNA-methyltransferase NSUN5 in glioma targets ribosomes to drive a stress adaptive translational program. Acta Neuropathol, 2019. 138(6): p. 1053–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Guzzi N, et al. , Pseudouridine-modified tRNA fragments repress aberrant protein synthesis and predict leukaemic progression in myelodysplastic syndrome. Nat Cell Biol, 2022. 24(3): p. 299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cui Q, et al. , Targeting PUS7 suppresses tRNA pseudouridylation and glioblastoma tumorigenesis. Nat Cancer, 2021. 2(9): p. 932–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Song D, et al. , HSP90-dependent PUS7 overexpression facilitates the metastasis of colorectal cancer cells by regulating LASP1 abundance. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2021. 40(1): p. 170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dai Q, et al. , Quantitative sequencing using BID-seq uncovers abundant pseudouridines in mammalian mRNA at base resolution. Nat Biotechnol, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Eisenberg E and Levanon EY, A-to-I RNA editing - immune protector and transcriptome diversifier. Nat Rev Genet, 2018. 19(8): p. 473–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Galeano F, et al. , ADAR2-editing activity inhibits glioblastoma growth through the modulation of the CDC14B/Skp2/p21/p27 axis. Oncogene, 2013. 32(8): p. 998–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liddicoat BJ, et al. , RNA editing by ADAR1 prevents MDA5 sensing of endogenous dsRNA as nonself. Science, 2015. 349(6252): p. 1115–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gannon HS, et al. , Identification of ADAR1 adenosine deaminase dependency in a subset of cancer cells. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 5450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ishizuka JJ, et al. , Loss of ADAR1 in tumours overcomes resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Nature, 2019. 565(7737): p. 43–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kung CP, et al. , Evaluating the therapeutic potential of ADAR1 inhibition for triple-negative breast cancer. Oncogene, 2021. 40(1): p. 189–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tassinari V, et al. , ADAR1 is a new target of METTL3 and plays a pro-oncogenic role in glioblastoma by an editing-independent mechanism. Genome Biol, 2021. 22(1): p. 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yankova E, et al. , Small-molecule inhibition of METTL3 as a strategy against myeloid leukaemia. Nature, 2021. 593(7860): p. 597–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Blackaby WPH, D. J.; Thomas EJ; Brookfield FA; Shepherd J; Bubert C; Ridgill MP, Polyheterocyclic compounds as METTL3 inhibitors. 2021, Storm Therapeutics WO 2021111124 A1. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Blackaby WPH, D. J.; Thomas EJ; Brookfield FA; Bubert C; Shepherd J; Ridgill MP METTL3 Inhibitory Compounds, METTL3 Inhibitory Compounds. 2020, Storm Therapeutics WO 2020201773 A1. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hardick DJB, W. P.; Thomas EJ; Brookfield FA; Shepherd J; Bubert C; Ridgill MP, METTL3 Inhibitory compounds. 2022, Storm Therapeutics WO 2022074379 A1. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hardick DJB, W. P.; Thomas EJ; Brookfield FA; Shepherd J; Bubert C; Ridgill MP, Compounds Inhibitors of METTL3. 2022, Storm Therapeutics WO 2022074391 A1. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mills JEJD, M. H.; Wynn TA; Sparling BA;Sickmier EA; Tasker AS, METTL3 modulators. 2022, Accent Therapeutics WO 2022081739 A1. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tasker ASD, M. H.; Duncan KW; Sparling BA; Wynn TA; Hodous BL; Boriack-Sjodin PA; Sickmier EA;Mills JEJ; Copeland RA, METTL3 modulators. 2021, Accent Therapeutics WO 2021079196 A2. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wynn TAH, B. L.; Boriack-Sjodin PA; Sickmier EA; Mills JEJ; Tasker AS; Copeland RA, METTL3 Modulators. 2021, Accent Therapeutics WO 2021081211 A1. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Dolbois A, et al. , 1,4,9-Triazaspiro[5.5]undecan-2-one Derivatives as Potent and Selective METTL3 Inhibitors. J Med Chem, 2021. 64(17): p. 12738–12760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Manna S, et al. , Amentoflavone and methyl hesperidin, novel lead molecules targeting epitranscriptomic modulator in acute myeloid leukemia: in silico drug screening and molecular dynamics simulation approach. J Mol Model, 2022. 29(1): p. 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bedi RK, et al. , Small-Molecule Inhibitors of METTL3, the Major Human Epitranscriptomic Writer. Chem Med Chem, 2020. 15(9): p. 744–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lee JH, et al. , Discovery of substituted indole derivatives as allosteric inhibitors of m(6) A-RNA methyltransferase, METTL3–14 complex. Drug Dev Res, 2022. 83(3): p. 783–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lee JH, et al. , Eltrombopag as an Allosteric Inhibitor of the METTL3–14 Complex Affecting the m(6)A Methylation of RNA in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 2022. 15(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Boriack-Sjodin PA, Ribich S, and Copeland RA, RNA-modifying proteins as anticancer drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2018. 17(6): p. 435–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Fiorentino F, et al. , METTL3 from Target Validation to the First Small-Molecule Inhibitors: A Medicinal Chemistry Journey. J Med Chem, 2023. 66(3): p. 1654–1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Micaelli M, et al. , Small-Molecule Ebselen Binds to YTHDF Proteins Interfering with the Recognition of N (6)-Methyladenosine-Modified RNAs. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci, 2022. 5(10): p. 872–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wang X, et al. , Transient regulation of RNA methylation in human hematopoietic stem cells promotes their homing and engraftment. Leukemia, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Cheng Y, et al. , N(6)-Methyladenosine on mRNA facilitates a phase-separated nuclear body that suppresses myeloid leukemic differentiation. Cancer Cell, 2021. 39(7): p. 958–972 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Su R, et al. , Targeting FTO Suppresses Cancer Stem Cell Maintenance and Immune Evasion. Cancer Cell, 2020. 38(1): p. 79–96 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Floresta G, et al. , Molecular modeling studies of pseudouridine isoxazolidinyl nucleoside analogues as potential inhibitors of the pseudouridine 5’-monophosphate glycosidase. Chem Biol Drug Des, 2018. 91(2): p. 519–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Veliz EA, Easterwood LM, and Beal PA, Substrate analogues for an RNA-editing adenosine deaminase: mechanistic investigation and inhibitor design. J Am Chem Soc, 2003. 125(36): p. 10867–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Cottrell KA, et al. , 8-azaadenosine and 8-chloroadenosine are not selective inhibitors of ADAR. Cancer Res Commun, 2021. 1(2): p. 56–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Choudhry H, High-throughput screening to identify potential inhibitors of the Zalpha domain of the adenosine deaminase 1 (ADAR1). Saudi J Biol Sci, 2021. 28(11): p. 6297–6304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Dowden H and Munro J, Trends in clinical success rates and therapeutic focus. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2019. 18(7): p. 495–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kaelin WG Jr., Common pitfalls in preclinical cancer target validation. Nat Rev Cancer, 2017. 17(7): p. 425–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Dale B, et al. , Advancing targeted protein degradation for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer, 2021. 21(10): p. 638–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sun Y, et al. , YTHDF1 promotes breast cancer cell growth, DNA damage repair and chemoresistance. Cell Death Dis, 2022. 13(3): p. 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Li M, et al. , METTL3 mediates chemoresistance by enhancing AML homing and engraftment via ITGA4. Leukemia, 2022. 36(11): p. 2586–2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Fiorentino F, et al. , METTL3 from Target Validation to the First Small-Molecule Inhibitors: A Medicinal Chemistry Journey. J Med Chem, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Moroz-Omori EV, et al. , METTL3 Inhibitors for Epitranscriptomic Modulation of Cellular Processes. ChemMedChem, 2021. 16(19): p. 3035–3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Liao L, et al. , Anti-HIV Drug Elvitegravir Suppresses Cancer Metastasis via Increased Proteasomal Degradation of m6A Methyltransferase METTL3. Cancer Res, 2022. 82(13): p. 2444–2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Huang Y, et al. , Small-Molecule Targeting of Oncogenic FTO Demethylase in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Cell, 2019. 35(4): p. 677–691 e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Zheng G, et al. , Synthesis of a FTO inhibitor with anticonvulsant activity. ACS Chem Neurosci, 2014. 5(8): p. 658–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Singh B, et al. , Important Role of FTO in the Survival of Rare Panresistant Triple-Negative Inflammatory Breast Cancer Cells Facing a Severe Metabolic Challenge. PLoS One, 2016. 11(7): p. e0159072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Huang Y, et al. , Meclofenamic acid selectively inhibits FTO demethylation of m6A over ALKBH5. Nucleic Acids Res, 2015. 43(1): p. 373–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Huff S, et al. , m(6)A-RNA Demethylase FTO Inhibitors Impair Self-Renewal in Glioblastoma Stem Cells. ACS Chem Biol, 2021. 16(2): p. 324–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Liu Y, et al. , Tumors exploit FTO-mediated regulation of glycolytic metabolism to evade immune surveillance. Cell Metab, 2021. 33(6): p. 1221–1233 e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Su R, et al. , R-2HG Exhibits Anti-tumor Activity by Targeting FTO/m(6)A/MYC/CEBPA Signaling. Cell, 2018. 172(1–2): p. 90–105 e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Selberg S, et al. , Rational Design of Novel Anticancer Small-Molecule RNA m6A Demethylase ALKBH5 Inhibitors. ACS Omega, 2021. 6(20): p. 13310–13320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]